- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Harvard Business School Case Study: Gender Equity

By Jodi Kantor

- Sept. 7, 2013

BOSTON — When the members of the Harvard Business School class of 2013 gathered in May to celebrate the end of their studies, there was little visible evidence of the experiment they had undergone for the last two years. As they stood amid the brick buildings named after businessmen from Morgan to Bloomberg, black-and-crimson caps and gowns united the 905 graduates into one genderless mass.

But during that week’s festivities, the Class Day speaker, a standout female student, alluded to “the frustrations of a group of people who feel ignored.” Others grumbled that another speechmaker, a former chief executive of a company in steep decline, was invited only because she was a woman. At a reception, a male student in tennis whites blurted out, as his friends laughed, that much of what had occurred at the school had “been a painful experience.”

He and his classmates had been unwitting guinea pigs in what would have once sounded like a far-fetched feminist fantasy: What if Harvard Business School gave itself a gender makeover, changing its curriculum, rules and social rituals to foster female success?

The country’s premier business training ground was trying to solve a seemingly intractable problem. Year after year, women who had arrived with the same test scores and grades as men fell behind. Attracting and retaining female professors was a losing battle; from 2006 to 2007, a third of the female junior faculty left.

Some students, like Sheryl Sandberg, class of ’95, the Facebook executive and author of “Lean In,” sailed through. Yet many Wall Street-hardened women confided that Harvard was worse than any trading floor, with first-year students divided into sections that took all their classes together and often developed the overheated dynamics of reality shows. Some male students, many with finance backgrounds, commandeered classroom discussions and hazed female students and younger faculty members, and openly ruminated on whom they would “kill, sleep with or marry” (in cruder terms). Alcohol-soaked social events could be worse.

“You weren’t supposed to talk about it in open company,” said Kathleen L. McGinn, a professor who supervised a student study that revealed the grade gap. “It was a dirty secret that wasn’t discussed.”

But in 2010, Drew Gilpin Faust, Harvard’s first female president, appointed a new dean who pledged to do far more than his predecessors to remake gender relations at the business school. He and his team tried to change how students spoke, studied and socialized. The administrators installed stenographers in the classroom to guard against biased grading, provided private coaching — for some, after every class — for untenured female professors, and even departed from the hallowed case-study method.

The dean’s ambitions extended far beyond campus, to what Dr. Faust called in an interview an “obligation to articulate values.” The school saw itself as the standard-bearer for American business. Turning around its record on women, the new administrators assured themselves, could have an untold impact at other business schools, at companies populated by Harvard alumni and in the Fortune 500, where only 21 chief executives are women. The institution would become a laboratory for studying how women speak in group settings, the links between romantic relationships and professional status, and the use of everyday measurement tools to reduce bias.

“We have to lead the way, and then lead the world in doing it,” said Frances Frei, her words suggesting the school’s sense of mission but also its self-regard. Ms. Frei, a popular professor turned administrator who had become a target of student ire, was known for the word “unapologetic,” as in: we are unapologetic about the changes we are making.

By graduation, the school had become a markedly better place for female students, according to interviews with more than 70 professors, administrators and students, who cited more women participating in class, record numbers of women winning academic awards and a much-improved environment, down to the male students drifting through the cafeteria wearing T-shirts celebrating the 50th anniversary of the admission of women. Women at the school finally felt like, “ ‘Hey, people like me are an equal part of this institution,’ ” said Rosabeth Moss Kanter, a longtime professor.

And yet even the deans pointed out that the experiment had brought unintended consequences and brand new issues. The grade gap had vaporized so fast that no one could quite say how it had happened. The interventions had prompted some students to revolt, wearing “Unapologetic” T-shirts to lacerate Ms. Frei for what they called intrusive social engineering. Twenty-seven-year-olds felt like they were “back in kindergarten or first grade,” said Sri Batchu, one of the graduating men.

Students were demanding more women on the faculty, a request the deans were struggling to fulfill. And they did not know what to do about developments like female students dressing as Playboy bunnies for parties and taking up the same sexual rating games as men. “At each turn, questions come up that we’ve never thought about before,” Nitin Nohria, the new dean, said in an interview.

The administrators had no sense of whether their lessons would last once their charges left campus. As faculty members pointed out, the more exquisitely gender-sensitive the school environment became, the less resemblance it bore to the real business world. “Are we trying to change the world 900 students at a time, or are we preparing students for the world in which they are about to go?” a female professor asked.

The Beginning

Nearly two years earlier, in the fall of 2011, Neda Navab sat in a class participation workshop, incredulous. The daughter of Iranian immigrants, Ms. Navab had been the president of her class at Columbia, advised chief executives as a McKinsey & Company consultant and trained women as entrepreneurs in Rwanda. Yet now that she had arrived at the business school at age 25, she was being taught how to raise her hand.

A second-year student, a former member of the military, stood in the front of the classroom issuing commands: Reach up assertively! No apologetic little half-waves! Ms. Navab exchanged amused glances with new friends. She had no idea that she was witnessing an assault on the school’s most urgent gender-related challenge.

Women at Harvard did fine on tests. But they lagged badly in class participation, a highly subjective measure that made up 50 percent of each final mark. Every year the same hierarchy emerged early on: investment bank and hedge fund veterans, often men, sliced through equations while others — including many women — sat frozen or spoke tentatively. The deans did not want to publicly dwell on the problem: that might make the women more self-conscious. But they lectured about respect and civility, expanded efforts like the hand-raising coaching and added stenographers in every class so professors would no longer rely on possibly biased memories of who had said what.

They rounded out the case-study method, in which professors cold-called students about a business’s predicament, with a new course called Field, which grouped students into problem-solving teams. (Gender was not the sole rationale for the course, but the deans thought the format would help.) New grading software tools let professors instantly check their calling and marking patterns by gender. One professor, Mikolaj Piskorski, summarized Mr. Nohria’s message later: “We’re going to solve it at the school level, but each of you is responsible to identify what you are doing that gets you to this point.”

Mr. Nohria, Ms. Frei and others involved in the project saw themselves as outsiders who had succeeded at the school and wanted to help others do the same. Ms. Frei, the chairwoman of the first-year curriculum, was the most vocal, with her mop of silver-brown hair and the drive of the college basketball player she had once been. “Someone says ‘no’ to me, and I just hear ‘not yet,’ ” she said.

After years of observation, administrators and professors agreed that one particular factor was torpedoing female class participation grades: women, especially single women, often felt they had to choose between academic and social success.

One night that fall, Ms. Navab, who had laughed off the hand-raising seminar, sat at an Ethiopian restaurant wondering if she had made a bad choice. Her marketing midterm exam was the next day, but she had been invited on a very business-school kind of date: a new online dating service that paired small groups of singles for drinks was testing its product. Did Ms. Navab want to come? “If I were in college, I would have said let’s do this after the midterm,” she said later.

But she wanted to meet someone soon, maybe at Harvard, which she and other students feared could be their “last chance among cream-of-the-crop-type people,” as she put it. Like other students, she had quickly discerned that her classmates tended to look at their social lives in market terms, implicitly ranking one another. And like others, she slipped into economic jargon to describe their status.

The men at the top of the heap worked in finance, drove luxury cars and advertised lavish weekend getaways on Instagram, many students observed in interviews. Some belonged to the so-called Section X, an on-again-off-again secret society of ultrawealthy, mostly male, mostly international students known for decadent parties and travel.

Women were more likely to be sized up on how they looked, Ms. Navab and others found. Many of them dressed as if Marc Jacobs were staging a photo shoot in a Technology and Operations Management class. Judging from comments from male friends about other women (“She’s kind of hot, but she’s so assertive”), Ms. Navab feared that seeming too ambitious could hurt what she half-jokingly called her “social cap,” referring to capitalization.

“I had no idea who, as a single woman, I was meant to be on campus,” she said later. Were her priorities “purely professional, were they academic, were they to start dating someone?”

As she scooped bread at the product-trial-slash-date at the Ethiopian restaurant, she realized that she had not caught the names of the men at the table. The group drank more and more. The next day she took the test hung over, her performance a “disaster,” she joked.

The deans did not know how to stop women from bartering away their academic promise in the dating marketplace, but they wanted to nudge the school in a more studious, less alcohol-drenched direction. “We cannot have it both ways,” said Youngme Moon, the dean of the M.B.A. program. “We cannot be a place that claims to be about leadership and then say we don’t care what goes on outside the classroom.”

But Harvard Business students were unusually powerful, the school’s products and also its customers, paying more than $50,000 in tuition per year. They were professionals, not undergraduates. One member of the class had played professional football; others had served in Afghanistan or had last names like Blankfein ( Alexander , son of Lloyd, chief executive of Goldman Sachs). They had little knowledge of the institutional history; the deans talked less about the depressing record on women than vague concepts like “culture” and “community” and “inclusion.”

As the semester went on, many students felt increasingly baffled about the deans’ seeming desire to be involved in their lives. They resented the additional work of the Field courses, which many saw as superfluous or even a scheme to keep them too busy for partying. Students used to form their own study groups, but now the deans did it for them.

As Halloween approached, some students planned to wear costumes to class, but at the last minute Ms. Frei, who wanted to set a serious tone and head off the potential for sexy pirate costumes, sent a note out prohibiting it, provoking more eye rolls. “How much responsibility does H.B.S. have?” Laura Merritt, a co-president of the class, asked later. “Do we have school uniforms? Where do you stop?”

A few days before the end of the fall semester, Amanda Upton, an investment banking veteran, stood before most of her classmates, lecturing and quizzing them about finance. Every term just before finals, the Women’s Student Association organized a review session for each subject, led by a student who blitzed classmates through reams of material in an hour. Some of the first-years had not had a single female professor. Now Ms. Upton delivered a bravura performance, clearing up confusion about discounted cash flow and how to price bonds, tossing out Christmas candy as rewards.

Like many other women, Kate Lewis, the school newspaper editor, believed in the deans’ efforts. But she thought Ms. Upton’s turn did more to fortify the image of women than anything administrators had done. “It’s the most powerful message: this girl knows it better than all of you,” she said.

Breaking the Ice

One day in April 2012, the entire first-year class, including Brooke Boyarsky, a Texan known for cracking up her classmates with a mock PowerPoint presentation, reported to classrooms for a mandatory discussion about sexual harassment. As students soon learned, one woman had confided to faculty members that a male student she would not identify had groped her in an off-campus bar months before. Rather than dismissing the episode, the deans decided to exploit it: this was their chance to discuss the drinking scene and its consequences. “They could not have gone any more front-page than this,” Ms. Boyarsky said later.

Everyone in Ms. Boyarsky’s classes knew she was incisive and funny, but within the campus social taxonomy, she was overlooked — she was overweight and almost never drank much, stayed out late or dated. After a few minutes of listening to the stumbling conversation about sexual harassment, she raised her hand to make a different point, about the way the school’s social life revolved around appearance and money.

“Someone made the decision for me that I’m not pretty or wealthy enough to be in Section X,” she told her classmates, her voice breaking.

The room jumped to life. The students said they felt overwhelmed by the wealth that coursed through the school, the way it seemed to shape every aspect of social life — who joined activities that cost hundreds of dollars, who was invited to the parties hosted by the student living in a penthouse apartment at the Mandarin Oriental hotel in Boston. Some students would never have to seek work at all — they were at Harvard to learn to invest their families’ fortunes — and others were borrowing thousands of dollars a year just to keep up socially.

The discussion broke the ice, just not on the topic the deans had intended. “Until then, no one else had publicly said ‘Section X,’ ” Mr. Batchu said. Maybe it was because class was easier to talk about than gender, or maybe it was because class was the bigger divide — at the school and in the country.

That was only one out of 10 sessions. At most of the others, the men contributed little. Some of them, and even a few women, had grown to openly resent the deans’ emphasis on gender, using phrases like “ad nauseam” and “shoved down our throats,” protesting that this was not what they had paid to learn.

Patrick Erker was not among the naysayers — he considered himself a feminist and a fan of the deans. As an undergraduate at Duke, he had managed the women’s basketball team, wiping their sweat from the floor and picking up their dirty jerseys.

But as he silently listened to the discussion, he decided the setup was all wrong: a discussion of a sex-related episode they knew little about, with “89 other people judging every word,” led by professors who would be grading them later that semester.

“I’d like to be candid, but I paid half a million dollars to come here,” another man said in an interview, counting his lost wages. “I could blow up my network with one wrong comment.” The men were not insensitive, they said; they just considered the discussion a poor investment of their carefully hoarded social capital. Mr. Erker used the same words as many other students had to describe the mandatory meetings: “forced” and “patronizing.”

That week, Andrew Levine, the director of the annual spoof show, was notified by administrators that he was on academic and social probation because other students had consumed alcohol in the auditorium after a performance. (His crime: dining with visiting family instead of staying as he had promised in a contract.) He was barred from social events and put on academic probation as well.

That was just what students needed to believe their worst suspicions about the administration. Ms. Frei had not made the decision about Mr. Levine and worked to cancel his academic probation, he said later, but students called her a hypocrite, a leadership expert who led badly. Hundreds of students soon wore T-shirts that said “Free Andy” or “Unapologetic.”

“Daddy, why are the students hating on you?” Mr. Nohria’s teenage daughters asked him, he told students later.

A few days before commencement, Nathan Bihlmaier , a second-year student, disappeared while celebrating with classmates in Portland, Me. He had last been seen so inebriated that a bartender had asked him to leave a pub. When the authorities told students that Mr. Bihlmaier’s body had been dredged from the harbor, apparently after a fall, Mr. Nohria and Ms. Moon were standing beside them.

The first year of their experiment was ending with a catastrophe that brought home how little sway they really had over students’ actions. Mr. Bihlmaier had not even been the drinking type. In the spirit of feminist celebration, Ms. Sandberg gave a graduation address at the deans’ invitation, but during the festivities all eyes were on Mr. Bihlmaier’s widow, visibly pregnant with their first child.

Amid all the turmoil, though, the deans saw cause for hope. The cruel classroom jokes, along with other forms of intimidation, were far rarer. Students were telling them about vigorous private conversations that had flowed from the halting public ones. Women’s grades were rising — and despite the open resentment toward the deans, overall student satisfaction ratings were higher than they had been for years.

A Lopsided Situation

Even on the coldest nights of early 2013, Ms. Frei walked home from campus, clutching her iPhone and listening to a set of recordings made earlier in the day. Once her two small sons were in bed, she settled at her dining table, wearing pajamas and nursing a glass of wine, and fired up the digital files on her laptop. “Really? Again?” her wife, Anne Morriss, would ask.

Ms. Frei been promoted to dean of faculty recruiting, and she was on a quest to bolster the number of female professors, who made up a fifth of the tenured faculty. Female teachers, especially untenured ones, had faced various troubles over the years: uncertainty over maternity leave, a lack of opportunities to write papers with senior professors, and students who destroyed their confidence by pelting them with math questions they could not answer on the spot or commenting on what they wore.

“As a female faculty member, you are in an incredibly hostile teaching environment, and they do nothing to protect you,” said one woman who left without tenure. A current teacher said she was so afraid of a “wardrobe malfunction” that she wore only custom suits in class, her tops invisibly secured to her skin with double-sided tape.

Now Ms. Frei, the guardian of the female junior faculty, was watching virtually every minute of every class some of them taught, delivering tips on how to do better in the next class. She barred other professors from giving them advice, lest they get confused. But even some of Ms. Frei’s allies were dubious.

At the end of every semester, students gave professors teaching scores from a low of 1 to a high of 7, and some of the female junior faculty scores looked beyond redemption. More of the male professors arrived at Harvard after long careers, regaling students with real-life experiences. Because the pool of businesswomen was smaller, female professors were more likely to be academics, and students saw female stars as exceptions.

“The female profs I had were clearly weaker than the male ones,” said Halle Tecco, a 2011 graduate. “They weren’t able to really run the classroom the way the male ones could.”

Take the popular second-year courses team-taught by Richard S. Ruback, a top finance professor, and Royce G. Yudkoff, a co-founder of a private equity firm that managed billions of dollars. The men taught students, among other lessons, how to start a “search fund,” a pool of money to finance them while they found and acquired a company. In recent years, search funds had become one of the hottest, riskiest and most potentially lucrative pursuits for graduates of top business schools — shortcuts to becoming owners and chief executives.

The two professors were blunt and funny, pushing a student one moment, ribbing another one the next. They embodied the financial promise of a Harvard business degree: if the professors liked you, students knew, they might advise and even back you.

As Ms. Frei reviewed her tapes at night, making notes as she went along, she looked for ways to instill that confidence. The women, who plainly wanted to be liked, sometimes failed to assert their authority — say, by not calling out a student who arrived late. But when they were challenged, they turned too tough, responding defensively (“Where did you get that?”).

Ms. Frei urged them to project warmth and high expectations at the same time, to avoid trying to bolster their credibility with soliloquies about their own research. “I think the class might be a little too much about you, and not enough about the students,” she would tell them the next day.

By the end of the semester, the teaching scores of the women had improved so much that she thought they were a mistake. One professor had shot to a 6 from a 4. Yet all the attention, along with other efforts to support female faculty, made no immediate impact on the numbers of female teachers. So few women were coming to teach at the school that evening out the numbers seemed almost impossible.

As their final semester drew to a close, the students were preoccupied with the looming question of their own employment. Like graduates before them, the class of 2013 would to some degree part by gender after graduation, with more men going into higher-paying areas like finance and more women going into lower-paying ones like marketing.

Ms. Navab, who had started dating one of the men — with an M.D. and an M.B.A. — from the Ethiopian dinner, had felt freer to focus on her career once she was paired off. She was happy with her job at a California start-up, but she pointed out that she and some other women never heard about many of the most lucrative jobs because the men traded contacts and tips among themselves.

This was the lopsided situation that women in business school were facing: in intellectual prestige, they were pulling even with or outpacing male peers, but they were not “ touching the money ,” as Nori Gerardo Lietz, a real estate private equity investor and faculty member, put it. A few alumnae had founded promising start-ups like Rent the Runway , an evening wear rental service, but when it came to reaping big financial rewards, most women were barely in the game.

At an extracurricular presentation the year before, a female student asked William Boyce, a co-founder of Highland Capital Partners, a venture capital firm , for advice for women who wanted to go into his field. “Don’t,” he laughed, according to several students present. Male partners did not want them there, he continued, and he was doing them a favor by warning them.

Some women protested or walked out, but others said they believed he was telling the truth. (In interviews, Mr. Boyce denied saying women should not go into venture capital, but an administrator said student complaints prompted the school to contact the firm, which he had left decades before.)

The deans had not focused on career choice, earning power or staying in the work force; they felt they first needed to address campus issues. Besides, the earning gap posed a dilemma: they were hoping fewer students would default to finance as a career. “Have the courage to make the choices early in your life that are determined by your passions,” Mr. Nohria told students.

Plenty of women had taken Mr. Ruback and Mr. Yudkoff’s classes on acquiring and running businesses, including Ms. Upton, who had delivered the crackerjack finance presentation. She counted 30 to 40 classmates planning search funds, all men except for a no-nonsense engineer named Jennifer Braus. The professors eventually decided to finance and advise Ms. Braus, hoping other Harvard women would follow.“Nothing succeeds like success,” Mr. Ruback said.

Ms. Upton decided to take a far lower-risk job managing a wealthy family’s investments in Pittsburgh, where her fiancé lived. “You can either be a frontier charger or have an easier, happier life,” she said.

Looking Ahead

Of all the ceremonies and receptions during graduation week, the most venerated was the George F. Baker Scholar Luncheon, for the top 5 percent of the class, held in a sunny dining room crowded with parents who looked alternately thrilled and intimidated by what their offspring had achieved.

In recent years, the glory of the luncheon had been dimmed by discomfort at the low number of female honorees. But this year, almost 40 percent of the Baker scholars were women. It was a remarkable rise that no one could precisely explain. Had the professors rid themselves of unconscious biases? Were the women performing better because of the improved environment? Or was the faculty easing up in grading women because they knew the desired outcome?

“To my head, all three happened,” Professor Piskorski said. But Mr. Nohria said he had no cause to think the professors had used the new software, and the subjective participation scores, to avoid gender gaps. “Sunshine is the best disinfectant,” he said, a phrase that he said had guided him throughout his project.

One of the Baker scholars was Ms. Boyarsky, the classroom truth-teller. Two hours after the luncheon, she stepped up to a lectern to address thousands of graduates, faculty members and parents . Of the two dozen or so men and only 2 women who had tried out before a student committee, she had beaten them all, with a witty, self-deprecating speech unlike any in the school’s memory.

“I entered H.B.S. as a truly ‘untraditional applicant’: morbidly obese,” she said.

The theme of her speech was finding the courage to make necessary but painful changes. “Courage is a brand new H.B.S. professor, younger than some of her students, teaching her very first class on her very first day,” she said. “Courage is one woman” — the one who reported the groping episode — “who wakes the entire school up to the fact that gender relations still have a long way to go at H.B.S.”

And, Ms. Boyarsky continued, she had lost more than 100 pounds during her final year at Harvard. “Courage was then me battling the urge to be defensive — something I believe I had been for a long time about this particular issue — and taking a hard, honest look within myself to figure out what had prevented change,” she said.

Even before she finished, her phone was buzzing with e-mails and texts from classmates. She was the girl everyone wished they had gotten to know better, the graduation-week equivalent of the person whose obituary made you wish you had followed her work. She had closed the two-year experiment by making the best possible case for it. “This is the student they chose to show off to the world,” Ms. Moon said. For the next academic year, she was arranging for second-year students to lead many of the trickiest conversations, realizing students were the most potent advocates.

The administrators and the class of 2013 were parting ways, their experiment continuing. The deans vowed to carry on but could not say how aggressively: whether they were willing to revise the tenure process to attract more female contenders, or allow only firms that hired and promoted female candidates to recruit on campus. “We made progress on the first-level things, but what it’s permitting us to do is see, holy cow, how deep-seated the rest of this is,” Ms. Frei said.

The students were fanning out to their new jobs, full of suspense about their fates. Because of the unique nature of what they had experienced, they knew, every class alumni magazine update and reunion would be a referendum on how high the women could climb and what values the graduates instilled — the true verdict on the experiment in which they had taken part.

As Ms. Boyarsky glanced around her new job as a consultant at McKinsey in Dallas, she often noticed that she was outnumbered by men, but she spoke up anyway. She was dating more than she had at school, she added with shy enthusiasm.

“I am super excited to go to my 30th reunion,” she said.

Brent McDonald and Hannah Fairfield contributed reporting.

- University News

- Faculty & Research

- Health & Medicine

- Science & Technology

- Social Sciences

- Humanities & Arts

- Students & Alumni

- Arts & Culture

- Sports & Athletics

- The Professions

- International

- New England Guide

The Magazine

- Current Issue

- Past Issues

Class Notes & Obituaries

- Browse Class Notes

- Browse Obituaries

Collections

- Commencement

- The Context

Harvard Squared

- Harvard in the Headlines

Support Harvard Magazine

- Why We Need Your Support

- How We Are Funded

- Ways to Support the Magazine

- Special Gifts

- Behind the Scenes

Classifieds

- Vacation Rentals & Travel

- Real Estate

- Products & Services

- Harvard Authors’ Bookshelf

- Education & Enrichment Resource

- Ad Prices & Information

- Place An Ad

Follow Harvard Magazine:

John Harvard's Journal

A Case For Women

September-October 2015

Robin J. Ely Photograph by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

When Nitin Nohria became Harvard Business School (HBS) dean in mid 2010, he detailed five priorities, ranging from innovation in education and internationalization to inclusion. In setting out the latter goal, he said in a recent conversation, he aimed not at numerical diversity, but at a broader objective: that every HBS student and teacher be enabled to thrive within the community.

A decanal missive in early 2011 further defined the work required to make HBS genuinely inclusive. “I have launched an initiative that will focus…on the challenges facing women at the school,” Nohria wrote. He created an institutional home for the work—a senior associate deanship for culture and community—and appointed Wilson professor of business administration Robin J. Ely to the post: a logical choice, given her research on race and gender relations in organizations. (Making progress, he noted, has entailed work by other faculty colleagues, too, including Youngme Moon, then in her capacity as senior associate dean for the M.B.A. program , and Frances Frei, senior associate dean for faculty planning and recruitment . Frei, he said, has played a vital role in helping women faculty members—sometimes “given a shorter runway” in adjusting to their new responsibilities—succeed at the school.)

Ely’s role, he explained in the interview, was initially intended to help HBS look at itself and evolve practices that might make it a role model for other institutions. The school’s W50 summit in 2013, which examined the first half-century of women enrolled in the M.B.A. program, provided an opportunity, he noted, to “come to terms with our own history”—not all of it welcoming or inclusive (see “The Girls of HBS,” July-August 2013, and the linked report on W50 ).

A complementary strand would involve HBS’s academic life: “Who gets represented?” in the teaching cases professors develop, as Nohria put it. In his annual letter to faculty colleagues this past January , he wrote, “I know that of the dozens of cases I have written, fewer than 10 percent have had a woman in a leadership position.” Moreover “[T]he most effective cases are not necessarily those where women protagonists are dealing with gendered issues like work-life balance, but rather leading change and other strategic initiatives within an organization.” Just as M.B.A. cases have become increasingly global in the past decade, he aims for at least 20 percent to “feature a female” leader within the next three years. (And because HBS sells cases to schools worldwide, that shift will radiate far beyond Allston.)

Writing such cases is part and parcel of HBS professors’ research, and in a natural development, Ely’s initial role has evolved toward the externally focused perspectives Nohria described. HBS’s new Gender Initiative , under her leadership, is a research forum for faculty members who examine gender issues in businesses and other organizations.

Ely recently recalled the concerns that prompted Nohria’s initial interest, including persistent underrepresentation of women among M.B.A. students earning highest academic honors. To address such issues, she said, she wanted to look at the school’s culture broadly, to determine whether possible group differences in how students, faculty, and staff members experienced the culture affected their ability to succeed. (She noted that Cahners-Rabb professor of business administration Kathleen L. McGinn ’s prior work with students had explored how HBS’s cultural dynamics might have contributed to a gender gap in grades—helping to pave the way and set the agenda for the culture initiative.)

HBS academic honors, for instance, are based strictly on grades, which are heavily influenced by classroom participation. Exploring the culture, Ely said, made issues such as students’ willingness to express their views, professors’ patterns of calling on them, and the operation of student study groups “discussable”—the precursor to change. (In fact, achievement and satisfaction gaps have narrowed.) Airing these matters has also shaped student conversations about social dynamics and extracurriculars.

Given these fruitful discussions, raising HBS’s scrutiny of gender upward and outward was a natural next step. Nohria’s January letter asked: “Can we conduct work that will accelerate the advancement of women leaders who will make a difference in the world and promote gender and other types of equity in business and society?” The Gender Initiative, with Ely as faculty leader and Colleen C. Ammerman as assistant director, now serves as a locus for research among professors in units across HBS.

It is anchored by a core group including Ely herself; McGinn (now exploring the impact on school performance, age of marriage, and other outcomes of teaching African girls negotiating skills); Chapman professor of business administration Boris Groysberg (author of Chasing Stars: The Myth of Talent and the Portability of Performance , which uncovered a significant gap in financial analysts’ ability to maintain their “star” status when they move to new firms—unexpectedly, in women’s favor); associate professor of business administration Amy J.C. Cuddy (who is looking at gender stereotypes across cultures); assistant professor of business administration Lakshmi Ramarajan (who examines how individuals’ cultural and personal identities affect their engagement and performance in organizations); and others.

Since its unveiling in May, the initiative has already publicized several findings:

- HBS graduates are an elite cohort of above-average means. A survey of women and men who earned M.B.A. degrees reveals that they value careers and professional success equally. But as Ely, sociologist Pamela Stone of City University of New York, and Ammerman reported, although “about 50 percent to 60 percent of men across the three generations [said] they were ‘extremely satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with their experiences of meaningful work, professional accomplishments, opportunities for career growth, and compatibility of work and personal life, only 40 percent to 50 percent of women were similarly satisfied on the same dimensions.”

- A survey of 24 developed nations, led by McGinn , revealed that—far from being harmed—women whose mothers worked outside the home are themselves more likely to work, assume greater professional responsibilities, and achieve higher earnings than women whose mothers were at home full time.

- And although women’s under-representation in the most senior ranks of business leadership is often attributed to the lack of “family-friendly” workplace policies, an in-depth analysis of a consulting firm, co-conducted by Ely, pointed to a more intractable problem: a culture of being at work or on call around the clock—the new norm in lucrative professions like law, finance, and consulting, and one that firms are loath to restrain. Both men and women suffer in these cultures, but women are more likely to avail themselves of part-time options or otherwise adapt to care for family members, derailing their careers.

Interest in gender-related questions, Ely said, also “bubbles up from the faculty” at large. Thus, for instance, a faculty member who focuses on entrepreneurship is determining the antecedents to women’s interest in pursuing entrepreneurial ventures.

In addition to encouraging and publicizing research, the initiative convenes an annual conference to focus scholarship and learning from practice, engaging participants from within HBS and beyond. Like the school’s other interdisciplinary initiatives, Ammerman said, this one provides a locus for faculty members to test ideas with colleagues, learn about pertinent research, and address new questions to data already collected for other purposes: a place to go when those queries “bubble up.” As Nohria hoped, the fledgling venture is becoming an intellectual home for women and men from the HBS faculty who want to understand how gender affects organizations’ operations—and individuals’ trajectories.

You might also like

Harvard Students form Pro-Palestine Encampment

Protesters set up camp in Harvard Yard

Harvard Medalists

Three people honored for extraordinary service to the University

Talking About Tipping Points

Developing response capability for a climate emergency

Most popular

The Homelessness Public Health Crisis

Homelessness has surged in the United States, with devastating effects on the public health system.

Harvey Mansfield’s Last Class

After 60 years on the faculty, Harvard’s famous conservative is retiring.

More to explore

What is the Best Breakfast and Lunch in Harvard Square?

The cafés and restaurants of Harvard Square sure to impress for breakfast and lunch.

How Homelessness is a Public Health Crisis

Portfolio Diet May Reduce Long-Term Risk of Heart Disease and Stroke, Harvard Researchers Find

A little-known diet improves cardiovascular health through several distinct mechanisms.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 22 Apr 2024

- Research & Ideas

When Does Impact Investing Make the Biggest Impact?

More investors want to back businesses that contribute to social change, but are impact funds the only approach? Research by Shawn Cole, Leslie Jeng, Josh Lerner, Natalia Rigol, and Benjamin Roth challenges long-held assumptions about impact investing and reveals where such funds make the biggest difference.

- 27 Apr 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

Equity Bank CEO James Mwangi: Transforming Lives with Access to Credit

James Mwangi, CEO of Equity Bank, has transformed lives and livelihoods throughout East and Central Africa by giving impoverished people access to banking accounts and micro loans. He’s been so successful that in 2020 Forbes coined the term “the Mwangi Model.” But can we really have both purpose and profit in a firm? Harvard Business School professor Caroline Elkins, who has spent decades studying Africa, explores how this model has become one that business leaders are seeking to replicate throughout the world in her case, “A Marshall Plan for Africa': James Mwangi and Equity Group Holdings.” As part of a new first-year MBA course at Harvard Business School, this case examines the central question: what is the social purpose of the firm?

- 18 Apr 2023

The Best Person to Lead Your Company Doesn't Work There—Yet

Recruiting new executive talent to revive portfolio companies has helped private equity funds outperform major stock indexes, says research by Paul Gompers. Why don't more public companies go beyond their senior executives when looking for top leaders?

- 13 Dec 2022

The Color of Private Equity: Quantifying the Bias Black Investors Face

Prejudice persists in private equity, despite efforts to expand racial diversity in finance. Research by Josh Lerner sizes up the fundraising challenges and performance double standards that Black and Hispanic investors confront while trying to support other ventures—often minority-owned businesses.

- 30 Nov 2020

- Working Paper Summaries

Short-Termism, Shareholder Payouts, and Investment in the EU

Shareholder-driven “short-termism,” as evidenced by increasing payouts to shareholders, is said to impede long-term investment in EU public firms. But a deep dive into the data reveals a different story.

- 16 Nov 2020

Private Equity and COVID-19

Private equity investors are seeking new investments despite the pandemic. This study shows they are prioritizing revenue growth for value creation, giving larger equity stakes to management teams, and targeting somewhat lower returns.

- 13 Nov 2020

Long-Run Returns to Impact Investing in Emerging Markets and Developing Economies

Examination of every equity investment made by the International Finance Corporation, one of the largest and longest-operating impact investors, shows this portfolio has outperformed the S&P 500 by 15 percent.

- 13 Jan 2020

Do Private Equity Buyouts Get a Bad Rap?

Elizabeth Warren calls private equity buyouts "Wall Street looting," but a recent study by Josh Lerner and colleagues shows they have both positive and negative impacts. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Nov 2019

The Economic Effects of Private Equity Buyouts

Private equity buyouts are a major financial enterprise that critics see as dominated by rent-seeking activities with little in the way of societal benefits. This study of 6,000 US buyouts between 1980 and 2013 finds that the real side effects of buyouts on target firms and their workers vary greatly by deal type and market conditions.

- 16 Oct 2019

Core Earnings? New Data and Evidence

Using a novel dataset of earnings-related disclosures embedded in the 10-Ks, this paper shows how detailed financial statement analysis can produce a measure of core earnings that is more persistent than traditional earnings measures and forecasts future performance. Analysts and market participants are slow to appreciate the importance of transitory earnings.

- 19 Nov 2018

Lazy Prices

The most comprehensive information windows that firms provide to the markets—in the form of their mandated annual and quarterly filings—have changed dramatically over time, becoming significantly longer and more complex. When firms break from their routine phrasing and content, this action contains rich information for future firm stock returns and outcomes.

- 04 Sep 2018

Investing Outside the Box: Evidence from Alternative Vehicles in Private Capital

Private equity vehicles that differ from the traditional structure have become a major portion of investors’ portfolios, especially over the past decade. This study identifies differences in performance across limited and general partners participating in such vehicles, as well as across the two broad classes of alternative vehicles.

- 29 Aug 2018

How Much Does Your Boss Make? The Effects of Salary Comparisons

This study of more than 2,000 employees at a multibillion dollar firm explores how perceptions about peers’ and managers’ salaries affect employee behaviors and preferences for equity. Employees exhibit a high tolerance for inequality when job titles differ, which may explain why incentives are granted through promotions, and gender pay differences are most pronounced across positions.

- 12 Feb 2018

Private Equity, Jobs, and Productivity: Reply to Ayash and Rastad

In 2014, the authors published an influential analysis of private equity buyouts in the American Economic Review. Recently, economists Brian Ayash and Mahdi Rastad have challenged the accuracy of those findings. This new paper responds point by point to their critique, contending that it reflects a misunderstanding of the data and methodology behind the original study.

- 19 Sep 2017

An Invitation to Market Design

Effective market design can improve liquidity, efficiency, and equity in markets. This paper illustrates best practices in market design through three examples: the design of medical residency matching programs, a scrip system to allocate food donations to food banks, and the recent “Incentive Auction” that reallocated wireless spectrum from television broadcasters to telecoms.

- 28 Aug 2017

Should Industry Competitors Cooperate More to Solve World Problems?

George Serafeim has a theory that if industry competitors collaborated more, big world problems could start to be addressed. Is that even possible in a market economy? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 04 Aug 2017

Private Equity and Financial Fragility During the Crisis

Examining the activity of almost 500 private equity-backed companies during the 2008 financial crisis, this study finds that during a time in which capital formation dropped dramatically, PE-backed companies invested more aggressively than peer companies did. Results do not support the hypothesis that private equity contributed to the fragility of the economy during the recent financial crisis.

- 12 May 2017

Equality and Equity in Compensation

Why do some firms such as technology startups offer the same equity compensation packages to all new employees despite very different cash salaries? This paper presents evidence that workers dislike inequality in equity compensation more than salary compensation because of the perceived scarcity of equity.

- 03 May 2016

Pay Now or Pay Later? The Economics within the Private Equity Partnership

Partnerships are essential to the professional service and investment sectors. Yet the partnership structure raises issues including intergenerational continuity. This study of more than 700 private equity partnerships finds 1) the allocation of fund economics is typically weighted toward the founders of the firms, 2) the distributions of carried interest and ownership substantially affect the stability of the partnership, and 3) partners’ departures have a negative effect on private equity groups’ ability to raise additional funds.

- 15 Feb 2016

Replicating Private Equity with Value Investing, Homemade Leverage, and Hold-to-Maturity Accounting

This paper studies the asset selection of private equity investors and the risk and return properties of passive portfolios with similarly selected investments in publicly traded securities. Results indicate that sophisticated institutional investors appear to significantly overpay for the portfolio management services associated with private equity investments.

Ideas and insights from Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning

“Remember the Ladies:” Thinking about Women in the Workforce

As Women’s History Month winds down, I’ve been thinking a lot about women in the workforce. Not surprisingly, this thinking has been inextricably wound together with thoughts of the pandemic and the ongoing need to address issues of social justice. This year in particular, it’s hard to separate things out. But since this is the month in which we celebrate women, I’d like to take a look at things through the lens of women at work.

This has been a tough year for everyone, but when it comes to working, the negative impact on women has been significantly greater than it has been on men. Some of the data is truly startling. In Don’t Let the Pandemic Set Back Gender Equality , published in the Harvard Business Review last September, the authors shared analysis which found that, while women make up 39% of global employment, as of May 2020, they accounted for a staggering 54% of overall pandemic-related job loss.

For women still in the workforce, the pandemic is making things harder While many women have lost their jobs entirely, life in a time of pandemic is making things more difficult for women who remain in the workforce. This was detailed in the most recent Women in the Workplace Report , an annual study of corporate America conducted by McKinsey & Company and LeanIn.Org. One of their most interesting findings was that senior-level women “are 1.5 times more likely than senior-level men to think about downshifting their careers or leaving the workforce because of Covid-19. Almost 3 in 4 cite burnout as a main reason.” This is thanks to the additional caregiving burdens that have fallen on mothers with children at home during the pandemic.

This finding should be a wake-up call to organizations that they need to, in the 1776 words of Abigail Adams to her husband John, “remember the ladies.”

Why does this matter? And what can we do about it? It has been proven time and time again that organizations that leverage diversity at all levels perform better than those that do not. This is not, of course, confined to gender diversity. Racial diversity matters. A lot. As do age, geography, and socioeconomic and educational background. The more diverse, the better! But if the pandemic is driving women to draw back from the workforce, we need to take heed of this situation.

There’s no one simple fix to ensuring gender diversity, but there are a few steps organizations can make that will improve things for women in the workplace:

- Take advantage of technology: With millions of professionals working from home this past year, technology that enables meetings and collaboration has certainly been a major factor. Post-pandemic, technology can continue to support a more flexible work environment. But let’s make sure we’re taking advantage of technology, rather than having technology take advantage of us. Organizations should revise work policies and communications standards outlining expectations of when people need to be working. The fact that technology allows for “always-on” doesn’t mean that employees need to be available 24/7. Many organizations are starting to institute policies that establish timeout periods when employees are NOT expected to respond to calls, texts, and emails.

- Be flexible in terms of adapting to specific needs: Once corporate policies are revised, allow managers and employees to adapt them to their specific needs. For example, for one-on-one meetings, allow some latitude on meeting times that work best, which may not be during a typical 9-5 workday. And allowing for occasional non-video calls may take the pressure off mothers of young ones concerned that their children might make an unexpected guest appearance.

- Leverage diversity of thought: Organizations should be encouraging employees at all levels to innovate. Providing opportunities to do so can drive gender equity, both internally and externally. Instead of expecting the innovation hub or strategy team to come up with all the new ideas themselves, organizations should ask the people doing the work what would be most helpful for the company and for its customers. If you ask the women in your workforce for ideas on how your company can adapt existing products or services to drive gender equity, they’ll likely have plenty of good answers!

When it comes to women in the workforce, the pandemic is providing a good loud wake-up call. We don’t want to undo the progress that’s been made to date with respect to gender diversity.

What steps has your organization taken to help close the gender gap?

Ellen Bailey is senior advisor for diversity, inclusion, and belonging at Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning. Email her at [email protected] .

This post was originally published on OpenSesame.com .

Let’s talk

Change isn’t easy, but we can help. Together we’ll create informed and inspired leaders ready to shape the future of your business.

© 2024 Harvard Business School Publishing. All rights reserved. Harvard Business Publishing is an affiliate of Harvard Business School.

- Privacy Policy

- Copyright Information

- Terms of Use

- About Harvard Business Publishing

- Higher Education

- Harvard Business Review

- Harvard Business School

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience. By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Cookie and Privacy Settings

We may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds:

You can read about our cookies and privacy settings in detail on our Privacy Policy Page.

Tackling Diversity in Case Discussions

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

C ompanies with diverse teams—and diverse leaders—perform better and are more profitable . Yet many executives remain uncertain about what the secret sauce is for achieving the right balance of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

This confusion is shared by business educators, who not only struggle to adequately represent diversity in course materials , but also are apprehensive about conducting class discussions around diversity issues.

PRACTICAL TIPS ON FACILITATING DIVERSITY DISCUSSIONS

Zoe Kinias provides some practical advice for leading discussions in class on diversity, equity, and inclusion topics:

Be vulnerable ourselves. “There’s actually a lovely case on Microsoft about how Satya Nadella has done a great job of demonstrating to others how he would rather learn than be right,” says Kinias. “We can model this and encourage it in our classrooms.”

Ask the right questions. How do I ask the right questions to encourage additional input? How can I ask the questions in a way that enables empathy as opposed to defense? It’s subtle, says Kinias, but it’s about exploring other perspectives rather than establishing who is right.

Avoid the token trap. It can be tempting to ask the minority person or one of the few members of underrepresented groups to speak on behalf of their group. If they want to speak to their experience, this is of course important to encourage, says Kinias. But it can also be powerful when members of the majority group are able bring in their perspectives, “because they are aware as they talk with other folks and are generally empathetic.”

Get on common ground. Empathy is hugely important for handling these conversations, says Kinias. “Before we get into the details of the challenges with respect to a particular social identity or group status, I ask everyone to remember a time when they’ve been an insider and also a time when they’ve been an outsider. No matter what our demographic characteristics, everyone has felt both of those. Enabling everyone to recall what that feels like can help to set up for empathy.”

Find balance. Raising awareness of the particular challenges that members of underrepresented groups can face without problematizing their experience is an important thing to carefully balance.

Designate support. INSEAD instituted diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) representatives within MBA classes. These student representatives add additional perspectives and support to help maximize the management of these conversations and increase the learning.

Having tough conversations with students on diversity issues and interpreting business cases through the lenses of gender and race are not skills most educators are taught. Business schools must do a better job of providing adequate resources for professors—such as gender-specific leadership training, professional mentors, and variety in teaching tools—or provide incentives to diversify their course materials.

In schools where this support is lacking, faculty should lead the way. “Educators who take the responsibility of developing future leaders seriously can do a lot on their own,” says Zoe Kinias, Associate Professor of organizational behavior at INSEAD and the Academic Director of INSEAD’s Gender Initiative.

INSEAD hosts gender balance teaching sessions for faculty in the school’s campuses in both Singapore and Fontainebleau. “We are trying to help to facilitate some general awareness and also have conversations about what to do in some of these challenging situations for faculty of all disciplines,” she says.

Emphasizing That Leadership Is Diverse

Students at INSEAD want more diverse case protagonists. “This is something we hear in our face-to-face interactions and also something we saw in [a recent] gender climate survey,” says Kinias.

In addition to ensuring that a variety of case protagonists are presented to students, Kinias says, it’s equally important to use cases that highlight challenges for members of underrepresented groups as well as ones that show that there are diverse ways of enacting leadership. “This could be a male protagonist who has a bit of a softer side or has work/life challenges he’s coping with, as opposed to just sticking with stereotype-reinforcing protagonists from diverse backgrounds.”

Another way to bring these issues forward in class is to embed opportunities to discuss this kind of content. In an entrepreneurship class, for instance, have a discussion with students about the lack of well-funded female entrepreneurs. Bring in female guest speakers. Really challenge the class to think about what could be different in the scenarios being discussed, Kinias suggests.

Classroom management is also important. Educators need to learn more about issues concerning stereotypes, microaggressions, and subtle power signaling. They must also be able to introduce questions along these lines and respond effectively when students bring them up, says Kinias.

“Every conversation we have—especially on issues that I teach around ethics and corporate responsibility—if we’re honest and engaged in it candidly, should take students to a point where they are potentially uncomfortable.” Nien-hê Hsieh

Tips for Leading Class Discussions Through a Diverse Lens

Exposing students to a greater variety of leaders and management styles not only helps to develop them into future leaders who value inclusivity, but also prepares them to be more comfortable addressing these issues.

“This has a lot to do with psychological safety,” says Kinias. “We’re trying to create an environment in which students are expanding their perspective and exploring ideas. It’s OK not to have the answers in the beginning, but rather focus on engaging in exploratory conversations that involve trying to learn from each other within the classroom context.”

Cases, whether directly focused on diversity issues or not, help students to think through the challenges of managing with respect to diversity and also find solutions. In his ethics and corporate accountability classes at Harvard Business School, Professor Nien-hê Hsieh uses a case he wrote on the well-known Google diversity dispute in which the tech giant fired a top engineer who wrote a memo critical of the company’s diversity efforts.

“The case is meant to examine two sides of the issue—if we think that diversity of opinion and open debate is important for innovation on the one hand, how do you then navigate that while at the same time wanting to ensure that the way people engage in conversations and the general culture in which people engage with one another is one in which people feel comfortable and not threatened,” says Hsieh. “That’s a general issue that all organizations face.”

The case also touches on gender equity challenges in the context of Google, tech firms, and the workplace more generally, as well as how we think about free speech in a way that creates balance and a safe environment for people to engage with one another. An extension of that effort involves looking more generally at issues of race and how to achieve more racial equity, he says. “I also want students to understand, at least in the American context, the extent to which workers are or are not protected with regard to free speech, and other things as well.”

Be Willing to Be Uncomfortable

In navigating difficult classroom discussions, an educator may be inclined to flag them, call them out in advance, and then remind the group to engage respectfully, says Hsieh. However, that can actually be counterproductive.

“Every conversation we have—especially on issues that I teach around ethics and corporate responsibility—if we’re honest and engaged in it candidly, should take students to a point where they are potentially uncomfortable,” he explains. “In that sense, we don’t want to single this out as something different. If we’re really trying to get at these issues and learn about them and learn more about ourselves, we have to be willing to open ourselves up to engage in difficult conversations and be willing to accept the possibility that people may say things that we really disagree with, and be careful about how we talk about things.”

Be an Advocate for Respectful Discourse

Hsieh makes sure to instill this culture of respect right from the start. If a sensitivity or personal experience does require acknowledgement, he creates space for that in the moment by reminding the class to approach it in the same spirit of openness, engagement, and respect as they do in all conversations. He also lets students know there are standards for how they should engage.

“It’s good for students to engage and debate with one another,” he says. “My role as an instructor is to create the space for that to happen, but also knowing when to stop.”

Be Clear About Objectives

Hsieh also ensures he is clear about his objectives for every discussion. What are the challenges or questions that we want to understand? “It’s not just learning about something,” he says. “It’s actually learning what they can do or how they can effect change or make judgements.”

Be a Good Listener

Once objectives are clear, educators should listen. “When a student knows I’m actively listening, that’s the first step for opening up the environment for students to have these kinds of difficult conversations,” says Hsieh. “And by active listening I mean being willing to give them the benefit of the doubt and really trying to understand where they’re coming from. Not simply imposing my own lens on what they’re saying.”

Be Careful About the Kinds of Questions You Ask

Both in terms of opening up the discussion and also in terms of follow up, educators should be mindful about the questions they ask. “A question we ask [as educators] is in a sense a permission to speak on a certain topic,” he says. “Being precise in what we’re asking students to engage with actually comes from being very precise with the questions.”

“We’re trying to create an environment in which students are defending their perspective and exploring ideas. It’s OK not to have the answers in the beginning, but rather focus on engaging in exploratory conversations that really involve trying to learn from each other with the classroom context.” Zoe Kinias

Making Business Leadership More Inclusive

The most effective use of class time is for students to do something they can’t do on their own, “where students come together, and by the end of class, collectively as a group, have come to some greater understanding,” says Hsieh. “And individually, we have come to something—either we’ve understood ourselves better or something about each other better.”

Educators—and business schools—worldwide who are taking strides toward more diversity and inclusivity are making progress, says Kinias.

“We are energized, and this has enabled us to engage with the students and with our colleagues in a way that can really improve the situation across all of our schools,” she says. “Really, we are trying to make business leadership more inclusive through the students whose lives we touch while they’re at our school. I’m optimistic that we are moving in the right direction.”

Colleen Ammerman works with the faculty leadership of the Harvard Business School Race, Gender & Equity Initiative to support a research community and a platform for disseminating practice-relevant insights for advancing equity, diversity, and inclusion in organizations. She is a member of the Life & Leadership After HBS research team, an ongoing longitudinal study of Harvard Business School alumni which examines the influence of gender and race on their life and career outcomes. She is also coauthor, with Boris Groysberg, of Glass Half Broken: Shattering the Barriers That Still Hold Women Back at Work (Harvard Business Review Press 2021).

Zoe Kinias is an associate professor of organizational behavior at INSEAD and the academic director of INSEAD’s Gender Initiative. She is also a member of the INSEAD Randomized Control Trials Lab. Her teaching topics focus on leadership development, social issues at the intersection of business and society, and psychological research in applied/business contexts.

Nien-hê Hsieh is a professor of business administration and Joseph L. Rice, III Faculty Fellow in the general management unit at Harvard Business School. His research concerns ethical issues in business and the responsibilities of global business leaders, and it centers on the question of whether and how managers are guided by not only considerations of economic efficiency, but also by values such as freedom and fairness and respect for basic rights.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Can we talk?

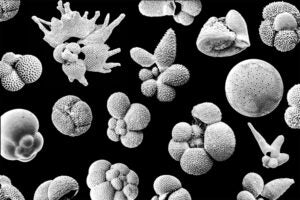

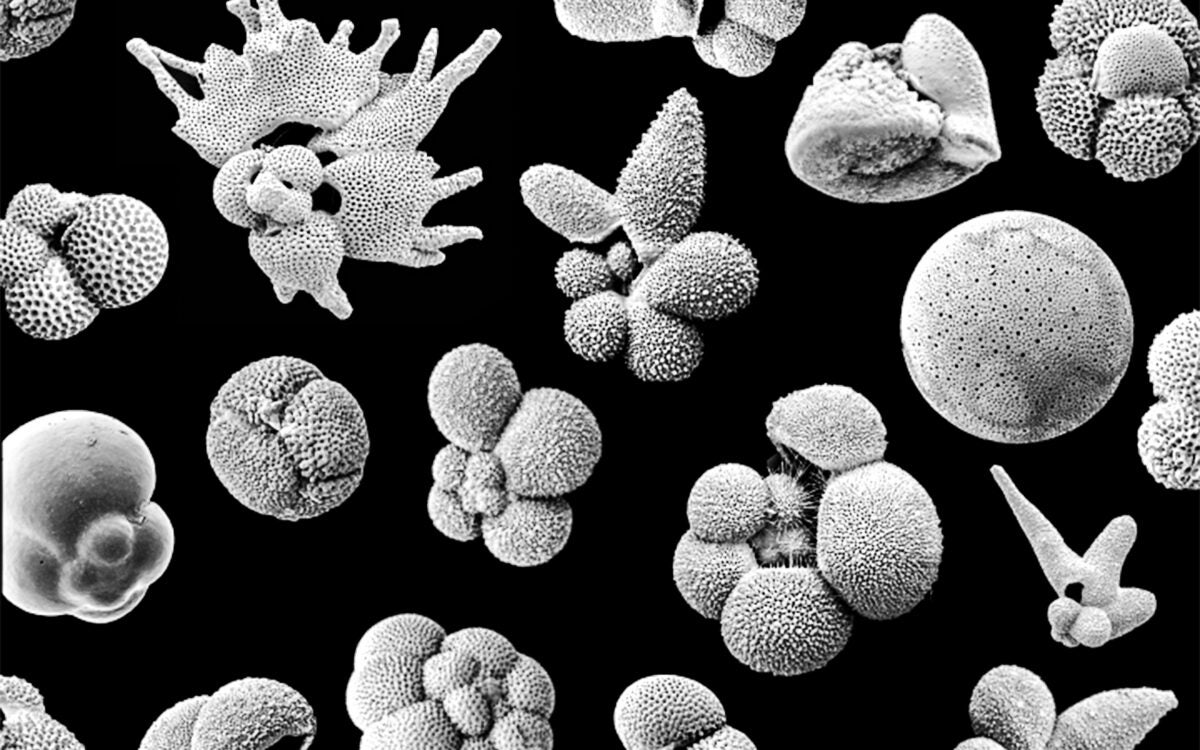

Early warning sign of extinction?

Remember Eric Garner? George Floyd?

Harvard business school launches race, gender, and equity initiative.

Harvard University. Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard Business School (HBS) announced today the formation of the Race, Gender, and Equity Initiative , which is both a renaming of the Gender Initiative and a reflection of work it has done and will do to understand and advance equality, including racial equality, in organizations and business. The role of the initiative, much like the Gender Initiative before it, will be to catalyze and translate cutting-edge research to transform practice, enable leaders to drive change, and eradicate gender, race, and other forms of inequality in business and society.

“It’s a particularly opportune moment for this transition,” noted Dean Srikant Datar. “Two years ago the School announced its Advancing Racial Equity action plan, which advocated for the formation of this initiative as well as the launch of an Office for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion to be led by our first chief diversity and inclusion officer. These two new entities will be important pillars — spurring work both inside Harvard Business School and with alumni and other business leaders in a range of organizations and settings.”

Although the work of the Gender Initiative was never limited to gender alone, it was an anchor point for the initiative’s launch and early years. Theinitiative was established during the 2014-15 academic year, following the School’s commemoration of 50 years of women at HBS. At the time, there were a number of faculty publishing important new research on gender and a vibrant conversation about gender inequality, and what research activities might fuel advances in the field.

The new name better reflects the work undertaken by the initiative, going back to some of its earliest conferences as well as more recent events , projects , and collaborations , comments director Colleen Ammerman.

“As an initiative, we are ‘research-fueled,’ and research on race and other areas of inequality like social class and sexual orientation has expanded since the initiative’s launch. It makes sense that our name aligns with that current state,” Ammerman explained. “We hope this change helps us to engage effectively with leaders and organizations working to advance diversity and equity.”

“We are calling out race and gender as two important axes of inequality the School is committed to addressing, but also want to be clear that other areas are being, and will continue to be, taken up by the School and its faculty,” noted Robin Ely, the Diane Doerge Wilson Professor of Business Administration and faculty chair of the initiative. “Our faculty pursue research in a wide range of fields related to equity, creating knowledge that helps leaders drive change in their organizations and the world.”

This year, the initiative will be partnering with the Institute for Business in Global Society (BiGS). The institute provides a research-based platform to address critical business and societal issues, and the Race, Gender, and Equity Initiative will work closely with this year’s cohort of BiGS Fellows , scholarly researchers who join the School to work on specific projects related to issues of business and society.

Share this article

You might like.

Study finds that conversation – even online – could be an effective strategy to help prevent cognitive decline and dementia

Fossil record stretching millions of years shows tiny ocean creatures on the move before Earth heats up

Mother, uncle of two whose deaths at hands of police officers ignited movement talk about turning pain into activism, keeping hope alive

Exercise cuts heart disease risk in part by lowering stress, study finds

Benefits nearly double for people with depression

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

- Utility Menu

harvardchan_logo.png

Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Case-Based Teaching & Learning Initiative

Teaching cases & active learning resources for public health education, case compendium, university of california berkeley haas school of business center for equity, gender & leadership.

Visit website

Using our case library

Access to cases.

Many of our cases are available for sale through Harvard Business Publishing in the Harvard T.H. Chan case collection . Others are free to download through this website .

Cases in this collection may be used free of charge by Harvard Chan course instructors in their teaching. Contact Allison Bodznick , Harvard Chan Case Library administrator, for access.

Access to teaching notes

Teaching notes are available as supporting material to many of the cases in the Harvard Chan Case Library. Teaching notes provide an overview of the case and suggested discussion questions, as well as a roadmap for using the case in the classroom.

Access to teaching notes is limited to course instructors only.

- Teaching notes for cases available through Harvard Business Publishing may be downloaded after registering for an Educator account .

- To request teaching notes for cases that are available for free through this website, look for the "Teaching note available for faculty/instructors " link accompanying the abstract for the case you are interested in; you'll be asked to complete a brief survey verifying your affiliation as an instructor.

Using the Harvard Business Publishing site

Faculty and instructors with university affiliations can register for Educator access on the Harvard Business Publishing website, where many of our cases are available . An Educator account provides access to teaching notes, full-text review copies of cases, articles, simulations, course planning tools, and discounted pricing for your students.

Filter cases

Case format.

- Case (116) Apply Case filter

- Case book (5) Apply Case book filter

- Case collection (2) Apply Case collection filter

- Industry or background note (1) Apply Industry or background note filter

- Simulation or role play (4) Apply Simulation or role play filter

- Teaching example (1) Apply Teaching example filter

- Teaching pack (2) Apply Teaching pack filter

Case availability & pricing

- Available for purchase from Harvard Business Publishing (73) Apply Available for purchase from Harvard Business Publishing filter

- Download free of charge (50) Apply Download free of charge filter

- Request from author (4) Apply Request from author filter

Case discipline/subject

- Child & adolescent health (15) Apply Child & adolescent health filter

- Maternal & child health (1) Apply Maternal & child health filter

- Human rights & health (11) Apply Human rights & health filter

- Women, gender, & health (11) Apply Women, gender, & health filter

- Social & behavioral sciences (41) Apply Social & behavioral sciences filter

- Social innovation & entrepreneurship (11) Apply Social innovation & entrepreneurship filter

- Finance & accounting (10) Apply Finance & accounting filter

- Environmental health (12) Apply Environmental health filter

- Epidemiology (6) Apply Epidemiology filter

- Ethics (5) Apply Ethics filter

- Global health (28) Apply Global health filter

- Health policy (35) Apply Health policy filter

- Healthcare management (55) Apply Healthcare management filter

- Life sciences (5) Apply Life sciences filter

- Marketing (15) Apply Marketing filter

- Multidisciplinary (16) Apply Multidisciplinary filter

- Nutrition (6) Apply Nutrition filter

- Population health (8) Apply Population health filter

- Quality improvement (4) Apply Quality improvement filter

- Quantative methods (3) Apply Quantative methods filter

- Social medicine (7) Apply Social medicine filter

- Technology (6) Apply Technology filter

Geographic focus

- Cambodia (1) Apply Cambodia filter

- Australia (1) Apply Australia filter

- Bangladesh (2) Apply Bangladesh filter

- China (1) Apply China filter

- Egypt (1) Apply Egypt filter

- El Salvador (1) Apply El Salvador filter

- Guatemala (2) Apply Guatemala filter

- Haiti (2) Apply Haiti filter

- Honduras (1) Apply Honduras filter

- India (3) Apply India filter

- International/multiple countries (11) Apply International/multiple countries filter

- Israel (3) Apply Israel filter

- Japan (2) Apply Japan filter

- Kenya (2) Apply Kenya filter

- Liberia (1) Apply Liberia filter

- Mexico (4) Apply Mexico filter

- Nigeria (1) Apply Nigeria filter

- Pakistan (1) Apply Pakistan filter

- Philippines (1) Apply Philippines filter

- Rhode Island (1) Apply Rhode Island filter

- South Africa (2) Apply South Africa filter

- Turkey (1) Apply Turkey filter

- Uganda (2) Apply Uganda filter

- United Kingdom (2) Apply United Kingdom filter

- United States (63) Apply United States filter

- California (6) Apply California filter

- Colorado (2) Apply Colorado filter

- Connecticut (1) Apply Connecticut filter

- Louisiana (1) Apply Louisiana filter

- Maine (1) Apply Maine filter

- Massachusetts (14) Apply Massachusetts filter

- Michigan (1) Apply Michigan filter

- Minnesota (1) Apply Minnesota filter