- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Trans kids’ treatment can start younger, new guidelines say

This photo provided by Laura Short shows Eli Bundy on April 15, 2022 at Deception Pass in Washington. In South Carolina, where a proposed law would ban transgender treatments for kids under age 18, Eli Bundy hopes to get breast removal surgery next year before college. Bundy, 18, who identifies as nonbinary, supports updated guidance from an international transgender health group that recommends lower ages for some treatments. (Laura Short via AP)

FILE - Dr. David Klein, right, an Air Force Major and chief of adolescent medicine at Fort Belvoir Community Hospital, listens as Amanda Brewer, left, speaks with her daughter, Jenn Brewer, 13, as the teenager has blood drawn during a monthly appointment for monitoring her treatment at the hospital in Fort Belvoir, Va., on Sept. 7, 2016. Brewer is transitioning from male to female. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

- Copy Link copied

A leading transgender health association has lowered its recommended minimum age for starting gender transition treatment, including sex hormones and surgeries.

The World Professional Association for Transgender Health said hormones could be started at age 14, two years earlier than the group’s previous advice, and some surgeries done at age 15 or 17, a year or so earlier than previous guidance. The group acknowledged potential risks but said it is unethical and harmful to withhold early treatment.

The association provided The Associated Press with an advance copy of its update ahead of publication in a medical journal, expected later this year. The international group promotes evidence-based standards of care and includes more than 3,000 doctors, social scientists and others involved in transgender health issues.

The update is based on expert opinion and a review of scientific evidence on the benefits and harms of transgender medical treatment in teens whose gender identity doesn’t match the sex they were assigned at birth, the group said. Such evidence is limited but has grown in the last decade, the group said, with studies suggesting the treatments can improve psychological well-being and reduce suicidal behavior.

Starting treatment earlier allows transgender teens to experience physical puberty changes around the same time as other teens, said Dr. Eli Coleman, chair of the group’s standards of care and director of the University of Minnesota Medical School’s human sexuality program.

But he stressed that age is just one factor to be weighed. Emotional maturity, parents’ consent, longstanding gender discomfort and a careful psychological evaluation are among the others.

“Certainly there are adolescents that do not have the emotional or cognitive maturity to make an informed decision,” he said. “That is why we recommend a careful multidisciplinary assessment.”

The updated guidelines include recommendations for treatment in adults, but the teen guidance is bound to get more attention. It comes amid a surge in kids referred to clinics offering transgender medical treatment , along with new efforts to prevent or restrict the treatment.

Many experts say more kids are seeking such treatment because gender-questioning children are more aware of their medical options and facing less stigma.

Critics, including some from within the transgender treatment community, say some clinics are too quick to offer irreversible treatment to kids who would otherwise outgrow their gender-questioning.

Psychologist Erica Anderson resigned her post as a board member of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health last year after voicing concerns about “sloppy” treatment given to kids without adequate counseling.

She is still a group member and supports the updated guidelines, which emphasize comprehensive assessments before treatment. But she says dozens of families have told her that doesn’t always happen.

“They tell me horror stories. They tell me, ‘Our child had 20 minutes with the doctor’” before being offered hormones, she said. “The parents leave with their hair on fire.’’

Estimates on the number of transgender youth and adults worldwide vary, partly because of different definitions. The association’s new guidelines say data from mostly Western countries suggest a range of between a fraction of a percent in adults to up to 8% in kids.

Anderson said she’s heard recent estimates suggesting the rate in kids is as high as 1 in 5 — which she strongly disputes. That number likely reflects gender-questioning kids who aren’t good candidates for lifelong medical treatment or permanent physical changes, she said.

Still, Anderson said she condemns politicians who want to punish parents for allowing their kids to receive transgender treatment and those who say treatment should be banned for those under age 18.

“That’s just absolutely cruel,’’ she said.

Dr. Marci Bowers, the transgender health group’s president-elect, also has raised concerns about hasty treatment, but she acknowledged the frustration of people who have been “forced to jump through arbitrary hoops and barriers to treatment by gatekeepers ... and subjected to scrutiny that is not applied to another medical diagnosis.’’

Gabe Poulos, 22, had breast removal surgery at age 16 and has been on sex hormones for seven years. The Asheville, North Carolina, resident struggled miserably with gender discomfort before his treatment.

Poulos said he’s glad he was able to get treatment at a young age.

“Transitioning under the roof with your parents so they can go through it with you, that’s really beneficial,’’ he said. “I’m so much happier now.’’

In South Carolina, where a proposed law would ban transgender treatments for kids under age 18, Eli Bundy has been waiting to get breast removal surgery since age 15. Now 18, Bundy just graduated from high school and is planning to have surgery before college.

Bundy, who identifies as nonbinary, supports easing limits on transgender medical care for kids.

“Those decisions are best made by patients and patient families and medical professionals,’’ they said. “It definitely makes sense for there to be fewer restrictions, because then kids and physicians can figure it out together.’’

Dr. Julia Mason, an Oregon pediatrician who has raised concerns about the increasing numbers of youngsters who are getting transgender treatment, said too many in the field are jumping the gun. She argues there isn’t strong evidence in favor of transgender medical treatment for kids.

“In medicine ... the treatment has to be proven safe and effective before we can start recommending it,’’ Mason said.

Experts say the most rigorous research — studies comparing treated kids with outcomes in untreated kids — would be unethical and psychologically harmful to the untreated group.

The new guidelines include starting medication called puberty blockers in the early stages of puberty, which for girls is around ages 8 to 13 and typically two years later for boys. That’s no change from the group’s previous guidance. The drugs delay puberty and give kids time to decide about additional treatment; their effects end when the medication is stopped.

The blockers can weaken bones, and starting them too young in children assigned males at birth might impair sexual function in adulthood, although long-term evidence is lacking.

The update also recommends:

—Sex hormones — estrogen or testosterone — starting at age 14. This is often lifelong treatment. Long-term risks may include infertility and weight gain, along with strokes in trans women and high blood pressure in trans men, the guidelines say.

—Breast removal for trans boys at age 15. Previous guidance suggested this could be done at least a year after hormones, around age 17, although a specific minimum ag wasn’t listed.

—Most genital surgeries starting at age 17, including womb and testicle removal, a year earlier than previous guidance.

The Endocrine Society, another group that offers guidance on transgender treatment, generally recommends starting a year or two later, although it recently moved to start updating its own guidelines. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Medical Association support allowing kids to seek transgender medical treatment, but they don’t offer age-specific guidance.

Dr. Joel Frader, a Northwestern University a pediatrician and medical ethicist who advises a gender treatment program at Chicago’s Lurie Children’s Hospital, said guidelines should rely on psychological readiness, not age.

Frader said brain science shows that kids are able to make logical decisions by around age 14, but they’re prone to risk-taking and they take into account long-term consequences of their actions only when they’re much older.

Coleen Williams, a psychologist at Boston Children’s Hospital’s Gender Multispecialty Service, said treatment decisions there are collaborative and individualized.

“Medical intervention in any realm is not a one-size-fits-all option,” Williams said.

Follow AP Medical Writer Lindsey Tanner at @LindseyTanner.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Feminizing hormone therapy

Feminizing hormone therapy typically is used by transgender women and nonbinary people to produce physical changes in the body that are caused by female hormones during puberty. Those changes are called secondary sex characteristics. This hormone therapy helps better align the body with a person's gender identity. Feminizing hormone therapy also is called gender-affirming hormone therapy.

Feminizing hormone therapy involves taking medicine to block the action of the hormone testosterone. It also includes taking the hormone estrogen. Estrogen lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes. It also triggers the development of feminine secondary sex characteristics. Feminizing hormone therapy can be done alone or along with feminizing surgery.

Not everybody chooses to have feminizing hormone therapy. It can affect fertility and sexual function, and it might lead to health problems. Talk with your health care provider about the risks and benefits for you.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Available Sexual Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Feminizing hormone therapy is used to change the body's hormone levels. Those hormone changes trigger physical changes that help better align the body with a person's gender identity.

In some cases, people seeking feminizing hormone therapy experience discomfort or distress because their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth or from their sex-related physical characteristics. This condition is called gender dysphoria.

Feminizing hormone therapy can:

- Improve psychological and social well-being.

- Ease psychological and emotional distress related to gender.

- Improve satisfaction with sex.

- Improve quality of life.

Your health care provider might advise against feminizing hormone therapy if you:

- Have a hormone-sensitive cancer, such as prostate cancer.

- Have problems with blood clots, such as when a blood clot forms in a deep vein, a condition called deep vein thrombosis, or a there's a blockage in one of the pulmonary arteries of the lungs, called a pulmonary embolism.

- Have significant medical conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Have behavioral health conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Have a condition that limits your ability to give your informed consent.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

Stay Informed with LGBTQ+ health content.

Receive trusted health information and answers to your questions about sexual orientation, gender identity, transition, self-expression, and LGBTQ+ health topics. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing to our LGBTQ+ newsletter.

You will receive the first newsletter in your inbox shortly. This will include exclusive health content about the LGBTQ+ community from Mayo Clinic.

If you don't receive our email within 5 minutes, check your SPAM folder, then contact us at [email protected] .

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Research has found that feminizing hormone therapy can be safe and effective when delivered by a health care provider with expertise in transgender care. Talk to your health care provider about questions or concerns you have regarding the changes that will happen in your body as a result of feminizing hormone therapy.

Complications can include:

- Blood clots in a deep vein or in the lungs

- Heart problems

- High levels of triglycerides, a type of fat, in the blood

- High levels of potassium in the blood

- High levels of the hormone prolactin in the blood

- Nipple discharge

- Weight gain

- Infertility

- High blood pressure

- Type 2 diabetes

Evidence suggests that people who take feminizing hormone therapy may have an increased risk of breast cancer when compared to cisgender men — men whose gender identity aligns with societal norms related to their sex assigned at birth. But the risk is not greater than that of cisgender women.

To minimize risk, the goal for people taking feminizing hormone therapy is to keep hormone levels in the range that's typical for cisgender women.

Feminizing hormone therapy might limit your fertility. If possible, it's best to make decisions about fertility before starting treatment. The risk of permanent infertility increases with long-term use of hormones. That is particularly true for those who start hormone therapy before puberty begins. Even after stopping hormone therapy, your testicles might not recover enough to ensure conception without infertility treatment.

If you want to have biological children, talk to your health care provider about freezing your sperm before you start feminizing hormone therapy. That procedure is called sperm cryopreservation.

How you prepare

Before you start feminizing hormone therapy, your health care provider assesses your health. This helps address any medical conditions that might affect your treatment. The evaluation may include:

- A review of your personal and family medical history.

- A physical exam.

- A review of your vaccinations.

- Screening tests for some conditions and diseases.

- Identification and management, if needed, of tobacco use, drug use, alcohol use disorder, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections.

- Discussion about sperm freezing and fertility.

You also might have a behavioral health evaluation by a provider with expertise in transgender health. The evaluation may assess:

- Gender identity.

- Gender dysphoria.

- Mental health concerns.

- Sexual health concerns.

- The impact of gender identity at work, at school, at home and in social settings.

- Risky behaviors, such as substance use or use of unapproved silicone injections, hormone therapy or supplements.

- Support from family, friends and caregivers.

- Your goals and expectations of treatment.

- Care planning and follow-up care.

People younger than age 18, along with a parent or guardian, should see a medical care provider and a behavioral health provider with expertise in pediatric transgender health to discuss the risks and benefits of hormone therapy and gender transitioning in that age group.

What you can expect

You should start feminizing hormone therapy only after you've had a discussion of the risks and benefits as well as treatment alternatives with a health care provider who has expertise in transgender care. Make sure you understand what will happen and get answers to any questions you may have before you begin hormone therapy.

Feminizing hormone therapy typically begins by taking the medicine spironolactone (Aldactone). It blocks male sex hormone receptors — also called androgen receptors. This lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes.

About 4 to 8 weeks after you start taking spironolactone, you begin taking estrogen. This also lowers the amount of testosterone the body makes. And it triggers physical changes in the body that are caused by female hormones during puberty.

Estrogen can be taken several ways. They include a pill and a shot. There also are several forms of estrogen that are applied to the skin, including a cream, gel, spray and patch.

It is best not to take estrogen as a pill if you have a personal or family history of blood clots in a deep vein or in the lungs, a condition called venous thrombosis.

Another choice for feminizing hormone therapy is to take gonadotropin-releasing hormone (Gn-RH) analogs. They lower the amount of testosterone your body makes and might allow you to take lower doses of estrogen without the use of spironolactone. The disadvantage is that Gn-RH analogs usually are more expensive.

After you begin feminizing hormone therapy, you'll notice the following changes in your body over time:

- Fewer erections and a decrease in ejaculation. This will begin 1 to 3 months after treatment starts. The full effect will happen within 3 to 6 months.

- Less interest in sex. This also is called decreased libido. It will begin 1 to 3 months after you start treatment. You'll see the full effect within 1 to 2 years.

- Slower scalp hair loss. This will begin 1 to 3 months after treatment begins. The full effect will happen within 1 to 2 years.

- Breast development. This begins 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. The full effect happens within 2 to 3 years.

- Softer, less oily skin. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. That's also when the full effect will happen.

- Smaller testicles. This also is called testicular atrophy. It begins 3 to 6 months after the start of treatment. You'll see the full effect within 2 to 3 years.

- Less muscle mass. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. You'll see the full effect within 1 to 2 years.

- More body fat. This will begin 3 to 6 months after treatment starts. The full effect will happen within 2 to 5 years.

- Less facial and body hair growth. This will begin 6 to 12 months after treatment starts. The full effect happens within three years.

Some of the physical changes caused by feminizing hormone therapy can be reversed if you stop taking it. Others, such as breast development, cannot be reversed.

While on feminizing hormone therapy, you meet regularly with your health care provider to:

- Keep track of your physical changes.

- Monitor your hormone levels. Over time, your hormone dose may need to change to ensure you are taking the lowest dose necessary to get the physical effects that you want.

- Have blood tests to check for changes in your cholesterol, blood sugar, blood count, liver enzymes and electrolytes that could be caused by hormone therapy.

- Monitor your behavioral health.

You also need routine preventive care. Depending on your situation, this may include:

- Breast cancer screening. This should be done according to breast cancer screening recommendations for cisgender women your age.

- Prostate cancer screening. This should be done according to prostate cancer screening recommendations for cisgender men your age.

- Monitoring bone health. You should have bone density assessment according to the recommendations for cisgender women your age. You may need to take calcium and vitamin D supplements for bone health.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Feminizing hormone therapy care at Mayo Clinic

- Tangpricha V, et al. Transgender women: Evaluation and management. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Medical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Oct. 10, 2022.

- Coleman E, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022; doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

- AskMayoExpert. Gender-affirming hormone therapy (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Nippoldt TB (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Sept. 29, 2022.

- Gender dysphoria

- Doctors & Departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Supplements

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Gender Confirmation Surgery (GCS)

What is Gender Confirmation Surgery?

- Transfeminine Tr

Transmasculine Transition

- Traveling Abroad

Choosing a Surgeon

Gender confirmation surgery (GCS), known clinically as genitoplasty, are procedures that surgically confirm a person's gender by altering the genitalia and other physical features to align with their desired physical characteristics. Gender confirmation surgeries are also called gender affirmation procedures. These are both respectful terms.

Gender dysphoria , an experience of misalignment between gender and sex, is becoming more widely diagnosed. People diagnosed with gender dysphoria are often referred to as "transgender," though one does not necessarily need to experience gender dysphoria to be a member of the transgender community. It is important to note there is controversy around the gender dysphoria diagnosis. Many disapprove of it, noting that the diagnosis suggests that being transgender is an illness.

Ellen Lindner / Verywell

Transfeminine Transition

Transfeminine is a term inclusive of trans women and non-binary trans people assigned male at birth.

Gender confirmation procedures that a transfeminine person may undergo include:

- Penectomy is the surgical removal of external male genitalia.

- Orchiectomy is the surgical removal of the testes.

- Vaginoplasty is the surgical creation of a vagina.

- Feminizing genitoplasty creates internal female genitalia.

- Breast implants create breasts.

- Gluteoplasty increases buttock volume.

- Chondrolaryngoplasty is a procedure on the throat that can minimize the appearance of Adam's apple .

Feminizing hormones are commonly used for at least 12 months prior to breast augmentation to maximize breast growth and achieve a better surgical outcome. They are also often used for approximately 12 months prior to feminizing genital surgeries.

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) is often done to soften the lines of the face. FFS can include softening the brow line, rhinoplasty (nose job), smoothing the jaw and forehead, and altering the cheekbones. Each person is unique and the procedures that are done are based on the individual's need and budget,

Transmasculine is a term inclusive of trans men and non-binary trans people assigned female at birth.

Gender confirmation procedures that a transmasculine person may undergo include:

- Masculinizing genitoplasty is the surgical creation of external genitalia. This procedure uses the tissue of the labia to create a penis.

- Phalloplasty is the surgical construction of a penis using a skin graft from the forearm, thigh, or upper back.

- Metoidioplasty is the creation of a penis from the hormonally enlarged clitoris.

- Scrotoplasty is the creation of a scrotum.

Procedures that change the genitalia are performed with other procedures, which may be extensive.

The change to a masculine appearance may also include hormone therapy with testosterone, a mastectomy (surgical removal of the breasts), hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus), and perhaps additional cosmetic procedures intended to masculinize the appearance.

Paying For Gender Confirmation Surgery

Medicare and some health insurance providers in the United States may cover a portion of the cost of gender confirmation surgery.

It is unlawful to discriminate or withhold healthcare based on sex or gender. However, many plans do have exclusions.

For most transgender individuals, the burden of financing the procedure(s) is the main difficulty in obtaining treatment. The cost of transitioning can often exceed $100,000 in the United States, depending upon the procedures needed.

A typical genitoplasty alone averages about $18,000. Rhinoplasty, or a nose job, averaged $5,409 in 2019.

Traveling Abroad for GCS

Some patients seek gender confirmation surgery overseas, as the procedures can be less expensive in some other countries. It is important to remember that traveling to a foreign country for surgery, also known as surgery tourism, can be very risky.

Regardless of where the surgery will be performed, it is essential that your surgeon is skilled in the procedure being performed and that your surgery will be performed in a reputable facility that offers high-quality care.

When choosing a surgeon , it is important to do your research, whether the surgery is performed in the U.S. or elsewhere. Talk to people who have already had the procedure and ask about their experience and their surgeon.

Before and after photos don't tell the whole story, and can easily be altered, so consider asking for a patient reference with whom you can speak.

It is important to remember that surgeons have specialties and to stick with your surgeon's specialty. For example, you may choose to have one surgeon perform a genitoplasty, but another to perform facial surgeries. This may result in more expenses, but it can result in a better outcome.

A Word From Verywell

Gender confirmation surgery is very complex, and the procedures that one person needs to achieve their desired result can be very different from what another person wants.

Each individual's goals for their appearance will be different. For example, one individual may feel strongly that breast implants are essential to having a desirable and feminine appearance, while a different person may not feel that breast size is a concern. A personalized approach is essential to satisfaction because personal appearance is so highly individualized.

Davy Z, Toze M. What is gender dysphoria? A critical systematic narrative review . Transgend Health . 2018;3(1):159-169. doi:10.1089/trgh.2018.0014

Morrison SD, Vyas KS, Motakef S, et al. Facial Feminization: Systematic Review of the Literature . Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(6):1759-70. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002171

Hadj-moussa M, Agarwal S, Ohl DA, Kuzon WM. Masculinizing Genital Gender Confirmation Surgery . Sex Med Rev . 2019;7(1):141-155. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.06.004

Dowshen NL, Christensen J, Gruschow SM. Health Insurance Coverage of Recommended Gender-Affirming Health Care Services for Transgender Youth: Shopping Online for Coverage Information . Transgend Health . 2019;4(1):131-135. doi:10.1089/trgh.2018.0055

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Rhinoplasty nose surgery .

Rights Group: More U.S. Companies Covering Cost of Gender Reassignment Surgery. CNS News. http://cnsnews.com/news/article/rights-group-more-us-companies-covering-cost-gender-reassignment-surgery

The Sex Change Capital of the US. CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-3445_162-4423154.html

By Jennifer Whitlock, RN, MSN, FN Jennifer Whitlock, RN, MSN, FNP-C, is a board-certified family nurse practitioner. She has experience in primary care and hospital medicine.

Young Children Do Not Receive Medical Gender Transition Treatment

By Kate Yandell

Posted on May 22, 2023

SciCheck Digest

Families seeking information from a health care provider about a young child’s gender identity may have their questions answered or receive counseling. Some posts share a misleading claim that toddlers are being “transitioned.” To be clear, prepubescent children are not offered transition surgery or drugs.

Some children identify with a gender that does not match their sex assigned at birth. These children are referred to as transgender, gender-diverse or gender-expansive. Doctors will listen to children and their family members, offer information, and in some cases connect them with mental health care, if needed.

But for children who have not yet started puberty, there are no recommended drugs, surgeries or other gender-transition treatments.

Recent social media posts shared the misleading claim that medical institutions in North Carolina are “transitioning toddlers,” which they called an “experimental treatment.” The posts referenced a blog post published by the Education First Alliance, a conservative nonprofit in North Carolina that says many schools are engaging in “ideological indoctrination” of children and need to be reformed.

The group has advocated the passage of a North Carolina bill to restrict medical gender-transition treatment before age 18. There are now 18 states that have taken action to restrict medical transition treatments for minors .

A widely shared article from the Epoch Times citing the blog post bore the false headline: “‘Transgender’ Toddlers as Young as 2 Undergoing Mutilation/Sterilization by NC Medical System, Journalist Alleges.” The Epoch Times has a history of publishing misleading or false claims. The article on transgender toddlers then disappeared from the website, and the Epoch Times published a new article clarifying that young children are not receiving hormone blockers, cross-sex hormones or surgery.

Representatives from all three North Carolina institutions referenced in the social media posts told us via emailed statements that they do not offer surgeries or other transition treatments to toddlers.

East Carolina University, May 5: ECU Health does not offer gender affirming surgery to minors nor does the health system offer gender affirming transition care to toddlers.

ECU Health elaborated that it does not offer puberty blockers and only offers hormone therapy after puberty “in limited cases,” as recommended in national guidelines and with parental or guardian consent. It also said that it offers interdisciplinary gender-affirming primary care for LGBTQ+ patients, including access to services such as mental health care, nutrition and social work.

“These primary care services are available to any LGBTQ+ patient who needs care. ECU Health does not provide gender-related care to patients 2 to 4 years old or any toddler period,” ECU said.

University of North Carolina, May 12: To be clear: UNC Health does not offer any gender-transitioning care for toddlers. We do not perform any gender care surgical procedures or medical interventions on toddlers. Also, we are not conducting any gender care research or clinical trials involving children. If a toddler’s parent(s) has concerns or questions about their child’s gender, a primary care provider would certainly listen to them, but would never recommend gender treatment for a toddler. Gender surgery can be performed on anyone 18 years old or older .

Duke Health, May 12: Duke Health has provided high-quality, compassionate, and evidence-based gender care to both adolescents and adults for many years. Care decisions are made by patients, families and their providers and are both age-appropriate and adherent to national and international guidelines. Under these professional guidelines and in accordance with accepted medical standards, hormone therapies are explicitly not provided to children prior to puberty and gender-affirming surgeries are, except in exceedingly rare circumstances, only performed after age 18.

Duke and UNC both called the claims that they offer gender-transition care to toddlers false, and ECU referred to the “intentional spreading of dangerous misinformation online.”

Nor do other medical institutions offer gender-affirming drug treatment or surgery to toddlers, clinical psychologist Christy Olezeski , director of the Yale Pediatric Gender Program, told us, although some may offer support to families of young children or connect them with mental health care.

The Education First Alliance post also states that a doctor “can see a 2-year-old girl play with a toy truck, and then begin treatment for gender dysphoria.” But simply playing with a certain toy would not meet the criteria for a diagnosis of gender dysphoria, according to the medical diagnostic manual used by health professionals.

“With all kids, we want them to feel comfortable and confident in who they are. We want them to feel comfortable and confident in how they like to express themselves. We want them to be safe,” Olezeski said. “So all of these tenets are taken into consideration when providing care for children. There is no medical care that happens prior to puberty.”

Medical Transition Starts During Adolescence or Later

The Education First Alliance blog post does not clearly state what it means when it says North Carolina institutions are “transitioning toddlers.” It refers to treatment and hormone therapy without clarifying the age at which it is offered.

Only in the final section of the piece does it include a quote from a doctor correctly stating that children are not offered surgery or drugs before puberty.

To spell out the reality of the situation: The North Carolina institutions are not providing surgeries or hormone therapy to prepubescent children, nor is this standard practice in any part of the country.

Programs and physicians will have different policies, but widely referenced guidance from the World Professional Association for Transgender Health and the Endocrine Society lays out recommended care at different ages.

Drugs that suppress puberty are the first medical treatment that may be offered to a transgender minor, the guidelines say. Children may be offered drugs to suppress puberty beginning when breast buds appear or testicles increase to a certain volume, typically happening between ages 8 to 13 or 9 to 14, respectively.

Generally, someone may start gender-affirming hormone therapy in early adolescence or later, the American Academy for Pediatrics explains . The Endocrine Society says that adolescents typically have the mental capacity to participate in making an informed decision about gender-affirming hormone therapy by age 16.

Older adolescents who want flat chests may sometimes be able to get surgery to remove their breasts, also known as top surgery, Olezeski said. They sometimes desire to do this before college. Guidelines do not offer a specific age during adolescence when this type of surgery may be appropriate. Instead, they explain how a care team can assess adolescents on a case-by-case basis.

A previous version of the WPATH guidelines did not recommend genital surgery until adulthood, but the most recent version, published in September 2022, is less specific about an age limit. Rather, it explains various criteria to determine whether someone who desires surgery should be offered it, including a person’s emotional and cognitive maturity level and whether they have been on hormone therapy for at least a year.

The Endocrine Society similarly offers criteria for when someone might be ready for genital surgery, but specifies that surgeries involving removing the testicles, ovaries or uterus should not happen before age 18.

“Typically any sort of genital-affirming surgeries still are happening at 18 or later,” Olezeski said.

There are no comprehensive statistics on the number of gender-affirming surgeries performed in the U.S., but according to an insurance claims analysis from Reuters and Komodo Health Inc., 776 minors with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria had breast removal surgeries and 56 had genital surgeries from 2019 to 2021.

Research Shows Benefits of Affirming Gender Identity

Young children do not get medical transition treatment, but they do have feelings about their gender and can benefit from support from those around them. “Children start to have a sense of their own gender identity between the ages of 2 1/2 to 3 years old,” Olezeski said.

Programs vary in what age groups they serve, she said, but some do support families of preschool-aged children by answering questions or providing mental health care.

Transgender children are at increased risk of some mental health problems, including anxiety and depression. According to the WPATH guidelines, affirming a child’s gender through day-to-day changes — also known as social transition — may have a positive impact on a child’s mental health. Social transition “may look different for every individual,” Olezeski said. Changes could include going by a different name or pronouns or altering one’s attire or hair style.

Two studies of socially transitioned children — including one with kids as young as 3 — have found minimal or no difference in anxiety and depression compared with non-transgender siblings or other children of similar ages.

“Research substantiates that children who are prepubertal and assert an identity of [transgender and gender diverse] know their gender as clearly and as consistently as their developmentally equivalent peers who identify as cisgender and benefit from the same level of social acceptance,” the AAP guidelines say, adding that differences in how children identify and express their gender are normal.

Social transitions largely take place outside of medical institutions, led by the child and supported by their family members and others around them. However, a family with questions about their child’s gender or social transition may be able to get information from their pediatrician or another medical provider, Olezeski said.

Although not available everywhere, specialized programs may be particularly prepared to offer care to a gender-diverse child and their family, she said. A child may get a referral to one of these programs from a pediatrician, another specialty physician, a mental health care professional or their school, or a parent may seek out one of these programs.

“We have created a space where parents can come with their youth when they’re young to ask questions about how to best support their child: what to do if they have questions, how to get support, what do we know about the best research in terms of how to allow kids space to explore their identity, to explore how they like to express themselves, and then if they do identify as trans or nonbinary, how to support the parents and the youth in that,” Olezeski said of specialized programs. Parents benefit from the support, and then the children also benefit from support from their parents.

WPATH says that the child should be the one to initiate a social transition by expressing a “strong desire or need” for it after consistently articulating an identity that does not match their sex assigned at birth. A health care provider can then help the family explore benefits and risks. A child simply playing with certain toys, dressing a certain way or enjoying certain activities is not a sign they would benefit from a social transition, the guidelines state.

Previously, assertions children made about their gender were seen as “possibly true” and support was often withheld until an age when identity was believed to become fixed, the AAP guidelines explain. But “more robust and current research suggests that, rather than focusing on who a child will become, valuing them for who they are, even at a young age, fosters secure attachment and resilience, not only for the child but also for the whole family,” the guidelines say.

Mental Health Care Benefits

A gender-diverse child or their family members may benefit from a referral to a psychologist or other mental health professional. However, being transgender or gender-diverse is not in itself a mental health disorder, according to the American Psychological Association , WPATH and other expert groups . These organizations also note that people who are transgender or gender-diverse do not all experience mental health problems or distress about their gender.

Psychological therapy is not meant to change a child’s gender identity, the WPATH guidelines say .

The form of therapy a child or a family might receive will depend on their particular needs, Olezeski said. For instance, a young child might receive play-based therapy, since play is how children “work out different things in their life,” she said. A parent might work on strategies to better support their child.

One mental health diagnosis that some gender-diverse people may receive is gender dysphoria . There is disagreement about how useful such a diagnosis is, and receiving such a diagnosis does not necessarily mean someone will decide to undergo a transition, whether social or medical.

UNC Health told us in an email that a gender dysphoria diagnosis “is rarely used” for children.

Very few gender-expansive kids have dysphoria, the spokesperson said. “ Gender expansion in childhood is not Gender Dysphoria ,” UNC added, attributing the explanation to psychiatric staff (emphasis is UNC’s). “The psychiatric team’s goal is to provide good mental health care and manage safety—this means trying to protect against abuse and bullying and to support families.”

Social media posts incorrectly claim that toddlers are being diagnosed with gender dysphoria based on what toys they play with. One post said : “Three medical schools in North Carolina are diagnosing TODDLERS who play with stereotypically opposite gender toys as having GENDER DYSPHORIA and are beginning to transition them!!”

There are separate criteria for diagnosing gender dysphoria in adults and adolescents versus children, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. For children to receive this diagnosis, they must meet six of eight criteria for a six-month period and experience “clinically significant distress” or impairment in functioning, according to the diagnostic manual.

A “strong preference for the toys, games or activities stereotypically used or engaged in by the other gender” is one criterion, but children must also meet other criteria, and expressing a strong desire to be another gender or insisting that they are another gender is required.

“People liking to play with different things or liking to wear a diverse set of clothes does not mean that somebody has gender dysphoria,” Olezeski said. “That just means that kids have a breadth of things that they can play with and ways that they can act and things that they can wear . ”

Editor’s note: SciCheck’s articles providing accurate health information and correcting health misinformation are made possible by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The foundation has no control over FactCheck.org’s editorial decisions, and the views expressed in our articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the foundation.

Rafferty, Jason. “ Gender-Diverse & Transgender Children .” HealthyChildren.org. Updated 8 Jun 2022.

Coleman, E. et al. “ Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8 .” International Journal of Transgender Health. 15 Sep 2022.

Rachmuth, Sloan. “ Transgender Toddlers Treated at Duke, UNC, and ECU .” Education First Alliance. 1 May 2023.

North Carolina General Assembly. “ Senate Bill 639, Youth Health Protection Act .” (as introduced 5 Apr 2023).

Putka, Sophie et al. “ These States Have Banned Youth Gender-Affirming Care .” Medpage Today. Updated 17 May 2023.

Davis, Elliott Jr. “ States That Have Restricted Gender-Affirming Care for Trans Youth in 2023 .” U.S. News & World Report. Updated 17 May 2023.

Montgomery, David and Goodman, J. David. “ Texas Legislature Bans Transgender Medical Care for Children .” New York Times. 17 May 2023.

Ji, Sayer. ‘ Transgender’ Toddlers as Young as 2 Undergoing Mutilation/Sterilization by NC Medical System, Journalist Alleges .” Epoch Times. Internet Archive, Wayback Machine. Archived 6 May 2023.

McDonald, Jessica. “ COVID-19 Vaccines Reduce, Not Increase, Risk of Stillbirth .” FactCheck.org. 9 Nov 2022.

Jaramillo, Catalina. “ Posts Distort Questionable Study on COVID-19 Vaccination and EMS Calls .” FactCheck.org. 15 June 2022.

Spencer, Saranac Hale. “ Social Media Posts Misrepresent FDA’s COVID-19 Vaccine Safety Research .” FactCheck.org. 23 Dec 2022.

Jaramillo, Catalina. “ WHO ‘Pandemic Treaty’ Draft Reaffirms Nations’ Sovereignty to Dictate Health Policy .” FactCheck.org. 2 Mar 2023.

McCormick Sanchez, Darlene. “ IN-DEPTH: North Carolina Medical Schools See Children as Young as Toddlers for Gender Dysphoria .” The Epoch Times. 8 May 2023.

ECU health spokesperson. Emails with FactCheck.org. 12 May 2023 and 19 May 2023.

UNC Health spokesperson. Emails with FactCheck.org. 12 May 2023 and 19 May 2023.

Duke Health spokesperson. Email with FactCheck.org. 12 May 2023.

Olezeski, Christy. Interview with FactCheck.org. 16 May 2023.

Hembree, Wylie C. et al. “ Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline .” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1 Nov 2017.

Emmanuel, Mickey and Bokor, Brooke R. “ Tanner Stages .” StatPearls. Updated 11 Dec 2022.

Rafferty, Jason et al. “ Ensuring Comprehensive Care and Support for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Children and Adolescents .” Pediatrics. 17 Sep 2018.

Coleman, E. et al. “ Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender-Nonconforming People, Version 7 .” International Journal of Transgenderism. 27 Aug 2012.

Durwood, Lily et al. “ Mental Health and Self-Worth in Socially Transitioned Transgender Youth .” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 27 Nov 2016.

Olson, Kristina R. et al. “ Mental Health of Transgender Children Who Are Supported in Their Identities .” Pediatrics. 26 Feb 2016.

“ Answers to Your Questions about Transgender People, Gender Identity, and Gender Expression .” American Psychological Association website. 9 Mar 2023.

“ What is Gender Dysphoria ?” American Psychiatric Association website. Updated Aug 2022.

Vanessa Marie | Truth Seeker (indivisible.mama). “ Three medical schools in North Carolina are diagnosing TODDLERS who play with stereotypically opposite gender toys as having GENDER DYSPHORIA and are beginning to transition them!! … ” Instagram. 7 May 2023.

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Error bars represent 95% CIs. GAS indicates gender-affirming surgery.

Percentages are based on the number of procedures divided by number of patients; thus, as some patients underwent multiple procedures the total may be greater than 100%. Error bars represent 95% CIs.

eTable. ICD-10 and CPT Codes of Gender-Affirming Surgery

eFigure. Percentage of Patients With Codes for Gender Identity Disorder Who Underwent GAS

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Wright JD , Chen L , Suzuki Y , Matsuo K , Hershman DL. National Estimates of Gender-Affirming Surgery in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(8):e2330348. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

National Estimates of Gender-Affirming Surgery in the US

- 1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, New York

- 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Southern California, Los Angeles

Question What are the temporal trends in gender-affirming surgery (GAS) in the US?

Findings In this cohort study of 48 019 patients, GAS increased significantly, nearly tripling from 2016 to 2019. Breast and chest surgery was the most common class of procedures performed overall; genital reconstructive procedures were more common among older individuals.

Meaning These findings suggest that there will be a greater need for clinicians knowledgeable in the care of transgender individuals with the requisite expertise to perform gender-affirming procedures.

Importance While changes in federal and state laws mandating coverage of gender-affirming surgery (GAS) may have led to an increase in the number of annual cases, comprehensive data describing trends in both inpatient and outpatient procedures are limited.

Objective To examine trends in inpatient and outpatient GAS procedures in the US and to explore the temporal trends in the types of GAS performed across age groups.

Design, Setting, and Participants This cohort study includes data from 2016 to 2020 in the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample and the National Inpatient Sample. Patients with diagnosis codes for gender identity disorder, transsexualism, or a personal history of sex reassignment were identified, and the performance of GAS, including breast and chest procedures, genital reconstructive procedures, and other facial and cosmetic surgical procedures, were identified.

Main Outcome Measures Weighted estimates of the annual number of inpatient and outpatient procedures performed and the distribution of each class of procedure overall and by age were analyzed.

Results A total of 48 019 patients who underwent GAS were identified, including 25 099 (52.3%) who were aged 19 to 30 years. The most common procedures were breast and chest procedures, which occurred in 27 187 patients (56.6%), followed by genital reconstruction (16 872 [35.1%]) and other facial and cosmetic procedures (6669 [13.9%]). The absolute number of GAS procedures rose from 4552 in 2016 to a peak of 13 011 in 2019 and then declined slightly to 12 818 in 2020. Overall, 25 099 patients (52.3%) were aged 19 to 30 years, 10 476 (21.8%) were aged 31 to 40, and 3678 (7.7%) were aged12 to 18 years. When stratified by the type of procedure performed, breast and chest procedures made up a greater percentage of the surgical interventions in younger patients, while genital surgical procedures were greater in older patients.

Conclusions and Relevance Performance of GAS has increased substantially in the US. Breast and chest surgery was the most common group of procedures performed. The number of genital surgical procedures performed increased with increasing age.

Gender dysphoria is characterized as an incongruence between an individual’s experienced or expressed gender and the gender that was assigned at birth. 1 Transgender individuals may pursue multiple treatments, including behavioral therapy, hormonal therapy, and gender-affirming surgery (GAS). 2 GAS encompasses a variety of procedures that align an individual patient’s gender identity with their physical appearance. 2 - 4

While numerous surgical interventions can be considered GAS, the procedures have been broadly classified as breast and chest surgical procedures, facial and cosmetic interventions, and genital reconstructive surgery. 2 , 4 Prior studies 2 - 7 have shown that GAS is associated with improved quality of life, high rates of satisfaction, and a reduction in gender dysphoria. Furthermore, some studies have reported that GAS is associated with decreased depression and anxiety. 8 Lastly, the procedures appear to be associated with acceptable morbidity and reasonable rates of perioperative complications. 2 , 4

Given the benefits of GAS, the performance of GAS in the US has increased over time. 9 The increase in GAS is likely due in part to federal and state laws requiring coverage of transition-related care, although actual insurance coverage of specific procedures is variable. 10 , 11 While prior work has shown that the use of inpatient GAS has increased, national estimates of inpatient and outpatient GAS are lacking. 9 This is important as many GAS procedures occur in ambulatory settings. We performed a population-based analysis to examine trends in GAS in the US and explored the temporal trends in the types of GAS performed across age groups.

To capture both inpatient and outpatient surgical procedures, we used data from the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample (NASS) and the National Inpatient Sample (NIS). NASS is an ambulatory surgery database and captures major ambulatory surgical procedures at nearly 2800 hospital-owned facilities from up to 35 states, approximating a 63% to 67% stratified sample of hospital-owned facilities. NIS comprehensively captures approximately 20% of inpatient hospital encounters from all community hospitals across 48 states participating in the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP), covering more than 97% of the US population. Both NIS and NASS contain weights that can be used to produce US population estimates. 12 , 13 Informed consent was waived because data sources contain deidentified data, and the study was deemed exempt by the Columbia University institutional review board. This cohort study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline.

We selected patients of all ages with an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision ( ICD-10 ) diagnosis codes for gender identity disorder or transsexualism ( ICD-10 F64) or a personal history of sex reassignment ( ICD-10 Z87.890) from 2016 to 2020 (eTable in Supplement 1 ). We first examined all hospital (NIS) and ambulatory surgical (NASS) encounters for patients with these codes and then analyzed encounters for GAS within this cohort. GAS was identified using ICD-10 procedure codes and Common Procedural Terminology codes and classified as breast and chest procedures, genital reconstructive procedures, and other facial and cosmetic surgical procedures. 2 , 4 Breast and chest surgical procedures encompassed breast reconstruction, mammoplasty and mastopexy, or nipple reconstruction. Genital reconstructive procedures included any surgical intervention of the male or female genital tract. Other facial and cosmetic procedures included cosmetic facial procedures and other cosmetic procedures including hair removal or transplantation, liposuction, and collagen injections (eTable in Supplement 1 ). Patients might have undergone procedures from multiple different surgical groups. We measured the total number of procedures and the distribution of procedures within each procedural group.

Within the data sets, sex was based on patient self-report. The sex of patients in NIS who underwent inpatient surgery was classified as either male, female, missing, or inconsistent. The inconsistent classification denoted patients who underwent a procedure that was not consistent with the sex recorded on their medical record. Similar to prior analyses, patients in NIS with a sex variable not compatible with the procedure performed were classified as having undergone genital reconstructive surgery (GAS not otherwise specified). 9

Clinical variables in the analysis included patient clinical and demographic factors and hospital characteristics. Demographic characteristics included age at the time of surgery (12 to 18 years, 19 to 30 years, 31 to 40 years, 41 to 50 years, 51 to 60 years, 61 to 70 years, and older than 70 years), year of the procedure (2016-2020), and primary insurance coverage (private, Medicare, Medicaid, self-pay, and other). Race and ethnicity were only reported in NIS and were classified as White, Black, Hispanic and other. Race and ethnicity were considered in this study because prior studies have shown an association between race and GAS. The income status captured national quartiles of median household income based of a patient’s zip code and was recorded as less than 25% (low), 26% to 50% (medium-low), 51% to 75% (medium-high), and 76% or more (high). The Elixhauser Comorbidity Index was estimated for each patient based on the codes for common medical comorbidities and weighted for a final score. 14 Patients were classified as 0, 1, 2, or 3 or more. We separately reported coding for HIV and AIDS; substance abuse, including alcohol and drug abuse; and recorded mental health diagnoses, including depression and psychoses. Hospital characteristics included a composite of teaching status and location (rural, urban teaching, and urban nonteaching) and hospital region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). Hospital bed sizes were classified as small, medium, and large. The cutoffs were less than 100 (small), 100 to 299 (medium), and 300 or more (large) short-term acute care beds of the facilities from NASS and were varied based on region, urban-rural designation, and teaching status of the hospital from NIS. 8 Patients with missing data were classified as the unknown group and were included in the analysis.

National estimates of the number of GAS procedures among all hospital encounters for patients with gender identity disorder were derived using discharge or encounter weight provided by the databases. 15 The clinical and demographic characteristics of the patients undergoing GAS were reported descriptively. The number of encounters for gender identity disorder, the percentage of GAS procedures among those encounters, and the absolute number of each procedure performed over time were estimated. The difference by age group was examined and tested using Rao-Scott χ 2 test. All hypothesis tests were 2-sided, and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

A total of 48 019 patients who underwent GAS were identified ( Table 1 ). Overall, 25 099 patients (52.3%) were aged 19 to 30 years, 10 476 (21.8%) were aged 31 to 40, and 3678 (7.7%) were aged 12 to 18 years. Private insurance coverage was most common in 29 064 patients (60.5%), while 12 127 (25.3%) were Medicaid recipients. Depression was reported in 7192 patients (15.0%). Most patients (42 467 [88.4%]) were treated at urban, teaching hospitals, and there was a disproportionate number of patients in the West (22 037 [45.9%]) and Northeast (12 396 [25.8%]). Within the cohort, 31 668 patients (65.9%) underwent 1 procedure while 13 415 (27.9%) underwent 2 procedures, and the remainder underwent multiple procedures concurrently ( Table 1 ).

The overall number of health system encounters for gender identity disorder rose from 13 855 in 2016 to 38 470 in 2020. Among encounters with a billing code for gender identity disorder, there was a consistent rise in the percentage that were for GAS from 4552 (32.9%) in 2016 to 13 011 (37.1%) in 2019, followed by a decline to 12 818 (33.3%) in 2020 ( Figure 1 and eFigure in Supplement 1 ). Among patients undergoing ambulatory surgical procedures, 37 394 (80.3%) of the surgical procedures included gender-affirming surgical procedures. For those with hospital admissions with gender identity disorder, 10 625 (11.8%) of admissions were for GAS.

Breast and chest procedures were most common and were performed for 27 187 patients (56.6%). Genital reconstruction was performed for 16 872 patients (35.1%), and other facial and cosmetic procedures for 6669 patients (13.9%) ( Table 2 ). The most common individual procedure was breast reconstruction in 21 244 (44.2%), while the most common genital reconstructive procedure was hysterectomy (4489 [9.3%]), followed by orchiectomy (3425 [7.1%]), and vaginoplasty (3381 [7.0%]). Among patients who underwent other facial and cosmetic procedures, liposuction (2945 [6.1%]) was most common, followed by rhinoplasty (2446 [5.1%]) and facial feminizing surgery and chin augmentation (1874 [3.9%]).

The absolute number of GAS procedures rose from 4552 in 2016 to a peak of 13 011 in 2019 and then declined slightly to 12 818 in 2020 ( Figure 1 ). Similar trends were noted for breast and chest surgical procedures as well as genital surgery, while the rate of other facial and cosmetic procedures increased consistently from 2016 to 2020. The distribution of the individual procedures performed in each class were largely similar across the years of analysis ( Table 3 ).

When stratified by age, patients 19 to 30 years had the greatest number of procedures, 25 099 ( Figure 2 ). There were 10 476 procedures performed in those aged 31 to 40 years and 4359 in those aged 41 to 50 years. Among patients younger than 19 years, 3678 GAS procedures were performed. GAS was less common in those cohorts older than 50 years. Overall, the greatest number of breast and chest surgical procedures, genital surgical procedures, and facial and other cosmetic surgical procedures were performed in patients aged 19 to 30 years.

When stratified by the type of procedure performed, breast and chest procedures made up the greatest percentage of the surgical interventions in younger patients while genital surgical procedures were greater in older patients ( Figure 2 ). Additionally, 3215 patients (87.4%) aged 12 to 18 years underwent GAS and had breast or chest procedures. This decreased to 16 067 patients (64.0%) in those aged 19 to 30 years, 4918 (46.9%) in those aged 31 to 40 years, and 1650 (37.9%) in patients aged 41 to 50 years ( P < .001). In contrast, 405 patients (11.0%) aged 12 to 18 years underwent genital surgery. The percentage of patients who underwent genital surgery rose sequentially to 4423 (42.2%) in those aged 31 to 40 years, 1546 (52.3%) in those aged 51 to 60 years, and 742 (58.4%) in those aged 61 to 70 years ( P < .001). The percentage of patients who underwent facial and other cosmetic surgical procedures rose with age from 9.5% in those aged 12 to 18 years to 20.6% in those aged 51 to 60 years, then gradually declined ( P < .001). Figure 2 displays the absolute number of procedure classes performed by year stratified by age. The greatest magnitude of the decline in 2020 was in younger patients and for breast and chest procedures.

These findings suggest that the number of GAS procedures performed in the US has increased dramatically, nearly tripling from 2016 to 2019. Breast and chest surgery is the most common class of procedure performed while patients are most likely to undergo surgery between the ages of 19 and 30 years. The number of genital surgical procedures performed increased with increasing age.

Consistent with prior studies, we identified a remarkable increase in the number of GAS procedures performed over time. 9 , 16 A prior study examining national estimates of inpatient GAS procedures noted that the absolute number of procedures performed nearly doubled between 2000 to 2005 and from 2006 to 2011. In our analysis, the number of GAS procedures nearly tripled from 2016 to 2020. 9 , 17 Not unexpectedly, a large number of the procedures we captured were performed in the ambulatory setting, highlighting the need to capture both inpatient and outpatient procedures when analyzing data on trends. Like many prior studies, we noted a decrease in the number of procedures performed in 2020, likely reflective of the COVID-19 pandemic. 18 However, the decline in the number of procedures performed between 2019 and 2020 was relatively modest, particularly as these procedures are largely elective.

Analysis of procedure-specific trends by age revealed a number of important findings. First, GAS procedures were most common in patients aged 19 to 30 years. This is in line with prior work that demonstrated that most patients first experience gender dysphoria at a young age, with approximately three-quarters of patients reporting gender dysphoria by age 7 years. These patients subsequently lived for a mean of 23 years for transgender men and 27 years for transgender women before beginning gender transition treatments. 19 Our findings were also notable that GAS procedures were relatively uncommon in patients aged 18 years or younger. In our cohort, fewer than 1200 patients in this age group underwent GAS, even in the highest volume years. GAS in adolescents has been the focus of intense debate and led to legislative initiatives to limit access to these procedures in adolescents in several states. 20 , 21

Second, there was a marked difference in the distribution of procedures in the different age groups. Breast and chest procedures were more common in younger patients, while genital surgery was more frequent in older individuals. In our cohort of individuals aged 19 to 30 years, breast and chest procedures were twice as common as genital procedures. Genital surgery gradually increased with advancing age, and these procedures became the most common in patients older than 40 years. A prior study of patients with commercial insurance who underwent GAS noted that the mean age for mastectomy was 28 years, significantly lower than for hysterectomy at age 31 years, vaginoplasty at age 40 years, and orchiectomy at age 37 years. 16 These trends likely reflect the increased complexity of genital surgery compared with breast and chest surgery as well as the definitive nature of removal of the reproductive organs.

This study has limitations. First, there may be under-capture of both transgender individuals and GAS procedures. In both data sets analyzed, gender is based on self-report. NIS specifically makes notation of procedures that are considered inconsistent with a patient’s reported gender (eg, a male patient who underwent oophorectomy). Similar to prior work, we assumed that patients with a code for gender identity disorder or transsexualism along with a surgical procedure classified as inconsistent underwent GAS. 9 Second, we captured procedures commonly reported as GAS procedures; however, it is possible that some of these procedures were performed for other underlying indications or diseases rather than solely for gender affirmation. Third, our trends showed a significant increase in procedures through 2019, with a decline in 2020. The decline in services in 2020 is likely related to COVID-19 service alterations. Additionally, while we comprehensively captured inpatient and ambulatory surgical procedures in large, nationwide data sets, undoubtedly, a small number of procedures were performed in other settings; thus, our estimates may underrepresent the actual number of procedures performed each year in the US.

These data have important implications in providing an understanding of the use of services that can help inform care for transgender populations. The rapid rise in the performance of GAS suggests that there will be a greater need for clinicians knowledgeable in the care of transgender individuals and with the requisite expertise to perform GAS procedures. However, numerous reports have described the political considerations and challenges in the delivery of transgender care. 22 Despite many medical societies recognizing the necessity of gender-affirming care, several states have enacted legislation or policies that restrict gender-affirming care and services, particularly in adolescence. 20 , 21 These regulations are barriers for patients who seek gender-affirming care and provide legal and ethical challenges for clinicians. As the use of GAS increases, delivering equitable gender-affirming care in this complex landscape will remain a public health challenge.

Accepted for Publication: July 15, 2023.

Published: August 23, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2023 Wright JD et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Jason D. Wright, MD, Division of Gynecologic Oncology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, 161 Fort Washington Ave, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10032 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Dr Wright had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Wright, Chen.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Wright.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Wright, Chen.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Wright, Suzuki.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Wright reported receiving grants from Merck and personal fees from UpToDate outside the submitted work. No other disclosures were reported.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2 .

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

- New Hampshire

- North Carolina

- Pennsylvania

- West Virginia

- Online hoaxes

- Coronavirus

- Health Care

- Immigration

- Environment

- Foreign Policy

- Kamala Harris

- Donald Trump

- Mitch McConnell

- Hakeem Jeffries

- Ron DeSantis

- Tucker Carlson

- Sean Hannity

- Rachel Maddow

- PolitiFact Videos

- 2024 Elections

- Mostly True

- Mostly False

- Pants on Fire

- Biden Promise Tracker

- Trump-O-Meter

- Latest Promises

- Our Process

- Who pays for PolitiFact?

- Advertise with Us

- Suggest a Fact-check

- Corrections and Updates

- Newsletters

Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy. We need your help.

I would like to contribute

- Facebook Fact-checks

- Viral image

No, young children cannot take hormones or change their sex

If your time is short.

• Professional medical organizations recommend against puberty blockers for children who have not reached puberty, which typically begins between ages 10 and 12.

• Hormone treatment for feminization or masculinization of the body is typically not considered until patients are at least 16 years old.

• Gender reassignment surgery is typically only available to those 18 and older in the United States.

Misinformation about medical treatments for transgender patients has proliferated in recent weeks, as a spate of events brought transgender rights into the spotlight.

The social media backlash was swift following executive actions from President Joe Biden to expand transgender rights, his nomination of a transgender woman for assistant health secretary and the U.S. House of Representatives’ passing of the Equality Act to prohibit discrimation based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

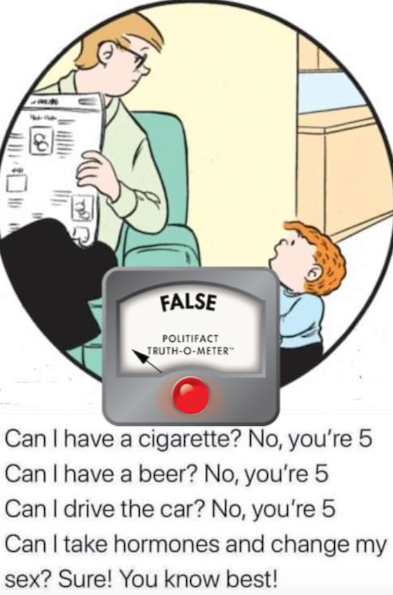

One Facebook post features an image of a father and son from the comic strip "The Family Circus," with text that reads, "Can I have a cigarette? No, you’re 5. Can I have a beer? No, you’re 5. Can I drive the car? No, you’re 5. Can I take hormones and change my sex? Sure! You know best."

The onset of puberty is the baseline for medical intervention. Puberty typically occurs between ages 10 and 14 for girls and 12 and 16 for boys.

Guidelines for the medical care of transgender patients, developed by organizations such as the Endocrine Society and the World Professional Association for Transgender Health, begin with counseling and psychological evaluation by a team of medical professionals before any physical interventions are considered.