- Health & Wellness

- Hearing Disorders

- Patient Care

- Amplification

- Hearing Aids

- Implants & Bone Conduction

- Tinnitus Devices

- Vestibular Solutions

- Accessories

- Office Services

- Practice Management

- Industry News

- Organizations

- White Papers

- Edition Archive

Select Page

Case Study of a 5-Year-Old Boy with Unilateral Hearing Loss

Jan 15, 2015 | Pediatric Care | 0 |

Case Study | Pediatrics | January 2015 Hearing Review

A reminder of what our tests really say about the auditory system..

By Michael Zagarella, AuD

How many times have I heard— and said myself—that the OAE is not a hearing test? How many times have I thought to myself that, just because a child passes their newborn hearing screening test, it does not mean they have normal hearing? This case brought those two statements front and center.

A 5-year-old boy was referred to me for a hearing test because he did not pass a kindergarten screening test in his right ear. His parents reported that he said “Huh?” frequently, and more recently they noticed him turning his head when spoken to. He had passed his newborn hearing screening, and he had experienced a few ear infections that responded well to antibiotics. The parents mentioned a maternal aunt who is “nearly totally deaf” and wears binaural hearing aids.

Initial Test Results

Otoscopic examination showed a clear ear canal and a normal-appearing tympanic membrane on the right side. The left ear canal contained non-occluding wax.

Tympanograms were within normal limits bilaterally. Unfortunately, otoacoustic emissions (OAE) testing could not be completed because of an equipment malfunction.

Behavioral testing with SRTs was taken, and I typically start with the right ear. The child seemed bright and cooperative enough for routine testing. I obtained no response until 80 dB.

I switched to the left ear and he responded appropriately. This prompted me to walk into the test booth and check the equipment and wires; everything was plugged in and looked normal. I tried SRTs again with the same results, even reversing the earphones. Same results. When the behavioral tests were completed, the results indicated normal hearing in his left ear and a profound hearing loss in his right ear.

The child’s parents were informed of these results, and we scheduled him to return for a retest in order to confirm these findings.

Follow-up Test

One week later, the boy returned for a follow-up test. The otoscopic exam was the same: RE = normal; LE = non-occluding wax.

Tympanograms were within normal limits. I added acoustic reflexes, which were normal in his left ear (80-90 dB), and questionable in his right ear (105-115 dB).

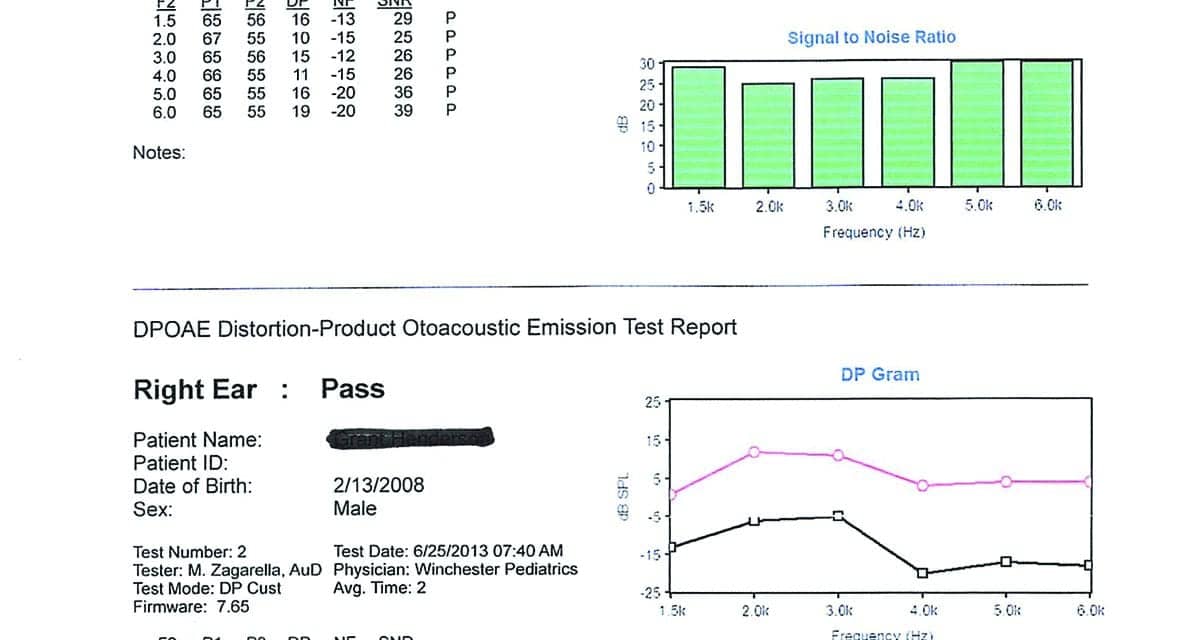

DPOAEs were present in both ears. The right ear was reduced in amplitude compared with the left, but not what I would expect to see with a profound hearing loss (Figure 1).

I repeated the behavioral tests with the same results that I obtained the first time (Figure 2). Bone conduction scores were not obtained at this time because I felt I was reaching the limits of a 5-year-old, and the tympanograms were normal on two occasions.

Recommendation to Parents

After completing the tests, I explained auditory dyssynchrony to the parents, and told them that this is what their son appeared to have. Since they were people with resources, I advised them to make an appointment at Johns Hopkins to have this diagnosis confirmed by ABR.

Johns Hopkins Results

The initial appointment at Johns Hopkins was at the ENT clinic. According to the report from the parents, the physician reviewed my test results and said it was unlikely that they were valid. She suggested they repeat the entire test battery before proceeding with an ABR. All peripheral tests were repeated with exactly the same results that I had obtained. The ABR was scheduled and performed, yielding:

“Findings are consistent with normal hearing sensitivity in the left ear and a neural hearing loss in the right ear consistent with auditory dyssynchrony (auditory neuropathy). The normal hearing in the left ear is adequate for speech and language development at this time.”

Additional Follow-up

The boy’s mother was not completely satisfied with the diagnosis or explanation. After she arrived home and mulled things over, she called Johns Hopkins and asked if they could do an MRI. The ENT assured her that it probably would not show anything, but if it would allay her concerns (and since they had good insurance coverage), they would schedule the MRI.

Further reading: Vestibular Assessment in Infant Cochlear Implant Candidates

Figure 1. DPOAEs of 5-year-old boy.

Findings of MRI. Evaluation of the right inner ear structures demonstrated absence of the right cochlear nerve. The vestibular nerve is present but is small in caliber. The internal auditory canal is somewhat small in diameter. There is atresia versus severe stenosis of the cochlear nerve canal. The right modiolus is thickened. The cochlea has the normal amount of turns, and the vestibule semicircular canals appear normal.

The left inner ear structures, cranial nerves VII and VIII complex, and internal auditory canal are normal. Additional normal findings were also presented regarding sinuses, etc.

Key finding: The results were consistent with atresia versus severe stenosis of the right cochlear nerve canal and cochlear nerve and deficiency described above.

The Value of Relearning in Everyday Clinical Practice

Figure 2. Follow-up behavioral test of 5-year-old boy.

According to the MRI, the cochlea on the right side is normal—which would explain the present DPOAE results. The cochlear branch of the VIIIth Cranial Nerve is completely absent, which would explain the absent ABR result and the profound hearing loss by behavioral testing.

This case has certainly caused me to re-evaluate what I think and say about my test findings. How many times have I heard—and said myself!—that the OAE is not a hearing test? How many times have I thought to myself that, just because a child passes their newborn hear- ing screening test, it does not mean that they have normal hearing?

This case has surely brought those two statements front and center. In addition, what about auditory neuropathy? In about 40 years of testing, I had never seen a case that I was convinced was AN. Naturally, I was somewhat skeptical about this disorder: Is it real, or does it reside in the realm of the Yeti. (Personal note to Dr Chuck Berlin: I truly don’t doubt you, but I do like to see things for myself!)

Finally, this case only reinforces my trust in “mother’s intuition” and the value of deferring to the sensible requests of parents. If she had not felt uneasy about what she had been told at one of the most prestigious clinics in the country, the actual source of this problem would not have been discovered.

So what? Does any of this really make a difference? The bottom line is we have a 5-year-old boy with a unilateral profound hearing loss. How important is it that we know why he has that loss? From a purely clinical standpoint, I think that it is poignant because it brings home the importance of understanding what our tests really say about the hearing mechanism and auditory system (ie, is working or not working?).

And although it may not make a large difference in the boy’s current treatment plan, I do know that the boy’s mother is grateful for understanding the reason for her son’s hearing loss and that it’s at least possible the boy may benefit from this knowledge in the future.

Michael Zagarella, AuD, is an audiologist at RESA 8 Audiology Clinic in Martinsburg, WVa.

Correspondence can be addressed to HR or or Dr Zagarella at: [email protected]

Citation for this article: Zagarella M. Case study of a 5-year-old boy with unilateral hearing loss. Hearing Review . 2015;22(1):30-33.

Related Posts

March 13, 2014

Harnessing Technology and Patient Care for Pediatric Hearing Aid Fittings

February 20, 2024

Teen Publishes Research on Harmful Noise Levels from Restroom Hand Dryers

July 1, 2019

Routine Hearing Test May Help Diagnose Autism Earlier

February 28, 2023

Recent Posts

- Masking for Audiometry: Robert Turner’s Optimized Method

- Neosensory’s Wristband Tech Improves Speech Understanding for Hearing Loss Patients

- Duncan Floyd on Masking—The Optimized Method

- AAA 2024: Building a Better Future for Hearing Care

- Sycle to Help Hearing Clinic Offices Go Paperless

- New GN Initiative to Raise Awareness of Link Between Hearing and Cognitive Health

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Learning from the Longitudinal Outcomes of Children with Hearing Impairment (LOCHI) study: summary of 5-year findings and implications

Teresa yc ching.

1 National Acoustic Laboratories, Sydney, Australia

2 The HEARing CRC, Melbourne, Australia

Harvey Dillon

3 Department of Linguistics and Centre for Cognition and its Disorders, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

4 Renwick Centre, Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children

Linda Cupples

This article summarises findings of the Longitudinal Outcomes of Children with Hearing Impairment (LOCHI) study, and discusses implications of the findings for research and clinical practice.

A population-based study on outcomes of children with hearing loss. Evaluations were conducted at five years of age.

Study sample

Participants were 470 children born with hearing loss between 2002 and 2007 in New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland in Australia, and who first received amplification or cochlear implantation by three years of age.

The earlier hearing aids or cochlear implants were fitted, the better the speech, language and functional performance outcomes. Better speech perception was also associated with better language and higher cognitive abilities. Better psychosocial development was associated with better language and functional performance. Higher maternal education level was also associated with better outcomes. Qualitative analyses of parental perspectives revealed the multiple facets of their involvement in intervention.

Conclusions

The LOCHI study has shown that early fitting of hearing devices is key to achieving better speech, language and functional performance outcomes for children with hearing loss. The findings are discussed in relation to changes in clinical practice and directions for future research.

Introduction

The Longitudinal Outcomes of Children with Hearing Impairment (LOCHI) study is a prospective, quasi-experimental investigation of the effects of age at intervention and other factors on outcomes of children with permanent childhood hearing loss (PCHL) ( Ching et al., 2013d ). The study increases understanding about the impact of PCHL on developmental outcomes in a population-based sample, and generates evidence that guides improved management of PCHL to optimise child outcomes.

The research team enrolled about 470 children born with hearing loss between 2002 and 2007 in New South Wales, Victoria, and Queensland, and who first received hearing aids or cochlear implants younger than three years of age. Some children had access to universal newborn hearing screening (UNHS) whereas others not, depending on whether UNHS was operating in their region of birth. The study controlled for variations in post-diagnostic audiological management, with all children receiving the same consistent post-diagnostic services from Australian Hearing (AH), the government-funded organization that provides hearing services to children with hearing loss in Australia.

Evaluations of the outcomes of the cohort in the study were carried out at several time points. Findings on the outcomes at three years of age have been reported previously ( Ching & Dillon, 2013 ; Ching et al., 2013c ). In the collection of articles in this Supplement, detailed reports on the perspectives of parents about diagnosis and intervention have been provided, comprehensive descriptions about the characteristics of hearing aids and cochlear implants worn by children have been included, and investigations of factors influencing a range of outcomes, including language, functional performance, speech perception, and psychosocial skills, have been reported in detail. This paper summarises results across the various outcomes domains and considers the practical implications of these findings for management of children with PCHL.

Summary of findings

Parents’ perspectives about diagnosis and intervention.

About 85% of parents/caregivers who completed a questionnaire survey reported that they were satisfied with the information and emotional support provided to them after diagnosis of their children’s hearing loss ( Scarinci et al., this issue ). However, a few families indicated that they experienced a breakdown in information transfer with health professionals, and reflected on the post-diagnostic period as a difficult and emotional time. They described the process of accessing intervention services for their child as navigating a maze.

Parental involvement in early intervention was further explored through semi-structured interviews ( Erbasi et al., this issue ). Parents perceived themselves as central to the intervention of their children and held themselves responsible for their children’s outcomes. They served multiple roles including those of a case manager in organising multiple appointments and attending them with the child while making arrangements for the family, a care-provider in making sure that the child is well prepared before attending appointments, a teacher, and an advocate for the child’s needs. Parents noted that they always have the best interest of the child’s language development in mind in their daily lives, and amidst the multi-tasking, they are parents. They considered that the multi-faceted nature of their involvement in their children’s intervention has not always been recognised by professionals. These findings suggest that it is important for service providers to acknowledge the many roles that parents play and provide them with support to fulfil those roles. It is also important for service providers to not reduce the parent-child relationship into a pedagogical relationship ( Suissa, 2006 ). Given that parents held themselves accountable for their child’s outcomes and experienced a sense of failure when the child did not appear to progress, it would be useful to offer counselling services to reduce the risk of parents experiencing guilt or other negative emotions. The findings are consistent with, and lend support to, the recommendations outlined in the international consensus statement on family centred early intervention ( Moeller et al., 2013 ).

Audiological intervention: HA fitting

Children in the LOCHI study appeared to have benefited from the presence of a national government-funded organisation that provides consistent audiological management and technology to all children with PCHL. The study showed that:

- - Device fitting occurred shortly after diagnosis, regardless of whether the hearing loss was diagnosed via UNHS or standard care, or the geographical state of residence. Comparison of the medians of the time gap between diagnosis and first fitting for participants in the LOCHI study showed no significant difference between screened and non-screened groups. The median ages at fitting of hearing aids (HAs) were 3.5 months (interquartile range: 2.3–7.3) and 16.4 months (interquartile range: 7.2–25.8) for the respective groups.

- - Measurements of HAs used by children in the LOCHI study revealed that prescriptive targets were met within 3 dB root-mean-square (rms) error across the range from 0.5 to 4 kHz; both when measured at three years of age ( Ching et al., 2013b ) and at five years of age ( Ching et al., this issue ). A close proximity to targets was achieved, regardless of whether the National Acoustic Laboratories (NAL) or the Desired Sensation Level procedure (DSL) prescription was used for HA fitting.

- - The randomised trial of NAL and DSL prescriptions revealed no significant differences between prescription groups in language, speech production and speech perception scores at five years of age ( Ching et al., this issue ). When HAs matched targets of the respective prescriptive procedures that are supported by good empirical evidence, they enable the same speech intelligibility and language development. The findings lend support to the American Academy of Audiology guidelines for best practice in pediatric amplification ( American Academy of Audiology Task Force on Pediatric Amplification, 2013 ).

Audiological intervention: CI characteristics

All children who wear cochlear implants (CIs) use the Cochlear Nucleus devices. They received programming services from different CI service centres across the three states, while continuing to receive hearing-related services from AH including but not limited to remote microphone systems, upgrades of CI processors, and accessories. We found that:

- - Clinical practice is consistent across sites, with most CIs being programmed according to default values recommended by the manufacturer. The proportion of non-default settings in pulse width, stimulation rate, number of active electrodes and number of maxima was higher in children with auditory nerve deficiency or cochlear lesions, compared to children without those conditions ( Incerti et al., this issue ).

- - Children with cochlear structural and/or neural lesions required significantly higher current levels for threshold and comfortable levels (T- and C-levels), as compared to children without those conditions. Hence, approaches for programming CIs for children with cochlear structural and/or neural lesions need to be less reliant on interpolation of levels or global adjustment techniques than those for children without those conditions.

- - Averaged across all children, C-levels at six months after activation of their CIs were significantly lower than those at three and five years.

- - Averaged across all children, there were no significant differences between three and five years of age in T-levels, C-levels, and dynamic range in CIs worn by children.

- - Comparing the CI settings in children who first received their CIs by 12 months of age (early-implanted) to those who received their CIs between 12 months and three years (later-implanted), we found that T-levels were significantly higher and dynamic ranges were significantly narrower for the early-implanted group. These findings, discussed in detail in Incerti et al (this issue) , call for new programming tools to improve clinical practice so that children who receive CIs earlier gain access to a wider range of sounds earlier to capture the benefits of early implantation.

Factors influencing outcomes: early fitting of HA or CI is key

Children’s language, functional performance, speech perception, and psychosocial skills were measured at five years of age. The findings show that the earlier the intervention commenced, the better were the outcomes. This result applies over the entire range of intervention ages measured, which is 0.9 to 35.8 months for children wearing HAs and 5.3 to 35.3 months for children wearing CIs. The benefit of early fitting is greater for those with poorer hearing ( Ching et al., 2017a ).

- - Earlier device fitting (HA or CI) was associated with higher global language scores (summarising language ability, speech production and speech perception evaluated using a range of measures). For those with HAs, the impact of later fitting increased with the degree of hearing loss ( Ching et al., 2017a ).

- - Earlier device fitting (HA or CI) was associated with better receptive and expressive language.

- - Higher nonverbal cognitive ability was associated with better receptive and expressive language, speech production, and functional performance in everyday life ( Cupples et al., this issue-b ).

- - For children wearing HAs, less severe hearing loss and higher levels of maternal education were also significantly associated with better language outcomes ( Cupples et al., this issue-b ).

- - The absence of additional disabilities was significantly associated with better language outcomes for children using CIs, but not for those using HAs ( Cupples et al., this issue-a ).

- - A randomised controlled trial of the NAL and DSL prescriptions showed that there were no significant between-group differences in language or speech perception outcomes ( Ching et al., this issue ).

- - For children with additional disabilities, better language outcomes were associated with earlier fitting of HAs, lesser hearing loss, higher cognitive ability, use of speech for communication, and higher level of maternal education ( Cupples et al., this issue-a ).

- - On average, children with PCHL required a better signal-to-noise ratio than their peers with normal hearing to achieve the same level of performance for speech perception in noise ( Ching et al., 2017b ).

- - On average, children with PCHL demonstrated spatial release from masking for speech perception in noise that is similar in magnitude to that of their peers with normal hearing ( Ching et al., 2017b ).

- - Children who had better language abilities also had better speech perception in noise ( Ching et al., 2017b ).

- - Earlier activation of CIs was associated with better speech perception in noise ( Ching et al., 2017b ).

- - Psychosocial skills as rated by parents showed that better performance was associated with better language ability and functional performance skills as measured by the Parents’ Evaluation of Aural/oral functional performance of Children (PEACH; Ching & Hill, 2007 ) scale at the same age ( Wong et al., this issue ).

The findings of the LOCHI study attest to the importance of early fitting of HAs or CIs soon after diagnosis. Table 1 gives a summary of these findings together with clinical implications.

Summary of findings and implications.

It is noteworthy that consistent usage of hearing devices has been established at an early age in the present cohort. Based on parents’ ratings, 62% of the cohort used their devices for more than 75% of their waking hours by three years of age ( Marnane & Ching, 2015 ). This proportion increased to 85% by five years of age.

Incorporating knowledge into clinical practice

The LOCHI study showed that language delay in children with PCHL is abatable, or in some cases, completely preventable. The earlier a child receives HAs or CIs, the better are the language and speech perception outcomes at five years of age. With the widespread implementation of UNHS, it is now possible for PCHL to be identified soon after birth. In order for timely amplification to occur soon after diagnosis, a seamless clinical pathway from screening to diagnosis to early fitting of devices is essential. Current practice in Australia requires that AH provides a post-diagnostic appointment at a hearing centre to a child diagnosed with PCHL at primary healthcare centres within 10 working days. The median HA fitting age of 3.5 months for those children in the LOCHI cohort who had access to UNHS is consistent with national fitting statistics ( Australian Hearing, 2017 ).

The LOCHI study has shown that HAs fitted to children provide consistent audibility to support speech and language development ( Ching et al., this issue ). These children received post-diagnostic services from AH according to national protocols ( King, 2010 ; Punch et al., 2016 ) that incorporated evidence-based guidelines for pediatric amplification as published by the American Academy of Audiology ( American Academy of Audiology Task Force on Pediatric Amplification, 2013 ). In a similar vein, Bagatto et al (2016) have reported on clinical feasibility of adopting the guidelines using specific protocols in the Ontario Infant Hearing Program, and showed that children wearing HAs achieved good outcomes when the protocols were executed.

Further, children who need CIs must receive them early to achieve the best language and speech perception outcomes. This, together with findings about the predictability of language scores from early PEACH scores ( Ching et al., 2013a ), have contributed to national protocols for pediatric referral for cochlear implantation and monitoring progress after amplification in Australia ( Ching et al., 2008 ; King, 2010 ). The protocols emphasise the need to evaluate the effectiveness of HAs for infants by using objective measurements of cortical auditory potentials evoked by speech at conversational levels and subjective parent reports using the PEACH scale ( Ching & Hill, 2007 ) as part of routine clinical practice ( Punch et al., 2016 ).

The LOCHI study provides some evidence to support the use of the PEACH scale as a clinical tool for evaluating the effectiveness of amplification in infants. Data from evaluation of the cohort at 3 years of age showed a significant positive relationship between PEACH scores based on parent ratings and standardised language scores measured by administering the Pre-school Language Scale ( Zimmerman et al., 2002 ) directly to children at the same age ( Ching et al., 2010 ). Furthermore, earlier PEACH performance evaluated at either 6 or 12 months after HA fitting was found to be a significant predictor of language outcomes measured at 3 years of age, after allowing for the effects of a range of demographic characteristics in the LOCHI study ( Ching et al., 2013a ).

The evidence suggests that the PEACH scale can be used as a means to monitor language development of children with hearing loss. The PEACH takes less than 15 mins to complete, whereas a standardised language test based on either parent reports or direct administration to a child requires much longer to complete. The PEACH specifically asks parents to observe and rate their child’s listening and communication skills in both quiet and noisy situations in real life, reflecting pragmatic aspects of spoken language and auditory behaviour. On the other hand, standardised tests are typically administered in ideal listening environments, viz, one-on-one in quiet. The PEACH can be administered by audiologists or other healthcare professionals, and does not require specific expertise in speech and language assessments. Further, the PEACH scale has the benefit of being suitable for use with young children and those who cannot complete standardised testing. As the scale is available in a range of languages (freely downloadable from www.outcomes.nal.gov.au ), it can also be used with families from non-English-speaking backgrounds. When used as part of routine management of infants under three years of age, the PEACH scale can be administered within a couple of months after initial HA fitting, and subsequently at 6-monthly intervals to track progress.

In addition, the PEACH scale can be a useful screening tool for identifying psychosocial deficits in young children. This is supported by findings on children in the LOCHI study at three years ( Leigh et al., 2015 ) and at five years of age. Wong et al (this issue) showed that even after accounting for demographic characteristics and language ability, functional communication as measured by the PEACH scale accounted for significant variance in psychosocial skills evaluated using standardised methods at five years of age.

Language ability was significantly associated with speech perception ( Ching et al., 2017b ) and psychosocial abilities ( Wong et al., this issue ). The direction of causation cannot be inferred from our results, but it seems likely that language ability both enables and is enabled by, good speech perception. The same may well be true of psychosocial development if children with closer to normal psychosocial development engage in more interactions with their peers and families than those with poorer psychosocial development ( Fellinger et al., 2009 ; Dammeyer, 2010 ).

Despite early fitting of hearing devices, children with PCHL require higher signal-to-noise ratios compared to their peers with normal hearing to achieve the same level of performance in speech perception ( Ching et al., 2017b ). Presumably, this is because of the degraded analytical ability of a damaged cochlea, which amplification cannot correct. This finding supports the provision of hearing technology that not only increases audibility but also improves signal-to-noise ratio to children with PCHL. Current AH protocols recommend the fitting of HAs with directional microphone technology and remote microphone systems to young children.

The report on children with disabilities in addition to PCHL showed that early amplification led to improved language outcomes ( Cupples et al., this issue-a ). Therefore, their access to early fitting of hearing devices should not be compromised. It is important to acknowledge, however, that children with additional disabilities, comprising about 37% of those with PCHL, will need extra support to optimise their language and other outcomes, support that will undoubtedly vary from child to child. Consistent with this view, previous findings for the LOCHI sample revealed that children with autism, cerebral palsy, and/or developmental delay differed from those with other disabilities (which included visual or speech impairment, syndromes not entailing developmental delay, and medical conditions) in attaining poorer language outcomes at three years of age ( Cupples et al., 2014 ); and showing a relative decline in language growth compared to norms from three to five years of age (Cupples et al., submitted). Findings such as these underscore the importance of establishing effective collaborations among professionals in the management of children with hearing loss who have additional disabilities in order to facilitate early treatment for hearing loss.

Future research

We have learnt that the earlier a child receives a CI, the better the language and speech perception outcomes. We have not yet found any limit to the age range over which this is true: language outcomes at five years of age monotonically increase as the age of implantation decreases, at least down to five months of age, the earliest age of implantation in our data ( Ching et al., 2017a ). Whereas the referral for CI candidacy maybe straightforward and well supported by evidence for children diagnosed with PCHL of a profound degree, referrals are more variable and evidence is less clear for those with hearing loss in the moderate to severe range. Currently, the decision to implant early in infants and young children is made almost exclusively on the basis of threshold elevation and its consequences for detection of speech sounds with amplification ( Lovett et al., 2015 ). For adults and older children, by contrast, the decision for implantation relies almost exclusively on the speech perception ability of the patient when wearing HAs ( Gifford et al., 2010 ; Leigh et al., 2011 ), as that has been found to be a more reliable indicator of implantation benefit than just hearing thresholds. Clinical tools that enable clinicians to assess auditory speech discrimination in infants are lacking.

Recent research has shown that measurements of objective auditory evoked potentials could reveal speech discrimination abilities in infants and young children ( Cheour-Luhtanen et al., 1995 ; Cone, 2015 ; Small et al., 2017 ). Other research groups have demonstrated the use of behavioural measures of discrimination by using a visual reinforcement paradigm ( Uhler et al., 2015 ). Our current research builds on these approaches, with the ultimate goal of developing clinical tools to identify infants with hearing loss who may have deficits in speech discrimination despite optimal amplification. It would then be possible for families to consider alternative treatment early, with the potential of enabling the infants to benefit from the earliest possible cochlear implantation.

Last but not least, the LOCHI study found that better language outcomes were associated with less severe hearing loss, higher nonverbal cognitive ability, absence of additional disabilities, use of speech for communication, and higher maternal education. The advantages of parental education for child development have been well documented ( Bornstein et al., 2010 ). There is some evidence to suggest that maternal education is related to language input and language environment ( Hoff, 2003 ; Dwyer, 2017 ), engagement in interaction ( Lam & Kitamura, 2012 ), emotional well-being ( Sarant & Garrard, 2014 ), perceived social support ( Ahlert & Greeff, 2012 ), and self-efficacy ( DesJardin, 2005 ). Future research into how better to support language development in children with PCHL, especially but not limited to those whose mothers did not complete university education or from lower socio-economic backgrounds, is essential ( Lam-Cassettari et al., 2015 ). To enable children with PCHL to achieve parity of outcomes with their normal-hearing peers, further research is needed to increase understanding about how spoken language can be best learnt in the presence of hearing loss, and what are the most effective ways for parents to promote communication.

The LOCHI study has shown that early fitting of hearing devices is key to achieving better speech, language and functional performance outcomes by five years of age. Better language and functional performance are associated with better speech perception and psychosocial development. The longitudinal nature of the study provides the opportunity to track development over time, and to investigate factors, including but not limited to age at intervention, that influence outcomes at different ages as well as rate of development.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully thank all the children, their families and their teachers for participation in the LOCHI study. We also acknowledge the assistance of the many clinicians who provided audiological management of the children, and the assistance of professionals at early intervention agencies and cochlear implant clinics in the collection of demographic and outcomes data. We thank Vicky Zhang for her assistance in the preparation of the manuscript.

Sources of funding

The LOCHI project is partly supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (Award Number R01DC008080). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders or the National Institutes of Health.

The work was also partly supported by the Commonwealth of Australia through the Office of Hearing Services. We acknowledge the financial support of the HEARing CRC, established and supported under the Cooperative Research Centres Program of the Australian Government. We also acknowledge the support provided by the New South Wales Department of Health, Australia; Phonak Ltd; and the Oticon Foundation.

Abbreviations

Conflicts of interest

None were declared.

- Ahlert IA, Greeff AP. Resilience factors associated with adaptation in families with deaf and hard of hearing children. Am Ann Deaf. 2012; 157 :391–404. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- American Academy of Audiology Task Force on Pediatric Amplification. American Academy of Audiology Clinical Practice Guidelines: Pediatric Amplification 2013 [ Google Scholar ]

- Australian Hearing. Demographic details of young Australians aged less than 26 years with a hearing loss, who have been fitted with a hearing aid or cochlear implant at 31 December 2016. Sydney, Australia: Australian Hearing; 2017. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bagatto M, Moodie S, Brown C, Malandrino A, Richert FM, et al. Prescribing and verifying hearing aids applying the American Academy of Audiology pediatric amplification guideline: Protocols and outcomes from the Ontario infant hearing program. J Am Acad Audiol. 2016; 27 :188–203. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bornstein MH, Cote LR, Haynes MO, Hahn CS, Park Y. Parenting knowledge: Experiential and sociodemographic factors in European American mothers of young children. Dev Psychol. 2010; 46 :1677–1693. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cheour-Luhtanen M, Alho K, Kujala T, Saino K, Reinikainen K, et al. Mismatch negativity indicates vowel discrimination in newborns. Hear Res. 1995; 82 :53–58. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Crowe K, Martin V, Day J, Mahler N, et al. Language development and everyday functioning of children with hearing loss assessed at 3 years of age. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2010; 12 :124–131. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Day J, Seeto M, Dillon H, Marnane V, et al. Predicting 3-year outcomes of early-identified children with hearing impairment. B-ENT. 2013a; 9 :99S–106S. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Dillon H. Major findings of the LOCHI study on children at 3 years of age and implications for audiological management. Int J Audiol. 2013; 52 :65S–68S. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Dillon H, Button L, Seeto M, Van Buynder P, et al. Age at intervention for permanent hearing loss and 5-year language outcomes. Pediatrics. 2017a; 140 :e20164274. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Dillon H, Hou S, Zhang V, Day J, et al. A randomised controlled comparison of NAL and DSL prescriptions for young children: Hearing aid characteristics and performance outcomes at 3 years of age. Int J Audiol. 2013b; 52 :17S–28S. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Dillon H, Marnane V, Hou S, Day J, et al. Outcomes of early- and late-identified children with hearing loss at 3 years of age: Findings from a prospective population-based study. Ear Hear. 2013c; 34 :535–552. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Hill M. The parent’s evaluation of aural/oral performance of children (PEACH) scale: Normative data. J Am Acad Audiol. 2007; 18 :220–235. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, King A, Dillon H. Evidence-based practice for cochlear implant referrals for infants. Australian Hearing. 2008 Available: https://www.hearing.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Evidence-based-practice-for-cochlear-implant-referrals-for-infants.pdf [Accessed 13 September 2017]

- Ching TYC, Leigh G, Dillon H. Introduction to the longitudinal outcomes of children with hearing impairment (LOCHI) study: Background, design, sample characteristics. Int J Audiol. 2013d; 52 :4S–9S. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Zhang VW, Flynn C, Burns L, Button L, et al. Factors influencing speech perception in noise for 5-year-old children using hearing aids or cochlear implants. Int J Audiol. 2017b doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017.1346307. Epub ahead of print. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ching TYC, Zhang VW, Johnson EE, Van Buynder P, Hou S, et al. Hearing aid fitting and developmental outcomes of children fit according to either the NAL or DSL prescription: Fit-to-target, audibility, speech and language abilities. Int J Audiol. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017.1380851. this issue. Epub ahead of print. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cone BK. Infant cortical electrophysiology and perception of vowel contrasts. Int J Psychophysiol. 2015; 95 :65–76. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cupples L, Ching TYC, Button L, Leigh G, Marnane V, et al. Language and speech outcomes of children with hearing loss and additional disabilities: Identifying the variables that influence performance at five years of age. Int J Audiol. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2016.1228127. this issue-a. Epub ahead of print. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cupples L, Ching TYC, Button L, Seeto M, Zhang V, et al. Spoken language and everyday functioning in 5-year-old children using hearing aids or cochlear implants. Int J Audiol. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017.1370140. this issue-b. Epub ahead of print. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cupples L, Ching TYC, Crowe K, Seeto M, Leigh G, et al. Outcomes of 3-year-old children with hearing loss and different types of additional disabilities. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2014; 19 :20–39. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cupples L, Ching TYC, Leigh G, Martin L, Gunnourie M, et al. Language development in deaf or hard-of-hearing children with additional disabilities: Type matters (submitted) J Intellect Disabil Res [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dammeyer J. Psychosocial development in a Danish population of children with cochlear implants and deaf and hard-of-hearing children. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2010; 15 :50–58. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- DesJardin JL. Maternal perceptions of self-efficacy and involvement in the auditory development of young children with prelingual deafness. J Early Interv. 2005; 27 :193–209. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dwyer A. PhD dissertation. University of Western Sydney; 2017. Early language experience and later vocabulary among Australian infants from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. [ Google Scholar ]

- Erbasi E, Scarinci N, Hickson L, Ching TYC. Parental involvement in the care and intervention of children with hearing loss. Int J Audiol. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2016.1220679. this issue. Epub ahead of print. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fellinger J, Holzinger D, Beitel C, Laucht M, Goldberg DP. The impact of language skills on mental health in teenagers with hearing impairments. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2009; 120 :153–159. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gifford RH, Dorman MF, Shallop JK, Sydlowski SA. Evidence for the expansion of adult cochlear implant candidacy. Ear Hear. 2010; 31 :186–194. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoff E. The specificity of environmental influence: Socioeconomic status affects early vocabulary development via maternal speech. Child Dev. 2003; 74 :1368–1378. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Incerti PV, Ching TYC, Hou S, Van Buynder P, Flynn C, et al. Programming characteristics of cochlear implants in children: Effects of etiology and age at implantation. Int J Audiol. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017.1370139. this issue. Epub ahead of print. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- King AM. The national protocol for paediatric amplification in Australia. Int J Audiol. 2010; 49 :64S–69S. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lam-Cassettari C, Wadnerkar-Kamble MB, James DM. Enhancing parent–child communication and parental self-esteem with a video-feedback intervention: Outcomes with prelingual deaf and hard-of-hearing children. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2015; 20 :266–274. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lam C, Kitamura C. Mommy, speak clearly: Induced hearing loss shapes vowel hyperarticulation. Dev Sci. 2012; 15 :212–21. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leigh G, Ching TYC, Dillon H, Day J, Seeto M. Factors affecting psychosocial and motor development in 3-year-old children who are deaf or hard of hearing. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2015; 20 :331–342. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Leigh J, Dettman S, Dowell R, Sarant J. Evidence-based approach for making cochlear implant recommendations for infants with residual hearing. Ear Hear. 2011; 32 :313–322. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lovett RE, Vickers DA, Summerfield AQ. Bilateral cochlear implantation for hearing-impaired children: criterion of candidacy derived from an observational study. Ear Hear. 2015; 36 :14–23. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marnane V, Ching TYC. Hearing aid and cochlear implant use in children with hearing loss at three years of age: Predictors of use and predictors of changes in use. Int J Audiol. 2015; 54 :544–551. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moeller MP, Carr G, Seaver L, Stredler-Brown A, Holzinger D. Best practices in family-centered early intervention for children who are deaf or hard of hearing: An international consensus statement. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2013; 18 :429–445. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Punch S, Van Dun B, King A, Carter L, Pearce W. Clinical experience of using cortical auditory evoked potentials (CAEPs) in the treatment of infant hearing loss in Australia. Sem Hear. 2016; 37 :36–52. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sarant J, Garrard P. Parenting stress in parents of children with cochlear implants: relationships among parent stress, child language, and unilateral versus bilateral implants. J Deaf Stud Deaf Educ. 2014; 19 :85–106. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scarinci N, Erbasi E, Moore E, Ching TYC, Marnane V. The parents’ perspective of the early diagnostic period of their child with hearing loss: Information and support. Int J Audiol. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2017. this issue. Epub ahead of print. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Small SA, Ishida IM, Stapells DR. Infant cortical auditory evoked potentials to lateralized noise shifts produced by changes in interaural time difference. Ear Hear. 2017; 38 :94–102. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Suissa J. Untangling the mother knot: some thoughts on parents, children and philosophers of education. Ethics Educ. 2006; 1 :65–77. [ Google Scholar ]

- Uhler KM, Baca R, Dudas E, Fredrickson T. Refining stimulus parameters in assessing infant speech perception using visual reinforcement infant speech discrimination: Sensation level. J Am Acad Audiol. 2015; 26 :807–814. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wong C, Ching TYC, Leigh G, Cupples L, Button L, et al. Psychosocial development of 5-year-old children with hearing loss: risks and protective factors. Int J Audiol. doi: 10.1080/14992027.2016.1211764. this issue. Epub ahead of print. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zimmerman I, Steiner VG, Pond RE. Preschool Language Scale. 4th. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2002. [ Google Scholar ]

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Scoping review of hearing loss attributed to congenital syphilis

Roles Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Pediatrics, Queen’s University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Research Investigator, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Roles Data curation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Affiliation Department of Anesthesiology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Division of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada

- Aleena Amjad Hafeeez,

- Karina Cavalcanti Bezerra,

- Zaharadeen Jimoh,

- Francesca B. Seal,

- Joan L. Robinson,

- Nahla A. Gomaa

- Published: April 26, 2024

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

There are no narrative or systematic reviews of hearing loss in patients with congenital syphilis.

The aim of this study was to perform a scoping review to determine what is known about the incidence, characteristics, prognosis, and therapy of hearing loss in children or adults with presumed congenital syphilis.

Eligibility criteria

PROSPERO, OVID Medline, OVID EMBASE, Cochrane Library (CDSR and Central), Proquest Dissertations and Theses Global, and SCOPUS were searched from inception to March 31, 2023. Articles were included if patients with hearing loss were screened for CS, ii) patients with CS were screened for hearing loss, iii) they were case reports or case series that describe the characteristics of hearing loss, or iv) an intervention for hearing loss attributed to CS was studied.

Sources of evidence

Thirty-six articles met the inclusion criteria.

Five studies reported an incidence of CS in 0.3% to 8% of children with hearing loss, but all had a high risk of bias. Seven reported that 0 to 19% of children with CS had hearing loss, but the only one with a control group showed comparable rates in cases and controls. There were 18 case reports/ case series (one of which also reported screening children with hearing loss for CS), reporting that the onset of hearing loss was usually first recognized during adolescence or adulthood. The 7 intervention studies were all uncontrolled and published in 1983 or earlier and reported variable results following treatment with penicillin, prednisone, and/or ACTH.

Conclusions

The current literature is not informative with regard to the incidence, characteristics, prognosis, and therapy of hearing loss in children or adults with presumed congenital syphilis.

Citation: Amjad Hafeeez A, Cavalcanti Bezerra K, Jimoh Z, Seal FB, Robinson JL, Gomaa NA (2024) Scoping review of hearing loss attributed to congenital syphilis. PLoS ONE 19(4): e0302452. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452

Editor: Bolajoko O. Olusanya, Center for Healthy Start Initiative, NIGERIA

Received: October 6, 2023; Accepted: April 2, 2024; Published: April 26, 2024

Copyright: © 2024 Hafeeez et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All data are in the manuscript and/or supporting information files.

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Syphilis is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum . If not recognized and treated early in pregnancy, fetal transmission commonly occurs [ 1 ]. According to the international Joint Committee on Infant Hearing, congenital syphilis (CS) is a risk indicator for hearing loss [ 2 , 3 ]. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention state: “Otosyphilis is caused by an infection of the cochleovestibular system with T . pallidum and typically presents with sensorineural hearing loss, tinnitus, or vertigo. Hearing loss can be unilateral or bilateral, have a sudden onset, and progress rapidly.” ( Neurosyphilis, Ocular Syphilis, and Otosyphilis ( cdc.gov ) ). Almost all cases of CS are treated with penicillin which is not known to be ototoxic.

For decades, congenital syphilis had almost disappeared in Canada and the United States due to low rates of syphilis in the community and universal prenatal screening.. The number of cases of confirmed early congenital syphilis born to women aged 15–39 years in Canada rose from 17 cases in 2018 to 117 in 2022 [ 4 ]. Trends in the United States (US) mirror this with an increase from 1325 congenital syphilis cases in 2018 to 3755 in 2022 [ 5 ].

The recent resurgence has increased interest in the clinical manifestations and complications of congenital syphilis. There are no published data summarizing the incidence or characteristics of hearing loss due to congenital syphilis. Despite the larger number of cases now occurring in Canada and the US, there are no evidence-based guidelines on screening or management of hearing loss in children with congenital syphilis. We therefore performed a scoping review. Our specific questions were:

- How often is hearing loss due to congenital syphilis?

- What is the incidence of hearing loss in children with congenital syphilis?

- When hearing loss occurs from congenital syphilis, what is the usual age of onset? Is it unilateral or bilateral? How severe is it? How rapidly does it progress?

- Is there evidence for any interventions for treatment of hearing loss attributed to congenital syphilis?

This will inform the studies that need to be done to determine the incidence and age of onset of hearing loss from CS, the severity of hearing loss, and interventions that warrant further study.

The methodology was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews: The PRISMA-ScR statement [ 6 ] (See attached S1 Checklist ). A search was executed by a health librarian on the following databases: PROSPERO, OVID Medline, OVID EMBASE, Cochrane Library (CDSR and Central), Proquest Dissertations and Theses Global, and SCOPUS using controlled vocabulary (e.g.: MeSH, Emtree, etc.) and selecting key words representing the concepts “congenital syphilis" or "hearing loss” ( S1 Appendix ). Databases were searched from inception to October 17, 2021, with an updated search to March 31, 2023.

Articles were included if they described persons of any age with hearing loss that the authors of the article attributed to congenital syphilis. To delineate the burden and incidence of hearing loss from congenital syphilis, we included any studies that i) screened children with hearing loss for evidence of congenital syphilis or ii) screened children with congenital syphilis for hearing loss. We also included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cross-sectional studies, case series, and case reports that described the characteristics of hearing loss, the long-term outcomes of hearing loss, or the results of any interventions for hearing loss. We excluded autopsy reports, animal studies, studies focusing solely on acquired syphilis and those published in a language other than English, French, or Portuguese.

Articles published in English were screened by two reviewers independently [AH, KC], and conflicts were resolved by a senior author [JR, NG]. Articles published in French had a single reviewer [FS]. There were no articles published in Portuguese. Because of the small number of recent articles, preprints were included. The protocol has not been published.

Studies were divided into four types: i) those that screened patients with hearing loss for congenital syphilis, ii) those that screened patients with congenital syphilis for hearing loss, iii) case reports or case series that describe the characteristics of hearing loss in patients with congenital syphilis, and iv) studies that describe an intervention for hearing loss attributed to congenital syphilis. Data were collected and managed using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) tools [ 7 ] hosted at the University of Alberta with the extracted data determined by the study type. Data were entered by a single investigator. The JBI critical appraisal tool was used as appropriate to assess all included studies [ 8 – 11 ] ( S2 Appendix ). The critical appraisal and bias risk assessment was completed by a single reviewer [NG], and all studies were rated as high, unclear or low risk of bias.

The search yielded 1983 records of which 832 were duplicates. Screening led to 159 records for full-text review of which 36 met inclusion criteria ( Fig 1 ). The figure outlines the reasons for exclusion of other records.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.g001

Screening of patients with hearing loss for congenital syphilis

There were 5 studies where patients with hearing loss were screened for CS. They were published from 1900 to 1990 and all had a high risk of bias (Tables 1 and 2 ). The incidence of CS ranged from 0.3% to 8% in children attending schools for the hearing impaired and was 2% in children seen at a clinic for the hearing impaired.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.t001

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.t002

Screening of patients with CS for hearing loss

There were 7 studies of which 4 were published from 2016 to 2022 ( Table 3 ). The risk of bias was high for 1, unclear for 3, and low for 3. Hearing loss was reported in 0 to 19% of children with probable or proven CS. One study from the modern era showed an incidence of 6% (22/342) (12). However, a small recent study reported no hearing loss for 7 infants treated in utero, a 5% incidence for 37 treated at birth, and a 6% incidence in 49 controls [ 23 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.t003

Case series and case reports of hearing loss attributed to CS

There were 10 case series (one of which was also included in Table 2 ) ( Table 4A ) and 8 case reports ( Table 4B ) of which all but 6 were published prior to 1980. The risk of bias was high for 5 articles, unclear for 3 and low for 10. In these reports, hearing loss was often first noted in adolescence or adulthood with the youngest being 5 years old at diagnosis. Many cases also had interstitial keratitis. Follow-up was too variable to allow determination of the expected rate of progression of hearing loss. A wide variety of therapies are reported with small numbers of patients and inconsistent results that were often subjective.

A ‐ Case series of hearing loss attributed to congenital syphilis. B ‐ Case reports of hearing loss attributed to congenital syphilis.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.t004

Studies with interventions for hearing loss

The 7 studies included a range of 6 to 39 patients with the most recent one being from 1983 ( Table 5 ). All were observational. Most commonly patients were prescribed penicillin with addition of prednisone followed by ACTH if response was poor or transient. Outcomes were often subjective and inconsistent. Risk of bias was unclear for 5 studies and low for 2 studies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.t005

The scoping review shows that studies of hearing loss due to congenital syphilis are limited and low quality. All but one study reported as a pre-print [ 23 ] are observational studies and only 15 of 36 studies (42%) were at low risk of bias. One cannot determine the incidence or characteristics of hearing loss from congenital syphilis or the efficacy of interventions from this review. It seems unlikely that a systematic review would find further studies that could answer these questions.

As expected, there were major variations in the study methodologies employed to diagnose hearing loss. In the early 1900s, investigators used basic tuning fork tests and subjective behavioral responses [ 24 ]. Studies performed after the year 2000, used full diagnostic tests or Auditory Brainstem Responses (ABR) for neonates [ 21 ].

A small percentage of children attending schools for the hearing impaired had evidence of congenital syphilis. However, these data are of limited value without a control group from the same jurisdiction. The percentage of hearing loss that is due to congenital syphilis no doubt varies considerably by country and over time.

It is perhaps unexpected that almost all case reports and case series describe recognition of hearing loss only in adolescence or adulthood. It is possible that hearing loss started years prior but was not recognized, particularly, if the hearing loss was slowly progressive. The major problem with all these reports is that they do not exclude the possibility that the patient had acquired syphilis or had another etiology for their hearing loss.

Clearly, there is paucity of up-to-date literature regarding this important health problem. The majority of articles were published before 1980. The recent surge in congenital syphilis cases in Canada and the United States may lead to further studies. Recent results from neonatal hearing screening programs in low- or middle-income countries where the incidence of congenital syphilis never waned are informative. Besen reported screening 21,434 newborns in Brazil 2017 through 2019 and reported a prevalence of test failure in the Universal Neonatal Hearing Screening Program (UNHS) of 1.6% (95% CI: 1.4; 1.8). This study used Otoacoustic Emission and ABR to identify both cochlear and retrocochlear damage. They report that 1.7% (95% CI: 1.5; 1.8) had congenital syphilis but do not report how many with congenital syphilis had hearing loss [ 22 ]. In a follow-up report of 34,801 infants screened 2017 through 2021, they report that neonates with congenital syphilis were 2.38 times as likely to fail in the UNHS as those without congenital syphilis [ 48 ]. However, another small study from Brazil reported as a pre-print examined failed hearing screens at 2 months of life did not find an association between congenital syphilis and failed hearing screens [ 23 ].

It is not clear whether there is a treatment for hearing loss due to congenital syphilis. Antibiotics were presumably always given at the time of diagnosis of hearing loss if the patient had not previously been adequately treated. There are no convincing reports that this alone resulted in sustained improved hearing. Uncontrolled studies that included corticosteroids with or without ACTH reported variable response and improvement in hearing was often subjective.

The main limitation of this scoping review is the lack of high-quality studies.

Our scoping review outlines a general map of the trend of publications across the decades and shows that the incidence of hearing loss due to congenital syphilis is completely unknown. It is not clear whether the stage of maternal syphilis or the age at which infants are treated changes outcomes. The literature does not inform us as to whether treatment in-utero prevents development of hearing loss. Until there are high quality long-term observational studies, it is difficult to know what hearing screening to recommend for children with congenital syphilis. Hearing loss attributed to congenital syphilis is often first recognized in adolescence or adulthood. Therefore, there is a need to increase awareness that people of all ages with unexplained hearing loss of sudden or gradual onset should be screened for syphilis. Other than treatment of the congenital syphilis, no other treatments can be recommended until there are RCTs or cohort studies with valid control groups.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses extension for scoping reviews (prisma-scr) checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.s001

S1 Appendix. Systematic review search strategy.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.s002

S2 Appendix. Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0302452.s003

- 1. Public Health Agency of Canada T. The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada. Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014.

- 2. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing T. Year 2019 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs. Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention. 2019;4(2).

- 3. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing T. Year 2007 Position Statement: Principles and Guidelines for Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Programs. Pediatrics. 2007;120(4):898–921.

- 4. Public Health Agency of Canada T. Infectious syphilis and congenital syphilis in Canada, 2022.) CCDR: Volume 49–10, October 2023: Influenza and Other Respiratory Infections ‐ Canada.ca

- 5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention T. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2022. Sexually Transmitted Infections Surveillance, 2022 ( cdc.gov ).

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 9. Moola S MZ, Tufanaru C, Aromataris E, Sears K, Sfetcu R, Currie M, et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E MZ, editor. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. New Zealand: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2020.

- 10. Joanna Briggs I. Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports. New Zealand: Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- Your Health

- Treatments & Tests

- Health Inc.

- Public Health

Reproductive rights in America

What's at stake as the supreme court hears idaho case about abortion in emergencies.

Selena Simmons-Duffin

The Supreme Court will hear another case about abortion rights on Wednesday. Protestors gathered outside the court last month when the case before the justices involved abortion pills. Tom Brenner for The Washington Post/Getty Images hide caption

The Supreme Court will hear another case about abortion rights on Wednesday. Protestors gathered outside the court last month when the case before the justices involved abortion pills.

In Idaho, when a pregnant patient has complications, abortion is only legal to prevent the woman's death. But a federal law known as EMTALA requires doctors to provide "stabilizing treatment" to patients in the emergency department.

The Biden administration sees that as a direct conflict, which is why the abortion issue is back – yet again – before the Supreme Court on Wednesday.

The case began just a few weeks after the justices overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022, when the federal Justice Department sued Idaho , arguing that the court should declare that "Idaho's law is invalid" when it comes to emergency abortions because the federal emergency care law preempts the state's abortion ban. So far, a district court agreed with the Biden administration, an appeals court panel agreed with Idaho, and the Supreme Court allowed the strict ban to take effect in January when it agreed to hear the case.

Supreme Court allows Idaho abortion ban to be enacted, first such ruling since Dobbs

The case, known as Moyle v. United States (Mike Moyle is the speaker of the Idaho House), has major implications on everything from what emergency care is available in states with abortion bans to how hospitals operate in Idaho. Here's a summary of what's at stake.

1. Idaho physicians warn patients are being harmed

Under Idaho's abortion law , the medical exception only applies when a doctor judges that "the abortion was necessary to prevent the death of the pregnant woman." (There is also an exception to the Idaho abortion ban in cases of rape or incest, only in the first trimester of the pregnancy, if the person files a police report.)

In a filing with the court , a group of 678 physicians in Idaho described cases in which women facing serious pregnancy complications were either sent home from the hospital or had to be transferred out of state for care. "It's been just a few months now that Idaho's law has been in effect – six patients with medical emergencies have already been transferred out of state for [pregnancy] termination," Dr. Jim Souza, chief physician executive of St. Luke's Health System in Idaho, told reporters on a press call last week.

Those delays and transfers can have consequences. For example, Dr. Emily Corrigan described a patient in court filings whose water broke too early, which put her at risk of infection. After two weeks of being dismissed while trying to get care, the patient went to Corrigan's hospital – by that time, she showed signs of infection and had lost so much blood she needed a transfusion. Corrigan added that without receiving an abortion, the patient could have needed a limb amputation or a hysterectomy – in other words, even if she didn't die, she could have faced life-long consequences to her health.

Attorneys for Idaho defend its abortion law, arguing that "every circumstance described by the administration's declarations involved life-threatening circumstances under which Idaho law would allow an abortion."

Ryan Bangert, senior attorney for the Christian legal powerhouse Alliance Defending Freedom, which is providing pro-bono assistance to the state of Idaho, says that "Idaho law does allow for physicians to make those difficult decisions when it's necessary to perform an abortion to save the life of the mother," without waiting for patients to become sicker and sicker.

Still, Dr. Sara Thomson, an OB-GYN in Boise, says difficult calls in the hospital are not hypothetical or even rare. "In my group, we're seeing this happen about every month or every other month where this state law complicates our care," she says. Four patients have sued the state in a separate case arguing that the narrow medical exception harmed them.

"As far as we know, we haven't had a woman die as a consequence of this law, but that is really on the top of our worry list of things that could happen because we know that if we watch as death is approaching and we don't intervene quickly enough, when we decide finally that we're going to intervene to save her life, it may be too late," she says.

2. Hospitals are closing units and struggling to recruit doctors

Labor and delivery departments are expensive for hospitals to operate. Idaho already had a shortage of providers, including OB-GYNS. Hospital administrators now say the Idaho abortion law has led to an exodus of maternal care providers from the state, which has a population of 2 million people.

Three rural hospitals in Idaho have closed their labor-and-delivery units since the abortion law took effect. "We are seeing the expansion of what's called obstetrical deserts here in Idaho," said Brian Whitlock, president and CEO of the Idaho Hospital Association.

Since Idaho's abortion law took effect, nearly one in four OB-GYNs have left the state or retired, according to a report from the Idaho Physician Well-Being Action Collaborative. The report finds the loss of doctors who specialize in high-risk pregnancies is even more extreme – five of nine full time maternal-fetal medicine specialists have left Idaho.

Administrators say they aren't able to recruit new providers to fill those positions. "Since [the abortion law's] enactment, St. Luke's has had markedly fewer applicants for open physician positions, particularly in obstetrics. And several out-of-state candidates have withdrawn their applications upon learning of the challenges of practicing in Idaho, citing [the law's] enactment and fear of criminal penalties," reads an amicus brief from St. Luke's health system in support of the federal government.

"Prior to the abortion decision, we already ranked 50th in number of physicians per capita – we were already a strained state," says Thomson, the doctor in Boise. She's experienced the loss of OB-GYN colleagues first hand. "I had a partner retire right as the laws were changing and her position has remained open – unfilled now for almost two years – so my own personal group has been short-staffed," she says.

ADF's Bangert says he's skeptical of the assertion that the abortion law is responsible for this exodus of doctors from Idaho. "I would be very surprised if Idaho's abortion law is the sole or singular cause of any physician shortage," he says. "I'm very suspicious of any claims of causality."

3. Justices could weigh in on fetal "personhood"

The state of Idaho's brief argues that EMTALA actually requires hospitals "to protect and care for an 'unborn child,'" an argument echoed in friend-of-the-court briefs from the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and a group of states from Indiana to Wyoming that also have restrictive abortion laws. They argue that abortion can't be seen as a stabilizing treatment if one patient dies as a result.

Thomson is also Catholic, and she says the idea that, in an emergency, she is treating two patients – the fetus and the mother – doesn't account for clinical reality. "Of course, as obstetricians we have a passion for caring for both the mother and the baby, but there are clinical situations where the mom's health or life is in jeopardy, and no matter what we do, the baby is going to be lost," she says.

The Idaho abortion law uses the term "unborn child" as opposed to the words "embryo" or "fetus" – language that implies the fetus has the same rights as other people.

Shots - Health News

The science of ivf: what to know about alabama's 'extrauterine children' ruling.

Mary Ziegler , a legal historian at University of California - Davis, who is writing a book on fetal personhood, describes it as the "North Star" of the anti-abortion rights movement. She says this case will be the first time the Supreme Court justices will be considering a statute that uses that language.

"I think we may get clues about the future of bigger conflicts about fetal personhood," she explains, depending on how the justices respond to this idea. "Not just in the context of this statute or emergency medical scenarios, but in the context of the Constitution."

ADF has dismissed the idea that this case is an attempt to expand fetal rights. "This case is, at root, a question about whether or not the federal government can affect a hostile takeover of the practice of medicine in all 50 states by misinterpreting a long-standing federal statute to contain a hidden nationwide abortion mandate," Bangert says.

4. The election looms large

Ziegler suspects the justices will allow Idaho's abortion law to remain as is. "The Supreme Court has let Idaho's law go into effect, which suggests that the court is not convinced by the Biden administration's arguments, at least at this point," she notes.

Trump backed a federal abortion ban as president. Now, he says he wouldn't sign one

Whatever the decision, it will put abortion squarely back in the national spotlight a few months before the November election. "It's a reminder on the political side of things, that Biden and Trump don't really control the terms of the debate on this very important issue," Zielger observes. "They're going to be things put on everybody's radar by other actors, including the Supreme Court."

The justices will hear arguments in the case on Wednesday morning. A decision is expected by late June or early July.

Correction April 23, 2024

An earlier version of this story did not mention the rape and incest exception to Idaho's abortion ban. A person who reports rape or incest to police can end a pregnancy in Idaho in the first trimester.

- Abortion rights

- Supreme Court

Scoping review of hearing loss attributed to congenital syphilis

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Pediatrics, Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

- 2 Research Investigator, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- 3 Department of Nursing, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- 4 Department of Anesthesiology, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- 5 Department of Pediatrics, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- 6 Division of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

- PMID: 38669285

- PMCID: PMC11051613

- DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0302452

Background: There are no narrative or systematic reviews of hearing loss in patients with congenital syphilis.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to perform a scoping review to determine what is known about the incidence, characteristics, prognosis, and therapy of hearing loss in children or adults with presumed congenital syphilis.

Eligibility criteria: PROSPERO, OVID Medline, OVID EMBASE, Cochrane Library (CDSR and Central), Proquest Dissertations and Theses Global, and SCOPUS were searched from inception to March 31, 2023. Articles were included if patients with hearing loss were screened for CS, ii) patients with CS were screened for hearing loss, iii) they were case reports or case series that describe the characteristics of hearing loss, or iv) an intervention for hearing loss attributed to CS was studied.

Sources of evidence: Thirty-six articles met the inclusion criteria.

Results: Five studies reported an incidence of CS in 0.3% to 8% of children with hearing loss, but all had a high risk of bias. Seven reported that 0 to 19% of children with CS had hearing loss, but the only one with a control group showed comparable rates in cases and controls. There were 18 case reports/ case series (one of which also reported screening children with hearing loss for CS), reporting that the onset of hearing loss was usually first recognized during adolescence or adulthood. The 7 intervention studies were all uncontrolled and published in 1983 or earlier and reported variable results following treatment with penicillin, prednisone, and/or ACTH.

Conclusions: The current literature is not informative with regard to the incidence, characteristics, prognosis, and therapy of hearing loss in children or adults with presumed congenital syphilis.

Copyright: © 2024 Hafeeez et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Hearing Loss* / etiology

- Syphilis, Congenital* / complications

- Syphilis, Congenital* / diagnosis

- Syphilis, Congenital* / drug therapy

- Syphilis, Congenital* / epidemiology

Grants and funding

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS