- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

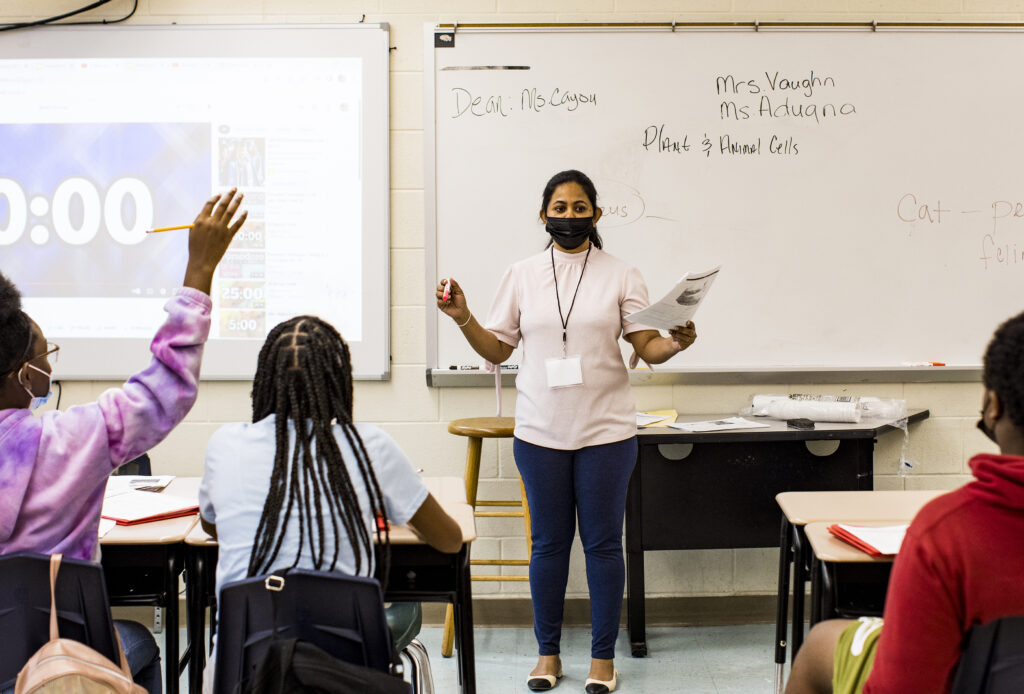

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, how to write a case study: the basics.

The purpose of a case study is to walk the reader through a situation where a problem is presented, background information provided and a description of the solution given, along with how it was derived. A case study can be written to encourage the reader to come up with his or her own solution or to review the solution that was already implemented. The goal of the writer is to give the reader experiences similar to those the writer had as he or she researched the situation presented.

Several steps must be taken before actually writing anything:

- Choose the situation on which to write

- Gather as much information as possible about the situation

- Analyze all of the elements surrounding the situation

- Determine the final solution implemented

- Gather information about why the solution worked or did not work

From these steps you will create the content of your case study.

Describe the situation/problem

The reader needs to have a clear understanding of the situation for which a solution is sought. You can explicitly state the problem posed in the study. You can begin by sharing quotes from someone intimate with the situation. Or you can present a question:

- ABC Hospital has a higher post-surgical infection rate than other health care facilities in the area.

- The Director of Nursing at ABC Hospital stated that “In spite of following rigid standards, we continue to experience high post-surgical infection rates”

- Why is it that the post-surgical infection rate at ABC Hospital higher than any other health center in the area?

This sets the tone for the reader to think of the problem while he or she read the rest of the case study. This also sets the expectation that you will be presenting information the reader can use to further understand the situation.

Give background

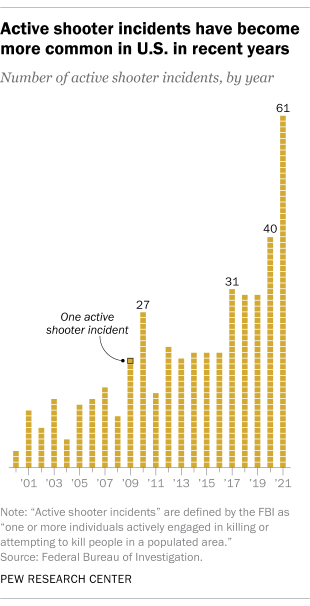

Background is the information you discovered that describes why there is a problem. This will consist of facts and figures from authoritative sources. Graphs, charts, tables, photos, videos, audio files, and anything that points to the problem is useful here. Quotes from interviews are also good. You might include anecdotal information as well:

“According to previous employees of this facility, this has been a problem for several years”

What is not included in this section is the author’s opinion:

“I don’t think the infection review procedures are followed very closely”

In this section you give the reader information that they can use to come to their own conclusion. Like writing a mystery, you are giving clues from which the reader can decide how to solve the puzzle. From all of this evidence, how did the problem become a problem? How can the trend be reversed so the problem goes away?

A good case study doesn’t tell the readers what to think. It guides the reader through the thought process used to create the final conclusion. The readers may come to their own conclusion or find fault in the logic being presented. That’s okay because there may be more than one solution to the problem. The readers will have their own perspective and background as they read the case study.

Describe the solution

This section discusses the solution and the thought processes that lead up to it. It guides the reader through the information to the solution that was implemented. This section may contain the author’s opinions and speculations.

Facts will be involved in the decision, but there can be subjective thinking as well:

“Taking into account A, B and C, the committee suggested solution X. In lieu of the current budget situation, the committee felt this was the most prudent approach”

Briefly present the key elements used to derive the solution. Be clear about the goal of the solution. Was it to slow down, reduce or eliminate the problem?

Evaluate the response to the solution

If the case study is for a recent situation, there may not have been enough time to determine the overall effect of the solution:

“New infection standards were adopted in the first quarter and the center hopes to have enough information by the year’s end to judge their effectiveness”

If the solution has been in place for some time, then an opportunity to gather and review facts and impressions exists. A summary of how well the solution is working would be included here.

Tell the whole story

Case study-writing is about telling the story of a problem that has been fixed. The focus is on the evidence for the problem and the approach used to create a solution. The writing style guides the readers through the problem analysis as if they were part of the project. The result is a case study that can be both entertaining and educational.

You may also like to read

- 5 Study Skills That Can Be Taught

- When to Write a Letter of Support

- How to Write a Letter of Intent

- The Homework Debate: The Case Against Homework

- Inclusive Education: What It Means, Proven Strategies, and a Case Study

- Examples of How To Write a Letter of Support

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Adult Learners , Language Arts

- Programming Teacher: Job Description and Sala...

- Teaching Language Arts: Resources for Educato...

- Online & Campus Bachelor's in Secondary Educa...

- Publications

- Conferences & Events

- Professional Learning

- Science Standards

- Awards & Competitions

- Daily Do Lesson Plans

- Free Resources

- American Rescue Plan

- For Preservice Teachers

NCCSTS Case Collection

- Partner Jobs in Education

- Interactive eBooks+

- Digital Catalog

- Regional Product Representatives

- e-Newsletters

- Bestselling Books

- Latest Books

- Popular Book Series

- Prospective Authors

- Web Seminars

- Exhibits & Sponsorship

- Conference Reviewers

- National Conference • Denver 24

- Leaders Institute 2024

- National Conference • New Orleans 24

- Submit a Proposal

- Latest Resources

- Professional Learning Units & Courses

- For Districts

- Online Course Providers

- Schools & Districts

- College Professors & Students

- The Standards

- Teachers and Admin

- eCYBERMISSION

- Toshiba/NSTA ExploraVision

- Junior Science & Humanities Symposium

- Teaching Awards

- Climate Change

- Earth & Space Science

- New Science Teachers

- Early Childhood

- Middle School

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Informal Education

- Journal Articles

- Lesson Plans

- e-newsletters

- Science & Children

- Science Scope

- The Science Teacher

- Journal of College Sci. Teaching

- Connected Science Learning

- NSTA Reports

- Next-Gen Navigator

- Science Update

- Teacher Tip Tuesday

- Trans. Sci. Learning

MyNSTA Community

- My Collections

Case Study Listserv

Permissions & Guidelines

Submit a Case Study

Resources & Publications

Enrich your students’ educational experience with case-based teaching

The NCCSTS Case Collection, created and curated by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science, on behalf of the University at Buffalo, contains over a thousand peer-reviewed case studies on a variety of topics in all areas of science.

Cases (only) are freely accessible; subscription is required for access to teaching notes and answer keys.

Subscribe Today

Browse Case Studies

Latest Case Studies

Development of the NCCSTS Case Collection was originally funded by major grants to the University at Buffalo from the National Science Foundation , The Pew Charitable Trusts , and the U.S. Department of Education .

- Publications

Innovation spotlights: Case studies in high school redesign

- Covid-19 , Equity in Education , Innovation and the Future of Learning

- September 2023

Educators nationwide are forging their way in a landscape rocked by pandemic-induced disruptions. Training resources designed to spark new thinking among school staff often feel outdated—especially if they were published before 2020. To address this need, the Center on Reinventing Public Education at Arizona State University and the Center for Public Research and Leadership (CPRL) at Columbia University have have crafted a set of dynamic new training materials. These teaching cases highlight high schools that have distinguished themselves though boldly redesigning and improving the student experience.

Our case studies invite participants to consider authentic dilemmas at innovative high schools where we’ve conducted on-the-ground research and interviews. The narratives of each school and accompanying questions are designed to generate grounded, in-depth discussions of key issues related to innovation and equity in high school education. Each teaching case is intended for groups of leaders and design teams who are learning about or engaged in high school reinvention.

Teachers, school staff, and design teams can work through the following cases. Use the links to download each case, or click the button below to download all five.

- Grades as a lever to support student learning: One school’s attempt to rethink traditional grading . This case study describes East Hartford High School’s (Hartford, CT) Grading for Equity implementation, including educators’ focus on maintaining high standards and ensuring students graduate career- and college-ready. It concludes with important questions for those seeking to test out innovative approaches to grading.

- Should daily attendance be a measure of success? Prioritizing community building and student engagement . This case from Nowell Academy in Providence, RI prompts high school leaders to wrestle with how to balance working to boost students’ engagement and ownership of their educational journeys while also working to increase attendance.

- Different choices, equal chances: Helping high school students achieve success on their own terms . This case, from Nokomis Regional High School in rural Newport, ME, wrestles with how high schools can expand students’ postsecondary horizons while remaining responsive to their values and interests–especially if those values differ significantly from those of the adults who support them.

- From enrollment to completion: Supporting equitable outcomes in challenging coursework . This case describes Maloney High School’s (Meriden, CT) outreach and support strategies for increasing underrepresented students’ access to challenging courses, and concludes with important questions for those focused on ensuring that equitable access results in equitable outcomes.

- Is a diploma enough? Setting ambitious visions for success in high schools . This case from Opportunity Academy, which operates as a “school within a school” at Holyoke High School in Holyoke, MA, grapples with what’s needed to achieve a higher bar for students who often just want to get high school over with—but whose success beyond the K-12 system depends on life skills, supportive relationships, and concrete postsecondary plans in addition to a diploma.

- A new normal: Maintaining high expectations and flexibility for high school students . KIPP Academy Lynn Collegiate has come a long way from its roots as a “no excuses” charter school by introducing more flexibility, relationship-rich support services, and opportunities for students to influence decisions at school and define postsecondary success for themselves. However, the pandemic and related challenges of recent years have caused KALC leadership to reexamine the optimal balance between holding students accountable to high expectations and allowing them flexibility in when and how to meet those expectations.

These case studies are part of Think Forward New England , a project launched in 2020 to study and support pandemic-era innovations that deliver what students and families need and want from high school. Look for three additional teaching cases coming later this year.

Chelsea Waite

Cara Pangelinan

Research analyst.

Center for Public Research and Leadership

Naureen Madhani

Director of research strategy and consulting, cprl.

Heather Casimere

Research assistant.

Julia Skwarczynski

Guest author.

Joanna Pisacone

Related publications, a “good life” after high school: how schools can help students prepare, a “good life” for every student: high schools embrace many pathways to success, for these six schools, pandemic-era innovation demanded “know thyself”, new england profiles of innovation | great oaks charter school bridgeport, emnet shibre, katrina woodworth, new england profiles of innovation | holyoke high school, new england profiles of innovation | margarita muñiz academy, caroline e. parker, new england profiles of innovation | nokomis regional high school, sarah mccann, new england profiles of innovation | map academy, new england profiles of innovation | common ground high school.

- ©2024 CRPE. All rights reserved.

- 600 First Avenue, Suite 206

- Seattle, WA 98104

Case Method Project

- Harvard Business School →

- Case Method Project →

Bringing case method teaching to high schools & colleges: U.S. History, Government, Civics & Democracy

About the project .

The Case Method Project is an initiative formed to achieve two goals:

- Bring case method teaching to high schools and colleges

- Use this methodology to deepen students’ understanding of American democracy

Based on the highly successful experience of Harvard Business School and other graduate and professional programs that use case-based teaching, we believe the case method can be employed to strengthen high school and college education as well, ensuring a more exciting, relevant, and effective experience for students and teachers across a range of subjects. We also believe the case method can be especially effective at engaging students with topics in history and democracy and that it presents a unique opportunity to help reverse the broad decline in civic education – and civic engagement – in the United States.

Curriculum

For current partners .

Already working with the Case Method Project?

Connect to other educators in our network and download case materials via ShareVault .

For Prospective Partners

Interested in learning more about the Case Method Project?

Find out how to bring the case method to your school.

Eleanor Cannon Houston, TX Eleanor Cannon Houston, TX

Maureen O’Hern Dorchester, MA Maureen O’Hern Dorchester, MA

Michael Gordon Munster, IN Michael Gordon Munster, IN

“ I have had few weeks in teaching that I enjoyed as much as doing this case....My biggest dilemma now is how many cases I want to fit into the year. ”

In the News

A Better Way to Teach History

- The Atlantic

Rewriting History

- HBS Alumni Bulletin

All Hail Partisan Politics

- Harvard Gazette

How to Teach Civics in School

- The Economist

- Case Teaching Resources

Teaching With Cases

Included here are resources to learn more about case method and teaching with cases.

What Is A Teaching Case?

This video explores the definition of a teaching case and introduces the rationale for using case method.

Narrated by Carolyn Wood, former director of the HKS Case Program

Learning by the Case Method

Questions for class discussion, common case teaching challenges and possible solutions, teaching with cases tip sheet, teaching ethics by the case method.

The case method is an effective way to increase student engagement and challenge students to integrate and apply skills to real-world problems. In these videos, Using the Case Method to Teach Public Policy , you'll find invaluable insights into the art of case teaching from one of HKS’s most respected professors, Jose A. Gomez-Ibanez.

Chapter 1: Preparing for Class (2:29)

Chapter 2: How to begin the class and structure the discussion blocks (1:37)

Chapter 3: How to launch the discussion (1:36)

Chapter 4: Tools to manage the class discussion (2:23)

Chapter 5: Encouraging participation and acknowledging students' comments (1:52)

Chapter 6: Transitioning from one block to the next / Importance of body (2:05)

Chapter 7: Using the board plan to feed the discussion (3:33)

Chapter 8: Exploring the richness of the case (1:42)

Chapter 9: The wrap-up. Why teach cases? (2:49)

4 Case Studies: Schools Use Connections to Give Every Student a Reason to Attend

- Share article

Students who feel connected to school are more likely to attend and perform well, and less likely to misbehave and feel sad and hopeless. There are even health benefits well into adulthood linked to a strong connection to school as an adolescent.

But schools are confronting a range of problems that stem at least in part from a lack of connection—perhaps most visibly: stubborn, nationwide increases in chronic absenteeism .

As they try to boost attendance and keep students engaged, some schools are turning to strategies built around the idea of connectedness. They’ve taken steps to more deliberately cultivate trusting relationships among students and adults in the building. They’ve tried to boost students’ participation in extracurricular activities to ensure they have a place at school where they feel as if they belong. And they’ve collected student feedback on what they’re learning and responded accordingly.

The work lines up with school connectedness strategies the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has said are effective at reducing unhealthy behaviors and strengthening students’ engagement.

Here’s how two high schools and two school districts are putting student connectedness at the center of their improvement efforts.

Dive into each case study:

- Making 9th graders feel seen and heard

- Probing why some students feel they don’t belong

- Making relationships part of an early-warning system

- Using connections to battle chronic absenteeism

A Chicago school wants 9th graders to feel seen and heard

Thomas Kelly College Preparatory, Chicago

Educators at Thomas Kelly College Preparatory have homed in on freshman year as a key time to make sure students have a strong connection to the Chicago high school.

“If you’re a 9th grader, nothing is more important to you than belonging,” said Grace Gunderson, a counselor at the 1,700-student school who leads its newly formed freshman success team. “If we can get those kids involved in band or, ‘Hey, I play on the soccer team,’ or, ‘Hey, I always eat lunch in Ms. Gunderson’s office,’ now they have a connection. They have a reason to keep coming to school.”

Kelly’s efforts began with hearing from students. In the first iteration of a survey called Elevate that the school now administers to all students quarterly, students said they didn’t think teachers cared about them, they thought classes were boring, and they didn’t think what they were learning was relevant to what they wanted to do in life, Principal Raul Magdaleno said.

With that insight, school staff—led by the five-member freshman success team—deployed a range of initiatives, both large and small, to foster belonging. They worked on making sure students had a relationship with a trusted adult, that more were participating in extracurricular activities, that the school building was inviting, and that students knew their opinions mattered.

One effort was a “Freshman Cafe,” a spring event last year where nearly all the school’s 500 freshmen sat down one-on-one with an adult for five to 10 minutes and discussed how the school year had gone, asked questions about sophomore year, reviewed attendance and grades and set goals for the remainder of the year, and talked about clubs they could join. Staff members ranging from the dean to security guards participated.

Before the current freshman class arrived at Kelly last summer, the school started sending regular communications to incoming 9th graders introducing them to the school and staff members, held community-building activities for incoming freshmen run by college mentors through a “Freshman Connection” program, and hosted an outdoor “Freshman Fiesta” with snacks and swag, where students had the chance to meet teachers.

It’s definitely still a work in progress. But I think the students understand now that we want their feedback, we genuinely want to know what they think, and they feel as if their opinions are valued.

And once the school year began, the freshman success team made sure an adult would regularly check in with students flagged as high risk in the Chicago schools’ “Risk and Opportunity” framework, which uses 8th grade attendance and grades to predict students’ likelihood of success in high school.

The school relied on teachers and other staff members in the building who volunteered to do these check-ins as well as college-age mentors working through a community group, the Brighton Park Neighborhood Council, “just so they have somebody else aside from their teachers that’s talking to them, that shows them that they care, that they’re interested in their experience,” said Griselda Esparza, an assistant principal at Kelly.

In classrooms, after students said they thought classes were boring and disconnected, Kelly made this year the year of “meaningful work,” with teachers starting to rethink their instruction to make it more “culturally relevant and rigorous,” Magdaleno said.

Teachers have started working in their professional learning communities to examine whether what they’re teaching is personally relevant to students and connected to life outside the classroom. They’re also focused on whether students have opportunities to make choices about what they’re learning.

“It’s definitely still a work in progress,” Gunderson said. “But I think the students understand now that we want their feedback, we genuinely want to know what they think, and they feel as if their opinions are valued.”

A New York district probes why some students feel they don’t belong

Arlington Central School District, New York

When the Arlington Central school district in New York surveyed students after their return to campus from pandemic closures, staff discovered that older students, students of color, and students in special education felt a weaker sense of belonging at school.

So, staff from the 7,800-student district started speaking with students from those populations to get to the bottom of the problem.

In focus groups, students told staff that books they read in class weren’t relevant and that they weren’t hearing enough viewpoints in history classes. Students who weren’t athletes or musicians said they had no way to connect to their school community.

“We learned a lot, and that helped us prioritize,” said Daisy Rodriguez, the district’s assistant superintendent for curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

A first response was holding high school activity fairs, bringing information to students about clubs they could join rather than having them seek it out on their own. More informally, administrators sat with kids in the cafeteria to talk to them about their interests and potential clubs to add to the school’s roster.

Working with department coordinators, the district conducted curriculum audits, looking at the texts students were assigned and exploring whether they could swap in more relevant and current selections. And the high school added career and technical education offerings.

High school students also sit on curriculum teams, Rodriguez said. “They give us immediate feedback on programs and resources that we’re thinking about and if it makes sense to them,” she said.

At the district’s middle schools, Arlington last year established regular advisory periods, with groups of students assigned to the same adviser all three years so they can form stronger connections and don’t have to hit reset every fall. The time is set aside for regular check-ins and social-emotional learning.

We know that when kids feel like they belong in school, they have better attendance, they have better academic achievement, and just greater social-emotional support.

“Students have reported that they do feel that it’s helpful for them because they actually have a space that they can go to and talk about things that they can’t talk about necessarily in other settings,” Rodriguez said.

The district wants older students to lead more of these sessions in coming years, and it would ultimately like to bring advisory periods to the high school.

At the elementary level, students now have daily morning meetings, a time set aside for social-emotional learning and work on communication skills.

So far, the district has seen some positive results—a reduction in chronic absenteeism that Rodriguez attributes at least in part to the district’s work on connectedness.

“We know that when kids feel like they belong in school, they have better attendance, they have better academic achievement, and just greater social-emotional support,” she said.

A New Mexico high school makes relationships part of its early-warning system

Manzano High School, Albuquerque, N.M.

Manzano High School in Albuquerque, N.M., relies on a dedicated advisory time so students build strong connections with staff who can then spot warning signs that a student might be falling behind.

The 30-minute advisory period that happens every Monday isn’t new to the 1,300-student high school. What’s new about it is that, over the past couple of years, advisers have been expected to check in with their advisees and, using the school’s student-information system, review their grades, attendance, and behavior over the prior week.

If a student is struggling, the adviser fills out a referral form and sends it to one of the school’s five student-success teams, each of which includes an academic counselor. That team starts working with the student to identify a root cause of their challenges and potential solutions.

The advisory period’s conversion to a key component of Manzano’s early warning, or student success, system has involved training for staff members on becoming deliberate listeners and lunch-and-learn sessions on building relationships with students, said Jeanie Stark, the school’s student-success systems coordinator.

“When you’re listening to the students, it’s listening to what they’re saying and maybe even listening to a little bit beyond that to get to that root cause,” she said. “And you may or may not respond right away.”

It’s still a work in progress. The school has work to do to ensure all advisers are using the student-success system as the framework for conversations with students, Principal Rachel Vigil said.

Attendance has improved this year, and the number of students requiring student-success-team referrals has been dropping, Stark said. But a more immediate sign that the check-ins and related work have been successful is feedback from students.

Last spring, Manzano staff interviewed students whom advisers had referred to a student-success team. Of all the help they’d received, the regular check-ins were the most meaningful and helpful, the students said.

“Students were saying, ‘We do better when we have people doing those one-on-one check-ins,’” Vigil said. “Just, ‘Hey, how are you doing?’ It doesn’t even have to be academic.”

Grades and attendance data are readily available through the student-information system, Stark said, but students “want a lot of communication. They want that teacher to talk to them, and they want them to tell them how they’re doing.”

Now, the Albuquerque district wants to spread Manzano’s work. It’s working with other high schools in the city to craft their own student-success systems, and some of Albuquerque’s middle schools are figuring out what a student-success system looks like for younger students, said Sheri Jett, Albuquerque’s associate superintendent for school climate and supports, a new position.

Working with the student-survey company Panorama, Albuquerque has also begun conducting regular student surveys on students’ skills, habits, and mindset. Manzano staff hope these surveys will provide them with even more student feedback they can use to tailor their student-success system.

In Washington state, a district uses connections to battle chronic absenteeism

Tacoma Public Schools, Washington state

The Tacoma, Wash., school district’s work over the past two years to cut chronic absenteeism has revolved around strategies to strengthen students’ bonds to peers and trusted adults while using student and family feedback as a guide.

“We believe the relationship is the intervention,” said Laura Allen, the director of the 28,000-student district’s whole-child department , the hub for much of the school system’s student-wellness work.

With a grant from Washington’s state education agency, Tacoma two years ago hired a district attendance and engagement counselor to lead work on boosting attendance. As part of that work, the district surveyed students and families to find out why kids attend school and why they miss it.

“The No. 1 reason why kids said they come to school was to see their friends,” Allen said. “It doesn’t mean that they don’t want to do well academically, but that friendship connection was first and foremost.”

With that knowledge in hand, schools worked on creating new clubs that could provide more students opportunities to spend time with friends and foster a sense of belonging.

District data showed that Indigenous and LGBTQ+ students were more likely to attend school irregularly, so staff helped create new affinity groups aimed at giving students from those populations a place to “feel seen and heard,” said Jimmy Gere, the attendance and engagement counselor.

Some schools formed attendance clubs to build connections with students at risk of being chronically absent and work through problems that could keep them from coming to school.

Newly formed building attendance teams—sometimes existing teams that expanded their focus to include attendance—took inventories of their schools’ existing interventions for at-risk students, held listening sessions with students and staff, and took school-specific steps to address attendance challenges.

Tacoma also began working with two community organizations that provide mentors who regularly meet with students during school hours, checking in with them and working with them on social-emotional skills.

These experiences show students that “good things happen at school, whether it’s with your teachers or staff that are there every day or community partners that are set up to deliver their services within the school,” Gere said.

And one new initiative provides younger students with a safe way to get to school while giving older students a paid internship and course credit.

The Walking School Bus is an organized group of students who walk to school together each day, led by a high school student route leader or Tacoma educator, stopping at established points to pick up more students. It was a response to feedback from parents who said their kids didn’t have a safe way to get to school, presenting a barrier to attendance.

Younger students build relationships with high school students, and high school students gain a service-learning opportunity—one of the CDC’s identified strategies for building school connectedness.

“There’s an element of mentorship because elementary kids love high school kids,” Gere said.

Tacoma has seen attendance inch up since it started these initiatives. Average daily attendance has been 88.3 percent so far this year, up from 85.6 percent in 2021-22, before these initiatives began, district data show. But it’s still early, and future funding for some of the work is uncertain as the state attendance grant comes to a close alongside other federal COVID-relief money.

Still, Tacoma will be able to carry on much of the work based on building connections, Allen said. For students, she said, “it is all about making sure that they know that they’re seen and that they’re loved.”

VIDEO: How Schools Can Harness the Power of Relationships

Coverage of whole-child approaches to learning is supported in part by a grant from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, at www.chanzuckerberg.com . Education Week retains sole editorial control over the content of this coverage. A version of this article appeared in the April 24, 2024 edition of Education Week as 4 Case Studies: Schools Use Connections to Give Every Student a Reason to Attend

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Prepare your students to navigate business challenges by immersing them in real-world scenarios.

Transform business education

Bring excitement into your classroom with engaging case discussions and introduce students to the challenge and fun of making important decisions.

Illustrate business concepts

Help students learn by doing with over 50,000+ cases featuring real-world business scenarios spanning across multiple areas of business.

Encourage new ways of thinking

Student build confidence and critical thinking skills while learning to express their ideas and convince others, setting them up for success in the real world.

Explore Different Types of Cases

Find cases that meet your particular needs.

New! Quick Cases

Quickly immerse students in focused and engaging business dilemmas. No student prep time required.

Traditional cases from HBS and 50+ leading business schools.

Multimedia Cases

Cases that keep students engaged with video, audio, and interactive components.

Search Cases in Your Discipline

Select a discipline and start browsing available cases.

- Business & Government Relations

- Business Ethics

- Entrepreneurship

- General Management

- Human Resource Management

- Information Technology

- International Business

- Negotiation

- Operations Management

- Organizational Behavior

- Service Management

- Social Enterprise

Case Teaching Seminar

Register now for our Teaching with Cases Seminar at Harvard Business School, held June 21 - 22 . Learn how to lead case discussions like a pro and earn a certificate from Harvard Business Publishing.

Fundamentals of Case Teaching

Our new, self-paced, online course guides you through the fundamentals for leading successful case discussions at any course level.

Case Companion: Build Students’ Confidence in Case Analysis

Case Companion is an engaging and interactive introduction to case study analysis that is ideal for undergraduates or any student new to learning with cases.

Discover Trending Cases

Stay up to date on cases from leading business schools.

Discover new ideas for your courses

Course Explorer lets you browse learning materials by topic, curated by our editors, partners, and faculty from leading business schools.

Teach with Cases

Explore resources designed to help you bring the case method into your classroom.

Inspiring Minds Articles on Case Teaching

Insights from leading educators about teaching with the case method.

Book: Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide

A book featuring practical advice for instructors on managing class discussion to maximize learning.

Webinar: How ChatGPT and Other AI Tools Can Maximize the Learning Potential of Your Case-Based Classes

Register now.

Supplements: Inside the Case

Teaching tips and insights from case authors.

Guide: Teaching Cases Online

A guide for experienced educators who are new to online case teaching.

Educator Training: Selecting Cases to Use in Your Classes

Find the right materials to achieve your learning goals.

Educator Training: Teaching with Cases

Key strategies and practical advice for engaging students using the case method.

Frequently Asked Questions

What support can I offer my students around analyzing cases and preparing for discussion?

Case discussions can be a big departure from the norm for students who are used to lecture-based classes. The Case Analysis Coach is an interactive tutorial on reading and analyzing a case study. The Case Study Handbook covers key skills students need to read, understand, discuss and write about cases. The Case Study Handbook is also available as individual chapters to help your students focus on specific skills.

How can I transfer my in-person case teaching plan to an online environment?

The case method can be used in an online environment without sacrificing its benefits. We have compiled a few resources to help you create transformative online learning experiences with the case method. Learn how HBS brought the case method online in this podcast , gather some quick guidance from the article " How to Teach Any Case Online ", review the Teaching Cases Online Guide for a deep dive, and check out our Teaching Online Resources Page for more insights and inspiration.

After 35 years as an academic, I have come to the conclusion that there is a magic in the way Harvard cases are written. Cases go from specific to general, to show students that business situations are amenable to hard headed analysis that then generalize to larger theoretical insights. The students love it! Akshay Rao Professor, General Mills Chair in Marketing at the University of Minnesota

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

The Center for Global Studies

Sample case studies, page table of contents, case study #1.

Sophia A. McClennen

Cultural Connections for Younger Students: A Party for a Japanese Refugee

On Friday, March 11, 2011 an earthquake hit Japan and caused a series of Tsunami waves. It was the largest earthquake in the history of Japan and it caused a lot of damage. Homes were lost, people were hurt, and many had to find other places to stay since the places where they lived were no longer safe. Some Japanese families even had to move to other countries, at least temporarily. Your teacher has just told you that a little girl from Japan will be coming soon to join your class at your school. Her name is Bachiko, which means “happy child” in Japanese. She is moving to State College with her parents and younger brother.

Your teacher tells you that the first day she will be in class will be May 5. In Japan May 5 is children’s day and the whole country celebrates children and their mothers. But for Bachiko May 5 is even more special since it is also her birthday. Since she will be here the class thinks that you should all plan a celebration for her. She won’t know anyone here yet. She won’t have any friends yet. And, even though she speaks some English, she is more comfortable speaking Japanese. You want to help her celebrate Children’s Day and her birthday and you also want to help her feel welcome since she will probably be missing her home very much. You want to make sure that the party includes some of the sorts of things that kids do in Japan. How can you plan the party? How can you help her celebrate her special day?

Global Knowledge/Global Empathy:

Asking the right questions:.

Begin by asking questions that help your students connect with Bachiko’s story. Ask them to think of holidays they celebrate that they would miss if they had to go to a different country during that time of year.

Ask them to think of how they would feel if they had to be far from home for their birthday. What sorts of things would they miss? What sorts of things would they be able to do in a new place?

Adjusting the conversation based on the maturity of the class, talk about the challenges to Bachiko of having to move to a new place. Ask them about what they think of moving and what sorts of challenges moving brings—compare moving to another place in the country where you currently live to moving to a new country.

Talk about natural disasters. Ask them if there are times when they feel scared of them and discuss ways for them to reduce their fears. Talk about how they happen all over the globe. Make sure not to let them think that they only happen in places like Japan.

Gathering information:

Brainstorm with the class the sort of information they need in order to plan the party (solve the problem). Create a list of things that the class needs to learn to be able to do this.

Create a list of things that the kids need to learn about Japanese culture. Ask the kids to think of any Japanese culture that they already know of (sushi, animation, pokemon, origami, etc.). Ask them to consider whether their experience of these cultural items might be different from how Bachiko and her friends experience them.

Depending on the class—consider teaching more about earthquakes, tsunamis, and other natural disasters. Use this as a chance to balance learning about sciences with learning compassion for those that are affected by these events. Consider talking about Katrina or other US natural disasters (tornadoes) so that they don’t think these things only happen to others.

Imagining a way to address the problem:

Once you have begun to gather materials and information that can help the class imagine the party that they would like to throw, have them begin to describe what they want to do for the party. Do they need to make origami, kites, etc? What foods? Music? What other activities? Help them imagine all of these things.

Then ask them to imagine the party and think of how they would like to tell a story about it. Asking them to be the storytellers of this will help encourage their imagination and empathy. (While possibly throwing the party would be a fun idea—it might not be the best learning activity and could be difficult to do). Do they want to write a story about Bachiko and the party? Do they want to create a cartoon/animated version? Do they want to make a series of pictures? Consider whether you want them to work in groups or individually or in some combination. Group work is generally helpful for these types of projects. Maybe you make a few groups and let each one decide between a story, pictures, an origami play, etc… There are lots of options.

When the students have their projects complete have them present them to the class. Then have the whole class talk about the strengths and weaknesses of their projects. What do they think Bachiko would have liked most? What might have been hard for her? What parts were fun for them to plan? What parts were hard? The idea here is to make it clear that they have done good work, that they imagined a way to help someone else, but that it would not be possible to “fix” the situation. Bachiko would surely be a bit sad—but their party would also surely really help. And the more the party made her feel welcome, the more of a success it would be.

Next ask the class to engage in some sort of fundraising or other project to help the kids in Japan. Now, when they do this, they will feel much more connected to the communities they are trying to help.

Assessment:

There should always be some assessment with these projects. It is possible to determine how well students gathered information, whether they asked good questions, and whether they could appreciate the limits to their work as well as its strengths.

Asks students to imagine a direct connection with a young Japanese earthquake victim—which creates a greater link. Makes the crisis in Japan more real.

Asks them to imagine themselves in a similar situation—this will deter othering (the idea that this situation would only happen to others).

Gives them an opportunity to learn more about Japan through their own interest in solving a problem.

Risks making them feel sorry for Bachiko in a way that might make her seem helpless. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency.

Risks developing a negative stereotype of Japan—since it could seem like a country that suffers disasters and needs our help. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency by not allowing them to describe Japan in negative terms.

Adaptations:

This case study could be adjusted to describe a child from almost any other nation that had to suddenly move to your school district. The possibilities are limitless.

Web resources:

- Teaching Kids About Earthquakes, Tsunamis, and Japan Through Online Resources

- Talking to kids about the Earthquake

- The Science of Earthquakes (for kids)

- Kids web Japan

- Japan for kids

Case Study #2

Environmental connections for middle school age students: global sustainability and the brazilian amazon.

Your name is Jorge, you are 13, and you are from Brazil. You live in the Amazon in a community of Seringueiros— Seringueiro is the Portuguese word for “rubber tapper.” Rubber tapping has been a traditional way of life for many people living in the Amazon forest since the start of the century. A cut is made in the side of a rubber tree then the rubber is harvested. Later the tree heals and the rubber tapper sells the rubber to buy things they need. Life as a seringueiro is not easy. It is difficult to make money selling the rubber and many in these communities struggle to make a good life. Lately, though, it has gotten worse.

Jorge’s family and his community have just learned that a logging company plans to cut down the trees that they use to get rubber. Jorge’s parents are tired of fighting the logging company and they are thinking of moving to the city. But Jorge has heard stories that life in the city would be even harder for them and he doesn’t want to leave the forest. Instead, he wants to think of a way to protect the trees that his family needs for rubber. He wants to work to find a way to allow his community to continue living in harmony with nature. He thinks that he will hate living in the city and he wants to continue living in the ways that his community has for decades.

Jorge realizes that saving the trees for rubber tappers probably won’t convince the Brazilian government to protect them. Native Americans throughout the hemisphere have seen their lands taken away and their way of life threatened for centuries—and very few people have come to their defense. But he thinks that maybe he can get attention to saving his community’s trees if he reminds the public of the importance of the plant life in the Amazon. He also thinks that he has a greater chance of getting attention to his community’s problem if he links with other kids his age from other parts of the world.

He thinks that if they work together they can make a difference. He thinks that if kids from various places draw attention to this problem, and if he gets help from environmentalists, he can convince the Brazilian government to protect the lands.

The Amazon rainforest is one of the world’s greatest natural resources. Its many plants recycle carbon dioxide into oxygen, and some call it “Lungs of our Planet” since 20% of earth oxygen is produced by the Amazon rainforest. Even though environmentalists and government policies forced the world to give more attention to the rain forest, deforestation continues to be a major problem. Predications show that if nothing is done to stop the destruction of rainforest that half our remaining rain forests will be gone by the year 2025 and by 2060 there will be no rain forests remaining.

Not only does the Amazon provide oxygen, it is the home to a great variety of plant life that holds the potential to help solve many medical problems. Protecting this biodiversity is also of great importance. The plants in the Amazon could help us discover the next cure for cancer or for other diseases. The oxygen produced in the Amazon helps people all over the world to breathe.

Put yourself in the place of Jorge and imagine how he might solve this problem. How can he get help protecting the trees his family needs? Should he start an environmental activism campaign? How could

he do that? He will need to connect with others outside his community. Could you imagine ways that your own school might help him? Design a strategy to help Jorge protect the rainforest.

Begin by asking questions that help your students connect with Jorge’s story. Ask them to think of what they would do if a company was taking over the lands they lived on.

Ask them to think about the value of protecting traditional ways of life. Does their family have traditions that sometimes seem threatened based on the way that society has changed? And how are their experiences related to those of Jorge, whose community has a very traditional way of living? Does Jorge have a right to have that way of life protected? Do we have an obligation to help protect it?

Ask them to think about how hard it will be for Jorge to get attention to his cause. What are the challenges he faces? How can Jorge connect his cause to the lives of people living outside the rain forest? The rainforest is important to everyone’s heath—but few people know that or care. How can that change?

Talk about environmental issues. Ask them about what they do to help conserve the planet’s resources. Ask them to think about how environmental issues link people across the globe. Ask them to think about the sorts of communities that tend to be most threatened by things like deforestation. Are their problems exacerbated by having a less publicly recognized voice? Also ask them to think about how hard it is to get people to change the way that they live—even when they know that some of their habits are bad for the planet.

Talk about sustainability. Jorge’s community as a sustainable connection to the land. It does not take in a way that causes damage or limits regeneration. What are some ways that our students can live a sustainable life? How can we learn from communities like Jorge’s? What gets lost if those communities cease to exist?

Brainstorm with the class the sort of information they need in order to help Jorge. They need to learn about rubber tapping, the Amazon, deforestation, environmental activism, sustainability. Create a list of things that the class needs to learn to be able to do this.

Create a list of things that the kids need to learn about Brazilian Native American culture. Ask them to think of things that they know about Native Americans in the United States and then ask them to think of way that these communities face similar challenges across the Americas.

Ask them to think about how the crisis in the Amazon links to environmental crises in the United States. Do they know about the Marellus Shale story? How might that story be similar to that of Jorge’s?

Once you have begun to gather materials and information that can help the class imagine Jorge’s situation, have them begin to describe a plan for Jorge. How can Jorge gain support? He can’t do it alone—so who would be good to help him? What sorts of information does he need to present to get supporters for this? How can he best connect with people outside of his community? Help them imagine all of these things.

Next have them implement a campaign to save the rainforest where Jorge lives. Consider whether you want them to work in groups or individually or in some combination. Group work is generally helpful for these types of projects. Do they want to do posters, hold events, make a movie, write a book, get articles in newspapers, host a website, etc….? How can they best get attention for the cause? There are lots of options.

When the students have their project concepts complete have them present them to the class. They do not need to actually make the posters, websites, etc…they just need to describe them and create an example. Then have the whole class talk about the strengths and weaknesses of their projects. What parts of Jorge’s action plan were fun for them to work on? What parts were hard? The idea here is to make it clear that they have done good work, that they imagined a way to help someone else, but that it would not be possible to “fix” the situation.

The class should then discuss the merits of each of the ideas that the teams came up with –and they could follow through on creating some resources that exemplified some of the approaches the class thought worked best.

Next ask the class to engage in some sort of project to raise awareness for an environmental issue—especially one linked to protecting forests. Ask them to consider a project to advance sustainable living.

Asks students to imagine a direct connection with a Brazilian Native American—which creates a greater link. Makes the social and environmental crisis more real.

Asks them to imagine themselves in a similar situation—this will deter othering.

Gives them an opportunity to learn more about the Amazon and Brazilians through their own interest in solving a problem.

Risks making them feel sorry for Jorge in a way that might make him seem helpless. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency.

Risks developing a negative stereotype of Brazil—since it could seem like the Brazilian government doesn’t care about the Amazon or the rubber tappers. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency by not allowing them to describe Brazil in negative terms and by reminding them of how this problem has global examples.

This case study could be adjusted to describe an environmental conflict from another region. The possibilities are limitless.

- Amazon rubber tappers news

- Amazon rainforest

Case Study #3

The impact of war on children for high school age students: landmines in angola.

Mia is 16 years old and she is from Angola. Last week her brother, Nelson, was playing soccer with friends when he chased after the ball and went on lands that they are warned never to step on. He was too busy chasing the ball to pay attention to the rule. As he crossed over into the dangerous territory he heard a click, then an explosion. He had stepped on a land mine. He was rushed to a hospital where Mia and her family went to see him. Once they arrived they learned that Nelson had lost both legs in the explosion. Nelson is now one of the more than 100,000 Angolans who have lost a limb to landmines.

Angola suffered a civil war that ended in 1994, but, even though the war ended that year, the effects of it are still in place. There are estimates of between 10 and 20 landmines in Angola which is equal to approximately 1-2 landmines per inhabitant. As mentioned, over 100,000 Angolans have lost a limb due to a landmine and 120 Angolans die from a landmine explosion every month. But the negative effects of landmines on the population go beyond injuries: the threat of landmines restricts the ability of people to move about their country, to farm, to find clean water, to go to school, and –as in Nelson’s case—to play games like soccer. Women and children are most threatened by landmines and children represent 49% of the landmine injuries in Angola. During the Soviet war in Afghanistan during the 1980s the Soviets used landmines that looked to children like toys. Many were killed trying to pick them up. Even though the UN passed a moratorium on landmines in 1993, there is still no international consensus on banning the use of landmines. Currently there are 20 mines laid for each one removed.

Landmines only cost about $3 to make, but they cost about $1,000 each to remove. Mia has watched her community suffer life with landmines for too long. She wants to work to change this problem, but she realizes that the cost of removing landmines is very high. She knows that anti-landmine groups help to de-mine areas, but she doesn’t want to wait for help from others, she thinks her community needs to learn more about how to de-mine. She has another problem, too, she has learned that landmines continue to be used and she wants to work to stop the use of landmines in other countries. There are over 110 million landmines (and millions of other explosive devices) in 68 nations today. She wants to work to stop the future placement of more mines.

Put yourself in the place of Mia and imagine how she might solve this problem. How can she get help de-mining her community? Should she attempt to get de-miners to her area or she should work to see if some of the members of her community could learn de-mining techniques? How could she do that? She also wants to raise awareness about landmines globally so that this practice can stop. Can you imagine a project with your school that could help her in that goal? Design a strategy to help Mia stop landmine damage.

Begin by asking questions that help students connect with Mia’s story. Ask them to think of what they would do if a sibling or cousin or friend was hurt in this way.

Ask them to think about the impact of war on children. The case of landmines is a clear example of how current military techniques often target civilian populations and they do so through devices that can be left and that do not require military personnel to maintain. How has that changed the nature of war? Should there be a ban on landmines? What would be some good ways to advance this cause? It might be useful to review the Geneva Conventions with students since they are war guidelines that create protections for civilians.

A further issue is the way that the landmines cause Mia’s community to depend on others. De- mining is complex work and it takes a lot of training. Most of the time de-mining crews will come to a community, work, then leave. What are the challenges to changing that process and giving more local communities these skills and the equipment needed to perform them safely? Similarly some believe that the 12 nations that participated in Angola’s Civil War by providing the mines should also be responsible for getting rid of them. Who should get rid of the mines? What are some ways that the community can be an active part of this process?

Ask students to think about how hard it will be for Mia to get attention to her cause. What are the challenges she faces? How can Mia connect her cause to the lives of people living outside of Angola or Africa? What would it take to get people living in the United States to care about Mia’s situation? The US is home to more than 15 landmine producers. Should efforts be made to shut down their operations?

Ask them to think about the long term effects of war on communities. A number of nations in the world have been engaged in long term conflicts, with children that have lived their whole lives during military conflict. How does that influence the lives of children? How does that affect a community’s ability to prosper? What will happen to kids like Nelson as they grow up?

Brainstorm with the class the sort of information they need in order to help Mia. They need to learn about landmines, the politics of de-mining, the current efforts to ban landmines, and the human rights of children in a time of war. Create a list of things that the class needs to learn to be able to do this.

Create a list of things that the students need to learn about Angolan society and history. In order to appreciate Mia’s situation it is important that students empathize with her without seeing her as a helpless victim. What happened during the Civil War? Why did the United States and the Soviet Union get involved? How was their involvement a result of Cold War dynamics? Teach students about the idea of proxy wars and ask them to think about the political implications such wars have on the nations where the wars are waged.

Ask them to think about how the landmine crisis is a geopolitical problem that is not just limited to Angola. Have the class learn about the use of landmines in other countries and ask them to think about how landmines play a role in contemporary military conflicts.

Once you have begun to gather materials and information that can help the class imagine Mia’s situation, have them begin to describe a plan for Mia. How can Mia gain support? How can Mia

help her community and get help? She can’t do it alone—so who would be good to help her? What sorts of information does she need to present to get supporters for her cause? How can she best connect with people outside of her community? Help them imagine all of these things.

Next have them implement a campaign to get resources to de-mine the area where Mia lives and/or to assist the international anti-landmine project. Consider whether you want them to work in groups or individually or in some combination. Group work is generally helpful for these types of projects. Do they want to do posters, hold events, make a movie, write a book, get articles in newspapers, host a website, etc….? How can they best get attention for the cause?

There are lots of options.

When the students have their project concepts complete have them present them to the class. They do not need to actually make the posters, websites, etc…they just need to describe them, include examples, and possibly write up a report. The amount of actual materials they provide can be adjusted based on time and resources.

Then have the whole class talk about the strengths and weaknesses of their projects. What parts of Mia’s action plan were easier to solve? What parts were harder? The idea here is to make it clear that they have done good work, that they imagined a way to help someone else, but that it would not be possible to “fix” the situation. Nelson won’t get his legs back, but possibly this project could save another boy.

The class should then discuss the merits of each of the ideas that the teams came up with –and they could follow through on creating some resources that exemplified some of the approaches the class thought worked best. Having open conversations with the class about the pros and cons of each project teaches students to appreciate that complex problems require complex solutions.

Next ask the class to engage in some sort of project to raise awareness of the damages caused by landmines. Ask them to consider a project to advance efforts to ban landmines and/or to support de-mining in Angola.

Asks students to imagine a direct connection with an Angolan—which creates a greater link. Makes the social and political crisis more real.

Gives them an opportunity to learn more about landmines, the effects of war on children, and Angola through their own interest in solving a problem.

Teaches them to appreciate the complexity of these types of problems and the fact that they do not have easy solutions. Teaches them that it is important to work to solve problems even when these can’t be easily fixed.

Risks making them feel sorry for Mia and Nelson in a way that might make them seem helpless. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency.

Risks developing a negative stereotype of Angola—since the history of the prolonged Civil War could make it seem like Angola is not capable of peaceful rule. You can teach in ways that confront this tendency by not allowing them to describe Angola in negative terms and by reminding them of how the Civil War was not simply fought by Angolans: it was indicative of Cold War struggles and the legacy of Angola’s history as a colony of Portugal.

This case study could be adjusted to describe a military conflict from another region—the key is to focus on the effects to children of war, since that link is likely to draw more empathy. There are many possibilities.

- Angola’s landmines

- Landmines a deadly inheritance

- BBC: Angola’s Landmine legacy

- International Campaign to Ban Landmines

- Effects on Children of Landmines

Teaching Civics

- Find Lessons

- Professional Development

- Super Civics: Elementary Toolbox of Civics Lessons

- Project Citizen

- Minnesota Civics Test

- Minnesota Civic Education Coalition

- Minnesota We the People: The Citizen and the Constitution

- Deliberating in a Democracy

- Civic Education Resources

- Civically Speaking

- Super Civics Summer Institute 2024

- Search Teaching Civics

Constitution 101 Curriculum: High School Level

From The National Constitution Center “Constitution 101 is a 15-unit asynchronous, semester-long curriculum that provides students with a basic understanding of the Constitution’s text, history, Read More

ABA Supreme Court PREVIEW – Featured Cases 2020-2021

Scroll down to “Past Cases” to find modified case studies and focus questions for classroom use. Featured Cases from the Supreme Court’s 2020-2021 session- Caniglia Read More

ABA Supreme Court PREVIEW – Featured Cases 2019-2020

Scroll down to “Past Cases” to find modified case studies and focus questions for classroom use. Featured Cases from the Supreme Court’s 2019-2020 session- McGirt Read More

Super Civics Toolbox

The Super Civics Toolbox is a collection of lessons aligned to the Minnesota K-8 Citizenship and Government standards (2011). Super Civics Toolbox For video instructions on how Read More

Advanced Placement Supreme Court Cases organized by Era of History

Useful for studying/review, or Each One Teach One, Texas Law-Related Education provides summaries of select landmark Supreme Court Cases from the Early Republic to Contemporary America.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966) -iCivics

From iCivics’ Landmark Library Students will: Describe the 5th Amendment right to silence and the 6th Amendment right to a lawyer. Identify the main arguments put forth Read More

Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) – iCivics

From iCivics’ Landmark Library This mini-lesson covers the basics of the Supreme Court’s decision that it was constitutional to keep black and white people segregated as Read More

ABA Supreme Court PREVIEW – Featured Cases 2018-2019

Scroll down to “Past Cases” to find modified case studies and focus questions for classroom use. Featured Cases from the Supreme Court’s 2018-2019 session - Read More

Political Gerrymandering Explained

What is political gerrymandering? Infographic with text. Also see: Rucho v. Common Cause and Lamone v. Benison (https://www.subscriptlaw.com/blog/rucho-v-commo-cause-and-lamone-v-benisek)

Infographic Coverage of the Supreme Court

These one-page graphics with minimal text, introduce complex legal concepts in an accessible way. Coverage goes back to the Supreme Court’s 2017-2018 term.

Case Study – Rucho v. Common Cause

In 2016, a federal court ordered North Carolina to redraw its congressional districts because the existing map was unconstitutional because it included districts that were racially Read More

Symbols – C3 Teachers

From C3 Teachers: College Career & Civic Life Compelling Question: “What symbol best represents the United States?” Students investigate what each American symbol represents, how we Read More

How to Read a U.S. Supreme Court Opinion

Insights on Law & Society 13.1, Fall 2012 A basic guide for reading a U.S. Supreme Court opinion. See pages 10 – 11.

Miranda v. Arizona (Quimbee video)

Does the Fifth (5th) Amendment’s protection against self-incrimination extend to the police interrogation of a suspect? A 5 minute video case brief of Miranda v. Read More

Wickard v. Filburn (Quimbee video)

Wickard v. Filburn (1942) was a landmark decision in which the Supreme Court interpreted Congress’s Commerce Clause authority to reach purely in-state activities using the Aggregation Doctrine. Overview video (3:28): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UGZIAf_-Ckw

Search Me: Understanding the Fourth Amendment

by Catherine Hawke Students will examine definitions and interpretations of the Fourth (4th) Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, read about and discuss the role of the Read More

10 Supreme Court Cases Every Teen Should Know

By Tom Jacobs, From The Learning Network “In a landmark 1967 case known as In re Gault (“in re” is Latin for “in reference to”), Read More

Civics 101 – IRL1: Free Speech in Schools

Each podcast episode of Civics 101 gives listeners a basic, non-partisan, topical reintroduction to how the U.S. government works. The Civics 101 IRL installments dive into the Read More

Civics 101 video: John and Mary Beth Tinker

New Hampshire Public Radio Go to : Civics 101 video (6:47)- John and Mary Beth Tinker (Tinker v Des Moines): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YeK9t8uMXTY “John and Mary Beth Tinker Read More

Elonis v. U.S. – Artistic Expression or Serious Threat?

Office of the U.S. Courts – Educational Resources This First Amendment activity applies the landmark Supreme Court case Elonis v. U.S. to a teen conflict Read More

Street Law Resource Library

Street Law has compiled hundreds of teaching activities and methods, case summaries, mock trials, and articles—many of which are free—and organized them by topic, audience, and Read More

Prohibition – Episode 1: A Nation of Drunkards

“PROHIBITION is a three-part, five-and-a-half-hour documentary film series directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that tells the story of the rise, rule, and fall Read More

Photo Ethics: A Photograph’s Integrity

From NewseumED “This case study explores a photojournalist’s ethical duty to be fair, accurate and clear, specifically in regard to manipulating photographs.” Divide students into small groups. Read More

Tracking the Transformative Fourteenth Amendment

By JoEllen Ambrose - Insights on Law & Society 17.2, Winter 2017 DURATION: One class period for speaking strategy and research; one class period for role-play Read More

Lesson Plan: 2016-2017 Supreme Court Oral Arguments

From C-Span Classroom As a class, students watch a brief video (7:42) of Supreme Court Justices explaining the process and importance of oral arguments during Read More

A Quick Guide to Libel Law

What is libel law? How does it work? Are newspapers “totally protected” from lawsuits? Can libel laws be “opened up”? Is freedom of the press Read More

Leaks and the Media

by Lata Nott, Executive Director, First Amendment Center This primer’s interactive graphics and visual aids addresses the questions: What is a leak? Is leaking illegal? Read More

Yick Wo and the Equal Protection Clause

From Annenberg Classroom “This documentary examines the case Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886) in which the Supreme Court held that noncitizens have due process rights Read More

Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) – iCivics

From iCivics’ Landmark Library This mini-lesson covers the basics of the Supreme Court’s decision that gave defendants in state criminal courts the right to a lawyer. Read More

Marbury v. Madison (1803) -iCivics

From iCivics’ Landmark Library Students will: Define “judicial review” and describe its importance. Identify the main arguments put forth in the case. Describe the Supreme Court’s Read More

Korematsu v. United States (1944) -iCivics

From iCivics’ Landmark Library After a brief reading, students use a word bank to complete President Reagan’s apology to Japanese Americans who were interned during World Read More

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) -iCivics

From iCivics’ Landmark Library Students will: Describe the Commerce Clause and the Supremacy Clause, and their effect Identify the main arguments put forth in the case. Read More

Texas v. Johnson (1989) -iCivics