MERRIMACK COLLEGE MCQUADE LIBRARY

Social justice.

- Open Educational Resources (OER)

- Get Started

- Reference Sources

- Developing a Research Question

- Find Books / E-books / DVDs

- Find Articles

- Find Images / Art

- Find Videos / Film

- Database Search Strategies

- Types of Resources

Writing a Literature Review (University Library, UC Santa Cruz)

"the literature" and "the review" (virginia commonwealth university).

- Evaluate Sources

- Cite Sources

- Annotated Bibliography

- SJ Websites

- SJ Organizations

- Government Resources

Additional Online Resources

- How to: Literature reviews The Writing Center, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill

- The Literature Review A basic overview of the literature review process. (Courtesy of Virginia Commonwealth University)

- The Process: Search, Assess, Summarize, Synthesize Getting Started: Assessing Sources/Creating a Matrix/Writing a Literature Review (Courtesy of Virginia Commonwealth University)

- Review of Literature The Writing Center @ Univeristy of Wisconsin - Madison

- Tools for Preparing Literature Reviews George Washington University

- Write a Literature Review University Library, UC Santa Cruz

Your SJ Librarian

1. Introduction

Not to be confused with a book review, a literature review surveys scholarly articles, books and other sources (e.g. dissertations, conference proceedings) relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, providing a description, summary, and critical evaluation of each work. The purpose is to offer an overview of significant literature published on a topic.

2. Components

Similar to primary research, development of the literature review requires four stages:

- Problem formulation—which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues?

- Literature search—finding materials relevant to the subject being explored

- Data evaluation—determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic

- Analysis and interpretation—discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature

Literature reviews should comprise the following elements:

- An overview of the subject, issue or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review

- Division of works under review into categories (e.g. those in support of a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative theses entirely)

- Explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research

In assessing each piece, consideration should be given to:

- Provenance—What are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence (e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings)?

- Objectivity—Is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness—Which of the author's theses are most/least convincing?

- Value—Are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

3. Definition and Use/Purpose

A literature review may constitute an essential chapter of a thesis or dissertation, or may be a self-contained review of writings on a subject. In either case, its purpose is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to the understanding of the subject under review

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration

- Identify new ways to interpret, and shed light on any gaps in, previous research

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort

- Point the way forward for further research

- Place one's original work (in the case of theses or dissertations) in the context of existing literature

The literature review itself, however, does not present new primary scholarship.

- << Previous: Types of Resources

- Next: Evaluate Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 9, 2024 12:15 PM

- URL: https://libguides.merrimack.edu/SocialJustice

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- About Social Work

- About the National Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Guiding organizations and social justice.

- < Previous

Social Work and Social Justice: A Conceptual Review

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Brittanie E Atteberry-Ash, Social Work and Social Justice: A Conceptual Review, Social Work , Volume 68, Issue 1, January 2023, Pages 38–46, https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swac042

- Permissions Icon Permissions

As a profession, social work has codified within its ethical guidance and educational policies a commitment to social justice. While a commitment to social justice is asserted in several of our profession’s guiding documents, social work continues to lack consensus on both the meaning and merit of social justice, resulting is disparate and sometimes discriminatory practice even under a “social justice” label. This study examines how social justice has been operationalized in social work via a conceptual review of the literature. Findings show that social work leans heavily on John Rawls’s definition of social justice, Martha Nussbaum’s and Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach, and the definition of social justice included in The Social Work Dictionary . Unfortunately, none of these adequately align with the National Association of Social Workers’ Code of Ethics , which drives the profession. This conceptual review is a call to social workers to join together in defining the guiding principle of the profession.

The commitment to social justice is codified within the ethical guidance and educational policies of the profession of social work. While the concept of social justice is enumerated in several guiding documents, social work continues to lack consensus on both the meaning and merit of social justice ( Abramovitz, 1993 ; Funge, 2011 ; Garcia & Van Soest, 2006 ; Hong & Hodge, 2009 ; Specht & Courtney, 1995 ; Van Soest & Garcia, 2003 ), impeding how effectively social work has been able to enact social justice in practice ( Reisch, 2010 ).

Guided primarily by two organizations in the United States—the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) and the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE)—social workers are called on to practice socially just values and to address the consequences of oppression, specifically lost opportunity, social disenfranchisement, and isolation. NASW does this through the establishment and monitoring of licensure for practitioners and through maintaining the discipline’s Code of Ethics ( NASW, 2021 ), which states, “Social workers promote social justice and social change with and on behalf of clients” (p. 1). Further, social justice is identified as one of NASW’s core values of the profession of social work.

CSWE guides educational practices and policy through membership and the accreditation of programs of social work through the Council on Accreditation. The CSWE Education Policy and Accreditation Standards (EPAS) identify the purpose of social work as promoting personal and community well-being, actualized through the quest for social and economic justice, the prevention of conditions that limit human rights, the elimination of poverty, and the enhancement of the quality of life for all persons, locally and globally ( CSWE, 2022 ).

In 2013, paralleling a similar process in numerous disciplines, the American Academy of Social Work and Social Welfare sought national input from the field to identify critical, compelling issues that were measurable. The 12 Grand Challenges for Society that emerged from this process were meant to inspire researchers and practitioners, to focus attention, and to drive innovation and collaboration in the profession. Among these challenges is the call to achieve equal opportunity and justice—yet another restatement of the centrality of social justice to the field ( Uehara et al., 2013 ).

is a practice-based profession and an academic discipline that promotes social change and development, social cohesion, and the empowerment and liberation of people. Principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility and respect for diversities are central to social work. ( IFSW, 2014 , Global Definition of the Social Work Profession)

National Association of Social Workers and Social Justice

The first NASW Code of Ethics appeared in 1960, with no mention of social justice; however, in 1967 , a new principle was added, which created a pledge to nondiscrimination, although with no specific mention of social justice ( NASW, 1960 ). The language of social justice was added in 1979, under “Social Worker’s Ethical Responsibility to Society” ( NASW, 1979 ). Social justice then moved to the forefront. Starting with the 1996 update, the term appears in the preamble and as a value, with an accompanying ethical principle calling for social workers to challenge injustice, and in ethical standards 6.01 and 6.04 ( NASW, 1996 , 1999 , 2008 , 2017 , 2021 ). Currently, the NASW preamble states that social work’s mission is to “enhance human well-being,” assist in meeting the “needs of all people,” and promote social justice and social change. The preamble specifically states that social workers must “strive to end discrimination, oppression, poverty, and other forms of social injustice’ ( NASW, 2021 , p. 1). The Code of Ethics , which is broken up into Ethical Principles and Ethical Standards, ensures that social work stays grounded in its mission, provides a guide to reference back to and rely on, and acts as an accountability measure to both the field and individual social workers ( NASW, 2021 , p. 2). The second of the six ethical principles expresses the value of social justice by articulating that social workers are called to challenge injustice. More specifically, principle 2 affirms that social workers’ change efforts (e.g., advocacy, community organizing, and individual work with clients) are to focus on ending discrimination and other forms of social injustice ( NASW, 2021 , p. 5). The third principle calls on social workers to value the dignity and worth of the person, and states that social workers should actively consider individual differences and cultural and ethnic diversity and treat each person with care and respect. Last, ethical standard 4, social workers’ ethical responsibilities as professionals, includes section 4.02, discrimination, which suggests that social workers should not discriminate “on the basis of race, ethnicity, national origin, color, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, age, marital status, political belief, religion, immigration status, or mental or physical ability” ( NASW, 2021 ).

Implications of the Lack of Consensus in Defining Social Justice

These numerous calls from social work’s guiding organizations to confront injustice and work toward a socially just society distinguish social work from other helping professions, such as psychology or counseling ( American Psychological Association, 2017 ; NASW, 2021 ; Rountree & Pomeroy, 2010 ). Yet, despite this expressed and often repeated link between social work and social justice, as well as the enumeration of the principles of social justice, human rights, collective responsibility, and respect for diversity ( Abramovitz, 1993 ; Funge, 2011 ; NASW, 2021 ; Specht & Courtney, 1995 ), there is no unified understanding of what social justice is, how it is operationalized in social work, or even whether the profession should be driven by it. The term “social justice”—while definitionally complex and lacking consensus in the field ( Finn, 2016 )—has become a buzzword that is often used in everyday conversations, in schools’ mission statements, and by government and community leaders, rarely with a concrete delineation of exactly what the user means. Broadly, social justice is commonly understood as the promotion of social equality by reducing barriers to services and goods. However, social work scholars have concluded that multiple definitions of social justice exist and that it may be a concept that is not well understood or clearly defined ( Longres & Scanlon, 2001 ). Scholars also note that this lack of understanding and consensus on a definition has negatively impacted social work’s ability to address injustice ( Reisch, 2010 ).

Due to the definitional inconsistencies and the lack of agreement within the profession about the centrality of social justice, many educational practices, attitudes, and actions of those working within the profession may not align with socially just ideals that are included in the Code of Ethics and the EPAS ( Longres & Scanlon, 2001 ; Reisch, 2010 ; Specht & Courtney, 1995 ). As academics debate the professionalism of social work, its commitment to its values and ethics, and the role of social justice, social work educators continue to educate students who may neither understand nor connect social justice to their social work practice, despite the guidance provided via the Code of Ethics and the EPAS ( Finn, 2016 ; NASW, 2021 ; Longres & Scanlon, 2001 ). This lack of understanding may also contribute to the perpetuation of injustice by social workers in education settings. Discrimination at the hands of instructors, students, and institutions has been documented in scholarly literature (for a discussion on multiple identities see A. Davis & Mirick, 2022 ; Wong & Jones, 2018 ; for Black faculty see M. Davis, 2021 ; for Black students see Hollingsworth et al., 2018 ; for LGBTQ+ students see Atteberry-Ash et al., 2019 ; Byers et al., 2020 ). These are examples of the stark and dire misalignment between what social work professes and what social workers often practice. There is, additionally, well-documented research showing that individuals with marginalized identities experience discrimination in common social work practitioners’ settings, including in healthcare settings (for multiple identities and experiences of discrimination in healthcare settings see Nong et al., 2020 ; for transgender people and experiences of discrimination in healthcare settings see James et al., 2016 ; for LGBT experiences of discrimination in healthcare see Thorenson, 2018 ).

This disconnect between social justice and how social work operationalizes the value can also be seen in the accrediting body, CSWE, which accredits at least 76 schools of social work (over 10 percent of all schools of social work) that operate in universities that have discriminatory policies directed at LGBTQ+ students. Outside of these specific examples there are large movements within the profession, based on a commitment to social justice, to divest from participation with police systems ( Abrams & Dettlaff, 2020 ; Jacobs et al., 2021 ; Roberts, 2020 ) and child welfare systems ( Dettlaff et al., 2020 ; Roberts, 2020 ), given both of these institutions’ roles in perpetuating oppression, violence, and often unjust practices. These examples of experiences of discrimination within social work education and practices settings, of discriminatory policies, and of movements within the profession may serve as examples of how a disconnect in how we understand social justice and its centrality may impede how we enact social justice in practice ( Reisch, 2010 ).

Social workers may banter about the term “social justice” without actually understanding all that it entails. This lack of connecting concept to practice can cause a myriad of harms to clients and students, who assume that social justice will be practiced in a certain way, but then have different and even discriminatory experiences with social workers. Ergo, I hypothesized that a better understanding of the different ways that the field of social work conceptualizes “social justice” can lay a foundation for a clearer and more unified definition of the term, in turn leading to a more effective and impactful praxis of social justice, both in social work education and in practice.

To understand how social justice is defined in the field of social work, I conducted a conceptual review of the literature. A conceptual review, which is not an exhaustive search of all the literature that exists, seeks to synthesize an area of knowledge as a means of providing a clearer understanding of a concept ( Petticrew & Roberts, 2005 ). It aims to elucidate key ideas, debates, and models of the concept under investigation ( Nutley et al., 2002 ).

Article and Book Selection

To collect relevant articles for review, four databases were searched: ERIC, PsycINFO, Social Services, and Sociological Abstracts. All databases with the exception of PsycINFO (which did not offer that option) used the “anywhere except full text” option with the search terms of “social work*” AND “social justice.” The search was limited to articles written in English that were published between 1996 and 2019. The year 1996 was used because this was the year social justice moved to the forefront of the Code of Ethics .

The initial search of the four databases resulted in 3,245 articles. The results were exported to RefWorks, and the “remove duplicates” option was employed. Manual removal of duplicates ( n = 1,073) resulted in 2,172 abstracts to be reviewed. Abstracts were reviewed for inclusion if they offered a definition of social justice within social work in the United States. Articles were excluded from the full-text review for the following reasons: There was no mention of a social justice definition or social justice as a concept in the abstract ( n = 1,366), the article was not about social work in the United States ( n = 113), the article was not in English ( n = 4), the article was not related to the field social work ( n = 14), the article was a book review ( n = 201), the document was a correction of a previous article ( n = 5), or the article was an introduction to a special edition or was a document in memory of a person ( n = 51). The abstract review resulted in 417 articles to be included in the full-text review. After completion of the full-text review, an additional 315 articles were excluded from the conceptual review: a definition of social justice was not provided ( n = 234), there was no mention of social justice at all ( n = 9), the article was not about social work in the United States ( n = 45), the article was not related to the field of social work ( n = 25), the article was a newly found duplicate ( n = 1), or the article was an introduction to the journal ( n = 1). A total of 102 articles remained for the conceptual review. All articles were downloaded from the institutional library; any article not available was requested via interlibrary loan.

The database WorldCat was used to include books in the conceptual review. Similar to articles, the review focused on books written in English that were published between 1996 and 2019. Additional criteria of nonjuvenile and nonfiction were applied to the WorldCat search criteria.

For books, the initial review resulted in 477 texts. Duplicates were removed ( n = 102), leaving 375 books for abstract/table of contents review. First, if available, abstracts were reviewed. If an abstract was not provided, the table of contents of the book was examined, as often both were provided in the WorldCat search results. Books were excluded from the full-text review for the following reasons: There was no mention of social justice definition or social justice as a concept in the abstract or table of contents ( n = 238), the book was not about social work in the United States ( n = 44), the book was not related to the field of social work ( n = 41), the returned search result was not actually a book ( n = 13), and the return result displayed no description and no description could be found for the title provided ( n = 2). This left 37 books for inclusion in the conceptual review. All books were either downloaded if available electronically or requested from the library. Any book not available was requested via interlibrary loan.

Analysis Process

I conducted this conceptual review over a one-year period, beginning in April 2019, as part of a doctoral dissertation. To examine journal articles, each article was reviewed for its definition of social justice and each mention, along with context, was copied and pasted into an Excel file. Once books were received, they were examined for the inclusion of social justice within the text through both book chapter titles and inclusion in the book index; all relevant chapters or the specific text where social justice appeared were then copied for examination. Once the relevant book pages were copied, they were reviewed for the inclusion of social justice, and each mention, along with context, was then transcribed into the Excel file with the journal article excerpts. Once all identified excerpts were compiled, they were examined for the following: a unique definition of social justice, if a unique definition did exist, whom the article cited in the definition or explanations of social justice (e.g., John Rawls, Amartya Sen, Martha Nussbaum, Robert L. Barker, or another source) was noted. Additionally, I documented if the article mentioned that social justice was not well defined, if social justice was core to the discipline and practice of social work, or if the article mentioned that there was a historical incompatibility between social justice and social work.

Definitions of social justice in the conceptual review relied primarily on three different sources: Rawls (2001) , the capabilities approach ( Nussbaum, 2003 ; Sen, 1992 ), and The Social Work Dictionary ( Barker, 2003 , 2013 ).

Fifty percent ( n = 70) of the literature reviewed used John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice to define or discuss social justice. In social work literature, Rawls’ contributions are twofold: First, social justice is conceptualized as fairness through the distribution of goods (distributive justice) and equal access to basic liberties, including freedom of thought, speech, and assembly, access to participate in the political system, the right to have and maintain personal property, and freedom from unreasonable arrest ( Morgaine & Capous-Desyllas, 2014 ). Second, the focus of distributive justice is on those who are least advantaged in society. Rawls argues that if society is to be equitable, it must benefit those who are the least advantaged, which he defined as those who had the least wealth ( Rawls, 2001 ). A just society as theorized by Rawls (2001) is one where the basic needs of all humans are met, unnecessary stress is minimized, the capability of all people is maximized, and threats to well-being are reduced. Overwhelmingly, the use of Rawls in the social work literature centers on the notion of social justice as distributive justice. Many scholars rely heavily on this conceptualization as it aligns well with social work’s call to meet the basic needs of human beings, and its emphasis on the benefits and well-being of economically disadvantaged people ( NASW, 2021 ; Wakefield, 1998a , 1998b ).

Capabilities Approach

Fifteen percent ( n = 21) of the reviewed articles and texts moved from Rawls’ contribution of distribution of goods to the capabilities approach ( Sen, 1992 ) to social justice, noting the shortcomings of Rawls’s distributive justice conceptualization. The Sen approach moves from a focus on how goods are distributed to the expanded concept of the distribution of capabilities ( Morris, 2002 ). Although the capabilities approach recognizes the importance of societal goods and their distribution, it also acknowledges that Rawls’s theory of justice lacks insight into how a person may be able to use those goods ( Morris, 2002 ). Articles and books reviewed noted that the capabilities approach to justice offers hope in expanding access to opportunity through several modalities, including agency (e.g., people’s ability to pursue goals that they see value in), instrumental freedoms (e.g., political freedom, freedom in accessing economic resources including access to financial credit, freedom to choose education and healthcare, freedom of access to information including financial information to reduce corruption, and freedom to seek protective security including social benefits), substantive freedoms (freedom of speech, freedom to avoid physical harm, freedom to participate in political movements), diversities (this concept relates to equity versus equality, noting for example that pregnant people need more nutrition than nonpregnant people), and health (healthcare should be available to all; Banerjee & Canda, 2012 ). The capabilities approach moves away from fairness as justice in that it also notes that equity, an approach to providing people the tools and resources needed to access opportunity, as opposed to equality, giving everyone the same tools and resources needed to access opportunity, may be a more effective means to justice.

The literature also relied on Nussbaum’s ( n = 12) expansion of Sen’s (1992) capabilities approach and utilized Nussbaum’s explicitly defined 10 capabilities that must be protected to achieve social justice. These 10 capabilities represent what is required to live life with dignity or, in other words, the qualities that must be present for social justice to prevail ( Nussbaum, 2003 ): life; bodily health; bodily integrity; senses, imagination, and thought; emotions; practical reason; affiliation; other species; play; and control over one’s environment. Reviewed literature noted that Nussbaum’s approach to social justice adds, in addition to meeting the basic needs of humans, the connection to social work’s role in impacting well-being, human dignity, and self-determination ( Morris, 2002 ; NASW, 2021 ).

The Social Work Dictionary

an ideal condition in which all members of a society have the same basic rights, protection, opportunities, obligations, and social benefits. Implicit in this concept is the notion that historical inequalities should be acknowledged and remedied through specific measures. A key social work value, social justice entails advocacy to confront discrimination, oppression, and institutional inequities. (pp. 398–399).

This definition is the most closely aligned with the Code of Ethics ( NASW, 2021 ) in that it explicitly recognizes that social justice includes advocacy to address the inequalities that are identified in the guiding documents of the discipline.

Additional Findings

As part of the conceptual review, each article or text was also examined for several indicators (see Table 1 ). Almost 20 percent of the articles offered a unique definition (not mentioning or leaning on concepts by Rawls or Sen) of social justice ( n = 25, 17.9 percent), while almost half mentioned that social justice is ill defined within social work ( n = 62, 44.3 percent). A majority of the articles related social justice back to the Code of Ethics ( n = 94, 67.1 percent), while fewer mentioned that it was core to the profession ( n = 65, 46.4 percent). Last, slightly more than 20 percent ( n = 30) of the texts reviewed mentioned that there is a history of incompatibility or tension between the concept of social justice and the profession of social work.

Social Justice within Social Work

Note: NASW = National Association of Social Workers.

Despite its widespread use within social work, and in line with the existing critiques, social work’s reliance on Rawls’ definition of social justice falls short of the values espoused by the field’s guiding documents. This is especially urgent given Banerjee’s (2011) suggestion that, overwhelmingly, social work has been misusing the interpretation of Rawls’s meaning of social justice due to lack of investigation of the details, the assumptions, and stipulations with Rawls’s conceptualization. Banerjee (2011) notes that Rawls’s view of social justice does not actually align with the primary definitions of social justice in the social work literature.

The findings from this conceptual review suggest that social work scholars most often use Rawls’s theory of social justice from his 1971 text, which he himself updated and critiqued. The most up-to-date version was completed in 2001 (see Rawls, 1971 , 1999 , 2001 ); given this, if social work scholars are to continue to lean on Rawls’s conceptualization of social justice as fairness, they should, at a minimum, be citing and integrating his most current understanding of the concept.

Findings from this review also elucidate that most of the reviewed social work definitions of social justice were missing the crucial role that advocacy plays in the enactment of social justice. Given the common reliance on Rawls, this is not surprising. However, considering the mission and values of social work, the definition that the profession uses necessitates the incorporation of social action. As such, it seems the definition from the 2013 edition of The Social Work Dictionary , which integrates the relationship between social justice and advocacy, is a better choice. Unfortunately, even this definition fails to address the role of personal agency, and to recognize that to best meet the needs of individuals and communities, those individuals and communities need to be central to the advocacy process.

It is also important to recognize that any understanding and definition of social justice is temporally bounded and because the communities, policies, and societal conditions within which social work operates are continuously changing, any agreed upon definition of social justice evolves with those changes. Embodied in any attempt to define and operationalize social justice within social work is the tension between the discipline’s stated goals of liberation and the reality of operating within systems that are inherently structured to maintain the status quo and, thus, the social stratification that we are attempting to eradicate. This tension can be seen, for example, in recent dialogues about exploring reformist and abolitionist approaches in policing (example.g., Jacobs et al., 2021 ; Rine, 2021 ) and the child welfare system (example.g., Dettlaff et al., 2020 ; Herrenkohl et al., 2021 ). While eliminating this tension is likely not possible, it is critical to explicitly acknowledge and understand the implications of these tensions and the resultant outcomes for marginalized peoples.

Even so, given the disparate definitions of social justice that exist currently in the social work literature, a move toward an agreed upon and inclusive definition of the concept of social justice is an important starting point. Next steps toward realization of this goal could be a qualitative study of social justice scholars’ understanding of the findings from this conceptual review, followed by a survey of NASW chapters and CSWE members to determine the degree of agreement around an emerging definition. While the goal of the current study is intentionally limited to the discipline’s body of scholarship, a further additional step would be to engage scholarship from other fields on their definition and operationalization of the construct of social justice. In doing so, increased clarity about the epistemological presuppositions and ontological understandings of social work may emerge.

Social justice means people from all identity groups have the same rights, opportunities, access to resources, and benefits. It acknowledges that historical inequalities exist and must be addressed and remedied through specific measures including advocacy to confront discrimination, oppression, and institutional inequalities, with recognition that this process should be participatory, collaborative, inclusive of difference, and affirming of agency.

Using this modified and updated definition across the field may help educators and practitioner better operationalize the concept of social justice, resulting in better engagement with and outcomes for students and clients alike.

Social work has debated the meaning of social justice for decades. While debate and theorization of concepts is an important process for the field, especially when approaching topics from a critical lens, social work must work toward a clear understanding of a definition that is better aligned with its mission and clearly understood by social work educators, scholars, and practitioners, echoing Banerjee’s (2011) call to develop a new theory of social justice that is inclusive of more than just economic class—a suggestion that would mean that it is time for the field to leave Rawls behind. With a new approach to social justice the profession can embrace its history of activism ( Abramovitz, 1998 ; Reisch & Andrews, 2014 ) while also recognizing and atoning for harm done within the profession. The aforementioned harm is well documented in how social work practice and social work education have negatively impacted and interfaced with marginalized people and communities, both historically and currently, and also contributed to, maintained, and perpetuated the status quo ( Ritter, 2012 ; Specht & Courtney, 1995 ).

In addition to looking at how we as social workers understand and operationalize social justice, we must also come to agreement on its merit within our profession. The finding that 20 percent of the reviewed texts recognized the tension between the concept of social justice and the current practice of social work is evidence that we are still pushing back against an established connection via all guiding organizations and documents.

Funge (2011) noted in an examination of educators’ role in teaching social justice that many educators feel isolated in developing their understanding of social justice. Funge’s (2011) conclusion mirrors the findings of this conceptual review, that we, as social work academics and educators, are relying on several different understandings of social justice, often in isolation from more current and comprehensive conceptualizations. We must challenge the ease at which we as a profession rely on and profess a commitment to social justice in our everyday approach to social work practice and education, and recognize that our lack of commitment to a critical approach to social justice has real-life negative implications that perpetuate injustice. Perhaps now more than ever, as our political pendulum swings far outside the realms of a just world, it is time to come together as a profession and examine the value that roots us in our journeys as social workers. May this conceptual review be a starting place for that journey.

Abramovitz M. ( 1993 ). Should all social work students be educated for social change? Pro . Journal of Social Work Education , 29 , 6 – 13 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.1993.10778794

Google Scholar

Abramovitz M. ( 1998 ). Social work and social reform: An arena of struggle . Social Work , 43 , 512 – 526 .

Abrams L. , Dettlaff A. ( 2020 , June 23). An open letter to NASW and allied organizations on social work’s relationship with law enforcement. https://medium.com/@alandettlaff/an-open-letter-to-nasw-and-allied-organizationson-social-works-relationship-with-law-enforcement-1a1926c71b28

American Psychological Association . ( 2017 ). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

Asakura K. , Maurer K. ( 2018 ). Attending to social justice in clinical social work: Supervision as a pedagogical space . Clinical Social Work Journal , 6 , 289 – 297 . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10615-018-0667-4

Atteberry-Ash B. , Speer S. R. , Kattari S. K. , Kinney M. K. ( 2019 ). Does it get better? LGBTQ social work students and experiences with harmful discourse . Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services , 31 , 223 – 241 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2019.1568337

Banerjee M. M. ( 2011 ). Social work scholars’ representation of Rawls: A critique . Journal of Social Work Education , 47 , 189 – 211 . https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2011.200900063

Banerjee M. M. , Canda E. R. ( 2012 ). Comparing Rawlsian justice and the Capabilities Approach to justice from a spiritually sensitive social work perspective . Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought , 31 , 9 – 31 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15426432.2012.647874

Barker R. L. ( 2003 ). The social work dictionary (5th ed.). NASW Press .

Google Preview

Barker R. L. ( 2013 ). The social work dictionary (6th ed.). NASW Press .

Byers D. S. , McInroy L. B. , Craig S. L. , Slates S. , Kattari S. K. ( 2020 ). Naming and addressing homophobic and transphobic microaggressions in social work classrooms . Journal of Social Work Education , 56 , 484 – 495 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1656688

Council on Social Work Education . ( 2022 ). Educational policy and accreditation standards for baccalaureate and master’s social work programs . Author.

Davis A. , Mirick R. ( 2022 ). Microaggressions in social work education: Learning from BSW students’ experiences . Journal of Social Work Education , 58 , 431 – 448 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2021.1885542

Davis M. ( 2021 ). Anti-Black practices take heavy toll on mental health . Nature Human Behaviour , 5 , 410 . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01058-z

Dettlaff A. J. , Weber K. , Pendleton M. , Boyd R. , Bettencourt B. , Burton L. ( 2020 ). It is not a broken system, it is a system that needs to be broken: The upEND movement to abolish the child welfare system . Journal of Public Child Welfare , 14 , 500 – 517 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15548732.2020.1814542

Finn J. L. ( 2016 ). Just practice: A social justice approach to social work . Oxford University Press .

Funge S. P. ( 2011 ). Promoting the social justice orientation of students: The role of the educator . Journal of Social Work Education , 47 , 73 – 90 . https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2011.200900035

Garcia B. , Van Soest D. ( 2006 ). Social work practice for social justice: Cultural competence in action. Council on Social Work Education.

Herrenkohl T. I. , Scott D. , Higgins D. J. , Klika J. B. , Lonne B. ( 2021 ). How COVID-19 is placing vulnerable children at risk and why we need a different approach to child welfare . Child Maltreatment , 26 , 9 – 16 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520963916

Hollingsworth L. D. , Patton D. U. , Allen P. C. , Johnson K. E. ( 2018 ). Racial microaggressions in social work education: Black students’ encounters in a predominantly White institution . Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work , 27 , 95 – 105 . https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2017.1417942

Hong P. Y. , Hodge D. ( 2009 ). Understanding social justice in social work: A content analysis of course syllabi . Families in Society , 90 , 212 – 219 . https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3874

International Federation of Social Workers . ( 2014 ). Global definition of the social work profession. https://www.ifsw.org/what-is-social-work/global-definition-of-social-work/

Jacobs L. A. , Kim M. E. , Whitfield D. L. , Gartner R. E. , Panichelli M. , Kattari S. K. , Downey M. M. , McQueen S. S. , Mountz S. E. ( 2021 ). Defund the police: Moving towards an anti-carceral social work . Journal of Progressive Human Services , 32 , 37 – 62 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10428232.2020.1852865

James S. E. , Herman J. L. , Rankin S. , Keisling M. , Mottet L. , Anafi M. ( 2016 ). The report of the 2015 U.S. transgender survey. National Center for Transgender Equality.

Longres J. , Scanlon E. ( 2001 ). Social justice and the research curriculum . Journal of Social Work Education , 37 , 447 – 463 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2001.10779067

Morgaine K. , Capous-Desyllas M. ( 2014 ). Anti-oppressive social work practice: Putting theory into action . SAGE .

Morris P. M. ( 2002 ). The capabilities perspective: A framework for social justice . Families in Society , 83 , 365 – 373 .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 1960 ). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers . NASW Press .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 1967 ). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers . NASW Press .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 1979 ). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers . NASW Press .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 1996 ). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers . NASW Press .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 1999 ). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers . NASW Press .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 2008 ). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers . NASW Press .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 2017 ). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers . NASW Press .

National Association of Social Workers . ( 2021 ). Code of ethics of the National Association of Social Workers . NASW Press .

Nong P. , Raj M. , Creary M. , Kardia S. L. R. , Platt J. E. ( 2020 ). Patient-reported experiences of discrimination in the US health care system . JAMA Network Open , 3 , Article e2029650 . https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29650

Nussbaum M. ( 2003 ). Capabilities as fundamental entitlements: Sen and social justice . Feminist Economics , 9 , 33 – 59 . https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570022000077926

Nutley S. , Davies H. , Walter I. ( 2002 ). Conceptual synthesis 1: Learning from the diffusion of innovations . Research Unit for Research Utilisation , Department of Management, University of St Andrews .

Petticrew M. , Roberts H. ( 2005 ). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide . Blackwell .

Rawls J. ( 1971 ). A theory of justice . Belknap Press .

Rawls J. ( 1999 ). A theory of justice (Rev. ed.). Belknap Press .

Rawls J. ( 2001 ). A theory of justice: A restatement . Belknap Press .

Reisch M. ( 2010 ). Defining social justice in a socially unjust world. In Bierkenmaier J. M. , Cruce A. , Curley J. , Burkemper E. , Wilson R. J. , Stretch J. J. (Eds.), Educating for social justice: Transformative experiential learning (pp. 11 – 28) . Lyceum Books .

Reisch M. , Andrews J. ( 2014 ). The road not taken: A history of radical social work in the United States . Routledge .

Rine C. M. ( 2021 ). Considering social work roles in policing [Editorial] . Health & Social Work , 46 , 85 – 87 . https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlab010

Ritter J. A. ( 2012 ). Social work policy practice: Changing our community, nation, and the world . Pearson .

Roberts D. ( 2020 , June 16). Abolishing policing also means abolishing family regulation. The Imprint. https://imprintnews.org/child-welfare-2/abolishing-policing-also-means-abolishing-family-regulation/44480

Rountree M. A. , Pomeroy E. C. ( 2010 ). Bridging the gaps among social justice, research, and practice [Editorial ]. Social Work , 55 , 293 – 295 . https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/55.4.293

Sen A. ( 1992 ). Inequality reexamined . Russell Sage Foundation .

Specht H. , Courtney M. ( 1995 ). Unfaithful angels: How social work has abandoned its mission . Free Press .

Thorenson R. ( 2018 , July 23). “You don’t want second best”: Anti LGBT discrimination in US health care. Human Rights Watch. https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/07/23/you-dont-want-second-best/anti-lgbt-discrimination-us-health-care

Uehara E. , Flynn M. , Fong R. , Brekke J. , Barth R. P. , Coulton C. , Davis K. , DiNitto D. , Hawkins J. D. , Lubben J. , Manderscheid R. , Padilla Y. , Sherraden M. , Walters K. ( 2013 ). Grand Challenges for Social Work . Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research , 4 , 165 – 170 . https://doi.org/10.5243/jsswr.2013.11

Van Soest D. , Garcia B. ( 2003 ). Diversity education for social justice: Mastering teaching skills . Council on Social Work Education.

Wakefield J. C. ( 1988a ). Psychotherapy, distributive justice, and social work: Part 1: Distributive justice as a conceptual framework for social work . Social Service Review , 62 , 187 – 210 . https://doi.org/10.1086/644542

Wakefield J. C. ( 1988b ). Psychotherapy, distributive justice, and social work: Part 2: Psychotherapy and the pursuit of justice . Social Service Review , 62 , 353 – 382 . https://doi.org/10.1086/644555

Wong R. , Jones T. ( 2018 ). Students’ experiences of microaggressions in an urban MSW program . Journal of Social Work Education , 54 , 679 – 695 . https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2018.1486253

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1545-6846

- Print ISSN 0037-8046

- Copyright © 2024 National Association of Social Workers

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, documenting social justice in library and information science research: a literature review.

Journal of Documentation

ISSN : 0022-0418

Article publication date: 18 January 2021

Issue publication date: 8 April 2021

The purpose of this study is to provide an overview of social justice research in library and information science (LIS) literature in order to identify the research quantity, what populations or settings were included and future directions for this area of the discipline through examination of when related research was published, what contexts it covered and what contributions LIS researchers have made in this research area.

Design/methodology/approach

This study reviews results from two LIS literature databases—Library, Information Science and Technology Abstracts (LISTA) and Library and Information Science Source (LISS)—that use the term “social justice” in title, abstract or full text to explicitly or implicitly describe their research.

This review of the literature using the term social justice to describe LIS research recognizes the significant increase in quantities of related research over the first two decades of the 21st century as well as the emergence of numerous contexts in which that research is situated. The social justice research identified in the literature review is further classified into two primary contribution categories: indirect action (i.e. steps necessary for making change possible) or direct action (i.e. specific steps, procedures and policies to implement change).

Research limitations/implications

The findings of this study provide a stronger conceptualization of the contributions of existing social justice research through examination of past work and guides next steps for the discipline.

Practical implications

The conceptualizations and related details provided in this study help identify gaps that could be filled by future scholarship.

Originality/value

While social justice research in LIS has increased in recent years, few studies have explored the landscape of existing research in this area.

- Direct action

- Indirect action

- Library and information science

- Literature review

- Social justice

Winberry, J. and Bishop, B.W. (2021), "Documenting social justice in library and information science research: a literature review", Journal of Documentation , Vol. 77 No. 3, pp. 743-754. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-08-2020-0136

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Teaching Social Justice in Undergraduate Nursing Education: An Integrative Review

- PMID: 34605690

- DOI: 10.3928/01484834-20210729-04

Background: Clarification of best practices in teaching social justice concepts is necessary to prepare undergraduate nursing students to address health care disparities.

Method: An integrative literature review was used to analyze literature describing coursework, teaching methods, sites for application of learning, and methods to evaluate student learning.

Results: Junior- and senior-level coursework and optional opportunities were identified. Traditional and nontraditional approaches to teaching also were evident. Nursing students applied knowledge at sites where health care was provided and vulnerable populations were served, as well as in simulated environments. Evaluation of learning occurred related to students' abilities to inform an empathetic understanding, analyze the community, and become change agents.

Conclusion: Social justice can be threaded throughout the curriculum with the use of traditional and nontraditional teaching strategies. The application of learning can occur in a variety of settings with evaluation demonstrating students' ability to take action to advocate for social justice. [ J Nurs Educ . 2021;60(10):545-551.] .

Publication types

- Education, Nursing, Baccalaureate*

- Social Justice

- Students, Nursing*

Social Justice Books

Critically reviewed selection of multicultural and social justice books for children, young adults, and educators.

Carefully selected multicultural and social justice books for children, young adults, and educators on 100+ topics.

Critical reviews of children’s and young adult books from dozens of vetted sources, consolidated here for easy access.

Articles and news on book bans and how to challenge them; multicultural children’s book awards; and diversity in new books.

Articles & News

Featured Articles & Reviews

Teach banned books buttons, guide for selecting anti-bias children’s books, review of that flag by tameka fryer brown, “free our books” say fourth graders, follow us on instagram @sojustbooks, about socialjusticebooks.org.

SocialJusticeBooks.org is a project of Teaching for Change , a non-profit organization whose mission is to provide teachers and parents with the tools to create schools where students learn to read, write, and change the world. Teaching for Change developed SocialJusticeBooks.org in 2017 to share critically reviewed selections of multicultural and social justice books for children, young adults, and educators. Learn more .

If you enjoy this resource, please support our work by donating to Teaching for Change .

- Last Updated: Feb 7, 2024 3:23 PM

- Clark College Libraries

- Research Guides

- SOC 201 - Social Problems: The Pursuit towards Social Justice (Ludwig)

- Literature Review Infographic

SOC 201 - Social Problems: The Pursuit towards Social Justice (Ludwig): Literature Review Infographic

- Exploring Topics

- How to Search in Databases

- Find Academic Sources

- Search Multiple EBSCO Databases

- Google Search Tips

- SIFT (The Four Moves)

- Media Bias Chart

- APA 7 Examples

- Social Justice Organizations

- Off-Campus Database Access

- Library Session_5/9_7-8pm

- Literature Review Infographic Text Only

4 Step Guide to Writing a Literature Review

1. what is a literature review.

A literature review is a description of the literature relevant to a particular field or topic.

It gives an overview of:

- what has been said

- key writers

- prevailing theories and hypotheses

- questions being asked

- appropriate and useful methods and methodologies

It make take two forms

- Purely descriptive - as in an annotated bibliography. A descriptive review should not just list and paraphrase, but should add comment and bring out themes and trends.

- A critical assessment of the literature in a particular field, stating where tje weaknesses amd gaps are, contrasting the views of particular authors, or raising questions. It will evaluate and show relationships, so that key themes emerge.

- A whole paper, which annotates and/or critiques the literature in a particular subject area.

- Part of a thesis or dissertation, forming an early context-setting chapter.

- A useful background outlining a piece of research, or putting forward a hypothesis.

DO look at the relationships between the views and draw out themes

DON'T just write a list of quote authors without citing them.

2. The Stages of a Literature Review.

Define the problem.

- It is important to define the problem or area which you wish to address.

- Have a purpose for your literature review to narrow the scope of what you need to look out for when you read.

Carry out a search for relevant materials.

- Peer reviewed journal articles

- Newspaper articles

- Historical records

- Commercial/government reports and statistical information

- Theses and dissertations

- Other relevant information

- Search the university or academic library with a good collection in your subject area.

- Search using the internet--but be sure to avoid the pitfalls.

- Use specific rather than general keywords and phrases for your search strategy.

Evaluate the materials.

Points to consider when evaluating material:

- Author credentials--are they an expert in the field? Are they affiliated to a reputable organization?

- Date of publication--is it sufficiently current or has knowledge moved on?

- If a book--is it the latest edition?

- If a journal--is it a peer reviewed, scholarly journal?

- Is the publisher reputable and scholarly?

- Is it addressing a scholarly audience?

- Does it review relevant literature?

- Is it an objective fact-based viewpoint? Is it logically organized and clear to follow?

- Does it follow a particular theoretical viewpoint, e.g.feminist?

- What is the relationship of this work to other material on the same topic--does it substantiate it or add a different perspective?

- If using research, is the design sound? Is it primary or secondary material?

- If it is from a practice-based perspective, what are the implications for practice?

Analyse the findings.

- What themes emerge, and what conclusions can be drawn?

- What are the major similarities and differences between various writers?

- Are there any significant questions which emerge and which could form a basis for further investigation?

3. How to Organize a Literature Review

Introduction: Define the topic and state reasons for choice. You could also point out overall trends, gaps and themes that emerge.

Body: Discuss your sources. You can organize your discussion chronologically, thematically or methidologically.

Conclusion: Summarize the major contributions, evaluating the current position, and pointing out flaws in methodology, gaps in the research, contradictions and areas for further study.

You are now at the stage when you can write up your literature review.

4. Further Information.

These universities have good information on how to write a literature review:

- Deakin University--http://www.deakin.edu.au/library/research/index.php

- University of Wisconsin-Madison--http://www.wisc.edu/writing/Handbook/ReviewofLiterature.html

- University of North Carolina--http://www.writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/literature-reviews/

- University of California, Santa Cruz--http://www.library.ucsc.edu/ref/howto (Follow links to "Write a Literature Review".)

Brought to you by Emerald Group Publishing www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com

- << Previous: Media Bias Chart

- Next: APA Citation Style >>

- URL: https://clark.libguides.com/soc201-ludwig

facebook twitter blog youtube maps

Promoting Social Justice Through Usability in Technical Communication: An Integrative Literature Review

doi: https://doi.org/10.55177/tc584938

By Keshab Raj Acharya

Purpose : Recently, interest in usability has grown in the technical communication (TC) field, but we lack a current cohesive literature review that reflects this new growth. This article provides an integrative literature review on usability, its goals, and approaches to accomplish those goals in relation to TC’s commitment to social justice and empowerment.

Methods : I conducted an integrative literature review on usability to synthesize and characterize TC’s growing commitment to social justice and empowerment. I searched scholarly publications and trade literature that included books and book chapters on usability. Adopting grounded theory and content analysis as research techniques to systematically evaluate data corpus, I read and classified selected publications to approach the research questions and iteratively analyzed the data to identify themes within each research question.

Results : Surveying the definitions and descriptions of usability in the literature corpus shows that there is no consensus definition of usability. Findings suggest that the goal of usability can be classified as: a) pragmatic or functional goals, b) user experience goals, and c) sociocultural goals. Given the recent cultural and social justice turns in TC, my findings reveal a number of social justice-oriented design approaches for usability.

Conclusions : Usability should not be viewed solely as a means of achieving pragmatic and/or user experience goals. Practitioners also need to consider usability from sociocultural orientations to accomplish its sociocultural goals. From interconnected global perspectives, the review implies the need for adopting more viable and culturally sustaining design approaches for successfully accommodating cultural differences and complexities for promoting social justice and user empowerment.

KEYWORDS : usability, integrative literature review, localization, social justice, user empowerment, inclusion, technical communication

Practitioner’s Takeaway

- Provides an overview of usability, its goals, and the approaches for accomplishing those goals;

- Offers broader perspectives on usability in relation to designing technical products, systems, or tools that satisfy the demands and contingencies of culturally diverse users, including underprivileged, underserved, and marginalized user groups;

- Offers insights on approaching usability from social justice perspectives to create meaningful and empowering technical products by recognizing the shift from pragmatic usability to sociocultural orientations of usability

INTRODUCTION

Usability is a central concern in technical communication (TC) when designing products, systems, or tools—such as application interfaces, websites, software, online help systems, and print or online documentation—from users’ perspectives (Alexander, 2013; Johnson, 1998; Redish, 2010; Salvo, 2001; Scott, 2008). Usability research demonstrates why designers should heed to generate tools that are easy to use and understand for the intended users (Barnum, 2002; Dumas & Redish, 1993; Gould & Lewis, 1985). Recognizing the need for and importance of creating such tools from users’ viewpoint, interest in usability research and practice in differing cultural contexts has also been growing recently in the TC field (see, for example, Agboka, 2014; Cardinal, Gonzales, & Rose, 2020; Dorpenyo, 2020; Gonzales & Zantjer, 2015; Gu & Yu, 2016; Saru & Wojahn, 2020; Sun, 2020). In fact, usability has many natural ties to TC and both have a long, intertwined history since the 1970s through today (Breuch, Zachry, & Spinuzzi, 2001; Redish, 2010; Redish & Barnum, 2011).

Despite the long inherent connections between usability and TC, our field lacks an integrative literature review to better understand usability in relation to the field’s recent cultural and social justice turns. Such a lack draws attention to the need for investigating “how communication, broadly defined, can amplify the agency of oppressed people—those who are materially, socially, politically, and/or economically under-resourced” (Jones & Walton, 2018, p. 242). To be clear, an integrative literature review works to assemble “representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated” (Torraco, 2016, p. 356). The lack of synthesis in research makes it difficult to review emerging topics, ideas, or concepts that generate new knowledge and a growing body of literature about the topic reviewed (Torraco, 2016). Because such review is performed to “make a significant, value-added contribution to new thinking in the field” (Torraco, 2005, p. 358), this study aims to accomplish this by holistically understanding:

- usability and its goals in TC research and scholarship;

- design approaches to promote social justice and user empowerment; and

- the extent to which usability research in the TC field has been conducted in international contexts.

More specifically, this integrative literature review sought to address the following two research questions:

RQ1: How is usability defined, and what are its goals?

Rq2: what design approaches have been proposed to promote social justice and user empowerment.

To address these questions, I undertook an integrative literature review of usability in both peer-reviewed TC journal articles and trade literature that included books and book chapters on usability over the past 40 years. As discussed in detail later, I compiled a data set consisting of 27 books, 14 book chapters, and 82 journal articles over a span of 40 years (1980–2020). Drawing upon grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015) and content analysis as research techniques (Huckin, 2004; Krippendorff, 2019), I analyzed the representative data set for emergent and recurring themes by unitizing (segmenting the text for analysis), sampling (selecting an appropriate collection of texts for analysis), and validating (using the consistent coding scheme) the data corpus (Boettger & Palmer, 2010).

In what follows, I first provide a brief note on how the emergence, expansion, and current state of usability development influenced my research. I then discuss my research method followed by the results as answers to my research questions. Finally, I highlight the implications of the study and conclude by providing suggestions for further research.

A Brief Note on the Emergence and Evolution of Usability

Along with the development of computer technology in the early 1980s, the usability profession largely started by raising usability issues related to user interfaces (Johnson, 1998; Redish, 2010; Redish & Barnum, 2011). When Apple introduced the Macintosh in 1984, issues concerning computer interfaces prevailed in usability engineering as novice users struggled to perform desired tasks due to a fundamental mismatch between the design of a technology and users’ expectations and capabilities (Sedgwick, 1993). To address such concerns, many usability specialists, especially from the engineering field, advocated for user research to improve usability (Barnum, 2002; Nielsen, 1993). In designing interfaces from users’ perspective, scholars argued for integrating the think-aloud method into the design process to ask users to verbalize their thoughts while interacting with the system (Boren & Ramey, 2000; Ericsson & Simon, 1980; Hughes, 1999; Mack, Lewis, & Carroll, 1983; Whiteside, Bennett, & Holtzblatt, 1988).

Decades of discussions in TC as a field have also consistently emphasized the need for designing technical products through the lens of usability (Carroll, 1990; Johnson, 1994; Schneider, 2005; Schriver, 1993; Spinuzzi, 2003; Sullivan, 1989); thus, the relevance of usability to technical communication had inherent support. Though usability has long been advocated for creating usable products in the context of use (St.Amant, 2015, 2017a; Sun, 2012; Zachry & Spyridakis, 2016), recent usability research and practices in TC move toward approaching usability for social justice and user empowerment (Acharya, 2018; Dorpenyo, 2020; Light & Luckin, 2008; Walton, 2016). This integrative review was initiated by acknowledging this new direction in usability for promoting social justice and user empowerment (i.e., enabling users of a product, including underserved and underprivileged user groups, to accomplish their intended goals with all possibilities and improve their quality of life).

METHODOLOGY

For this study, I collected data from both scholarly publications and trade literature to gain a full picture of usability and its implications for TC work. Data sources could be expanded to a wide range of publications on usability, including gray literature (i.e., literature published outside of traditional, commercial, or academic publishing and distribution channels). But, I confined my review only to trade literature and five major TC journals because I needed “logical parameters to set boundaries for the study” (Melonçon & St.Amant, 2018). Otherwise, I would still be searching, coding, and analyzing data sets. All sources of literature for inclusion fulfilled the following criteria:

- published over the last four decades (1980–2020, at the time of this study)

- focused primarily on usability, usability research, and practice in relation to TC

- helped shape my research questions

I chose the 1980s as my corpus’s starting point because the decade represents many technical communicators’ significant transition from writing as user advocates to functioning as usability specialists (McGovern, 2005; Redish & Barnum, 2011).

The data search was an iterative process. I conducted several trial runs with the keyword categories, refining and modifying the keywords to gain the best possible results. I used the Boolean special characters * to optimize the keywords and “” to search for exact phrasings, as well as the Boolean terms AND, OR, and NOT to look for overlapping concepts and produce more relevant research. As a result, I used the following list of keywords for each database and search engine: usability* AND technical communication , usability AND usability testing, “usability research , ” “user-centered technology,” usability*/in technical comm*, “localized usability,” cross-cultural/design*, “human-centered design OR user experience design .”

In order to capture my research topic broadly and isolate information irrelevant to this study, I compiled the corpus from the following repositories:

- my university library databases, including IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and ACM Digital Library, as well as the general database

- Google Scholar, Amazon.com, and Google Books

- Technical Communication

- Journal of Technical Writing and Communication (JTWC)

- Journal of Business and Technical Communication (JBTC)

- IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication (IEEE)

- Technical Communication Quarterly (TCQ)

I selected these journals based on past research practices exhibited by TC researchers and practitioners, including Boettger and Lam (2013) and Melonçon and St.Amant (2018). As we know, these journals are “the markers of the disciplines’ knowledge creation and perpetuation” (Boettger & Palmer, 2010) and the “core/central sources of scholarship in the [TC] field” (Melonçon & St.Amant, 2018, p. 132).

In addition to the literature found through the broad search of the databases and search engines, I checked sources included in the reference lists of the articles and their original publication venues to validate findings and enrich the analysis. This process also allowed me to “find additional relevant literature by examining references in the literature already obtained” (Torraco, 2016, p. 416).

In scholarly publications, I included only full-length, research-based articles (i.e., no commentaries, book reviews, etc.). This scope produced a data corpus of 129 scholarly publications and 51 trade publications. I evaluated each source iteratively to determine their relevance to usability in TC to further narrow the sample. This left a study size of 82 articles, 27 books, and 14 book chapters based on the above criteria. The analysis and discussion that follows is confined only to these 123 data sources.

Informed by content analysis (Huckin, 2004; Krippendorff, 2019), also a major research methodology in TC (see, for example, Boettger & Palmer, 2010; Brumberger & Lauer, 2015; King & McCarthy, 2018), I evaluated the collected texts for emergent and recurring themes by unitizing (segmenting definitions of relevant units), sampling (selecting samples for analysis), and validating (employing the consistent coding scheme) the representative data corpus. Adopting standard research coding techniques (Coffey & Atkinson, 1996) and grounded theory (Charmaz, 2014; Corbin & Strauss, 2015), I performed initial coding by reviewing each data source to distinguish concepts and categories. In the second phase of coding (i.e., axial coding), I assembled the categories into causal relationships by grouping, sorting, and reducing the number of codes generated from the first cycle of coding (Charmaz, 2014). This process allowed me to see the relationships between concepts and categories developed in the open coding process (Corbin & Strauss, 2015).

To evaluate the corpus from the lens of content analysis, I developed starter codes and piloted them on the data sets to norm my data analysis approach. Then, I conducted pattern coding to pull materials together into more meaningful units to identify key themes, configuration, and explanation (Miles & Huberman, 1994). I coded the data corpus iteratively to maintain the degree of consistency and reduced the clusters to the point of saturation through the process of analysis and reanalysis (Charmaz, 2014). Once themes were derived, I reevaluated their relationships based on my research questions as broad organizational thematic categories.

Just as with other research work, this study has its limitations and strengths. For instance, I did not include publications on usability from sources such as magazines, professional blog postings, podcasts, and slide decks. Because the origin of usability has no single root, the review cannot be regarded as an ultimate synthesis of usability scholarship in TC. Although I do believe that an expanded version of the review might synthesize knowledge on the topic by offering different perspectives, doing so carefully and thoughtfully would be enormously labor intensive and time consuming (Melonçon & St.Amant, 2018). Additionally, other researchers looking at the same corpus might draw different conclusions and implications.

This section presents the results of my review of the usability literature to address each of my research questions.

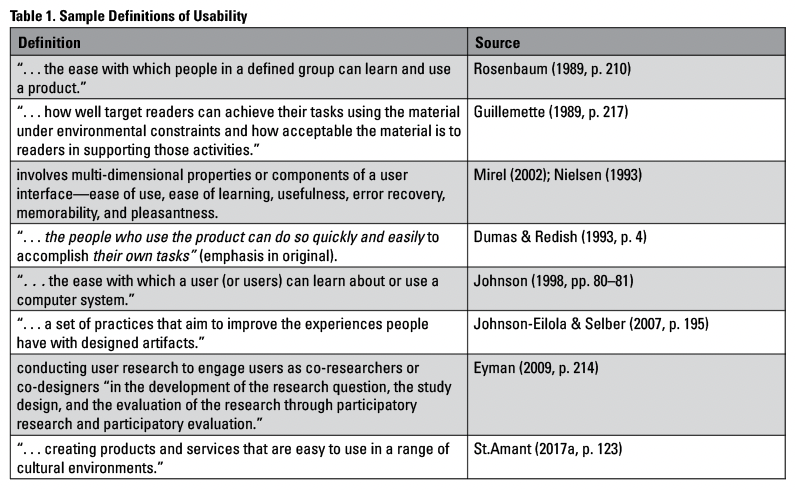

To address this question, I focused on how the term “usability” was defined and discussed by authors in the consulted scholarly publications and trade literature. My findings showed that usability can refer to a process (i.e., a form of evaluation), a characteristic (i.e., the degree to which a product or system is usable), and a professional discipline (i.e., an approach to or study of user research to better understand user needs, expectations, and behaviors). In other words, usability is a multifaceted construct used by different disciplines for different purposes and meanings (Table 1).

The term “usability” is traditionally used to mean how easily and quickly an individual can use a product to perform a desired objective (Barnum, 2002, 2011; Dumas & Redish, 1993; Gould & Lewis, 1985; Nielsen, 1993; Rosenbaum, 1989; Whiteside, Bennett, & Holtzblatt, 1988). As Table 1 displays, usability refers to the degree to which a product can be effectively used by target users to perform intended tasks (Guillemette, 1989; Rosenbaum, 1989). The definition also includes more specific attributes such as efficiency, effectiveness, learnability, accuracy, satisfaction, error recovery, and retention over time (Nielsen, 1993; Quesenbery, 2003; Shneiderman, Plaisant, Cohen, Jacobs, Elmqvist, & Diakopou, 2018). Johnson (1998) examines usability as an iterative process that helps achieve desired goals by means of repeated cycles of testing a product or system. In Mirel’s (2002) view, usability is not related to one specific dynamic feature or attribute but to a comprehensive whole that provides users with a good, positive work experience. According to Haaksma, De Jong, and Karreman (2018), “These days, usability includes not only ease of use, but also factors of efficacy and appreciation” (p. 117).

As rooted in several broad disciplines such as psychology, human factors, and cognitive science, usability is also understood as a discipline that is concerned with the design, evaluation, and implementation of interactive products, systems, or tools. As argued by Spinuzzi (2001), usability relates to the entire activity system in which a product is used—the system involving society, culture, history, and interpretation. Broadly speaking, usability as a discipline is about researching and designing effective technical products or materials by engaging users as co-researchers or co-designers (Eyman, 2009; Salvo, 2001; Simmons & Zoetewey, 2012; Spinuzzi, 2001).

Examining usability from a cross-cultural stance, Sun (2012), on the other hand, asserts that usability is not just about the functionality of a product, but it should be understood in terms of a holistic view of design “as both situated action and constructed meaning” in the differing cultural context of use (p. 55). Similarly, Agboka (2013) looks at usability from participatory localized perspectives, meaning empowering users by accommodating cultural factors prevalent in users’ sites. Agboka (2013) implicitly hints that usability means how well local practices and values are incorporated into a product for a user from another culture.

As TC goes global and businesses engage in some form of international interaction, usability should be viewed from the perspective of meeting end users’ needs and expectations across a range of cultural environments (St.Amant, 2017b). In short, usability, particularly in TC, is now broadly perceived as a rhetorical practice for designing a product that satisfies the demands and contingencies of culturally diverse users, including underserved and underprivileged user groups, in the increasingly globalized world.

Thus, my findings show that one definition of usability cannot be provided because its definition “change[s] from context to context,” from community to community (Salvo, 2001, p. 276). Findings suggest that besides two types of definitions of usability commonly present as process-focused definitions and user-focused definitions, there is a third type that I classify as sociocultural-focused definitions of usability associated with sociocultural aspects of a product for user empowerment, inclusion (Ladner, 2015; Light & Luckin, 2008; Rose, 2016; Sun, 2020; Walton, 2016), and accessibility (Gonzales, 2018; Roberts, 2006; Saru & Wojahn, 2020).

Goals of Usability

As the definition of usability varies depending on the disciplinary practices of scholars, there are certain goals of usability implementation. Based on my study of the collected data sources, I grouped these goals into three thematic categories: a) pragmatic goals, b) user experience goals, and c) sociocultural goals. The following section discusses each category in turn.

Pragmatic Goals

The pragmatic goals of usability are typically associated with the activities that are performed to assess how quickly and easily users use the product to achieve their desired objectives (Barnum, 2002; Dumas & Redish, 1993; Krug, 2014; Nielsen, 1993). In other words, the goals that involve optimizing a user’s interaction with a product come under this category. As discussed by Nielsen (1993), Quesenbery (2003), and Shneiderman et al. (2018), pragmatic or functional goals are primarily related to usability attributes, including:

- Learnability : how easy the product is for a new user to learn and work with;

- Efficiency : how well the user can perform the assigned tasks;

- Memorability : how easily the user can re-establish proficiency after a long time of use;

- Error recovery : how easily the user can recover from any incorrect user action made when using the product;

- Utility : to what extent the product provides the right kind of functionality to enable the user to perform desired tasks; and

- Time : how long it takes for the user to learn how to use actions relevant to a set of tasks.

Pragmatic goals are useful for measuring the extent to which a product is usable in a given context. However, they do not help address the overall quality of the user’s interaction with and perceptions of the product, which is where the user experience goals of usability come into play.

User Experience Goals