OHSU Visitors and Volunteers

- Enter keyword Search

Volunteer Opportunities in Research

Shadow opportunities restricted.

Currently, high school students and undergraduates who want to observe clinical operations and/or visit clinical areas must be a part of vetted and approved through established OHSU programs. See a list of approved programs.

The Clinical Research Investigative Studies Program (CRISP) exposes vetted pre-health students to the world of clinical research in emergency medicine through prospective ED research projects at the Marquam Hill campus. The CRISP program will give students considering potential health related careers hands on experience in the Emergency Department (ED) helping facilitate the completion of clinical research studies. The students will interact with both Emergency Department patients and research investigators. Since 2004, CRISP students have successfully screened, consented, and enrolled thousands of patients into multiples studies of varying complexity, including FDA drug and device trials, and cross-sectional and prospective survey studies.

Our CRISP students undergo hours of rigorous fundamental concepts of clinical research, confidentiality, consent and procedural skills, practice informed consent, continuous learning that provides ongoing research education including the CITI modules on Human Subjects Protection, GCPs, and HIPAA. Once trained, the CRISP student will use EPIC (the electronic health record system at OHSU) to proficiently screen all patients who come into the OHSU Emergency Department for each active study protocol. If a patient is deemed eligible for the study, the CRISP student will inform the patient and/or the patient’s legal guardian (LAR) about the study, and proceed with the informed consent process if the patient is willing to participate. Once the patient is consented, the CRISP students will move forward with enrollment procedures which can range clinical data abstractions, patient surveys, and/or work with the ED treatment team to collect necessary patient samples and imaging such as ECGs, blood, urine, or stool.

For more details, www.ohsu.edu/crisp or view the CRISP information Flyer .

Commitment Requirements:

- Pre-health students, highly disciplined and motivated

- Able to commit to 2-four hour shifts (8 hours) per week for 12 weeks -then after 12 weeks able to commit to one-four hour (4 hour) shift per week – 1 year commitment

- Able to commit to 4h of mandatory office auditing shift

Eligibility :

- Pre-health students who can commit to the program for 1 year

- Excellent written and verbal communication skills

- Pre-health students who are highly motivated and detailed-oriented

Interested ? Please email [email protected] to get on the list. We will be hosting information sessions Quarterly throughout the year. To apply, www.ohsu.edu/applycrisp

The Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology is looking for a volunteer to assist with clinical trials conducted by the division. Current studies include research on monitoring and treatment of pancreas divisum, pancreatic cysts, colon adenomas, abdominal pain, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, chronic pancreatitis and ulcerative colitis.

- Primary Duties: Volunteers will assist with recruitment and eligibility screening, consenting and enrolling participants, conducting study visits and entering data. Additional responsibilities will depend on the volunteer’s interests and the needs of the research team.

- Commitment: Minimum of 10 hours per week for 6 months.

- Eligibility : V olunteers should be an undergraduate student, post bac, graduate student, or medical student interested in gaining clinical-translational research experience. Must be detail oriented, organized, timely, and professional. Basic knowledge of computer application software preferred.

- Interested? Please apply by sending a CV and cover letter explaining your interest to Heather Katcher .

The Novel Interventions in Children’s Healthcare (NICH) program serves youth with a range of complex medical conditions and psychosocial vulnerabilities (e.g., insufficient access to resources, mental health issues, involvement with foster care system). The NICH research team, under direction of Drs. David Wagner and Michael Harris, is evaluating the ability of NICH to meet the triple healthcare aim: improving health, improving care, and reducing medical costs. Currently we are looking for research volunteers to help with a new study assessing risk factors of poor health outcomes in youth with type 1 diabetes who would be most likely to benefit from the program. This is a great educational and training opportunity for those interested in pursuing graduate study in psychology, social work, public health, pediatrics, emergency medicine, and related fields.

- Primary Duties: Research volunteers will primarily assist with participant recruitment, scheduling and tracking completion of study tasks, and medical chart review. There is also opportunity for volunteers to contribute to scientific posters and complete their own independent research project in a lab-related topic.

- Eligibility: Must be a college junior, senior, or post bac. Must be comfortable interacting with individuals with diverse backgrounds in the hospital and community. Previous experience with adolescents and families, as well as access to reliable transportation, a plus, but not required.

- Commitment: Requesting a minimum commitment of 10 hours/week for 9-months.

- Interested? Please send Sydney Melnick ( [email protected] ) and Dr. David Wagner, PhD ( [email protected] ) a letter of interest, a resume and/or vita, and the names and contacts of 2 individuals who can provide professional references.

For more information about NICH, go to: https://www.ohsu.edu/xd/health/child-development-and-rehabilitation-center/clinics-and-programs/cdrc-portland-programs/nich/

The OHSU Innovation and Commercialization internship program is an educational experience for individuals interested in technology transfer, business development, and/or patent law. Get real-world experience assisting with innovation development and the transition of technology from laboratory to market. Eligible interns can receive a monthly stipend and/or academic credit for program participation. Please note that this program is primarily remote/virtual, but interns in the Portland metro area may have the opportunity for to attend some in-person meetings.

- Commitment: An average of 8 to 10 hours per week for at least six months time. Intern performance will be assessed every three months. The program length may be extended for interns in good standing, per a formal review process.

- Eligibility: Applicants must hold a bachelor's degree in a life science, a physical science, and/or engineering; be pursuing or have received a graduate-level degree in science, medicine, engineering, business, or law; and have an interest in intellectual property, technology transfer, and/or business development as a career goal.

- Interested? Please see the OHSU Innovation and Commercialization Internship Website for application instructions. Contact Nicole Garrison ( [email protected] ) with questions.

The Oregon POLST Registry is a secure electronic record of patient’s end-of-life treatment preferences (POLST- Portable orders for life-sustaining treatment). The Registry relies on the hard work of our generous volunteers to process communication with POLST patients via mailed registration confirmation. Registry confirmation packets include a letter confirming the registrant’s information, medical orders, and other printed materials. The Registry also sends out notifications when a registrant updates their POLST orders and notifications for POLST forms that are about to expire. Volunteers will gain experience handling PHI, diversify knowledge of HIPAA compliance in a non-clinical setting, and support emergency services. The Registry team is truly grateful for the time and energy that volunteers contribute to the Registry’s mission.

- Primary Duties : Preparation of registrant confirmation packets, update letters, and 10 year expiration letters. Volunteers will additionally verify that the content of the mail is being sent to the correct person.

- Commitment : Between 2-4 hours a week for a minimum of 3 months.

- Eligibility : Volunteers must be at least 16 years old. The hours are flexible but must be completed within The Registry’s business hours – Monday through Thursday 7:30 to 4:00 PM.

- Interested? Contact: [email protected] for more information.

The Pediatric Nephrology Department is actively involved with many ongoing national clinical trials including longitudinal observation studies, rare diseases, pharmacokinetics, and investigator initiated research.

- Primary Duties: Volunteers will assist research coordinators with study visits, data collection, data entry, and other scholarly activities with opportunities for networking and participation in publications. We are recruiting volunteers who are enthusiastic about research and would like to gain experience in working with pediatric clinical trials.

- Eligibility: Completion of bachelor degree in science field is preferred but will consider exceptionally qualified applicants. Pre-medical students are encouraged to apply. Must be detail oriented, organized, timely, and professional. Basic knowledge of computer application software preferred.

- Commitment: 6-16 hours per week for least 6 months.

- Interested? Please e-mail Kira Clark at [email protected] with a CV and cover letter.

The Prenatal Environment And Child Health (PEACH) Study, under the direction of Dr. Elinor Sullivan and Dr. Joel Nigg are looking for volunteers to aid in their study. The PEACH Study is a longitudinal research study that will follow mothers from the second trimester of pregnancy until the child is 5 years of age. The purpose of this study is to learn more about how prenatal factors, such as nutrition, influence infant and toddler behavior and risk of neurodevelopmental disorders such as ADHD. This study will determine which prenatal factors are the strongest predictors of alterations in infant and toddler behavior associated with neurodevelopmental disorders, and set the stage for new approaches to prevent or treat child mental health problems.

- Primary Duties : Volunteers may assist the lab with recruitment, eligibility screening, participant visits, data collection and scoring, data entry, cleaning of physiological data, coding of video taped visits, transcription of audio files and other general laboratory and administrative duties in support of the study. Specific responsibilities wi ll depend on each volunteer’s interests and strengths.

- Com mitment : A minimum of 4 -15 hours p er week for at least 1 year.

- Eligibility : Must be a junior, senior or post bac (or have exceptional qualifications). Coursework in nutrition, infant and early life development, neurophysiology, and infant and child behavior is preferred/ beneficial. Preferred minimum G PA of 3.0. Must have some availability during the workday with the possibility of working over weekends. Must have strong interpersonal skills, be detail oriented, organized, timely , and professional. Experience working with infants and young children is preferred but not required . Previous experience of behavioral coding if preferred but not required . Basic knowledge of computer application software (SPSS, Excel) is preferred.

- Interested? Please send your CV, your availability (days/times that you are available to volunteer) to [email protected] . If you have any questions, please contact Jessica Tipsord at [email protected] .

PRISM research team performs phase II-IV clinical trials in pulmonary clinics and hospital settings. We have multiple ongoing clinical trials in conditions like pulmonary artery hypertension, COPD, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. We accept highly disciplined volunteers to conduct chart reviews of study subjects/patients using electronic medical records (EPIC) and enter the information in a secure database and support research coordinators. Our offices are located on the 1st floor of Emma Jones Hall, Room 121. Shadowing opportunities will be offered to our volunteers after completion of 6 months of volunteering with PRISM.

- Primary Duties : Conduct chart reviews of study subjects/patients using electronic medical records (EPIC) and enter the information in a secure database and support research coordinators.

- Commitment : Volunteers are expected to be available at least two half days (8 hours) a week for a period of 12 months.

- Eligibility : Intended for pre-medical students interested in gaining research experience before applying to medical school. International medical graduates interested in gaining experience in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials in pulmonary critical care and sleep medicine may also apply.

- Interested ? Contact: [email protected] with your resume, and a statement of interest/goals for PRISM.

For more information, visit the Division ( https://www.ohsu.edu/school-of-medicine/pulmonary-critical-care-medicine ) and the study team ( https://www.prismtrials.com/ ) websites.

Intermittent research volunteer opportunities available for motivated graduate students or advanced undergraduate students interested in conducting research with transgender and gender diverse youth and their families. Example research projects include retrospective medical chart review, measurement development (e.g., gender euphoria measure), and quality improvement related to transition from pediatric to adult healthcare. The position would be directly supervised by Danielle Moyer, PhD, assistant professor in the OHSU Department of Pediatrics and Division of Psychology.

- Must have excellent interpersonal skills

- Comfortable working in a professional and clinical environment

- Strong writing skills

- Preferably detail oriented and organized

- Familiarity with psychology, medicine, or public health

- Prior experience with youth and/or the transgender community is a plus

- Lived experience or strong allyship preferred

- Commitment: Availability for volunteering for specific projects is subject to change, and specific volunteer duties and required hours will depend on the specific project and current project status. An individualized research training experience will be established based on availability as well as volunteer’s interests and goals. Publication opportunities and/or opportunities to observe clinical care may also be available. Please note that onboarding for non-OHSU affiliated volunteers may take up to 2 months, and therefore may not be a good fit for those looking for short-term experiences. Those affiliated with OHSU may also need additional onboarding.

- Contact Information: To inquire about current opportunities, please email Dr. Danielle Moyer at [email protected] with a brief statement of interest, availability to volunteer, and any current affiliation with OHSU. If an appropriate opportunity is available, you will be asked to provide your CV/resume and a professional/academic reference. Feel free to email for any qualifying questions or to learn more.

Pre-health (pre-nursing, pre-med, pre-PA, pre-pharmacy, etc.) undergraduate or graduate student volunteers are needed to assist the VirtuOHSU Simulation & Surgical Training Center, team in OHSU Simulation. OHSU Simulation is the health care simulation program at OHSU responsible for training a variety of health care providers in controlled and simulated environment, outside of the clinical setting. There are 3 major simulation centers on the OHSU, Portland, campus: VirtuOHSU Simulation & Surgical Training Center and Multnomah Pavilion Simulation on Marquam Hill as well as the Mark Richardson I Simulation Center in CLSB. This volunteer work would be up on Marquam Hill.

- Primary Duties: Duties include assisting with lab events, facilitating set up and break down of training sessions, maintenance of simulation models, administrative duties, organization of supplies, and assisting with the outreach events for surgical simulation. Volunteers work closely with medical students, residents, faculty, and OHSU Simulation Staff to accomplish the mission of OHSU Simulation.

- Volunteer Schedule: Flexible, Monday-Friday with variable hours between 0800-1700. Estimated 4-6 hours per week, no less than 2 hours for a day.

- High School Diploma or equivalent

- Must be at least 21 years of age for VirtuOHSU Simulation & Surgical Training Center

- Must be able to show current enrollment as an undergraduate or graduate student

- Must demonstrate excellence in verbal and written, communication, professionalism, motivation, reliability, organization, time management, and customer-service focus

- Candidate should be able to work independently and as part of a team, effectively multi-task, be attentive to detail, and possess an aptitude for problem-solving

- Individual must be able to lift and move 30 pounds easily as needed

- The volunteer will be willing to work within the same lab space as animal and cadaveric tissues occasionally

- Professional interest in medicine, health care, simulation, life sciences, and/or medical research

- Course work in pre-health, pre-medicine or life sciences

- Professional interest surgery (specifically for VirtuOHSU)

- Experience in event planning

- Interested? Please email Cover Letter, resume, include current GPA, references, and letter of recommendation to: VirtuOHSU Simulation Center: Elena An, Operations Director OHSU Simulation at [email protected]

Additional Details

- Parking access on Marquam Hill/OHSU campus is extremely limited. Please be prepared to walk, bike, or use public transit to and from OHSU

- See more information at http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/education/simulation-at-ohsu/

- It is expected that all volunteers dress in business casual attire (collared shirt, no jeans or shorts, no tennis shoes) or clean, well fit scrubs and closed toed shoes.

Please note: In compliance with Oregon law, OHSU’s COVID-19 Immunization and Education policy will go in effect Oct. 18, 2021. Visitors and volunteers who have an in-person assignment must be fully vaccinated (defined as having received both doses of an original two-dose COVID-19 vaccine, or one dose of an original single-dose COVID-19 vaccine, and at least 14 days have passed since the individual's final dose of COVID-19 vaccine) or adhere to any requirements set forth by OHSU's Occupational Health Clinic for unvaccinated individuals.

- Clinical Trials

Volunteering

Volunteers are an integral part of the research process. People with a particular disease as well as healthy people both can play a role in contributing to medical advances. Without volunteers, clinical studies simply would not be possible.

People volunteer for clinical studies for many reasons. They may have a:

- Desire to improve medical care for future generations

- Connection to a certain disease or illness, whether through personal experience or through friends or family

- Personal interest in science

Participating is a choice

Volunteering for a clinical study is a personal choice. You have no obligation to do so, and participation is not right for everyone. After enrolling in a study, you may leave at any time for any reason.

Getting involved

- Participate in a clinical study at Mayo Clinic. By better understanding how to diagnose, treat, and prevent diseases or conditions, we help people live longer, healthier lives. Researchers need volunteers for a broad range of clinical studies. Find a clinical study .

- Connect with us. Eligibility requirements vary for each study and determine the criteria for participation. There is no guarantee that every individual who qualifies and wants to participate in a trial will be enrolled. Connect with the study staff directly as they are in the best position to answer questions and provide specific information regarding eligibility and possible participation. Contact information is found in each study listing.

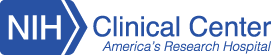

- Join a national research volunteer registry. Health research changes peoples’ lives every day, but many studies end early because there are not enough volunteers. Researchers need both healthy people and those with all types of conditions. Funded by the National Institutes of Health, ResearchMatch is a first-of-its-kind registry that connects research volunteers with researchers across the country. Sign up at ResearchMatch.org .

Making an informed decision

- Informed consent. Before deciding to participate in a study, you will be asked to review an informational document called an informed consent form. This form will provide key facts about the study so that you can decide if participating is right for you. You must sign the informed consent form in order to participate in the study, though it is not a contract — you may still choose to leave the study at any time.

- Risks and benefits. All medical research involves some level of risk to participants. Risks and benefits vary depending on the particular study. To help you make an informed decision, the study team is required to tell you about all known risks, benefits and available alternative health care options.

- Ask questions. If you have questions when deciding to join a research study or at any time during it, ask a member of the study team. If your questions or concerns are not satisfactorily addressed, contact the study's principal investigator, the Mayo Clinic research subject advocate or the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Protecting rights and safety

An independent group, the Mayo Clinic IRB , oversees all Mayo clinical studies that involve people, ensuring research is conducted safely and ethically. Members of the Mayo Clinic IRB include doctors, scientists, nurses and people from the local community.

In addition, Mayo Clinic has a research subject advocate who is independent of all clinical studies and is a resource for research participants. Contact the research subject advocate by email or at 507-266-9372 with questions, concerns and ideas for improving research practices.

Participation costs

Clinical studies may involve billable services and insurance coverage varies by provider.

Clinical studies questions

- Phone: 800-664-4542 (toll-free)

- Contact form

Cancer-related clinical studies questions

- Phone: 855-776-0015 (toll-free)

International patient clinical studies questions

- Phone: 507-284-8884

- Email: [email protected]

Clinical Studies in Depth

Learning all you can about clinical studies helps you prepare to participate.

Diversity in Clinical Trials

Mayo Clinic is keeping diversity and inclusion in focus for all clinical trials and addressing barriers to enrollment.

- Institutional Review Board

The Institutional Review Board protects the rights, privacy, and welfare of participants in research programs conducted by Mayo Clinic and its associated faculty, professional staff, and students.

More about research at Mayo Clinic

- Research Faculty

- Laboratories

- Core Facilities

- Centers & Programs

- Departments & Divisions

- Postdoctoral Fellowships

- Training Grant Programs

- Publications

Mayo Clinic Footer

- Request Appointment

- About Mayo Clinic

- About This Site

Legal Conditions and Terms

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Notice of Privacy Practices

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Manage Cookies

Advertising

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization and proceeds from Web advertising help support our mission. Mayo Clinic does not endorse any of the third party products and services advertised.

- Advertising and sponsorship policy

- Advertising and sponsorship opportunities

Reprint Permissions

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.org," "Mayo Clinic Healthy Living," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

About Research Participation

Resources for the public to learn about participating in research and making informed decisions.

Welcome! The Office for Human Research Protections (OHRP) works to protect the rights, welfare, and wellbeing of volunteers who participate in research supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). One way to further this mission is to provide the public with basic information about research and research participation, so potential volunteers can make informed decisions about participating in research.

Learning about research participation can be challenging. OHRP developed and compiled these resources to help you make the best decisions for you and your loved ones. They answer some common questions and suggest other questions you may want to ask if you are considering participating in research. These materials also may be used by research staff to facilitate and improve the informed consent process.

Check out the links below to watch informational videos, view a list of questions to ask researchers, and find additional resources related to research participation.

These materials are intended for public use and distribution, and we invite you to use and share them freely.

We welcome institutions and companies to link to our About Research Participation (ARP) resources on their websites. Institutions must post links in a such a manner that the audience does not mistake the linking to ARP resources as an endorsement of the institution or company, including its activities, products, services, or facilities, by OHRP, HHS, or the United States Government.

Informational Videos

Watch short videos to learn more about participating in human research

Questions to Ask

View and print questions to ask researchers if you’re considering volunteering for a research study

Protecting Research Volunteers

Learn about the regulations that protect research volunteers

Additional Resources

Access additional resources about human subjects research

Printable Information Materials

Access our library of printable informational materials from the About Research Participation collection. We invite you to print and share them freely

Get a Web Button

Download and post a web button on your website to link to our About Research Participation resources for the general public.

- Department of Health and Human Services

- National Institutes of Health

Program for Healthy Volunteers

What is the clinical research volunteer program (crvp).

Since 1954, the NIH Clinical Center, through the Clinical Research Volunteer Program, has provided an opportunity for healthy volunteers–local, national, and international–to participate in medical research studies (sometimes called protocols or trials). Healthy volunteers provide researchers with important information for comparison with people who have specific illnesses. Every year, nearly 3,500 healthy volunteers participate in studies at NIH.

<< Back to Top >>

What are the benefits of volunteering to take part in clinical research?

Healthy volunteers who take part in clinical research studies at NIH may:

- Receive a thorough physical exam (in some studies)

- Receive compensation for taking part in a study

- Further medical knowledge

- Have the satisfaction of helping someone suffering from a chronic, serious, or life-threatening illness

- Provide important scientific information for developing new disease treatments

Will I be compensated?

The NIH compensates study participants for their time and, in some instances, for the inconvenience of a procedure. There are standard compensation rates for the participant's time; the study's principal investigator determines inconvenience rates. NIH reports compensation of $600 or more to the Internal Revenue Service and sends a "Form 1099-Other Income" to the participant at the end of the year. Please be aware that some or all of that compensation may be garnished if the participant has outstanding debts to the federal or state government.

What kinds of clinical studies are available?

There are about 300 studies available to healthy volunteers. You can find information on these studies on the Clinical Center's home page under Search the Studies . Type in the keywords: healthy and normal.

Studies for both inpatients and outpatients vary in length of time, location (onsite at the NIH Clinical Center, the NIH hospital in Bethesda, Maryland, or at off-site facilities in other areas), age, gender, special requirements, medical exclusions, and procedures. You select the studies that interest you the most and for which you think you would qualify.

Are there any risks?

The NIH staff will explain any risks, requirements, restrictions, or possible side effects before you agree to take part in any study. It is wise and important that you ask them any questions or voice any concerns before you make a decision about taking part.

How are studies approved for volunteer participation?

Before a study is approved for volunteer participation, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration reviews and approves any that involve an investigational drug. If the study involves radiation, the NIH Radiation Safety Committee must review and approve it. These reviews and approvals must take place before any volunteer is invited to participate in a research study.

In addition, physicians, scientists, and lay people rigorously screen all studies for safety, ethics, and need. The clinical director of the supporting institute, that institute's Institutional Review Board, and the Clinical Center director are among with approval authority for each study.

How can I volunteer?

One way to volunteer is to join the registry for the Clinical Research Volunteer Program (CRVP). The CRVP, created in 1995, is a resource that helps match potential research volunteers to clinical research studies at the NIH Clinical Center. To participate in the registry, we'll ask you to provide some basic information and give us permission to share that information with the research teams. If you are a potential match to a study's requirements, the study team will contact you.

How do I enroll myself or my child?

You can contact us at 301-496-4763. Parents or guardians must call to register anyone under 18 years of age.

How can I find studies currently recruiting volunteers?

You can find information about research studies currently recruiting volunteers by viewing the clinical studies website . When searching the web site, type in these words: healthy volunteers and normal volunteers. Call (301) 496-4763 or toll free 1-800-892-3276 for more information.

To determine your eligibility for a study, you may need to complete medical questionnaire forms. An NIH staff member will ask you additional questions. It is critical that you are honest and thorough in providing information about your medical and psychiatric history and about any prescription or nonprescription drugs you take. Accurate information allows investigators to judge whether the study poses any risk to you. You also must let the investigator know of your participation in any other research studies--past, present, or planned.

Before agreeing to participate in any study, the investigator will give you a consent form that explains the study in detail and in everyday, non-medical language. By signing this form, you indicate that you understand the study and volunteer to participate. As a volunteer, you are free to withdraw from, interrupt, or refuse to take part in a study at any time.

NOTE: PDF documents require the free Adobe Reader .

This page last updated on 02/13/2024

You are now leaving the NIH Clinical Center website.

This external link is provided for your convenience to offer additional information. The NIH Clinical Center is not responsible for the availability, content or accuracy of this external site.

The NIH Clinical Center does not endorse, authorize or guarantee the sponsors, information, products or services described or offered at this external site. You will be subject to the destination site’s privacy policy if you follow this link.

More information about the NIH Clinical Center Privacy and Disclaimer policy is available at https://www.cc.nih.gov/disclaimers.html

- Department of Health and Human Services

- National Institutes of Health

FAQs About Clinical Studies

If you are in the process of learning about clinical trials or are considering participating in one, you may be interested in reviewing our Are Clinical Studies for You? page. In addition, we encourage anyone with questions to call the Patient Recruitment Office at 1-800-411-1222 . You may also want to try the " Topics A-Z " tool, an alphabetical index to all visitor- and patient-related subject areas.

- What are clinical studies?

Clinical studies are research studies in which real people participate as volunteers. Clinical research studies are a means of improving our understanding of disease, such as in observational studies, or developing new treatments and medications for diseases and conditions, such as clinical trials, which are evaluating the effects of a biomedical or behavioral intervention on health outcomes. There are strict rules for clinical trials, which are monitored by the National Institutes of Health for the trials it funds, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration more broadly. Some of the research studies at the Clinical Center involve promising new treatments that may directly benefit patients. Understanding Clinical Studies .

- Why should I participate?

The health of millions has been improved because of advances in science and technology, and the willingness of thousands of individuals like you to take part in clinical research. The role of volunteer subjects as partners in clinical research is crucial in the quest for knowledge that will improve the health of future generations. Without your help, the research studies at the Clinical Center cannot be accomplished.

- Will I be compensated?

The NIH may compensate study participants for their time and, in some instances, for the inconvenience of a procedure. There are standard compensation rates for the participant's time; the study's principal investigator determines inconvenience rates.

NIH reports compensation of $600 or more to the Internal Revenue Service and sends a "Form 1099-Other Income" to the participant at the end of the year.

Please be aware that, under U.S. law, some or all of that compensation may be garnished by the U.S. Treasury if the participant has outstanding debts to the federal or state government. The NIH does not have any way of knowing if a volunteer has an outstanding debt to the government and is not told when the U.S. Treasury garnishes compensation. The U.S. Treasury will notify the payee directly in this circumstance.

- What is a "healthy volunteer"?

A volunteer subject with no known significant health problems who participates in research to test a new drug, device, or intervention is known as a "healthy volunteer" or "Clinical Research Volunteer." The clinical research volunteer may be a member of the community, an NIH investigator or other employee, or family members of a patient volunteer. Research procedures with these volunteers are designed to develop new knowledge, not to provide direct benefit to study participants. Clinical research volunteers have always played a vital role in medical research. We need to study healthy volunteers for several reasons: When developing a new technique such as a blood test or imaging device, we need clinical research volunteers to help us define the limits of "normal." These volunteers are recruited to serve as controls for patient groups. They are often matched to patients on such characteristics as age, gender, or family relationship. They are then given the same test, procedure, or drug the patient group receives. Investigators learn about the disease process by comparing the patient group to the clinical research volunteers.

- What are Phase I, Phase II and Phase III studies?

The phase 1 study is used to learn the "maximum tolerated dose" of a drug that does not produce unacceptable side effects. Patient volunteers are followed primarily for side effects, and not for how the drug affects their disease. The first few volunteer subjects receive low doses of the trial drug to see how the drug is tolerated and to learn how it acts in the body. The next group of volunteer subjects receives larger amounts. Phase 1 studies typically offer little or no benefit to the volunteer subjects.

The phase 2 study involves a drug whose dose and side effects are well known. Many more volunteer subjects are tested, to define side effects, learn how it is used in the body, and learn how it helps the condition under study. Some volunteer subjects may benefit from a phase 2 study.

The phase 3 study compares the new drug against a commonly used drug. Some volunteer subjects will be given the new drug and some the commonly used drug. The trial is designed to find where the new drug fits in managing a particular condition. Determining the true benefit of a drug in a clinical trial is difficult.

- What is a placebo?

Placebos are harmless, inactive substances made to look like the real medicine used in the clinical trial. Placebos allow the investigators to learn whether the medicine being given works better or no better than ordinary treatment. In many studies, there are successive time periods, with either the placebo or the real medicine. In order not to introduce bias, the patient, and sometimes the staff, are not told when or what the changes are. If a placebo is part of a study, you will always be informed in the consent form given to you before you agree to take part in the study. When you read the consent form, be sure that you understand what research approach is being used in the study you are entering.

- What is the placebo effect?

Medical research is dogged by the placebo effect - the real or apparent improvement in a patient's condition due to wishful thinking by the investigator or the patient. Medical techniques use three ways to rid clinical trials of this problem. These methods have helped discredit some previously accepted treatments and validate new ones. Methods used are the following: randomization, single-blind or double-blind studies, and the use of a placebo.

- What is randomization?

Randomization is when two or more alternative treatments are selected by chance, not by choice. The treatment chosen is given with the highest level of professional care and expertise, and the results of each treatment are compared. Analyses are done at intervals during a trial, which may last years. As soon as one treatment is found to be definitely superior, the trial is stopped. In this way, the fewest number of patients receive the less beneficial treatment.

- What are single-blind and double-blind studies?

In single- or double-blind studies, the participants don't know which medicine is being used, and they can describe what happens without bias. Blind studies are designed to prevent anyone (doctors, nurses, or patients) from influencing the results. This allows scientifically accurate conclusions. In single-blind ("single-masked") studies, only the patient is not told what is being given. In a double-blind study, only the pharmacist knows; the doctors, nurses, patients, and other health care staff are not informed. If medically necessary, however, it is always possible to find out what the patient is taking.

- Are there risks involved in participating in clinical research?

Risks are involved in clinical research, as in routine medical care and activities of daily living. In thinking about the risks of research, it is helpful to focus on two things: the degree of harm that could result from taking part in the study, and the chance of any harm occurring. Most clinical studies pose risks of minor discomfort, lasting only a short time. Some volunteer subjects, however, experience complications that require medical attention. The specific risks associated with any research protocol are described in detail in the consent document, which you are asked to sign before taking part in research. In addition, the major risks of participating in a study will be explained to you by a member of the research team, who will answer your questions about the study. Before deciding to participate, you should carefully weigh these risks. Although you may not receive any direct benefit as a result of participating in research, the knowledge developed may help others.

- What safeguards are there to protect participants in clinical research?

The following section describes safeguards that protect the safety and rights of volunteer subjects. These safeguards include:

- The Protocol Review Process

- Informed Consent Procedures

- The Patient Representative

- The Patient Bill of Rights

Protocol review. As in any medical research facility, all new protocols produced at NIH must be approved by an institutional review board (IRB) before they can begin. The IRB, which consists of medical specialists, statisticians, nurses, social workers, and medical ethicists, is the advocate of the volunteer subject. The IRB will only approve protocols that address medically important questions in a scientific and responsible manner.

Informed consent. Your participation in any Clinical Center research protocol is voluntary. For every study in which you intend to participate, you will receive a document called "Consent to Participate in a Clinical Research Study" that explains the study in straightforward language. A member of the research team will discuss the protocol with you, explain its details, and answer your questions. Reading and understanding the protocol is your responsibility. You may discuss the protocol with family and friends. You will not be hurried into making a decision, and you will be asked to sign the document only after you understand the nature of the protocol and agree to the commitment. At any time after signing the protocol, you are free to change your mind and decide not to participate further. This means that you are free to withdraw from the study completely, or to refuse particular treatments or tests. Sometimes, however, this will make you ineligible to continue the study. If you are no longer eligible or no longer wish to continue the study, you will return to the care of the doctor who referred you to NIH.

Patient representative. The Patient Representative acts as a link between the patient and the hospital. The Patient Representative makes every effort to assure that patients are informed of their rights and responsibilities, and that they understand what the Clinical Center is, what it can offer, and how it operates. We realize that this setting is unique and may generate questions about the patient's role in the research process. As in any large and complex system, communication can be a problem and misunderstandings can occur. If any patient has an unanswered question or feels there is a problem they would like to discuss, they can call the Patient Representative.

Bill of Rights. Finally, whether you are a clinical research or a patient volunteer subject, you are protected by the Clinical Center Patients' Bill of Rights. This document is adapted from the one made by the American Hospital Association for use in all hospitals in the country. The bill of rights concerns the care you receive, privacy, confidentiality, and access to medical records.

NOTE: PDF documents require the free Adobe Reader .

This page last updated on 02/13/2024

You are now leaving the NIH Clinical Center website.

This external link is provided for your convenience to offer additional information. The NIH Clinical Center is not responsible for the availability, content or accuracy of this external site.

The NIH Clinical Center does not endorse, authorize or guarantee the sponsors, information, products or services described or offered at this external site. You will be subject to the destination site’s privacy policy if you follow this link.

More information about the NIH Clinical Center Privacy and Disclaimer policy is available at https://www.cc.nih.gov/disclaimers.html

Your browser is unsupported

We recommend using the latest version of IE11, Edge, Chrome, Firefox or Safari.

Center for Clinical and Translational Science

For volunteers, researchers need your help consider joining researchmatch.org today, why should you consider joining heading link copy link.

Research affects our everyday lives – ranging from the medicine we take to the health of our families. Becoming a research participant is a gift you give of yourself to benefit your family, your community and the health of people everywhere. Research needs Healthy Volunteers as well as those with medical conditions. All too often important research studies end early because there are too few research participants in the study. At the same time, people are looking for research studies but are having difficult time finding them. As a result, important questions that can affect the health of our community go unanswered. ResearchMatch helps this problem by connecting people who want to participate in studies get connected with the research studies that may be a good ‘match’ for them through its secure, online matching tool.

Who can join? Heading link Copy link

Anyone from the United States can join ResearchMatch regardless of age, ethnicity or health conditions. Volunteers needing assistance and volunteers under the age of 18 may ask a guardian to register on their behalf. Many studies are looking for healthy people of all ages, while some are looking for people with specific health conditions.

How do I join? Heading link Copy link

Go to www.researchmatch.org . It takes between 5-10 minutes to register and anyone residing in the United States can join. You will first answer some basic information about who you are and then have the option of entering in some information about your health.

There is no cost to register as a ResearchMatch Volunteer and all ages and backgrounds are welcome to register. A parent, legal guardian or caretaker may register someone under the age of 19 or an adult that may not be able to enter in their own information. When you become a ResearchMatch Volunteer, you join a pool of thousands of other people across the country that are willing to hear about research studies that might be a good fit for them.

What will happen when I join? Heading link Copy link

After you register, your anonymous (unidentified) ResearchMatch Volunteer profile will become part of a national registry pool.

Approved ResearchMatch researchers search the registry by entering in IRB (Institutional Review Board) approved specific study criteria (age, gender, condition of interest, etc.) to find possible matches for their studies. ResearchMatch then sends an email about a researcher’s study to the ResearchMatch Volunteers who appear to be a good fit for their study.

While the researcher knows that you may be a good match for their study, they do not know who you are until you allow them to see your contact information. If the study is something that the volunteer wishes to learn more about, the Volunteer (you) allow ResearchMatch to release your contact information to the researcher so you can be directly contact by the researcher about the study.

The Volunteer can choose to be part of the study or be removed from a study at any time. The choice is always up to the Volunteer.

And that is how the wonderful ResearchMatch “match” is made!

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

- About our agency home

- Organization

- NOAA organization chart

- Office of Communications

- Office of Education

- The Interagency Meteorological Coordination Office

- Office of General Counsel

- Office of International Affairs

- Office of Legislative & Intergovernmental Affairs

- Acquisition and Grants Office

- Office of the Chief Administrative Officer

- Office of the Chief Financial Officer

- Office of Human Capital Services

- Office of the Chief Information Officer

- Office of Inclusion and Civil Rights

- National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service

- National Marine Fisheries Service

- National Ocean Service

- National Weather Service

- Office of Marine & Aviation Operations

- Office of Oceanic & Atmospheric Research

- Staff Directory

- Mission & vision

- America the Beautiful

- Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

- NOAA Heritage

- NOAA Service Delivery Framework

- NOAA in your state

- New Blue Economy

- Offshore wind energy

- Regional Collaboration Network

- Budget, strategy & performance

- Budget & finance information

- NOAA FY22-26 Strategic Plan

- Work with us

- Commitment to our veterans

- Contracts & grant opportunities

- EEO Policy Statement

- Hiring individuals with disabilities

- Partnership Policy

Volunteer opportunities

- Professional Mariner Career Opportunities

Observe your world. Help the planet. Be a citizen scientist for NOAA.

Help NOAA predict, observe and protect our changing planet by making your own contributions toward a greater understanding of our Earth and its diverse systems. Whether it’s helping count whales in Hawaii or reporting on weather right outside your window, we’ve got a volunteer opportunity for you.

We work with a diverse set of partners to coordinate the citizen science opportunities we offer. See these links below for some of our citizen science programs or search the CitizenScience.gov opportunities catalog to find both national and local NOAA volunteer opportunities.

Trained storm spotters and weather observers support NOAA’s mission of climate monitoring and protecting life and property through accurate weather and water forecasts and warnings.

- SKYWARN® Storm Spotter: Help keep your community safe by volunteering to become a trained severe storm spotter for NOAA's National Weather Service. There is even an easy-to-use online community reporting tool, NWS StormReporter , which promotes the rapid delivery of coastal storm damage information to emergency management personnel and others across New England.

- Daily Weather Observer: Join a national network of Cooperative Observer Program (COOP) volunteers who record and report weather and climate observations to the National Weather Service on a daily basis over the phone or Internet. The National Weather Service provides training, equipment, and additional support through equipment maintenance and site visits. Not only does the data support daily weather forecasts and warnings, but they also contributed toward building the nation’s historic climate record.

- If you like to track rain, hail and snow, you may want to join the Community Collaborative Rain, Hail, and Snow Network offsite link (CoCoRaHS), a nationwide community-based network of volunteers who measure and help map precipitation.

- NOAA’s National Severe Storms Laboratory has a similar program, the Precipitation Identification Near the Ground project (mPING) , where you can report on the type of — but you do not need to measure — precipitation you are encountering at any given time or location. mPING volunteers can spend a little or a lot of time making and recording ground truth observations using the mPING project website or mobile phone app.

Climate and Earth observations

Contribute data to NOAA's National Centers for Environmental Information. NCEI provide access to one of the most significant archives on Earth of comprehensive oceanic, atmospheric and geophysical data.

- CrowdMag app : You can help chart Earth’s magnetic field with your smartphone! After installing the CrowdMag app (Android and iPhone), your phone will automatically send NCEI the data collected from its magnetometer from a sensor already in your phone. The CrowdMag app measures the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field around you. Scientists use observatories, satellites and ship/airborne surveys to track the changes in the magnetic field, but due to gaps in coverage, they are always looking for additional ways to obtain that data. Using the CrowdMag app can help scientists improve magnetic navigation, as well as our understanding of Earth’s magnetic field.

Engage in NOAA’s management of living marine resources through conservation and the promotion of healthy ecosystems.

- Hawaiian Green Sea Turtle Guardian : Protect sea turtles and educate the public on respectful wildlife viewing.

- Dolphin & Whale 911 App: Report dead, injured or entangled marine mammals in the Southeastern U.S. This free apps allows for accurate and timely reporting.

Delve into NOAA’s pursuit to observe, understand, and manage our nation's coastal and marine resources. Opportunities include:

- National Estuarine Reserve Volunteer : Event coordinators, research assistants, and educators are just some of the many more ways you can help NOAA in protecting our nation's coastal protected areas.

- Marine Debris Monitoring and Assessment Project Participant : Support coastal marine debris monitoring efforts used by researchers and NOAA’s Marine Debris Program to assess the impacts and risk posed by marine debris.

- Phytoplankton Monitoring Network: This NOAA initiative promotes a better understanding of harmful algal blooms with help from volunteers who sample local waters twice a month and identify the phytoplankton found.

NOAA National Marine Sanctuary System

Help NOAA Sanctuaries serve as the trustee for a network of underwater parks encompassing more than 600,000 square miles. There are myriad opportunities to do so, including:

Whale Alert offsite link : Whale Alert is a free smart phone app that allows mariners and the public to help decrease the risk of injury or death to whales from ship strikes. Whale Alert depends on your increased participation and willingness to contribute observations taken while whale watching from land and at sea along the coast.

LiMPETS offsite link : Teachers, students and community groups along the coast of California collect rocky intertidal and sandy beach data in the name of science and help to protect our local marine ecosystems.

- Sanctuary Ocean Count: Help collect important population and distribution information on humpback whales around the Hawaiian Islands.

NOAA Sea Grant

Partner with the nation’s top universities in conducting scientific research, education, training, and extension projects within coastal communities. Opportunities include:

Delaware’s Citizen Monitoring Program offsite link : Collect verifiable water quality data to support public policy decisions. This program also aims to increase public participation and support for the protection of Delaware’s water resources.

Red Tide Rangers: offsite link Monitor for the presence of Karenia brevis, a common microscopic, single-celled, photosynthetic organism found in Gulf of Mexico waters that releases toxins known to harm wildlife and people on land and at sea. K. brevis can "bloom" and cause significant discoloration of Gulf and bay waters, commonly known as a “red tide.”

Maine’s Beach Profile Monitoring: offsite link Join 150 community and school volunteers to measure changes in the distribution of sand on the beach. Tracking these changes over long periods (as they have done for 15 years) provides Maine Geological Survey with data to identify seasonal, annual, and even track long-term trends in beach erosion and accretion.

Thank you for your interest in helping advance our mission — we hope you'll volunteer as a NOAA citizen scientist today!

NOAA Fisheries

- Cooperative Shark Tagging Program : The Cooperative Shark Tagging Program is a collaborative effort between recreational anglers, the commercial fishing industry, and NOAA Fisheries to learn more about Atlantic sharks. It is the longest running shark tagging program in the world and NOAA Fisheries' oldest citizen science program. Found a tag or want to get involved?

- California Collaborative Fisheries Research Program offsite link : The California Collaborative Fisheries Research Program is a community-based science program involving university researchers, sportfishing captains and crew, volunteer anglers, and partnerships with conservation and resource management agencies like NOAA Fisheries. Together, this group conducts research to evaluate Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), the status of nearshore fish stocks, and how climate change is impacting marine resources in California.

- Honu Count : Help NOAA track Hawaiian green sea turtles (also called honu) by reporting offsite link the locations of marked turtles. This data helps NOAA better understand honu habitat use patterns, migration, distribution, and survival.

- OceanEYEs offsite link : Help NOAA count fish and improve data used in management of the Hawaiʻi “Deep 7” bottomfish fishery from the comfort of your own home. By analyzing underwater images you will be helping train machine vision algorithms and improving fish stock assessments to help manage these species.

Advertisement

Exploring the Effects of Volunteering on the Social, Mental, and Physical Health and Well-being of Volunteers: An Umbrella Review

- RESEARCH PAPER

- Open access

- Published: 04 May 2023

- Volume 35 , pages 97–128, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Beth Nichol ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7642-1448 1 ,

- Rob Wilson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0469-1884 2 ,

- Angela Rodrigues ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5064-8006 3 &

- Catherine Haighton ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8061-0428 1

7967 Accesses

5 Citations

238 Altmetric

31 Mentions

Explore all metrics

Volunteering provides unique benefits to organisations, recipients, and potentially the volunteers themselves. This umbrella review examined the benefits of volunteering and their potential moderators. Eleven databases were searched for systematic reviews on the social, mental, physical, or general health benefits of volunteering, published up to July 2022. AMSTAR 2 was used to assess quality and overlap of included primary studies was calculated. Twenty-eight reviews were included; participants were mainly older adults based in the USA. Although overlap between reviews was low, quality was generally poor. Benefits were found in all three domains, with reduced mortality and increased functioning exerting the largest effects. Older age, reflection, religious volunteering, and altruistic motivations increased benefits most consistently. Referral of social prescribing clients to volunteering is recommended. Limitations include the need to align results to research conducted after the COVID-19 pandemic. (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42022349703).

Similar content being viewed by others

A Rapid Review of Barriers to Volunteering for Potentially Disadvantaged Groups and Implications for Health Inequalities

Kris Southby, Jane South & Anne-Marie Bagnall

Does volunteering improve the psychosocial well-being of volunteers?

Tai-Wen Chew, Corrine S.-L. Ong, … Eddie M. W. Tong

Volunteer Retirement and Well-being: Evidence from Older Adult Volunteers

Allison R. Russell, Melissa A. Heinlein Storti & Femida Handy

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social prescribing is a person-centred approach involving referral to non-clinical services including those within the third sector (Public Health England, 2019 ), which describes groups or organisations operating independently to government, where social justice is the primary goal (Salamon & Sokolowski, 2016 ). It is an intervention that directs patients with non-medical health needs away from healthcare and towards social means of addressing their needs (Muhl et al., 2022 ), such as support with the social determinants of health including finance and housing, activities around art and creativity, and exercise (Thomson et al., 2015 ). Social prescribing can also involve referring clients to engage in volunteering (Thomson et al., 2015 ; Tierney et al., 2022 ), defined as unpaid work or activity to benefit others outside of the family or household, in which the individual freely chooses to participate (Salamon & Sokolowski, 2016 ). Volunteering, also known as community service in the USA, can be regular and sustained or ad hoc and short term (episodic) (Macduff, 2005 ) and encompasses activity directed towards helping others (civic) (Jenkinson et al., 2013 ), environmental conservation (environmental) (Husk et al., 2016 ), and as part of education (service learning), often accompanied by structured reflection of the voluntary activity (Conway et al., 2009 ).

Unique to other referrals within social prescribing, volunteering may provide a twofold benefit. Volunteering provides clear economic benefits to organisations (NCVO, 2021a ) and acts as a ‘bridge’ of welfare services to deprived communities (South et al., 2011 ). There are also distinct benefits for recipients in comparison with professional help including increased sense of participation, self-esteem and self-efficacy, and reduced loneliness, due to a more neutral and reciprocal relationship (Grönlund & Falk, 2019 ). As utilised by social prescribing, volunteering as an intervention in itself is supported by clear health benefits to the volunteer, particularly improved mental health and reduced mortality (Jenkinson et al., 2013 ). There are many primary studies which find significant positive effects of volunteering on social, physical and mental health, including mortality and health behaviours (Casiday et al., 2008 ; Linning & Volunteering, 2018 ). Furthermore, there is evidence that these benefits occur from adolescence across the lifespan (Mateiu-Vescan et al., 2021 ; Piliavin, 2010 ), although they may increase with age (Piliavin, 2010 ). However, due to the poor quality of this evidence, it is unclear which of the benefits, particularly concerning mental health, predict rather than result from volunteering (Stuart et al., 2020 ; Thoits & Hewitt, 2001 ).

An investigation of the benefits of volunteering can therefore inform on the utility of this practice in improving the health and well-being of clients (Tierney et al., 2022 ) and support a twofold benefit (Mateiu-Vescan et al., 2021 ). Also, establishing the benefits may help retain volunteers within organisations (Mateiu-Vescan et al., 2021 ), as low volunteer retention (Chen et al., 2020 ) has been a key debated issue (Snyder & Omoto, 2008 ; Studer & Schnurbein 2023 ), with suggested solutions including maintaining motivation through opportunities for evaluation and self-development (Snyder & Omoto, 2008 ), improved management of volunteers (Studer & Schnurbein 2023 ), and recognising their value (Studer & Schnurbein 2023 ). However, outcomes of volunteering such as self-efficacy (Harp et al., 2017 ) and sense of connection (Dunn et al., 2021 ) have also been shown to predict retention.

An umbrella review methodology is appropriate to provide a systematic and comprehensive overview of the vast evidence on the benefits of volunteering and to determine which are most supported, making clear and accessible recommendations for research and policy (Pollock et al., 2020 ). An umbrella review can also help establish what works, where, and for whom, through comparison of different settings, volunteering roles, and populations from systematic reviews with different focuses (Smith et al., 2011 ). Thus, it is important that an exploration of the benefits of volunteering consider potential moderators. Umbrella reviews also assess the quality of the included systematic reviews and weight findings accordingly (Smith et al., 2011 ), which may help to establish a causal influence of volunteering. The emerging use of an umbrella review methodology in third sector research has enabled clear recommendations for practice, exploration of moderators and mediators, identification of gaps in the research, and recommendations for future reviews (Saeri et al., 2022 ; Woldie et al., 2018 ).

The aims of this umbrella review were to;

Assess the effects of volunteering on the social, mental and physical health and well-being of volunteers, and;

Investigate the interactions between outcomes and other factors as moderators or mediators of any identified effects.

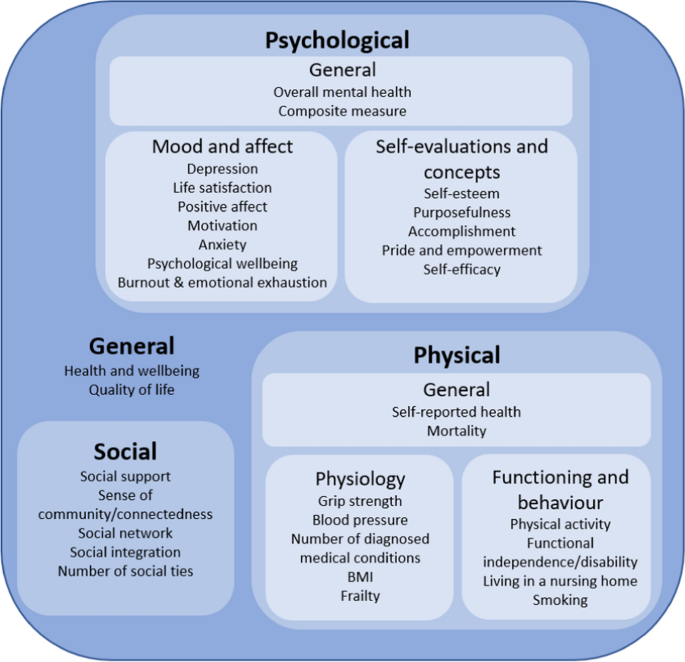

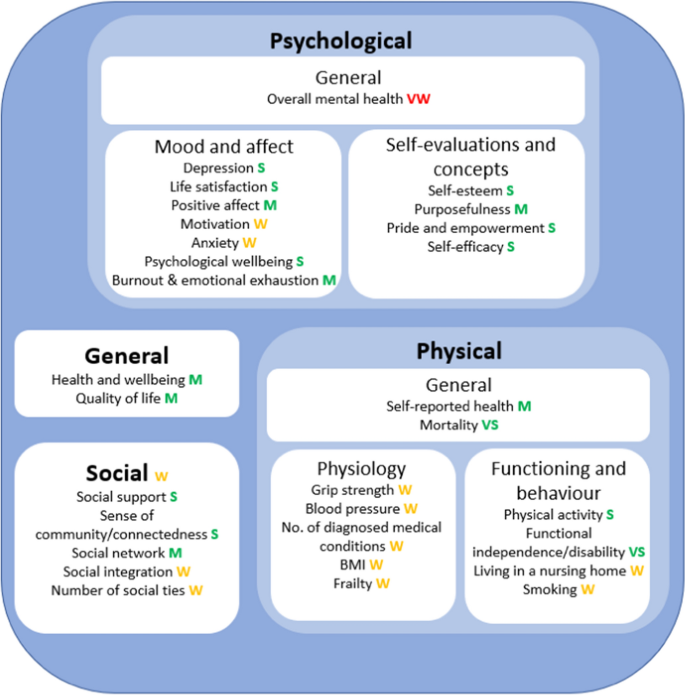

Establishing clear conclusions to these aims helped identify gaps in the literature to direct future research and provided directions to support research and implementation of interventions involving volunteers. Specific outcomes explored within this review are displayed in Fig. 1 .

Outcomes identified and analysed within the current umbrella review, grouped by coding of outcome

This umbrella review was pre-registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Nichol et al., 2022 ) following scoping searches but prior to the formal research (registration number: CRD42022349703). Reporting of the umbrella review methodology followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) (Page et al., 2020 ). Prior to formulating the research question, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Systematic Review Register, and the Open Science Framework Registry were checked for pre-registrations of umbrella reviews of the same or a similar topic. No such umbrella review protocols were retrieved.

Inclusion Criteria

Intervention: volunteering.

Volunteering was defined as conducting work or activity without payment, for those outside of the family or household. Participants of all ages were included. There were no limits by country or organisation or group that the volunteering was for. Although part of the definition of volunteering is that it is sustained (Salamon & Sokolowski, 2016 ), all durations of volunteering were included in this review to ensure a comprehensive search. Additionally, only reviews of volunteering involving some interpersonal contact with other volunteers or recipients were included. Reviews of volunteering in disaster settings such as warzones and aid for natural disasters were excluded, as these represent volunteering in extreme circumstances that is unusual and highly stressful (Thormar et al., 2010 ).

Systematic reviews were required to investigate the effect of volunteering on the volunteer. Reviews were excluded if volunteering was a component of a wider intervention. Reviews only assessing the effect of volunteering on the recipient were also excluded. The distinction between volunteer and recipient was sometimes less clear for reviews assessing the effect of intergenerational programmes. In this case, outcomes were only extracted for the group(s) that were performing work or activity, and no data was extracted from primary studies where neither group were.

The outcome of interest was health and well-being. This was categorised into general, psychological, physical, and social. Of additional interest was the interaction between these effects and with other factors such as demographics or factors associated with volunteering such as duration and type. Outcomes could be self-reported, or objective for physical outcomes (e.g. body mass index (BMI)). Reviews that did not assess effect were excluded, such as those exploring implementation, feasibility, or acceptability of volunteering as an intervention.

Types of Studies

The focus of this umbrella review was on systematic reviews of quantitative studies with or without meta-analyses to assess effect, although reviews of mostly quantitative studies were also included. The adopted definition of a systematic review was a documented systematic search of more than one academic database. Primary studies, reviews of qualitative or mostly qualitative literature, opinion pieces and commentaries were excluded.

Search Strategy

The search was conducted on the 28th July 2022 via 11 databases including EPISTEMONIKOS, Cochrane Database, and PsychARTICLES, ASSIA and the Health Research Premium collection via ProQuest (Consumer Health Database, Health & Medical Collection, Healthcare Administration Database, MEDLINE®, Nursing & Allied Health Database, Psychology Database and Public Health Database). The search was applied to title and abstract and restricted to peer-reviewed systematic reviews published in English, as all reviewers were English language speakers with no translation services available. Initial scoping searches helped to build the search strategy (Supplementary Material 1). To maximise scope, forward and backward citation searching was applied, and the results of scoping searches and further sources such as colleagues and other academics were combined into the final umbrella review.

Study Selection

Search results were exported via a RIS file and uploaded onto Rayyan for screening. Reviewer BN screened all reviews by title and abstract against the inclusion criteria, before screening the remaining (not previously excluded) articles based on full text. Details on independent screening and inter-rater reliability are available in Supplementary material 2.

Quality Appraisal

Quality was assessed using the AMSTAR 2 checklist (Shea et al., 2021 ), which is designed to assess the quality of quantitative systematic reviews of healthcare interventions (Shea et al., 2021 ) and has the highest validity in comparison to other quality assessment tools (Gianfredi et al., 2022 ). Also, the accompanying guidance sheet ensures consistent use across reviewers. The 16 checklist items are presented under Table 1 . Further details on quality appraisal for both the included reviews and primary included studies are available in Supplementary Material 3.

Data extraction and Synthesis

The data extraction form was created with guidance from Cochrane (Pollock et al., 2020 ). To increase transparency, data extraction was completed via SRDR plus, and made publicly available ( https://srdrplus.ahrq.gov//projects/3274 ). Further information on data extraction, including on inter-rater agreement, is available in Supplementary Material 4.

Data Analysis

The strategy of summarising rather than re-analysing the data of the reviews was adopted (Pollock et al., 2020 ). Vote counting by direction of effect was applied (McKenzie & Brennan, 2019 ), relying on the reporting of included systematic reviews. Variables were formed to allow for votes to be counted across reviews (e.g. self-esteem, self-efficacy and pride and empowerment were collapsed due to them regularly being combined by reviews). To test for significance, a two-tailed binomial test was applied with the null assumption that positive effects were of a 50% proportion (McKenzie & Brennan, 2019 ). Given that vote counting does not indicate magnitude of effect, results of meta-analyses are also presented. To estimate the degree of overlap of primary studies between the included reviews, the equation for calculated covered area (CCA) (Pieper et al., 2014 ) was applied. To prevent underestimating overlap, only primary studies addressing the effect of volunteering on the health of the volunteer were included when calculating overlap. Although vote counting also accounts for overlap, the resulting CCA was used as an additional tool for assessing the credibility of conclusions made.

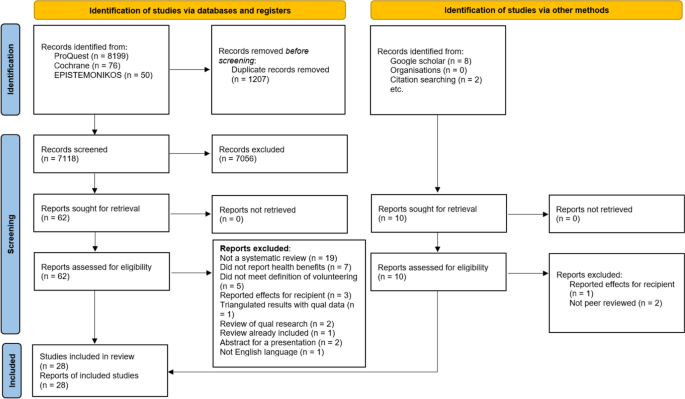

Search Outcomes

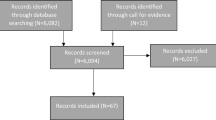

Initially 8325 articles were retrieved, as shown in Fig. 2 . After removal of duplicates, 7118 remained for screening based on title and abstract and 62 articles remained to screen based on full texts, of which 21 reviews were included in the final review. A further 10 articles were retrieved from google scholar and citation searching, of which 7 were included, providing a total of 28 reviews. Excluded articles and the reasons for exclusion are available in Supplementary Material 5. Details on the inter-rater agreement of article screening can be found in Supplementary Material 6.

PRISMA flow diagram of retrieved articles (Page et al., 2020 )

Authors of three included reviews were contacted to gain sufficient information to accurately calculate overlap, for example to separate studies of volunteering from those on prosociality in general (Goethem et al., ( 2014 ); Howard & Serviss, 2022 ; Hui et al., 2020 ). For one review (Goethem et al., ( 2014 )), sufficient information to calculate true overlap was not obtained and thus it was excluded from the calculation of CCA. The excluded review was the only one that focused on adolescents; thus the exclusion is more likely to result in a conservative estimate of overlap rather than an underestimation. Despite this, CCA was 1.3%, indicating slight overlap. The overlap table used to calculate CCA is available from the corresponding author on request.

Methodological Quality of Included Primary Studies

Only 12 of the included reviews assessed primary studies for quality or risk of bias (Chen et al., 2022 ; Filges et al., 2020 ; Gualano et al., 2018 ; Hui et al., 2020 ; Hyde et al., 2014 ; Jenkinson et al., 2013 ; Lovell et al., 2015 ; Manjunath & Manoj, 2021 ; Marco-Gardoqui et al., 2020 ; Milbourn et al., 2018 ; Owen et al., 2022 ; Willems et al., 2020 ). The tools most commonly used to assess study quality were the Effective Public Health Practice Project tool (Lovell et al., 2015 ; Owen et al., 2022 ) and JBI checklists (Manjunath & Manoj, 2021 ; Marco-Gardoqui et al., 2020 ). Those that assessed risk of bias mainly utilised Cochrane tools ROB-2 for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Gualano et al., 2018 ; Jenkinson et al., 2013 ), and ROBINS-I for non-RCTs (Chen et al., 2022 ; Filges et al., 2020 ; Gualano et al., 2018 ). Only two reviews removed studies from the narrative review (Milbourn et al., 2018 ) or meta-analysis (Filges et al., 2020 ) based on quality. Reported study quality varied, but most often was reported as mainly poor quality or high risk of bias.

Methodological Quality of Included Reviews

As shown in Table 1 , the quality of included reviews varied hugely. Only seven reviews scored more than 50% (Chen et al., 2022 ; Filges et al., 2020 ; Gualano et al., 2018 ; Jenkinson et al., 2013 ; Marco-Gardoqui et al., 2020 ; Owen et al., 2022 ; Willems et al., 2020 ). One review was found to be significantly higher quality than the rest (Filges et al., 2020 ). None of the included reviews reported the funding source of the included studies, and most did not report a pre-registration or protocol, or reference to excluded studies.

Characteristics of Included Reviews

The main characteristics of included reviews are displayed in Table 2 . Publication of reviews spanned from 1998 (Wheeler et al., 1998 ) to 2022 (Chen et al., 2022 ; Howard & Serviss, 2022 ; Owen et al., 2022 ), with search dates up to 2020 (Chen et al., 2022 ; Howard & Serviss, 2022 ; Owen et al., 2022 ). Most reviews focused on older people (Anderson et al., 2014 ; Bonsdorff & Rantanen 2011 ; Cattan et al., 2011 ; Chen et al., 2022 ; Filges et al., 2020 ; Gualano et al., 2018 ; Manjunath & Manoj, 2021 ; Milbourn et al., 2018 ; Okun et al., 2013 ; Onyx & Warburton, 2003 ; Owen et al., 2022 ; Wheeler et al., 1998 ), with inclusion criteria ranging from aged over 50 years (Anderson et al., 2014 ; Cattan et al., 2011 ; Manjunath & Manoj, 2021 ; Milbourn et al., 2018 ) to a sample with a mean age of 80 years or above (Owen et al., 2022 ). Only one review focused specifically on adolescents (Goethem et al., ( 2014 )). The number of included primary studies included in the reviews ranged from 5 (Blais et al., 2017 ) to 152 (Kragt & Holtrop, 2019 ), although not all related to the benefits of volunteering. For those that reported on location of included samples, most reviews included participants mostly from the USA (Anderson et al., 2014 ; Blais et al., 2017 ; Bonsdorff & Rantanen 2011 ; Cattan et al., 2011 ; Farrell & Bryant, 2009 ; Filges et al., 2020 ; Giraudeau & Bailly, 2019 ; Gualano et al., 2018 ; Jenkinson et al., 2013 ; Marco-Gardoqui et al., 2020 ; Milbourn et al., 2018 ; Okun et al., 2013 ; Onyx & Warburton, 2003 ; Owen et al., 2022 ; Wheeler et al., 1998 ), followed by North America (Anderson et al., 2014 ; Blais et al., 2017 ; Hyde et al., 2014 ; Jenkinson et al., 2013 ), the UK (Farrell & Bryant, 2009 ; Lovell et al., 2015 ), and Australia (Kragt & Holtrop, 2019 ; Onyx & Warburton, 2003 ). Four reviews focused on intergenerational programmes (Blais et al., 2017 ; Galbraith et al., 2015 ; Giraudeau & Bailly, 2019 ; Gualano et al., 2018 ), two on service learning (Conway et al., 2009 ; Marco-Gardoqui et al., 2020 ), and five on specific roles including crisis line (Willems et al., 2020 ), environmental conservation (Chen et al., 2022 ; Lovell et al., 2015 ), care home work (Blais et al., 2017 ), and water sports inclusion (O’Flynn et al., 2021 ). One review limited the search to volunteering at a frequency less than seasonally (Hyde et al., 2014 ).

Several of the included meta-analyses, whilst employing a systematic search, did not perform any form of narrative synthesis alongside the results of the meta-analyses, meaning information about the characteristics of included studies was missing.

Publication Bias