Progressive Education Philosophy: examples & criticisms

The progressive education philosophy emphasizes the development of the whole child: physical, emotional, and intellectual. Learning is based on the individual needs, abilities, and interests of the student. This leads to students being motivated and enthusiastic about learning.

Progressive philosophy further emphasizes that instruction should be centered on learning by doing, problem-based, experiential, and involve collaboration.

When these elements are included in the learning experience, then students learn practical skills, become engaged in the process, and learning will be maximized.

Progressive Education Definition

The progressive movement has its roots in the writings of philosophers such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Those postulations regarding education influenced other scholars, including Maria Montessori and John Dewey.

The premise of the progressive movement is that traditional educational practices lack relevance to students and that the memorization of facts is ineffective.

As Dewey stated in his book Experience and Education (1938),

“The traditional scheme is, in essence, one of imposition from above and from outside. It imposes adult standards, subject-matter, and methods upon those who are only growing slowly toward maturity” (p. 5-6).

As a response, progressive educators tend to emphasize hands-on, experiential methodologies that enable the construction of knowledge in the mind rather than mere memorization.

Progressive educators also advocate for student autonomy and the cultivation of democratic values and principles by empowering students to make their own decisions as much as possible.

This pedagogy is distinguished by its less authoritarian structure and more collaborative classrooms, with the teacher acting as a guide and collaborator rather than the sole knowledge holder.

Progressive Education Examples

The following pedagogies and pedagogical strategies are often considered commensurate with a progressive education philosophy:

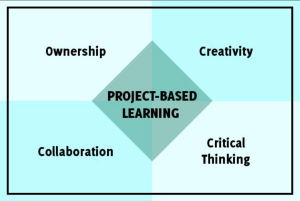

- Project-based learning

- Problem-based learning

- Inquiry-based learning

- Service learning

- Student-centered learning

- Self-directed learning

- Place-based education

- Montessori education

- Community-based learning

- Co-operative learning

- Constructivist learning

- Authentic assessment

- Action research

- Active learning

- Experiential education

- Personalized learning

Real-Life Examples

- A third-grade teacher places cardboard boxes, paper towel tubes, tape, and scissors on a table so the students can design and construct marble mazes.

- Dr. Singh has his students work in small teams to write a program that will block a computer virus attack. The teams then take part in a class competition.

- On the first day of school, Mrs. Jones allows her students to generate a list of classroom rules and learning principles.

- Students in this history class work in small groups to write a short play about an event of their choosing in the Civil Rights movement.

- During a leadership training workshop, the facilitator arranges for pairs of participants to engage in conflict resolution role plays.

- To build teamwork and communication skills, high school students work collaboratively to create PowerPoint presentations about what they learned instead of taking exams.

- Mr. Gonzalez has his students debate the pros and cons of political ideologies on social equality.

- Students in an early childhood education course work in small groups to develop an Action Plan for handling a contagious disease outbreak at a primary school.

- Every term, this high school awards 5 students for exemplifying leadership in the classroom.

- Students in this university Hospitality Management course visit one local 5-star hotel restaurant and conduct a customer service analysis.

Case Studies

1. service-oriented learning: urban farming.

Progressive education can also contain elements of social reconstructionism and the goal of making the world a better place to live. Today’s version of making the world a better place to live encompasses environmental concerns.

For example, food insecurity is a matter that is not evenly distributed across all SES demographics.

Therefore, schools should help students develop a sense of responsibility and build skills that address a broad range of social issues .

The BBC reports that 900 million tons of food is wasted every year. That is more than enough to feed those in need. It is also a problem that has many possible solutions; one of them being Urban farming .

University agriculture majors can coordinate with local disadvantaged communities to implement urban farming solutions. It is possible to grow food on abandoned lots, rooftops, and on the outside walls of buildings and houses.

This is exactly the type of problem-based cooperative learning activity that progressivists support, for several reasons. The students address a pressing societal need and at the same time develop valuable practical skills.

2. Developing Practical Skills: Minecraft

Progressive education means developing practical skills, integrating technology when possible, and tapping into the interests of students. The Minecraft education package meets all of those objectives.

It offers teachers a game-based learning platform that students find very exciting and teachers find very educational. The education edition includes games that foster creativity , problem-solving skills, and cooperative learning.

Teachers in Ireland use Minecraft to demonstrate the connections between history, science, and technology. In one activity , students pretend to be Vikings. They get to build ships and go on raids to establish settlements in faraway lands.

The students learn about archeological reconstruction and how to storyboard their adventures by creating their own digital Viking saga.

As the principal explains, the kids are having great fun, but at the same time they are developing fundamental problem-solving skills , learning to cooperate with each other, and all the while expanding their knowledge base. It’s a win-win-win situation.

3. Student-Centered Learning: Provocations

Teachers at a primary school in Australia have developed a unique student-centered approach that motivates students and allows them to explore their own interests.

The teachers write various learning tasks on cards, called Provocations, and place them on a bulletin board. Students select the tasks they find most interesting and then go to a designated place in the classroom that has been equipped with the necessary materials.

Students then work alone or individually to complete the task. When they’re finished, they write about what they did and convey their reflections in a Learning Journey book.

Afterwards, the teacher and student go through the book and discuss the student’s experience.

The teacher can highlight key learning concepts and the student can consider what they would do differently in the future.

One of the key benefits of this type of activity is that students develop a sense of responsibility for their learning outcomes.

4. Cooperative Learning: Think-Pair-Share

In traditional educational approaches, students are passive recipients of information. They receive and then recall input on exams to demonstrate learning. From a progressive philosophy, this approach fails in so many ways. It does nothing to build practical skills, the level of student motivation is low, and the level of processing is shallow.

Originally proposed by Frank Lyman (1981), Think-Pair-Share (TPS) is just the opposite. It utilizes cooperative learning to improve student engagement, allows students to process information at a much deeper level, and builds teamwork and communication skills.

The instructor presents an issue for students to reflect on individually. Next, pairs discuss their views and arrive at a mutual understanding, which is then shared with the class.

After all pairs have taken a turn, the instructor engages the class with a broader discussion that can allow key concepts and facts to be highlighted.

TPS is a great way to get students involved and build their teamwork and communication skills.

5. Problem-Based Learning: Medical School

One of the key features of progressive education is that students develop practical skills. Problem-based learning (PBL) is often mentioned as a key instructional approach because it helps students develop practical skills and is collaborative. Some of the most respected medical schools in the world have integrated PBL into the curriculum.

Students are presented with a clinical problem. The file may consist of several binders of patient test results and other data. Students then form teams and work together to reach a diagnosis and treatment plan.

A thorough discussion of the patient’s information will reveal the team’s knowledge gaps. The team will then devise a set of learning objectives and path of study to pursue. Each member of the team is allocated specific tasks, the results of which are then shared at the next meeting.

PBL maximizes student engagement, exercises higher-order thinking , and improves collaboration and communication skills. All key goals of progressive education.

1. Practical Skills Development

Progressive education contains many features of other learning approaches such as problem-based learning and experiential learning. These approaches cultivate practical skills such as teamwork, conflict resolution, and communication.

Because students are “doing something” they develop practical skills. For example, in a marketing course, students will design a campaign. In a management course, students will practice giving performance feedback or conducting team-building activities.

These are the types of skills that students will apply later in life at work and in their careers.

2. Self-Discipline and Responsibility

Most activities in progressive education are student-centered. Students are the focus and often this means that they choose their learning goals and work autonomously .

This results in students learning that they are responsible for their learning outcomes. To accomplish tasks, the teacher is not there standing over their shoulder and coaxing them onward. Students must learn how to pace themselves and stay on-task during class. This builds self-discipline and responsibility.

3. Higher-Order Thinking

In a traditional classroom, students passively receive information transmitted from the teacher. The goal is to commit that information to rote memory so that it can be later used to answer multiple-choice questions. This limits the depth and quality of processing students must engage.

Progressive educational activities are just the opposite. Because students must engage in active learning, they process the information much deeper. Because they are required to engage in problem-solving and critical thinking, they must exercise higher-order thinking skills.

1. It Lacks Structure

Not all students flourish in a progressive classroom. Some students benefit from having well-structured lessons that are directed by the teacher. When an activity lacks these components, some students feel uncomfortable and anxious.

However, when there are clear objectives and learning tasks, they feel at ease and motivated. Without structure they can become overwhelmed with uncertainty and reluctant to get started.

2. Clashes with Teachers’ Preferences

Similar to students, not all teachers enjoy working in a progressive school. They find the lack of structure and clarity on learning outcomes difficult to grapple with.

These teachers work much better when they have a firm set of objectives they need their students to achieve; everything is clearly defined.

3. Overwhelming Work Load

The amount of work involved to create several different activities that can suit the variety of learning styles in one classroom can be overwhelming.

It takes a great deal of time just to think of so many meaningful activities, and then, one must prepare a wide assortment of materials; all for a single lesson.

Teachers in many public schools already feel overwhelmed with job demands. Many teachers casually remark that they have not one second of free time from September to June, and that includes weekends. It is hard to justify such a demanding job when taken in the context of the level of commitment required, and of course, a disappointing pay scale.

Progressive education seeks to help students develop skills that they will need throughout their lifespan. By implementing activities that foster problem-solving, higher-order thinking, cooperation, and practical skills, students will graduate well-prepared for their future.

Although these are admirable goals, there are some drawbacks. The demands on teachers are substantial, as it takes a great deal of time to think of and prepare all of the necessary materials for a single lesson.

Moreover, not all students benefit from such an unstructured environment. Some students function better in an atmosphere with clearly defined goals and teacher guidance.

Ultimately, each parent must decide on which approach they consider best for their child and try to locate a school that subscribes to that philosophy.

Hayes, W. (2006). The progressive education movement: Is it still a factor in today’s schools? Rowman & Littlefield Education.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education . Toronto: Collier-MacMillan Canada Ltd.

Lyman, F. (1981). The responsive classroom discussion: The inclusion of all students. In A. Anderson (Ed.), Mainstreaming digest (pp. 109-113). University of Maryland College of Education.

Macrine, Sheila. (2005). The promise and failure of progressive education-essay review. Teachers College Record, 107 , 1532-1536. https://10.1177/016146810510700705

Wright, G. B. (2011). Student-centered learning in higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23(3), 93–94.

Dave Cornell (PhD)

Dr. Cornell has worked in education for more than 20 years. His work has involved designing teacher certification for Trinity College in London and in-service training for state governments in the United States. He has trained kindergarten teachers in 8 countries and helped businessmen and women open baby centers and kindergartens in 3 countries.

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Dave Cornell (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/dave-cornell-phd/ Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Chris Drew (PhD)

This article was peer-reviewed and edited by Chris Drew (PhD). The review process on Helpful Professor involves having a PhD level expert fact check, edit, and contribute to articles. Reviewers ensure all content reflects expert academic consensus and is backed up with reference to academic studies. Dr. Drew has published over 20 academic articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education and holds a PhD in Education from ACU.

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Positive Punishment Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 25 Dissociation Examples (Psychology)

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link 15 Zone of Proximal Development Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) #molongui-disabled-link Perception Checking: 15 Examples and Definition

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Chapter 6: Progressivism

Dr. Della Perez

This chapter will provide a comprehensive overview of Progressivism. This philosophy of education is rooted in the philosophy of pragmatism. Unlike Perennialism, which emphasizes a universal truth, progressivism favors “human experience as the basis for knowledge rather than authority” (Johnson et. al., 2011, p. 114). By focusing on human experience as the basis for knowledge, this philosophy of education shifts the focus of educational theory from school to student.

In order to understand the implications of this shift, an overview of the key characteristics of Progressivism will be provided in section one of this chapter. Information related to the curriculum, instructional methods, the role of the teacher, and the role of the learner will be presented in section two and three. Finally, key educators within progressivism and their contributions are presented in section four.

Characteristics of Progressivim

6.1 Essential Questions

By the end of this section, the following Essential Questions will be answered:

- In which school of thought is Perennialism rooted?

- What is the educational focus of Perennialism?

- What do Perrenialists believe are the primary goals of schooling?

Progressivism is a very student-centered philosophy of education. Rooted in pragmatism, the educational focus of progressivism is on engaging students in real-world problem- solving activities in a democratic and cooperative learning environment (Webb et. al., 2010). In order to solve these problems, students apply the scientific method. This ensures that they are actively engaged in the learning process as well as taking a practical approach to finding answers to real-world problems.

Progressivism was established in the mid-1920s and continued to be one of the most influential philosophies of education through the mid-1950s. One of the primary reasons for this is that a main tenet of progressivism is for the school to improve society. This was sup posed to be achieved by engaging students in tasks related to real-world problem-solving. As a result, progressivism was deemed to be a working model of democracy (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.2 A Closer Look

Please read the following article for more information on progressivism: Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find. As you read the article, think about the following Questions to Consider:

- How does the author define progressive education?

- What does the author say progressive education is not?

- What elements of progressivism make sense, according to the author?

Progressive education: Why it’s hard to beat, but also hard to find

6.3 Essential Questions

- How is a progressivist curriculum best described?

- What subjects are included in a progressivist curriculum?

- Do you think the focus of this curriculum is beneficial for students? Why or why not?

As previously stated, progressivism focuses on real-world problem-solving activities. Consequently, the progressivist curriculum is focused on providing students with real-world experiences that are meaningful and relevant to them rather than rigid subject-matter content.

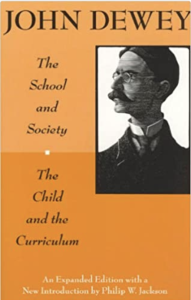

Dewey (1963), who is often referred to as the “father of progressive education,” believed that all aspects of study (i.e., arithmetic, history, geography, etc.) need to be linked to materials based on students every- day life-experiences.

However, Dewey (1938) cautioned that not all experiences are equal:

The belief that all genuine education comes about through experience does not mean that all experiences are genuinely or equally educative. Experience and education cannot be directly equated to each other. For some experiences are mis-educative. Any experience is mis-education that has the effect of arresting or distorting the growth or further experience (p. 25).

An example of miseducation would be that of a bank robber. He or she many learn from the experience of robbing a bank, but this experience can not be equated with that of a student learning to apply a history concept to his or her real-world experiences.

Features of a Progressive Curriculum

There are several key features that distinguish a progressive curriculum. According to Lerner (1962), some of the key features of a progressive curriculum include:

- A focus on the student

- A focus on peers

- An emphasis on growth

- Action centered

- Process and change centered

- Equality centered

- Community centered

To successfully apply these features, a progressive curriculum would feature an open classroom environment. In this type of environment, students would “spend considerable time in direct contact with the community or cultural surroundings beyond the confines of the classroom or school” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 74). For example, if students in Kansas were studying Brown v. Board of Education in their history class, they might visit the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka. By visiting the National Historic Site, students are no longer just studying something from the past, they are learning about history in a way that is meaningful and relevant to them today, which is essential in a progressive curriculum.

- In what ways have you experienced elements of a progressivist curriculum as a student?

- How might you implement a progressivist curriculum as a future teacher?

- What challenges do you see in implementing a progressivist curriculum and how might you overcome them?

Instruction in the Classroom

6.4 Essential Questions

- What are the main methods of instruction in a progressivist classroom?

- What is the teachers role in the classroom?

- What is the students role in the classroom?

- What strategies do students use in a progressivist classrooms?

Within a progressivist classroom, key instructional methods include: group work and the project method. Group work promotes the experienced-centered focus of the progressive philosophy. By giving students opportunities to work together, they not only learn critical skills related to cooperation, they are also able to engage in and develop projects that are meaningful and have relevance to their everyday lives.

Promoting the use of project work, centered around the scientific method, also helps students engage in critical thinking, problem solving, and deci- sion making (Webb et. al., 2010). More importantly, the application of the scientific method allows progressivists to verify experi ence through investigation. Unlike Perennialists and essentialists, who view the scientific method as a means of verifying the truth (Webb et. al., 2010).

Teachers Role

Progressivists view teachers as a facilitator in the classroom. As the facilitator, the teacher directs the students learning, but the students voice is just as important as that of the teacher. For this reason, progressive education is often equated with student-centered instruction.

To support students in finding their own voice, the teacher takes on the role of a guide. Since the student has such an important role in the learning, the teacher needs to guide the students in “learning how to learn” (Labaree, 2005, p. 277). In other words, they need to help students construct the skills they need to understand and process the content.

In order to do this successfully, the teacher needs to act as a collaborative partner. As a collaborative partner, the teachers works with the student to make group decisions about what will be learned, keeping in mind the ultimate out- comes that need to be obtained. The primary aim as a collaborative partner, according to progressivists, is to help students “acquire the values of the democratic system” (Webb et. al., 2010, p. 75).

Some of the key instructional methods used by progressivist teachers include:

- Promoting discovery and self-directly learning.

- Integrating socially relevant themes.

- Promoting values of community, cooperation, tolerance, justice, and democratic equality.

- Encouraging the use of group activities.

- Promoting the application of projects to enhance learning.

- Engaging students in critical thinking.

- Challenging students to work on their problem solving skills.

- Developing decision making techniques.

- Utilizing cooperative learning strategies. (Webb et. al., 2010).

6.5 An Example in Practice

Watch the following video and see how many of the bulleted instructional methods you can identify! In addition, while watching the video, think about the following questions:

- Do you think you have the skills to be a constructivist teacher? Why or why not?

- What qualities do you have that would make you good at applying a progressivist approach in the classroom? What would you need to improve upon?

Based on the instructional methods demonstrated in the video, it is clear to see that progressivist teachers, as facilitators of students learning, are encouraged to help their stu dents construct their own understanding by taking an active role in the learning process. Therefore, one of the most com- mon labels used to define this entire approach to education to- day is: constructivism .

Students Role

Students in a progressivist classroom are empowered to take a more active role in the learning process. In fact, they are encourage to actively construct their knowledge and understanding by:

- Interacting with their environment.

- Setting objectives for their own learning.

- Working together to solve problems.

- Learning by doing.

- Engaging in cooperative problem solving.

- Establishing classroom rules.

- Evaluating ideas.

- Testing ideas.

The examples provided above clearly demonstrate that in the progressive classroom, the students role is that of an active learner.

6.6 An Example in Practice

Mrs. Espenoza is an 6th grade teacher at Franklin Elementary. She has 24 students in her class. Half of her students are from diverse cultural- backgrounds and are receiving free and reduced lunch. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, Mrs. Espenoza does not use traditional textbooks in her classroom. Instead, she uses more real-world resources and technology that goes beyond the four walls of the classroom. In order to actively engage her students in the learning process, she seeks out members of the community to be guest presenters in her classroom as she believes this provides her students with an way to interact with/learn about their community. Mrs. Espenoza also believes it is important for students to construct their own learning, so she emphasizes: cooperative problem solving, project-based learning, and critical thinking.

6.7 A Closer Look

For more information about progressivism, please watch the following videos. As you watch the videos, please use the “Questions to Consider” as a way to reflect on and monitor your own learnings.

• What additional insights did you gain about the progressivist philosophy?

• Can you relate elements of this philosophy to your own educational experiences? If so, how? If not, can you think of an example?

Key Educators

6.8 Essential Questions

- Who were the key educators of Progressivism?

- What impact did each of the key educators of Progressivism have on this philosophy of education?

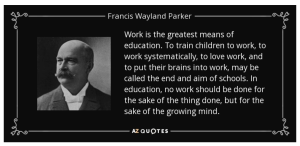

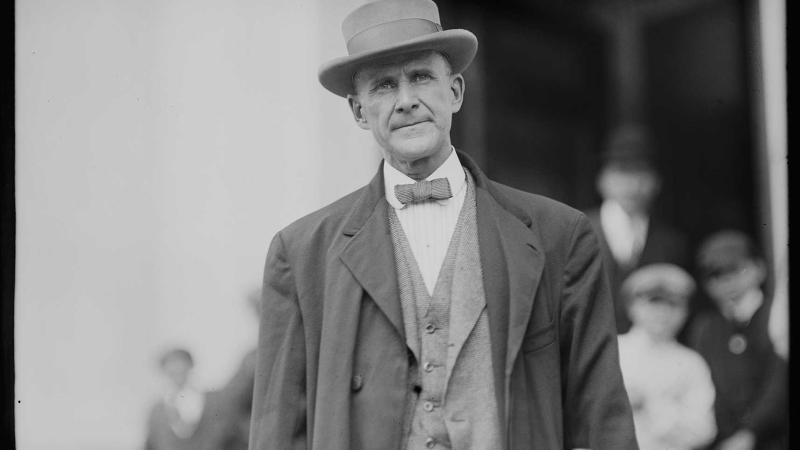

The father of progressive education is considered to be Francis W. Parker. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts, and later became the head of the Cook County Normal School in Chicago (Webb et. al., 2010). John Dewey is the American educator most commonly associated with progressivism. William H. Kilpatrick also played an important role in advancing progressivism. Each of these key educators, and their contributions, will be further explored in this section.

Francis W. Parker (1837 – 1902)

Francis W. Parker was the superintendent of schools in Quincy, Massachusetts (Webb, 2010). Between 1875 – 1879, Parker developed the Quincy plan and implemented an experimental program based on “meaningful learning and active understanding of concepts” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 1). When test results showed that students in Quincy schools outperformed the rest of the school children in Massachusetts, the progressive movement began.

Based on the popularity of his approach, Parker founded the Parker School in 1901. The Parker School

“promoted a more holistic and social approach, following Francis W. Parker’s beliefs that education should include the complete development of an individual (mental, physical, and moral) and that education could develop students into active, democratic citizens and lifelong learners” (Schugurensky, 2002, p. 2).

Parker’s student-centered approach was a dramatic change from the prescribed curricula that focused on rote memorization and rigid student disciple. However, the success of the Parker School could not be disregarded. Alumni of the school were applying what they learned to improve their community and promote a more democratic society.

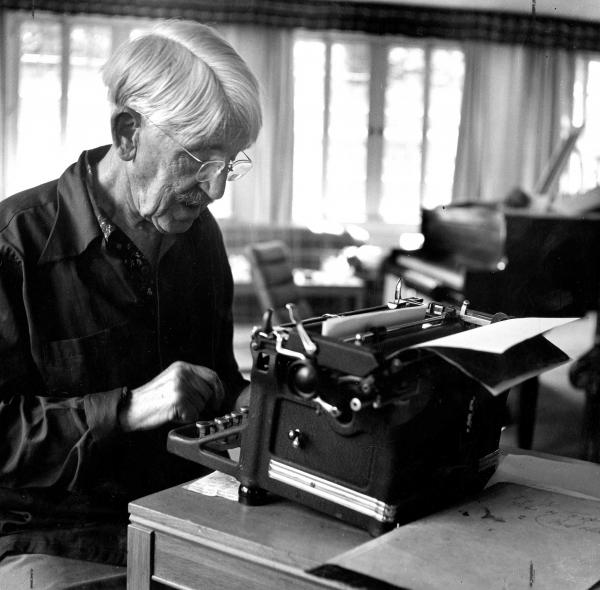

John Dewey (1859 – 1952)

John Dewey’s approach to progressivism is best articulated in his book: The School and Society

(1915). In this book, he argued that America needed new educational systems based on “the larger whole of social life” (Dewey, 1915, p. 66). In order to achieve this, Dewey proposed actively engaging students in inquiry-based learning and experimentation to promote active learning and growth among students.

As a result of his work, Dewey set the foundation for approaching teaching and learning from a student-driven perspective. Meaningful activities and projects that actively engaging the students’ interests and backgrounds as the “means” to learning were key (Tremmel, 2010, p. 126). In this way, the students could more fully develop as learning would be more meaningful to them.

6.9 A Closer Look

For more information about Dewey and his views on education, please read the following article titled: My Pedagogic Creed. This article is considered Dewey’s famous declaration concerning education as presented in five key articles that summarize his beliefs.

My Pedagogic Creed

William H. Kilpatrick (1871-1965)

Kilpatrick is best known for advancing progressive education as a result of his focus on experience-centered curriculum. Kilpatrick summarized his approach in a 1918 essay titled “The Project Method.” In this essay, Kilpatrick (1918) advocated for an educational approach that involves

“whole-hearted, purposeful activity proceeding in a social environment” (p. 320).

As identified within The Project Method, Kilpatrick (1918) emphasized the importance of looking at students’ interests as the basis for identifying curriculum and developing pedagogy. This student-centered approach was very significant at the time, as it moved away from the traditional approach of a more mandated curriculum and prescribed pedagogy.

Although many aspects of his student-centered approach were highly regarded, Kilpatrick was also criticized given the diminished importance of teachers in his approach in favor of the students interests and his “extreme ideas about student- centered action” (Tremmel, 2010, p. 131). Even Dewey felt that Kilpatrick did not place enough emphasis on the importance of the teacher and his or her collaborative role within the classroom.

Reflect on your learnings about Progressivism! Create a T-chart and bullet the pros and cons of Progressivism. Based on your T-chart, do you think you could successfully apply this philosophy in your future classroom? Why or why not?

Chapter 6: Progressivism Copyright © 2023 by Dr. Della Perez. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

29 Progressive Education

William J. Reese is the Carl F. Kaestle W.A.R.F. and Vilas Research Professor of educational policy studies and history at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- Published: 13 June 2019

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Progressive education emerged from a variety of reform movements, especially romanticism, in the early nineteenth century. Reflecting the idealism of contemporary political revolutions, it emphasized freedom for the child and curricular innovation. The Swiss educator Johann Pestalozzi established popular model schools in the early 1800s that emphasized teaching young children through familiar objects, such as pebbles and shells, and not from textbooks. A German romantic, Friedrich Froebel, studied with Pestalozzi and invented the kindergarten, which spread worldwide. Progressive education mostly influenced pedagogy in the early elementary school grades. Over the course of the twentieth century, however, progressive ideals survived at other levels of schooling. Innovative teaching and curricular programs appeared in different times and places in model school systems, laboratory schools on college campuses, open classrooms, and alternative high schools. The greatest barriers to student-centered instruction included the widespread use of standardized testing and the prevalence of didactic teaching methods.

“ Progressive education ” remains a familiar phrase in the lexicon of educational historians but commonly eludes a precise definition or agreement about its origins, nature, or impact upon schools. By the first half of the nineteenth century, however, a variety of educators and writers in Europe and America claimed that a “new education” would inevitably replace outmoded instructional methods and curricula. Offering a new way of thinking about the nature of children and how to teach them, men and women on both sides of the Atlantic drew inspiration from a range of sources, promising a revolution in the history of childhood. By the early twentieth century, the phrase “new education” was gradually replaced by “progressive education.” Often reduced to slogans such as “learning by doing” or “experiential learning,” progressive education found expression in many schools worldwide through curriculum reforms and new teaching practices. It often found a home in teacher training programs. Yet the cluster of ideas embraced by many progressives usually failed to transform schools as they anticipated. By the early twenty-first century, standardized testing, didactic instructional methods, and classroom competition remained common in many nations.

In a speech at Teachers College, Columbia University, in 1959, the historian Lawrence A. Cremin claimed that “the early progressives knew better what they were against than what they were for.” 1 He was referring to twentieth-century American educational reformers who more easily criticized conventional schools than agreed about how to implement “natural” pedagogical methods or to meet the needs of the “whole child.” Cremin’s insights can also be applied to many European and American activists in the early nineteenth century who complained about schools and called for a “new education.” They found existing pedagogical practices and the overall treatment of children in the larger society abhorrent, much like reformers today who still dream of greater well-being for all and more child-friendly schools where freedom for teacher and pupil takes precedence.

Throughout the Western world in the early 1800s, critics of schools and traditional childrearing practices could easily find grounds for optimism and despair. The American and French revolutions had toppled kings and promised greater equality and opportunity for more citizens. But child labor, abysmal poverty, slavery, the suppression of women’s rights, and other ancient evils endured despite growing movements for abolition, rising literacy rates and investment in schools, and an appreciation for women’s roles as mothers and teachers, part of the humanitarianism of the age. Advocates of the “new education” attacked time-honored school practices, including pupil memorization of textbooks, Bibles, and other reading materials, enforced when necessary by the rod. Influenced by political revolution, the Enlightenment, and romanticism, these reformers never formed a coherent movement, but they nevertheless shared fundamental beliefs, including a radical critique of conventional educational theories and practices. 2

Historical Roots and Nineteenth-Century Developments

In Europe and America, reformers were influenced by an array of thinkers who came before them. This ensured that advocates of the “new education” held eclectic views while calling for school improvements and greater attention to children’s welfare. While often deeply spiritual and Christian, they rejected the well-established religious claim that children were born in sin and thus evil by nature; traditionally, stubborn wills had to be broken, like horses, through physical restraint and harsh discipline. Some reformers drew upon the ideas of John Amos Comenius, a Moravian minister who wrote that young children especially learned best from familiar, age-appropriate materials, including visual sources. Even more influential, the English writer John Locke changed pedagogical theory forever by insisting that education above all—not inheritance—decisively shaped children’s development; this elevated human agency, highlighted the uniqueness of every individual, and encouraged additional speculation on effective childrearing.

More controversial but equally revolutionary were the various works of Jean Jacques Rousseau, whose political radicalism and religious views horrified the established leaders of church and state. Rousseau also fueled the growth of romanticism, which emphasized the innocence of children and the failures of adult institutions. Like Locke’s writings, Rousseau’s Emile (1762) was translated into many languages and challenged tradition; it became famous for its depiction of a pedagogically rich, imaginary world in which a male tutor raised a child through “natural” means. Advocating experiences over books, Rousseau urged adults to see the world through the eyes of a child, a revolutionary concept if taken literally, since schools had long been teacher- and textbook-, not child-centered. Rousseau’s insight—to treat children as children—seems commonsensical today but was revelatory at the time.

Criticisms of schools abounded in the nineteenth century, and the champions of the “new education” aimed to establish education and schooling on a more rational, humanitarian, child-sensitive foundation. Guidance came not only from luminaries such as Comenius, Locke, and Rousseau but also from the immediate romantic stirring of the period. In the late eighteenth century in England, the religious poet William Blake penned his Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794), which contrasted the purity and innocence of youth with their destruction by the baleful influence of church and state, including schools. Blake wrote sympathetically about the plight of chimney sweeps and the urban poor and condemned the use of corporal punishment. Like many romantics, William Wordsworth lamented the soul-destroying effects of formal education. “Heaven lies about us in our infancy!” he claimed in 1804; soon enough the “Shades of the prison-house begin to close / Upon the Growing Boy.” In the United States, transcendentalists such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, a Unitarian minister, similarly linked childhood and innocence, and he applauded European educators and theorists who demanded more humane treatment of children, whether within families, at the workplace, or at school. The child, he wrote in Nature (1836), was a “perpetual Messiah,” calling adults back to an innocent state. 3

On both sides of the Atlantic, numerous citizens echoed the views of poets, philosophers, liberal clerics, and other advocates of the “new education.” Schools force-fed students arcane knowledge from textbooks; pupils memorized and recited lessons like parrots; teachers threatened pupils with physical punishment instead of making learning more appealing. While schools, according to many romantics, were often undesirable places, leading figures of the Enlightenment had also concluded that people could behave rationally and, contrary to orthodox Christian belief, promote progress. Individuals were not predestined to heaven or hell, and some reformers dreamed of establishing a heaven on earth. At the least they hoped to improve the lives of the most helpless individuals in society, including the young.

By the late eighteenth century, the publication of encyclopedias, dictionaries, and other means to advance learning beyond the elite classes seemed to portend an age of educational advance. “After bread, education is the first need of the people,” said the French revolutionary George Jacques Danton in 1792, and less revolutionary figures also spoke of a coming millennium of peace and prosperity. Thanks to technological innovations that reduced publishing costs by the 1820s, newspapers and magazines reached a wider readership; they often reported on the latest educational ideas. The desirability of education and school improvements thus drew sustenance from a variety of sources, including rising literacy rates in many Western nations.

It was one thing to condemn schools, another thing entirely to improve them. Some romantics, such as Blake, doubted that schools could ever play a positive role in society, but the nineteenth century became an age of institution building, including asylums, prisons, workhouses, and schools. Many of them did not advance the cause of humanity, and historians have long criticized their failings. But two European visionaries, Johann Pestalozzi and Friedrich Froebel, contributed to the hopefulness of the times and offered innovative ways to undermine hide-bound schools. Pestalozzi would forever be associated with “object teaching,” while Froebel became synonymous with his invention, the kindergarten. They became central to what contemporaries called the “new education,” a romantic, “natural” approach to teaching and learning. Reformers who called themselves progressives in the twentieth century stood upon their shoulders.

Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi was born in Switzerland and was initially swept up in the fervor of the French Revolution. His life transformed after reading Emile , he established model schools that taught many orphans, the victims of the continental wars. Pestalozzi became a sainted figure, his image sketched and painted, his writings widely quoted, his schools visited by many educational pilgrims. Children, he argued, learned naturally by handling familiar objects. Pebbles could be used to teach arithmetic, and the close study of nature revealed the mysteries of science, geography, and history. As Rousseau had written, educators should see the world through children’s eyes and introduce lessons to them in a natural way, drawing upon their immediate environment. Young children learned from things, not words, as Pestalozzi’s followers often said. Books, especially textbooks, represented adult-centered understandings of the world, far removed from children’s experiences. Children, so active outside of school, were expected to sit still in classrooms and often whipped when they failed to conform to the unrealistic expectations of teachers. Pestalozzi imagined a different approach. He idealized peasant mothers, deemed superior in teaching the young compared with schoolmasters wed to textbooks and corporal punishment. Children needed a harmonious education, one where adults in all settings treated them humanely, educating the hand, the heart, and the mind through pleasant means. 4

Pestalozzi came of age in an era without extensive systems of state-financed schools. Like many famous teachers, he apparently had a charismatic personality, attracting pupils and followers alike, while few teachers anywhere enjoyed such allure. Turning ideas conceived by a charismatic individual into everyday practices in systems of education raised a serious question: Was it possible? Pestalozzians quarreled over how to interpret his writings, which they often read in translation in newspapers and magazines or heard about in lectures. This produced obvious problems in describing a genuinely Pestalozzian school, though most utilized a method called “object teaching,” which was packaged in Europe and America in training manuals and textbooks with step-by-step lesson plans in the basic subjects. In the United States they were often written by urban school superintendents far removed from the rural worlds that had shaped the great master’s schools and teaching with things, not words.

Prominent educational leaders helped popularize Pestalozzian ideals beyond Europe. For example, Horace Mann, America’s leading reformer in the late 1830s and 1840s, praised them in his writings and lectures. He and like-minded educators drew attention to the Swiss master in editorials and articles in leading periodicals, including the Common School Journal , which Mann edited. Saying schools should adopt more “natural” pedagogical methods was nevertheless easier than changing time-tested practices. While object teaching certainly became part of teacher training in the United States, historians have discovered that many pupils at the newly established normal schools had to concentrate on mastering the common school subjects before they might learn about alternative pedagogical methods. And most teachers seemed to teach as they had been taught, which meant mastering textbooks, not exploring sylvan fields.

Facing growing numbers of pupils in New York, Boston, and other cities, mainstream educators tried to bring order out of chaos, so they implemented not a flexible but a more uniform curriculum, set by administrators and approved by the local school board. Cities also built larger, better age-graded schools after midcentury. They increasingly hired women as elementary teachers, whose salaries were lower than males’ and often had classrooms with fifty to sixty pupils. Paying attention to each individual was very difficult, if not impossible, and teachers often could not model instruction on the scripted lessons in instructional manuals. More schools purchased globes and blackboards, and teachers sometimes taught subject matter with the aid of “objects” such as watches, coins, and rock collections; many schools, which were often overcrowded, nevertheless lacked the resources to buy expensive teaching aids. Reports thus circulated in Europe and America that schools remained textbook-based and teacher-, not child-centered. Traditional practices were difficult to dislodge.

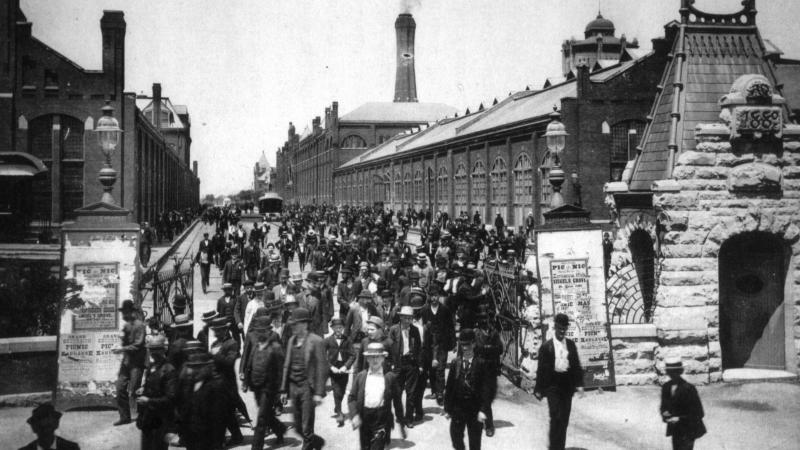

Occasionally a charismatic individual carried the banner of the “new education” forward and demonstrated its practical character. Probably the best example in the United States was Colonel Francis W. Parker. Parker was a popular lecturer, writer, and administrator, the living embodiment of the “new education.” Having himself traveled to Europe to study education, he criticized rote methods of instruction, corporal punishment, and competitive written tests, the last becoming more common in urban schools after the 1850s. Between 1875 and 1880, Parker, a Civil War veteran, became nationally renowned for his achievements as school superintendent in Quincy, Massachusetts. He helped create a model public school system, where teachers apparently eschewed excessive memorization and recitation. The Quincy school board appointed teachers who shared his views on child-centered pedagogy. Forward-thinking educators and aspiring teachers flocked to Quincy, seeking guidance. But Parker’s tenure was short. Called the “father of progressive education” by none other than John Dewey, a close friend, Parker later headed a well-known teacher training college in Chicago. 5

The great question from the time of Pestalozzi and Parker to the present was whether teachers would embrace “natural” and child-centered methods when they themselves had often succeeded in old-fashioned schools and found jobs in similar types of institutions. Of course, the “new education” should not be judged only by whether it changed schools wholesale in any particular community or nation; at times, some of what Pestalozzi’s followers and other innovators had in mind made a visible dent in the system.

Indeed many urban schools lacking charismatic leadership or full support for the “new education” adopted some aspects of object teaching after the 1860s. On the edges of the curriculum, for example, “learning by doing” found expression in a range of manual training classes in many towns and cities. Nature study also became popular, supplementing textbook-based science instruction. A remarkable collection of photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston at the turn of the twentieth century demonstrates that many white and black schools in Washington, D.C., offered classes in dancing, cooking, and manual training, sponsored field trips, and initiated laboratory courses to enliven instruction. But detailed studies of the curriculum in the post–Civil War era show that urban and rural schools nationwide mostly focused on the basic subjects of reading, writing, and arithmetic in the elementary grades, wherein most pupils were enrolled, and on core academic subjects taught in traditional ways to the smaller numbers of pupils enrolled in high school. Many books and magazine articles in the 1890s noted that, even when districts adopted object teaching or manual training, they occupied only a small part of the school day. Most classes resembled the past. Textbooks reigned supreme, and memorization, recitation, and increasingly written examinations were common. Visitors to manual training classes sometimes found teachers lecturing, testifying to the firm grip of tradition. 6

In 1900 the U.S. Commissioner of Education, William T. Harris, a staunch supporter of an academic curriculum who frequently disparaged the “new education,” said that teachers were basically conservative. Most had succeeded as students in traditional classrooms. Writing in the journal Education , Harris explained that children were typically “full of caprice and wayward impulses,” and teachers endeavored to socialize them to adult norms. Teaching, he concluded, “is the most conservative of all occupations, excepting always the ministry. For the teacher has to deal with the unformed, undeveloped human being, and educate it into the manners and customs of civilized life, and above all open it for the storehouse of the wisdom of the human race.” Such statements rattled every progressive. Harris recognized that textbooks might be boring, but he regarded them as tools of democracy; an informed citizenry, as the Founders of the nation believed, needed access to the same basic knowledge. Textbooks were even more important to the many pupils who had dull, uninspiring teachers.

Harris was no stranger to debates about what knowledge or teaching methods merited a place at school. A Connecticut Yankee, Harris had dropped out of Yale and moved west, rising up the ranks to become the much-heralded superintendent of the St. Louis public schools between 1868 and 1880. As advocates of the “new education” there as elsewhere urged schools to become more child-friendly, Harris, a Hegelian philosopher and admirer of German culture, rejected romantic claims about the value of object teaching. But he notably embraced a key innovation that had originated in Europe: kindergartens.

Kindergartens were first established in the United States in the 1850s and were often found in urban areas populated with German immigrants, who were well represented on the St. Louis school board. While Harris doubted that kindergarten methods would transform the elementary grades as many reformers desired, he built a model system that attracted visitors from around the nation. A local training school prepared hundreds of women teachers, who ultimately spread the kindergarten gospel to many communities. The “child’s garden,” Harris believed, would not usher in a paradise of learning, but it could help adjust children from the informality of the home to the stricter demands of elementary school.

Kindergartens, like manual training, engaged children in numerous activities. They provided living proof that the “new education” could enter school systems otherwise committed to teacher authority and student mastery of textbooks. Children in kindergartens sat in a circle, not in fixed rows, and in moveable chairs, not bolted-down seats. Kindergartens promoted cooperative learning, stressed the educational value of structured play, and provided a sequenced set of lessons employing objects (balls, string, and so forth) and not books as the central means of instruction. Photographs of kindergartens reveal their home-like, middle-class atmosphere, with pleasant pictures adorning the walls and plants and flowers brightening the room. Women dominated in kindergarten teaching and supervision and helped popularize the reform in articles, books, and speeches. Women’s reputation for gentle treatment of little children—especially compared with men’s treatment—made them central to this aspect of the “new education.” 7

Friedrich Froebel, the German inventor of the kindergarten, had apprenticed in one of Pestalozzi’s schools, and the “child’s garden” became one of the most popular, long-lasting innovations associated with the “new education.” Initially banned in Prussia because of its links to political radicalism, the kindergarten spread to all corners of the world, though the followers of Froebel, like those of Pestalozzi, often disagreed about specific aspects of his educational philosophy and “gifts and occupations,” his richly symbolic curricular exercises. Rival professional associations in many nations debated how to organize kindergartens. By the late nineteenth century, only a small percentage of America’s school systems had funded them, but kindergartens were also found in settlement houses, orphan asylums, and private schools. City systems faced the challenge of paying teachers and constructing new buildings for a burgeoning population. In many large cities such as New York and Chicago, thousands of children in the 1890s could not find a seat in public elementary schools, which remained overcrowded. Providing universal access to new programs in early childhood education was prohibitively expensive in many school districts and inconceivable in some. But kindergartens were here to stay, as the “new education” traveled from Europe to America and other nations.