The Oral Health in America Report: A Public Health Research Perspective

ESSAY — Volume 19 — September 8, 2022

Jane A. Weintraub, DDS, MPH 1 ( View author affiliations )

Suggested citation for this article: Weintraub JA. The Oral Health in America Report: A Public Health Research Perspective. Prev Chronic Dis 2022;19:220067. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.220067 .

PEER REVIEWED

Introduction

Data needed, health disparities and social determinants of health, individual and community relationships, scientific advances and equitable distribution, educational opportunities, acknowledgments, author information.

In December 2021, the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, released its landmark 790-page report, Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges (1). This is the first publication of its kind since the agency’s first Oral Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General described the silent epidemic of oral diseases in 2000 (2). This new, in-depth report, an outstanding resource, had more than 400 expert contributors. Its broad scope is exemplified by its 6 sections ( Box ), each of which includes 4 chapters: 1) Status of Knowledge, Practice, and Perspectives; 2) Advances and Challenges; 3) Promising New Directions; and 4) Summary. In this essay, I provide a public health research perspective for viewing the report, identify some advances and gaps in our knowledge, and raise research questions for future consideration.

Box. Section Titles, Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges (1)

1. Effect of Oral Health on the Community, Overall Well-Being, and the Economy

2A. Oral Health Across the Lifespan: Children

2B. Oral Health Across the Lifespan: Adolescents

3A. Oral Health Across the Lifespan: Working-Age Adults

3B. Oral Health Across the Lifespan: Older Adults

4. Oral Health Workforce, Education, Practice, and Integration

5. Pain, Mental Illness, Substance Use, and Oral Health

6. Emerging Science and Promising Technologies to Transform Oral Health

A recurring theme in the report is the need for many types of data, from microdata — the molecular, nanoparticle level — to macrodata — the population and global level. Data are needed to guide public health policies and programs at the federal, state, and local levels. Future research using big data from multiple sources (eg, community health needs assessments, surveillance systems, GIS mapping, electronic health records, practice-based research networks) will provide timely, population-based information to evaluate and drive changes to policy and delivery systems and oral health advocacy efforts.

This new report includes descriptive national data from 3 cycles of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). To continue monitoring national oral health surveillance data and trends, oral health data need to be included routinely in NHANES and in other large national studies. Too often, questions about oral health are missing from surveys, or clinical oral health data are not collected. For example, very little about oral health was included as part of the planned data collection protocol for the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program. This program aims to collect health information from 1 million people (3). Local and state data are often outdated, incomplete, or unavailable. Most oral health data are cross-sectional and are useful for studying trends and associations, but population-based longitudinal data to study causality and the effectiveness of interventions and policies are sparse.

How does oral health care improve other health conditions? Proprietary claims data from insurance companies (4) show the inter-relationship between treatment of periodontal disease and systemic conditions, but secondary data analysis has many limitations and confounding factors. Clinical trials show that periodontal treatment improves glycemic control among people with diabetes (5), but long-term outcome assessments are lacking. We need more answers to convince policy makers and payers about the importance of including comprehensive adult oral health services in publicly financed programs such as Medicaid, which is currently lacking in many states, and Medicare, where those services are missing altogether.

Many examples of substantial oral health disparities and inequities are presented in Section 1 of the report. For some conditions and population groups, little improvement has been made, especially among adults and seniors. Section 1 also describes the adverse social, economic, and national security effects of poor oral health, barriers to care, social and commercial determinants of oral health, and related common risk factors. More than the clinical data collected in a typical dental history is needed to understand social determinants and employ local and upstream interventions. The report suggests obtaining social histories from patients to get information about where people live, learn, work, and play. For example, to learn about socioeconomic status, diet, and medications, we want to know not only “What’s in your wallet,” (as touted in a frequent television advertisement) but what’s in your refrigerator? What’s in your medicine cabinet? Telehealth has given clinicians a look inside patients’ homes. Collaboration with social workers, home health aides, and visiting nurses could inform us even more about the home environment. With integrated electronic medical and dental patient records, oral health professionals and medical colleagues can share information. Barriers to integration and assessment of population health outcomes affect many dentists who still use paper records or software specific to dental care that lacks diagnostic codes and interoperability with other health care records systems (6).

The report highlights the need for more information about adolescents and older adults and other understudied population groups. Section 1 describes many diverse, vulnerable populations (eg, people with special health care needs, low health literacy, mental illness, substance abuse disorders; victims of structural racism) who all need to be included in oral health research. Non-English speakers and hard-to-reach populations that have physical and/or financial barriers to traditional dental care are less likely to be recruited and represented in clinical trials, making results less generalizable and interventions less applicable. The applied research agenda being developed by the American Association of Public Health Dentistry (7) and the “Consensus Statement on Future Directions for the Behavioral and Social Sciences in Oral Health,” which is based on an international summit (8), are helpful in setting research and methodologic priorities, including qualitative, implementation, and health systems research.

Knowledge about the interrelationships between oral and systemic health has greatly expanded since the 2000 report. About 60 adverse health conditions have now been shown to be associated with oral health (1), which is part of the rationale for the integration of oral health and primary care. Research will advance our understanding of the mechanisms by which oral and systemic conditions are affected by upstream environmental and social factors, epigenetic factors, and the aging process, both individually and communally. For example, how do external exposures change our microbiomes? Our oral microbiome may be exposed to air containing Sars-CoV-2, water containing protective fluoride, or many kinds of food, beverages, medications, illicit substances, smoked products, and sometimes the biome of close personal contacts. How does the health of a community’s high caries risk groups change with policies such as a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages, Medicaid reimbursement changes, or health promotion efforts to improve oral health literacy and dietary behaviors? To what extent will increased application of value-based health care reimbursement with emphasis on disease prevention, early detection, and minimally invasive care improve oral health? Will the World Health Organization’s addition of dental products (eg, fluoride toothpaste, low-cost silver diamine fluoride, glass ionomer cement) to its Model List of Essential Medicines (9) increase their use to prevent and treat dental caries for under-resourced populations without access to conventional high-cost dental care?

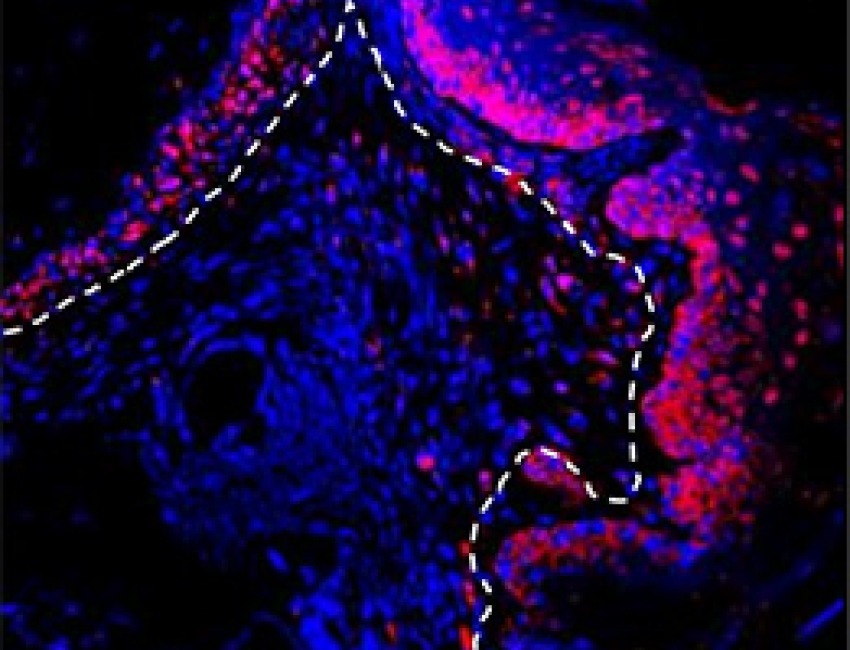

The report’s Section 6 describes many exciting advances in biology, biomimetic dental materials, and technology. Rapid advances in salivary diagnostics are providing information about early, abnormal changes in remote organ systems in the body. Advanced imaging techniques and artificial intelligence can be used for early diagnosis of oral lesions before they are visible to the human eye. The validity and accuracy of these techniques need careful evaluation. Can these earlier clinical end points be used to shorten the length of expensive clinical trials? Guide new preventive strategies? At what point do providers intervene with early preventive or therapeutic strategies instead of letting the body heal itself?

Will populations at greatest risk for disease and the greatest barriers to accessing dental care be able to benefit from early intervention? Every intervention has a cost. If access to new prevention and therapeutic discoveries is not equitable, will health disparities worsen? We need community engagement in the research process and the tools from many disciplines to measure and facilitate the best outcomes. The national Oral Health Progress and Equity Network’s blueprint for improving oral health for all includes 5 levers to advance oral health equity: “amplify consumer voices, advance oral health policy, integrate dental and medical [care], emphasize prevention and bring care to the people” (10).

Who will analyze all these data mined from many micro and macro sources, and who will interpret the data? Health learning systems and complex software algorithms are being developed to provide automated diagnostic information. Data analysts with knowledge of these and other sophisticated tools and modeling approaches are needed.

The dental, oral, and craniofacial research and practice communities increasingly need to be part of interdisciplinary research and educational programs with opportunities for collaboration and learning. Federally qualified health centers and look-alikes are good sites for medical–dental integration, but many of these facilities do not provide dental care.

More positions are needed for dental public health specialists who can lead advocacy efforts, interdisciplinary teams of researchers, clinicians, and community partners and conduct research. For example, the new Dental Public Health Research Fellowship at the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research will provide more intensive research training to further advance dental public health and population-based research. Mechanisms are needed to promote, facilitate, and reward sharing of research and training resources across disciplines in our competitive environment.

Public health perspectives are an important part of interdisciplinary approaches to guide, conduct, and apply research and implement policies to improve oral health. Preventive approaches exist as do barriers to their dissemination and implementation. To prevent disease and improve population oral and overall health, systems change and policy reform are needed along with scientific advances across the research spectrum, more population-level data and analysis, and community participatory engagement. I am optimistic that the next Oral Health in America report will describe fewer inequities and more progress toward oral health for all.

This article is based on a presentation made in the webinar, Oral Health in America — Advances and Challenges: Reading the Report through a Research Lens , sponsored by the American Association for Dental, Oral, and Craniofacial Research. The author received no financial support for this work and has no conflicts of interest to declare. The statements made are those of the author. No copyrighted materials were used in this article.

Corresponding Author: Jane A. Weintraub, DDS, MPH, R. Gary Rozier and Chester W. Douglass Distinguished Professor, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Adams School of Dentistry, Department of Pediatric and Public Health, Koury Oral Health Sciences Building, Suite 4508, Chapel Hill, NC 27599-7450. Telephone: (919) 537-3240. Email: [email protected] .

Author Affiliations: 1 University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Adams School of Dentistry and Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- National Institutes of Health. Oral health in America: advances and challenges. Bethesda (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research; 2021. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2021-12/Oral-Health-in-America-Advances-and-Challenges.pdf

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Oral health in America: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health; 2000. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/sites/default/files/2017-10/hck1ocv.%40www.surgeon.fullrpt.pdf

- US Department of Health and Human Services. All of Us Research Hub Research Projects Directory. Updated 2/23/2022. Accessed February 23, 2022. https://www.researchallofus.org/research-projects-directory/?searchBy=workspaceNameLike&directorySearch=oral

- Jeffcoat MK, Jeffcoat RL, Gladowski PA, Bramson JB, Blum JJ. Impact of periodontal therapy on general health: evidence from insurance data for five systemic conditions. Am J Prev Med 2014;47(2):166–74. CrossRef PubMed

- Baeza M, Morales A, Cisterna C, Cavalla F, Jara G, Isamitt Y, et al. Effect of periodontal treatment in patients with periodontitis and diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Appl Oral Sci 2020;28:e20190248. CrossRef PubMed

- Atchison KA, Rozier RG, Weintraub JA. Integration of oral health and primary care: communication, coordination and referral. Washington (DC): National Academy of Medicine; 2018. Accessed February 21, 2022. https://nam.edu/integration-of-oral-health-and-primary-care-communication-coordination-and-referral/

- Banava S, Reynolds J, Naavall S, Frantsve-Hawley J. Introducing the AAPHD 5-year research agenda. Presentation, National Oral Health Conference, April 12, 2022; Fort Worth, Texas.

- McNeil DW, Randall CL, Baker S, Borrelli B, Burgette JM, Gibson B, et al. Consensus statement on future directions for the behavioral and social sciences in oral health. J Dent Res 2022;101(6):619–22. CrossRef PubMed

- World Health Organization. Executive summary: the selection and use of essential medicines 2021: report of the 23rd WHO Expert Committee on the selection and use of essential medicines, virtual meeting, 21 June–2 July 2021. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization. Accessed April 9, 2022. https:// www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPSEML-2021.01

- Oral Health Progress and Equity Network. OPEN blueprint for structural improvement. Accessed April 22, 2022. https://openoralhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/OPEN_FLS_BlueprintOverview_F.pdf

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors’ affiliated institutions.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- Open access

- Published: 03 October 2022

Quantitative data collection approaches in subject-reported oral health research: a scoping review

- Carl A. Maida 1 ,

- Di Xiong 1 , 2 ,

- Marvin Marcus 1 ,

- Linyu Zhou 1 , 2 ,

- Yilan Huang 1 , 2 ,

- Yuetong Lyu 1 , 2 ,

- Jie Shen 1 ,

- Antonia Osuna-Garcia 3 &

- Honghu Liu 1 , 2 , 4

BMC Oral Health volume 22 , Article number: 435 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4844 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

This scoping review reports on studies that collect survey data using quantitative research to measure self-reported oral health status outcome measures. The objective of this review is to categorize measures used to evaluate self-reported oral health status and oral health quality of life used in surveys of general populations.

The review is guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) with the search on four online bibliographic databases. The criteria include (1) peer-reviewed articles, (2) papers published between 2011 and 2021, (3) only studies using quantitative methods, and (4) containing outcome measures of self-assessed oral health status, and/or oral health-related quality of life. All survey data collection methods are assessed and papers whose methods employ newer technological approaches are also identified.

Of the 2981 unduplicated papers, 239 meet the eligibility criteria. Half of the papers use impact scores such as the OHIP-14; 10% use functional measures, such as the GOHAI, and 26% use two or more measures while 8% use rating scales of oral health status. The review identifies four data collection methods: in-person, mail-in, Internet-based, and telephone surveys. Most (86%) employ in-person surveys, and 39% are conducted in Asia-Pacific and Middle East countries with 8% in North America. Sixty-six percent of the studies recruit participants directly from clinics and schools, where the surveys were carried out. The top three sampling methods are convenience sampling (52%), simple random sampling (12%), and stratified sampling (12%). Among the four data collection methods, in-person surveys have the highest response rate (91%), while the lowest response rate occurs in Internet-based surveys (37%). Telephone surveys are used to cover a wider population compared to other data collection methods. There are two noteworthy approaches: 1) sample selection where researchers employ different platforms to access subjects, and 2) mode of interaction with subjects, with the use of computers to collect self-reported data.

The study provides an assessment of oral health outcome measures, including subject-reported oral health status and notes newly emerging computer technological approaches recently used in surveys conducted on general populations. These newer applications, though rarely used, hold promise for both researchers and the various populations that use or need oral health care.

Peer Review reports

A fundamentally different approach is currently needed to address the oral health of populations worldwide namely by considering the perspective of patients or populations and not only dental professionals' views [ 1 ]. It seems increasingly necessary to integrate the self-reported perceptions of oral health, as they can complete or even replace clinical measures of dental status in surveys of populations. Indeed, such subjective measures are easy to use in large-scale populations and can provide a broader health perspective as compared to clinically determined measures of dental status alone [ 2 , 3 ]. Since the topic is broad, this scoping review sets out to identify methods employed in population surveys that discussed self-reported perceptions of oral health, and the extent to which new computer-oriented technological approaches are being incorporated in the research methods.

The literature on oral health and dental-related scoping and systematic reviews includes studies that use specific populations in terms of disease or clinical conditions, treatments, political or social status and typically do not explore oral health status outcome measures [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. These studies only occasionally provide perspectives on general populations. A review by Mittal et al. identifies dental Patient-Reported Outcomes (dPROs), and dental Patient Reported Outcome Measures (dPROMs) related to oral function, oral-facial pain, orofacial pain and psychosocial impact [ 16 ]. The study affords a valuable and extensive review of self-reported oral health and quality of life measures, many of which are found in this paper. This scoping review, then, seeks approaches used in subject-reported surveys, including those with general populations, which may broaden the perspective on oral health outcome measures.

The objective of this review is to categorize measures used to evaluate self-reported oral health status and oral health quality of life used in surveys of general populations.

This work is implemented following the framework of scoping reviews [ 17 , 18 , 19 ] and is presented according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting of Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR), as listed in Additional file 1 : Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist [ 20 ]. Additional file 5 : Glossary of Terms provides definitions for the important terms used across the paper.

Search strategy and data sources

A health science librarian assisted in the development of a search strategy that identified papers concerning subject-reported oral health status surveys. The search terms consisted of three broad categories, including survey methods, subject-reported outcomes, and oral health and disease (see Additional file 2 : Search Terms for the full list of search strings). The search comprised peer-reviewed journal articles, conference proceedings and reviews with at least one keyword from each of three aspects. Four online databases: Ovid Medline, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Reviews and Trials were used. In addition, a manual search used similar keywords for the gray literature achieved on MedRxiv. The search focused on peer-reviewed papers written in English and published between 2011 to September 2021. Publications in the last decade were reviewed to investigate the extent to which different methods were being used and the trends that occurred during this period. The final search was completed on September 29, 2021. Using the current decade provides a period where there is considerable interest in non-clinical oral health status outcome measures and the potential for examining technological innovation. All references were imported for review and appraisal. Duplicates were identified using Mendeley (Mendeley, London, UK) and manually verified. After removing the duplicates, data were tabulated in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) for recording screening results and data charting.

Study inclusion criteria

Studies that did not meet with the research objective were excluded using a screening tool (Additional file 3 : Search Tool). First, the titles and abstracts of publications were screened to determine if studies conducted quantitative surveys, and to assess if self-reported and/or proxy-reported OHS was a primary objective. Only surveys with more than three questions that related to OHS were considered. Studies with secondary analysis were excluded because the data collection methods were normally not developed as part of the research and were developed previously. Papers whose sole purpose was to validate well-known measures of oral health were also rejected since the intent was not to assess the OHS of a population. Literature reviews were likewise excluded, as were papers describing results from focus groups and other qualitative studies. Papers whose objectives were to validate measures or predict specific oral disease entities, such as caries or gingival bleeding, rather than overall OHS. Studies primarily focusing on general health status or other systemic diseases instead of OHS were eliminated. Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) or quasi RCT studies that tested an active agent (e.g., therapy, experiment, and medicine) were excluded because the main research purpose was a comparison of treatment rather than an assessment of subject-reported OHS.

The research team performed the secondary screening through a full-text review. We dropped papers with full text missing or not in English. Then, we screened the available full-text works using a similar set of inclusion criteria aforementioned and further excluded papers without information about data collection methods.

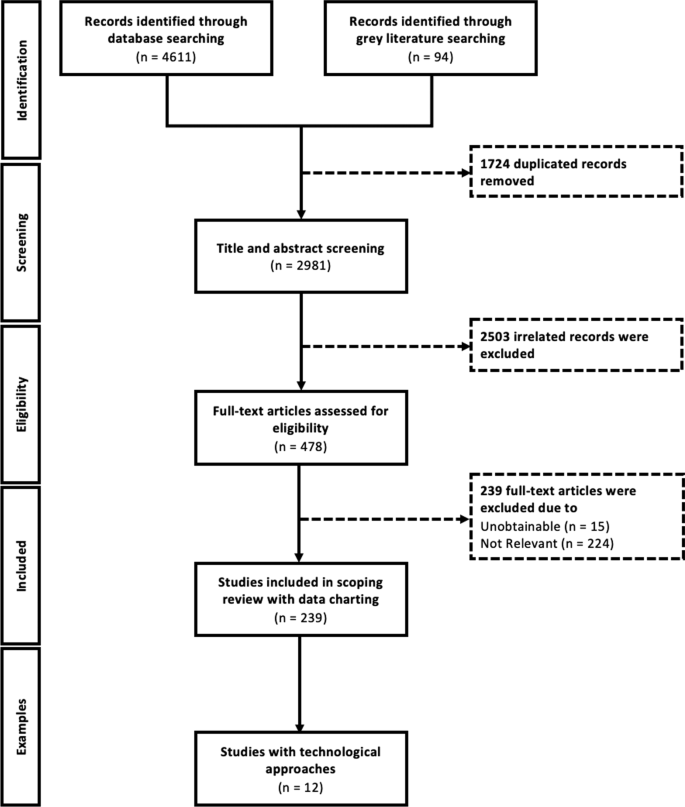

Selection strategies

Figure 1 outlines the review process utilizing the PRISMA-ScR framework. The title-and-abstract screening was completed by a researcher (D.X.) against the inclusion criteria using a screening tool (Additional file 3 : Search Tool). To check for reliability and consistency, one of the researchers (L.Z.) randomly screened 10% of articles independently and compared the inclusion decisions. Given the result of title-and-abstract screening, two researchers (L.Z. and Y.H.) verified the eligibility of the remaining articles independently through full-text review. Inclusion discrepancies were resolved by an additional researcher (D.X.).

PRISMA framework with additional examples

Data extraction

The data charting form (Additional file 4 : Data Charting Form) consists of quantitative and qualitative variables for the data collection methods and their characteristics, such as outcome measures, use of assistive devices/tools or data sources, report type, and so on. The form has been pre-tested by two project staff (C.M. and M.M.) before being utilized. Two researchers (Y.H. and L.Z.) extracted data using the form. Two project staff (C.M. and M.M.) collaborated to review the charted study characteristics and the discrepancies have been addressed through discussion.

Data synthesis and analysis

The scoping review synthesizes the research findings based on dimensions and attributes of major oral health survey data collection methods using descriptive and content analyses. The review provides an overview of various related data collection methods in the recent literature, which refer to the quantitative methods to collect information from a pool of respondents, and the trends in using these new technological approaches, which involve computerized modes, Internet-supported devices and interactive web technologies. Through the literature review, we locate four major types of data collection methods: in-person, Internet-based, telephone-based, and mail-in based approaches.

Screening and study selection

After removing duplicates, the initial search revealed 2981 articles from four online databases for title-and-abstract screening; 2503 of which were excluded after being examined against the inclusion criteria. The interrater reliability of screening was measured by Kappa agreement as 0.94 (95% confidence interval [0.89, 0.99]) for title-and-abstract screening, which implies almost perfect agreement [ 21 ]. After full-text reviewing and excluding 239 articles, we summarized and categorized the remaining 239 studies based on the pre-tested data charting form. In addition, we identified 12 studies with various technological approaches to data collection. Figure 1 presented the PRISMA Framework used for this scoping review.

General characteristics of included studies

Table 1 presents various characteristics of the 239 articles that meet inclusion criteria that were published from 2011 to September 2021. Fifty-six percent of the papers are published in dental journals. About 40% of the papers are published in journals from the Asia-Pacific and Middle East region (APAC), and only 8.4% are from North America (NA). The majority of studies (69%) focus on the general population. Most (88.6%) of the studies use in-person surveys. Around two-thirds of the studies invite and recruit participants from the study sites, e.g., schools, clinics, and hospitals. Some studies recruit participants by having the research team visit communities (16%) or by sampling directly from a database (13%). In the latter case, participants are selected using probability and/or non-probability sampling methods, including convenience sampling (52%), simple random sampling (12%), and stratified sampling (12%). Most studies (193 or 80.8%) investigate self-reported outcomes. Dental examinations accompany the survey in 54% of the studies, while 32% of studies do not use any clinical exam or records. The data charting details are listed in Additional file 4 : Data Charting Form.

Characteristics of data collection methods

The four main data collection methods include in-person (N = 206, 86.2%), mail-in (N = 15, 6.3%), Internet-based (N = 6, 2.5%), and telephone-based (N = 3, 1.3%) surveys. The characteristics of the various data collection methods are summarized in Table 2 .

The majority of the studies using in-person surveys have high response rates with an average of 90.6%. Those studies using in-person survey methods represent half 55.8% of the studies employ face-to-face interviews, while 35.4% used a paper-and-pencil approach. Participants for 58.7% of the studies are recruited directly from clinics [ 22 ], hospitals [ 23 ], and community care centers [ 24 ]. For those sites with electronic records, additional data sources are directly linked to the survey, for example, clinical dental exams with visual components (e.g., X-ray [ 25 ] and pictures [ 26 ]) and medical records [ 23 , 27 , 28 ]. Moreover, different qualitative assessments (e.g., Malocclusion Assessment [ 22 ] and Masticatory Performance Test [ 24 , 29 ]) are captured in patient progress notes.

The mail-in survey method is used by 15 studies and may be more cost-effective than in-person delivery, though these were the two main sources, via post (80%) and by carriers (20%). Mail-in surveys have a relatively high response rate averaging 72%, especially when children or other respondents bring surveys home to complete. Similar to in-person surveys, mail-in surveys can incorporate additional resources, such as photographs and explanations of clinical conditions and treatments [ 30 , 31 ].

Only six studies are identified as using an Internet-based survey, mainly through computer-assisted web interviews (4 studies), and email (2 studies). Three papers employ direct recruitment and another three papers recruit participants through websites and databases. The average response rate is as low as 36.7% for this method with small sample sizes with a median of 259 participants.

Three studies use a telephone survey method covering large populations compared to other survey methods with more responders on average. Two of these studies recruit participants through an existing database, and all surveys used interviewers. Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviews (CATI) [ 32 ] and Voice Response Systems [ 33 ] which are commonly used in industry are not found in the studies.

In addition to the data collection methods, we further categorize the measures found in the 239 articles. Table 3 presents the frequencies and percentages of the various self-reported outcome measures. The three basic approaches are oral health impact measures [ 34 ], functional measures [ 34 ], and self- or proxy-ratings of OHS, with the terms defined in Additional file 5 : Glossary of Terms. These are used as single measures or in combination. The Oral Health Impact Profile-14 (OHIP-14) is the most prevalent single measure with 69 papers and 29% overall, of which 25 papers are about child impact, representing 10% of the total number of selected papers. The Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index (GOHAI), a functional measure, is second with 21 papers and 9% overall. The GOHAI is the first among the studies on the elderly. There are also two adolescent papers representing 9% of the functioning category. The self- or proxy-rating of OHS has 18 single-measure papers representing 8% of these articles. Of these, 12 or 80% are children's measure's, representing 5% of all selected papers.

There is a total of 63 papers using more than one type of measure. Either combining functional and impact measures (36 and 15%) or self-rating OHS and one or more of the other measures (27 or 11%). The group of single impact measures is 50% of the overall and also represents where two or more measures were used. The single measure, GOHAI, based on function is only 9% of all measures but also played a role in combination with other measures. Finally, the self-reported OHS as a single measure represents 8% of the studies. Its role is mainly in combination with other measures and represented another 15% of the articles. In total. children's oral health measures form a considerable portion of the self-reported oral health outcome research papers, representing 16% of all studies. There are additional studies where children’s measures are used in combination with adults.

Currently, the use of technological approaches emerged in the field of survey research to improve the quality and quantity of data collection. After reviewing and charting all qualified 239 articles, twelve studies that employ technological approaches are summarized in Table 4 .

This scoping review provides an overview of data collection methods used for subject-reported surveys to measure oral health outcomes. Studies are characterized by four survey methods (in-person, mail-in, Internet-based, and telephone) and by summarized dimensions and attributes of data collection for each method, such as technological approaches, survey population or sampling methods. Studies typically employ in-person surveys and more studies were conducted in Asia-Pacific and Middle East countries than in any other world region. Most studies recruit participants directly from study sites. Both probability and non-probability sampling methods employ typically convenience sampling, simple random sampling, and stratified sampling. Studies that achieve the highest response rate on average use in-person surveys, while the lowest rate occurs in Internet-based surveys. Telephone surveys are used to cover a wider population compared to other data collection methods. Many studies, especially those using in-person and mail-in data collection methods, incorporate supplemental data types and technological approaches. Outcome measures are frequently used to evaluate impacts caused by functional limitations related to physical, psychological, and social factors.

Frequently used self-reported oral health status and OHRQoL measures are OHIP-14, an impact measure, and the GOHAI, a functional measure. Children’s oral health outcomes measures form a considerable portion of the self-reported oral health outcome research papers. Although OHIP-14 is the most utilized single measure, many other papers use only portions of this measure, while adding other outcome measures, such as dental care needs, satisfaction, oral health status, and so on. The validity of these measures is therefore compromised and could not provide insight into the degree that the studies are measuring self-reported oral health status or quality of life [ 4 ]. Other measures rate an individual’s oral health status using a simple self-rating scale, from very poor to excellent. This approach is more directly related to a person’s oral conditions and therefore their perceptions and behavior tend to be more consistent with this rating [ 56 , 57 ]. These self-rating measures focus on the overall dimension of perceived oral health status. Unlike the measures previously discussed, these simple ratings do not delineate the psychological, social and physical dimensions of oral health. Nevertheless, such measures can enable researchers to identify hidden dimensions by analyzing independent variables that account for the respondent’s perception.

This review identifies research that employs more conventional methods. The face-to-face interview and the pencil and paper format are conventionally used in many studies along with a clinical dental exam. While offering unique flexibility and easier administration, in-person approaches are more labor-intensive and normally take more time compared to other methods. Countries, such as Brazil, rely for years on these techniques to develop national epidemiological oral health surveys [ 28 , 58 , 59 ]. Although these surveys are very well-organized and established throughout the country, this review does not find that newer technological approaches are introduced into their conventional approach. In this case, there may be little incentive to change their approach because their methods are well understood and employing more technological approaches may be costly.

The use of Internet-based surveys is increasingly common in the medical field. Although these surveys end with potentially lower response rates, this approach is normally more cost-effective [ 60 ]. Internet-based surveys have many notable advantages, including easy administration, fast data collection process, lower cost, wider population coverage and better data quality with fewer overall data errors and fewer missing items [ 61 , 62 , 63 ]. However, this data collection method is constrained by sample bias, topic salience, data security concerns and low digital literacy that may affect response rates [ 62 ]. In settings where Internet-based surveys are not practical, longstanding and effective conventional oral health data collection methods in research will continue. It is evident from this review that the use of computerized technological approaches is limited. While such approaches in survey research improve the quality and quantity of data collection, only twelve studies in this review employ them. The most widely used technical approaches are Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) and online survey platforms (e.g., Google Forms and SurveyMonkey).

Two noteworthy approaches to survey research methodology emerge from this review, particularly in: (1) sample selection, and (2) mode of interaction with research subjects. North American researchers found different platforms to access subjects for their studies. Canadian studies use random digit dialing to recruit and conduct computer-assisted interviews [ 54 ]. In the United States, researchers access existing polling populations or use Amazon’s MTurk platform for “workers” who are paid small amounts for each survey they respond to [ 64 ]. The second approach is the use of computers to collect self-reported data. The basic surveying technique is CAPI with interviewers directly entering the data into a database. There is also Computer-Assisted Telephone Interviewing (CATI), a survey technique, where the interviewer follows a scripted interview guided by a questionnaire that appears on the screen. A third Internet-based survey technique, the Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing (CAWI), requires no live interviewer. Instead, the respondent follows a script made in a program for designing web interviews that may include images, audio and video clips, and web-based information.

An innovative technological approach worth noting is the use of OralCam to perform self-examination using a smartphone camera [ 65 ]. The study applies research used in medicine to detect liver problems from face photos as well as other diseases [ 66 ]. The paper describes the use of a smartphone camera to interact with a computer using diagnostic algorithms, such as the deep convolutional neural network-based multitask learning approach. Based on over three thousand intraoral photos, the system learns to analyze teeth and gingiva. The smartphone camera takes a picture using a mouth opener. The computer’s algorithms analyze the captured picture, along with survey data, to diagnose several dental conditions including caries, chronic gingival inflammation, and dental calculus. This use of multitask learning technology, with the extensive availability of cell phones, may revolutionize oral health research and care.

This scoping review is limited to oral health survey-based studies in peer-reviewed journals and MedRxiv published in English between 2011 to 2021. A further limitation is that many of the reviewed papers do not adequately describe the methods they use to collect data. Publications using secondary data from national studies are excluded, The exclusion is based on the fact that these researchers are not engaged in designing the methods or conducting the data collection. Often, the publications refer to the original study to describe the method used. Also, the original data collection may have occurred before the time frame of this review. The fifteen papers that use secondary data published over this study’s time frame represent only about six percent of the reviewed papers. Thus, the overall impact of this exclusion is minimal on this scoping review’s results.

Conclusions

This scoping review provides an assessment of oral health outcome measures, including subject-reported oral health status, and notes newly emerging computer technological approaches recently used in surveys conducted on general populations. Such technological approaches, although rarely used in the reviewed studies, hold promise for both researchers and the various populations that use or need oral health care. Future studies employing more developed computer applications for survey research to boost recruitment and participation of study subjects with wide and diverse backgrounds from almost unlimited geographic areas can then provide a broader perspective on oral health survey methods and outcomes.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews

Asia-Pacific (including the Middle East)

Latin America

North America

Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing

Computer-Assisted Web Interviewing

Computer-Assisted Telephone Interview

Oral Health-Related Quality of Life

Oral Health Impact Profile-14

Geriatric Oral Health Assessment Index

Oral Health Status

Watt RG, Daly B, Allison P, Macpherson LMD, Venturelli R, Listl S, et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet. 2019;394:261–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31133-X .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Liu H, Hays R, Wang Y, Marcus M, Maida C, Shen J, et al. Short form development for oral health patient-reported outcome evaluation in children and adolescents. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1599–611. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11136-018-1820-9 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wang Y, Hays R, Marcus M, Maida C, Shen J, Xiong D, et al. Development of a parents’ short form survey of their children’s oral health. Int J Pediatr Dent. 2019;29:332–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/ipd.12453 .

Article Google Scholar

Yang C, Crystal YO, Ruff RR, Veitz-Keenan A, McGowan RC, Niederman R. Quality appraisal of child oral health-related quality of life measures: a scoping review. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2020;5:109–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084419855636 .

Gupta M, Bosma H, Angeli F, Kaur M, Chakrapani V, Rana M, et al. A mixed methods study on evaluating the performance of a multi-strategy national health program to reduce maternal and child health disparities in Haryana. India BMC Public Health. 2017;17:698. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4706-9 .

Keboa MT, Hiles N, Macdonald ME. The oral health of refugees and asylum seekers: a scoping review. Glob Health. 2016;12:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12992-016-0200-X/TABLES/2 .

Wilson NJ, Lin Z, Villarosa A, Lewis P, Philip P, Sumar B, et al. Countering the poor oral health of people with intellectual and developmental disability: a scoping literature review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-019-7863-1/TABLES/1 .

Ajwani S, Jayanti S, Burkolter N, Anderson C, Bhole S, Itaoui R, et al. Integrated oral health care for stroke patients—a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:891–901. https://doi.org/10.1111/JOCN.13520 .

Shrestha AD, Vedsted P, Kallestrup P, Neupane D. Prevalence and incidence of oral cancer in low- and middle-income countries: a scoping review. Eur J Cancer Care. 2020;29:66. https://doi.org/10.1111/ECC.13207 .

Patterson-Norrie T, Ramjan L, Sousa MS, Sank L, George A. Eating disorders and oral health: a scoping review on the role of dietitians. J Eat Disord. 2020;8:1–21. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40337-020-00325-0/TABLES/1 .

Lansdown K, Smithers-Sheedy H, Mathieu Coulton K, Irving M. Oral health outcomes for people with cerebral palsy: a scoping review protocol. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep 2019;17:2551–8. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-004037 .

Beaton L, Humphris G, Rodriguez A, Freeman R. Community-based oral health interventions for people experiencing homelessness: a scoping review. Community Dent Health. 2020;37:150–60. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_00014BEATON11 .

Marquillier T, Lombrail P, Azogui-Lévy S. Social inequalities in oral health and early childhood caries: How can they be effectively prevented? A scoping review of disease predictors. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2020;68:201–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESPE.2020.06.004 .

Como DH, Duker LIS, Polido JC, Cermak SA. The persistence of oral health disparities for African American children: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:66. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH16050710 .

Stein K, Farmer J, Singhal S, Marra F, Sutherland S, Quiñonez C. The use and misuse of antibiotics in dentistry: a scoping review. J Am Dent Assoc. 2018;149:869-884.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ADAJ.2018.05.034 .

Mittal H, John MT, Sekulić S, Theis-Mahon N, Rener-Sitar K. Patient-reported outcome measures for adult dental patients: a systematic review. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2019;19:53–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JEBDP.2018.10.005 .

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method Theory Pract. 2005;8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 .

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 .

Paré G, Trudel M-C, Jaana M, Kitsiou S. Synthesizing information systems knowledge: a typology of literature reviews. Inf Manag. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2014.08.008 .

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850 .

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310 .

Masood M, Masood Y, Newton T, Lahti S. Development of a conceptual model of oral health for malocclusion patients. Angle Orthod. 2015;85:1057–63. https://doi.org/10.2319/081514-575.1 .

Massarente DB, Domaneschi C, Marques HHS, Andrade SB, Goursand D, Antunes JLF. Oral health-related quality of life of paediatric patients with AIDS. BMC Oral Health. 2011;11:2. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6831-11-2 .

Lu TY, Chen JH, Du JK, Lin YC, Ho PS, Lee CH, et al. Dysphagia and masticatory performance as a mediator of the xerostomia to quality of life relation in the older population. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12877-020-01901-4 .

Strömberg E, Holmèn A, Hagman-Gustafsson ML, Gabre P, Wardh I. Oral health-related quality-of-life in homebound elderly dependent on moderate and substantial supportive care for daily living. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:771–7. https://doi.org/10.3109/00016357.2012.734398 .

Morgan JP, Isyagi M, Ntaganira J, Gatarayiha A, Pagni SE, Roomian TC, et al. Building oral health research infrastructure: the first national oral health survey of Rwanda. Glob Health Act. 2018;11:66. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2018.1477249 .

Preciado A, del Río J, Suárez-García MJ, Montero J, Lynch CD, Castillo-Oyagüe R. Differences in impact of patient and prosthetic characteristics on oral health-related quality of life among implant-retained overdenture wearers. J Dent. 2012;40:857–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JDENT.2012.07.006 .

de Quadros Coelho M, Cordeiro JM, Vargas AMD, de Barros Lima Martins AME, de Almeida Santa Rosa TT, Senna MIB, et al. Functional and psychosocial impact of oral disorders and quality of life of people living with HIV/AIDS. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:503–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11136-014-0778-5 .

Said M, Otomaru T, Aimaijiang Y, Li N, Taniguchi H. Association between masticatory function and oral health-related quality of life in partial maxillectomy patients. Int J Prosthodont. 2016;29:561–4. https://doi.org/10.11607/IJP.4852 .

Owens J, Jones K, Marshman Z. The oral health of people with learning disabilities—a user–friendly questionnaire survey. Community Dent Health. 2017;34:4–7. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_3867OWENS04 .

Abuzar MA, Kahwagi E, Yamakawa T. Investigating oral health-related quality of life and self-perceived satisfaction with partial dentures. J Investig Clin Dent. 2012;3:109–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.2041-1626.2012.00111.X .

Wilson D, Taylor A, Chittleborough C. The second Computer Assisted Telephone Interview (CATI) Forum: the state of play of CATI survey methods in Australia. Aust NZ J Public Health. 2001;25:272–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1467-842X.2001.TB00576.X .

Lee H, Friedman ME, Cukor P, Ahern D. Interactive voice response system (IVRS) in health care services. Nurs Outlook. 2003;51:277–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0029-6554(03)00161-1 .

Campos JADB, Zucoloto ML, Bonafé FSS, Maroco J. General Oral Health Assessment Index: a new evaluation proposal. Gerodontology. 2017;34:334–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/GER.12270 .

Slade GD. Derivation and validation of a short-form oral health impact profile. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1997;25:284–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1600-0528.1997.TB00941.X .

Adulyanon S, Vourapukjaru J, Sheiham A. Oral impacts affecting daily performance in a low dental disease Thai population. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1996;24:385–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1600-0528.1996.TB00884.X .

Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Slade GD. Parental perceptions of children’s oral health: the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-5-6 .

Gherunpong S, Tsakos G, Sheiham A. Developing and evaluating an oral health-related quality of life index for children: the CHILD-OIDP. Undefined. 2004;21:161–9.

Google Scholar

Slade GD, Spencer AJ. Development and evaluation of the Oral Health Impact Profile. Community Dent Health. 1994;11:3–11.

PubMed Google Scholar

Broder HL, Wilson-Genderson M. Reliability and convergent and discriminant validity of the Child Oral Health Impact Profile (COHIP Child’s version). Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007;35(Suppl 1):20–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1600-0528.2007.0002.X .

Atieh MA. Arabic version of the geriatric oral health assessment Index. Gerodontology. 2008;25:34–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-2358.2007.00195.x .

Wright WG, Spiro A, Jones JA, Rich SE, Garcia RI. Development of the teen oral health-related quality of life instrument. J Public Health Dent. 2017;77:115–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/JPHD.12181 .

Jokovic A, Locker D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Questionnaire for measuring oral health-related quality of life in eight- to ten-year-old children. Undefined. 2004;26:512–8.

Jokovic A, Locker D, Stephens M, Kenny D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Validity and reliability of a questionnaire for measuring child oral-health-related quality of life. J Dent Res. 2002;81:459–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/154405910208100705 .

Broughton JR, TeH Maipi J, Person M, Randall A, Thomson WM. Self-reported oral health and dental service-use of rangatahi within the rohe of Tainui. NZ Dent J. 2012;108:90–4.

Monaghan N, Karki A, Playle R, Johnson I, Morgan M. Measuring oral health impact among care home residents in Wales. Community Dent Health. 2017;34:14–8. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_3950MORGAN05 .

Echeverria MS, Silva AER, Agostini BA, Schuch HS, Demarco FF. Regular use of dental services among university students in southern Brazil. Revista de Saude Publica 2020;54:85. https://doi.org/10.11606/S1518-8787.2020054001935 .

Mohamad Fuad MA, Yacob H, Mohamed N, Wong NI. Association of sociodemographic factors and self-perception of health status on oral health-related quality of life among the older persons in Malaysia. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2020;20(Suppl 2):57–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/GGI.13969 .

Hanisch M, Wiemann S, Bohner L, Kleinheinz J, Susanne SJ. Association between oral health-related quality of life in people with rare diseases and their satisfaction with dental care in the health system of the Federal Republic of Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3390/IJERPH15081732 .

Nam SH, Kiml HY, IlChun D. Influential factors on the quality of life and dental health of university students in a specific area. Biomed Res. 2017;28:12.

Mortimer-Jones S, Stomski N, Cope V, Maurice L, Théroux J. Association between temporomandibular symptoms, anxiety and quality of life among nursing students. Collegian. 2019;26:373–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.COLEGN.2018.10.003 .

Liu C, Zhang S, Zhang C, Tai B, Jiang H, Du M. The impact of coronavirus lockdown on oral healthcare and its associated issues of pre-schoolers in China: an online cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21:66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01410-9 .

Makizodila BAM, van de Wijdeven JHE, de Soet JJ, van Selms MKA, Volgenant CMC. Oral hygiene in patients with motor neuron disease requires attention: a cross-sectional survey study. Spec Care Dent. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/SCD.12636 .

Kotzer RD, Lawrence HP, Clovis JB, Matthews DC. Oral health-related quality of life in an aging Canadian population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-10-50 .

Hakeberg M, Wide U. General and oral health problems among adults with focus on dentally anxious individuals. Int Dent J. 2018;68:405–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/IDJ.12400 .

Lawal FB, Olawole WO, Sigbeku OF. Self rating of oral health status by student dental surgeon assistants in Ibadan, Nigerian—a Pilot Survey. Ann Ibadan Postgrad Med. 2013;11:12.

Locker D, Wexler E, Jokovic A. What do older adults’ global self-ratings of oral health measure? J Public Health Dent. 2005;65:146–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1752-7325.2005.TB02804.X .

Saintrain MVDL, de Souza EHA. Impact of tooth loss on the quality of life. Gerodontology. 2012;29:66. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1741-2358.2011.00535.X .

Grando LJ, Mello ALSF, Salvato L, Brancher AP, del Moral JAG, Steffenello-Durigon G. Impact of leukemia and lymphoma chemotherapy on oral cavity and quality of life. Spec Care Dent. 2015;35:236–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/SCD.12113 .

Ebert JF, Huibers L, Christensen B, Christensen MB. Paper- or Web-Based Questionnaire Invitations as a method for data collection: cross-sectional comparative study of differences in response rate, completeness of data, and financial cost. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:66. https://doi.org/10.2196/JMIR.8353 .

Hohwü L, Lyshol H, Gissler M, Jonsson SH, Petzold M, Obel C. Web-based versus traditional paper questionnaires: a mixed-mode survey with a Nordic perspective. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15:66. https://doi.org/10.2196/JMIR.2595 .

Maymone MBC, Venkatesh S, Secemsky E, Reddy K, Vashi NA. Research techniques made simple: Web-Based Survey Research in Dermatology: conduct and applications. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:1456–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JID.2018.02.032 .

Weigold A, Weigold IK, Natera SN. Response rates for surveys completed with paper-and-pencil and computers: using meta-analysis to assess equivalence. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2018;37:649–68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439318783435 .

Burnham MJ, Le YK, Piedmont RL. Who is Mturk? Personal characteristics and sample consistency of these online workers. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2018;21:934–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2018.1486394 .

Liang Y, Fan HW, Fang Z, Miao L, Li W, Zhang X, et al. OralCam: enabling self-examination and awareness of oral health using a smartphone camera. In: Conference on human factors in computing systems—proceedings, vol 20. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2020. p. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376238 .

Ding X, Jiang Y, Qin X, Chen Y, Zhang W, Qi L. Reading face, reading health: Exploring face reading technologies for everyday health. In: Conference on human factors in computing systems—proceedings. New York: Association for Computing Machinery; 2019. p. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300435 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This research was supported by an NIDCR/NIH grant to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) (U01DE029491). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Division of Oral and Systemic Health Sciences, School of Dentistry, University of California, Los Angeles, 10833 Le Conte Ave, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Carl A. Maida, Di Xiong, Marvin Marcus, Linyu Zhou, Yilan Huang, Yuetong Lyu, Jie Shen & Honghu Liu

Department of Biostatistics, Fielding School of Public Health, University of California, Los Angeles, 650 Charles E Young Drive South, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Di Xiong, Linyu Zhou, Yilan Huang, Yuetong Lyu & Honghu Liu

Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, University of California, Los Angeles, 12-077 Center for Health Sciences, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Antonia Osuna-Garcia

Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, Geffen School of Medicine, University of California, Los Angeles, 10833 Le Conte Ave, Los Angeles, CA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

C.M., D.X., M.M. and H.L. conceptualized the study and designed the data collection form and established the data analysis plan. A.O. developed search strategies and carried out searching on multiple databases. D.X., Y.L., Y.H., J.S. and Y.L. performed additional searching and tested the data charting form. D.X., Y.L., and Y.H. helped to screen studies for relevance and data charting. C.M. and M.M. reviewed full-text papers and verify the data charting results. C.M., D.X., and M.M. drafted the original manuscript. D.X. and L.Z. prepared Tables 1 , 2 and Fig. 1 . C.M., D.X., M.M., and L.Z prepared Tables 3 and 4 . All authors read and provided substantial comments/edits on the manuscript and approved the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Honghu Liu .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search Terms.

Additional file 3.

Search Tool.

Additional file 4.

Data Charting Form.

Additional file 5.

Glossary of Terms.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Maida, C.A., Xiong, D., Marcus, M. et al. Quantitative data collection approaches in subject-reported oral health research: a scoping review. BMC Oral Health 22 , 435 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02399-5

Download citation

Received : 31 December 2021

Accepted : 17 August 2022

Published : 03 October 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-022-02399-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Quantitative research

- Patient-reported outcomes

- Dental disease experience

- Oral health-related quality of life

- Data collection

BMC Oral Health

ISSN: 1472-6831

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Nih…turning discovery into health ®.

Research for Healthy Living

Oral Health

In the early part of the 20th century, it was common for women and men to lose many teeth as they aged, leaving them to rely on dentures. That story began to change dramatically in the 1940s and 1950s, when NIH scientists showed that the rate of tooth decay fell more than 60 percent in children who drank fluoridated water. This discovery laid the foundation for a major component of modern dental health.

Today, research on oral health extends far beyond teeth. NIH researchers consider the mouth an expansive living laboratory to understand infections, cancer, and even healthy development processes. For example, we know that oral tissues and fluids, which are home to about 600 unique microbial species, can have remarkable protective roles against infection and possibly other conditions.

NIH research on oral health is working to understand and manipulate the body’s innate ability to repair and regenerate damaged or diseased tissues. These approaches will guide prevention and treatment of health problems not only in teeth and in the mouth, but also in other organs and tissues.

Optimal health for women and men

Certain health conditions are more common in women than in men, such as osteoporosis, depression, and autoimmune diseases. Others are more common in males, such as autism and color blindness. And there are those conditions that affect women and men differently, such as heart disease. While chest pain is common to both women and men suffering a heart attack, women may experience other symptoms such as nausea, back or neck pain, and fatigue, which they may not link to problems of the heart. NIH researchers are studying these differences, toward providing personalized care for individuals. The sexes can also have very different responses to even very common drugs like aspirin. So, NIH research ensures that females, including pregnant women when it is safe to do so, are included in sufficient numbers in clinical trials that test new medicines. Currently, slightly more than half of clinical trial participants are women.

« Previous: Arthritis Next: Vision »

This page last reviewed on November 16, 2023

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

Oral hygiene can reduce risk of some cancers

April 18, 2024—A healthy mouth microbiome can help prevent a number of diseases, including cancer , according to Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Mingyang Song .

Song, associate professor of clinical epidemiology and nutrition, was among the experts quoted in an April 4 Everyday Health article about the connections between mouth, gum, and tooth health and overall health. “Alterations in the oral microbiome can cause systemic inflammation and increase disease risk indirectly,” Song explained. Microbes in the mouth can also travel to other parts of the body and directly increase the risk of conditions like diabetes , heart disease , Alzheimer’s disease , and various cancers, he added.

Previous studies co-authored by Song have shed light on the oral microbiome’s impacts on the risk of stomach and colorectal cancers. One study found that people with a history of gum disease have a 52% greater chance of developing stomach cancer compared with those without gum disease, and that losing two or more teeth raised stomach cancer risk by 33%. Another study found that people with gum disease had a 17% greater chance than those without gum disease of developing a serrated polyp—a type of polyp that can lead to colon cancer. The study also found that people who had lost at least four teeth had a 20% higher risk of a serrated polyp.

The takeaway, Song said, is to keep the mouth microbiome healthy. This can be accomplished through practicing oral hygiene—visiting the dentist regularly and brushing, flossing, and using mouthwash daily—as well as maintaining an overall healthy lifestyle through diet , exercise , and avoiding smoking .

Read the article in Everyday Health: The Health of Your Mouth May Affect Your Risk of Colorectal Cancer

– Maya Brownstein

Image: iStock/fizkes

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Global HIV/AIDS Response: Then, Now, Future

Dental experts discuss sealant implementation

Mechanism may recur in other diseases

An oral cancer exam is quick and painless

Diversity at NIDCR

NIDCR is dedicated to building an inclusive and diverse community in its research training and employment programs.

Learn about Diversity at NIDCR

Our Research

NIDCR is the federal government's lead agency for scientific research on dental, oral and craniofacial health and disease.

Leadership & Staff

Research funded by nidcr (extramural), research conducted at nidcr (intramural).

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 04 September 2023

An online survey of oral health behaviours and impact on young children and families in Wales

- Anup J. Karki 1 ,

- Ulugbek Nurmatov 2 ,

- Mark D. Atkinson 3 ,

- Aideen Naughton 1 &

- Alison Kemp 2

British Dental Journal ( 2023 ) Cite this article

121 Accesses

Metrics details

Introduction Studies outside Wales have consistently reported reduced quality of life as measured by the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale. With relatively high levels of tooth decay in Wales as found through the regular dental surveys, it is important to understand different oral health-related behaviours and impact so that findings can inform oral health promotion in Wales.

Methods An oral health questionnaire was made available to volunteers registered with Health Wise Wales. Parents of children (2-6 years old) participated in the study. Frequency analyses were carried out to understand the oral health-related behaviours and regression analysis was carried out to understand the predictors of reported oral health impacts.

Results Overall reported oral health impact was low in this study. In total, 20% of parents reported that their child brushed their teeth less than twice a day and 23% reported toothbrushing without adult supervision. Drinking plain water twice a day or more was associated with good oral health in children.

Conclusion Overall, reported oral health impact was low, which is likely to be due to under-representation of study participants from the deprived areas in Wales. There is plenty of room for improvement in oral health-related behaviours.

Health Wise Wales (HWW), an online register of people in Wales who have volunteered to participate in research, provided access to a 'research ready' population for this study. The disadvantage of the HWW was that the register was not fully representative of the Welsh general population.

This paper provides an overview of oral health behaviours and reported impact on young children in Wales. Overall reported impact was low and 20% parents reported that their children brush their teeth less than twice a day.

Drinking plain water twice a day or more compared to drinking no water was a significant predictor of low oral health impact. Increased use of plain water by children to meet their hydration need may also indirectly help oral health.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 24 print issues and online access

251,40 € per year

only 10,48 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of the physical and mental health benefits of touch interventions

Julian Packheiser, Helena Hartmann, … Frédéric Michon

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Joseph M. Rootman, Pamela Kryskow, … Zach Walsh

Microbiota in health and diseases

Kaijian Hou, Zhuo-Xun Wu, … Zhe-Sheng Chen

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392: 1789-1858.

Peres M A, Macpherson L M, Weyant R J et al . Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet 2019; 394: 249-260.

Glick M, Williams D M, Kleinman D V, Vujicic M, Watt R G, Weyant R J . A new definition for oral health developed by the FDI World Dental Federation opens the door to a universal definition of oral health. J Am Dent Assoc 2016; 147: 915-917.

Cardiff University. Picture of Oral Health 2017, Dental Caries in 5 Year Olds (2015/16). 2017. Available at https://www.cardiff.ac.uk/research/explore/research-units/welsh-oral-health-information-unit (accessed August 2023).

Gilchrist F, Marshman Z, Deery C, Rodd H D. The impact of dental caries on children and young people: what they have to say? Int J Paediatr Dent 2015; 25: 327-338.

Abanto J, Carvalho T S, Mendes F M, Wanderley M T, Bönecker M, Raggio D P. Impact of oral diseases and disorders on oral health-related quality of life of preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2011; 39: 105-114.

Welsh Government. Child General Anaesthetics in Wales. 2019. Available at https://www.gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-10/child-dental-general-anaesthetics-in-wales-2018-2019.pdf (accessed August 2023).

Pahel B T, Rozier R G, Slade G D. Parental perceptions of children's oral health: the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2007; 5: 6.

Scarpelli A C, Oliveira B H, Tesch F C, Leão A T, Pordeus I A, Paiva S M. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Early Childhood Oral Health impact Scale (B-ECOHIS). BMC Oral Health 2011; 11: 19.

Li S, Veronneau J, Allison P J. Validation of a French language version of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008; 6: 9.

Lee G H, McGrath C, Yiu C K, King N M. Translation and validation of a Chinese language version of the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS). Int J Paediatr Dent 2009; 19: 399-405.

Chaffee B W, Rodrigues P H, Kramer P F, Vítolo M R, Feldens C A. Oral health-related quality-of-life scores differ by socioeconomic status and caries experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2017; 45: 216-224.

Kramer P F, Feldens C A, Ferreira S H, Bervian J, Rodrigues P H, Peres M A. Exploring the impact of oral diseases and disorders on quality of life of preschool children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2013; 41: 327-335.

Wong H M, McGrath C P, King N M, Lo E C. Oral health-related quality of life in Hong Kong preschool children. Caries Res 2011; 45: 370-376.

Ramos-Jorge J, Alencar B M, Pordeus I A et al. Impact of dental caries on quality of life among preschool children: emphasis on the type of tooth and stages of progression. Eur J Oral Sci 2015; 123: 88-95.

Chaffee B W, Rodrigues P H, Kramer P F, Vítolo M R, Feldens C A. Oral health-related quality of life measures: variation by socioeconomic status and caries experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2017; 45: 216-224.

Hurt L, Ashfield-Watt P, Townson J et al . Cohort profile: HealthWise Wales. A research register and population health data platform with linkage to National Health Service data sets in Wales. BMJ Open 2019; DOI: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031705.

Li Y, Wang W. Predicting caries in permanent teeth from caries in primary teeth: an eight-year cohort study. J Dent Res 2002; 81: 561-566.

British Society of Paediatric Dentistry. A Practical guide to children's teeth. Available at https://www.bspd.co.uk/Portals/0/A%20Practical%20Guide%20to%20Childrens%20Teeth.pdf (accessed August 2021).

Chestnutt I G, Schäfer F, Jacobson A P, Stephen K W. The influence of tooth brushing frequency and post-brushing rinsing on caries experience in a caries clinical trial. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1998; 26: 406-411.

Trubey R J, Moore S C, Chestnutt I G. Parents' reasons for brushing or not brushing their child's teeth: a qualitative study. Int J Paediatr Dent 2014; 24: 104-112.

Vieux F, Maillot M, Constant F, Drewnowski A. Water and beverage consumption patterns among 4 to 13-year-old children in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health 2017; 17: 479.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Public Health Wales, Capital Quarter 2, Cardiff, CF10 4BZ, Wales, United Kingdom

Anup J. Karki & Aideen Naughton

Division of Population Medicine, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Wales, United Kingdom

Ulugbek Nurmatov & Alison Kemp

Swansea University Medical School, Swansea, Wales, United Kingdom

Mark D. Atkinson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Anup J. Karki, Ulugbek Nurmatov, Mark D. Atkinson, Aideen Naughton and Alison Kemp contributed to the study design and writing of this paper for publication. Mark Atkinson carried out the statistical analyses.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Anup J. Karki .

Ethics declarations

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

HWW received ethical approval from the Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) 3 on 16 March 2015 (reference 15/WA/0076). Applications to use the HWW for oral health data collection was reviewed by a Scientific Steering Group and Patient and Public Involvement representatives to assess if the proposed project fits with the ethos of the HWW and is scientifically sound. Participants for this study consented to complete the oral health questionnaire. Separate ethical approval was not required.

The datasets for this study are not publicly available due to privacy and/or ethical restrictions in accessing data collected by Healthwise Wales. Oral health questionnaire data that support the findings of this study can be obtained through the corresponding author on a reasonable request.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information (pdf 125kb), rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Karki, A., Nurmatov, U., Atkinson, M. et al. An online survey of oral health behaviours and impact on young children and families in Wales. Br Dent J (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6230-x

Download citation

Received : 14 November 2022

Revised : 14 April 2023

Accepted : 04 May 2023

Published : 04 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-023-6230-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the United States government