An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Healthcare (Basel)

Current Issues on Research Conducted to Improve Women’s Health

Charalampos siristatidis.

1 Assisted Reproduction Unit, Second Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Aretaieion Hospital, 76 Vass Sofias, 11528 Athens, Greece

Vasilios Karageorgiou

2 2nd Department of Psychiatry, Medical School, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Attikon Hospital, 1 Rimini Street, 12642 Athens, Greece; moc.liamtoh@groegaraksav

Paraskevi Vogiatzi

3 Andromed Health & Reproduction Diagnostic Lab, 3 Mesogion Str, 15126 Maroussi, Greece; moc.liamg@iztaigovive

Associated Data

Not applicable.

There are varied lessons to be learned regarding the current methodological approaches to women’s health research. In the present scheme of growing medical literature and inflation of novel results claiming significance, the sheer amount of information can render evidence-based practice confusing. The factors that classically determined the impact of discoveries appear to be losing ground: citation count and publication rates, hierarchy in author lists according to contribution, and a journal’s impact factor. Through a comprehensive literature search on the currently available data from theses, opinion, and original articles and reviews on this topic, we seek to present to clinicians a narrative synthesis of three crucial axes underlying the totality of the research production chain: (a) critical advances in research methodology, (b) the interplay of academy and industry in a trial conduct, and (c) review- and publication-associated developments. We also provide specific recommendations on the study design and conduct, reviewing the processes and dissemination of data and the conclusions and implementation of findings. Overall, clinicians and the public should be aware of the discourse behind the marketing of alleged breakthrough research. Still, multiple initiatives, such as patient review and strict, supervised literature synthesis, have become more widely accepted. The “bottom-up” approach of a wide dissemination of information to clinicians, together with practical incentives for stakeholders with competing interests to collaborate, promise to improve women’s healthcare.

1. Introduction

Women’s health has been at the center of interest and growing concern in the last few decades. As a measurable outcome, it has been studied at the level of mortality [ 1 ], serious morbidity [ 2 ], and nutritional status [ 3 ] and through proven, evidence-based interventions. The implementation of such interventions is essential to guide national and international policies and programs, targeting the achievement of universal coverage of health services. In this respect, conducting the best quality of research (research that provides firm and ethical evidence adhering to the principles of professionalism, transparency, and auditability) with the use of robust methods is mandatory. Towards this goal, the current reality is far from encouraging.

In accordance with scientific literature guidelines and research quality guidelines (e.g., the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)), impact factors, and citation count are considered the norms in current research evaluation modalities. However, recent works in research methodology challenge this simplifying notion [ 4 , 5 , 6 ].

The pitfalls reported are associated with various—albeit specific—“cultural, ethical, operational, regulatory, and infrastructural factors” linked with a lack of adequately trained researchers and subject attrition bias [ 7 ]. As a result, the clinical research environment is more or less inseminated with various types of bias, leading to the discouragement of sponsors. The growing plethora of questionable quality trials and reviews is another issue to consider. “From 14 reports of trials published per day in 1980 [to] 75 trials and 11 systematic reviews of trials per day, a plateau in growth has not yet been reached”, stated a policy forum article reported in 2010 [ 8 ]; additionally, the authors noted that “the staple of medical literature synthesis remains the non-systematic narrative review”, further pointing out the need for freely available simple yet valid answers to most patients’ questions [ 8 ]. In the same context, current data concerning women’s health derived from protocols, full study reports, and participant-level datasets are rarely available to a wide audience. At the same time, selective reporting of methods and results plagues reports. With the reduced quality of information produced, a lot of money has been wasted; subsequently, the existence of all kinds of bias affect the research itself and jeopardize the validity of the findings and, consequently, the care of women [ 9 ].

Issues have been raised by exploring different approaches to evaluate the quality of scientific input to the community. The ultimate goal remains a robust and uniform literature evaluation system adapted to the evolving conduct of studies and to the application of modern tools to re-ensure robust methodology and reporting of data and results. Here, we perform a narrative overview on current issues in study quality assessment regarding clinical medicine. We electronically searched PubMed using the following keywords: “clinical trials”, “meta-analysis”, “IPD”, “sponsor”, “challenges”, “regulatory”, “women’s health”, “evidence-based medicine/trends”, “policy making”, “publishing”, “research methods and practices”, “consumers network”, “bias”, “industry-sponsored trials”, “biomedical bibliographic databases”, and “quality research”, trying to collect data irrespective of type of report and language. Based on this evidence, we propose a combination of interventions at various levels, underlining quality aspects that we consider significant, and other routes of judgments.

2. The “Standard” Factors

Citation count and publication rates in international databases, hierarchy in author lists according to contribution, and the impact factor of the journal are considered important factors in the quality of a study, especially for the “scientific reader” seeking quality information on a specific topic. This has been extensively studied by other workgroups [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] and represents a justified trend accounting for the prestige of a scientific journal and the publication itself, along with language and availability, and ultimately skewing scientific trends or potentially leaving some important contributions in obscurity. Even though previous works contemplate the importance of the aforementioned factors in the true quality of research studies and publications, all considerations are derived from a common denominator, that is, that the currently used quality standards either for the common user or for greater structures and institutions most probably do not reflect quality but rather popularity. In this context, the citation rate (including self-citation and “negative citing”) and an impact statement on the individual author (a concise summary of the impact of somebody’s career) have been proposed. In addition, other metrics, including altmetrics, bibliometrics, and H-index, combined with updated mathematical models, such as artificial neural networks, might be the tools of the future; these models constitute more accurate tools due to the special characteristics of these “learning through training” processes, resembling the capacity of the brain to learn and judge [ 14 ].

3. The Type of Research Question and Studies

Although multiple outcomes may be reported at once and variability in study designs fluctuates, a primary role belongs to the type of research question explored by a study or publication, which will inevitably determine the methodology to be followed. For example, in past years, there is a disproportionate output of Systematic Reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses from Asian countries produced on a massive scale [ 15 , 16 ] as a means of “publishing in order to publish” with questionable quality and methods. Their numbers are so high that, in some cases, it overtakes original trials. Of note, the use of such studies in the biomedical field was occasional until the 1990s [ 17 ]. Moreover, those from the Cochrane collaboration, the fundamental organization for good quality systematic reviews, are only a small fraction of this output [ 8 ].

With regard to Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs), suggestions have been made in recent reports on better conduct [ 18 ]: trial protocols should be simple, reproducible, and well organized, with predefined and well-described study populations/participants and should have sound interventions, and representative comparisons and outcomes. Of note, these could be based on the conclusions of previously conducted SRs that often point out issues in quality and methodology of the original trials. Minimal deviations from protocols and a priori specification of useful core outcomes that translate directly to women’s wellbeing are the focus of the CROWN Initiative [ 19 ]. According to the authors, there has been a multi-targeted set of suggestions to “ensure that critical and important outcomes with good measurement properties are incorporated and reported, in advancing the usefulness of research, in informing readers, including guideline and policy developers, who are involved in decision-making, and in improving evidence-based practice”.

A priori description of the outcomes of interest can alleviate the known issues/biases associated with exploratory analyses. A change in outcome, especially in cases where the results do not support the rationale of the study, can mask the original intentions of the authors and can recontextualize the same results in a more positive manner [ 20 ]. Still, an exploratory analysis has a significant role in deducing potentially valuable conjectures for future studies. However, it is central for transparency that the authors explicitly state when this is the case, i.e., when an analysis is conducted post hoc. In order to ease the distinction of post hoc and a priori analyses by SR authors and readers, Dwan et al. (2014) proposed the publication of both protocols and pre-specified analyses [ 21 ].

We cannot anticipate that SRs can retrospectively solve the potential gaps and inconsistencies in the methodology and outcome reporting. For robust answers, research questions must be well defined from the start. However, more elaborate techniques of evidence synthesis can guide future research in more meaningful ways and are becoming more popular. Specifically, prospective and individual patient data meta-analyses (IPDMA) may need to become the norm in literature synthesis [ 22 , 23 ]. A major difficulty in IPDMA is the fact that securing sensitive patient data is a time-consuming task that demands the establishment of mutual trust. Even when representative evidence has been secured, data availability may still affect the pooled evidence. A recent study assessing IPDMA’s treating oncological topics suggested that studies for which they were available differed significantly from studies in which the authors did not share them [ 24 ]. Still, IPDMA is a trustworthy methodology that can assess the effect of patient-level covariates on treatment outcomes or diagnostic accuracy more thoroughly than the standard procedure of a meta-regression used in aggregate-data meta-analyses [ 25 ]. Given the current ethos of openness in clinical trials and common repositories becoming more widespread, IPDMA is likely to become the mainstay of critical synthesis of literature [ 26 ].

Finally, we have to include observational research in an effort to improve women’s health in the context of greater personalization of care and stratified medicine. Such studies have traditionally served as tools for understanding the nature of particular clinical conditions, for determining risk factors and mechanisms of actions, and for identifying potential intervention targets. Their disadvantages associated with methodological issues such as confounds and the fact that they are prone to limited internal validity could be restricted through guidelines such as the strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement [ 27 ].

4. The Inclusion of Young Authors

The encouragement of younger and/or less experienced scientists and ultimately their inclusion in the respective workgroups and in the list of contributors may provide an unexpected topic or question and a clearer view on established research schemes. The productivity of highly cited papers is related to the advanced age of their authors; adversely, better funding opportunities for younger researchers would give them unique chances to build strong productivity [ 28 ]. The advancement of knowledge taught during academic training as well as a higher probability of compliance with robust methods of reporting should encourage the inclusion of younger scientists. Tips and recommendations of young authors and early career scientists have been plenty, including collaborating with researchers within as well as outside their field and/or country, sending their research article to an appropriate journal, and adequately highlighting the novelty and impact of their research [ 29 , 30 ].

Towards this goal, the improvement of the scientific literacy of young scholars is the main step, and this burden falls on to the shoulders of the trainers. There are “uncomfortable truths” in training [ 31 ], but scientific research and the mode of thinking are processes continuously accumulated and must be taught by each director or responsible authority: they should improve the skills and capabilities of young scholars in scientific and technological literacy and in communication and productivity.

5. Quality in Reporting

Reporting quality must be ensured by avoiding bias, such as selective reporting, deliberate or not. Avoiding reporting insignificant data and outcomes could lead to severe distortion in the SR [ 32 ]. Thus, flaws in design, conduct, analysis, or reporting of RCTs can produce bias in the estimates of a treatment effect.

For example, in a large meta-epidemiological study of 1973 RCTs, a lack of blinding was associated with an average 22% exaggeration of treatment effects among trials that reported subjectively assessed outcomes [ 33 ]. This deviation is enough to adversely affect the interpretation of the results and further negatively influences regulatory settings and clinical practice.

Another example involves the evidence base on recent cancer drug approvals. Between 2014 and 2016, a quarter of the relevant studies were not RCTs; of the RCTs, the majority of them did not measure overall survival or quality of life outcomes as primary endpoints, and half of them were judged to be at high risk of bias; the authors’ judgments changed for a fifth of them when they relied on information reported in regulatory documents and scientific publications separately [ 34 ].

6. Strict Implementation of Rules in the Peer Review Processes

These processes first appeared in 1655 in a collection of scientific essays by Denis de Sallo in the Journal des Scavans , and almost 100 years later (1731), their implementation became a standard of practice by almost all biomedical journals [ 35 ]. Maintaining the quality and scientific integrity of publications; evaluating for competence, significance, and originality; and ensuring internal and external validity of submissions are crucial points. Similarly, the appropriate selection and training of reviewers to provide quality and specialized reviews without bias is an essential part of the process [ 36 ].

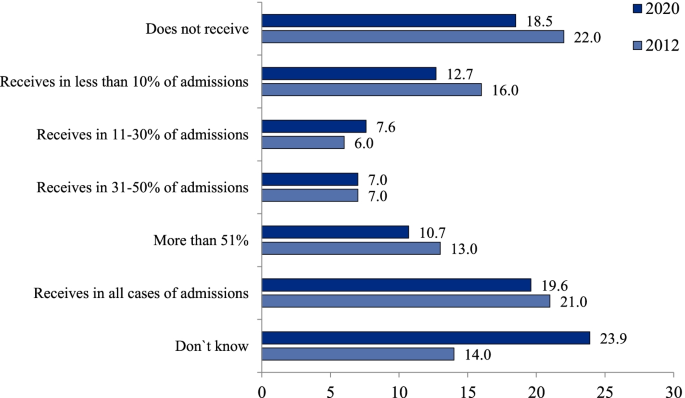

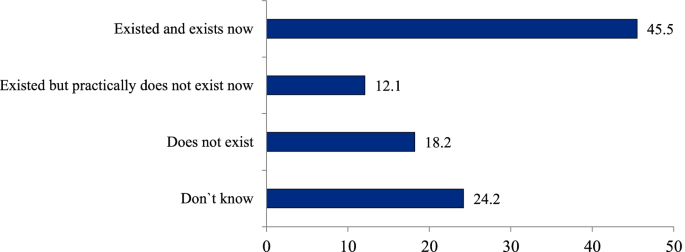

7. Sponsorship

Ethical and other issues surrounding sponsorships, to ensure credibility of a study, have been addressed in the past. One of the main sources of funding remains the industry [ 37 ]. Indeed, sponsored clinical research has always been questioned, influenced by reports of selective or biased disclosure of research results, ghostwriting and guest authorship, and inaccurate or incomplete reporting of potential conflicts of interest [ 38 ]. Although these may be a scarce incidence nowadays, active monitoring in funded studies should be implemented throughout in order to eliminate this possibility or any other conflicts of interest. An alarming analysis of 319 trials indicated that only a small minority (three out of 182 funded trials) were funded by multiple sponsors with competing interests. The presence of industry funding also almost tripled (OR = 2.8, 95% CI: 1.6, 4.7) the possibility of a study having reported favorable findings [ 39 ]. Furthermore, registered study protocols that announced funding were less likely to be published after their completion (non-publication rate: 32% vs. 18% [ 40 ].

8. Change in the Notion of Publishing

The change in notion and perception of the impact of outcomes is perhaps the most important part of the improvement in research conduct and implementation. This can be achieved through differentiation and modern adaptation of our scientific culture fighting inner and external incentives. Every scientific input should target a wider human benefit. A change in notion and incentives in publishing is crucial, from the level of the investigator aiming to publish/individual behaviors up to the social forces that provide affordances and incentives for those behaviors [ 41 , 42 , 43 ].

In a specific area of research, a clinical evaluation should precede publication in order to ensure relevance. A dramatic example is the scientific literature demonstrating an overload of various biomarkers for various diseases in which only a few of them have been confirmed by subsequent research and few have entered routine clinical practice [ 44 ]. In addition, biomarkers should also be judged on the grounds of cost-effectiveness and incremental net benefit [ 45 ]. Multiple indices may have comparable diagnostic accuracy, but their cost, an unavoidable concern in public health, may differ significantly.

Therefore, the selection of information to be published should be conducted on safer grounds and should be adequately supported by the authors, based on our knowledge on the scheme to date, and importantly, a summary of previous attempts should note the effective interventions and provide a concluding remark for the scientist through a good quality review.

9. Patient’s Contribution to Evaluation and Sex/Gender Analyses

In the era of evidence-based medicine, feedback from the recipients of healthcare development is gaining more importance and platforms for opinion exchange between patients and investigators have been established. This has already been implemented by the Cochrane Collaboration, where patient review is an integral part of the SR publication process and plain language summaries target a nontechnical audience. This process could be adopted as standard practice if accordingly modified. If the patient review, for example, is to be widely implemented in other journals, it would constitute a potentially radical paradigm shift that aims to solidify the review process. Of course, technical difficulties, such as acknowledgement and incentives for patients participating in review processes, are fields where further developments will enhance this policy [ 46 ].

It has been noted that the women population represents an “unequal majority” in health and health care. It is also well established that women’s health needs are dissimilar from those of men, resulting from the fact that both the woman’s body and brain functions differ critically from a man’s and that she reacts differently to even the same stimuli, such as medications or environmental events. It is indicative that, even though a large proportion of study protocols included women, only 3% of them planned an analytical approach for quantifying sex differences [ 47 ]; similarly, a recent report on therapies for atrial fibrillation concluded that the sex-specific reporting in trials comparing them was extremely low [ 48 ]. As a result, women have not received an ideal “personalized” health care, in many cases, so far. Thus, a specific design for studies on women’s health should be required.

There are several examples in the history of women’s health research where the contribution of the consumer women’s health movement in promoting research in women’s interests was critical. One of them concerned the collaborations between consumer groups and researchers in obtaining funding in the U.S. and France for a follow-up on a cohort of diethylstilboestrol-exposed people when the drug was discovered to be a transplacental carcinogen in pregnancy in 1971.

Another important issue is the nonavailability of sex/gender data from primary studies and consequently from SRs, which are the main tools to provide the necessary evidence for the formation of relevant policies [ 49 ]: the authors stated that even “Cochrane and the Campbell Collaboration have no specific policy on the reporting of sex/gender in systematic reviews, although Cochrane has endorsed the SAGER guidelines developed by the European Association of Science Editors” [ 50 ]. In their review, they found that the Methods sections of these collaborations included the most reports on sex/gender in both Campbell (50.8%) and Cochrane (83.1%) reviews, but the majority of these were descriptive considerations of sex/gender. They also reported that 62% of Campbell and 86% of Cochrane reviews did not report sex/gender in the abstract but included sex/gender considerations in a later section. A previous study on the subject reported that almost half of SRs described the sex/gender of the included populations but only 4% assessed sex/gender differences or included sex/gender when making judgments on the implications of the evidence [ 51 ].

10. An Improvement in the Dissemination of Studies

Despite advances in the dissemination of study information, half of health-related studies remain unpublished [ 52 ]. Problems in the publishing scheme in the selection of studies that appear to have a higher impact or that come from a respectable institution can lead to biased publishing. At the extreme, unsafe, ineffective, or even harmful interventions may enter clinical practice, as was the case with hormone replacement therapy [ 53 ]. In some instances, even a shift in healthcare resource allocation is reported [ 9 ]. It is standard practice in critical readings of literature to evaluate publication bias. This method attempts to address, with controversial success, precisely the unfortunate keenness of editors to promote positive results that imply novelty. A classic example of this inflation of positive and supposedly important results is the 2012 study by Fanelli [ 54 ], in which studies classified as related to clinical medicine showed a gradual increase in reporting positive findings. The author criticized the efficacy of measures taken to attenuate publication bias, e.g., protocol registration.

On the other hand, a respectable amount of research is published in other languages and not indexed in U.S. National Library of Medicine [ 55 ], while their quality remains controversial [ 56 ]; the authors of the above studies stated that peer review processes need to be improved through guidelines aiming to identify the authenticity of the studies.

The bulk of peer reviews remain a voluntary occupation, with the main motivation being recognition by peers. In addition, statistical review, a time-consuming process, is not performed in all published research. This process can be accelerated by practices that promote data and code sharing. It is also suggested that, even when papers are retracted, this could have been avoided with the simple measure of an active data sharing policy [ 57 ].

11. Role of the Stakeholders and Foundations

For the stakeholders and collaborative systems, a more energetic role is required in ensuring the conduct of multicenter massive-trials with increased clinical relevance. The main problem in the conduct of research is the lowered clinical value of the results from small sample sizes, even in RCTs. Mathematical models have been developed to predict sample sizes corresponding to the clinical value of the outcomes, while patient data from databases could easily increase the sample size of trials at much lower costs. Such paradigms could include the Health Care Systems Research Collaboratory and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Network (PCORnet) [ 58 ]. Also, new levels of patient engagement can raise the possibility of improving clinical outcomes on health. Involving multiple stakeholders (with potentially conflicting interests) in shared conversations on research has been proposed [ 59 ].

New foundations should be placed in research by focusing on the improvement of quality, such as NIH and PCORI [ 60 ]. The Cochrane Collaboration represents one of the very few large-scale initiatives in this context; importantly, both conduct high quality reviews, and participant education at all levels are based mostly from volunteers who care about science and high-quality evidence.

12. Cooperation of All Forces: The Role of Industry/Funding

The central point of problem is funding. USA-affiliated industry-funded trials and related activities represent more than 5% of US healthcare expenditure, with approximately $70 billion in commercial and $40 billion in governmental and non-profit funding annually. The NIH invests $41.7 billion annually in medical research: 80 percent is awarded for extramural research, through 50,000 competitive grants to more than 300,000 researchers at more than 2500 universities, medical schools, and other research institutions [ 61 ]. Concerns have been raised that this approach appears inefficient for how biomedical research is chosen, designed, regulated, financed, managed, disseminated, and reported [ 62 , 63 , 64 ].

The scheme, however, has been shifting in favor of Asian countries. Factors, such as ease of recruitment, population, and various epidemiological factors (e.g., increased incidence of infectious disease) have contributed positively to an inflation of local clinical trials [ 7 ]. Severe accusations regarding clinical data management have been raised, although the magnitude of the problem cannot be safely evaluated [ 65 ]. This unavoidably hinders the validity and future usefulness of these results despite initial enthusiasm from editors and the industry.

Economic forces are important, and ultimately, the industry seeks to maximize profit by providing new products and services to the medical market [ 66 ]. In industry-funded clinical research, intentional and unintentional commercial motives can control the study design and comparators. Governmental involvement [ 66 ] has an important role in distributing research funds in areas important for the protection and restoration of human health, even when the prospects for commercial profit are poor or nonexistent. The recruitment of specialized and qualified professionals should set higher standards of rigor when they are involved in commercial or unavoidably conflicted relationships and to disseminate the resources evenly, especially when nowadays these are scarce.

Funders and academic institutions are responsible for the moral status, as research usually initiates from there and determines any kind of shift in the process. Academics might be judged on the methodological rigor and full dissemination of their research, the quality of their reports, and the reproducibility of their findings. Previous reports suggest ways to increase the relevance and to optimize resource allocation in biomedical research, indicating how resource allocation should be conducted, along with revisions in the appropriateness of research design, methods, and analysis, with efficient research regulation and management fully accessible information, promoting unbiased and usable reports. Additionally, motivation must be given to authors to share their data [ 67 ], as has been performed in the field of genetics [ 68 ]. Of note, synthesis of evidence on the meta-epidemiological level cannot always confidently provide answers to practical clinical questions [ 69 ].

Compromised ethics should be traced and removed from independent research and academia, while journals should on no occasion put profit and publicity above quality. The solution to this lies on the progressive refinement of methods and improvement of the objective and controlled processes.

13. Training

Essential training and interprofessional learning of clinicians and other hands-on scientists in the medical field are an absolute must. There is a growing need to improve their scientific insight and judgment. Reviewers should learn how to apply an unbiased critical thinking and evaluation of the methods explored, of the study questions, and of the resulting impact towards good clinical practice and human welfare. This not only applies to organizational refinement by the Academic Institutes and Publishing Organizations but also to the scientists themselves to obtain the drive to train, along with methodologists and statisticians, so that specialization and knowledge is shared and every contributor works soundly towards a common cause.

14. Conclusions

Research is a solid foundation for the progression of sciences, and the key importance in maintaining the evolution of knowledge is “contributing and sharing”, but this has to be performed adequately. Although there are several criteria and controlled circumstances under which new data and overviews of data are published, research and publishing methods require continuous readjustments and modifications to ensure quality. An overview of the published literature on women’s health and its relevant subtopics is an excellent paradigm on a crucial field of the different types of research and publications that one may encounter but also an example of the vast variability in information available, not only in terms of results but also in terms of design, analysis, quality of information, and implementation of results. In clinical practice, it is imperative to assess information collectively a researcher, medical expert, funder, reviewer, and patient, and this should encourage the improvement of evidence-based patient management.

This review aimed to present the major nodal points of quality and to propose a combination of interventions at various levels, along with other routes of judgement. We also sought to address potential flaws and pitfalls in research conduct and to provide recommendations upon improvement of study designs/methods and scientific reporting to promote publication quality and stricter criteria for release with support from the appropriate structures. A summary of recommendations towards evidence implementation as presented in Table 1 could comprise valuable guidance to both the health experts and the health service recipients to which these standards are quality criteria. A meticulous study design that promotes the transparency of methods and potential conflicts allows a clear distinction of the pathologies and targeted groups and that provides substantial scientific background should be pursued by both researchers and readers. Robust implementation of the pre-stated methods and approaches of analysis, with active participation of collective fronts tied to the subject, should allow quality output to be published and should add value to the findings. Patient-first and common welfare should be considered throughout in conjunction with supporting and providing evidence on robust outcomes for the improvement of healthcare, that may be facilitated by healthy and network collaborations.

Summary of the recommendations for the steps towards evidence implementation.

How these recommendations should be accounted for, evaluated, and implemented relies on the individual discretion of the reader, the scientist, the author, or any entity affiliated with a publishing organization and should be customized to be applied individually for each specialized academic and scientific field but also tailored across continents and countries. The latter is derived from the realization that research conduct, funding, and even the monitoring authorities of clinical studies rely on nonuniform procedures among countries and unions and conforms to different legal frameworks across countries. Nevertheless, a core of actions, precautions, and a quality exemplar of golden standards should be constructed and widely applied to meet the standards that describe a representative scientific contribution, for example, uniform, widely accepted, and practiced standards through policies, guidelines, and rules on a national and/or international level created either by in-country legislation or by scientific entities; allocation of the resources for their implementation; and mechanisms of control for their application and adherence by all.

In conclusion, multiple steps throughout the long and costly process of trial conduct are prone to bias. Notably, increasing international competition favors faster and cheaper patient recruitment, conduct, and analysis and, in turn, produces questionable research. Literature synthesis through SRs and/or meta-analysis has a primarily retrospective role that guides future research and sheds light on arguable topics but cannot erase the wrongdoings of primary studies, which are often concealed. The “bottom-up” approach of a wide dissemination of information to clinicians, together with practical incentives for stakeholders with competing interests to collaborate, promise to improve women’s healthcare.

Author Contributions

C.S. conceived and designed the study and prepared the manuscript. P.V. and V.K. contributed to the design and reporting of the research. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the first author.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable due to the nature of this study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of interest.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Assessment of NIH Research on Women's Health

This study aims to fill gaps in our understanding of women's health research across all NIH Institutes and Centers. It will analyze how much funding is allocated to research on conditions that affect women specifically or are more common among women, and how these conditions are defined across different stages of life. The study will also assess sex differences and racial health disparities. Ultimately, the study will determine the funding needed to bridge gaps in women's health research at NIH.

Deadline: April 3, 2024

Call for Feedback

The National Academies' Committee on the Assessment of NIH Research on Women’s Health is inviting stakeholders and patients to share their perspectives on gaps in women’s health research, particularly across NIH Institutes and Centers. Please submit your comments by April 3, 2024.

Upcoming Events

Multiday Event | April 11-12, 2024

Publications

No publications are associated with this project at this time.

No projects are underway at this time.

Description

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) will convene an ad hoc committee with specific scientific, ethical, regulatory, and policy expertise to develop a framework for addressing the persistent gaps that remain in the knowledge of women's health research across all NIH Institutes and Centers (ICs). Specifically, the study should be designed to analyze the proportion of research that the NIH funds on conditions that are female-specific and/or more common amongst women or that differently impact women (e.g., different pathophysiology or course of disease), establish how these conditions are defined and ensure that it captures conditions across the lifespan, evaluates sex differences and racial and ethnic health disparities. The committee should define women's health for the purpose of the report, taking into account today's social and cultural climate. Ultimately, the study should determine the appropriate level of funding that is needed to address gaps in women's health research at NIH.

The NASEM consensus committee, as a first step, will conduct an analysis and develop a matrix of identified NIH research on conditions that are female-specific, more common amongst women or that differently impact women, investigating sex differences, and centered on the unique health needs of women.

The committee will make recommendations for the following:

- Research priorities for NIH-supported research on women’s health

- NIH training and education efforts to build, support, and maintain a robust women’s health research workforce

- NIH structure (extra- and intra-mural), systems, review processes to optimize women’s health research

- NIH-wide workforce to effectively solicit, review and support women’s health research

- Allocation of funding needed to address gaps in women's health research at NIH.

The committee will identify metrics to ensure that research is tracked to meet the continuing health needs of women.

- Health and Medicine Division

- Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice

- Board on Health Care Services

- Board on Health Sciences Policy

In Progress

Consensus Study

- Health and Medicine

Contact the Public Access Records Office to make an inquiry, request a list of the public access file materials, or obtain a copy of the materials found in the file.

Committee Membership Roster Comments

Felina Cordova-Marks and Holly A. Ingraham were added on December 6, 2023. Bios were updated for Cheng, Golden, Kaplan, Lane, Salmon, and Secord on December 15, 2023, and for Burke on December 20, 2023. Bios for Cordova-Marks and Kaplan were updated on January 19, 2024. Crystal Schiller was added on January 25, 2024. The bio for Golden was updated on 3/5/2024.

Past Events

Multiday Event | March 7-8, 2024

3:30PM - 4:00PM (ET)

February 27, 2024

[Closed] Assessment of NIH Research on Women's Health: Evaluation criteria work group, Meeting #2

Multiday Event | January 30-31, 2024

[Closed] Assessment of NIH Research on Women's Health: Funding assessment work group, Meeting #1

Multiday Event | January 25-26, 2024

11:00AM - 12:00PM (ET)

January 18, 2024

[Closed] Assessment of NIH Research on Women's Health: Definitions work group, Meeting #1

Rachel Riley

(202) 334-3288

Responsible Staff Officers

- Amy Geller

Additional Project Staff

- Aimee Mead

- Magdaline Anderson

- Luz Brielle Dojer

- Rachel Riley

Women's Health Research Center

Improving the health of women

Mayo Clinic Women's Health Research Center is a leader in providing evidence to improve healthcare for women and educating the next generation of women's health investigators and healthcare professionals.

The Mayo Clinic Women's Health Research Center advances scientific discoveries to improve the health of women through all stages of life.

The center is at the forefront of a new era in women's health, based on the understanding that the female body isn't simply a smaller version of the male form. Women and men have different chromosomes and hormones. Thus, disease risk, diagnosis and response to treatments — including some medicines — are often different for women and men.

Yet current medical treatments are often based on research that was conducted mainly on men. Or, when women were included, the research didn't account for differences between women and men.

Mayo Clinic is transforming women's health by advancing research and studies specifically focused on the unique needs and abilities of the female body through all stages of life.

Investigators in the Women's Health Research Center are studying why certain illnesses occur more often — or sometimes only — in women or manifest differently in women than in men. Armed with this information, healthcare professionals can better prevent, diagnose and treat some of today's most debilitating diseases.

For more than 150 years, Mayo Clinic research has changed the face of medicine, enabling healthcare professionals around the world to provide lifesaving care to millions of people. Now, Mayo is advancing research focused on women's health so that medical care can be personalized for women and men.

Right now, there are more than 1,400 research studies related to women's health across Mayo Clinic campuses in Arizona, Florida and Minnesota. Mayo researchers are dedicated to addressing the health issues women face, with the goal of improving women's health and quality of life.

- View Complete Calendar

Mayo Clinic Women's Health Research Center

Mayo Clinic Women's Health Research Center director Kejal Kantarci, M.D., former director, Virginia M. Miller, Ph.D., and colleagues talk about research in the Women's Health Research Center.

Center leadership

Associate Director

Mayo Clinic Footer

- Request Appointment

- About Mayo Clinic

- About This Site

Legal Conditions and Terms

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Notice of Privacy Practices

- Notice of Nondiscrimination

- Manage Cookies

Advertising

Mayo Clinic is a nonprofit organization and proceeds from Web advertising help support our mission. Mayo Clinic does not endorse any of the third party products and services advertised.

- Advertising and sponsorship policy

- Advertising and sponsorship opportunities

Reprint Permissions

A single copy of these materials may be reprinted for noncommercial personal use only. "Mayo," "Mayo Clinic," "MayoClinic.org," "Mayo Clinic Healthy Living," and the triple-shield Mayo Clinic logo are trademarks of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research.

Women’s Health

Women’s Health Activities

Women’s health science.

Read selected scientific findings and publications regarding the health of women and girls.

Healthy Living

Learn about specific health challenges women and girls face throughout their lifespan.

Women’s Health Features

Women’s Unseen Battle: Shining a Light on Lupus

CDC and partners are working to make lupus visible by raising awareness about this disease. Read on to learn more about lupus among women. Share this information in your community!

Celebrating Women’s Health Week!

National Women’s Health Week starts each year on Mother’s Day to encourage women and girls to make their health a priority. Learn more about how to live a safer and healthier life.

Working Together to Reduce Black Maternal Mortality

Black Maternal Health Week is recognized each year from April 11-17 to bring attention and action in improving Black maternal health. Everyone can play a role in working to prevent pregnancy-related deaths and improving maternal health outcomes.

Supporting Women with Disabilities to Achieve Optimal Health

An estimated 37.5 million women in the U.S. report having a disability. Learn about the challenges women with disabilities experience and how you can help support disability awareness.

Sign up for our free newsletter

Read our latest newsletter.

- Breastfeeding Report Card, United States, 2022

- Gynecologic Cancer Awareness

- Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019

- Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders: Resources for Prevention and Care

- Geographic Examination of COVID-19 Test Percent Positivity and Proportional Change in Cancer Screening Volume, National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program

Journal of Women's Health: Report from the CDC

- Addressing Racial Disparities in Pregnancy-Related Deaths: An Analysis of Maternal Mortality-Related Federal Legislation, 2017–2021

- Surveillance of Hypertension Among Women of Reproductive Age: A Review of Existing Data Sources and Opportunities for Surveillance Before, During, and After Pregnancy

- Summary of Current Guidelines for Cervical Cancer Screening and Management of Abnormal Test Results: 2016–2020

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 13 June 2023

It’s about time to focus on women’s health

Nature Reviews Bioengineering volume 1 , page 379 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1703 Accesses

19 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Biomedical engineering

- Health care

Women’s health has long been overlooked in both fundamental and clinical research, which, sadly, also holds true for the bioengineering field — albeit things are slowly changing.

Only 3.7% of all clinical trials from 2007 to 2020 focused on gynaecology 1 , and there is an undeniable gender disparity in the allocation of research funds 2 ; a disproportionate share of resources is dedicated to diseases that affect primarily males 3 , at the expense of funding for research on conditions that disproportionately affect females , such as pregnancy disorders, autoimmune diseases and reproductive tract disorders. A report by the Global Health Alliances in 2014 suggested that neglect in medical research and funding is directly responsible for delayed diagnosis, severe disease progression and premature death of women 4 . So, it is fair to say that women’s health is overlooked in fundamental and clinical research. Therefore, it is about time for our field to adapt, tailor and optimize our engineered models and platforms for the investigation of the health of individuals who identify as women, regardless of their sex at birth.

“…it is about time for our field to adapt, tailor and optimize our engineered models and platforms for the investigation of the health of individuals who identify as women, regardless of their sex at birth.”

“Before I was diagnosed with lupus, I did not understand that medicine had a gender problem,” writes Elinor Cleghorn at the beginning of her book ‘Unwell Women’ 5 . What follows is her personal story of suffering from undiagnosed pain for years, an experience that is all too familiar for many women affected by lupus and other autoimmune diseases, such as Graves’ disease. Of note, women make up approximately 80% of people with autoimmune diseases 6 . The mechanisms underlying many autoimmune diseases remain to be identified, and, accordingly, their diagnosis and treatment are often delayed and ineffective. The bioengineering field has put great effort into investigating, manipulating and engineering the immune system, resulting in notable progress in immunotherapy, vaccine technologies and in vitro immune tissue models. The same immunoengineering efforts could be dedicated to the investigation of autoimmune diseases; for example, to improve the early detection of lupus, biomaterial models can be designed to study how immune cells interact with blood vessels to shed light on the pathogenesis of this disease 7 .

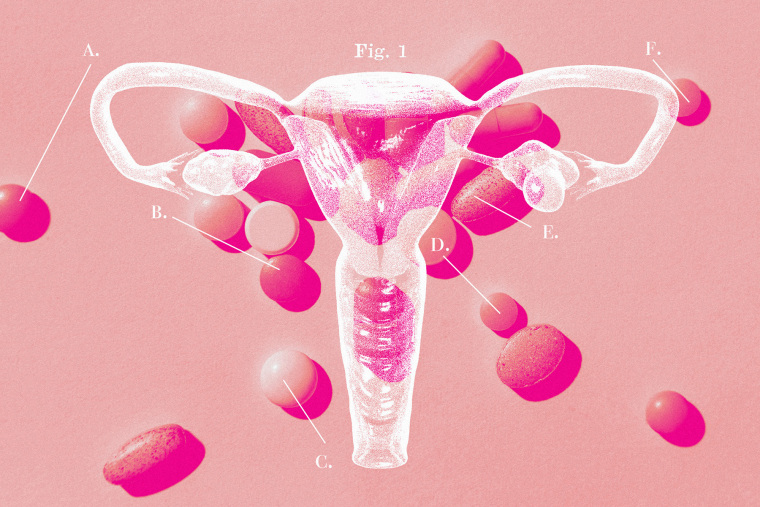

Endometriosis, which is a chronic disease that affects roughly 10% (190 million) of reproductive age women and girls globally , is associated with severe, life-impacting pain. Yet, diagnosis of endometriosis remains difficult and there is currently no known cure. A key strength of bioengineering is the design of in vitro models, such as organoids and organs-on-chips, to investigate disease and test drugs. Such model systems can also be designed for modelling the endometrium to investigate diagnostic tools and treatments for endometriosis; for example, endometrial organoids can be derived from menstrual flow to non-invasively diagnose endometriosis 8 , or they can be engineered from human tissue-derived cells using synthetic matrices 9 . The progress made in the design of clinically relevant in vitro models is reflected in the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Modernization Act 2.0, authorizing the use of certain alternatives, including cell-based assays, to animal testing. Therefore, research efforts in optimizing endometrial organoids may well result in the development of new diagnosis and treatment strategies for endometriosis.

Similarly, the advanced design of drug delivery systems has contributed to breakthroughs in the treatment and prevention of many diseases. However, these systems rarely consider the barriers, challenges and microenvironments unique to the female body 10 . In this issue, Michael J. Mitchell and colleagues discuss the design and optimization of therapeutic nanoparticle and biomaterial systems to deliver drugs for the treatment of conditions in non-pregnant and pregnant women. Importantly, the authors emphasize that drug delivery systems intended for the treatment of women’s health conditions must be specifically engineered to penetrate female-specific biological barriers, such as the vaginal mucosa, and potentially consider placental transport, and maternal and fetal safety. Nanoscale systems can now be designed to overcome complex biological barriers (even the blood–brain barrier) and target specific tissues and cells in the human body — the next challenge should be to study and tailor their behaviour in the female body.

The list could go on — from menopause and long COVID to accounting for the role of sex in tissue engineering. There is lots to tackle for the bioengineering community.

Steinberg, J. R. et al. Early discontinuation, results reporting, and publication of gynecology clinical trials from 2007 to 2020. Obstet. Gynecol. 139 , 821–831 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

[No authors listed]. Women’s health: end the disparity in funding. Nature 617 , 8 (2023).

Mirin, A. A. Gender disparity in the funding of diseases by the U.S. National Institutes of Health. J. Womens Health 30 , 956–963 (2021).

Bonita, R. & Beaglehole, R. Women and NCDs: overcoming the neglect. Glob. Health Action 7 , 1 (2014).

Cleghorn, E. Unwell Women: A Journey Through Medicine and Myth in a Man-Made World (W&N, 2021).

Invernizzi, P., Pasini, S., Selmi, C., Gershwin, M. E. & Podda, M. Female predominance and X chromosome defects in autoimmune diseases. J. Autoimmun. 33 , 12–16 (2009).

Silberman, J. et al. Modeled vascular microenvironments: immune-endothelial cell interactions in vitro. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 11 , 2482–2495 (2021).

Cindrova-Davies, T. et al. Menstrual flow as a non-invasive source of endometrial organoids. Commun. Biol. 4 , 651 (2021).

Hernandez-Gordillo, V. et al. Fully synthetic matrices for in vitro culture of primary human intestinal enteroids and endometrial organoids. Biomaterials 254 , 120125 (2020).

Poley, M. et al. Sex-based differences in the biodistribution of nanoparticles and their effect on hormonal, immune, and metabolic function. Adv. NanoBiomed Res. 2 , 2200089 (2022).

Download references

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

It’s about time to focus on women’s health. Nat Rev Bioeng 1 , 379 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44222-023-00081-1

Download citation

Published : 13 June 2023

Issue Date : June 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s44222-023-00081-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- For Consumers

- Women's Health

- Women's Health Research

- About OWH Research

Women's Health Research Roadmap

From the FDA Office of Women's Health (OWH)

On this page: About the roadmap | Research priority areas | Related links

Download the Research Roadmap (PDF, 9.20 MB)

About the Women’s Health Research Roadmap

A strategy for science and innovation to improve the health of women

Since its inception, the FDA Office of Women’s Health (OWH) has worked closely with FDA’s centers to expand existing research projects and foster new collaborations related to advancing the science of women’s health. OWH has also worked with other government agencies, academia, women’s research organizations, and other stakeholders to foster and facilitate research projects and scientific forums. These combined efforts have helped to advance our understanding of women’s health issues. They have furthered the development of new tools and approaches for informing FDA decisions about the harm or the safety and effectiveness of FDA-regulated products that are used not only by women, but by all Americans.

The Women’s Health Research Roadmap builds on knowledge gained from previously funded research and is intended to assist OWH in coordinating future research activities with other FDA research programs and with external partners. The Roadmap outlines priority areas where new or enhanced research is needed. Although many critical women’s health issues may warrant further examination, future OWH-funded research should focus on areas where advancements will be directly relevant to FDA as it makes regulatory decisions. The Roadmap creates strategic direction for OWH to help maximize the impact of OWH initiatives and ultimately promote optimal health for women.

Research priority areas

- Advance safety and efficacy : Advance the safety and efficacy and reduce the toxicity of FDA-regulated products used by women

- Improve clinical study design and analyses : Improve clinical study design and conduct to better identify and evaluate possible sex differences related to FDA-regulated products

- Novel modeling and simulation approaches : Evaluate and promote the adoption of novel modeling and simulation approaches that can aid in regulatory evaluation of FDA-regulated products

- Advances in biomarker science : Develop tools and methods that can help identify, evaluate, and qualify predictive or prognostic clinical and non-clinical biomarkers and surrogate endpoints

- Expand data sources and analysis : Identify, develop, and evaluate data sources and efficient techniques for data mining, data linkage, and large data set analysis that can be used to assess the postmarket toxicity or the safety and effectiveness of FDA-regulated products

- Improve health communications : Develop, evaluate, and use tools and methods to foster the creation and easy availability of clear and useful information about FDA-regulated products used by women to help women and their health care professionals make informed health-related decisions

- Emerging technologies : Support the identification of sex differences related to the use of emerging technologies

Related links

- OWH information on BAA funding

- Extramural Research - Women's Health (including funding information)

- Annual Awards

- Mission and Vision

- Share Your Story

- Women’s Health Research

- Board of Directors

- Collaborations

- Partner with SWHR

- Philanthropy

- Job Opportunities

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Endometriosis and Fibroids

- Roundtables

- Science Events

- Advisory Council

- Women’s Health Policy Agenda

- Position Statements

- Policy Letters

- Legislation

- Policy Events

- Read My Lips

- Women’s Health Equity Initiative

- Coronavirus

- Publications

- Peer-Reviewed Articles

- Guides & Toolkits

- SWHR in the News

- Read Women’s Health Stories

- Annual Awards 2024

- Annual Awards 2023

- Annual Awards 2018-2022

Home » About » Women’s Health Research

Women’s health Research

What is women’s health research.

Women’s health research is the study of health across a woman’s lifespan in order to preserve wellness and to prevent, diagnose, and treat disease. It includes all health conditions for which women and men experience differences in risk, presentation, and treatment response, as well as health issues specific to women, such as pregnancy and menopause.

Women’s health research considers both sex and gender differences and how these differences affect disease risk, pathophysiology, symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment.

Sex vs. gender

What’s the difference.

While the terms sex and gender are often used interchangeably in society, they have distinct definitions that apply in scientific research. Both sex and gender are variables that should be considered in scientific research, from the development and design of studies to the analysis and reporting of study results.

is a multidimensional biological construct based on anatomy, physiology, genetics, and hormones. These components are sometimes referred to together as “sex traits.”

is broadly defined as a multidimensional construct that encompasses gender identity and expression, as well as social and cultural expectations about status, characteristics, and behavior as they are associated with certain sex traits. Understandings of gender vary throughout historical and cultural contexts.

the health gap for women

Until about 25 years ago, essentially all health research was conducted on men..

Women were actively excluded from participating in most clinical trials. Why? Because of the persistent idea that female hormonal cycles were too difficult to manage in experiments — including the fear of harming potential pregnancies — and that using only one sex would reduce variation in results. This exclusion of females in health research wasn’t just limited to humans. It extended to research on female animals, cells, and tissue. Researchers assumed that they could simply extrapolate their male-only study results to females, a dangerous precedent that overlooked fundamental differences between women and men.

Fortunately, thanks to advocacy by the Society for Women’s Health Research and other groups, Congress passed the National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993, mandating the inclusion of women and minorities in NIH-funded clinical trials. In the same year, the Food and Drug Administration changed its policies to require the inclusion of women in efficacy studies and in the analysis of data on sex differences.

Then, in 2016, the NIH implemented a new policy stating that sex as a biological variable should be factored into preclinical research and reporting in vertebrate animal and human studies. Today, all NIH-funded researchers must either include both female and male research subjects or explain why they do not.

Although researchers have been playing catch-up for the past couple of decades, this longtime bias put the health of women at risk and created a huge gap in knowledge about women’s health and the role that differences between women and men play in health and disease.

Differences exist

The biological differences between women and men go beyond basic anatomy. Researchers must consider sex differences down to the cellular level in order to discover crucial information about the varied development, function, and biology between women and men.

of women with sleep apnea go undiagnosed

because they may not report the same “textbook” symptoms as men.

of those with Alzheimer’s disease are women

and some research suggests women are at greater risk for AD than men.

of people with osteoporosis are women

and they experience rapid bone loss at menopause due to hormonal changes.

The Inclusion of Women in Research

1977 · The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) bars women of child bearing potential from participating in most early phase clinical research.

1985 · A United States Public Health Service task force concludes that exclusion of women from clinical research was detrimental to women’s health.

1986 · The National Institutes of Health (NIH) adopts guidelines urging the inclusion of women in NIH-sponsored clinical research.

1990 · The Society for Women’s Health Research is founded and asks the General Accounting Office (GAO) to examine whether NIH is following its 1986 guideline.

1990 · A GAO report reveals that the NIH guidelines are not being followed. The Physician’s Health or “aspirin” study, designed to examine the impact of taking aspirin on cardiovascular disease, is one of many large studies not included women highlighted by the report.

1993 · The NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 mandates that the NIH must ensure that women and members of minorities and their subpopulations are included in all human subject research. 1993 · The FDA rescinds earlier guidelines barring the participation of women with child-bearing potential from most early phase research.

2000 · The GAO concludes that although women are now included in clinical research proportionate to their representation in the population, analysis by sex of subjects is rare.

2001 · The GAO concludes FDA not effectively monitoring research data to determine how sex differences affect drug safety and effectiveness.

2006 · The Organization for the Study of Sex Differences is established. It is the brain child of basic and clinical scientists with established research commitments to the study of sex differences, and staff members of SWHR.

2012 · Food and Drug Administration Safety and Innovation Act (FDASIA) signed into law, requiring FDA to provide a special report and accounting of trials by sex, race, and ethnicity.

2014 · The National Institutes of Health (NIH) enact new policies to address sex differences by will be requiring applicants to report their cell and animal inclusion plans as part of preclinical experimental design.

2015 · The FDA launched the website Drug Trials Snapshots that provide consumers with information about who participated in clinical trials that supported the FDA approval of new drugs. The site is is part of an overall FDA effort to make demographic data more available and transparent.

2016 · NIH implemented a policy that expects scientists to account for the possible role of sex as a biological variable (SABV) in vertebrate animal and human studies.

Both sex and gender influence health across the lifespan, and SWHR strives to comprehensively address both sex and gender as they relate to women’s health. When citing research, SWHR uses terminology consistent with what is used in the cited study. As inclusive language practices continue to evolve in the scientific and medical communities, we will reassess our language as usage to promote accuracy and inclusivity. Please note that not all language will be updated retroactively.

SWHR acknowledges that there are valued groups of people that may benefit from our materials who do not identify as women. We encourage those who identify differently to engage with us and our content.

- Departments & Services

- Directions & Parking

- Medical Records

- Physical Therapy (PT)

- Primary Care

Header Skipped.

- Department of Medicine

Division of Women's Health

Division of women's health research.

The Division of Women’s Health’s research goals are: to lead scientific and clinical discoveries that identify and explain sex- and gender-based differences in health and disease, prioritize disorders specific to women, and ultimately improve the overall health and access to care for women and men. Faculty in the Division of Women’s Health pursue a wide range of research topics dedicated to advancing knowledge of women’s health and sex differences in health and disease. To learn more about specific research programs and areas, visit our research website: Women's Health Research .

Research Areas

- Cancer Screening & Prevention

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Clinical Neuroscience & Neuroendocrinology

- Gender, Violence & Trauma

- Global Women’s Health

- Life Course & Reproductive Epidemiology

- Women’s Health Policy Research & Advocacy

Research Faculty

- Kathryn Rexrode, MD, MPH Professor of Medicine Division Chief

- Laura Holsen, PhD Assistant Professor of Psychiatry

- Ingrid Katz, MD, MHSc Associate Professor of Medicine

- Annie Lewis-O'Connor, MSN, MPH, PhD Instructor in Medicine

- Roseanna Means, MD Associate Professor of Medicine, Part-time

- Lydia Pace, MD, MPH Assistant Professor of Medicine

- Alexandra Purdue-Smithe, PhD Instructor in Medicine

- Janet Rich-Edwards, ScD, MPH Associate Professor of Medicine

- Eve Rittenberg, MD Assistant Professor of Medicine

- Meghan Rudder, MD Instructor in Medicine

- Hanni Stoklosa, MD, MPH Instructor in Medicine

- Jennifer J. Stuart, ScD Instructor in Medicine

Affiliate Faculty

- Deborah Bartz, MD, MPH

- Kari Braaten, MD, MPH

- Ann Celi, MD

- Ming Hui Chen, MD, MMSc, FACC, FASE

- Alisa Goldberg, MD, MPH

- Jill Goldstein, PhD

- Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, MPH

- Elizabeth Janiak, ScD

- Tamara Bockow Kaplan, MD

- Bharti Khurana, MD

- Nomi Levy-Carrick, MD

- Rose L. Molina, MD, MPH

- Maria Nardell, MD

- Jennifer Scott, MD, MBA, MPH

- Caren Solomon, MD, MPH

- Paula Emma Voinescu, MD, PhD

Learn more about Brigham and Women's Hospital

For over a century, a leader in patient care, medical education and research, with expertise in virtually every specialty of medicine and surgery.

Stay Informed. Connect with us.

- X (formerly Twitter)

- Current Projects

- Yale OCD Research Clinic

- Publications

INFORMATION FOR

- Residents & Fellows

- Researchers

25 Years of Women’s Health Research at Yale

Making every year count, 25 years of women's health research at yale.

Women's Health Research at Yale marks 25 years of investigating conditions of high morbidity and mortality in women and understanding sex and gender differences that affect health outcomes.

Google came online the same year Women’s Health Research at Yale (WHRY) was created. Each, as it turned out, would fill a void in the search for information.

It was 1998, soon after the National Institutes of Health issued a grant requirement that women be included as participants in clinical research. Without this requirement, the existing gap in what was known about the health of women would continue. This directive also meant that the largest single funder of biomedical research in the world was changing the ground rules about who was studied and calling for data on the health of women beyond the existing focus of reproductive health.

And so, the search for information began.

Through our Pilot Project Program, WHRY began generating studies on the causes, mechanisms, and interventions for the health conditions that affect women and broadening the scope of what was considered women’s health. These studies also allowed Yale faculty to collect the necessary feasibility data required to secure new NIH grants for further study on the wide span of critical women’s health topics.

With one of the first pilot project grants, Bruce Haffty, MD, Professor of Therapeutic Radiology, found, in a rare 15-year follow-up study of women with breast cancer, that women with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations were more likely to develop breast cancer recurrence in either breast than women without this genetic risk factor. These findings became crucially important to women weighing treatment options at the time of diagnosis and developing plans for follow-up.

Dr. Haffty’s study was one of many that demonstrated rapid benefit derived from our pilot studies. Another offered girls with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) a new treatment option. Traditionally, girls with ASD have been under-represented in research. Pamela Ventola, PhD, Associate Professor in the Child Study Center, demonstrated that Pivotal Response Therapy (PRT), a social-behavioral treatment could help girls, along with boys, with ASD. Dr. Ventola showed that girls benefited from PRT and made larger net gains than did boys, resulting in its therapeutic use today in both girls and boys.

Similar to an internet search, some research studies can provide swift answers, while others require longer investigation. Here’s an example of research that requires a longer-term commitment.

Previous studies have shown women have a higher risk for parathyroid disorders, such as hypoparathyroidism in which insufficient parathyroid hormone is secreted. Women are also more likely to develop thyroid cancer requiring surgical treatment, which often comes with the unintended consequence of damage to the parathyroid glands. In either case, lifelong hypoparathyroidism can result. This means that parathyroid hormone is not available to maintain needed calcium levels in the blood. Without proper calcium levels, patients are at risk for painful muscle spasms, seizures, and brain fog when the condition is mild and can develop a life-threatening calcium deficiency when it is severe. Treating hypoparathyroidism with calcium supplements, which is the standard of care, is often ineffective for maintaining the proper calcium balance, in addition to causing unwanted side effects.

As the Associate Director of Yale’s Stem Cell Center, Diane Krause, MD, PhD, Anthony N. Brady Professor of Laboratory Medicine, has taken on the intensive work of turning patients’ stem cells into parathyroid cells to give patients the capacity to produce parathyroid hormone on their own. The round-the-clock effort is a multi-year process involving five stages of development. Dr. Krause and her team established a protocol to orchestrate the molecular cues that mimic the natural development process of turning stem cells into parathyroid cells. This protocol, which will provide a revolutionary new treatment option, has been validated in collaborating laboratories, and is now being fine-tuned to improve the efficiency of parathyroid cell differentiation.

Dr. Krause’s work is the result of believing that the current standard of treatment can be improved. She is among the many researchers who have used WHRY’s Pilot Project Program seed grants to explore novel ideas and shape the future of health care.

Samit Shah, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor of Medicine (Cardiology) focused his grant on creating a new approach to improve the diagnosis of heart disease in women. Most heart attacks in women and men are due to blockage of major cardiac arteries, thus preventing blood flow to the heart. However, chest pain and heart attacks can also be caused by constriction or spasm of the small vessels that feed the heart. Known as microvascular disease, this cause is more common in women and it is not detected by routine diagnostic protocols that are designed to detect major blockages. Consequently, women are more likely to be left without a diagnosis or appropriate treatment. Dr. Shah’s research focuses on this physiological difference between women and men and, if a cholesterol blockage is not found during cardiac catheterization, he uses specialized techniques to determine whether there is another cause of reduced blood flow, such as microvascular disease. In women without blockages, nearly 90 percent of women who underwent testing were found to have a cause of reduced blood flow to the heart, despite having no significant plaque blockage in the large blood vessels. This advanced testing helps patients find an accurate diagnosis and allows providers to develop precision treatment plans.

Other novel advances in treating a particular disease have now turned out to be useful for other disorders. For example, the innovative approach used in two different pilot studies by Akiko Iwasaki, PhD, Sterling Professor of Immunobiology, to treat herpes infections is now being applied to the fight against Covid-19. In her first WHRY study, Dr. Iwasaki focused her research on the role of mucous membranes in understanding why women are more susceptible than men to viral genital herpes infections. Her second study expanded upon that knowledge and created a treatment strategy dubbed “prime and pull” that would prime the immune system to create a memory response to the herpes simplex virus and then pull those immune memory cells to the site of infection to stop the virus. In a third WHRY study at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Iwasaki showed sex differences in immune response to the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus and is now using her combined expertise on this virus and viral transmission to develop an intranasal vaccine to create mucosal immunity that would stop the virus at the site of infection – the nasal muscosa.

The importance of ingenuity in scientific discovery is also evident in the ovarian and breast cancer research by Peter Glazer, MD, PhD, Robert E. Hunter Professor of Therapeutic Radiology. Dr. Glazer, along with James Hansen, MD, began investigating a nontoxic lupus antibody that can penetrate cancer cells for its potential as a mechanism for cancer treatment. In his WHRY study, he found that this specific lupus antibody could be used to inhibit the DNA repair component of the cancer cell in a manner that stops the cancer cell from sustaining itself. Further research showed efficacy in the antibody destroying specifically those cancer cells associated with mutations in the tumor suppressing BRCA1/2 genes. As mutations in these BRCA genes lead to higher rates of breast and ovarian cancer, this research is of great value for BRCA-related cancers that affect many women around the world. The antibody has now been developed into a therapy to fight these cancers and clinical trials are planned for later this year.

Women’s Health Research at Yale’s search for information began 25 years ago to address the scarcity of information on women’s health. It has led to knowledge on a myriad of conditions and uncovered vital sex and gender differences that influence the health of all people.

As this sampling of WHRY funded studies show, there is much to learn that can advance the health of women and men. And so, the search continues.

- Basic Science Research

- Clinical research

- Cardiology and Vascular

- Ovarian Cancer

- Breast Cancer

- Immunology & Immunobiology

- Translational Research

- Heart Disease

Featured in this article

- Carolyn M. Mazure, PhD Norma Weinberg Spungen and Joan Lebson Bildner Professor in Women's Health Research and Professor of Psychiatry and of Psychology

- Bruce Haffty, MD

- Diane Krause, MD, PhD Anthony N. Brady Professor of Laboratory Medicine and Professor of Pathology; Vice Chair for Research Affairs, Laboratory Medicine; Assoc. Director, Yale Stem Cell Center; Assoc. Director, Transfusion Medicine Service; Medical Director, Clinical Cell Processing Laboratory; Medical Director, Advanced Cell Therapy Laboratory

- Samit Shah, MD, PhD, FACC, FSCAI Assistant Professor of Medicine; Director, VA Connecticut Cardiac Catheterization Laboratory

- Akiko Iwasaki, PhD Sterling Professor of Immunobiology and Professor of Dermatology and of Molecular, Cellular, and Developmental Biology and of Epidemiology (Microbial Diseases); Investigator, Howard Hughes Medical Institute

- Peter M. Glazer, MD, PhD Robert E. Hunter Professor of Therapeutic Radiology and Professor of Genetics; Chair, Therapeutic Radiology

- Pamela Ventola, PhD Associate Professor Child Study Center

- Frontiers in Communication

- Health Communication

- Research Topics

Centering Women, Health, and Health Equity in Health Communication

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

Gendered patterns of labor and ongoing patriarchal attitudes mean that women’s voices, worldviews, and cultural frames of reference are systematically neglected in the production of health knowledge and communication around health. For example, male-identified researchers tend to produce far more research on ...

Keywords : Health Equity, Gender, Women, Race, Critical Cultural Communication, Health communication