25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Sustainable Development: Samples in 250, 300 and 500 Words

- Updated on

- Nov 18, 2023

On 3rd August 2023, the Indian Government released its Net zero emissions target policy to reduce its carbon footprints. To achieve the sustainable development goals (SDG) , as specified by the UN, India is determined for its long-term low-carbon development strategy. Selfishly pursuing modernization, humans have frequently compromised with the requirements of a more sustainable environment.

As a result, the increased environmental depletion is evident with the prevalence of deforestation, pollution, greenhouse gases, climate change etc. To combat these challenges, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change launched the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP) in 2019. The objective was to improve air quality in 131 cities in 24 States/UTs by engaging multiple stakeholders.

‘Development is not real until and unless it is sustainable development.’ – Ban Ki-Moon

The concept of Sustainable Development in India has even greater relevance due to the controversy surrounding the big dams and mega projects and related long-term growth. Since it is quite a frequently asked topic in school tests as well as competitive exams , we are here to help you understand what this concept means as well as the mantras to drafting a well-written essay on Sustainable Development with format and examples.

This Blog Includes:

What is sustainable development, 250-300 words essay on sustainable development, 300 words essay on sustainable development, 500 words essay on sustainable development, introduction, conclusion of sustainable development essay, importance of sustainable development, examples of sustainable development.

As the term simply explains, Sustainable Development aims to bring a balance between meeting the requirements of what the present demands while not overlooking the needs of future generations. It acknowledges nature’s requirements along with the human’s aim to work towards the development of different aspects of the world. It aims to efficiently utilise resources while also meticulously planning the accomplishment of immediate as well as long-term goals for human beings, the planet as well and future generations. In the present time, the need for Sustainable Development is not only for the survival of mankind but also for its future protection.

Looking for ideas to incorporate in your Essay on Sustainable Development? Read our blog on Energy Management – Find Your Sustainable Career Path and find out!

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 250-300 words:

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 300 + words:

Must Read: Article Writing

To give you an idea of the way to deliver a well-written essay, we have curated a sample on sustainable development below, with 500 + words:

Essay Format

Before drafting an essay on Sustainable Development, students need to get familiarised with the format of essay writing, to know how to structure the essay on a given topic. Take a look at the following pointers which elaborate upon the format of a 300-350 word essay.

Introduction (50-60 words) In the introduction, students must introduce or provide an overview of the given topic, i.e. highlighting and adding recent instances and questions related to sustainable development. Body of Content (100-150 words) The area of the content after the introduction can be explained in detail about why sustainable development is important, its objectives and highlighting the efforts made by the government and various institutions towards it. Conclusion (30-40 words) In the essay on Sustainable Development, you must add a conclusion wrapping up the content in about 2-3 lines, either with an optimistic touch to it or just summarizing what has been talked about above.

How to write the introduction of a sustainable development essay? To begin with your essay on sustainable development, you must mention the following points:

- What is sustainable development?

- What does sustainable development focus on?

- Why is it useful for the environment?

How to write the conclusion of a sustainable development essay? To conclude your essay on sustainable development, mention why it has become the need of the hour. Wrap up all the key points you have mentioned in your essay and provide some important suggestions to implement sustainable development.

The importance of sustainable development is that it meets the needs of the present generations without compromising on the needs of the coming future generations. Sustainable development teaches us to use our resources in the correct manner. Listed below are some points which tell us the importance of sustainable development.

- Focuses on Sustainable Agricultural Methods – Sustainable development is important because it takes care of the needs of future generations and makes sure that the increasing population does not put a burden on Mother Earth. It promotes agricultural techniques such as crop rotation and effective seeding techniques.

- Manages Stabilizing the Climate – We are facing the problem of climate change due to the excessive use of fossil fuels and the killing of the natural habitat of animals. Sustainable development plays a major role in preventing climate change by developing practices that are sustainable. It promotes reducing the use of fossil fuels which release greenhouse gases that destroy the atmosphere.

- Provides Important Human Needs – Sustainable development promotes the idea of saving for future generations and making sure that resources are allocated to everybody. It is based on the principle of developing an infrastructure that is can be sustained for a long period of time.

- Sustain Biodiversity – If the process of sustainable development is followed, the home and habitat of all other living animals will not be depleted. As sustainable development focuses on preserving the ecosystem it automatically helps in sustaining and preserving biodiversity.

- Financial Stability – As sustainable development promises steady development the economies of countries can become stronger by using renewable sources of energy as compared to using fossil fuels, of which there is only a particular amount on our planet.

Mentioned below are some important examples of sustainable development. Have a look:

- Wind Energy – Wind energy is an easily available resource. It is also a free resource. It is a renewable source of energy and the energy which can be produced by harnessing the power of wind will be beneficial for everyone. Windmills can produce energy which can be used to our benefit. It can be a helpful source of reducing the cost of grid power and is a fine example of sustainable development.

- Solar Energy – Solar energy is also a source of energy which is readily available and there is no limit to it. Solar energy is being used to replace and do many things which were first being done by using non-renewable sources of energy. Solar water heaters are a good example. It is cost-effective and sustainable at the same time.

- Crop Rotation – To increase the potential of growth of gardening land, crop rotation is an ideal and sustainable way. It is rid of any chemicals and reduces the chances of disease in the soil. This form of sustainable development is beneficial to both commercial farmers and home gardeners.

- Efficient Water Fixtures – The installation of hand and head showers in our toilets which are efficient and do not waste or leak water is a method of conserving water. Water is essential for us and conserving every drop is important. Spending less time under the shower is also a way of sustainable development and conserving water.

- Sustainable Forestry – This is an amazing way of sustainable development where the timber trees that are cut by factories are replaced by another tree. A new tree is planted in place of the one which was cut down. This way, soil erosion is prevented and we have hope of having a better, greener future.

Related Articles

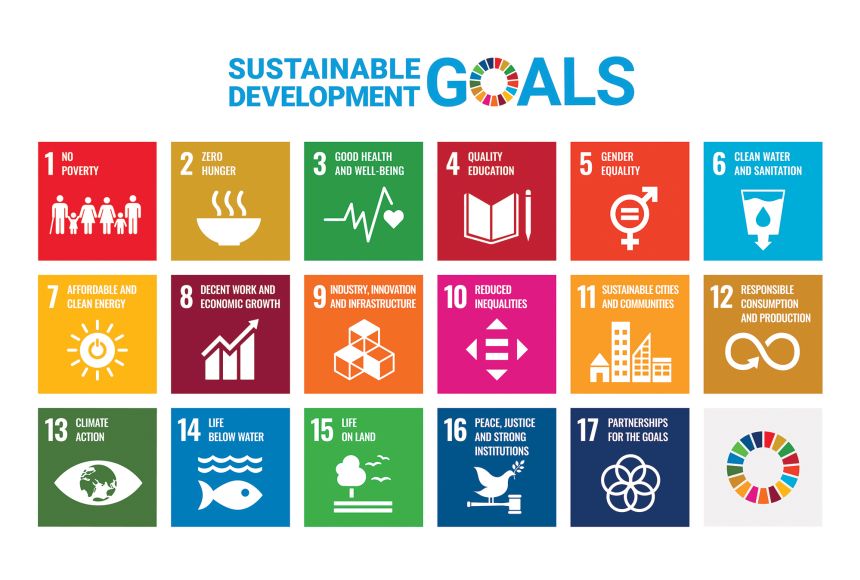

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a set of 17 global goals established by the United Nations in 2015. These include: No Poverty Zero Hunger Good Health and Well-being Quality Education Gender Equality Clean Water and Sanitation Affordable and Clean Energy Decent Work and Economic Growth Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure Reduced Inequality Sustainable Cities and Communities Responsible Consumption and Production Climate Action Life Below Water Life on Land Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions Partnerships for the Goals

The SDGs are designed to address a wide range of global challenges, such as eradicating extreme poverty globally, achieving food security, focusing on promoting good health and well-being, inclusive and equitable quality education, etc.

India is ranked #111 in the Sustainable Development Goal Index 2023 with a score of 63.45.

Hence, we hope that this blog helped you understand the key features of an essay on sustainable development. If you are interested in Environmental studies and planning to pursue sustainable tourism courses , take the assistance of Leverage Edu ’s AI-based tool to browse through a plethora of programs available in this specialised field across the globe and find the best course and university combination that fits your interests, preferences and aspirations. Call us immediately at 1800 57 2000 for a free 30-minute counselling session

Team Leverage Edu

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Thanks a lot for this important essay.

NICELY AND WRITTEN WITH CLARITY TO CONCEIVE THE CONCEPTS BEHIND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY.

Thankyou so much!

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

Sustainable Development Essay

500+ words essay on sustainable development.

Sustainable development is a central concept. It is a way of understanding the world and a method for solving global problems. The world population continues to rise rapidly. This increasing population needs basic essential things for their survival such as food, safe water, health care and shelter. This is where the concept of sustainable development comes into play. Sustainable development means meeting the needs of people without compromising the ability of future generations. In this essay on sustainable development, students will understand what sustainable development means and how we can practise sustainable development. Students can also access the list of CBSE essay topics to practise more essays.

What Does Sustainable Development Means?

The term “Sustainable Development” is defined as the development that meets the needs of the present generation without excessive use or abuse of natural resources so that they can be preserved for the next generation. There are three aims of sustainable development; first, the “Economic” which will help to attain balanced growth, second, the “Environment”, to preserve the ecosystem, and third, “Society” which will guarantee equal access to resources to all human beings. The key principle of sustainable development is the integration of environmental, social, and economic concerns into all aspects of decision-making.

Need for Sustainable Development?

There are several challenges that need attention in the arena of economic development and environmental depletion. Hence the idea of sustainable development is essential to address these issues. The need for sustainable development arises to curb or prevent environmental degradation. It will check the overexploitation and wastage of natural resources. It will help in finding alternative sources to regenerate renewable energy resources. It ensures a safer human life and a safer future for the next generation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the need to keep sustainable development at the very core of any development strategy. The pandemic has challenged the health infrastructure, adversely impacted livelihoods and exacerbated the inequality in the food and nutritional availability in the country. The immediate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic enabled the country to focus on sustainable development. In these difficult times, several reform measures have been taken by the Government. The State Governments also responded with several measures to support those affected by the pandemic through various initiatives and reliefs to fight against this pandemic.

How to Practise Sustainable Development?

The concept of sustainable development was born to address the growing and changing environmental challenges that our planet is facing. In order to do this, awareness must be spread among the people with the help of many campaigns and social activities. People can adopt a sustainable lifestyle by taking care of a few things such as switching off the lights when not in use; thus, they save electricity. People must use public transport as it will reduce greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution. They should save water and not waste food. They build a habit of using eco-friendly products. They should minimise waste generation by adapting to the principle of the 4 R’s which stands for refuse, reduce, reuse and recycle.

The concept of sustainable development must be included in the education system so that students get aware of it and start practising a sustainable lifestyle. With the help of empowered youth and local communities, many educational institutions should be opened to educate people about sustainable development. Thus, adapting to a sustainable lifestyle will help to save our Earth for future generations. Moreover, the Government of India has taken a number of initiatives on both mitigation and adaptation strategies with an emphasis on clean and efficient energy systems; resilient urban infrastructure; water conservation & preservation; safe, smart & sustainable green transportation networks; planned afforestation etc. The Government has also supported various sectors such as agriculture, forestry, coastal and low-lying systems and disaster management.

Students must have found this essay on sustainable development useful for practising their essay writing skills. They can get the study material and the latest updates on CBSE/ICSE/State Board/Competitive Exams, at BYJU’S.

Frequently Asked Questions on Sustainable development Essay

Why is sustainable development a hot topic for discussion.

Environment change and constant usage of renewable energy have become a concern for all of us around the globe. Sustainable development must be inculcated in young adults so that they make the Earth a better place.

What will happen if we do not practise sustainable development?

Landfills with waste products will increase and thereby there will be no space and land for humans and other species/organisms to thrive on.

What are the advantages of sustainable development?

Sustainable development helps secure a proper lifestyle for future generations. It reduces various kinds of pollution on Earth and ensures economic growth and development.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

Counselling

Sustainable Development Goals

The Sustainable Development Goals were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 as a call-to-action for people worldwide to address five critical areas of importance by 2030: people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership.

Biology, Health, Conservation, Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, Civics

Set forward by the United Nations (UN) in 2015, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) are a collection of 17 global goals aimed at improving the planet and the quality of human life around the world by the year 2030.

Image courtesy of the United Nations

In 2015, the 193 countries that make up the United Nations (UN) agreed to adopt the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The historic agenda lays out 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and targets for dignity, peace, and prosperity for the planet and humankind, to be completed by the year 2030. The agenda targets multiple areas for action, such as poverty and sanitation , and plans to build up local economies while addressing people's social needs.

In short, the 17 SDGs are:

Goal 1: No Poverty: End poverty in all its forms everywhere.

Goal 2: Zero Hunger: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture.

Goal 3: Good Health and Well-being: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

Goal 4: Quality Education: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.

Goal 5: Gender Equality : Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

Goal 6: Clean Water and Sanitation: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

Goal 7: Affordable and Clean Energy: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.

Goal 8: Decent Work and Economic Growth: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.

Goal 9: Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation.

Goal 10: Reduced Inequality : Reduce in equality within and among countries.

Goal 11: Sustainable Cities and Communities: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production: Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.

Goal 13: Climate Action: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

Goal 14: Life Below Water: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.

Goal 15: Life on Land: Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.

Goal 16: Peace, Justice , and Strong Institutions: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable, and inclusive institutions at all levels.

Goal 17: Partnerships to Achieve the Goal: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.

The SDGs build on over a decade of work by participating countries. In essence, the SDGs are a continuation of the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), which began in the year 2000 and ended in 2015. The MDGs helped to lift nearly one billion people out of extreme poverty, combat hunger, and allow more girls to attend school. The MDGs, specifically goal seven, helped to protect the planet by practically eliminating global consumption of ozone-depleting substances; planting trees to offset the loss of forests; and increasing the percent of total land and coastal marine areas worldwide. The SDGs carry on the momentum generated by the MDGs with an ambitious post-2015 development agenda that may cost over $4 trillion each year. The SDGs were a result of the 2012 Rio+20 Earth Summit, which demanded the creation of an open working group to develop a draft agenda for 2015 and onward.

Unlike the MDGs, which relied exclusively on funding from governments and nonprofit organizations, the SDGs also rely on the private business sector to make contributions that change impractical and unsustainable consumption and production patterns. Novozymes, a purported world leader in biological solutions, is just one example of a business that has aligned its goals with the SDGs. Novozymes has prioritized development of technology that reduces the amount of water required for waste treatment. However, the UN must find more ways to meaningfully engage the private sector to reach the goals, and more businesses need to step up to the plate to address these goals.

Overall, limited progress has been made with the SDGs. According to the UN, many people are living healthier lives now compared to the start of the millennium, representing one area of progress made by the MDGs and SDGs. For example, the UN reported that between 2012 and 2017, 80 percent of live births worldwide had assistance from a skilled health professional—an improvement from 62 percent between 2000 and 2005.

While some progress has been made, representatives who attended sustainable development meetings claimed that the SDGs are not being accomplished at the speed, or with the appropriate momentum, needed to meet the 2030 deadline. On some measures of poverty, only slight improvements have been made: The 2018 SDGs Report states that 9.2 percent of the world's workers who live with family members made less than $1.90 per person per day in 2017, representing less than a 1 percent improvement from 2015. Another issue is the recent rise in world hunger. Rates had been steadily declining, but the 2018 SDGs Report stated that over 800 million people were undernourished worldwide in 2016, which is up from 777 million people in 2015.

Another area of the SDGs that lacks progress is gender equality. Multiple news outlets have recently reported that no country is on track to achieve gender equality by 2030 based on the SDG gender index. On a scale of zero to 100, where a score of 100 means equality has been achieved, Denmark was the top performing country out of 129 countries with score slightly under 90. A score of 90 or above means a country is making excellent progress in achieving the goals, and 59 or less is considered poor headway. Countries were scored against SDGs targets that particularly affect women, such as access to safe water or the Internet. The majority of the top 20 countries with a good ranking were European countries, while sub-Saharan Africa had some of the lowest-ranking countries. The overall average score of all countries is a poor score of 65.7.

In fall of 2019, heads of state and government will convene at the United Nations Headquarters in New York to assess the progress in the 17 SDGs. The following year—2020—marks the deadline for 21 of the 169 SDG targets. At this time, UN member states will meet to make a decision to update these targets.

In addition to global efforts to achieve the SDGs, according to the UN, there are ways that an individual can contribute to progress: save on electricity while home by unplugging appliances when not in use; go online and opt in for paperless statements instead of having bills mailed to the house; and report bullying online when seen in a chat room or on social media.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

The Sustainable Development Agenda

17 Goals for People, for Planet

World leaders came together in 2015 and made a historic promise to secure the rights and well-being of everyone on a healthy, thriving planet when they adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) .

The Agenda remains the world’s roadmap for ending poverty, protecting the planet and tackling inequalities. The 17 SDGs, the cornerstone of the Agenda, offer the most practical and effective pathway to tackle the causes of violent conflict, human rights abuses, climate change and environmental degradation and aim to ensure that no one will be left behind. The SDGs reflect an understanding that sustainable development everywhere must integrate economic growth, social well-being and environmental protection.

Keeping the Promise

While a fragile global economy, rising conflicts and the climate emergency have placed the promise of the Goals in peril, we can still turn things around in the remaining seven years. Notably, there has been some SDG success since 2015 with improvements in key areas, including poverty reduction, child mortality, electricity access and the battle against certain diseases.

Countries continue to supercharge efforts to achieve the SDGs. We see this at the annual High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development — the central platform for reviewing progress on the SDGs — where for the last eight years, countries, civil society and businesses have gathered to showcase the bold actions they are taking to achieve the SDGs.

Every four years, the High-Level Political Forum meets under the auspices of the UN General Assembly, known as the SDG Summit . In 2023, the second SDG Summit took place on September 18-19, bringing together Heads of State and Government to catalyze renewed efforts towards accelerating progress on the SDGs. The Summit culminated in the adoption of a political declaration to accelerate action to achieve the 17 goals.

A Decade of Action

The UN Secretary-General called on all sectors of society to mobilize for a decade of action on three levels: global action to secure greater leadership, more resources and smarter solutions for the Sustainable Development Goals; local action embedding the needed transitions in the policies, budgets, institutions and regulatory frameworks of governments, cities and local authorities; and people action , including by youth, civil society, the media, the private sector, unions, academia and other stakeholders, to generate an unstoppable movement pushing for the required transformations.

Numerous civil society leaders and organizations have also called for a “super year of activism” to accelerate progress on the Sustainable Development Goals, urging world leaders to redouble efforts to reach the people furthest behind, support local action and innovation, strengthen data systems and institutions, rebalance the relationship between people and nature, and unlock more financing for sustainable development.

At the core of the 2020-2030 decade is the need for action to tackle growing poverty , empower women and girls , and address the climate emergency .

More people around the world are living better lives compared to just a decade ago. More people have access to better healthcare, decent work, and education than ever before. But inequalities and climate change are threatening to undo the gains. Investment in inclusive and sustainable economies can unleash significant opportunities for shared prosperity. And the political, technological and financial solutions are within reach. But much greater leadership and rapid, unprecedented changes are needed to align these levers of change with sustainable development objectives. #ForPeopleForPlanet

SDG Report 2023

The annual SDG reports provide an overview of the world’s implementation efforts to date, highlighting areas of progress and where more action needs to be taken. They are prepared by the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs, with input from international and regional organizations and the United Nations system of agencies, funds and programmes. Several national statisticians, experts from civil society and academia also contribute to the reports.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is sustainable development?

- Sustainable development has been defined as development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

- Sustainable development calls for concerted efforts towards building an inclusive, sustainable and resilient future for people and planet.

- For sustainable development to be achieved, it is crucial to harmonize three core elements: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection. These elements are interconnected and all are crucial for the well-being of individuals and societies.

- Eradicating poverty in all its forms and dimensions is an indispensable requirement for sustainable development. To this end, there must be promotion of sustainable, inclusive and equitable economic growth, creating greater opportunities for all, reducing inequalities, raising basic standards of living, fostering equitable social development and inclusion, and promoting integrated and sustainable management of natural resources and ecosystems.

How will the Sustainable Development Goals be implemented?

- The Addis Ababa Action Agenda that came out of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development provided concrete policies and actions to support the implementation of the new agenda.

- Implementation and success will rely on countries’ own sustainable development policies, plans and programmes, and will be led by countries. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will be a compass for aligning countries’ plans with their global commitments.

- Nationally owned and country-led sustainable development strategies will require resource mobilization and financing strategies.

- All stakeholders: governments, civil society, the private sector, and others, are expected to contribute to the realisation of the new agenda.

- A revitalized global partnership at the global level is needed to support national efforts. This is recognized in the 2030 Agenda.

- Multi-stakeholder partnerships have been recognized as an important component of strategies that seek to mobilize all stakeholders around the new agenda.

How will the Sustainable Development Goals be monitored?

- At the global level, the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets of the new agenda will be monitored and reviewed using a set of global indicators. The global indicator framework for Sustainable Development Goals was developed by the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators (IAEG-SDGs) and agreed upon at the 48 th session of the United Nations Statistical Commission held in March 2017.

- Governments will also develop their own national indicators to assist in monitoring progress made on the goals and targets.

- Chief statisticians from Member States are working on the identification of the targets with the aim to have 2 indicators for each target. There will be approximately 300 indicators for all the targets. Where the targets cover cross-cutting issues, however, the number of indicators may be reduced.

- The follow-up and review process will be informed by an annual SDG Progress Report to be prepared by the Secretary-General.

- The annual meetings of the High-level Political Forum on sustainable development will play a central role in reviewing progress towards the SDGs at the global level. The means of implementation of the SDGs will be monitored and reviewed as outlined in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda, the outcome document of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, to ensure that financial resources are effectively mobilized to support the new sustainable development agenda.

How much will the implementation of this sustainable development agenda cost?

- To achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, annual investment requirements across all sectors have been estimated at around $5-7 trillion. Current investment levels are far from the scale needed. With global financial assets estimated at over $200 trillion, financing is available, but most of these resources are not being channeled towards sustainable development at the scale and speed necessary to achieve the SDGs and objectives of the Paris Agreement on climate change.

- Interest and investment in the Sustainable Development Goals are growing and investment in the Goals makes economic sense. Achieving the SDGs could open up US$12 trillion of market opportunities and create 380 million new jobs by 2030.

- The Global Investors for Sustainable Development Alliance , a UN-supported coalition of 30 business leaders announced in October 2019, works to provide decisive leadership in mobilizing resources for sustainable development and identifying incentives for long-term sustainable investments.Net Official Development Assistance totaled $149 billion in 2018, down by 2.7% in real terms from 2017.

How does climate change relate to sustainable development?

- Climate change is already impacting public health, food and water security, migration, peace and security. Climate change, left unchecked, will roll back the development gains we have made over the last decades and will make further gains impossible.

- Investments in sustainable development will help address climate change by reducing greenhouse gas emissions and building climate resilience.

- Conversely, action on climate change will drive sustainable development.

- Tackling climate change and fostering sustainable development are two mutually reinforcing sides of the same coin; sustainable development cannot be achieved without climate action. Conversely, many of the SDGs are addressing the core drivers of climate change.

Are the Sustainable Development Goals legally binding?

- No. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are not legally binding.

- Nevertheless, countries are expected to take ownership and establish a national framework for achieving the 17 Goals.

- Implementation and success will rely on countries’ own sustainable development policies, plans and programmes.

- Countries have the primary responsibility for follow-up and review, at the national, regional and global levels, with regard to the progress made in implementing the Goals and targets by 2030.

- Actions at the national level to monitor progress will require quality, accessible and timely data collection and regional follow-up and review.

How are the Sustainable Development Goals different from the MDGs?

- The 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with 169 targets are broader in scope and go further than the MDGs by addressing the root causes of poverty and the universal need for development that works for all people. The goals cover the three dimensions of sustainable development: economic growth, social inclusion and environmental protection.

- Building on the success and momentum of the MDGs, the new goals cover more ground, with ambitions to address inequalities, economic growth, decent jobs, cities and human settlements, industrialization, oceans, ecosystems, energy, climate change, sustainable consumption and production, peace and justice.

- The new Goals are universal and apply to all countries, whereas the MDGs were intended for action in developing countries only.

- A core feature of the SDGs is their strong focus on means of implementation—the mobilization of financial resources—capacity-building and technology, as well as data and institutions.

- The new Goals recognize that tackling climate change is essential for sustainable development and poverty eradication. SDG 13 aims to promote urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

- Get involved

THE SDGS IN ACTION.

What are the sustainable development goals.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), also known as the Global Goals, were adopted by the United Nations in 2015 as a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet, and ensure that by 2030 all people enjoy peace and prosperity.

The 17 SDGs are integrated—they recognize that action in one area will affect outcomes in others, and that development must balance social, economic and environmental sustainability.

Countries have committed to prioritize progress for those who're furthest behind. The SDGs are designed to end poverty, hunger, AIDS, and discrimination against women and girls.

The creativity, knowhow, technology and financial resources from all of society is necessary to achieve the SDGs in every context.

Eradicating poverty in all its forms remains one of the greatest challenges facing humanity. While the number of people living in extreme poverty dropped by more than half between 1990 and 2015, too many are still struggling for the most basic human needs.

As of 2015, about 736 million people still lived on less than US$1.90 a day; many lack food, clean drinking water and sanitation. Rapid growth in countries such as China and India has lifted millions out of poverty, but progress has been uneven. Women are more likely to be poor than men because they have less paid work, education, and own less property.

Progress has also been limited in other regions, such as South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, which account for 80 percent of those living in extreme poverty. New threats brought on by climate change, conflict and food insecurity, mean even more work is needed to bring people out of poverty.

The SDGs are a bold commitment to finish what we started, and end poverty in all forms and dimensions by 2030. This involves targeting the most vulnerable, increasing basic resources and services, and supporting communities affected by conflict and climate-related disasters.

736 million people still live in extreme poverty.

10 percent of the world’s population live in extreme poverty, down from 36 percent in 1990.

Some 1.3 billion people live in multidimensional poverty.

Half of all people living in poverty are under 18.

One person in every 10 is extremely poor.

Goal targets

- By 2030, reduce at least by half the proportion of men, women and children of all ages living in poverty in all its dimensions according to national definitions

- Implement nationally appropriate social protection systems and measures for all, including floors, and by 2030 achieve substantial coverage of the poor and the vulnerable

- By 2030, ensure that all men and women, in particular the poor and the vulnerable, have equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to basic services, ownership and control over land and other forms of property, inheritance, natural resources, appropriate new technology and financial services, including microfinance

- By 2030, build the resilience of the poor and those in vulnerable situations and reduce their exposure and vulnerability to climate-related extreme events and other economic, social and environmental shocks and disasters

- Ensure significant mobilization of resources from a variety of sources, including through enhanced development cooperation, in order to provide adequate and predictable means for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, to implement programmes and policies to end poverty in all its dimensions

- Create sound policy frameworks at the national, regional and international levels, based on pro-poor and gender-sensitive development strategies, to support accelerated investment in poverty eradication actions

SDGs in Action

Building a new, secure climate...

Publications.

Accelerating the Green Transit...

Localizing Multidimensional Po...

Mapping Essential Life Support...

One year into war, much remain...

Preparing Cities for Climate D...

Zero hunger.

Zero Hunger

The number of undernourished people has dropped by almost half in the past two decades because of rapid economic growth and increased agricultural productivity. Many developing countries that used to suffer from famine and hunger can now meet their nutritional needs. Central and East Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean have all made huge progress in eradicating extreme hunger.

Unfortunately, extreme hunger and malnutrition remain a huge barrier to development in many countries. There are 821 million people estimated to be chronically undernourished as of 2017, often as a direct consequence of environmental degradation, drought and biodiversity loss. Over 90 million children under five are dangerously underweight. Undernourishment and severe food insecurity appear to be increasing in almost all regions of Africa, as well as in South America.

The SDGs aim to end all forms of hunger and malnutrition by 2030, making sure all people–especially children–have sufficient and nutritious food all year. This involves promoting sustainable agricultural, supporting small-scale farmers and equal access to land, technology and markets. It also requires international cooperation to ensure investment in infrastructure and technology to improve agricultural productivity.

The number of undernourished people reached 821 million in 2017.

In 2017 Asia accounted for nearly two thirds, 63 percent, of the world’s hungry.

Nearly 151 million children under five, 22 percent, were still stunted in 2017.

More than 1 in 8 adults is obese.

1 in 3 women of reproductive age is anemic.

26 percent of workers are employed in agriculture.

- By 2030, end all forms of malnutrition, including achieving, by 2025, the internationally agreed targets on stunting and wasting in children under 5 years of age, and address the nutritional needs of adolescent girls, pregnant and lactating women and older persons

- By 2030, double the agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment

- By 2030, ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices that increase productivity and production, that help maintain ecosystems, that strengthen capacity for adaptation to climate change, extreme weather, drought, flooding and other disasters and that progressively improve land and soil quality

- By 2020, maintain the genetic diversity of seeds, cultivated plants and farmed and domesticated animals and their related wild species, including through soundly managed and diversified seed and plant banks at the national, regional and international levels, and promote access to and fair and equitable sharing of benefits arising from the utilization of genetic resources and associated traditional knowledge, as internationally agreed

- Increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation, in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks in order to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular least developed countries

- Correct and prevent trade restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets, including through the parallel elimination of all forms of agricultural export subsidies and all export measures with equivalent effect, in accordance with the mandate of the Doha Development Round

- Adopt measures to ensure the proper functioning of food commodity markets and their derivatives and facilitate timely access to market information, including on food reserves, in order to help limit extreme food price volatility.

UNDP at the 4th International ...

UNDP at the UN ECOSOC Youth Fo...

"We felt very welcome and acce...

Recovery and hope in Myanmar's...

Good health and well-being.

We have made great progress against several leading causes of death and disease. Life expectancy has increased dramatically; infant and maternal mortality rates have declined, we’ve turned the tide on HIV and malaria deaths have halved.

Good health is essential to sustainable development and the 2030 Agenda reflects the complexity and interconnectedness of the two. It takes into account widening economic and social inequalities, rapid urbanization, threats to the climate and the environment, the continuing burden of HIV and other infectious diseases, and emerging challenges such as noncommunicable diseases. Universal health coverage will be integral to achieving SDG 3, ending poverty and reducing inequalities. Emerging global health priorities not explicitly included in the SDGs, including antimicrobial resistance, also demand action.

But the world is off-track to achieve the health-related SDGs. Progress has been uneven, both between and within countries. There’s a 31-year gap between the countries with the shortest and longest life expectancies. And while some countries have made impressive gains, national averages hide that many are being left behind. Multisectoral, rights-based and gender-sensitive approaches are essential to address inequalities and to build good health for all.

At least 400 million people have no basic healthcare, and 40 percent lack social protection.

More than 1.6 billion people live in fragile settings where protracted crises, combined with weak national capacity to deliver basic health services, present a significant challenge to global health.

By the end of 2017, 21.7 million people living with HIV were receiving antiretroviral therapy. Yet more than 15 million people are still waiting for treatment.

Every 2 seconds someone aged 30 to 70 years dies prematurely from noncommunicable diseases - cardiovascular disease, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes or cancer.

7 million people die every year from exposure to fine particles in polluted air.

More than one of every three women have experienced either physical or sexual violence at some point in their life resulting in both short- and long-term consequences for their physical, mental, and sexual and reproductive health.

- By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births

- By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births

- By 2030, end the epidemics of AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and neglected tropical diseases and combat hepatitis, water-borne diseases and other communicable diseases

- By 2030, reduce by one third premature mortality from non-communicable diseases through prevention and treatment and promote mental health and well-being

- Strengthen the prevention and treatment of substance abuse, including narcotic drug abuse and harmful use of alcohol

- By 2020, halve the number of global deaths and injuries from road traffic accidents

- By 2030, ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, including for family planning, information and education, and the integration of reproductive health into national strategies and programmes

- Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all

- By 2030, substantially reduce the number of deaths and illnesses from hazardous chemicals and air, water and soil pollution and contamination

- Strengthen the implementation of the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control in all countries, as appropriate

- Support the research and development of vaccines and medicines for the communicable and noncommunicable diseases that primarily affect developing countries, provide access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines, in accordance with the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health, which affirms the right of developing countries to use to the full the provisions in the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights regarding flexibilities to protect public health, and, in particular, provide access to medicines for all

- Substantially increase health financing and the recruitment, development, training and retention of the health workforce in developing countries, especially in least developed countries and small island developing States

- Strengthen the capacity of all countries, in particular developing countries, for early warning, risk reduction and management of national and global health risks

HIV and Health Annual Report 2...

Bridging Gender Gaps with a Su...

How Do Investments in Human Ca...

The right environment for heal...

Quality education.

Since 2000, there has been enormous progress in achieving the target of universal primary education. The total enrollment rate in developing regions reached 91 percent in 2015, and the worldwide number of children out of school has dropped by almost half. There has also been a dramatic increase in literacy rates, and many more girls are in school than ever before. These are all remarkable successes.

Progress has also been tough in some developing regions due to high levels of poverty, armed conflicts and other emergencies. In Western Asia and North Africa, ongoing armed conflict has seen an increase in the number of children out of school. This is a worrying trend. While Sub-Saharan Africa made the greatest progress in primary school enrollment among all developing regions – from 52 percent in 1990, up to 78 percent in 2012 – large disparities still remain. Children from the poorest households are up to four times more likely to be out of school than those of the richest households. Disparities between rural and urban areas also remain high.

Achieving inclusive and quality education for all reaffirms the belief that education is one of the most powerful and proven vehicles for sustainable development. This goal ensures that all girls and boys complete free primary and secondary schooling by 2030. It also aims to provide equal access to affordable vocational training, to eliminate gender and wealth disparities, and achieve universal access to a quality higher education.

Enrollment in primary education in developing countries has reached 91 percent.

Still, 57 million primary-aged children remain out of school, more than half of them in sub-Saharan Africa.

In developing countries, one in four girls is not in school.

About half of all out-of-school children of primary school age live in conflict-affected areas.

103 million youth worldwide lack basic literacy skills, and more than 60 percent of them are women.

6 out of 10 children and adolescents are not achieving a minimum level of proficiency in reading and math.

- By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and Goal-4 effective learning outcomes

- By 2030, ensure that all girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development, care and preprimary education so that they are ready for primary education

- By 2030, ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university

- By 2030, substantially increase the number of youth and adults who have relevant skills, including technical and vocational skills, for employment, decent jobs and entrepreneurship

- By 2030, eliminate gender disparities in education and ensure equal access to all levels of education and vocational training for the vulnerable, including persons with disabilities, indigenous peoples and children in vulnerable situations

- By 2030, ensure that all youth and a substantial proportion of adults, both men and women, achieve literacy and numeracy

- By 2030, ensure that all learners acquire the knowledge and skills needed to promote sustainable development, including, among others, through education for sustainable development and sustainable lifestyles, human rights, gender equality, promotion of a culture of peace and non-violence, global citizenship and appreciation of cultural diversity and of culture’s contribution to sustainable development

- Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, nonviolent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all

- By 2020, substantially expand globally the number of scholarships available to developing countries, in particular least developed countries, small island developing States and African countries, for enrolment in higher education, including vocational training and information and communications technology, technical, engineering and scientific programmes, in developed countries and other developing countries

- By 2030, substantially increase the supply of qualified teachers, including through international cooperation for teacher training in developing countries, especially least developed countries and small island developing states

Using technology to support ne...

The future of education

A brighter future: Lillian

Three reasons climate change e...

Gender equality.

Gender Equality

Ending all discrimination against women and girls is not only a basic human right, it’s crucial for sustainable future; it’s proven that empowering women and girls helps economic growth and development.

UNDP has made gender equality central to its work and we’ve seen remarkable progress in the past 20 years. There are more girls in school now compared to 15 years ago, and most regions have reached gender parity in primary education.

But although there are more women than ever in the labour market, there are still large inequalities in some regions, with women systematically denied the same work rights as men. Sexual violence and exploitation, the unequal division of unpaid care and domestic work, and discrimination in public office all remain huge barriers. Climate change and disasters continue to have a disproportionate effect on women and children, as do conflict and migration.

It is vital to give women equal rights land and property, sexual and reproductive health, and to technology and the internet. Today there are more women in public office than ever before, but encouraging more women leaders will help achieve greater gender equality.

Women earn only 77 cents for every dollar that men get for the same work.

35 percent of women have experienced physical and/or sexual violence.

Women represent just 13 percent of agricultural landholders.

Almost 750 million women and girls alive today were married before their 18th birthday.

Two thirds of developing countries have achieved gender parity in primary education.

Only 24 percent of national parliamentarians were women as of November 2018, a small increase from 11.3 percent in 1995.

- End all forms of discrimination against all women and girls everywhere

- Eliminate all forms of violence against all women and girls in the public and private spheres, including trafficking and sexual and other types of exploitation

- Eliminate all harmful practices, such as child, early and forced marriage and female genital mutilation

- Recognize and value unpaid care and domestic work through the provision of public services, infrastructure and social protection policies and the promotion of shared responsibility within the household and the family as nationally appropriate

- Ensure women’s full and effective participation and equal opportunities for leadership at all levels of decisionmaking in political, economic and public life

- Ensure universal access to sexual and reproductive health and reproductive rights as agreed in accordance with the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development and the Beijing Platform for Action and the outcome documents of their review conferences

- Undertake reforms to give women equal rights to economic resources, as well as access to ownership and control over land and other forms of property, financial services, inheritance and natural resources, in accordance with national laws

- Enhance the use of enabling technology, in particular information and communications technology, to promote the empowerment of women

- Adopt and strengthen sound policies and enforceable legislation for the promotion of gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls at all levels

SDG Push through Social Protec...

Climate governance, adaptation...

"The work might be hard, but I...

Clean water and sanitation.

Water scarcity affects more than 40 percent of people, an alarming figure that is projected to rise as temperatures do. Although 2.1 billion people have improved water sanitation since 1990, dwindling drinking water supplies are affecting every continent.

More and more countries are experiencing water stress, and increasing drought and desertification is already worsening these trends. By 2050, it is projected that at least one in four people will suffer recurring water shortages.

Safe and affordable drinking water for all by 2030 requires we invest in adequate infrastructure, provide sanitation facilities, and encourage hygiene. Protecting and restoring water-related ecosystems is essential.

Ensuring universal safe and affordable drinking water involves reaching over 800 million people who lack basic services and improving accessibility and safety of services for over two billion.

In 2015, 4.5 billion people lacked safely managed sanitation services (with adequately disposed or treated excreta) and 2.3 billion lacked even basic sanitation.

71 percent of the global population, 5.2 billion people, had safely-managed drinking water in 2015, but 844 million people still lacked even basic drinking water.

39 percent of the global population, 2.9 billion people, had safe sanitation in 2015, but 2.3 billion people still lacked basic sanitation. 892 million people practiced open defecation.

80 percent of wastewater goes into waterways without adequate treatment.

Water stress affects more than 2 billion people, with this figure projected to increase.

80 percent of countries have laid the foundations for integrated water resources management.

The world has lost 70 percent of its natural wetlands over the last century.

- By 2030, achieve universal and equitable access to safe and affordable drinking water for all

- By 2030, achieve access to adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and end open defecation, paying special attention to the needs of women and girls and those in vulnerable situations

- By 2030, improve water quality by reducing pollution, eliminating dumping and minimizing release of hazardous chemicals and materials, halving the proportion of untreated wastewater and substantially increasing recycling and safe reuse globally

- By 2030, substantially increase water-use efficiency across all sectors and ensure sustainable withdrawals and supply of freshwater to address water scarcity and substantially reduce the number of people suffering from water scarcity

- By 2030, implement integrated water resources management at all levels, including through transboundary cooperation as appropriate

- By 2020, protect and restore water-related ecosystems, including mountains, forests, wetlands, rivers, aquifers and lakes

- By 2030, expand international cooperation and capacity-building support to developing countries in water- and sanitation-related activities and programmes, including water harvesting, desalination, water efficiency, wastewater treatment, recycling and reuse technologies

- Support and strengthen the participation of local communities in improving water and sanitation management

The challenges facing Sudan

Navigating the crossroads of c...

Preserving the laboratory of e...

Affordable and clean energy.

Between 2000 and 2018, the number of people with electricity increased from 78 to 90 percent, and the numbers without electricity dipped to 789 million.

Yet as the population continues to grow, so will the demand for cheap energy, and an economy reliant on fossil fuels is creating drastic changes to our climate.

Investing in solar, wind and thermal power, improving energy productivity, and ensuring energy for all is vital if we are to achieve SDG 7 by 2030.

Expanding infrastructure and upgrading technology to provide clean and more efficient energy in all countries will encourage growth and help the environment.

One out of 10 people still lacks electricity, and most live in rural areas of the developing world. More than half are in sub-Saharan Africa.

Energy is by far the main contributor to climate change. It accounts for 73 percent of human-caused greenhouse gases.

Energy efficiency is key; the right efficiency policies could enable the world to achieve more than 40 percent of the emissions cuts needed to reach its climate goals without new technology.

Almost a third of the world’s population—2.8 billion—rely on polluting and unhealthy fuels for cooking.

As of 2017, 17.5 percent of power was generated through renewable sources.

The renewable energy sector employed a record 11.5 million people in 2019. The changes needed in energy production and uses to achieve the Paris Agreement target of limiting the rise in temperature to below 2C can create 18 million jobs.

- By 2030, ensure universal access to affordable, reliable and modern energy services

- By 2030, increase substantially the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix

- By 2030, double the global rate of improvement in energy efficiency

- By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology, including renewable energy, energy efficiency and advanced and cleaner fossil-fuel technology, and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology

- By 2030, expand infrastructure and upgrade technology for supplying modern and sustainable energy services for all in developing countries, in particular least developed countries, small island developing States, and land-locked developing coun

The big switch

Targeted and Inclusive Approac...

Breaking the cycle of poverty ...

Mainstreaming Financial Aggreg...

Decent work and economic growth.

Over the past 25 years the number of workers living in extreme poverty has declined dramatically, despite the lasting impact of the 2008 economic crisis and global recession. In developing countries, the middle class now makes up more than 34 percent of total employment – a number that has almost tripled between 1991 and 2015.

However, as the global economy continues to recover we are seeing slower growth, widening inequalities, and not enough jobs to keep up with a growing labour force. According to the International Labour Organization, more than 204 million people were unemployed in 2015.

The SDGs promote sustained economic growth, higher levels of productivity and technological innovation. Encouraging entrepreneurship and job creation are key to this, as are effective measures to eradicate forced labour, slavery and human trafficking. With these targets in mind, the goal is to achieve full and productive employment, and decent work, for all women and men by 2030.

An estimated 172 million people worldwide were without work in 2018 - an unemployment rate of 5 percent.

As a result of an expanding labour force, the number of unemployed is projected to increase by 1 million every year and reach 174 million by 2020.

Some 700 million workers lived in extreme or moderate poverty in 2018, with less than US$3.20 per day.

Women’s participation in the labour force stood at 48 per cent in 2018, compared with 75 percent for men. Around 3 in 5 of the 3.5 billion people in the labour force in 2018 were men.

Overall, 2 billion workers were in informal employment in 2016, accounting for 61 per cent of the world’s workforce.

Many more women than men are underutilized in the labour force—85 million compared to 55 million.

- Sustain per capita economic growth in accordance with national circumstances and, in particular, at least 7 per cent gross domestic product growth per annum in the least developed countries

- Achieve higher levels of economic productivity through diversification, technological upgrading and innovation, including through a focus on high-value added and labour-intensive sectors

- Promote development-oriented policies that support productive activities, decent job creation, entrepreneurship, creativity and innovation, and encourage the formalization and growth of micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises, including through access to financial services

- Improve progressively, through 2030, global resource efficiency in consumption and production and endeavour to decouple economic growth from environmental degradation, in accordance with the 10-year framework of programmes on sustainable consumption and production, with developed countries taking the lead

- By 2030, achieve full and productive employment and decent work for all women and men, including for young people and persons with disabilities, and equal pay for work of equal value

- By 2020, substantially reduce the proportion of youth not in employment, education or training

- Take immediate and effective measures to eradicate forced labour, end modern slavery and human trafficking and secure the prohibition and elimination of the worst forms of child labour, including recruitment and use of child soldiers, and by 2025 end child labour in all its forms

- Protect labour rights and promote safe and secure working environments for all workers, including migrant workers, in particular women migrants, and those in precarious employment

- By 2030, devise and implement policies to promote sustainable tourism that creates jobs and promotes local culture and products

- Strengthen the capacity of domestic financial institutions to encourage and expand access to banking, insurance and financial services for all

- Increase Aid for Trade support for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, including through the Enhanced Integrated Framework for Trade-Related Technical Assistance to Least Developed Countries

- By 2020, develop and operationalize a global strategy for youth employment and implement the Global Jobs Pact of the International Labour Organization

Industry, innovation and infrastructure

Investment in infrastructure and innovation are crucial drivers of economic growth and development. With over half the world population now living in cities, mass transport and renewable energy are becoming ever more important, as are the growth of new industries and information and communication technologies.

Technological progress is also key to finding lasting solutions to both economic and environmental challenges, such as providing new jobs and promoting energy efficiency. Promoting sustainable industries, and investing in scientific research and innovation, are all important ways to facilitate sustainable development.

More than 4 billion people still do not have access to the Internet, and 90 percent are from the developing world. Bridging this digital divide is crucial to ensure equal access to information and knowledge, as well as foster innovation and entrepreneurship.

Worldwide, 2.3 billion people lack access to basic sanitation.

In some low-income African countries, infrastructure constraints cut businesses’ productivity by around 40 percent.

2.6 billion people in developing countries do not have access to constant electricity.

More than 4 billion people still do not have access to the Internet; 90 percent of them are in the developing world.

The renewable energy sectors currently employ more than 2.3 million people; the number could reach 20 million by 2030.

In developing countries, barely 30 percent of agricultural products undergo industrial processing, compared to 98 percent high-income countries.

- Develop quality, reliable, sustainable and resilient infrastructure, including regional and transborder infrastructure, to support economic development and human well-being, with a focus on affordable and equitable access for all

- Promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and, by 2030, significantly raise industry’s share of employment and gross domestic product, in line with national circumstances, and double its share in least developed countries

- Increase the access of small-scale industrial and other enterprises, in particular in developing countries, to financial services, including affordable credit, and their integration into value chains and markets

- By 2030, upgrade infrastructure and retrofit industries to make them sustainable, with increased resource-use efficiency and greater adoption of clean and environmentally sound technologies and industrial processes, with all countries taking action in accordance with their respective capabilities

- Enhance scientific research, upgrade the technological capabilities of industrial sectors in all countries, in particular developing countries, including, by 2030, encouraging innovation and substantially increasing the number of research and development workers per 1 million people and public and private research and development spending

- Facilitate sustainable and resilient infrastructure development in developing countries through enhanced financial, technological and technical support to African countries, least developed countries, landlocked developing countries and small island developing States 18

- Support domestic technology development, research and innovation in developing countries, including by ensuring a conducive policy environment for, inter alia, industrial diversification and value addition to commodities

- Significantly increase access to information and communications technology and strive to provide universal and affordable access to the Internet in least developed countries by 2020

How Digital is Transforming th...

Popping the bottle

Small Island Digital States: H...

Harnessing technology for posi...

Reduced inequalities.

Income inequality is on the rise—the richest 10 percent have up to 40 percent of global income whereas the poorest 10 percent earn only between 2 to 7 percent. If we take into account population growth inequality in developing countries, inequality has increased by 11 percent.

Income inequality has increased in nearly everywhere in recent decades, but at different speeds. It’s lowest in Europe and highest in the Middle East.

These widening disparities require sound policies to empower lower income earners, and promote economic inclusion of all regardless of sex, race or ethnicity.

Income inequality requires global solutions. This involves improving the regulation and monitoring of financial markets and institutions, encouraging development assistance and foreign direct investment to regions where the need is greatest. Facilitating the safe migration and mobility of people is also key to bridging the widening divide.

In 2016, 22 percent of global income was received by the top 1 percent compared with 10 percent of income for the bottom 50 percent.

In 1980, the top one percent had 16 percent of global income. The bottom 50 percent had 8 percent of income.

Economic inequality is largely driven by the unequal ownership of capital. Since 1980, very large transfers of public to private wealth occurred in nearly all countries. The global wealth share of the top 1 percent was 33 percent in 2016.

Under "business as usual", the top 1 percent global wealth will reach 39 percent by 2050.

Women spend, on average, twice as much time on unpaid housework as men.

Women have as much access to financial services as men in just 60 percent of the countries assessed and to land ownership in just 42 percent of the countries assessed.

- By 2030, progressively achieve and sustain income growth of the bottom 40 per cent of the population at a rate higher than the national average

- By 2030, empower and promote the social, economic and political inclusion of all, irrespective of age, sex, disability, race, ethnicity, origin, religion or economic or other status

- Ensure equal opportunity and reduce inequalities of outcome, including by eliminating discriminatory laws, policies and practices and promoting appropriate legislation, policies and action in this regard

- Adopt policies, especially fiscal, wage and social protection policies, and progressively achieve greater equality

- Improve the regulation and monitoring of global financial markets and institutions and strengthen the implementation of such regulations

- Ensure enhanced representation and voice for developing countries in decision-making in global international economic and financial institutions in order to deliver more effective, credible, accountable and legitimate institutions

- Facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration and mobility of people, including through the implementation of planned and well-managed migration policies

- Implement the principle of special and differential treatment for developing countries, in particular least developed countries, in accordance with World Trade Organization agreements

- Encourage official development assistance and financial flows, including foreign direct investment, to States where the need is greatest, in particular least developed countries, African countries, small island developing States and landlocked developing countries, in accordance with their national plans and programmes

- By 2030, reduce to less than 3 per cent the transaction costs of migrant remittances and eliminate remittance corridors with costs higher than 5 per cent

Sustainable cities and communities

More than half of us live in cities. By 2050, two-thirds of all humanity—6.5 billion people—will be urban. Sustainable development cannot be achieved without significantly transforming the way we build and manage our urban spaces.

The rapid growth of cities—a result of rising populations and increasing migration—has led to a boom in mega-cities, especially in the developing world, and slums are becoming a more significant feature of urban life.

Making cities sustainable means creating career and business opportunities, safe and affordable housing, and building resilient societies and economies. It involves investment in public transport, creating green public spaces, and improving urban planning and management in participatory and inclusive ways.

In 2018, 4.2 billion people, 55 percent of the world’s population, lived in cities. By 2050, the urban population is expected to reach 6.5 billion.

Cities occupy just 3 percent of the Earth’s land but account for 60 to 80 percent of energy consumption and at least 70 percent of carbon emissions.

828 million people are estimated to live in slums, and the number is rising.

In 1990, there were 10 cities with 10 million people or more; by 2014, the number of mega-cities rose to 28, and was expected to reach 33 by 2018. In the future, 9 out of 10 mega-cities will be in the developing world.

In the coming decades, 90 percent of urban expansion will be in the developing world.

The economic role of cities is significant. They generate about 80 percent of the global GDP.

- By 2030, ensure access for all to adequate, safe and affordable housing and basic services and upgrade slums

- By 2030, provide access to safe, affordable, accessible and sustainable transport systems for all, improving road safety, notably by expanding public transport, with special attention to the needs of those in vulnerable situations, women, children, persons with disabilities and older persons

- By 2030, enhance inclusive and sustainable urbanization and capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning and management in all countries

- Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage