Ancient Egyptian Literature You Should Know About

Ancient Egyptian literature, which is one of the world’s earliest, is an an important component of Ancient Egypt ‘s great civilization, and a representation of the peoples’ life, culture, and beliefs. Here are some picks of literary fables that you should be reading about.

The legend of isis and osiris.

This is one of the best known myths in ancient Egypt. It concerns the murder of God Osiris by his brother, Set aka Seth, in order for him to take over the throne. Isis, Osiris’s wife, later collects her husband’s body and revives it it order to have a son with him. The rest of the story focuses on how Horus , Isis and Osiris’s son, becomes his uncle’s competitor to the throne and how he takes it back. The story is one of the most important in ancient Egypt for its religious symbolism, and”strong sense of family loyalty and devotion”, as J. Gwyn Griffiths , Egyptologist, says. For its importance, some parts of the story appear on ancient Egyptian texts such as short stories, magical spells, and funeral texts.

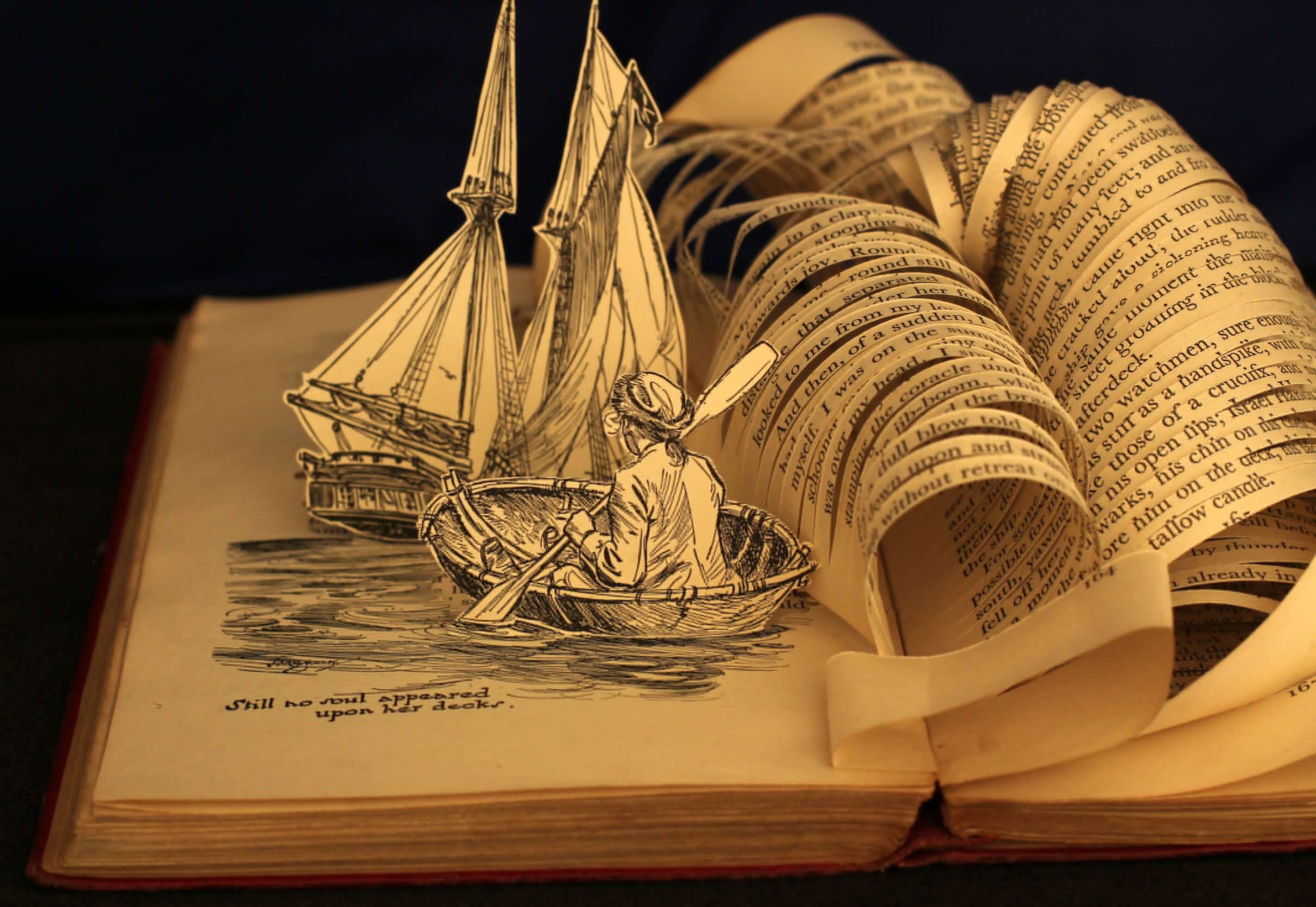

The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor

Great hymen to the aten.

In ancient Egypt, long poems, or hymens, were written to the God of Aten, and were attributed to King Akhenaten . This king changed the traditional forms of Egyptian religions, in which they worshipped many Gods, and replaced it with Atenism. This hymen shows the brilliance and artistry of the era. The hymen was said to be “one of the most significant and splendid pieces of poetry to survive from the pre-Homeric world” according to English Egyptologist, Toby Wilkinson. It was also turned to a musical by American composer, Philip Glass, in his opera Akhnaten.

Become a Culture Tripper!

Sign up to our newsletter to save up to 500$ on our unique trips..

See privacy policy .

The Maxims of Ptahhotep

Maxims of Ptahhotep, also called the Instructions of Ptahhotep, is a collection of teaching advice about social virtues, kindness, modesty, and justice. The literary work remains currently in many papyrus texts, including two manuscripts housed at the British Museum, as well as the Prisse Papyrus that goes back to the Middle Kingdom, housed at Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

The Westcar Papyrus

This is one of Ancient Egypt’s texts that contains five stories narrated at the royal court of King Khufu (Cheops) by his sons about priests and magicians and their miracles, and is also known as “King Cheops and Magocians.” The papyrus is now located at the Egyptian Museum of Berlin and it is exhibited there under low-light conditions.

KEEN TO EXPLORE THE WORLD?

Connect with like-minded people on our premium trips curated by local insiders and with care for the world

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

Guides & Tips

Reviving history: a journey through historic landmarks in 2024.

The Best Private Trips to Book For Your History Class

The Best Trips for Exploring the World's Most Famous Rivers

The Oldest Temples in the World That You Can Visit With Culture Trip

The Oldest Religious Sites You Can Visit With Culture Trip

The Ultimate Guide to Holidays in Egypt

Top Tips for Travelling in Egypt

How much does a trip to egypt cost.

The Best Places to Travel in January 2024

The Best Places to Travel to in October

A Solo Traveller's Guide to Egypt

See & Do

The best ancient egyptian temples to visit.

- Post ID: 1081922

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

47 Orality and literacy in ancient Egypt

Jacqueline E. Jay is Associate Professor of Egyptology, Department of History, Philosophy and Religious Studies, Eastern Kentucky University

- Published: 15 December 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Ancient Egypt has long been recognized for its importance as one of the world’s earliest ‘literate’ societies. However, it is only relatively recently that modern scholarship has begun to emphasize pharaonic Egypt’s ties to its pre-literate, prehistoric past and the many ways in which oral modes of behaviour continued to influence Egyptian society throughout the Pharaonic period and beyond. The educational process through which individuals were trained to read and write was itself heavily dependent upon oral recitation. Ritual and literary texts were intended for oral performance, and legal and business documents served to record an oral act. Over time, however, we do find a movement towards the independent use of such documentary texts as binding in their own right. The Ptolemaic and Roman periods witnessed particularly significant change, with writing being mobilized in new ways to support the foreign government’s control of a conquered population.

Introduction

The notion of ‘orality and literacy’ first gained prominence with the publication of Walter J. Ong’s 1982 monograph, Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word . The first part of this book establishes the critical differences between fully oral, pre-literate societies and literate ones, identifying a number of key ‘psychodynamics of orality’. In the absence of writing, oral cultures use a variety of other strategies to enable the long-term preservation of knowledge (e.g., formulaic language, repetition, paratactic grammar). They also place a greater focus on the present moment and emphasize practical application over the abstract. The book’s second major claim is that ‘writing restructures consciousness’ (the title of chapter 4 ). The artificial and autonomous nature of a text produced in written form alienates it from the realm of oral speech (which is, in contrast, fully natural to humans), heightening consciousness and thereby making possible abstract and analytic thought. 1 There are certainly aspects of Ong’s work that can be (and have been) called into question, particularly his characterization of the development of abstract thought as a Greek innovation tied to the development of the alphabet. 2 On the whole, however, the far-reaching influence of his work cannot be overstated. Its implications for our understanding of the complex relationship between orality and literacy in ancient Egypt are profound.

To date, two of the most comprehensive Egyptological studies exploring these issues are survey articles by Donald Redford and John Baines. 3 Redford emphasizes the divide between orality and literacy, describing them as ‘“two solitudes”, each proceeding according to its own light, but impinging from time to time upon the other in an interaction at once hostile yet accommodating’. 4 He goes so far as to argue that the scribal tradition ‘set about actively to denigrate oral composition and transmission’. Certain texts clearly do give primacy to the written word. For example, there was a common trope by which kings justified religious rituals and theological texts by claiming reference to written works of the ancient past. In the tomb of Kheruef, Amenhotep III’s sed -festival (royal jubilee) is described as something that his majesty did ‘on the model of ancient writings. Generations of people from the time of the forefathers, they have not made (such) celebrations of the jubilee’. 5 Similarly, King Shabaqo ( c .716–702 bc ) of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty claimed that the Memphite Theology was re-copied after ‘his majesty found it to be what the ancestors had done, which was worm-eaten’. 6 In general, the elite’s emphasis on its ability to produce and call upon written sources probably did help to legitimize its domination over an illiterate majority. As discussed in more detail below, however, it is also critical to acknowledge the existence of situations in which unwritten personal memory and the oral tradition were viewed as authoritative.

In contrast to Redford, Baines stresses the complex interaction between orality and literacy in ancient Egypt. 7 Even the most autonomous written tradition occurs (and must be understood) within a ‘living oral context’. 8 Indeed, following Ong’s schema, ancient Egypt represents a literate culture ‘not far removed from primary orality’. 9 As a result, the impact of surviving orality is evident in a wide range of practices (even elite ‘high culture’ ones). Written letters are given the form of an oral direct speech made by the sender to the recipient, with letter-writing formulae regularly invoking the verb ḏd (‘to say’). 10 It was not until the third century ad that the verb ‘to say’ was replaced by the verb ‘to write’. 11 Similarly oral terminology exists in the religious sphere. The ritual formula ḏd mdw (‘saying words’), the prt ḫrw invocation formula (a ‘sending forth of the voice’), and the common funerary ‘appeal to the living’ are all key examples. 12 Longer religious texts possess elements that suggest a particularly complex blend of written and oral, visual and performative. The underworld books of the New Kingdom ( c .1550–1069 bc ), for example, mix pictorial illustration and written caption. Papyrus copies of these texts (all very large) may have been used for purposes of ritual display and consultation. Both text and image were also recorded on the walls of the royal tombs for eternal efficacy. At the same time, the nature of the underworld books as ‘secret knowledge’ suggests that their use was augmented with oral elements known only by the initiated. 13 By such means the Egyptians were able to make use of the full range of communicative possibilities available to them: oral, written, and pictorial.

While the scribe may at times seem to denigrate oral modes of communication, it must be emphasized that the methods of his own scribal education were heavily influenced by orality. Indeed, the nature of education in ancient Egypt must have been a critical factor contributing to the surviving influence of orality at even the highest levels of Egyptian society. The most basic kinds of educational texts (lists of specific words and verb forms) exist only from the New Kingdom onwards, surviving in relatively high numbers from the Ptolemaic and Roman periods ( c .332 bc – ad 395). 14 However, given that we have no educational texts at all dating earlier than the Middle Kingdom ( c .2055–1650 bc ), it seems reasonable to assume that beginning primers in some form had existed since the invention of writing. Beginning students seem to have used such material in a group context, as indicated by advice from the Instruction for Merykara : ‘Do not execute a man of whose abilities you are aware, one with whom you used to chant the writings.’ 15 This description suggests a schoolroom in which students copied out word lists and simple texts element by element with a teacher leading the group in the oral recitation of each word as it was written. The most advanced students worked more independently, producing copies of longer and more complex texts. 16 Given that the phenomenon of ‘silent reading’ was less emphasized in ancient Egypt, they too would have read the text out loud as they copied it. 17 For all literate individuals, this highly oral mode of reading and writing emphasizes just how embedded in orality ancient Egypt remained.

Thus far, we have considered the relationship between orality and literacy in Egypt from an essentially synchronic perspective, without taking into account change over time. As the next section will show, the heavily oral nature of ancient Egypt throughout its history had a major impact upon the development of the major genres of written text.

Chronological developments

When we consider the full chronological sweep of Egyptian history, it becomes clear that writing became increasingly important to (and embedded in) Egyptian society as time passed. The invention of writing itself was a gradual development. Precursors of writing appear in the late Predynastic, with current scholarship regarding as particularly significant the ivory and bone labels from Abydos tomb U-j (dating to roughly 3350 BC and recording location names and quantities of goods). 18 Dynasties 0 and 1 ( c .3200–2890 BC) witness the first translatable writings of royal names. Fully syntactic written texts did not appear until the Second Dynasty ( c .2890–2686 BC). 19 Similarly, there is no specific watershed moment marking the transition from ‘orality’ to ‘literacy’, but only a slow shift from one end of the spectrum to the other. 20

For the Old Kingdom ( c .2686–2160 bc ), intersections between orality and literacy are particularly apparent in the Pyramid Texts. Some features of the Pyramid Text spells are best interpreted as traces of their oral ‘prehistory’. The majority of the corpus is ‘oral-poetic’ in style, displaying the kind of word order permutation and loose juxtaposition of ideas we expect of oral composition. 21 There are also places where the Pyramid Texts mix dialects and older and newer forms of the language, features resulting from the slow accrual of oral material over time (a phenomenon also found in the Homeric epics). Critically, however, the spells do not reflect completely direct transcriptions from the oral tradition, for there are also key ways in which they have been modified to fit their current monumental context. In many cases, original first person pronouns (used by the king as active speaker) were changed to the third person, the king consequently becoming the addressee playing a passive role. Such pronoun changes were typically necessary when ‘individual’ rites, such as services recited by living individuals for Osiris, Re, and the dead, were adapted for use on behalf of the deceased. In these cases, the text owner was shifted from speaking officiant to beneficiary; that is, he was now addressed as Osiris, etc. 22 With this shift, a new explicit reciter was not introduced, making the spell more suitable for a permanent monumental setting. Such modifications are typically assumed to have taken place as the spells were being reworked for carving on pyramid walls. 23 A more logical timeframe, however, would seem to be the moment when a spell initially derived for use by a living individual was first adopted for funerary contexts—unless we assume a stand-in reciting for the deceased.

This kind of transformation of text could also occur in the other direction, from ‘written’ to ‘oral’. A few Pyramid Texts (offering spells in particular) are laid out in the form of a table and thus likely were derived from older written offering lists. 24 Although the Pyramid Text versions include verbs, Baines suggests that their precedents were completely non-syntactic tabular lists. The addition of verbs to the Pyramid Texts would have made them more ‘performable’, a process which Baines describes as a ‘strategy of adding a field to the table in order to activate it’. 25

The development of the written tomb biography in the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties also has strong connections to the oral performative sphere. Full narrative text first appears in the early Fifth Dynasty in the tombs of Debehni, Niankhsakhmet, Washptah, and Rawer. 26 These tombs do not present full life stories of their owners, but rather key moments that illustrate the favour they received from the king. Rawer, for example, has become famous in modern scholarship for the pardon he received from Neferirkara ( c .2475–2455 bc ) after the king’s sceptre blocked Rawer’s way. 27 Baines suggests that these written narratives do not describe incidents that occurred spontaneously, but rather events that were carefully staged in advance as ceremonial occasions—in other words, performances. 28 To Julie Stauder-Porchet, the fact that such scenes were inscribed explicitly at the behest of the king explains their use of the third person. 29 These individual scenes formed the basis for the more comprehensive first-person ‘event’ biographies of the Sixth Dynasty, in which the tomb owner now appears as the true agent of his own life story.

The appearance of written literary texts at the beginning of the Middle Kingdom provides another avenue by which to approach questions of orality and literacy. Scholars have long recognized the integral role played by oral performance in the dissemination of Egyptian literary texts. Richard Parkinson has even developed a ‘conjectural reconstruction’ of a performance of The Tale of Sinuhe and The Eloquent Peasant , giving this imagined performance the setting of the palace of the mayor of Elephantine during the reign of Senusret II ( c .1877–1870 bc ). 30

The Tale of Sinuhe and The Eloquent Peasant , along with The Shipwrecked Sailor , are ancient Egypt’s earliest fictional narratives (see Chapter 50 in this volume). In structure, the three tales are quite different, but each draws in a variety of ways from precedents both oral and written. Sinuhe is framed as a tomb biography, a written genre that itself invokes oral performance through its first-person presentation of a life story from beyond the grave. Embedded in the tale are copies of written letters said to be exchanged between Sinuhe and Senusret I, along with examples of the overtly oral genres of royal praise hymn and lament. Along the same lines, The Shipwrecked Sailor draws on the written genre of the official expedition report and exhibits intertextualities with elite religious texts that would have been quite restricted in their circulation. 31 In tone, however, it is more reminiscent of a folktale, a characteristic that it shares with the narrative of The Eloquent Peasant . 32 In the case of The Eloquent Peasant , the narrative is a frame story interrupted by nine embedded petitions spoken by the peasant as a plea for justice. Despite this ostensibly ‘low culture’ oral origin, these petitions represent a highly stylized display of rhetoric. 33

Sinuhe , The Shipwrecked Sailor , and The Eloquent Peasant petitions are all quite complex in their grammar. 34 In contrast, the Eloquent Peasant frame story is simpler, being constructed predominately of independent main clauses. Such linguistic simplicity is also a key feature of tales ascribed to a ‘low tradition’ of Egyptian literature, first appearing in writing in the late Middle Kingdom. 35 Members of this low tradition (best exemplified by Papyrus Westcar) are composed of loosely linked episodes, often overtly humorous, and thus stand in sharp contrast to the earlier tales of Sinuhe and The Shipwrecked Sailor , with their more serious tone and carefully integrated cyclical structure. The later Middle Egyptian tales are stylistically quite similar to one another and do not exhibit the kind of experimentation with different genres that is characteristic of their predecessors. As a result, this ‘low tradition’ would seem to represent a standardization of the written literary tradition as it developed, probably under the influence of contemporary oral storytelling practices.

The later New Kingdom witnessed a further expansion of written literature, with the appearance of fairy-tale like stories (most notably The Doomed Prince and The Tale of Two Brothers ) and love poetry. In all likelihood, both genres had their roots in the oral tradition. Their written forms are, however, complex in their language use, employing what is called ‘literary Late Egyptian’. This artificial form of the language mixes older Middle Egyptian constructions with newer Late Egyptian ones, and its origins are unknown. Was it a written construct of the scribal elite used exclusively for ‘high culture’ literary purposes, or did it develop in the oral tradition? Both possibilities are viable. Despite this uncertainty, it seems reasonable to assume that the appearance of the genres of fairy tale and love poetry in written form during the later New Kingdom was tied to broader trends of linguistic change. Moreover, these phenomena were themselves impacted to some degree by the upheaval of the Amarna period. 36

In the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, demotic became the language and script of Egyptian literary compositions. Again, it is impossible for us to know just how closely the language of the so-called ‘demotic tales’ (such as the Setne and Pedubast ‘cycles’; see Chapter 55 in this volume) reflected oral story-telling practices, but demotic was at least more closely congruent with contemporary spoken discourse than earlier phases of the language. The demotic tales tend to be highly episodic in structure, continuing a trend that began with the ‘low tradition’ of Middle Egyptian stories. 37 In fact, a number of demotic tales give the impression of having been cobbled together from a variety of previously existing independent sources, some written and some oral. 38 Across the corpus we find repeated the same basic formulaic phrases, stock characters, and scenes, elements that, I would argue, most likely had their origin in the oral tradition. 39

When we shift our focus from literature to legal and business contracts, we find once again that oral performance remained the foundational principle throughout ancient Egyptian history. 40 The most basic (and earliest) way to enact a transaction was to make an oral declaration before witnesses, and the oral element was retained even after the option arose to record the transaction in writing. 41 Written documentation was first used only in the most unusual cases, when a future legal challenge was viewed as a distinct possibility. 42 In such instances, the written text was drawn up to protect the interested parties and their descendants. In fact, Eyre argues that the very process of gathering the interested parties to draw up the document was functionally more important than any potential future use it might hold as a written record. A will ‘kept secret until death, or only made on the point of death, would be pointless: it would not hold water, and would not prevent challenge. The agreement of interested parties was necessary in advance, and could not be compelled or overridden by a document’. 43 Moreover, in cases where written records were later consulted, the documentation clearly possessed severe limitations. In the Nineteenth-Dynasty land dispute of the family of Mose, for example, texts consulted were often inconclusive or contradictory and the living witness was relied upon as the ultimate authority. 44 The identification of witnesses is a key component of the early Twenty-second-Dynasty ‘oracular property decree’ of Iuwelot, High Priest of Amun, in which he transferred a number of properties to his son, Khaemwase. In this decree, Iuwelot lists the people from whom he had purchased these properties as a way to prove his ownership; presumably he could not provide written documentation for these transactions because they had been confirmed orally. 45 In fact, Brian Muhs sees the development of the oracular property decree as a reaction to the many disputes that had arisen in the New Kingdom as a result of the predominately verbal nature of property transfer at that time. As proof of legal acquisition, the oracular property decrees were themselves somewhat limited (in part because they were accessible only to the royal family and highest clergy). To Muhs, these limitations explain why oracular property decrees were replaced by notary contracts, which first appear in the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. 46

The appearance of notary contracts is only one aspect of a broader shift toward a more fully independent use of written documentation. When legal and business transactions are recorded in writing, it is important to identify the exact relationship between the written document and real-world action. According to Speech-Act theory as developed by J.L. Austin in his monograph How to Do Things with Words (1962), performative utterances are meant to have a specific, pragmatic ‘illocutionary’ force: they get things done. With the appearance of written documents tied to such practical ends, the key question becomes whether the written document itself qualifies as performative utterance, or simply serves as a record of a truly binding oral performance. In other words, can the text stand autonomously? In the case of Ramesside royal decrees and private legal documents, Arlette David concludes that such texts were not used autonomously. 47 Eyre agrees, arguing that the shift from document as simple aide-memoire to document as written instrument guaranteeing transaction never fully occurred in ancient Egypt. 48 However, in private legal documents from later Twentieth-Dynasty Deir el-Medina we begin to find new elements, like a curse in the Adoption Papyrus, that mark the beginnings of the movement toward the use of the written text as an autonomous performative instrument. 49

This trend intensifies in the Late Period and Ptolemaic and Roman periods, as particularly evident through changes in the use of witnesses. In New Kingdom Deir el-Medina, the local council ( qnbt ), organized by the head village scribe, could be called upon both to make decisions and to serve as witness. The scribe (‘local witness par excellence ’) 50 wrote the text and recorded the names of all of the witnesses present. Post-Ramesside documents shift the focus from the council to the scribe; at the same time, individual witnesses began to write their own names. This new importance of the personal signature would have made the document itself a stronger witness at a future date if the original witness himself could not be called upon. 51 In some particularly elaborate early cases, each witness recorded not just his name, but the full text of the contract as well. 52 For the production of these documents, Baines imagines a ceremonial setting combining the oral and the written, with each witness speaking the words of the contract out loud as he copied them before the entire group. 53

The act of writing itself clearly carried great symbolic weight in such circumstances. Notable in this respect are a number of elaborate marriage contracts of the Ptolemaic period characterized by text written in a large, archaizing hand, with large borders of blank papyrus (the latter feature a kind of ‘conspicuous consumption’ of expensive papyrus). 54 Moreover, existing documentation was an integral component of all successive transactions. For example, land transfer documents (common in the Late Period and Ptolemaic and Roman times) contain formulae indicating that it was necessary for the seller to pass over all related older documents in order to guarantee the buyer’s property rights. 55 This need to preserve old documents led to the phenomenon of family and professional archives that are now so useful to the modern scholar. It must also be stressed, however, that given the high levels of illiteracy even in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, fully oral transactions must have continued to take place. In other words, the creation of a written document never became a mandatory element of transactional processes.

We do, however, find a sharp increase in the number of private business and judicial documents produced at Deir el-Medina; these first appear in the Nineteenth Dynasty and spike in the Twentieth. Once the use of writing for everyday purposes had been introduced to the villagers by the upper administration, the residents of Deir el-Medina seem to have seen its benefits and adopted it for their own purposes. 56 Ben Haring sees some of the formulae used in this documentation as direct transcripts from oral practice (such as the oral deposition formulae ỉr ỉnk , ‘as for me’, and twỉ dỉ.t rḫ , ‘I inform’). Other formulae, however, are more abbreviated, and in these Haring identifies the development of written scribal conventions. 57 He sees these abbreviated ‘scribal’ formulae as distinct from the narrative body of the text, usually occurring ‘as introductions or additions to narrative texts’. 58 To Haring, the predominately narrative style of these documents is a mark of orality. As David notes, however, narrative is an essential component of the legal genre as a whole. Even in modern, fully literate contexts ‘a legal case is also a story, and depositions remain verbal presentations recorded by the competent authority’. 59

New uses of writing in the private sphere continued to develop in the Late Period. The Twenty-fifth Dynasty witnessed the appearance of lease contracts recording in writing an annual agreement between the land-holder and the farmer being engaged to work the land. The agreements themselves were not particularly unusual, and so the practice of recording them in writing may have begun among the highly literate community of priests in Upper Egypt and spread from there into other segments of society. 60

The advent of foreign rule in the Ptolemaic and Roman periods witnessed new developments in the use of documents as a means of governmental control, as evidenced, for example, in the appearance of individual tax receipts, a state bank, and auctions of tenure. This period also saw the legal establishment of professionalized, government-appointed notaries as the only individuals who could draw up demotic documents, along with the requirement that demotic contracts be registered in government offices. 61 Various explanations for these changes can be proposed. Drawing upon the work of Walter Ong, one might take them as a mark of the influence of the more fully ‘literate’ Hellenistic and Roman worlds upon Egypt. However, it seems more reasonable to view them as practical devices mobilized by foreign powers to facilitate their control of a conquered territory. 62

Current debates

While a great deal of recent scholarship has emphasized the continued influence of oral modes of behaviour throughout the Pharaonic period and beyond, there can be no doubt that the invention of writing was an integral component of the development of complex state-level society in ancient Egypt. The question remains, however, as to what extent the use of writing changed actual modes of thinking in ancient Egypt. As we have seen, Walter Ong’s theories focus on the cognitive change brought about by the Greek alphabet in particular, an emphasis that derives in large part from an article by Jack Goody and Ian Watt. 63 Significantly for our purposes, Goody himself later argued that non-alphabetic writing systems also brought about cognitive change. 64 This later work focuses on the activity of list-making made possible through writing, noting that the visual representation of material in a list possesses abstract qualities very different from the flow of oral discourse. 65 Ultimately, Goody concludes that lists are ‘an example of the kind of decontextualization that writing promotes’, resulting in a ‘change in “capacity”’ that ‘gives the mind a special kind of lever on “reality”’. 66 As evidence, he explores in detail early Mesopotamian and Egyptian lists (including the ‘onomastica’ of the late Middle Kingdom and Twentieth Dynasty). The kind of lexical list represented by the Egyptian onomastica requires the classification of the universe in particular ways, thereby impacting how individuals perceive the world around them. To Goody, such classifications change not only the worldview of the literate members of a society, but also of the illiterate and of children who have not yet been taught to read. 67 In contrast, Baines argues that it is only in the modern age of widespread literacy that writing can be viewed as a catalyst for cognitive change. Instead, in pre-modern societies ‘Literacy is a response more than a stimulus. It may be a necessary precondition for some social and cognitive change, but it does not cause such change’. 68 For Baines, these words obviously hold true for the specific case of ancient Egypt.

Another major debate within Egyptology surrounds the degree to which the administrative structure of the country before the Ptolemaic and Roman periods depended upon writing and bureaucratic systems. The answer to this question in turn affects our understanding of the extent of state control in ancient Egypt. For the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, the successful collection of the various annual ‘poll’ or ‘capitation’ taxes (personal taxes levied at fixed rates), for example, clearly required relatively comprehensive census documents, which themselves speak to quite a high degree of state control. 69 Debates arise, however, when we attempt to identify seemingly similar practices in more scantily documented earlier periods. To what extent can we extrapolate backward from the evidence of the Ptolemaic–Roman period? When publishing a series of household lists from Twentieth-Dynasty Deir el-Medina, for example, Robert Demarée and Dominique Valbelle take these documents as evidence of a systematic registration system of the central government. 70 In contrast, Fredrik Hagen argues for a far more minimalist interpretation, viewing the same set of documents as a highly localized phenomenon motivated by the specialized nature of the site of Deir el-Medina. 71

Eyre makes the same essential argument for the administrative structure of the Pharaonic period as a whole (see Chapter 36 in this volume), presenting a model of a diffuse and yet highly effective hierarchy of control in which specific local affairs of little concern to the central state were delegated to the local level, and typically conducted orally. Such was the case for the collection of taxes, for example; Eyre suggests that neither central land registers nor a formal national census existed. 72 Land registers like the Wilbour Papyrus were instead working documents used by tax assessors. 73 While such documents could be used as a starting point for the process of tax assessment, their acknowledged inaccuracies meant that they could not stand alone. Effective assessment also required regular personal interaction between agents of the central government and the local authorities. The resulting system was ‘rather ramshackle, with layers of competing interests…and necessarily depended on negotiation between collectors, local agents, and farmers’. 74 These kinds of negotiations are illustrated by the Twentieth-Dynasty P. Valençay I, a letter in which the mayor of Elephantine complains of improper field and tax assessment to the chief taxing master. 75 While ‘ramshackle’, the system of the Pharaonic period seems to have achieved a necessary balance. Significantly, attempts towards greater standardization and rationalization in the Ptolemaic period and beyond were often met with rebellion. 76

Eyre’s analysis of the Duties of the Vizier (surviving in New Kingdom tomb copies, e.g. in the tomb of the vizier Rekhmira at Thebes) presents the same basic picture of highly personal (and largely oral) government activity. We find no evidence of a ‘paper-based office administration’ or a ‘defined structure of line management’ within the administration. 77 Instead, the process of government was probably carried out on a face-to-face and largely ad hoc basis. The vizier himself was required to hear oral petitions and appeals, and he sent agents throughout the country to carry out his orders and attend to local concerns. Documents sent with such government envoys served to legitimize the authority of these officials, but did not replace their presence. 78

As is so often the case, our current inability to conclusively resolve these debates concerning the nature of governmental activity in ancient Egypt stems largely from the patchy nature of the surviving documentary record. It is always problematic to draw conclusions based on the assumption of the existence of documentation that has not survived, and at the same time, new discoveries may well challenge conclusions based on the premise that such hypothetical documents never existed. Despite these difficulties, current scholarship’s growing awareness of the continuing influence of orality on ancient Egypt long after the invention of writing has without question produced a better-rounded picture of the society as a whole, and the relationship between orality and literacy must continue to be taken into consideration.

Suggested reading

Ong 1982 is foundational to the study of orality and literacy. Redford 2000 : 143–218 and Baines 2007 : 146–78 are wide-ranging introductory surveys of the topic as it relates to ancient Egypt. Reintges 2011 , Eyre 2013 , and Jay 2016 provide focused studies of specific text genres. The literary analyses of Parkinson (especially 2002 and 2009 ) are deeply informed by the performative nature of ancient Egyptian literature. McDowell 2000 serves as an introduction to issues of scribal education.

Austin, J.L. 1962 . How to Do Things with Words . Oxford: Clarendon.

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Baines, J. 1990 . Interpreting the story of the Shipwrecked Sailor, Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 76: 55–72.

Baines, J. 1999 . Prehistories of Literature: Performance, Fiction, Myth. In G. Moers (ed.), Definitely Egyptian literature: proceedings of the symposium ‘Ancient Egyptian literature: history and forms’, Los Angeles, March 24–26, 1995 . Göttingen: Lingua Aegyptia, 17–41.

Baines, J. 2004 . Modelling Sources, Processes, and Locations of Early Mortuary Texts. In S. Bickel and B. Mathieu (eds), D’un monde à l’autre: Textes des Pyramides et Textes des Sarcophages . Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, 15–41.

Baines, J. 2007 . Visual and written culture in ancient Egypt . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brunner-Traut, E. 1979 . Wechselbeziehungen zwischen schriftlicher und mündlicher Überlieferung im Alten Ägypten, Fabula: Zeitschrift für Erzählforschung 20: 34–46.

David, A. 2006 . Syntactic and Lexico-Semantic Aspects of the Legal Register in Ramesside Royal Decrees . Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

David, A. 2010 . The Legal Register of Ramesside Private Law Instruments . Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Demarée, R. and D. Valbelle . 2011 . Les registres de recensement du village de Deir el-Medineh (Le ‘Stato Civile’) . Leuven: Peeters.

Depauw, M. 1994 . The Demotic Epistolary Formulae, Acta Demotica. Acts of the Fifth International Conference for Demotists = Egitto e Vicino Oriente 17: 87–94.

Enmarch, R. 2011 . Of Spice and Mine: The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and Middle Kingdom Expedition Inscriptions. In F. Hagen et al. (eds), Narratives of Egypt and the Ancient Near East: Literary and Linguistic Approaches . Leuven: Peeters, 97–121.

Eyre, C. 2013 . The Use of Documents in Pharaonic Egypt . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gardiner, A.H. 1941 and 1948. The Wilbour Papyrus . 3 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goody, J. 1977 . The Domestication of the Savage Mind . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goody J. and I. Watt . 1963 . The Consequences of Literacy, Comparative Studies in Society and History 5: 304–45.

Hagen, F. 2016 . Review of Demarée, R. and Valbelle, D. Les registres de recensement du village de Deir el-Medineh (Le ‘Stato Civile’) , JEA 102: 205–12.

Haring, B. 2003 . From Oral Practice to Written Record in Ramesside Deir El-Medina, Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 46: 249–72.

Havelock, E.A. 1963 . Preface to Plato . Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Hays, H. 2012 . The Organization of the Pyramid Texts: Typology and Disposition . Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Hughes, G.R. and R. Jasnow 1997 . Oriental Institute Hawara Papyri: Demotic and Greek texts from an Egyptian family archive in the Fayum (fourth to third century b.c.) . Chicago: Oriental Institute.

Jay, J. 2016 . Orality and Literacy in the Demotic Tales . Leiden; Boston: Brill.

Junge, F. 2001 . Late Egyptian Grammar: An Introduction . Translated by D. Warburton . Oxford: Griffith Institute.

Katary, S.L.D. 1989 . Land Tenure in the Ramesside Period . London: Kegan Paul International.

MacArthur, E. 2010 . The Conception and Development of the Egyptian Writing System. In C. Woods (ed.), Visible Language: Inventions of Writing in the Ancient Middle East and Beyond . Chicago: Oriental Institute, 115–21.

McDowell, A. 2000 . Teachers and Students at Deir el-Medina. In R.J. Demarée and A. Egberts (eds), Deir el-Medina in the Third Millenium ad: A Tribute to Jac. J. Janssen . Leiden: Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten, 217–33.

Muhs, B.P. 2005 . Tax Receipts, Taxpayers, and Taxes in Early Ptolemaic Thebes . Chicago: Oriental Institute.

Muhs, B.P. 2009 . Oracular Property Decrees, in their Historical and Chronological Context. In G.P.F. Broekman , R.J. Demaree , and O.E. Kaper (eds), The Libyan Period in Egypt: Historical and Cultural Studies into the 21st–24th Dynasties: Proceedings of a Conference at Leiden University, 25–27 October 2007 . Leiden; Leuven: NINO; Peeters, 265–75.

Ong, W.J. 1982 . Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word . London; New York: Methuen.

Parkinson, R. 2002 . Poetry and Culture in Middle Kingdom Egypt: A Dark Side to Perfection . London; New York: Continuum.

Parkinson, R. 2009 . Reading Ancient Egyptian Poetry: Among Other Histories . Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Parkinson, R. 2012 . The Tale of the Eloquent Peasant: A Reader’s Commentary . Hamburg: Widmaier Verlag.

Ragazzoli, C. 2010 . Weak Hands and Soft Mouths: Elements of a Scribal Identity in the New Kingdom, Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 137: 157–70.

Rathbone, D. 1993 . Egypt, Augustus and Roman taxation, Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz 4: 81–112.

Redford, D.B. 2000 . Scribe and Speaker. In E. Ben Zvi and Floyd, M.H. (eds), Writings and Speech in Israelite and Ancient Near Eastern Prophecy . Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature, 143–218.

Reintges, C.H. 2011 . The Oral-Compositional Form of Pyramid Text Discourse. In F. Hagen et al. (eds), Narratives of Egypt and the Ancient Near East: Literary and Linguistic Approaches . Leuven: Peeters, 3–54.

Stauder, A. 2013 . Linguistic Dating of Middle Egyptian Literary Texts, ‘Dating EgyptianLiterary Texts’: Göttingen, 9–12 June 2010 , Volume 2. Hamburg: Widmaier Verlag.

Stauder-Porchet, J. 2017 . Les autobiographies de l’Ancien Empire égyptien: Étude sur la naissance d’un genre . Leuven: Peeters.

Simpson, W.K. (ed.) 2003 . The Literature of Ancient Egypt: An Anthology of Stories, Instructions, Stelae, Autobiographies, and Poetry . Third ed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Strudwick, N.C. 2005 . Texts from the Pyramid Age . Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature.

Tassier, E. 1992 . Greek and Demotic School-Exercises. In J.H. Johnson (ed.), Life in a Multi-Cultural Society: Egypt from Cambyses to Constantine and beyond . Chicago: Oriental Institute, 311–15.

Thomas, R. 1992 . Literacy and Orality in Ancient Greece . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vinson, S. 2017 . The Craft of a Good Scribe: History, Narrative and Meaning in the First Tale of Setne Khaemwas . Leiden: Brill.

Ong 1982 , especially p. 81.

See, for example, Thomas 1992 : 18–19.

Redford 2000 : 143–218; Baines 2007 : 146–78.

Redford 2000 : 145.

Eyre 2013 : 289. For extensive discussion and a wide variety of examples, see Eyre 2013 : 277–98.

Eyre 2013 : 291.

An important early contribution along much the same lines is Brunner-Traut 1979 .

Baines 2007 : 170.

Ong 1982 : 32.

Eyre 2013 : 94–5.

Depauw 1994 : 89.

For fuller discussion and bibliography, see Jay 2016 : 10.

Baines 2007 : 162–3.

Tassier 1992 : 313.

Simpson 2003 : 157. See also McDowell 2000 : 218.

McDowell 2000 : 220–3 and 230.

Ragazzoli 2010 : 160. To Ragazzoli, ‘For scribes, hands and mouths are the two human tools necessary for reading and writing…The hand is what holds the reed and the mouth is where the sounds of reading are produced and take place’.

MacArthur 2010 : 115–21. See also Chapter 28 in this volume.

Baines 2007 : 137–9. In contrast, Redford suggests that continuous text was already present in the First Dynasty. Redford 2000 : 150, n. 19.

However, Baines sees the Middle Kingdom as an important turning point in this transition; see Baines 2007 : 147.

Reintges 2011 : 36.

Hays 2012 : 259; for the basic distinction between ‘individual’ and ‘collective’, see Hays 2012 : 17–20.

Hays 2012 : 259; Reintges 2011 : 28.

In fact, Baines sees the offering lists in the mortuary temple of Sahura as the earliest attestation of the Pyramid Texts. Baines 2004 : 21–2.

Baines 2004 : 24–5 and 40.

Strudwick 2005 : #200, #225, #235, #227.

Strudwick suggests that Rawer may have tripped over the sceptre. Strudwick 2005 : 305.

Baines 1999 : 21–4.

Stauder-Porchet 2017 : 71–3; 164–5; 312–13.

Parkinson 2009 : 20–68. For a basic overview of ancient Egyptian literary texts, see Chapter 50 in this volume. For a more extensive discussion of the relationship between written ancient Egyptian literature and the oral tradition, see Jay 2016 . For translations of many of the texts discussed below, see Simpson 2003 .

Enmarch 2011 : 103–11; Baines 1990 : 62–4.

Baines 1990 : 57–65.

Parkinson 2012 : 3–4.

They are characterized by ‘complex sequences of asyndetically joined clauses’. Stauder 2013 : 118.

Parkinson 2002 : 138–46.

Baines see the written examples of love poetry from the later New Kingdom as a result of changes in decorum at that time. Baines 2007 : 161. For a nuancing of Akhenaten’s role in the appearance of Late Egyptian as a written form of the language, see Junge 2001 : 20–3.

A particularly notable exception is Setna I, which displays a highly intricate story-within-a-story structure with multiple conscious mirrorings between the different diagetic levels. Vinson 2017 .

For discussion of the specific examples of Setna II and Mythus, see Jay 2016 : 225–44; 250–5.

Jay 2016 , especially chapters 3 and 4 .

For a basic overview of ancient Egyptian socio-economic texts, see Chapter 51 in this volume.

Eyre 2013 : 117–18.

Eyre 2013 : 103–4. The earliest extant legal papyri date to the late Old Kingdom. Eyre discusses in detail an early example from a late-Sixth-Dynasty family archive from Gebelein.

Eyre 2013 : 106.

Eyre 2013 : 155–62, especially 162. This dispute was recorded in Mose’s tomb at Saqqara.

Muhs 2009 : 268–9.

Muhs 2009 : 272–5.

David 2006 : 39–40; David 2010 : 4–9.

Eyre 2013 : 101.

David 2010 : 263.

Eyre 2013 : 113.

Eyre 2013 : 115–19.

The Saite Oracle papyrus is a notable example. Baines 2007 : 166.

Baines 2007 : 163–6.

See, for example, several of the contracts published in Hughes and Jasnow 1997 .

Eyre 2013 : 166. See also the related documentation accompanying the wills of Wah and Naunakhte. Eyre 2013 : 106–8; 264–5.

Haring 2003 : 266.

Haring 2003 : 260 and 262.

Haring 2003 : 262.

David 2010 : 7.

Eyre 2013 : 188–9.

For a summary and bibliography of these developments, see Eyre 2013 : 121; 199.

See also Eyre 2013 : 354.

Goody and Watt 1963 : 304–45. Ong’s other major influence was Havelock 1963 .

Goody 1977 : 74–111.

Similarly, Ong argues that abstract, neutral lists separated from the human context are impossible for an oral society. Ong 1982 : 42–3.

Goody 1977 : 109.

Goody 1977 : 109–10.

Baines 2007 : 62. And even in Greece, Baines sees literacy as only one of many factors motivating cognitive change. Baines 2007 : 60–2.

For the poll taxes of the early Ptolemaic period (particularly important being the yoke and salt taxes), see Muhs 2005 : 29–60. For the poll tax established by Augustus (from which citizens of Alexandria were exempt), see Rathbone 1993 : 86–99.

Demarée and Valbelle 2011 .

Hagen 2016 : 205–6.

Eyre 2013 : 182–3; 232.

The editio princeps of the Wilbour Papyrus is Gardiner 1941 and 1948. For discussion, see Katary 1989 .

Eyre 2013 : 201.

Eyre 2013 : 174–5.

Eyre 2013 : 192–3; 197–9.

Eyre 2013 : 77.

Importantly, Eyre’s model assumes a far more integrated administrative use of written and oral sources than does Redford’s. Compare, for example, Redford 2000 : 172.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- International

- Art & Design

- Health & Wellness

- Life & Society

- Sustainability

- Entrepreneurship

- Film & TV

- Pop Culture

Quality Journalism relies on your support

Subscribe now and enjoy unlimited access to the stories that matter.

Don’t have an account?

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Forgot Password?

Quality Journalism relies on your support.

Already have an account?

Egyptian Streets

Independent Media

Summer Read Suggestions: 11 Literary Works by Egyptian Writers

By Egyptian Streets

Egyptian literature is suffused with inspiring and thoughtful masterpieces. Nonetheless, it is quite a challenge to find contemporary Egyptian literature in English or in translation, as such, Egyptian Streets has compiled a list of 11 poems, short stories and one essay to give literature enthusiasts a taste of contemporary works from a variety of Egyptian authors. These works were mostly published in Arabic, and many in print, but they have been compiled here to give the modern reader ease of access.

1.’Solitude’ by Doria Shafik (poetry)

One of the most iconic feminists of Egyptian modern history, Doria Shafik is well-known for her political activism and advanced education. Not only was she editor in chief of Bint Al Nil (Daughter of the Nile) and La Femme Nouvelle (The Modern Woman), she also founded an Egyptian feminist organization and lead women to storm Parliament to obtain their right to vote.

It’s important to note that Shafik herself was a great translator, having translated the Quran to French and English, and was a prolific writer of fiction essays as well as poetry.

Her poetry took on a philosophical tone, which is understandable considering Shafik earned a doctorate in philosophy from the Sorbonne. Her freestyle extensively tackles notions of love, freedom, exploration and activism.

Find her work here .

2.’The fairest faith’ by Anthony Fangary

It is crucial for Egypt’s contemporary literature scene to reflect the diverse voices which live in it. One perpetually missing voice is that of Copts in literature, whether fiction or nonfiction. Anthony Fangary, whose poetic works can be found in Anomaly, Left-Hooks, University of Iowa’s BARS, is a Coptic-Egyptian American who poignantly reflects the themes of faith, discrimination, identity and Coptic Christianity in his work.

The San-Francisco based writer’s work overflows with emotion and powerful imagery. It suffuses typical language of Egyptian Coptic culture, such as ‘orban’, ‘ezayak’ and ‘abouna’ (father) into the largely English-written poetry, also evoking local places and practices.

Find his work here .

3.’Arabs on the Beach’ by Noor Naga (essay)

A wonderful read which makes one reflects about city dwellers and desert dwellers in Egypt as well as Egyptian customs of vacationing, this essay provides a glimpse into the complicated lives of Arabs (sometimes called Bedouins) who live in the North coast of the country. The essay is replete with anthropological and historical musings with personal reflections of the author.

It tackles the subject of tribe politics, vengeance, crime and blood money all while maintaining a smooth writing style which keeps one mesmerized from start to finish.

The piece was written by Alexandrian writer Noor Nagga who admits to having lived in the United Arab Emirates for an extended time in the piece. Nagga’s work was featured in other publications such as Arc Poetry Magazine and Nashville review. Another essay of hers “Mistresses Should be Muslim Too” was published in The Walrus. Winner of 2017 Bronwen Wallace Award and the 2018 Disquiet Fiction prize, her upcoming book “The Mistress Washes Prays” will be out in spring 2020.

4. ‘Half a day’ by Naghuib Mahfouz (short story)

One of the few iconic writers on this list who do not need an introduction, Mahfouz is Egypt’s most famous contemporary writer, most known for his ‘Cairo Trilogy’. He received a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988 which many of his works having been adapted to films and TV series. His most well-known works, many of which dealing with the subjects of existentialism- he was a great enthusiast of philosophy-, Egyptian politics, and society are ‘Sugar Street’, ‘Midaq Alley’, ‘Miramar’ and ‘Palace Walk.’

His short story ‘Half a day’ explores the passage of time, bewilderment and growth.