An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Physical Fitness and Exercise During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Enquiry

Harleen kaur.

1 Freelance Researcher and Activist, Jaipur, India

2 Department of Psychology, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India

Tushar Singh

Yogesh kumar arya, shalini mittal.

3 Amity Institute of Behavioural and Allied Sciences (AIBAS), Amity University Uttar Pradesh, Lucknow, India

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought this fast-moving world to a standstill. The impact of this pandemic is massive, and the only strategy to curb the rapid spread of the disease is to follow social distancing. The imposed lockdown, resulting in the closure of business activities, public places, fitness and activity centers, and overall social life, has hampered many aspects of the lives of people including routine fitness activities of fitness freaks, which has resulted in various psychological issues and serious fitness and health concerns. In the present paper, the authors aimed at understanding the unique experiences of fitness freaks during the period of lockdown due to COVID-19. The paper also intended to explore the ways in which alternate exercises and fitness activities at home helped them deal with psychological issues and physical health consequences. Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted with 22 adults who were regularly working out in the gym before the COVID-19 pandemic but stayed at home during the nationwide lockdown. The analysis revealed that during the initial phase of lockdown, the participants had a negative situational perception and a lack of motivation for fitness exercise. They also showed psychological health concerns and overdependence on social media in spending their free time. However, there was a gradual increase in positive self-perception and motivation to overcome their dependence on gym and fitness equipment and to continue fitness exercises at home. Participants also tended to play music as a tool while working out. The regular fitness workout at home during the lockdown greatly helped them to overcome psychological issues and fitness concerns.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic is a massive global health crisis ( Bavel et al., 2020 ) and rapidly spreading pandemic ( Bentlage et al., 2020 ) of recent times. As compared to the earlier pandemics the world has witnessed, the current COVID-19 pandemic is now on the top of the list in terms of worldwide coverage. This is the first time the whole world is affected simultaneously and struck strongly in a very short span of time. Initially, the death rate due to COVID-19 was around 2%, which has now increased to around 4–6% ( World Health Organization [WHO], 2020 ). The statistics does not look so severe, but the total number of cases and the rate at which these cases are increasing day by day make the situation alarming. Exponential growth in COVID-19 cases has led to the isolation of billions of people and worldwide lockdown. COVID-19 has affected the life of nearly each person around the world. The difference between personal or professional lives has narrowed due to work-from-home instructions, and people’s lives are revolving around these two due to the lockdown. People have also been pondering over a vital concern at home, i.e., the importance of their health and fitness.

Although imposing lockdown or quarantine for the population has been one of the widely used measures across the world to stop the rapid spread of COVID-19, it has severe consequences too. Recent multinational investigations have shown the negative effect of COVID-19 restrictions on social participation, life satisfaction ( Ammar et al., 2020b ), mental well-being, psychosocial and emotional disorders as well as on sleep quality ( Xiao et al., 2020 ), and employment status ( Ammar et al., 2020d ). Announcement of a sudden lockdown of all services and activities, except few essential services, by the authorities has resulted in a radical change in the lifestyle of affected people ( Jiménez-Pavón et al., 2020 ) and has severely impaired their mental health, which has been manifested in the form of increased anxiety, stress, and depression ( Chtourou et al., 2020 ). The sudden changes in people’s lifestyle include, but are not limited to, physical activities and exercise. Ammar et al. (2020a) have reported that COVID-19 home confinement has resulted in a decrease in all levels of physical activities and about 28% increase in daily sitting time as well as increase in unhealthy pattern of food consumption. Similar results are also reported by other researchers ( Ammar et al., 2020c ; de Oliveira Neto et al., 2020 ) as well. Although these abrupt changes have influenced every individual, many people who were regularly following their fitness activities in gyms, or in the ground, or other places before the lockdown have been affected intensely. Closure of fitness centers and public parks has forced people to stay at home, which has disturbed their daily routines and hampered their fitness activities. While compulsion to stay at home for a long period of time poses a challenge to the continuity of physical fitness, the experience of hampered physical activities, restricted social communication, uncertainty, and helplessness leads to the emergence of psychological and physical health issues ( Ammar et al., 2020a , c ). Varshney et al. (2020) have found that psychological problems are occurring in adults while adjusting to the current lifestyle in accordance to the fear of contracting the COVID-19 disease. However, effective coping strategies, psychological resources, and regular physical exercise can be helpful in dealing with such health-related problems during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Chtourou et al., 2020 ).

It is important to note that physical activities (PA) and exercise not only maintain physical and psychological health but also help our body to respond to the negative consequences of several diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and respiratory diseases ( Owen et al., 2010 ; Lavie et al., 2019 ; Jiménez-Pavón et al., 2020 ). In a recent review of 31 published studies, Bentlage et al. (2020) concluded that physical inactivity due to current pandemic restrictions is a major public health issue that is a prominent risk factor for decreased life expectancy and many physical health problems ( Jurak et al., 2020 ). Exercise is shown to keep other physical functions (respiratory, circulatory, muscular, nervous, and skeletal systems) intact and supports other systems (endocrine, digestive, immune, or renal systems) that are important in fighting any known or unknown threat to our body ( Lavie et al., 2019 ; Jiménez-Pavón et al., 2020 ).

Regular physical activity, while taking other precautions, is also considered effective in dealing with the health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic ( Chen et al., 2020 ). Researchers from the University of Virginia Health System ( Yan and Spaulding, 2020 ) suggests that regular exercise might significantly reduce the risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome, which is one of the main causes of death in COVID-19 patients. Exercise and physical activities have important functions for individuals’ psychological well-being as well ( Stathi et al., 2002 ; Lehnert et al., 2012 ). There is sufficient literature to show that exercise can play a vital role in the promotion of positive mental health and well-being (e.g., Mazyarkin et al., 2019 ). However, when health promotion activities such as sports and regular gym exercises are not available in this pandemic situation, it is very difficult for individuals to meet the general WHO guidelines (150 min moderate to mild PA or 75 min intensive PA per week or combination of both) (cf. Bentlage et al., 2020 ). Amidst this pandemic-related restriction (home confinements and closed gyms, parks, and fitness centers), how people cope up and find ways to continue their physical fitness remains an important question.

Rationale for the Present Research

Since the onset of this disease, people have been confined to their homes, which has not only resulted in various psychological health issues but also challenged their physical fitness and health ( Ammar et al., 2020a , b , c , d ; Chtourou et al., 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ). Although this pandemic situation has led to the unexpected cessation of almost all the outside routine activities of all the individuals, it has profoundly hampered the physical activities of fitness freaks (those who regularly go to the gym for their physical fitness), as gyms and other such places have been shut down due to the lockdown. However, studies addressing the issues of fitness freaks, who used to spend a significant amount of time for regular workout in order to maintain their physical fitness, health, and appearance, seem to have found no place so far in the literature in relation to the current pandemic situation. Supposedly, the unique experiences of such people, their health issues, and the ways in which they have dealt with these issues during the COVID-19 pandemic have remained underexplored.

Also, it is well-known that the COVID-19 pandemic has made it difficult for people to adequately maintain their normal physical activity patterns at home ( Ammar et al., 2020a ). There are plenty of studies that have addressed the impact of COVID-19 on physical activities of the general public ( Ammar et al., 2020a , b , c , d ; Chtourou et al., 2020 ; Xiao et al., 2020 ), demonstrated the significant decrease in physical activities and exercise patterns, and illustrated its ill effects on physical and mental health status. There is also a growing body of literature that suggests strategies to encourage people to be involved in home-based exercises and fitness activities ( Ammar et al., 2020a , b , c , d ; Chtourou et al., 2020 ; de Oliveira Neto et al., 2020 ). However, all these studies were conducted in the earlier phase of the pandemic. There is a lack of studies investigating the way in which people have dealt with the problems arising from the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown/home confinement. In fact, it would be interesting to explore how and to what extent people were able to follow and benefited from the workout at home advices. Therefore, the present research aims at understanding people’s unique experiences during the period of lockdown due to COVID-19 and exploring the ways in which regular exercise engagements helped them deal with the psychological and physical consequences of home confinement.

In order to gain a rich and extensive understanding of experiences into people’s lives during this pandemic and their efforts to maintain a healthy lifestyle, a qualitative approach was adopted for the study. We used Interpretive Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) to delve into the participants’ perceptions and to provide a close picture of the participants’ unique experiences during the lockdown period.

Participants

A homogeneous sample of 22 participants was selected for this study. The criterion-based purposive sampling technique was used to identify and select the participants. We first contacted the gym owners/trainers and sought their consent to help us in the conduction of this study. Upon consent, we requested them to provide us with the details of their regular gym members who continuously go to the gym and do fitness exercises for at least 6 months prior to the imposed lockdown. Once the list was generated, the prospective participants were then connected by phone, were explained the purpose of the study, and were requested for their consent to participate. Those who consented for their inclusion in the study were then asked some questions based on the pre-decided inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. On the basis of this information, those participants who met the inclusion criteria (i.e., those who were continuing fitness workout in their home or hostels and were following strict home confinement measures during the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown) were further contacted and requested to provide an appointment for a telephone interview.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for the Participants

The participants meeting the following criteria were included in the study:

- • Individuals aged 18 years or older.

- • Individuals with no known history of physical and/or psychological illness.

- • Individuals who were doing regular gym workout for the last 6 months or more for at least 45 min daily before COVID-19.

- • Individuals who were completely dependent on gym exercise for their physical fitness.

However, individuals meeting the following criteria were not included in the study:

- • Individuals who were irregular or occasional gym visitors.

- • Individuals who were practicing other physical exercises besides gym workout.

- • Individuals with any physical and/or psychological conditions or individuals on any kind of medication.

Table 1 presents the demographic and exercise characteristics of the participants included in this study.

Demographic characteristics of the participants.

The purpose, importance, and relevance of the study were explained to the participants, and informed consent was obtained for their participation. All the participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and identity. Upon consent, the participants were requested to share their convenient time for a telephone interview. Semi-structured telephone interviews were conducted to explore the exclusive experiences of the participants with regard to their physical fitness during the lockdown. An interview schedule composed of non-directive, open-ended questions was prepared. There was no fixed order of questions; they were modified and re-modified as per the flow of the conversation with each participant. Some of the main questions prepared for the semi-structured interviews included “What is your perception of this situation we are currently living in?,” “What is your lockdown experience?,” “How frequently you used to go to gym for exercise before the lockdown was imposed?,” “How do you manage exercise at home?,” “What is your exercise schedule now?,” “What changes did you perceive in yourself during this lockdown?,” “How are you coping with this lockdown?,” “Did you experience any psychological issue during this period of time?,” “How do physical exercises help in combating the crisis you are facing?,” “What background aid do you use while exercising at home?,” “What is the need to use such aids while exercising?,” “How does fatigue impact you when you exercise during the lockdown?,” “What is the importance of proper sleep in following a regular schedule of exercise during this lockdown?,” “Do you miss your gym mates?,” “Do you feel you share an identity with your fellow gym mates?,” etc. Additional probing questions were also added as the need occurred during the individual interviews. In addition questions were also asked t o understand the differences between their pre and during COVID-19 lockdown fitness exercise patterns (see Table 2 ). All the interviews were conducted in the native language of the participants in Hindi and English. With due permission from the participants, the interviews were recorded. The interview time duration range was between 20 and 30 min. All the interviews conducted in Hindi were transcribed and then translated in English by the researchers. The translated interviews were then proofread by a native English speaker for correctness and consistency.

Pre- and during COVID fitness exercise information of the participants.

Analysis and Results

All the recorded interviews were transcribed. These transcripts were then analyzed using the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) framework to identify the participants’ experiences of lockdown, their alternative choice to continue their fitness routine, and its impact on their health. A stepwise progression method was used to analyze the data. At first, the researchers read the transcripts many times to get a deeper understanding of the experiences as described by the participants. In order to gain as close an understanding of the data as possible, the researchers listened to the audio recordings of the participants while reading the transcribed data.

In the following step, the attempts were made to transform the transcripts into a conceptual framework that was deeply connected to the participant’s original verbatim in order to identify emergent themes (see Table 3 ).

Major themes and subthemes that emerged from the interviews indicating participants’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

After identifying the emerging themes, the transcripts were read again so as to cluster these emergent themes together according to their similarities at the basic level. In this process, some themes emerged as the broad themes under which subthemes were incorporated. The major themes and subthemes that emerged in the analysis are presented in Table 3 .

Table 3 presents six major themes describing the experiences of participants with regard to the COVID-19 pandemic and their efforts to maintain a healthy lifestyle. The following section discusses each of these themes and its subthemes along with the relevant excerpts from participants’ experiences.

Psychological Health Issues

Almost every participant reported facing psychological health issues linked to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown. Participants experienced frustration, anxiety, fear, and stress. For example, participant 11 reported,

- “I am experiencing frustration daily for spending my 24 by 7 time at home, looking at same faces and am not allowed to go anywhere. Anxiety of work and its upcoming scenarios tickle my mind a lot. What if I have to do my job virtually for a lifetime? ………….Like that. And especially experiencing a fear of losing my ever charming personality, the economic status of family, no wages or less wages, fewer opportunities in future, job shift, health care of my family.”

The closure due to the pandemic has created a state of uncertainty about an individual’s own future as well as about the future of the family and community, which in turn is being reflected in terms of psychological states of frustration, anxiety, fear, and stress.

Individuals stuck at their homes without a clearly defined routine and work are not able to prioritize their work schedules, resulting in the experience of unexplained laziness and fatigue. Participant 7, for example, reports that

- “Physical fatigue has reduced as there is no physical load or fixed working hours, but the mental fatigue and mental pressure has increased manifolds. Worries have increased. Spare time is more than what was required and due to this lethargy has increased. Frustration level is going up.”

The monotonous and closed life cycle of one confined to one’s own home has also resulted in extreme disturbances of one’s sleep cycle. For example, Participant 5 reports,

- “Sleep a lot, a lot!! Just imagine I have been sleeping 10 to 12 hours after the lockdown. My sleep pattern was set earlier due to office, but it is disturbed now in the absence of a routine. I have virtual meetings now also, but if the meeting is to start at 10, I would get up at 9.40, wash my face and attend the meeting. After that I feel like taking a nap again. I sleep for 8 hours wake up and exercise in the morning, but I have the liberty to be flexible with my time. seriously I am craving for gyms to open, my trainer to keep a check on me, scold me, I really want complete sleep and a routine.”

It is therefore evident from these examples that the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in the experience of psychological problems characterized by frustration, anxiety, fear, and stress. The sleep–wake cycle is interrupted, leading to a state of laziness and mental fatigue.

Lack of Motivation for Fitness

The closure of gyms and other fitness activity centers, including sports stadiums, morning walk parks, etc., and the heightened psychological health issues have resulted in the lack of fitness motivation. For example, participant 1 reports,

- “See, ultimately due to the shutdown of gym during this pandemic, my rhythm has been disturbed, you are getting it? I have had a tight schedule always due to my profession but each evening I used to hit the gym daily…………. I mean, that zeal is gone, ……….now also I am getting time in the evening but then also I am unable to ask myself to work out because that gym environment is gone, the gym people as you would see other fellows at gym, that would motivate you, their body gives you an inspiration that how he or she is that fit, they motivate you, here I share an identity with them, I find those people as source of my motivation to physical exercise, those people give you so much morale and now that is lost totally, I literally crave for that.”

The motivation for fitness is not only internal but also external. People are motivated when they observe others doing fitness activities. Gym mates and their physique work as motivating factors for individuals to engage in a regular and routine gym activity. Participant 10 said in frustration that,

- “Almost all gone, ………….the motivation is the most ruined thing today, ……….talking about my workout, I have been hitting the gym since I was 22………, Imagine how much that space motivated me, I miss that, my pals there……., not because we are friends or something, see gym doesn’t provide you an environment to make pals or something as people change their gyms and many a thing but, they give you a lot of competition, you become jealous of their appearance and later that workout that space becomes your habit, I miss that, say like anything, but still I am trying.”

It is evident from the above statement that a lack of motivation for fitness was due to the home confinement and lack of presence of others. The presence of others engaged in a similar activity not only creates a sense of shared identity but also is a source of healthy competition and thus motivation.

Change of Perception

As the days progressed, individuals learned to respond to the pandemic in a more constructive and positive manner. Their perception for the situation remained the same (negative), but their perception toward themselves started to change. They started believing that even though they could not change the situation, they could do the same for their own self to deal with the situation. Participant 2, for example, commented on the situation and said,

- “Ah! Talking about the situation we are living in, it is so unprecedented, anything can happen anytime, though I am less stressed as compared to the date the lockdown was announced, I perceive this whole situation is so terrible, worst… what is this happening, you just tell me, wake up in fear and sleep in fear. I wonder when this is going to end.”

However, upon asking about her/his own self, s/he added

- “You know this COVID has done only one thing right, that is, you know giving me immense time to work on myself, which otherwise I always overlooked. Though I went to gym for my physique only but never gave time to my thoughts, skills, etc. So when talking about changes in myself or perception of self, I would say changes come under three categories in me- first physical, that is appearance, personal, like I will quote enjoying every bit of time. Who knows I am next. I now celebrate life, and finally social changes in myself, as I have got time to work on my communication skills, talking on virtual platforms and sense of oneness or say unity, as I am locked down in hostel and we guys do every deed and task on our own without family, standing together.”

Similarly participant 22 summarized the situation as

- “(Laughing), Seriously! The Virus is making a joke on us, truly this is the worst of situations I can ever imagine, I am so negative about the situation we are in, I am in… everyone in….you know how stressful it is for me to know that I am unable to practise. You know as a clinician how hard it is to be like this. Though I am still a student but think likewise, harsh situation madam, extra precautions for everything, negative, too much negative. This time would be a memorable time for generations; sorry my tone has become louder I am kind of in agony, all credits to this so called CORONA.”

S/he, however, further commented that

- “my experience throughout the past few months in this Corona Era is so negative but myself-perception or I would say how I am taking myself now from earlier has meaningfully changed now. You know, I am someone who is giving time to myself, exploring my hobbies, giving time to leisure, learning kitchen skills, learning new dishes, becoming a chef besides being a dentist you know. So, for me, myself, I am so positive with regards to myself.”

It is therefore evident that increased experiences with an initial unfamiliar situation initiate the coping mechanisms within an individual, which is reflected in the changed perception of their own self, and reappraisal of the situation in a more positive manner.

Shifting Focus on Substitutes of Gym Workout and Equipment

With the positive change in perception, individuals started to think about their normal routine and tried to find ways to substitute their normal activities. They started trying to shift their exercises from gym to other available places and using alternatives to gym equipment for their fitness activities. The statement of participant 20 indicated how shifting from gym-based exercises to yoga practices was an effective alternative for coping with the habitual compulsion for gym exercises.

- “Since I get a pace back again for my physical fitness in this lockdown, I have made a shift to yoga, especially the power yoga in the morning time. I prefer doing meditation as well. Earlier I never used to practise the same but now I have seen videos of some asanas good for health, I am following them and practising them. It’s a shift for peace I guess. I tried something new and found my gym addiction could be controlled or moderated by taking out time for yoga and meditation even after COVID.”

Similarly, participant 17 reported her/his shift to high-intensity workouts at home.

- “See, as you might know not everyone has exercise equipment at home which we used to have in gym. So, I prefer those exercises which require less or zero weights say jumping jacks, skipping.”

After resuming motivation, in order to stay physically active and fit, participants actively engaged in the process of finding alternatives to their routine physical exercise equipment. Participant 14 reported shifting to alternatives to heavy weights

- “I personally was too much dependent on equipment to exercise in the gym. Now there is no option left because even online, the 5 and 10 kg weights are out of stock, And, nearby stores are either closed or you can’t go out. So, for me it was tough but I searched the internet, the social media, talked to fitness experts and used some ‘JUGAAD’ at home. So, they are using buckets, big water bottles and skipping ropes. I had 10 kg iron rods of water pipeline spare at my home, I am using that and these are helpful and I guess need of the hour.”

Social Media Dependence

One of the major shifts in the individuals’ lives during this pandemic was the increased social media dependence. As a result of social distancing, people were spending more time online to virtually connect with others and stream entertainment. In the backdrop, the COVID-19 pandemic led to an increase in the time spent on social media that helped people kill time. Participant 12 reported the benefits as well as the drawbacks of this social media dependence.

- “Social-media is a mixed feeling platform. I mean at one hand it keeps me updated with the happening around; the facilities promised by the government; and… it keeps me connected with the world. But on the other, it irritates me a lot, a lot of misinformation creates a worry in you. So yes, there is a dual objective of this social media.”

However, participant 4 viewed this increased dependence on social media as an effective strategy to break the silence and to overcome the monotonous days.

- “Our life has given us so much time ……., I mean I have so much spare time but besides that, I have a monotonous schedule every day, so social media keeps me busy, for example, web series suggestion and reviews, movies suggestion and reviews, video games, etc. Also, on the one hand, I do not get bored as one day I am learning some planting technique at home through media, the other day something to cook, some family or friend sharing his/her recipe, hobby ideas, craft ideas, writing, etc. Physical workout schedule helps me a lot. I am doing one thing useful at a time, and that keeps me busy.”

Similarly, participant 3 reported that

- “Definitely social media has impacted my sitting schedule as I am just sitting for a long span of time, say while eating or talking to family. I am sitting scrolling YouTube, Facebook, WhatsApp, Instagram, one post after the other. It has become my habit now. I feel like I will only watch a single video or only this news but I end up spending 1 to 2 hours scrolling and watching. Seriously, it’s a habit now, but I am glad that workout is something I do in my schedule, which is so productive, and I really feel good about myself because of the physical fitness.”

However, participant 21 pointed out the experience of lack of emotional attachment, sympathy, and support resulting from the content consistently served by social media.

- “Social media is full of content which reveal crime stories, life matters, relationships, suicides, etc. at a large scale. So many movie clips, videos, web series show a lot of crime, aggression or say anything on that. So, I feel now-a-days emotionally detached to any relationship, friendship or even to my family. If I receive their call, I would say yes okay fine, no further interest in how they are dealing or what they are experiencing. And if they ask I would say, so what, I am not a kid anymore. I lead my life you lead yours, definitely social media is making me someone I never used to be. In fact, my sister has become the same, though she is living with the family under the same roof. Earlier I was so sensitive to any suicide or crime. If I heard of that I would cry or be sad. I used to feel the pain of the victim. Now, I hear a story for real and I am like, yeah part of life, or you pay for deeds like that. No sympathy left I guess, so detached.”

However, what was more important was that social media was seen to be helping individuals in maintaining their daily fitness routines by providing them alternative fitness tools and techniques, the virtual company of other fitness freaks, and by helping them back, influencing others and getting influenced by others. Participant 6 reported that

- “Social media has lots of side effects, but a good effect of it now-a-days for a gym freak like me is that social media provides videos of trainers, and other freaks working out at home or hostels. I can know now virtually how to maintain a schedule. They are sharing their experience, they are influencing me a lot, I am trying my best, and workout is helping me a lot.”

Favorable Attitude Toward Music as a Tool

Many participants also reported the use of music as an aid while exercising. Participant 7 reported that

- “I have two schedules of exercise. If working out in the morning, I prefer soothing music, like that of birds chirping, or instrumental jazz. And if I am exercising in evening, I want to listen to EDM, that is electronic dance music, I have made a playlist of computerised music and listen to that in evening. I prefer music because it takes you to another world, which is needed the most now (exclaimed!) It creates an environment like that of a gym in my head, or say, I imagine I am in the gym, as I cut off all the surrounding voices.”

Similarly, participant 9 reported that

- “I just love to have old-country music while I am exercising. It is a kind of genre of songs, the old country one, and sometimes I love random numbers of songs. It is needed because you can say it lets me focus, helps me to calm down. Also, when I am locked at home, it actually provides me a world free of distractions, just my own world, where there is no corona. Music is ultimate fun. If there is no music available I will not workout, because workout makes me happy and I really want to exercise effectively and enjoy it too.”

It is, therefore, evident that music is an important supporting tool that helps individuals relax and enjoy their original routine even when they are working out at home. Music is a powerful tool that recreates the same environment that participants used to have during their gym exercise times.

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought major upheaval in the life of every individual across the globe. It has hampered the day-to-day activities of almost all individuals including those who depend on gyms for their physical fitness routine. The present study was conducted with individuals for whom going to the gym was a routine activity so as to explore their experiences in terms of their perceptions of the pandemic situation and their ways of coping with COVID-19-induced uncertainties and health issues.

The findings of this study not only are consistent with a range of studies that have reported psychological health issues due to the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown ( Hawryluck et al., 2004 ; Ammar et al., 2020a , b , c , d ; Chtourou et al., 2020 ; de Oliveira Neto et al., 2020 ; Shigemura et al., 2020 ; Varshney et al., 2020 ) but also go beyond those to suggest that, with time, individuals learn to adopt to situations in healthy and positive ways. Participants reported experiencing a significant change in their sleeping pattern, unexplained laziness, and mental fatigue, and having a general feeling of fear, anxiety, stress, and frustration due to home confinement, which impacted their motivation to find alternate ways to continue fitness exercises.

Other factors found responsible for the lack of fitness motivation were the absence of gym partners and the lack of gym environment, which were also considered as potential sources of gym motivation in earlier studies ( Sonstroem and Morgan, 1989 ; Sonstroem and Harlow, 1994 ; McAuley et al., 2000 ; Fox, 2003 ; Tamur, 2014 ). It is important to note that, being a social entity, people like the company of others and feel connected to each other. This feeling of connectedness is found to be associated with various psychological constructs such as persistence, motivation, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and physical as well as psychological health ( Scully et al., 1998 ; Proctor et al., 2011 ; Haslam et al., 2015 ; Begun et al., 2018 ). The absence of this feeling of connectedness that people were used to experiencing in a gym environment probably was one of the reasons for the lack of motivation for home exercise.

The findings of the study also indicated that although the participants’ perception of the pandemic situation was negative initially, their self-perception gradually improved toward a positive one, as they realized that they had enough time to look after themselves. Rauthmann et al. (2015) reported that environment and behavior, if different from the usual, lead to a negative situational perception. However, with an increase in time available to devote to oneself, perceptions change in a positive direction ( Karagiannidis et al., 2015 ). Such a change in perception is likely to promote the process of self-approval and find effective ways to deal with the current situation.

In the present study, a shift from the gym workout and fitness equipment toward substitutes is clearly visible during the latter part of the lockdown. After the initial confusion and passive wait for things to normalize, participants accepted the reality and started thinking about alternatives to exercises related to heavy gym equipment. Some of the alternatives listed by them included switching to yoga and meditation ( National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health, 2020 ), high-intensity workout at home, and lifting heavy buckets, big water bottles, and skipping. All these alternative arrangements not only helped individuals maintain their daily exercise routine but also contributed to their physical and mental health ( Jiménez-Pavón et al., 2020 ; Nicol et al., 2020 ). In fact, the American College of Sports Medicine had recommended 150–300 min of aerobic exercise per week and two sessions per week of moderate-intensity muscle strength exercises for people to be physically active during the COVID-19 pandemic ( Joy, 2020 ).

The mixed impact of social media usage and listening to music during exercise was also observed in this study. Results clearly indicate that participants found social media to be an effective medium to keep themselves up to date about the pandemic situation and to overcome the monotony of home confinement. Apart from this, participants also experienced a lack of emotional attachment, as face-to-face interaction during the said period was missing. This encouraged participants to use social media to get connected to people as well as to witness their regular activities, which they were missing otherwise. Several studies in the past have argued that social support boosts motivation for training and can increase up to 35% more adherence to a physical exercise program ( Rhodes et al., 2001 ) and that it can be an additional strategy to make exercise events more interactive and less dissociated from afferent body responses (heart rate, breathing), which in turn results in more positive training experience ( Kravitz and Furst, 1991 ; Pridgeon and Grogan, 2012 ).

Social media was also used as a platform to know about virtual fitness techniques and opportunities for online training for physical exercise. Ammar et al. (2020d) demonstrated 15% higher use of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) during the COVID-19 confinement duration, which indicates higher use of social media and app use for home-based fitness activities ( Tate et al., 2015 ; Ammar et al., 2020a ).

Furthermore, participants also found that listening to music was an effective aid to keep themselves engaged as they exercised. This also supports the finding that music helps people to continue their fitness workout for a significantly longer period of time ( Thakare et al., 2017 ). A series of studies have shown that music creates an ergogenic effect during physical and cognitive performance and is linked to heightened motivation and engagement and lower levels of stress, anxiety, and depression ( Chtourou et al., 2015 ). In their recent meta-analytic review Terry et al. (2020) have concluded that listening to music during physical activity boosts positive affective valence and results in improved physical engagement and enhanced physiological responses. It is therefore clearly evident that listening to music while doing physical exercise during the current pandemic has enabled people to focus on the exercise without any distraction from the home setting and has enabled them to create their own world, where there is no COVID-19.

To conclude, the findings of the study indicate that the perceptions and social media habits of fitness freaks, who were hitting gyms for a regular workout before the lockdown, were greatly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic. They also experienced psychological health issues during the initial phase of the pandemic. However, they gradually changed their dependence on gym-based workout and switched to alternative exercises that helped them greatly to restore their mental and physical health.

Implications and Future Suggestions

The present study shows that despite the initial experience of anxiety and fear and the lack of motivation to engage in physical exercise at home, fitness freaks were able to shift to home exercises and were greatly supported by social media uses and listening to music. One could argue that this study only included fitness freaks who find it difficult to detach themselves from physical activities for a long time, and this was probably the reason for their shift to home-based exercises. However, there is no doubt that the findings of this study have demonstrated that if performed regularly, physical exercise has the potential to mitigate the ill physical as well as psychological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of this study, therefore, could be extended to the common public to also persuade them to engage in physical fitness exercises, which would result not only in a better physical health but also in an enhanced psychological health and well-being. The findings of this study strengthen the recommendations made by researchers and organizations (for details see Chtourou et al., 2020 ; World Health Organization [WHO], 2020 ) to engage in home-based exercises (including, but not limited to, aerobic activities, balance and flexibility exercises, and muscular strength and endurance training) for about 150–180 min per week; to use social media, music, and/or similar techniques to increase adherence to physical exercises; and to practice dancing and yoga to reduce stress, anxiety, and depression, and even improve the quality of sleep ( Chennaoui et al., 2015 ; Chtourou et al., 2015 ). It is also noted that one should start physical exercise and its alternatives in a progressive manner and must adhere to his/her fitness levels for choosing the amount and intensity of these exercises.

Data Availability Statement

Ethics statement.

All procedures followed in this study were in accordance with the APA’s ethical standards and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

HK, TS, and YA conceptualized the study. HK and TS prepared study protocols. HK collected data, conducted initial data analysis, and wrote the first draft. TS, SM, and YA finalized data analysis, reviewed, and commented on the draft manuscript. HK, TS, SM, and YA contributed to the preparation of the final draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Ammar A., Brach M., Trabelsi K., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L. (2020a). Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey. Nutrients 12 : 1583 . 10.3390/nu12061583 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ammar A., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Trabelsi K., Masmoudi L., Brach M., et al. (2020b). COVID-19 Home Confinement Negatively Impacts Social Participation and Life Satisfaction: A Worldwide Multicenter Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 17 : 6237 . 10.3390/ijerph17176237 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ammar A., Trabelsi K., Brach M., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L., et al. (2020c). Effects of home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: Insight from the “ECLB-COVID19” multi countries survey. medRxiv Preprint [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ammar A., Trabelsi K., Brach M., Chtourou H., Boukhris O., Masmoudi L., et al. (2020d). Effects of home confinement on mental health and lifestyle behaviours during the COVID-19 outbreak: Insight from the ECLB-COVID19 multicenter study. Biol. Sport 38 9–21. 10.5114/biolsport.2020.96857 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bavel J. J. V., Baicker K., Boggio P. S., Capraro V., Cichocka A., Cikara M., et al. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4 460–471. 10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Begun S., Bender K. A., Brown S. M., Barman-Adhikari A., Ferguson K. (2018). Social Connectedness, Self-Efficacy, and Mental Health Outcomes Among Homeless Youth: Prioritizing Approaches to Service Provision in a Time of Limited Agency Resources. Youth Soc. 50 989–1014. 10.1177/0044118X16650459 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bentlage E., Ammar A., How D., Ahmed M., Trabelsi K., Chtourou H., et al. (2020). Practical Recommendations for Maintaining Active Lifestyle during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Literature Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health 17 : 6265 . 10.3390/ijerph17176265 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen P., Mao L., Nassis G. P., Harmer P., Ainsworth B. E., Li F. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions. J. Sport Health Sci. 2020 : 103 . 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.02.001 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chennaoui M., Arnal P. J., Sauvet F., Leger D. (2015). Sleep and Exercise: A Reciprocal Issue? Sleep Med. Rev. 20 59–72. 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.008 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chtourou H., Briki W., Aloui A., Driss T., Souissi N., Chaouachi A. (2015). Relation entre musique et performance sportive: vers une perspective complexe et dynamique. Sci. Sports 30 119–125. 10.1016/j.scispo.2014.11.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chtourou H., Trabelsi K., H’mida C., Boukhris O., Glenn J. M., Brach M., et al. (2020). Staying Physically Active During the Quarantine and Self-Isolation Period for Controlling and Mitigating the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Overview of the Literature. Front. Psychol. 11 : 1708 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01708 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- de Oliveira Neto L., Elsangedy H. M., de Oliveira Tavares V. D., La, ScalaTeixeira C. V., Behm D. G., et al. (2020). TrainingInHome - Home-based training during COVID-19 (SARS-COV2) pandemic: physical exercise and behavior-based approach. RevistaBrasileira de Fisiologia Do Exercicio 19 S9–S19. 10.33233/rbfe.v19i2.4006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fox K. R. (2003). “ The effects of exercise on self-perceptions and self-esteem ,” in Physical activity and psychological wellbeing , eds Biddle S. J. H., Fox K. R., Boutcher S. H. (London: Routhledge), 88–118. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jurak G., Morrison S. A., Leskošek B., Kovač M., Hadžić V., Vodičar J., et al. (2020). Physical activity recommendations during the coronavirus disease-2019 virus outbreak. J. Sport Health Sci. 9 325–327. 10.1016/j.jshs.2020.05.003 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haslam C., Cruwys T., Halsam A., Jetten J. (2015). Social connectedness and health. Encycl. Geropsychol. 2015 2174–82. 10.1007/978-981-287-080-3_46-1 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hawryluck L., Gold W. L., Robinson S., Pogorski S., Galea S., Styra R. (2004). SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerging Infect. Dis. 10 1206–1212. 10.3201/eid1007.030703 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jiménez-Pavón D., Carbonell-Baeza A., Lavie C. J. (2020). Physical exercise as therapy to fight against the mental and physical consequences of COVID-19 quarantine: special focus in older people. ProgCardiovasc. Dis. 24 386–388. 10.1016/j.pcad.2020.03.009 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Joy L. (2020). Staying Active During COVID-19. Available online at: https://www.exerciseismedicine.org/support_page.php/stories/?b=892 , (March 17, 2020) [ Google Scholar ]

- Karagiannidis Y., Barkoukis V., Gourgoulis V., Kosta G., Antoniou P. (2015). The Role Of Motivation And Metacognition On The Development Of Cognitive And Affective Responses In Physical Education Les-Sons: A Self Determination Approach. Rev. J. Motric. 11 135–150. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kravitz L., Furst D. (1991). Influence of reward and social support on exercise adherence in aerobic dance classes. Psychol. Rep. 8 423–426. 10.2466/pr0.69.6.423-426 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lavie C. J., Ozemek C., Carbone S., Katzmarzyk P. T., Blair S. N. (2019). Sedentary Behavior, Exercise, and Cardiovascular Health. Circ. Res. 124 799–815. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312669 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehnert K., Sudeck G., Conzelmann A. (2012). Subjective Well Being And Exercise In The Second Half Of Life: A Critical Review Of Theoretical Approaches. Eur. Rev. Aging Phys. Activ. 9 87–102. 10.1007/s11556-012-0095-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mazyarkin Z., Peleg T., Golani I., Sharony L., Kremer I., Shamir A. (2019). Health benefits of a physical exercise program for inpatients with mental health; a pilot study. J. Psychiatr. Res. 113 10–16. 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.03.002 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- McAuley E., Blissmer B., Katula J., Duncan T. E., Mihalko S. L. (2000). Physical Activity, Self Esteem And Self-Efficacy Relationships In Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anna. Behav. Med. 22 : 131 . 10.1007/bf02895777 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2020). Yoga: what you need to know. Available onlline at: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/yoga/introduction.htm (accessed Feb 01, 2020). [ Google Scholar ]

- Nicol G. E., Piccirillo J. F., Mulsant B. H., Lenze E. J. (2020). Action at a distance: geriatric research during a pandemic. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 68 922–925. 10.1111/jgs.16443 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Owen N., Sparling P. B., Healy G. N., Dunstan D. W., Matthews C. E. (2010). Sedentary behavior: emerging evidence for a new health risk. Mayo Clin. Proc. 85 1138–1141. 10.4065/mcp.2010.0444 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pridgeon L., Grogan S. (2012). Understanding exercise adherence and dropout: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of men and women’s accounts of gym attendance and non-attendance. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Heal 4 382–399. 10.1080/2159676x.2012.712984 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Proctor C., Tsukayama E., Wood A. M., Maltby J., Fox J., Linley P. A. (2011). Strengths Gym: The impact of a character strengths-based intervention on the life satisfaction and well-being of adolescents. J. Posit. Psychol. 6 377–388. 10.1080/17439760.2011.594079 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rauthmann J., Sherman R. A., Funder D. C. (2015). Principles of Situation Research: Towards a Better Understanding of Psychological Situations. Eur. J. Pers. 29 363–381. 10.1002/per.1994 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rhodes R. E., Martin A. D., Taunton J. E. (2001). Temporal relationships of self-efficacy and social support as predictors of adherence in a 6-month strength-training program for older women. Perc. Mot. Skills 93 693–703. 10.2466/pms.2001.93.3.693 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Scully D., Meade M. M., Graham R., Dudgeon K. (1998). Physical exercise and psychological well-being : a critical review. Br. J. Sports Med. 32 111–120. 10.1136/bjsm.32.2.111 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shigemura J., Ursano R. J., Morganstein J. C., Kurosawa M., Benedek D. M. (2020). Public responses to the novel 2019 coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Japan: Mental health consequences and target populations. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 74 281–282. 10.1111/pcn.12988 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sonstroem R. J., Harlow L. L. (1994). Exercise And Self-Esteem: Validity Of Model Expansion And Exercise Associations. J. Sport Exer. Psychol. 16 229–242. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sonstroem R. J., Morgan W. P. (1989). Exercise And Self-Esteem: Rationale And Model. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 21 329–37. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stathi A., Fox K. R., McKenna J. (2002). Physical Activity and Dimensions Of Subjective Well-Being In Older Adults. J. Aging Phys. Activ. 10 76–92. 10.1123/japa.10.1.76 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tamur S. (2014). RelationshpsBetween Exercise Behavior, Self- Efficacy and Affect. Ph. D thesis, Colorado: University of Boulder, Spring. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tate D. F., Lyons E. J., Valle C. G. (2015). High-tech tools for exercise motivation: use and role of technologies such as the internet, mobile applications, social media, and video games. Diabetes Spectr. 28 45–54. 10.2337/diaspect.28.1.45 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Terry P. C., Karageorghis C. I., Curran M. L., Martin O. V., Parsons-Smith R. L. (2020). Effects of music in exercise and sport: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 146 : 91 . 10.1037/bul0000216 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thakare A. E., Mehrotra R., Singh A. (2017). Effect of music tempo on exercise performance and heart rate among young adults. Int. J. Physiol. Pathophysiol. Pharmacol. 9 35–39. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Varshney M., Parel J. T., Raizada N., Sarin S. K. (2020). Initial Psychological Impact of COVID-19 and its Correlates in Indian Community: An online (FEEL-COVID) survey. PLoS One 15 : e0233874 . 10.1371/journal.pone.0233874 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization [WHO] (2020). Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) advice for the public. Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public , (accessed Jan, 30 2020). [ Google Scholar ]

- Xiao H., Zhang Y., Kong D., Li S., Yang N. (2020). Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 days during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in January 2020 in China. Med. Sci. Monit. 26 : e923921 . 10.12659/MSM.923921 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yan Z., Spaulding H. R. (2020). Extracellular superoxide dismutase, a molecular transducer of health benefits of exercise. Redox Biol. 32 : 101508 . 10.1016/j.redox.2020.101508 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

How the Pandemic Is Changing Our Exercise Habits

Many of us have been moving less since the pandemic began. But some, including many older men and women, seem to be moving more.

By Gretchen Reynolds

Are you exercising more or less since the coronavirus pandemic began?

According to a new study that focused on physical activity in the United Kingdom , most of us — not surprisingly — have been less physically active since the pandemic and its waves of lockdowns and quarantines began. Some people, however, seem to be exercising as much or more than before, and surprisingly, a hefty percentage of those extra-active people are older than 65. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed, but they add to a mounting body of evidence from around the globe that the coronavirus is remaking how we move, although not necessarily in the ways we may have anticipated.

The pandemic lockdowns and other containment measures during the past six months and counting have altered almost every aspect of our lives, affecting our work, family, education, moods, expectations, social interactions and health.

None of us should be surprised, then, to learn that the pandemic seems also to be transforming whether, when and how we exercise. The nature of those changes, though, remains rather muddled and mutable, according to a number of recent studies. In one, researchers report that during the first few weeks after pandemic-related lockdowns began in the United States and other nations, Google searches related to the word “exercise” spiked and remained elevated for months.

And many people seem to have been using the information they gleaned from those searches by actually exercising more. An online survey conducted in 139 countries by RunRepeat, a company that reviews running shoes, found that a majority of people who had been exercising before the health crisis began reported exercising more often in the early weeks after. A separate survey of almost 1,500 older Japanese adults found that most said they had been quite inactive in the early weeks of lockdowns, but by June, they were walking and exercising as much as ever.

A gloomier June study, however, using anonymized data from more than 450,000 users of a smartphone step-counting app, concluded that, around the world, steps declined substantially after lockdowns began. Average daily steps declined by about 5.5 percent during the first 10 days of a nation’s pandemic lockdowns and by about 27 percent by the end of the first month.

But most of these studies and surveys relied on people recalling their exercise habits, which can be unreliable, or looked at aggregate results, without digging into differences by age, socioeconomic group, gender and other factors, which might turn up telling variations in how people’s exercise habits might have changed during the pandemic.

So, for the new study, which has been posted at a biology preprint site awaiting peer-review, researchers at University College London turned to data from a free, activity-tracking smartphone app available in the United Kingdom and some other nations. The app uses GPS and similar technologies to track how many minutes people had spent walking, running or cycling, and allows users to accumulate exercise points that can be used for monetary or other rewards. (One of the study’s authors works for the app maker but the company did not provide input into the results or analysis of the research, according to the study’s other authors.)

The researchers gathered anonymized data from 5,395 app users living in the United Kingdom who ranged in age from adolescent to older adults. All of them had been using the app since at least January 2020, before the pandemic had spread to that country.

The researchers used data from the app on users’ birth dates and ZIP codes to divide people by age and locale to learn how much they exercised in January. Then they began comparing, first to the early days of social-distancing restrictions in various parts of the United Kingdom, then to the stricter lockdowns that followed and finally, to the dates in midsummer when most lockdowns in that country eased.

They found, unsurprisingly, that almost everyone’s exercise habits changed when the pandemic started. An overwhelming majority worked out less, especially once full lockdowns began — regardless of their gender or socioeconomic status. The drop was most marked among those people who had been the most active before the pandemic and among people under the age of about 40 (who were not always the same people).

After lockdowns lifted or eased, most people began exercising a bit more often, but, in general, only those older than 65 returned to or exceeded their previous minutes of exercise.

The results are surprising, says Abi Fisher, an associate professor of physical activity and health at University College London, who oversaw the new study, “especially because 50 percent of the older group were 70 or older.”

Of course, these older people, like the other men and women in the study, downloaded and used an exercise app, which distinguishes them from a vast majority of people around the world who do not use such apps. The study also looked only at “formal” exercises like walking, running or cycling and not lighter activities like strolling or gardening, which can likewise benefit health and most likely also changed during the pandemic.

And the study tells us nothing about why exercise habits differed for people during the pandemic, although some mixture of circumstance and psychology may very likely be a factor. Older people probably had more free time for exercise than younger adults who are juggling child care, work and other responsibilities during the pandemic, Dr. Fisher says. They also might have developed greater concerns about their immune systems and general health, motivating them to get up and move.

Far more large-scale and long-term research about exercise during the pandemic is needed, she said. But for now, the message of the available research seems to be that we may all want to monitor how much we are moving to help assure that we are exercising enough.

“While it is no surprise that the lockdowns disrupted people’s exercise patterns,” Dr. Fisher said, “we cannot just assume everyone will bounce back once restrictions are lifted. We need to help people to get back to doing regular exercise, within the limits of ongoing pandemic restrictions, of course.”

How to Make Your Smartphone Better

The process of backing up your smartphone has become so simplified that it takes just a few screen taps to keep copies of your photos, videos, and other files stashed securely in case of an emergency.

These days, smartphones include tools to help you more easily connect with the people you want to contact — and avoid those you don’t. Here are some tips .

Trying to spend less time on your phone? The “Do Not Disturb” mode can help you set boundaries and signal that it may take you a while to respond .

To comply with recent European regulations, Apple will make a switch to USB-C charging for its iPhones. Here is how to navigate the change .

Photo apps have been using A.I. for years to give you control over the look of your images. Here’s how to take advantage of that .

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The health benefit of physical exercise on COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from mainland China

Roles Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft

Affiliation School of Economics and Management, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Roles Data curation, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation International College of Football, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

Roles Software, Validation, Visualization

Roles Methodology, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

- Ruofei Lin,

- Xiaoli Hu,

- Lige Guo,

- Junpei Huang

- Published: October 12, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275425

- Reader Comments

Our study aims to investigate the health benefit of regular physical exercise participation on a series of COVID-19 outcomes including COVID-19 morbidity, mortality, and cure rate.

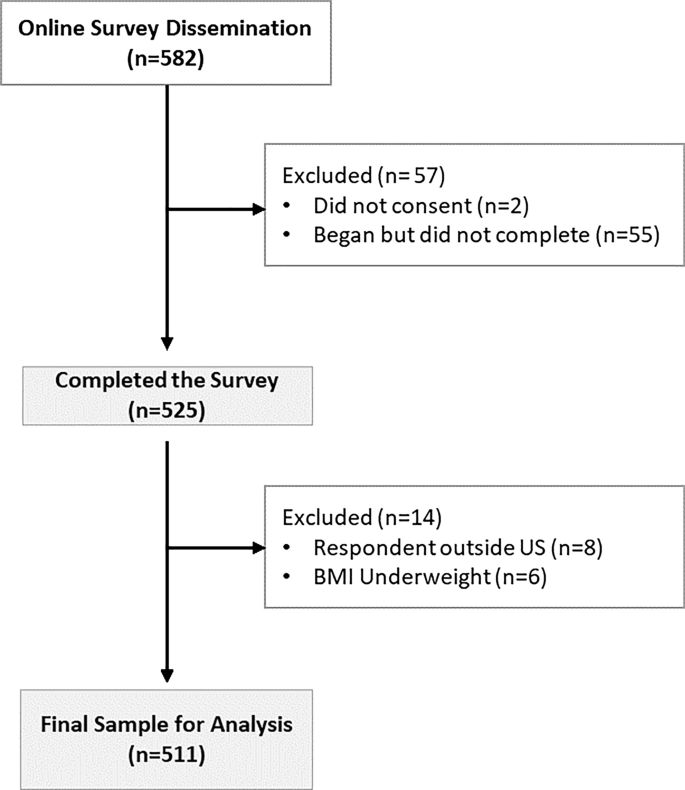

Prefecture-level panel data related to physical exercise and the COVID-19 pandemic in China were collected from January 1 to March 17, 2020, (N = 21379). Multiple linear regression was conducted, and the ordinary least squares technique was used to estimate the coefficient.

It was shown that regular sports participation significantly negatively affected COVID-19 morbidity (estimate = -1.1061, p<0.01) and mortality (estimate = -0.3836, p<0.01), and positively affected cure rate (estimate = 0.0448, p<0.01), implying that engaging in physical exercise regularly does have a significant positive effect on COVID-19 outcomes. Then, we explored the heterogeneity of the effect of physical exercise on areas with different risk levels and it was revealed that the effect of physical exercise was more pronounced in high-risk areas in terms of morbidity (estimate = -1.8776, p<0.01 in high-risk areas; estimate = -0.0037, p<0.01 in low-risk areas), mortality (estimate = -0.3982, p<0.01 in high-risk areas; estimate = -0.3492, p<0.01 in low-risk areas), and cure rate (estimate = 0.0807, p<0.01 in high-risk areas; 0.0193 = -0.0037, p<0.05 in low-risk areas).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that regularly engaging in physical exercise before the pandemic has positive health effects, especially in the case of a more severe epidemic. Therefore, we urge readers to actively engage in physical exercise so that we can reduce the risks in the event of a pandemic.

Citation: Lin R, Hu X, Guo L, Huang J (2022) The health benefit of physical exercise on COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from mainland China. PLoS ONE 17(10): e0275425. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275425

Editor: Zulkarnain Jaafar, Universiti Malaya, MALAYSIA

Received: May 2, 2022; Accepted: September 18, 2022; Published: October 12, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Lin et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting information files.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1 Introduction

As an ongoing pandemic, the COVID-19 pandemic has so far infected 500 million people and killed more than 6 million people worldwide. On January 30, 2020, it was declared global health emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO), and then a global pandemic on March 11, 2020 [ 1 ]. The COVID-19 pandemic has posed huge challenges to economic and social development and people’s daily life around the world. A large number of medical resources are currently occupied, and the lack of such resources has led to excess mortality [ 2 , 3 ]. In addition, public health measures such as quarantine and isolation, work at home, and school closure, have seriously affected normal social order and economic production, brought huge economic losses [ 4 ], and also have caused a negative impact on the quality of life and physical and mental health of populations worldwide [ 5 ]. Therefore, intervention measures should be taken to curb the outbreak as much as possible and minimize the adverse consequences of the epidemic.

Despite a range of outbreak mitigation strategies aimed at social distancing in most countries, practices that have been effective in preventing most citizens from becoming infected during the pandemic, such strategies have paradoxically left people with no immunity to the virus and therefore vulnerable to additional waves of infection [ 6 ]. In addition, these public health policies have led to the closure of public places such as parks and gyms, resulting in an increase in sedentary behavior and a decrease in physical exercise (PEx) among individuals, which has also adversely impacted people’s immunity. It is believed that the world will not be able to return to pre-pandemic normalcy until safe and effective vaccines are available and global vaccination programs are successfully implemented [ 7 ]. Therefore, countries around the world have been actively developing and promoting COVID-19 vaccines since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. As of April 26, 2022, a cumulative total of 11.55 billion doses of the COVID-19 vaccine has been reported worldwide, with a vaccination rate of 65.16% [ 8 ]. In China, as of April 29, 2022, there have been a cumulative total of 334,308,000 doses administered, with a vaccination rate of 88.64%.

However, despite the proven effectiveness of the vaccine in preventing infection and avoiding critical conditions [ 9 , 10 ], it has become evident that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can mutate very rapidly [ 11 , 12 ] with strong antibody evasion [ 13 – 16 ]. Besides, there are still potential negative effects of vaccination [ 17 ], especially the prevalence of relatively low vaccination rates but high mortality rates in the elderly [ 18 ]. Therefore, at this stage, in addition to timely and effective pharmacological interventions, non-pharmacological interventions aimed at improving autoimmunity are also crucial. As an important part of a healthy lifestyle, it is of great theoretical and practical significance to explore the health benefits of physical exercise in the COVID-19 pandemic.

Physical exercise (PEx) is regarded as an important way to promote health, as well as prevent and protect the body from a variety of diseases [ 19 , 20 ], and it has been shown to have significant health benefits [ 21 ]. Likewise, it is an effective treatment for most chronic diseases and has direct, positive effects on both physical and mental health [ 22 ]. It is well documented that exercising regularly significantly improves the nervous system [ 23 ], bones and muscles [ 24 , 25 ], cardiovascular [ 26 ] and cardiopulmonary functions [ 27 ], and cognitive ability [ 28 ], and it has inhibitory effects on adverse health outcomes, including premature death [ 29 , 30 ], cardiovascular disease [ 30 , 31 ], hypertension [ 32 ], stroke [ 33 ], osteoporosis [ 34 ], type 2 diabetes [ 35 ], obesity [ 36 – 38 ], cancer [ 39 ], depression [ 40 – 42 ], anxiety [ 43 ] and other health outcomes. More importantly, physical exercise can strengthen the immune system [ 21 , 44 – 46 ], improve immune function, and reduce the risk, duration, or severity of viral infections [ 47 ]. Therefore, in theory, regular physical exercise can play an important role in strengthening the body’s immune system against COVID-19 [ 48 ], and individuals can maintain the requisite immunity to fight the novel infection COVID-19 through adhering to a healthy lifestyle [ 21 , 49 ].

This study aims to investigate the health benefit of physical exercise on COVID-19 morbidity, mortality, and cure rate. It contributes to the extensive literature on assessing the health benefits of physical exercise. A large body of literature has concluded that PEx has a positive influence on physical and mental health, with studies showing that moderate and regular physical exercise is important for preventing premature death [ 29 , 30 ], reducing obesity [ 36 – 38 ], avoiding chronic disease, such as cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases [ 32 ], as well as strengthening bones, muscles [ 25 ], and the immune system [ 44 – 46 ]. In addition, it can clear one’s mind and make one energetic [ 50 ], help relieve mental stress and reduce the incidence of psychological disorders, such as depression and anxiety [ 40 – 43 , 51 ]. In contrast to these articles, this paper focuses on the influence of physical exercise on the public health during the COVID-19 pandemic, and we selected COVID-19 morbidity, mortality, and cure rates as health outcomes of interest.

In addition, our research contributes to ongoing emerging literature related to factors that influence the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the COVID-19 outbreak, the factors influencing the COVID-19 pandemic have been well-discussed in a large number of articles, mainly focusing on pharmacological interventions [ 52 , 53 ], public health interventions [ 54 – 57 ], environmental variables [ 58 – 60 ], demographic characteristics [ 61 , 62 ], and healthcare resources [ 63 ]. In addition, the benefit of physical exercise (or physical activity) on physical and mental health during the pandemic has also been documented [ 22 , 64 – 71 ]. In contrast to those investigations, this paper focuses on the effect of engaging in physical exercise before the outbreak on a series of COVID-19 outcomes during the pandemic.

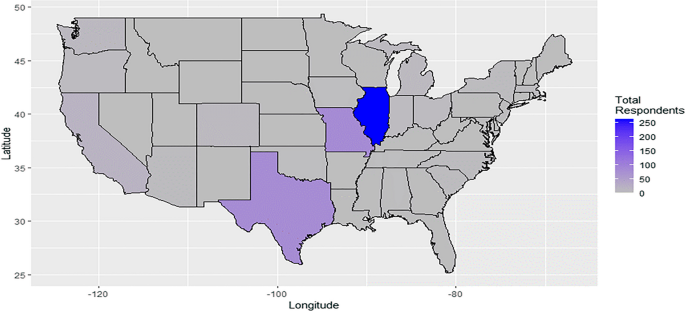

2.1 Study area

In this research, the study area was 279 prefecture-level Chinese cities. All of the provinces in mainland China were included in our analysis, which also included the great majority of prefectural cities. Cities in ethnic minority autonomous zones including Tibet, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and Southwest China were removed because of the significant amount of missing data, which was unreliable and unrepresentative. It is documented that more than 98% of China’s total population and more than 99% of its GDP were represented by the 279 metropolitan cities [ 72 ].

2.2 Data and variables

In this article, in order to empirically investigate the influence of physical exercise on COVID-19 morbidity, mortality and cure rates, prefectural data were collected daily from January 1, 2020 to March 17, 2020 in mainland China, N = 21379. Regarding epidemic-related data, the daily data of confirmed cases, death, and cure rates used to calculate morbidity, mortality, and cure rates were collected from official releases on the official websites of the national and provincial Health Committee. Regarding PEx-related data, the proportion of regular physical exercise participants was gathered by collecting data from provincially issued National Fitness Report, the National Fitness Development Survey Bulletin, and the National Fitness Action Program. GDP per capita, population density, and total number of publicly operated buses and taxis were obtained from the China Urban Statistical Yearbook. Applying big data mining technology, population migration data utilized to calculate effective distance were gathered from website of Baidu Migration ( http://qianxi.baidu.com/ ), and the search popularity of the term used to characterize residents’ awareness of prevention was obtained from the website of Baidu Index ( http://qianxi.baidu.com/ ). The original data for public health interventions were compiled from provincial and municipal emergency response headquarters for the prevention and control of COVID-19.

2.2.1 Dependent variable: COVID-19 outcomes.

2.2.2 Independent variable: Physical exercise participation.

Data on the proportion of regular physical exercise participants were collected from official bulletins in the National Fitness Report, the National Fitness Development Survey Bulletin, and the National Fitness Action Program released by each province, which refers to the proportion of residents aged 7 years and above who participate in physical exercise, moderate intensity or above, for at least 30-minute 3 times or more per week. According to the General Administration of Sport of China, moderate-intensity physical exercise refers to activities that require some exertion but still allow you to speak easily during the activity, such as fast walking, dancing, leisure swimming, playing tennis, and playing golf. Moderate exercise intensity is often represented by brisk walking, and the lower limit of moderate intensity is a medium speed (4km/h).

To comprehend the general situation of the physical fitness participation of urban and rural residents in China and to evaluate the implementation effect of the national fitness strategy, the General Administration of Sport of China regularly organizes the investigation of the national fitness and issues the National Fitness Investigation Bulletin. According to the guiding opinions stemming from the investigation, each provincial General Administration of Sport collects information including the number of people who participate in physical exercise once or more a week, the number of people who regularly participate in physical exercise, the venues and facilities, and the content and the duration of physical exercise of the permanent population of cities, counties, and districts using multistage stratified random sampling.

2.2.3 Control variables.

With respect to control variables, social and economic factors affected the development of the epidemic, among which population density [ 73 ], economic development [ 55 ], and traffic flow [ 74 ] were important influential factors. Therefore, in this paper, we selected urban population density, per capita GDP, and the total number of public-operated buses and taxis as control variables and introduced them into the model.

The epidemic risk perception of the public helped them to take personal precautions in time and reduce unnecessary contacts, thus reducing the possibility of being infected [ 75 , 76 ]. In this paper, we made use of the Baidu search index term "COVID-19" as the proxy variable of residents’ protection awareness. We converted the Baidu search index, a continuous variable, into a 0–1 dummy variable according to the mean value. If it was higher than the mean value, the value was 1, indicating high self-protection awareness of residents; otherwise, the value was 0.

In China, timely and strict public health interventions have played a crucial role in the mitigation of the COVID-19 outbreak. Referring to Huang et al. [ 77 ], we scored the public health measures implementation intensity of each city based on the epidemic prevention policy announcement issued by the health commission and converted it into a dummy variable according to the mean value. If the value was higher than the mean value, then the value was 1, indicating relatively strict prevention and control intensity; otherwise, the value was 0.

Studies have shown that population mobility does not mainly depend on the geographical distance between regions, but on the convenience of mobility, that is, the effective distance between regions [ 77 ]. Referring to Lin et al. [ 59 ], we calculated the effective distance to Wuhan, the city with the most severe epidemic in China. We retrieved the data from the Baidu migration website using big data technology.

2.3 Study design

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0275425.t001

3.1 Statistical description

A statistical description of the variables is shown in Table 1 .

3.2 Influence of PEx on COVID-19 outcomes