To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, measuring financial literacy: a literature review.

Managerial Finance

ISSN : 0307-4358

Article publication date: 21 September 2020

Issue publication date: 28 January 2021

The purpose of this paper is to review the main methods used in the literature to measure financial literacy (FL) of individuals.

Design/methodology/approach

The paper begins by describing how the different items used to measure the FL level of individuals are constructed. Then, it focuses on how do researchers select the items. Finally, it reviews the different calculation methods used in the literature to assess the FL level.

FL as a concept is tough to define and measure. Several studies focus on the definition and the measure of this concept. Different items are used in the literature and are mostly related to the study topics. The used calculation methods differ across the different studies.

Originality/value

This paper sheds light on the principal methodologies used in the literature to measure FL. It highlights the relationship between the items' content areas and the studies' subjects. Thus, this paper suggests guidance for future studies on measuring methods of FL.

- Financial literacy

- Objective measures

- Content areas

- Study topics

- Literature review

Ouachani, S. , Belhassine, O. and Kammoun, A. (2021), "Measuring financial literacy: a literature review", Managerial Finance , Vol. 47 No. 2, pp. 266-281. https://doi.org/10.1108/MF-04-2019-0175

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2020, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Measuring financial literacy: a literature review

Related Papers

Fatemeh Kimiyaghalam

This article is a literature review on the concept of financial literacy and its measurements. Based upon the review of several studies, the conceptual definitions of financial literacy would be categorized in four groups; (1) knowledge of financial concepts, (2) ability in managing personal finances, (3) skill in making financial decisions and (4) confidence in future financial planning while in the rest of the studies, researchers apply the combination of these categories. Literature also shows that the applied methods for testing the level of financial literacy in individuals are not constant and they are varied based on the definition of financial literacy.

The Journal of Accounting and Management

Adriana Zait

AARF Publications Journals , monika aggarwal

The need for financial literacy has become increasingly significant with the deregulation of financial markets and the easier access to credit; the ready issue of credit cards; the rapid growth in marketing of financial products and the government's encouragement for people to take more responsibility for their retirement incomes. This paper reports the influence of various socio-demographic factors on different dimensions of financial literacy among the working population in urban India. The study also investigates the relationship between the dimensions of financial literacy. A survey method was employed using a sample of 230 respondents of Tricity. Hypothesis testing was conducted using one way annova test. By identifying the specific areas where financial literacy may be lacking, the paper may assist educators, regulators and financial institutions to design financial planning courses in helping youths to achieve greater financial freedom and be better equipped for retirement.

Indus Foundation International Journals UGC Approved

International Journal of Business and Management

Umberto Filotto

Our purpose is to validate a new questionnaire to measure financial literacy. We test our 18-item questionnaire using a sample of 269 respondents. Data come from an Internet survey in Italy from January to March 2019. Following the definition provided by Organizations of Economics Developments (OECD), we analyze three dimensions of financial literacy: knowledge, skills, and attitude. Regarding skills and attitude, we introduce a new set of items, whereas, for knowledge, we use items proposed by National Financial Capability Studies (NFCS) (2009). We conduct exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis and structural equations models to verify the validity, reliability and applicability of the questionnaire. Our results show that the data fit reasonably well, thus proving the reliability and validity of the questionnaire to measure financial literacy.

International Journal of Consumer Studies

Brenda Cude

International Research Journal of Management Science and Technology

jyoti gupta

In this paper researcher presented the findings of a pilot study conducted by OECD International Network on Financial Education on 14 countries. The variation in financial knowledge, attitude and behavior were studied along with their relationship with socio demographic factors. All three parameters of financial literacy have a lot of room for improvement. OECD INFE developed a survey instrument that can be used for face to face and telephonic interviews. The survey includes basic practice questions and questions on socio demographic factors of the respondents. The survey was not conducted to rank order the countries rather it was designed to show comparison among nations in level of financial literacy.

International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology IJRASET

IJRASET Publication

In today's advance and sophisticated financial landscape, financial literacy is important because it doesn't only influence and impact upon financial decisions at the firm level but also a country's wider financial wellbeing and socioeconomic development. This study compares the financial literacy levels of urban areas by utilizing the results of the survey from the questionnaire developed by the OECD and by examining demographic and socio economic factors that influence the level of financial literacy. The results show that overall, the extent of monetary literacy in both areas is low and necessary measures should be taken by the government to extend awareness of monetary related matters. The literature findings also reveal that demographic, economic, social, and psychological factors are the most determinants, that some common themes appear with reference to the results of monetary literacy on investment decisions, demographic factors, methodology and program effectiveness, and that gaps exist in the literature of financial literacy in Urban area with respect to types of investment and risk tolerance, measurement of monetary literacy, methodology and sources of data.

Journal of Security and Sustainability Issues

Jelena Titko

Policy Research Working Papers

RELATED PAPERS

Lecture Notes in Computer Science

Sergio Rajsbaum

DEMOCRATIZAÇÃO DO CONHECIMENTO E VALORIZAÇÃO PROFISSIONAL: CAMINHOS PARA DESENVOLVIMENTO TECNOLÓGICO E SOCIAL.

Carliane Moreira

Raju Gomathi

Saude E Pesquisa

Renata Medina da Silva

Archives de sciences sociales des religions

Guillaume Roucoux

Bulletin of the Karaganda University. Pedagogy series

Lucimar Braga

BÁO CÁO KHOA HỌC VỀ NGHIÊN CỨU VÀ GIẢNG DẠY SINH HỌC Ở VIỆT NAM - PROCEEDING OF THE 4TH NATIONAL SCIENTIFIC CONFERENCE ON BIOLOGICAL RESEARCH AND TEACHING IN VIETNAM

Nguyễn Minh Trí

Alzheimer's & Dementia

Horst Wallrabe

International Communications in Heat and Mass Transfer

Maria Laura Martins Costa

Elisabetta Sibilio

Abdalla Hussein

Natural product research

qamar ahmed

European Psychiatry

Revista De Medicina E Saude De Brasilia

Ledismar Silva

Physical Review Letters

Journal of Geophysics and Engineering

Mohamed Metwaly

Jurnal Panrita

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta

Fabienne Trolard

Journal of International Legal Communication

Oleg Reznik

Matthew Conner

Setya Pambudi

Carey Williamson

Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine

DANIEL CANTU CERVANTES

Journal of Social and Biological Structures

Denise Baer

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Conference key note

- Open access

- Published: 24 January 2019

Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications

- Annamaria Lusardi 1

Swiss Journal of Economics and Statistics volume 155 , Article number: 1 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

397k Accesses

280 Citations

184 Altmetric

Metrics details

1 Introduction

Throughout their lifetime, individuals today are more responsible for their personal finances than ever before. With life expectancies rising, pension and social welfare systems are being strained. In many countries, employer-sponsored defined benefit (DB) pension plans are swiftly giving way to private defined contribution (DC) plans, shifting the responsibility for retirement saving and investing from employers to employees. Individuals have also experienced changes in labor markets. Skills are becoming more critical, leading to divergence in wages between those with a college education, or higher, and those with lower levels of education. Simultaneously, financial markets are rapidly changing, with developments in technology and new and more complex financial products. From student loans to mortgages, credit cards, mutual funds, and annuities, the range of financial products people have to choose from is very different from what it was in the past, and decisions relating to these financial products have implications for individual well-being. Moreover, the exponential growth in financial technology (fintech) is revolutionizing the way people make payments, decide about their financial investments, and seek financial advice. In this context, it is important to understand how financially knowledgeable people are and to what extent their knowledge of finance affects their financial decision-making.

An essential indicator of people’s ability to make financial decisions is their level of financial literacy. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) aptly defines financial literacy as not only the knowledge and understanding of financial concepts and risks but also the skills, motivation, and confidence to apply such knowledge and understanding in order to make effective decisions across a range of financial contexts, to improve the financial well-being of individuals and society, and to enable participation in economic life. Thus, financial literacy refers to both knowledge and financial behavior, and this paper will analyze research on both topics.

As I describe in more detail below, findings around the world are sobering. Financial literacy is low even in advanced economies with well-developed financial markets. On average, about one third of the global population has familiarity with the basic concepts that underlie everyday financial decisions (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ). The average hides gaping vulnerabilities of certain population subgroups and even lower knowledge of specific financial topics. Furthermore, there is evidence of a lack of confidence, particularly among women, and this has implications for how people approach and make financial decisions. In the following sections, I describe how we measure financial literacy, the levels of literacy we find around the world, the implications of those findings for financial decision-making, and how we can improve financial literacy.

2 How financially literate are people?

2.1 measuring financial literacy: the big three.

In the context of rapid changes and constant developments in the financial sector and the broader economy, it is important to understand whether people are equipped to effectively navigate the maze of financial decisions that they face every day. To provide the tools for better financial decision-making, one must assess not only what people know but also what they need to know, and then evaluate the gap between those things. There are a few fundamental concepts at the basis of most financial decision-making. These concepts are universal, applying to every context and economic environment. Three such concepts are (1) numeracy as it relates to the capacity to do interest rate calculations and understand interest compounding; (2) understanding of inflation; and (3) understanding of risk diversification. Translating these concepts into easily measured financial literacy metrics is difficult, but Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2008 , 2011b , 2011c ) have designed a standard set of questions around these concepts and implemented them in numerous surveys in the USA and around the world.

Four principles informed the design of these questions, as described in detail by Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ). The first is simplicity : the questions should measure knowledge of the building blocks fundamental to decision-making in an intertemporal setting. The second is relevance : the questions should relate to concepts pertinent to peoples’ day-to-day financial decisions over the life cycle; moreover, they must capture general rather than context-specific ideas. Third is brevity : the number of questions must be few enough to secure widespread adoption; and fourth is capacity to differentiate , meaning that questions should differentiate financial knowledge in such a way as to permit comparisons across people. Each of these principles is important in the context of face-to-face, telephone, and online surveys.

Three basic questions (since dubbed the “Big Three”) to measure financial literacy have been fielded in many surveys in the USA, including the National Financial Capability Study (NFCS) and, more recently, the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), and in many national surveys around the world. They have also become the standard way to measure financial literacy in surveys used by the private sector. For example, the Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement included the Big Three questions in the 2018 Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey, covering around 16,000 people in 15 countries. Both ING and Allianz, but also investment funds, and pension funds have used the Big Three to measure financial literacy. The exact wording of the questions is provided in Table 1 .

2.2 Cross-country comparison

The first examination of financial literacy using the Big Three was possible due to a special module on financial literacy and retirement planning that Lusardi and Mitchell designed for the 2004 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), which is a survey of Americans over age 50. Astonishingly, the data showed that only half of older Americans—who presumably had made many financial decisions in their lives—could answer the two basic questions measuring understanding of interest rates and inflation (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ). And just one third demonstrated understanding of these two concepts and answered the third question, measuring understanding of risk diversification, correctly. It is sobering that recent US surveys, such as the 2015 NFCS, the 2016 SCF, and the 2017 Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking (SHED), show that financial knowledge has remained stubbornly low over time.

Over time, the Big Three have been added to other national surveys across countries and Lusardi and Mitchell have coordinated a project called Financial Literacy around the World (FLat World), which is an international comparison of financial literacy (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ).

Findings from the FLat World project, which so far includes data from 15 countries, including Switzerland, highlight the urgent need to improve financial literacy (see Table 2 ). Across countries, financial literacy is at a crisis level, with the average rate of financial literacy, as measured by those answering correctly all three questions, at around 30%. Moreover, only around 50% of respondents in most countries are able to correctly answer the two financial literacy questions on interest rates and inflation correctly. A noteworthy point is that most countries included in the FLat World project have well-developed financial markets, which further highlights the cause for alarm over the demonstrated lack of the financial literacy. The fact that levels of financial literacy are so similar across countries with varying levels of economic development—indicating that in terms of financial knowledge, the world is indeed flat —shows that income levels or ubiquity of complex financial products do not by themselves equate to a more financially literate population.

Other noteworthy findings emerge in Table 2 . For instance, as expected, understanding of the effects of inflation (i.e., of real versus nominal values) among survey respondents is low in countries that have experienced deflation rather than inflation: in Japan, understanding of inflation is at 59%; in other countries, such as Germany, it is at 78% and, in the Netherlands, it is at 77%. Across countries, individuals have the lowest level of knowledge around the concept of risk, and the percentage of correct answers is particularly low when looking at knowledge of risk diversification. Here, we note the prevalence of “do not know” answers. While “do not know” responses hover around 15% on the topic of interest rates and 18% for inflation, about 30% of respondents—in some countries even more—are likely to respond “do not know” to the risk diversification question. In Switzerland, 74% answered the risk diversification question correctly and 13% reported not knowing the answer (compared to 3% and 4% responding “do not know” for the interest rates and inflation questions, respectively).

These findings are supported by many other surveys. For example, the 2014 Standard & Poor’s Global Financial Literacy Survey shows that, around the world, people know the least about risk and risk diversification (Klapper, Lusardi, and Van Oudheusden, 2015 ). Similarly, results from the 2016 Allianz survey, which collected evidence from ten European countries on money, financial literacy, and risk in the digital age, show very low-risk literacy in all countries covered by the survey. In Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, which are the three top-performing nations in term of financial knowledge, less than 20% of respondents can answer three questions related to knowledge of risk and risk diversification (Allianz, 2017 ).

Other surveys show that the findings about financial literacy correlate in an expected way with other data. For example, performance on the mathematics and science sections of the OECD Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) correlates with performance on the Big Three and, specifically, on the question relating to interest rates. Similarly, respondents in Sweden, which has experienced pension privatization, performed better on the risk diversification question (at 68%), than did respondents in Russia and East Germany, where people have had less exposure to the stock market. For researchers studying financial knowledge and its effects, these findings hint to the fact that financial literacy could be the result of choice and not an exogenous variable.

To summarize, financial literacy is low across the world and higher national income levels do not equate to a more financially literate population. The design of the Big Three questions enables a global comparison and allows for a deeper understanding of financial literacy. This enhances the measure’s utility because it helps to identify general and specific vulnerabilities across countries and within population subgroups, as will be explained in the next section.

2.3 Who knows the least?

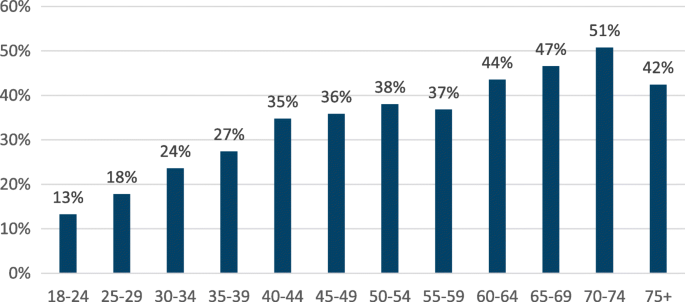

Low financial literacy on average is exacerbated by patterns of vulnerability among specific population subgroups. For instance, as reported in Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2014 ), even though educational attainment is positively correlated with financial literacy, it is not sufficient. Even well-educated people are not necessarily savvy about money. Financial literacy is also low among the young. In the USA, less than 30% of respondents can correctly answer the Big Three by age 40, even though many consequential financial decisions are made well before that age (see Fig. 1 ). Similarly, in Switzerland, only 45% of those aged 35 or younger are able to correctly answer the Big Three questions. Footnote 1 And if people may learn from making financial decisions, that learning seems limited. As shown in Fig. 1 , many older individuals, who have already made decisions, cannot answer three basic financial literacy questions.

Financial literacy across age in the USA. This figure shows the percentage of respondents who answered correctly all Big Three questions by age group (year 2015). Source: 2015 US National Financial Capability Study

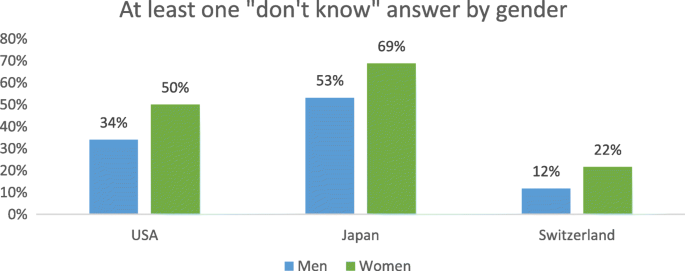

A gender gap in financial literacy is also present across countries. Women are less likely than men to answer questions correctly. The gap is present not only on the overall scale but also within each topic, across countries of different income levels, and at different ages. Women are also disproportionately more likely to indicate that they do not know the answer to specific questions (Fig. 2 ), highlighting overconfidence among men and awareness of lack of knowledge among women. Even in Finland, which is a relatively equal society in terms of gender, 44% of men compared to 27% of women answer all three questions correctly and 18% of women give at least one “do not know” response versus less than 10% of men (Kalmi and Ruuskanen, 2017 ). These figures further reflect the universality of the Big Three questions. As reported in Fig. 2 , “do not know” responses among women are prevalent not only in European countries, for example, Switzerland, but also in North America (represented in the figure by the USA, though similar findings are reported in Canada) and in Asia (represented in the figure by Japan). Those interested in learning more about the differences in financial literacy across demographics and other characteristics can consult Lusardi and Mitchell ( 2011c , 2014 ).

Gender differences in the responses to the Big Three questions. Sources: USA—Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011c ; Japan—Sekita, 2011 ; Switzerland—Brown and Graf, 2013

3 Does financial literacy matter?

A growing number of financial instruments have gained importance, including alternative financial services such as payday loans, pawnshops, and rent to own stores that charge very high interest rates. Simultaneously, in the changing economic landscape, people are increasingly responsible for personal financial planning and for investing and spending their resources throughout their lifetime. We have witnessed changes not only in the asset side of household balance sheets but also in the liability side. For example, in the USA, many people arrive close to retirement carrying a lot more debt than previous generations did (Lusardi, Mitchell, and Oggero, 2018 ). Overall, individuals are making substantially more financial decisions over their lifetime, living longer, and gaining access to a range of new financial products. These trends, combined with low financial literacy levels around the world and, particularly, among vulnerable population groups, indicate that elevating financial literacy must become a priority for policy makers.

There is ample evidence of the impact of financial literacy on people’s decisions and financial behavior. For example, financial literacy has been proven to affect both saving and investment behavior and debt management and borrowing practices. Empirically, financially savvy people are more likely to accumulate wealth (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2014 ). There are several explanations for why higher financial literacy translates into greater wealth. Several studies have documented that those who have higher financial literacy are more likely to plan for retirement, probably because they are more likely to appreciate the power of interest compounding and are better able to do calculations. According to the findings of the FLat World project, answering one additional financial question correctly is associated with a 3–4 percentage point greater probability of planning for retirement; this finding is seen in Germany, the USA, Japan, and Sweden. Financial literacy is found to have the strongest impact in the Netherlands, where knowing the right answer to one additional financial literacy question is associated with a 10 percentage point higher probability of planning (Mitchell and Lusardi, 2015 ). Empirically, planning is a very strong predictor of wealth; those who plan arrive close to retirement with two to three times the amount of wealth as those who do not plan (Lusardi and Mitchell, 2011b ).

Financial literacy is also associated with higher returns on investments and investment in more complex assets, such as stocks, which normally offer higher rates of return. This finding has important consequences for wealth; according to the simulation by Lusardi, Michaud, and Mitchell ( 2017 ), in the context of a life-cycle model of saving with many sources of uncertainty, from 30 to 40% of US retirement wealth inequality can be accounted for by differences in financial knowledge. These results show that financial literacy is not a sideshow, but it plays a critical role in saving and wealth accumulation.

Financial literacy is also strongly correlated with a greater ability to cope with emergency expenses and weather income shocks. Those who are financially literate are more likely to report that they can come up with $2000 in 30 days or that they are able to cover an emergency expense of $400 with cash or savings (Hasler, Lusardi, and Oggero, 2018 ).

With regard to debt behavior, those who are more financially literate are less likely to have credit card debt and more likely to pay the full balance of their credit card each month rather than just paying the minimum due (Lusardi and Tufano, 2009 , 2015 ). Individuals with higher financial literacy levels also are more likely to refinance their mortgages when it makes sense to do so, tend not to borrow against their 401(k) plans, and are less likely to use high-cost borrowing methods, e.g., payday loans, pawn shops, auto title loans, and refund anticipation loans (Lusardi and de Bassa Scheresberg, 2013 ).

Several studies have documented poor debt behavior and its link to financial literacy. Moore ( 2003 ) reported that the least financially literate are also more likely to have costly mortgages. Lusardi and Tufano ( 2015 ) showed that the least financially savvy incurred high transaction costs, paying higher fees and using high-cost borrowing methods. In their study, the less knowledgeable also reported excessive debt loads and an inability to judge their debt positions. Similarly, Mottola ( 2013 ) found that those with low financial literacy were more likely to engage in costly credit card behavior, and Utkus and Young ( 2011 ) concluded that the least literate were more likely to borrow against their 401(k) and pension accounts.

Young people also struggle with debt, in particular with student loans. According to Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Oggero ( 2016 ), Millennials know little about their student loans and many do not attempt to calculate the payment amounts that will later be associated with the loans they take. When asked what they would do, if given the chance to revisit their student loan borrowing decisions, about half of Millennials indicate that they would make a different decision.

Finally, a recent report on Millennials in the USA (18- to 34-year-olds) noted the impact of financial technology (fintech) on the financial behavior of young individuals. New and rapidly expanding mobile payment options have made transactions easier, quicker, and more convenient. The average user of mobile payments apps and technology in the USA is a high-income, well-educated male who works full time and is likely to belong to an ethnic minority group. Overall, users of mobile payments are busy individuals who are financially active (holding more assets and incurring more debt). However, mobile payment users display expensive financial behaviors, such as spending more than they earn, using alternative financial services, and occasionally overdrawing their checking accounts. Additionally, mobile payment users display lower levels of financial literacy (Lusardi, de Bassa Scheresberg, and Avery, 2018 ). The rapid growth in fintech around the world juxtaposed with expensive financial behavior means that more attention must be paid to the impact of mobile payment use on financial behavior. Fintech is not a substitute for financial literacy.

4 The way forward for financial literacy and what works

Overall, financial literacy affects everything from day-to-day to long-term financial decisions, and this has implications for both individuals and society. Low levels of financial literacy across countries are correlated with ineffective spending and financial planning, and expensive borrowing and debt management. These low levels of financial literacy worldwide and their widespread implications necessitate urgent efforts. Results from various surveys and research show that the Big Three questions are useful not only in assessing aggregate financial literacy but also in identifying vulnerable population subgroups and areas of financial decision-making that need improvement. Thus, these findings are relevant for policy makers and practitioners. Financial illiteracy has implications not only for the decisions that people make for themselves but also for society. The rapid spread of mobile payment technology and alternative financial services combined with lack of financial literacy can exacerbate wealth inequality.

To be effective, financial literacy initiatives need to be large and scalable. Schools, workplaces, and community platforms provide unique opportunities to deliver financial education to large and often diverse segments of the population. Furthermore, stark vulnerabilities across countries make it clear that specific subgroups, such as women and young people, are ideal targets for financial literacy programs. Given women’s awareness of their lack of financial knowledge, as indicated via their “do not know” responses to the Big Three questions, they are likely to be more receptive to financial education.

The near-crisis levels of financial illiteracy, the adverse impact that it has on financial behavior, and the vulnerabilities of certain groups speak of the need for and importance of financial education. Financial education is a crucial foundation for raising financial literacy and informing the next generations of consumers, workers, and citizens. Many countries have seen efforts in recent years to implement and provide financial education in schools, colleges, and workplaces. However, the continuously low levels of financial literacy across the world indicate that a piece of the puzzle is missing. A key lesson is that when it comes to providing financial education, one size does not fit all. In addition to the potential for large-scale implementation, the main components of any financial literacy program should be tailored content, targeted at specific audiences. An effective financial education program efficiently identifies the needs of its audience, accurately targets vulnerable groups, has clear objectives, and relies on rigorous evaluation metrics.

Using measures like the Big Three questions, it is imperative to recognize vulnerable groups and their specific needs in program designs. Upon identification, the next step is to incorporate this knowledge into financial education programs and solutions.

School-based education can be transformational by preparing young people for important financial decisions. The OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), in both 2012 and 2015, found that, on average, only 10% of 15-year-olds achieved maximum proficiency on a five-point financial literacy scale. As of 2015, about one in five of students did not have even basic financial skills (see OECD, 2017 ). Rigorous financial education programs, coupled with teacher training and high school financial education requirements, are found to be correlated with fewer defaults and higher credit scores among young adults in the USA (Urban, Schmeiser, Collins, and Brown, 2018 ). It is important to target students and young adults in schools and colleges to provide them with the necessary tools to make sound financial decisions as they graduate and take on responsibilities, such as buying cars and houses, or starting retirement accounts. Given the rising cost of education and student loan debt and the need of young people to start contributing as early as possible to retirement accounts, the importance of financial education in school cannot be overstated.

There are three compelling reasons for having financial education in school. First, it is important to expose young people to the basic concepts underlying financial decision-making before they make important and consequential financial decisions. As noted in Fig. 1 , financial literacy is very low among the young and it does not seem to increase a lot with age/generations. Second, school provides access to financial literacy to groups who may not be exposed to it (or may not be equally exposed to it), for example, women. Third, it is important to reduce the costs of acquiring financial literacy, if we want to promote higher financial literacy both among individuals and among society.

There are compelling reasons to have personal finance courses in college as well. In the same way in which colleges and university offer courses in corporate finance to teach how to manage the finances of firms, so today individuals need the knowledge to manage their own finances over the lifetime, which in present discounted value often amount to large values and are made larger by private pension accounts.

Financial education can also be efficiently provided in workplaces. An effective financial education program targeted to adults recognizes the socioeconomic context of employees and offers interventions tailored to their specific needs. A case study conducted in 2013 with employees of the US Federal Reserve System showed that completing a financial literacy learning module led to significant changes in retirement planning behavior and better-performing investment portfolios (Clark, Lusardi, and Mitchell, 2017 ). It is also important to note the delivery method of these programs, especially when targeted to adults. For instance, video formats have a significantly higher impact on financial behavior than simple narratives, and instruction is most effective when it is kept brief and relevant (Heinberg et al., 2014 ).

The Big Three also show that it is particularly important to make people familiar with the concepts of risk and risk diversification. Programs devoted to teaching risk via, for example, visual tools have shown great promise (Lusardi et al., 2017 ). The complexity of some of these concepts and the costs of providing education in the workplace, coupled with the fact that many older individuals may not work or work in firms that do not offer such education, provide other reasons why financial education in school is so important.

Finally, it is important to provide financial education in the community, in places where people go to learn. A recent example is the International Federation of Finance Museums, an innovative global collaboration that promotes financial knowledge through museum exhibits and the exchange of resources. Museums can be places where to provide financial literacy both among the young and the old.

There are a variety of other ways in which financial education can be offered and also targeted to specific groups. However, there are few evaluations of the effectiveness of such initiatives and this is an area where more research is urgently needed, given the statistics reported in the first part of this paper.

5 Concluding remarks

The lack of financial literacy, even in some of the world’s most well-developed financial markets, is of acute concern and needs immediate attention. The Big Three questions that were designed to measure financial literacy go a long way in identifying aggregate differences in financial knowledge and highlighting vulnerabilities within populations and across topics of interest, thereby facilitating the development of tailored programs. Many such programs to provide financial education in schools and colleges, workplaces, and the larger community have taken existing evidence into account to create rigorous solutions. It is important to continue making strides in promoting financial literacy, by achieving scale and efficiency in future programs as well.

In August 2017, I was appointed Director of the Italian Financial Education Committee, tasked with designing and implementing the national strategy for financial literacy. I will be able to apply my research to policy and program initiatives in Italy to promote financial literacy: it is an essential skill in the twenty-first century, one that individuals need if they are to thrive economically in today’s society. As the research discussed in this paper well documents, financial literacy is like a global passport that allows individuals to make the most of the plethora of financial products available in the market and to make sound financial decisions. Financial literacy should be seen as a fundamental right and universal need, rather than the privilege of the relatively few consumers who have special access to financial knowledge or financial advice. In today’s world, financial literacy should be considered as important as basic literacy, i.e., the ability to read and write. Without it, individuals and societies cannot reach their full potential.

See Brown and Graf ( 2013 ).

Abbreviations

Defined benefit (refers to pension plan)

Defined contribution (refers to pension plan)

Financial Literacy around the World

National Financial Capability Study

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

Programme for International Student Assessment

Survey of Consumer Finances

Survey of Household Economics and Financial Decisionmaking

Aegon Center for Longevity and Retirement. (2018). The New Social Contract: a blueprint for retirement in the 21st century. The Aegon Retirement Readiness Survey 2018. Retrieved from https://www.aegon.com/en/Home/Research/aegon-retirement-readiness-survey-2018/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Agnew, J., Bateman, H., & Thorp, S. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Australia. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Allianz (2017). When will the penny drop? Money, financial literacy and risk in the digital age. Retrieved from http://gflec.org/initiatives/money-finlit-risk/ . Accessed 1 June 2018.

Almenberg, J., & Säve-Söderbergh, J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Sweden. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 585–598.

Article Google Scholar

Arrondel, L., Debbich, M., & Savignac, F. (2013). Financial literacy and financial planning in France. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Beckmann, E. (2013). Financial literacy and household savings in Romania. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Boisclair, D., Lusardi, A., & Michaud, P. C. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Canada. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 277–296.

Brown, M., & Graf, R. (2013). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Switzerland. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Bucher-Koenen, T., & Lusardi, A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 565–584.

Clark, R., Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Employee financial literacy and retirement plan behavior: a case study. Economic Inquiry, 55 (1), 248–259.

Crossan, D., Feslier, D., & Hurnard, R. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in New Zealand. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 619–635.

Fornero, E., & Monticone, C. (2011). Financial literacy and pension plan participation in Italy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 547–564.

Hasler, A., Lusardi, A., and Oggero, N. (2018). Financial fragility in the US: evidence and implications. GFLEC working paper n. 2018–1.

Heinberg, A., Hung, A., Kapteyn, A., Lusardi, A., Samek, A. S., & Yoong, J. (2014). Five steps to planning success: experimental evidence from US households. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 30 (4), 697–724.

Kalmi, P., & Ruuskanen, O. P. (2017). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Finland. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 17 (3), 1–28.

Klapper, L., Lusardi, A., & Van Oudheusden, P. (2015). Financial literacy around the world. In Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services Global Financial Literacy Survey (GFLEC working paper).

Google Scholar

Klapper, L., & Panos, G. A. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning: The Russian case. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 599–618.

Lusardi, A., & de Bassa Scheresberg, C. (2013). Financial literacy and high-cost borrowing in the United States, NBER Working Paper n. 18969, April .

Book Google Scholar

Lusardi, A., de Bassa Scheresberg, C., and Avery, M. 2018. Millennial mobile payment users: a look into their personal finances and financial behaviors. GFLEC working paper.

Lusardi, A., de Bassa Scheresberg, C., & Oggero, N. (2016). Student loan debt in the US: an analysis of the 2015 NFCS Data, GFLEC Policy Brief, November .

Lusardi, A., Michaud, P. C., & Mitchell, O. S. (2017). Optimal financial knowledge and wealth inequality. Journal of Political Economy, 125 (2), 431–477.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2008). Planning and financial literacy: how do women fare? American Economic Review, 98 , 413–417.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011a). The outlook for financial literacy. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 1–15). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011b). Financial literacy and planning: implications for retirement wellbeing. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 17–39). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2011c). Financial literacy around the world: an overview. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (4), 497–508.

Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. S. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52 (1), 5–44.

Lusardi, A., Mitchell, O. S., & Oggero, N. (2018). The changing face of debt and financial fragility at older ages. American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings, 108 , 407–411.

Lusardi, A., Samek, A., Kapteyn, A., Glinert, L., Hung, A., & Heinberg, A. (2017). Visual tools and narratives: new ways to improve financial literacy. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 16 (3), 297–323.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2009). Teach workers about the peril of debt. Harvard Business Review , 22–24.

Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2015). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 14 (4), 332–368.

Mitchell, O. S., & Lusardi, A. (2015). Financial literacy and economic outcomes: evidence and policy implications. The Journal of Retirement, 3 (1).

Moore, Danna. 2003. Survey of financial literacy in Washington State: knowledge, behavior, attitudes and experiences. Washington State University Social and Economic Sciences Research Center Technical Report 03–39.

Mottola, G. R. (2013). In our best interest: women, financial literacy, and credit card behavior. Numeracy, 6 (2).

Moure, N. G. (2016). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Chile. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 15 (2), 203–223.

OECD. (2017). PISA 2015 results (Volume IV): students’ financial literacy . Paris: PISA, OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264270282-en .

Sekita, S. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement planning in Japan. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 10 (4), 637–656.

Urban, C., Schmeiser, M., Collins, J. M., & Brown, A. (2018). The effects of high school personal financial education policies on financial behavior. Economics of Education Review . https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0272775718301699 .

Utkus, S., & Young, J. (2011). Financial literacy and 401(k) loans. In O. S. Mitchell & A. Lusardi (Eds.), Financial literacy: implications for retirement security and the financial marketplace (pp. 59–75). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Rooij, M. C., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. J. (2011). Financial literacy and retirement preparation in the Netherlands. Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 10 (4), 527–545.

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper represents a summary of the keynote address I gave to the 2018 Annual Meeting of the Swiss Society of Economics and Statistics. I would like to thank Monika Butler, Rafael Lalive, anonymous reviewers, and participants of the Annual Meeting for useful discussions and comments, and Raveesha Gupta for editorial support. All errors are my responsibility.

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

Author information, authors and affiliations.

The George Washington University School of Business Global Financial Literacy Excellence Center and Italian Committee for Financial Education, Washington, D.C., USA

Annamaria Lusardi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Annamaria Lusardi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The author declares that she has no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lusardi, A. Financial literacy and the need for financial education: evidence and implications. Swiss J Economics Statistics 155 , 1 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Download citation

Received : 22 October 2018

Accepted : 07 January 2019

Published : 24 January 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s41937-019-0027-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Advanced search

- Peer review

- Record : found

- Abstract : not found

- Article : not found

Measuring financial literacy: a literature review

Read this article at, author and article information , comment on this article.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The purpose of this paper is to review the main methods used in the literature to measure financial literacy (FL) of individuals.,The paper begins by describing how the different items used to measure the FL level of individuals are constructed. Then, it focuses on how do researchers select the items.

Measuring financial literacy: a literature review. Alternate title: Measuring financial literacy Ouachani, Sonia; Belhassine ... Two main problems arise when measuring FL. The first is the number of questions to be asked. van Rooij et al. (2011a) and Schuhen and Schürkmann (2014) note that it is very restrictive to limit the number of ...

Abstract. Purpose The purpose of this paper is to review the main methods used in the literature to measure financial literacy (FL) of individuals. Design/methodology/approach The paper begins by ...

This article is a literature review on the concept of financial literacy and its measurements. Based upon the review of several studies, the conceptual definitions of financial literacy would be categorized in four groups; (1) knowledge of financial concepts, (2) ability in managing personal finances, (3) skill in making financial decisions and (4) confidence in future financial planning while ...

Defining and appropriately measuring financial literacy is essential to understand educational impact as well as barriers to effective financial choice. This article summarizes the broad range of financial literacy measures used in research over the last decade. ... Review of the literature over the last decade indicated that at least four ...

Several studies focus on the definition and the measure of this concept. Different items are used in the literature and are mostly related to the study topics. The used calculation methods differ across the different studies.Originality/valueThis paper sheds light on the principal methodologies used in the literature to measure FL.

Given the paucity of comprehensive summaries in the extant literature, this systematic review, coupled with bibliometric analysis, endeavours to take a meticulous approach intended at presenting quantitative and qualitative knowledge on the ever-emerging subject of financial literacy.

The purpose of this article is to examine previous literature to identify obstacles, and propose an approach, to develop a more standardized measure of financial literacy. Previous literature that attempts to measure human capital specific to personal finance is reviewed to identify how financial literacy is currently conceptualized and ...

Financial literacy is a critical life skill that is essential for achieving financial security and individual well-being, economic growth and overall sustainable development. Based on the analysis of research on financial literacy, we aim to provide a balance sheet of current research and a starting point for future research with the focus on identifying significant predictors of financial ...

The Big Three questions that were designed to measure financial literacy go a long way in identifying aggregate differences in financial knowledge and highlighting vulnerabilities within populations and across topics of interest, thereby facilitating the development of tailored programs. ... Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 30(4), 697-724 ...

Literature Review and Hypothesis Development Measuring Household Financial Vulnerability. ... support the notion that the commonly used Big Three or Big Five financial literacy questions may be insufficient in measuring financial literacy comprehensively. Additionally, the findings highlight the difference in how objective and self-perceived ...

A Literature Review On Financial Literacy. June 2014; ... (ii) objective measures seem to work best in measuring financial literacy among individuals, (iii) researchers should reconsider about ...

One of the striking things about the literature is that financial literacy has been variably defined as (a) a specific form of knowledge, (b) the ability or skills to apply that knowledge, (c) perceived knowledge, (d) good financial behavior, and even (e) financial experiences.

Discovery Metadata Peer review Hosting Publishing. For Researchers. Join Publish Review Collect. My ScienceOpen . Sign in Register . Dashboard ; Blog About . Search Advanced search. ... Measuring financial literacy: a literature review. Author(s): Sonia Ouachani, Olfa Belhassine, Aïda Kammoun . Publication date: 2020.

Financial (il-)literacy and its effects have been studied extensively in recent years. The measurement of this concept is, however, tricky and numerous measurement instruments exist. In this paper, we study the connection between these measures empirically. We find that these measures are often only slightly related and that this is a so-far overlooked empirical problem in this field. As a ...

1. an initial measure of financial literacy to identify national levels of financial literacy, provide a baseline and set benchmarks for national strategies or particular programmes; 2. a description of levels of financial literacy in terms of key socio-demographic groups and

Defining and Measuring Financial Literacy. Angela A. Hung, Andrew M. Parker, J. Yoong. Published 2 September 2009. Economics, Education. EduRN: Financial Economics Education (FEN) (Topic) Provides a review of theoretical and operational approaches to financial literacy, as well as a conceptual model and composite definition of financial literacy.

Financial literacy (or financial knowledge) is typically an input to. model the need for financial education and explain variation in finan cial outcomes. Defining and appropriately measuring financial literacy. is essential to understand educational impact as well as barriers to effective financial choice.

With the need for this research clearly established, the current study formally attempts: 1) To combine the literature at the intersection of financial literacy and financial inclusion through a systematic mapping study and literature review; 2) To study the evolution of financial literacy, and financial inclusion in empirical literature; 3) To ...

RAND is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and decisionmaking through research and analysis. RAND's publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Provides a review of theoretical and operational approaches to financial literacy, as well as a conceptual model and composite definition of ...

Financial literacy (or financial knowledge) is typically an input to model the need for financial education and explain variation in financial outcomes. Defining and appropriately measuring financial literacy is essential to understand educational impact as well as barriers to effective financial choice. This article summarizes the broad range ...

Financial literacy (or financial knowledge) is typically an input to model the need for financial education and explain variation in financial outcomes. Defining and appropriately measuring financial literacy is essential to understand educational impact as well as barriers to effective financial choice. This article summarizes the broad range ...

The current study has attempted to review the financial literacy research papers in a systematic manner incorporating the multiple facets ranging from impact of demographic factors to present state of financial literacy literature in the Indian context. Papers published by selective global publishers in the last two decades have been reviewed ...

Australian Economic Review is an applied economics journal with a strong policy ... Based on this they designed and tested three questions aimed at measuring financial literacy. These three questions are commonly known as the 'Big-3' and now feature in surveys globally, including HILDA. ... While there is an extensive literature on the ...

Introduction. Opinion leaders and experts have recently focused on financial inclusion and its impact on the world economy. Financial inclusion (FI) is a tool financial institutions and policymakers use to support the development of the financial sector and guarantee long-term, equitable, and sustainable economic growth (Collard, Citation 2010).Only 20% of individuals in the poorest developing ...