Appointments at Mayo Clinic

Alzheimer's treatments: what's on the horizon.

Despite many promising leads, new treatments for Alzheimer's are slow to emerge.

Current Alzheimer's treatments temporarily improve symptoms of memory loss and problems with thinking and reasoning.

These Alzheimer's treatments boost the performance of chemicals in the brain that carry information from one brain cell to another. They include cholinesterase inhibitors and the medicine memantine (Namenda). However, these treatments don't stop the underlying decline and death of brain cells. As more cells die, Alzheimer's disease continues to progress.

Experts are cautious but hopeful about developing treatments that can stop or delay the progression of Alzheimer's. Experts continue to better understand how the disease changes the brain. This has led to the research of potential Alzheimer's treatments that may affect the disease process.

Future Alzheimer's treatments may include a combination of medicines. This is similar to treatments for many cancers or HIV / AIDS that include more than one medicine.

These are some of the strategies currently being studied.

Taking aim at plaques

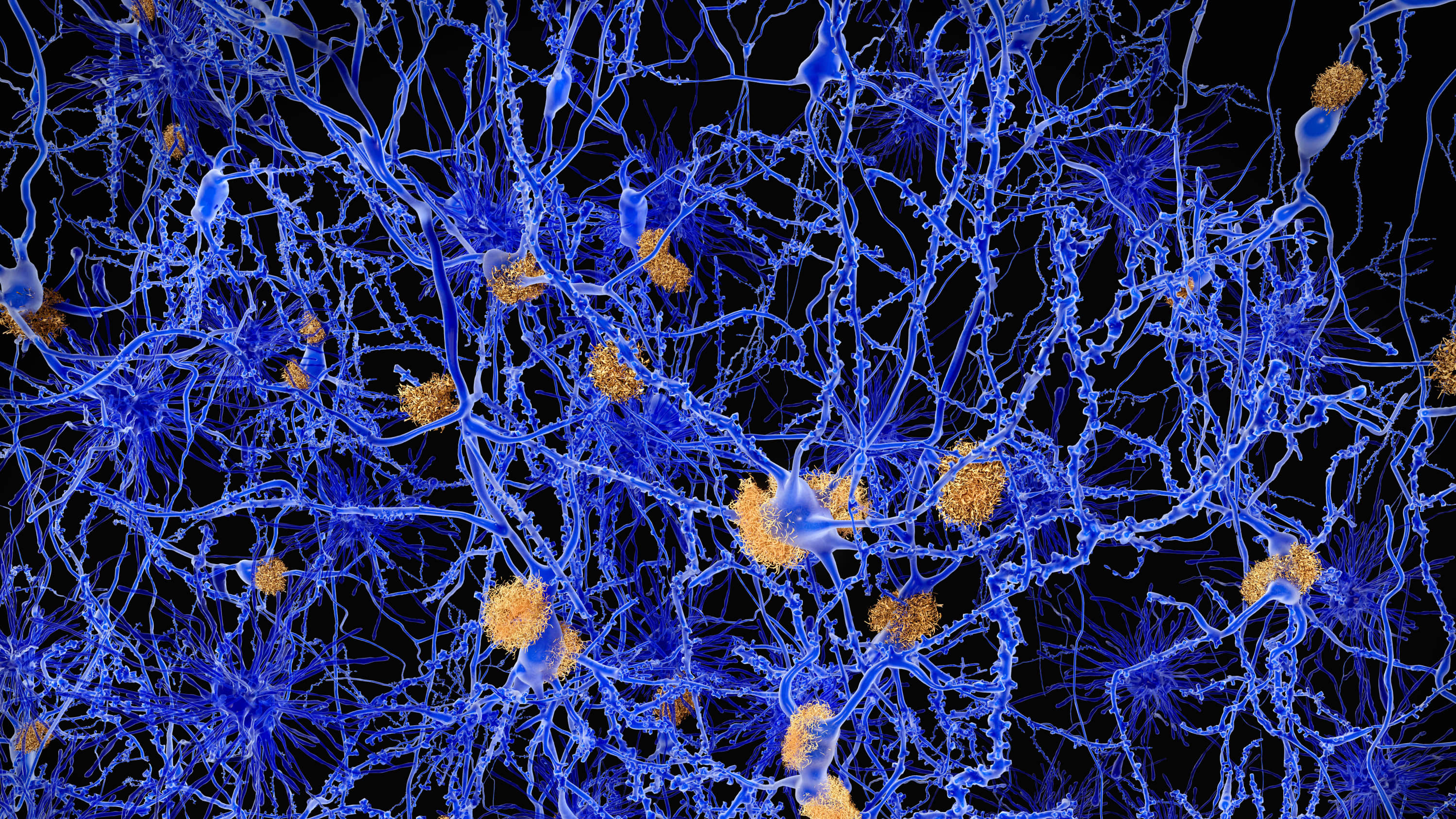

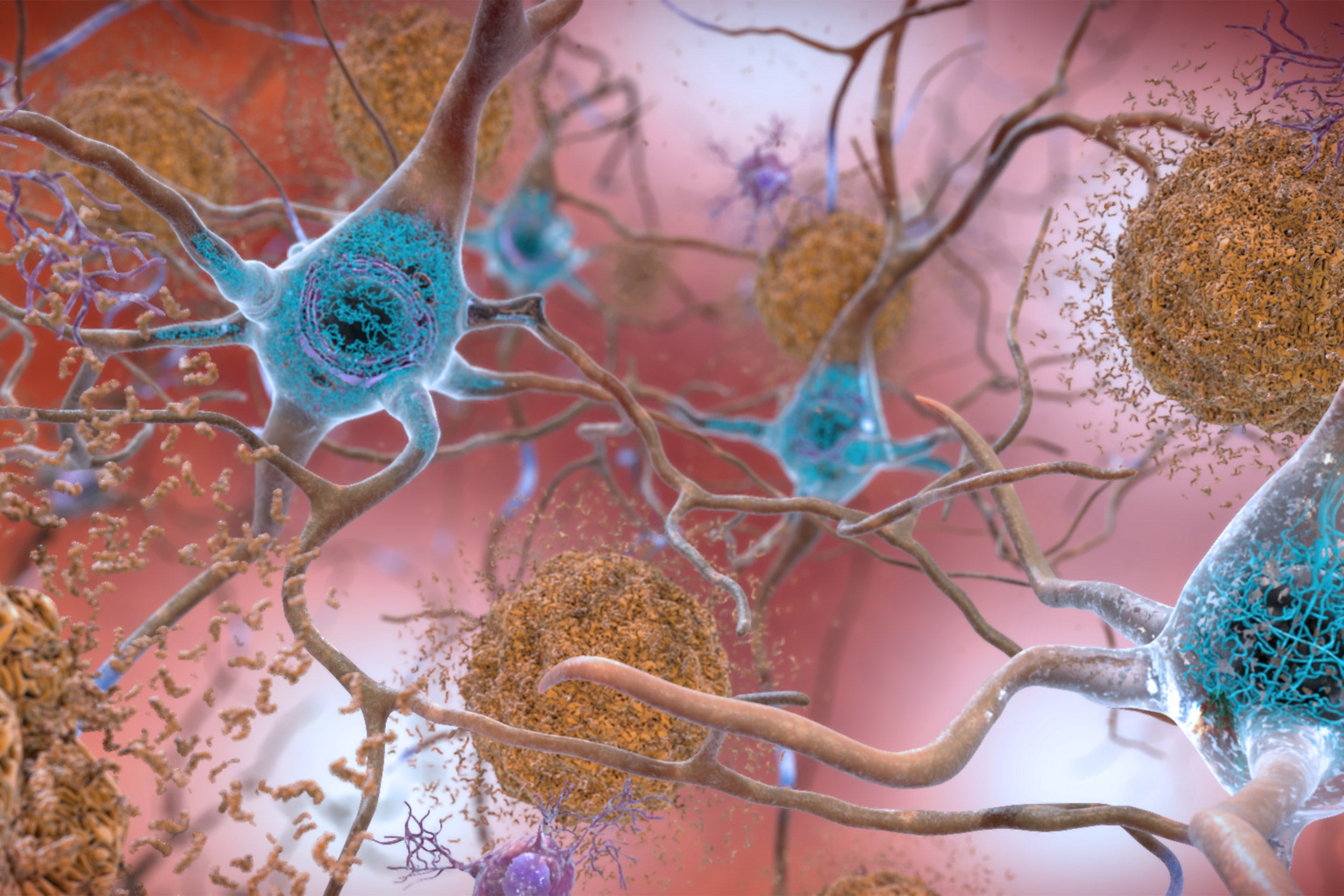

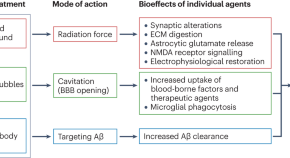

Some of the new Alzheimer's treatments target clumps of the protein beta-amyloid, known as plaques, in the brain. Plaques are a characteristic sign of Alzheimer's disease.

Strategies aimed at beta-amyloid include:

Recruiting the immune system. Medicines known as monoclonal antibodies may prevent beta-amyloid from clumping into plaques. They also may remove beta-amyloid plaques that have formed. They do this by helping the body clear them from the brain. These medicines mimic the antibodies your body naturally produces as part of your immune system's response to foreign invaders or vaccines.

In 2023, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved lecanemab (Leqembi) for people with mild Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer's disease.

A phase 3 clinical trial found that the medicine slowed cognitive decline in people with early Alzheimer's disease. The medicine prevents amyloid plaques in the brain from clumping. The phase 3 trial was the largest so far to study whether clearing clumps of amyloid plaques from the brain can slow the disease.

Lecanemab is given as an IV infusion every two weeks. Your care team likely will watch for side effects and ask you or your caregiver how your body reacts to the drug. Side effects of lecanemab include infusion-related reactions such as fever, flu-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, changes in heart rate and shortness of breath.

Also, people taking lecanemab may have swelling in the brain or may get small bleeds in the brain. Rarely, brain swelling can be serious enough to cause seizures and other symptoms. Also in rare instances, bleeding in the brain can cause death. The FDA recommends getting a brain MRI before starting treatment. It also recommends being monitored with brain MRI s during treatment for symptoms of brain swelling or bleeding.

People who carry a certain form of a gene known as APOE e4 appear to have a higher risk of these serious complications. The FDA recommends being tested for this gene before starting treatment with lecanemab.

If you take a blood thinner or have other risk factors for brain bleeding, talk to your health care professional before taking lecanemab. Blood-thinning medicines may increase the risk of bleeds in the brain.

More research is being done on the potential risks of taking lecanemab. Other research is looking at how effective lecanemab may be for people at risk of Alzheimer's disease, including people who have a first-degree relative, such as a parent or sibling, with the disease.

Another medicine being studied is donanemab. It targets and reduces amyloid plaques and tau proteins. It was found to slow declines in thinking and functioning in people with early Alzheimer's disease.

The monoclonal antibody solanezumab did not show benefits for individuals with preclinical, mild or moderate Alzheimer's disease. Solanezumab did not lower beta-amyloid in the brain, which may be why it wasn't effective.

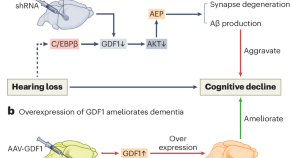

Preventing destruction. A medicine initially developed as a possible cancer treatment — saracatinib — is now being tested in Alzheimer's disease.

In mice, saracatinib turned off a protein that allowed synapses to start working again. Synapses are the tiny spaces between brain cells through which the cells communicate. The animals in the study experienced a reversal of some memory loss. Human trials for saracatinib as a possible Alzheimer's treatment are now underway.

Production blockers. These therapies may reduce the amount of beta-amyloid formed in the brain. Research has shown that beta-amyloid is produced from a "parent protein" in two steps performed by different enzymes.

Several experimental medicines aim to block the activity of these enzymes. They're known as beta- and gamma-secretase inhibitors. Recent studies showed that the beta-secretase inhibitors did not slow cognitive decline. They also were associated with significant side effects in those with mild or moderate Alzheimer's. This has decreased enthusiasm for the medicines.

Keeping tau from tangling

A vital brain cell transport system collapses when a protein called tau twists into tiny fibers. These fibers are called tangles. They are another common change in the brains of people with Alzheimer's. Researchers are looking at a way to prevent tau from forming tangles.

Tau aggregation inhibitors and tau vaccines are currently being studied in clinical trials.

Reducing inflammation

Alzheimer's causes chronic, low-level brain cell inflammation. Researchers are studying ways to treat the processes that lead to inflammation in Alzheimer's disease. The medicine sargramostim (Leukine) is currently in research. The medicine may stimulate the immune system to protect the brain from harmful proteins.

Researching insulin resistance

Studies are looking into how insulin may affect the brain and brain cell function. Researchers are studying how insulin changes in the brain may be related to Alzheimer's. However, a trial testing of an insulin nasal spray determined that the medicine wasn't effective in slowing the progression of Alzheimer's.

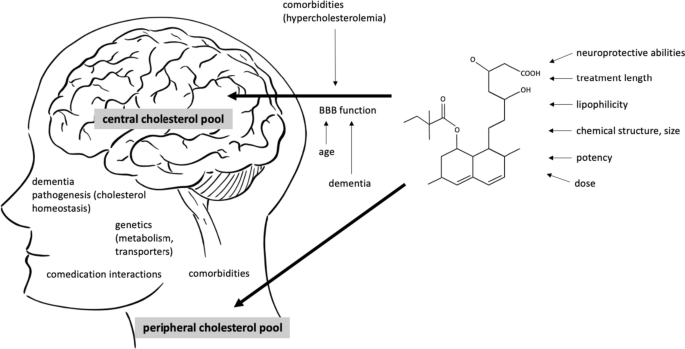

Studying the heart-head connection

Growing evidence suggests that brain health is closely linked to heart and blood vessel health. The risk of developing dementia appears to increase as a result of many conditions that damage the heart or arteries. These include high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, diabetes and high cholesterol.

A number of studies are exploring how best to build on this connection. Strategies being researched include:

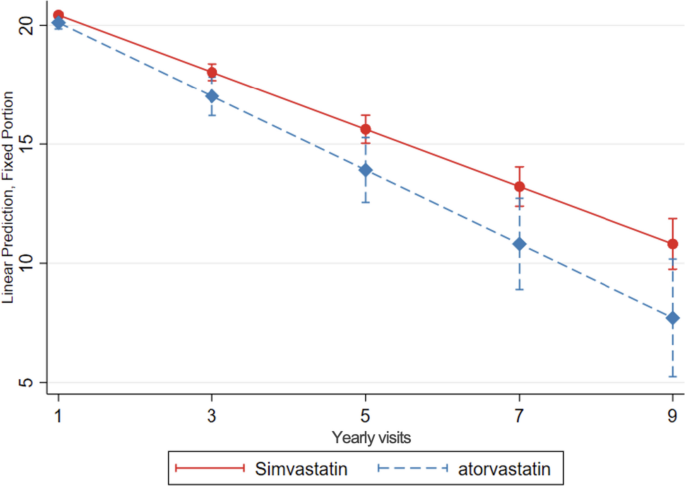

- Current medicines for heart disease risk factors. Researchers are looking into whether blood pressure medicines may benefit people with Alzheimer's. They're also studying whether the medicines may reduce the risk of dementia.

- Medicines aimed at new targets. Other studies are looking more closely at how the connection between heart disease and Alzheimer's works at the molecular level. The goal is to find new potential medicines for Alzheimer's.

- Lifestyle choices. Research suggests that lifestyle choices with known heart benefits may help prevent Alzheimer's disease or delay its onset. Those lifestyle choices include exercising on most days and eating a heart-healthy diet.

Studies during the 1990s suggested that taking hormone replacement therapy during perimenopause and menopause lowered the risk of Alzheimer's disease. But further research has been mixed. Some studies found no cognitive benefit of taking hormone replacement therapy. More research and a better understanding of the relationship between estrogen and cognitive function are needed.

Speeding treatment development

Developing new medicines is a slow process. The pace can be frustrating for people with Alzheimer's and their families who are waiting for new treatment options.

To help speed discovery, the Critical Path for Alzheimer's Disease (CPAD) consortium created a first-of-its-kind partnership to share data from Alzheimer's clinical trials. CPAD 's partners include pharmaceutical companies, nonprofit foundations and government advisers. CPAD was formerly called the Coalition Against Major Diseases.

CPAD also has collaborated with the Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium to create data standards. Researchers think that data standards and sharing data from thousands of study participants will speed development of more-effective therapies.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Treatments and research. Alzheimer's Association. https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/research_progress/treatment-horizon. Accessed March 23, 2023.

- Cummings J, et al. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2022. Alzheimer's and Dementia. 2022; doi:10.1002/trc2.12295.

- Burns S, et al. Therapeutics of Alzheimer's disease: Recent developments. Antioxidants. 2022; doi:10.3390/antiox11122402.

- Plascencia-Villa G, et al. Lessons from antiamyloid-beta immunotherapies in Alzheimer's disease. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2023; doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-85555-6.00019-9.

- Brockmann R, et al. Impacts of FDA approval and Medicare restriction on antiamyloid therapies for Alzheimer's disease: Patient outcomes, healthcare costs and drug development. The Lancet Regional Health. 2023; doi:10.1016/j.lana. 2023.100467 .

- Wojtunik-Kulesza K, et al. Aducanumab — Hope or disappointment for Alzheimer's disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; doi:10.3390/ijms24054367.

- Can Alzheimer's disease be prevented? Alzheimer's Association. http://www.alz.org/research/science/alzheimers_prevention_and_risk.asp. Accessed March 23, 2023.

- Piscopo P, et al. A systematic review on drugs for synaptic plasticity in the treatment of dementia. Ageing Research Reviews. 2022; doi:10.1016/j.arr. 2022.101726 .

- Facile R, et al. Use of Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium (CDISC) standards for real-world data: Expert perspectives from a qualitative Delphi survey. JMIR Medical Informatics. 2022; doi:10.2196/30363.

- Imbimbo BP, et al. Role of monomeric amyloid-beta in cognitive performance in Alzheimer's disease: Insights from clinical trials with secretase inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies. Pharmacological Research. 2023; doi:10.1016/j.phrs. 2022.106631 .

- Conti Filho CE, et al. Advances in Alzheimer's disease's pharmacological treatment. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2023; doi:10.3389/fphar. 2023.1101452 .

- Potter H, et al. Safety and efficacy of sargramostim (GM-CSF) in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's and Dementia. 2021; doi:10.1002/trc2.12158.

- Zhong H, et al. Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists on cognitive function: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biomedicines. 2023; doi:10.3390/biomedicines11020246.

- Grodstein F. Estrogen and cognitive function. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed March 23, 2023.

- Mills ZB, et al. Is hormone replacement therapy a risk factor or a therapeutic option for Alzheimer's disease? International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023; doi:10.3390/ijms24043205.

- Custodia A, et al. Biomarkers assessing endothelial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease. Cells. 2023; doi:10.3390/cells12060962.

- Overview. Critical Path for Alzheimer's Disease. https://c-path.org/programs/cpad/. Accessed March 29, 2023.

- Shi M, et al. Impact of anti-amyloid-β monoclonal antibodies on the pathology and clinical profile of Alzheimer's disease: A focus on aducanumab and lecanemab. Frontiers in Aging and Neuroscience. 2022; doi:10.3389/fnagi. 2022.870517 .

- Leqembi (approval letter). Biologic License Application 761269. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=761269. Accessed July 7, 2023.

- Van Dyck CH, et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer's disease. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2212948.

- Leqembi (prescribing information). Eisai; 2023. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&varApplNo=761269. Accessed July 10, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Alzheimer's Disease

- Assortment of Products for Independent Living from Mayo Clinic Store

- A Book: Day to Day: Living With Dementia

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Healthy Aging

- Give today to find Alzheimer's cures for tomorrow

- Alzheimer's sleep problems

- Alzheimer's 101

- Understanding the difference between dementia types

- Alzheimer's disease

- Alzheimer's drugs

- Alzheimer's genes

- Alzheimer's prevention: Does it exist?

- Alzheimer's stages

- Antidepressant withdrawal: Is there such a thing?

- Antidepressants and alcohol: What's the concern?

- Antidepressants and weight gain: What causes it?

- Antidepressants: Can they stop working?

- Antidepressants: Side effects

- Antidepressants: Selecting one that's right for you

- Antidepressants: Which cause the fewest sexual side effects?

- Anxiety disorders

- Atypical antidepressants

- Caregiver stress

- Clinical depression: What does that mean?

- Corticobasal degeneration (corticobasal syndrome)

- Depression and anxiety: Can I have both?

- Depression, anxiety and exercise

- What is depression? A Mayo Clinic expert explains.

- Depression in women: Understanding the gender gap

- Depression (major depressive disorder)

- Depression: Supporting a family member or friend

- Diagnosing Alzheimer's

- Did the definition of Alzheimer's disease change?

- How your brain works

- Intermittent fasting

- Lecanemab for Alzheimer's disease

- Male depression: Understanding the issues

- MAOIs and diet: Is it necessary to restrict tyramine?

- Marijuana and depression

- Mayo Clinic Minute: 3 tips to reduce your risk of Alzheimer's disease

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Alzheimer's disease risk and lifestyle

- Mayo Clinic Minute: New definition of Alzheimer's changes

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Women and Alzheimer's Disease

- Memory loss: When to seek help

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs)

- Natural remedies for depression: Are they effective?

- Nervous breakdown: What does it mean?

- New Alzheimers Research

- Pain and depression: Is there a link?

- Phantosmia: What causes olfactory hallucinations?

- Positron emission tomography scan

- Posterior cortical atrophy

- Seeing inside the heart with MRI

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Sundowning: Late-day confusion

- Treatment-resistant depression

- Tricyclic antidepressants and tetracyclic antidepressants

- Video: Alzheimer's drug shows early promise

- Vitamin B-12 and depression

- Young-onset Alzheimer's

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Alzheimer s treatments What s on the horizon

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

Lecanemab, the New Alzheimer’s Treatment: 3 Things To Know

BY CARRIE MACMILLAN July 24, 2023

Yale researcher discusses the recent FDA approval of a new Alzheimer's disease treatment.

[Originally published January 19, 2023. Updated: July 24, 2023.]

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently granted full approval to a new Alzheimer’s treatment called lecanemab, which has been shown to moderately slow cognitive and functional decline in early-stage cases of the disease.

Alzheimer’s disease is a progressive disorder that damages and destroys nerve cells in the brain. Over time, the disease leads to a gradual loss of cognitive functions, including the ability to remember, reason, use language, and recognize familiar places. It can also cause a range of behavioral changes.

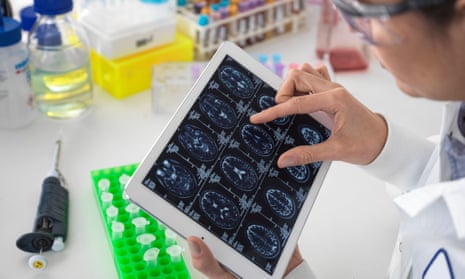

In January, the FDA gave the medication an accelerated approval based on amyloid plaque clearance. Christopher van Dyck, MD , director of Yale’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Unit, was the lead author of a study published in the Jan. 5 issue of The New England Journal of Medicine that shared results of a Phase III clinical trial of lecanemab. (Dr. van Dyck is also a paid consultant for the pharmaceutical company Eisai, which funded the trials.)

Sold under the brand name Leqembi™ and made by Eisai in partnership with Biogen Inc., the drug is delivered by an intravenous infusion every two weeks. Lecanemab works by removing a sticky protein from the brain that is believed to cause Alzheimer’s disease to advance.

“It’s very exciting because this is the first treatment in our history that shows an unequivocal slowing of decline in Alzheimer’s disease,” says Dr. van Dyck.

This is the first time in two decades that the FDA has granted full approval to a drug for Alzheimer’s, but there is also a “black box” warning on the medication—the agency’s strongest caution—because of safety concerns.

We talked more with Dr. van Dyck, who answered three questions about the new treatment.

How effective is lecanemab for Alzheimer’s disease?

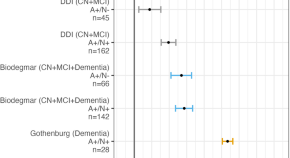

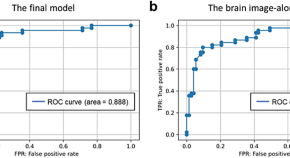

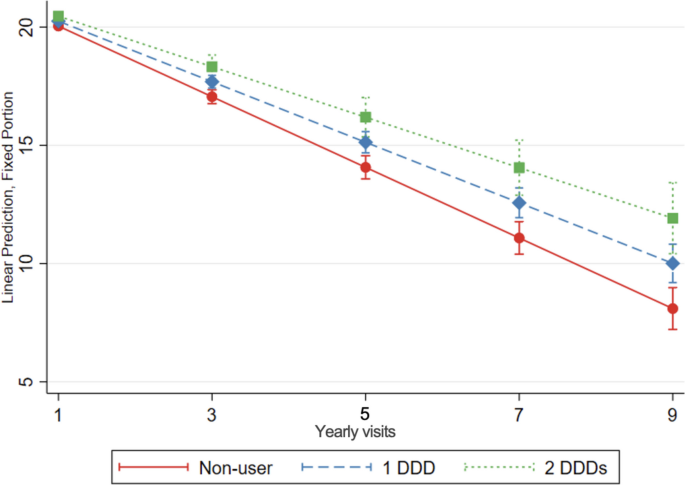

In a trial that involved 1,795 participants with early-stage, symptomatic Alzheimer’s, lecanemab slowed clinical decline by 27% after 18 months of treatment compared with those who received a placebo.

“The antibody treatment selectively targets the forms of amyloid protein that are thought to be the most toxic to brain cells,” says Dr. van Dyck.

Study participants who received the treatment had a significant reduction in amyloid burden in imaging tests, usually reaching normal levels by the end of the trial. Participants also showed a 26% slowing of decline in a key secondary measure of cognitive function and a 37% slowing of decline in a measure of daily living compared to the placebo group.

“Would I like the numbers to be higher? Of course, but I don’t think this is a small effect,” says Dr. van Dyck. “These results could also indicate a starting point for bigger effects. The data appear encouraging that the longer the treatment period, the better the effect. But we’ll need more studies to determine if that’s true.”

They also beg the question about still-earlier intervention, adds Dr. van Dyck. Lecanemab is already being tested in the global AHEAD study for individuals who are still cognitively normal but at high risk of symptoms due to elevated levels of brain amyloid.

Yale currently has the largest number of participants in the AHEAD study, which is funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Eisai and is enrolling participants as young as 55. “We may see a larger benefit if we intervene before significant brain damage has occurred,” he says.

Is lecanemab safe?

The most common side effect (26.4% of participants vs. 7.4% in the placebo group) of the treatment is an infusion-related reaction, which may include transient symptoms, such as flushing, chills, fever, rash, and body aches. The majority (96%) of these reactions were mild to moderate, and 75% happened after the first dose.

“We can medicate those individuals in advance if we find they have those side effects repeatedly,” says Dr. van Dyck. “We can use medications such as diphenhydramine or acetaminophen. But this is generally not an issue.”

Another potential side effect associated with lecanemab was amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with edema, or fluid formation on the brain. This occurred in 12.6% of trial participants compared to 1.7% in the placebo group. “It’s usually asymptomatic when it occurs, but we can detect it on MRI scans. We often don’t stop dosing if we see it, unless there are symptoms, in which case we would pause infusions until it fully resolves,” Dr. van Dyck says.

It’s important to note that the studies with lecanemab show substantially lower rates of this side effect than do published trials of other, similar drugs such as aducanumab—they're at about a third of the rate, explains Dr. van Dyck. “So, for drugs in this class, I think lecanemab has a favorable safety profile,” he says.

Lastly, 17.3% of trial participants experienced amyloid-related imaging abnormalities with brain bleeding compared to 9% in the placebo group.

“Most of the time we're really talking about microhemorrhages that are in the order of millimeters,” says Dr. van Dyck. “People with Alzheimer's disease are more prone to these events because of the amyloid deposits in their blood vessels, but a catastrophic bleed is quite rare.”

The medication’s label includes warnings about brain swelling and bleeding and that people with a gene mutation that increases their risk of Alzheimer’s disease are at greater risk of brain swelling on the treatment. The label also cautions against taking blood thinners while on the medication.

When will lecanemab be available for Alzheimer’s disease treatment?

Eisai set the price for Leqembi at $26,500 per year, and it has reportedly been largely unavailable while FDA full approval was pending. That may change now that Medicare has said it will cover 80% of the cost.

More news from Yale Medicine

How to stay connected with a loved one with alzheimer’s disease.

How Anti-Obesity Medications Can Help With Surgery

3 Things to Know About JN.1, the New Coronavirus Strain

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

A molecular ‘warhead’ against disease

Asking the internet about birth control

‘Harvard Thinking’: Facing death with dignity

Start of new era for alzheimer’s treatment.

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Expert discusses recent lecanemab trial, why it appears to offer hope for those with deadly disease

Researchers say we appear to be at the start of a new era for Alzheimer’s treatment. Trial results published in January showed that for the first time a drug has been able to slow the cognitive decline characteristic of the disease. The drug, lecanemab, is a monoclonal antibody that works by binding to a key protein linked to the malady, called amyloid-beta, and removing it from the body. Experts say the results offer hope that the slow, inexorable loss of memory and eventual death brought by Alzheimer’s may one day be a thing of the past.

The Gazette spoke with Scott McGinnis , an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and Alzheimer’s disease expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital , about the results and a new clinical trial testing whether the same drug given even earlier can prevent its progression.

Scott McGinnis

GAZETTE: The results of the Clarity AD trial have some saying we’ve entered a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment. Do you agree?

McGINNIS: It’s appropriate to consider it a new era in Alzheimer’s treatment. Until we obtained the results of this study, trials suggested that the only mode of treatment was what we would call a “symptomatic therapeutic.” That might give a modest boost to cognitive performance — to memory and thinking and performance in usual daily activities. But a symptomatic drug does not act on the fundamental pathophysiology, the mechanisms, of the disease. The Clarity AD study was the first that unambiguously suggested a disease-modifying effect with clear clinical benefit. A couple of weeks ago, we also learned a study with a second drug, donanemab, yielded similar results.

GAZETTE: Hasn’t amyloid beta, which forms Alzheimer’s characteristic plaques in the brain and which was the target in this study, been a target in previous trials that have not been effective?

McGINNIS: That’s true. Amyloid beta removal has been the most widely studied mechanism in the field. Over the last 15 to 20 years, we’ve been trying to lower beta amyloid, and we’ve been uncertain about the benefits until this point. Unfavorable results in study after study contributed to a debate in the field about how important beta amyloid is in the disease process. To be fair, this debate is not completely settled, and the results of Clarity AD do not suggest that lecanemab is a cure for the disease. The results do, however, provide enough evidence to support the hypothesis that there is a disease-modifying effect via amyloid removal.

GAZETTE: Do we know how much of the decline in Alzheimer’s is due to beta amyloid?

McGINNIS: There are two proteins that define Alzheimer’s disease. The gold standard for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease is identifying amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles. We know that amyloid beta plaques form in the brain early, prior to accumulation of tau and prior to changes in memory and thinking. In fact, the levels and locations of tau accumulation correlate much better with symptoms than the levels and locations of amyloid. But amyloid might directly “fuel the fire” to accelerated changes in tau and other downstream mechanisms, a hypothesis supported by basic science research and the findings in Clarity AD that treatment with lecanemab lowered levels of not just amyloid beta but also levels of tau and neurodegeneration in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid.

GAZETTE: In the Clarity AD trial, what’s the magnitude of the effect they saw?

McGINNIS: The relevant standards in the trial — set by the FDA and others — were to see two clinical benefits for the drug to be considered effective. One was a benefit on tests of memory and thinking, a cognitive benefit. The other was a benefit in terms of the performance in usual daily activities, a functional benefit. Lecanemab met both of these standards by slowing the rate of decline by approximately 25 to 35 percent compared to placebo on measures of cognitive and functional decline over the 18-month studies.

“In a perfect world, we’d have treatments that completely stop decline and even restore function. We’re not there yet, but this represents an important step toward that goal.”

Steven M. Smith

GAZETTE: What are the key questions that remain?

McGINNIS: An important question relates to the stages at which the interventions were done. The study was done in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer dementia. People who have mild cognitive impairment have retained their independence in instrumental activities of daily living — for example, driving, taking medications, managing finances, errands, chores — but have cognitive and memory changes beyond what we would attribute to normal aging. When people transition to mild dementia, they’re a bit further along. The study was for people within that spectrum but there’s some reason to believe that intervening even earlier might be more effective, as is the case with many other medical conditions.

We’re doing a study here called the AHEAD study that is investigating the effects of lecanemab when administered earlier, in cognitively normal individuals who have elevated brain amyloid, to see whether we see a preventative benefit. The hope is that we would at least see a delay to onset of cognitive impairment and a favorable effect not only on amyloid biomarkers, but other biomarkers that might capture progression of the disease.

GAZETTE: Is anybody in that study treatment yet or are you still enrolling?

McGINNIS: There’s a rolling enrollment, so there are people who are in the double-blind phase of treatment, receiving either the drug or the placebo. But the enrollment target hasn’t been reached yet so we’re still accepting new participants.

GAZETTE: Is it likely that we may see drug cocktails that go after tau and amyloid? Is that a future approach?

More like this

Newly identified genetic variant protects against Alzheimer’s

Using AI to target Alzheimer’s

Excessive napping and Alzheimer’s linked in study

McGINNIS: It has not yet been tried, but those of us in the field are very excited at the prospect of these studies. There’s been a lot of work in recent years on developing therapeutics that target tau, and I think we’re on the cusp of some important breakthroughs. This is key, considering evidence that spreading of tau from cell to cell might contribute to progression of the disease. Additionally, for some time, we’ve had a suspicion that we will likely have to target multiple different aspects of the disease process, as is the case with most types of cancer treatment. Many in our field believe that we will obtain the most success when we identify the most pertinent mechanisms for subgroups of people with Alzheimer’s disease and then specifically target those mechanisms. Examples might include metabolic dysfunction, inflammation, and problems with elements of cellular processing, including mitochondrial functioning and processing old or damaged proteins. Multi-drug trials represent a natural next step.

GAZETTE: What about side effects from this drug?

McGINNIS: We’ve known for a long time that drugs in this class, antibodies that harness the power of the immune system to remove amyloid, carry a risk of causing swelling in the brain. In most cases, it’s asymptomatic and just detected by MRI scan. In Clarity AD, while 12 to 13 percent of participants receiving lecanemab had some level of swelling detected by MRI, it was symptomatic in only about 3 percent of participants and mild in most of those cases.

Another potential side effect is bleeding in the brain or on the surface of the brain. When we see bleeding, it’s usually very small, pinpoint areas of bleeding in the brain that are also asymptomatic. A subset of people with Alzheimer’s disease who don’t receive any treatment are going to have these because they have amyloid in their blood vessels, and it’s important that we screen for this with an MRI scan before a person receives treatment. In Clarity AD, we saw a rate of 9 percent in the placebo group and about 17 percent in the treatment group, many of those cases in conjunction with swelling and mostly asymptomatic.

The scenario that everybody worries about is a hemorrhagic stroke, a larger area of bleeding. That was much less common in this study, less than 1 percent of people. Unlike similar studies, this study allowed subjects to be on anticoagulation medications, which thin the blood to prevent or treat clots. The rate of macro hemorrhage — larger bleeds — was between 2 and 3 percent in the anticoagulated participants. There were some highly publicized cases including a patient who had a stroke, presented for treatment, received a medication to dissolve clots, then had a pretty bad hemorrhage. If the drug gets full FDA approval, is covered by insurance, and becomes clinically available, most physicians are probably not going to give it to people who are on anticoagulation. These are questions that we’ll have to work out as we learn more about the drug from ongoing research.

GAZETTE: Has this study, and these recent developments in the field, had an effect on patients?

McGINNIS: It has had a considerable impact. There’s a lot of interest in the possibility of receiving this drug or a similar drug, but our patients and their family members understand that this is not a cure. They understand that we’re talking about slowing down a rate of decline. In a perfect world, we’d have treatments that completely stop decline and even restore function. We’re not there yet, but this represents an important step toward that goal. So there’s hope. There’s optimism. Our patients, particularly patients who are at earlier stages of the disease, have their lives to live and are really interested in living life fully. Anything that can help them do that for a longer period of time is welcome.

Share this article

You might like.

Approach attacks errant proteins at their roots

Only a fraction of it will come from an expert, researchers say

In podcast episode, a chaplain, a bioethicist, and a doctor talk about end-of-life care

Forget ‘doomers.’ Warming can be stopped, top climate scientist says

Michael Mann points to prehistoric catastrophes, modern environmental victories

Yes, it’s exciting. Just don’t look at the sun.

Lab, telescope specialist details Harvard eclipse-viewing party, offers safety tips

Navigating Harvard with a non-apparent disability

4 students with conditions ranging from diabetes to narcolepsy describe daily challenges that may not be obvious to their classmates and professors

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Cent Nerv Syst Dis

Current and Future Treatments in Alzheimer Disease: An Update

Konstantina g yiannopoulou.

1 Memory Center, Neurological Department, Henry Dunant Hospital Center, Athens, Greece

Sokratis G Papageorgiou

2 Cognitive Disorders/Dementia Unit, 2nd Neurological Department, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Attikon General University Hospital, Athens, Greece

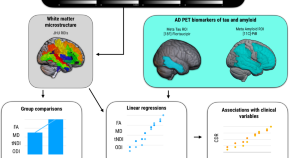

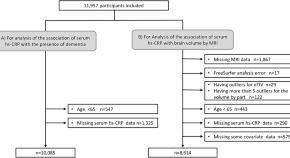

Disease-modifying treatment strategies for Alzheimer disease (AD) are still under extensive research. Nowadays, only symptomatic treatments exist for this disease, all trying to counterbalance the neurotransmitter disturbance: 3 cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine. To block the progression of the disease, therapeutic agents are supposed to interfere with the pathogenic steps responsible for the clinical symptoms, classically including the deposition of extracellular amyloid β plaques and intracellular neurofibrillary tangle formation. Other underlying mechanisms are targeted by neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, growth factor promotive, metabolic efficacious agents and stem cell therapies. Recent therapies have integrated multiple new features such as novel biomarkers, new neuropsychological outcomes, enrollment of earlier populations in the course of the disease, and innovative trial designs. In the near future different specific agents for every patient might be used in a “precision medicine” context, where aberrant biomarkers accompanied with a particular pattern of neuropsychological and neuroimaging findings could determine a specific treatment regimen within a customized therapeutic framework. In this review, we discuss potential disease-modifying therapies that are currently being studied and potential individualized therapeutic frameworks that can be proved beneficial for patients with AD.

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD) is one of the greatest medical care challenges of our century and is the main cause of dementia. In total, 40 million people are estimated to suffer from dementia throughout the world, and this number is supposed to become twice as much every 20 years, until approximately 2050. 1

Because dementia occurs mostly in people older than 60 years, the growing expansion of lifespan, leading to a rapidly increasing number of patients with dementia, 2 mainly AD, has led to an intensive growth in research focused on the treatment of the disease. However, despite all arduous research efforts, at the moment, there are no effective treatment options for the disease. 3 , 4

The basic pathophysiology and neuropathology of AD that drives the current research suggests that the primary histopathologic lesions of AD are the extracellular amyloid plaques and the intracellular Tau neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs). 5 The amyloid or senile plaques (SPs) are constituted chiefly of highly insoluble and proteolysis-resistant peptide fibrils produced by β-amyloid (Aβ) cleavage. Aβ peptides with Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42 as the most common variants are produced after the sequential cleavage of the large precursor protein amyloid precursor protein (APP) by the 2 enzymes, β-secretase (BACE1) and γ-secretase. Nevertheless, Aβ is not formed if APP is first acted on and cleaved by the enzyme α-secretase instead of β-secretase. 6 According to the “amyloid hypothesis” Aβ production in the brain initiates a cascade of events leading to the clinical syndrome of AD. It is the forming of amyloid oligomers to which neurotoxicity is mainly attributed and initiates the amyloid cascade. The elements of the cascade include local inflammation, oxidation, excitoxicity (excessive glutamate), and tau hyperphosphorylation. 5 Tau protein is a microtubule-associated protein which binds microtubules in cells to facilitate the neuronal transport system. Microtubules also stabilize growing axons necessary for neuronal development and function. Abnormally hyperphosphorylated tau forms insoluble fibrils and folds into intraneuronic tangles. Consequently, it uncouples from microtubules, inhibits transport, and results in microtubule disassembly. 6 Although in the amyloid hypothesis, tau hyperphosphorylation was thought to be a downstream event of Aβ deposition, it is equally probable that tau and Aβ act in parallel pathways causing AD and enhancing each other’s toxic effects. 3 Progressive neuronal destruction leads to shortage and imbalance between various neurotransmitters (eg, acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin) and to the cognitive deficiencies seen in AD. 5

All of the already established treatments that are used today try to counterbalance the neurotransmitter imbalance of the disease. The acetylocholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) which are approved for the treatment of AD are donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine. 4 , 5 Their development was based in the cholinergic hypothesis which suggests that the progressive loss of limbic and neocortical cholinergic innervation in AD is critically important for memory, learning, attention, and other higher brain functions decline. Furthermore, neurofibrillary degeneration in the basal forebrain is probably the primary cause for the dysfunction and death of cholinergic neurons in this region, giving rise to a widespread presynaptic cholinergic denervation. The AChEIs increase the availability of acetylcholine at synapses and have been proven clinically useful in delaying the cognitive decline in AD. 7

A further therapeutic agent approved for moderate to severe AD is the low-to-moderate affinity, noncompetitive N -methyl- d -aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist memantine. 4 , 5 Memantine binds preferentially to open NMDA receptor–operated calcium channels blocking NMDA-mediated ion flux and ameliorating the dangerous effects of pathologically elevated glutamate levels that lead to neuronal dysfunction. 8

In clinical trials, both Aβ and tau are prime targets for disease-modifying treatments (DMTs) in AD. From this point of view, AD could be prevented or effectively treated by decreasing the production of Aβ and tau; preventing aggregation or misfolding of these proteins; neutralizing or removing the toxic aggregate or misfolded forms of these proteins; or a combination of these modalities. 7

A number of additional pathogenic mechanisms have been described, possibly overlapping with Aβ plaques and NFT formation or induced by them, including inflammation, oxidative damage, iron deregulation, and cholesterol metabolism blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction or α-synuclein toxicity. 9 - 13

This article will review current nonpharmacological and pharmacological management of the cognitive and behavioral symptoms of AD, with a focus on the medications that are currently FDA (Food and Drug Administration)–approved for the treatment of the cognitive and functional deficits of AD. 10 Pharmacological agents under research in phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials in AD will be summarized. 11 - 13

Current management of AD

A multifactorial tailored management of AD is attempted nowadays based in the following components:

- Open physician, caregiver, and patient communication: a sincere and successful conveying of information and feelings between them will offer opportune identifying of symptoms, exact evaluation and diagnosis, and suitable guidance.

- - Consistency and simplification of environment 10 ;

- - Established routines 10 ;

- - Communicative strategies such as calm interactions, providing pleasurable activities, using simple language and “saying no” only when safety is concerned 10 ;

- - Timely planning for legal and medical decisions and needs 10 ;

- - Cognitive behavioral therapy 14 , 15 ;

- - Exercise therapy, light therapy, music therapy. 14 , 15

- - Planned short rest periods for the caregiver;

- - Psychoeducation including preparing for effects of dementia on cognition, function and behaviors, expectations, avoiding situations that can worsen the symptoms or increasing the dangers for safety and well-being

- - Encouraging the development of support networks for the caregivers. 10

- Pharmacological interventions.

FDA-approved AD medications

The AChEIs donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and the NMDA antagonist memantine are the only FDA-approved AD medications. 10

AChEIs attempt at reducing the breakdown of acetylcholine levels in the brain of the patients with AD by inhibiting the responsible enzyme acetylcholinesterase in the synaptic cleft. 5 Thus, AChEIs enhance central cholinergic neurotransmission and finally tend to mitigate decline in cognition at least during the first year of treatment. Further decline occurs, but even temporary discontinuation of these drugs results in rapid decline and is associated with greater risk of nursing home placement. 16

Initiation of AChEI treatment as soon as possible after the diagnosis is preferred as patients who started the AChEI 6 months later showed more rapid cognitive decline than those who started the drug immediately. 17 All 3 AChEIs have proved their treatment benefits in delaying decline, stabilizing, or even improving cognition and activities of daily living in randomized placebo-controlled trials up to 52 weeks duration. 10 , 18 Longer term open-label extension studies support also longer term treatment benefits. 10

Significant efficacy differences among the AChEIs have not been reported. Donepezil and rivastigmine have been approved by FDA for mild, moderate, and severe AD, whereas galantamine for mild and moderate AD. 18

The most common adverse effects are triggered by the cholinomimetic action of the AChEIs on the gastrointestinal tract and often include diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder has been also remarked in some individuals. Administration of the drug after a meal in the morning can minimize all of these adverse effects. The transdermal patch of rivastigmine can induce rash at the site of application. Adverse effects affect usually a 5% to 20% of patients but are mostly transient and mild. The AChEIs may also trigger bradycardia and increase the risk of syncope. Thus, AChEIs are contraindicated in conditions including severe cardiac arrhythmias, especially bradycardia or syncope. They are also contraindicated in active peptic ulcer or gastrointestinal bleeding history and uncontrolled seizures. Slow titration over months to years to a maximal tolerated of the indicated dose is important for the safety of the patients. 17 , 18

Pharmacokinetic characteristics differ among AChEIs: the primary route of elimination for donepezil and galantamine is hepatic metabolism, whereas for rivastigmine is liver and intestine metabolism. Donepezil and galantamine inhibit selectively and reversibly the acetylcholinesterase, whereas rivastigmine is a “pseudo-irreversible” inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase. Donepezil has a long elimination half-life of 70 hours and galantamine of 6 to 8 hours. The elimination half-life of rivastigmine is very short (1-2 hours for oral and 3-4 hours for transdermal administration), but the duration of action is longer as acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase are blocked for around 8.5 and 3.5 hours, respectively. 10 , 17 , 18

Memantine is a noncompetitive low-affinity NMDA-receptor open-channel blocker and affects glutamatergic transmission. 5 Its main elimination route is unchanged via the kidneys with a half-life of 70 hours. It has been approved by FDA for moderate and severe AD either as monotherapy or in combination with an AChEI. 3 Memantine monotherapy has demonstrated short- and long-term benefits for patients with moderate to severe AD as assessed by different scales evaluating activities of daily living, cognition, and behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD). 19

Memantine can be administered in combination with an AChEI, as they have complementary mechanisms of action. Their combination benefits patients with usually additive effects, without any increase in adverse effects. 14 , 15

Duration and persistence of monotherapy or combination treatment with higher doses in moderate or even in advanced dementia are associated with better global function and outcomes. 20

Medications for BPSD

Antipsychotics and antidepressants remain the main medications for BPSD. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors are preferred for treating depression and anxiety. Drugs with low anticholinergic effects and an acceptable tolerability, such as sertraline, citalopram, and escitalopram, are more appropriate. Antipsychotics should be administered only when a significant safety risk for the patient or for the caregivers by aggressive behaviors makes them necessary. Controversial and limited evidence cannot adequately support the use of benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants stimulants, or dextromethorphan/quinidine. Pharmacological approaches to managing BPSD are highly individualized and changeable, depending on patient’s comorbidities, stage of the disease, and symptoms’ severity. 21

Removal of superfluous and deleterious medications

Polypharmacy in older patients with dementia is usual (with a prevalence of 25%-98%). 22 Anticholinergics and sedatives are commonly used inappropriate medications. These drugs are prescribed despite strong evidence (Beers Criteria) that they should be avoided in cognitively vulnerable older persons because of their potential adverse cognitive effects. 23 Estrogen is another commonly prescribed potentially inappropriate medication despite evidence that its use is associated with increased cognitive decline in postmenopausal women. 24

Specific examples of usually prescribed potentially harmful medications in the elderly are diphenhydramine, often taken with acetaminophen for insomnia and pain, benzodiazepines for anxiety, anticholinergics (tolderodine, oxybutynin, tamsulosin) for urinary incontinence, biperiden, and pramipexole for extrapyramidal tremor 25 and sedative/hypnotics for sleep disorders. 26

Treating underlying medical conditions

Careful management of vascular risk factors (hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hypertension) is of paramount importance for patients with AD. Hydration, sleep, and nutrition status should also be closely monitored. Disorders in thyroid function or electrolytes, deficiencies in vitamin B 12 , folate, vitamin D, or systemic conditions and diseases that can affect cognition (infections, eg, urinary tract infection, pain, constipation) should be treated. 27

Current Landscape in Treatment Research for AD

No new drug has been approved by FDA for AD since 2003 and there are no approved DMTs for AD, despite many long and expensive trials. 22 , 28 As a matter of fact, more than 200 research projects in the last decade have failed or have been abandoned. 10 Nevertheless, drug pipeline for AD is still full of agents with mechanisms of action (MOA) that target either disease modification or symptoms. 4 , 10 Some of the recent failures of anti-amyloid agents in phase 3 clinical trials in patients with early-stage, mild, or mild-to-moderate stage AD were semagacestat, 29 bapineuzumab, 30 solanezumab 31 and in similar trials of β-secretase inhibitors (BACE) lanabecestat, 32 verubecestat, 33 and atabecestat. 34

The most popular and broadly accepted explanations for the multiple failures of clinical trials of DMT agents for AD include the too late starting of therapies in disease development, the inappropriate drug doses, the wrong main target of the treatment, and mainly an inadequate understanding of the pathophysiology of AD. 35 A novel approach to the problem seems more technical and mathematical than biological and suggests that the selected trials’ clinical endpoint may be extremely premature, and additionally, the variability in diagnostic markers and end points may result in inaccurate diagnosis of patients’ disease state and is finally a definite source of errors. 28 Given the fact that longer trial durations increase the probability of detecting a significant effect but at the same time increase tremendously the costs, the proposed solution seems to be the use of clinical trial simulators. 28 These simulators are constructed with mathematical, computational, and statistical tools and can predict the likelihood that a strategy and clinical end point selection of a given trial are proper or not, before the initiation of the trial. 36 They can also help in the perfecting of the design of the study; hence, they may augment the probability of success of estimated new drugs or save invaluable time and resources, by indicating earlier the forthcoming failure of any inappropriate therapy. 37 Although the use of clinical trial simulators is not frequent in recent research, 38 should this practice be abandoned, especially when potential treatments for diseases with slow progression and long duration, such as AD, are evaluated. 37

At the same time, current research remains focused on the development of therapeutic approaches to slow or stop the disease progression, taking into consideration every new aspect in the biology of the disease, the diagnostic markers, and the precise diagnosis of disease state of every individual and the design of clinical trials. Furthermore, drug development research for AD has become more complicated as preclinical and prodromal AD populations are potentially included in current trials, as well as traditionally included populations of all the clinical stages of AD dementia. 38 Consequently, current guidance provided by the FDA for AD clinical trials further includes use of fluid or neuroradiological biomarkers in disease staging for preclinical and prodromal AD trials and of a single primary outcome in prodromal AD trials. In addition, the use of clinical trial simulators, Bayesian statistics, and modifiable trial designs is strongly suggested. 4

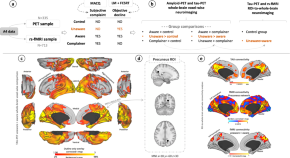

The National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association (NIA-AA) proposed a new framework for research, 39 which requires the application of amyloid, tau, and neurodegeneration biomarkers to clinical trials, succeeds in precise classification of patients in AD stages, and can be used to assist clinical trials design.

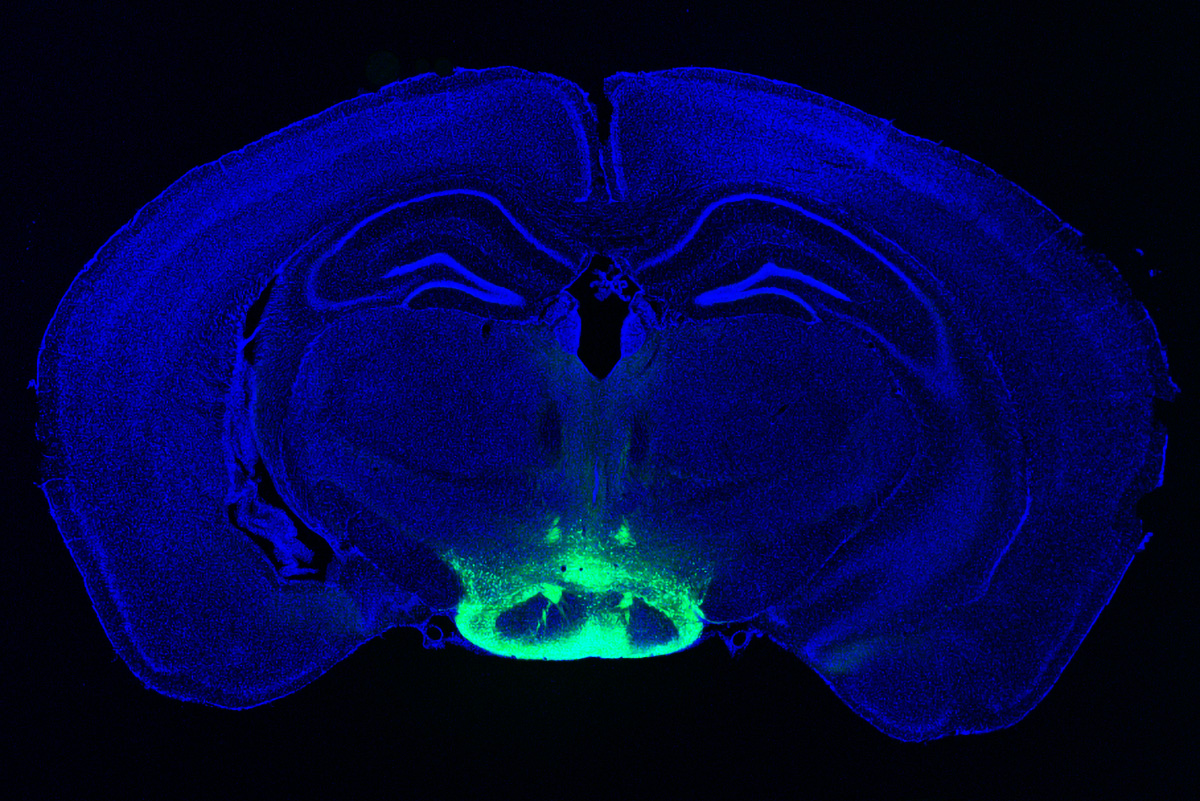

Tau positron emission tomography (tau PET), neurofilament light, and neurogranin are the new biomarkers that are increasingly used by clinical trials. 40

The above-mentioned biological and statistical advances that are recently integrated in clinical trials may comprise the final assets for succeeding in drug development. The current clinical trials in AD in phases 1, 2, and 3 4 , 11 - 13 are briefly discussed. The tested agents in these trials are classified either as potentially modifying the disease or as symptomatic for the cognitive enhancement, and for the relief of neuropsychiatric symptoms. The new directions in AD clinical trials, such as agents with novel MOA, advanced immunotherapies, the involvement of biomarkers in drug development, and repurposed agents, are highlighted.

A search for phases 1, 2, and 3 “recruiting” or “active but not recruiting” clinical trials for AD in clinicaltrials.gov (accessed August 19, 2019) showed 165 outcomes. The last annual review of the drug development pipeline for AD examined clinicaltrials.gov in February, 2019 (132 agents in 156 trials) and provides information and conclusions available at that time: 28 drugs in 42 clinical trials in phase 3 trials, 74 drugs in 83 phase 2 trials, and 30 drugs in 31 phase 1 trials. 4 The tested agents are classified as DMTs (73%), symptomatic cognitive enhancers (13%), and symptomatic for the treatment of BPSDs (11%). 4 The DMT agents were further separated into small molecules or biologics (monoclonal antibodies [mAbs] and other immunotherapies). The DMT agents were also classified according to their potential MOA as amyloid targeting, as tau-related targeting, and as having other MOA such as anti-inflammatory or metabolic protection, neuroprotection, and growth factor support. 4 The DMTs are suggested to be effective to delay or halt disease progression that would be expressed clinically with long-lasting benefits in cognition over many months to years. Symptomatic agents are supposed to show symptomatic benefits over weeks to many months in cognition improvement or BPSD elimination. 10

In this review, agents currently studied as potential DMTs will be discussed. Furthermore, an approach to a future “precision medicine” multifactorial therapeutic model based on biomarkers profile, genetic analysis, neuropsychologic evaluation, and neuroimaging accomplished with risk factors restriction will be attempted. 2 , 3

Currently studied DMTs for AD

Amyloid-related mechanisms—dmts.

The crucial step in AD pathogenesis is the production of amyloid (Aβ), which forms SPs (insoluble and proteolysis-resistant fibrils). The Aβ derives from a protein overexpressed in AD, APP through sequential proteolysis by β-secretase (BACE1) in the extracellular domain and γ-secretase in the transmembrane region. Full-length APP is first cleaved by α-secretase or β-secretase. The APP cleavage by α-secretase leads to nonamyloidogenic pathway, whereas APP cleavage by β-secretase (BACE1) leads to amyloidogenic pathway. Sequential cleavage of APP by BACE1 in the extracellular and γ-secretase in the transmembrane area results in the Aβ production. Major sites of γ-secretase cleavage usually occur in positions 40 and 42 of Aβ, thus Aβ40 and Aβ42 oligomers are the main products of the sequential APP cleavage, as the amyloidogenic pathway is favored in neurons because of the greater plentifulness of BACE1. On the contrary, the nonamyloidogenic processing is more favored in other cells without BACE1 predominance. 5

“Amyloid hypothesis” suggests that Aβ production in the brain triggers a cascade of pathophysiologic events leading to the clinical expression of AD. Aβ is a protein consisting of 3 main isoforms: Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42. Aβ42 is the most aggregation-prone form and has the tendency to cluster into oligomers. Oligomers can form Aβ-fibrils that will eventually form amyloid plaques. Aβ40 is somewhat aggregation-prone and it is mostly found in the cerebral vasculature as a main component of “cerebral amyloid angiopathy.” Aβ40 usually constitutes more than 50% of total detected Aβ. Aβ38 is soluble, present in the vasculature of patients with sporadic and familial AD. Neurotoxicity is mainly attributed to the forming of amyloid oligomers, which finally initiates the amyloid cascade. 5

Oxidation, inflammation, excessive glutamate, and tau hyperphosphorylation are supposed to be the main pathophysiologic pillars of the cascade. Tau protein binds microtubules in cells to facilitate the neuronal transport system. Microtubules also stabilize growing axons. Hyperphosphorylated tau forms insoluble fibrils and folds into intraneuronic NFTs. Consequently, it inhibits neuronal transport and microtubule function. 2 Although in the initial amyloid hypothesis, tau hyperphosphorylation was thought to be a downstream event of Aβ deposition, it is now equally probable that tau and Aβ act in parallel pathways causing AD and enhancing each other’s toxic effects. 2 The result of massive neuronal destruction is the shortage and imbalance between neurotransmitters, such as acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin, and to the cognitive and behavioral symptoms of AD. 5

Consequently, anti-amyloid DMTs have focused on 3 major MOAs: (1) reduction of Aβ42 production (γ-secretase inhibitors, β-secretase inhibitors, α-secretase potentiation), (2) reduction of Aβ-plaque burden (aggregation inhibitors, drugs interfering with metals), and (3) promotion of Aβ clearance (active or passive immunotherapy). 10

Reduction of Aβ42 production

γ-secretase inhibitors.

According to the amyloid hypothesis, amyloidogenic pathway is promoted after the sequential cleavage of APP by BACE1 and γ-secretase. Consequently, the inhibition of these enzymes has been considered as a major therapeutic target. Unluckily, concerning γ-secretase, in addition to APP, this particular enzyme acts on many other substances and cleaves different transmembrane proteins. Notch receptor 1, which is essential for control of normal cell differentiation and communication, is among them. 5 This fact is probably responsible for recent failures in clinical trials with γ-secretase inhibitors: semagacestat 29 was associated with worsening of activities in daily leaving and increased rates of infections and skin cancer, avagacestat 41 was associated with higher rate of cognitive decline and adverse dose-limiting effects (skin cancer) and tarenflurbil which showed low brain penetration. 42 Serious safety concerns for γ-secretase inhibitors remove γ-secretase from the role of appropriate target for the treatment of AD 43 until in depth studies on this key enzyme could help to therapeutically target γ-secretase in a safe way. 44 No γ-secretase modulators are currently studied in phase 1-3 clinical trials. 4

BACE inhibitors

Two BACE inhibitors are still elaborated: elenbecestat (E2609) in phase 2 and umibecestat (CNP520) in phase 3. 4 The later agent is studied in asymptomatic individuals at risk of developing AD (APOE4 homozygotes or APOE4 heterozygotes with elevated amyloid, detected by cerebrospinal fluid [CSF] biomarkers or amyloid PET). 45

Fluid and neuroimaging biomarkers indicative of AD pathology or neurodegeneration are integrated in this study.

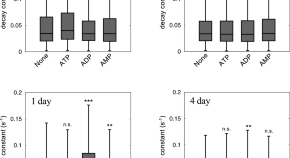

However, the clinical trials with the BACE inhibitors lanabecestat, 32 verubecestat, 33 and atabecestat 34 have been recently discontinued due to unexpected difficulties. The phase 3 lanabecestat trial was discontinued due to lack of efficacy, whereas verubecestat and atabecestat trials were ceased due to ineffectiveness, as well as safety reasons (rash, falls, liver toxicity, and neuropsychiatric symptoms). 10 , 32 - 34 All agents showed significant and dose-dependent result of reducing CSF Aβ42, but without cognitive or functional benefit while many of them were poorly tolerated and some of them failed in subjects with prodromal AD. These results might support the suggestion that blocking the process of forming of Aβ may be not capable of halting the disease progression. 46

α-secretase modulators

According to the amyloid hypothesis, nonamyloidogenic pathway is promoted after the cleavage of APP by α-secretase. Consequently, the modulation of the enzyme has been considered as a major therapeutic target. However, little is known of the main signaling pathways that could stimulate cleavage of APP by α-secretase. Restricted, nowadays, knowledge assumes that α-secretase activation is promoted through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway and may be through γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor signaling; thus, agents that activate the PI3K/Akt pathway or act as selective GABA receptor modulators are suggested as potential therapeutic drugs for AD. 47 , 48

Etazolate (EHT0202) stimulates the nonamyloidogenic α-secretase pathway acting as a selective modulator of GABA receptors. A previous, phase 2 trial has showed that the agent was safe and well tolerated in patients with mild to moderate AD. However, further evaluation of etazolate in phase 3 trials has not progressed. 48 Etazolate is currently evaluated in animal studies for its preventive effect in post-traumatic stress disorder. 49

Two α-secretase modulators that activate the PI3K/Akt pathway are studied in phase 2 clinical studies: APH-1105 and ID1201. APH-1105 is delivered intranasally and is assessed in mild to moderate AD. 4 ID1201 is a fruit extract of melia toosendan and also induces α-secretase activation. It is evaluated in mild AD. 47

Reduction of Aβ-plaque burden

Aggregation inhibitors (anti-amyloid aggregation agents).

Aggregation inhibitors interact directly with the Aβ peptide to inhibit Aβ42 fiber formation, thus they are considered potential therapeutic for AD.

The last Aβ42 aggregation inhibitor which was tested in humans was the oral agent scyllo-inositol (ELND005). A phase 2 clinical trial in patients with AD did not provide evidence to support a clinical benefit of ELND005 while severe toxicity issues (infections) forced the cessation of the study. Further development of the agent at a lower dose has not progressed in the last 8 years. 50

Nowadays, specific agents in the form of peptidomimetics that inhibit and partially reverse the aggregation of Aβ 42 are tested in transmission electron microscopic studies. KLVFF is a peptide sequence that resembles the hydrophobic central part of the Aβ and gradually replaces natural polypeptides. The KLVFF compound that mainly prevents the aggregation of Aβ 42 and can also dissolve the oligomerics to a limited extend is the final compound 18, which is resilient in proteolytic decomposition. 51

Another newly developed class of peptidomimetics are the “γ-AApeptides.” 52 One of them, compound γ-AA26, seems almost 100-fold as efficient as the compound 18 of the KLVFF in the inhibition of the aggregation of Aβ 42 . 52

In vivo animal studies will be developed to manifest the biological potential of peptidomimetics.

Reduction of Aβ-plaque burden via drugs interfering with metals

Abnormal accumulation or dyshomeostasis of metal ions such as iron, copper, and zinc has been associated with the pathophysiology of AD. 5

Deferiprone is an iron chelating agent which is studied in phase 2 trials in participants with mild and prodromal AD. 4 , 53

A metal protein–attenuating compound, PBT2, has recently progressed in phase 2 AD treatment trials, as it demonstrated promising efficacy data in preclinical studies. 54 In a 3-month phase 2 study, PBT2 succeeded in a 13% reduction of CSF Aβ and an executive function improvement in a dose-related pattern in patients with early AD. 55

Promotion of Aβ clearance (active or passive immunotherapy)

The 2 main immunotherapeutic approaches that intend to promote Aβ clearance and are currently tested in clinical and preclinical studies are active and passive immunization: 56

- Active immunization.

Aβ, phosphorylated tau (ptau) peptides, or specific artificial peptides such as polymerized British amyloidosis (ABri)-related peptide (pBri) 57 are used as immunogens. ABri is a rare hereditary amyloidosis associated with a mutation that results in the production of a highly amyloidogenic protein with a unique carboxyl terminus that has no homology to any other human protein. The pBri peptide corresponds to this terminus and induces an immune response that recognizes Aβ and ptau.

Antigen-presenting cells present the immunogens to B cells. Use of Ab or ptau peptides will produce antibodies to Ab or ptau epitopes, respectively. Use of pBri will produce antibodies to both Aβ and ptau epitopes. 56

- Passive immunization.

Monoclonal Abs to Ab, ptau, or b sheet epitopes are systemically and adequately for BBB penetration infused. As antibodies cross the BBB, they act to clear, degrade, or alternatively disaggregate or neutralize their targets. 56

- Stimulation of innate immunity either by active or passive immunization also ameliorates the pathology of the disease by promoting microglia and macrophage function. 56

Overall, Aβ-targeted strategies seem promising if used very early in the progression of the disease, before the presence of any symptoms; thus, they are developed in current trials in preclinical AD. Strategies that target tau pathology, although promising, bear the risk of toxicity at the moment. Nevertheless, it is hypothesized that, in sporadic late onset AD, ptau and Aβ pathologies could be evolved by separate pathways that can affect each other synergistically. 58 Consequently, it is possible that effective AD immunotherapies must be able to simultaneously target both ptau and Aβ pathologies. 56

Immunotherapeutic approaches have dominated in the past 15 years with negative results until now. However, lessons from these fails have altered the current immunotherapy development research for AD. 56

Active Aβ immunotherapy

Six active immunotherapy agents are currently studied in phase 1, 2, and 3 clinical trials:

CAD106 is an active Aβ immunotherapeutic agent, is studied in preclinical AD under the umbrella of the Alzheimer prevention initiative generation program, which comprises 2 phase 3 studies that evaluate simultaneously the safety and efficacy of CAD106 and umibecestat in asymptomatic individuals at risk of developing AD (60-75 years of age, APOE4 homozygotes, or APOE4 heterozygotes with elevated amyloid in CSF or in amyloid PET). 45

Subjects will be registered in generation study 1 (cohort 1: CAD106 or placebo, cohort 2: umibecestat or placebo) or generation study 2 (umibecestat 50 and 15 mg, or placebo). 45

ABvac40 is evaluated in a phase 2 study, as the first active vaccine against the C-terminal end of Aβ 40 . A phase 1 study was conducted with patients with mild to moderate AD aged 50 to 85 years. Neither incident vasogenic edema nor microhemorrhages were identified. Specific anti-Aβ 40 antibodies were developed in the 92% of the individuals receiving injections of ABvac40. 59

GV1001 peptide (tertomotide) was previously studied as a vaccine against various cancers, whereas now it is evaluated in a phase 2 study for AD. 60

ACC-001 (vanutide cridificar), an Aβ vaccine, was studied in phase 2a extension studies in subjects with mild to moderate AD. It was administered with QS-21 adjuvant. Long-term therapy with this combination was very well tolerated and produced the highest anti-Aβ IgG titers compared with other regimens. 61

UB-311, a synthetic peptide used as Aβ vaccine, has been advanced into an ongoing phase 2 study in patients with mild and moderate AD. In phase 1, it induced a 100% responder rate in patients with AD. The usual adverse effects were swelling in the injection site and agitation. A slower cognitive decline rate was observed in patients with mild AD. 62

Lu AF20513 epitope vaccine is estimated in a phase 1 study in mild AD. 63

The occurrence of encephalitis in previous studies (AN-1792) 64 led to the development of improved anti-Aβ active immunotherapy agents, more specific to Aβ sites less probable to activate T cells, currently studied in clinical trials. 5 , 6

Passive Aβ immunotherapy—via mAbs

Passive Ab immunotherapy via mAbs is the most active and promising class. Cerebral microhemorrhages and vasogenic edema are the main drawbacks in this group of agents. 5 Valuable learning gained from previous failed phase 3 trials of the first agents of this class, bapineuzumab 65 and solanezumab, 66 enlightened the mAbs’ research. Strict inclusion criteria were applied, such as biomarker proof of “amyloid positivity” and enrollment of individuals with preclinical stages of the disease. Furthermore, the design of the studies became more specific and targeted: the characteristics of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities were associated with the dose of antibodies and APOε4 genotyping, higher dosing necessity was recognized, and accurate measures for specific targets, such as reduction of Aβ plaque burden on amyloid PET, were required. 10

Many ongoing mAbs trials are in phase 3, including aducanumab, 67 gantenerumab, 68 and BAN2401 69 in prodromal and very mild AD, and crenezumab, 70 gantenerumab, and solanezumab 71 in studies for preclinical or at-risk populations. First results from aducanumab and BAN2401 trials suggested, at first, a treatment-related result of reducing in cerebral amyloid burden in agreement to deceleration of cognitive decline in patients with prodromal and very mild AD. 71 , 72 On the contrary, the initial trial of gantenerumab in prodromal AD was prematurely stopped for lack of efficacy, but exploratory analyses suggest that higher dosing of gantenerumab may be needed for clinical efficacy and an open-label extension for participating patients with mild AD is continued, simultaneously with a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with mild AD. 4 , 68 Similarly, until now, solanezumab did not delay rates of brain atrophy. 73

Intravenous doses of LY3002813 (donanemab) and LY3372993 are studied in participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and mild to moderate AD in separate phase 1 clinical studies. 4

Passive Aβ immunotherapy—via immunoglobulins

Anti-Aβ antibodies are included in naturally occurring autoantibodies. In contrast to mAbs, blood-derived human anti-Aβ immunoglobulin G (IgG) Abs are polyclonal, with lower avidity for single Aβ molecules, and higher for a broader range of epitopes, especially in Aβ oligomers and fibrils. The natural presence of antibodies against Aβ has been reported in intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg); thus, IVIg has been considered as a possible AD treatment. Intravenous immunoglobulin is obtained from plasma of healthy donors and is made up of human Abs mainly of the IgG-type. 5 , 74

Nevertheless, the first completed phase 3 trial of IVIg as a treatment for AD demonstrated good tolerability but lack of efficacy of the agent on clinical stability or delay of cognitive or functional decline of participants with mild and moderate AD. 74

Another strategy directed at diminishing the accumulation of Aβ in the brain is based in altering the transportation of Aβ through the BBB. A recent therapeutic method performs plasma exchange (PE) with albumin replacement, inducing the shifting of the existing dynamic equilibrium between plasma and brain Aβ. This therapeutic method is based in the following considerations: (1) high levels of Aβ aggregation in the brain are accompanied by low levels of Aβ in CSF in AD, (2) albumin is the main protein transporter in humans, (3) albumin binds around the 90% of the circulating Aβ, and (4) albumin has proved Aβ-binding ability. Consequently, it is suggested that PE-mediated possession of albumin-bound Aβ would increase the shift of free Aβ from CSF to plasma to correct the imbalance between brain and blood Aβ levels. 75

A phase 3 trial called Alzheimer’s Management by Albumin Replacement (AMBAR) in mild and moderate AD assesses PE with several replacement volumes of albumin, with or without intravenous immunoglobulin. 76

Furthermore, an ongoing phase 2 study evaluates IVIg Octagram 10% in mild and moderate AD. 4

A novel immunotherapeutic strategy that targets simultaneously Aβ and tau is represented by the NPT088 agent. NPT088 is a mixture of the capsid protein of bacteriophage M13 (g3p) and human-IgG 1 -Fc. NPT088 reduced Aβ and ptau aggregates and improved cognition in aged Tg2576 mice. The agent is currently assessed in a phase 1 clinical study. 77

Tau-related mechanisms—DMTs

Anti-phospho-tau approaches consist a major potential treatment strategy, even if there are yet no agents with this specific MOA advanced in phase 3 studies.

Only 1 agent with tau-related mechanism is evaluated in phase 2/3, whereas 10 agents that target tau as one of their mechanisms are evaluated in phase 2, and 5 more agents with tau-related mechanism are assessed in phase 1 studies. 4

Prevention of ptau formation

The hyperphosphorylation of tau is induced by kinases. 78 Thus, kinase inhibitors are examined as potential therapeutic approaches targeting tau. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3β) has become prominent as a possible therapeutic target. The most studied GSK3 inhibitor is lithium chloride, a therapeutic agent for affective disorders, which seems to prevent phosphorylation of tau in mouse models. Lithium is currently reassessed within the novel framework for drug research. 79

Another GSK-3 inhibitor, tideglusib, did not meet phase 2 clinical endpoints in patients with mild and moderate AD. 80

ANAVEX 2-73 is evaluated in a phase 2 trial, for eligible subjects AD MCI or mild AD. 81 ANAVEX 2-73 is also a GSK-3b inhibitor but additionally it is a high affinity sigma 1 receptor agonist and a low-affinity muscarinic agonist. 4 Results presented at 2019 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference (AAIC) revealed that patients treated with ANAVEX 2-73 had high levels of 2 gut microbiota families, Ruminococcaceae and Porphyromonadaceae, which were associated with improved activities of daily living. The effect might potentially be reversal of the microbiota imbalances and might have a homeostatic effect on the brain-gut-microbiota axis. 81

Inhibitors of tau aggregation

Methylene blue (MB), a known phenothiazine, is evaluated in AD studies as a potential tau aggregation inhibitor. The problem with this drug is that urine is colored blue, resulting in a lack of blinding. A monotherapy trial with MB on mild and moderate AD ( {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT00515333","term_id":"NCT00515333"}} NCT00515333 ) has demonstrated some clinical benefit in moderate, but not mild AD. 82 However, the methodology of the study, as blinding is impossible, has been highly criticized. 83

Methylene blue’s derivative TRx0237 (LMTX) which was studied in phase 3 failed finally to show efficacy, and based on the analysis of the results, a new phase 2/3 study named LUCIDITY was started 1 year ago in subjects with mild AD with a lower dose of the agent. 84

Microtubule stabilizers

The microtubule-stabilizing agent davunetide was studied in a phase 2 trial but it did not meet the clinical end points. 85

TPI-287 (abeotaxane), a small molecule derived from taxol, is a microtubule protein modulator. It was administered intravenously to patients with mild to moderate AD in a phase 1/2 study ( {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT01966666","term_id":"NCT01966666"}} NCT01966666 ). First results presented report that the agent was not well tolerated by the participants. 84

IONIS MAPTRx (BIIB080), a microtubule-associated protein tau RNA inhibitor, an antisense oligonucleotide, is assessed in a phase 2 clinical study that is still in the recruiting process of patients with mild AD ( {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT02623699","term_id":"NCT02623699"}} NCT02623699 ). 86

Targeting posttranslational modifications of Tau

Another tau modification that promotes aggregation besides phosphorylation is posttranslational modification by lysine acetylation. Thus, the use of inhibitors of tau acetylation is proposed as a possible therapeutic approach for AD.

Nilotinib is a c-Abl tyrosine kinase inhibitor which is used in patients with leukemia. It also appears to trigger intraneuronal autophagy to clear tau. It is now studied in a phase 2 trial in individuals with mild to moderate AD ( {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT02947893","term_id":"NCT02947893"}} NCT02947893 ). 4 , 83

Promotion of Tau clearance—immunotherapy

Recently emerged evidence in various animal models strongly suggests that targeting ptau epitopes is a practical approach to induce antibody responses that are able to promote tau clearance. 81 Hence, a number of active and passive immunotherapy projects have reached clinical trials for AD treatment. 83

Active immunotherapy

AADvac1 contains a synthetic tau peptide and is currently studied in a phase 2 clinical study in mild to moderate AD ( {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT02579252","term_id":"NCT02579252"}} NCT02579252 ). 4 , 10 , 83

Passive immunotherapy

ABBV-8E12 is a humanized anti-tau MAb assessed in a phase 2 clinical study in patients with early AD ( {"type":"clinical-trial","attrs":{"text":"NCT02880956","term_id":"NCT02880956"}} NCT02880956 ). 87