Essay on Holistic Health

Students are often asked to write an essay on Holistic Health in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Holistic Health

What is holistic health.

Holistic health is about caring for the whole person. This means looking after your body, mind, and emotions. It’s not just about not being sick; it’s about feeling good in every way.

Taking care of your body is important. Eating healthy foods, being active, and getting enough sleep are all part of this. When your body feels good, you can do your best at school and play.

Mind and Emotions

Your thoughts and feelings are also key. Talking to friends, writing in a journal, or doing things you enjoy can keep your mind and heart happy.

Together as One

Holistic health means all parts of you work together. When your body, mind, and emotions are in harmony, you’re truly healthy. It’s like a team where every player is important.

250 Words Essay on Holistic Health

Understanding holistic health.

Holistic health is about caring for the whole person. This means not just focusing on one part of the body when someone is sick, but looking at everything—body, mind, and spirit. It’s like seeing a person as a big puzzle, and each piece is important to make the whole picture.

First, let’s talk about the body. When we think of health, we often think of eating right, exercising, and getting enough sleep. These are key parts of keeping our bodies working well. Eating fruits and vegetables, playing outside, and going to bed on time help us grow strong and stay healthy.

Next is the mind. This is about our feelings and thoughts. Being happy, worrying less, and doing well in school are signs of a healthy mind. It’s important to talk about our feelings and not keep them inside. Reading books, playing games that make us think, and spending time with friends can keep our minds sharp.

Lastly, there’s the spirit. This can mean different things to different people. It might be feeling calm, being kind, or believing in something bigger than ourselves. Some people find peace in nature, others in drawing or music, and some through faith. It’s about what makes us feel good inside.

Bringing It All Together

Holistic health means taking care of all parts of ourselves. It’s like a team, where the body, mind, and spirit work together. When all parts are cared for, we feel our best. Remember, every piece of the puzzle is important to be truly healthy.

500 Words Essay on Holistic Health

When we think about staying healthy, we often picture eating right and exercising. But there’s more to health than just that. Holistic health is about caring for the whole person. It means looking after our bodies, minds, and spirits all at the same time. Imagine you’re like a puzzle, with pieces that fit together to make you whole. Holistic health is about making sure all those pieces are in good shape.

First, let’s talk about the body. This part is about eating foods that are good for you, like fruits and vegetables, and staying active. When you run, play sports, or even walk, you help your body stay strong. It’s also about sleeping well so your body can rest and repair itself. Think of your body like a car; it needs the right fuel and regular maintenance to keep running smoothly.

Next is the mind. Just like you exercise your body, you need to keep your mind active too. This can be through reading, solving puzzles, or learning new things at school. It’s also important to talk about your feelings and not keep them bottled up inside. When you’re sad, worried, or angry, talking to friends, family, or a teacher can make a big difference. Your mind is like a garden; it needs to be looked after and given room to grow.

Then there’s the spirit. This doesn’t just mean religion, although for some people, that’s a part of it. It’s about feeling happy, loving yourself, and enjoying life. You can feed your spirit by doing things you love, like playing music, painting, or spending time in nature. Your spirit is like a bird; it needs space to soar and explore.

Connecting the Pieces

Holistic health is about connecting all these pieces. It’s like when you help a friend, you’re not just being kind; you’re also making your own spirit feel good. Or when you learn something new, you’re not just making your mind sharper; you’re also giving your spirit a boost because it feels great to learn.

Everyone Together

Holistic health isn’t something you do alone. Your family, friends, and community are all part of it. They can support you, cheer you on, and help you stay on track. It’s like being on a team where everyone wants you to win.

Small Steps

You don’t have to make big changes all at once to be more holistic. Small steps can make a big difference. Choose a fruit instead of a candy bar, take a walk instead of watching TV, or tell someone how you feel instead of keeping it to yourself. Each little choice adds up to a healthier you.

In Conclusion

Holistic health is a big idea, but it’s made up of small, simple parts. It’s about taking care of your body, mind, and spirit, and making sure they all work together. It’s like a team, where each player has a special job, but they all need to work together to win the game. By looking after all parts of yourself, you can feel your best and do your best in everything you do.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Hollywood

- Essay on Homework Should Be Banned

- Essay on Pirates

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

The Holistic Health Promotion Model Overview Essay

Introduction, a holistic health promotion strategy, the importance of the preparation of a holistic health promotion strategy, assessment of data in the development of a holistic health promotion strategy, effective communication of the health promotion strategy to patients, reference list.

The holistic health promotion model offers better therapy, is very logical but at the same time narrow. It disqualifies other measures that are “like Cures”. The holistic approach takes the best possible perception of sickness, addressing the various possible causes, offering a therapy process that is multi-dimensional that is opposed to the cures that target specific illnesses. The model is concerned with an individual’s susceptibility towards disease as well as the transmission. The approach also assesses how people can try to get more hardy or disease-resistant before seeking intervention by medication or become more resilient before catching a disease. This paper will therefore address the concerns in a holistic approach that will include spiritual support and beliefs, physical concerns, and the possible distress in the context of a family; the significance of a holistic health strategy; the importance of the holistic approach, and development of the strategy.

Holistic support of health is an intervention strategy that takes into account factors that affect the wellbeing of human beings and these include the physical body, the emotional aspect, the mind, and the spiritual perception of human beings. The strategy also combines the best service in modern medicine about the diagnosis, monitoring, and prognosis as well as intervention (Berg, 2002, p. 385). In this case, ancient and innovative means of intervention can be used to support modern therapy in achieving better results.

The patients seem to be strict believers and therefore staunch followers of their religious beliefs as well as their cultural principles. This is evidenced by the fact that Manam who is a male aged 55 years of age suffers depression, anxiety as well as painful urination but does not want his wife to be notified of his condition. He also finds it very hard to discuss his problem with the female nurses. When asked questions that related to his other urinary symptoms, the patients feel very reluctant to inform the female nurses. In the first year, he had denied hematuria but he ultimately came to admit having experienced hematuria.

Shuba, the wife of Manan states that she had been using herbal drugs which have not worked for her, however. During the examination, the patient hesitated to take off her gown due to issues of modesty. Furthermore, she has continued taking foods that are high in carbohydrates and fats despite having been on high blood pressure drugs. The strategy of intervention, in this case, will be very critical since the patients will need to be monitored and treated in a way that they would feel that their spiritual or cultural beliefs are not infringed.

The holistic approach will work on the basis that good health is a very strong social and economic resource (Berg, 2002, p. 385). As a result, this would call for advocacy of better health. The patients will be counseled to understand that their cultural, environmental, social, and economic life dimensions can be tuned to favor good health. Otherwise if not properly managed, it could be very harmful.

‘Enabling’ will be the process of making the patients understand that the cultural and spiritual differences with the current medication state and ensure that the patients get the opportunity to utilize the resources that will make them achieve full health potential rather than focus on the herbal medicine that has not been working (Berg, 2002, p. 385). After understandings that medical problems are not just about the symptoms, the patients will be more likely to discuss with family members and as a result, actively get involved in the process of healing rather than sit back and be passive recipients of care.

A holistic approach is very important to the 21 st century as a way of achieving health intervention since it offers a solution to the entire problems that are underlying in this case. Good health is considered the most realistic and inalienable resource that can help an individual meet his/her social, economic, cultural, and even political satisfaction (Berg, 2002, p. 389). When the disease is healed then the patient will not only enjoy that absence of the symptoms but the dieses itself will be healed. And since the approach also covers the aspects of emotions and society, the patients experience a state of complete mental, physical and social comfort.

The process can integrate very well with moderns scientific discoveries in the medical practice. Therefore their preparation can go a long way in enhancing tee process of healing the patient. The process needs proper preparation since it involves some activities that could be tasking. This is because some of the intervention measures include exercise, observing a natural diet, relaxing, using an herbal medication, and use of additional nutrition supplements, spiritual and mental counseling as well as other self-regulated practices (Naidoo & Wills, 2000, p. 45).

The significance of a holistic approach in this process is that it will be able to address not only the symptoms but rather the whole person. As a craftsman, Manan will be able to get back to his work comfortably while his wife will b able to manage her weight and the cases of fatigue she suffered on exertion. The two granddaughters Achala and Gara will be helped to manage behavior problems and emotional issues due to the loss of parents respectively. The holistic process will address the current state of the patients who need counseling like in the case of Gara and Achala for them to get to terms with the life condition at home considering that their parents are dead and the grandparents are ailing. The process will be in this case addressing the prevention of further problems, emphasizing on maintenance of good health, achieving a very high degree of wellness and life longevity (Naidoo & Wills, 2000, p. 45). The process is a very successful paradigm in medication as it ensures the patient is an active participant in the process of healing.

Data assessment is very important in developing a holistic health plan as the strategy usually approaches the problems from a multi-dimensional perspective. It would be therefore very beneficial when the practitioners or the person administering therapy have a full understanding of the patients. To begin with, it’s imperative to understand how the lifestyle of the patient impacts the physical, emotional, economical intellectual, and spiritual elements (Naidoo & Wills, 2000, p. 49). From that, the practitioner can be able to find out how to develop a plan that would be effective and very appropriate in achieving the required results. This is of course after assessing the patient’s beliefs about such an 8intervention and counseling them on the process which would be very easy to attain since holistic intervention blends well with many forms of therapy (Naidoo & Wills, 2002, p. 78). The main focus here will be on personal resources which include mental aspects, physical wellbeing, and spiritual growth. Since the family in this context seems to be very religious and strict observers of their cultural beliefs, counseling, and understanding of the new therapies will be highly needed (Naidoo & Wills, 2000, p. 45). Knowing that Manan has a history of depression, anxiety and does not want to tell their wife about his problem that affects his urinary and reproductive system is evidence that he is somehow conservative due to culture or religion. The same goes for the wife, Shuba who feels uncomfortable undressing for the medical examination for modesty reasons. Achala has a character problem and hence finds a problem making new friends. Gara suffers emotionally and therefore develops a negative attitude towards medication due to the way they make her feel, “weird and different”.

Since the health promotion strategy in holistic healing involves covering several dimensions that affect the wellbeing of an individual, it’s usually a problem to communicate the aim of the process. Many people will be that their privacy is being infringed especially when discussing some spiritual matters they are not comfortable sharing out or are not allowed by religion (Naidoo & Wills, 2002, p. 78). For modesty reasons, Shuba feels uncomfortable taking off her gown, Manan on the other hand feels hesitant to tell female nurses about his urinary problem.

To effectively communicate that health promotion is important to patients, guiding and counseling will need to be used. Patients have to be made to understand that being healthy is the greatest resource a human being can ever have. From here, they need to be made to appreciate that all efforts have to be employed to ensure that health status is restored despite the conditions one has to go through (Naidoo & Wills, 2002, p. 78). There could be ethical concerns but when it comes to health issues the trained medical practitioners are required to assist as much as possible to save a life. The spiritual concerns of the patients can be compromised for life’s sake. The type of care to be administered is evidence-based and the patients have to be given the reassurance that the process serves in their best interests at heart (Naidoo & Wills, 2002, p. 78).

From ancient times, many communities have struggled to come up with several explanations or adopt new justifications and philosophies in their enthusiastic quest for better health. In some instances, sickness has been associated with evil spirits, microbes, and divine retribution. The contemporary approach on the other hand bases its arguments on the contagion illness theory and symptom control in diseases and hence promotes medicine and other measures that counter any damaging agents to the body. Health promotion and holistic approach hence aims at changing certain behaviors, managing risk factors, offering intervention and alleviating fears, and thus giving individuals alternative ways of life and medication that will enable them to achieve healthier lives.

Berg, G.V. (2002). A Holistic-Existential Approach To Health Promotion Scandinavian Journal Of Caring Sciences, 17 (4): 384 – 391

Naidoo J, & Wills J. (2000). Health Promotion : Foundations for Practice . 2 nd Ed. Edinburgh & New York: Baillière Tindall Pub.

Naidoo, J., & Wills, J. (2002). Complementary Therapies: A Resource for Integrated Practice . London: Elsevier Science Publishers.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, March 30). The Holistic Health Promotion Model Overview. https://ivypanda.com/essays/holistic-health-promotion/

"The Holistic Health Promotion Model Overview." IvyPanda , 30 Mar. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/holistic-health-promotion/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'The Holistic Health Promotion Model Overview'. 30 March.

IvyPanda . 2024. "The Holistic Health Promotion Model Overview." March 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/holistic-health-promotion/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Holistic Health Promotion Model Overview." March 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/holistic-health-promotion/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Holistic Health Promotion Model Overview." March 30, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/holistic-health-promotion/.

- Holistic Care for Patient with Pressure Ulcer

- Holistic Rubric in Nursing Practice

- Moving Toward Holistic and Preventive Care

- Organ Donation: Donor Prevalence in Saudi Arabia

- Kawasaki Disease Analysis

- Reliability and Validity of Chart Audits

- Healthy People 2010 Targeted Objective

- How Pharmacy Practice Has Changed

What Is Holistic Health and Why Is It so Important?

Last Updated: June 8th, 2021

Holistic health has become a popular topic lately. Many medical practitioners and self help gurus are adopting the holistic approach, but it is more than just an ephemeral trend. Holistic healthcare is an integrative approach to health and wellbeing, which sees the person as a whole, not just a symptom to treat.

- What Is Holistic Health?

- Why Does Holistic Health Matter?

- What Is Holistic Medicine?

- The Holistic Approach to Work Life Balance During the COVID 19 Pandemic

- How to Build Our Own Pillars of Holistic Health and Wellness While COVID-19 We Are Stuck at Home

1 . What Is Holistic Health?

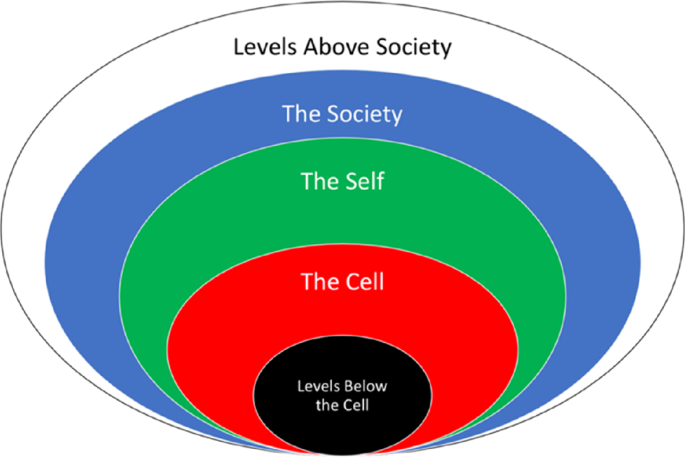

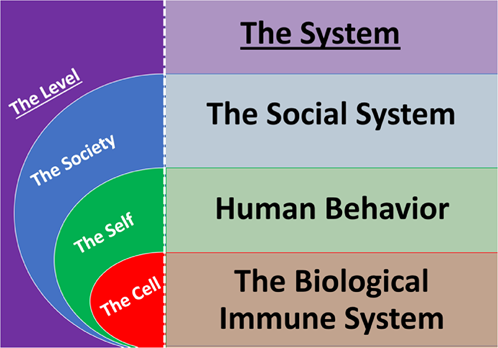

Holistic health is an approach to wellness that views the human being as a whole. To achieve holistic health, a certain harmonious interaction is needed between the body, the mind, the soul, the emotions, the environment, and all the other factors that influence living. Holistic health doesn’t believe in curing one symptom, instead it aims to elevate the whole living system, which is traditionally made of 8 key components. They are known as the 8 pillars of holistic health :

Physical health : It involves taking care of the physical body, by making sure to get enough sleep, to move and to exercise regularly.

Nutritional health : You are what you eat. Nutrition influences physical, emotional and intellectual health. It’s important to consume a diet rich in vegetables and fruits, and low in processed products. Pure and clean drinking water is also a must.

Intellectual health : Making sure to challenge the brain daily is essential, either by completing puzzles, or by constantly learning something new.

Emotional health : It means developing emotional awareness and intelligence. Allowing emotions to be expressed, recognized and honored. But also being aware of one’s emotional tank, what fills it up and what drains it.

Spiritual health : This pillar may mean different things to different people, but we all have that feeling of longing for more in common. Tending to our spiritual side gives us a sentiment of belonging and of purpose.

Environmental health : It means being ecologically conscious, honoring the blue planet and its resources while being aware that we are only visitors of this earth.

Social health : Humans are naturally social creatures. Tending to our social side makes us feel a part of a pack and a community. Having a trustworthy support system and a fulfilling social life are important aspects of social health.

Financial health : Money is an important resource for security and goal-attainment. Financial health means cultivating a positive relationship with money, and mindfully managing financial resources.

2 . Why Does Holistic Health Matter?

According to the World Health Organization, health is defined as a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

Conventional medicine only cares about disease and infirmity and doesn’t guarantee the full spectrum of health as defined above. In order to achieve this state of complete wellbeing, a holistic approach is mandatory, hence the importance of holistic health.

No one can contest with how much life has improved thanks to conventional medicine. But at the same time, we cannot deny the feelings of dissatisfaction, void, and loneliness that conventional medicine alone isn’t able to fix. Holistic health matters because conventional models of care are no longer enough.

3 . What Is Holistic Medicine?

Holistic medicine is an approach to healthcare that uses both conventional western medicine and alternative medicine as tools to ensure optimal health and wellbeing. Alternative treatments include nutrition and lifestyle interventions, therapies derived from traditional Chinese or Indian medicine, hypnosis, phototherapy, aromatherapy, meditation, and various self-development techniques.

Furthermore, in holistic medicine, the goal isn’t to cure a symptom, but rather to elevate the whole system. As a result, not only is the person healthy, but they are also the best version of themselves.

4 . The Holistic Approach to Work Life Balance During the COVID 19 Pandemic

Having a healthy work life balance is an essential part of healthy living . This has become even more important during our current situation. During the pandemic, many of us will continue to work from home, taking on multiple roles at the same time. Consider these tips to stay healthy and productive.

The COVID 19 pandemic has changed so many things in our lives. It has pushed us out of our comfort zones, and it made us face our doubts and deepest fears. Furthermore, since most people are either working or studying from home, it has made the line that separates life and work blurrier than before, hence the need now more than ever, to set healthy boundaries for work life balance.

Most people have already heard the mainstream advice about keeping a healthy work life balance, but the holistic approach would be to examine each health pillar individually. By adopting the holistic approach to work life balance, the goal isn’t simply to avoid burnout or disease, but it’s rather to become the most healthy, vibrant, and ideal version of yourself.

5 . How to Build Our Own Pillars of Holistic Health and Wellness While COVID-19 We Are Stuck at Home

We are living in unprecedented times. The current lockdown means that we are forced to live differently and work differently. Coronavirus can stir up all sorts of feelings, like fear, anxiety or stress. In this scenario, destress technique becomes crucial. This is the best time to find simple destress technique and build your own pillars of holistic health. Here are 11 tips to get holistic health . Keep reading to find out what they are.

Instead of viewing this time of quarantine and working from home as a period of boredom and loneliness, we can view it as a chance to learn and start practicing holistic wellness.

Whether you work or study from home, there are some common pillars for holistic wellness. First you need to take care of your physical body, by taking breaks during the day, going for walks, working out and keeping a healthy sleep schedule. Being stuck at home is also a great opportunity to cook healthy meals made from fresh in season ingredients. It’s helpful to be mindful of the environment you spend most of your day in, and to ensure it is clean and tidy. Keeping in contact with friends and family is important, since spending all day at home can make us long for human warmth. Emotionally, it’s essential to be aware of how you’re feeling, and to take the necessary steps to prevent burnout and mental health issues. Keeping a steady spiritual practice can immensely help with the doubt and uncertainty that plague us all. And last but not least, it’s important to be financially aware, and to avoid overspending (or overeating for that matter) to fill any emotional void you may carry.

If you work from home:

Prioritize self care! Tend to your needs before you take care of your job, because what good is a salary at the end of the month if you feel bad about yourself?

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, more people are working from home than ever before. Whether you are new to working remotely or just want to upgrade, these tips from remote working professionals can help you stay productive and keep your balance.

If you study from home:

We have all seen the news and are currently understanding the world situation, so we need to find effective ways to study or work at home. Take this time to reflect on your future and the things you want to become. Remember that studying is just one way to make your dreams come true. Also take this time to learn other skills that will help you in your career.

Studying at home does not have to be boring or unnecessarily complicated. Here are 5 study tips and you can combine with your own tips and tricks and set a schedule to make the most productive entrepreneurs jealous.

Remember to take regular breaks and use your free time to do things that will make you smile and feel good. There are many things you can do during the quarantine period, including cooking, playing video games, completing online courses, etc. So this is an excellent time to develop on all levels.

6 . Conclusion

Holistic wellness is an approach to healthcare that sees the person as a whole and not just a symptom. The goal of holistic wellness is to ensure optimal wellbeing and not just being free of disease. Being stuck at home because of the COVID 19 pandemic is a great opportunity to become more aware of our health, and to learn and incorporate more holistic wellness into our daily life.

Use the Wellness Wheel Worksheet to help you to identify what areas of your life are fulfilled and healthy and what areas need improvement and attention

Let Start to Practice Holistic Health

Personalize Your Experience

Log in or create an account for a personalized experience based on your selected interests.

Already have an account? Log In

Free standard shipping is valid on orders of $45 or more (after promotions and discounts are applied, regular shipping rates do not qualify as part of the $45 or more) shipped to US addresses only. Not valid on previous purchases or when combined with any other promotional offers.

Register for an enhanced, personalized experience.

Receive free access to exclusive content, a personalized homepage based on your interests, and a weekly newsletter with topics of your choice.

Home / Living Well / A holistic approach to integrative medicine

A holistic approach to integrative medicine

As studies continue to reveal the important role the mind plays in healing and in fighting disease, a transformation is taking place in hospitals and clinics across the country. Meta description: Discover principles and benefits of integrative medicine, a comprehensive approach combining conventional and complementary therapies.

Please login to bookmark

Interested in integrative medicine? Read the following excerpt from the Mayo Clinic Guide to Integrative Medicine .

People who take an active role in their health care experience better health and improved healing. It’s a commonsense concept that’s been gaining scientific support for several years now.

As studies continue to reveal the important role the mind plays in healing and in fighting disease, a transformation is taking place in hospitals and clinics across the country. Doctors, in partnership with their patients, are turning to practices once considered alternative as they attempt to treat the whole person — mind and spirit, as well as body. This type of approach is known today as integrative medicine.

Incorporate integrative medicine alongside your treatments

Integrative medicine describes an evolution taking place in many health care institutions. This evolution is due in part to a shift in the medical industry as health care professionals focus on wellness as well as on treating disease. This shift offers a new opportunity for integrative therapies.

Integrative medicine is the practice of using conventional medicine alongside evidence-based complementary treatments. The idea behind integrative medicine is not to replace conventional medicine, but to find ways to complement existing treatments.

For example, taking a prescribed medication may not be enough to bring your blood pressure level into a healthy range, but adding meditation to your daily wellness routine may give you the boost you need — and prevent you from needing to take a second medication.

Integrative medicine isn’t just about fixing things when they’re broken; it’s about keeping things from breaking in the first place. And in many cases, it means bringing new therapies and approaches to the table, such as meditation, mindfulness and tai chi. Sometimes, integrative approaches help lead people into a complete lifestyle of wellness.

What types of integrative medicines are available?

What are some of the most promising practices in integrative medicine? Here’s a list of 10 treatments that you might consider for your own health and wellness:

- Acupuncture is a Chinese practice that involves inserting very thin needles at strategic points on the body.

- Guided imagery involves bringing to mind a specific image or a series of memories to produce certain responses in the body.

- Hypnotherapy involves a trancelike state where the mind is more open to suggestion.

- Massage uses pressure to manipulate the soft tissues of the body. There are many different kinds of massage, and some have specific health goals in mind.

- Meditation involves clearing and calming the mind by focusing on your breathing or a word, phrase or sound.

- Music therapy can influence both your mental and physical health.

- Spinal manipulation, which is also called spinal adjustment, is practiced by chiropractors and physical therapists.

- Spirituality has many definitions, but its focus is on an individual’s connection to others and to the search for meaning in life.

- Tai chi is a graceful exercise in which you move from pose to pose.

- Yoga involves a series of postures that often include a focus on breathing. Yoga is commonly practiced to relieve stress, as well as treat heart disease and depression.

Who can integrative medicine help?

A number of surveys focused on the use of integrative medicine by adults in the United States suggest that more than a third of Americans are already using these practices as part of their health care.

These surveys demonstrate that although the United States has the most advanced medical technology in the world, Americans are turning to integrative treatments — and there are several reasons for this trend. Here are three of the top reasons why more and more people are exploring integrative medicine.

Integrative medicine for people engaged in their health

One reason integrative medicine is popular is that people in general are taking a greater, more active role in their own health care. People are more aware of health issues and are more open to trying different treatment approaches.

Internet access is also helping to fuel this trend by playing a significant role in improving patient education. Two decades ago, consumers had little access to research or reliable medical information. Today, clinical trials and pharmaceutical developments are more widely available for public knowledge.

For example, people who have arthritis can find a good deal of information about it online. They may find research showing that glucosamine, for example, helps with joint pain and doesn’t appear to have a lot of risks associated with it. With this information in hand, they feel empowered to ask their doctors if glucosamine might work with their current treatment plans.

Integrative medicine for an aging population

A second reason for the wider acceptance of integrative treatments is the influence of the baby boomer generation. This generation is open to a variety of treatments as it explores ways to age well. In addition, baby boomers are often dealing with several medical issues, from weight control to joint pain, high blood pressure and elevated cholesterol. Not everyone wants to start with medication; many prefer to try complementary methods first.

Integrative medicine for the chronically stressed

A third reason for the growth, interest and use of integrative therapies is the degree of chronic stress in the American lifestyle. Workplace stress, long commutes, relationship issues and financial worries are just some of the concerns that make up a long list of stressors.

Although medications can effectively treat short-term stress, they can become just as damaging — and even as life-threatening — as stress itself is when taken long term. Integrative medicine, on the other hand, offers several effective, evidence-based approaches to dealing with stress that don’t involve medication. Many otherwise healthy people are learning to manage the stress in their lives successfully by using complementary methods such as yoga, meditation, massage and guided imagery.

Considering that many healthy people are engaging in integrative practices, it isn’t surprising to find out that they’re turning to these treatments in times of illness, as well. Here are just a few ways integrative medicine is used to help people cope with medical conditions:

- Meditation can help manage the anxiety and discomfort of medical procedures.

- Massage has been shown to improve recovery rates after heart surgery.

- Gentle tai chi or yoga can assist the transition back to an active life after illness or surgery.

Conventional Western medicine doesn’t have cures for everything. Many people who have arthritis, back pain, neck pain, fibromyalgia and anxiety look to integrative treatments to help them manage these often-chronic conditions without the need for medications that may have serious side effects or that may be addictive.

The risks and benefits of integrative medicine

As interest in integrative medicine continues to grow, so does the research in this field. Researchers are studying these approaches in an effort to separate evidence-based, effective therapies from those that don’t show effectiveness or may be risky. In the process, this research is helping to identify many genuinely beneficial treatments. In essence, both consumer interest and scientific research have led to further review of these therapies within modern medicine.

As evidence showing the safety and efficacy of many of these therapies grows, physicians are starting to integrate aspects of complementary medicine into conventional medical care. Ultimately, this is what has led to the current term integrative medicine.

Ask your healthcare team about integrative medicine and wellness

If you’re interested in improving your health, many integrative medicine practices can help. Not only can they speed your recovery from illness or surgery, but they can also help you cope with a chronic condition. In addition, complementary practices such as meditation and yoga can work to keep you healthy and may actually prevent many diseases.

Relevant reading

Mayo Clinic First-Aid Guide for Outdoor Adventures

The first-ever first-aid book from medical experts at Mayo Clinic, the most trusted name in medicine. Welcome to the jungle! Or the mountains! Or the high seas! Wherever your travels take you, Mayo Clinic First Aid Guide for the Outdoor Adventures is here to help you survive your next trek…

Discover more Living Well content from articles, podcasts, to videos.

You May Also Enjoy

Privacy Policy

We've made some updates to our Privacy Policy. Please take a moment to review.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Public Health Ethics

- PMC10849326

Health as Complete Well-Being: The WHO Definition and Beyond

Thomas schramme.

Department of Philosophy, University of Liverpool, Gillian Howie House, Mulberry Street, Liverpool, L69 7SH, UK

The paper defends the World Health Organisation (WHO) definition of health against widespread criticism. The common objections are due to a possible misinterpretation of the word complete in the descriptor of health as ‘complete physical, mental and social well-being’. Complete here does not necessarily refer to perfect well-being but can alternatively mean exhaustive well-being, that is, containing all its constitutive features. In line with the alternative reading, I argue that the WHO definition puts forward a holistic account, not a notion of perfect health. I use historical and analytical evidence to defend this interpretation. In the second part of the paper, I further investigate the two different notions of health (holistic health and perfect health). I argue that both ideas are relevant but that the holistic interpretation is more adept for political aims.

Introduction

‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ ( World Health Organisation [WHO], 1948 : 100). In this paper, I argue that this famous WHO definition of health is fully adequate. Criticism that has been levied against it is based on a specific interpretation that is not the only alternative. In addition to defending the WHO definition, I will discuss two different meanings of the concept of health, which can lead to confusion if not properly kept apart. This is important, for historical and analytical reasons, because the WHO definition can indeed be interpreted in different ways and because we need to get to grips with the differences between types of definitions of health. My second aim in this paper is hence to explain and to properly keep apart two different conceptualisations of health. 1

As regards the WHO definition, I will claim that critics have read the word complete in the phrase ‘complete physical, mental and social well-being’ in a way that goes against the likely intentions of the draftees of the definition. The common objections, for instance, accusing the WHO definition of utopianism and overreach, are based on an implicit assumption, according to which complete is a quantitative term. In other words, critics assume that the phrase means that health is a state of well-being to the largest degree. I will call this interpretation perfect health . So, the critics claim that the WHO identifies health with the largest degree of well-being, that is, with perfect well-being or—in less technical terms—with happiness.

However, the term complete can also have a qualitative meaning. 2 When we say that something is a complete specimen of its kind, then we mean that it has all the features that are constitutive of it. For instance, a complete dinner is one that contains a starter, a main dish and a dessert. Accordingly, complete well-being might be understood as a state that is exhaustive of all constitutive features of well-being. These are, according to the WHO, physical, mental and social aspects. I will call this holistic health . 3 In brief, I will claim that the WHO endorses a holistic account of health, not a perfectionist account. 4

In the second section, I briefly introduce the most important objections to the WHO definition. They have mainly to do with an alleged confusion of health with happiness, which then purportedly leads to a form of medicalisation of human life. In the third section, I discuss the likely intentions behind the WHO definition. I do this by referring to the two readings mentioned before, perfect health and holistic health. There are systematic and historical reasons as to why the WHO plausibly intended a holistic interpretation of health. In the fourth section, I discuss the two interpretations of health in their own right. I introduce their purposes and some objections to either notion. As is the case with many concepts we use, there is no single right or wrong conceptualisation of health. However, I argue that a holistic concept of health is better suited for the purposes of the WHO and more generally for political and economic agendas.

Criticism of the WHO Definition

The health definition of the WHO has often been dismissed by philosophers of medicine and medical scientists (for an overview, see Leonardi, 2018 ). One of the main reasons has been the alleged confusion of health and happiness, that is, a state of complete well-being. 5 If health is understood as happiness, it has been argued, there are many highly problematic consequences, most importantly the medicalisation of people’s lives. After all, health is also interpreted as a basic human right in the same document: ‘The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition’ ( WHO, 1948 : 100). If people fall short of the ideal of perfection, that is, if they are not in a state of complete well-being, their health ought to be enhanced. With health care being an important instrument to reach health, the lives of people seem to fall under the remit of health-related institutions, especially medicine, in all their aspects. For instance, if someone is sad, they lack health in the sense of complete well-being. Accordingly, following the WHO constitution, they apparently have a justified claim to be made healthy, that is, happy, potentially by using mood-enhancing drugs or other medical means.

A prominent and influential critique of the WHO definition stems from Daniel Callahan: ‘[T]he most specific complaint about the WHO definition is that its very generality, and particularly its association of health and general well-being as a positive ideal, has given rise to a variety of evils. Among them are the cultural tendency to define all social problems, from war to crime in the streets, as “health” problems’ ( Callahan, 1973 : 78; see also Kass, 1975 : 14, for a very similar critique). This is an example of the critique of overreach (cf. Bickenbach, 2017 : 962), that is, of applying a medical concept to areas that pose other types of problems than healthcare problems.

Another problem that has repeatedly been pointed out is the utopianism of the definition. It seems that ‘[t]he requirement for complete health “would leave most of us unhealthy most of the time”’ ( Huber et al ., 2011 : 235; quoting Smith, 2008 ; see also Saracci, 1997 : 1409, 1409; Card, 2017 ). This can specifically be deemed problematic in relation to people with disabilities, chronic diseases and people of advanced age. They would by definition permanently be missing out on health and accordingly on well-being. However, such a view seems to conflict with the perspectives of relevant groups of people themselves ( Fallon and Karlawish, 2019 : 1104).

Despite the widespread criticism from many different disciplinary backgrounds, the WHO never amended their definition of health. It seems that they did not see a need to change their point of view. In the following section, I will argue that the critique is indeed based on a misunderstanding of the WHO’s perspective.

Interpreting the WHO Definition of Health

As explained, I will argue that the WHO defines health as holistic health, not as perfect health. To bolster this claim about the intentions of the institution, I need to consider the history of its constitution. In this section, I will therefore rely on historical documents, which are in the public domain. In addition, I have benefitted from an enormously helpful recent publication by Lars Thorup Larsen (2022) , who gives a detailed account specifically of the genealogy of the WHO definition, based on archival research.

An important fact that supports my reading of the WHO’s intentions is that the word complete was only inserted into the definition at the very final stages of its conception. It is fairly obvious that it was as a form of editorial amendment, not a substantial change, because otherwise it would have required extensive debate. If the word complete would have fixed the intended definition of health to a perfectionist account, this would have either stirred up a debate or would have had to be uncontroversial. However, there is no evidence in the relevant documents that the draftees of the WHO constitution definitely understood health as perfection. The term complete , according to my reading, was rather intended to clarify the phrase ‘physical, mental and social well-being’, the latter of which had been part of the definition since the drafting period. 6 The word complete summarises and jointly describes the three aspects of well-being. It also adds a rhetorical contrast to the second part of the sentence that denies the sufficiency of the absence of disease or infirmity for health. A perhaps better way to express the notion would have been to state that: health is a state of complete well-being, that is, a state that comprises physical, mental and social elements. But this locution would not have worked straightforwardly in a one-sentence definition, which was apparently aimed at by the WHO.

The late arrival of the term complete of course does not present conclusive evidence that the WHO did not intend to push an account of perfect health. The historical records are not sufficient in this respect. The final draft of the constitution, which had been penned by the Technical Preparatory Committee, was discussed at a meeting in New York City in 1946. 7 The relevant draft definition reads: ‘Health is not only the absence of disease, but also a state of physical and mental well-being and fitness resulting from positive factors, such as adequate feeding, housing and training’ ( WHO, 1947 : 58). The final version, which was eventually adopted, had been prepared by the so-called Committee I, which ‘had given careful consideration to amendments submitted by the delegations of South Africa, Mexico, Australia, Belgium, Netherlands, Chile, United Kingdom, Iran, China, Philippines, Poland, Venezuela, United States of America and Canada’ ( WHO, 1948 : 44). Unfortunately, there are no published minutes or other forms of evidence in relation to this decisive period—decisive, as far as the introduction of the term complete is concerned. We simply do not know who added the word. This would have been important, though, to get a better grasp of the intentions behind the addition. 8

Importantly, many members of the Technical Preparatory Committee, who had been involved to different degrees in the drafting of the WHO constitution, came from a public health background ( Farley, 2008 : 12ff.; Cueto et al ., 2019 : 39ff.). Renowned proponents of so-called social medicine, such as Andrija Štampar, René Sand, Karl Evang and Thomas Parran, were leading members of the drafting group. This is significant because public health usually has a different understanding of the concept of health than clinical medicine. Whereas for the latter, health can be defined as absence of disease ( Smith, 2008 ), that is, in absolute terms, health in public health is a multifarious and scalar notion ( Schramme, 2017 ; Valles, 2018 : 31ff.).

In clinical medicine, health is often understood as absence of disease. This makes sense because the focus is on individual patients. These either have a disease or not. Patients might suffer from a more or less severe disease, but that does not mean that they are more or less diseased than others. Similarly, health over and above the absence of disease is not usually the focus of clinical medicine. If there is no disease, then that is sufficient to establish health. There is no need to refer to health in a positive way, that is, to define it in its own terms.

In contrast, public health scientists usually refer to populations. In their parlance, chosen populations can be more or less healthy than comparison groups. For instance, it might be declared that mine workers are less healthy than millionaires. This does not mean that all mine workers acutely suffer from a disease; rather, it means that they are more likely to fall ill, due to their circumstances of life. Public health has traditionally studied the causes of disease and has made big strides in the prevention of disease. Accordingly, its focus is upstream, as it is sometimes put ( Marmot, 2010 : 41; Venkatapuram, 2011 : 189), towards the conditions that make disease more likely. Health becomes a dispositional term that allows for different grades.

From a public health perspective, it is fairly obvious that health is ‘more than the absence of disease’. It is more in the sense of additionally requiring dispositional elements, not because it is a quantitatively better condition than medical normality (i.e. the absence of disease). People who live in destitute circumstances might not suffer from a disease, but they are often lacking in terms of a sufficient disposition to maintain minimal health.

The public health perspective, therefore, is a gradual perspective on health, allowing parlance of more and less health, or being healthier than others. Although such a perspective does not necessarily lead to an account of perfect health, it is nevertheless compatible with the latter. People with a perfect health disposition—marked by a very low probability to fall ill—might accordingly be deemed in a state of perfect health. Importantly, falling below the ideal point of perfection on a scale does not imply having a disease. In other words, not being perfectly healthy would not constitute a condition of being un healthy; it would merely mean being less healthy than others ( Schramme 2019 : 29ff.). This shows that some of the criticism levied against the WHO definition, even if understood as a perfectionist account, is implausible. More specifically, it does not necessarily follow that, for instance, people with disabilities would be constantly deemed unhealthy because they lack perfect health. As explained, health is not a binary term according to the relevant perspective.

So far, I have argued that the WHO definition is supposed to allow for grades of health. For that purpose, it takes its cue from public health perspectives, though I do not want to claim that it is identical to it. After all, the WHO definition still incorporates the traditional medical perspective on health as absence of disease. There are, nevertheless, important qualms to do with the notion of perfect health. The WHO refers to health as a state of well-being and this might itself be deemed problematic. To be sure, the conceptual connection between health and the good life for human beings has long been established ( Temkin, 1973 ). 9 The connection also makes sense from an experiential point of view. Health has indeed to do with how we fare. Still, if we read the definition as a perfectionist account of health, it would define health as perfect well-being. If that were the case, this would apparently lead to the alleged dangerous confusion of health and happiness mentioned earlier. After all, sufficient health but not happiness seems to be the business of welfare state institutions. It is true, of course, that health care from a public health perspective includes vastly more than just medical care, especially aspects to do with work, education and the environment. Yet, we normally see good reasons to restrict the remit of state institutions to a form of needs provision, basic security and enablement of self-determination (cf. Goodin, 1988 : 363ff.). So, if perfect health were the focus of the state, it would probably end up becoming unjustifiably expansive.

I do not believe that the WHO is guilty of this charge. To be sure, there are reasons for thinking that a public health perspective occasionally tends towards an expansive view of health politics (cf. Preda and Voigt, 2015 ). Yet, it is hardly imaginable that a nascent institution—still precarious in its status at the time of drafting its constitution including the health definition—would intend to basically take over the whole established welfare state agenda and indeed even to expand it by making perfect health a political aim. This is even less credible, as one of the global health institutions predating the WHO, the League of Nations Health Organization , had come under fire for its alleged political overreach during these times of increasing national isolationism ( Cueto et al ., 2019 : 20ff.). There were, accordingly, strong political reasons not to endorse a perfectionist health definition, or at least to keep such ambitions hidden from plain view, especially in 1946, with very fresh memories of the dangers of totalitarianism being abundant. 10

A more science-oriented reason as to why the WHO is unlikely to have opted for an account of perfect health is that such an ideal is not measurable. After all, it refers to an abstract point of reference. To quantify the health statuses of populations, scientists need metrics and they need to determine thresholds. In other words, they need to plot health along a scale. If health were only a hypothetical point on a limitless scale, it would hardly be a useful metric for scientific purposes. Again, this is not a decisive reason to reject the perfectionist interpretation of the WHO definition. But there are numerous publications by health scientists who use the WHO definition without running into the mentioned problems ( Breslow, 1972 ; Greenfield and Nelson, 1992 ). So, it seems that many scientists do not assume the perfectionist health interpretation (see also Ware et al ., 1981 : 621). 11

In contrast, the holistic health interpretation leads to the following point of view: Health is seen as a state of well-being with numerous aspects—physical, mental and social. 12 Given these dimensions of well-being, health statuses can be assessed in a combined approach, taking the full range of health-related factors into account. Importantly, health is not a fictional point at the end of the scale, but any point along a scale. Some people might have a comparatively bad health status, some might be in good health; all will be positioned along a spectrum. From the health definition itself, nothing follows as to when health is good enough or so bad that state institutions need to interfere. In other words, important political decisions regarding thresholds of sufficient health are not prejudged if we follow a holistic health definition. Such a perspective is much more amenable to the political remit of the WHO, which ended up with fairly limited interventionist power (cf. Packard, 2016 : 99ff.; Larsen, 2022 : 123ff.).

The overarching focus of the holistic health interpretation is maintenance of health. It is thereby acknowledged that to counter the various threats to health not only medical means are required, but a dynamic level of physical, mental and social assets. This has been an insight of early public health practitioners. For instance, Henry Sigerist, who evidently had a significant indirect influence on the WHO definition via Raymond Gautier’s draft ( Larsen, 2022 : 119), had already been concerned with the aim of health maintenance. 13 This provides a dynamic element in the conceptualisation of health, which is also implicit in the WHO definition, despite its reference to a state , which seemingly suggests a static view. When Sigerist writes that ‘health is more than the absence of disease’ ( Sigerist, 1932 : 293), this is meant as a conclusion to an argument acknowledging the environmental and social determinants of health. His point becomes quite clear in a later quote:

A healthy individual is a man [ sic! ] who is well balanced bodily and mentally, and well adjusted to his physical and social environment. He is in full control of his physical and mental faculties, can adapt to environmental changes, so long as they do not exceed normal limits; and contributes to the welfare of society according to his ability. Health is, therefore, not simply the absence of disease: it is something positive, a joyful attitude toward life, and a cheerful acceptance of the responsibilities that life puts upon the individual ( Sigerist, 1941 : 100). 14

Sigerist’s terminology, referring to being well balanced, adjusted and in full control, is not aiming towards an ideal of perfection. Rather, he is stating several elements of a good human life within the limits of reality. He believes that health enables an affirmative view of individuals towards their life, not unlimited happiness.

In this section, I have discussed the WHO definition partly from an analytical point of view, in that I distinguished two possible interpretations, a perfectionist and a holistic account of health. I have added historical information regarding the drafting period. Both analytical and historical reasons speak in favour of my thesis that the WHO definition should be read as defining health in a holistic way. Health as complete well-being refers to the full range of factors determining a specific disposition of people to prevent ill health (cf. Ware et al ., 1981 ). This ties in nicely with a more recent official statement by the WHO, the Ottawa Charter, which I will cite as final support of my thesis: ‘[H]ealth is a resource for everyday life, not the objective of living. Health is a positive concept emphasizing social and personal resources, as well as physical capacities’ ( WHO, 1986 ). Health is not the best possible state of well-being but a multifarious instrument, including external as well as internal resources, to pursue a good life.

Why We Need to Distinguish Between Holistic Health and Perfect Health

I have not argued that a conceptualisation of perfect health is wrong-headed or even harmful. Rather, I claimed that perfect health is not the notion that the WHO has been after. It is of import to distinguish between the two notions of health introduced earlier, because confusing them will lead to cross-purposes, not merely in respect to the WHO definition. In this section I will take a closer look at the two health conceptions and discuss the purposes which they can serve. I will also hint at problems with both interpretations that might eventually call for terminological reform.

Holistic health allows to pursue multiple political and economic purposes. For instance, it enables comparisons between groups of people and is especially adept to highlight social inequalities that have an impact on population health. This makes it more pertinent for political purposes than a negative conceptualisation of health as the absence of disease. The latter is absolute or non-comparative and hence does not allow for any interesting information about health-related inequalities between persons.

Importantly, in contrast to perfect health, the scope of holistic health can be contoured by thresholds. As explained, complete well-being can be understood as having all elements that are constitutive of it. What exactly that means in relation to health is of course contested, and I have already insinuated that the WHO did not set a threshold, perhaps intentionally. Still, the required level of holistic health could be determined via political decision-making processes. This makes holistic health open for different substantial interpretations and hence political ambitions.

Despite these advantages, the conceptualisation of health as holistic health has serious drawbacks. 15 Most significantly, the distinction between health conditions and determinants of health becomes blurry ( Bickenbach, 2017 : 968, 968; van Druten et al ., 2022 : 2). 16 Environmental and social determinants of health come with certain probabilities, sometimes unknown, to fall ill or to stay healthy, but they are not constituents of medical conditions themselves; rather, they are their presumed causes ( Whitbeck, 1981 : 617). As we have seen in the previous example of miners’ health, a poor health disposition is not the same as being unhealthy, that is, suffering from disease or illness. 17

The potential confusion between poor health dispositions and disease or illness leads to normative confusion as well, especially when we are assessing claims of justice. Disease has a different normative status than a relatively bad health disposition. Arguably, disease has an immediate urgency in relation to human needs, in terms of threatening or involving harm. A comparatively high propensity to fall ill or membership in a vulnerable population as such does not obviously have such normative urgency. Important normative discussions about health justice are short-circuited if we transfer direct urgency to alleviating relatively poor holistic health statuses without thinking about the impact on the lives of real people and merely consider relative positions.

One way forward would be to acknowledge the basic insights of a holistic conceptualisation of health but to nevertheless distinguish between health as a condition of an individual and health-related traits and circumstances that have an impact on the maintenance of individual and population health. We would accordingly need a more adequate term than health for combining both of these aspects—an organismic condition, that is, health in the more narrowly medical sense, and a set of health-related resources. Such a revisionary conceptual perspective can only be alluded to here (see Davies and Schramme, 2022 ).

Accounts of perfect health have a different purpose than accounts of holistic health. The former set an ideal; an ambitious target for individual or social aspiration. According to this perspective, a person can always be potentially healthier, because there is no fixed point on a scale which suffices for health. It seems to me that such an interpretation of health is fully adequate for specific purposes, for instance, introducing a utopian goal and to stop people from becoming complacent about an important element of a good human life. Perfect health shares features with traditional accounts of the virtues, although it is not itself supposed to be a virtue. Virtues are similar to perfect health in that they describe human excellences. Virtues are excellences of character, or perfect dispositions to act fully adequately; health is excellence in relation to well-being, or a perfect organismic disposition to keep harmful and disadvantageous conditions at bay. Becoming virtuous can be an aspiration for human beings and so can becoming perfectly healthy.

However, there is a danger of imposing such an ideal on everyone. If we always have to strive for more health, then we might lose sight of other values, such as pursuing friendships, taking risks or enjoying unhealthy choices. This is a real risk in many modern societies, where health has been turned into a kind of religion and individual mission ( Katz, 1997 ). Socially, similar developments can be studied in relation to so-called ‘healthism’ and generally the moralisation of health ( Conrad, 1992 ). 18 The problems intensify if health dispositions and risk factors are not clearly distinguished from health conditions. Every single action a person pursues might have an impact on their health, according to the perfectionist health account. Hence, if combined with a prescriptive reading of the ideal—as something to be sought—then health can turn into a totalitarian imperative. This would clearly undermine the initial purpose of setting an ideal.

Whether perfect health will fail to meet its purposes will be established by experience and through history. It is not a necessary feature of the account. As mentioned, there are warning signs. However, more importantly, there is a need to clearly distinguish between holistic health and perfect health because perfect health, in contrast to holistic health, should never be the remit of state institutions.

Conclusions

‘Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ ( WHO, 1948 : 100). This definition allows for two different interpretations. A perfectionist account, where health describes a hypothetical, perfect state of well-being, or a holistic account, where health is a state of exhaustive well-being, including all relevant dimensions of its constitutive elements. I have argued that the WHO intended to support a holistic account. I provided analytical and historical reasons for this point of view.

To distinguish between the two interpretations of health is important for systematic reasons as well, not merely in relation to the proper interpretation of the WHO’s definition of health. The two different accounts serve different purposes and run into different types of problems, as I have highlighted in this paper. Still, both are perfectly valid notions of health.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Lars Thorup Larsen and one of the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments.

1 There can, of course, be even more than just these two conceptualisations of health. For instance, many would probably define health simply in terms of the absence of disease or illness. Indeed, one of the reasons why the WHO definition has raised concerns is probably due to its explicit diversion from the widespread conceptualisation in negative terms, that is, as absence of something.

2 The Oxford Dictionary of English (2015) entry on the adjective forms of complete states: ‘1. having all the necessary or appropriate parts: a complete list of courses offered by the university | no woman’s wardrobe is complete without this pretty top ( … ) 2. [attributive] (often used for emphasis) to the greatest extent or degree; total: a complete ban on smoking | their marriage came as a complete surprise to me ’.

3 The term holistic has been used in relation to health by Lennart Nordenfelt (see Nordenfelt, 1995 : 12ff., 35ff.). By using this term, I do not want to claim that Nordenfelt endorses the WHO definition.

4 A slightly different distinction between two meanings of the concept of complete— complete in an ‘all-or-nothing sense’ and in a sense that ‘admits of degrees’—has been drawn by Sissela Bok in relation to the WHO definition ( Bok, 2008 : 592). In passing, I also want to note that the label perfectionist is of course not supposed to refer to perfectionism in value theory, where it denotes an objective theory of the good.

5 Possibly the first philosopher of medicine to take note of this feature and the likely consequences was Owsei Temkin: ‘I do not think that I read too much into this formula [the WHO definition] if I believe that it tends to include moral values and to identify health with happiness. ( … ) But is the pursuit of happiness itself wholly a medical matter? Our life has many values and ( … ) happiness can sometimes be achieved at the sacrifice of health. ( … ) [I]f health is defined so broadly as to include morality, then the danger exists that the physician will also be burdened with all the duties of the medieval priest’ ( Temkin, 1949 : 20).

6 This needs to be qualified, because the term social was introduced fairly late in the drafting process. However, the point I am making here is to do with the fact that elements of well-being had been listed for some time during the drafting period and that the word complete was added to characterise these elements jointly.

7 The Technical Preparatory Committee itself relied on earlier drafts of senior members of related institutional bodies, especially the League of Nations Health Organization ( Larsen, 2022 ). Larsen gives a detailed account of the origins of the WHO definition, tracing it back to Henry Sigerist’s influential publications in the history, sociology and philosophy of medicine, dating mainly from the 1930ies. Sigerist’s ideas were not revisionary or highly original, though, at least not in its focus on positive health. The idea that health includes elements that cannot be captured by the phrase ‘absence of disease’ goes back to antiquity. Especially the notion of health as a form of equilibrium and—in modern terms—resilience has been known for centuries ( Edelstein, 1967 : 303ff.). So, even if Sigerist’s work probably had a role in finding the relevant formulations, the underlying ideas had been prevalent.

8 One of the members of the Technical Preparatory Committee, Szeming Sze, recalled 40 years later that James H.S. Gear ‘improved the wording’ ( WHO, 1988 : 33). However, there is no identifiable evidence to corroborate Sze’s recollection.

9 The notion of well-being here is a state of a person including their circumstances. It should not be interpreted as a mental state only, that is, as a kind of feeling.

10 It should also not be forgotten that the early focus of public health institutions, including the precursors of the WHO, was on the prevention of diseases, specifically communicable diseases. This speaks against assuming a focus on health enhancement.

11 Indeed, numerous researchers claim that although the WHO definition sets a political ambition, its main purpose is to set a framework that makes health measurable ( Salomon et al ., 2003 ; Rubinelli et al ., 2018 ; cf. Chatterji et al ., 2002 ).

12 In line with this reading, in more recent years, there was also a discussion in the WHO whether to add spiritual well-being to the definition ( WHO, 1997 : 2; cf. Larson, 1996 ; Nordenfelt, 2016 : 214). The discussion around a fourth aspect of well-being did not lead to official changes, though.

13 Bok also mentions that Sigerist was a close friend of Štampar’s, who was—as mentioned earlier—a member of the drafting group ( Bok, 2008 : 594).

14 Georges Canguilhem similarly declared that ‘[h]ealth is a set of securities and assurances ( … ), securities in the present, assurances for the future’ ( Canguilhem, 1966 : 198).

15 Surely not everyone would see the political negotiability of adequate health thresholds as an advantage. However, I am here concerned with a relative advantage over the perfectionist account of health.

16 Once the determinants of health are confused with health itself, there is an additional danger of conceptualising immorality and incivility as forms of health disruptions (cf. Farley 2008 : 56). WHO officials were not immune to this problem. For instance, in a memorandum called International Health of the Future (1943), Gautier wrote: ‘For health is more than the absence of illness; the word health implies something positive, namely physical, mental, and moral fitness. This is the goal to be reached’ ( Larsen, 2022 : 117; see also Chisholm, 1946 : 16; cf. Cueto et al ., 2019 : 33).

17 The otherwise philosophically important distinction between disease and illness does not matter for the purposes of my essay. I use the terms interchangeably for ease of reading.

18 An important and still highly recommendable early critique of the utopian standard of health is Rene Dubos’s Mirage of Health ( Dubos, 1959) .

- Bickenbach, J. (2017). WHO’s Definition of Health: Philosophical Analysis . In Schramme, T. and Edwards, S. (eds), Handbook of the Philosophy of Medicine . Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 961–974. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bok, S. (2008). WHO Definition of Health, Rethinking the . In Heggenhougen, H. K. (ed.), International Encyclopedia of Public Health . Amsterdam: Elsevier, pp. 590–597. [ Google Scholar ]

- Breslow, L. (1972). A Quantitative Approach to the World Health Organization Definition of Health: Physical, Mental and Social Well-being . International Journal of Epidemiology , 1 , 347–355. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Callahan, D. (1973). The WHO Definition of “Health” . The Hastings Center Studies , 1 , 77–87. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Canguilhem, G. (1966). The Normal and the Pathological . New York: Zone Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Card, A. (2017). Moving Beyond the WHO Definition of Health: A New Perspective for an Aging World and the Emerging Era of Value-Based Care . World Medical & Health Policy , 9 , 127–137. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chatterji, S., Ustün, B. L., Sadana, R., Salomon, J. A., Mathers, C. D. and Murray, C. J. L. (2002). The Conceptual Basis for Measuring and Reporting on Health . Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy Discussion Paper No. 45, World Health Organization. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chisholm, G. B. (1946). The Reëstablishment of Peacetime Society . Journal of the Biology and the Pathology of Interpersonal Relations , 9 , 3–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Conrad, P. (1992). Medicalization and Social Control . Annual Review of Socioliology 18 , 209–232. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cueto, M., Brown, T. M., and Fee, E. (2019). The World Health Organization: A History . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davies, B., Schramme, T. (2022). Health Capital and its Significance for Health Justice . Manuscript. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dubos, R. (1959). Mirage of Health: Utopias, Progress, and Biological Change . New York: Harper & Brothers. [ Google Scholar ]

- Edelstein, L. (1967). Ancient Medicine: Selected Papers of Ludwig Edelstein . Edited by Owsei T. and Lilian Temkin, C. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fallon, C. K. and Karlawish, J. (2019). Is the WHO Definition of Health Aging Well? Frameworks for “Health” After Three Score and Ten . AJPH , 109 , 1104–1106. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Farley, J. (2008). Brock Chisholm, The World Health Organization, and the Cold War . Vancouver: UBC Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodin, R. E. (1988). Reasons for Welfare. The Political Theory of the Welfare State . Princeton: Princeton University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenfield, S. and Nelson, E. C. (1992). Recent Developments and Future Issues in the Use of Health Status Assessment Measures in Clinical Settings . Medical Care , 30 , MS23–MS41. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huber, M., et al.. (2011). Health: How Should We Define It ? British Medical Journal , 343 , 235–237. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kass, L. (1975) Regarding the End of Medicine and the Pursuit of Health . Public Interest 40 : 11–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Katz, S. (1997). Secular Morality . In Brandt, A. M. and Rozin, P. (eds.), Morality and Health . London: Routledge, pp. 297–330. [ Google Scholar ]

- Larsen, L. T. (2022). Not Merely the Absence of Disease: A Genealogy of the WHO’s Positive Health Definition . History of the Human Sciences , 35 , 111–131. [ Google Scholar ]

- Larson, J. S. (1996). The World Health Organization’s Definition of Health: Social Versus Spiritual Health . Social Indicators Research , 38 , 181–192. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leonardi, F. (2018). The Definition of Health: Towards New Perspectives . International Journal of Health Services , 48 , 735–748. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Marmot, M. (2010). Fair Society, Healthy Lives—The Marmot Review . Institute of Health Equity. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nordenfelt, L. (1995). On the Nature of Health: An Action-Theoretic Approach . 2nd Revised and Enlarged Edition. Dordrecht: Kluwer. [ Google Scholar ]

- Nordenfelt, L. (2016). A Defence of a Holistic Concept of Health . In Giroux, É. (ed.) Naturalism in the Philosophy of Health: Issues and Implications . Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 209–225. [ Google Scholar ]

- Oxford Dictionary of English. 3rd edn. Edited by Stevenson, A. Oxford University Press. Current Online Version: 2015 [ Google Scholar ]

- Packard, R. M. (2016). A History of Global Health: Interventions into the Lives of Other Peoples . Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Preda, A. and Voigt, K. (2015). The Social Determinants of Health: Why Should We Care ? The American Journal of Bioethics , 15 , 25–36. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rubinelli, S., Cieza, A., and Stucki, G. (2018). Health and Functioning in Context . In Riddle, C. A. (ed.), From Disability Theory to Practice: Essays in Honor of Jerome E. Bickenbach . Lanham: Lexington Books, pp. 121–131. [ Google Scholar ]

- Salomon, J. A., Mathers, C. D., Chatterji, S., Sadana, R., Üstün, T. B., and Murray, C. J. L. (2003). Quantifying Individual Levels of Health: Definitions, Concepts, and Measurement Issues . In Evans, D. B. and Murray, C. J. L. (eds), Health Systems Performance Assessment . Geneva: World Health Organization, pp. 301–318. [ Google Scholar ]

- Saracci, R. (1997). The World Health Organisation Needs to Reconsider Its Definition of Health . BMJ , 314 , 1409–1410. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schramme, T. (2017). Health as Notion in Public Health . In Schramme, T. and Edwards, S. (eds), Handbook of the Philosophy of Medicine . Dordrecht: Springer, pp. 975–984. [ Google Scholar ]

- Schramme, T. (2019). Theories of Health Justice: Just Enough Health . London: Rowman & Littlefield Int. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sigerist, H. E. (1932). Man and Medicine . New York: W.W. Norton. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sigerist, H. E. (1941). Medicine and Human Welfare . New Haven: Yale University Press. [ Google Scholar ]