- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

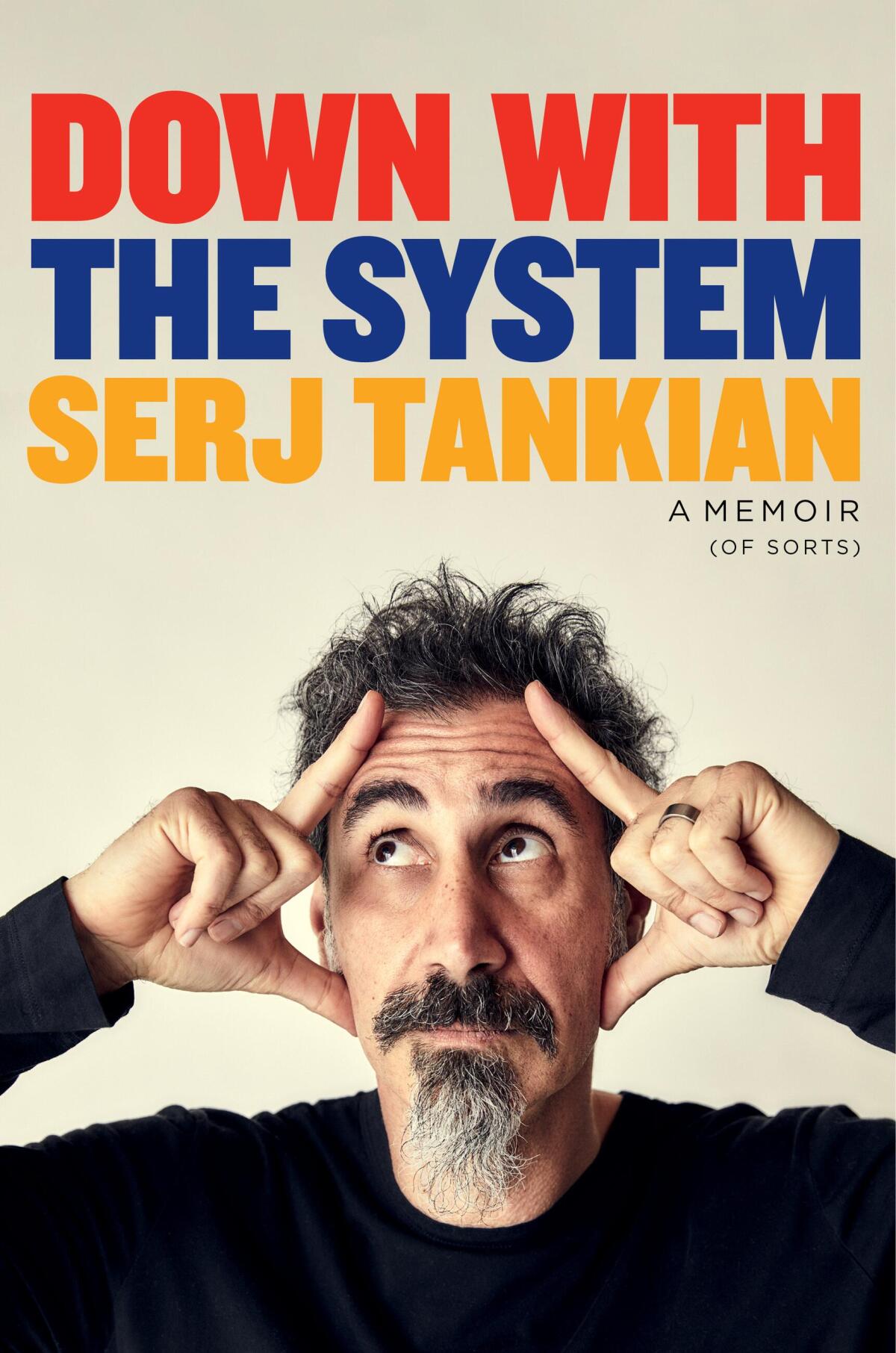

Armenian Genocide

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 26, 2021 | Original: October 1, 2010

The Armenian genocide was the systematic killing and deportation of Armenians by the Turks of the Ottoman Empire. In 1915, during World War I , leaders of the Turkish government set in motion a plan to expel and massacre Armenians. By the early 1920s, when the genocide finally ended, between 600,000 and 1.5 million Armenians were dead, with many more forcibly removed from the country. Today, most historians call this event a genocide: a premeditated and systematic campaign to exterminate an entire people. In 2021, U.S. President Joe Biden issued a declaration that the Ottoman Empire’s slaughter of Armenian civilians was genocide. However, the Turkish government still does not acknowledge the scope of these events.

Kingdom of Armenia

The Armenian people have made their home in the Caucasus region of Eurasia for some 3,000 years. For some of that time, the kingdom of Armenia was an independent entity: At the beginning of the 4th century A.D., for instance, it became the first nation in the world to make Christianity its official religion.

But for the most part, control of the region shifted from one empire to another. During the 15th century, Armenia was absorbed into the mighty Ottoman Empire .

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman rulers, like most of their subjects, were Muslim. They permitted religious minorities to maintain some autonomy, but they also subjected Armenians, whom they viewed as “infidels,” to unequal and unjust treatment. Christians paid higher taxes than Muslims, for example, and had very few political or legal rights.

In spite of these obstacles, the Armenian community thrived under Ottoman rule. They tended to be better educated and wealthier than their Turkish neighbors, who in turn grew to resent their success.

This resentment was compounded by suspicions that the Christian Armenians would be more loyal to Christian governments (that of the Russians, for example, who shared an unstable border with Turkey) than they were to the Ottoman caliphate.

These suspicions grew more acute as the Ottoman Empire began to crumble: At the end of the 19th century, the despotic Turkish Sultan Abdul Hamid II—obsessed with loyalty above all, and infuriated by the nascent Armenian campaign to win basic civil rights—declared that he would solve the “Armenian question” once and for all.

“I will soon settle those Armenians,” he told a reporter in 1890. “I will give them a box on the ear which will make them…relinquish their revolutionary ambitions.”

First Armenian Massacre

Between 1894 and 1896, this “box on the ear” took the form of a state-sanctioned pogrom.

In response to large-scale protests by Armenians, Turkish military officials, soldiers and ordinary men sacked Armenian villages and cities and massacred their citizens. Hundreds of thousands of Armenians were murdered.

Young Turks

In 1908, a new government came to power in Turkey. A group of reformers who called themselves the “Young Turks” overthrew Sultan Abdul Hamid and established a more modern constitutional government.

At first, the Armenians were hopeful that they would have an equal place in this new state, but they soon learned that what the nationalistic Young Turks wanted most of all was to “Turkify” the empire. According to this way of thinking, non-Turks—and especially Christian non-Turks—were a grave threat to the new state.

World War I Begins

In 1914, the Turks entered World War I on the side of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. (At the same time, Ottoman religious authorities declared a holy war against all Christians except their allies.)

Military leaders began to argue that the Armenians were traitors: If they thought they could win independence if the Allies were victorious, this argument went, the Armenians would be eager to fight for the enemy.

Indeed, as the war intensified, Armenians organized volunteer battalions to help the Russian army fight against the Turks in the Caucasus region. These events, and general Turkish suspicion of the Armenian people, led the Turkish government to push for the “removal” of the Armenians from the war zones along the Eastern Front.

Armenian Genocide Begins

On April 24, 1915, the Armenian genocide began: That day, the Turkish government arrested and executed several hundred Armenian intellectuals.

After that, ordinary Armenians were turned out of their homes and sent on death marches through the Mesopotamian desert without food or water.

Frequently, the marchers were stripped naked and forced to walk under the scorching sun until they dropped dead. People who stopped to rest were shot.

At the same time, the Young Turks created a “Special Organization,” which in turn organized “killing squads” or “butcher battalions” to carry out, as one officer put it, “the liquidation of the Christian elements.”

These killing squads were often made up of murderers and other ex-convicts. They drowned people in rivers, threw them off cliffs, crucified them and burned them alive. In short order, the Turkish countryside was littered with Armenian corpses.

Records show that during this “Turkification” campaign, government squads also kidnapped children, converted them to Islam and gave them to Turkish families. In some places, they raped women and forced them to join Turkish “harems” or serve as slaves. Muslim families moved into the homes of deported Armenians and seized their property.

Though reports vary, most sources agree that there were about 2 million Armenians in the Ottoman Empire at the time of the massacre. In 1922, when the genocide was over, there were just 388,000 Armenians remaining in the Ottoman Empire.

Did you know? American news outlets have also been reluctant to use the word “genocide” to describe Turkey’s crimes. The phrase “Armenian genocide” did not appear in The New York Times until 2004.

Aftermath and Legacy

After the Ottomans surrendered in 1918, the leaders of the Young Turks fled to Germany, which promised not to prosecute them for the genocide. (However, a group of Armenian nationalists devised a plan, known as Operation Nemesis , to track down and assassinate the leaders of the genocide.)

Ever since then, the Turkish government has denied that a genocide took place. The Armenians were an enemy force, they argue, and their slaughter was a necessary war measure.

Turkey is an important ally of the United States and other Western nations, and so their governments had been slow to condemn the long-ago killings. In March 2010, a U.S. Congressional panel voted to recognize the genocide. On October 29, 2019, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution that recognized the Armenian genocide. And on April 24, 2021, President Biden issued a statement, saying, "The American people honor all those Armenians who perished in the genocide that began 106 years ago today.”

The Armenian Genocide (1915-1916): Overview. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Holocaust Encyclopedia . Armenian Genocide (1915-1923). Armenian National Institute . Armenian Genocide. Yale University: Genocide Studies Program .

HISTORY Vault: World War I Documentaries

Stream World War I videos commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The Armenian Genocide unofficially began with the arrest of 250 Armenian intellectuals by Turkish officials on April 24, 1915. Over the next several years a series of systematic deportations and mass executions along with intentional starvation would cause the deaths of more than one million Armenians. The aftermath left the remaining Armenian population scattered, resulting in one of the greatest diasporas in the twentieth century.

Below is a condensed history of the Armenian Genocide, beginning with the life of the Armenians before the genocide and extending to the genocide's legacy today.

The Armenians before the Genocide

The Armenians and other Christian communities, including the Greeks and Assyrians, were significant minorities in the Ottoman Empire. Despite being a multi-religious and multi-ethnic state with members from all three of the great monotheistic religions (Islam, Christianity, and Judaism), the empire was dominated by ethnic Turks. The second half of the 19th century, saw the rise of Turkish nationalism that placed emphasis on the ethnic and religious identity of the majority element of the empire to the growing detriment of religious and ethno-religious minorities inhabiting the country. Beset by a series of military defeats, an ever-shrinking economy, and an overall political instability on both domestic and international fronts, the Ottoman Empire eventually turned inwards. The various Turkish nationalist movements meanwhile grew both in strength and stature, a growing sign of their influence being the nearly overnight proliferation of literature and articles that touted the uniqueness and supremacy of Turkish civilization.

The military losses that saw the further fragmentation of the empire and the ensuing reactionary nationalism would have a disastrous impact on Empire’s remaining Christian minorities, but especially the Armenian community. It left them as one of the largest Christian groups in the Ottoman Empire, geographically largely confined to Eastern Anatolia and away from other Christian populations, and thus especially vulnerable to political abuse and collective violence. Although throughout the centuries Armenians had been considered the “loyal nation,” and had risen to economic and civic prominence in the most important of imperial urban centers and in the capital, with the rise of Turkish nationalism their situation was becoming increasingly intolerable and untenable. The first Armenian political parties established around this period sought to address the increasing vulnerability of the Armenian cultural life in the empire, seeking political and economic reforms that would alleviate the growing discrimination towards the Armenian minority. This growing Armenian political awareness on one hand, and their economic overachievement in the Sultan’s domain on the other, would contribute to the atmosphere of distrust between Turks and Armenians.

The Armenian question, long a fixture of European and Ottoman diplomacy, was now becoming a fiercely debated topic of highest importance in Turkish politics. Political and economic reforms advocated by European powers and at least on paper embraced by Ottoman authorities was fast becoming a mere afterthought given how fast events on the ground were developing. Tensions would ultimately come to a head when a series of pogroms were unleashed against the Armenians and to a lesser extent against other Christian groups in the empire. The Hamidian massacres of 1894-1896 claimed the lives of hundreds of thousands of Armenians, serving, in the words of one Armenian historian, as a “dress rehearsal” for the Armenian Genocide of 1915.

In the years leading up to the genocide, the Ottoman authorities would further tighten the restrictions for learning, property ownership, and religious practices for minorities, including the Armenians, in the empire. This would foreshadow future events.

The Armenian Genocide

It can be difficult to pinpoint an exact date when the Armenian Genocide begins because it was the culmination of a series of policies targeting the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian population. In February 1915, Armenians serving in the Ottoman army were removed from active duty and forced into labor battalions. However, April 24, 1915 is widely considered the date the genocide began because it was then that Turkish authorities arrested 250 Armenian intellectuals. The reason given was fear that the Armenians were in league with Russia, the Ottoman Empire’s historic rival, and could serve as a potential fifth column. The hysteria created by World War I created a perfect cover for the Ottoman government led by the nationalist ruling party of Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), a.k.a. the Young Turks, to set in motion its genocidal plan against their Armenian fellow citizens.

In May 1915, the deportation of the Armenians from Empire’s eastern provinces began apace. A series of consecutive laws passed by the Turkish government gave it the right to confiscate or otherwise impound Armenian properties and businesses left behind by the departing deportees as a wartime necessity. Other restrictions of similar or harsher nature soon followed, leaving the Armenian population defenseless, property-less, and generally destitute. Forced marches, massacres became more commonplace and widespread, especially on deportation routes. The Turkish military instituted a number of gruesome methods to exterminate the Armenian population, some of which would be adopted and refined by the Nazis a mere 25 years later. Those who were not killed outright by the military often faced starvation along the way. Rapes of women and girls were also commonplace.

The Armenians who managed to survive the marches were sent on foot to concentration camps created by the Ottoman military. These camps were located near modern Turkey’s southern border, in the Syrian desert of Deir ez-Zor. The Turkish government routinely withheld food and water from the Armenians in the camp. The lack of nourishment, coupled with unsanitary conditions and widespread disease, meant life expectancy at the camps was extraordinarily short. Armenian women and girls were often sold while in the camps by Turkish gendarmes to local Arab bedouins and chieftains. Many of the Armenian women were also routinely abducted and taken as forced brides by Turkish and Kurdish militiamen.

Much of the genocide would come to an end in 1918 with the conclusion of World War I.

Reaction to the Genocide

The international community was fully aware of the genocide as it was unfolding. Several European countries and the United States had active consular missions throughout the Ottoman Empire providing a detailed account of events during the Armenian Genocide. In addition, Christian missionary organizations and charities were also active in the area at the time. It is through these missions that newspapers of the period were able to get regular updates on the events in Turkey. In the years after the genocide, several western witnesses to the atrocities would publish their own accounts, most notably Henry Morgenthau , the former US Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire.

Aid groups, especially from the United States, sent groups to provide relief to the Armenian people. In the aftermath of the genocide, thousands of Armenian people were adopted by westerners. In all, relief groups raised more than $100 million to provide aid to more than two million Armenian refugees.

Between 1919 and 1920, a series of Turkish court cases issued guilty verdicts to the Three Pashas, three senior officials and orchestrators of the genocide. These convictions were for naught, as all three had left the country. One hundred and fifty Turkish men implicated in the genocide were arrested by Allied authorities and sent to Malta for trial. All the detainees would eventually be returned to Turkey without trial. In the end, there was no punishment for those involved with the Armenian Genocide.

The lack of justice inspired Polish law student Raphael Lemkin to begin his work defining the term genocide. The massacres against Armenians influenced Lemkin’s drafting of a law to punish and prevent genocide. Although it would take more than 20 years, Lemkin would eventually see the crime of genocide made illegal by the international community when the United Nations passed the Genocide Convention in 1948.

The Armenian Genocide, Denial, and Memory

As the first of the modern genocides, the Armenian Genocide holds a complicated place in world history. For decades, the Armenian community, dispersed throughout the globe, struggled with recognition. Today, more than twenty countries officially acknowledge the atrocities as genocide. Uruguay was the first to officially recognize the genocide back in 1965. Several countries, including Austria, Switzerland, Slovakia and, most recently, Cyprus in early April 2015, have gone as far to make genocide denial a crime.

The topic of recognition is a largely political issue in the United States. Turkey is seen as a strategic ally, especially post 9/11, making leaders in Washington, DC cautious about officially recognizing the genocide. However, 48 states have taken steps to officially call the massacre of the Armenians genocide, the latest state to do so being Indiana. In Minnesota, the genocide was first marked by a proclamation by Governor Jesse Ventura.

Two countries officially deny the Ottoman government’s role in the elimination of the Armenian community—Azerbaijan and Turkey. Turkey has taken a far more aggressive approach to genocide denial, threatening lawsuits and calling into question the authenticity of academic research into the Armenian Genocide. One famous example is Dr. Taner Akçam, a Turkish scholar. Dr. Akçam has written extensively on the Armenian Genocide, and came under harsh criticism by Turkish or pro-Turkish scholars. In 2007, while a guest lecturer at the University of Minnesota, Dr. Akçam was sued under Turkey’s laws that forbid ‘insulting Turkish-ness.’ The lawsuit was eventually thrown out. The University of Minnesota itself was sued by a pro-Turkish American organization which questioned the authenticity of materials found on the Center for Holocaust & Genocide Studies website. In 2011, this suit was also dismissed.

Besides lawsuits, threats of lawsuits, and public denunciation by Turkish officials the denial of the Armenian Genocide has also academic dimensions with studies designed to cast doubt on the veracity of eyewitness reports, consular dispatches from sites of massacres, and relativization of the numbers of persons killed. Despite the persistence of denial, the overwhelming majority of historians and genocide scholars agree that the massacres of the Armenian citizens of the Ottoman Empire cannot but be classified as genocide, given the intent of the perpetrators, the scope of the massacres, and their social, demographic and cultural consequences.

Beyond the reach of international politics, the legacy of the Armenian Genocide continues to be explored by a new generation of Armenians and Armenian-Americans through film, music, and literature.

Further Reading

For more information on the Armenian Genocide, denial, and memory, check out:

- Killing Orders: Talat Pasha’s Telegrams and the Armenian Genocide , by Taner Akçam. This new book by acclaimed Turkish historian offers a fresh new take on documents showing criminal intent on the part of the Turkish rulers during the Genocide and refutes contemporary denial of the Armenian Genocide through primary sources and meticulous research.

- Denial of Violence: Ottoman Past, Turkish Present, and Collective Violence Against the Armenians, 1789-2009 , by Fatma Müge Göçek. University of Michigan sociologist Fatma Müge Göçek tackles the Armenian Genocide and its denial in this groundbreaking study of original Turkish sources by tracing the emergence of the official Turkish narrative from its origins to its present-day form.

- “Professional Ethics and the Denial of Armenian Genocide,” by Roger W. Smith, Eric Markusen, and Robert Jay Lifton. In this article published in the Journal of Holocaust and Genocide studies, a trio of American genocide scholars unveil the secret correspondence between former Princeton University historian Heath Lowry and the Turkish Ambassador to the United States wherein Prof. Lowry offers to ghost-write a letter on behalf of the Turkish ambassador to Robert Jay Lifton and protest latter’s inclusion of the Armenian Genocide in his book on Nazi doctors. It tackles the broader issue of professional ethics and genocide denial in the academia.

- My Grandmother: An Armenian-Turkish Memoir , by Fethiye Çetin. This book by Turkish human rights activist and prominent lawyer Fethiye Çetin details her discovery of her Armenian roots, which had been an elaborate and decades-long family secret.

Court Dismisses Turkish Coalition Lawsuit Filed Against the University of Minnesota

On March 30, 2011, US District Court Judge Donovan Frank dismissed a lawsuit filed by the Turkish Coalition of America against the University of Minnesota. The lawsuit arose from materials posted on the university’s Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies (CHGS) website, including a list of websites CHGS considered “unreliable” for purposes of conducting scholarly research. The Turkish Coalition claimed the university violated its constitutional rights, and committed defamation, by including the Turkish Coalition website on the “unreliable” websites list.

Related News Articles:

- U.S. Court of Appeals Rules in Favor of the University of Minnesota in Case Involving the Turkish Coalition of America : Minnesota Public Radio News (5-4-2012)

- An Academic Right to an Opinion : Inside Higher Ed (5-4-2012)

- Judge Throws Out Genocide ‘Blacklist’ Case : MN Daily (3-31-2011)

- Unusual Ruling for Academic Freedom : Inside Higher Ed (3-31-2011)

- Lawsuit Brewing Over U Website Warnings : MN Daily (11-22-2010)

- Turkish Group Sues U for ‘Unreliable’ Website list : MN Daily (11-30-2010)

- Suit Over 'Unreliable Websites' : Inside Higher Ed (12-1-2010)

- Documents: The Turkish Coalition Lawsuit Against the U of Minnesota : MPR News (12-01-2010)

- An Unreliable Source : MN Daily (12-06-2010)

- Turkish Lobby: We Were Blacklisted : MN Daily (12-07-2010)

- Unlikely Foes : Inside Higher Ed (12-20-2010)

- Critical Thinking’ or Genocide Denial? TCA vs. U. of Minn : Armenian Weekly (1-10-2011)

Bruno Chaouat, Director of the Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies in 2011, said of the ruling: “This is an important victory for scholars and educators all over the United States. I want first to express my gratitude to General Counsel at the University of Minnesota, and in particular to Brent Benrud, for his outstanding work on this case. I applaud Judge Frank’s decision, as it bears witness to the high esteem in which the judicial system in this country holds academic freedom. This outcome honors the principles of freedom of speech, and is a remarkable example of the law’s protection of free inquiry into matters of public interest.”

Genocide Studies Program

Armenian genocide.

The Armenian minority in Ottoman Turkey had been subject to sporadic persecutions over the centuries. In 1894-96, these were stepped up with pogrom-like massacres. With the outbreak of the First World War, the Young Turk government proceeded far more radically against the Armenians. From 1915, inspired by rabid nationalism and secret government orders, Turks drove the Armenians from their homes and massacred them in such numbers that outside observers at the time described what was happening as ‘a massacre like none other,’ or ‘a massacre that changes the meaning of massacre.’ Although we do not have reliable figures on the death toll, many historians accept that between 800,000 and one million people were killed, often in unspeakably cruel ways, or marched to their deaths in the deserts to the south. Unknown numbers of others converted to Islam or in other ways survived but were lost to the Armenian culture. At the time a number of influential people spoke out against these atrocities, most notably the distinguished historian Arnold J. Toynbee, but it has only been since the 1970s that scholars have devoted anything like sustained attention to this human catastrophe. There is more than enough evidence to suggest that the mass murder of the Armenians was a case of genocide, as that crime was subsequently defined in the United Nations Genocide Convention of 1948. Surviving perpetrators of the Armenian genocide could certainly have been held to account in an international criminal court.

- Advanced Search

Version 1.0

Last updated 26 may 2015, armenian genocide.

In early 1915 the Young Turk government of the Ottoman Empire decided to deport hundreds of thousands of Armenians and Assyrians from their homes into distant parts of the Empire, eventually into the deserts of Syria. Armenian soldiers in the Ottoman Army were demobilized and massacred; women and children were driven on long marches, starved, beaten, and often murdered. These events have been called the first major genocide of the 20 th century, but the government of the Turkish state and many of its supporters deny that a genocide took place; rather, they claim that the government acted to suppress an Armenian insurrection and people were killed in the process. New scholarship confirms that the Ottoman government intended the elimination of Armenians and Assyrians to render them impotent in the contest for lands in eastern Anatolia.

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Background of Ethnic and Religious Minorities

- 3 Young Turk Revolution 1908

- 4 Turkish Nationalism and the Catastrophic Results of the War for Armenians

- 5 The “Evolution” of Armenian Genocide

- 6 Mass Deportation, Forced Marches, and Death Camps

- 7 The Politics behind the Genocide

- 8 Genocide as Response to Crisis

- 9 Conclusion

Selected Bibliography

Introduction ↑.

Historians generally have explained (or excused) the Turkish deportations and massacres of the Armenians during the First World War as the result of conflicting ideologies, religious or nationalist; as the understandable and justified response of the Young Turk triumvirate to Armenian subversion in time of war; or as a long-planned elimination of non-Turks in Anatolia to create a national homeland for the Turkish people. Such ideological or political explanations necessarily focus on the leadership of the two peoples in conflict - the Ottoman government and the Armenian revolutionaries - without full examination of deeper causes and the broad social and demographic dimensions of the late Ottoman environment. While a focus on the political and intellectual elites is essential to explain the instigating events of early 1915 that precipitated the Armenian tragedy, the scope of the killing and the degree of popular violence on the part of ordinary Turks, Kurds, Circassians, and others, requires investigation of both the complex evolution of interethnic relations of the Ottoman peoples as well as consideration of the international competition among the Great Powers that constrained Ottoman decision makers. Existing histories have looked upon Armenians as little more than innocent victims, without understanding their intimate connections to Ottoman society (which in part explains the passivity of the overwhelming majority), or examining the ideologies and influences that encouraged a committed minority to engage in armed resistance. Historians must ponder why the relatively benign symbiosis of several centuries, during which the ruling Ottomans referred to the Armenians as the "loyal millet" ( millet-i sadika ), broke down into the genocidal violence of 1915. What were the experiences and perceptions, the cognitive conclusions and affective understandings of Ottoman leaders and ordinary people, which led to the mass killing of hundreds of thousands of Armenian and Assyrian subjects of the Ottoman Empire ?

The Background of Ethnic and Religious Minorities ↑

Armenians , like Assyrians, Greeks, Jews, and other non-Sunni Muslim peoples of the Empire , were not only an ethnic and religious minority in a country dominated demographically and politically by Muslims, but given an ideology of inherent Muslim superiority and the segregation of minorities , were also an underclass. They were subjects who, however high they might rise in trade, commerce, or even governmental service, were never to be considered equal to the ruling Muslims. They would always remain gavur : infidels inferior to the Muslims. Active persecution of non-Muslims was relatively rare in the earlier centuries of the Ottoman Empire, but discrimination was ubiquitous and sanctioned by law and religion. The inferiority of the gavur was voluntary, Muslims believed, since unbelievers could at any time convert to Islam and thereby change their status. When Christians and Jews maintained their separate identities and communities and became visibly wealthier, effectively identified with Europeans, resentment of their enhanced status grew among Muslims. The “natural,” divinely ordained hierarchy of Muslim superiority appeared challenged by these alien elements in their midst. Unbelievers were to "stay in their place" and not appear to be equal or better than the Muslims. As imperialist Europe and nationalist movements threatened Ottoman control of the Balkans, hostilities and fears of decline ate away at the formerly cosmopolitan idea of an empire tolerant of its diverse constituent peoples.

Even in the Tanzimat period (1839-1878), when reforming rulers and bureaucrats eliminated some of the most excessive practices against their subjects and attempted to create the basis for a Rechtsstaat in the Empire, the Christians only partially benefited from the movement toward equality under the law. Armenians in eastern Anatolia repeatedly complained about armed Kurdish bands that took their livestock, land, and women. Occasionally Muslims rose in angry pogroms against Christians, and state authorities tended to excuse such behavior as an understandable response to Armenian rebellion. Beginning in the late 1870s and through the following decade, the Armenians of the provinces petitioned in greater numbers to their leaders in Istanbul and to the European consuls stationed in eastern Anatolia. Hundreds of complaints were filed; few were dealt with. Although the most brutal treatment of Armenians was at the hands of Kurdish tribesmen, the Armenians found the Ottoman state officials absent, unreliable, or simply another source of oppression. Corruption was rampant. Ordinary Muslims suffered from it as well, but the Armenians had the added burden of not belonging to the favored Muslim faithful. Massacres were reported from all parts of eastern Anatolia, particularly after the formation in the early 1890s of the officially sanctioned Kurdish military units known as the Hamidiye . Against this background of growing Kurdish aggression, Western and Russian indifference, and the collapse of the Tanzimat reform movement with the coming to power of Abdülhamid II, Sultan of the Turks (1842-1918) , a small number of Armenians, many from the Russian Empire and influenced by the radical intelligentsia of Russian Transcaucasia, turned to a revolutionary strategy. Armenian revolutionary parties - most importantly the Hunchaks and the Dashnaks - arose from a number of self-defense groups within Russia and Turkey, a tradition of resistance to state intervention characteristic of some highland Armenians, like those of Zeytun and Sasun. Armenian radicals, along with Young Turk and Macedonian revolutionaries, were seen as a serious threat to the sultan’s despotism, and in 1894-1896 massive violence led to the death of hundreds of thousands of Armenians in Anatolia.

Young Turk Revolution 1908 ↑

When Ottoman military officers joined with Young Turk intellectuals early in the 20 th century, the opposition proved able to bring down the Hamidian regime (July 1908). Ottoman Armenians and other minorities joyfully greeted the “ revolution ” that brought the Young Turks to power. They hoped that the restoration of the liberal constitution would provide a political mechanism for peaceful development within the framework of a representative parliamentary system. The leading Armenian political party, the Dashnaktsutiun , had been loosely allied with the Young Turk Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) and continued to collaborate with them up to the outbreak of the Great War. Nevertheless, the deep social hostilities between the peoples of the Empire persisted, indeed worsened, in the first two decades of the twentieth century.

Politically, most Ottoman Armenians sought a future within the Empire. Reform of the more repressive Ottoman institutions like tax farming, guarantees of equality under the law, and perhaps autonomy under a Christian governor for the Anatolian provinces, made up the program of the Armenian liberals. After 1908, the revolutionaries turned to parliamentary politics, and even the most radical agreed to work for reforms within the Ottoman constitutional regime. Both the Tanzimat reform movement and the Young Turk government that came to power in 1908 promoted a notion of legal protection of non-Muslims in a program that came to be known as Ottomanism ( osmanlılık ). The ideological umbrella of Ottomanism, however, was broad enough to include under it those who believed that the unity of the Empire could be best guaranteed by having the Ottoman Turks rule over the other nationalities. While some Ottoman reformers were prepared to go as far as the liberal Prince Mehmed Sabaheddin (1879-1948) and call for a federation of equal nations, others used the guise of Ottomanism to mask their Turkish nationalist or Pan-Turkic preferences. In the decade from 1908 to 1918 Turkish nationalism, which included virulent hostility to non-Muslims, increasingly dominated leading intellectual and political circles close to the Young Turks.

Some 2 million Christian Armenians lived in the Ottoman lands in 1915, most of them peasants and townspeople in the six provinces of eastern Anatolia. In an Anatolian population estimated to be between 15 and 17.5 million inhabitants, Armenians were outnumbered by their Muslim neighbors in most locations, though they often lived in homogeneous villages and sections of towns, and occasionally dominated larger rural and urban areas. [1] The most influential and prosperous Armenians lived in the imperial capital, Istanbul (Constantinople), where their visibility made them the target of both official and popular resentment from many Muslims. The mountainous plateau of eastern Anatolia - that Armenians considered to be historic Armenia - was an area in which the central government had only intermittent authority. An intense four-sided struggle for power, position, and survival pitted the agents of the Ottoman government, the Kurdish nomadic leaders, the semi-autonomous Turkish notables of the towns, and the Armenians against one another. Local Turkish officials ran the towns with little regard to central authority, and Kurdish beys held much of the countryside under their sway. Often the only way Istanbul could make its will felt was by sending in the army. Though Kurds had repeatedly revolted against the Ottoman state and collaborated with the invading Russians in the 19 th century, the Sublime Porte saw Armenians as a more seriously subversive element, since European powers, most importantly Russia, promoted their protection and used the “Armenian Question” as a wedge into Ottoman internal affairs. Encouraging Muslim resentment and fear of the Armenians, the state created an Armenian scapegoat that could be blamed for the defeats and failures of the Ottoman government. The social system in eastern Anatolia was sanctioned by violence, often state violence, and the claims of the Armenians for a more just relationship were neglected or rejected. Ottoman governments recognized no right of popular resistance, and acts of rebellion were seen as the result of the artificial intervention of outside agitators and disloyal Armenian subjects.

Social grievances in towns, along with the population pressure and competition for resources in agriculture, were part of a toxic mix of social and political elements that provided the environment for growing hostility toward the Armenians. Whatever resentments the poor peasant population of eastern Anatolia may have felt toward the people in towns - the places where they received low prices for their produce, where they felt their social inferiority most acutely, and where they were alien to and unwanted by the better-dressed people - were easily transferred to the Armenians. The catalyst for killing, however, was not spontaneously generated out of the tinder of social and cultural tensions. It came from the state itself: from officials and conservative clergy who had for decades perceived Armenians as alien to the Ottoman Empire, and from dangerous revolutionaries and separatists who threatened the integrity of the state. Armenians were imagined to be responsible for the troubles of the Empire, allies of the anti-Ottoman European powers, and the introduction of politically radical ideas, including trade unionism and socialism, to the Empire.

Turkish Nationalism and the Catastrophic Results of the War for Armenians ↑

As Europe drifted through the last decade before World War I, the Ottoman government experienced a series of political and military defeats: the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina by Austro-Hungary in 1908, the subsequent declaration of independence by Bulgaria , the merger of Crete with Greece , revolts in Albania in 1910-1912, losses to Italy in Libya (1911), and in the course of two Balkan Wars (1912-1913) the diminution of Ottoman territory in Europe and the forced migration of hundreds of thousands of Muslims from Europe into Anatolia. As their liberal strategies failed to unify and strengthen the Empire, the Young Turk leaders gradually shifted away from their original Ottomanist views of a multinational empire based on guarantees of civil and minority rights to a more Turkish nationalist ideology that emphasized the dominant role of Turks. In desperation a group of Young Turk officers, led by Ismail Enver Pasha (1881-1922) , seized the government in a coup d'état in 1913, and for the next five years, years fateful for all Armenians, a triumvirate of Enver, Ahmet Cemal Pasha (1872-1922) , and Mehmed Talat Pasha (1874-1921) ruled the Empire. Their regime marked the triumph of Turkish nationalism within the government itself.

This shift toward Turkish nationalism left the Armenian political leadership in an impossible position. Torn between continuing to cooperate with the Young Turks in the hope that some gains might be won for the Armenians and breaking with their undependable political allies and going over to the opposition, the Dashnaks decided to maintain their alliance with the ruling party. Other Armenian cultural and political leaders, however, most notably the Hunchak party, opposed further collaboration with the government. As the Ottomans entered the First World War, even as Armenian soldiers joined the Ottoman Army to fight against the enemies of their government, the situation grew extremely ominous for the dangerously exposed Armenians.

What was then known as “the Great War” was a catastrophe for all the peoples of the Ottoman Empire and most completely for the Armenians and Assyrians. Of the more than 20 million subjects of the sultan, perhaps as many as 5 million would perish because of the decision by the CUP to join what was for them a war not of necessity but of choice. Most of the victims were civilians. 18 percent of Anatolian Muslims would die: the casualties of battle, famine, disease, and governmental disorganization. About 90 percent of the Armenians would be gone by the end of the war - deported, massacred, forcibly converted to Islam, or exiled beyond the borders of the new Turkey. In the twelve years from 1912 to 1924, the non-Muslim population in Ottoman Asia Minor fell from roughly 20 percent to 2 percent. [2]

The Young Turks entered the war to save, even enhance, their empire, only to preside over its demise. The war laid the foundations for the Empire’s successor, the national state created by a Turkish nationalist movement, by ethnically cleansing what would now become the “heartland” of Turks and mobilizing millions of ordinary Muslims to fight for their “fatherland.” “In Turkey’s collective memory today,” a historian of the Ottoman war writes, “the Ottomans lost the First World War; the Turks won it.” [3]

The Ottoman Empire fought from 1914 to 1918 on nine different fronts, from the Dardanelles and the Balkans to Palestine and Arabia to the Caucasus and Persia. Over 3 million Ottomans, mostly Turks, were conscripted to fight the war against the Entente. An estimated 771,844 were killed: over half by disease. The mortality rate reached 25 percent. [4] Only Serbia would suffer the loss of a higher percentage of its population than the Ottomans. The war blurred the distinctions between civilians and the military. Violence would be visited upon all citizens in this total war . Civil society would suffer enormously, while the state’s power would be extended into society in unprecedented ways. The gross domestic product in Turkey in the 1920s was half the pre-war level. [5] The urban populations of the region would not recover until the 1950s. Millions of people would be moved, either conscripted or forcibly deported by their government. Every tenth person in the Ottoman Empire would become a displaced person in the years of war. [6] Hundreds of thousands would be slaughtered because of state policy, and further hundreds of thousands would be forcibly converted to Islam, losing their original identity as Christians.

The “Evolution” of Armenian Genocide ↑

What would evolve into genocide began haphazardly in policies designed both to rearrange the demographic topography of Anatolia and to prepare for the war with Russia and its European allies. For the Young Turks the war was conceived as a transformative, revolutionary opportunity, a moment to gamble in order to save their empire and make it more secure. How that might be accomplished was influenced and shaped by their own understanding of what they desired, who their friends were, and who had to be eliminated in order to realize their emerging vision. As they worked out their jerry-built design of the future empire and improvised the means to achieve it, the party leaders consolidated their hold over the state. When Enver became minister of war in January 1914, he immediately purged the army of hundreds of officers, solidifying the military’s loyalty to himself and the CUP. The Ministry of Interior under Talat took command of the Ottoman gendarmerie. To realize their ambitions in the east the Young Turks organized a new Special Organization ( Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa ) similar in aims to an already existing paramilitary and working eventually in tandem with the original organization. [7] Headed by Doctors Behaeddin Şakir (1874-1922) and Selânikli Mehmet Nazım Bey (1870-1926) , the organization was financed and supplied by the Ministry of War but in cooperation with other parts of the government and under the direct supervision of the party. Formed initially for covert action in Russian Caucasia and Persia, the new Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa recruited tribesmen - Circassians, Kurds, and others - as well as prisoners, criminals, and bandits for its ranks. Prisons were emptied on orders of the government. More than 10,000 imprisoned criminals, many of them convicted of murder, were given a new role as fighters in the squadrons of the Special Organization. By fighting for the fatherland these former “people without honor” ( namussuz ) became respectable ( namuslu ). [8] Referred to as çetes (gangs, guerrillas), these specially recruited fighters were available to the Young Turks independently from the regular army and could be used for actions against designated civilians. [9] They played a decisive and disastrous role in the destruction of the Armenians.

Having suffered territorial losses in the Balkan Wars and been forced to accept a European-imposed reform in the “Armenian provinces” in 1914, the Young Turks joined the Central Powers ( Germany and Austro-Hungary ) as they waged war against the Entente ( Great Britain , France , and Russia) in a desperate effort to restore and strengthen their empire. Armenians precariously straddled the Russian–Ottoman front, and both the Russians and the Ottomans attempted to recruit Armenians in their campaigns against their enemies. Most Ottoman Armenians supported and even fought alongside the Ottomans against the Russians, while Armenians in Russia, organized into volunteer units, joined the tsarist campaign. In late 1914 and early 1915 massacres of Christians - Armenians and Assyrians - and Muslims occurred in the Caucasus and Persia, where Russians and Ottoman forces faced each other. Anxious to fight the Russians in 1914, the Ottoman government instigated the war by attacking Russian ships in the Black Sea. Enver led a huge army against tsarist forces on the eastern front late in the year, and at first, he was dramatically victorious. Kars was cut off and Sarıkamış surrounded. But the Ottoman troops were not prepared for the harsh winter in the Armenian highlands, and early in 1915 the Russians, accompanied by Armenian volunteer units from the Caucasus, pushed the Ottoman Army back. A disastrous defeat followed in which Enver lost three-quarters of his army - more than 45,000 men. Some Armenian soldiers deserted, and a few Ottoman Armenians fled to the areas occupied by the Russians, confirming in Turkish minds the treachery that marked the Christian minorities. Enver's defeat on the Caucasian front was the prelude to the "final solution" of the Armenian Question.

Mass Deportation, Forced Marches, and Death Camps ↑

The Russians posed a real danger to the Ottomans, just as the Allied forces were attacking Gallipoli in the west. In this moment of defeat and desperation, the triumvirate in Istanbul decided to demobilize the Armenian soldiers in the Ottoman Army and to deport Armenians from eastern Anatolia. The first victims of the state were these disarmed Armenian soldiers, who were easily segregated and systematically killed. Thus, the muscle of the Armenian communities was removed. Almost immediately, the government ordered the deportation of Armenians from cities, towns, and villages in the east, ostensibly as a necessary military measure to ensure the security of the rear. Soon Armenians throughout the country were forced to gather what belongings they could carry or transport and leave their homes at short notice. The exodus of Armenians was haphazard and brutal; irregular forces, local Kurds, and Circassians, cut down hundreds of thousands of Christians, as civil and military officials oversaw and facilitated the removal of the Empire’s Armenian and Assyrian subjects. When some Armenians resisted the encroaching massacres in the city of Van in eastern Anatolia, the CUP had the leading intellectuals and politicians in Istanbul, several of them deputies to the Ottoman Parliament, arrested and sent from the city (24 April 1915). Most of them perished in the next few months. Thus was the brain of the Ottoman Armenian people removed: the intellectual and political leadership and the connective tissue that linked separate communities together. Women, children , and old men in town after town were marched through the valleys and mountains of eastern Anatolia. Missionaries, diplomats, and foreign military officers witnessed the convoys, recorded what they saw, and sent reports home about death marches and killing fields. Survivors reached the deserts of Syria where they languished in concentration camps; many starved to death, and new massacres occurred.

The canvas on which the mass deportation and massacre of Armenians and Assyrians took place was a landscape that stretched from Istanbul almost 1,000 miles to the east, beyond the eastern ends of the Ottoman Empire into Persia and the Caucasus. Mountains, valleys, rivers, and deserts were the topographies through which hundreds of thousands of uprooted people moved in convoys. Guarded by Ottoman soldiers and gendarmes, they were attacked and slaughtered by the çetes (gangs of irregular fighters) of the Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization), and by Kurds, Turks, and Circassians. Driven to exhaustion, starvation, and suicide, hundreds of thousands would perish; others would be forced to emigrate or convert to Islam to save their lives. Men died in greater numbers; many woman and children were taken into the families of the local Muslims. Tens of thousands of orphans found some refuge in the protection of foreign missionaries. It is conservatively estimated that between 600,000 and 1 million were slaughtered, or died on the marches. Other tens of thousands fled north, to the relative safety of the Russian Caucasus. Hundreds of thousands of women and children, we now know, were compelled to convert to Islam and survived in the families of Kurds, Turks, and Arabs. Those who observed the killings, as well as the Allied powers engaged in a war against the Ottomans, repeatedly claimed that they had never witnessed anything like it. The word for what happened had not yet been invented. There was no concept to mark the state-targeted killing of a designated ethnoreligious people. At the time, those who needed a word borrowed from the bible and called it “holocaust.”

What might have been rationalized as a military necessity, given the imperial ambitions and distorted perceptions of the Ottoman leaders, quickly became a massive attack on their Armenian subjects, a systematic program of murder and pillage. An act of panic and vengeance metamorphosed monstrously into an opportunity to rid Anatolia once and for all of the one people that stood in the way of the Young Turks' plans for a more purely Muslim Empire, dominated by ethnic Turks. A whole category based on religion and ethnicity, the people of a particular millet (religious community), were singled out as potentially dangerous to the state. The deportations of Armenians and Assyrians were rationalized at the time and later as a military necessity, framed by the imperial ambitions and distorted perceptions of the Ottoman leaders, though the government refused to take responsibility for the massacres, claiming that they were caused by local officials and excessive hatred of Armenians by common people.

The Politics behind the Genocide ↑

The causes of what has come to be known as the first genocide of the 20 th century were both immediate and long-term. [10] The environment in which genocide occurred - the imperial appetites of the Great Powers, the fierce competition for land and goods in eastern Anatolia, the aspirations and aims of Armenians, and the ambitions and ideas of the Young Turks - shaped the cognitive and emotional state of the perpetrators and their “affective disposition,” that allowed them, indeed, in their minds required them, to eliminate whole peoples. In the context of war and invasion, a mental and emotional universe developed that included perceived threats, the Manichaean construction of internal enemies, and a pervasive fear that triggered a deadly, pathological response to real and imagined immediate and future dangers. A government had come to believe that among its subject peoples whole “nations” presented an immediate threat to the security of the state. Defense of the Empire and of the “Turkish nation” became the rationale for mass murder. Armenians were neither passive nor submissive victims, but the power to decide their fate was largely out of their hands. A “great inequality in agency” existed between Young Turks and their armed agents and the segmented and dispersed Armenians. [11]

The purpose of the genocide was to eliminate the perceived threat of the Armenians within the Ottoman Empire by reducing their numbers and scattering them in isolated, distant places, and to replace them with Muslim refugees who had fled from the Balkans. The destruction of the Ermeni milleti was carried out in three different but related ways: dispersion, massacre, and assimilation by conversion to Islam. A perfectly rational (and rationalist) explanation, then, for the genocide appears to be adequate: a strategic goal to secure the Empire by elimination of an existential threat to the state and the Turkish (or Islamic) people. But, before the strategic goal and the “rational” choices of instruments to be used can be considered, it is necessary to explain how the existential threat was imagined; how the Armenian and Assyrian enemy was historically and culturally constructed; and what cognitive and emotional processes shaped the affective disposition of the perpetrators that compelled them to carry out massive uprooting and murder of specifically targeted peoples, and to believe that such actions were justified.

Rather than being a struggle between primordial nations (as imagined by nationalists) inevitably confronting one another and contesting sovereignty over a disputed land, the genocide was the result of an accelerating construction of different ethnoreligious communities within the complex context of an empire with its possibilities of multiple and hybrid identities and coexistence. The hierarchies, inequities, institutionalized differences, and repressions that characterized imperial life and rule, had for centuries allowed people of different religions, cultures, and languages to live together. Armenians and others acquiesced to their position in the imperial hierarchy and even developed some affection for the polity in which they lived. Shared experiences as Ottomans in some cases led to material prosperity and cultural hybridity, but always under conditions of insecurity and, often capricious, governance. The imperial paradigm met its greatest challenges from what might be lumped together under the concept of “progress”: the technological and industrial advancement of the capitalist West, which rendered the Ottoman Empire relatively “backward” in the internationally competitive marketplace, as well as the idea of equality that challenged the differentiated and unequal treatment of the various peoples of the Ottoman realm. Religion, language, and culture distinguished the millets - the Muslim, Armenian, Greek, Catholic, Protestant, Assyrian, and Jewish - one from another, yet members of all of them could aspire to be Ottoman and participate in the cultural, social, and even political life of the Empire without ever achieving full equality with the ruling institution.

From abroad, two powerful influences shaped the evolution of the various Ottoman peoples: the increasingly hegemonic discourse of the nation, which redefined the nature of political communities and legitimized culture as the basis of sovereignty and possession of a “homeland”; and the imperial ambitions of European powers, which repeatedly intervened in Ottoman politics, hiving off parts of the Empire’s territory, hollowing out the sultan’s sovereignty, and insisting on protection of his Christian subjects. Migration of some peoples out of the Empire and others into it, competition over land, particularly in eastern Anatolia, Armenian resistance to old forms of “feudal” subjugation to the Kurds - all contributed to structural and dynamic influences that generated a mental world of opposition and hostility among the millets .

Determined to save their empire, the Young Turks came to power at a moment of radical disintegration of their state that was threatened, in their minds, both by the great European powers and the non-Turkic peoples (not only by Balkan Christians, Armenians, and Greeks, but Muslim Kurds, Albanians, and Arabs as well). Clear to those Young Turks who eventually won the political contest by 1914 was that “Turks” would dominate in one way or another, and that this imperial community would not be one of civic equality. It would, in other words, be neither an ethnically homogeneous nation state like the paradigmatic states of Western Europe, nor a multinational state of diverse peoples equal under the law. It would remain an empire with some peoples dominant over others. [12] One of the most radical of the Turkish nationalists, Ziya Gökalp (1876-1924) , stated, “The people is like a garden. We are supposed to be its gardeners! First, the bad shoots are to be cut. And then the scion is to be grafted.” [13]

Genocide as Response to Crisis ↑

The Armenian genocide was not planned long in advance, but was a contingent reaction to a moment of crisis that grew more radical over time. Yet genocide became possible as a technique of state security only after a long gestation of a militant, deeply hostile anti-Armenian disposition. The genocide should be distinguished from the earlier episodes of conservative restoration of order by repression (the Hamidian massacres of 1894-1896) or urban ethnic violence (Adana, 1909). Although there were similarities with the brutal policies of massacre and deportation that earlier regimes used to keep order, the very scale of the Armenian genocide and its intended effects - to rid Anatolia and other parts of the Empire of a entire people - make it a far more radical, indeed revolutionary, transformation of the imperial setup. Neither religiously motivated nor a struggle between two contending nationalisms, one of which destroyed the other, the genocide was the product of a pathological response of desperate leaders who sought security against a people they had both construed as enemies and driven into radical opposition to the regime under which they had lived for centuries. While an anti-Armenian disposition existed and grew more virulent within the Ottoman elite long before the war, and some extremists contemplated radical solutions to the Armenian Question, particularly after the Balkan Wars, the World War not only presented an opportunity for carrying out the most revolutionary program against the Armenians, but provided the particular conjuncture that convinced the Young Turk triumvirate to deploy ethnic cleansing and genocide against the Armenians. Had there been no World War there would have been no genocide, not only because there would have been no “fog of war” to cover up the events but because the radical sense of endangerment among Turks would not have been as acute. As spring approached in 1915, and the Armenians could be linked to the Russian advance as collaborators, the governing few believed that the circumstances were propitious to remove the Armenians. Ziya Gökalp, who like so many others saw the genocide as necessary or even forced on the Ottomans, could with confidence write, “there was no Armenian massacre, there was a Turkish-Armenian arrangement. They stabbed us in the back, we stabbed them back.” [14] What was done had to be done in the name of national security, and so a kind of lawful lawlessness was permitted.

The choice of genocide was not inevitable. Predicated on long-standing and ever more extreme affective dispositions and attitudes that had demonized the Armenians as a threat that needed to be dealt with, the ultimate choice was made by specific leaders at a particular historical conjuncture when the threat seemed to them most palpable. The Young Turks’ sense of their own vulnerability - combined with resentment at what they took to be Armenians’ privileged status, Armenian dominance over Muslims in some spheres of life, and the preference of many Armenians for Christian Russia - fed a fantasy that the Armenians presented an existential threat to Turks, not only an immediate menace but a future peril as well.

The catalytic moment that triggered the most brutal response to anxiety about the future came with the World War. There was no blueprint for genocide elaborated before or even in the early months of war, but the disposition to dispose of the Armenians had already been forming in the decade before Sarajevo . The Armenian genocide was both the result of increasingly radical attitudes of Turkish national imperialists and triggered by the events of 1914-1915: the imposition of the European reform plan; the breakdown of CUP–Armenian relations when the Dashnaks refused to instigate rebellion among Caucasian Armenians; the colossal losses at Sarıkamış; and the rapid reconstruction of Armenians as an imminent internal danger. Those who perpetrated genocide operated within their own delusional rationality. [15] The Young Turks acted on fears and resentments that had been generated over time and directed their efforts to resolve their anxieties by dealing with those they perceived to threaten their survival - not with their external enemies but an internal enemy they saw allied to the Entente - the Armenians. What to denialists and their sympathizers appears to be a rational and justified strategic choice to eliminate a rebellious and seditious population, in this account is seen as the outcome of the Young Turk leaders’ pathological construction of the Armenian enemy. [16] The actions that the Young Turks decided upon were based in an emotional disposition that led to distorted interpretations of social reality and exaggerated estimations of threats. [17] The conviction that Armenians desired to form an independent state was a fantasy of the Young Turks and a few Armenian extremists. The great majority of Armenians had been willing to live within the Ottoman Empire if their lives and property could be secured. They clung to the belief that a future was possible within the Empire long after it seemed to some to be reasonable. Still, they had been socialized as Ottomans: this was their home, and what they knew. Only when their own government once again turned them into pariahs did some of them defect or resist.

The Armenian genocide, along with the killing of Assyrians and the expulsion of the Anatolian Greeks, laid the ground for the more homogeneous nation state that arose from the ashes of the Empire. Like many other states, including Australia, Israel, and the United States, the emergence of the Republic of Turkey involved the removal and subordination of native peoples who had lived on its territory prior to its founding. The connection between ethnic cleansing or genocide and the legitimacy of the national state underlies the desperate efforts to deny or distort the history of the nation and the state’s genesis.

Conclusion ↑

Estimates of the Armenians killed in the deportations and massacres of 1915-1916 range from a few hundred thousand to 1,500,000. The more conservative estimates of between 600,000 and 800,000 killed, with hundreds of thousands of others converted to Islam or surviving as refugees, appear most accurate. Whatever the actual number of those killed, the result was the physical annihilation of Armenians in the greater part of historic Armenia, the final breaking of a continuous inhabitation of that region by people who called themselves Armenian. By the act of genocide, the Young Turks prepared the ground for the Turkish national state, the republic founded by Mustafa Kemal (1881-1938) , that now occupies the Anatolian peninsula. Once the Greeks were driven into the sea at Smyrna in 1922 and Cilicia cleared of Armenians, the Turkish nationalists gained a homeland for the Turkish people. Though they would have to share eastern Anatolia with Kurds who in time acquired their own political ambitions, the successive Turkish regimes were successful in gaining international recognition of their rights to the territory that once made up the heartland of Armenian kingdoms and the eastern marchlands of the Byzantine Empire.

Ronald Grigor Suny, University of Michigan and University of Chicago

Section Editors: Michael Neiberg ; Sophie De Schaepdrijver

- ↑ Karpat, Kemal: Ottoman Population, 1830-1914: Demographic and Social Characteristics, Madison 1985, p. 190; McCarthy, Justin: Muslims and Minorities: The Population of Ottoman Anatolia and the End of the Empire, New York 1983, p. 110.

- ↑ Zürcher, Erik-Jan: Griechisch-orthodoxe und muslimische Flüchtlinge und Deportierte in Griechenland und der Türkei seit 1912, in: Bade, Klaus J. et al. (eds.): Enzykopädie Migration in Europa vom 17. Jahhundert bis zur Gegenwart, Paderborn et al. 2007, pp. 623-627.

- ↑ Aksakal, Mustafa: The Ottoman Empire, in: Winter, Jay (ed.): The Cambridge History of the First World War, Cambridge 2014, p. 464.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 468; Erik J. Zürcher estimates 325,000 directly killed in action and between 400,000 and 700,000 wounded, see The Ottoman Soldier in World War I, in his: The Young Turk Legacy and Nation Building: From the Ottoman Empire to Atatürk’s Turkey, London et al. 2010, p. 186.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 478.

- ↑ Akın, Yiğit: The Ottoman Home Front during World War I: Everyday Politics, Society, and Culture, Phd. dissertation in history, Ohio State University 2011, p. 245.

- ↑ Kévorkian, Raymond: The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History, London 2011, pp. 180-187; Kévorkian’s account of the formation of the Special Organization is based on the testimonies at the trials of the Unionists held in 1919-1920 and published originally in Takvim-ı Vekayi.

- ↑ Kévorkian, Armenian Genocide 2011, pp. 184; testimony from the First Session of the Trial of the Unionists, April 27, 1919, at 1:50: Takvim-i Vakayi, no. 3540, May 5, 1919, p. 5, col. 2, lines 8-14; Krieger: Engghati Haiaspanutyan Vaveragrakan Patmutyune, New York 1980, p. 215; Sixth Session of the Trial of the Unionists, May 14, 1919, questioning of Midhat Şükrü (pp. 91-99): Takvim-i Vakayi no. 3557, May 25, 1919, p. 92.

- ↑ A useful review of the historiographical literature on Teşkilat-ı Masusa can be found in Safı, Polat: History in the Trench: The Ottoman Special Organization – Teşkilat-ı Masusa Literature, Middle Eastern Studies, XLVIII/1 (2012), pp. 89-106. Regrettably, the article deals primarily with what cannot be said about the Special Organization rather than what it actually was. An early account still worth reading is Stoddard, Philip H.: The Ottoman Government and the Arabs, 1911-1918: A Preliminary Study on the Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa, PhD dissertation, Princeton University 1963.

- ↑ In the last few decades, scholars have designated other early 20 th -century mass killings as genocide, most notably the German attempt to exterminate the Herero and Nama peoples in Southwest Africa in 1904-1905. See, Hull, Isabel V.: Absolute Destruction: Military Culture and the Practices of War in Imperial Germany, Ithaca et al. 2005.

- ↑ In his reply to an article on 1915, by Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, historian Gerard J. Libaridian writes, “It is difficult to imagine a ‘shared history’ that does not take into consideration the great inequality of agency that existed. A shared history does indeed exist, but it is not a history of equals between the Ottoman imperial state and its Armenian subjects.” (Commentary on Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu’s article on the Armenian Issue: “Turkish Armenian Relations: Is a ‘Just Memory’ Possible?” , Turkish Policy Quarterly, Spring 2014, p. 7, http://www.turkishpolicy.com/article/989/commentary-on-fm-davutoglus-article-on-the-armenian-issue/ ).

- ↑ On the conceptual difference between empire and nation state, see Suny, Ronald Grigor: The Empire Strikes Out: Imperial Russia, ‘National’ Identity, and Theories of Empire, in: Suny, Ronald Grigor/ Martin, Terry (eds.): A State of Nations: Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin and Stalin, Oxford et al. 2001, pp. 23-66.

- ↑ Gökalp, Ziya: Kızıl elma, translation from: Kinloch, Graham Charles / Mohan, Raj P.: Genocide Approaches, Case Studies, and Responses, New York 2005, p. 50; also, cited in: Jonderden, Joost: Elite Encounters of a Violent Kind: Milli İbrahim Paşa, Ziya Gökalp and Political Struggle in Diyarbekir at the Turn of the 20th Century, in: Jonderden, Joost / Verheij Jelle (eds.), Social Relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, Leiden 2012, p. 80.

- ↑ Jonderden, Elite Encounters of a Violent Kind 2012, p. 72.

- ↑ The words “delusional rationality” come from Turkyilmaz, Yektan: Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915, PhD dissertation in Cultural Anthropology, Duke University 2011, who writes, “These ‘rationalities’ have no basis in reason, and yet become a powerful motor for killing on a mass scale” (p. 43).

- ↑ The argument from state security was made repeatedly by the Young Turk leaders and was reproduced in the first major collection of materials issued by the Ottoman government on the Armenian deportations: Dahiliye, Nezareti: Ermeni Komitelerinin Amal Ve Harekat-ı Ihtilaliyesi, Istanbul 1916.

- ↑ For interpretations of the genocide that are compatible, though not identical, with my own analysis, see, for example, the thoughtful essay by Astourian, Stepan: The Armenian Genocide: An Interpretation, The History Teacher, XXIII, 2 (February 1990), pp. 111-160; Mann, Michael: The Dark Side of Democracy, Cambridge 2004; Levene, Mark: Genocide in the Age of the Nation State, 2 vols., London 2005; Valentino, Benjamin A.: Final Solutions: Mass Killing and Genocide in the Twentieth Century, Ithaca, New York 2005; and Bloxham, Donald: The Great Game of Genocide, Oxford 2005.

- Akçam, Taner: A shameful act. The Armenian genocide and the question of Turkish responsibility , New York 2006: Metropolitan Books.

- Akçam, Taner: The Young Turks' crime against humanity. The Armenian genocide and ethnic cleansing in the Ottoman Empire , Princeton 2012: Princeton University Press.

- Balakian, Peter: The burning Tigris. The Armenian genocide and America's response , New York 2003: HarperCollins.

- Bardakjian, Kevork B.: Hitler and the Armenian genocide , Cambridge 1985: Zoryan Institute.

- Beylerian, Arthur: Les Grandes puissances, l'empire ottoman et les Arméniens dans les archives françaises (1914-1918), 3 volumes , Paris 1983: Publications de la Sorbonne.

- Bloxham, Donald: Genocide, the world wars and the unweaving of Europe , London; Portland 2008: Vallentine Mitchell.

- Bloxham, Donald: The great game of genocide. Imperialism, nationalism, and the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians , Oxford 2005: Oxford University Press.

- Bloxham, Donald / Kieser, Hans-Lukas: Genocide , in: Winter, Jay / Stille, Charles J. (eds.): The Cambridge history of the First World War. Global war, volume 1, Cambridge 2014: Cambridge University Press, pp. 585-614.

- Bryce, Viscount James: The treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915-1916 , London 1916: Sir Joseph Causton and Sons.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N.: The history of the Armenian genocide. Ethnic conflict from the Balkans to Anatolia to the Caucasus , Providence 1995: Berghahn Books.

- Davis, Leslie A., Blair, Susan (ed.): The slaughterhouse province. An American diplomat's report on the Armenian Genocide, 1915-1917 , New Rochelle 1989: Aristide D. Caratzas.

- Dündar, Fuat: Crime of numbers. The role of statistics in the Armenian question (1878-1918) , New Brunswick 2010: Transaction Publishers.

- Göçek, Fatma Müge: Denial of violence. Ottoman past, Turkish present, and collective violence against the Armenians, 1789-2009 , New York 2014: Oxford University Press.

- Gust, Wolfgang (ed.): Der Völkermord an den Armeniern 1915/16. Dokumente aus dem Politischen Archiv des deutschen Auswärtigen Amts , Springe 2005: Zu Klampen.

- Gust, Wolfgang (ed.): The Armenian genocide. Evidence from the German Foreign Office Archives, 1915-1916 , New York 2014: Berghahn Books.

- Hovannisian, Richard G.: The Armenian genocide in perspective , New Brunswick 1986: Transaction Books.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.): The Armenian genocide. History, politics, ethics , New York 1992: St. Martin's Press.

- Kévorkian, Raymond H.: The Armenian genocide. A complete history , London 2011: I. B. Tauris.

- Kieser, Hans-Lukas / Schaller, Dominik J. (eds.): Der Völkermord an den Armeniern und die Shoah / The Armenian genocide and the Shoah , Zurich 2002: Chronos.

- Kloian, Richard Diran: The Armenian genocide. News accounts from the American press, 1915-1922 , Richmond 1985: Anto Printing.

- Lepsius, Johannes: Bericht über die Lage des armenischen Volkes in der Türkei , Potsdam 1916: Tempelverlag.

- Libaridian, Gerard J. (ed.): A crime of silence. The Armenian genocide , London; Totowa 1985: Zed Books.

- Mann, Michael: The dark side of democracy. Explaining ethnic cleansing , New York 2005: Cambridge University Press.

- Melson, Robert: Revolution and genocide. On the origins of the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust , Chicago 1992: University of Chicago Press.

- Morgenthau, Henry: Ambassador Morgenthau's story , Garden City 1918: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor: 'They can live in the desert but nowhere else'. A history of the Armenian Genocide , Princeton 2015: Princeton University Press.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor / Göçek, Fatma Müge / Naimark, Norman M. (eds.): A question of genocide. Armenians and Turks at the end of the Ottoman Empire , Oxford; New York 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Ternon, Yves: The Armenians. History of a genocide , Delmar 1981: Caravan Books.

- Toynbee, Arnold J.: Armenian atrocities. The murder of a nation , London; New York 1915: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Ussher, Clarence D. / Knapp, Grace Higley: An American physician in Turkey; a narrative of adventures in peace and in war , Boston; New York 1917: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Werfel, Franz: The forty days of Musa Dagh , New York 1937: The Modern Library.

Suny, Ronald Grigor: Armenian Genocide , in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, ed. by Ute Daniel, Peter Gatrell, Oliver Janz, Heather Jones, Jennifer Keene, Alan Kramer, and Bill Nasson, issued by Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin 2015-05-26. DOI : 10.15463/ie1418.10646 .

This text is licensed under: CC by-NC-ND 3.0 Germany - Attribution, Non-commercial, No Derivative Works.

Related Articles

External links.

- Teaching & Learning Home

- Becoming an Educator

- Become a Teacher

- California Literacy

- Career Technical Education

- Business & Marketing

- Health Careers Education

- Industrial & Technology Education

- Standards & Framework

- Work Experience Education (WEE)

- Curriculum and Instruction Resources

- Common Core State Standards

- Curriculum Frameworks & Instructional Materials

- Distance Learning

- Driver Education

- Multi-Tiered System of Supports

- Recommended Literature

- School Libraries

- Service-Learning

- Specialized Media

- Grade Spans

- Early Education

- P-3 Alignment

- Middle Grades

- High School

- Postsecondary

- Adult Education

- Professional Learning

- Administrators

- Curriculum Areas

- Professional Standards

- Quality Schooling Framework

- Social and Emotional Learning

- Subject Areas

- Computer Science

- English Language Arts

- History-Social Science

- Mathematics

- Physical Education

- Visual & Performing Arts

- World Languages

- Testing & Accountability Home

- Accountability

- California School Dashboard and System of Support

- Dashboard Alternative School Status (DASS)

- Local Educational Agency Accountability Report Card

- School Accountability Report Card (SARC)

- State Accountability Report Card

- Compliance Monitoring

- District & School Interventions

- Awards and Recognition

- Academic Achievement Awards

- California Distinguished Schools Program

- California Teachers of the Year

- Classified School Employees of the Year

- California Gold Ribbon Schools

- Assessment Information

- CA Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP)

- CA Proficiency Program (CPP)

- English Language Proficiency Assessments for CA (ELPAC)

- Grade Two Diagnostic Assessment

- High School Equivalency Tests (HSET)

- National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

- Physical Fitness Testing (PFT)

- Smarter Balanced Assessment System

- Finance & Grants Home

- Definitions, Instructions, & Procedures

- Indirect Cost Rates (ICR)

- Standardized Account Code Structure (SACS)

- Allocations & Apportionments

- Categorical Programs

- Consolidated Application

- Federal Cash Management

- Local Control Funding Formula

- Principal Apportionment

- Available Funding

- Funding Results

- Projected Funding

- Search CDE Funding

- Outside Funding

- Funding Tools & Materials

- Finance & Grants Other Topics

- Fiscal Oversight

- Software & Forms

- Data & Statistics Home

- Accessing Educational Data

- About CDE's Education Data

- About DataQuest

- Data Reports by Topic

- Downloadable Data Files

- Data Collections

- California Basic Educational Data System (CBEDS)

- California Longitudinal Pupil Achievement Data System (CALPADS)

- Consolidated Application and Reporting System (CARS)

- Cradle-to-Career Data System

- Annual Financial Data

- Certificated Salaries & Benefits

- Current Expense of Education & Per-pupil Spending

- Data Strategy

- Data Privacy

- Student Health & Support

- Free and Reduced Price Meal Eligibility Data

- Food Programs

- Data Requests

- School & District Information

- California School Directory

- Charter School Locator

- County-District-School Administration

- Private School Data

- Public Schools and District Data Files

- Regional Occupational Centers & Programs

- School Performance

- Postsecondary Preparation

- Specialized Programs Home

- Directory of Schools

- Federal Grants Administration

- Charter Schools

- Contractor Information

- Laws, Regulations, & Requirements

- Program Overview

- Educational Options

- Independent Study

- Open Enrollment

- English Learners

- Special Education

- Administration & Support

- Announcements & Current Issues

- Data Collection & Reporting

- Family Involvement & Partnerships

- Quality Assurance Process

- Services & Resources