Teaching Methods and Strategies: The Complete Guide

You’ve completed your coursework. Student teaching has ended. You’ve donned the cap and gown, crossed the stage, smiled with your diploma and went home to fill out application after application.

Suddenly you are standing in what will be your classroom for the next year and after the excitement of decorating it wears off and you begin lesson planning, you start to notice all of your lessons are executed the same way, just with different material. But that is what you know and what you’ve been taught, so you go with it.

After a while, your students are bored, and so are you. There must be something wrong because this isn’t what you envisioned teaching to be like. There is.

Figuring out the best ways you can deliver information to students can sometimes be even harder than what students go through in discovering how they learn best. The reason is because every single teacher needs a variety of different teaching methods in their theoretical teaching bag to pull from depending on the lesson, the students, and things as seemingly minute as the time the class is and the subject.

Using these different teaching methods, which are rooted in theory of different teaching styles, will not only help teachers reach their full potential, but more importantly engage, motivate and reach the students in their classes, whether in person or online.

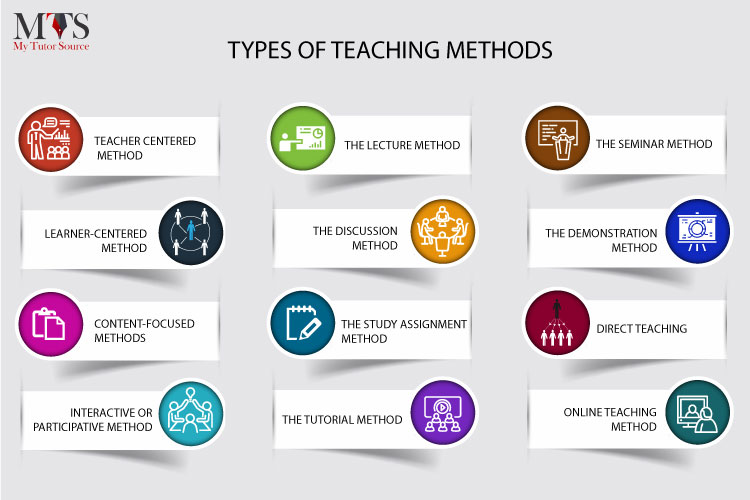

Teaching Methods

Teaching methods, or methodology, is a narrower topic because it’s founded in theories and educational psychology. If you have a degree in teaching, you most likely have heard of names like Skinner, Vygotsky , Gardner, Piaget , and Bloom . If their names don’t ring a bell, you should definitely recognize their theories that have become teaching methods. The following are the most common teaching theories.

Behaviorism

Behaviorism is the theory that every learner is essentially a “clean slate” to start off and shaped by emotions. People react to stimuli, reactions as well as positive and negative reinforcement, the site states.

Learning Theories names the most popular theorists who ascribed to this theory were Ivan Pavlov, who many people may know with his experiments with dogs. He performed an experiment with dogs that when he rang a bell, the dogs responded to the stimuli; then he applied the idea to humans.

Other popular educational theorists who were part of behaviorism was B.F. Skinner and Albert Bandura .

Social Cognitive Theory

Social Cognitive Theory is typically spoken about at the early childhood level because it has to do with critical thinking with the biggest concept being the idea of play, according to Edwin Peel writing for Encyclopedia Britannica . Though Bandura and Lev Vygotsky also contributed to cognitive theory, according to Dr. Norman Herr with California State University , the most popular and first theorist of cognitivism is Piaget.

There are four stages to Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development that he created in 1918. Each stage correlates with a child’s development from infancy to their teenage years.

The first stage is called the Sensorimotor Stage which occurs from birth to 18 months. The reason this is considered cognitive development is because the brain is literally growing through exploration, like squeaking horns, discovering themselves in mirrors or spinning things that click on their floor mats or walkers; creating habits like sleeping with a certain blanket; having reflexes like rubbing their eyes when tired or thumb sucking; and beginning to decipher vocal tones.

The second stage, or the Preoperational Stage, occurs from ages 2 to 7 when toddlers begin to understand and correlate symbols around them, ask a lot of questions, and start forming sentences and conversations, but they haven’t developed perspective yet so empathy does not quite exist yet, the website states. This is the stage when children tend to blurt out honest statements, usually embarrassing their parents, because they don’t understand censoring themselves either.

From ages 7 to 11, children are beginning to problem solve, can have conversations about things they are interested in, are more aware of logic and develop empathy during the Concrete Operational Stage.

The final stage, called the Formal Operational Stage, though by definition ends at age 16, can continue beyond. It involves deeper thinking and abstract thoughts as well as questioning not only what things are but why the way they are is popular, the site states. Many times people entering new stages of their lives like high school, college, or even marriage go through elements of Piaget’s theory, which is why the strategies that come from this method are applicable across all levels of education.

The Multiple Intelligences Theory

The Multiple Intelligences Theory states that people don’t need to be smart in every single discipline to be considered intelligent on paper tests, but that people excel in various disciplines, making them exceptional.

Created in 1983, the former principal in the Scranton School District in Scranton, PA, created eight different intelligences, though since then two others have been debated of whether to be added but have not yet officially, according to the site.

The original eight are musical, spatial, linguistic, mathematical, kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal and naturalistic and most people have a predominant intelligence followed by others. For those who are musically-inclined either via instruments, vocals, has perfect pitch, can read sheet music or can easily create music has Musical Intelligence.

Being able to see something and rearrange it or imagine it differently is Spatial Intelligence, while being talented with language, writing or avid readers have Linguistic Intelligence. Kinesthetic Intelligence refers to understanding how the body works either anatomically or athletically and Naturalistic Intelligence is having an understanding of nature and elements of the ecosystem.

The final intelligences have to do with personal interactions. Intrapersonal Intelligence is a matter of knowing oneself, one’s limits, and their inner selves while Interpersonal Intelligence is knowing how to handle a variety of other people without conflict or knowing how to resolve it, the site states. There is still an elementary school in Scranton, PA named after their once-principal.

Constructivism

Constructivism is another theory created by Piaget which is used as a foundation for many other educational theories and strategies because constructivism is focused on how people learn. Piaget states in this theory that people learn from their experiences. They learn best through active learning , connect it to their prior knowledge and then digest this information their own way. This theory has created the ideas of student-centered learning in education versus teacher-centered learning.

Universal Design for Learning

The final method is the Universal Design for Learning which has redefined the educational community since its inception in the mid-1980s by David H. Rose. This theory focuses on how teachers need to design their curriculum for their students. This theory really gained traction in the United States in 2004 when it was presented at an international conference and he explained that this theory is based on neuroscience and how the brain processes information, perform tasks and get excited about education.

The theory, known as UDL, advocates for presenting information in multiple ways to enable a variety of learners to understand the information; presenting multiple assessments for students to show what they have learned; and learn and utilize a student’s own interests to motivate them to learn, the site states. This theory also discussed incorporating technology in the classroom and ways to educate students in the digital age.

Teaching Styles

From each of the educational theories, teachers extract and develop a plethora of different teaching styles, or strategies. Instructors must have a large and varied arsenal of strategies to use weekly and even daily in order to build rapport, keep students engaged and even keep instructors from getting bored with their own material. These can be applicable to all teaching levels, but adaptations must be made based on the student’s age and level of development.

Differentiated instruction is one of the most popular teaching strategies, which means that teachers adjust the curriculum for a lesson, unit or even entire term in a way that engages all learners in various ways, according to Chapter 2 of the book Instructional Process and Concepts in Theory and Practice by Celal Akdeniz . This means changing one’s teaching styles constantly to fit not only the material but more importantly, the students based on their learning styles.

Learning styles are the ways in which students learn best. The most popular types are visual, audio, kinesthetic and read/write , though others include global as another type of learner, according to Akdeniz . For some, they may seem self-explanatory. Visual learners learn best by watching the instruction or a demonstration; audio learners need to hear a lesson; kinesthetic learners learn by doing, or are hands-on learners; read/write learners to best by reading textbooks and writing notes; and global learners need material to be applied to their real lives, according to The Library of Congress .

There are many activities available to instructors that enable their students to find out what kind of learner they are. Typically students have a main style with a close runner-up, which enables them to learn best a certain way but they can also learn material in an additional way.

When an instructor knows their students and what types of learners are in their classroom, instructors are able to then differentiate their instruction and assignments to those learning types, according to Akdeniz and The Library of Congress. Learn more about different learning styles.

When teaching new material to any type of learner, is it important to utilize a strategy called scaffolding . Scaffolding is based on a student’s prior knowledge and building a lesson, unit or course from the most foundational pieces and with each step make the information more complicated, according to an article by Jerry Webster .

To scaffold well, a teacher must take a personal interest in their students to learn not only what their prior knowledge is but their strengths as well. This will enable an instructor to base new information around their strengths and use positive reinforcement when mistakes are made with the new material.

There is an unfortunate concept in teaching called “teach to the middle” where instructors target their lessons to the average ability of the students in their classroom, leaving slower students frustrated and confused, and above average students frustrated and bored. This often results in the lower- and higher-level students scoring poorly and a teacher with no idea why.

The remedy for this is a strategy called blended learning where differentiated instruction is occurring simultaneously in the classroom to target all learners, according to author and educator Juliana Finegan . In order to be successful at blended learning, teachers once again need to know their students, how they learn and their strengths and weaknesses, according to Finegan.

Blended learning can include combining several learning styles into one lesson like lecturing from a PowerPoint – not reading the information on the slides — that includes cartoons and music associations while the students have the print-outs. The lecture can include real-life examples and stories of what the instructor encountered and what the students may encounter. That example incorporates four learning styles and misses kinesthetic, but the activity afterwards can be solely kinesthetic.

A huge component of blended learning is technology. Technology enables students to set their own pace and access the resources they want and need based on their level of understanding, according to The Library of Congress . It can be used three different ways in education which include face-to-face, synchronously or asynchronously . Technology used with the student in the classroom where the teacher can answer questions while being in the student’s physical presence is known as face-to-face.

Synchronous learning is when students are learning information online and have a teacher live with them online at the same time, but through a live chat or video conferencing program, like Skype, or Zoom, according to The Library of Congress.

Finally, asynchronous learning is when students take a course or element of a course online, like a test or assignment, as it fits into their own schedule, but a teacher is not online with them at the time they are completing or submitting the work. Teachers are still accessible through asynchronous learning but typically via email or a scheduled chat meeting, states the Library of Congress.

The final strategy to be discussed actually incorporates a few teaching strategies, so it’s almost like blended teaching. It starts with a concept that has numerous labels such as student-centered learning, learner-centered pedagogy, and teacher-as-tutor but all mean that an instructor revolves lessons around the students and ensures that students take a participatory role in the learning process, known as active learning, according to the Learning Portal .

In this model, a teacher is just a facilitator, meaning that they have created the lesson as well as the structure for learning, but the students themselves become the teachers or create their own knowledge, the Learning Portal says. As this is occurring, the instructor is circulating the room working as a one-on-one resource, tutor or guide, according to author Sara Sanchez Alonso from Yale’s Center for Teaching and Learning. For this to work well and instructors be successful one-on-one and planning these lessons, it’s essential that they have taken the time to know their students’ history and prior knowledge, otherwise it can end up to be an exercise in futility, Alonso said.

Some activities teachers can use are by putting students in groups and assigning each student a role within the group, creating reading buddies or literature circles, making games out of the material with individual white boards, create different stations within the classroom for different skill levels or interest in a lesson or find ways to get students to get up out of their seats and moving, offers Fortheteachers.org .

There are so many different methodologies and strategies that go into becoming an effective instructor. A consistent theme throughout all of these is for a teacher to take the time to know their students because they care, not because they have to. When an instructor knows the stories behind the students, they are able to design lessons that are more fun, more meaningful, and more effective because they were designed with the students’ best interests in mind.

There are plenty of pre-made lessons, activities and tests available online and from textbook publishers that any teacher could use. But you need to decide if you want to be the original teacher who makes a significant impact on your students, or a pre-made teacher a student needs to get through.

Read Also: – Blended Learning Guide – Collaborative Learning Guide – Flipped Classroom Guide – Game Based Learning Guide – Gamification in Education Guide – Holistic Education Guide – Maker Education Guide – Personalized Learning Guide – Place-Based Education Guide – Project-Based Learning Guide – Scaffolding in Education Guide – Social-Emotional Learning Guide

Similar Posts:

- Discover Your Learning Style – Comprehensive Guide on Different Learning Styles

- 35 of the BEST Educational Apps for Teachers (Updated 2024)

- 15 Learning Theories in Education (A Complete Summary)

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name and email in this browser for the next time I comment.

- MyU : For Students, Faculty, and Staff

- Academic Leaders

- Faculty and Instructors

- Graduate Students and Postdocs

Center for Educational Innovation

- Campus and Collegiate Liaisons

- Pedagogical Innovations Journal Club

- Teaching Enrichment Series

- Recorded Webinars

- Video Series

- All Services

- Teaching Consultations

- Student Feedback Facilitation

- Instructional Media Production

- Curricular and Educational Initiative Consultations

- Educational Research and Evaluation

- Thank a Teacher

- All Teaching Resources

- Aligned Course Design

- Active Learning

- Team Projects

- Active Learning Classrooms

- Leveraging the Learning Sciences

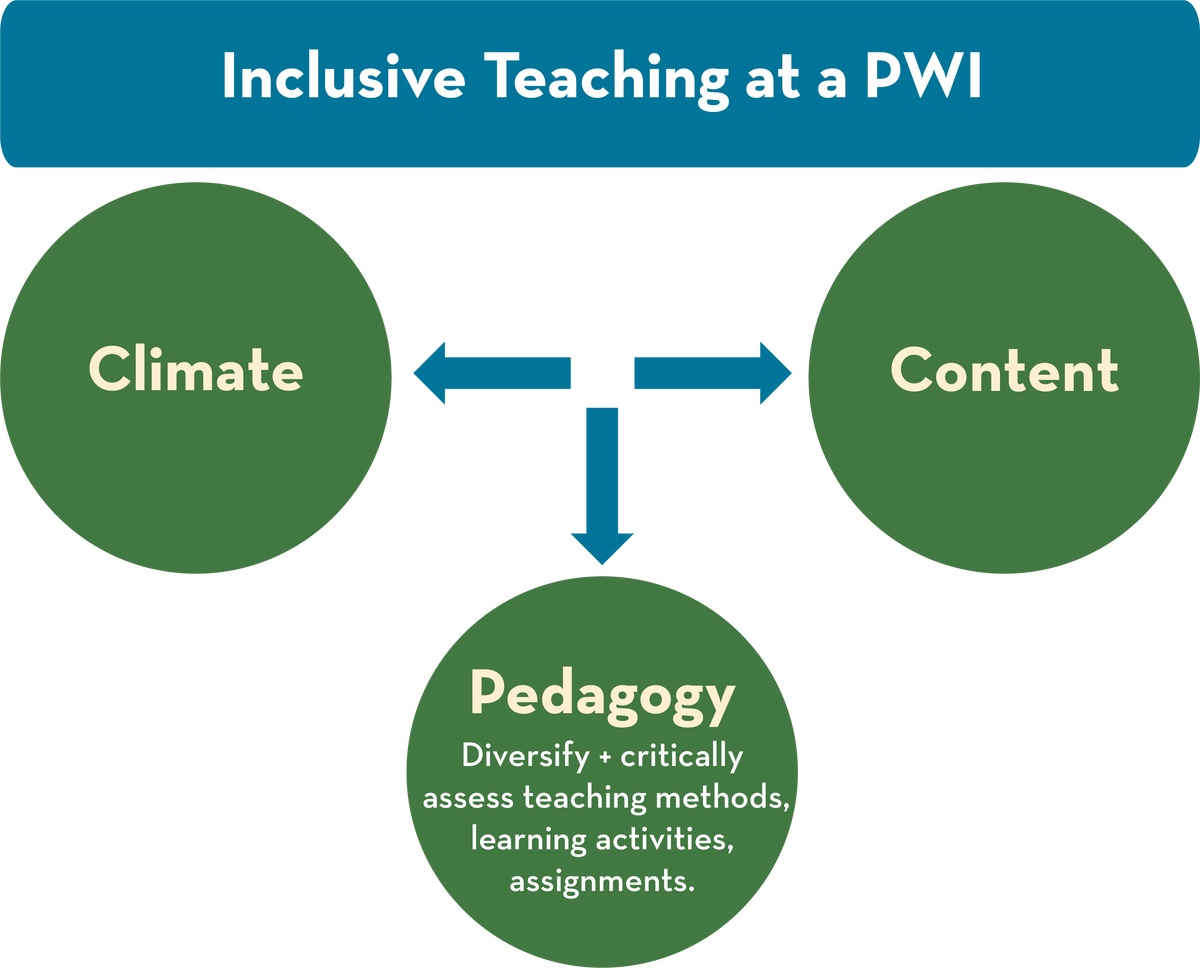

- Inclusive Teaching at a Predominantly White Institution

- Strategies to Support Challenging Conversations in the Classroom

- Assessments

- Online Teaching and Design

- AI and ChatGPT in Teaching

- Documenting Growth in Teaching

- Early Term Feedback

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Writing Your Teaching Philosophy

- All Programs

- Assessment Deep Dive

- Designing and Delivering Online Learning

- Early Career Teaching and Learning Program

- International Teaching Assistant (ITA) Program

- Preparing Future Faculty Program

- Teaching with Access and Inclusion Program

- Teaching for Student Well-Being Program

- Teaching Assistant and Postdoc Professional Development Program

Pedagogy - Diversifying Your Teaching Methods, Learning Activities, and Assignments

Definition of Pedagogy

In the most general sense, pedagogy is all the ways that instructors and students work with the course content. The fundamental learning goal for students is to be able to do “something meaningful” with the course content. Meaningful learning typically results in students working in the middle to upper levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy . We sometimes find that novice instructors conflate course content with pedagogy. This often results in “teaching as talking” where the presentation of content by the instructor is confused with the learning of content by the students. Think of your course content as clay and pedagogy as the ways you ask students to make “something meaningful” from that clay. Pedagogy is the combination of teaching methods (what instructors do), learning activities (what instructors ask their students to do), and learning assessments (the assignments, projects, or tasks that measure student learning).

Key Idea for Pedagogy

Diversify your pedagogy by varying your teaching methods, learning activities, and assignments. Critically assess your pedagogy through the lens of BIPOC students’ experiences at a PWI . We visualize these two related practices as a cycle because they are iterative and ongoing. Diversifying your pedagogy likely means shedding some typical ways of teaching in your discipline, or the teaching practices you inherited. It likely means doing more active learning and less traditional lecturing. Transforming good pedagogy into equitable pedagogy means rethinking your pedagogy in light of the PWI context and considering the ways your pedagogy may help or hinder learning for BIPOC students.

PWI Assumptions for Pedagogy

Understanding where students are on the spectrum of novice to expert learning in your discipline or course is a key challenge to implementing effective and inclusive pedagogy (National Research Council 2000). Instructors are typically so far removed from being a novice learner in their disciplines that they struggle to understand where students are on that spectrum. A key PWI assumption is that students understand how your disciplinary knowledge is organized and constructed . Students typically do not understand your discipline or the many other disciplines they are working in during their undergraduate years. Even graduate students may find it puzzling to explain the origins, methodologies, theories, logics, and assumptions of their disciplines. A second PWI assumption is that students are (or should be) academically prepared to learn your discipline . Students may be academically prepared for learning in some disciplines, but unless their high school experience was college preparatory and well supported, students (especially first-generation college students) are likely finding their way through a mysterious journey of different disciplinary conventions and modes of working and thinking (Nelson 1996).

A third PWI assumption is that instructors may confuse students’ academic underpreparation with their intelligence or capacity to learn . Academic preparation is typically a function of one’s high school experience including whether that high school was well resourced or under funded. Whether or not a student receives a quality high school education is usually a structural matter reflecting inequities in our K12 educational systems, not a reflection of an individual student’s ability to learn. A final PWI assumption is that students will learn well in the ways that the instructor learned well . Actually most instructors in higher education self-selected into disciplines that align with their interests, skills, academic preparation, and possibly family and community support. Our students have broader and different goals for seeking a college education and bring a range of skills to their coursework, which may or may not align with instructors’ expectations of how students learn. Inclusive teaching at a PWI means supporting the learning and career goals of our students.

Pedagogical Content Knowledge as a Core Concept

Kind and Chan (2019) propose that Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK) is the synthesis of Content Knowledge (expertise about a subject area) and Pedagogical Knowledge (expertise about teaching methods, assessment, classroom management, and how students learn). Content Knowledge (CK) without Pedagogical Knowledge (PK) limits instructors’ ability to teach effectively or inclusively. Novice instructors that rely on traditional lectures likely have limited Pedagogical Knowledge and may also be replicating their own inherited teaching practices. While Kind and Chan (2019) are writing from the perspective of science education, their concepts apply across disciplines. Moreover, Kind and Chan (2019) support van Driel et al.’s assertion that:

high-quality PCK is not characterized by knowing as many strategies as possible to teach a certain topic plus all the misconceptions students may have about it but by knowing when to apply a certain strategy in recognition of students’ actual learning needs and understanding why a certain teaching approach may be useful in one situation (quoted in Kind and Chan 2019, 975).

As we’ve stressed throughout this guide, the teaching context matters, and for inclusive pedagogy, special attention should be paid to the learning goals, instructor preparation, and students’ point of entry into course content. We also argue that the PWI context shapes what instructors might practice as CK, PK, and PCK. We recommend instructors become familiar with evidence-based pedagogy (or the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning , SoTL) in their fields. Moreover, we advise instructors to find and follow those instructors and scholars that specifically focus on inclusive teaching in their fields in order to develop an inclusive, flexible, and discipline-specific Pedagogical Content Knowledge.

Suggested Practices for Diversifying + Assessing Pedagogy

Although diversifying and critically assessing teaching methods, learning activities, and assignments will vary across disciplines, we offer a few key starting points. Diversifying your pedagogy is easier than critically assessing it through a PWI lens, but both steps are essential. In general, you can diversify your pedagogy by learning about active learning, peer learning, team-based learning, experiential learning, problem-based learning, and case-based learning, among others . There is extensive evidence-based pedagogical literature and practical guides readily available for these methods. And you can also find and follow scholars in your discipline that use these and other teaching methods.

Diversifying Your Pedagogy

Convert traditional lectures into interactive (or active) lectures.

For in-person or synchronous online courses, break a traditional lecture into “mini-lectures” of 10-15 minutes in length. After each mini-lecture, ask your students to process their learning using a discussion or problem prompt, a Classroom Assessment Technique (CAT), a Think-Pair-Share, or another brief learning activity. Read Lecturing from Center for Teaching , Vanderbilt University.

Structure small group discussions

Provide both a process and concrete questions or tasks to guide student learning (for example, provide a scenario with 3 focused tasks such as identify the problem, brainstorm possible solutions, and list the pros/cons for each solution). Read How to Hold a Better Class Discussion , The Chronicle of Higher Education .

Integrate active learning

Integrate active learning, especially into courses that are conceptual, theoretical, or otherwise historically challenging (for example, calculus, organic chemistry, statistics, philosophy). For gateway courses, draw upon the research of STEM and other education specialists on how active learning and peer learning improves student learning and reduces disparities. Read the Association of American Universities STEM Network Scholarship .

Include authentic learning

Include authentic learning, learning activities and assignments that mirror how students will work after graduation. What does it mean to think and work like an engineer? How do project teams work together? How does one present research in an educational social media campaign? Since most students seeking a college education will not become academic researchers or faculty, what kinds of things will they do in the “real world?” Help students practice and hone those skills as they learn the course content. Read Edutopia’s PBL: What Does It Take for a Project to Be Authentic?

Vary assignments and provide options

Graded assignments should range from low to high stakes. Low stakes assignments allow students to learn from their mistakes and receive timely feedback on their learning. Options for assignments allow students to demonstrate their learning, rather than demonstrate their skill at a particular type of assessment (such as a multiple choice exam or an academic research paper). Read our guide, Create Assessments That Promote Learning for All Students .

Critically Assess Your Pedagogy

Critically assessing your pedagogy through the PWI lens with attention to how your pedagogy may affect the learning of BIPOC students is more challenging and highly contextual. Instructors will want to review and apply the concepts and principles discussed in the earlier sections of this guide on Predominantly White Institutions (PWIs), PWI Assumptions, and Class Climate.

Reflect on patterns

Reflect on patterns of participation, progress in learning (grade distributions), and other course-related evidence. Look at your class sessions and assignments as experimental data. Who participated? What kinds of participation did you observe? Who didn’t participate? Why might that be? Are there a variety of ways for students to participate in the learning activities (individually, in groups, via discussion, via writing, synchronously/in-person, asynchronously/online)?

Respond to feedback on climate

Respond to feedback on climate from on-going check-ins and Critical Incident Questionnaires (CIQs) as discussed in the Climate Section (Ongoing Practices). Students will likely disengage from your requests for feedback if you do not respond to their feedback. Use this feedback to re-calibrate and re-think your pedagogy.

Seek feedback on student learning

Seek feedback on student learning in the form of Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs), in-class polls, asynchronous forums, exam wrappers, and other methods. Demonstrate that you care about your students’ learning by responding to this feedback as well. Here’s how students in previous semesters learned this material … I’m scheduling a problem-solving review session in the next class in response to the results of the exam …

Be diplomatic but clear when correcting mistakes and misconceptions

First-generation college students, many of whom may also identify as BIPOC, have typically achieved a great deal with few resources and significant barriers (Yosso 2005). However, they may be more likely to internalize their learning mistakes as signs that they don’t belong at the university. When correcting, be sure to normalize mistakes as part of the learning process. The correct answer is X, but I can see why you thought it was Y. Many students think it is Y because … But the correct answer is X because … Thank you for helping us understand that misconception.

Allow time for students to think and prepare for participation in a non-stressful setting

This was already suggested in the Climate Section (Race Stressors), but it is worth repeating. BIPOC students and multilingual students may need more time to prepare, not because of their intellectual abilities, but because of the effects of race stressors and other stressors increasing their cognitive load. Providing discussion or problem prompts in advance will reduce this stress and make space for learning. Additionally both student populations may experience stereotype threat, so participation in the “public” aspects of the class session may be stressful in ways that are not true for the majority white and domestic students. If you cannot provide prompts in advance, be sure to allow ample individual “think time” during a synchronous class session.

Avoid consensus models or majority rules processes

This was stated in the Climate Section (Teaching Practices to Avoid), but it’s such an entrenched PWI practice that it needs to be spotlighted and challenged. If I am a numerical “minority” and I am asked to come to consensus or agreement with a numerical “majority,” it is highly likely that my perspective will be minimized or dismissed. Or, I will have to expend a lot of energy to persuade my group of the value of my perspective, which is highly stressful. This is an unacceptable burden to put on BIPOC students and also may result in BIPOC students being placed in the position of teaching white students about a particular perspective or experience. The resulting tensions may also damage BIPOC students’ positive relationships with white students and instructors. When suitable for your content, create a learning experience that promotes seeking multiple solutions to problems, cases, or prompts. Rather than asking students to converge on one best recommendation, why not ask students to log all possible solutions (without evaluation) and then to recommend at least two solutions that include a rationale? Moreover, for course content dealing with policies, the recommended solutions could be explained in terms of their possible effects on different communities. If we value diverse perspectives, we need to structure the consideration of those perspectives into our learning activities and assignments.

We recognize the challenges of assessing your pedagogy through the PWI lens and doing your best to assess the effects on BIPOC student learning. This is a complex undertaking. But we encourage you to invite feedback from your students as well as to seek the guidance of colleagues, including advisors and other student affairs professionals, to inform your ongoing practices of teaching inclusively at a PWI. In the next section, we complete our exploration of the Inclusive Teaching at a PWI Framework by exploring the importance of auditing, diversifying, and critically assessing course content.

Pedagogy References

Kind, Vanessa and Kennedy K.H. Chan. 2019. “Resolving the Amalgam: Connecting Pedagogical Content Knowledge, Content Knowledge and Pedagogical Knowledge.” International Journal of Science Education . 41(7): 964-978.

Howard, Jay. N.D. “How to Hold a Better Class Discussion: Advice Guide.” The Chronicle of Higher Education . https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-hold-a-better-class-discussion/#2

National Research Council. 2000. “How Experts Differ from Novices.” Chap 2 in How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School: Expanded Edition . Washington D.C.: The National Academies Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/9853/how-people-learn-brain-mind-experience-and-school-expanded-edition

Nelson, Craig E. 1996. “Student Diversity Requires Different Approaches to College Teaching, Even in Math and Science.” The American Behavioral Scientist . 40 (2): 165-175.

Sathy, Viji and Kelly A. Hogan. N.D. “How to Make Your Teaching More Inclusive: Advice Guide.” The Chronicle of Higher Education . https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-make-your-teaching-more-inclusive/?cid=gen_sign_in

Yosso, Tara J. 2005. “Whose Culture Has Capital? A Critical Race Theory Discussion of Community Cultural Wealth.” Race, Ethnicity and Education . 8 (1): 69-91.

- Caroline Hilk

- Research and Resources

- Why Use Active Learning?

- Successful Active Learning Implementation

- Addressing Active Learning Challenges

- Why Use Team Projects?

- Project Description Examples

- Project Description for Students

- Team Projects and Student Development Outcomes

- Forming Teams

- Team Output

- Individual Contributions to the Team

- Individual Student Understanding

- Supporting Students

- Wrapping up the Project

- Addressing Challenges

- Course Planning

- Working memory

- Retrieval of information

- Spaced practice

- Active learning

- Metacognition

- Definitions and PWI Focus

- A Flexible Framework

- Class Climate

- Course Content

- An Ongoing Endeavor

- Learn About Your Context

- Design Your Course to Support Challenging Conversations

- Design Your Challenging Conversations Class Session

- Use Effective Facilitation Strategies

- What to Do in a Challenging Moment

- Debrief and Reflect On Your Experience, and Try, Try Again

- Supplemental Resources

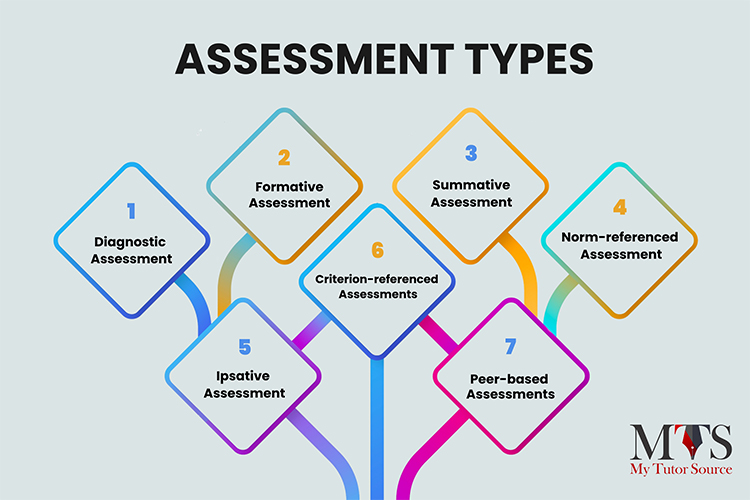

- Align Assessments

- Multiple Low Stakes Assessments

- Authentic Assessments

- Formative and Summative Assessments

- Varied Forms of Assessments

- Cumulative Assessments

- Equitable Assessments

- Essay Exams

- Multiple Choice Exams and Quizzes

- Academic Paper

- Skill Observation

- Alternative Assessments

- Assessment Plan

- Grade Assessments

- Prepare Students

- Reduce Student Anxiety

- SRT Scores: Interpreting & Responding

- Student Feedback Question Prompts

- Research Questions and Design

- Gathering data

- Publication

- GRAD 8101: Teaching in Higher Education

- Finding a Practicum Mentor

- GRAD 8200: Teaching for Learning

- Proficiency Rating & TA Eligibility

- Schedule a SETTA

- TAPD Webinars

Request More Info

Fill out the form below and a member of our team will reach out right away!

" * " indicates required fields

The Complete List of Teaching Methods

Teaching Methods: Not as Simple as ABC

Teaching methods [teacher-centered], teaching methods [student-centered], what about blended learning and udl, teaching methods: a to z, for the love of teaching.

Whether you’re a longtime educator, preparing to start your first teaching job or mapping out your dream of a career in the classroom, the topic of teaching methods is one that means many different things to different people.

Your individual approaches and strategies to imparting knowledge to your students and inspiring them to learn are probably built on your academic education as well as your instincts and intuition.

Whether you come by your preferred teaching methods organically or by actively studying educational theory and pedagogy, it can be helpful to have a comprehensive working knowledge of the various teaching methods at your disposal.

[Download] Get the Complete List of Teaching Methods PDF Now >>

The teacher-centered approach vs. the student-centered approach. High-tech vs. low-tech approaches to learning. Flipped classrooms, differentiated instruction, inquiry-based learning, personalized learning and more.

Not only are there dozens of teaching methods to explore, it is also important to have a sense for how they often overlap or interrelate. One extremely helpful look at this question is offered by the teacher-focused education website Teach.com.

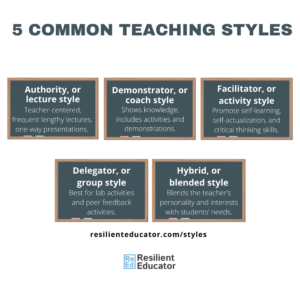

“Teaching theories can be organized into four categories based on two major parameters: a teacher-centered approach versus a student-centered approach, and high-tech material use versus low-tech material use,” according to the informative Teach.com article , which breaks down a variety of influential teaching methods as follows:

Teacher-Centered Approach to Learning Teachers serve as instructor/authority figures who deliver knowledge to their students through lectures and direct instruction, and aim to measure the results through testing and assessment. This method is sometimes referred to as “sage on the stage.”

Student-Centered Approach to Learning Teachers still serve as an authority figure, but may function more as a facilitator or “guide on the side,” as students assume a much more active role in the learning process. In this method, students learn from and are continually assessed on such activities as group projects, student portfolios and class participation.

High-Tech Approach to Learning From devices like laptops and tablets to using the internet to connect students with information and people from around the world, technology plays an ever-greater role in many of today’s classrooms. In the high-tech approach to learning, teachers utilize many different types of technology to aid students in their classroom learning.

Low-Tech Approach to Learning Technology obviously comes with pros and cons, and many teachers believe that a low-tech approach better enables them to tailor the educational experience to different types of learners. Additionally, while computer skills are undeniably necessary today, this must be balanced against potential downsides; for example, some would argue that over-reliance on spell check and autocorrect features can inhibit rather than strengthen student spelling and writing skills.

Diving further into the overlap between different types of teaching methods, here is a closer look at three teacher-centered methods of instruction and five popular student-centered approaches.

Direct Instruction (Low Tech) Under the direct instruction model — sometimes described as the “traditional” approach to teaching — teachers convey knowledge to their students primarily through lectures and scripted lesson plans, without factoring in student preferences or opportunities for hands-on or other types of learning. This method is also customarily low-tech since it relies on texts and workbooks rather than computers or mobile devices.

Flipped Classrooms (High Tech) What if students did the “classroom” portion of their learning at home and their “homework” in the classroom? That’s an oversimplified description of the flipped classroom approach, in which students watch or read their lessons on computers at home and then complete assignments and do problem-solving exercises in class.

Kinesthetic Learning (Low Tech) In the kinesthetic learning model, students perform hands-on physical activities rather than listening to lectures or watching demonstrations. Kinesthetic learning, which values movement and creativity over technological skills, is most commonly used to augment traditional types of instruction — the theory being that requiring students to do, make or create something exercises different learning muscles.

Differentiated Instruction (Low Tech) Inspired by the 1975 Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), enacted to ensure equal access to public education for all children, differentiated instruction is the practice of developing an understanding of how each student learns best, and then tailoring instruction to meet students’ individual needs.

In some instances, this means Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) for students with special needs, but today teachers use differentiated instruction to connect with all types of learners by offering options on how students access content, the types of activities they do to master a concept, how student learning is assessed and even how the classroom is set up.

Inquiry-Based Learning (High Tech) Rather than function as a sole authority figure, in inquiry-based learning teachers offer support and guidance as students work on projects that depend on them taking on a more active and participatory role in their own learning. Different students might participate in different projects, developing their own questions and then conducting research — often using online resources — and then demonstrate the results of their work through self-made videos, web pages or formal presentations.

Expeditionary Learning (Low Tech) Expeditionary learning is based on the idea that there is considerable educational value in getting students out of the classroom and into the real world. Examples include trips to City Hall or Washington, D.C., to learn about the workings of government, or out into nature to engage in specific study related to the environment. Technology can be used to augment such expeditions, but the primary focus is on getting out into the community for real-world learning experiences.

Personalized Learning (High Tech) In personalized learning, teachers encourage students to follow personalized, self-directed learning plans that are inspired by their specific interests and skills. Since assessment is also tailored to the individual, students can advance at their own pace, moving forward or spending extra time as needed. Teachers offer some traditional instruction as well as online material, while also continually reviewing student progress and meeting with students to make any needed changes to their learning plans.

Game-Based Learning (High Tech) Students love games, and considerable progress has been made in the field of game-based learning, which requires students to be problem solvers as they work on quests to accomplish a specific goal. For students, this approach blends targeted learning objectives with the fun of earning points or badges, much like they would in a video game. For teachers, planning this type of activity requires additional time and effort, so many rely on software like Classcraft or 3DGameLab to help students maximize the educational value they receive from within the gamified learning environment.

Blended Learning Blended learning is another strategy for teachers looking to introduce flexibility into their classroom. This method relies heavily on technology, with part of the instruction taking place online and part in the classroom via a more traditional approach, often leveraging elements of the flipped classroom approach detailed above. At the heart of blended learning is a philosophy of taking the time to understand each student’s learning style and develop strategies to teach to every learner, by building flexibility and choice into your curriculum.

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) UDL incorporates both student-centered learning and the “multiple intelligences theory,” which holds that different learners are wired to learn most effectively in different ways (examples of these “intelligences” include visual-spatial, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, linguistic, musical, etc.). In practice, this could mean that some students might be working on a writing project while others would be more engaged if they created a play or a movie. UDL emphasizes the idea of teaching to every student, special needs students included, in the general education classroom, creating community and building knowledge through multiple means.

In addition to the many philosophical and pedagogical approaches to teaching, classroom educators today employ diverse and sometimes highly creative methods involving specific strategies, prompts and tools that require little explanation. These include:

- Appointments with students

- Art-based projects

- Audio tutorials

- Author’s chair

- Book reports

- Bulletin boards

- Brainstorming

- Case studies

- Chalkboard instruction

- Class projects

- Classroom discussion

- Classroom video diary

- Collaborative learning spaces

- Creating murals and montages

- Current events quizzes

- Designated quiet space

- Discussion groups

- DIY activities

- Dramatization (plays, skits, etc.)

- Educational games

- Educational podcasts

- Essays (Descriptive)

- Essays (Expository)

- Essays (Narrative)

- Essays (Persuasive)

- Exhibits and displays

- Explore different cultures

- Field trips

- Flash cards

- Flexible seating

- Gamified learning plans

- Genius hour

- Group discussion

- Guest speakers

- Hands-on activities

- Individual projects

- Interviewing

- Laboratory experiments

- Learning contracts

- Learning stations

- Literature circles

- Making posters

- Mock conventions

- Motivational posters

- Music from other countries/cultures

- Oral reports

- Panel discussions

- Peer partner learning

- Photography

- Problem solving activities

- Reading aloud

- Readers’ theater

- Reflective discussion

- Research projects

- Rewards & recognition

- Role playing

- School newspapers

- Science fairs

- Sister city programs

- Spelling bees

- Storytelling

- Student podcasts

- Student portfolios

- Student presentations

- Student-conceived projects

- Supplemental reading assignments

- Team-building exercises

- Term papers

- Textbook assignments

- Think-tac-toe

- Time capsules

- Use of community or local resources

- Video creation

- Video lessons

- Vocabulary lists

So, is the teacher the center of the educational universe or the student? Does strong reliance on the wonders of technology offer a more productive educational experience or is a more traditional, lower-tech approach the best way to help students thrive?

Questions such as these are food for thought for educators everywhere, in part because they inspire ongoing reflection on how to make a meaningful difference in the lives of one’s students.

Be Sure To Share This Article

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

In our free guide, you can learn about a variety of teaching methods to adopt in the classroom.

- Master of Education

Related Posts

Teaching Methods Overview

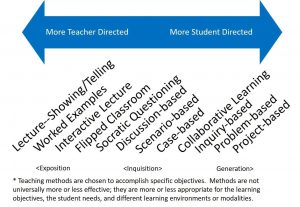

The Faculty Center promotes research-based instructional strategies and classroom techniques that improve student performance and learning. Because instruction at UCF takes place in many formats, environments, and class sizes, there is no single most effective teaching method for all contexts. However, research does support a practical range of methods that can be adapted to the various circumstances in which we teach. These strategies fall somewhere on the continuum illustrated below between teacher- and student-directed. We hope the resources on these pages will help you develop a repertoire of evidence-based instructional strategies that meet your and your students’ needs. Refer also to our Learning Spaces pages for strategies and techniques to implement active learning in various classroom configurations . Finally, a synopsis of teaching and learning principles from various sources helps frame some beneficial strategies to improve student learning.

We have provided short descriptions and links to more information for best practice for some popular teaching methods below. They are presented in order from more teacher-directed to more student-directed. For a video discussion of the above, please view the following brief video:

Lecture—Showing/Telling

Direct instruction is a widely used and effective instructional strategy that is strongly supported by research. In direct instruction, the teacher

- models an interaction with the subject, demonstrates an approach to an issue, or shows example solutions to problems,

- provides opportunities for guided practice, often assigning small group work in class with an emphasis on constructive feedback, and

- assigns independent practice with an emphasis on mastery learning.

Lecture can help students organize extensive readings, but it should not be used to simply duplicate those readings. Because learning results from what students do, lectures should be crafted so that students are intentionally active as much as is reasonable. Direct instruction can be easily combined with other teaching methods and can be transferred to online teaching by using videos for the modeling stage and discussion groups for the guided practice stage.

Worked Examples

Worked examples are step-by-step demonstrations of how to complete a problem or perform a task. Concepts are first introduced in their simplest form, then the teacher gradually progresses from simple to complex procedures. Worked examples are a way to impart information. Therefore, the process is considered a form of lecturing. Worked examples are particularly useful in STEM fields, and are most effective when learners are not already familiar with the processes being presented. Students must actually work their way through the examples, rather than skip over them to homework problems, in order to see real benefit.

This sample video from Khan Academy gives a sense of how worked examples play out in practice.

Interactive Lecture

Many instructors build their lectures around questions that students, individually or in small groups, can answer using colored flashcards or polling technologies like clickers or BYOD apps. The advantage to using polling technologies is their scalability, ease of providing collective feedback on student performance, and integration with the online gradebook for uploading participation or quiz points. Other interactive techniques involve short writing exercises, quick pairings or small group discussions, individual or collaborative problem solving, or drawing for understanding. We also have a list of suggested interactive techniques .

View the following video for some ideas about good practices for lecturing:

Flipped Classroom

In the basic structure of a “flipped classroom,” the students first engage the content online (through readings, video lectures, or podcasts), then come to class for the guided practice. It requires explicit communication of learning objectives, procedures, roles, and assessment criteria. It requires a detailed curriculum design organized around scaffolding learning toward mastery. Some critics equate direct instruction with just lecturing; however, here the term is used as “directing” student learning. In direct instruction, the role of the teacher is similar to that of a coach.

Many faculty opt to create video lectures using PowerPoint. The steps are simple: after the slides are ready, click the Slide Show tab and locate the “Record” icon near the middle. The slideshow will start, and audio will be captured for each slide. Upon completion, click File-SaveAs and switch the filetype from .pptx to .mwv or .mp4. After the video file is created, many faculty upload the video to YouTube for maximum accessibility, and link to it (or embed) from Webcourses.

For a basic introduction and resources on flipped classrooms, see https://www.edutopia.org/topic/flipped-classroom . For a more theory-based introduction, see Vanderbilt University’s discussion . Finally, please view our brief video:

Socratic Questioning

Socratic questioning involves the teacher’s facilitation of critical thinking in students by dint of carefully designed questions. The classic Greek philosopher, Socrates, believed that thoughtful questioning enabled students to examine questions logically. His technique was to profess ignorance of the topic in order to promote student knowledge. R. W. Paul has suggested six categories of Socratic questions: questions for clarification, questions that probe assumptions, questions that probe evidence and reasoning, questions about viewpoints and perspectives, questions that probe implications and consequences, and questions about the question.

See Intel.com’s article on the topic for a good overview of Socratic questioning, and view our following video:

Discussion-Based Learning

One of the primary purposes of discussion-based learning is to facilitate students’ meaningful transition into the extended conversation that is each academic discipline. Discussions allow students to practice applying their learning and developing their critical-thinking skills in real-time interactions with other viewpoints. Often, the challenge for the teacher is to get students to engage in discussions as opportunities to practice reasoning skills rather than simply exchanging opinions. One tip for addressing this challenge is to create a rubric for assessing the discussion and to assign certain students to act as evaluators who provide feedback at the end of the discussion. Students rotate into this role throughout the semester, which also benefits their development of metacognitive skills.

See the Tip Sheets at Harvard’s Bok Center for practice ideas on discussion questions and discussion leading.

The Faculty Center also offers the following brief video on discussion-based learning:

Case-Based Learning

Case-based learning is used widely across many disciplines, and collections of validated cases are available online, often bundled with handouts, readings, assessments, and tips for the teacher. Cases range from scenarios that can be addressed in a single setting, sometimes within minutes, to sequential or iterative cases that require multiple settings and multiple learning activities to arrive at multiple valid outcomes. They can be taught in a one-to-many format using polling technologies or in small teams with group reports. Ideally, all cases should be debriefed in plenary discussion to help students synthesize their learning.

For discipline-specific case studies repositories, check out the following:

- National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (Science topics) http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/

- Online based-based biology for community colleges (Biology/Ecology topics) http://bioquest.org/lifelines/cases_ecoenviro.html

- Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (History topics) http://chnm.gmu.edu/worldhistorysources/whmteaching.html

- Science Case Net (Sciences) http://sciencecasenet.org/resources/

- NASPAA Publicases repository (Public Administration, Public Policy topics) https://www.publicases.org/listing/

Collaborative Learning

Learning in groups is common practice across all levels of education. The value of learning in groups is well supported by research and is required in many disciplines. It has strong benefits for at-risk students, especially in STEM subjects. In more structured group assignments, students are often given roles that allow them to focus on specific tasks and then cycle through those roles in subsequent activities. Common classroom activities for groups include: “think-pair-share”, fishbowl debates, case studies, problem solving, jigsaw.

- Center for Teaching at Vanderbilt University website

Inquiry-Based Learning

Inquiry-based learning encompasses a range of question-driven approaches that seek to increase students’ self-direction in their development of critical-thinking and problem-solving skills. As students gain expertise, the instructor decreases guidance and direction and students take on greater responsibility for operations. Effective teaching in this mode requires accurate assessment of prior knowledge and motivation to determine the scaffolding interventions needed to compensate for the increased cognitive demands on novices. This scaffolding can be provided by the instructor through worked scenarios, process worksheets, opportunities for learner-reflection, and consultations with individuals or small groups. Students are generally allowed to practice and fail with subsequent opportunities to revise and improve performance based on feedback from peers and/or the instructor.

For a basic definition and tips about inquiry-based learning, see Teach-nology.com’s resources.

Problem-Based Learning

Often referred to as PBL, this method is similar to the case study method, except the intention is generally to keep the problem, the process, and the outcomes more ambiguous than is comfortable for students. PBL asks students to experience and struggle with radical uncertainty. Your role as the teacher is to create an intentionally ill-structured problem and a deadline for a deliverable, assign small groups (with or without defined roles), optionally offer some preparation, and resist giving clear, comfortable assessment guidance.

To learn more about problem-based learning, go here: https://citl.illinois.edu/citl-101/teaching-learning/resources/teaching-strategies/problem-based-learning-(pbl)

Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning is similar to problem-based learning, and both can be referred to as PBL, but in project-based learning, the student comes up with the problem or question to research. Often, the project’s deliverable is a creative product, which can increase student engagement and long-term learning, but it can also result in the student investing more time and resources into creative production at the expense of the academic content. When assigning projects to groups that include novice students, you should emphasize the need for equitable contributions to the assignment. Assessments should address differences in effort and allow students to contribute to the evaluations of their peers.

Learn more about project-based learning here: http://www.bu.edu/ctl/guides/project-based-learning/

An introduction to K – 12 teaching methods

Principles, pedagogy, and strategies for classroom management vary from teacher to teacher. However different, all teaching methodology is deeply rooted in traditional styles. Teachers adapt their teaching methods based on educational philosophy, classroom demographics, subject areas, and the schools at which they teach.

During various stages of childhood and development, a student’s success in the classroom is largely dependent upon his or her own motivation, interest, persistence, and ability to understand and manage his or her emotions.

Since the 1980s, experts have identified different teaching methods that speak to the key areas of school readiness and the various stages of students’ cognitive, social, and emotional development. “Approaches to learning,” “executive functioning,” “habits of mind,” “grit,” “soft skills,” and “noncognitive abilities” have been used to describe these considerations of student development in the educational setting.

As Clancy Blair and Adele Diamond state, “In sum, learning occurs through a process of engagement and participation in a relationship with a caring and trusted other who models the process of and provides opportunities for self-directed learning. In acquiring the capacity for self-regulated learning, social-emotional skills that foster the relationship and executive function skills that promote self-regulation are quite literally foundational for learning.”

CATEGORIES OF TEACHING METHODS

It is generally understood that the first step necessary in determining which teaching methods are best for you is identifying your own strengths and weaknesses.

Teacher-Centered Approach vs. Student-Centered Approach

The teacher-centered approach views the teacher as the active party in the teacher-student learning relationship, as the teacher passes information to students, who passively receive it. Students are then assessed in various ways, such as through testing and performing different kinds of tasks. The teacher is the expert and authority of the classroom and teaches directly to the students.

On the other hand, in the student-centered approach, the teacher and student are seen as equals when it comes to the responsibility of teaching and learning. The teacher facilitates the learning and understanding of the material. Measures of student learning aren’t only formal tests but also more informal assessments, such as group projects, student portfolios, and seminar-style participation. Teaching and assessment are closely tied together as a metric of success in a student-centered classroom where cooperation is delegated.

High-Tech Material Use vs. Low-Tech Material Use

The classroom has drastically evolved throughout the past several decades because of technological advances. The high-tech method to teaching takes advantage of the abundance of digital resources available to aid students in their educational progression.

Teachers encourage children to use tablets, computers, and the web to further their studies and completion of assignments. Teachers have much more access to obtain assignments from their students and to learn new ideas for their curriculum. Many teachers even use gamification software for their students to learn new critical thinking skills.

Digital education enables teachers and students to be located anywhere in the world, and it sometimes removes the element of having a physical classroom altogether. Online coursework is one of the many high-tech teaching methods.

A downside of high-tech methods, as opposed to low-tech, is the way that students get used to having technology to bolster their learning. For instance, young kids who learn to write with an automatic spell-checker aren’t as keen to spelling and ultimately may have weaker writing skills than children who learn to read and write in a low-tech classroom.

Though there are many advantages to utilizing technology in the classroom, many teachers opt to stick to traditional approaches to education. There are many studies that show a low-tech teaching classroom a student’s ability to learn.

Students also have a stronger memory if they take hand-written notes rather than typing them out on an online program.

If technology isn’t as heavily emphasized in a classroom, kinesthetic learners may have a higher likelihood to thrive, since there is more flexibility for movement and interaction during learning exercises. Teachers should not only allow but encourage students to speak and move around the room.

Expeditionary learning, also known as “learning by doing,” provides students with hands-on experience and will enable them to better apply what they learn at school to the real world, as opposed to learning a lesson online and in the virtual realm.

TEACHING TO K-3

Kindergarten through third grade is arguably the most critical time during a child’s education, and the way children of this age are taught largely shapes their understanding of the world.

Social-Emotional Learning Method

When a child is in kindergarten through third grade, the child is developing his or her cognitive and social-emotional competencies. “SEL,” or “social-emotional learning,” is a common teaching method applied among this age group. Its core elements include self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, responsible decision-making, and relationship skills. These characteristics that are actively built upon support a child’s progress in subjects such as math, literacy, technology, and social studies.

The level of a child’s SEL skills predicts the level of performance later on in his or her education. For example, a child’s early ability to self-regulate his or her emotions is tied to a higher skill level in math in the later years of the child’s academic career.

Although children have natural tendencies to be more interested in learning and attentive to developing their skills, teachers help build children’s competencies. Teachers can intentionally model enthusiasm for learning, persistence, and interest in subjects in order to evoke curiosity from their students.

They can also allow their students to make decisions that increase their participation in the classroom, which ultimately grows confidence within the children. When students are rewarded not only for their high achievements but also for their hard work, it will likely result in higher levels of work over periods of time.

Pillars of the K-3 “Approaches to Learning” Teaching Method

The “approaches to learning” teaching method derived from experts discussing cognitive and social development in young children in the 1980s. It focuses on tailored learning strategies for each age group and three pillars of specific tactics that serve as guidelines for teachers.

There are three key areas of teaching methods that K-3 grade teachers should focus on to best develop their students:

- Problem-solving

- Initiative and creativity

Methods for Teaching Engagement

engagement A kindergarten teacher, specifically, can do the following to see his or her classroom engaged and flourishing:

- Define classroom routines, responsibilities, and behaviors to set expectations

- Develop individual relationships with students to garner higher engagement

- Provide students with tools to help themselves pay attention

- Model the practice of sustaining focus and resisting distractions

- Create scenarios in which students can make their own decisions and that promote participation

- Set children up for success by doing short lessons, enabling them to focus for the entire time

As children move up through first, second, and third grade, strategies for teachers to encourage engagement and participation among their students are centered around activities that shift their focus from one thing to another, showing students lessons on how to persevere through challenges and difficulties, expanding expectations for focus, and practicing self-evaluation.

Methods for Teaching Problem-Solving

In addition to engagement, problem-solving skill development is critical during this stage of child development. Kids who understand from an early age how to work through the scenarios that life presents are better-suited to face adversity when they’re older.

Language and cognitive skills are closely linked to highly developed problem-solving skills. In the same way, mathematical and logistical thinking stems from being able to predict what is likely going to happen. Most importantly, the ability to plan and solve problems helps individuals to thrive socially. The teaching method of emphasizing problem-solving is connected to the belief that mindsets are grown.

In other words, some education professionals think that one’s mindset is “fixed” and cannot be improved upon, while others disagree and believe intelligence and abilities can be grown and developed through positive experiences in both school and the realm of work. In the growth mindset, failures or disappointments are seen as opportunities to learn and to be more readily prepared in the future. This mindset is preferred when executing the problem-solving method of teaching.

Teachers can apply teaching methods that focus on developing problem-solving skills, such as creating a routine for students to follow that also allows room for students to form their own conclusions on how to execute a task, and emphasizing individual planning in their styles of teaching.

One tactic for fostering impeccable problem-solving skills in a K-3 classroom is allowing time in each day for children to build individual and group plans. This will allow their skillsets to take root and grow in a social setting, which will translate well into logistical topics, such as mathematics. Another method is to provide alternate choices for a student to execute an assignment or task, allowing the individual to take the initiative to strategize accordingly.

Helping children through social problems they encounter at school can also allow them to learn to navigate social settings. This includes both sides of the spectrum: beneficial settings that uplift them and frustrating scenarios that reinforce growth. Posing questions in a game-like fashion can also engage students to access their logistical thoughts and allow them to explore how a scenario can result.

Teachers can observe problem-solving skills developing among their kindergarten students by encouraging students to do the following in their classrooms:

- Plan their own involvement in short- and long-term play, as well as in learning activities

- Apply familiar behaviors in new situations

- Make and follow multistep plans for completing tasks

- Apply different strategies to solve both academic and social problems with adult assistance

- Regulate their own emotional responses to frustrating situations

- Return to learning activities after becoming frustrated or angry

Among first through third-graders, teachers will observe students doing things such as developing new ways to remember information, adapting problem-solving strategies for new situations and contexts, evaluating original plans to make changes as needed, and applying results of previous plans toward future planning.

Methods for Teaching Initiative and Creativity

This area of focus within teaching is to encourage independence among individual students and to trigger creative thinking in new situations. Indicators of a child’s initiative and creativity progress are the challenging of oneself, the commitment to growing one’s learning, and becoming innovative as a learner in the classroom.

What makes the ability to take initiative so important from an early stage in education is how it separates an employee from his or co-workers when the motivation to grow comes from within. Those who have been responsible for society’s greatest leaps and bounds forward are those who have harnessed creativity and initiative, such as in the science, medicine, technology, and business sectors.

Teachers can support the development of initiative and creativity in their educational atmosphere by offering choices and letting children take initiative to circulate thought and arrive at a conclusion. Though rewarding achievement is important for students to understand that they have met expectations, it is also beneficial to reward the attempts made by children to think innovatively and outside of the box.

Children who are fueling creativity and initiative will demonstrate the following:

- Curiosity through asking concrete questions

- Attempts at new things with adult encouragement

- Participation in the classroom and taking on leadership opportunities in group settings

- Frequently bringing concepts from diverse areas of study together

- Complex language to connect ideas

Teaching to 4th-6th

Teachers feel a heavy weight on their shoulders for the curiosity and ambition of fourth- through sixth-graders, particularly as these students enter middle school. A preferred method of teaching among this age group is known as the “differentiated instruction approach.”

This approach addresses student needs and tailors teaching styles to their learning preferences while also conforming to the intense demands of today’s standards of testing and systematic metrics of success. Encompassing process, strategy, and approach, among other elements that are supported by best practice and research, are signature perspectives of the differentiation approach.

Fourth- through sixth-grade teachers favor the differentiation approach because they can use a multitude of processes to meet the learning requirements of a more diverse student body and population. The strength of this popular teaching method is that it provides a variety of ways to meet the needs of many learners.

TEACHING TACTICS OF THE DIFFERENTIATION APPROACH

As a teacher, this teaching method requires planning ahead. In order to drive students to success, you need to set your expectations for your students ahead of teaching a lesson. One easy way to do this is to follow the KUD method: “Know, Understand, Do.” Before starting to teach each lesson, you need to decide what you want your students to know, understand, and do. It is a simple framework to remember the most important aspect of teaching this age group: setting expectations.

Another important tactic is to tier your lessons. In other words, when teachers tier their assignments, they make adjustments in their lessons to meet the needs of multiple students. Tiering lesson plans can challenge students and their ability levels. The tactic here is to make sure that all tasks, regardless of the tier level, are challenging and engaging to all students in the classroom. Assessments can be altered according to the level of complexity, pacing, amount of guidance, number of steps, and level of independence required.

The steps to implementing the differentiation approach are as follows:

- Develop the basis for your tasks, including concepts, skills, and essential understandings that you want all students to obtain and reach.

- Consider how you will cluster group activities among your students. Although you can create multiple levels of tiers, keep the number of levels consistent with your groups of students. It’s best to have the same number of tiers of the exercise as you have groups. For example, if you have two groups working at grade level and one working just below, then you should have three tiers in total.

- Choose which part of your lesson plan you are going to tier. You can choose from challenge level, complexity, resources (e.g., materials and reading levels), process, or product.

- Create the tier for the students who are learning at grade level.

- Next, design a similar task for struggling learners to create a tailored environment to set them up for growth and, ultimately, success.

- Once the first two tiers have been established, develop a third tier for more advanced students who have already mastered the on-grade tier or competency being addressed. This should require a higher cognitive ability to form conclusions.

For children going through a transitional time, such as moving up through elementary school and into middle school, the differentiation approach and its tactics will guide your classroom’s success.

Teaching to 7th-9th

This next transition period for students is just as integral as the previous. Students enter into adolescence and can encounter new emotions, social situations, and intellectual challenges. They also enter a period of their life where their performance has direct repercussions, as colleges are officially watching their grades.

Statics show that ninth grade has the highest number of students who fail among all grades, creating what is known as “the ninth-grade bump.” Being held back can be detrimental to students’ confidence and perception of themselves, viewing themselves as failures. In order to thrive in ninth grade, seventh- and eighth-grade experiences must build students up to be prepared for high school.

With proactive tactics in your teaching toolkit, you can develop a purposeful plan to strengthen students’ skillsets throughout seventh, eighth, and ninth grade. Teachers can isolate both strengths and weaknesses among students in their curricula, identify high-impact instructional and support strategies to keep this age group engaged in their studies, and always be actively creating next steps for their students to achieve goals.

The most important tactic for this age group is to identify weaknesses and tailor your attention to them. This will provide students with the confidence they need to have a smooth transition as they enter adolescence and find themselves in new situations, both socially and academically.

Teaching to 10th-12th

Because this is the last stop for students before beginning their post-high school graduate careers, it is critical that teachers strategize for success in their classrooms.

As the previously mentioned teaching methods can be applied to high school, particularly the differentiation approach, individual strategies that you apply to your educational setting may reap more rewards and see your students succeed.

One of the most important tactics to apply as a teacher of 10th- through 12th-graders is to be enthusiastic about what you are teaching. If you aren’t engaged in what you’re talking about, teenagers will not be either. Their attention spans are also shortening, so having lesson plans and lectures on the lighter side will be in your favor as a high school teacher.

Class discussion, also known as the Socratic seminar method, allows students this age to thrive by being given the opportunity to express their own opinions and thoughts. It also gives them their first dose of public speaking, something they may encounter much more frequently in a university setting. Collaborative work, reading and writing assessments, and problem-solving are all great strategies to implement in your teaching in order to have an engaged classroom of teenagers.

Regardless of your preferred teaching method, the most important thing to do as a new or experienced teacher is to read your classroom and tailor your teaching style to your students and the ways they best learn. Individual students respond better to some methods than others.

What is essential to every child’s development and ability to thrive in his or her education is a positive learning experience. By paying attention to an individual child’s strengths and areas in need of improvement, teachers can ensure progress.

Request Information

ChatGPT for Teachers