An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Basic Clin Pharm

- v.5(4); September 2014-November 2014

Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation

Shazia jamshed.

Department of Pharmacy Practice, Kulliyyah of Pharmacy, International Islamic University Malaysia, Kuantan Campus, Pahang, Malaysia

Buckley and Chiang define research methodology as “a strategy or architectural design by which the researcher maps out an approach to problem-finding or problem-solving.”[ 1 ] According to Crotty, research methodology is a comprehensive strategy ‘that silhouettes our choice and use of specific methods relating them to the anticipated outcomes,[ 2 ] but the choice of research methodology is based upon the type and features of the research problem.[ 3 ] According to Johnson et al . mixed method research is “a class of research where the researcher mixes or combines quantitative and qualitative research techniques, methods, approaches, theories and or language into a single study.[ 4 ] In order to have diverse opinions and views, qualitative findings need to be supplemented with quantitative results.[ 5 ] Therefore, these research methodologies are considered to be complementary to each other rather than incompatible to each other.[ 6 ]

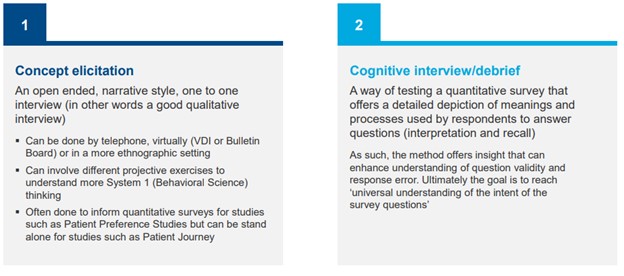

Qualitative research methodology is considered to be suitable when the researcher or the investigator either investigates new field of study or intends to ascertain and theorize prominent issues.[ 6 , 7 ] There are many qualitative methods which are developed to have an in depth and extensive understanding of the issues by means of their textual interpretation and the most common types are interviewing and observation.[ 7 ]

Interviewing

This is the most common format of data collection in qualitative research. According to Oakley, qualitative interview is a type of framework in which the practices and standards be not only recorded, but also achieved, challenged and as well as reinforced.[ 8 ] As no research interview lacks structure[ 9 ] most of the qualitative research interviews are either semi-structured, lightly structured or in-depth.[ 9 ] Unstructured interviews are generally suggested in conducting long-term field work and allow respondents to let them express in their own ways and pace, with minimal hold on respondents’ responses.[ 10 ]

Pioneers of ethnography developed the use of unstructured interviews with local key informants that is., by collecting the data through observation and record field notes as well as to involve themselves with study participants. To be precise, unstructured interview resembles a conversation more than an interview and is always thought to be a “controlled conversation,” which is skewed towards the interests of the interviewer.[ 11 ] Non-directive interviews, form of unstructured interviews are aimed to gather in-depth information and usually do not have pre-planned set of questions.[ 11 ] Another type of the unstructured interview is the focused interview in which the interviewer is well aware of the respondent and in times of deviating away from the main issue the interviewer generally refocuses the respondent towards key subject.[ 11 ] Another type of the unstructured interview is an informal, conversational interview, based on unplanned set of questions that are generated instantaneously during the interview.[ 11 ]

In contrast, semi-structured interviews are those in-depth interviews where the respondents have to answer preset open-ended questions and thus are widely employed by different healthcare professionals in their research. Semi-structured, in-depth interviews are utilized extensively as interviewing format possibly with an individual or sometimes even with a group.[ 6 ] These types of interviews are conducted once only, with an individual or with a group and generally cover the duration of 30 min to more than an hour.[ 12 ] Semi-structured interviews are based on semi-structured interview guide, which is a schematic presentation of questions or topics and need to be explored by the interviewer.[ 12 ] To achieve optimum use of interview time, interview guides serve the useful purpose of exploring many respondents more systematically and comprehensively as well as to keep the interview focused on the desired line of action.[ 12 ] The questions in the interview guide comprise of the core question and many associated questions related to the central question, which in turn, improve further through pilot testing of the interview guide.[ 7 ] In order to have the interview data captured more effectively, recording of the interviews is considered an appropriate choice but sometimes a matter of controversy among the researcher and the respondent. Hand written notes during the interview are relatively unreliable, and the researcher might miss some key points. The recording of the interview makes it easier for the researcher to focus on the interview content and the verbal prompts and thus enables the transcriptionist to generate “verbatim transcript” of the interview.

Similarly, in focus groups, invited groups of people are interviewed in a discussion setting in the presence of the session moderator and generally these discussions last for 90 min.[ 7 ] Like every research technique having its own merits and demerits, group discussions have some intrinsic worth of expressing the opinions openly by the participants. On the contrary in these types of discussion settings, limited issues can be focused, and this may lead to the generation of fewer initiatives and suggestions about research topic.

Observation

Observation is a type of qualitative research method which not only included participant's observation, but also covered ethnography and research work in the field. In the observational research design, multiple study sites are involved. Observational data can be integrated as auxiliary or confirmatory research.[ 11 ]

Research can be visualized and perceived as painstaking methodical efforts to examine, investigate as well as restructure the realities, theories and applications. Research methods reflect the approach to tackling the research problem. Depending upon the need, research method could be either an amalgam of both qualitative and quantitative or qualitative or quantitative independently. By adopting qualitative methodology, a prospective researcher is going to fine-tune the pre-conceived notions as well as extrapolate the thought process, analyzing and estimating the issues from an in-depth perspective. This could be carried out by one-to-one interviews or as issue-directed discussions. Observational methods are, sometimes, supplemental means for corroborating research findings.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7.4 Qualitative Research

Learning objectives.

- List several ways in which qualitative research differs from quantitative research in psychology.

- Describe the strengths and weaknesses of qualitative research in psychology compared with quantitative research.

- Give examples of qualitative research in psychology.

What Is Qualitative Research?

This book is primarily about quantitative research . Quantitative researchers typically start with a focused research question or hypothesis, collect a small amount of data from each of a large number of individuals, describe the resulting data using statistical techniques, and draw general conclusions about some large population. Although this is by far the most common approach to conducting empirical research in psychology, there is an important alternative called qualitative research. Qualitative research originated in the disciplines of anthropology and sociology but is now used to study many psychological topics as well. Qualitative researchers generally begin with a less focused research question, collect large amounts of relatively “unfiltered” data from a relatively small number of individuals, and describe their data using nonstatistical techniques. They are usually less concerned with drawing general conclusions about human behavior than with understanding in detail the experience of their research participants.

Consider, for example, a study by researcher Per Lindqvist and his colleagues, who wanted to learn how the families of teenage suicide victims cope with their loss (Lindqvist, Johansson, & Karlsson, 2008). They did not have a specific research question or hypothesis, such as, What percentage of family members join suicide support groups? Instead, they wanted to understand the variety of reactions that families had, with a focus on what it is like from their perspectives. To do this, they interviewed the families of 10 teenage suicide victims in their homes in rural Sweden. The interviews were relatively unstructured, beginning with a general request for the families to talk about the victim and ending with an invitation to talk about anything else that they wanted to tell the interviewer. One of the most important themes that emerged from these interviews was that even as life returned to “normal,” the families continued to struggle with the question of why their loved one committed suicide. This struggle appeared to be especially difficult for families in which the suicide was most unexpected.

The Purpose of Qualitative Research

Again, this book is primarily about quantitative research in psychology. The strength of quantitative research is its ability to provide precise answers to specific research questions and to draw general conclusions about human behavior. This is how we know that people have a strong tendency to obey authority figures, for example, or that female college students are not substantially more talkative than male college students. But while quantitative research is good at providing precise answers to specific research questions, it is not nearly as good at generating novel and interesting research questions. Likewise, while quantitative research is good at drawing general conclusions about human behavior, it is not nearly as good at providing detailed descriptions of the behavior of particular groups in particular situations. And it is not very good at all at communicating what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group in a particular situation.

But the relative weaknesses of quantitative research are the relative strengths of qualitative research. Qualitative research can help researchers to generate new and interesting research questions and hypotheses. The research of Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, suggests that there may be a general relationship between how unexpected a suicide is and how consumed the family is with trying to understand why the teen committed suicide. This relationship can now be explored using quantitative research. But it is unclear whether this question would have arisen at all without the researchers sitting down with the families and listening to what they themselves wanted to say about their experience. Qualitative research can also provide rich and detailed descriptions of human behavior in the real-world contexts in which it occurs. Among qualitative researchers, this is often referred to as “thick description” (Geertz, 1973). Similarly, qualitative research can convey a sense of what it is actually like to be a member of a particular group or in a particular situation—what qualitative researchers often refer to as the “lived experience” of the research participants. Lindqvist and colleagues, for example, describe how all the families spontaneously offered to show the interviewer the victim’s bedroom or the place where the suicide occurred—revealing the importance of these physical locations to the families. It seems unlikely that a quantitative study would have discovered this.

Data Collection and Analysis in Qualitative Research

As with correlational research, data collection approaches in qualitative research are quite varied and can involve naturalistic observation, archival data, artwork, and many other things. But one of the most common approaches, especially for psychological research, is to conduct interviews . Interviews in qualitative research tend to be unstructured—consisting of a small number of general questions or prompts that allow participants to talk about what is of interest to them. The researcher can follow up by asking more detailed questions about the topics that do come up. Such interviews can be lengthy and detailed, but they are usually conducted with a relatively small sample. This was essentially the approach used by Lindqvist and colleagues in their research on the families of suicide survivors. Small groups of people who participate together in interviews focused on a particular topic or issue are often referred to as focus groups . The interaction among participants in a focus group can sometimes bring out more information than can be learned in a one-on-one interview. The use of focus groups has become a standard technique in business and industry among those who want to understand consumer tastes and preferences. The content of all focus group interviews is usually recorded and transcribed to facilitate later analyses.

Another approach to data collection in qualitative research is participant observation. In participant observation , researchers become active participants in the group or situation they are studying. The data they collect can include interviews (usually unstructured), their own notes based on their observations and interactions, documents, photographs, and other artifacts. The basic rationale for participant observation is that there may be important information that is only accessible to, or can be interpreted only by, someone who is an active participant in the group or situation. An example of participant observation comes from a study by sociologist Amy Wilkins (published in Social Psychology Quarterly ) on a college-based religious organization that emphasized how happy its members were (Wilkins, 2008). Wilkins spent 12 months attending and participating in the group’s meetings and social events, and she interviewed several group members. In her study, Wilkins identified several ways in which the group “enforced” happiness—for example, by continually talking about happiness, discouraging the expression of negative emotions, and using happiness as a way to distinguish themselves from other groups.

Data Analysis in Quantitative Research

Although quantitative and qualitative research generally differ along several important dimensions (e.g., the specificity of the research question, the type of data collected), it is the method of data analysis that distinguishes them more clearly than anything else. To illustrate this idea, imagine a team of researchers that conducts a series of unstructured interviews with recovering alcoholics to learn about the role of their religious faith in their recovery. Although this sounds like qualitative research, imagine further that once they collect the data, they code the data in terms of how often each participant mentions God (or a “higher power”), and they then use descriptive and inferential statistics to find out whether those who mention God more often are more successful in abstaining from alcohol. Now it sounds like quantitative research. In other words, the quantitative-qualitative distinction depends more on what researchers do with the data they have collected than with why or how they collected the data.

But what does qualitative data analysis look like? Just as there are many ways to collect data in qualitative research, there are many ways to analyze data. Here we focus on one general approach called grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This approach was developed within the field of sociology in the 1960s and has gradually gained popularity in psychology. Remember that in quantitative research, it is typical for the researcher to start with a theory, derive a hypothesis from that theory, and then collect data to test that specific hypothesis. In qualitative research using grounded theory, researchers start with the data and develop a theory or an interpretation that is “grounded in” those data. They do this in stages. First, they identify ideas that are repeated throughout the data. Then they organize these ideas into a smaller number of broader themes. Finally, they write a theoretical narrative —an interpretation—of the data in terms of the themes that they have identified. This theoretical narrative focuses on the subjective experience of the participants and is usually supported by many direct quotations from the participants themselves.

As an example, consider a study by researchers Laura Abrams and Laura Curran, who used the grounded theory approach to study the experience of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers (Abrams & Curran, 2009). Their data were the result of unstructured interviews with 19 participants. Table 7.1 “Themes and Repeating Ideas in a Study of Postpartum Depression Among Low-Income Mothers” shows the five broad themes the researchers identified and the more specific repeating ideas that made up each of those themes. In their research report, they provide numerous quotations from their participants, such as this one from “Destiny:”

Well, just recently my apartment was broken into and the fact that his Medicaid for some reason was cancelled so a lot of things was happening within the last two weeks all at one time. So that in itself I don’t want to say almost drove me mad but it put me in a funk.…Like I really was depressed. (p. 357)

Their theoretical narrative focused on the participants’ experience of their symptoms not as an abstract “affective disorder” but as closely tied to the daily struggle of raising children alone under often difficult circumstances.

Table 7.1 Themes and Repeating Ideas in a Study of Postpartum Depression Among Low-Income Mothers

The Quantitative-Qualitative “Debate”

Given their differences, it may come as no surprise that quantitative and qualitative research in psychology and related fields do not coexist in complete harmony. Some quantitative researchers criticize qualitative methods on the grounds that they lack objectivity, are difficult to evaluate in terms of reliability and validity, and do not allow generalization to people or situations other than those actually studied. At the same time, some qualitative researchers criticize quantitative methods on the grounds that they overlook the richness of human behavior and experience and instead answer simple questions about easily quantifiable variables.

In general, however, qualitative researchers are well aware of the issues of objectivity, reliability, validity, and generalizability. In fact, they have developed a number of frameworks for addressing these issues (which are beyond the scope of our discussion). And in general, quantitative researchers are well aware of the issue of oversimplification. They do not believe that all human behavior and experience can be adequately described in terms of a small number of variables and the statistical relationships among them. Instead, they use simplification as a strategy for uncovering general principles of human behavior.

Many researchers from both the quantitative and qualitative camps now agree that the two approaches can and should be combined into what has come to be called mixed-methods research (Todd, Nerlich, McKeown, & Clarke, 2004). (In fact, the studies by Lindqvist and colleagues and by Abrams and Curran both combined quantitative and qualitative approaches.) One approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is to use qualitative research for hypothesis generation and quantitative research for hypothesis testing. Again, while a qualitative study might suggest that families who experience an unexpected suicide have more difficulty resolving the question of why, a well-designed quantitative study could test a hypothesis by measuring these specific variables for a large sample. A second approach to combining quantitative and qualitative research is referred to as triangulation . The idea is to use both quantitative and qualitative methods simultaneously to study the same general questions and to compare the results. If the results of the quantitative and qualitative methods converge on the same general conclusion, they reinforce and enrich each other. If the results diverge, then they suggest an interesting new question: Why do the results diverge and how can they be reconciled?

Key Takeaways

- Qualitative research is an important alternative to quantitative research in psychology. It generally involves asking broader research questions, collecting more detailed data (e.g., interviews), and using nonstatistical analyses.

- Many researchers conceptualize quantitative and qualitative research as complementary and advocate combining them. For example, qualitative research can be used to generate hypotheses and quantitative research to test them.

- Discussion: What are some ways in which a qualitative study of girls who play youth baseball would be likely to differ from a quantitative study on the same topic?

Abrams, L. S., & Curran, L. (2009). “And you’re telling me not to stress?” A grounded theory study of postpartum depression symptoms among low-income mothers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33 , 351–362.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research . Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Lindqvist, P., Johansson, L., & Karlsson, U. (2008). In the aftermath of teenage suicide: A qualitative study of the psychosocial consequences for the surviving family members. BMC Psychiatry, 8 , 26. Retrieved from http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/8/26 .

Todd, Z., Nerlich, B., McKeown, S., & Clarke, D. D. (2004) Mixing methods in psychology: The integration of qualitative and quantitative methods in theory and practice . London, UK: Psychology Press.

Wilkins, A. (2008). “Happier than Non-Christians”: Collective emotions and symbolic boundaries among evangelical Christians. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71 , 281–301.

Research Methods in Psychology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

15 Unstructured and Semistructured Interviewing

Svend Brinkmann, Department of Communication & Psychology, University of Aalborg

- Published: 02 September 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter gives an introduction to qualitative interviewing in its unstructured and semistructured forms. Initially, the human world is depicted as a conversational reality in which interviewing takes a central position as a research method. Interviewing is presented as a social practice that has a cultural history and that appears in a variety of formats in the 21st century. A number of distinctions are introduced, which are relevant when mapping the field of qualitative interviewing between different levels of structure, numbers of participants, media of interviewing, and interviewer styles. A more detailed exposition of semistructured lifeworld interviewing is offered because this is arguably the standard form of qualitative interviewing today.

Qualitative interviewing has today become a key method in the human and social sciences and in many other corners of the scientific landscape, from education to the health sciences. Some have even argued that interviewing has become the central resource through which the social sciences—and society—engages with the issues that concern it (Rapley, 2001 ). For as long as we know, human beings have used conversation as a central tool to obtain knowledge about others. People talk with others to learn about how they experience the world and how they think, act, feel, and develop as individuals and in groups; in recent decades, such knowledge-producing conversations have been refined and discussed as qualitative interviews. 1

This chapter gives an overview of the landscape of qualitative interviewing, with a focus on its unstructured and semistructured forms. But what are interviews as such? In a classic text, Maccoby and Maccoby defined the interview as “a face-to-face verbal exchange, in which one person, the interviewer, attempts to elicit information or expressions of opinion or belief from another person or persons” (Maccoby & Maccoby, 1954 , p. 449). This definition can be used as a very general starting point, but we shall soon see that different schools of qualitative interviewing have interpreted, modified, and added to such a generic characterization in many ways.

I begin this chapter by giving an introduction to the broader conversational world of human beings in which interviewing takes place. I then provide a brief history of qualitative interviewing before introducing a number of conceptual and analytical distinctions relevant for the central epistemological and theoretical questions in the field of qualitative interviewing. Particular attention is given to the complementary positions of experience-focused interviewing (phenomenological positions) and language-focused interviewing (discourse-oriented positions).

Qualitative Interviewing in a Conversational World

Human beings are conversational creatures who live a dialogical life. Humankind is, in the words of philosopher Stephen Mulhall, “a kind of enacted conversation” (Mulhall, 2007 , p. 58). From the earliest days of our lives, we are able to enter into protoconversations with caregivers in ways that involve subtle forms of turn-taking and emotional communication. The dyads in which our earliest conversations occur are known to be prior to the child’s own sense of self. We are therefore communicating, and indeed conversational, creatures before we become subjective and monological ones (Trevarthen, 1993 ).

We do learn to talk privately to ourselves and hide our emotional lives from others, but this is possible only because there was first an intersubjective communicative process with others. Our relationships with other people—and with ourselves—are thus conversational. To understand ourselves, we must use a language that was first acquired conversationally, and we try out our interpretations in dialogue with others and the world. The human self exists only within what philosopher Charles Taylor has called “webs of interlocution” (Taylor, 1989 , p. 36). Our very inquiring and interpreting selves are conversational at their core; they are constituted by the numerous relationships we have and have had with other people (Brinkmann, 2012 ).

Unsurprisingly, conversations are therefore a rich and indispensable source of knowledge about personal and social aspects of our lives. In a philosophical sense, all human research is conversational because we are linguistic creatures and language is best understood in terms of the figure of conversation (Mulhall, 2007 ). Since the late 19th century (in journalism) and the early 20th century (in the social sciences), the conversational process of knowing has been conceptualized under the name of interviewing . The term itself testifies to the dialogical and interactional nature of human life. An interview is literally an inter-view , an interchange of views between two persons (or more) conversing about a theme of mutual interest (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2015 ). Conversation in its Latin root means “dwelling with someone” or “wandering together with.” Similarly, the root meaning of dialogue is that of talk ( logos ) that goes back and forth ( dia- ) between persons (Mannheim & Tedlock, 1995 , p. 4).

Thus conceived, the concept of conversation in the human and social sciences should be thought of in very broad terms and not just as a specific research method. Certainly, conversations in the form of interviewing have been refined into a set of techniques—to be explicated later—but they are also a mode of knowing and a fundamental ontology of persons. As philosopher Rom Harré put it, “The primary human reality is persons in conversation” (Harré, 1983 , p. 58). Cultures are constantly produced, reproduced, and revised in dialogues among their members (Mannheim & Tedlock, 1995 , p. 2). Thus conceived, our everyday lives are conversational to their core. This also goes for the cultural investigation of cultural phenomena, or what we call social science. It is fruitful to see language, culture, and human self-understanding as emergent properties of conversations rather than the other way around. Dialogues are not several monologues that are added together, but the basic, primordial form of associated human life. In the words of psychologist John Shotter, “We live our daily social lives within an ambience of conversation, discussion, argumentation, negotiation, criticism and justification; much of it to do with problems of intelligibility and the legitimation of claims to truth” (Shotter, 1993 , p. 29). The pervasiveness of the figure of conversation in human life is both a burden and a blessing for qualitative interviewers. On the one hand, it means that qualitative interviewing becomes a very significant tool with which to understand central features of our conversational world. In response to widespread critiques of qualitative research that it is too subjective, one should say—given the picture of the conversational world painted here—that qualitative interviewing is, in fact, the most objective method of inquiry when one is interested in qualitative features of human experience, talk, and interaction because qualitative interviews are uniquely capable of grasping these features and thus of being adequate to their subject matters (which is one definition of objectivity) (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2015 ).

On the other hand, it is also a burden for qualitative interviewers that they employ conversations to study a world that is already saturated with conversation. If Mulhall ( 2007 ) is right that humankind is a kind of enacted conversation, then the process of studying humans by the use of interviewing is analogous to fish wanting to study water. Fish surely “know” what water is in a practical, embodied sense, but it can be a great challenge to see and understand the obvious, that with which we are so familiar (Brinkmann, 2012 ). In the same way, some interview researchers might think that interviewing others for research purposes is easy and simple to do because it employs a set of techniques that everyone masters by virtue of being capable of asking questions and recording the answers. This, however, is clearly an illusory simplicity, and many qualitative interviewers, even experienced ones, will recognize the frustrating experience of having conducted a large number of interviews (which is often the fun and seemingly simple part of a research project) but ending up with a huge amount of data, in the form of perhaps hundreds or even thousands of pages of transcripts, and not knowing how to transform all this material into a solid, relevant, and thought-provoking analysis. Too much time is often spent on interviewing, whereas too little time is devoted to preparing for the interviews and subsequently analyzing the empirical materials. To continue on this note, too little time is normally used to reflect on the role of interviewing as a knowledge-producing social practice in itself. Because of its closeness to everyday conversations, interviewing, in short, is often simply taken for granted.

A further burden for today’s qualitative interviewers concerns the fact that interviewees are often almost too familiar with their role in the conversation. As Atkinson and Silverman argued some years ago, we live in an interview society , where the self is continually produced in confessional settings ranging from talk shows to research interviews (Atkinson & Silverman, 1997 ). Because most of us, at least in the imagined hemisphere we call the West, are acquainted with interviews and their more or less standardized choreographies, qualitative interviews sometimes become a rather easy and regular affair, with few breaks and cracks in their conventions and norms, even though such breaks and cracks are often the most interesting aspects of conversational episodes (Roulston, 2010 ; Tanggaard, 2007 ).

On the side of interviewers, Atkinson and Silverman found that “in promoting a particular view of narratives of personal experience, researchers too often recapitulate, in an uncritical fashion, features of the contemporary interview society” in which “the interview becomes a personal confessional” (Atkinson & Silverman, 1997 , p. 305). Although the conversation in a broad sense is a human universal, qualitative interviewers often forget that the social practice of research interviewing in a narrower sense is a historically and culturally specific mode of interacting, and they too often construe face-to-face interaction as “the primordial, natural setting for communication,” as anthropologist Charles Briggs pointed out (Briggs, 2007 , p. 554).

As a consequence, the analysis of interviews is generally limited to what takes place during the concrete interaction phase with its questions and responses. In contrast to this, there is reason to believe that excellent interview research does not just communicate a number of answers to an interviewer’s questions (with the researcher’s interpretive interjections added on), but also includes an analytic focus on what Briggs called “the larger set of practices of knowledge production that makes up the research from beginning to end” (Briggs, 2007 , p. 566). Just as it is crucial in quantitative and experimental research to have an adequate understanding of the technologies of experimentation, it is similarly crucial in qualitative interviewing to understand the intricacies of this specific knowledge-producing practice, and interviewers should be particularly careful not to naturalize the form of human relationship that is a qualitative research interview and simply gloss it over as an unproblematic, direct, and universal source of knowledge. This, at least, is a basic assumption of the present chapter.

The History of Qualitative Interviewing

This takes us directly to the history of qualitative interviewing because only by tracking the history of how the current practices came to be can we fully understand their contingent natures and reflect on their roles in how we produce conversational knowledge through interviews today.

In one obvious sense, the use of conversations for knowledge-producing purposes is likely as old as human language and communication. The fact that we can pose questions to others about things that we are unknowledgeable about is a core capability of the human species. It expands our intellectual powers enormously because it enables us to share and distribute knowledge between us. Without this fundamental capability, it would be hard to imagine what human life would be like. It is furthermore a capacity that has developed into many different forms and ramifications in human societies. Already in 1924, Emory Bogardus, an early American sociologist and founder of one of the first U.S. sociology departments (at the University of Southern California), declared that interviewing “is as old as the human race” (Bogardus, 1924 , p. 456). Bogardus discussed similarities and differences between the ways that physicians, lawyers, priests, journalists, detectives, social workers, and psychiatrists conduct interviews, with a remarkable sensitivity to the details of such different conversational practices.

Ancient Roots

In a more specific sense, and more essentially related to qualitative interviewing as a scientific human enterprise, conversations were used by Thucydides in ancient Greece as he interviewed participants from the Peloponnesian Wars to write the history of the wars. At roughly the same time, Socrates famously questioned—or we might say interviewed —his fellow citizens in ancient Athens and used the dialogues to develop knowledge about perennial human questions related to justice, truth, beauty, and the virtues. In recent years, some interview scholars have sought to rehabilitate a Socratic practice of interviewing, not least as an alternative to the often long monologues of phenomenological and narrative approaches to interviewing (see Dinkins, 2005 , who unites Socrates with a hermeneutic approach to dialogical knowledge) and also in an attempt to think of interviews as practices that can create a knowledgeable citizenry and not merely chart common opinions and attitudes (Brinkmann, 2007a ). Such varieties of interviewing have come to be known as dialogic and confrontational (Roulston, 2010 , p. 26), and I will return to these later.

Psychoanalysis

If we jump to more recent times, interviewing notably entered the human sciences with the advent of Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis, emerging around 1900. Freud is famous for his psychoanalytic theory of the unconscious, but it is significant that he developed this revolutionary theory (which, in many ways, changed the Western conceptions of humanity) through therapeutic conversations, or what he referred to as the talking cure . Freud conducted several hundred interviews with patients using the patients’ free associations as a conversational engine. The therapist/interviewer should display what Freud called an even-hovering attention and catch on to anything that emerged as important (Freud, 1963 ).

Freud made clear that research and treatment go hand in hand in psychoanalysis, and scholars have more recently pointed to the rich potentials of psychoanalytic conversations for qualitative interviewing today (see Kvale, 2003 ). For example, Wendy Hollway and Tony Jefferson developed a more specific notion of the interview that is based on the psychoanalytic idea of “the defended subject” (Hollway & Jefferson, 2000 ). In their eyes, interviewees “are motivated not to know certain aspects of themselves and … they produce biographical accounts which avoid such knowledge” (p. 169). This has implications for how interviewers should proceed with analysis and interpretation of the biographical statements of interviewees and is a quite different approach to interviewing compared to more humanistic forms, as we shall see.

Many human and social scientists from the first half of the 20th century were well versed in psychoanalytic theory, including those who pioneered qualitative interviewing. Jean Piaget, the famous developmental researcher, even received training as a psychoanalyst himself, but his approach to interviewing is also worth mentioning in its own right. Piaget’s ( 1930 ) theory of child development was based on his interviews with children (often his own) in natural settings, frequently in combination with different experimental tasks. He would typically let the children talk freely about the weight and size of objects or, in relation to his research on moral development, about different moral problems (Piaget, 1932/1975 ), and he noticed the manner in which their thoughts unfolded.

Jumping from psychology to industrial research, Raymond Lee, one of the few historians of interviewing, charted in detail how Piaget’s so-called clinical method of interviewing became an inspiration for Elton Mayo, who was responsible for one of the largest interview studies in history at the Hawthorne plant in Chicago in the 1920s (Lee, 2011 ). This study arose from a need to interpret the curious results of a number of practical experiments on the effects of changes in illumination on production at the plant: It seemed that work output improved when the lighting of the production rooms was increased but also when it was decreased. This instigated an interview study, with more than 21,000 workers being interviewed for more than an hour each. The study was reported by Roethlisberger and Dickson ( 1939 ), but it was Mayo who laid out the methodological procedures in the 1930s, including careful—and surprisingly contemporary—advice to interviewers that is worth quoting at length:

Give your whole attention to the person interviewed, and make it evident that you are doing so.

Listen—don’t talk.

Never argue; never give advice.

what he wants to say

what he does not want to say

what he cannot say without help

As you listen, plot out tentatively and for subsequent correction the pattern (personal) that is being set before you. To test this, from time to time summarize what has been said and present for comment (e.g., “Is this what you are telling me?”). Always do this with the greatest caution, that is, clarify in ways that do not add or distort.

Remember that everything said must be considered a personal confidence and not divulged to anyone. (Mayo, 1933 , p. 65)

Many approaches to and textbooks on interviewing still follow such guidelines, often forgetting, however, the specific historical circumstances under which this practice emerged.

Nondirective Interviewing

Not just Piaget, but also the humanistic psychologist Carl Rogers influenced Mayo and others concerned with interviewing in the first half of the 20th century. Like Freud, Rogers developed a conversational technique that was useful both in therapeutic contexts (so-called client-centered therapy) and in research interviews, which he referred to as the “non-directive method as a technique for social research” (Rogers, 1945 ). As he explained, the goal of this kind of research was to sample the respondent’s attitudes toward him- or herself: “Through the non-directive interview we have an unbiased method by which we may plumb these private thoughts and perceptions of the individual” (Rogers, 1945 , p. 282). In contrast to psychoanalysis, the respondent in client-centered research (and therapy) is a client rather than a patient, and the client is the expert (and hardly a “defended subject”). Although often framed in different terms, many contemporary interview researchers conceptualize the research interview in line with Rogers’s humanistic, nondirective approach, valorizing the respondents’ private experiences, narratives, opinions, beliefs, and attitudes.

As Lee recounted, the methods of interviewing developed at Hawthorne in the 1930s aroused interest among sociologists at the University of Chicago, who made it part of their methodological repertoire (Lee, 2011 , p. 132). Rogers moved to Chicago in 1945 and was involved in different interdisciplinary projects. The so-called Chicago school of sociology was highly influential in using and promoting a range of qualitative methods, not least ethnography, and it also spawned some of the most innovative theoretical developments in the social sciences, such as symbolic interactionism (e.g., Blumer, 1969 ).

As the Rogerian nondirective approach to interviewing gained in popularity, early critiques of this technique also emerged. In the 1950s, the famous sociologist David Riesman and his colleague, Mark Benney, criticized it for its lack of interviewer involvement (the nondirective aspects), and they warned against the tendency to use the level of “rapport” (much emphasized by interviewers inspired by therapy) in an interview to judge its qualities concerning knowledge. They thought it was a prejudice “to assume the more rapport-filled and intimate the relation, the more ‘truth’ the respondent will vouchsafe” (Riesman & Benney, 1956 , p. 10). In their eyes, rapport-filled interviews would often spill over with “the flow of legend and cliché” (p. 11), since interviewees are likely to adapt their responses to what they assume the interviewer expects (see also Lee, 2008 , for an account of Riesman’s surprisingly contemporary discussion of interviewing). Issues such as these, originally raised more than 50 years ago, continue to be pertinent and largely unresolved in today’s interview research.

Classic Studies on Authoritarianism, Sexuality, and Consumerism

The mid-20th century witnessed a number of other large interview studies that remain classics in the field and have shaped public opinion about different social issues. I mention three examples here of such influential interview studies to show the variety of themes that have been studied through interviews: on authoritarianism, sexuality, and consumerism.

After World War II, there was a pressing need to understand the roots of anti-Semitism, and The Authoritarian Personality by the well-known critical theorist Adorno and coworkers controversially traced these roots to an authoritarian upbringing (Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levinson, & Sanford, 1950 ). Their study was based on interviews and employed a combination of open qualitative interviews and much more structured questionnaires to produce the data. Although important knowledge of societal value may have been produced, the study has nonetheless been criticized on ethical grounds for using therapeutic techniques to get around the defenses of the interviewees to learn about their prejudices and authoritarian personality traits (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2015 ).

Another famous interview study from the same period was Kinsey’s Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (Kinsey, Pomeroy, & Martin, 1948 ). The research group interviewed about 6,000 men for an hour or more about their sexual behaviors, generating results that were shocking to the public. In addition to the fascinating results, the book contains many interesting reflections on interviewing, and the authors discussed in great detail how to put the interviewees at ease, assure privacy, and frame the sequencing of sensitive topics (the contributions of Adorno and Kinsey are also described in Platt, 2002 ). As Kinsey put it in the book,

The interview has become an opportunity for him [the participant] to develop his own thinking, to express to himself his disappointments and hopes, to bring into the open things that he has previously been afraid to admit to himself, to work out solutions to his difficulties. He quickly comes to realize that a full and complete confession will serve his own interests. (Kinsey et al., 1948 , p. 42)

The movie Kinsey , from 2004, starring Liam Neeson, is worth seeing from an interviewer’s point of view because it shows these early interviewers in action.

As a third example, it can be mentioned that qualitative interviewing quickly entered market research in the course of the 20th century, which is hardly surprising as a consumer society developed (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2005 ). A pioneer was Ernest Dichter, whose The Strategy of Desire (1960) communicates the results of an interview study about consumer motivation for buying a car. Interestingly, Dichter described his interview technique as a “depth interview,” inspired both by psychoanalysis and by the nondirective approach of Rogers. Market and consumer research continue to be among the largest areas of qualitative interviewing in contemporary consumer society, particularly in the form of focus groups, and according to one estimate, as many as 5% of all adults in Great Britain have taken part in focus groups for marketing purposes, which lends very concrete support to the thesis that we live in an “interview society” (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2005 ).

Contemporary Conceptions of Qualitative Interviewing

Along with the different empirical studies, academics in the Western world have produced an enormous number of books on qualitative interviewing as a method, both in the form of “how to” books and in the form of more theoretical discussions. Spradley’s The Ethnographic Interview (1979) and Mishler’s Research Interviewing: Context and Narrative (1986) were two important early books, the former being full of concrete advice about how to ask questions and the latter being a thorough theoretical analysis of interviews as speech events involving a joint construction of meaning.

Also following from the postmodern philosophies of social science that emerged in the 1980s (e.g., Clifford & Marcus, 1986 ; Lyotard, 1984 ), since around 2000 there has been a veritable creative explosion in the kinds of interviews offered to researchers (see Fontana & Prokos, 2007 ), many of which question both the idea of psychoanalysis as being able to dig out truths from the psyche of the interviewee and the idea that the nondirective approach to interviews can be “an unbiased method,” as Rogers had originally conceived it.

Roulston ( 2010 ) made a comprehensive list of some of the most recent postmodern varieties of interviewing and of more traditional ones (I have here shortened and adapted Roulston’s longer list):

Neopositivist conceptions of the interview are still widespread and emphasize how the conversation can be used to reveal “the true self” of the interviewee (or the essence of his or her experiences), ideally resulting in solid, trustworthy data that are only accessible through interviews if the interviewer assumes a noninterfering role.

Romantic conceptions stress that the goal of interviewing is to obtain revelations and confessions from the interviewee facilitated by intimacy and rapport. These conceptions are somewhat close to neopositivist ones, but put much more weight on the interviewer as an active and authentic midwife who assists in “giving birth” to revelations from the interviewee’s inner psyche.

Constructionist conceptions reject the romantic idea of authenticity and favor an idea of a subject that is locally produced within the situation. Thus, the focus is on the situational practice of interviewing and a distrust toward the discourse of data as permanent “nuggets” to be “mined” by the interviewer. Instead, the interviewer is often portrayed as a “traveler” together with the interviewee, with both involved in the co-construction of whatever happens in the conversation (Brinkmann & Kvale, 2015 ).

Postmodern and transformative conceptions stage interviews as dialogic and performative events that aim to bring new kinds of people and new worlds into being (Brinkmann, 2018 ). The interview is depicted as a chance for people to get together and create new possibilities for action. Some transformative conceptions focus on potential decolonizing aspects of interviewing, seeking to subvert the colonizing tendencies that some see in standard interviewing (Smith, 1999 ). In addition, we can mention feminist (Reinharz & Chase, 2002 ) and collaborative forms of interviewing (Ellis & Berger, 2003 ) that aim to practice an engaged form of interviewing that focuses more on the researchers’ experience than on standard procedures, sometimes expressed through autoethnography, an approach that seeks to unite ethnographical and autobiographical intentions (Ellis, Adams, & Bochner, 2011 ).

It goes without saying that the overarching line of historical development laid out here, beginning in the earliest years of recorded human history and ending with postmodern, transformative, and co-constructed interviewing, is highly selective, and it could have been presented in countless other ways. I have made no attempt to divide the history of qualitative interviewing into historical phases because I believe this would betray the criss-crossing lines of inspiration from different knowledge-producing practices. Socrates as an active interviewer inspires some of today’s constructionist and postmodern interviewers (as we shall see), whereas Freud and Rogers—as clinical interviewers—in different ways became important to people who use interviewing for purposes related to marketing and the industry. Thus, it seems that the only general rule is that no approach is never completely left behind and that everything can be—and often is—recycled in new clothes. This should not surprise us, because the richness and historical variability of the human conversational world demand that researchers use different conversational means of knowledge production for different purposes.

An Example of Qualitative Interviewing

Before moving on, here I introduce an example of what a typical qualitative interview may look like, taken from my own research, to illustrate more concretely what we are talking about when we use the term qualitative interviewing.

The following excerpt is from an interview I conducted about 15 years ago. It was part of a research project in which I studied ethical dilemmas and moral reasoning in psychotherapeutic practice. The project was exploratory and sought an understanding of clinical psychologists’ own experiences of ethical problems in their work. The excerpt in Box 15.1 is meant not to represent an ideal interview, but rather to illustrate a common choreography that is inherent in much qualitative interviewing across the different varieties.

These few exchanges of questions and answers follow a certain conversational flow common in qualitative interviews. This flow can be divided into (a) question , (b) negotiation of meaning concerning the question raised and the themes addressed, (c) concrete description from the interviewee, (d) the interviewer’s interpretation of the description, and (e) coda . Then the cycle can start over with a new question, or—as in this case—further questions about the same description can be posed.

The sequence begins when I pose a question (a) that calls for a concrete description, a question that seems to make sense to the interviewee. However, she cannot immediately think of or articulate an episode, and she expresses doubt concerning the meaning of one of the central concepts of the opening question (an ethical dilemma ). This happens very often, and it can be quite difficult for interviewees (as for all of us) to describe concretely what one has experienced; we often resort to speaking in general terms (this characterizes professionals in particular, who have many general scripts at their disposal to articulate). There is some negotiation and attunement between us (b), before she decides to talk about a specific situation, but even though this is interesting and well described by the interviewee (c), she ends by returning (in what I call the coda) to a doubt about the appropriateness of the example. Before this, I summarize and rephrase her description (d), which she validates before she herself provides a kind of evaluation (e). After this, I have several follow-up questions that encourage the interviewee to tell me more about the situation before a new question is introduced, and a similar conversational cycle begins again.