- Open access

- Published: 19 May 2020

The mediating effect of social support on uncertainty in illness and quality of life of female cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study

- Insook Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6090-7999 1 &

- Changseung Park 2

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes volume 18 , Article number: 143 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

2991 Accesses

20 Citations

Metrics details

Cancer survivors have been defined as those living more than 5 years after cancer treatment with no signs of recurrence or further growth; however, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship of the United States defined cancer survivors as those undergoing treatment after being diagnosed with cancer or those considered to be fully cured. The National Cancer Institute of the United States established the Office of Cancer Survivorship, with the American Society of Clinical Oncology including “patient and survivor management” as its 2006 annual objective [ 1 ], indicating the importance of cancer survivor management as a major agenda item.

Typically, breast and thyroid cancer diagnoses occur among women in their 40s and 50s, and patients who receive treatment have high survival rates. The majority of breast and thyroid cancer survivors return to their daily lives within a relatively short timeframe [ 2 ], making quality of life after treatment and important factor in cancer treatment [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Cancer survivors have reported experiencing a variety of physical difficulties during or after treatment, including fatigue, pain, loss of energy, sleeping disorders, and constipation [ 6 , 7 ]. They also have psychological concerns, such as fear of the cancer spreading, concerns about treatment results, and uncertainty about the future [ 8 ], as well as financial difficulties, issues with their sex lives, decreased body image, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, role disorders, and difficulty returning to work [ 7 ]. Thus, cancer patients require a diverse range of healthcare services, plus emotional and socioeconomic support, with an international study of the quality of life and symptoms of cancer survivors reporting that the quality of life among Asian patients to be the lowest of those than other country [ 6 ]. Survivors of breast cancer have reported low quality of life after treatment [ 9 , 10 ], which is influenced by emotional and psychological factors such as uncertainty, body image, lack of self-respect, and depression [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], as well as social factors including social, family, and spouse support [ 10 , 11 ].

Uncertainty among women diagnosed with malignant illnesses was found to be higher than that among women with a lump in the breast [ 12 ]. Uncertainty among breast cancer patients continues for a long period because of the fear of recurrence [ 13 ] and reduced quality of life [ 11 ]. Similarly, thyroid cancer survivors also show higher levels of fatigue, depression, and anxiety compared to those with no experience of cancer [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Social support is a complex and multidimensional concept that is characterized by mutual benefits that include social, psychological, and material support provided by the social support network [ 17 ]. In other words, social support means help provided by social relationships such as family, friends, and significant others, and plays an important role in directly and indirectly reducing uncertainty [ 18 , 19 ]. For cancer survivors, the need for social support is varied and depends largely on the adaptive tasks they face [ 20 ]. Social support is closely related to breast cancer survivor prognosis [ 21 ]; breast cancer survivors’ uncertainty was found to lower their quality of life, but their recognition of social support was found to improve it [ 11 ]. Recognition of social support and uncertainty played a key role in managing and maintaining quality of life. Research has shown that social support differs according to survival stage, as patients who are undergoing treatment receive active support from healthcare professionals and their family, but this support declines notably after the treatment ends [ 14 , 22 , 23 ].

With the number of cancer survivors steadily increasing, there has been an increase in the number of studies published on cancer survivors internationally [ 22 , 24 ]. In Korea in particular, there have been studies on recurrence-prevention behaviors and quality of life [ 25 ], the factors influencing quality of life [ 10 ], fatigue and quality of life [ 26 ], distress and quality of life [ 27 ], and symptoms and quality of life among breast cancer survivors [ 8 ]. Most of these studies focused on breast cancer survivors, but few studies focus on overall quality of life and the related influential factors. Few studies have analyzed the relationships between uncertainty in illness, quality of life, and social support among female breast and thyroid cancer survivors.

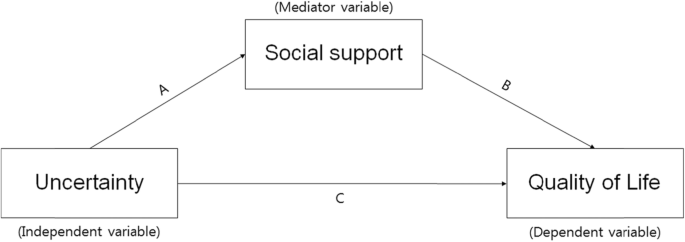

This study aimed to identify the relationships among uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life in female cancer survivors, and to verify the mediating role of social support, in the relationship between uncertainty in illness and quality of life. Social support may act as a generative mechanism influencing how uncertainty in illness, the predictor variable, affects quality of life, the outcome variable (Fig. 1 ) [ 28 ]. Therefore, this study will provide foundational data for devising practical and helpful intervention strategies to raise the quality of life of cancer survivors.

The theoretical research model showing the influence of uncertainty on quality of life and the mediating effect of social support

Participants

Participants were selected using convenience sampling of female cancer patients who were being treated by specialists in breast endocrinology at general hospitals located in J City of Korea. Among the 189 women (138 thyroid and 50 breast cancer patients) who agreed to participate, 156 surveys were collected (response rate: 82.5%). The final sample including 148 participants after excluding eight insincere responses. The data collection period was from April 21 to June 30, 2014. The completion of data collection through the mailed-in copies of surveys occurred on October 15, 2014. Participants were asked to complete the survey, put it in an opaque envelope, and seal it before returning it to the researchers. In cases in which on-site survey completion was difficult, participants were able to complete the survey at home and returned it by mail to the researcher.

The necessary sample size for the multiple regression analysis was confirmed utilizing G*power ver. 3.1.9 with a significance level (α) of .05; power of .80; effect size (f 2 ) of .15 (representing a medium effect size in the multiple regression analysis); and 13 independent variables (age, marital status, religion, level of education, occupation, satisfaction with economic status, smoking, drinking, diagnosis name, clinical stage of cancer, time passed since the end of treatment, uncertainty, and social support). The minimum sample size was determined to be 131. Since a maximum dropout rate of 40% was expected, information was collected from a total of 189 participants who fit the following inclusion criteria: 1) a diagnosis of cancer and no cognitive limitations; 2) the ability to understand and complete the survey in Korean; and 3) an understanding of the purpose of the study and consenting to participate. The exclusion criteria were those suffering from a mental illness, those with difficulties in communication, and those who did not wish to participate in the study.

Uncertainty in illness

Uncertainty occurs when an appropriate subjective interpretation of an illness or event is not formed. This study measured uncertainty using Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS), which is composed of 33 items concerning uncertainty in illness. Mishel [ 19 ] originally developed the scale, and it has been translated into Korean by Lee [ 28 ]. The MUIS is a self-administered survey, with items scored on a 5-point scale from 5 ( strongly agree ) to 1 ( strongly disagree ). Positive items were measured backward, so that total scores ranged from 33 to 165. Higher scores indicated higher rates of uncertainty. The Cronbach’s α for the original 33-item tool was .91–.93; the Cronbach’s α for the tool used in the study of Korean breast cancer patients [ 29 ] was .83. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the uncertainty scale was .88.

Social support

Social support was measured using Zimet et al.’s [ 30 ] Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). This 12-item measure is scored on a 7-point, Likert-type scale, and assessed the three dimensions of family, friends, and significant others. Its sub-domains are composed of four items. Overall social support scores are calculated by summing the scores for each item, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support. At the time of development, the Cronbach’s α reliability was .91; Cronbach’s α for each subscale ranged from .90–.95. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the social support scale was .95.

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured using a standardized tool that was translated into the Korean and verified validity of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30, which was developed through a process of international joint study from multiple countries, and it is the most widely used standardized tool to measure the quality of life of cancer patients. This tool is composed of three subdomains and 30 items. It includes two items on overall quality of life and five functional domains (i.e., physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social functions) that include 15 items; three symptom domains (i.e., fatigue, pain, nausea/vomiting) that include seven items; and one item for each of the symptoms commonly reported by cancer patients (i.e., difficulties in breathing, loss of appetite, sleeping disorders, constipation, diarrhea, and financial hardship) [ 31 ]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is converted into a score ranging between 0 and 100 points [ 31 ]; higher overall quality of life scores, higher functional domain scores, and lower symptom domain scores indicate higher quality of life. Moreover, overall quality of life can be understood as a measurement of comprehensive quality of life [ 31 ]. This study assess quality of life using the overall quality of life score. At the time of development, Cronbach’s α was .65–.73; the Cronbach’s α for the overall quality of life score in this study was .853.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted after receiving approval of the research protocol from the Institutional Review Board (Approved number: 2014-L02–01). The purpose and method of the research was explained directly to participants by a trained research assistant. The participants then signed an informed consent form that stated the survey would be used for the purposes of the study only, and that their confidentiality would be safeguarded. The subjects who agreed to participate in the survey received a small amount of goods worth of KRW 3000, but there were no factors that could interfere with the answers in the survey.

Data analysis

The collected data were coded and analyzed using SPSS software (version 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) at .05 significance level. The analysis excluded missing data values. The general characteristics, illness-related characteristics, uncertainty, social support, and quality of life were measured using frequency, percentages, means, and standard deviations. The differences in uncertainty, social support, and quality of life in accordance with general and illness-related characteristics were analyzed using independent t -tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used for independent variables of more than three groups to identify which group contained the differences. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to identify correlations between uncertainty, social support, and quality of life. Multiple regression (stepwise method) was used to test the influence of uncertainty on social support and quality of life. To verify the mediating effects of social support in the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life, simple, and hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted as per the method proposed by Baron and Kenny [ 30 ]. The significance of the mediating effects of social support was verified using the Sobel test.

Demographic characteristics of subjects

The general characteristics of the female cancer survivors in this study indicated that their average age was 51.87 ( SD = 11.78) years, with the largest proportion (33.3%) of the population being in their 50s, followed by those in their 40s (30.1%), 60s and over (24.4%), and below 30 (12.2%). Most participants (76.2%) were married; 61.9% practiced a religion, and 66.7% had a high school education or below; 56.2% had jobs; 17.8% had lost their jobs as a result of their cancer diagnosis and treatment, and 73.1% indicated that their satisfaction with their financial status was average. They had an average of 2.26 ( SD = 1.19) children; 94.4% were non-smokers; 64.1% were non-drinkers; 29.1% of the subjects had breast cancer and 70.9% had thyroid cancer; 53.8% of the cancers were early stage, and 46.2% were advanced. The duration after cancer treatment averaged 17.64 ( SD = 31.30) months, with 70.3% reporting a duration of less than a year since they ended their treatment (Table 1 ).

Uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life

Average scores of uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life are given in Table 2 . The average uncertainty in illness score was 83.06 ( SD = 15.29; range: 44–127 points), and the average quality of life score was 66.90 ( SD = 20.32; range: 0–100 points). Average social support score was 62.62 ( SD = 17.09; range: 12–84 points), with family support being the highest (mean = 21.84, SD = 6.58), followed by support from significant others (mean = 21.28, SD = 5.93) and friends (mean = 19.45, SD = 6.70).

Differences in uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life according to general and illness-related characteristics

The results of the analysis of differences in uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life according to general and illness-related characteristics are given in Tables 3 and 4 . There were significant differences in uncertainty in illness by educational level ( t = 4.048, p < .001), satisfaction with financial status ( F = 3.760, p = .027), and smoking ( t = 2.195, p = .030). Uncertainty in illness was higher for subjects with less than a high school education, compared to those who had a university degree or higher, when they were dissatisfied with their financial status. Likewise, it was higher for smokers, compared to non-smokers.

Social support had statistically significant differences given satisfaction with financial status ( F = 5.151, p = .007) and duration since cancer treatment completion ( F = 4.292, p = .015). Social support was higher for subjects with average financial status satisfaction, and for subjects for whom it had been less than a year, or between 1 to 5 years, since they completed cancer treatment.

Quality of life significantly differed according to financial status satisfaction ( F = 6.648, p = .002). Participants had higher quality of life when they had high or average financial status satisfaction compared to dissatisfaction.

Correlation between uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life

The results of the correlation analyses indicated that uncertainty in illness had a significant negative correlation with social support ( r = −.335, p < .001) and quality of life ( r = −.312, p < .001); social support had a significant positive correlation with quality of life ( r = .321, p < .001). Correlations between the sub-factors of social support and quality of life indicate that there were significant positive correlations between quality of life and support from significant others ( r = .315, p < .001), friends ( r = .284, p = .001), and family ( r = .265, p = .001). Uncertainty and support from significant others ( r = −.326, p = .001), friends ( r = −.294, p = .002), and family ( r = −.244, p = .010) showed significant negative correlations; particularly, the highest correlation was between support from significant others and uncertainty (Table 5 ).

Mediating effect of social support

Four stages of regression analysis were conducted to verify whether social support had mediating effects in the process by which uncertainty in illness influenced quality of life. Prior to verifying the mediating effects of social support, this study examined the multicollinearity between variables. The residual limit was between 0.8–1.0, which is higher than 0.1; and the value of the variance inflation factor was between 1.0–1.2, which was lower than 10, indicating no issues with multicollinearity. Moreover, the Durbin-Watson test, which is the test of independence of residual error, indicated d = 1.903–1.944, which was close to two and met the independence condition, representing no issues with self-correlation.

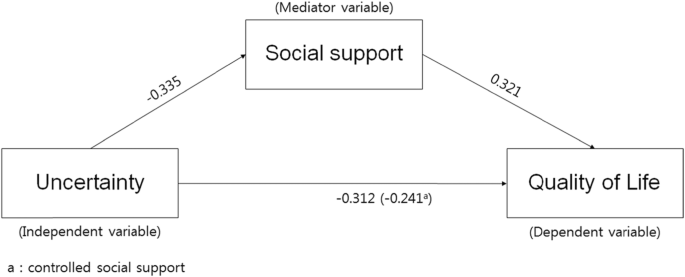

Using the hierarchy regression, this confirmed the partial mediating effects of social support in the process of uncertainty influencing quality of life (Table 6 , Fig. 2 ). The first regression analysis indicated that the independent variable (uncertainty) had a statistically significant influence on the mediator variable (social support; β = − 0.335, p < .001), and the explanatory power for social support was 10.4%. The second stage regression analysis indicated that the mediator variable (social support) had a significant influence on the dependent variable (quality of life; β = 0.321, p < .001), and the explanatory power for quality of life was 9.7%. The third stage regression analysis indicated that the independent variable (uncertainty) had a significant influence on the dependent variable (quality of life; β = − 0.312, p = .001) with an explanatory power of 8.9%. At the fourth stage, this study aimed to test the influence of the independent variable (uncertainty) on the dependent variable (quality of life) with social support as the mediator variable. The results indicated that uncertainty (β = − 0.241, p = .014) and social support (β = 0.213, p = .030) were significant predictors of quality of life. When social support was set as the mediator variable, uncertainty was found to have a significant influence on quality of life; the unstandardized regression coefficient reduced from − 0.396 to − 0.398, indicating a partial mediation of social support. The explanatory power of these variables in terms of quality of life was 12.1%. This study executed the Sobel test to verify the significance of the mediating effects of social support, confirming that they were significant in the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life.

Model showing the influence of uncertainty on quality of life and the mediating effect of social support

Mullen divided the stages of cancer survival into three major classifications [ 32 , 33 ]. First is the acute stage, which marks the period after the cancer diagnosis. Second is the extended stage, in which the active treatment of cancer has ended and the patient is placed under tracking observation or engages in intermittent treatment. During this period, the majority of cancer survivors experience uncertainty toward their cancer treatment and fear recurrence, and they may experience physical and psychological issues. Lastly, the permanent stage marks a period in which the cancer is thought to be fully cured, or the patient is expected to survive long term, with a low risk of recurrence.

The participants in this study averaged a score of 66.90 for quality of life. As it is difficult to draw a direct comparison given the lack of research utilizing this measure, in converting quality of life into a scale of 100 points, this study’s results were similar to those found previously regarding post-hoc management following breast cancer treatment for 200 women [ 8 , 10 ]. However, a study covering regionally based, adult female breast cancer survivors between 6 months and 2 years after anti-cancer treatment completion reported lower scores (e.g., 60.13 points) compared to this study [ 27 ]. Likewise, a study of breast cancer survivors with completed surgeries and assistive treatments, breast cancer survivors whose treatment had ended had scores of 53.4 and 56.66 points, respectively for breast cancer survivors with completed surgeries and assistive treatments [ 25 , 26 ].

On the other hand, a report of 110 adult females with breast cancer or OB/GYN cancers [ 33 ] indicated that quality of life according to cancer survival stage was 58.7, 62.3, and 66.8 points during the acute, extended, and permanent stages, respectively. Quality of life in this study was similar to the level experienced by survivors during the permanent stage. Considering that the average time since treatment was 17.64 months, these results indicate a relatively high quality of life. While these differences cannot be accurately compared and discussed because of the lack of research covering the same variables, the majority of survivors had thyroid cancer (70.9%), and it is known that thyroid cancer has higher rates of survival. Going forward, it is important to develop interventions to improve quality of life by assessing survivors’ specific stages.

There were no significant relationships between quality of life and length of time since completing treatment. Existing research has suggested that quality of life was significantly higher for those surviving more than 5 years after cancer treatment completion [ 8 , 33 ], indicating that quality of life improves as duration of survival increases. The quality of life of these cancer survivors has been reported to improve with the passage of time [ 8 , 33 ]. Therefore, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are required in the future to identify quality of life by survival stage and changes in quality of life over time.

On the other hand, qualitative studies of Korean female cancer survivors have indicated that the significant others and families of female cancer survivors wanted them to return to their pre-cancer lives to take care of their spouses and children, indicated the demands on female cancer survivors in Korea to fulfill their roles as wives and mothers before fully recovering from cancer [ 33 ]. Thus, customized interventions by survival stage for female cancer survivors are needed along with further research on the relationships between cultural specificity, role conflicts imposed on survivors because they are women, and their quality of life.

The uncertainty toward illness of the participants in this study was similar to existing research in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy averaged 83.08 [ 34 ] and female thyroid cancer patients [ 35 ]. On the other hand, the level of uncertainty faced by cancer patients prior to surgery averaged 81.43 in a study of cancer patients hospitalized for breast, thyroid, and bladder cancer [ 36 ], which was slightly lower than the value found in this study. This appears to be because female cancer survivors in this study were mostly in the extended stage, which comes after the active treatment of their cancer [ 32 , 33 ]. Most cancer survivors face uncertainty toward cancer treatment and fear of recurrence [ 8 , 32 , 33 ]; thus, they experience a diverse range of physical and psychological problems [ 6 , 7 ]. On the other hand, a qualitative study of 25 breast cancer survivors aged over 30 who had undergone surgery and chemotherapy as their primary treatment for breast cancer [ 37 ] indicated that quality of life following treatment for breast cancer survivors saw a coexistence of anxiety and uncertainty about recurrence. A shorter duration of time since treatment led to higher confusion in their own health management efforts and health management in general.

These results indicate that there are limitations to comparing uncertainty results given the lack of domestic studies on cancer survivors; therefore, future studies are needed to fill this gap. Moreover, it is necessary to confirm uncertainty by cancer survival stage and develop interventions to reduce the uncertainty accompanying each stage.

Uncertainty in illness was higher for those with less than a high school education, compared to those with a university education or higher, when they were dissatisfied with their financial status, and for those who were smokers. These results were similar to previous research [ 36 ], which indicated high uncertainty for participants over 60 who had a low monthly income and low level of education. Therefore, it is necessary to consider these socioeconomic factors when developing uncertainty reducing strategies such as customized information delivery and communication.

The social support of female cancer survivors in this study was rather high, at 62.62 out of 84 points; family support was the highest, followed by support from significant others, and finally friends. Social support is known to play an important role in helping individuals reduce their levels of uncertainty [ 37 ]. Particularly, in Korea, family and healthcare professional support have been the most important support resources among all social support types [ 34 ]. The results of this study indicated that family support was the highest, which was in line with the results of existing studies. On the other hand, a qualitative study of 25 breast cancer survivors aged over 30 who had undergone surgery and chemotherapy as their primary breast cancer treatments [ 37 ] indicated that positive support and responses from family, patients with similar illnesses, and those surrounding them helped to strengthen positive self-suggestion, which also helped them to overcome their illnesses. Other studies have reported that patients undergoing treatment receive active support from healthcare professionals and their family, but they receive less support and interest from healthcare professionals, their family, and those surrounding them after the treatment ends [ 22 , 23 , 27 ]. Therefore, it is necessary to take a continuous interest in and facilitate social support for cancer survivors.

Social support was higher for participants with average satisfaction toward their financial status, and for those for whom less than a year, or between 1 and 5 years, had passed since the completion of their cancer treatment, compared to those for whom 5 years or more had passed since treatment. These results were similar to those of studies on cancer patients hospitalized for breast, thyroid, and bladder cancer surgery [ 36 ], which indicated social support differed according to the time that had passed since diagnosis. Moreover, these results are similar to those reporting that breast cancer survivors are required by their spouses or family to fulfill roles they had filled prior to their cancer diagnosis, and this was associated with decreasing support from family [ 38 ]. These results indicate that female cancer survivors require ongoing psychosocial support as well as education and access to information as they live out their lives.

According to Baik and Lim [ 20 ], who studied social support according to different stages of breast and gynecological cancer survival, the social support of patients in the acute stage was comparatively higher, but there were no significant differences in social support across the different stages, which was different from the findings of this study. While there were no significant differences, Baik and Lim [ 20 ] reported that the social support perceived by survivors decreased as they proceeded through the acute to the extended stage. The social support perceived by respondents decreased in the 2 years following the diagnosis but maintained the reduced rate through the permanent stage [ 20 ]. Long-term survivors had a greater need to meet other cancer patients and self-help groups [ 20 ]. Kwon and Yi [ 27 ] asserted that interest and support from family and the society in general are very important in raising breast cancer survivors’ quality of life and survival rates. Moreover, self-help groups were reported to be effective in providing emotional support for long- and short-term cancer survivors [ 39 ], which indicates the need for developing stage-specific social support interventions and various methods of facilitating social support groups. Moreover, further research is required concerning cancer survival stage-dependent social support and quality of life.

The results of this study showed that higher uncertainty in illness among female cancer survivors led to reduced social support and quality of life, while higher social support led to better quality of life. Support from others was found to be the most relevant aspect of the relationship between quality of life and uncertainty. These results were similar to those of studies on early-stage breast cancer patients [ 40 ] and on cancer patients hospitalized for breast, thyroid, and bladder cancer surgery [ 36 ], which indicated that perceived social support was lower as uncertainty increased.

Uncertainty was very influential on female cancer survivors’ quality of life. Higher uncertainty in illness among female cancer survivors led to lower social support and reduce quality of life; higher social support led to improved quality of life. The explanatory power of these variables on quality of life was 12.1%; uncertainty in illness and social support influenced the quality of life of female cancer survivors. Moreover, in the process of uncertainty in illness influencing subjects’ quality of life, social support was confirmed to play a significant, partially mediating, role in the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life. Higher uncertainty toward illness led to lower quality of life, higher social support led to higher quality of life, and social support influenced female cancer survivors’ quality of life by partially mediating its relationship with uncertainty. Social support plays an important role in directly and indirectly reducing uncertainty [ 18 , 19 ]. Social support is closely related to the prognosis of breast cancer survivors [ 21 ]. Uncertainty among breast cancer survivors has been found to lower their quality of life; however, social support has been found to improve quality of life [ 11 ]. Thus, the need for a diverse range of attempts, including developing and applying social support programs, to increase cancer survivors’ quality of life exists. On the other hand, the partially mediating effects of social support indicate that there are other mediating factors in uncertainty in illness’s influence on quality of life. Therefore, it is important for future studies to include other mediating factors in their examinations of what influences quality of life among female cancer survivors.

In Korea, studies on cancer survivors have been conducted since 2010, and the majority of these focused on breast cancer survivors. Particularly, as there has been no overall research into the healthy behaviors of cancer survivors, it is necessary to develop practical guidelines that befit Korea through studies concerning the development and application of health improvement programs based on the study of healthy behaviors, as per the assertion of Kim [ 32 ]. Moreover, attempts are needed to practically apply a diverse range of intervention studies to improve cancer survivors’ quality of life.

Moreover, future studies should include mediator variables other than social support that might influence quality of life. Additionally, both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are needed to further investigate the quality of life and uncertainty according to the stages of survival.

Our results show that social support partial mediates the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life in female cancer survivors. The results of this study have great implications for improving cancer care, especially in how it relates to quality of life, and they also demonstrate how uncertainty can be decreased. Therefore, it is necessary to develop and apply intervention methods to improve social support thereby improving quality of life among female cancer survivors. A nurse-led social support program may especially contribute to enhancing the quality of life of cancer survivors by providing them with adequate health information and emotional support.

Availability of data and materials

The data used in this study were collected through questionnaires and analyzed by coding the original data. The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due [REASON WHY DATA ARE NOT PUBLIC] but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Scale

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30

Obstetrics/Gynaecology

Lee JE, Shin DW, Cho BL. The current status of cancer survivorship care and a consideration of appropriate care model in Korea. Korean J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(2):58–62. https://doi.org/10.14216/kjco.14012 .

Article Google Scholar

Yoon HJ, Seok JH. Clinical factors associated with quality of life in patients with thyroid cancer. J Korean Thyroid Assoc. 2014;7(1):62–9. https://doi.org/10.11106/jkta.2014.7.1.62 .

Dow KH, Ferrell BR, Leigh S, Ly J, Gulasekaram P. An evaluation of the quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1996;39(3):261–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01806154 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ferrell BR, Dow KH. Quality of life among long-term cancer survivors. Oncology. 1997;11:565–8.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lee JE, Goo A, Lee KE, Park DJ, Cho B. Management of long-term thyroid cancer survivors in Korea. J Korean Med Assoc. 2016;59(4):287–93. https://doi.org/10.5124/jkma.2016.59.4.287 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Molassiotis A, Yates P, Li Q, So WK, Pongthavornkamol K, Pittayapan P, et al. Mapping unmet supportive care needs, quality-of-life perceptions and current symptoms in cancer survivors across the Asia-Pacific region: results from the international STEP study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2552–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx350 .

Yun YH, Kim YA, Sim JA, Shin AS, Chang YJ, Lee J, et al. Prognostic value of quality of life score in disease-free survivors of surgically-treated lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):505–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-016-2504-x .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Park JH, Jun EY, Kang MY, Joung YS, Kim GS. Symptom experience and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2009;39(5):613–21. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2009.39.5.613 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Chae YR. Relationships of perceived health status, depression, and quality of life of breast cancer survivors. J Korean Adult Nurs. 2005;17:119–27.

Google Scholar

Kim YS, Tae YS. The influencing factors on quality of life among breast cancer survivors. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2011;11(3):221–8. https://doi.org/10.5388/jkon.2011.11.3.221 .

Sammarco A, Konecny LM. Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35(5):844–9. https://doi.org/10.1188/08.ONF.844-849 .

Liao MN, Chen MF, Chen SC, Chen PL. Uncertainty and anxiety during the diagnostic period for women with suspected breast cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2008;31(4):274–83. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NCC.0000305744.64452.fe .

Dirksen S, Erickson J. Well-being in Hispanic and non-Hispanic Caucasian survivors of breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(5):820–6. https://doi.org/10.1188/02.ONF.820-826 .

Husson O, Haak HR, Buffart LM, Nieuwlaat WA, Oranje WA, Mols F, et al. Health-related quality of life and disease specific symptoms in long-term thyroid cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Acta Oncol. 2013;52(2):249–58. https://doi.org/10.3109/0284186X.2012.741326 .

Lee JI, Kim SH, Tan AH, Kim HK, Jang HW, Hur KY, et al. Decreased health-related quality of life in disease-free survivors of differentiated thyroid cancer in Korea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8(1):101. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-8-101 .

Yang J, Yi M. Factors influencing quality of life in thyroid cancer patients with thyroidectomy. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2015;15(2):59–66. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2015.15.2.59 .

Oh KS. Social support as a prescription theory. J Nurs Query. 2006;15(1):134–54.

Lien CY, Lin HR, Kuo IT, Chen ML. Perceived uncertainty, social support and psychological adjustment in older patients with cancer being treated with surgery. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(16):2311–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02549.x .

Mishel MH. Uncertainty in illness. Image J Nurs Sch. 1988;20(4):225–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00082.x .

Baik OM, Lim J. Social support in Korean breast and gynecological cancer survivors: comparison by the cancer stage at diagnosis and the stage of cancer survivorship. Korean J Family Soc Work. 2011;32(6):5–35.

Nausheen B, Kamal A. Familial social support and depression in breast cancer: an exploratory study on a Pakistani sample. Psychooncology. 2007;16(9):859–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.1136 .

Alfano CM, Rowland JH. Recovery issues in cancer survivorship: a new challenge for supportive care. Cancer J. 2006;12(5):432–43. https://doi.org/10.1097/00130404-200609000-00012 .

Ashing KT, Padilla G, Tejero JS, Kagawa-Singer M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Asian American women. Psychooncology. 2003;12(1):38–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.632 .

Janz N, Mujahid M, Chung L, Lantz P, Hawley S, Morrow M, et al. Symptom experience and quality of life of women following breast cancer treatment. J Women's Health. 2007;16(9):1348–61. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.0255 .

Min HS, Park SY, Lim JS, Park MO, Won HJ, Kim JI. A study on behaviors for preventing recurrence and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2008;38(2):187–94. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2008.38.2.187 .

Kim GD. Impact of climacteric symptoms and fatigue on the quality of life in breast cancer survivors: the mediating effect of cognitive dysfunction. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2014;14(2):58–65. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2014.14.2.58 .

Kwon EJ, Yi M. Distress and quality of life in breast cancer survivors in Korea. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2012;12(4):289–96. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2012.12.4.289 .

Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.1173 .

Lee I. Uncertainty, appraisal and quality of life in patients with breast cancer across treatment phases. J Cheju Halla Collage. 2009;33:94–112.

Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric characteristics of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3–4):610–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095 .

Fayers PM, Aaronson NK, Bjordal K, Groenvold M, Curran D, Bottomley A, On behalf of the EORTC Quality of Life Group. EORTC QLQ-C30 scoring manual. 3rd ed. Brussels: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer; 2001. p. 2001.

Kim SH. Understanding cancer survivorship and its new perspectives. J Korean Oncol Nurs. 2010;10(1):19–29.

Lim J, Han I. Comparison of quality of life on the stage of cancer survivorship for breast and gynecological cancer survivors. Korean J Soc Welf. 2008;60(1):5–27. https://doi.org/10.20970/kasw.2008.60.1.001 .

Ahn JY. The influence of symptoms, uncertainty, family support on resilience in patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy [master’s thesis]. Seoul: The Seoul National University; 2014.

Lee I, Park CS. Convergent effects of anxiety, depression, uncertainty, and social support on quality of life in women with thyroid cancer. J Korea Convergence Soc. 2017;8(8):163–76. https://doi.org/10.15207/JKCS.2017.8.8.163 .

Park YJ. Uncertainty, anxiety and social support among preoperative patients of cancer: A correlational study [master’s thesis]. Seoul: The Seoul National University; 2015.

Yun M, Song M. A qualitative study on breast cancer survivors’ experiences. Perspect Nurs Sci. 2013;10:41–51.

Ashing-Giwa KT. The contextual model of HRQoL: a paradigm for expanding the HRQoL framework. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(2):297–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-004-0729-7 .

Adamsen L, Rasmussen J. Sociological perspectives on self-help groups: reflections on conceptualisation and social processes. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35(6):909–17. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01928.x .

Kim HY, So HS. A structural model for psychosocial adjustment in patients with early breast cancer. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012;42(1):105–15. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2012.42.1.105 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Min, a physician of the Endocrine surgery at Cheju Halla Hospital, for collecting the data. And, we would like to thank the IRB who approved the research and the Editage Company who edited the English.

Conflict of interest

“No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).”

The authors did not receive any financial support for this study. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

“This research did not received any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.”

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Nursing, Changwon National University, C.P.O. Box 51140, Changwon, Republic of South Korea

Division of Nursing, Cheju Halla University, Jeju, Republic of South Korea

Changseung Park

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

IL designed the study, searched the literature, analyzed the data, conducted the interpretation of data, drafted and edited the manuscript, and submitted the manuscript for publishing. CSP collected the data, searched the literature, and critically revised the initial manuscript. And all authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Insook Lee .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study approved by IRB in Cheju Halla Hospital (IRB No. 2014-L02) and informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

This manuscript has never been published in any other journal, and all authors agree to be published in this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Lee, I., Park, C. The mediating effect of social support on uncertainty in illness and quality of life of female cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 18 , 143 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01392-2

Download citation

Received : 08 December 2019

Accepted : 05 May 2020

Published : 19 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-020-01392-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes

ISSN: 1477-7525

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

Select "Patients / Caregivers / Public" or "Researchers / Professionals" to filter your results. To further refine your search, toggle appropriate sections on or off.

Cancer Research Catalyst The Official Blog of the American Association for Cancer Research

Home > Cancer Research Catalyst > Cancer Survivors: In Their Words

Cancer Survivors: In Their Words

This year alone, an estimated 1.8 million people will hear their doctor say they have cancer. The individual impact of each person can be clouded in the vast statistics. In honor of National Cancer Survivor Month, Cancer Today would like to highlight several personal essays we’ve published from cancer survivors at different stages of their treatment.

In this essay , psychiatrist Adam P. Stern’s cerebral processing of his metastatic kidney cancer diagnosis gives rise to piercing questions. When he drops off his 3-year-old son to daycare, he ponders a simple exchange: his son’s request for a routine morning hug before he turns to leave. “Will he remember me, only a little, just enough to mythologize me as a giant who used to carry him up the stairs? As my health declines, will he have to learn to adjust to a dad who used to be like all the other dads but then wasn’t?” he questions.

In another essay from a parent with a young child, Amanda Rose Ferraro describes the abrupt change from healthy to not healthy after being diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia in May 2017. After a 33-day hospital stay, followed by weeklong chemotherapy treatments, Ferraro’s cancer went into remission, but a recurrence required more chemotherapy and a stem cell transplant. Ferraro describes harrowing guilt over being separated from her 3-year-old son, who at one point wanted nothing to do with her. “Giving up control is hard, but not living up to what I thought a mother should be was harder. I had to put myself first, and it was the hardest thing I had ever done,” she writes.

In January 1995, 37-year-old Melvin Mann was diagnosed with chronic myelogenous leukemia, which would eventually mean he would need to take a chance on a phase I clinical trial that tested an experimental drug called imatinib—a treatment that would go on to receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval under the brand name Gleevec. It would also mean trusting a system with a documented history of negligence and abuse of Black people like him: “Many patients, especially some African Americans, are afraid they will be taken advantage of because of past unethical experiments like the infamous Tuskegee syphilis study,” Mann writes, before describing changes that make current trials safer. Mann’s been on imatinib ever since and has enjoyed watching his daughter become a physician and celebrating 35 years of marriage.

In another essay , Carly Flumer addresses the absurdity of hearing doctors reassure her that she had a good cancer after she was diagnosed with stage I papillary thyroid cancer in 2017. “What I did hear repeatedly from various physicians was that I had the ‘good cancer,’ and that ‘if you were to have a cancer, thyroid would be the one to get,’” she writes.

In another piece for Cancer Today , Flumer shares how being diagnosed with cancer just four months after starting a graduate program shaped her education and future career path.

For Liza Bernstein, her breast cancer diagnosis created a paradox as she both acknowledged and denied the disease the opportunity to define who she was. “In the privacy of my own mind, I refused to accept that cancer was part of my identity, even though it was affecting it as surely as erosion transforms the landscape,” she writes . “Out in the world, I’d blurt out, ‘I have cancer,’ because I took questions from acquaintances like ‘How are you, what’s new?’ literally. Answering casual questions with the unvarnished truth wasn’t claiming cancer as my identity. It was an attempt to dismiss the magnitude of it, like saying ‘I have a cold.’” By her third primary breast cancer diagnosis, Bernstein reassesses and moves closer to acceptance as she discovers her role as advocate.

As part of the staff of Cancer Today , a magazine and online resource for cancer patients, survivors and caregivers, we often refer to a succinct tagline to sum up our mission: “Practical knowledge. Real hope.” Part of providing information is also listening closely to cancer survivors’ experiences. As we celebrate National Cancer Survivor Month, we elevate these voices, and all patients and survivors in their journeys.

Cancer Today is a magazine and online resource for cancer patients, survivors, and caregivers published by the American Association for Cancer Research. Subscriptions to the magazine are free to cancer patients, survivors and caregivers who live in the U.S.

- About This Blog

- Blog Policies

- Tips for Contributors

FDA Workshop to Address Need for Non-clinical Models to Advance Immuno-oncology

Annual Meeting 2022: Transitions at the National Cancer Institute

Why We Need Tailored Tobacco-control Strategies

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Discussion (max: 750 characters)...

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Share Your Story

- National Cancer Research Month

- National Cancer Survivor Month

- Download PDF

- Share X Facebook Email LinkedIn

- Permissions

Substance Use Disorders Among US Adult Cancer Survivors

- 1 New England Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center, VA Boston Healthcare System, Boston, Massachusetts

- 2 Department of Population Health Sciences, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina

- 3 Division of General Internal Medicine, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- Comment & Response Substance Use Disorders Among Cancer Survivors Alain Braillon, MD, PhD JAMA Oncology

Question What is the cancer type–specific prevalence of substance use disorder (SUD) among adult US cancer survivors?

Findings In this cross-sectional study of 6101 adult cancer survivors who responded to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health for 2015 through 2020, the overall prevalence of active SUD (within the past 12 months) was approximately 4%, with higher prevalence in some subpopulations, including survivors of head and neck cancer (approximately 9%) and esophageal and gastric cancer (approximately 9%). Alcohol use disorder was the most common SUD.

Meaning Findings of this study highlight subpopulations of adult cancer survivors who may benefit from efforts to integrate cancer and addiction care.

Importance Some individuals are predisposed to cancer based on their substance use history, and others may use substances to manage cancer-related symptoms. Yet the intersection of substance use disorder (SUD) and cancer is understudied. Because SUD may affect and be affected by cancer care, it is important to identify cancer populations with a high prevalence of SUD, with the goal of guiding attention and resources toward groups and settings where interventions may be needed.

Objective To describe the cancer type–specific prevalence of SUD among adult cancer survivors.

Design, Setting, and Participants This cross-sectional study used data from the annually administered National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) for 2015 through 2020 to identify adults with a history of solid tumor cancer. Substance use disorder was defined as meeting at least 1 of 4 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (Fourth Edition) criteria for abuse or at least 3 of 6 criteria for dependence.

Main Outcomes and Measures Per NSDUH guidelines, we made adjustments to analysis weights by dividing weights provided in the pooled NSDUH data sets by the number of years of combined data (eg, 6 for 2015-2020). The weighted prevalence and corresponding SEs (both expressed as percentages) of active SUD (ie, within the past 12 months) were calculated for respondents with any lifetime history of cancer and, in secondary analyses, respondents diagnosed with cancer within 12 months prior to taking the survey. Data were analyzed from July 2022 to June 2023.

Results This study included data from 6101 adult cancer survivors (56.91% were aged 65 years or older and 61.63% were female). Among lifetime cancer survivors, the prevalence of active SUD was 3.83% (SE, 0.32%). Substance use disorder was most prevalent in survivors of head and neck cancer (including mouth, tongue, lip, throat, and pharyngeal cancers; 9.36% [SE, 2.47%]), esophageal and gastric cancer (9.42% [SE, 5.51%]), cervical cancer (6.24% [SE, 1.41%]), and melanoma (6.20% [SE, 1.34%]). Alcohol use disorder was the most common SUD (2.78% [SE, 0.26%]) overall and in survivors of head and neck cancer, cervical cancer, and melanoma. In survivors of esophageal and gastric cancers, cannabis use disorder was the most prevalent SUD (9.42% [SE, 5.51%]). Among respondents diagnosed with cancer in the past 12 months, the overall prevalence of active SUD was similar to that in the lifetime cancer survivor cohort (3.81% [SE, 0.74%]). However, active SUD prevalence was higher in head and neck (18.73% [SE, 10.56%]) and cervical cancer survivors (15.70% [SE, 5.35%]). The distribution of specific SUDs was different compared with that in the lifetime cancer survivor cohort. For example, in recently diagnosed head and neck cancer survivors, sedative use disorder was the most common SUD (9.81% [SE, 9.17%]).

Conclusions and Relevance Findings of this study suggest that SUD prevalence is higher among survivors of certain types of cancer; this information could be used to identify cancer survivors who may benefit from integrated cancer and SUD care. Future efforts to understand and address the needs of adult cancer survivors with comorbid SUD should prioritize cancer populations in which SUD prevalence is high.

Read More About

Jones KF , Osazuwa-Peters OL , Des Marais A , Merlin JS , Check DK. Substance Use Disorders Among US Adult Cancer Survivors. JAMA Oncol. 2024;10(3):384–389. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2023.5785

Manage citations:

© 2024

Artificial Intelligence Resource Center

Oncology in JAMA : Read the Latest

Browse and subscribe to JAMA Network podcasts!

Others Also Liked

Select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

Welcome to the Survivor's Review

Encouraging the creative expression of cancer survivors.

Our goal at the Survivor's Review is to publish stories, essays, and poems that are powerful, poignant, and unflinchingly honest. Whether you are a cancer survivor, caregiver, or friend, we invite you to peruse the features in this issue.

We also hope to encourage all survivors to use writing as a tool for emotional and physical healing. In each issue, guest contributors will offer ideas and prompts to get you started. Click here to begin writing now!

Our evolving resources page lists books, websites, and other links with information on the benefits of writing and creative expression.

Also, if you're a cancer survivor or caregiver who has written a piece that has the potential to touch another's soul, please consider submitting your work to the Survivor's Review . We make every effort to respond as soon as possible.

We are interested in your feedback . Please contact us with your comments and suggestions.

We hope you enjoy this issue of Survivor's Review and that you will share this site with other survivors, caregivers and friends.

Question: Who is a cancer survivor? Answer: Anyone living with a history of cancer from the moment of diagnosis through the remainder of life.

Please join our email list so we can alert you to future issues and events. Your information is private and will never be shared.

The Survivor's Review was founded and is maintained by a small all-volunteer staff. As our readership continues to grow, we are finding ourselves in need of another committed volunteer to join our team. If you are inspired by our mission and have writing/reading/editing experience and basic computer skills, we would like to hear from you.

Our goal is to publish two issues per year, in fall and spring, and we are seeking an Associate Editor who will read and catalogue submissions and readers' interest messages, respond via email to writers and readers, and meet via Zoom for a few editorial meetings twice per year. The workload will average no more than three or four hours a month, with those hours concentrated more in the spring and fall, six weeks prior to publication. If interested, please share a bit about your interest and background with our editor, Sheree Kirby, at [email protected] .

DigitalCommons@UNMC

Home > Eppley Institute > Theses & Dissertations

Theses & Dissertations: Cancer Research

Theses/dissertations from 2024 2024.

Novel Spirocyclic Dimer (SpiD3) Displays Potent Preclinical Effects in Hematological Malignancies , Alexandria Eiken

Therapeutic Effects of BET Protein Inhibition in B-cell Malignancies and Beyond , Audrey L. Smith

Identifying the Molecular Determinants of Lung Metastatic Adaptation in Prostate Cancer , Grace M. Waldron

Identification of Mitotic Phosphatases and Cyclin K as Novel Molecular Targets in Pancreatic Cancer , Yi Xiao

Theses/Dissertations from 2023 2023

Development of Combination Therapy Strategies to Treat Cancer Using Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors , Nicholas Mullen

Overcoming Resistance Mechanisms to CDK4/6 Inhibitor Treatment Using CDK6-Selective PROTAC , Sarah Truong

Theses/Dissertations from 2022 2022

Omics Analysis in Cancer and Development , Emalie J. Clement

Investigating the Role of Splenic Macrophages in Pancreatic Cancer , Daisy V. Gonzalez

Polymeric Chloroquine in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Therapy , Rubayat Islam Khan

Evaluating Targets and Therapeutics for the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer , Shelby M. Knoche

Characterization of 1,1-Diarylethylene FOXM1 Inhibitors Against High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma Cells , Cassie Liu

Novel Mechanisms of Protein Kinase C α Regulation and Function , Xinyue Li

SOX2 Dosage Governs Tumor Cell Identity and Proliferation , Ethan P. Metz

Post-Transcriptional Control of the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in Ras-Driven Colorectal Cancers , Chaitra Rao

Use of Machine Learning Algorithms and Highly Multiplexed Immunohistochemistry to Perform In-Depth Characterization of Primary Pancreatic Tumors and Metastatic Sites , Krysten Vance

Characterization of Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in the Immunosuppressed Patient , Megan E. Wackel

Visceral adipose tissue remodeling in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cachexia: the role of activin A signaling , Pauline Xu

Phos-Tag-Based Screens Identify Novel Therapeutic Targets in Ovarian Cancer and Pancreatic Cancer , Renya Zeng

Theses/Dissertations from 2021 2021

Functional Characterization of Cancer-Associated DNA Polymerase ε Variants , Stephanie R. Barbari

Pancreatic Cancer: Novel Therapy, Research Tools, and Educational Outreach , Ayrianne J. Crawford

Apixaban to Prevent Thrombosis in Adult Patients Treated With Asparaginase , Krishna Gundabolu

Molecular Investigation into the Biologic and Prognostic Elements of Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma with Regulators of Tumor Microenvironment Signaling Explored in Model Systems , Tyler Herek

Utilizing Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras to Target the Transcriptional Cyclin-Dependent Kinases 9 and 12 , Hannah King

Insights into Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Pathogenesis and Metastasis Using a Bedside-to-Bench Approach , Marissa Lobl

Development of a MUC16-Targeted Near-Infrared Antibody Probe for Fluorescence-Guided Surgery of Pancreatic Cancer , Madeline T. Olson

FGFR4 glycosylation and processing in cholangiocarcinoma promote cancer signaling , Andrew J. Phillips

Theses/Dissertations from 2020 2020

Cooperativity of CCNE1 and FOXM1 in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer , Lucy Elge

Characterizing the critical role of metabolic and redox homeostasis in colorectal cancer , Danielle Frodyma

Genomic and Transcriptomic Alterations in Metabolic Regulators and Implications for Anti-tumoral Immune Response , Ryan J. King

Dimers of Isatin Derived Spirocyclic NF-κB Inhibitor Exhibit Potent Anticancer Activity by Inducing UPR Mediated Apoptosis , Smit Kour

From Development to Therapy: A Panoramic Approach to Further Our Understanding of Cancer , Brittany Poelaert

The Cellular Origin and Molecular Drivers of Claudin-Low Mammary Cancer , Patrick D. Raedler

Mitochondrial Metabolism as a Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Cancer , Simon Shin

Development of Fluorescent Hyaluronic Acid Nanoparticles for Intraoperative Tumor Detection , Nicholas E. Wojtynek

Theses/Dissertations from 2019 2019

The role of E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXO9 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis , R. Willow Hynes-Smith

BRCA1 & CTDP1 BRCT Domainomics in the DNA Damage Response , Kimiko L. Krieger

Targeted Inhibition of Histone Deacetyltransferases for Pancreatic Cancer Therapy , Richard Laschanzky

Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) Class I Molecule Components and Amyloid Precursor-Like Protein 2 (APLP2): Roles in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Migration , Bailee Sliker

Theses/Dissertations from 2018 2018

FOXM1 Expression and Contribution to Genomic Instability and Chemoresistance in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer , Carter J. Barger

Overcoming TCF4-Driven BCR Signaling in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma , Keenan Hartert

Functional Role of Protein Kinase C Alpha in Endometrial Carcinogenesis , Alice Hsu

Functional Signature Ontology-Based Identification and Validation of Novel Therapeutic Targets and Natural Products for the Treatment of Cancer , Beth Neilsen

Elucidating the Roles of Lunatic Fringe in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma , Prathamesh Patil

Theses/Dissertations from 2017 2017

Metabolic Reprogramming of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cells in Response to Chronic Low pH Stress , Jaime Abrego

Understanding the Relationship between TGF-Beta and IGF-1R Signaling in Colorectal Cancer , Katie L. Bailey

The Role of EHD2 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Tumorigenesis and Progression , Timothy A. Bielecki

Perturbing anti-apoptotic proteins to develop novel cancer therapies , Jacob Contreras

Role of Ezrin in Colorectal Cancer Cell Survival Regulation , Premila Leiphrakpam

Evaluation of Aminopyrazole Analogs as Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors for Colorectal Cancer Therapy , Caroline Robb

Identifying the Role of Janus Kinase 1 in Mammary Gland Development and Breast Cancer , Barbara Swenson

DNMT3A Haploinsufficiency Provokes Hematologic Malignancy of B-Lymphoid, T-Lymphoid, and Myeloid Lineage in Mice , Garland Michael Upchurch

Theses/Dissertations from 2016 2016

EHD1 As a Positive Regulator of Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor-1 Receptor , Luke R. Cypher

Inflammation- and Cancer-Associated Neurolymphatic Remodeling and Cachexia in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma , Darci M. Fink

Role of CBL-family Ubiquitin Ligases as Critical Negative Regulators of T Cell Activation and Functions , Benjamin Goetz

Exploration into the Functional Impact of MUC1 on the Formation and Regulation of Transcriptional Complexes Containing AP-1 and p53 , Ryan L. Hanson

DNA Polymerase Zeta-Dependent Mutagenesis: Molecular Specificity, Extent of Error-Prone Synthesis, and the Role of dNTP Pools , Olga V. Kochenova

Defining the Role of Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation in the Regulation of Gap Junction Proteins , Hanjun Li

Molecular Mechanisms Regulating MYC and PGC1β Expression in Colon Cancer , Jamie L. McCall

Pancreatic Cancer Invasion of the Lymphatic Vasculature and Contributions of the Tumor Microenvironment: Roles for E-selectin and CXCR4 , Maria M. Steele

Altered Levels of SOX2, and Its Associated Protein Musashi2, Disrupt Critical Cell Functions in Cancer and Embryonic Stem Cells , Erin L. Wuebben

Theses/Dissertations from 2015 2015

Characterization and target identification of non-toxic IKKβ inhibitors for anticancer therapy , Elizabeth Blowers

Effectors of Ras and KSR1 dependent colon tumorigenesis , Binita Das

Characterization of cancer-associated DNA polymerase delta variants , Tony M. Mertz

A Role for EHD Family Endocytic Regulators in Endothelial Biology , Alexandra E. J. Moffitt

Biochemical pathways regulating mammary epithelial cell homeostasis and differentiation , Chandrani Mukhopadhyay

EPACs: epigenetic regulators that affect cell survival in cancer. , Catherine Murari

Role of the C-terminus of the Catalytic Subunit of Translesion Synthesis Polymerase ζ (Zeta) in UV-induced Mutagensis , Hollie M. Siebler

LGR5 Activates TGFbeta Signaling and Suppresses Metastasis in Colon Cancer , Xiaolin Zhou

LGR5 Activates TGFβ Signaling and Suppresses Metastasis in Colon Cancer , Xiaolin Zhou

Theses/Dissertations from 2014 2014

Genetic dissection of the role of CBL-family ubiquitin ligases and their associated adapters in epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis , Gulzar Ahmad

Strategies for the identification of chemical probes to study signaling pathways , Jamie Leigh Arnst

Defining the mechanism of signaling through the C-terminus of MUC1 , Roger B. Brown

Targeting telomerase in human pancreatic cancer cells , Katrina Burchett

The identification of KSR1-like molecules in ras-addicted colorectal cancer cells , Drew Gehring

Mechanisms of regulation of AID APOBEC deaminases activity and protection of the genome from promiscuous deamination , Artem Georgievich Lada

Characterization of the DNA-biding properties of human telomeric proteins , Amanda Lakamp-Hawley

Studies on MUC1, p120-catenin, Kaiso: coordinate role of mucins, cell adhesion molecules and cell cycle players in pancreatic cancer , Xiang Liu

Epac interaction with the TGFbeta PKA pathway to regulate cell survival in colon cancer , Meghan Lynn Mendick

Theses/Dissertations from 2013 2013

Deconvolution of the phosphorylation patterns of replication protein A by the DNA damage response to breaks , Kerry D. Brader

Modeling malignant breast cancer occurrence and survival in black and white women , Michael Gleason

The role of dna methyltransferases in myc-induced lymphomagenesis , Ryan A. Hlady

Design and development of inhibitors of CBL (TKB)-protein interactions , Eric A. Kumar

Pancreatic cancer-associated miRNAs : expression, regulation and function , Ashley M. Mohr

Mechanistic studies of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) , Xiaming Pang

Novel roles for JAK2/STAT5 signaling in mammary gland development, cancer, and immune dysregulation , Jeffrey Wayne Schmidt

Optimization of therapeutics against lethal pancreatic cancer , Joshua J. Souchek

Theses/Dissertations from 2012 2012

Immune-based novel diagnostic mechanisms for pancreatic cancer , Michael J. Baine

Sox2 associated proteins are essential for cell fate , Jesse Lee Cox

KSR2 regulates cellular proliferation, transformation, and metabolism , Mario R. Fernandez

Discovery of a novel signaling cross-talk between TPX2 and the aurora kinases during mitosis , Jyoti Iyer

Regulation of metabolism by KSR proteins , Paula Jean Klutho

The role of ERK 1/2 signaling in the dna damage-induced G2 , Ryan Kolb

Regulation of the Bcl-2 family network during apoptosis induced by different stimuli , Hernando Lopez

Studies on the role of cullin3 in mitosis , Saili Moghe

Characteristics of amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2) in pancreatic cancer and Ewing's sarcoma , Haley Louise Capek Peters

Structural and biophysical analysis of a human inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase polymorphism , Peter David Simone

Functions and regulation of Ron receptor tyrosine kinase in human pancreatic cancer and its therapeutic applications , Yi Zou

Theses/Dissertations from 2011 2011

Coordinate detection of new targets and small molecules for cancer therapy , Kurt Fisher

The role of c-Myc in pancreatic cancer initiation and progression , Wan-Chi Lin

The role of inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase (ITPA) in maintanence [sic] of genomic stability in human cells , Miriam-Rose Menezes

- Eppley Institute Website

- McGoogan Library

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Survivors learn to live fully with a cancer diagnosis

Steffanie, age 57, describes herself as an artist, a gardener, an associate creative director and a cancer survivor. When she was diagnosed with cancer in 2021, she asked about 20 people she knew who were cancers survivors the same question: When it comes to treatment, what would you always choose to do again? One person told her something that changed her life: Talk to a cancer therapist.

“I’d never heard of a cancer therapist,” says Steffanie, who met with Bonnie McGregor, Ph.D., at Seattle’s Orion Center for Integrative Medicine, a program of Harmony Hill. “She helped me manage the emotional aspects of dealing with a life-threatening illness. For me, it was mainly anxiety and fear. That hasn’t gone away completely, but I now have skills like visualization and breathing exercises that continue to help immensely.”

“Science clearly supports the connection between emotional well-being and overall physical health,” says McGregor, who has contributed to dozens of research studies exploring the mind-body connection in cancer patients and survivors. “But we don’t see emotional health included as part of the prescription for people with a cancer diagnosis, offered alongside nutrition, sleep, exercise, and medication. That’s changing but it’s a slow journey, taking as long as 17 years for peer-reviewed research to make its way into clinical practice.”

Health-related quality of life

Research at the National Cancer Institute shows that, like Steffanie, nearly 70% of people diagnosed with cancer will live five-plus years. But just because the disease is in remission, that doesn’t mean life returns to normal for survivors. One study published in the journal Cancer examined nearly 500 cancer patients for post-traumatic stress disorder markers. Nearly 22% of patients experienced markers of PTSD six months post-diagnosis, and about one-third of those patients were still experiencing persistent symptoms — in many cases worsening — at the four-year follow-up.

Research is also finding a direct relationship between a person’s Health-Related Quality of Life, an individual’s perceived physical and mental health over time, and health outcomes. Conditions such as social isolation, stress and/or depression can be associated with key biological processes promoting tumor progression as well as poorer survival.

Harmony Hill’s retreats and other programs, designed and led by medical professionals, therapists and a chaplain, offer a host of techniques and experiences that promote a sense of connection with others and life, reduce fear and stress, encourage self-care and promote wellness. Harmony Hill’s outcomes demonstrate that over 90% of cancer retreat participants report:

- Increased sense of well-being.

- Increased awareness of the value of self-care.

- Increased sense of connection with others and with life.

- Decreased stress.

- Decreased fear and anxiety.

Community support is key for cancer survivors

McGregor referred Steffanie to an 11-week virtual support group she leads for those undergoing cancer treatment and survivors, Living SMART with Cancer. Participants learn mindfulness and relaxation practices to reduce stress and enhance overall well-being, as well build community.

“These were people with different types of cancer, in different stages, who all knew what I was going through,” Steffanie says. “They could give me perspective and support in a way no one else could. It was such an inspiring and healing place to be every week, with other like souls who were not afraid to be themselves. Not afraid to be afraid.”

Steffanie and about a dozen of her Smart Group members later met for a Harmony Hill three-day Cancer Retreat. One of the last things they did was to write letters to their future selves. Steffanie wrote, in part: “I’m writing to remind you what’s important to you: peace, love, joy, and real connection — deep connection. Remember what it felt like to be in your body and take good care of it. Remember what it felt like to be in truth and fully in heart. Remember what’s important. Remember to show compassion for self and others. Remember that the fog will lift, and the beauty that was there the entire time will show itself. Be kind and compassionate to yourself today. Make the time to love yourself and enjoy the gifts of the moment.”