Research management

Sponsored by

What does a research supervisor do?

Research supervisors must learn to be authentic mentors, as well as sharing their experience and knowledge. Robert Crammond reflects on his time in the role

Robert Crammond

Elsevier helps researchers and healthcare professionals advance science and improve health outcomes for the benefit of society.

Discover elsevier.

Created in partnership with

You may also like

Popular resources

.css-1txxx8u{overflow:hidden;max-height:81px;text-indent:0px;} Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn?

A diy guide to starting your own journal, universities, ai and the common good, artificial intelligence and academic integrity: striking a balance, create an onboarding programme for neurodivergent students.

Sharing expertise and experience of academia will come naturally to most academics, but acting as a source of developmental support might not, at least not initially.

Over the last decade, I’ve had the privilege of supervising many students at various stages of their academic journeys. Some have been undergraduate students working on their dissertations, some postgraduate master’s students, while others have been working on their doctoral theses. Here I share my advice based on what I’ve learned during my time as a research supervisor and the five key aspects of the supervisory role.

Set realistic goals

First, as supervisors embark on new projects, they should be realistic with their goals – and this is also the case for the supervisees. In short, a work-life balance must be met to ensure that progress is not at the expense of health and well-being. Setting appropriate milestones to effectively respond to the demands of the project is crucial. This should allow time for priorities to be met, while also putting welfare at the forefront.

- Five tips for building healthy academic collaborations

- How to change research cultures to suppor t the well-being of PhD students

- No one agrees on what research leadership is, let alone how to do it well

Across the term or semester, confirm a number of mini-deadlines and ensure that simple catch-ups take place every seven to 10 days. I’ve found that setting these rules helps to reassure students and maintains their focus.

Communicate to gain context

It is vital that supervisors understand new and ongoing factors affecting their research. This appreciation of context, and engaging in conversation about it, both motivates researchers and increases the validity of the work in question. It also helps in understanding any gaps, problems or challenges within the topics. Students and new researchers will feel included and valued as they begin their investigations.

As a key starting point – ask relevant questions. What is the situation that this research topic concerns? Who is involved? What are the impacting factors and where can more information be found?

Be the mentor, not a research robot

Being knowledgeable is fundamental to being a successful and competent supervisor – but so is being relatable. Those you are working with need to know that you care about them not only as colleagues, but also as individuals. Be aware of (and willing to talk about) how the research journey affects each researcher and their family and how it can lead to sacrifices being made in day-to-day life. Being approachable builds strong working relationships and ultimately leads to a positive research culture.

Supervisors should emphasise that the journey has its ups and downs. They should encourage students and research groups to take time to relax, recharge and enjoy their hobbies and interests . A focus solely on work is not sensible or sustainable. The role of the supervisor is not merely about meeting research objectives – it’s about helping students become well-rounded and successful individuals.

Manage workloads

For many academics and research students, workload consists of both teaching and research and can feel rather intense. That’s not to mention role-specific duties, which obviously vary. Agreeing on what is the priority term-to-term results in working smarter and more efficiently.

Consider the many responsibilities your team members are juggling and plan effectively. Target specific conferences or external engagement activities relevant to the research focus, to confirm writing projects and timelines for research within the calendar year.

Emphasise exposure and impact

Effective supervisors ensure that their students and groups are part – and feel part – of their research communities. They also ensure the work they are supervising is visible on the widest possible scale and that the supervisee understands why this is important. What is the purpose of research if it is not shared and placed firmly in the public sphere? If we are to make an impact on society, we must talk about what we are doing.

Pose the following questions to your supervisees at the beginning and end of the journey: What are the (expected) contributions of this research? What knowledge or subject area does this research advance? Where is the significant value? Most importantly, who benefits – and how?

Reflecting on my career as a research supervisor has helped me identify the challenges that need to be addressed in the role. Above all, being an authentic mentor who is approachable, takes workloads into consideration, prioritises work-life balance and provides reassurance will benefit everyone.

Robert Crammond is a senior lecturer at the University of the West of Scotland.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter .

Emotions and learning: what role do emotions play in how and why students learn?

Global perspectives: navigating challenges in higher education across borders, how to help young women see themselves as coders, contextual learning: linking learning to the real world, authentic assessment in higher education and the role of digital creative technologies, how hard can it be testing ai detection tools.

Register for free

and unlock a host of features on the THE site

- Open access

- Published: 13 May 2022

Research supervisors’ views of barriers and enablers for research projects undertaken by medical students; a mixed methods evaluation of a post-graduate medical degree research project program

- Joanne Hart ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9473-0383 1 ,

- Jonathan Hakim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0232-8953 1 ,

- Rajneesh Kaur ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4406-4327 1 ,

- Richmond Jeremy ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1281-0505 1 ,

- Genevieve Coorey ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4624-9947 2 ,

- Eszter Kalman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9900-6987 3 ,

- Rebekah Jenkin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8071-9183 4 &

- David Bowen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7965-5581 1

BMC Medical Education volume 22 , Article number: 370 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

2837 Accesses

9 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Medical degree programs use scholarly activities to support development of basic research skills, critical evaluation of medical information and promotion of medical research. The University of Sydney Doctor of Medicine Program includes a compulsory research project. Medical student projects are supervised by academic staff and affiliates, including biomedical science researchers and clinician-academics. This study investigated research supervisors’ observations of the barriers to and enablers of successful medical student research projects.

Research supervisors ( n = 130) completed an anonymous, online survey after the completion of the research project. Survey questions targeted the research supervisors’ perceptions of barriers to successful completion of projects and sources of support for their supervision of the student project. Data were analysed by descriptive statistics and using manifest content analysis. Further quantitative investigation was made by cross-tabulation according to prior research supervision experience.

Research supervisors reported that students needed both generic skills (75%) and research-based skills (71%) to successfully complete the project. The major barrier to successful research projects was the lack of protected time for research activities (61%). The assessment schedule with compulsory progress milestones enabled project completion (75%), and improved scientific presentation (90%) and writing (93%) skills. Supervisors requested further support for their students for statistics (75%), scientific writing (51%), and funding for projects (52%). Prior research supervision experience influenced the responses. Compared to novice supervisors, highly experienced supervisors were significantly more likely to want students to be allocated dedicated time for the project ( P < 0.01) and reported higher rates of access to expert assistance in scientific writing, preparing ethics applications and research methodology. Novice supervisors reported higher rates of unexpected project delays and data acquisition problems ( P < 0.05). Co-supervision was favoured by experienced supervisors but rejected by novice supervisors.

Conclusions

Both generic and research-related skills were important for medical student research project success. Overall, protected research time, financial and other academic support were identified as factors that would improve the research project program. Prior research supervision experience influences perceptions of program barriers and enablers. These findings will inform future support needs for projects and research supervisor training for the research supervision role.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Medical education programs increasingly employ scholarly activities to support development of basic research skills, the ability to critically evaluate medical information and the practice of evidence-based medicine [ 1 ]. Furthermore, research activities undertaken by students can foster life-long interest in medical research [ 2 , 3 , 4 ]. This is crucial for the development of clinician-academics, who have key roles in clinical research and translational medicine [ 5 ]. There are declining numbers of clinician-academics in Australia [ 6 ] and globally [ 7 ], thus the importance of fostering interest in research in medical students is imperative.

The University of Sydney 4-year post-graduate Doctor of Medicine Degree (MD) is unique, enrolling students from a wide range of previous academic backgrounds and with various prior research and employment experiences. As an integral and compulsory component of the MD Program curriculum, the research project (MD Project) is delivered as 320 study hours over 2.5 years, from mid-Year 1 to the end of Year 3. Students receive 40 h of training in research methods, basic statistics and research ethics at the end of Year 1, shortly after they commence their projects. Students complete their research project on top of the overall MD program curriculum, without protected research time.

The pedagogical framework for the MD Project program employs active, experiential, project-based learning in a research context with individual projects being supervised by academic staff mentors or mentoring teams. The intended learning objectives of the MD Project are summarised in Table 1 .

In the course of the research project, students need to develop key research and generic skills, including self-motivation, time management and organisation, and building relationships in clinical and research laboratory environments. Students achieve these aims through hands-on experience in devising and conducting a project relevant to health or medicine, analysing the findings, and reporting the results. The scope of MD Projects is broad and includes clinical studies, projects in biomedical science, epidemiology and public health, medical education, bioinformatic and information technology and policy, law, and ethics. A series of compulsory milestone assessments are designed to facilitate progress of each project towards completion. These Milestone tasks include an early project outline, a full appraisal of the ethical implications of the project and verification that ethics approval has been obtained, a structured literature search strategy, and progress reports involving written and oral scientific presentations. The final assessment task is a 3000-word scientific report. Many students were encouraged to present at conferences or prepare manuscripts for peer-reviewed journals, however these were not requirements of the MD Project program. Students are supervised individually or in small groups (usually 2–5 students) by academic staff and affiliates, including basic research scientists, public health researchers and clinicians. The majority of supervisors are not directly employed Faculty members, but University affiliates, who are not specifically remunerated for their time. Supervisors were not required to have a PhD or any formal research supervision training. No Faculty funding was provided to support the project or its supervision. Supervisors were required to provide all project materials and expertise and would supervise up to 6 students at a time. Many supervisors were based in public hospitals and took on MD Project supervision in addition to their existing clinical and/or research workloads.

The research supervisor has a key role in the success of this traditional model of research project [ 8 ]; however, research supervision experience varies from very limited to extensive. Although research supervision training for supervisors of higher degree students is common worldwide and often mandatory, most academics learn to supervise research students “on-the-job” and by emulating their own research mentors [ 9 ]. Currently, there is no formal training provided for the supervisors of MD Projects, or for those supervising similar short-term research projects by undergraduates, including Honours degrees [ 10 ]. Whilst there is evaluation data available for similar research project programs from the students’ viewpoint [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ], the perspective of the supervisors is under-reported. Given the key role of the supervisor in this research education model, their experiences are an important source of information to guide future program improvements.

This study sought the views of research supervisors on the MD Project program and their experiences of supervising medical student research projects, including:

observations on the barriers to and enablers of successfully completing an MD Project,

sources of support for their supervision of the project,

extent of research supervision experience on attitudes to and overall experience of supervising the MD projects,

requirements for professional development or other assistance.

Materials and methods

Study design.

This study is a mixed methods evaluation of the MD Project program from the perspective of the research supervisors.

Participants

MD Project research supervisors were invited by email to complete an anonymous online survey following the completion of the student projects in 2018 and 2020. Participants were University academic staff and appropriately qualified affiliates, including basic research scientists and clinicians. Participants had varying levels of previous research supervision experience, ranging from none to supervision of post-graduate research degree completions. Their areas of research expertise were broad though based in health and medical research. There were no exclusion criteria. Consent to participate was inferred if participants opted to complete and submit an online survey.

Survey tool

The survey tool was developed specifically for this program and was reviewed and refined by MD Program Faculty members, including some research supervisors, to optimise face and content validity. The survey consisted of 30 items, mostly on a 5-point Likert-type scale (with responses of not at all, slightly, moderately, very, extremely ), with optional text responses. Some items required selection of multiple responses from a given list. Survey domains included participant demographics and prior research supervision experience, their overall experience of supervising MD Projects, enablers for and barriers to successful completion of the project (at the MD Program, project, supervisor and student level) and resources and support needed for the supervision role. Participants were provided with a link to the survey within an email invitation to participate; responses were anonymous and aggregate data are shown. The survey tool is available upon request from the authors.

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to explore the overall patterns of response, and qualitative content analysis was used to examine the responses to open ended questions. MD Project supervisors were divided into three categories of research supervision experience: novice (no prior research supervision), moderately experienced (supervised any one of: summer research projects of duration 6–10 weeks, undergraduate Honours projects of up to 6 months or post-graduate research degrees) and highly experienced, (all of the abovementioned supervision types) based on their responses to the survey. Descriptive analysis and Chi Square test including the Mantel–Haenszel test of trend were used to assess any differences in responses between the supervisor experience groups. P < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. Quantitative analyses were carried out in SPSS V26 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Responses from open ended questions were analysed through qualitative methods using manifest content analysis [ 15 ]. Initially deductive coding for explicit phrases was carried out. These codes were then contextualised with the research question of the study. This was followed by generation of homogenous categories from the codes. Conclusions were drawn through investigator triangulation.

Response rates and Faculty respondent demographics

Survey responses were collected from two cohorts of MD Project supervisors, following the completion of the project. From 463 MD Project supervisors’ invitations, 130 (28%) responded. Most respondents identified as clinical researchers, followed by public health academics and biomedical science researchers (Table 2 ). Others had expertise in medical education, bioinformatics, information technology and health-related policy, law, or medical ethics. Many identified multiple areas of expertise.

Faculty research supervision expertise

MD Project supervisors are required to be academic staff or affiliates of the University, however there are no other specific requirements to become a supervisor. Approximately 60% of the respondents were highly experienced research supervisors across a range of project types and duration. One third had moderate experience supervising either summer research project students, Honours Degree students or post-graduate research students. Ten percent of the supervisors had no previous research supervision experience (Table 2 ).

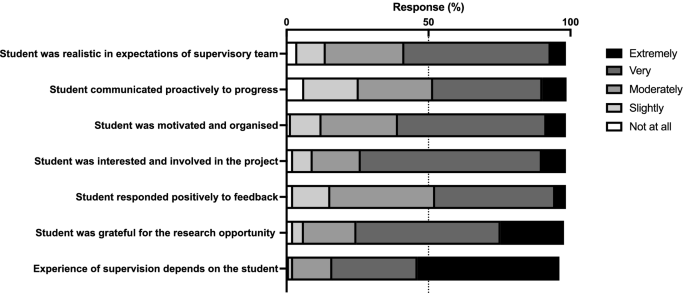

Student-Supervisor relationship

About half (47%) of the supervisors felt their feedback on student performance was only moderately well received (Fig. 1 ), though the majority (73%) of supervisors felt the students were grateful for the opportunity to do research with their team (Fig. 1 ). Supervisors reported that students were organised and interested in their projects and were moderately proactive in communications. Overall, there was agreement amongst MD Project supervisors (86%) that their experience of supervision was very dependent on the individual student (Fig. 1 ).

Student-Supervisor relationship items. Supervisors responded to a number of items related to the student-supervisor relationship on a Likert scale from not at all to extremely. Percentage of responses are shown

Enablers for successful completion of the research project

Student skills needed to successfully complete the md project.

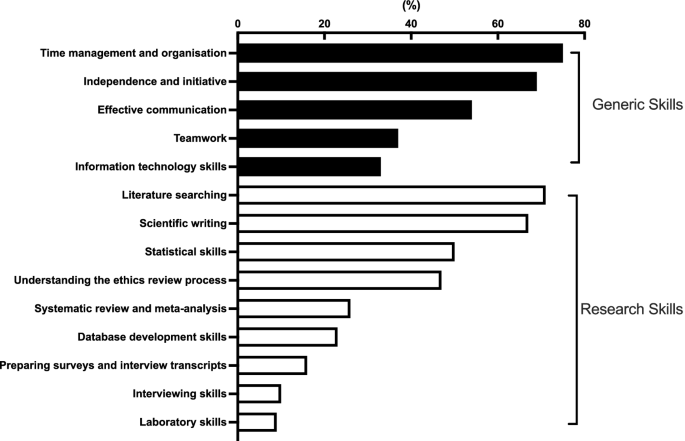

Respondents identified skills that students needed for successfully completing their MD Project, these are presented in Fig. 2 . These were often generic skills, including time management and organisation, independence and initiative and effective communication skills. The top research skills needed included literature searching, scientific writing, statistical skills and navigating the ethics review process (Fig. 2 ). Task-specific skills such as familiarity with information technology and databases were considered less critical, which may reflect the mix of projects undertaken.

Research supervisors’ perceptions of skills students needed for completing research projects. Percentage of supervisors ( n = 130) who selected these items from a list of generic and research skills needed in the student research project

Assessment schedule

There were mixed views on the utility of the milestone assessment tasks, which are presented in Table 3 . The majority of respondents reported that compulsory milestone assessment tasks helped students make progress on their project, though only half thought the tasks were necessary to maintain momentum or hold students accountable to the standards required. About one-third reported that milestones assured the supervisor that the student was progressing as expected. Novice supervisors generally rated the assessment tasks as more useful than the experienced supervisors (Table 3 ). The oral presentations were rated as very useful for student progress, helping them learn to accept and respond to feedback and develop their scientific presentation skills. Preparing a final scientific report was strongly viewed as a very useful activity (Table 3 ).

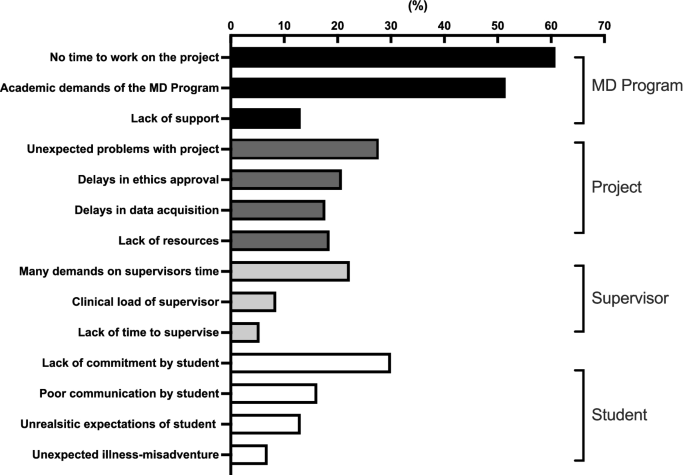

Barriers to successful completion of the research project

Potential impediments for MD project success fell into four broad groups: Program level, project level, supervisor-related and student-related (Fig. 3 ). The principal barriers were at program level, with lack of dedicated time for the project and competing academic demands on students of the overall MD Program being most frequently cited (Fig. 3 ). At project level, unexpected problems, such as delays in data acquisition and time taken for Ethics Committee review and approval were reported. Supervisor time constraints reflected clinical load and other demands. Lack of previous research experience, or lack of commitment to the project were student-related characteristics that were identified as important barriers.

Barriers to successful completion of MD Projects reported by supervisors. Percentage of supervisors ( n = 130) that selected these items from a list of barriers to successfully completing the research project. These barriers were grouped in relation to the MD Program, the project, the supervisor or the student

Challenges described by MD Project supervisors in free text responses indicated a range of other concerns mostly related to student issues but also to their own role as supervisor. They report that a major challenge for the students was competing priorities for learning. The MD Project Milestone tasks therefore became extrinsic motivators and barriers to overcome instead of activities that meaningfully contributed to their learning. This was particularly evident in students competing milestones ‘just in time’ leaving little opportunity for meaningful feedback from supervisors. Other difficulties cited were students having no research or science background as reflected in the following quotes:

“The students struggle to maintain any momentum with their MD Projects as they prioritise other aspects of the MD Program and other deadlines (naturally), so the MD Project often is done all in a rush near the milestone deadlines which is then challenging for supervisors to find the time for a large number of students who need help.” (Experienced Supervisor, Epidemiologist) “Most (students) have a poor understanding of research and stats. This was especially the case with one student from a non-science background.” (Moderately Experienced Supervisor, Clinician)

Challenges cited for MD Project supervisors included the demands of completing other parts of the course and MD Project simultaneously, demanding or disengaged students, a large number of students to supervise, and a lack of time or competing priorities or deadlines. It was reported by some that this type of project supervision was not a good fit for a full-time researcher.

“Of the 11 students I have been involved with, even though all have done well many are very disengaged until the last week or two of the projects, then very demanding for input into their report.” (Experienced Supervisor, Clinician & Biomedical Researcher) “The students have so many competing demands that the MD Project is a real challenge for everyone. As a full-time researcher, fitting such students into my main program is not a good fit.” (Experienced Supervisor, Clinician)

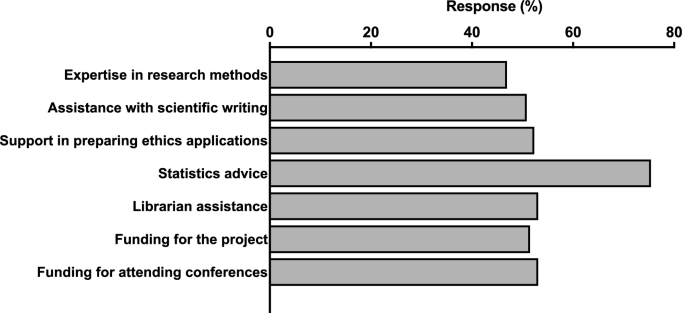

Supervision support for MD projects

Only 11% of respondents said they had all the resources they needed to run the MD Project. The respondents indicated that more support was required for statistics, ethics applications, scientific writing, research methods, and funding both for the project costs and for students to attend conferences (Fig. 4 ).

Support and resources needed by MD Project supervisors. Percentage of supervisors ( n = 130) that selected these items from a list of supports and resources needed for the MD Project

Effect of prior research supervision experience on responses

Prior research supervision experience did not affect the perception of the generic skills that supervisors felt students needed to successfully complete their MD Project. However, skills that were more highly regarded by novice supervisors included skills in literature searching (92%), database development (46%) and understanding the ethics review process (69%). Highly experienced supervisors were more likely to cite independence and initiative (75%) as a required skill than novice supervisors (47%). It is notable that novice supervisors recorded a higher agreement with the utility of the assessment tasks than the overall respondent data (Table 3 ). Regarding the student-supervisor relationship, there was no difference in responses by prior research supervision experience.

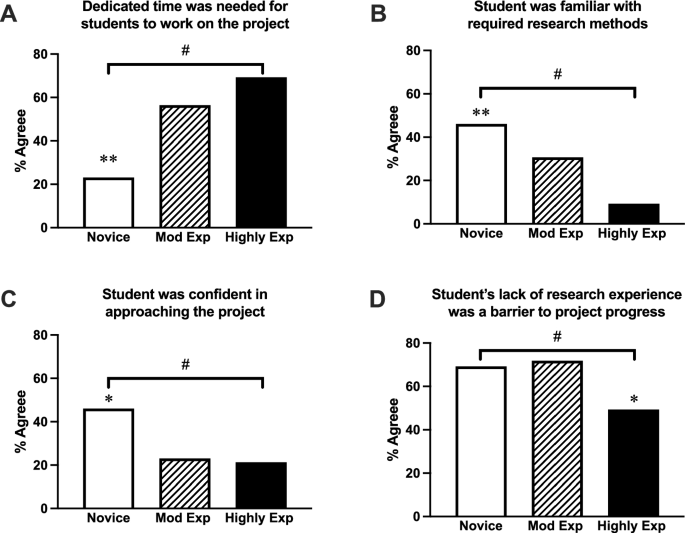

Interestingly, although overall the major barrier cited was a lack of dedicated time for the MD Project (Fig. 3 ), novice supervisors were significantly less likely to want a dedicated time for the project (23%) compared with highly experienced supervisors (69%, χ 2 = 10.351, P = 0.005 Fig. 5 A). Lack of dedicated time for the MD Project was recognised as a barrier which increased with supervision experience (Mantel–Haenszel test of trend, P = 0.002, Fig. 5 A). Further, highly experienced supervisors were significantly less likely to identify the student’s lack of previous research experience as a barrier (49%) compared to moderately experienced (72%) and novice supervisors and this trend was statistically significant (69.2%, χ 2 = 6.040, P = 0.049). A significant trend of this being less of a barrier was noted with increasing supervision experience (Mantel–Haenszel test of trend, P = 0.031, Fig. 5 D). Novice supervisors were significantly more likely to rate their students at the outset of the project as being familiar with research methods (χ 2 = 13.431, P = 0.001). A significant trend was noted for this rating by supervision experience (Mantel–Haenszel test of trend, P = 0.005, Fig. 5 B). Novice supervisors also felt that students were more confident in approaching their project than experienced supervisors and this trend was statistically significant (χ 2 = 6.348, P = 0.042) and associated with supervision experience (Mantel–Haenszel test of trend, P = 0.046, Fig. 5 C). No novice supervisors reported they had a lack of time for supervision, although novice supervisors identified their clinical load as a barrier (15%) more often than experienced supervisors (8%).

Novice supervisors’ appraisal of student research capabilities. A Novice supervisors were significantly less likely to want a dedicated time for the project, ( B ) were more likely to consider their students familiar with research methodology and ( C ) confident in approaching the project. D Highly experienced supervisors were significantly less likely to cite their student’s lack of previous research experience as a barrier compared to moderately experienced and novice supervisors. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, χ 2 -test; # = P < 0.05, Mantel–Haenszel test of trend, by supervisor experience

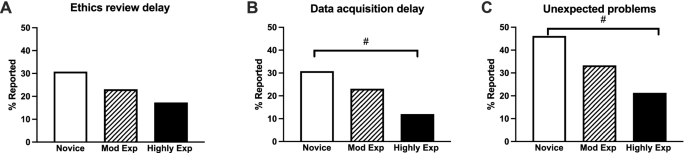

Notably, compared to experienced supervisors, novice supervisors reported higher rates of project delays due to ethics committee review (χ 2 = 1.463, P = 0.481, Fig. 6 A) where a trend by supervision experience is observed but does not reach statistical significance. They also report increased rate of data acquisition problems (χ 2 = 4.026, P = 0.134, Fig. 6 B), and unexpected project problems (χ 2 = 4.359, P = 0.113, Fig. 6 C). A significant trend was observed by supervision experience (Mantel–Haenszel test of trend, P = 0.047, Fig. 6 B, P = 0.038, Fig. 6 C). Highly experienced supervisors reported significantly higher rates of access to expert assistance particularly in scientific writing (novice 7.7% vs highly experienced 21.3%, χ 2 = 8.251, P = 0.016), and there was a significant trend with supervision experience (Mantel–Haenszel test of trend, P = 0.005). In addition, highly experienced supervisors reported twice the access to expertise for preparing ethics approval applications (novice 15.4% vs highly experienced 37.3%) and research methodology advice (novice 15.4% vs highly experienced 38.7%) compared to novice supervisors, though this does not reach statistical significance. Those with moderate prior supervision experience were significantly more likely to want orientation sessions for the MD Project (χ 2 = 8.519, P = 0.014). None of the novice supervisors wanted co-supervision and few sought increased involvement of expert advisors (8%), whereas moderately and highly experienced supervisors were open to these options (16–20%).

Novice supervisors’ reported rates of project delays or problems. MD Project delays, due to ( A ) ethics approval, ( B ) data acquisition or ( C ) unexpected problems were more often reported with novice supervisors, with a decreasing trend in delays as supervision experience increased (# = P < 0.05, Mantel–Haenszel test of trend, by supervisor experience)

Content analysis of free text comments revealed differences in perceptions of the contributions of supervisors to the MD Project program. The more experienced supervisors felt they had a responsibility to participate in the MD project as supervisors, with specific reference to the need for experience to support the student cohort and the difficulty of the task. Novice supervisors noted that they were gaining professional skills as a result of supervising the students. Thus, experienced supervisors felt they were giving something to the program, whereas novice supervisors felt they themselves received a benefit from the program.

“For us who are experienced supervisors, we need to do this to help out the Faculty and the MD program. This is not for inexperienced supervisors.” (Experienced Supervisor, Clinician) “There are a large number of students and relatively few tutors with research experience, so I feel there is a responsibility to participate.” (Experienced Supervisor, Biomedical Scientist) “Rewarding yet challenging at the same time. Helps with ongoing education and professional development for myself.” (Novice Supervisor, Clinician)

This study examines a large post-graduate medical student research project program from the perspective of the research project supervisors. Supervisors reported that students needed both generic skills and research-based skills to successfully complete the project. Across 3 years of the program, the students are expected to spend 320 h dedicated to their research project. Supervisors reported that having no protected time for research activities was a significant barrier to the successful completion of the project. Further support was requested for statistics, scientific writing and funding for projects. Importantly, prior research supervision experience affected the responses, where novice supervisors reported higher rates of project delays due to ethics review, data acquisition problems and unexpected project problems compared to experienced supervisors. Inexperienced supervisors also reported less access to supports, suggesting further support and training of novice supervisors would be of benefit.

The supervisor workforce in this study was mostly clinician researchers, followed by public health and epidemiology researchers and biomedical scientists. A smaller proportion of the supervisors oversaw medical education, bioinformatics, information technology or medical policy law or ethics projects. Thus, the project scope and supervisor research expertise varied, and many indicated they had multiple areas of expertise. This is in line with most medical degree scholarly programs which offer a wide scope of project experiences [ 2 , 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Most of the respondents identified as being experienced supervisors, a third had supervised some project models, and some had no prior research supervision experience. This is common across student research programs, where the role of project supervisor often requires no qualification other than being a researcher or being available, though it is known that the supervision role requires support [ 16 ]. This study also provided some insight into the motivations of the research supervisors, where the experienced supervisors felt the need to contribute to teaching, whereas the novice supervisors wanted to gain supervision skills.

An important finding of this study is that supervisors report that both generic and research skills are important for successful completion of MD Projects. Indeed many of the generic skills needed are also required by medical professionals, and such skills are now routinely included in many medical program curricula [ 19 ]. These skills include time management and organisation skills, taking initiative and acting independently, and effective communication skills which all contribute to the development of professionalism [ 20 ].

The major barriers to student success identified by supervisors are similar to those previously published [ 21 ] comprising the trio of time, funding and the student-supervisor relationship. The delivery of the MD Project, within the already busy medical school curriculum, was cited as one of the major barriers for student success in their projects. A recent realist review also concluded that research experience for medical students required protected time and adequate supervision to achieve scholarly outcomes [ 4 ]. Interestingly, MD Project supervisors reported that students had time to complete their projects, although a lack of dedicated time to conduct the project manifested in students adopting a stop-start approach to their projects, as they navigated the rest of the medical program content. This was very clear in the respondent reports regarding student communication, which describe many students as being proactive only as milestone assessment tasks approached. The progressive assessment schedule for the MD Project was well received by the supervisors, who found it useful to progress projects, though only half thought milestone assessments were useful to maintain momentum of the projects or to determine how their students were tracking within the cohort (Table 3 ). Traditional scientific research project assessments were used, including written and oral progress reports and a final written scientific report, which were all considered very useful in project progress towards completion.

Only 11% of the supervisors said they had all the resources they needed to run their project; this is a clear area for improvement. The supervisory role was not remunerated, there was no backfill for time taken, no project funds available and nearly all supervisors had busy and demanding research and/or clinical roles. Thus, the volunteer nature of the supervisor cohort is quite important, especially given that some of the usual paybacks of supervising students to do research are uncommon in this setting, e.g., generating publications, piloting projects or advancing parts of larger projects. Supervisors reported that academic support for students in statistics, research methods, scientific writing and ethics were lacking and that central support for these services would be welcome. Thus, to sustainably run a research program like this at scale, further central support for these activities needs to be provided.

Participants were from a variety of specialty areas, both clinical and non-clinical, and with varying degrees of research supervision experience. Notably some survey responses were significantly different according to the respondent’s previous supervision experience. This is in line with a recent report [ 22 ] and trends with prior supervision experience were further explored. Novice supervisors were significantly more likely to rate their students at the outset as being familiar with research methods and confident in approaching their project. This likely reflects the supervisor’s inexperience and is consistent with previous reports that interpreting student understanding is difficult for novices [ 23 ]. They also may have different pre-existing expectations of the research project process than the experienced supervisors [ 22 ]. Novice supervisors were significantly less likely to report that a dedicated time was needed for students to work on the project, and this is contrary to consistent evidence that protected research time is required for the success of these projects [ 20 ]. A further finding is that highly experienced supervisors were significantly less likely to suggest that student’s lack of prior research experience was a barrier to project progress, possibly as they had better support structures in place for their students, and better understanding of how to guide students in their research activities.

Further, novice supervisors were more likely to report significant project delays, due to unexpected problems, ethics review, and data acquisition delays. In addition, there was a significant trend in these delays with prior supervision experience, suggesting that mentoring or further support for new supervisors would be useful to bridge the gap. Moreover, there was a significant trend showing that students of novice supervisors had less access to support for scientific writing, expertise in research methods and preparation of ethics review applications, further revealing areas where increased training and support would be useful for novice supervisors.

Quality research supervision involves expertise of the supervisor in the research area, and a willingness to guide the student through the research project process [ 24 ]. Different models of supervision are likely to be required for different students and different project types [ 25 ]. Further, studies show that the student-supervisor relationship is largely dependent on how reliant the student is on their supervisor; thus, students who are more dependent may need a different approach to supervision than those who are independent [ 26 ]. This is consistent with the current findings that supervisors felt that the overall supervision experience varied widely. The ideal research environment for medical students has been reported to involve individual supervision with continuous feedback [ 8 ]. Notably, many MD Project supervisors felt that their feedback on student performance was only moderately well received, but the reasons for this are not clear. Compiling and delivering feedback to assist student progress is a complex process with several considerations including the emotional impact of receiving or giving written feedback; written feedback in the supervisory power dynamic; communicating written feedback; and the content and structure of written feedback [ 27 ]. These proficiencies are a further area for future training considerations. In addition to this, improving the supervisor experience would likely cultivate future supervision capacity and retention of experienced supervisors, which is an important consideration for the sustainability of a large MD Project Program.

Many research supervisors are not specifically trained in the pedagogy associated with supervision. Although specific training programs have become standard for higher degree supervisors [ 9 , 28 ], this is not the case for research supervision at the undergraduate or post-graduate coursework level, as in this program. Higher degree supervisor training programs cover topics like managing the relationship between student and supervisor, keeping roles and expectations clear, managing milestones and project progress. Other important considerations may be handling breakdowns in relationships, authorship, and research ethics issues [ 9 , 29 ]. All of these are relevant to the MD project supervision. In this study, supervision experience ranged from none to extensive, but supervisors were not required to have any supervision qualifications. Notably, inexperienced supervisors were less inclined to have a second supervisor or expert content advisor involved in supervising their student’s project, whereas experienced supervisors were more open to this option. This finding is in accord with the supervisor professional identity dilemma previously reported for both novice and more experienced supervisors [ 23 ].

Limitations

This cross-sectional study has limitations in that it is subject to self-report bias and the timing of the survey which took place at the end of the 2.5-year project risking the introduction of recall bias. The relatively low response rate (28%) reflects the participant cohort which includes busy clinicians and researchers [ 30 ].

In conclusion, research supervisors reported that both generic and research-related skills were important for research project success. Overall, supervisors considered that the program delivered on its objectives, and that the assessment tasks enabled project progress and skill acquisition. Protected research time, funding, and academic support, particularly for research methods and ethics, would improve the research project program. Supervisor perceptions differed depending on prior research supervision experience and suggest a targeted training program could be beneficial. This should be further investigated to inform future support provisions.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available, as per conditions of Ethics Committee approval, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Zimerman AL. Evidence-based medicine: a short history of a modern medical movement. Virtual Mentor. 2013;15(1):71–6.

Google Scholar

Green EP, Borkan JM, Pross SH, Adler SR, Nothnagle M, Parsonnet J, et al. Encouraging Scholarship: Medical School Programs to Promote Student Inquiry Beyond the Traditional Medical Curriculum. Acad Med. 2010;85(3):409–18.

Article Google Scholar

Chang Y, Ramnanan CJ. A review of literature on medical students and scholarly research: experiences, attitudes, and outcomes. Acad Med. 2015;90(8):1162–73.

Cornett M, Palermo C, Wallace MJ, Diug B, Ward B. A realist review of scholarly experiences in medical education. Med Educ. 2021;55(2):159–66.

Butler D. Translational research: Crossing the valley of death. Nature (London). 2008;453(7197):840–2.

Windsor J, Garrod T, Talley NJ, Tebbutt C, Churchill J, Farmer E, et al. The clinical academic workforce in Australia and New Zealand: report on the second binational summit to implement a sustainable training pathway. Intern Med J. 2017;47(4):394–9.

Wyngaarden JB. The clinical investigator as an endangered species. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(23):1254–9.

Moller R, Ponzer S, Shoshan M. Medical students’ perceptions of their learning environment during a mandatory research project. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:375–81.

Kiley M. Developments in research supervisor training: causes and responses. Studies in Higher Education (Dorchester-on-Thames). 2011;36(5):585–99.

Roberts LD, Seaman K. Students’ Experiences of Undergraduate Dissertation Supervision. Front Educ. 2018;3:109.

Hunt JE, Scicluna H, McNeil HP. Development and Evaluation of a Mandatory Research Experience in a Medical Education Program: The Independent Learning Project at UNSW. Med Sci Educ. 2011;21(1):78–85.

Devi V, Abraham RR, Adiga A, Ramnarayan K, Kamath A. Fostering research skills in undergraduate medical students through mentored students projects: example from an Indian medical school. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2010;8(31):294–8.

Mullan JR, Weston KM, Rich WC, McLennan PL. Investigating the impact of a research-based integrated curriculum on self-perceived research experiences of medical students in community placements: a pre- and post-test analysis of three student cohorts. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:161.

Cleland J, Engel N, Dunlop R, Kay C. Innovation in medical education: summer studentships. Clin Teach. 2010;7(1):47–52.

Weber R. Basic Content Analysis. Thousand Oaks, California1990. Available from: https://methods.sagepub.com/book/basic-content-analysis .

Uebel K, Iqbal MP, Carland J, Smith G, Islam MS, Shulruf B, et al. Factors determining medical students’ experience in an independent research year during the medical program. Med Sci Educ. 2021;31(4):1471–8.

Boninger M, Troen P, Green E, Borkan J, Lance-Jones C, Humphrey A. Implementation of a longitudinal mentored scholarly project: an approach at two medical schools. Acad Med. 2010;85(3):429–37.

Wood W, McCollum J, Kukreja P, Vetter IL, Morgan CJ, Hossein Zadeh Maleki A, et al. Graduate medical education scholarly activities initiatives: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):318.

Murdoch-Eaton D, Whittle S. Generic skills in medical education: developing the tools for successful lifelong learning. Med Educ. 2012;46(1):120–8.

Goldstein EA, Maestas RR, Fryer-Edwards K, Wenrich MD, Oelschlager A-MA, Baernstein A, et al. Professionalism in medical education: an institutional challenge. Acad Med. 2006;81(10):871–6.

Brew A, Mantai L. Academics’ perceptions of the challenges and barriers to implementing research-based experiences for undergraduates. Teach High Educ. 2017;22(5):551–68.

Möller R, Wallberg A, Shoshan M. Faculty perceptions of factors that indicate successful educational outcomes of medical students’ research projects: a focus group study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):519.

Vereijken MWC, van der Rijst RM, van Driel JH, Dekker FW. Novice supervisors’ practices and dilemmatic space in supervision of student research projects. Teach High Educ. 2018;23(4):522–42.

Cheung G, Friedman SH, Ng L, Cullum S. Supervising trainees in research: what does it take to be a scholarly project supervisor? Australas Psychiatr. 2018;26(2):214–9.

McCallin A, Nayar S. Postgraduate research supervision: a critical review of current practice. Teach High Educ. 2012;17(1):63–74.

Booi HK. Style and Quality in Research Supervision: The Supervisor Dependency Factor. High Educ. 1997;34(1):81–103.

Duncanson K, Schmidt D, Webster E. Giving and receiving written feedback on research reports: a narrative review and guidance for supervisors and students. Health Education in Practice: Journal of Research for Professional Learning; Vol 3, No 2. 2020.

Pearson M, Brew A. Research Training and Supervision Development. Studies Higher Educ (Dorchester-on-Thames). 2002;27(2):135–50.

Weston KM, Mullan JR, Hu W, Thomson C, Rich WC, Knight-Billington P, et al. Academic Guidance in Medical Student Research: How Well Do Supervisors and Students Understand the Ethics of Human Research? J Acad Ethics. 2016;14(2):87–102.

Cunningham CT, Quan H, Hemmelgarn B, Noseworthy T, Beck CA, Dixon E, et al. Exploring physician specialist response rates to web-based surveys. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2015;15(1):32.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Prof Michael Frommer and Prof David Tiller who were instrumental in the design, development, and implementation of the MD Project Program. Academic management for the MD Project team was provided by Clara Spencer, Anna Forte, Hannah Bath, Craig Purcell, Nicholas Olsen, Paniani Patu and Sally Middleton. The substantial support of research supervisors and coordinators of both the research project program and this survey is also acknowledged.

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Sydney Medical School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Joanne Hart, Jonathan Hakim, Rajneesh Kaur, Richmond Jeremy & David Bowen

School of Health Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Genevieve Coorey

Office of the Deputy Vice Chancellor (Education), University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Eszter Kalman

School of Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Rebekah Jenkin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Jonathan Hakim, Rebekah Jenkin, Eszter Kalman and David Bowen contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Jonathan Hakim and Joanne Hart. Data analyses were performed by Joanne Hart, Genevieve Coorey and Rajneesh Kaur. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Joanne Hart and all authors commented on subsequent versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Joanne Hart .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This research project was approved by the University of Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee, #2017/748. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from each participant. Participation was anonymous and submission of the online survey form was accepted as informed consent to be involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Hart, J., Hakim, J., Kaur, R. et al. Research supervisors’ views of barriers and enablers for research projects undertaken by medical students; a mixed methods evaluation of a post-graduate medical degree research project program. BMC Med Educ 22 , 370 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03429-0

Download citation

Received : 01 February 2022

Accepted : 27 April 2022

Published : 13 May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03429-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Medical research projects

- Student supervision

- Research supervisors

- Research supervision practice

- Research skills development

- Medical student projects

- Student thesis

- Scholarly research

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Training of Research Supervisors: Communities of Practice, Distance Supervision, and Holistic Strategies

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 31 October 2017

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Ronel Erwee 7

Part of the book series: University Development and Administration ((UDAA))

This chapter explores the evolution of supervisory training and contrasting approaches that universities engage in during the training of supervisors. It deals with the use of technology and supervisory communication with offshore or distance doctoral students, but also whether cultural differences between supervisors and students could affect their relationship. It notes examples of the development of an online research supervision toolkit as well as incorporating communities of practice. It presents a case study of a holistic view of supervisory training within a university research training framework. Recommendations for managing current challenges and future needs for research supervisory training are discussed.

- Research supervisors

- Research supervisory training

- Communities of practice for research supervisor

- Doctoral supervision

- Supervision at a distance

- Online research supervision toolkit

- Holistic research planning in universities

Ronel Erwee: deceased.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Albion, P.R. 2006. Building momentum in an online doctoral studies community. In Quality in postgraduate research 2006: Knowledge creation in testing times , ed. M. Kiley and G. Mullins, 87–96. Adelaide: The Centre for Educational Development and Academic Methods, The Australian National University.

Google Scholar

Albion, P., and R. Erwee. 2011. Preparing for doctoral supervision at a distance: Lessons from experience. In Research highlights in technology and teacher education 2011 , ed. C. Maddux, D. Gibson, B. Dodge, M. Koehler, P. Mishra, and C. Owens, 121–128. Chesapeake: Society for Information Technology and Teacher Education (SITE).

Arthur, E., E. McWilliam, R. Neuman, and C. Nicol. 2008. Framework for best practice in doctoral research education in Australia. Council of Australian Deans and Directors of Graduate Studies, October, pp 1–7.

Barnard-Brak, L., W.Y. Lan, and V.O. Paton. 2010. Profiles in self-regulated learning in the online learning environment. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning 11 (1): 61–79.

Benmore, A. 2014. Boundary management in doctoral supervision: How supervisors negotiate roles and role transitions throughout the supervisory journey. Studies in Higher Education 41 (7): 1251–1264.

Article Google Scholar

Blass, E., S. Bertone, J. Luca, C. Standing, R. Adams, H. Borland, R. Erwee, A. Jasman, K Tickle, and Q. Han. 2013. Developing a toolkit and framework to support new postgraduate research supervisors in emerging areas. Report to the Office of Teaching and Learning, Department of Industry, Innovation, Science, Research and Tertiary Education , Sydney. 1–81.

Boehe, D.M. 2016. Supervisory styles: A contingency framework. Studies in Higher Education 46 (3): 399–414.

Cater-Steel, A. 2009. Improving capability of research supervisors. Associate Fellowship LTSU report , University of Southern Queensland.

Chokkar, J.S., F.C. Brodbeck, and R.J. House. 2007. Culture and leadership across the world: The Globe book of in-depth studies of 25 societies . Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Erwee, R., and P. Albion. 2011. Preferences of supervisors and external doctoral students for new communication media. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour 16 (1): 30–39.

Erwee, R., P. Albion, R. Malan and H. van Rensburg. 2011. Dealing with doctoral students: Tips from the trenches. Postgraduate supervision: Research and practice conference , Centre for Higher and Adult Education, University of Stellenbosch, 19 April.

Erwee, R., P. Albion, and L. Van der Laan. 2013. Connectedness needs of doctoral students. In Outlooks and opportunities in blended and distance learning , ed. J. Willems, B. Tynan, and R. James. Hershey: IGI Global. Information Science Reference, Chapter 23, 316–329.

Guerin, C., H. Kerr, and I. Green. 2015. Supervision pedagogies: Narratives from the field. Teaching in Higher Education 20 (1): 107–118.

Hammond, J., K. Ryland, M. Tennant, and D. Boud. 2010. Building research supervision and training across Australian universities http://www.first.edu.au/public/ALTC/ALTC_building_supervisory_practice.pdf p8 .

Hugo, G., and A. Morris. 2010. Investigating the aging academic workforce: stocktake . University of Adelaide, Adelaide.

Jasman, A. 2012. From behind closed doors: Making the tacit explicit in research supervision practice. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour 17 (1): 28–41.

Lee, A. 2008. How are doctoral students supervised? Concepts of doctoral research supervision. In Facilitating formative feedback: An undervalued dimension of assessing doctoral students’ learning. ATN Assessment conference , ed. Van Rensburg, H., and P. Danaher, RMIT University, Melbourne.

Luca, J., and T. Wolski. 2013. Higher degree research training excellence: A good practice framework. Office of Learning and Teaching, Sydney. www.ddogs.edu.au or [email protected].

Malan, R., R. Erwee, H. Van Rensburg, and P. Danaher. 2012. Cultural diversity: Impact of the doctoral candidate-supervisor relationship. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour 17 (1): 1–14.

Maor, D., J.D. Ensor, and B.J. Fraser. 2015. Doctoral supervision in virtual spaces: A review of research of web-based tools to develop collaborative supervision. Higher Education Research and Development 35 (1): 172–188.

McCarthy, G. 2004. The case for coaching as an approach to addressing challenges in doctoral supervision. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour 17 (1): 15–27.

Nasiri, F., and F. Mafakheri. 2015. Postgraduate research supervision at a distance: A review of challenges and strategies. Studies in Higher Education 40 (10): 1962–1969.

Nkomo, S. 2015. Challenges for management and business education in a ‘developmental’ state: The case for South Africa. The Academy of Management Learning and Education 14 (2): 242–258.

Pervan, S., D. Blackman, T. Sloan, M. Wallace, A. Vocino, C. Byrne. 2016. Framing the socialisation process of the DBA candidate: what can universities offer and what should candidates bring?. Studies in Continuing Education 38: 299–317. http://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2015.1120191 .

Spiller, D., G. Byrnes, and B. Ferguson. 2013. Enhancing postgraduate supervision through a process of conversational enquiry. Higher Education Research and Development 32 (5): 833–845.

Stephens, S. 2014. The supervised as the supervisor. Education and Training 56 (6): 537–550.

Turner, G. 2015. Learning to supervise: Four journeys. Education and Teaching International 52 (1): 86–98.

Van Rensburg, H., and P. Danaher. 2009. Facilitating formative feedback: An undervalued dimension of assessing doctoral students’ learning. ATN Assessment conference, RMIT University, Melbourne.

Van Rensburg, H., R. Erwee, and R. Malan. 2015. Research supervisory training: An exploration of trends in supervisory experience, types of training and perceptions of training in Australian and South African cases’. Presented at the Postgraduate supervision: Research and practice conference, Centre for Higher and Adult Education, University of Stellenbosch, 24–26 Mar.

Wallace, M., C. Byrne, S. Pervan, A. Vocino, T. Sloan, and D. Blackman. 2015. A decade of change in Australian DBA landscape. Education and Training 57 (1). https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-07-2013-0096 .

Whinchester-Seeto, T., J. Homewood, J. Thorgesen, C. Jancenylk-Travewoger, C. Manathunga, A. Reid, and A. Holbrook. 2014. Doctoral supervision in a cross-cultural context: Issues affecting supervisors and candidates. Higher Education Research and Development 33 (1): 610–626.

White, T., and E. Coetzee. 2014. Postgraduate supervision: Email as an alternative. Africa Education Review 11 (4): 658–673.

Whitely, A.M. 2004. Preparing the supervisor and student for cross-cultural supervision. International Journal of Organisational Behaviour 17 (1): 422–430.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Toowoomba, QLD, Australia

Ronel Erwee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, Queensland, Australia

Tertiary Preparation Program, University of Southern Queensland Tertiary Preparation Program, Queensland, Queensland, Australia

Meredith Harmes

Open Access College Administration, Queensland, Australia

Marcus Harmes

Patrick Alan Danaher

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2018 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Erwee, R. (2018). Training of Research Supervisors: Communities of Practice, Distance Supervision, and Holistic Strategies. In: Erwee, R., Harmes, M., Harmes, M., Danaher, P. (eds) Postgraduate Education in Higher Education. University Development and Administration. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0468-1_36-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0468-1_36-1

Received : 28 June 2016

Accepted : 10 April 2017

Published : 31 October 2017

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-10-0468-1

Online ISBN : 978-981-10-0468-1

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search entire site

- Search for a course

- Browse study areas

Analytics and Data Science

- Data Science and Innovation

- Postgraduate Research Courses

- Business Research Programs

- Undergraduate Business Programs

- Entrepreneurship

- MBA Programs

- Postgraduate Business Programs

Communication

- Animation Production

- Business Consulting and Technology Implementation

- Digital and Social Media

- Media Arts and Production

- Media Business

- Media Practice and Industry

- Music and Sound Design

- Social and Political Sciences

- Strategic Communication

- Writing and Publishing

- Postgraduate Communication Research Degrees

Design, Architecture and Building

- Architecture

- Built Environment

- DAB Research

- Public Policy and Governance

- Secondary Education

- Education (Learning and Leadership)

- Learning Design

- Postgraduate Education Research Degrees

- Primary Education

Engineering

- Civil and Environmental

- Computer Systems and Software

- Engineering Management

- Mechanical and Mechatronic

- Systems and Operations

- Telecommunications

- Postgraduate Engineering courses

- Undergraduate Engineering courses

- Sport and Exercise

- Palliative Care

- Public Health

- Nursing (Undergraduate)

- Nursing (Postgraduate)

- Health (Postgraduate)

- Research and Honours

- Health Services Management

- Child and Family Health

- Women's and Children's Health

Health (GEM)

- Coursework Degrees

- Clinical Psychology

- Genetic Counselling

- Good Manufacturing Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Speech Pathology

- Research Degrees

Information Technology

- Business Analysis and Information Systems

- Computer Science, Data Analytics/Mining

- Games, Graphics and Multimedia

- IT Management and Leadership

- Networking and Security

- Software Development and Programming

- Systems Design and Analysis

- Web and Cloud Computing

- Postgraduate IT courses

- Postgraduate IT online courses

- Undergraduate Information Technology courses

- International Studies

- Criminology

- International Relations

- Postgraduate International Studies Research Degrees

- Sustainability and Environment

- Practical Legal Training

- Commercial and Business Law

- Juris Doctor

- Legal Studies

- Master of Laws

- Intellectual Property

- Migration Law and Practice

- Overseas Qualified Lawyers

- Postgraduate Law Programs

- Postgraduate Law Research

- Undergraduate Law Programs

- Life Sciences

- Mathematical and Physical Sciences

- Postgraduate Science Programs

- Science Research Programs

- Undergraduate Science Programs

Transdisciplinary Innovation

- Creative Intelligence and Innovation

- Diploma in Innovation

- Transdisciplinary Learning

- Postgraduate Research Degree

GRS supervisor development workshops

The Graduate Research School (GRS) offers a series of workshops to strengthen supervisors’ knowledge, skills, and tools in best supervisory practices.

As an HDR supervisor, you will have the privilege of watching your students grow into independent researchers who make a meaningful contribution to knowledge. You will also become part of a community of UTS staff who are committed to developing the next generation of professionals and researchers who can lead our global society.

In order to supervise HDR students, you must complete the initial supervision module “ Graduate research supervision at UTS ” (opens link to NEO). Principal or co-supervisors must also complete two additional training workshops.

Foundations

- Graduate research supervision at UTS This online module is an introduction to graduate research supervision at UTS. It is an overview of the global, Australian, and UTS contexts for graduate research education. In addition to providing an important summary of UTS policies and guidelines, it also offers an entry point into understanding the foundations of effective HDR supervision practices. These practices must take into account the purpose of the contemporary HDR degree. The module is a mandatory requirement to register as an HDR supervisor.

Research questions and beginning writing The focus of this workshop is on working with graduate research students who are in their early stages of candidature. In particular, it looks at supporting students as they formulate research questions/problems, pursue initial research processes and begin writing—all of which need to be contextualised within the student’s specific discipline/field of practice. The module foregrounds how to help students get started and get writing, and how to give guidance and effective feedback on their work. 23 April, 10:00am - 12:00pm

Past themes and topics

Building strong supervisory practices.

- Supervising distance and part-time research students Research doesn't always take place on campus. Whether a student is undertaking field research, completing a PhD by distance mode , or simply studying part-time, students who aren't on campus full-time can benefit from different approaches to supervision. This session focuses on how to maintain good communication and progress with distance and part-time students, as well as supporting their ongoing wellbeing and development as professional researchers.

- Holding challenging conversations Research supervision is a multiyear relationship that encompasses a variety of responsibilities, milestones, and potential approaches. Some conflict is likely, and not inherently a problem: what makes conflicts healthy or harmful depends on how they're managed. This workshop focuses on how to have challenging conversations in a way that helps produce resolution rather than resentment.

- Working with graduate research students This session considers ways of working as a supervisor or member of a supervisory panel for graduate research students. It explores a range of supervisory styles and how these develop different kinds of relationships with students. Topics under consideration include negotiating expectations and ways of working, collaboratively setting goals and developing research plans, working with students from diverse contexts, managing problems, and ensuring graduate research study plans assist students in successfully moving through the stages of assessment.

- Collaborative, cross-disciplinary supervision This session begins with an exploration of conceptions of cross-disciplinary research. It focuses on what this means for graduate research supervision and explores how supervisors can develop productive collaborative ways of working with one another and with students across disciplines and/or fields of practice. The session introduces ideas and strategies for working in a research environment where different theories are brought together and knowledge is being generated from different disciplinary frames using new methods and insights. It emphasises the importance of articulating what counts as quality research in cross-disciplinary work.

- Mentoring and co-supervision This session introduces a number of tools and practices that support a productive mentoring relationship between established and earlier career supervisors. It focuses on developing ways of working together as supervisors of graduate research students, including negotiating a mentoring agreement and exploring how roles might change during the course of a candidature.

- Understanding industry PhD programs Industry-embedded PhDs can be a powerful mechanism to build research partnerships, drive collaboration, and contribute to real-world impact. This workshop offers an overview of the why, what, and how of industry PhDs, including how to make existing programs like the National Industry PhD Program and UTS's Industry Doctorate Program work for you.

Supporting the thesis journey

- Research questions and beginning writing The focus of this session is on working with graduate research students who are in their early stages of candidature. In particular, it looks at supporting students as they formulate research questions/problems, pursue initial research processes and begin writing—all of which need to be contextualised within the student’s specific discipline/field of practice. The session foregrounds how to help students get started and get writing, and how to give guidance and effective feedback on their work.

- Supporting progress: managing the graduate research journey This session supports the ongoing relationship between supervisors and graduate research students who have completed Stage One of their candidature. It explores ways of ensuring that supervisory relationships remain positive and productive. Participants will consider a range of supervisory styles and discuss how these may be relevant to advanced candidates. Topics under consideration include (re)negotiating expectations and ways of working, publishing, managing problems, ethical practice and ensuring graduate research study plans assist students in achieving the goals set out in the final stage of their plan.

- Writing up the thesis The focus of this session is on working with graduate research students who are in their final stage of candidature. In particular, it is aimed at supporting students as they complete and submit their theses for examination, in the staged and organized ways that are appropriate for their discipline/field of practice. This involves extending students’ skills in conceptualising and categorising relevant literature; analysing, presenting and discussing data; and writing a well-structured, cohesive thesis.

- So you want to do a NTRO? Not all scholarly research turns into a journal article. A software algorithm, architectural design, film, or article of clothing could all be Non-Traditional Research Outputs (NTROs). UTS PhDs can integrate NTROs into their research journey, part of the distinctive way UTS supports our students to explore issues and problems that are meaningful to them. This session covers the value and impact of NTROs, how to evaluate their quality, and how to incorporate them into HDR research.

Fostering a healthy and inclusive research culture

- Managing for success: supporting HDR mental health and wellbeing This session focuses on understanding mental health and the role it plays in student success. Topics under consideration include the foundations of mental health, warning signs of stress and mental health concerns, and avoiding common pitfalls in mental health conversations with students. Supervisors will also learn about the resources available to support student wellbeing and how to implement strategies of self-care.

Neurodiversity ally and accessibility training Ensuring that our research culture embraces diversity is critical to our excellence, creativity, and the future innovative capacity we are developing through our research training. This highly interactive workshop provides an immersive experience of Neurodiversity inclusion in a higher education context and equips participants to work confidently in Neurodiverse spaces in the future.

Supervising Indigenous Australian HDR students for success This session will provide supervisors of Indigenous research students with various points to consider when supervising. This workshop has three key areas of focus: the HDR student, the research and support.

Supervising international research students This session explores ways of working with international students, and the role research supervisors can play in supporting their effective acculturation and learning as a graduate research student at UTS. The workshop focuses on intercultural communication skills as well as ideas and strategies for working with students and colleagues from diverse backgrounds.

Thinking beyond the thesis

- Strategic recruitment and admissions The first step on the journey to HDR student success is a thoughtful recruitment and admissions process. This session will cover how to approach student recruitment and admissions proactively, strategically, and effectively—helping you maximise the likelihood of attracting and selecting the best candidates.

- Publishing for (and with) HDRs Scholarly publication is a critical part of an HDR student’s intellectual journey, development of a professional profile, and enculturation into a community of scholars. Yet expectations and norms around co-authorship can vary widely across disciplines and cultures, leading to interpersonal and professional challenges if not dealt with proactively. Incorporating a variety of disciplinary perspectives, this workshop will consider the practical, ethical, and intellectual property foundations of successful co-publishing.

- Working on careers: around and beyond the thesis This session focuses on working with graduate research students in developing their careers. It explores relevant trends in the future of work and the variety of ways HDR students create impactful careers. Participants will learn how to better support students in planning the next steps in their careers, with a particular emphasis on engaging with scholarly and professional research communities, establishing relationships and networks, communicating their research through scholarly and public channels, and leveraging UTS Careers resources.

- Building industry engagement with research students Supporting research students to undertake industry engagement has a number of benefits for all parties. Supervisors build research partnerships and develop a track record for research funding programs. Students develop multifaceted research thinking, enhance networks, and strengthen professional skills. This workshop focuses on effectively incorporating students into research partnerships and supervising them to ensure they, their thesis, and the partnership are all successful.

UTS acknowledges the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation, the Boorooberongal people of the Dharug Nation, the Bidiagal people and the Gamaygal people, upon whose ancestral lands our university stands. We would also like to pay respect to the Elders both past and present, acknowledging them as the traditional custodians of knowledge for these lands.

- The Importance of Training

- Challenges Supervisors Face

Preparing New Supervisors

- How to Transition Employees

Are Your Supervisors Effective?

- Crucial Skills for Supervisors

Developing a Plan

The Ultimate Guide to Training Your Supervisors and Managers

This ultimate guide shares how training your supervisors and managers will help them overcome challenges, motivate those around them, and be more effective in their roles.

Don’t have time to read the entire ultimate guide right now?

We are happy to email you the complete guide so you can read it when it’s convenient for you.

Introduction

Research shows that over half of new supervisors and managers receive little or no training before assuming their new roles.