Coaching in Sports: Implications for Researchers and Coaches

- First Online: 19 March 2021

Cite this chapter

- Humberto M. Carvalho 3 &

- Carlos E. Gonçalves 4

1174 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Sports Coaching research continues to develop, although with a narrow spread of publication, mainly within Sports Psychology, and small impact across Sports Science journals. Nevertheless, Sports Coaching research potentially investigates an array of basic and applied research questions. Hence, there is an opportunity for improvement. Moreover, there is an increased awareness in several scientific areas, including Sports Science, about several problems pertaining to design, transparency, replicability, and trust of research practices. Particularly in Sports Coaching research, these problems include limited or inadequate validation of surrogate outcomes and lack of multidisciplinary designs, lack of longitudinal and replication studies, inappropriate data analysis and reporting, limited reporting of null or trivial results, and insufficient scientific transparency. In this chapter, we initially discuss the trends of publication in Sports Coaching, highlighting research problems as they pertain to their treatment in other disciplines, namely psychology. Lastly, we illustrate an example applied to Sport Coaching research with a repeated measures design and an interdisciplinary approach as a recommendation to promote transparency, replicability, and trust in Sports Coach research.

- Sports coaching

- Scholarly publishing

- Open science

- Reproducibility

- Coaching practice

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Amrhein, V., & Greenland, S. (2018). Remove, rather than redefine, statistical significance. Nature Human Behaviour, 2 (1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0224-0

Article Google Scholar

Amrhein, V., Greenland, S., & McShane, B. (2019a). Scientists rise up against statistical significance. Nature, 567 (7748), 305–307. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-00857-9

Amrhein, V., Greenland, S., & McShane, B. B. (2019b). Statistical significance gives bias a free pass. European Journal of Clinical Investigation, 49 (12), e13176. https://doi.org/10.1111/eci.13176

Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11 (4), 959–975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

Bartell, S. M. (2019). Understanding and mitigating the replication crisis, for environmental epidemiologists. Current Environmental Health Reports, 6 (1), 8–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40572-019-0225-4

Batterham, A. M., & Hopkins, W. G. (2006). Making meaningful inferences about magnitudes. International Journal of Sports Physiology Performance, 1 (1), 50–57.

Begley, C. G., & Ioannidis, J. P. (2015). Reproducibility in science. Circulation Research, 116 (1), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303819

Bürkner, P.-C. (2017). brms: An R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. Journal of Statistical Software, 80 , 1–28.

Burwitz, L., Moore, P. M., & Wilkinson, D. M. (1994). Future directions for performance-related sports science research: An interdisciplinary approach. Journal of Sports Science, 12 (1), 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419408732159

Caldwell, A. R., Vigotsky, A. D., Tenan, M. S., Radel, R., Mellor, D. T., Kreutzer, A., … Boisgontier, M. P. (2020). Moving sport and exercise science forward: A call for the adoption of more transparent research practices. Sports Medicine, 50 (3), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01227-1

Carpenter, B., Gelman, A., Hoffman, M. D., Lee, D., Goodrich, B., Betancourt, M., … Riddell, A. (2017). Stan: A probabilistic programming language. Journal of Statistical Software, 76 (1), 32. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v076.i01

Chambers, C. (2017). The seven deadly sins of psychology: A manifesto for reforming the culture of scientific practice . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Gelman, A., & Geurts, H. M. (2017). The statistical crisis in science: How is it relevant to clinical neuropsychology? Clinical Neuropsychology, 31 (6–7), 1000–1014. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2016.1277557

Gelman, A., & Shalizi, C. R. (2013). Philosophy and the practice of Bayesian statistics. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 66 (1), 8–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8317.2011.02037.x

Gilbert, W. D., & Trudel, P. (2004). Analysis of coaching science research published from 1970–2001. Research Quarterly for Exercise & Sport, 75 (4), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701367.2004.10609172

Gonçalves, C. E., Carvalho, H. M., & Catarino, L. M. (2018). Body in movement: Better measurements for better coaching. In S. Pill (Ed.), Perspectives on athlete-centered coaching (pp. 116–126). Abingdon: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Grecic, D., & Collins, D. (2013). The epistemological chain: Practical applications in sports. Quest, 65 (2), 151–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2013.773525

Griffo, J. M., Jensen, M., Anthony, C. C., Baghurst, T., & Kulinna, P. H. (2019). A decade of research literature in sport coaching (2005–2015). International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 14 (2), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747954118825058

Halperin, I., Vigotsky, A. D., Foster, C., & Pyne, D. B. (2018). Strengthening the practice of exercise and sport-science research. International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance, 13 (2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijspp.2017-0322

Jacobs, F., Claringbould, I., & Knoppers, A. (2016). Becoming a ‘good coach’. Sport, Education and Society, 21 (3), 411–430. https://doi.org/10.1080/13573322.2014.927756

Kennedy, L., & Gelman, A. (2020). Know your population and know your model: Using model-based regression and poststratification to generalize findings beyond the observed sample. ArXiv e-prints, 1906.11323 (1906.11323 [stat.AP]).

Knudson, D. (2017). Confidence crisis of results in biomechanics research. Sports Biomechanics, 16 (4), 425–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/14763141.2016.1246603

Lee, M. D., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2013). Bayesian cognitive modeling: A practical course . Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Leek, J. T., & Peng, R. D. (2015). Opinion: Reproducible research can still be wrong: Adopting a prevention approach. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 112 (6), 1645. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1421412111

McElreath, R. (2015). Statistical rethinking: A Bayesian course with examples in R and Stan . Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC Press.

McShane, B. B., Gal, D., Gelman, A., Robert, C., & Tackett, J. L. (2019). Abandon statistical significance. The American Statistician, 73 (suppl 1), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2018.1527253

Open Science Collaboration. (2015). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science, 349 (6251), aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Pashler, H., & Wagenmakers, E. J. (2012). Editors’ introduction to the special section on replicability in psychological science: A crisis of confidence? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 7 (6), 528–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612465253

Piggott, B., Muller, S., Chivers, P., Papaluca, C., & Hoyne, G. (2018). Is sports science answering the call for interdisciplinary research? A systematic review. European Journal Sport Science, 19 (2), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2018.1508506

Powers, S. M., & Hampton, S. E. (2019). Open science, reproducibility, and transparency in ecology. Ecological Applications, 29 (1), e01822. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.1822

R Core Team. (2018). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/

Sainani, K. L. (2018). The problem with “Magnitude-Based Inference”. Medicine Science Sports Exercise, 50 (10), 2166–2176. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001645

Schweizer, G., & Furley, P. (2016). Reproducible research in sport and exercise psychology: The role of sample sizes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 23 , 114–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.11.005

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychology Science, 22 (11), 1359–1366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611417632

Welsh, A. H., & Knight, E. J. (2015). “Magnitude-based inference”: A statistical review. Medicine Science Sports Exercise, 47 (4), 874–884. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000451

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Federal University of Santa Catarina, Florianópolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil

Humberto M. Carvalho

University of Coimbra, Estádio Universitário de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Carlos E. Gonçalves

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Humberto M. Carvalho .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Life Quality Research Centre, University Institute of Maia, Maia, Portugal

Rui Resende

School of Psychology, University of Minho, Braga, Portugal

A. Rui Gomes

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Carvalho, H.M., Gonçalves, C.E. (2020). Coaching in Sports: Implications for Researchers and Coaches. In: Resende, R., Gomes, A.R. (eds) Coaching for Human Development and Performance in Sports. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63912-9_22

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-63912-9_22

Published : 19 March 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-63911-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-63912-9

eBook Packages : Behavioral Science and Psychology Behavioral Science and Psychology (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Sign in to save searches and organize your favorite content.

- Not registered? Sign up

Recently viewed (0)

- Save Search

International Sport Coaching Journal

An Official Journal of the International Council for Coaching Excellence (ICCE)

ISCJ launched in replacement of the Journal of Coaching Education

Indexed in: Web of Science, Scopus, ProQuest, EBSCOhost, Google Scholar

Print ISSN: 2328-918X Online ISSN: 2328-9198

- Get eTOC Alerts

- Get New Article Alerts

- Latest Issue TOC RSS

- Get New Article RSS

Volume 11 (2024): Issue 1 (Jan 2024)

ISCJ is a non-proprietary venture of the International Council for Coaching Excellence (ICCE) and is published by Human Kinetics. It was launched in 2014 as volume 1, replacing the Journal of Coaching Education ( JCE ), for which there were six volumes published. To view JCE content, click here .

ISCJ publishes three times per year: January, May, and September.

The mission of the International Sport Coaching Journal ( ISCJ ) is to advance the research and development of sport coaching world-wide. This mission is pursued through a specific focus on the practice and process of coaching, with consideration also given to the many factors that influence coaching. Thus, ISCJ publishes peer-reviewed scientific research studies and articles about practical advances about, with, and for coaches.

- Ethics Policy

Duties of Editors

Editors are the stewards of journals. Most Editors provide direction for the journal and build a strong management team. They must consider and balance the interests of many constituents, including readers, authors, staff, publishers, and editorial board members. Editors have a responsibility to ensure an efficient, fair, and timely review process of manuscripts submitted for publication and to establish and maintain high standards of technical and professional quality.

An Editor's decision to accept or reject a paper for publication should be based on the paper’s importance, originality, and clarity, and the study’s relevance to the remit of the journal. Consideration should be given without regard to race, religion, ethnic origin, gender, seniority, citizenship, professional association, institutional affiliation, or political philosophy of the author(s).

All original studies should be peer reviewed before publication, taking into full account possible bias due to related or conflicting interests. This requires that the Editor seek advice from Associate Editors or others who are experts in a specific area and will send manuscripts submitted for publication to reviewers chosen for their expertise and good judgment to referee the quality and reliability of manuscripts. Manuscripts may be rejected without review if considered inappropriate for the journal.

Editors must treat all submitted papers as confidential. The Editor and editorial staff shall disclose no information about a manuscript under consideration to anyone other than those from whom professional advice regarding the publication of the manuscript is sought. The Editors or editorial staff shall not release the names of reviewers.

Editors should consider manuscripts submitted for publication with all reasonable speed. Authors should be periodically informed of the status of the review process. In cases where reasonable speed cannot be accomplished because of unforeseen circumstances, the Editor has an obligation to withdraw himself/herself from the process in a timely manner to avoid unduly affecting the author’s pursuit of publication.

Where misconduct is suspected, the Editor must write to the authors first before contacting the head of the institution concerned.

Editors should ensure that the author submission guidelines for the journal specify that manuscripts must not be submitted to another journal at the same time. Guidelines should also outline the review process, including matters of confidentiality and time.

Editors transmit to Human Kinetics (specifically, the journal’s managing editor) the manuscripts accepted for publication approximately three months ahead of the publication date.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest arise when Editors have interests that are not fully apparent and that may influence their judgments on what is published.

Editors should avoid situations of real or perceived conflicts of interest, including, but not limited to, handling papers from present and former students, from colleagues with whom the Editor has recently collaborated, and from those in the same institution.

Editors should disclose relevant conflicts of interest (of their own or those of the teams, editorial boards, managers, or publishers) to their readers, authors, and reviewers.

Peer Review

Peer reviewers are external experts chosen by Editors to provide written opinions, with the aim of improving the works submitted for publication.

Suggestions from authors as to who might act as a reviewer are often useful, but there should be no obligation for Editors to use those suggested.

Editors and expert reviewers must maintain the duty of confidentiality in the assessment of a manuscript, and this extends to reviewers’ colleagues who give opinions on specific sections.

The submitted manuscript should not be retained or copied.

Editors should require that reviewers provide speedy, accurate, courteous, unbiased, and justifiable reports.

If reviewers suspect misconduct, they should write in confidence to the Editor.

Dealing With Misconduct

The general principle confirming misconduct is the intention to cause others to regard as true that which is not true. The examination of misconduct must, therefore, focus not only on the particular act or omission, but also on the intention of the researcher or author.

Editors should be alert to possible cases of plagiarism, duplication of previous published work, falsified data, misappropriation of intellectual property, duplicate submission of manuscripts, inappropriate attribution, or incorrect co-author listing.

In cases of other misconduct, such as redundant publication, deception over authorship, or failure to declare conflict of interest, Editors may judge what is necessary in regard to involving authors’ employers. Authors should be given the opportunity to respond to any charge of minor misconduct.

The following sanctions are ranked in approximate increasing order of severity:

- A letter of explanation to the authors, where there appears to be a genuine misunderstanding of principles.

- A letter of reprimand and warning as to future conduct.

- A formal letter to the relevant head of the institution or funding body.

- Refusal to accept future submissions from the individual, unit, or institution responsible for the misconduct, for a stated period.

- Formal withdrawal or retraction of the paper from the scientific literature, informing other editors and the indexing authorities.

Bettina Callary Cape Breton University, Canada

Editors Emeriti

Pat Duffy (2014) Wade Gilbert (2014–2019)

Associate Editors

Gordon Bloom McGill University, Canada

Brian Gearity University of Denver, USA

Andrew Gillham Sanford Sports Science Institute, USA

Steven Rynne University of Queensland, Australia

Digest Editors

Ian Cowburn Leeds Beckett University, UK

Tom Mitchell Leeds Beckett University, UK

Editorial Board

Andrew Bennie, Western Sydney University, Australia

Marte Bentzen, Norwegian School of Sport Sciences, Norway

Diane Culver, University of Ottawa, Canada

Chris Cushion, Loughborough University, UK

Louise Davis, Umeå University, Sweden

Lea-Cathrin Dohme, Cardiff Metropolitan University, UK

Larissa Galatti, University of Campinas, Brazil

Lori Gano-Overway, James Madison University, USA

Sophia Jowett, Loughborough University, UK

Clayton Kuklick, University of Denver, USA

Koon Teck Koh, National Instit. of Education, Singapore

Nicole LaVoi, University of Minnesota, USA

Michel Milistetd, Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil

Lee Nelson, Edge Hill University, UK

Julian North, Leeds Beckett University, UK

Donna O'Connor, University of Sydney, Australia

Scott Rathwell, University of Lethbridge, Canada

Fernando Santos, Polytechnic Institute of Porto and Polytechnic Institute of Viana do Castelo, Portugal

Anna Stodter, Leeds Beckett University, UK

Rob Townsend, University of Waikato, New Zealand

Pete Van Mullem, Lewis-Clark State College, USA

Amy Whitehead, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

Mariya Yukhymenko, California State University, Fresno, USA

ICCE Research Committee

Kristen Dieffenbach, West Virginia University, USA (co-chair)

Christine Nash, University of Edinburgh, UK (co-chair)

Torsten Buhre, Mälmo University, Sweden

Ntwanano Alliance Kubayi, Tshwane University of Technology, South Africa

Gethin Thomas, Cardiff Metropolitan University, UK

Don Vinson, University of Worcester, UK

Bettina Callary, Cape Breton University, Canada (ISCJ member)

Sergio Lara-Bercial, Leeds Beckett University, UK (ICCE appointed member)

Social Media Manager Kath O’Brien, Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Human Kinetics Staff Marielena Morgan, Journals Managing Editor

Prior to submission, please carefully read and follow the submission guidelines detailed below. Authors must submit their manuscripts through the journal’s ScholarOne online submission system. To submit, click the button below:

Page Content

Authorship guidelines, open access, manuscript types, cover letters, author biographies, editorial decisions, manuscript format, manuscript review, desk rejection policy, submit a manuscript, special issue guidelines, additional resources.

- Open Access Resource Center

- Figure Guideline Examples

- Copyright and Permissions for Authors

- Editor and Reviewer Guidelines

The Journals Division at Human Kinetics adheres to the criteria for authorship as outlined by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors*:

Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content. Authorship credit should be based only on substantial contributions to:

a. Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND b. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND c. Final approval of the version to be published; AND d. Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conditions a, b, c, and d must all be met. Individuals who do not meet the above criteria may be listed in the acknowledgments section of the manuscript. * http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authors-and-contributors.html

Authors who use artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technologies (such as Large Language Models [LLMs], chatbots, or image creators) in their work must indicate how they were used in the cover letter and the work itself. These technologies cannot be listed as authors as they are unable to meet all the conditions above, particularly agreeing to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Human Kinetics is pleased to allow our authors the option of having their articles published Open Access. In order for an article to be published Open Access, authors must complete and return the Request for Open Access form and provide payment for this option. To learn more and request Open Access, click here .

Manuscript Guidelines

All Human Kinetics journals require that authors follow our manuscript guidelines in regards to use of copyrighted material, human and animal rights, and conflicts of interest as specified in the following link: https://journals.humankinetics.com/page/author/authors

The International Sport Coaching Journal ( ISCJ ) is a peer-reviewed journal that publishes both Original Research studies and papers on Practical Advances in coaching. These manuscript types are described below.

Original Research

Original, peer-reviewed scientific research is intended to develop and innovate sport coaching world-wide. Manuscripts should be formatted with a review of relevant literature and theoretical frameworks to rationalize the purpose of the study followed by an explanation of the methodology, sample/participants, methods (including data collection, data analysis, research ethics), results, and discussion/implications. A variety of research designs are welcomed, though manuscripts should not exceed 35 double-spaced pages (including abstract, references, tables, and figures).

Practical Advances

These manuscripts include practical and applied perspectives on coaching and coaching-related topics. These manuscripts may focus on best practices of specific documented efforts, ideas, or evidence-based guidelines that can be used to improve coaching. They may focus on well-reasoned and effectively articulated insights and commentaries intended to stimulate thought and prompt open dialogue about coaching while (potentially) making contributions to new lines of study in coaching. Perspectives of coaching and coach education in different countries and cultures are also welcomed with an in-depth look at the sport coaching organizations, systems, and key features that define coaching in that part of the world. While adopting an applied orientation, these papers should still be written in an academic style that includes citations as well as other applied evidence to support and develop ideas. Papers that are Practical Advances in the field will typically be between 15–25 double-spaced pages (including abstract, references, tables, and figures). Practical Advances encompasses ISCJ legacy article types of Best Practices, Insights, and Coaching In.

In preparing manuscripts for publication in ISCJ , authors should use British spelling and follow the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed., 2020). Writing should be concise and direct. Avoid unnecessary jargon and abbreviations, but use an acronym or abbreviation if the spelled-out version of a term is cumbersome. Avoid abbreviations in the title. Formats of numbers and measurement units, and all other style matters, including capitalization, punctuation, references, and citations, must follow the APA Publication Manual .

Authors should provide 2–3 key points that describe the novel results or highlights of their research as a separate document. The key points are intended for a general audience, no more than 30 words, and in sentence format.

Upon submission, authors must upload a separate cover letter that lists (1) the title of the manuscript, (2) the date of submission, and (3) the full names of all the authors, their institutional or corporate affiliations, and their e-mail addresses. In addition to this essential information, the cover letter should be composed as described on pp. 382–383 of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed., 2020), including clear statements pertaining to potential fragmented publication, authorship, and other ethical considerations.

Upon submission, authors must include a separate Word file that provides biographies for all authors to be included in the final published version of the paper. Biographies should include name, rank, department, institution, and a brief statement about research expertise in 50–75 words.

Submissions that are rejected (i.e., that do not receive a minor or major-revision decision and invitation to resubmit) should not be resubmitted without editor invitation to ISCJ per the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed., 2020, p. 381), which reads that any manuscript "that has been rejected by a journal may not be revised and resubmitted to that same journal".

All manuscripts must be written in English, with attention to concise language, a logical structure and flow of information, and correct grammar. We appreciate that some of our authors do not speak English as their first language and may need assistance to reach the standards required by the journal. In addition, some younger authors may not be experienced in scientific writing styles. Since manuscripts that fail to meet the journal’s writing standards will not be sent out for review, such authors should ensure that they seek assistance from native English speakers and/or experienced colleagues prior to submitting their paper. Many journals acknowledge the existence of companies that offer professional editing services. Use of an editorial service is at the discretion and cost of the authors and will not guarantee acceptance for publication in ISCJ. An example of such services can be found at https://www.aje.com/ . This information does not constitute endorsement of this professional editing service.

The manuscript must be submitted as a Microsoft Word document. Other file formats, including PDF documents, are not accepted for the main (text) document. The manuscript should contain no clues as to author identity, such as acknowledgments, institutional information, and mention of a specific city. Thus, information that might identify the author(s) should be omitted or highlighted in black. The first page of the manuscript should include only the title of the manuscript and date of submission. All manuscripts must include an abstract of 150−200 words and three to six keywords chosen from terms not used in the manuscript title. Line numbers should be embedded in the left margin to facilitate the review process. For studies involving humans, the participants section must include a statement certifying that the study received institutional approval and that the participants’ informed consent was obtained. Manuscripts should not exceed the page length mentioned for each article type above.

Figures and Photos

If figures are included, each figure must be numbered in consecutive numerical order. A figure should have a caption that is brief and self-explanatory, and that defines all nonstandard abbreviations used in the figure. Captions must be listed separately, on a page by themselves; however, each figure must be clearly identified (numbered), preferably as part of its filename. Artwork should be professional in appearance and have clean, crisp lines. Hand drawing and hand lettering are not acceptable. Figures may use color. Shades of gray do not reproduce well and should not be used in charts and figures. Instead, stripe patterns, stippling, or solids (black or white) are good choices for shading. Line art should be saved at a resolution of 600 dots per inch (dpi) in JPEG or TIFF format. Photographic images can be submitted if they are saved in JPEG or TIFF format at a resolution of 300 dpi. If photos are used, they should be black and white, clear, and show good contrast. Any figures or photos from a source not original to the author must be accompanied by a statement from the copyright holder(s) giving the author permission to publish it; the source and copyright holder must be credited in the manuscript. See additional figure guidelines here .

When tabular material is necessary, it should not duplicate the text. Tables must be formatted using Microsoft Word’s table-building functions. (Using spaces or tabs in your table creates problems when the table is typeset and may result in errors). Tables should be single-spaced on separate pages and include their brief titles. Explanatory notes are to be presented in footnotes, below the table. The size and complexity of a table should be determined with consideration for its legibility and ability to fit the printed page.

Video Clips

Short video clips may be submitted to illustrate your manuscript. Files may be submitted through ScholarOne for review as part of the manuscript; each digital video file should be designated and uploaded as a “supplementary file,” and should be no larger than 15–20 MB (or 5–10 seconds, depending on compression). Video should be submitted in either .WMV or QuickTime (.mov) format with a standard frame size of 320 × 240 pixels and a frame rate of 30 frames per second. You also should indicate in the cover letter accompanying your submission that you have submitted a video file.

Digital material from a source not original to the author must be accompanied by a statement from the copyright holder giving the author permission to publish it; the source and copyright holder must be credited in the manuscript. Human Kinetics will inspect all video submissions for quality and technical specifications, and we reserve the right to reject any video submission that does not meet quality standards and specifications.

All manuscripts are evaluated via masked review and are reviewed by an editorial board member and at least one other reviewer. Submissions will be judged on the basis of the manuscript’s interest to the readership, theoretical and empirical contribution, adherence to accepted scientific principles and methods, and clarity and conciseness of writing. There are no page charges to authors. Manuscripts may not be submitted to another journal at the same time. Authors of manuscripts that are accepted for publication must transfer copyright to Human Kinetics, Inc. Exceptions to this copyright transfer rule will be made for government employees. Additional exceptions may be made on a case-by-case basis.

Before full review, submissions are examined at the editorial level. If the Editor and an Editorial Board Member believe the submission has extensive flaws or is inconsistent with the mission and focus of the journal, the manuscript may receive a desk reject decision.

Authors should submit manuscripts electronically as a Microsoft Word document via the ISCJ ScholarOne site (see submit button at the top of this page). ScholarOne will manage the electronic transfer of ISCJ manuscripts throughout the manuscript review process, providing step-by-step instructions. Problems encountered on the ScholarOne site can be resolved by choosing “Help” in the upper right corner of the screen.

Please review the APA checklist for manuscript submission before submitting your manuscript. Authors of accepted manuscripts must obtain and provide the managing editor all necessary permissions for reproduced figures, pictures, or other copyrighted work prior to publication. The authors also will need to complete and sign the copyright agreement, which will be provided to authors.

Special issue topics need to be diverse and inclusive of different perspectives; the topic itself should be resonating with coaching researchers at a particular time for a particular reason. The following guidelines are intended to help prepare a special issue proposal for ISCJ . In 4 pages or less, the proposal needs to address the following questions using the headings provided. Please send your completed proposal to Editor Bettina Callary at [email protected] .

1. Synopsis

In 150 words or less, what is your special issue about? Be sure to include its main themes and objectives.

2. Rationale

What are you proposing to do differently/more innovatively/better than has already been done on the topic (in ISCJ specifically, as well as in the field more generally)? Why is now the time for a special issue on this topic? Why is ISCJ the most appropriate venue for this topic? List up to five articles recently published on the topic that show breadth of scope and authorship in the topic?

3. Outline of Special Issue

How will each type of ISCJ paper (Original Research, Practical Advances) be integrated into the special issue? How many papers do you envision for the special issue? Names of authors who will be invited to submit papers, and paper topics? A list of up to 20 individuals with expertise in the topic who the special issue editors could recruit to act as reviewers?

4. Qualifications

Are you proposing to serve as Guest Editor for this special issue? If so, please provide a copy of your vitae with the proposal. If not, do you have suggestions for a potential Guest Editor?

5. Timeline

Given that it takes approximately 12 months to complete a special issue, please provide a detailed timeline including estimated dates or time frames for the following steps: Call for papers Submission deadline Review process (averages 4 months) Revision process (averages 3 months) Final editing and approval from ISCJ editor Completion and submission to Human Kinetics (needs to be at least 2 months prior to the issue cover month; e.g., completion by March 1 for the May issue)

*Note: All submissions must meet the standard ISCJ submission guidelines.

Individuals

Online subscriptions.

Individuals may purchase online-only subscriptions directly from this website. To order, click on an article and select the subscription option you desire for the journal of interest (individual or student, 1-year or 2-year), and then click Buy. Those purchasing student subscriptions must be prepared to provide proof of student status as a degree-seeking candidate at an accredited institution. Online-only subscriptions purchased via this website provide immediate access to all the journal's content, including all archives and Ahead of Print. Note that a subscription does not allow access to all the articles on this website, but only to those articles published in the journal you subscribe to. For step-by-step instructions to purchase online, click here .

Print + Online Subscriptions

Individuals wishing to purchase a subscription with a print component (print + online) must contact our customer service team directly to place the order. Click here to contact us!

Institutions

Institution subscriptions must be placed directly with our customer service team. To review format options and pricing, visit our Librarian Resource Center . To place your order, contact us .

Most Popular

© 2024 Human Kinetics

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.149.115]

- 185.80.149.115

Character limit 500 /500

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Sports coaches’ knowledge and beliefs about the provision, reception, and evaluation of verbal feedback.

- 1 Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia

- 2 Institute for Health and Sport, Victoria University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Coach observation studies conducted since the 1970s have sought to determine the quantity and quality of verbal feedback provided by coaches to their athletes. Relatively few studies, however, have sought to determine the knowledge and beliefs of coaches that underpin this provision of feedback. The purpose of the current study was to identify the beliefs and knowledge that elite team sport coaches hold about providing, receiving and evaluating feedback in their training and competition environments. Semi-structured interviews conducted with 8 coaches were inductively analyzed, revealing three broad themes: thinking and learning about feedback, providing feedback, and evaluating feedback. Findings revealed a detailed array of knowledge about feedback across a wide range of sub-topics. Coaches saw feedback as a tool to improve performance, build athlete confidence, help athletes to monitor progress, and as a tool to improve their own performance. Novel insights about evaluating an athlete’s reception of feedback, and tailoring feedback for individual athletes, were provided by coaches. The findings also highlight areas in which future coach education offerings can better support coaches to provide effective feedback.

Introduction

Coaches are thought to require strong procedural knowledge about the pedagogical strategies required to help athletes learn effectively ( Nash and Collins, 2006 ) in addition to possessing specific knowledge about their sport. Recent studies have investigated the knowledge of coaches regarding sport-specific topics such as resistance training ( Harden et al., 2019 ), swimming technique ( Morris et al., 2019 ), and talent identification ( Roberts et al., 2019 ). However, a major gap in this growing body of literature about coach knowledge concerns the use of pedagogical techniques such as feedback in coach practice. Therefore, the research question for consideration in this paper concerns what coaches know and believe about the provision, reception, and evaluation of coach-athlete verbal feedback. It is acknowledged that feedback in an elite sporting setting is not limited to that provided verbally by a coach. Although important in the overall context of learning design in an elite sporting setting, the role of the coach as a practice designer and facilitator of athletes seeking their own feedback ( Woods et al., 2020 ) is not the primary focus of the current paper. A large body of coach observation literature consistently finds that verbal feedback represents one of the most common coach behaviors observed ( Partington and Cushion, 2013 ), with rates of over 60 feedback messages per game reported recently in an elite setting ( Mason et al., 2020a ). As such, an investigation into verbal feedback appears important to determine the knowledge that coaches hold about this major element of their practice.

Feedback is widely regarded as a frequently used and high-impact strategy to progress a learner from current to goal performance ( Kluger and DeNisi, 1996 ; Hattie, 2009 ). Many studies have quantified and analyzed coach feedback in both training and performance settings (e.g., Partington et al., 2015 ; Halperin et al., 2016 ). However, an area receiving less attention is the investigation of coach knowledge and beliefs underpinning the feedback they provide ( Smith and Cushion, 2006 ). Supplementing the large body of empirical evidence on coach feedback in practice with an investigation of the experiential knowledge of expert coaches is considered to be an important direction for improving pedagogical practice ( Greenwood et al., 2014 ). Qualitative investigations of coach practice such as interviews ( Tinning, 1982 ; Potrac et al., 2002 ) may assist in providing greater detail about the contexts and constraints that coaches operate under in reality ( Kahan, 1999 ). Recent studies examining coach knowledge (e.g., Roberts et al., 2019 ) have not yet filled the gap in the area of pedagogical strategies such as feedback.

In education, a large body of evidence exists on teacher beliefs and links to their subsequent practice. Reviews of this literature suggest that teachers hold a variety of beliefs about their pedagogical practice that vary across context and cultures, and that these beliefs are usually related to the pedagogical practices they adopt ( Fang, 1996 ; OECD, 2009 ). Importantly, it is suggested that efforts to improve teacher practice must take into account the perceptions and beliefs of teachers ( Putnam and Borko, 1997 ). Similarly, an understanding of coach beliefs about feedback is an important step in ultimately improving coach feedback practices, and coach education in general ( Côté et al., 1995 ). There is evidence that myths from the field of education have been adopted by sports coaches; 62% of surveyed coaches in the United Kingdom believed that individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred learning style ( Bailey et al., 2018 ). This is contrasted with many major reviews (e.g., Pashler et al., 2009 ) which concluded that there is “no adequate evidence base” (p. 105) for the effectiveness of learning styles. More broadly, several authors have lamented the absence of a belief in evidence-based approaches to pedagogy in high performance coaching ( Rushall, 2003 ; Davids et al., 2017 ).

Current evidence on coach knowledge about feedback suggests a wide spectrum of philosophies, ranging from the highly coach-controlled to a more facilitative and athlete-centered approach ( Côté et al., 1995 ; Potrac et al., 2002 ; Smith and Cushion, 2006 ). In the former category is a case study of an expert English soccer coach, who reported beliefs toward providing feedback such as “they’ve got to be told what is expected of them” ( Potrac et al., 2002 , p. 191). The coach expressed a desire to be in control of his players during training because his job security ultimately depended on game-day success, and this was reflected in the feedback he provided. In another study, gymnastics coaches reported preferring to provide their athletes with feedback constantly ( Côté et al., 1995 ), reflecting that it was important that their athletes “know where they are regularly” (p. 82). These high levels of coach control are contrasted with evidence that some coaches adopt a highly athlete-centered approach to feedback. Smith and Cushion (2006) found that expert English soccer coaches used silence strategically during in-game coaching to allow players to make decisions without an overly prescriptive approach. Coaches also reported not wanting to overload athletes with information, preferring to provide a small number of simple prompts. Allowing the athletes to experiment without coach intervention, and asking an athlete to self-evaluate before providing feedback, were strategies mentioned by the more athlete-centered coaches interviewed in the Côté et al. (1995) study. Across studies, a similar spectrum is seen when coaches are asked to consider feedback valence; some coaches report using up to 90% negative feedback ( Côté et al., 1995 ), while others reported a more balanced approach ( Smith and Cushion, 2006 ). This evidence suggests large variations in coach beliefs about effective feedback practices, which may reflect the unique challenges ( Lyle, 2002 ) represented by the different contexts in which coaches work. For example, and of interest to the current study, is the differences in feedback between team and individual sport coaches. It appears that determining the gap between current coach practice and “best practice” for feedback as reported in the literature is an important task in improving the feedback that coaches give.

A potential challenge for this area of research is evidence to suggest that coaches can be inaccurate when reflecting on their use of feedback. For example, rowing coaches were observed providing verbal feedback to their athletes during training, and then an hour later they were asked about the feedback they provided ( Millar et al., 2011 ). It was found that coaches overestimated desirable feedback patterns by between 5 and 40%; coaches tended to underestimate their use of highly prescriptive instruction, and overestimate their use of questioning to allow athletes to evaluate performance or describe affective feeling about performance. Coaches also appear to over-report the provision of tactical information over technical information compared to actual rates observed in the feedback they provided to athletes ( Pereira et al., 2009 ; Millar et al., 2011 ). Additionally, coaches and athletes show low agreement when asked to recall the types of feedback provided by the coach, with the highest correlation in one study r = 0.26 between athlete and coach perceptions ( Smoll and Smith, 1980 ). These findings highlight the importance of triangulating coach interview data with observational data where possible.

An area not commonly considered in feedback research is the reception of feedback ( Anderson, 2010 ); much time and effort has been spent on determining the quality and quantity of feedback provided, without considering its reception and subsequent action by a receiver. Little is known about the ways in which coaches evaluate their feedback to determine its reception and use by their athletes. Barriers to the successful reception of feedback by athletes include discrepancies in interpretations of feedback between the provider and the receiver ( Liberman et al., 2005 ; Adcroft, 2011 ). Other barriers include variations in the characteristics of the feedback receiver such as working memory capacity ( Buszard et al., 2017 ), or the receiver’s self-efficacy to receive and act on feedback ( Narciss and Huth, 2004 ). There have been numerous calls in the literature ( Langley, 1997 ; Potrac et al., 2000 ) for research designs to consider the athlete’s ability to receive feedback, but relatively few studies have done so (for an example, see Mason et al., 2020b ). Despite the importance of considering individual athlete factors, there is evidence to suggest that coaches may have high confidence but low accuracy when judging their athletes’ mental skills ( Leslie-Toogood and Martin, 2003 ).

Present Study

The literature on coach beliefs and knowledge about verbal feedback is still in its infancy. The variation observed in what coaches know and believe regarding the provision of feedback may be caused by factors such as experience, context, or perceived job pressure. Additionally, a major gap in the area is an understanding of how coaches consider athlete factors such as the capacity and disposition to receive verbal feedback from a coach. Supplementing the large body of empirical evidence on coach feedback in practice with an investigation of the experiential knowledge of expert coaches is considered to be an important direction for improving pedagogical practice ( Greenwood et al., 2014 ).

The purpose of this study was to qualitatively determine the knowledge and beliefs currently held by elite sport coaches with regard to the provision, reception, and evaluation of verbal feedback in training and competition environments. Given the proposition that coaches must possess a strong understanding of the pedagogical strategies required to help athletes learn effectively ( Nash and Collins, 2006 ), along with evidence that coaches may hold some misconceptions about pedagogy ( Bailey et al., 2018 ), it was hypothesized that there would be much variance in the beliefs and knowledge about feedback, with varying degrees of support from academic evidence.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

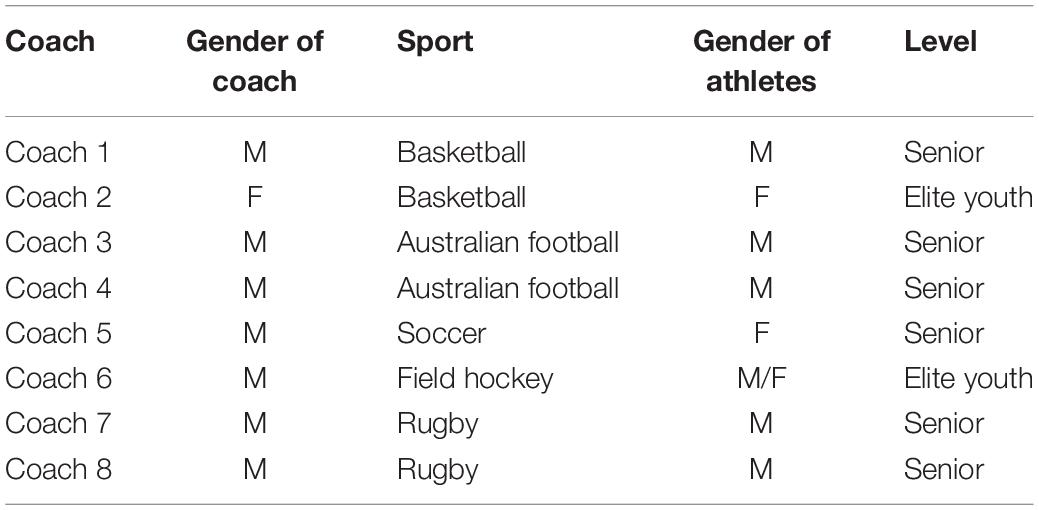

Eight coaches currently employed in a high performance team sport setting were recruited for the study. Recruitment was limited to coaches who had at least 5 years of experience coaching in a high performance setting. For the purpose of the study, this was defined as a professional national-level league or international representative (i.e., national team) setting. This definition is broadly consistent with similar previous studies that have sought to investigate high performance coaches ( Rynne and Mallett, 2012 ; Morris et al., 2019 ). The sampling procedure was aligned with a purposeful sampling approach ( Creswell, 2013 ), to ensure that expert coaches who have experience with a high-performance team sport environment could provide insight into the research questions. Coaches were aged between 32 and 52 years ( M = 42.63, SD = 6.55), and had a mean experience level of 9.75 years (SD = 3.20) in a high performance setting. Coaches represented the sports of Australian rules football (2), rugby (2), basketball (2), soccer (1) and field hockey (1). Five coaches were involved in elite national-level competitions with senior athletes, two were involved with elite youth national representative teams (under 18 age group), and one was involved with a senior national representative team. Six of the coaches had participated as athletes in the sport they coached to a high performance level, while two had not. Demographic information about the participating coaches is provided in Table 1 .

Table 1. Coach demographic information.

Participants were recruited via email or phone. At the time of the interview, participants were provided with a plain language statement and consent form, and were given the chance to answer questions about the study before enrolling. All participants were assured of anonymity and informed that participation was entirely voluntary. Ethics approval was obtained from the Melbourne Graduate School of Education’s Human Ethics Advisory Group (Ethics ID: 1851890.1).

Interview Guide

To assist with consistency between interviews, a semi-structured interview guide was constructed. General information sought from the participant at the beginning of the interview included current role, time in current role, total years of experience coaching in a high performance setting, and any relevant experience as an athlete. These questions served to provide important demographic information, and were also used as rapport-building opening conversations to introduce a relaxed, conversational style to the interview ( Côté et al., 1995 ). Researchers are encouraged “to keep uppermost in one’s mind the fact that the interview is a social, interpersonal encounter, not merely a data collection exercise” ( Cohen et al., 2011 , p. 421), so care was taken to develop this rapport initially.

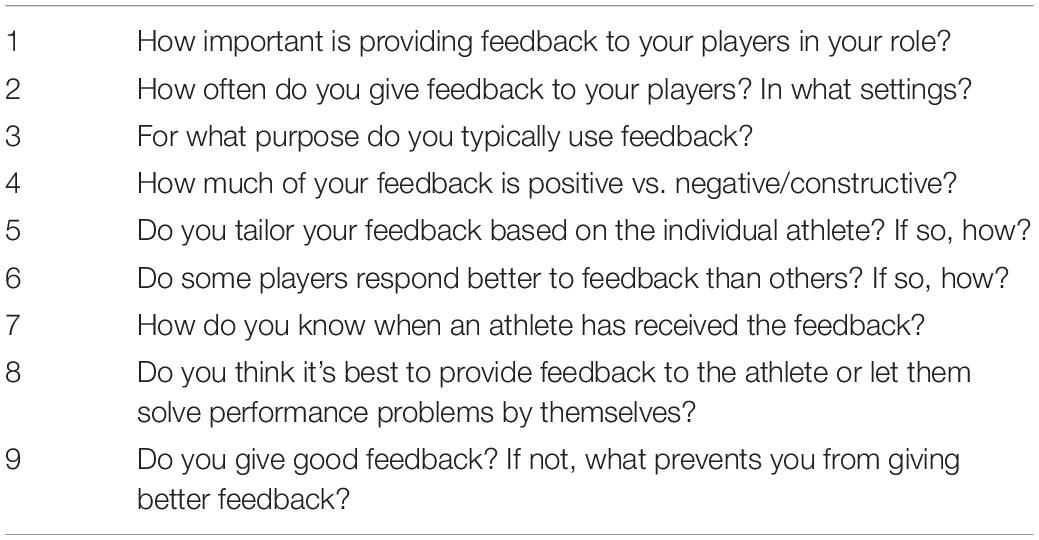

Questions from the main part of the interview focussed specifically on the research question; a list of questions can be found in Table 2 . Consistent with a semi-structured interview approach, probes (e.g., “Are there any other ways you know the feedback has been received?”) were used when participants provided relevant but incomplete information, to seek a deeper response, or to ensure the clarity of the response. Any new topics that emerged during the course of the interview were explored by the interviewer, consistent with methods adopted in similar semi-structured interview research in sport ( Potrac et al., 2002 ).

Table 2. Interview questions.

The study protocol was explained to participants, who were then offered an opportunity to ask questions about their involvement in the study and assured of the confidentiality of their identity and responses. Informed consent was then obtained from the participant via a hard-copy form. All interviews were recorded on an Apple iPhone 6S, and an Apple MacBook Pro internal microphone was used as a second backup recorder. All interviews were conducted by the first author, who has undertaken undergraduate and postgraduate training in qualitative and quantitative research methodology. Interviews were conducted primarily in person ( n = 5), with a further 3 interviews conducted via phone or Skype; research suggests that Skype and phone interviews can be an appropriate replacement for in-person interviews where geography is a limiting factor ( Deakin and Wakefield, 2014 ). Interview duration was between 14 and 46 min ( M = 27.25, SD = 10.42). Within 24 h of the interview, the interviewer transcribed the interviews verbatim into a Microsoft Word document. All participants were provided with a copy of the interview transcript within 1 week of the interview, and asked to check the transcript for accuracy and clarity.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were uploaded into NVivo for analysis. Given the precedent in coaching literature for an inductive approach to qualitative interview data ( Potrac et al., 2002 ; Rynne and Mallett, 2012 ), data analysis in the current study also adopted an inductive approach. The process of inductively coding data followed the methods outlined by Côté et al. (1993) . First, interview transcripts were read and assigned a label to begin the general process of categorizing the data. At this stage, the primary focus of coding was to organize rather than to interpret. Following a first round of coding, all labels were compared and assigned a broader category, a process known as creating categories ( Côté et al., 1993 ). For example, any text tagged with “positive feedback” or “descriptive feedback” was assigned to a category called “types of feedback.” In completing a similar procedure, Rynne and Mallett (2012) acknowledged that categories remained flexible due to the need for adjustment as coding took place; in the current study, many instances of re-coding took place as themes emerged and developed. The final step in the analysis process involved the naming of final themes, along with the generation of a narrative to accompany each theme in the context of the research question for presentation in this article ( Braun and Clarke, 2006 ). Categories discussed by at least half of coaches (i.e., 4 or more), or that were considered theoretically important for the research area, were included in the final themes.

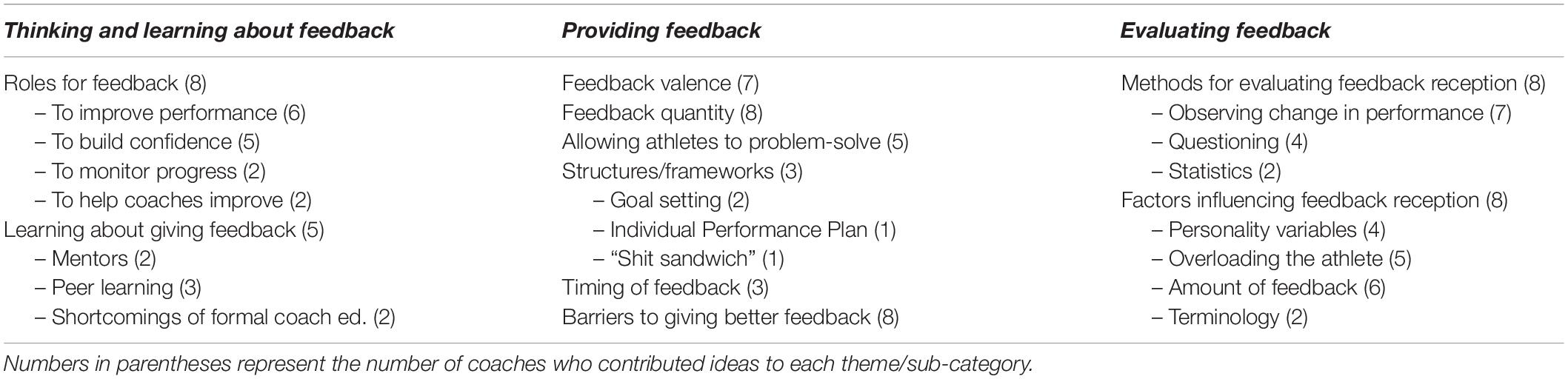

The three higher-order categories that emerged throughout the inductive analysis procedures were thinking and learning about feedback, providing feedback , and evaluating feedback . The major sub-themes of each category are presented in Table 3 below. The following section will detail the major findings within each category and sub-theme with respect to the range of knowledge and beliefs held by the high performance coaches interviewed. Where relevant, quotes from interviewees are included with the pseudonyms Coach 1 through to Coach 8. The gender-neutral pronoun “they” has been used throughout to conceal the gender of the coach.

Table 3. Emerging themes and sub-categories following the process of inductive analysis.

Thinking and Learning About Feedback

One of the major categories identified through the collation of sub-themes was the way in which coaches conceptualize, learn about, and reflect on their use of feedback. Sub-themes under this category include: coach beliefs about the roles of feedback, and sources of learning about providing feedback.

Roles of Feedback

Coaches held varying beliefs about the role and purpose of feedback in their coaching practice that fell into four main themes: improving performance, monitoring progress, helping coaches to improve, and building athlete confidence. A strongly held belief was that coaches see feedback as a major tool for improving individual and team performance. Coach 7 reflected on the importance of feedback for improvement, stating that “if you don’t get feedback, you don’t really know how you’re tracking and how you’re developing.” Coach 7 went on to clarify that they saw feedback as a tool to help both athletes and coaches grow, suggesting that feedback is conceptualized not only as something to be given by coaches, but also received and used to improve coaching practice.

Aside from the role of feedback as a means for improving performance, 5 interviewees also discussed the importance of feedback for building confidence and providing reassurance when both individual and team performance was not ideal. Coach 4 spoke of the importance of showing positive video feedback to their team following a loss in order to re-motivate the group. This was also discussed by Coach 1, who said that they would often ask video analysts in their organization to just cut up some positive footage because a player’s “confidence is so bad right now.” The role of feedback as reassurance also extended to a competition setting, with Coach 2 reflecting that “I think 50% of my job on game day is to tell them [the athletes] that everything is okay, and that they’re going okay.” Coach 3 took a different approach to the motivational role of feedback, sharing that they often provided overly positive feedback to one athlete with the hope that it may induce competitiveness and prompt other athletes to “strive for similar feedback.”

Learning About Giving Feedback

Coach 5 believed that having a mentor was an effective method for improving their use of feedback, stating that “the best thing that any new coach could do is partner up.” A common theme was that coaches trusted advice from experienced peers, with Coach 6 explaining that “I’d probably like to go from experience and what’s worked for them [another coach] rather than going for something completely drastic and new.” Coach 8 reflected critically on formal coach education courses, stating that “I enjoy doing them, just the piece of paper doesn’t do much for me,” while also speaking of the importance of informal learning for their improvement as a coach. It appears that coaches already working at the high performance level see limited benefit in obtaining formal accreditation, instead valuing the informal learning opportunities presented by collaborating with peers or mentors.

Providing Feedback

A second major category emerging from the interview data relates to beliefs and knowledge about the practicalities involved with providing feedback. In this section, sub-themes include: feedback valence, feedback quantity, providing feedback vs. allowing athletes to problem-solve, structures and frameworks, timing, and barriers to giving better feedback.

Feedback Valence

One of the most commonly discussed beliefs amongst the interviewed coaches was the ideal ratio of positive to negative (also referred to by the coaches as “constructive,” “growth” and “room for improvement”) feedback. There was a common acknowledgment from interviewed coaches that rates of positive to negative feedback vary according to the coach’s personal style and the context in which they operate. Coach 1 recalled an experience of working under a head coach who was “a little more old school” and “doesn’t think much about being more positive… if he has something to say about it [a video clip], he’s going to say it,” while also acknowledging their own style to be more “modern” and responsive to the needs of the athlete. Half of the coaches articulated the belief that providing too much negative feedback was detrimental to athlete performance. For example, Coach 8 reported striving to show athletes positive examples to guide them toward desired behavior, rather than negative examples that show an athlete performing poorly. Coach 3 believed that mostly positive feedback should be used during competition, with “constructive” feedback left for breaks in competition or during training. Like many other coaches, Coach 3 believed that the motivational benefits of positive feedback could enhance performance during competition, with negative feedback believed to cause doubt or impact the concentration of the athlete.

Feedback Quantity and “Overloading” Athletes

All coaches spoke about feedback quantity, with over half discussing their struggle find the right balance between providing enough feedback to ensure the most salient points were covered, but also keeping feedback quantity within a range that was manageable for athletes to use. Coach 7 used an analogy to describe their approach to deciding on feedback quantity: “If I tried to throw you 10 tennis balls, you’d probably catch 2–3… If I throw you 2–3 tennis balls, you’ll probably catch 2–3… Players can only retain a certain amount of information, and chunking up that information from smaller bits is really important.” The philosophy of Coach 2 was similar: “2–3 [pieces of feedback] tops.” Coach 4 reported taking an individualized approach to deciding on the amount of feedback provided to athletes, considering motivation to be an important factor in determining how much feedback athletes prefer: “[My approach is] if you want the info I’ll give it to you, but I’m not going to chase you either. If I’m chasing them they’re probably not going to look at it anyway. They’ve got to drive it and want it themselves.”

Providing Feedback vs. Allowing Athletes to Problem-Solve

The influence of training design frameworks such as the constraints-led approach, where coaches are encouraged to design environments in which athletes are able to solve problems rather than simply being told by a coach ( Renshaw et al., 2016 ), was clearly seen in coach responses. This was summarized by Coach 8, who observed the following:

They’re the ones out there on the field in the heat of the battle. For me to come in and tell them everything… well, I’m not out there to solve their problems on game day, on the field. I just want to steer them and guide them to come up with the answers.

Coach 5 was stronger in their phrasing, believing that “you’re not winning the game from the coaches’ box.” Coach 3 took this philosophy into their training design, reporting that they often manipulated the amount of feedback provided during a training session to encourage athletes to problem-solve without coach intervention: “I’ll say to the coaching staff, we’re not holding their hands through any of the session, don’t say anything to them… they have to find their own way.” When reflecting on their work with less experienced coaches, Coach 2 believed that a novice coach is more likely to adopt an “I tell” coaching mentality, in which coaches will “tell them [the athletes] what they see without giving the student/player an opportunity to think of their own answers.” Coach 4 believed that this led to negative outcomes for both coach and athlete, whereby the coach “can easily get frustrated when they give advice and then they don’t see that change in behavior from the player.”

Structures and Frameworks

Three of the eight coaches discussed a more formal approach to providing feedback, detailing the frameworks they have in place for providing regular feedback to their athletes. This was most common in coaches who worked with a national squad, where athletes typically train in their local environments when not with the national team. For example, Coach 6 reported providing regular feedback in the context of an individual performance plan (IPP), in which 3–4 goals are set in consultation between the athlete and coach before a tournament begins. Coach 6 then works with athletes during the course of a tournament to provide feedback against the goals outlined in the IPP. After tournament completion, Coach 6 triangulates feedback from themselves as head coach, their assistant coaches, and self-assessment from the athlete themselves before generating a new IPP for their local context.

Other coaches reported less formal structures for providing feedback. Coach 7 reported their use of the colloquial “shit sandwich” method of providing feedback: “Start with a positive, then a negative, then finish with a positive. I was taught that way back when. In some ways when I do my game reviews, I structure it a bit like that. Here’s some things we did really well, here are some things we need to fix up, look at efforts where we did really well off the ball. I still haven’t gone too far away from that.”

Timing of Feedback

Three coaches explicitly mentioned the importance of timing feedback for maximum impact on their athletes. Coach 3 believed that feedback was often most effective if provided before an opportunity to implement it in performance, choosing to provide feedback directly before training when practical, in order to see immediate change in performance. Coach 3 suggested that:

Feedback at the end of the session is good, just general feedback or how they performed or whatever, but if there is a particular thing that you need them to try and get, I have found it’s gotta be right before the next session so it’s fresh.

Coach 8 relayed similar sentiments, believing that feedback “on-the-run” during training or competition was more easily implemented than feedback given in a video review setting away from the performance environment.

Perceived Barriers to Giving Better Feedback

All coaches reflected on challenges they faced in their day-to-day roles that may not be conducive to providing feedback that is in line with their views of “best practice.” One of the most commonly reported barriers was time. Coaches 3 and 6 both worked with national representative squads, where intensive tournament play at international level is often interspersed with months away from athletes while they train and play with their local teams. Coach 3 reflected that “you might only see them [athletes] for a few days at a pre-tournament camp, and then it’s another 2 months until another camp.” Coach 6 spoke of the importance of checking in on individual athletes in their local environments, to ensure continuity and consistency of feedback across the course of a year. Coach 8 mentioned the difficulty associated with having up to 15 players under their care during a season, admitting that some players don’t sit down with a coach to review footage and receive feedback for “a couple of weeks.” To circumvent this, the coach provides feedback in a group setting more regularly.

Evaluating Feedback

A major focus of this paper is on determining the beliefs, knowledge and reported approaches taken by coaches with regard to feedback reception. Coach 6, a former school teacher, was a particularly strong advocate for more closely considering the reception of feedback by athletes:

I think athletes, or kids in school, they almost need to be trained or given methods of what is feedback and how to receive feedback. We think about how we deliver it a lot, and we put a lot of effort into ourselves – hopefully – in that area, but it’s actually a skill to receive feedback.

The following section presents coach reflections on: methods for evaluating feedback reception, and factors influencing the reception of feedback by an athlete.

Methods for Evaluating Feedback Reception

Coaches were varied in the extent of their responses to questions relating to the reception of feedback by athletes, and typically fell into one of two groups: one group of coaches appeared to prefer a practical approach to evaluating feedback reception by way of observing physical performance, while another group reported using pedagogical tools such as questioning for assessing player knowledge and retention of feedback.

The most common response from coaches was that performance in competition is a reliable measure of the effectiveness of feedback; for example, Coach 1 reflected that “the way you know if it’s been 100% effective is if they do what you told them, at the end of the day, on the court.” However, two coaches also believed that this method of evaluating feedback was not completely reliable, citing extraneous variables such as skill errors or athletes choosing not to buy in to the coach’s strategic changes as possible reasons that observing performance may not accurately reflect the reception of feedback.

Another commonly reported method for seeking evidence that feedback has been received by athletes is through questioning or otherwise designing a learning environment where athletes can provide verbal evidence of understanding to the coach. Coach 5 explained their approach to providing video feedback, stating that they believed the feedback had been received “… if they can take you through a different piece of vision or a different scenario from the one where we first might have unearthed an issue or whatever it was, and they can talk it back to you.” Coach 8 believed that an athlete-centered approach to video feedback meetings was needed in order to evaluate feedback reception:

If I’m doing all the talking, I don’t know if they’re understanding what I’m saying. I ask a lot of questions, or I put up a clip and get them to tell me what they’re thinking. That way we can sort of find somewhere in between where we can meet.

Other reported methods for evaluating feedback reception include reading non-verbal markers such as body language, and analyzing in-game statistics.

Athlete Characteristics Influencing Feedback Reception

Coaches were asked to report any characteristics of their athletes that are perceived to act as facilitators or barriers to the athletes receiving feedback. Four coaches described attitude or entitlement problems observed in their athletes. This reportedly led to a reluctance to receive and accept feedback, particularly negative or constructive feedback. Coaches suggested that ego and previous experience with overly positive feedback were the main contributors. For example, Coach 2 shared their experience with athletes who are “overwhelmed by positive feedback from people around them, and they believe the hype.” Coach 3 reflected that the most difficult athletes to coach are:

… the ones that have coaches back home that have told them what they’ve wanted to hear all of the time. They haven’t had a coach who has been constructive with them, and they haven’t got family that say “you still need to work on this.” They have surrounded themselves with “yes” people.

Other coaches spoke of the “participation trophy era” (Coach 5), alluding to a phenomenon whereby junior athletes receive trophies for simply entering an event, not just for winning. It appears that a major challenge for coaches is adjusting the approach they take when providing feedback to athletes who exhibit a reluctance to receive feedback.

Another belief frequently mentioned by coaches in this area related to knowing the athlete as an individual and acknowledging the ways in which they prefer to receive feedback. Coaches alluded to this being the “art” of coaching; for example, Coach 8 reflected, “that’s coaching, isn’t it? Knowing who wants what.” The importance of differentiating feedback for individuals was acknowledged by Coach 7, who ran pre-season surveys with all their athletes to determine their preferences for receiving feedback.

The most commonly reported methods of differentiating feedback for players involved tailoring the amount or the valence of the feedback. Coach 1 reported that their assistant coaches were mindful of the amount of video feedback that athletes preferred. For example, “[this athlete] doesn’t like watching film, so let’s just keep it short, 3–4 clips.” Coach 6 believed that certain athletes had a natural feel for the game and didn’t benefit as greatly as others from video feedback: “To some guys the footage can just become a drag for them. Some of those natural players, you start showing them all that and putting them into a box – well that’s not what they’re good at.” Coach 6 believed that giving these types of athletes feedback in a training environment may be more productive than in a video review session. Similarly, coaches believed that certain athletes benefited more from either positive or negative feedback, differentiating based on preference. Coach 3 spoke of their experience working with athletes who varied in their need for feedback: “[player], you just had to tell her how great she was all the time… others, you could be a lot harder on.” Coach 4 believed that most of their athletes preferred hearing positive feedback, but observed that some athletes in their squad have “an ability to have a bit more of a ‘dressing down’ type of feedback.”

The aim of the study was to determine the knowledge and beliefs currently held by high performance sport coaches with regard to the provision, reception, and evaluation of feedback. The findings presented above illustrate the multifaceted and complex nature of current coach knowledge about feedback. The notion that coaches must possess knowledge of pedagogical strategies required to help athletes learn effectively ( Nash and Collins, 2006 ) was supported by a rich array of information collected about the many strategies that coaches use for providing and evaluating feedback in their roles. As predicted, there were also some areas in which coach knowledge about feedback did not align with current evidence.

A number of ideas emerging from the interview data align with prior research. The most fundamental of these was the belief that feedback is a useful tool for improving both individual and team performance. Coaches considered feedback to be a vital part of their role and a commonly used pedagogical tool, implemented with the intention to improve player performance. Links between feedback and performance are reflected throughout a range of feedback literature ( Kluger and DeNisi, 1996 ; Hattie and Timperley, 2007 ; Randell et al., 2011 ). Importantly, the notion of receiving feedback as a coach in order to improve coaching practice was also mentioned, reflecting Hattie and Clarke’s (2018) emphasis on feedback being a two-way process between receiving and giving. The idea of using student assessments as feedback on teaching is not new in education ( Nicol and MacFarlane-Dick, 2006 ), but the current study also shows that coaches seek feedback from athletes to evaluate their impact in much the same way.

Coaches articulated preferences for informal learning sources when asked about how they might upskill themselves in the area of feedback, with five coaches referring to learning from peers or a more experienced coach as a preferred way to seek improvement. One coach reflected critically on formal learning sources such as accredited coach education courses. These sentiments align with evidence from previous studies on coach education, where typical findings are that informal learning sources such as discussions with peers are preferred over formal courses ( Erickson et al., 2008 ; Stoszkowski and Collins, 2016 ). One reason for this preference, with particular relevance to the interview data, is that formal coach education courses often do not allow for substantial participant interaction ( Demers et al., 2006 ). Striking a balance between allowing for the sharing of experiences between coaches, while also advocating for evidence-based feedback practices that do not promote neuromyths ( Bailey et al., 2018 ) or folk pedagogy ( Bruner, 1996 ), appears an important endeavor for future coach education offerings. Working with a mentor ( McQuade et al., 2015 ) or coach developer ( North, 2010 ) may be an avenue for further exploration, given the learning preferences articulated by coaches in the current study.

An area yielding novel data in the current study relates to the use of questioning by coaches to check for feedback reception. Previous studies suggest that coaches ask few questions ( Potrac et al., 2002 ), and that coaches tend to overestimate their use of questioning when asked to self-report ( Millar et al., 2011 ). Coaches in previous studies also report not wanting to ask too many questions due to a desire to avoid appearing indecisive or lacking expertise ( Potrac et al., 2002 ). Despite this, evidence suggests that questioning paired with feedback can have a positive effect on performance ( Chambers and Vickers, 2006 ). A commonly reported method for evaluating feedback reception in the current study was through questioning, with five coaches suggesting that they check for player understanding of feedback through using open-ended questions. Coaches also reported creating athlete-centered learning environments in which athletes were encouraged to show evidence of their understanding through analyzing video with coach feedback withheld. Athlete-centered coaching has been noted in the literature as an effective method for improving performance and motivation of athletes ( Light and Harvey, 2017 ). An important avenue for future research appears to be matching self-reports of teaching behaviors with observations to verify their accuracy. However, the data collected in the current study provides evidence of commonly held knowledge that there are a number of ways to check for feedback reception.