Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Women's health

- Medicine and health sciences

- Benign breast conditions

- Cardiovascular diseases in women

- Maternal health

- Obstetrics and gynecology

- Osteopenia and osteoporosis

- Get an email alert for Women's health

- Get the RSS feed for Women's health

Showing 1 - 13 of 9,667

View by: Cover Page List Articles

Sort by: Recent Popular

Echogenic intracardiac foci detection and location in the second-trimester ultrasound and association with fetal outcomes: A systematic literature review

Hope Eleri Jones, Serica Battaglia, [ ... ], Sinead Brophy

Shroud waving self-determination: A qualitative analysis of the moral and epistemic dimensions of obstetric violence in the Netherlands

Rodante van der Waal, Inge van Nistelrooij

Facilitators and barriers to vaccination uptake in pregnancy: A qualitative systematic review

Mohammad S. Razai, Rania Mansour, [ ... ], Pippa Oakeshott

Enhanced peer-group strategies to support the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission leads to increased retention in care in Uganda: A randomized controlled trial

Alexander Amone, Grace Gabagaya, [ ... ], Philippa Musoke

Factors associated with bypassing primary healthcare facilities for childbirth among women in Devchuli municipality of Nepal

Manisha Maharjan, Sudim Sharma, Hari Prasad Kaphle

Birth preparedness and complication readiness among recently delivered women in Hargeisa town, Somaliland: A community-based cross-sectional study

Abdeta Muktar Ahmed, Mohamed Abdilahi Ahmed, Mohammed Hassen Ahmed

Impact of COVID-19 on antenatal care provision at public hospitals in the Sidama region, Ethiopia: A mixed methods study

Zemenu Yohannes Kassa, Vanessa Scarf, Sabera Turkmani, Deborah Fox

Histopathologic patterns and factors associated with cervical lesions at Jimma Medical Center, Jimma, Southwest Ethiopia: A two-year cross-sectional study

Birhanu Hailu Tirkaso, Tesfaye Hurgesa Bayisa, Tewodros Wubshet Desta

Multilevel negative binomial analysis of factors associated with numbers of antenatal care contacts in low and middle income countries: Findings from 59 nationally representative datasets

Adugnaw Zeleke Alem, Biresaw Ayen Tegegne, [ ... ], Tsegaw Amare Baykeda

ex vivo , patient-derived explant model of endometrial cancer">Development of a long term, ex vivo , patient-derived explant model of endometrial cancer

Hannah van der Woude, Khoi Phan, [ ... ], Claire Elizabeth Henry

Estimates of the incidence, prevalence, and factors associated with common sexually transmitted infections among Lebanese women

Hiam Chemaitelly, Ramzi R. Finan, [ ... ], Wassim Y. Almawi

Comparison of perinatal outcome and mode of birth of twin and singleton pregnancies in migrant and refugee populations on the Thai Myanmar border: A population cohort

Taco J. Prins, Aung Myat Min, [ ... ], Rose McGready

Understanding the uptake and determinants of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV services in East Africa: Mixed methods systematic review and meta-analysis

Feleke Hailemichael Astawesegn, Haider Mannan, Virginia Stulz, Elizabeth Conroy

Connect with Us

- PLOS ONE on Twitter

- PLOS on Facebook

- Frontiers in Global Women's Health

- Maternal Health

- Research Topics

COVID-19 and Women's Health

Total Downloads

Total Views and Downloads

About this Research Topic

As a result of the Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, the world is facing one of the greatest challenges we have experienced in over a century. The economic consequences for society at large are potentially catastrophic. The health and social care sectors have reacted by providing emergency care on an ...

Keywords : COVID-19, Women's Health, Pregnancy

Important Note : All contributions to this Research Topic must be within the scope of the section and journal to which they are submitted, as defined in their mission statements. Frontiers reserves the right to guide an out-of-scope manuscript to a more suitable section or journal at any stage of peer review.

Topic Editors

Topic coordinators, recent articles, submission deadlines.

Submission closed.

Participating Journals

Total views.

- Demographics

No records found

total views article views downloads topic views

Top countries

Top referring sites, about frontiers research topics.

With their unique mixes of varied contributions from Original Research to Review Articles, Research Topics unify the most influential researchers, the latest key findings and historical advances in a hot research area! Find out more on how to host your own Frontiers Research Topic or contribute to one as an author.

- Annual Awards

- Mission and Vision

- Share Your Story

- Women’s Health Research

- Board of Directors

- Collaborations

- Partner with SWHR

- Philanthropy

- Job Opportunities

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Endometriosis and Fibroids

- Roundtables

- Science Events

- Advisory Council

- Women’s Health Policy Agenda

- Position Statements

- Policy Letters

- Legislation

- Policy Events

- Read My Lips

- Women’s Health Equity Initiative

- Coronavirus

- Publications

- Peer-Reviewed Articles

- Guides & Toolkits

- SWHR in the News

- Read Women’s Health Stories

- Annual Awards 2024

- Annual Awards 2023

- Annual Awards 2018-2022

EMPACT MENOPAUSE STUDY

SAVE THE DATE FOR THE

April 25, 2024, annual awards gala.

READ THE NEW

Endometriosis, teen toolkit, in english and spanish.

READ THE MENOPAUSE

Preparedness toolkit.

WATCH THE #SWHRTALKSHPV VIDEO SERIES

READ THE LIVING WELL

With lupus toolkit.

Women have unique health needs, and most diseases and conditions affect women differently than men.

The Society for Women’s Health Research (SWHR) is the thought leader in advancing women’s health through science, policy, and education and promoting research on sex differences to optimize women’s health. We are making women’s health mainstream.

Work that matters

Biological differences between the sexes exist, from a single cell to the entire body. SWHR is bringing attention to sex and gender differences in health and disease in order to address unmet needs and research gaps in women’s health.

WHAT IS WOMEN’S HEALTH RESEARCH?

Two-thirds of those with Alzheimer’s disease are women.

Women may experience different heart attack symptoms than men., 90% of women with sleep apnea go undiagnosed., women often have a stronger and faster immune system response to infections than men., migraine is three times more common in women than men., upcoming swhr events.

Join us for expert conversations on women’s health research and care, hosted by SWHR and featuring SWHR leaders.

Upcoming Events › SWHR Event

Swhr 2024 annual awards gala.

SWHR is excited to announce the 2024 Annual Award Gala will be held in the newly renovated National Museum of Women in the Arts. After being shuttered for over two years, NMWA recently reopened to the public.

Breaking Barriers in Alzheimer’s Disease: Perspectives on Early Stage Alzheimer’s

Approximately two-thirds of Alzheimer’s disease patients are women, as well as more than 60% of their caregivers. Stigma surrounding Alzheimer’s and dementia can cause some women to dismiss symptoms as normal aging or menopausal brain fog and delay talking to their health care provider. Moreover, coverage of screening and diagnostic tests can be difficult and confusing to navigate, also contributing to delays in diagnosing and treating Alzheimer’s. An early diagnosis is essential for slowing the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, planning…

Talking All Things Women’s Heart Health

Heart disease is the number one killer of both women and men annually in the United States. Yet, less than half of women recognize its role as the leading cause of death among women. During this virtual event, SWHR will host a "fireside chat" style conversation with Dr. Stephanie Coulter of The Texas Heart Institute about the current state of cardiovascular disease screening and diagnostics, what barriers might hinder women’s access to care, and potential solutions to overcome those barriers…

Exploring Obesity’s Impact on Women and Policy’s Role in Improving Outcomes

Obesity is a significant public health issue in the United States, affecting millions of Americans and costing billions of dollars in health care expenses. Women are disproportionately affected by the obesity epidemic, both in terms of their health outcomes and the economic costs of the disease. There are also notable racial and economic disparities associated with obesity. During this congressional briefing, panelists will explore the disproportionate impact of obesity on women, including obesity risk factors that are unique to women,…

SWHR Pre-Conference Symposium: Lights, Camera, and Action to Improve Women’s Heart Health

Part of the OSSD Annual Meeting This event is taking place on Sunday, May 5 at 12:10-2:05 p.m. CET, in-person in Bergen, Norway. The Society for Women’s Health Research (SWHR) is committed to advancing women’s health through science, policy, and education while promoting research on sex differences to optimize women’s health. Although research has documented sex differences in heart health and disease, insufficient attention to the study of sex, gender, and hormones in cardiovascular research and a lack of inclusion…

SWHR Emerging Scholars in Women’s Health Research Award Symposium

The SWHR Emerging Scholars in Women’s Health Research Award is given to trainees whose abstracts submitted to the OSSD Annual Meeting demonstrate research excellence in addressing important knowledge gaps in health and disease areas that disproportionately, differently, or exclusively affect women.

VCU Health of Women 2024 | Emerging Topics in Women’s Health: Autoimmune Disease Challenge

Join us for the VCU Health of Women Conference 2024 SWHR Pre-conference Symposium! This symposium will discuss the impacts of autoimmune diseases on women’s health across the lifespan, with special emphasis on pregnancy and maternal health, caregiving/parenting.

SWHR Policy Advisory Council Meeting

SWHR’s Policy Advisory Council will meet for its quarterly closed-door meeting. Council members will have an opportunity to work collaboratively to develop policy positions, promote research, and create materials designed benefit women’s health.

One event on June 26, 2024 at 12:00 pm

One event on September 18, 2024 at 12:00 pm

One event on December 4, 2024 at 12:00 pm

September 2024

December 2024, what we’re doing, the women’s health equity initiative.

The Women’s Health Equity Initiative highlights statistics on women’s health in the United States and aims to engage communities on solutions to improve health equity across multiple disease states, conditions, and life stages. SWHR newly added lupus as a focus area to the Women’s Health Equity Initiative Dashboard in May 2023!

To learn more, visit www.swhr.org/healthequity .

The Women’s Health Dashboard

The SWHR Women’s Health Dashboard offers a platform to explore the latest national and state data on diseases and health conditions that have significant impacts on women’s health across the lifespan. Five women’s health issues emerged as the focus areas of the Dashboard: Alzheimer’s Disease, Breast Cancer, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Depressive Disorders, Ischemic Heart Disease.

Explore the full Dashboard at swhr.org/womenshealthdashboard .

Kit de Herramientas para la Endometriosis: Guía para Adolescentes

Descargar una copia del Kit de Herramientas para la Endometriosis: Guía para Adolescentes en español, para ayudar a empoderar a las adolescentes que viven con endometriosis y así entender mejor su salud y orientarse en su atención.

March is Endmetriosis Awareness Month!

SWHR Patient Toolkit: A Guide to Women’s Eye Health

This toolkit provides an overview of eye diseases and conditions that differently and disproportionately impact women.

March is Workplace Eye Wellness Awareness Month !

Supporting Children with Narcolepsy at School

Narcolepsy can have a significant impact on a child’s academic life, so communication and support from schools are critical. This fact sheet was created to support narcolepsy caregivers as they navigate reasonable accommodations and care for their families

March is Sleep Awareness Month !

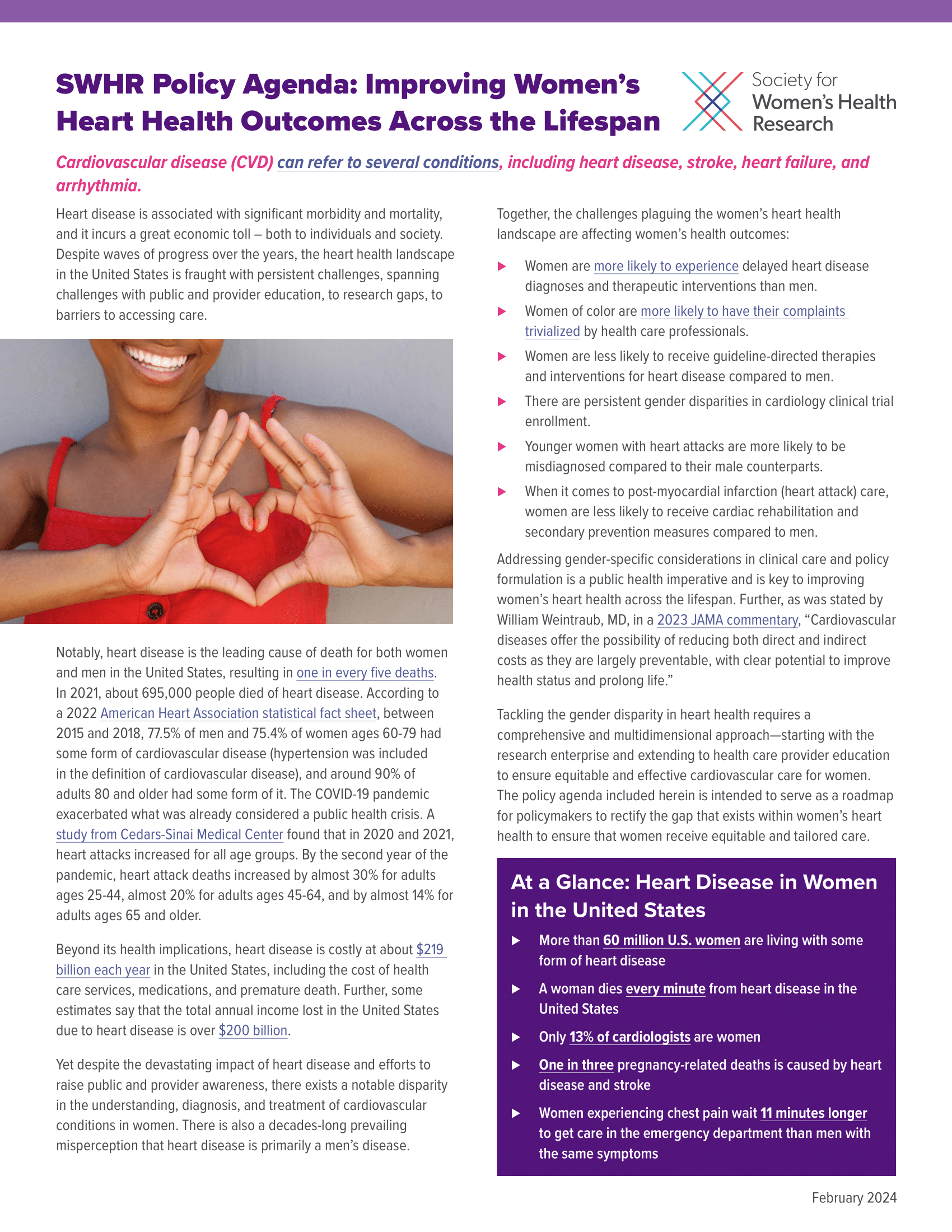

SWHR Policy Agenda: Improving Women’s Heart Health Outcomes Across the Lifespan

The agenda discusses policy needs and opportunities in women’s heart health. Insights for the policy agenda were informed by SWHR’s Heart Health Policy Working Group convening in September 2023.

LATEST SWHR RESOURCES

Latest swhr blogs, swhr in the news.

As part of our mission to improve women’s health and eliminate imbalances in care for women, SWHR serves as a resource on issues related to women’s health and sex differences research. Read recent op eds from and news articles featuring SWHR.

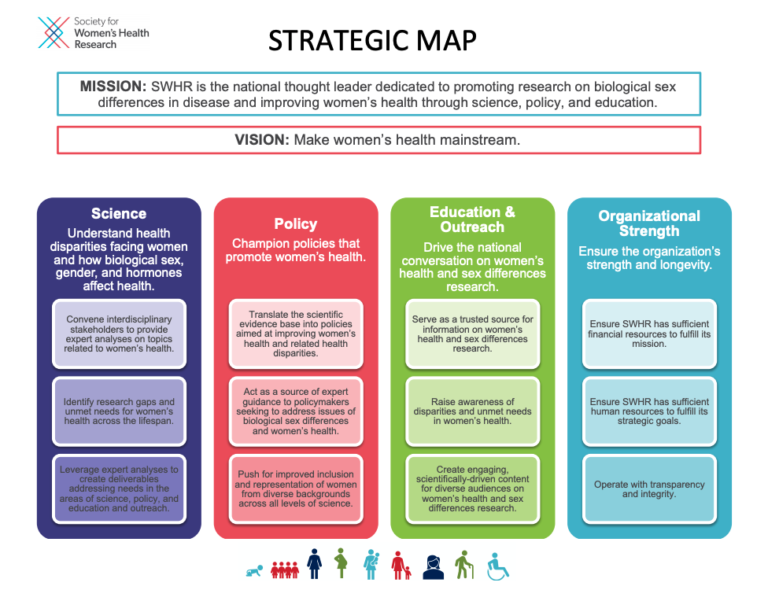

Learn more about SWHR’s science, policy and education efforts to make women’s health mainstream.

Learn more about SWHR’s mission, vision, and strategic map.

Learn more about our science programs.

SHARE YOUR STORY

Your story could help educate and inform other women who may be going through a similar experience.

LEARN HOW TO SHARE YOUR STORY

SWHR is asking women to share their personal health journeys, to be posted on the SWHR website and other SWHR-branded material, as appropriate. In addition to patient stories, SWHR is interested in the stories of those who serve as caregiver for a family member (parent, spouse, child, etc.). Your story is powerful and we hope to share with policymakers, researchers, providers and most importantly, other women.

WE’RE leading the way

Together with our partners from diverse sectors, we bring attention to areas of need in women’s health.

ABOUT SWHR SWHR IN THE NEWS PARTNER WITH SWHR SUPPORT SWHR

PRIORITIZING WOMEN’S HEALTH

Since 1990, SWHR has been championing for research and policy that improves women’s health.

IN FDA DRUG TRIALS

After years of SWHR advocacy, in 2017, for the first time, women accounted for over half of research participants for approved drugs.

11 SCIENCE NETWORKS

IDENTIFYING GAPS IN RESEARCH

SWHR convenes researchers, clinicians, patients and other stakeholders to effect change in overlooked areas of women’s health

- Skip to main content

- Skip to FDA Search

- Skip to in this section menu

- Skip to footer links

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- Search

- Menu

- Science & Research

- Science and Research Special Topics

Women's Health Research

From the fda office of women's health.

OWH promotes and conducts research initiatives that facilitate FDA regulatory decision-making and advance the understanding of sex differences and health conditions unique to women. Learn more about women’s health research in the Women’s Health section, including links below.

About OWH research

OWH scientific programs support research, workshops, and initiatives that advance understanding of women’s health issues.

OWH-funded research

Learn more about research funded by OWH, including how to apply for extramural research funding, and a searchable list of projects.

Peer-reviewed scientific publications

OWH staff and OWH-funded researchers are working to advance the science of sex differences. View peer-reviewed publications.

Women's health education and training

Find continuing education opportunities, upcoming events, and subscribe to receive the latest information about future opportunities from OWH.

RELATED INFORMATION

Pregnancy exposure registries

Information collected can help health care providers and others who are pregnant learn more about the safety of medicines and vaccines used during pregnancy.

Bench to Bedside: Sex as a Biological Variable (SABV)

Free self-paced training on sex and gender differences that impact health, disease, and treatment, developed by OWH in collaboration with the National Institutes of Health.

Free publications for women

Download or order free copies of more than 40 fact sheets on women’s health topics.

Follow Office of Women's Health

X (formerly twitter).

Follow FDA Office of Women's Health @FDAWomen

Watch videos from Office of Women's Health on YouTube's FDA Channel

OWH Newsletter

The OWH newsletter highlights women's health initiatives, meetings, and regulatory safety information from FDA.

Paragraph Header Contact the FDA Office of Women's Health

(301) 796-9440 Phone (301) 847-8601 fax

Hours Available

Office of Women's Health

FDA Office of Women's Health Newsletter

The Office of Women's Health newsletter highlights women's health initiatives, meetings, and regulatory safety information from FDA.

The WHI program is funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

- WHI SharePoint

- WHI email (outlook)

© 2021 Women’s Health Initiative. All rights reserved

- Open access

- Published: 03 October 2023

Women’s midlife health: the unfinished research agenda

- Sioban D. Harlow 1 ,

- Lynnette Leidy Sievert 2 ,

- Andrea Z. LaCroix 3 ,

- Gita D. Mishra 4 &

- Nancy Fugate Woods 5

Women's Midlife Health volume 9 , Article number: 7 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

801 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Introduction

In 2015 we launched Women’s Midlife Health with the aim of increasing scientific focus on the midlife -- a critical window for preventing chronic disease, optimizing health and functioning, and promoting healthy aging. This life stage, from about age 35–40 years to about 60–65 years, is coincident with the menopausal transition in women, encompassing the late reproductive to late postmenopausal stages of reproductive aging [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. As noted in our initial editorial [ 5 ], in addition to the hallmark symptoms of menopause, the midlife is a vulnerable window for onset of gynecologic and hormone-sensitive conditions as well as onset or exacerbation of symptoms, symptom burden and functional limitations. It is also the critical window for interventions to reduce the loss of bone strength associated with menopause, to protect heart health and to promote psychosocial well-being. At the time we started this publication, relatively few journals were interested in manuscripts on midlife aging, except for a handful focused on menopause and reproductive aging. Women’s Midlife Health was designed to fill this gap. We developed an international community of investigators studying the intersection of menopause and midlife health who have contributed to enlarging scientific understanding, developing an international view of the perimenopause and acquainting investigators with studies of menopause around the world. Over the past decade, as scientific knowledge has increased, documenting the importance of the midlife for healthy aging, menopause journals have expanded their scope and aging journals have expanded their breadth. As multiple excellent venues are now available to publish work on midlife health, we have decided to cease publication of this journal. In our closing editorial, we provide reflections on what we have achieved and outline some of the continuing critical gaps in scientific knowledge.

The unfinished research agenda

Scientific terminology for menopause and reproductive aging was initially defined only in 1980 [ 6 ]. At about the same time, social scientists were documenting unexpected variation in symptom experience within and across populations [ 7 , 8 , 9 ], alerting practitioners to a previously unrecognized need to understand the physiology and context of menopause and midlife. Concerted and well-funded research efforts to advance knowledge about the natural history of menopause, including data on its changing physiology and pathophysiology and their related biosocial changes, were initiated in the last decades of the twentieth century [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. In the 1990’s and early 2000’s, the first wave of cohort studies elucidated the hormonal transitions that characterize ovarian aging and the specific symptoms attributable to them while documenting the inter-relationships between ovarian aging and bone, cardiovascular, and musculoskeletal aging. Over the last two decades these insights have led to the establishment of an evidence-based model for staging reproductive aging (i.e., the STRAW + 10 model ) [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ], a developing theory of midlife aging with initial guidance as to critical windows for intervention, and an appreciation of variation in age at menopause and symptom experiences related to the complex interplay across physiologic and sociocultural systems that can influence, adversely or beneficially, the prospects for healthy aging. Moreover, foundational studies over the past three decades have laid the groundwork for understanding ovarian aging and its interface with other aspects of aging in midlife. Critical gaps in scientific knowledge remain that will require a new generation of well-funded studies. Some gaps represent a simple failure to ask basic questions, others signal a need for an expanded global focus encompassing further geographic and population diversity in the midlife experience, while others reflect the new research questions that have arisen from our current studies.

Although considerable information has been generated regarding the nature of ovarian aging for women who experience natural menopause, information for women experiencing surgical menopause (double oophorectomy), hysterectomy [ 15 ] and for women with chronic illnesses (e.g., HIV, cancer or autoimmune disease) that alter the menopause experience, remains lacking. Often excluded from study samples or analyses by design, yet likely to experience more abrupt hormonal changes and symptomatology, and more adverse health consequences, studies addressing the trajectories of ovarian aging and associated symptoms and pathophysiologic changes are warranted. Such studies are of particular importance given the differing risks of hysterectomy and surgical menopause by race, ethnicity and region of residence and the health risks associated with early menopause and premature ovarian insufficiency [ 16 ]. Also, given recent evidence of racial and ethnic differences in the timing of menopause, symptom experience and clustering of risk factors, considerably more focus on the midlife experience of minoritized populations and population specific risk factors, including the impact of structural racism, is of paramount importance [ 17 ].

Similarly, data on the midlife continues to remain limited from low- and middle-income countries, despite the important contribution of chronic diseases to the global burden of disease. As pointed out in our series on Contraception in Midlife, Demographic and Health Surveys, a major source of health information for many countries, only interview women of reproductive age, from ~ 15 to 49 years old [ 18 ]. Here, too, evaluation of context specific health risks common in such settings, such as the impact of high parity, early and late childbirth, increased risk of pelvic floor disorders, anemia, infectious diseases, high parasite load, life-long under-nutrition, and the increasing frequency of natural disasters associated with climate change is lacking. Other population subgroups for whom information on the menopausal transition experience and medical care options is limited are lesbian and transgender individuals.

As the STRAW + 10 model for staging reproductive aging [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ] predates the generation of a substantive literature on the relationships between declines in anti-mullerian hormone (AMH), ovarian reserve and menopause, a revision of the STRAW + 10 model incorporating information on AMH levels across stages of the menopausal transition is overdue.

Also, given the substantive body of literature now published on the natural history of menopause and midlife health, knowledge translation to intervention trials and education of women and their health care providers is urgently needed. For example, the now well documented timing of precipitous bone loss during the late menopausal transition stages [ 19 ] argues for earlier screening of at-risk women and trials aimed at evaluating whether treatment across the trans-menopausal period (from approximately 2 years before until 1 year after the menopause) can prevent this precipitous loss. Similarly, most health care providers remain poorly informed about how to evaluate and treat bothersome menopausal symptoms, while much of what we have learned has yet to be made accessible to women themselves. This gap continues despite the publication of numerous rigorous randomized controlled trials that could easily be clinically translated so that women can choose, based on truthful comparisons and accurate information about the magnitude of benefits and risks, from many pharmacologic therapies that modestly improve vasomotor symptom frequency, severity, midlife sleep problems and menopause-related quality of life [ 20 ].

One intriguing insight gained over the last quarter century, is the complex interplay among symptoms and physiologic risk factors, suggesting that more attentions to bi- and multi-directional relationships among symptoms and heart, cognitive, and psychosocial health is warranted. For example, the relative timing of and feedback across endocrine changes, sleep disturbances, vasomotor symptoms and cognitive health remain poorly understood as does the inter-relationship between sleep, vasomotor symptoms, heart rate variability and cardiovascular risk.

We have learned a great deal about the types of life challenges facing midlife women from studies begun in the 1990s and later. Nonetheless, we need to remain vigilant to the unique and evolving stressors facing midlife women as they provide an important understanding of the social context for women’s health. Recent research about menopause and the workplace is just one dimension needing consideration, along with the pressures of family life (partners, children, and aging parents to name a few) [ 21 , 22 , 23 ].

Some further areas that have received limited attention to date and remain understudied include:

The relationship between the increased menstrual flow experienced by most women during the menopausal transition -- often consistent with definitions of abnormal uterine bleeding -- and classic symptoms of menopause including fatigue, trouble focusing, depression and anxiety, heart palpitations and hot flashes;

Risk factors for and pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying vasomotor symptoms that are not timed to changes in reproductive hormone levels, including those that begin long before and last long after the final menstrual period;

Differences in the risks and consequences of hot flashes versus night sweats, two symptoms that are often combined into vasomotor symptoms but vary dramatically in experience and are identifiably different on ambulatory monitor graphs;

The impact of exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals, including forever chemicals, heavy metals and other environmental pollutants on endocrine function, musculoskeletal changes, heart health and cognition across the midlife;

The relationship between menstrual disorders prior to midlife and symptoms experienced during menopause, and their impact, or not, on work productivity;

Assessment of menopausal symptoms/outcomes across countries and cultures using both quantitative and qualitative surveys, collecting both symptom presence and symptom bothersomeness in the context of women’s lives;

The role of structural racism, neighborhood conditions, and historical trauma on timing of menopause and risk of menopausal symptoms and on the symptom and health burden women carry as they enter the menopausal transition; and,

Investigation of factors associated with positive menopausal transitions, including research on effects of education about menopause, provision of anticipatory guidance to help women manage the changes they are facing, and their development of attributions helping them sort the menopause-related to life-related factors.

As we approach the next generation of midlife studies, priority should also be given to advancing research methods, including in the following areas:

As serial hormonal testing is not accessible to many women and in many countries, development of a validated bleeding questionnaire for staging reproductive aging;

Building on core outcomes developed for vasomotor symptoms and genitourinary symptoms of menopause, definition of a core outcomes for additional symptoms of menopause and midlife health endpoints ( https://medicine.unimelb.edu.au/school-structure/obstetrics-and-gynaecology/research/COMMA ) [ 24 , 25 ]; and,

Given the complex interplay of multiple pathophysiologic changes that underlie symptoms and disease onset across the midlife, further development of statistical methods that permit simultaneous modeling of both the means and variances of multiple dynamic trajectories.

Finally, collaboration with health professional organizations is necessary to enrich their educational preparation to provide appropriate and helpful care to women in anticipation of and during the peri- menopause and post-menopause.

In closing, Women’s Midlife Health has met its goal of opening opportunities for publications on this critical lifestage and has published several important topical series on contraception, pain, stress, disability and structural racism in addition to innovative papers that have expanded the paradigm of and refocused the research agenda for women’s health. All papers will remain accessible at https://womensmidlifehealthjournal.biomedcentral.com/ and on PubMed https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ . We thank all the authors and reviewers who contributed to the success of the journal.

Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, et al. For the STRAW + 10 collaborative Group. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging Reproductive Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(4):1159–68.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, et al. For the STRAW + 10 collaborative Group. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging Reproductive Aging. Menopause. 2012;19(4):387–95.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, et al. For the STRAW + 10 collaborative Group. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging Reproductive Aging. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(4):843–51.

Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, et al. For the STRAW + 10 collaborative Group. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging Reproductive Aging. Climacteric. 2012;15(2):105–14.

Harlow SD, Derby CA. Women’s midlife health: why the midlife matters. Women’s Midlife Health. 2015;1:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-015-0006-7 .

WHO Scientific Group on Research on the Menopause & World Health Organization. Research on the menopause: report of a WHO scientific group [meeting held in Geneva from 8 to 12 December 1980]. 1981; World Health Organization. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/41526 .

Flint M. The menopause: reward or punishment? Psychosomatics. 1975;16:161–63.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kaufert P, Lock M, McKinlay S, Beyene Y, Coope J, Davis D, Eliasson M, Gognalons-Nicolet M, Goodman M, Holte A. Menopause research: the Korpilampi workshop. Soc Sci Med. 1986;22(11):1285–9.

Lock M. Ambiguities of aging: japanese experience and perceptions of menopause. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1986;10(1):23–46.

Szoeke S, Coulson C, Campbell M, et al. Cohort profile: women’s healthy Ageing Project (WHAP) - a longitudinal prospective study of australian women since 1990. WomensMidlife Health. 2016;2:5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-016-0018-y .

Article Google Scholar

Woods NF, Mitchell ES. The seattle midlife women’s Health Study: a longitudinal prospective study of women during the menopausal transition and early postmenopause. Women’s Midlife Health. 2016;2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-016-0019-x .

Sowers MFR, Crawford SL, Sternfeld B, Morganstein D, Gold EB, Greendale GA, SWAN: a multi-center, multi-ethnic, community-based cohort study of women and the menopausal transition Menopause: biology and pathobiology. Lobo, Kelsey RA et al. J., Marcus, R. San Diego Academic Press 2000 pp175-188.

Freeman EW, Sammel MD. Methods in a longitudinal cohort study of late reproductive age women: the Penn ovarian aging study (POAS). Women’s Midlife Health. 2016;2:1. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-016-0014-2 .

Oppermann K, Colpani V, Fuchs SC, et al. The Passo Fundo Cohort Study: design of a population-based observational study of women in premenopause, menopausal transition, and postmenopause. Women’s Midlife Health. 2015;1:12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-015-0013-8 .

Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, Stewart AW. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112(7):956–62.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

InterLACE Study Team. Variations in reproductive events across life: a pooled analysis of data from 505 147 women across 10 countries. Hum Reprod. 2019; 1;34(5):881–893.

Harlow SD, Burnett-Bowie SAM, Greendale GA, et al. Disparities in Reproductive aging and midlife health between Black and White women: the study of women’s Health across the Nation (SWAN). Women’s Midlife Health. 2022;8:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-022-00073-y .

Harlow SD, Dusendang JR, Hood MM, et al. Contraceptive preferences and unmet need for contraception in midlife women: where are the data. Women’s Midlife Health. 2017;3:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-017-0026-6 .

Karlamangla AS, Burnett-Bowie S-AM, Crandall CJ. Bone Health during the Menopause Transition and Beyond. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2018;45(4):695–708.

https:// icer.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ICER_Menopause_FinalReport_01232023.pdf .

Thomas AJ, Mitchell ES, Pike KC, et al. Stressful life events during the perimenopause: longitudinal observations from the seattle midlife women’s Health Study. Women’s Midlife Health. 2023;9:6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-023-00089-y .

Sievert LL, Huicochea-Gómez L, Cahuich-Campos D, et al. Stress and the menopausal transition in Campeche, Mexico. Women’s Midlife Health. 2018;4:9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-018-0038-x .

Hardy C, Thorne E, Griffiths A, et al. Work outcomes in midlife women: the impact of menopause, work stress and working environment. Women’s Midlife Health. 2018;4:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-018-0036-z .

Lensen S, Bell RJ, Carpenter JS, Christmas M, Davis SR, Giblin K, Goldstein SR, Hillard T, Hunter MS, Iliodromiti S, Jaisamrarn U, Khandelwal S, Kiesel L, Kim BV, Lumsden MA, Maki PM, Mitchell CM, Nappi RE, Niederberger C, Panay N, Roberts H, Shifren J, Simon JA, Stute P, Vincent A, Wolfman W, Hickey M. A core outcome set for genitourinary symptoms associated with menopause: the COMMA (Core Outcomes in Menopause) global initiative. Menopause. 2021;28(8):859–66.

Lensen S, Archer D, Bell RJ, Carpenter JS, Christmas M, Davis SR, Giblin K, Goldstein SR, Hillard T, Hunter MS, Iliodromiti S, Jaisamrarn U, Joffe H, Khandelwal S, Kiesel L, Kim BV, Lambalk CB, Lumsden MA, Maki PM, Nappi RE, Panay N, Roberts H, Shifren J, Simon JA, Vincent A, Wolfman W, Hickey M. A core outcome set for vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: the COMMA (Core Outcomes in Menopause) global initiative. Menopause. 2021;28(8):852–8.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Sioban D. Harlow

Department of Anthropology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, USA

Lynnette Leidy Sievert

Herbert Wertheim School of Public Health and Human Longevity Science, University of California San Diego, San Diego, USA

Andrea Z. LaCroix

Australian Women and Girls’ Health Research Center, School of Public Health, University of Queensland, Seattle, Australia

Gita D. Mishra

School of Nursing, University of Washington, Seattle, USA

Nancy Fugate Woods

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the conceptualization, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sioban D. Harlow .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication, competing interests.

Nothing to declare.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Harlow, S.D., Sievert, L.L., LaCroix, A.Z. et al. Women’s midlife health: the unfinished research agenda. womens midlife health 9 , 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-023-00090-5

Download citation

Published : 03 October 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-023-00090-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Women’s Health

Women's Midlife Health

ISSN: 2054-2690

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Call the OWH HELPLINE: 1-800-994-9662 9 a.m. — 6 p.m. ET, Monday — Friday OWH and the OWH helpline do not see patients and are unable to: diagnose your medical condition; provide treatment; prescribe medication; or refer you to specialists. The OWH helpline is a resource line. The OWH helpline does not provide medical advice.

Please call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room if you are experiencing a medical emergency.

A-Z Health Topics

- Anorexia nervosa

- Anxiety disorders

- Autoimmune diseases

Return to top

- Bacterial vaginosis

- Binge eating disorder

- Birth control methods

- Bladder control

- Bladder pain syndrome (interstitial cystitis)

- Bleeding disorders

- Breast cancer

- Breast reconstruction after mastectomy

- It's Only Natural: Breastfeeding information for African-American communities

- Business Case for Breastfeeding

- Supporting Nursing Mothers at Work: Employer Solutions

- Bulimia nervosa

- Caregiver stress

- Carpal tunnel syndrome

- Cervical cancer

- Chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS)

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Date rape drugs

- Depression during and after pregnancy

- Domestic violence/abuse

- Eating disorders

- Emergency birth control/emergency contraception

- Endometriosis

- Female genital mutilation or cutting (FGM/C)

- Fibroids (uterine)

- Fibromyalgia

- Genital herpes

- Genital warts

- Getting active

- Graves' disease

- Hashimoto's disease

- Health Information Gateway (formerly Quick Health Data Online)

- 2015 Report to Congress on Activities Related to Improving Women's Health

- Healthy eating

- Healthy living by age

- Healthy weight

- Make the Call

- Heart-healthy eating

- HIV and AIDS

- Human papillomavirus (HPV)

- Hysterectomy

- Infertility

- Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

- Interstitial cystitis (bladder pain syndrome)

- Iron-deficiency anemia

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Menstrual cycle

- Mental health

- Myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS)

- Myasthenia gravis

- National Women and Girls HIV/AIDS Awareness Day

- National Women's Health Week

- Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome/Opioid Withdrawal in Infants

- Nursing (breastfeeding)

- Oral health

- Osteoporosis

- Ovarian cancer

- Ovarian cysts

- Ovarian syndrome (PCOS or polycystic ovary syndrome)

- Overweight, obesity, and weight loss

- Ovulation calculator

- Pap and HPV tests

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

- Pelvic organ prolapse

- Period (menstruation)

- Physical activity (exercise)

- Postpartum depression

- Pregnancy and medicines

- Pregnancy tests

- Prenatal care

- Premenstrual syndrome (PMS)

- Quick Health Data Online (now Health Information Gateway )

- Screening tests and vaccines

- Sexual assault

- Sexually transmitted infections (STDs, STIs)

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs), pregnancy, and breastfeeding

- Sickle cell disease

- Sleep and your health

- Spider veins and varicose veins

- Stress and your health

- Thyroid disease

- Trichomoniasis

- Urinary incontinence

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Uterine cancer

- Uterine fibroids

- Vaginal yeast infections

- Varicose veins and spider veins

- Violence against women

- Viral hepatitis

- Weight loss (and overweight and obesity)

- Yeast infections

- Birth control

- Fitness and nutrition

- Healthy aging

- Quick Health Data Online

- Menstruation and the menstrual cycle

- Screening tests for women

- Female genital cutting

- Nutrition (and fitness)

- Men's health

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Binge eating

- HIV and AIDS

- HHS Non-Discrimination Notice

- Language Assistance Available

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Disclaimers

- Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

- Use Our Content

- Vulnerability Disclosure Policy

- Kreyòl Ayisyen

A federal government website managed by the Office on Women's Health in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

1101 Wootton Pkwy, Rockville, MD 20852 1-800-994-9662 • Monday through Friday, 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. ET (closed on federal holidays).

- Departments & Services

- Directions & Parking

- Medical Records

- Physical Therapy (PT)

- Primary Care

Header Skipped.

- Department of Medicine

Division of Women's Health

Division of women's health research.

The Division of Women’s Health’s research goals are: to lead scientific and clinical discoveries that identify and explain sex- and gender-based differences in health and disease, prioritize disorders specific to women, and ultimately improve the overall health and access to care for women and men. Faculty in the Division of Women’s Health pursue a wide range of research topics dedicated to advancing knowledge of women’s health and sex differences in health and disease. To learn more about specific research programs and areas, visit our research website: Women's Health Research .

Research Areas

- Cancer Screening & Prevention

- Cardiovascular Disease

- Clinical Neuroscience & Neuroendocrinology

- Gender, Violence & Trauma

- Global Women’s Health

- Life Course & Reproductive Epidemiology

- Women’s Health Policy Research & Advocacy

Research Faculty

- Kathryn Rexrode, MD, MPH Professor of Medicine Division Chief

- Laura Holsen, PhD Assistant Professor of Psychiatry

- Ingrid Katz, MD, MHSc Associate Professor of Medicine

- Annie Lewis-O'Connor, MSN, MPH, PhD Instructor in Medicine

- Roseanna Means, MD Associate Professor of Medicine, Part-time

- Lydia Pace, MD, MPH Assistant Professor of Medicine

- Alexandra Purdue-Smithe, PhD Instructor in Medicine

- Janet Rich-Edwards, ScD, MPH Associate Professor of Medicine

- Eve Rittenberg, MD Assistant Professor of Medicine

- Meghan Rudder, MD Instructor in Medicine

- Hanni Stoklosa, MD, MPH Instructor in Medicine

- Jennifer J. Stuart, ScD Instructor in Medicine

Affiliate Faculty

- Deborah Bartz, MD, MPH

- Kari Braaten, MD, MPH

- Ann Celi, MD

- Ming Hui Chen, MD, MMSc, FACC, FASE

- Alisa Goldberg, MD, MPH

- Jill Goldstein, PhD

- Tamarra James-Todd, PhD, MPH

- Elizabeth Janiak, ScD

- Tamara Bockow Kaplan, MD

- Bharti Khurana, MD

- Nomi Levy-Carrick, MD

- Rose L. Molina, MD, MPH

- Maria Nardell, MD

- Jennifer Scott, MD, MBA, MPH

- Caren Solomon, MD, MPH

- Paula Emma Voinescu, MD, PhD

Learn more about Brigham and Women's Hospital

For over a century, a leader in patient care, medical education and research, with expertise in virtually every specialty of medicine and surgery.

Stay Informed. Connect with us.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Home — Essay Samples — Nursing & Health — Maintaining Health — Women's Health

Essays on Women's Health

It's a crucial topic that affects the well-being of half the population. Writing an essay about Women's Health can help raise awareness, educate others, and spark important conversations. Plus, it's a chance to dive deep into a subject that impacts so many lives.

When choosing a topic for your Women's Health essay, consider what interests you the most. Are you drawn to issues like reproductive health, mental wellness, or access to healthcare? Think about what you're passionate about and what you think others should know more about. This will help you narrow down your focus and make your essay more engaging.

For an argumentative essay on Women's Health, you could explore topics like the impact of gender stereotypes on healthcare, the importance of reproductive rights, or the challenges of maternal healthcare in underserved communities. For a cause and effect essay, consider topics such as the link between mental health and hormonal changes, the effects of gender-based violence on women's well-being, or the impact of societal beauty standards on women's self-esteem.

If you're leaning towards an opinion essay, you might want to delve into topics like the role of women in healthcare leadership, the importance of inclusive healthcare policies, or the impact of social media on women's body image. And for an informative essay, you could explore topics like the history of women's reproductive rights, the science behind menopause, or the prevalence of mental health issues in women.

For a thesis statement on Women's Health, consider statements like "Access to comprehensive reproductive healthcare is a fundamental human right," "Societal beauty standards have a detrimental impact on women's mental health," or "Gender biases in medical research have led to disparities in women's healthcare."

When crafting your essay , you might want to start with a compelling statistic or a thought-provoking question. For example, "Did you know that women are 50% more likely to be misdiagnosed following a heart attack?" or "Imagine living in a world where your access to healthcare is determined by your gender."

In your essay , you can reinforce your main points and leave the reader with a call to action or a question to ponder. For example, "It's time to prioritize women's health and work towards a more inclusive and equitable healthcare system," or "What steps can we take to ensure that all women have access to the care they deserve?"

With the right topic, a strong thesis statement, and compelling s and s, your Women's Health essay has the potential to make a real impact. Let's dive in and start writing!

What's Killing Poor White Women: an Analysis

Contraception: a fundamental right for women's reproductive health, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

The Evolution of Vine Glo: a Comprehensive History

Things essential for women's health, the issue of mental illnesses in women in "the yellow wallpaper", why abortion should be legalized, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

A Research Paper on The Reasons Why Women Should Be Able to Have The Option of an Abortion

The impact of feelings on our health, research of female genital mutilation, and the reasons it should be banned, sexually transmitted diseases and its influence on women, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

Review on Depo-provera Injection

Symptom of menopause, polycystic ovary syndrome (pcos) review, the impact of urinary incontinence on older women’s life, pregnancy complications hypothyroidism, the factors of postpartum depression, the increasing incidence of caesarean sections and maternal age, an analysis of the health impacts of cosmetic surgeries, the difference between female genital mutilation and female genital operation, the reasons why female genital mutilation should be banned globally, cardiovascular diseases, metabolic syndrome and health behaviours of postmenopausal women working in agriculture, the efficacy of telephone-based lactation counseling: literature review, the detrimental issue of female genital mutilation, negative outcomes of female genital mutilation, the different adverse effects of abortion, importance of providing education concerning pregnancy and abortion, teenage abortions: the laws, impact and consequences, impact of overpopulation on women's health and autonomy, reasons why a woman should say "no" to induced abortion, the reasons why abortion should be illegal in the united states, relevant topics.

- Physical Exercise

- Sexual Health

- Mental Health

- Eating Disorders

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Bibliography

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Women's Health Research. Women’s Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promise. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010.

Women’s Health Research: Progress, Pitfalls, and Promise.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

4 Methodologic Issues in Women’s Health Research

In reviewing and evaluating research on women’s health, the committee considered not only conditions 1 and health determinants but also the types of research conducted. This chapter addresses methodologic issues with respect to women’s health, looking at study design, subject sampling, outcome measures, and analysis. The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) is then discussed as an example of what has been learned about methods of women’s health research from the studies already conducted. The information in this chapter helps the committee address question 4 from Box 1-4 , whether the most appropriate research methods are being used to study women’s health.

- STUDY DESIGN

Research can be conducted on molecules, cells, and animals (basic research); on individuals or populations (clinical or observational studies); and on health systems (health-services and health-policy research). Each type of study has strengths and weaknesses, and progress generally requires congruence of evidence from multiple studies of different designs. For example, progress in breast and cervical cancer came through basic and experimental clinical research and other epidemiologic studies that provided support for similar conclusions (see Chapters 2 and 3 ).

Two major types of clinical studies are observational studies and clinical trials. An observational study is a study in which investigators do not manipulate the use of or deliver an intervention (that is, they do not assign subjects to treatment and control groups) but only observe and measure outcomes in subjects who are (or are not, in the case of a comparison group) exposed to an intervention (for example, a smoking ban that decreases secondhand smoke exposure) (Rosenbaum, 2002). Such studies have less control of potential confounders than do experimental studies, such as randomized controlled trials, and are more prone to selection bias and to bias in the choice of comparison populations. Observational studies provide information for identifying associations and are especially useful for generating hypotheses for further testing; they are less useful for determining causality. The Nurses’ Health Study (NHS) and the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) are examples of large observational studies. The NHS was originally intended to investigate the potential long-term consequences of oral contraceptives and later adapted to investigate factors that influence women’s health, especially in preventing cancer (NHS, 2008). SWAN was designed to collect information on the natural history of menopause (SWAN, 2010).

A randomized clinical trial is a prospective experiment in which investigators assign an eligible sample of people randomly to one or more treatment groups and a control group and follow subjects’ outcomes. Randomized clinical trials are usually considered the best for testing the efficacy of a treatment or intervention (Rosenbaum, 2002). The Women’s Health Study (WHS) was a randomized clinical trial in which the interventions were aspirin and vitamin E (WHS, 2009). The WHI consisted of both an observational study and three blinded, randomized clinical trial components that had hormone therapy, calcium and vitamin D, or dietary and exercise modification as the interventions (WHI, 2010). The randomized clinical trial in the WHI identified a risk of heart disease to be associated with combination estrogen hormone therapy, which was previously thought to be cardioprotective, and it confirmed the risk of breast cancer, venous thromboembolism, and stroke. Confidence in those results facilitated a decision to halt the study and led to a rapid change in prescribing practices (WHI, 2010).

Randomized clinical trials, however, have limitations of their own. Because of the expense and number of subjects needed to assess a given drug or other treatment, it is not possible to change key variables. The ability to extrapolate the results to a larger population might also be limited (Rosenbaum, 2002). In addition, ethical and practical considerations of the studies, including the ethics of placebo controls, need to be taken into account.

- SUBJECT SAMPLING

If study results are to be extrapolated to the general population, the research sample needs to reflect the general population. Ensuring that research can be applied to the general population requires more than simply incorporating members of a subpopulation as part of the overall sample; it requires adequate numbers to ensure the statistical power to evaluate effects in that subpopulation. It is important to note that using gender or sex as a control variable is not the same as examining the effects of gender or sex on a given outcome. Thus, the issue is not simply including women in trials but including sufficient numbers to test effects on both women and men. To be fully informative, findings need to be reported separately by sex or gender. If a subpopulation, such as women in this case, is excluded or underrepresented in the sample, it is difficult to know whether the results will apply to the subpopulation or whether it would have responded differently. For example, that lack of data can delay translation of research findings on effective treatments to the excluded or underrepresented subpopulation or can lead to adverse outcomes because of inappropriate application to one population of treatments developed on another.

It might seem obvious that poor clinical outcomes can occur if it is presumed that there are no sex or gender differences when they do exist, but false inferences and bad outcomes can also result from a presumption of sex or gender differences when such differences do not exist (Baumeister, 1988). For example, the first randomized clinical trial of estrogen therapy, the Coronary Drug Project, was done in men. That study was discontinued prematurely because of a lack of evidence of a positive effect and a trend toward increased cardiovascular mortality in the treated group (The Coronary Drug Project Research Group, 1973). The doses in the trial were much higher than those given to women, so the results were thought not to be relevant to women, and estrogen therapy continued to be prescribed to women to reduce cardiovascular risks. More than 20 years after the study, postmenopausal hormones were still among the top-selling drugs in the United States—an estimated 15 million women were taking them (Hersh et al., 2004). Conversely, statins (that is, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase inhibitors) were first shown to be effective in lowering cholesterol in a Scottish trial in men (Shepherd et al., 1995). Of 5 randomized controlled trials published in 1994–1998, the Scottish trial was in men only, and the other 4 included 14–19% women. That small number of women in statin trials limited conclusions for women and led to questions about the extrapolation of the data to women. LaRosa and colleagues (1999) conducted a meta-analysis of data from those trials and concluded that the risk reduction from statins is similar in men and women. 2 Meta-analyses, however, are not optimal, especially when evaluating the leading cause of mortality in women, and more recently the efficacy and safety of statins, especially for primary prevention, has been questioned and is still being evaluated (Abramson and Wright, 2007; Mascitelli and Pezzetta, 2007; McPherson and Kavaslar, 2007; Ridker, 2010).

Before 1987, women were underrepresented in key randomized controlled trials because of policies that limited or prevented their participation mainly owing to concern about potential exposures of fetuses. Changes in National In stitutes of Health (NIH) and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations and policies, starting in 1987, addressed that underrepresentation and aimed to increase the enrollment of women and analysis of data on women in clinical trials (GAO, 1992, 2000; Merkatz and Junod, 1994). Progress has been made since then in increasing enrollment of women. Women made up 51.7% and 60.0% of participants in NIH extramural and intramural clinical research in 1995 and 2008, respectively (HHS, 2009). The highest percentage, 64.2%, was seen in 2002; that corresponds to when large women-only studies related to breast cancer, menopause, and cardiovascular diseases (the WHS, the WHI, and SWAN) were conducted (HHS, 2009). The sex distribution in all the minority-group participants in 2008 was similar to that in the nonminority population; women made up 59.15% of minority-group participants (HHS, 2009). 3

Data from clinical trials that looked at specific end points have provided additional insight into the participation of women and minorities. A recent analysis of FDA clinical trials found that although the number of trials enrolling women and the proportion of participants who are female participating in phase I trials have increased since 2001, women are still underrepresented (Pinnow et al., 2009). Stewart and colleagues (2007) found higher enrollments of women than of men in their study of cooperative group surgical oncology trials, primarily because of the large number of breast-cancer trials. Members of racial and ethnic minorities and older persons were less likely to be enrolled in the trials than were whites and younger subjects.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) research historically has had low representation of women. Of the women who were eligible to participate in the largest cohort study of HIV-infected women in the United States (the Women’s Interagency HIV Study), about half would have been ineligible, on the basis of exclusion criteria, to participate in 20 of the AIDS Clinical Trials Group studies, which are among the largest HIV clinical-trial groups in the United States (Gandhi et al., 2005). Those results are consistent with an earlier meta-analysis published in abstract form that found that in 49 randomized controlled trials of antiretrovirals in 1990–2000, women averaged only 12.25% of the participants (Pardo et al., 2002).

In studies of cardiovascular disease, clinical-trial subjects have not been representative of the general population (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2001; Pedone and Lapane, 2003); one study discussed the predominance of men in cardiovascular trials (Sharpe, 2002). In 19 randomized controlled trials open to both men and women that examined myocardial infarction, stroke, or death, the mean percentage of female subjects was only 27%. 4 Only 13 of those studies presented sex-based analyses (Kim and Menon, 2009). A review of the literature by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality indicated that studies of coronary heart disease rarely included women in adequate numbers for analysis of the data by sex (Grady et al., 2003).

Part of the reason for the low participation of women is that many cardiovascular-disease clinical trials had inclusion criteria that were more appropriate for men than for women (Grady et al., 2003). Such inclusion criteria as early age of onset of myocardial infarction and chest pain as a presenting symptom will favor enrollment of men because women are on the average older at disease onset, are less likely than men to report chest pain during a heart attack, and are more likely to report other symptoms (Bairey Merz et al., 2006; Canto et al., 2007).

Even when women are included in clinical trials, having too few of them can be a barrier to obtaining statistically significant results related to women. Freedman and colleagues (1995) suggested conducting large clinical trials for conditions in which there is a priori evidence of sex differences. The NIH guidelines require inclusion of women and minorities in phase III clinical trials unless there is substantial evidence that sex differences do not exist (Bennett and the Board on Health Sciences Policy of the Institute of Medicine, 1993; Freedman et al., 1995). That implies that earlier research—including cells, animals, and phase I and II clinical trials—must have addressed potential sex differences sufficiently to support a choice not to include women in phase III clinical trials in numbers adequate for assessing sex differences. Underrepresentation of women in earlier phases could lead to interventions or treatments that are less effective or more toxic in women. For example, dose regimens are determined in phase I clinical trials, and conducting such studies mostly in men would result in drug doses based on male anatomy (Chen et al., 2000). Data indicate that women continue to be underrepresented in trials. For example, Jagsi (2009) found that women comprised only 38.8% of participants in non–sex-specific prospective clinical studies.

Because women might not be included in studies in adequate numbers to obtain a valid statistical analysis, another potential method of obtaining useful data on women is to perform meta-analysis of aggregated published data. That, however, requires that multiple studies be sufficiently similar in design (for example, having similar inclusion criteria and dosing regimens) and in clinical outcomes to be aggregated and also that the studies provide data on women separately (Berlin and Ellenberg, 2009). However, most clinical trials do not publish results on key subgroups of interest. Even when results on subgroups are published, the data are typically presented in different ways among studies and difficult to combine in a meta-analysis (Berlin and Ellenberg, 2009).

Combining data on individual subjects from randomized trials is another approach for enhancing statistical power that increases the number of subjects available for analysis in clinical subgroups. Pooling of data on individual subjects overcomes the limitations of meta-analysis and allows use of more sensitive statistical methods, including analysis of survival times, multivariable models, and tests for treatment-by-covariate interactions (Samsa et al., 2005). It also enables the assessment of the combined effect of treatment for multiple end points—combining benefits and risks to capture net “value” (Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration, 2009). However, the technique poses logistical challenges and requires collaboration among trial groups and support from funding agencies (Bravata et al., 2007).

A Bayesian approach could also be used to determine whether sex or gender differences exist, and that information could form the basis of further research. The Bayesian approach is an iterative one that adds more subjects from a subgroup on the basis of probabilities estimated from previous or preliminary results (Berry, 2006). In Bayesian analysis, the effect in a small number of women could be compared with the effect in a larger sample of men (or vice versa). If the distribution of results for several outcomes is the same between the sexes or genders, the study can proceed and continue to include a small number of women and to conduct periodic analyses to determine whether sex or gender differences are evident. If the distributions are different, the next phase of the clinical trial would incorporate larger numbers of women to assess the differences. This method could be applied to individual and pooled trials.

An alternative to executing clinical trials with women and men and analyzing sex- or gender-specific data is to conduct women-only studies, particularly in cases in which there are gaps in knowledge about women. That has been done in a few men-only studies that demonstrated the benefit of a drug. For example, the original Physicians Health Study was a randomized controlled trial in men that found that daily aspirin led to a significant reduction in myocardial infarction but not in cardiovascular death (Hennekens and Buring, 1989; Hennekens and Eberlein, 1985). It was not known whether the results would be the same in women. Later the women-only WHS had slightly different results: daily aspirin lowered the risk of stroke but did not affect the risk of myocardial infarction or cardiovascular death (Ridker et al., 2005). Sex differences were then examined in a study that pooled individual-level data from 6 primary-prevention randomized trials and 16 secondary-prevention randomized trials (looking for prevention after a coronary event), including both the sex-specific trials discussed above. No sex differences in the effect of aspirin on overall serious cardiovascular events were seen, and the risk of cardiovascular events was reduced in both men and women. However, there were slight sex differences in aspirin’s value in primary prevention (depending on the statistical analysis): less primary prevention of major coronary events and more primary prevention of strokes were seen in women than in men. No sex differences were seen in secondary prevention of either end point—aspirin was protective in both sexes (Antithrombotic Trialists Collaboration, 2009). Overall, the authors concluded that aspirin is beneficial for protecting against secondary events in both women and men but that protection against primary events needs to be weighed against the risks posed by daily aspirin for both sexes.

- OUTCOME MEASURES

Female-Appropriate End Points

Sex and gender differences need to be considered not only for inclusion and exclusion criteria but also when determining the end points to be studied. If study end points are based on male pathophysiology, clinical outcomes relevant to women will be missed. For example, women are more likely to have unstable angina (DeCara, 2003), unrecognized myocardial infarction (Sheifer et al., 2001), and stroke as cardiovascular outcomes than men (Lloyd-Jones et al., 2009; Tow-fighi et al., 2007). If a clinical trial looking at a cardiovascular-disease treatment assesses fatal and nonfatal myocardial infarction as its outcome but does not assess such events as unstable angina that are more common in women, it will underestimate the prevalence of cardiovascular disease in women and be biased against finding a treatment effect in women.

Quality of Life as an End Point

Incidence and 5-year survival rates are often the end points evaluated in clinical trials, including studies of women’s health; fewer studies assess morbidity or health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) end points. The focus of research on mortality is also reflected in the relative lack of attention paid to conditions associated more closely with morbidity than with mortality, such as autoimmune disease, thyroid disease, and nonmalignant gynecologic disorders. Many of those chronic disabling disorders and depressive and anxiety disorders affect women more than men (Rieker and Bird, 2005), and women, when surveyed, generally report worse health than men even though men have shorter life expectancy and lower age of onset of such diseases as cardiovascular disease (Rieker and Bird, 2005). In addition, women rank quality-of-life end points high when considering what aspects of health matter to them, and this points to the need to assess HRQoL end points in women (Fryback et al., 2007).

One challenge in including HRQoL end points in studies is the need for consistent and accurate metrics for them. In particular for women’s health, including metrics that measure what matters to women is important. Metrics for HRQoL end points have been developed as interest in assessing them in observational studies, clinical trials, and health-services research has increased. Measures of HRQoL end points can reflect specific symptoms, constellations of symptoms associated with specific conditions, or the combined effects on overall well-being that reflect symptoms that affect HRQoL (that is, quantify a global measure of quality of life) (Gold et al., 2002). HRQoL metrics, such as the SF-36 , which is a short-form health survey with 36 questions, quantify quality of life in terms of domains (for example, physical, psychologic, economic, spiritual, and social) and allow comparisons among conditions, but some may lack sensitivity to sex- and gender-specific issues (such as menopause and premenstrual-syndrome symptoms), and some are affected by sex and gender (Fleishman and Lawrence, 2003). Research is beginning to identify and improve understanding of those differences to capture quality-of-life end points for women better (Fryback et al., 2007). Improved measures of HRQoL in women will help not only in assessing women’s health but in communicating risks and benefits associated with treatment and intervention options to women and to facilitate informed decision making for female patients—an important aspect of translating research into practice, which is discussed further in Chapter 5 .

Including adequate numbers of women in clinical trials is necessary but not sufficient to ensure that results are applicable to women. Despite improved inclusion of women in trials funded by NIH and reviewed by FDA, there has been a lag in the routine analysis and reporting of data by sex (GAO, 2000, 2001). Often there is no mention of separate male and female analysis in publications, and it is not possible to know whether an analysis by sex was not conducted or was conducted but not reported, especially inasmuch as negative findings are often not reported. Many trials are designed to test an intervention, not to test whether the intervention is safe and effective in both men and women.

Another consideration is that the volume of health-research data is expanding, and new initiatives are underway to capture those data. The initiatives include developing a health-information-technology infrastructure and large databases, including the i2b2, the Cancer Biomedical Informatics Grid, improvement in the Medicare and Medicaid claims databases, and use of distributed data networks for an FDA sentinel system to detect adverse drug events (Bach et al., 2002; Kakazu et al., 2004; Murphy et al., 2006; Platt et al., 2009). If those technologies are to achieve their full potential in improving women’s health, the ability to capture and analyze sex- and gender-specific data needs to be considered during the design of such systems (Brittle and Bird, 2007; McKinley et al., 2002; Weisman, 2000). Additionally, data relevant to women’s health needs to be captured better in health-services research (for example, by using metrics of care quality specific to women) so that there can be more accurate measures of the translation of research findings into health-care services and delivery (Chou et al., 2007a,b; Correa-de-Araujo, 2004; NCQA, 2010).

METHODOLOGIC LESSONS FROM THE WOMEN’S HEALTH INITIATIVE

Much has been learned from the WHI about how to design women’s health research (see Appendix C for details of this study). The WHI, which is the largest clinical study done exclusively on women, was designed as a study of primary prevention of diseases of aging (coronary heart disease, breast and colorectal cancer, and hip and other fractures), but it also assessed other end points (stroke, venous and pulmonary emboli, ovarian and endometrial cancer, gall bladder disease, cognition, and death). A global index was developed as a summary measure of the effect of treatment for potentially life-threatening events (Resnick et al., 2006, 2009). The WHI consisted of an observational study that was designed to identify predictors of disease in women and a clinical trial that consisted of three randomized components (Anderson et al., 2003):

trials that evaluated the effects of the postmenopausal hormone therapy, conjugated equine estrogen (Premarin™) on heart disease, fractures, and breast and colorectal cancer in 10,739 postmenopausal women who did not have uteruses, or conjugated equine estrogen plus medroxyprogesterone (Prempro™) in 16,608 postmenopausal omen who had uteruses;

a trial that assessed whether a calcium and vitamin D supplement reduces the risk of colorectal cancer and the frequency of hip and other fractures in over 36,000 postmenopausal women; and

a trial that assessed the effects of a diet low in fat and high in fruits, vegetables, and grains on breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and heart disease in almost 49,000 postmenopausal women.