- Open access

- Published: 15 July 2023

Food taboos and animal conservation: a systematic review on how cultural expressions influence interaction with wildlife species

- André Santos Landim 1 ,

- Jeferson de Menezes Souza 2 ,

- Lucrécia Braz dos Santos 1 ,

- Ernani Machado de Freitas Lins-Neto 1 , 3 , 4 ,

- Daniel Tenório da Silva 1 &

- Felipe Silva Ferreira 1 , 3 , 5

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine volume 19 , Article number: 31 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2238 Accesses

1 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Human societies have food taboos as social rules that restrict access to a particular animal. Taboos are pointed out as tools for the conservation of animals, considering that the presence of this social rule prevents the consumption of animals. This work consists of a systematic review that aimed to verify how food taboos vary between different animal species, and how this relationship has influenced their conservation.

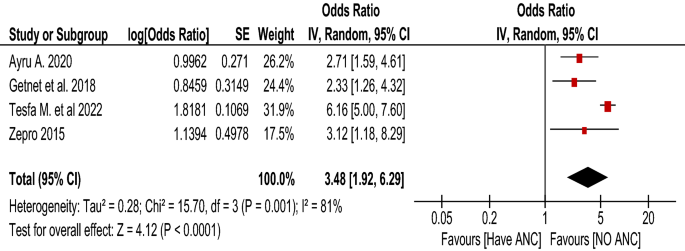

For this systematic review, the search for articles by keywords took place in the databases “Science Direct,” Scopus,” “SciELo” and “Web of Science,” associating the term “taboo” with the taxa “amphibians,” “birds,” “mammals,” “fish” and “reptiles.” From this search, 3959 titles were found related to the key terms of the research. After the entire screening process carried out by paired reviewers, only 25 articles were included in the search.

It was identified that 100 species of animals are related to some type of taboo, and segmental taboos and specific taboos were predominant, with 93 and 31 citations, respectively. In addition, the taxon with the most taboos recorded was fish, followed by mammals. Our findings indicate that the taboo protects 99% of the animal species mentioned, being a crucial tool for the conservation of these species.

Conclusions

The present study covered the status of current knowledge about food taboos associated with wildlife in the world. It is noticeable that taboos have a considerable effect on animal conservation, as the social restrictions imposed by taboos effectively contribute to the local conservation of species.

The process of eating is influenced by social, cultural and biological factors, leading human populations to select certain foods and avoid others. People recognize and classify foods for their nutrition, considering preferences that determine the intensity and frequency with which certain resources are consumed [ 1 , 2 , 3 ].

About dietary restrictions, taboos stand out as an important cultural element in several societies [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 ]. Food taboos are cultural elements that represent unwritten rules regulating human behavior toward certain resources, appearing in two forms: general taboos, which are imposed on an entire ethnic group making them never eat certain foods, and specific taboos, which are understood as temporary and interfere with a period of the individual's life, such as dietary restrictions at certain ages, in the face of illnesses and at certain times of life [ 8 , 9 ].

Food taboos act by preventing access to a particular food resource, and several characteristics are related to define a species as taboo. Animals may be avoided as food due to the presence of toxicity, parasites, fat content, position in the food chain they occupy, microhabitat and their conservation status [ 10 ]. In a case study in Brazil, it was found that the existing dietary restrictions among fishermen populations in the southeast region were related to the shape of the fish, its appearance, odor, behavior, conspicuous teeth, absence of scales, strong or heavy meat (called in Brazil “reimosa”), habit of eating slime and presence of blood [ 11 ].

Additionally, aspects related to the local availability of fauna (considering the richness and abundance of species) and access to other proteins are pointed out as motivators for the absence or presence of food taboos. The literature shows cases in which the food resource decreases, there is a tendency to make food taboos more flexible [ 4 , 9 ].

The presence of a food taboo in a human society brings a debate associated with fauna conservation. The defended hypothesis is that dietary restrictions result in adaptive strategies that contribute to the conservation and management of natural resources, above all, protecting some species of animals [ 12 ]. In this sense, the literature suggests that the presence of taboos directly contributes to the conservation of animal species [ 4 , 13 , 14 ]. However, there is a lack of studies that show whether in fact food taboos act as cultural elements that contribute to the conservation of fauna. Furthermore, there are gaps in knowledge about how food taboos behave in relation to taxonomic groups (birds, mammals, reptiles and amphibians), and how they appear in different regions of the planet.

Thus, the present study aimed to carry out a systematic review based on the following motivating questions: (1) Do food taboos influence fauna conservation? and (2) is there variation in the types of taboos between taxonomic groups and continents?

Material and methods

Research strategy and selection of studies.

The systematic review was performed based on the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions guideline and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) tool. Potentially relevant studies were identified through a search of Scopus, SciELO, Web of Science and Science Direct databases. The following research questions were used for this research: Do food taboos influence the conservation of wild species? and Do taboos influence fauna protection attitudes vary between taxonomic groups and continents?

As a search strategy, the standardized term “Taboo” was used, combined with terms related to animal taxa “Mammals,” “Reptiles,” “Amphibians,” “Birds” and “Fish,” linked by the Boolean operator “ and .” These terms are considered standardized because they were selected from consultations in the encyclopedia of controlled vocabularies in the “National Library of Medicines” through the “Medical Subject Headings” (MeSH) and in the VHL through the “Descriptors in Health Sciences” (DeCS). The search was performed using terms in English, Portuguese and Spanish. No time limit was used in the database search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies

Studies that met the following eligibility criteria were included in the review: (1) publication in English, Spanish or Portuguese; (2) object of study refers to animals with associated food taboo and (3) study points out whether the taboo associated with the animal leads to death or not of the species. Works were excluded: (1) unavailable in full; (2) abstracts published in conference proceedings; (3) letter to the editor; (4) literature review; (5) integrative review; (6) scoping review; (7) systematic review with or without meta-analysis; (8) systematic review overview with or without meta-analysis; (9) book chapter; (10) dissertations; (11) theses; (12) studies with imprecise results in reaction to taboos associated with species and (13) articles without the scientific name of the animal.

According to the eligibility criteria, the articles were selected according to the evaluation of the titles, followed by readings of the abstracts. If the article was appropriate, it was read in full. The selection was carried out by two researchers (paired review), called Reviewer 1 and Reviewer 2. In situations of disagreement between the reviewers, a third reviewer performed the tiebreaker.

The initial screening of articles found in the databases was performed using the EndNote software. x9 to exclude duplicate titles. Both the paired selection of titles and abstracts were performed using the Rayyan a software [ 15 ]. To verify the degree of agreement between the reviewers, the Kappa test was applied. The Kappa coefficient can be defined as a measure of association used to test the degree of agreement (reliability and precision) between evaluators [ 16 ]. The interpretation of the magnitude of the concordance estimators is agreed as: 0 (absent), 0–0.19 (poor/insignificant), 0.21–0.39 (fair), 0.40–0.59 (moderate), 0.60–0.79 (substantial) and ≥ 0.80 (almost perfect) [ 17 ]. Kappa test calculations were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software.

The tabulation of the data was performed in Microsoft® Excel®, registering the information of the articles such as author; year of publication; country; study design; duration of study; species name; gender; family; order and class and endemisms, and if food taboo leads to death or not.

Data analysis

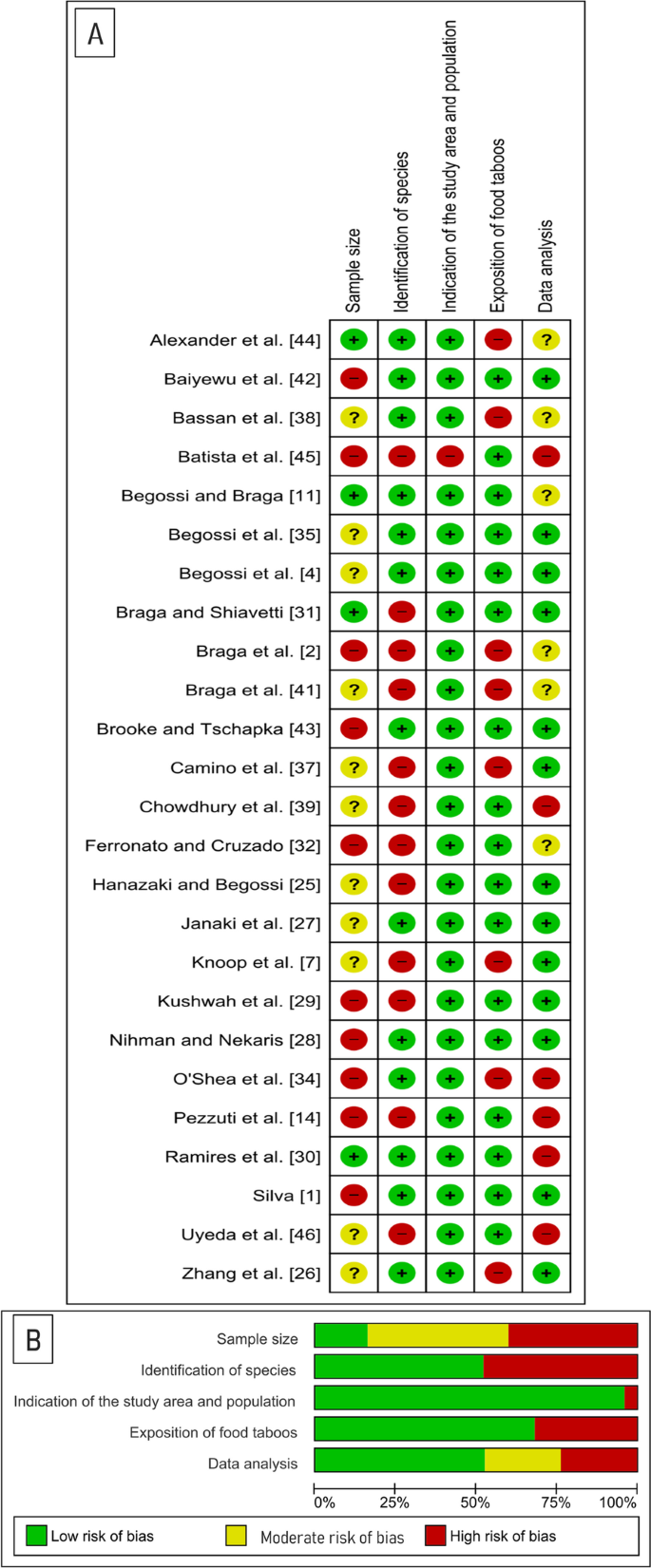

Data were analyzed qualitatively, taking into account the quality of the study, number of cited species, classification of taboos and classification of the species in relation to the threat of extinction according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature's (IUCN). The evaluation of the quality of the study was carried out through the analysis of the risk of bias in relation to: (1) sample size of the study, (2) indication of the area and population of the study, (3) species identification strategy, (4) data analysis and (5) exposure of food taboos (Table 1 ). Methodological quality assessment and risk of bias were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.4. [ 18 ].

The number of animals cited was recorded by simple counting, considering the number of times an animal is mentioned in different works. The number of species consists of the frequency in which a species appears, without considering repetitions. For example, if a species is cited by two works in different countries or not, we compute that the “Number of animals” is equal to two and the “Number of species” is one. For the classification of food taboos, the classification by Colding and Folke [ 19 , 47 ] was adopted, classifying them into “specific taboos,” “segmental taboos,” “method taboos,” “life history taboos,” “habitat taboos” and “time taboos.” It was also recorded whether the type of taboo was related to the death of the animal.

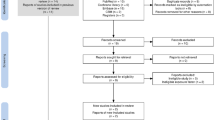

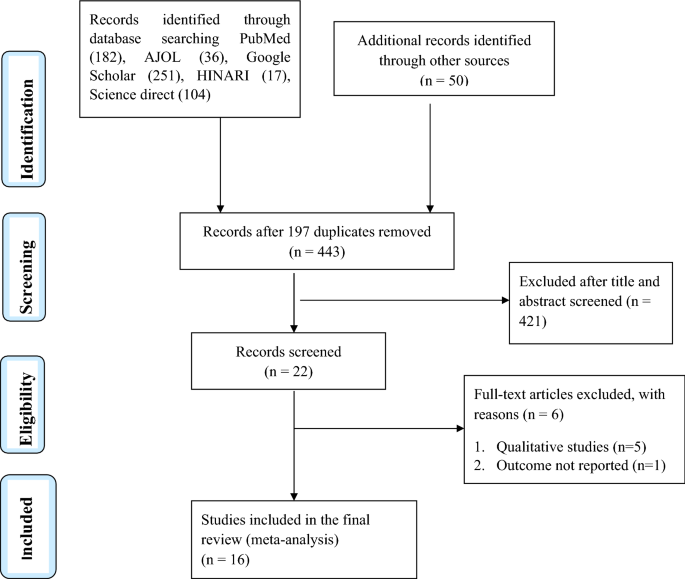

The search for articles in the databases returned a total of 46,117 titles related to the descriptors. A total of 12,705 articles were excluded for being duplicated, with 33,412 being included for title analysis. After reading the titles, a total of 29,453 articles were excluded because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. Of the 3959 remaining titles, 1362 studies were excluded, 448 because they dealt with taboos related to insects and 914 because they were not the object of study of this research.

Before selection by reading the abstracts, a third reviewer was asked to analyze the 2597 titles that passed the initial screening, 1817 articles being excluded. A total of 780 articles were included for reading the abstracts, 377 studies being excluded at this stage. A total of 403 articles were read in full, and 25 studies were included in this review (Fig. 1 , see Additional file 1 ).

Studies identified by searching the databases, based on Page et al. [ 49 ]

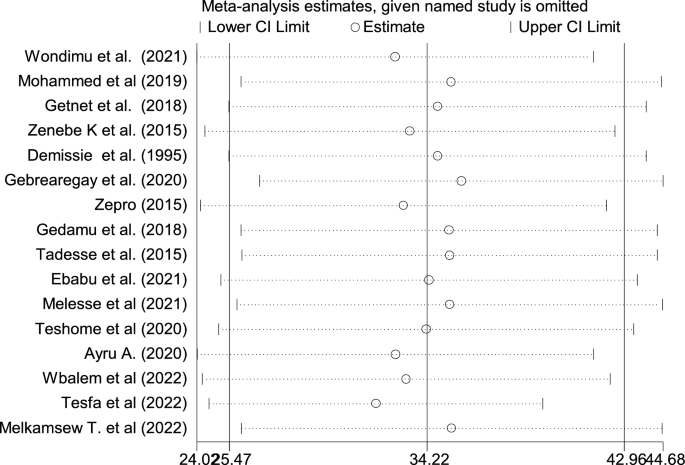

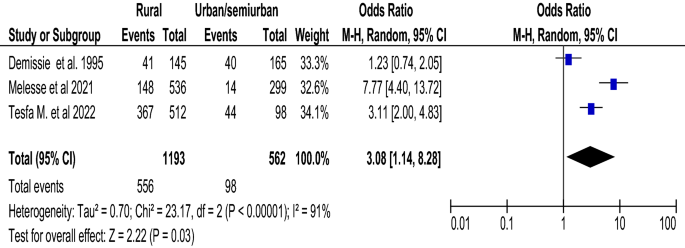

The Kappa test indicated a reasonable agreement in the analysis of the titles ( k = 0.309) and moderate agreement ( k = 0.438) in the selection by reading the abstracts. Regarding the risk of bias, it was identified that 16% of the studies showed low risk of bias, 44% moderate risk and 40% high risk of bias in relation to the sample size. Regarding the identification of species, 52% of the works used photographs of the animals, collected parts or whole animals, presenting a low risk of bias. A total of 96% presented a good characterization of the study area and population, with maps of the area, geographic coordinates and cultural context. For the discussion of taboos, 64% showed low risk of bias, and 24% of the studies showed high risk of bias or moderate risk of bias for data analysis (Fig. 2 ).

Authors' assessment of each risk of bias item for each scientific article included

A total of 130 animals distributed in 100 species were identified with some associated taboo. The species Pseudoplatystoma fasciatum , Hoplias malabaricus and Chelonoidis denticulatus presented the highest citation frequency, with four citations. It was registered that the taboo protects 99% of the registered species, avoiding the death of the animal. The only exception was the Pteropus tonganus present in Niue (Oceania), where a habitat taboo is associated with the death of the species. Regarding the taxonomic groups, fish had the greatest diversity of taboo species (44 species, average of five animals cited per study), followed by mammals ( n = 35); reptiles ( n = 16) and birds (five species) (Table 2 ).

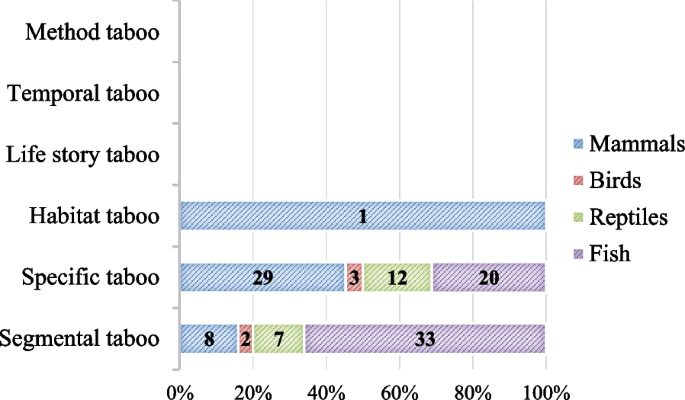

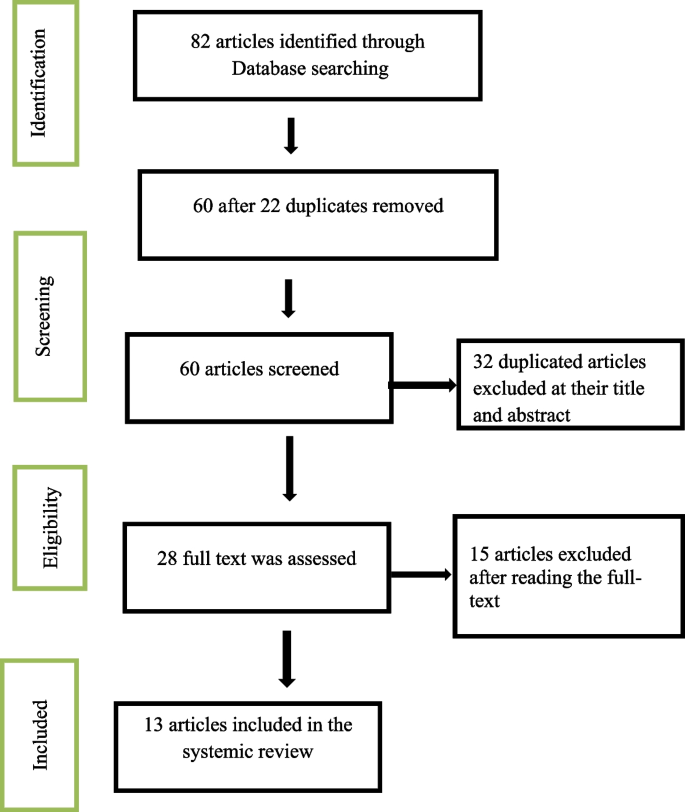

Considering the types of taboos, specific taboos ( n = 74) and segmental taboos ( n = 50) showed the highest frequency of animals; the habitat taboo had only one related mammal, and no animals related to the other types of food taboos were recorded (Fig. 3 ). All the specific and segmental taboos found did not cause the death of the animals. It was also found that the taxonomic category of fish had the highest frequency of segmental taboos, while the class of mammals had a predominance of specific taboos.

Number of food taboos by animal category

It was found that several motivations are pointed out for a species to be considered a food taboo; in this context, the registered species are avoided as food due to the characteristics of the meat (considered sweet, bad taste, unpleasant smell, high protein and fat), cultural beliefs (animals are totemic symbols, sacred, bring bad luck, they are gods), because they aggravate inflammation and cause irritation and for religious reasons.

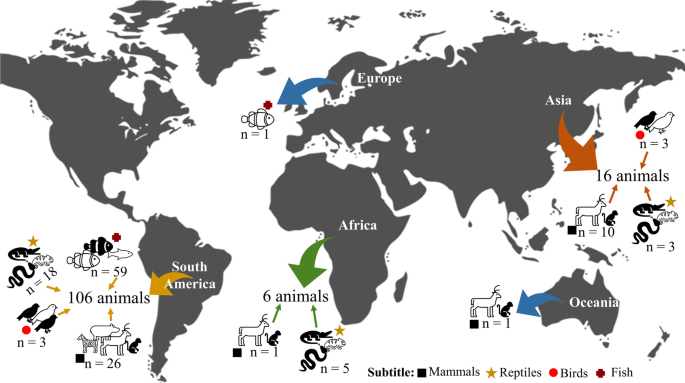

Analyzing by continent, South America was the continent with the highest number of animals ( n = 106) (birds: n = 3; mammals: n = 26; fish: n = 59 and reptiles: n = 18) mentioned with some type of taboo. None of the described taboos caused the death of animals in this continent. In Africa, only six animals were found, being distributed in the taxa of reptiles ( n = 5), mammals ( n = 1). Regarding the types of taboos in the African continent, only specific taboos were found for all animals. Asia recorded 16 taboo animals (birds = 3; mammals = 10 and reptiles = 3). In Europe and Oceania, only two species of animals were described in the studies, one species of fish (with segmental taboo) in the European continent and a mammal in Oceania, respectively (Fig. 4 ).

Distribution of taboo species by continent

The registered animals showed a low rate of endemism, with a total of eight species considered endemic, distributed among six fish ( Pinirampus pirinampu , Hoplias malabaricus and Cichla ocellaris , which are threatened with extinction, and Zungaro zungaro , Semaprochilodus brama and Hoplias brasiliensis which are least concern conservation status) and a bird ( Psophia viridis , vulnerable conservation status), recurrent in Brazil. Only one mammal is considered endemic ( Nycticebus javanicus , endangered), recurrent in Indonesia. The other species are of continental or cosmopolitan distribution.

As for the type of taboo, the South American continent presented the following types: specific taboo ( n = 17), segmental taboo ( n = 88) and habitat taboo ( n = 1). The class of fish and mammals has the highest number of animals listed by type of taboo, being predominant in the segmental taboo with 54 and 25 animals, respectively. In Asia, specific taboos predominated over the other types of taboos found with eight species in total, followed by segmental taboo ( n = 4) and habitat taboo ( n = 4). With respect to the conservation status of the species listed here, it was identified that one species ( Eretmochelys imbricata ) is critically endangered (CR) in terms of conservation status, and 21 are in a state of vulnerability (VU).

Our data indicate that 100 species of vertebrates are related to some type of taboo. Although the patterns of the taboo/species relationship are not clear, it is possible to identify that some animals are rejected as food due to characteristics of the meat, and it is pointed out that consuming some species can aggravate inflammatory processes. At this point, it is necessary to consider that taboos consist of unwritten or defined social rules, generally symbolizing something forbidden and untouchable, without necessarily having a rational explanation [ 20 ].

Observing the ecological aspect, the taboos behave like restrictions or rejections that govern attitudes and actions regarding a natural resource, constructed based on the human perception of a certain species. Consequently, species can be avoided because of their behavioral patterns, morphological characteristics, toxicity or simply because they are involved in myths and represent religious symbols, which are part of the cosmology of a population [ 8 , 21 ]. Examples of species such as Nycticebus javanicus , Funambulus pennantii , Pardofelis marmorata and Catopuma temminckii are related in Asia to ancestral relationships, totemic symbols and religious beliefs that protect these species against hunting [ 28 , 29 , 46 ].

It is important to understand how humans seek, obtain and choose food, as food choices can be influenced by individual preferences, ecological, economic, social and cultural factors, as well as dislikes [ 22 ]. In this situation, food taboos often limit the use of natural resources and, therefore, have important implications for biodiversity conservation [ 19 , 23 , 24 ].

It is noticeable that taboos are heterogeneously distributed among animal classes, this perspective is possibly related to selective pressures, which led human beings to interact differently with fish, birds and reptiles. About fish, the literature points out many species with an inflammatory potential for humans. It is possible that human populations have developed fish-related taboos to reduce the risks associated with potentially inflammatory foods [ 4 , 25 ]. Another point is that the rejection for consumption of certain species of fish happens due to the animal's eating conditions, as well as its morphology. For example, species such as poraquê ( Electrophorus electricus ) and the sarapo ( Sternarchorhynchus mormyrus ) are avoided by Brazilian communities because they are like snakes, so in the local perception, they may contain some toxicity [ 1 ].

About mammals, the ancestry between humans and other animals of this taxon may be a factor that influences behaviors that originate taboos. As humans recognize characters in common with other mammals, this may lead to dietary restrictions for animals with anthropomorphic characteristics. Traditional peoples of China tend to avoid the Gibbon ( Hoolock tianxing ) as food, due to the belief that the species is “ancestors of people” [ 26 ]; it is also found that indigenous peoples of India do not hunt or consume any primates, due to the belief that primates were their ancestors and, therefore, are religious symbols [ 27 ]. In this way, shared ancestry, religious symbols and the belief that the species causes or intensifies inflammation can make a species taboo [ 4 , 14 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ].

The taboos associated with reptiles and birds report situations of restriction to the meat of these animals due to sacred contexts or potential inflammation. Regarding reptiles, the emergence of taboos associated with these animals may be related to the feeling of fear. Most likely, humans' fear of reptiles is related to genes that arose in ancient lineages of mammals that were preyed on by snakes. Thus, the human feeling of fear is associated with these genes, possibly favoring the survival capacity of Homo sapiens against animals with some risk potential, such as snakes [ 50 , 51 , 52 ].

About the taboos related to birds, the human feeling about birds is directly associated with the beauty of these animals. Birds are seen by humans as beautiful animals due to their coloration [ 53 ]. Colors such as blue and yellow are seen, especially in birds, as elements that enhance beauty [ 54 ]. Possibly, this feeling influences a low number of birds used for food and, consequently, fewer food taboos. Additionally, the taboos assigned to birds that have been listed here are related to restrictions constructed by local sacred aspects. It is also necessary to consider that this taxon is directly linked to smuggling, in which several birds are sold in Brazil and in the world, causing birds to be incorporated into pet and trade categories [ 55 , 56 ].

Taboos can be classified in a utilitarian way, such as temporary (segmental) taboos that are restricted to certain periods of life, regulating the use of a resource according to age, gender, social condition and other specific conditions; and permanent (specific) that extend throughout life [ 19 ]. As for the variation in the types of taboos, the segmental taboos predominated in relation to the other types of taboos observed in the studies. Many of these segmental taboos are associated with the inflammatory potential of meat. These animals are known as “reimosos” in South America. The word “reima” comes from the Greek “rheum” which means “viscous fluid” and aims to classify the degree of safety of wild and domestic animals for consumption [ 1 ].

Creamy or “heavy” foods, for traditional populations, tend to provoke or aggravate inflammatory processes, tending to be avoided by people in physical states of liminality, initiated in some ritual, people with illnesses, menstrual period and postpartum [ 12 , 33 ]. In our study, we found 50 cases of taboos referring to “heavy animals,” many of which were described as “heavy meat” animals capable of causing infections, being foods to be avoided mainly by women during pregnancy, puerperium or menstruation. This perspective is recurrent in riverside communities in the Amazon (Basil), where some reptiles such as the Jabutis ( Peltocephalus dumerilianus ), ( Mesoclemmys raniceps ) and the jabuti-tinga ( Chelonoidis denticulatus ) are not eaten because they are oily, because they are “offensive to anyone eats,” causing “allergic reactions” [ 14 ]. Several other cases of segmental taboos are cited in this review [ 1 , 4 , 11 , 14 , 31 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 ]. These examples of segmental taboos point out how cultural factors and the phases of a person's natural life cycle can interfere in the dynamics of animal consumption in a community, and this instrument ends up being an important factor for the conservation of animal species.

Specific taboos are mostly related to religious factors and folk beliefs. In a case study, it is seen that the capture and consumption of primacy Nycticebus javanicus is prohibited because, according to villagers, taking and keeping this species in homes can bring unhappiness and bad luck [ 28 ]. On the other hand, in India, felines such as Capped Langur ( Trachypithecus pileatus ) , Asian golden cat (Catopuma temminckii ) , cat- marbled (Pardofelis marmorata ) and the tiger ( Panthera tigris ) are seen as animals that bring luck, because they are related to sacred institutions and cannot be hunted [ 27 ].

Habitat taboos are also considered a type of permanent taboo. This type of taboo was characterized by restrictions on hunting in places considered sacred. These places, because they are surrounded by symbology and spirituality, serve as a sanctuary for animals, thus being an important conservation factor. According to local beliefs, people who hunt in sacred places can suffer both divine and popular punishments [ 39 ]. Janaki et al. [ 27 ] point out that habitat taboos can help in the conservation of wild animals by providing refuges. Habitat taboos are recurrent in continents such as South America, Asia and Oceania, and these sacred reserves help government institutions to institutionalize places as biodiversity conservation areas, making them heritage protected by law.

The studies found are mostly from South America, reinforcing the perspective that this continent is one of the main scientific productions related to Ethnobiology [ 40 ]. It can be noticed that regarding taboo game species in South America, the vast majority of studies are focused on the fish group, with case studies being carried out with indigenous and riverside peoples, mainly in the Brazilian Amazon, in addition to caiçaras (mixture ethnocultural heritage of indigenous, European and African peoples) from the coastal portion of Brazil [ 1 , 2 , 4 , 11 , 25 , 30 , 38 ]. On the other hand, no studies were found that portrayed taboos associated with fish in Asia, Oceania and Africa. And only one study was found in Europe [ 41 ].

The greatest restriction for fish consumption in South America was due to the potential to cause inflammation, the feeding habits of these animals, in addition to the morphological similarities with snakes for some species [ 4 , 25 , 32 ]. In Asia, Africa, Oceania and Europe, it is noticeable that the taboos are similar, since most food restrictions are based on spirituality, where species, mainly mammals and reptiles, are prohibited so that the hunter/consumer does not suffer “punishments,” divine powers or punishments in their village/tribe [ 27 , 28 , 39 , 42 , 43 ].

By observing the behavior of taboos within the socioecological systems present in this review, it was found that food taboos have a positive effect on fauna conservation. This is because, even if unintentionally, the people involved end up acting in favor of the conservation of the species, either by restricting the consumption of “loaded” meat that can cause illness or by situations associated with the sacred place that can result in punishments for those who consume [ 14 , 27 , 43 ].

The literature directly discusses the effect of taboo on fauna conservation [ 13 , 21 ]. The compilation of data on taboos across the planet corroborates this perspective, as the data collected here show that food taboos have a positive effect on animal conservation, as of the 100 species listed under the effects of food taboos, 99 have taboos with positive effects for these species. These results show how taboos play a fundamental role in conservation and are often neglected by representations of formal institutions.

Analyzing the conservation status of the species listed here, we observe that the species classified as critically endangered (CR) in the IUCN list, as is the case of the hawksbill turtle ( Eretmochelys imbricata ) and the small primate the slow loris ( Nycticebus javanicus ) have taboos that reduce access by humans. We can presume that these species, without local taboos, could be susceptible to a decrease in population density in several regions of their occurrence [ 28 , 31 , 44 ].

However, it is important to consider the limitations of the effect of food taboos within a conservationist perspective [ 21 , 57 ]. Some species may present local taboos and have their consumption avoided, but form part of the diet of other human populations. For example, the present study shows that Tayassu pecari, Pecari tajacu and Nasua nasua have a record of food taboos in Brazil; however, it is used in food in different parts of northeastern Brazil [ 58 , 59 ]. Additionally, species such as Mazama americana, Mazama gouazoubira, Dasypus novemcinctus and Cuniculus paca have food taboos in Argentina but are preferred items in food in some locations in Brazil [ 55 , 59 ].

Considering that habitat loss (because of urbanization and agribusiness) [ 60 , 61 ] directly impacts wildlife, the existence of food taboos, even at the local level, plays an important role in conservation. If we consider that the food taboo has a local effect, the absence of these social rules could trigger greater pressure on certain species of animals, as their consumption would be widely spread. In this way, a species of animal avoided by a certain social group tends to have a higher population density at the local level, thus contributing to conservation. For example, in a study on sacred groves, it is demonstrated that the taboo of habitat serves to regulate the use of natural resources, being recognized by traditional communities as more efficient than areas of environmental protection [ 57 ]. Segmental taboos have also been identified as important wildlife managers, since they reduce the number of people who consume the resource [ 30 ].

The data collected here show that there are still few studies on food taboos and their consequences for preserving fauna. Thus, any strong conclusion about the role of taboos in conservation is still premature. However, it is possible to use these data and incorporate them into strategies to support fauna conservation. Taboos associated with the sacred are efficient mechanisms in the conservation of fauna. In a case study in Ghana (Africa), it is pointed out that among a community of turtles such as E. imbricata , Dermochelys coriacea, Lepidochelys olivaceae and Chelonia mydas are not hunted, due to local belief that these turtles were sighted saving ancestors of the population during a war against the Ashanti empire (an important ethnic group in Ghana). Therefore, residents of this village are prevented from consuming meat from these reptiles [ 44 ]. In the Brazilian Amazon, the taboo exerts a positive force (conservation) on species such as Tapirus terrestres , Tayassu fishermen , Fishermen steal and Ateles chamek which are avoided by indigenous peoples of the lower Madeira River, as they are considered to aggravate inflammation [ 7 ].

The consensus among studies is that animals considered taboo tend to be preserved, and this can positively impact the population dynamics of these species. It is estimated that the existence of taboos can reduce the pressure exerted on some species by up to 80%, since taboos reduce the number of people sharing the resource [ 4 , 13 , 14 ]. At this point, it was identified that only one work points to a negative relationship of taboos associated with wild species; it was found that in Oceania, flying fox hunting ( Tongan priest ) is intensified, due to the belief that the population of this species is infinite within a sacred area, so hunting the species in other areas does not impact the population of the animal [ 43 ].

Considering the types of taboos, it is observed that the specific and habitat taboos, as they are permanent, contribute to the formulation of laws and other regulations to prevent the hunting of different species of animals [ 57 ], showing the importance of the taboo even for formal institutions as technical and legal mechanisms for the conservation of species, corroborating the study by Nijman and Nekaris [ 28 ], which points out that species-specific taboos may have important ecological ramifications for the protection of threatened populations.

Final considerations

The present study covered the status of current knowledge about food taboos associated with wildlife in the world. It is noticeable that taboos have a considerable effect on animal conservation, as the social restrictions imposed by taboos effectively contribute to the local conservation of species. Even considering the importance of taboos for socio-biodiversity, there are still crucial gaps on this topic, showing that the topic “food taboo” is often neglected or little explored within socio-ecological systems.

From this study, it is evident the need to develop research to elucidate the mechanisms that favored the emergence of taboos. Undoubtedly, investigating human evolutionary history and foraging in the environment is an interesting way to identify what favored the emergence of taboos. Additionally, food taboos are important for maintaining the population of species on different continents. It is also important to emphasize that due to the inclusion and exclusion criteria of this research, data on other species and types of food taboos have been subtracted, so the number of species under the effects of food taboos may be even greater.

In this way, we point out that new studies should be designed to include objectives and metrics to analyze food taboos, seeking to understand how taboos arise and remain qualitatively and quantitatively within human populations. We also indicate that considering food taboos in environmental management plans can contribute significantly to the conservation of certain species.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Silva AL. Comida de gente: preferências e tabus alimentares entre os ribeirinhos do Médio Rio Negro (Amazonas, Brasil). J Anthropol. 2007. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-77012007000100004 .

Article Google Scholar

Braga TMP, Silva AA, Rebêlo GH. Preferências e tabus alimentares no consumo de pescado em Santarém, Brasil. Novos Cadernos NAEA. 2016;19(3):189–204. https://doi.org/10.5801/ncn.v19i3.2528 .

Chaves WA, Silva FPC, Constantino PAL, Brasil MVS, Drumond PM. A caça e a conservação da fauna silvestre no estado do Acre. Braz Biodivers. 2018;8(2):130–45.

Google Scholar

Begossi A, Hanazaki N, Ramos RM. Food chain and the reasons for fish food taboos among Amazonian and Atlantic forest fishers (Brazil). Ecol Appl. 2004;14:1334–43. https://doi.org/10.1890/03-5072 .

Vliet ND, L’haridon L, Gomez J, Vanegas L, Sandrin F, Nasi R. The use of traditional ecological knowledge in the context of participatory wildlife management: examples from indigenous communities in Puerto Nariño, Amazonas-Colombia. Ethnozoology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809913-1.00026-0 .

Nijhawan S, Mihu A. Relations of blood: hunting taboos and wildlife conservation in the Idu Mishmi of Northeast India. J Ethnobiol. 2020;40:149–66. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-40.2.149 .

Knoop SB, Morcatty TQ, Bizri HRE, Cheyne SM. Age, religion, and taboos influence subsistence hunting by indigenous people of the Lower Madeira River, Brazilian Amazon. J Ethnobiol. 2020;40:131–48. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-40.2.131 .

Colding J, Folke C. The relations among threatened species, their protection, and taboos. Conserv Ecol. 1997;1.

Prado DP, Zeineddin GC, Vieira MC, Barrella W, Ramires M. Preferences, food taboos and medicinal use of fish in the Barra do Una sustainable development reserve, São Paulo. Ethnoscientia. 2017. https://doi.org/10.18542/ethnoscientia.v2i1.10189 .

Barboza RSL, Barboza MSL, Pezzuti JCB. Cultural aspects of zootherapy and feed diet of artisanal fishermen of the Paraense coast. Fragm Cult. 2014;24:253–66. https://doi.org/10.18224/frag.v24i2.3309 .

Begossi A, Braga FMS. Food taboos and folk medicine among fishermen from the Tocantins River (Brazil). Amazonian. 1992;12:101–18.

Larrea-Killinger C, Freitas MCS, Rêgo CF. Reima: Proibição de alimentos em comunidades de pescadores na Bahia Brasil. Revista de Alimentação e Cultura das Américas. 2019;1(1):46–71.

Pezzuti JCB. Tabus alimentaires. In: Begossi A (ed) Ecology of fishermen in the Amazon and Atlantic Forest . Sao Paulo, Hucitec, 2004:167–86. https://doi.org/10.18542/papersnaea.v18i1.11382 .

Pezzuti JCB, Lima JP, Silva DF, Begossi A. Uses and taboos of turtles and tortoises along Rio Negro, Amazon Basin. J Ethnobiol. 2010;2010(30):153–68. https://doi.org/10.2993/0278-0771-30.1.153 .

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kotz S, Read CB, Balakrishnan C, Vidakovic B, Johnson NL. Encyclopedia of statistical sciences. New York: Wiley; 2004.

Book Google Scholar

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–74.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Deeks JJ, Higgins JP. Statistical algorithms in review manager 5. In: Statistical Methods Group of the Cochrane Collaboration. 2010:1–11.

Colding J, Folke C. Social taboos: “invisible” systems of local resource management and biological conservation. Ecol Appl. 2001;11:584–600. https://doi.org/10.2307/3060911 .

Ramalho RA, Saunders C. The role of nutrition education in combating nutritional deficiencies. Nutr Mag. 2000;13:11–6. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1415-52732000000100002 .

Pezzuti JCB. Hunting management and conservation of wild fauna with community participation. Pap do Naea. 2009;235:1–13.

Macbeth H, Lawry S. It is evident from the span of literature on the subject that the topic. In: Food preferences and taste: continuity and change. 1997;2.

McDonald DR. Food taboos: a primitive environmental protection agency (South America). Anthropos. 1977;6:734–48.

Redford KH, Robinson JG. The game of choice: patterns of Indian and colonist hunting in the Neotropics. Am Anthropol. 1987;89:650–67.

Hanazaki N, Begossi A. Catfish and mullets: the food preferences and taboos of Caiçaras (Southern Atlantic Forest Coast, Brazil). Interscience. 2006;31:123–9.

Zhang L, Guan Z, Fei H, Yan L, Turvey ST, Pengfei F. Influence of traditional ecological knowledge on conservation of the skywalker hoolock gibbon ( Hoolock tianxing ) outside nature reserves. Biol Conserv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108267 .

Janaki M, Pandit R, Sharma RK. The role of traditional belief systems in conserving biological diversity in the Eastern Himalaya Eco-region of India. Hum Dimens Wildl. 2021;26:13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/10871209.2020.1781982 .

Nijman V, Nekaris KAI. Traditions, taboos and trade in slow lorises in Sundanese communities in southern Java, Indonesia. Endanger Species Res. 2014;25:79–88. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr00610 .

Kushwah VS, Sisodia R, Bhatnagar C. Magico-religious and social belief of tribals of district Udaipur, Rajasthan. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0195-2 .

Ramires M, Rotundo MM, Begossi A. The use of fish in Ilhabela (São Paulo/Brazil): preferences, food taboos and medicinal indications. Biota Neotrop. 2012. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1676-06032012000100002 .

Braga HO, Schiavetti A. Attitudes and local ecological knowledge of experts fishermen in relation to conservation and bycatch of sea turtles (Reptilia: Testudines), Southern Bahia, Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2013;9:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-9-15 .

Ferronato BO, Cruzado G. Uses, beliefs, and conservation of turtles by the Ashaninka indigenous people, central Peru, Chelonian. Conserv Biol. 2013;12(2):308–13. https://doi.org/10.2744/CCB-1025.1 .

Murrietal RSS. The papa-chibé dilemma: food consumption, nutrition and intervention practices on Ituqui Island, lower Amazon, Pará. Anthropol J. 1998;41:97–150. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-77011998000100004 .

O’Sheat TJ, Strap-Viana M, Ludlow ME, Robinson JG. Distribution, status, and traditional significance of the West Indian Manatee Trichechus manatus in Venezuela. Biol Conserv. 1988;46:281–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(88)90030-4 .

Begossi A, Silvano R, do Amaral B, Oyakawa OT,. Uses of fish and game by inhabitants of an extractive reserve (Upper Juruá, Acre, Brazil). Environ Dev Sustain. 1999;1:73–93. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010075315060 .

Mmari MW, Kinyuru JN, Laswai HS, Okoth JK. Traditions, beliefs and indigenous technologies in connection with the edible longhorn grasshopper Ruspolia differens (Serville 1838) in Tanzania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0191-6 .

Camino M, Cortez S, Altrichter M, Matteucci SD. Relations with wildlife of Wichi and Criollo people of the Dry Chaco, a conservation perspective. Ethnobiol Conserv. 2018;7:1–21. https://doi.org/10.15451/ec2018-08-7.11-1-21 .

Bassan G, Moura PSD, Barrella W, Souza UP, Ramires M. Fishing resources used by the local community of Fernando de Noronha Archipelago (PE, Brazil): preferences, food taboos and medical use. Ecol South. 2020;24:869–77. https://doi.org/10.4257/oeco.2020.2404.10 .

Chowdhury MSH, Izumiyama S, Nazia N, Muhammed N, Koike M. Dietetic use of wild animals and traditional cultural beliefs in the Mro community of Bangladesh: an insight into biodiversity conservation. Biodiversity. 2014;15:23–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2014.893201 .

Alves RRN, Souto WMS. Ethnozoology in Brazil: current status and perspectives. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2011. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-7-22 .

Braga HO, Pardal MÂ, Azeiteiro UM. Sharing fishers’ ethnoecological knowledge of the European pilchard ( Sardina pilchardus ) in the westernmost fishing community in Europe. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2017;13:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-017-0181-8 .

Baiyewu A, Boakye MK, Kotzé A, Dalton DL, Jansen R. Ethnozoological survey of traditional uses of Temminck’s Ground Pangolin ( Smutsia temminckii ) in South Africa. Soc Anim. 2018;26:306–25. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341515 .

Brooke AP, Tschapka M. From overhunting to the flying fox, Pteropus tonganus , (Chiroptera: Pteropodidae) on Niue Island. S Pac Ocean Biol Conserv. 2002;103:343–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00145-8 .

Alexander LK, Agyekumhene A, Allman P. The role of taboos in the protection and recovery of sea turtles. Front Mar Sci. 2017. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2017.00237 .

Batista LPP, Botero JIS, de Paula EO, Silva EV. Ethnotaxonomy and food taboos of artisanal fishermen in Araras and Edson Queiroz dams, Acaraú River basin, Ceará, Brazil. Geogr Environ. 2016;12:34–49. https://doi.org/10.25100/eg.v0i12.3543 .

Uyeda LT, Iskandar E, Purbatrapsila A, Pamungas J, Wirsing A, Kyes RC. The role of traditional beliefs in the conservation of herpetofauna in Banten, Indonesia. Oryx. 2015;50:296–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605314000623 .

Colding J, Folke C. The taboo system: lessons about informal institutions for nature management. Georget Int Environ Law Rev. 1999;12:413.

Medeiros PM, Ladio AH, Albuquerque UP. Sampling problems in Brazilian research: a critical evaluation of studies on medicinal plants. Braz J Pharmacogn. 2014;24:103–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjp.2014.01.010 .

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CDD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Lim T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welhc VA, Whitings P. The PRISMA 2020 statement: updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Epidemiol Health Serv. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-49742022000200033 .

Landová E, Bakhshaliyeva N, Janovcová M, Peléskova S, Suleymanova M, Polák J, Guliev A, Frynta D. Association between fear and beauty evaluation of snakes: cross-cultural findings. Front Psychol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00333 .

Prokop P, Randler C. Biological predispositions and individual differences in human attitudes toward animals. Ethnozoology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809913-1.00023-5 .

Janovcová M, Rádlová S, Polák J, Sedlácková K, Peléskova S, Zampachová B, Frynta D, Landová E. Human attitude toward reptiles: a relationship bethween fear, disgust, and aesthetic preferences. Animals. 2019;9(5):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani9050238 .

Lisková S, Landová E, Frynta D. Human preferences for colorful birds: vivid colors or patter? Evol Psychol. 2015;13(2):339–59.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lisková S, Frynta D. What determines bird beauty in human eyes? Anthrozoös. 2013. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303713X13534238631399 .

Souza JM, LinsNeto EMF, Ferreira FS. Influence of the sociodemographic profile of hunters on the knowledge and use of faunistic resources. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-022-00538-4 .

Soares VMS, Soares HKL, Santos SS, Lucena RFP. Local knowledge, use, and conservation of wild birds in the semi-arid region of Paraíba state, northeastern Brazil. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2018;14(77):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-018-0276-x .

Talukdar S, Gupta A. Attitudes towards forest and wildlife, and conservation-oriented traditions, around Chakrashila Wildlife Sanctuary, Assam, India. Oryx. 2018;52:508–18. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605316001307 .

Almeida MCS, Silva-Ferreira F, Beltrão-Mendes R. Game mammals and their uses by local hunters in an Atlantic Forest region of Northeast Brazil. Rev Etnobiol. 2023;21(1):31–47.

Alves RRN, Feijó A, Barboza RRD, Souto WMS, Hugo F-F, Cordeiro-Estrela P, Langguth A. Game mammals of the Caatinga biome. Ethnobiol Conserv. 2016;5:1–51. https://doi.org/10.15451/ec2016-7-5.5-1-51 .

Silva MJB, Costa MF, Farias AS, Wanderley LSO. Wha is going to save the Brazilian Amazon forest? Reflections on deforestation, wildlife eviction, and stewardship behavior. Psychol Market. 2020;37(12):1720–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21418 .

Fidino P, Gallo T, Lehrer EW, Murray MH, Kay CAM, Sander HA, MacDougall B, Salsbury CM, Ryan TJ, Angstmann JL, Belaure JA, Dugelby B, Schell CJ, Stansowich T, Amaya M, Drake D, Hursh SH, Ahlers AA, Williamson J, Hartley LM, Zellmer AJ, Simon K, Magle SB. Landscape-scale differences among cities alter common species responses to urbanization. Ecol Appl. 2021;31(2):25. https://doi.org/10.1002/eap.2253 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001.

There was no funding for the development of the study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde e Biológicas, Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco (UNIVASF), Petrolina, Pernambuco, Brazil

André Santos Landim, Lucrécia Braz dos Santos, Ernani Machado de Freitas Lins-Neto, Daniel Tenório da Silva & Felipe Silva Ferreira

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biotecnologia, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (UEFS), Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil

Jeferson de Menezes Souza

Núcleo de Estudos de Conservação da Caatinga (NECC)/Colegiado de Ecologia, Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco (UNIVASF), Petrolina, Pernambuco, Brazil

Ernani Machado de Freitas Lins-Neto & Felipe Silva Ferreira

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia Humana e Gestão Socioambiental, Universidade Do Estado da Bahia (UNEB), Juazeiro, Bahia, Brazil

Ernani Machado de Freitas Lins-Neto

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia e Evolução, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana (UEFS), Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil

Felipe Silva Ferreira

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

ASL designed the study, performed the database searches, screened the studies and wrote the main text. JdMS carried out the selection of studies and carried out the review of the main text. LBdS carried out the selection of studies and organized the main results. EMdFLN performed the data and main text review. DTdS guided the construction of the protocol for searching the databases, and FSF guided all phases of the study. All authors have read and approved the current manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Felipe Silva Ferreira .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

. General information about articles involving “taboos” included in the systematic review

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Landim, A.S., de Menezes Souza, J., dos Santos, L.B. et al. Food taboos and animal conservation: a systematic review on how cultural expressions influence interaction with wildlife species. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 19 , 31 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-023-00600-9

Download citation

Received : 12 May 2023

Accepted : 23 June 2023

Published : 15 July 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13002-023-00600-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Conservation

- Dietary restrictions

- Sociocultural systems

- Wild animals

Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine

ISSN: 1746-4269

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 07 August 2019

Food taboos, health beliefs, and gender: understanding household food choice and nutrition in rural Tajikistan

- Katharine McNamara ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7951-5119 1 &

- Elizabeth Wood 1

Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition volume 38 , Article number: 17 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

77k Accesses

31 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Household nutrition is influenced by interactions between food security and local knowledge negotiated along multiple axes of power. Such processes are situated within political and economic systems from which structural inequalities are reproduced at local, national, and global scales. Health beliefs and food taboos are two manifestations that emerge within these processes that may contribute beneficial, benign, or detrimental health outcomes. This study explores the social dimensions of food taboos and health beliefs in rural Khatlon province, Tajikistan and their potential impact on household-level nutrition. Our analysis considers the current and historical and political context of Tajikistan, with particular attention directed towards evolving gender roles in the wake of mass out-migration of men from 1990 to the present. Considering the patrilieneal, patrilocal social system typical to Khatlon, focus group discussions were conducted with the primary decision-making groups of the household: in-married women, mothers-in-law, and men. During focus groups, participants discussed age- and gender-differentiated taboos that call for avoidance of several foods central to the Tajik diet during sensitive periods in the life cycle when micronutrient and energy requirements peak: infancy and early childhood (under 2 years of age), pregnancy, and lactation. Participants described dynamic and complex processes of knowledge sharing and food practices that challenge essentialist depictions of local knowledges. Our findings are useful for exploring entaglements of gender and health that play out across multiple spatial and temporal scales. While this study is situated in the context of nutrition and agriculture extension, we hope researchers and practitioners of diverse epistemologies will draw connections to diverse areas of inquiry and applications.

The recognition of good nutrition as a fundamental driver for sustained social, economic, and political development has led to global efforts to eradicate malnutrition [ 1 ]. These efforts have aided in reducing the prevalence of malnutrition worldwide; however, accessing safe, nutritious food in adequate quantities continues to be a struggle for approximately 815 million people across a variety of contexts, regardless of the GDP of their nation [ 2 ]. Spatial and temporal patterns of food distribution are heterogeneous, causing disproportionate levels of malnutrition among some groups of people [ 3 ]. Intersectional approaches to malnutrition can aid in considering the combined, complex interactions between health and the mutually constituting subjectivities that contribute to vulnerability: gender, age, ethnicity, and caste, among others [ 4 ]. In this article, we consider vulnerable groups those whose intersecting subjectivities convey greater susceptibility to malnutrition and severity of its effects (e.g., diarrhea, stunting, wasting), and face the greatest risk of long-term health consequences due to poor nutrition. We simultaneously explore the overlap of vulnerability and privilege as critical for engaging diverse agents of change who reflect a multitude of health experiences [ 5 ].

Malnutrition takes a variety of forms and is often expressed comorbidly alongside other health conditions. According to Soeters et al., malnutrition is “a subacute or chronic state of nutrition in which a combination of varying degrees of over- or undernutrition and inflammatory activity have led to a change in body composition and diminished function” ([ 6 ], p. 708). While the definition proposed by Soeters et al. guides our conceptualization of malnutrition, this article places particular emphasis on the implications of undernutrtion due to its pervasiveness within the study site: Khatlon Province, Tajikistan.

Tajikistan faces the highest rate of undernutrition in Central Asia with approximately 5% of children under the age of 5 years suffering from acute undernutrition (wasting), 30% from chronic undernutrition (stunting), and 11% from underweight [ 7 ]. Accessibility and availability of food is most concerning in rural areas of the country, where food insecurity is concentrated [ 7 ]. Khatlon province, a largely rural region located in southwest Tajikistan, is highly vulnerable to malnutrition due to the interaction of poverty, tough agroecological conditions, and high rates of male migration for work (38%) [ 8 ]. These factors are complicated by gender hegemonies, wherein gender expectations are performed, intertwine with, and are perpetuated within the broader socioecological system that dominate subaltern masculinities and femininities [ 4 , 9 ]. Ultimately, the dynamic between power, social systems, and complex food landscapes influences how much of what kind of food is consumed and by who .

Since the 1970s, development practice has largely targeted the immediate drivers of malnutrition through nutrition-specific interventions like micro- and macronutrient supplementation [ 10 ]. However, a growing body of research demonstrates that nutrition-specific programs are not sufficient to reach global targets as they fail to address the complex socioecological determinants of malnutrition relevant at multiple scales of intervention [ 11 , 12 ]. In response, nutrition research and practice increasingly emphasize the importance of the underlying determinants of malnutrition through nutrition-sensitive interventions [ 13 ]. Within the agriculture sector, such programs seek to influence the availability, accessibility, and diversity of food [ 12 ]. The agriculture extension system (AES) is considered particularly well-positioned to execute nutrition-sensitive efforts because of its close engagement with communities and families and potential to bridge multiple pathways to improved nutrition through local agro-food systems [ 11 , 14 ].

Tajikistan faces the challenge of developing effective strategies for nutrition-sensitive agriculture amidst a dearth of literature relevant to its geographic and cultural context. However, in combination with cases from Uzbekistan, a neighboring country that shares some sociocultural similarities and shared history with Tajikistan as a former Soviet state, this small body of work can help scholars and practitioners glean relevant points of entry into more comprehensive nutrition interventions. For example, in both Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, it is common for elderly parents to live in the home of their youngest son and his family in a multigenerational household [ 15 , 16 ]. Complex relations emerge within in this familial arrangement that are central to the decisions made around food production, food preparation, and diet. While the power dynamics in this context are diverse, the interaction of age and gender often situate young women and children at the low-end of intrahousehold hierarchies [ 17 ]. Relations between senior and junior women (e.g., between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law), widowed mother and son, husband and wife, and junior and senior men (e.g., between father and son) fluidly maintain a matrix of interacting hierarchal structures [ 15 ]. Relationships between mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law are particularly important to decision-making around food and strongly influence household nutrition [ 17 ].

Tajikistan has experienced continual demographic changes since the late 1990s, spurred by growing rates of male out-migration. Today, approximately 40% of the working-age population leave the country to pursue work abroad; The majority of migrating workers are men from rural areas [ 16 ]. Naturally, demographic transformations are accompanied by changes in gender relations and expectations at multiple levels of society. While gender in any context is multifaceted, encompassing a range of discursive and performative processes by which masculinities and femininities are (re)constructed (for example through labor and specialized knowledge) [ 18 ], rapid and ongoing changes to national and local demographics contribute additional complexity to local gender relations. Despite the need for flexible research methods to capture these interwoven interactions, categorical gender analysis—which interprets men and women as static groups—remains widespread in the health literature. Nowhere is this more apparent than in work that equates gender with women and the fundamental linkages between men’s and women’s health are overlooked (see [ 19 ]). Ultimately, such approaches risk framing health and gender as “women’s issues” and essentializing men and women as either the perpetrators or victims of hierarchical dynamics, respectively, despite variation within these fluid subjectivities [ 4 ]. A gender relations approach that is responsive to complex and changing interactions “not only within but across identities and analytic categories” ([ 4 ], p. 1676), is therefore crucial for understanding gender and health in the context of Tajikistan.

The research presented in this article builds on the findings of a previous investigation that explored how Tajik intrahousehold dynamics affect the allocation of food resources and, ultimately, nutrition (see [ 17 ]. At the request of local agriculture extensionists, we framed our “initial dive” into food-related decision-making practices with the purpose of identifying recommendations to target malnutrition through AES. Entering this investigation, we expected to observe similar patterns to those documented in other contexts with prominent malnutrition and similar intrahousehold hierarchies. However, we found that food taboos and health beliefs shaped intrahousehold dietary practices in unexpected ways—a pattern not reflected by other studies in Central Asia.

In the early-to-mid 1900s, early Anthropological endeavors on the subject of taboos conceptualized such practices as irrational, pseudo-science avoidances "which, in their simplest forms, are almost as instinctive as those of the lower animals" ([ 20 ], p. 14). Later, taboos were reinterpreted as instrumental, rational practices that regulate complex social systems [ 21 ]. Over the last decade, the trajectory of scholarly approaches has evolved towards complex, integrated visions wherein the socio-ecological functions of taboos are entangled with symbolism and spirituality, history and politics, and economic and environmental conditions [ 22 ]. In this article, we apply insights from contemporary inquiry into taboos (see Meyer-Rochow 2009, Golden and Comaroff 2015) in tandem with theoretical contributions from anthropology, geography, and masculinity studies to call attention to the specific ways that Tajik food taboos shape and are shaped by gendered experiences and knowledges around health.

According to Meyer-Rochow (2009), the word food taboo is used to describe the deliberate avoidance of a specific food item "for reasons other than simple dislike from food preferences" ([ 23 ], p. 2). In some cases, food taboos protect from health hazards [ 24 ], in others they facilitate environmental conservation or safeguard limited resources [ 22 , 25 ]. Thus, intimate connections between food taboos and social-ecological systems punctuate cultural practice [ 17 ]. Food taboos can indicate specialized knowledge of specific household members and the responsibilities and roles attached to certain subjectivities. In this way, both awareness and practice of taboos may be most aparent within sub-groups most involved in their preservation [ 18 ]. While food taboos are embedded within community health beliefs, the later reflects values associated with a given activity or practice. More specficially, health beliefs encompass a breadth of attitudes, perceptions, and values stemming from various sources of health-related knowledge. Another distinction lies in how health beliefs emerge and are preserved within a community. Taboos involve the co-evolution of practices within the fabric of social power structures. Health beliefs, in contrast, reflect diverse renderings of health concepts that may be important at both individual and group (e.g. household, community) levels; Thus, health beliefs are not necessarily tied to multigenerational knowledge-sharing. Health beliefs and food taboos are interconnected, however, within the unique social-ecological system of the context from which they emerge; For example, health beliefs may inform adaptive food restrictions. Finally, both concepts are flexible and respond to changes in environmental, political, and economic configurations [ 23 ].

As seen in other contexts, food taboos in Khatlon Province may reflect intrahousehold power dynamics along the axes of age and gender as social expectations performed through food practices. Building on the findings of our earlier work, we aim to explore how food security in Khatlon Province is mediated by taboos and health beliefs that govern dietary practices during critical points in the human life and along gendered subjectivities [ 25 ]. For example, young mothers and children experience increased nutrient and energy demands during pregnancy and lactation, and during the first 2 years of life, respectively. Thus, food restriction at these phases life can magnify the health impact of seasonal scarcity, crop failure, and other disturbances to the agro-food system on women and young children due to the interaction of social status and increased dietary requirements during “nutrient-expensive” stages of life [ 3 ]. Experiences of both women and men are crucial to understanding the determinants of household nutrition status. However, no regional study of household health has considered the position of men—much less their nutrition knowledge and practices—beyond their role as “head of household” or as the standard next to which women's health status is evaluted. In light of recent gendered demographic transformations and their role as a destabilizing force in the Tajik household [ 26 ], such considerations are necessary to capture the sociocultural nuances associated with diet and nutrition and the multiplicity of health effects incurred by all household members.

This article explores and characterizes the social dimmensions of food taboos and health beliefs in Khatlon Province and their potential impact on household nutrition by analyzing a subset of the data collected from the household decision-making study described above. We apply a gender relations approach by recognizing “gender dynamics and the circumstances under which they interact to influence health opportunities and constraints” ([ 9 ], p. 2); Analysis across gender categories is necessary to capture nuance within health and nutrition experiences. Our ultimate goal is to draw linkages between local knowledge and the evolving political, economic, and environmental context of Khatlon Province that came forward in the data as central to local adaptive strategies around health. We do this by presenting taboos as dynamic, flexible, and in a constant state of emergence in response to ongoing socioecological changes; the topics of shifting demographics, agricultural labor, and unspecific taboos are most salient in this respect. To our knowledge, no other studies have documented the critical role of food taboos and health beliefs in household nutrition and dietary practices in the Central Asian Region. By filling the void of locally relevant research on connections between gender dynamics and health, this study holds implications for nutrition-sensitive programs seeking to address the underlying causes of undernutrition.

A team from the University of Florida (UF) conducted this study in February 2017 in collaboration with partners from the Tajikistan Agrarian University (TAU) and the Feed the Future Tajikistan Agriculture and Water Activity (TAWA) project. Prior to data collection and participant recruitment, permission to conduct this research was granted by the Institutional Review Board II (IRB II) at the University of Florida. UF principal investigators (PIs) were experienced in qualitative methods and had extensive background in global public health and nutrition. Research assistants from UF and TAU were invaluable members of the research team and worked alongside PIs from data collection to analysis. All research assistants from UF were in the master’s in public health (MPH) program and were recruited based on their previous involvement in public health research alongside the PIs and interest in conducting nutrition-related research abroad. TAU research assistants were recommended by TAU faculty based on the focus of their graduate studies in agriculture extension and communication and their familiarity with the rural, agrarian context of Khatlon province. UF PIs provided training in qualitative research methods to research assistants from both universities before fieldwork was conducted. UF research assistants received training on focus group discussion (FGD) and interview methods, effective probing questions, and real-time note-taking strategies. TAU research assistants were trained in the same competencies with the addition of real-time oral and written translation and word-for-word translation and transcription of recorded data. Together, PIs and trained research assistants met with agriculture extension agents from TAWA—this organization refers to extension agents as “Extension Home Economists” (EHEs), we will use this terminology from this point on—to deliver training on FGD facilitation and to develop a data collection strategy to implement during FGDs that would involve collaboration between EHEs, research assistants, and PIs. Due to the EHEs’ familiarity with participants through their extension work, it was decided that EHEs would lead the FGDs with community members while support roles were filled by TAU research assistants (responsible for translating in real-time to UF researchers and asking probing questions) and UF research assistants and PIs (responsible for managing recordings, note taking, and posing probing questions for translation to TAU research assistants).

Content analysis forms the theoretical approach of this study and was chosen deliberately for two reasons: (1) the dearth of existing literature and theories within the context of interest and (2) our ultimate goal of describing and characterizing a phenomenon, in this case the intrahousehold dynamics that govern food-choice and practices in Khatlon Province. The use of content analysis was crucial to our inductive approach to data analysis through which codes, categories, and themes were directly drawn from the data [ 27 ].

Prior to conducting FGDs with community members, four key informant interviews (KIIs) were conducted with nutrition and maternal and child health specialists from the World Health Organization, UNICEF, German Corporation for International Cooperation, and a local health clinic in Khatlon Province to provide researchers with information on household food and nutrition-related practices within the region. KIIs also allowed researchers to gain insight into best practices for nutrition-related field work in Tajikistan, specifically Khatlon Province. Participants were purposively selected based on the in-country partners’ knowledge of organizations working on nutrition in the region. Following KIIs, the FGD instrument was tested in Yavon, a village within Khatlon province, among mothers with children under 10 years of age. The instrument was revised and adjusted for cultural competency.

FGDs took place in 12 villages across five districts in Khatlon Province (Shahrtuz, Jomi, Khuroson, Sarband, and Vakhsh), which were selected due to their location within USAID’s Feed the Future Zone of Influence and connection to ongoing extension work with EHEs. In 2014, TAWA EHEs established women’s groups in collaboration with the Women Entrepreneurship for Empowerment Project (WEEP), which seeks to provide leadership and skill-building activities related to agriculture and nutrition to women of reproductive age. Through their work with the WEEP women’s groups, EHEs have built strong working relationships and trust within those communities, making EHEs ideal facilitators of these discussions. FGDs were conducted among three target populations: in-married women, mothers-in-law, and men. These participant groups were chosen based on the patrilineal and patrilocal social organization of Tajik households. We defined the participant groups according to their relationship with the in-married women due to her central role in diet-related decisions. “Men” refers to the husbands of the in-married women or males in the same age cohort as men of marrying age. “Mothers-in-law” refers to mothers of the in-married women’s husband, or mothers of men of marrying age. Due to household hierarchies, key informants strongly recommended separating these three groups during FGDs for honest responses and to ensure full participation of each group member in the discussion. Based on this recommendation, data from two FGDs was excluded from our analysis because the groups included both in-married women and mothers-in-law. In these two cases, EHEs were unable to separate the in-married women from their mothers-in-law without risking household conflict. Thirteen homogenous FGDs were analyzed for the purposes of this study: seven FGDs with in-married women, four with mothers-in-law, and two with men. FGDs varied in size (from 5 to 12 participants), with fewer total male participants as compared to women due to the high rate of male migration for work and their subsequent absence in many villages. Both the number of FGDs conducted with men and the number of male participants in each FGD clearly reflect these trends.

Each FGD was conducted by an EHE of matching gender to the participants with a TAU and UF research assistant present. During the discussion, a TAU research assistant translated the discussion in real-time while one UF research assistant transcribed verbatim using a laptop and a second UF research assistant took notes and asked probing questions via the facilitator. All FGDs were recorded to capture any lost data and were later reviewed and compared to the transcripts by a TAU research assistant to ensure data quality. Due to the stigma of illiteracy, oral consent was collected in the participants’ native language: Tajik, Uzbek, or Russian. Before initiating the discussion, TAU students or EHEs read the consent agreement aloud in the local language. The theoretical approach of this study was reflected in the structure and style of the focus groups, which were framed with open-ended questions relating to dietary practices and household decision-making around food. Targeted probing questions based on respondents’ comments allowed for a participant-directed discussion. When discussions surrounding specific infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices arose in the FGDs, participants were asked to define the age at which those practices were exercised.

Transcripts from the 13 homogenous FGDs form the empirical basis of this study. Researchers and research assistants from UF carried out data analysis using the constant comparative method where coding and analysis take place simultaneously [ 28 ]. Intercoder reliability was strengthened by building consensus between coders through intensive group discussion to develop a coding framework. Analysis was organized using Excel, in which each code was defined concisely. Follow-up discussions between coders were continual throughout the data analysis process to continually check interpretive convergence. Once all data were coded using QSR International’s NVivo 11 software, segments of the transcripts were retrieved and consolidated into an Excel matrix organized by theme, subtheme, participant group, and interpretation. From this, researchers defined recurrent themes and patterns. Food taboos and misconceptions emerged as sub-categories nested within determinants of food choice . Following analysis, we recoded misconceptions as health beliefs to convey the legitimacy of local knowledge in shaping health practices. Due to the rich discussions by participants, researchers conducted an additional analysis of the data subset that related specifically to food taboos and health beliefs . This allowed researchers to develop a more nuanced understanding of food taboos and health beliefs as they relate to nutrition in Khatlon Province.

The findings presented here build on our previous work on the intersections of household decision-making and nutrition. Our analysis targets a subset of that data relating specifically to food taboos and health beliefs, two themes that arose as critical determinants of household decision-making around food in the preceding work. Discussions around food taboos and health beliefs arose organically from an open-ended question: “Are there foods you avoid eating? Why?” This question was intentionally gender-neutral and probing questions, similarly, did not use gendered pronouns. Several themes and subthemes emerged that characterize food taboos in Khatlon Province according to who the taboo affects and when. There were also several health beliefs that followed similar patterns, affecting certain individuals during specific phases of the life cycle. Finally, a small portion of food taboos were found to be unspecific (uninfluenced by gender or age). The themes developed during analysis are presented according to a life-cycle approach: (1) food taboos during pregnancy, (2) health beliefs around breast-feeding, (3) food taboos during infancy and childhood, and (4) food taboos unspecific to gender or stage in life.

Food taboos during pregnancy

Antenatal food taboos were pervasive across participant groups and villages. However, while men were aware of restrictive antenatal taboos, women (in-married women and mothers-in-law) provided reasoning to detail why those practices were necessary. From the perspective of in-married women and mothers-in-law, exclusion of certain foods was intended to protect and support maternal health. For example, a mother-in-law stated, “When they have morning sickness they cannot eat oily foods.” Restriction of oily foods is practiced early in pregnancy to reduce the likelihood and severity of morning sickness. However, one mother-in-law explained that intake of oily foods may be limited throughout pregnancy and that, in general, “ pregnant women don’t eat as much oily food.”

FGDs across participant groups pointed to a general restriction of carbohydrate consumption during pregnancy. Men voiced their awareness of this practice by noting specific high-carbohydrate staple foods that are not consumed by pregnant women. The foods mentioned by men included osh (a rice dish) and mantou (dumplings). Women noted a more comprehensive list of avoided foods, adding noodles, bread, other baked goods. One mother-in-law summarized this list as “foods with carbohydrates”. When asked why carbohydrates are restricted, women explained that “if you eat these kinds of foods or meals you will have difficulty during birth” (In-married woman). Participants from women’s FGDs explained that consumption of carbohydrates during pregnancy leads to excessive weight-gain and a risky delivery because high gestational weight gain (GWG) “makes [the] baby very big” (mother-in law). Pistachios and nuts, a high-fat food item, were also restricted from the diet for the same reason.

These food taboos may have emerged recently in Khatlon Province due to their reported connection to recommendations from local physicians. Mothers-in-law explained that “[pregnant women] are told [by doctors] not to eat pistachios and nuts because they think the babies will be fat”. This observation was supported in the FGDs with in-married women, one of who stated, “Doctors tell [pregnant women] not to eat nuts, noodles, bread, foods rich with carbohydrates and recommend to eat more fruits and juice.” Both quotes suggest women consider restriction of certain foods key to physician recommendations for the prenatal diet. In-married women additionally emphasized the importance of fruits and vegetables to maternal diets during their focus groups.

Health beliefs around breastfeeding