An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Uttley L, Scope A, Stevenson M, et al. Systematic review and economic modelling of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy among people with non-psychotic mental health disorders. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015 Mar. (Health Technology Assessment, No. 19.18.)

Systematic review and economic modelling of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy among people with non-psychotic mental health disorders.

Chapter 2 clinical effectiveness of art therapy: quantitative systematic review.

This chapter aims to provide an overview of the evidence examining the clinical effectiveness of art therapy in people with non-psychotic mental health disorders.

- Literature search methods

Bibliographic database searching

Comprehensive literature searches were used to inform the quantitative, qualitative and cost-effectiveness reviews. A search strategy was developed to identify reviews, RCTs, economic evaluations, qualitative research and all other study types relating to art therapy. Methodological search filters were applied where appropriate. No other search limitations were used and all databases were searched from inception to present. Searches were conducted from May to July 2013. The full search strategies can be found in Appendix 2 .

To ensure that the full breadth of literature for the non-psychotic population was included, it was pragmatic to search for all art therapy studies and then subsequently exclude studies manually (through the sifting process) that were conducted in people with a psychotic disorder or a disorder in which symptoms of psychosis were reported. It is therefore possible for the reviewer to view all potentially relevant records available and manually exclude studies of samples with psychotic disorders. This method of searching through the literature is in contrast to an approach that uses a search strategy listing all possible mental health disorders that are considered to be ‘non-psychotic’ in the search terms. The latter method may not retrieve all relevant studies from populations that are not indexed under the named mental health disorders.

In addition to the range of conditions covered by the population, the evidence from the studies being generated was frequently not a clear-cut diagnosed ‘mental health disorder’ and the populations retrieved were not the clinical populations of common mental health problems that were first anticipated. At this point in the study identification process it would have been easy to exclude any study that did not include patients with a clinically diagnosed mental health disorder. If this approach had been taken, there would have been three studies in the quantitative review. Instead a pragmatic approach was taken by identifying, including and describing the populations that art therapy is being studied in, with reference to targeting mental health symptoms (see Chapter 1 , Non-psychotic mental health population: definition ).

Databases searched

- MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed citations (OvidSP).

- EMBASE (OvidSP).

- Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (The Cochrane Library).

- Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library).

- Database of Abstracts of Review of Effects (The Cochrane Library).

- NHS Economic Evaluation Database (The Cochrane Library).

- Health Technology Assessment Database (The Cochrane Library).

- Science Citation Index (Web of Science via Web of Knowledge).

- Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science via Web of Knowledge).

- CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (EBSCO host ).

- PsycINFO (OvidSP).

- AMED: Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (OvidSP).

- ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ProQuest).

Sensitive keyword strategies using free-text and, where available, thesaurus terms using Boolean operators and database-specific syntax were developed to search the electronic databases. Date limits or language restrictions were not used on any database. All resources were searched from inception to May 2013.

Grey literature searching

A number of sources were searched to identify any relevant grey literature. Relevant grey literature or unpublished evidence would include reports and dissertations that report sufficient details of the methods and results of the study to permit quality assessment. Conference proceedings without a corresponding final report (published or unpublished) would not qualify for inclusion, as they are unlikely to contain sufficient information to permit quality assessment and can often be different to results published in the final report. 39 , 40

Sources searched

- NHS Evidence (Guidelines): www.evidence.nhs.uk/ .

- The BAAT: www.baat.org/index.html .

- UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database: public.ukcrn.org.uk/Search/Portfolio.aspx .

- National Research Register Archive: www.nihr.ac.uk/Pages/NRRArchive.aspx .

- Current Controlled Trials: www.controlled-trials.com/ .

- OpenGrey: www.opengrey.eu/ .

- Google Scholar: scholar.google.co.uk/ .

- Mind: www.mind.org.uk/ .

- International Art Therapy Organisation: www.internationalarttherapy.org/ .

- National Coalition of Arts Therapies Associations: www.nccata.org/ .

Additional search methods

A hand search of the International Journal of Art Therapy (formerly Inscape ) was conducted. The additional search methods of reference list checking and citation searching of the included studies were utilised. Other complementary search methods were considered such as pearl growing; however, because the search method employed was considered to be very inclusive, such additional methods were unlikely to generate additional relevant records.

- Review methods

Screening and eligibility

The operational sifting criteria (eligibility criteria) were defined and verified by two reviewers (LU and AS). Titles and abstracts of all records generated from the searches were scrutinised by one assessor and checked by a second assessor to identify studies for possible inclusion into the quantitative review. All studies identified for inclusion at abstract stage were obtained in full text for more detailed appraisal. Non-English studies were translated and included if relevant. For conference abstracts or clinical trial records without study data, authors were contacted via e-mail; however, no additional data were retrieved by contacting study authors. There was no exclusion on the basis of quality. If closer assessment of studies at full text indicated that eligible studies were not RCTs, then the studies were excluded. Agreement on inclusion, for 20% of the total search results ( n = 2015), was calculated at title/abstract sift demonstrating 0.93 agreement using the kappa statistic. If there was uncertainty regarding the inclusion of a study, the reviewers sought the opinion of the team members with the relevant clinical, methodological or subject expertise to guide the decision.

Accumulation of results

All references were accumulated in a database using Reference Manager Version 12 (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA), enabling studies to be retrieved in categories by keyword searches and duplicates to be removed.

Study appraisal

Two reviewers (LU and AS) performed data extraction independently for all included papers and discrepancies were resolved by discussion between reviewers. When necessary, authors of the studies were contacted for further information. Data were input into a data extraction template using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), which was designed for the purpose of this review and verified by two reviewers. Information related to study population, sample size, intervention, comparators, potential biases in the conduct of the trial, outcomes including adverse events, follow-up and methods of statistical analysis was abstracted from the published papers directly into the electronic data extraction spreadsheet.

The evidence generated from the comprehensive searches highlighted that the majority of research in art therapy is conducted by or with art therapists. This indicates potential researcher allegiance towards the intervention in that art therapists are likely to have a vested interest in the output of the study. For this reason it was deemed important to focus on the highest quality evidence available from the study literature. Trials that were non-randomised (i.e. in which the researcher was able to select and allocate participants to treatment arms) were considered to be too low in methodological rigour to be included in this review. The consequence of including data from non-randomised studies into the review is that the resulting data are biased and therefore not robust or sufficient to inform and contribute to the evidence base. 41 , 42 The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the quantitative review are shown in Figure 2 .

Eligibility criteria for the quantitative review.

Studies could be conducted in any setting, including primary, secondary, community based or inpatient.

Study selection was not limited by the number of sessions, and studies that provided the intervention in a single session were included.

Timing of outcome assessment

Post-treatment outcomes and outcomes at reported follow-up points were extracted and summarised when reported.

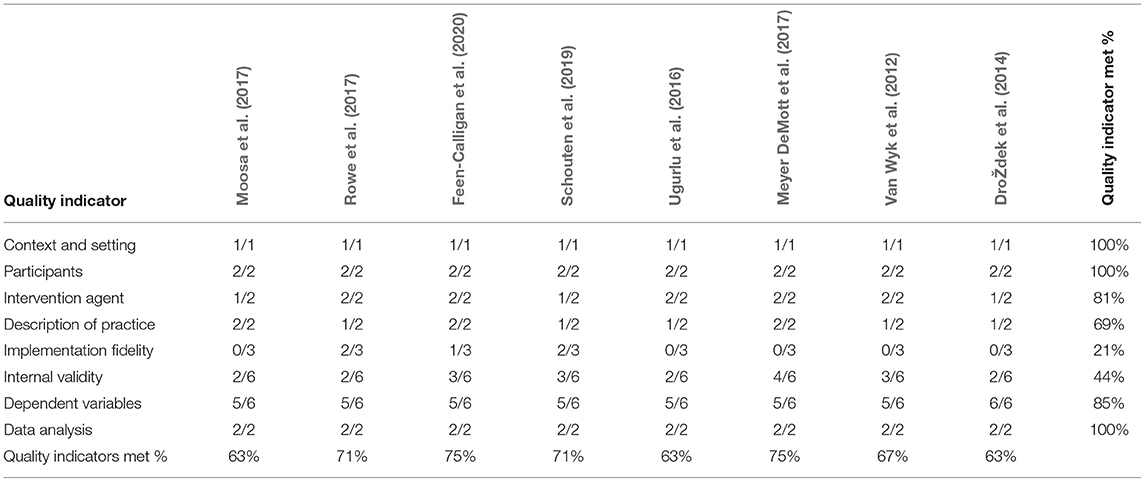

Quality assessment strategy

Quality assessment of included RCTs was performed for all studies independently by two reviewers using quality assessment criteria adapted from the Cochrane risk of bias, 44 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance 45 and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) 46 checklists to develop a modified tool for the purpose of this review. The modified tool was developed to incorporate relevant elements across several tools to allow comprehensive and relevant quality assessment for the included trials. Judgements and corresponding reasons for judgements for each quality criterion for all studies were stated explicitly and recorded. Risk of bias was assessed to be low, high or unclear. Where insufficient details were reported to make a judgement, risk of bias was stated to be unclear and authors were not contacted for further details. Discrepancies in judgements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers.

- Results of the quantitative review

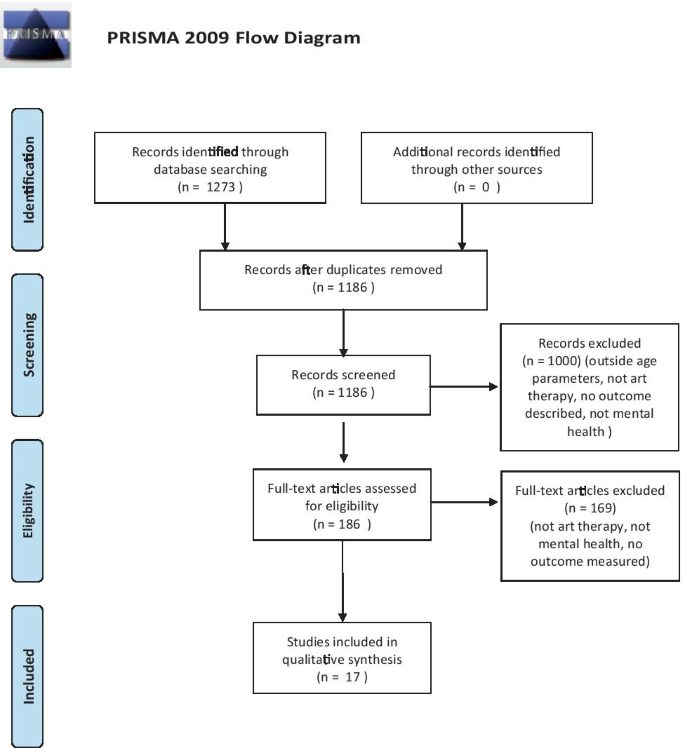

The total number of published articles yielded from electronic database searches after duplicates were removed was 10,073 (see Figure 3 ). An additional 197 records were identified from supplementary searches, resulting in a total of 10,270 records for screening. Of these, 10,221 records were excluded at title/abstract screening. Common reasons for exclusion from the review can be seen in Table 1 . A full list of the studies excluded from the quantitative review at full text stage (with reasons for exclusion) can be found in Appendix 3 .

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of studies included in the quantitative review.

Common reasons for exclusion from the review

The grey literature searches yielded very few potentially relevant records that were not generated by the electronic searches. One record appeared highly relevant to the research question and related to a clinical trial record of and RCT of art therapy in personality disorder (CREATe) for which the status was ‘ongoing’. However, e-mail contact with the primary investigator of this trial confirmed that the trial had been terminated because of poor recruitment.

- Included studies: quantitative review

Fifteen RCTs were identified for inclusion into the review which were reported in 18 sources (see Table 2 ). For clarity in this comparison, where a study with multiple sources is discussed only one of the sources has been noted.

Description of 15 included RCTs

Ten out of the 15 included studies were conducted in the USA, while only one study was conducted in the UK (see Tables 2 and 3 ). Eleven of the studies were conducted in adults (who are the primary focus of this review) and four were conducted in children. All trials had small final sample sizes with the number of participants reported to be included in each study ranging between 18 and 111. The mean sample size was 52.

Comparators across the 15 included studies

Three studies are of patients from the target population of people with non-psychotic mental disorders. 47 – 49 Of these three studies, only one was conducted in adults. 47

In the remaining 12 studies, the study population comprised individuals without a formal mental health diagnosis. 49 – 59 , 61 , 62 The populations in these studies are, therefore, mainly people with long-term medical conditions which are not reported to be accompanied by a mental health diagnosis; however, outcomes targeted in these studies were mental health symptoms.

The total number of patients in the included studies is 777. Nine studies compared art therapy with an active control group and six studies compared art therapy with a wait-list control or treatment as usual.

Two studies were reported to be conducted in an inpatient setting 48 , 49 and one study was conducted in prison. 59 The majority of studies were conducted in community/outpatient setting, although the precise setting for conducting the intervention was not reported in six studies. 50 , 52 , 54 – 56 , 61

Brief descriptions of the art therapy interventions are provided in Tables 4 and 5 .

Description of intervention and control in studies with active control

Description of intervention in studies with non-active control

Study duration ranged between the 15 studies from 1 session to 40 sessions, with a mean number of nine sessions (see Tables 4 and 5 ). Most studies with an active control group were of ‘group’ art therapy. One study which was a ‘brief’ intervention consisting of one individual session per participant. 56 Two studies did not state explicitly if sessions were in a group or individual. 47 , 53 Three studies with no active control were group art therapy 58 , 59 , 61 and three studies were individual art therapy. 49 , 55 , 62

The symptoms or outcome domains under investigation and associated outcome measures are reported in Table 6 .

Outcome domains under investigation in the 15 included RCTs

- Data synthesis

Heterogeneity of the included studies

The study populations are heterogeneous ( Figure 4 ), highlighting the wide application of art therapy in this small number of included RCTs but also demonstrating the difficulty in obtaining a pooled estimate of treatment effect. In this respect the clinical profile of patients can be regarded as a potential treatment effect modifier.

Patient clinical profiles in the 15 included RCTs.

The control groups across the included studies are heterogeneous ( Figure 5 ); therefore, there may be different estimates of treatment effects depending on what art therapy is compared against. Creating a network meta-analysis, which would incorporate all relevant evidence for all the comparators, for all non-psychotic mental health disorders, would be beyond the remit for this research project.

Comparator arms in the 15 included RCTs.

In addition, despite common mental health symptoms being investigated across the included RCTs, the majority of studies were using different measurement scales to assess these outcomes ( Table 7 ). Therefore, as there are insufficient comparable data on outcome measure across studies, it is not possible to perform a formal pooled analysis.

Instruments used in the 15 included RCTs

Potential treatment effect modifiers in the included studies

As well as the patient’s clinical profile, several other treatment effect modifiers can be identified from the included studies.

Experience/qualification of the art therapist

Twelve of the 15 included studies stated that the art therapy was delivered by one or more art therapists. One study was reported in three sources to use a ‘trained’ art therapist. 62 – 64 One study reported the art therapist as ‘licensed’. 56 Two studies reported using a ‘qualified’ art therapist. 48 , 57 Two studies reported using a ‘certified’ art therapist. 50 , 53 One study was reported in two sources as using a ‘registered’ art therapist. 60 , 61 One study reported using ‘experienced art psychotherapists’. 47 Four studies simply stated ‘art therapist’ without reference to accreditation. 49 , 52 , 58 , 59 One study stated that the sessions were run by one artist and two speech therapists. 51 One study stated that the sessions were run by two mental health counsellors. 55 One study did not state whether or not an art therapist was involved. 54 While there was considerable variability in the reporting of the accreditation of the therapist, most studies were conducted by a person who was considered to be qualified as an art therapist.

Individual versus group art therapy

The majority of RCTs are of group art therapy with only 4 of the 15 RCTs examining individual art therapy. 49 , 55 , 56 , 62

Eleven RCTs are of adults and four RCTs are of children or adolescents. 48 , 49 , 50 , 58

Five RCTs involved only women, 47 , 54 , 55 , 61 , 62 and one RCT only men. 59 In the remaining nine RCTs the subjects were of mixed gender.

Pre-existing physical condition

In nine studies patients had pre-existing physical conditions. 50 , 51 , 54 – 58 , 61 , 62 The remaining six studies involved people who were depressed, 47 , 59 people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) 48 , 49 or older people. 52 , 53

Other potential treatment effect modifiers which are not fully explored in the included RCTs include duration of disease (mental or physical), underlying reason for mental health disorder and patient preference for art therapy.

Owing to the degree of clinical heterogeneity across the studies and the lack of comparable data on outcome measures, meta-analysis was not appropriate. Therefore, the synthesis of data is limited to a narrative review to analyse the robustness of the data, which includes trial summaries as well as tabulation of results.

Study summaries

This section provides short overviews of each study with reference to statistically significant differences between groups that were reported in each of the studies.

Beebe et al. 2010 58

This was a RCT in children ( n = 22) with asthma of art therapy versus wait-list control. Sessions lasting 60 minutes were provided once a week for seven weeks. Outcomes were measured at baseline, immediately following completion of therapy and 6 months after the final session. Targeted variables were quality of life (QoL) and behavioural and emotional adaptation. Outcome measurement tools were the Paediatric QoL asthma module and Beck Youth Inventories. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett’s test. Compared with baseline scores, the intervention group showed a significant reduction in 4 out of 10 QoL items at 7 weeks and in 2 out of 10 QoL items at 6 months. Significant improvement relative to the control group was found in two out of five items of the Beck Youth Inventory at 7 weeks and in one out of five items at 6 months.

Broome et al. 2001 50

This was a three-arm RCT in children and adolescents ( n = 97) with sickle cell disease of art therapy versus CBT (relaxation for pain) or attention control (fun activities). Group sessions were provided over 4 weeks. Outcomes were measured at baseline and at 4 weeks and 12 months. The targeted variable was coping and the authors hypothesised that coping strategies would increase after attending a self-care intervention. Outcome measures were the Schoolagers’ Coping Strategies Inventory and Adolescent Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences scores and numbers of emergency room visits, clinic visits and hospital admissions. The number of coping strategies used was analysed at three time points using Pearson’s correlations, independent t -tests and ANOVA. Coping strategies increased in children and adolescents in all three groups, but data regarding the difference between the intervention and control groups were not reported.

Chapman et al. 2001 49

This RCT of brief art therapy versus treatment as usual was carried out in children ( n = 85) hospitalised with PTSD. A 1-hour individual session was provided but the number of sessions was not reported. Outcomes were measured at baseline and at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 and 12 months (in children who were still symptomatic). The targeted symptom was PTSD. The outcome measurement tool was Children’s Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Index (PTSD-I). The method of statistical analysis was not described. No significant differences were found between groups, but a non-significant trend towards greater reduction in PTSD-I scores was observed in the intervention group relative to the control group.

Gussak 2007 59

This was a RCT in incarcerated adult males ( n = 44) of art therapy versus no treatment. Eight weekly group sessions were provided. Outcomes were measured pre- and post-test (exact time points not reported). The targeted symptom was depression. The outcome measure was the Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form (BDI-II). The change in BDI-II scores from pre-test to post test was calculated and differences between groups analysed using independent-samples t -tests. Depression was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group post test.

Hattori et al. 2011 51

This was a RCT in Alzheimer disease ( n = 39) of art therapy versus a ‘simple calculation’ control group. Twelve 45-minute weekly sessions were provided (individual/group not reported). Outcomes were measured at baseline and at 12 weeks. Targeted variables were mood, vitality, behavioural impairment, QoL, activities of daily living and cognitive function. Outcome measures were the Mini Mental State Examination Score (MMSE), the Wechsler Memory Scale revised; the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS); the Apathy Scale (Japanese version); Short Form questionnaire-8 items (SF-8) – Physical (PCS-8) and Mental (MCS-8) components; the Barthel Index; the Dementia Behaviour Disturbance Scale; and the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview. Outcomes were measured at baseline and 12 weeks. The percentage of responders who showed a 10% or greater improvement relative to baseline score before the intervention was compared between groups using a chi-squared test. A significant improvement in the intervention group was seen in MCS-8 subscale of the SF-8 and the Apathy Scale. The control group showed a significant improvement in MMSE relative to the intervention group. No significant differences between groups in other items were reported.

Kim 2013 52

This RCT in older adults ( n = 50) compared art therapy with regular programme activities. Between 8 and 12 sessions lasting 60–75 minutes were provided over 4 weeks. Targeted variables were positive/negative affect, state–trait anxiety and self-esteem. Outcomes were measured using the Positive & Negative Affect Schedule, the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Time points for measurement were not reported (assumed 4 weeks). Independent group t -tests were performed to compare pre- and post-test scores between groups. Significant improvements in the intervention were seen in all three outcomes compared with the control group.

Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 2007 48

This RCT in adolescents ( n = 29) with PTSD compared art therapy with arts and crafts activities. Sixteen weekly group sessions were provided. The targeted symptom was PTSD. Outcome measurement tools were the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) PTSD Reaction Index ( Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition, Child Version) (primary measure) and milieu behavioural measures (e.g. use of restraints). Measurement time points were not reported, but data at two years were provided. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using repeated-measures ANOVA. The intervention was significantly better than control at reducing PTSD symptoms, according to the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index.

McCaffrey et al. 2011 53

This was a RCT in older adults ( n = 39) of art therapy versus garden walking (individual and group). Twelve 60-minute sessions (group/individual not reported) were provided over 6 weeks. The targeted symptom was depression. The outcome measurement tool was the GDS. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using repeated-measures ANOVA. Measurement was at baseline and 6 weeks. Depression significantly improved from baseline in all three groups with no significant differences between groups.

Monti and Peterson 2004; 60 Monti et al. 2006 61

This RCT in women with cancer ( n = 111) compared mindfulness-based art therapy with wait-list control. The trial was sized to have 80% power to detect a standardised effect size of 0.62. Eight 150-minute group sessions were provided over 8 weeks. Targeted variables were distress, depression, anxiety and QoL. Outcome measurement tools were the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), the Global Severity Index (GSI) and the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). Measurement was at baseline and at 8 weeks and 16 weeks. Pre-and post-test measures were compared between groups using mixed-effects repeated-measures ANOVA. A significant decrease in symptoms of distress and highly significant improvements in some areas of the QoL scale were observed in the intervention group compared with the control group.

Monti et al. 2012 54

This RCT of women with breast cancer ( n = 18) compared mindfulness-based art therapy with educational support (control group). Eight 150-minute weekly group sessions were provided. The targeted symptom was anxiety but the authors were interested in whether or not cerebral blood flow (CBF) correlated with experimental condition. The primary outcome measurement was functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) CBF and the correlation with anxiety using SCL-90-R. Measurement was at baseline and within 2 weeks of the end of the 8-week programme. The method of statistical analysis was not described and the effectiveness of the intervention was not the primary outcome. Anxiety was reduced in the intervention group but not in the control group. CBF on fMRI changed in certain brain areas in the art therapy group only. It should be noted that patients with a confirmed diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder were excluded from this study.

Puig et al. 2006 55

This was a RCT in women with breast cancer ( n = 39) of art therapy versus delayed treatment. Four 60-minute weekly sessions were provided. Targeted symptoms were anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, anxiety, activity and coping. The outcomes, the Profile of Mood States and the Emotional Approach Coping Scale (EACS) scores, were measured before and 2 weeks after the intervention. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using ANOVA. The intervention group showed significant improvements in the anger, confusion, depression and anxiety mood states but fatigue and activity were not significantly different between the groups. In the intervention group, EACS coping scores increased, but were not significantly different from those in the delayed treatment control group.

Rao et al. 2009 56

In this RCT in adults with HIV/AIDS ( n = 79), the intervention group received brief art therapy while the controls watched a video tape on the uses of art therapy. Only one 60-minute session of individual art therapy was provided. Targeted symptoms were anxiety and physical symptoms, including pain. The outcome measures used were Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) scores (primary outcome) and STAI scores. Pre-and post-test scores were compared between groups using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and adjusted for age, gender and ethnicity. Measurements were recorded before and immediately after the intervention or control session. The intervention group experienced significant improvements in physical symptoms (ESAS) compared with the control group, but anxiety was not significantly different between the groups.

Rusted et al. 2006 57

In this RCT in adults with dementia ( n = 45), art therapy was compared with an activity group control. Forty 60-minute weekly group sessions were provided. Targeted symptoms were depression, mood, sociability and physical involvement. Outcome measures were the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia the Multi Observational Scale for the Elderly, MMSE, The Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test, Tests of Everyday Attention and the Benton Fluency Task. Measurements were recorded at baseline, 10 weeks, 20 weeks, 40 weeks and at follow-up at 44 and 56 weeks. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using ANOVA with time of assessment as repeated measures. At 40 weeks, the intervention group was significantly more depressed than the control group, but this effect was reduced at follow-up. However, groups were not comparable at baseline, as the art therapy group were more depressed at the beginning of the study than the control group.

Thyme et al. 2007 47

This was a RCT in depressed female adults ( n = 39) of psychodynamic art therapy versus verbal dynamic psychotherapy. Ten 60-minute weekly sessions (individual/group not reported) were provided. Targeted symptoms were stress reactions after a range of traumatic events, mental health symptoms and depression. Outcome measurements were Impact of Event Scale, Symptom-Checklist-90 (SCL-90), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression scores. Measurements were recorded at baseline, at 10 weeks and at a 3-month follow-up. All patients improved from baseline on all scales ( p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between groups so art therapy was not significantly different to the comparator at either time point.

Thyme et al. 2009; 62 Svensk et al. 2009; 63 Oster et al. 2006 64

This RCT in women with breast cancer ( n = 41) compared art therapy with treatment as usual as a control. Five 60-minute weekly individual session were provided. Targeted symptoms were depression, anxiety, somatic, general symptoms, QoL and coping methods. Outcome measure tools were the Structural Analysis of Social Behavior, the GSI, the SCL-90, the World Health Organization (WHO) QoL instrument – Swedish version, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QoL Questionnaire-BR23 and the Coping Resources Inventory (CRI). Measurements were recorded at baseline and at 2 months and 6 months. The intervention significantly improved depressive, anxiety, somatic and general symptoms compared with the control. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using t -tests, ANOVA and linear regression. On the WHOQoL, scores on the overall, general health and environmental domains at 6 months were significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group. There were no significant differences between groups on the EORTC. In the intervention group, the score on only the ‘social’ dimension of the CRI was increased relative to the control group.

Findings of the included studies

The directions of statistically significant results from the 15 included RCTs are summarised in Table 8 .

Summary of the direction of findings from the 15 included studies

As can be seen in Table 8 , in 14 of the 15 included studies there were improvements from baseline in some outcomes in the art therapy groups. However, both the intervention and the control groups improved from baseline in four studies, with no significant difference between the groups. 47 , 49 , 50 , 53 The control groups across these four studies were verbal psychodynamic psychotherapy, 47 treatment as usual, 49 CBT 50 and garden walking, 53 and verbal psychodynamic psychotherapy, respectively.

In eight studies, art therapy was significantly better than the control group for some but not all outcome measures. Table 9 shows the results according to the mean change from baseline between groups in these eight studies.

Nine included studies with statistically significant findings in the art therapy group in some but not all outcome measures

In one study, 52 all outcomes were significantly better in the art therapy intervention group than in the control group. Table 10 shows the results from the Kim 52 study.

One included study with statistically positive findings for all outcomes in the art therapy group

In one study 57 of a sample of people with dementia, outcomes were worse for the art therapy group than for the control group, which was an activity control group. An unusual pattern of results is presented, including a significant increase in anxious/depressed mood ( p < 0.01) at 40 weeks which was not present at the 10- or 20-week time points and dissipated by 44 and 56 weeks. The authors discuss several reasons for this result including the high level of attrition; the reliance on observer ratings in the frail and elderly sample (and subsequent potential impact of observer bias); the increased depression as a response to the sessions ending; and the possibility that art therapy was contraindicated in this sample.

Narrative subgroup analysis of studies by mental health outcome domains

Table 11 presents the results for effectiveness of art therapy across relevant mental health outcome domains.

Effectiveness of art therapy across mental health outcome domains

Among the nine studies examining depression, 47 , 51 , 53 , 55 , 57 – 59 , 61 , 62 art therapy resulted in significant reduction in depression in six studies. 47 , 53 , 55 , 59 , 61 , 62 In four of these six studies, 55 , 59 , 61 , 62 art therapy was significantly more effective than the control. Data relating to significant differences are reported in Table 9 .

Among the seven studies examining anxiety, 52 , 54 – 56 , 58 , 61 , 62 art therapy resulted in significant reduction of anxiety in six studies. 52 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 61 , 62 In these six studies, art therapy was significantly more effective than the control. Data relating to significant differences are reported in Tables 8 and 9 .

Among the four studies examining mood or affect, 51 , 52 , 55 , 57 art therapy resulted in significant positive improvements to mood in three studies. 51 , 52 , 55 In these three studies, art therapy was significantly more effective than the control. Data relating to significant differences are reported in Tables 8 and 9 .

Among the three studies examining trauma, 47 – 49 art therapy resulted in significant reduction of symptoms of trauma in all studies. While trauma improved from baseline, there was no significant difference between the art therapy and control groups in any of the three studies.

Among the three studies examining distress, 47 , 61 , 62 art therapy resulted in significant reduction of distress in all studies. In two studies, 61 , 62 art therapy was significantly more effective than the control group. Data relating to significant differences are reported in Table 9 .

Quality of life

In the four studies examining QoL, 51 , 58 , 61 , 62 art therapy resulted in significant improvements to some but not all components of the QoL measures in all studies. In all studies, art therapy was significantly more effective than the control. Data relating to significant differences are reported in Table 9 .

Among the three studies examining coping, 50 , 55 , 62 art therapy resulted in significant improvements to coping resources in all studies. In one study, 62 art therapy was significantly more effective than the control. In another study, there was no difference between groups. 55 In the third study, significant differences between the art therapy and control groups were not reported. 50 Data relating to significant differences are reported in Table 9 .

In the one study examining cognition, 51 the control group (simple calculations) exhibited significant improvements in cognitive function relative to the art therapy group. Data relating to significant differences are reported in Table 9 .

Self-esteem

In the one study examining self-esteem, 52 art therapy resulted in significant improvements in self-esteem relative to the control group. Data relating to significant differences are reported in Tables 9 and 10 .

- Adverse events

Adverse events were not reported in any of the included RCTs. However, three studies reported outcomes that may be indirectly related to the safety of art therapy. The Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 48 study reported no significant differences between groups in the number of incidents, seclusions, restraints or ‘PRN [pro re nata, as needed] orders’. The Broome et al. 50 study reported a decrease in emergency room visits, clinic visits and hospital admissions over time in both the art therapy and control groups. In addition, the Beebe et al. 58 study reported equal asthma exacerbation numbers in each group but these occurred after the trial has finished.

The lack of adverse event data in the majority of included studies is not necessarily evidence that there were no adverse events in the included trials. It may indicate only that adverse events were not recorded. Potential harms and negative effects of art therapy are further explored in the qualitative review (see Chapter 3 ).

- Quality assessment: strength of the evidence

Table 12 illustrates the types of study designs and the number of studies included into the quantitative and qualitative reviews.

Study designs and their inclusion into the review

Critical appraisal of the potential sources of bias in the included studies

Method of recruitment.

Participants were typically convenience samples from existing clinical patient groups. Few details were provided on the inclusion/exclusion criteria of the patients in the studies, as can be seen from Table 13 .

Method of participant recruitment in the 15 included RCTs

Allocation bias: Method of randomisation

Table 14 shows the descriptions of randomisation from the included RCTs. Randomisation usually refers to the random assignment of participants to two or more groups. Randomisation was not described in seven studies. 48 – 50 , 54 , 55 , 58 , 59 This information could simply be missing from the published journal paper and, if benefit of the doubt were applied, it could be assumed that proper randomisation may have been done but not reported. This would represent an unclear risk of bias. However, it could also be assumed that proper randomisation did not take place and the method of selecting participants into the studies was flawed. This would represent a high risk of bias. Therefore, there is an unclear/high risk that randomisation was not adequately performed in these six studies.

Description of randomisation from the included RCTs

Allocation bias: allocation concealment

In order to ensure that the sequence of treatment allocation was concealed, a robust method of allocation to the study arms should be undertaken and documented. Allocation concealment was not reported in any of the included studies. Lack of allocation concealment can destroy the purpose of randomisation, as it can permit selective assignment to the study arms.

Appropriate randomisation for allocation to study arms includes undertaking ‘simple’ randomisation (e.g. tossing a coin), which avoids introducing excessive stratification to prevent imbalanced groups, and ‘distance’ randomisation so that researchers are unable to influence allocation (e.g. a central randomisation service which notes basic patient details and issues a treatment allocation). Several of the eight randomisation methods described are likely to be open to allocation bias either because they did not use distance randomisation or because the reports do not provide enough details about what measures were taken to ensure that allocation was truly concealed to the investigators. For example, the Hattori et al. 51 study describes stratification by three variables. Stratifying by more than one variable can be problematic, and stratifying by more than two variables is not advisable. 65 In addition, the Kim 52 study does not clearly describe how randomisation was undertaken. The sealed envelope technique employed in the McCaffrey et al. 53 study is intended to ensure that equal numbers receive the intervention and the control but is vulnerable to subterfuge. Few of the included RCTs reported adequate details of methods of randomisation and, consequently, these studies, as reported, had an unclear risk of allocation bias.

Performance bias: blinding

Blinding of participants was not conducted in any of the included RCTs. Blinding of participants to their experimental condition is understandably unfeasible in trials of psychological therapy as opposed to pharmacological interventions. Therefore, while lack of blinding across the included trials means that the trials are at risk of performance bias, the trials cannot be deemed to be of poor quality on this basis.

Performance bias: baseline comparability

Groups were reported to be comparable at baseline in 7 out of the 15 studies ( Table 15 ). 48 , 51 – 54 , 56 , 62 (Baseline comparability was unclear or not reported and therefore was unable to be assessed in five studies. 47 , 49 , 50 , 55 , 58 ) In three studies, 57 , 59 , 61 patients in the art therapy group appeared to have more severe illness at baseline. These differences could reflect a potential allocation bias resulting from flawed randomisation procedures in the studies.

Baseline comparability between intervention and control groups in the included 15 RCTs

Performance bias: groups treated equally

As blinding was not possible, all studies are at risk of performance bias. In the case of the six studies 49 , 55 , 58 , 59 , 61 , 62 that had wait-list/treatment as usual controls rather than an active comparator group, it can be argued that the groups were not treated equally, as the control groups were not given the time and attention that an active control group would receive. Therefore, the risk of performance bias in the art therapy group is higher in these six studies.

Reporting bias: selective outcome reporting

No studies appeared to have collected data on outcomes that were not reported in the results.

Reporting bias: incomplete outcome data

In three studies, 48 , 54 , 57 outcome data were incomplete, indicating a high risk of reporting bias. The reasons for this were: data on 20% completers only (80% of participants withdrew or were excluded); 48 actual data not provided (only p -values reported); 54 and group numbers not provided at any time point. 57 In four studies the risk of reporting bias was unclear because incomplete outcome data were reported. 49 , 50 , 58 , 59

Detection bias

Blinding of clinical outcome assessment was reported to be conducted in only one study. 58 Therefore, 14 out of the 15 included RCTs are at unclear to high risk of detection bias, as assessors may have influenced the recording of clinical outcomes.

Researcher allegiance

In the Kim 52 study there was only one author, and the two researchers are reported to be art therapists. The author is also a senior art therapist. The Gussak 2007 59 study also has only one author, who is a professor of art therapy. Trials that are published by one author are unlikely to have been conducted as collaborative projects adhering to standards of good clinical practice. The risk of researcher allegiance in these studies is, therefore, high.

The McCaffrey et al. 2011 53 study was funded by the owners of the gardens that were the basis of the comparator. The gardens are profit-making, and participants who completed the study were given 1 year’s free membership. The risk of researcher allegiance for the control group in this study, can, therefore, be considered to be high.

As can be seen from Table 16 , all studies were prone to many instances of unclear risk of bias. Some studies were prone to several instances of high risk of bias. In the context of this review, with the exception of blinding participants, all the risk of bias domains are important to be able to establish internal validity of these trials. Currently the only domain that is at low risk of bias is selective outcome reporting. Owing to the risks of bias highlighted by the critical appraisal of these studies, it can be concluded that the included RCTs are generally of low quality.

Summary of risk of bias (high, low or unclear) in the 15 included quantitative studies

Critical appraisal of other potential sources of confounding

Withdrawals and exclusions are reported in Table 17 .

Withdrawals from the study across the included RCTs

As can be seen from Table 17 , there were only four studies in which all participants completed the trial. 52 , 54 , 55 , 58 While several studies reported substantial numbers of dropouts, only one study reported to be sized with reference to effect size. 61 Considering that the sample sizes in the remaining 14 RCTs are small and not sufficiently powered to account for attrition, these dropouts have a significant impact on the reliability of these RCTs. For example, in the Rusted et al . 57 study, attrition was 53.3%, meaning that the final data are reported for 9 versus 12 people in the art therapy and activity control groups, respectively. This small number of completers calls into question the reliability of this study’s results.

Only 5 of the 11 studies in which dropouts occurred reported the breakdown of withdrawal between groups. Two studies 50 , 59 do not report the reasons for withdrawal in the dropouts that occurred. In addition, attrition was not handled appropriately in the included RCTs as imputation for missing data were generally not reported or were reported to be not conducted except in one study. 62 The risk of attrition bias in the 11 studies where dropouts occurred is, therefore, unclear.

Concomitant treatment

Co-therapy or concomitant medication was not reported in eight trials. 49 – 52 , 55 – 58 In a further two studies, 53 , 61 participants were eligible to take part if in receipt of mental health treatment but the actual data for concomitant therapy (overall or between groups) are not reported.

In the Gussak 59 study, 93% ( n = 25/27) of participants in the intervention group were taking medication for a mental illness, compared with 27% ( n = NR) in the control group. In the Thyme et al. 47 study, it was reported that psychopharmacological treatment was an exclusion criterion. It is subsequently stated that ‘in the [art therapy] group, one participant were [sic] prescribed antidepressants during therapy ( n = 1) and one between termination of therapy and the 3-month follow-up ( n = 1), and in the [verbal therapy] group three during therapy ( n = 1) [sic] and two after ( n = 2). Two participants in VT accepted Body Awareness as an additional treatment during psychotherapy.’ 47

In the Thyme et al. 2009 62 study the usage of antidepressants was self-reported, and therefore this information may be incomplete. In the Chapman et al. 49 study, ‘treatment as usual’ hospital care was defined as the normal and usual course of paediatric care including Child Life services, art therapy, and social work and psychiatric consultations. While only the Monti et al. 2012 54 study reports that use of psychotropic medication was an exclusion criterion, there is generally an unclear/high risk of confounding as a result permitted additional treatment across the included studies.

Treatment fidelity

Sufficient measures to ensure treatment fidelity would include monitoring the therapy sessions through audio or video tapes to allow independent checking. No such measures to ensure that the intervention was being delivered consistently were reported in any of the studies. However, one study 58 does provide an appendix of the content of each session. In addition, one study 61 provides the art therapy programme details in the first of the two resulting publications. 60 Most studies provided brief synopses of the intervention programme and content of the sessions. 48 , 50 , 52 , 54 – 56 , 62 However, some studies provided scant details of what took place in the sessions. 47 , 49 , 51 , 53 , 57 , 66 Moreover, Chapman et al. 49 do not even state how many sessions were provided. Therefore, the included RCTs have unclear risk of poor treatment fidelity.

The risk of bias assessment and the potential areas of confounding including attrition, concomitant treatment and treatment fidelity illustrate that the included trials are generally of low quality and, therefore, the results of the 15 RCTs that are included in the quantitative review should be interpreted with caution. Three studies 47 , 51 , 56 can be considered as being of slightly better quality because there are no instances of high risk of bias (other than blinding, which is a common hurdle in trials of psychological therapy) and at low risk of bias on at least four domains.

Discussion of the quantitative review

The aim of the quantitative systematic review was to assess the evidence of clinical effectiveness of art therapy compared with control for treating non-psychotic mental health disorders. The limited available evidence showed that patients receiving art therapy had significant positive improvements in 14 out of 15 RCTs. In 10 of these studies, art therapy resulted in significantly more improved outcomes than the control, while in four studies art therapy resulted in an improvement from baseline but the improvement in the intervention group was not significantly greater than in the control group. In one study, outcomes were better in the control group than in the art therapy group. Relevant mental health outcome domains that were targeted in the included studies were depression, anxiety, mood, trauma, distress, QoL, coping, cognition and self-esteem. Improvements were frequently reported in each of these symptoms except for cognition.

Limitations of the quantitative evidence

Despite every possible effort to identify all relevant trials, the number of studies that qualified for inclusion was small. Despite a large number of records on art therapy yielded from the searches, very few studies were RCTs, demonstrating a slow uptake of the evidence-based medicine model in this field. The study samples are heterogeneous and few samples can be regarded strictly as the target population for this review – people diagnosed with a mental health condition. The limited selection of mental health disorders in the included study samples means that the external validity to the population with non-psychotic mental health disorders is limited. In addition, the sample sizes are small, and as yet there are no large-scale RCTs of art therapy in non-psychotic mental health disorders. The paucity of RCT evidence means that it is not possible to make generalisations about specific disorders or population characteristics.

The risk assessment of bias highlighted that, although all studies were reported to be RCTs, few studies reported how patients were randomised, and in the majority of studies there were several instances of high risk of bias. Areas of potential confounding frequently associated with the studies included attrition, concomitant treatment and treatment fidelity. Consequently, the internal validity of the included studies is threatened. Owing to the low quality of the 15 RCTs, the results included in the quantitative review should be interpreted with caution. As this systematic review did not search for and include direct evidence about other interventions for non-psychotic mental health disorders, it has not been possible to identify indirect evidence for the effect of art therapy in a mixed treatment comparison within the scope of this research. Therefore, the effectiveness of art therapy compared with other commonly used treatments that have been shown to be effective is unknown. In addition, the underlying mechanisms of action in art therapy remain unclear from this evidence. The qualitative systematic review that is presented in the next chapters will explore the factors that may contribute to the therapeutic action in art therapy.

- Conclusions

From the limited number of studies identified, in patients with different clinical profiles, art therapy was reported to have statistically significant positive effects compared with control in a number of studies. The symptoms most relevant to the review question which were effectively targeted in these studies were depression, anxiety, low mood, trauma, distress, poor QoL, inability to cope and low self-esteem. The small evidence base, consisting of low-quality RCTs, indicated that art therapy was associated with an improvement from baseline in all but one study and was a more effective treatment for at least one outcome than the control groups in the majority of studies.

Included under terms of UK Non-commercial Government License .

- Cite this Page Uttley L, Scope A, Stevenson M, et al. Systematic review and economic modelling of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy among people with non-psychotic mental health disorders. Southampton (UK): NIHR Journals Library; 2015 Mar. (Health Technology Assessment, No. 19.18.) Chapter 2, Clinical effectiveness of art therapy: quantitative systematic review.

- PDF version of this title (1.3M)

In this Page

Other titles in this collection.

- Health Technology Assessment

Recent Activity

- Clinical effectiveness of art therapy: quantitative systematic review - Systemat... Clinical effectiveness of art therapy: quantitative systematic review - Systematic review and economic modelling of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy among people with non-psychotic mental health disorders

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- Open access

- Published: 16 May 2022

The effect of active visual art therapy on health outcomes: protocol of a systematic review of randomised controlled trials

- Ronja Joschko ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4450-254X 1 ,

- Stephanie Roll ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1191-3289 1 ,

- Stefan N. Willich 1 &

- Anne Berghöfer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7897-6500 1

Systematic Reviews volume 11 , Article number: 96 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

7574 Accesses

2 Citations

Metrics details

Art therapy is a form of complementary therapy to treat a wide variety of health problems. Existing studies examining the effects of art therapy differ substantially regarding content and setting of the intervention, as well as their included populations, outcomes, and methodology. The aim of this review is to evaluate the overall effectiveness of active visual art therapy, used across different treatment indications and settings, on various patient outcomes.

We will include randomised controlled studies with an active art therapy intervention, defined as any form of creative expression involving a medium (such as paint etc.) to be actively applied or shaped by the patient in an artistic or expressive form, compared to any type of control. Any treatment indication and patient group will be included. A systematic literature search of the Cochrane Library, EMBASE (via Ovid), MEDLINE (via Ovid), CINAHL, ERIC, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, and PSYNDEX (all via EBSCOHost), ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) will be conducted. Psychological, cognitive, somatic and economic outcomes will be used. Based on the number, quality and outcome heterogeneity of the selected studies, a meta-analysis might be conducted, or the data synthesis will be performed narratively only. Heterogeneity will be assessed by calculating the p-value for the chi 2 test and the I 2 statistic. Subgroup analyses and meta-regressions are planned.

This systematic review will provide a concise overview of current knowledge of the effectiveness of art therapy. Results have the potential to (1) inform existing treatment guidelines and clinical practice decisions, (2) provide insights to the therapy’s mechanism of change, and (3) generate hypothesis that can serve as a starting point for future randomised controlled studies.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO ID CRD42021233272

Peer Review reports

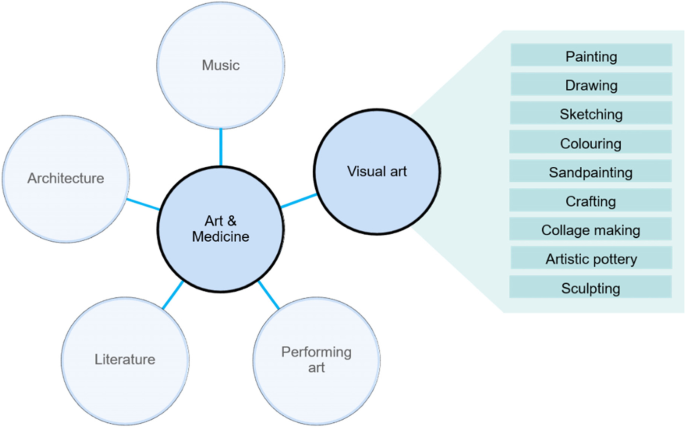

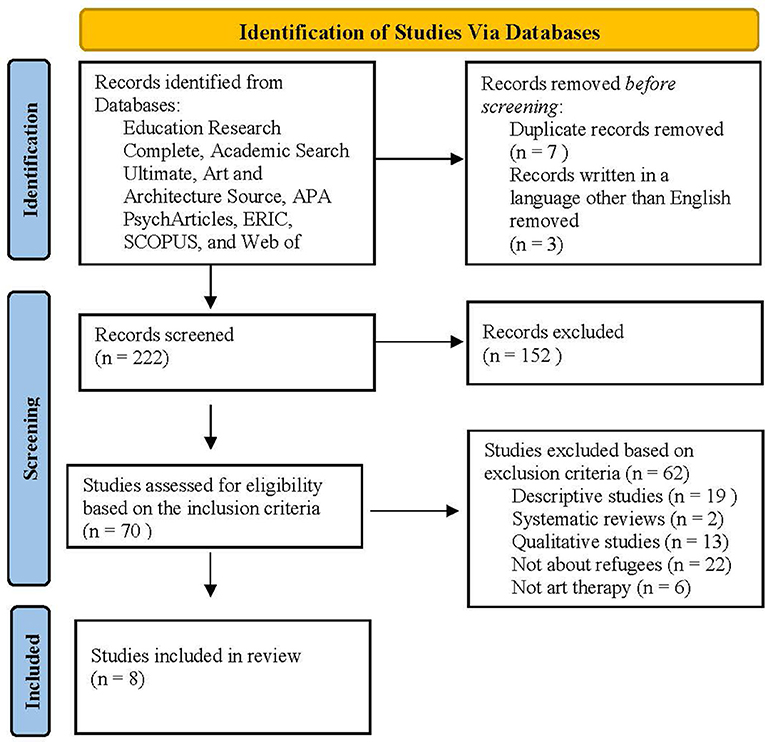

Complementary and integrative treatment methods can play an important role when treating various chronic conditions. Complementary medicine describes treatment methods that are added to the standard therapy regiment, thereby creating an integrative health approach, in the anticipation of better treatment effects and improved health outcomes [ 1 ]. Within a broad field of therapeutic approaches that are used complementarily, art therapy has long occupied a wide space. After an extensive sighting of the literature, we decided to differentiate between five clusters of art that are used in combination with standard therapies: visual arts, performing arts, music, literature, and architecture (Fig. 1 ). Each cluster can either be used actively or receptively.

The five clusters of art used in medicine for therapeutic purposes, with examples of active visual art forms (figure created by the authors)

Active visual art therapy (AVAT) is often used as a complementary therapy method, both in acute medicine and in rehabilitation. The use of AVAT is frequently associated with the treatment of psychiatric, psychosomatic, psychological, or neurological disorders, such as anxiety [ 2 ], depression [ 3 ], eating disorders [ 4 ], trauma [ 5 , 6 ], cognitive impairment, or dementia [ 7 ]. However, the application of AVAT extends beyond that, thereby broadening its potential benefits: it is also used to complement the treatment of cystic fibrosis [ 8 ] or cancer [ 9 , 10 ], to build up resilience and well-being [ 11 , 12 ], or to stop adolescents from smoking [ 13 ].

As a complementary intervention, AVAT aims at reducing symptom burden beyond the effect of the standard treatment alone. Since AVAT is thought to be side effect free [ 14 ] it could be a valuable addition to the standard treatment, offering symptom reduction with no increased risk of adverse events, as well as an potential improvement in quality of life [ 15 , 16 , 17 ].

The existing literature examining the effectiveness of art therapy has shown some positive results across a wide variety of treatment indications, such as the treatment of depression [ 3 , 18 ], anxiety [ 19 , 20 ], psychosis [ 21 ], the enhancement of mental wellbeing [ 22 ], and the complementary treatment of cancer [ 15 , 23 ]. However, the existing evidence is characterised by conflicting results. While some studies report favourable results and treatment successes through AVAT [ 17 , 24 , 25 , 26 ], many studies report mixed results [ 3 , 15 , 16 , 27 , 28 ]. There is a substantial number of systematic reviews which examine the effectiveness of art therapy regarding individual outcomes, such as trauma [ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 ], anxiety [ 19 ] mental health in people who have cancer [ 23 , 34 , 35 ] dementia [ 7 ], and potential harms and benefits of the intervention [ 36 ]. The limited number of published studies, however, can make the creation of a systematic review difficult, especially when narrowing down additional factors, such as the desired study design [ 7 ].

Therefore, it might be helpful to combine all existing evidence on the therapeutic effects of AVAT in one review, to generate evidence regarding its overall effectiveness. To our knowledge, there is no systematic review that accumulates the data of all published RCTs on the topic of AVAT, while abiding to strict methodological standards, such as the Cochrane handbook [ 37 ] and the PRISMA statement [ 38 ]. We thus aim to establish and strengthen the existing evidence basis for AVAT, reflecting the clinical reality by including a wide variety of settings, populations, and treatment indications. Furthermore, we will try to identify characteristics of the setting and the intervention that may increase AVAT’s effectiveness, as well as differences in treatment success for different conditions or reasons for treatment.

Methods/Design

Registration and reporting.

We have submitted the protocol to PROSPERO (the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) on February 9, 2021 (PROSPERO ID: CRD42021233272). In the writing of this protocol we have adhered to the adapted PRISMA-P (Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols, see Additional file 1 ) [ 39 ]. Important protocol amendments will be submitted to PROSPERO.

Eligibility criteria

Type of study.

We will include randomised controlled trials to minimise the sources of bias possibly arising from observational study designs.

Types of participants

As AVAT is used across many patient populations and settings, we will include patients across all treatment indications. Thus, we will include populations receiving curative, palliative, rehabilitative, or preventive care for a variety of reasons. Patients of all ages (including seniors, children and adolescents), all cultural backgrounds, and all living situations (inpatients, outpatients, prison, nursing homes etc.) will be included without further restrictions. The resulting diversity reflects the current treatment reality. Heterogeneity of included studies will be accounted for by subgroup analyses at the stage of data synthesis. Differences in treatment success depending on population characteristics are furthermore of special interest in this review.

Types of interventions

As the therapeutic mechanisms of AVAT are not yet unanimously agreed upon, we want to reduce the heterogeneity of treatment methods included by focusing on only one cluster of art activities (active visual art).

We define AVAT as any form of creative expression involving a medium such as paint, wax, charcoal, graphite, or any other form of colour pigments, clay, sand, or other materials that are applied or shaped by the individual in an artistic or expressive form.

The interventions must include a therapeutic element, such as the targeted guidance from an art therapist or a reflective element. Both, group and individual treatment in any setting are included.

Purely occupational activities not intended to have a therapeutic effect will not be considered.

All forms of music, dance, and performing art therapies, as well as poetry therapy and (expressive) writing interventions which focus on the content rather than appearance (like journal therapy) will not be included. Studies with mixed interventions will be included only if the effects of the AVAT can be separated from the effects of the other treatments. Furthermore, all passive forms of visual art therapy will be excluded, such as receptive viewings of paintings or pictures.

Comparison interventions

Depending on the treatment indication and setting, the control group design will likely vary. We will include studies with any type of control group, because art therapy research, just like psychotherapy research, must face the problem that there are usually no standard controls like, e.g. a placebo [ 40 ]. Therefore, we will include all control groups using treatment as usual (including usual care, standard of care etc.), no treatment (with or without waitlist control design), or any active control other than AVAT (such as attention placebo controls) as potential comparators.

Stakeholder involvement

Stakeholders will be involved to increase the relevance of the study design. Patients, art therapists, and physicians prescribing art therapy, all from a centre that uses AVAT regularly, will be interviewed using a semi structured questionnaire that captures the expert’s perspective on meaningful outcomes. Particularly, we are interested in the stakeholders’ opinions about which outcomes might be most affected by AVAT, which individual differences might be expected, and which other factors could affect the effectiveness of AVAT.

A second session might be held at the stage of result interpretation as the stakeholders’ perspective could be a valuable tool to make sense of the data.

As there is no universal standard regarding the outcomes of AVAT, we have based our choice of outcome measures on selected, high quality work on the subject [ 7 ], and on theoretical considerations.

Outcome measures will include general and disease specific quality of life, anxiety, depression, treatment satisfaction, adverse effects, health economic factors, and other disorder specific outcomes. The latter are of special relevance for the patients and have the potential to reflect the effectiveness of the therapy. The disorder specific outcomes will be further clustered into groups, such as treatment success, mental state, affect and psychological wellbeing, cognitive function, pain (medication), somatic effects, therapy compliance, and motivation/agency/autonomy regarding the underlying disease or its consequences. Depending on the included studies, we might re-evaluate these categories and modify the clusters if necessary.

Outcomes will be grouped into short-term and long-term outcomes, based on the available data. The same approach will be taken for dividing the treatment groups according to intensity, with the aim of observing the dose-response relationship.

Grouping for primary analysis comparisons

AVAT interventions and their comparison groups can be highly divers; therefore, we might group them into roughly similar intervention and comparison groups for the primary analysis, as indicated above. This will be done after the data extraction, but before data analysis, in order to minimise bias.

Search strategy

Based on the recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook we will systematically search the Cochrane Library, EMBASE (via Ovid), and MEDLINE (via Ovid) [ 41 ]. Furthermore, we will search CINAHL, ERIC, APA PsycArticles, APA PsycInfo, and PSYNDEX (all via EBSCOHost), as well as the ClinicalTrials.gov and the WHO’s International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP), which includes various smaller and national registries, such as the EU Clinical Trials Register and the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS).

The search strategy is comprised of three search components; one concerning the art component, one the therapy component and the last consists of a recommended RCT filter for EMBASE, optimised for sensitivity and specificity [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. See Additional file 2 for the complete search strategy, exemplified for the Cochrane Library search interface. In addition, relevant hand selected articles from individual databank searches, or studies identified through the screening of reference lists will be included in the review. A handsearch of The Journal of Creative Arts Therapies will be conducted.

Results of all languages will be considered, and efforts undertaken to translate articles wherever necessary. There will be no limitation regarding the date of publication of the studies.

Data collection and data management

Study selection process.

Two reviewers will independently scan and select the studies, first by title screening, second by abstract screening, and in a third step by full text reading. The two sets of identified studies will then be compared between the two researchers. In case of disagreement that cannot be resolved through discussion, a third researcher will be consulted to decide whether the study in question is eligible for inclusion. The Covidence software will be used for the study selection process [ 45 ].

Data extraction

All relevant data concerning the outcomes, the participants, their condition, the intervention, the control group, the method of imputation of missing data, and the study design will be extracted by two researchers independently and then cross-checked, using a customised and piloted data extraction form. The chosen method of imputation for missing data (due to participant dropout or similar) will be extracted per outcome. Both, intention to treat (ITT) and per protocol (PP) data will be collected and analysed.

If crucial information will be missing from a study and its protocol, authors will be contacted for further details.

Risk of bias assessment for included studies

In line with the revised Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomised trials (RoB 2) [ 46 ], we will examine the internal bias in the included studies regarding their bias arising from the randomisation process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcome, and in selection of the reported result [ 47 ].

The risk will be assessed by two people independently from each other, only in cases of persisting disagreement a third person will be consulted.

If the final sample size allows, we will conduct an additional analysis in which the included studies are analysed separately by bias risk category.

Measures of treatment effect

If possible, we will conduct our main analyses using intention-to-treat data (ITT), but we will collect ITT and per-protocol (PP) data [ 48 ]. If for some studies ITT data is not reported, we will use the available PP data instead and perform a sensitivity analysis to see if that affects the results. Dichotomous data will be analysed using risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals, as they have been shown to be more intuitive to interpret than odds ratio for most people [ 49 ]. We will analyse continuous data using mean differences or standardised mean differences.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster trials.

If original studies did not account for a cluster design, a unit of analysis error may be present. In this case, we will use appropriate techniques to account for the cluster design. Studies in which the authors have adjusted the analysis for cluster-randomisation will be used directly.

Cross-over trials

An inherent risk to cross-over trials is the carry-over effect.

This design is also problematic when measuring unstable conditions such as psychotic episodes, as the timing could account more for the treatment success than the treatment itself (period effect).

As art therapy is used frequently in the treatment of unstable conditions, such as mental health problems or neurodegenerative disorders (i.e. Alzheimer’s), we will include full cross-over trials only if chronic and stable concepts are measured (such as permanent physical disabilities or epilepsy) [ 50 ].

When including cross-over studies measuring stable conditions, we will include both periods of the study. To incorporate the results into a meta-analysis we will combine means, SD or SE from both study periods and analyse them like a parallel group trial [ 51 ]. For bias assessment we will use the risk of bias tool for crossover trials [ 47 ].

For cross-over studies that measure unstable or degenerative conditions of interest, we will only include the first phase of the study as parallel group comparison to minimise the risk of carry-over or period effects. We will evaluate the risk of bias for those cross-over trials using the same standard risk of bias tool as for the parallel group randomised trials [ 52 ]. We will critically evaluate studies that analyse first period data separately, as this might be a form of selective reporting and the inclusion of this data might result in bias due to baseline differences. We might exclude studies that use this kind of two-stage analysis if we suspect selective reporting or high risk for baseline differences [ 47 ].

Missing data

Studies with a total dropout rate of over 50% will be excluded. To account for attrition bias, studies will be downrated in the risk of bias assessment (RoB 2 tool) if the dropout rate is more than half for either the control or the intervention group. An overall dropout rate of 25–50% we will also be downrated.

Assessment of clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity

We will discuss the included studies before calculating statistical comparisons and group them into subgroups to assess their clinical and methodological heterogeneity. Statistical heterogeneity will be assessed by calculating the p value for the chi 2 test. As few included studies may lead to insensitivity of the p value, we may adjust the cut-off of the p value if we only included a small amount of studies [ 49 ]. In addition, we will calculate the I 2 statistic and its confidence interval, based on the chi 2 statistic to assess statistical heterogeneity. We will explore possible reasons for observed heterogeneity, e.g. by conducting the planned subgroup analyses. Based on the amount and quality of included studies and their outcome heterogeneity, we will decide if a meta-analysis can be conducted. In case of high statistical heterogeneity, we first check for any potential errors during the data input stage of the review. In a second step, we evaluate if choosing a different effect measure, or if the justified removal of outliers will reduce heterogeneity. If the outcome heterogeneity of the selected studies is still too high, we will not conduct a meta-analysis. If clinical heterogeneity is high but can be reduced by adjusting our planned comparisons, we will do so.

Reporting bias

Funnel plot.

Funnel plots can be a useful tool in detecting a possible publication bias. However, we are aware, that asymmetrical funnel plots can potentially have other causes than an underlying publication bias. As a certain number of studies is needed in order to create a meaningful funnel plot, we will only create those plots, if more than about 10 studies are included in the review.

Data analysis and synthesis

Based on the amount and quality of included studies and their heterogeneity, we will decide if a meta-analysis is feasible.

If a meta-analysis can be conducted, we will be using the inverse variance method with random effects (to increase compatibility with the different identified effect measures and to account for the diversity of the included interventions). We would expect each study to measure a slightly different effect based on differing circumstances and differing intervention characteristics. Therefore, a random effects model is the most suitable option.

A disadvantage of the random effects model is that it does not give studies with large sample sizes enough weight when compared to studies with small sample sizes and therefore could lead to a small study effect. However, we expect to find studies with comparable study sizes with an N of 10–50, as very large trials are uncommon for art therapy research. If we include studies with a very large sample size, we might calculate a fixed effects model additionally, as sensitivity analysis, to assess if this would affect the results.

If the calculation of a meta-analysis is not advisable due to difficulties (such as a low number of included studies, low quality of included studies, high heterogeneity, incompletely reported outcome or effect estimates, differing effect measures that cannot be converted), we will choose the most appropriate method of narrative synthesis for our data, such as the ones described in the Cochrane Handbook (i.e. summarising effect estimates, combining p values or vote counting based on direction of effect) [ 53 ].

Subgroup analysis

If the number of included studies is large enough (around 10 or more [ 54 ]) and subgroups have an adequate size, we plan to compare subgroups based on the therapy setting (inpatient, outpatient, kind of institution), the intervention characteristics (the kind of AVAT, intensity of treatment, staff training, group size), the population (treatment indication, age, gender, country), or other study characteristics (e.g. bias category, publication date). If possible, we will also examine these factors by calculating meta-regressions.

Sensitivity analysis

Where possible, sensitivity analyses will be conducted using different methods to establish robustness of the overall results. Specifically, we will assess the robustness of the results regarding cluster randomisation and high risk of bias (RoB 2 tool).

AVAT encompasses a wide array of highly diverse treatment options for a multitude of treatment indications. Even though AVAT is a popular treatment method, the empirical base for its effectiveness is rather fragmented; many (often smaller) studies examined the effect of very specific kinds of AVATs, with a narrow focus on certain conditions [ 2 , 7 , 55 , 56 ]. Our review will give a current overview over the entire field, with the hope of estimating the magnitude of its effectiveness. Several clinical guidelines recommend art therapy based solely on clinical consensus [ 57 ]. By accumulating all empirical evidence, this systematic review could inform the creation of future guidelines and thereby facilitate clinical decision-making.

Understanding the benefits, limits, and mechanisms of change of AVAT is crucial to optimally apply and tailor it to different contexts and settings. Consequently, by better understanding this intervention, we could potentially increase its effectiveness and optimise its application, which would lead to improved patient outcomes. This would not only benefit each individual who is treated with AVAT, but also the health care provider, who could apply the intervention in its most efficient way, thereby using their resources optimally.