Understanding an Abstract Noun (Definition, Examples, Word List)

What is an abstract noun? How is it different from a common noun ? What are words that represent an abstract noun? These are all great questions that you probably have . Abstract nouns can get confusing when comparing them to regular common nouns or proper nouns. This comprehensive guide will break down the abstract noun, its use , and the functions that grammatically govern it.

What is an abstract noun?

An abstract noun is a type of noun that represents intangible things. Things you can’t perceive with the five primary senses in the human body (taste, touch, smell, etc.).

Abstract noun definition

As the name suggests, an abstract noun is a noun type. It refers to an intangible idea (one that you cannot fathom using your five senses). Such intangible concepts could include emotions, qualities, ideas, etc.

All nouns that do not have a tangible or physical object to refer to fall under the bracket of abstract nouns . Abstract nouns are widely used in English proverbs.

Some common examples include health, wealth, parenthood, anger, courage, and more.

Abstract noun compared to other nouns

Nouns are an essential part of speech. They are instrumental in naming places, people, objects, animals, and intangible ideas.

You may have noticed that whenever you write a sentence , you are using at least one noun in it.

Nouns can get used differently in different sentence formations. Their functions can vary. Here are the main types of nouns you could use in a complete sentence:

Proper Nouns

Proper nouns are naming agents for places, people, or things. They usually start with a capital letter.

For example:

- My name is Lisa. (Lisa is the proper noun )

- John lives in Finland. (Finland is the proper noun)

- Jazz is a famous book. (Jazz is the proper noun)

Common Nouns

Nouns that refer to generic things are referred to as common nouns .

- I bought a new book yesterday. (Book is the common noun)

- There is a pigeon on the windowsill. (Pigeon is the common noun)

- Rob bought a blue car. (Car is the common noun)

Countable Nouns

Nouns that can be measured or counted are called countable nouns .

- I take two spoons of sugar in my tea. (“Two” is the countable noun )

- She bought a dozen bananas at the market. (“A dozen” is the countable noun)

Uncountable Nouns

Nouns that cannot be measured or counted are called uncountable nouns.

- I have plenty of homework. (Plenty is the uncountable noun)

- Is that enough milk in your coffee? (Enough is the uncountable noun)

Collective Nouns

Collective nouns depict a group of objects, people, animals, and more.

- A flock of sheep

- A pile of books

- A school of fish

- A bevy of women

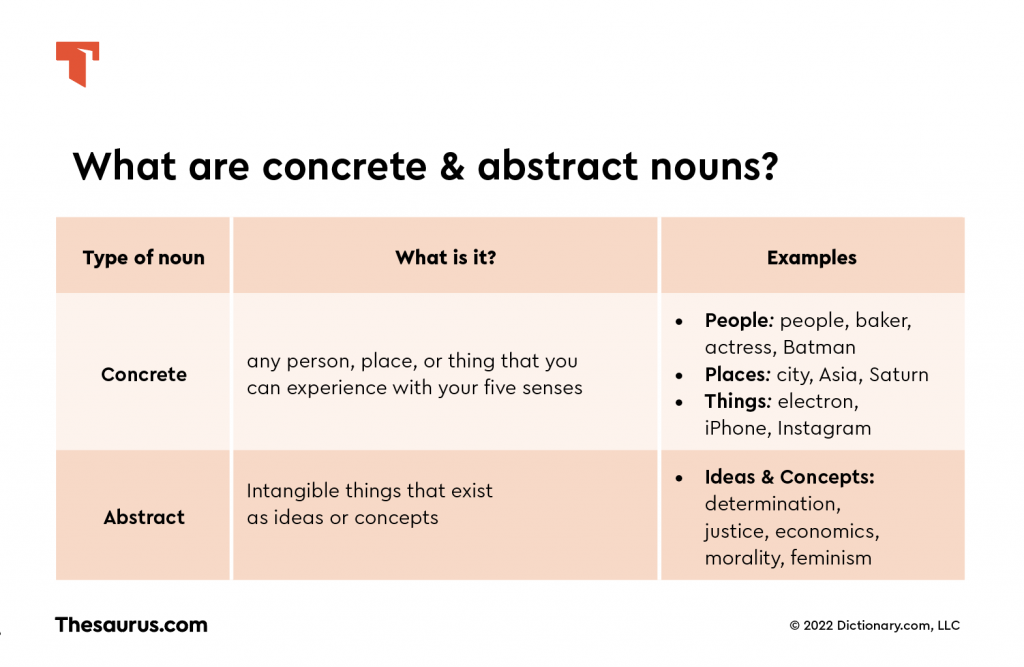

Concrete Nouns

Also referred to as material nouns, concrete nouns refer to things that have a physical presence and can be perceived using the five senses.

Abstract Nouns

Any noun that is intangible or which cannot be perceived using the five senses is an abstract noun .

- Bravery is a virtue. (Bravery is the abstract noun)

- My childhood was merry and fun . (Childhood is the abstract noun)

Abstract nouns in comparison to concrete nouns

Concrete noun, as the name suggests, includes all those objects which have a physical presence and are tangible. They can be perceived with the help of our five senses. These include nouns such as book, pen, cup, table silk, door, car, and so on.

- I travel to school by bus . (School and bus are both concrete nouns )

- Sally opened the door. (Door is the concrete noun)

Abstract nouns include everything that is intangible and cannot be perceived by the five senses. These include emotions, feelings, ideas, and more.

- Honesty is the best policy. (Honesty is the abstract noun)

- Freedom is my birthright. (Freedom is the abstract noun)

Abstract noun word list

Here are some examples of abstract nouns based on their kind.

- Feelings – sympathy, fear, anxiety, stress, pleasure

- State – Chaos, peace, misery, freedom

- Emotions – anger, joy, sorrow, hate

- Qualities – determination, courage, honesty, generosity, patience

- Concepts – democracy, charity, deceit, opportunity, comfort

- Moments – career, death, marriage, childhood, birth

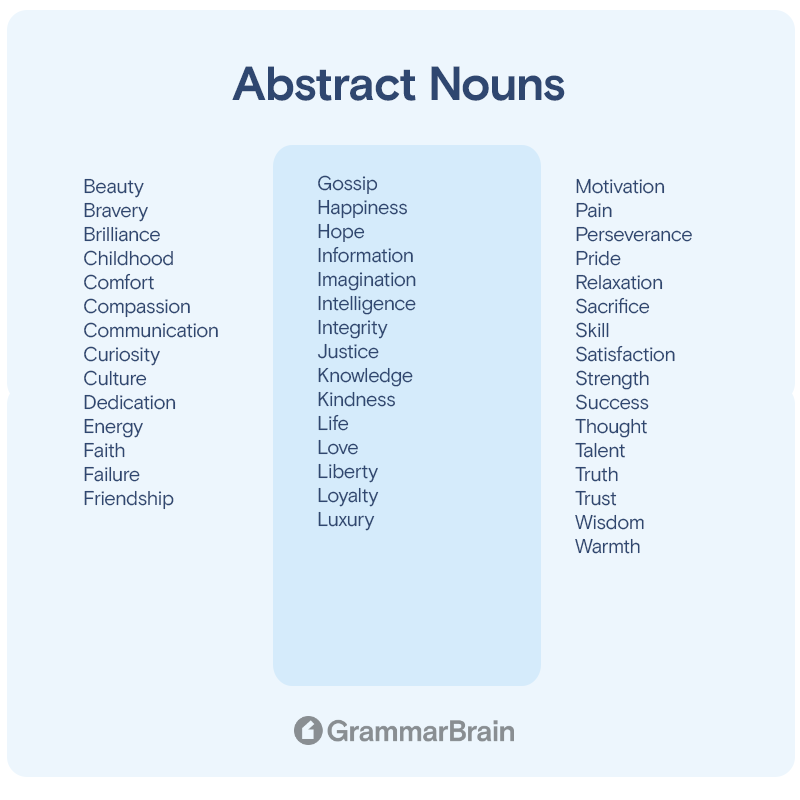

More examples of commonly used abstract nouns

- Bravery

- Brilliance

- Childhood

- Comfort

- Compassion

- Communication

- Curiosity

- Culture

- Dedication

- Energy

- Faith

- Friendship

- Gossip

- Information

- Imagination

- Intelligence

- Integrity

- Justice

- Knowledge

- Kindness

- Liberty

- Loyalty

- Luxury

- Motivation

- Perseverance

- Relaxation

- Skill

- Satisfaction

- Strength

- Success

- Thought

- Talent

- Truth

- Trust

- Wisdom

- Warmth

Sentence examples with abstract nouns

The following are three sentence examples with abstract nouns –

- This cafe has a pleasant ambiance. (Ambiance is the abstract noun)

- Pride is a deadly sin. (Pride is the abstract noun)

- My friendship with Peter is of seven years . (Friendship is the abstract noun)

Conversion of Verbs and Adjectives into Abstract Nouns

Convert verbs and adjectives into abstract nouns by adding a suffix . The reverse is also a possibility.

- Perceive – Perception

- Inform – Information

- Determine – Determination

- Dark – Darkness

- Silent – Silence

Why are abstract nouns important?

Abstract nouns are tricky. Use concrete nouns to make them understandable in sentences. Abstract nouns are not of much use from a business point of view.

However, they are an integral part of any English grammar course. Conversions between abstract nouns and verbs or adjectives are essential while learning complete sentence construction.

Yes, warmth is an abstract noun.

The abstract form of ability (abstract noun) is able.

Five examples of abstract nouns include honesty, glory, patience, determination, and truth.

Inside this article

Fact checked: Content is rigorously reviewed by a team of qualified and experienced fact checkers. Fact checkers review articles for factual accuracy, relevance, and timeliness. Learn more.

About the author

Dalia Y.: Dalia is an English Major and linguistics expert with an additional degree in Psychology. Dalia has featured articles on Forbes, Inc, Fast Company, Grammarly, and many more. She covers English, ESL, and all things grammar on GrammarBrain.

Core lessons

- Abstract Noun

- Accusative Case

- Active Sentence

- Alliteration

- Adjective Clause

- Adjective Phrase

- Adverbial Clause

- Appositive Phrase

- Body Paragraph

- Compound Adjective

- Complex Sentence

- Compound Words

- Compound Predicate

- Common Noun

- Comparative Adjective

- Comparative and Superlative

- Compound Noun

- Compound Subject

- Compound Sentence

- Copular Verb

- Collective Noun

- Colloquialism

- Conciseness

- Conditional

- Concrete Noun

- Conjunction

- Conjugation

- Conditional Sentence

- Comma Splice

- Correlative Conjunction

- Coordinating Conjunction

- Coordinate Adjective

- Cumulative Adjective

- Dative Case

- Declarative Statement

- Direct Object Pronoun

- Direct Object

- Dangling Modifier

- Demonstrative Pronoun

- Demonstrative Adjective

- Direct Characterization

- Definite Article

- Doublespeak

- Equivocation Fallacy

- Future Perfect Progressive

- Future Simple

- Future Perfect Continuous

- Future Perfect

- First Conditional

- Gerund Phrase

- Genitive Case

- Helping Verb

- Irregular Adjective

- Irregular Verb

- Imperative Sentence

- Indefinite Article

- Intransitive Verb

- Introductory Phrase

- Indefinite Pronoun

- Indirect Characterization

- Interrogative Sentence

- Intensive Pronoun

- Inanimate Object

- Indefinite Tense

- Infinitive Phrase

- Interjection

- Intensifier

- Indicative Mood

- Juxtaposition

- Linking Verb

- Misplaced Modifier

- Nominative Case

- Noun Adjective

- Object Pronoun

- Object Complement

- Order of Adjectives

- Parallelism

- Prepositional Phrase

- Past Simple Tense

- Past Continuous Tense

- Past Perfect Tense

- Past Progressive Tense

- Present Simple Tense

- Present Perfect Tense

- Personal Pronoun

- Personification

- Persuasive Writing

- Parallel Structure

- Phrasal Verb

- Predicate Adjective

- Predicate Nominative

- Phonetic Language

- Plural Noun

- Punctuation

- Punctuation Marks

- Preposition

- Preposition of Place

- Parts of Speech

- Possessive Adjective

- Possessive Determiner

- Possessive Case

- Possessive Noun

- Proper Adjective

- Proper Noun

- Present Participle

- Quotation Marks

- Relative Pronoun

- Reflexive Pronoun

- Reciprocal Pronoun

- Subordinating Conjunction

- Simple Future Tense

- Stative Verb

- Subjunctive

- Subject Complement

- Subject of a Sentence

- Sentence Variety

- Second Conditional

- Superlative Adjective

- Slash Symbol

- Topic Sentence

- Types of Nouns

- Types of Sentences

- Uncountable Noun

- Vowels and Consonants

Popular lessons

Stay awhile. Your weekly dose of grammar and English fun.

The world's best online resource for learning English. Understand words, phrases, slang terms, and all other variations of the English language.

- Abbreviations

- Editorial Policy

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

9 The meaning of “abstract nouns”: Locke, Bentham, and contemporary semantics

- Published: November 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The meaning of “abstract nouns” raises fundamental philosophical and linguistic questions. Nobody was more aware of this than John Locke, whose treatment of the subject must be the central point of reference for modern semantics. Subsequent to Locke, Jeremy Bentham made another remarkable contribution with his theory of “fictitious entities”. In this chapter we set out an account of abstract nouns which builds on and seeks to re-connect with these largely forgotten antecedents. The chapter proposes several semantic templates for abstract noun meanings, and illustrates them with explications for English words such as illness, trauma, violence, suicide, beauty , and temperature . The chapter also deals with the important role of abstract nouns in constituting topics of discourse and with the profound untranslatability of many abstract nouns.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- English Grammar

- Parts of Speech

- Abstract Nouns

Abstract Nouns - Definition, Examples and Usage

Abstract nouns are naming words that you cannot see, smell, touch or perceive by any of your five senses. Learn more about abstract nouns, definitions, examples and usage of abstract nouns in this article.

Table of Contents

Definition of an abstract noun, converting verbs and adjectives into abstract nouns, test your knowledge on abstract nouns, frequently asked questions on abstract nouns, what is an abstract noun.

An abstract noun is used to refer to concepts, ideas, experiences, traits, feelings or entities that cannot be seen, heard, tasted, smelt or touched. Abstract nouns are not concrete or tangible. There are a lot of abstract nouns (virtues) used in proverbs.

An abstract noun is defined as ‘a noun , for example, beauty or freedom , that refers to an idea or a general quality, not to a physical object’, according to the Oxford Learners Dictionary. According to Collins Dictionary, ‘an abstract noun refers to a quality or idea rather than to a physical object.’

Examples of Abstract Nouns

Check out the following examples of abstract nouns.

A verb or an adjective can be converted into an abstract noun by the addition of a suffix and vice versa. Have a look at the examples given below.

Converting Verbs to Abstract Nouns

- Move – movement

- Reflect – reflection

- Perceive – perception

- Conscious – Consciousness

- Appear – Appearance

- Resist – Resistance

- Appoint – appointment

- Enjoy – enjoyment

- Assign – assignment

- Inform – information

- Decide – decision

- Describe – description

- Determine – determination

- Block – blockade

Converting Adjectives to Abstract Nouns

- Brave – bravery

- Truth – truthful

- Honest – honesty

- Weak – weakness

- Happy – happiness

- Sad – sadness

- Mad – madness

- Responsible – responsibility

- Possible – possibility

- Probable – probability

- Able – ability

- Independent – independence

- Free – freedom

- Silent – silence

Some words can function both as a noun and a verb without any change in spelling. Here are some examples for you.

- Love as a verb – I love the way she works with it.

Love as a noun – Love is one of the qualities everyone should possess

- Divorce as a verb – Harry cannot divorce his wife.

Divorce as a noun – Are you getting a divorce?

- Aim as a verb – You have to aim for the highest grades.

Aim as a noun – What is your aim?

- Battle as a verb – Teena had to battle hard to stay in shape.

Battle as a noun – Do you know who won the battle?

- Play as a verb – The children are playing outdoor games.

Play as a noun – The Shakespearean play was performed by young artists.

Let us now check how much you have learned about abstract nouns. Identify the abstract nouns in the following sentences.

- Honesty is the best policy.

- There is no possibility for you to reach home by six in the evening.

- This place has a really pleasant ambience.

- Pride goes before a fall.

- Brevity is the soul of wit.

- That man is testing my patience.

- Have you read about the theory of evolution?

- Truthfulness is always appreciated.

- Friendship is priceless.

- What do you think about his idea?

Let us find out if you have understood correctly. Check your answers here.

- Honesty is the best policy .

- This place has a really pleasant ambience .

- Brevity is the soul of wit .

- That man is testing my patience .

- Have you read about the theory of evolution ?

- What do you think about his idea ?

What is an abstract noun?

An abstract noun is used to refer to concepts, ideas, experiences, traits, feelings or entities that cannot be seen, heard, tasted, smelt or touched. Abstract nouns are not concrete or tangible.

Give some examples of abstract nouns.

Love, concept, experience, courage, judgement, probability, freedom and soul are some examples of abstract nouns.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

- Share Share

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

paper-free learning

- conjunctions

- determiners

- interjections

- prepositions

- affect vs effect

- its vs it's

- your vs you're

- which vs that

- who vs whom

- who's vs whose

- averse vs adverse

- 250+ more...

- apostrophes

- quotation marks

- lots more...

- common writing errors

- FAQs by writers

- awkward plurals

- ESL vocabulary lists

- all our grammar videos

- idioms and proverbs

- Latin terms

- collective nouns for animals

- tattoo fails

- vocabulary categories

- most common verbs

- top 10 irregular verbs

- top 10 regular verbs

- top 10 spelling rules

- improve spelling

- common misspellings

- role-play scenarios

- favo(u)rite word lists

- multiple-choice test

- Tetris game

- grammar-themed memory game

- 100s more...

Abstract Noun

What is an abstract noun.

- consideration, parenthood, belief, anger

Table of Contents

More Examples of Abstract Nouns

Find the abstract noun test, abstract nouns vs concrete nouns, list of abstract nouns, why abstract nouns are important, video lesson.

Abstract or Concrete? It Could Be Ambiguous.

- anger, anxiety, beauty, beliefs, bravery, brilliance, chaos, charity, childhood, comfort, communication, compassion, courage, culture, curiosity, deceit, dedication, democracy, determination, energy, failure, faith, fear, freedom, friendship, generosity, gossip, happiness, hate, honesty, hope, imagination, information, integrity, intelligence, joy, justice, kindness, knowledge, liberty, life, love, loyalty, luxury, misery, motivation, opportunity, pain, patience, peace, perseverance, pleasure, pride, relaxation, sacrifice, satisfaction, skill, strength, success, sympathy, talent, thought, trust, truth, warmth, wisdom

- ...and my bicycle never leaned against the garage as it does today, all the dark blue speed drained out of it. (from "On Turning Ten" by American Poet Laureate Billy Collins

- If writing a poem, consider expressing abstract ideas using concrete nouns.

Are you a visual learner? Do you prefer video to text? Here is a list of all our grammar videos .

This page was written by Craig Shrives .

Learning Resources

more actions:

This test is printable and sendable

Help Us Improve Grammar Monster

- Do you disagree with something on this page?

- Did you spot a typo?

Find Us Quicker!

- When using a search engine (e.g., Google, Bing), you will find Grammar Monster quicker if you add #gm to your search term.

You might also like...

Share This Page

If you like Grammar Monster (or this page in particular), please link to it or share it with others. If you do, please tell us . It helps us a lot!

Create a QR Code

Use our handy widget to create a QR code for this page...or any page.

< previous lesson

next lesson >

An Artificial Intelligent English Learning Platform

Abstract Nouns

What are abstract nouns.

Abstract nouns signify things that are impossible for us to perceive with the 5 senses. These are nouns that are described as intangible or immaterial, which means we can’t hear, see, smell, taste, or touch them. They represent ideas and qualities that lack physical forms.

Let’s look at the following examples:

- Tae Hyung has shown great determination during the tryouts.

- They’ve known each other for 4 decades. Their friendship is truly remarkable.

- Satu’s enthusiasm for a software overhaul is quite infectious.

- What kind of impression did you want to give to your colleagues?

- I know it was late so I deeply appreciate your consideration .

Abstract nouns can be classified in various ways, but to avoid repetition, abstract nouns may fall into the following groups:

- Human Qualities – dedication, sanity, beauty, honesty, intelligence, bravery, strength, jealousy, brilliance, calmness, sympathy, compassion, wisdom, patience, confidence, stupidity, honor, sophistication, wit, goodness

- Emotions and Feelings – love, hatred, envy, despair, sorrow, hope, anger, delight, excitement, grief, surprise, worry, regret, fascination, tiredness, pleasure, relief, misery, satisfaction, amazement

- Concepts and Ideas – adventure, loss, mercy, communication, knowledge, imagination, dictatorship, faith, opportunity, forgiveness, idea, fragility, liberty, motivation, justice, luxury, necessity, peace, reality, parenthood

Abstract nouns are usually studied in contrast to concrete nouns. Concrete nouns represent nouns that can be perceived by the 5 senses. Cars, butterflies, pizza, the Leaning Tower of Pisa, wands, and so on.

Abstract Nouns Rules

Study the table below for some rules for using concrete nouns:

3 Types of Abstract Nouns Examples

The entire list of abstract nouns is extensive. They refer to qualities, feelings, states of being, and characteristics. The following are examples of abstract nouns in sentences, grouped into 3 main ideas:

1. Human Qualities

- Liam’s scientific curiosity has always been there since he was a kid.

- My friends have done pretty well in life but they never treated me with any ego .

- When will Katrina develop the courage to stand up for herself?

- Samsoon takes his sense of determination after his dad.

- We need candidates who show enthusiasm for teamwork and mutual support.

2. Emotions and Feelings

- Young-hwan’s disbelief at the magician’s routine was apparent in his expression.

- Rainy weather always fills me with a strange kind of sadness .

- It’s not unusual to feel a level of uncertainty after you graduate.

- Alexis and his parents must be beaming with pride when he received a scholarship.

- Luka feels defeated so you’d do well to hide your disappointment about his score.

3. Concepts and Ideas

- Kugaha’s latest installation is marvelous. How does a person achieve such artistry ?

- Tony has seen his share of evil after ten years of working in the force.

- Unemployment is on the rise but I wonder if it’s because people are choosy.

- The truth is, Uriel wanted to study music but he opted for an industry that pays well.

- Many English Club members saw a vast improvement in their grades at school.

Abstract Nouns Exercises with Answers

Exercise on abstract nouns.

Identify whether the underlined noun in each sentence is abstract or concrete:

1. His family has run a business making custom signs for over 9 years.

2. We thank the foundation for such generosity in our outreach programs.

3. One of the issues plaguing the city is squalor in two of its districts.

4. Several hospitals in the region had built dormitories for front liners.

5. They say the opposite, but I think favoritism exists in families.

6. Are these the native dances that we should be doing research on?

7. There are some horror stories going around about the old hotel.

8. Ultimately, Kendra’s logic skills led her team to victory on the challenge.

9. You would think that parenthood is easy, but it’s extremely difficult.

10. I think I sprained some fingers after cutting so much wood.

11. Were there a lot of children at the park today?

12. Willem used to make colorful paper airplanes to sell to his classmates.

13. The law should champion the defenseless, but it doesn’t seem like it.

14. Won’t you show me some mercy and not give me a ticket? Please?

15. Shaylene wanted to use a specific design of bricks for the pathway.

16. His fascination for anatomy has been misunderstood as a dark side.

17. Luigi bought too many bottles of water so they started giving them out.

18. How much information can you gather after a weekend of interviews?

19. There is a great need for more sustainable practices in the fishing industry.

20. Will we have time to visit a few temples at least? I want to take photos.

1. signs: concrete

2. generosity: abstract

3. squalor: abstract

4. hospitals: concrete

5. favoritism: abstract

6. dances: concrete

7. stories: concrete

8. redemption: abstract

9. victory: abstract

10. fingers: concrete

11. children: concrete

12. airplanes: concrete

13. law: abstract

14: mercy: abstract

15: bricks: concrete

16. fascination: abstract

17. bottles: concrete

18. knowledge: abstract

19. need: abstract

20. temples: concrete

Abstract Nouns List

The following table is a list of more abstract nouns:

Advice for ESL Students & English Language Learners

Nouns are considered the main part of speech in English grammar. They comprise the names of everything in existence, after all. But because of their volume, mastering the different types, rules, and overlapping concepts of nouns can be a huge challenge to English language learners. However, there are a few things that can make language studies a bit easier, not only with nouns but with all the other grammar subjects in the English language, too. The following advice serves that purpose. Read along and consider following them to aid with achieving your language goals.

1. Use Grammar Lists

There are fewer grammar tools that can function as effectively as lists, tables, charts, and diagrams. These tools are valuable in introducing grammar concepts and breaking them down into simplified segments. They can make topics much easier to grasp and almost always contain real-world sentence examples that are great for the acquisition of new workable vocabulary and the construction of sentences. The challenge is picking the ones that work for you. If you can’t find any, you can make your own and customize it according to your own study habits and preferences.

2. Use Audio-Visual Resources

Traditional classes aren’t enough for learning a language. Independent learning should go hand in hand with formal academic training. Since self-studying is a necessity, a great way to maximize it is to learn with the right resources. One effective and smart way to do so is to ensure that you have ample exposure to English media. Incorporating audio-visual materials is both an educational and entertaining way to achieve fluency. TV shows, films, podcasts, dedicated instructional videos, interactive learning software like LillyPad.ai, social media clips, and so on can show you how English speakers (native or otherwise) use the language in different professional, academic, and social contexts. You only need to consume these tools with purpose, which means taking content in with the intention of learning elements of the language. It can go a long way to add some punch to your aptitude.

3. Practical Use

Teachers from all branches of study would share the adage “theory means nothing without practice.” This is especially true when you’re learning languages. Your teachers are simply your guides; they won’t be there to speak or write English for you. The most efficient way to improve your level is to use the language as often as possible. It isn’t uncommon for someone who has impeccable grammar to be horrible at speaking or verbal communication. It’s likely because a major part of their studies is spent on books, not in actual interaction. While it’s true that most English language learners don’t live in areas where English is spoken all the time, there’s always a way to create your own learning environment. You can organize study groups or English clubs with same-minded people. You can nurture friendships both with native and non-native speakers alike. Not only will you have the avenue for practicing English, you can also develop your social and cultural intelligence.

Additionally, it is important for learners to properly understand concrete nouns and common and proper nouns .

Common Errors Made by English Learners

Errors in concrete nouns are rooted in any of the three factors below. Study the table in order to avoid making the same errors:

Learning Strategies and Best Practices with Abstract Nouns

The best way to master concrete nouns is to remember 3 simple things. Let’s take a look at the following list:

- The five senses are sight, smell, touch, taste, and hearing. Nouns that refer to these are sensory words and are therefore concrete.

- If a noun can’t be sensed physically, it’s an abstract noun. “Concept” nouns are all abstract. Most nouns that describe emotions are abstract. You can’t experience it with the senses, but rather experience it in thought or idea.

- Concrete and abstract nouns go hand in hand. We can understand abstract nouns better by adding concrete or sensory qualities to them. Concrete nouns illustrate abstract nouns further.

Abstract Nouns Frequently Asked Questions

Try to figure out the verbs from which these abstract nouns are taken:

1. blockade 2. movement 3. consciousness 4. appointment 5. resistance 6. reflection 7. perception 8. disappearance 9. enjoyment 10. hatred

Try to figure out the adjectives from which these abstract nouns are taken:

1. fragility 2. happiness 3. sincerity 4. gentleness 5. impossibility 6. freedom 7. madness 8. silence 9. dependence 10. responsibility

Abstract nouns are nouns that cannot be grasped by the five senses. This classification is comprised of ideas, emotions, or concepts. If you hate someone, it’s easy to see from your behavior: unreceptive, aloof, or blatantly dismissive. But you can’t actually see the word “hate.” Hate is considered an abstract noun.

No. It’s possible to quantify abstract nouns as long as you confirm that they are countable. For example, the word “skill” refers to a person’s ability to do something, but the word itself can’t actually be seen. It is an abstract noun.

When used generally, it is an uncountable noun. “Bob has skill,” for example. But when used to indicate different kinds of skills it is countable. “Bob has lots of amazing skills.”

All sensory nouns are concrete. A “chair” is a thing you can touch and see, and in some instances even smell or taste if you want to.

You can even hear it if someone hits or throws it. This makes the word a concrete noun. But ideas, emotions, and beliefs don’t have physical forms. Love, Christianity, law, and so on are examples of such and are considered abstract.

Learn from History – Follow the Science – Listen to the Experts

For learners of all ages striving to improve their English, LillyPad combines the most scientifically studied and recommended path to achieving English fluency and proficiency with today’s most brilliant technologies!

What’s the one thing that makes LillyPad so special? Lilly! Lilly’s a personal English tutor, and has people talking all over the world! Lilly makes improving your English easy. With Lilly, you can read in four different ways, and you can read just about anything you love. And learning with Lilly, well that’s what you call liberating!

Additionally, the platform incorporates goal-setting capabilities, essential tracking & reporting, gamification, anywhere-anytime convenience, and significant cost savings compared to traditional tutoring methodologies.

At LillyPad , everything we do is focused on delivering a personalized journey that is meaningful and life-changing for our members. LillyPad isn’t just the next chapter in English learning…

…it’s a whole new story!

Do you want to improve your English? Visit www.lillypad.ai .

Follow us on Facebook or Instagram !

© 2023 LillyPad.Ai

What Are Abstract Nouns And How Do You Use Them?

- What's An Abstract Noun?

- Abstract Vs. Concrete Nouns

- Get Help With Grammar Coach

You probably know that a noun is a word that refers to a person, place, thing, or idea—this is a grammar concept we learn pretty early on in school. And there are, of course, several different types of nouns that we use to refer to all of the things we experience during our lives: We eat food. We meet friends. We go to the store. These nouns refer to the people and physical objects that we interact with.

But what about the things that we can’t actually see or touch? Aren’t words like love , victory , and alliance nouns, too? Yes, they are, and there is a term you may not remember from your grade-school days that we use to refer to these things: the abstract noun.

What is an abstract noun?

An abstract noun is “a noun denoting something immaterial and abstract.” Another common way to think about abstract nouns is that they refer to things that you cannot experience with the five senses . You cannot see, smell, hear, taste, or touch abstract nouns. Abstract nouns refer to intangible things that don’t exist as physical objects.

For example, the word cat refers to a cute animal. You can see and touch a cat. The noun cat is not an abstract noun. On the other hand, the word luck refers to a complex idea about how likely it is that good or bad events are going to happen to someone. Luck doesn’t exist as a physical object; you can’t eat luck nor can you go to a store and buy luck. Luck is an abstract noun because it refers to an intangible concept rather than a physical object that we can experience with our senses.

What about those nouns that you can tangibly sense? Learn more about concrete nouns here.

Abstract noun examples

Unlike most other nouns, abstract nouns don’t refer to people or places. After all, people and places are real things that exist in our world. Even nouns that refer to fictional characters and places, such as Godzilla or Valhalla , are not, the reasoning goes, abstract nouns because these things would have a physical form if they were actually real.

So, all abstract nouns are “things.” Remember, though, that abstract nouns only refer to intangible things such as emotions, ideas, philosophies, and concepts. Let’s stop being abstract and look at some specific examples so we can get a better understanding of abstract nouns.

Even though we often say that we “feel” emotions, we don’t mean that literally. You “feel” emotions like happiness or anger as thoughts in your mind or activity in your brain and body. You can’t hold happiness in your hand or eat a plate of sadness. You can see people or animals expressing these emotions through actions, but emotions are not tangible objects. So, we refer to them with abstract nouns.

- Examples: happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, disgust, joy, fear, anxiety, hope

Ideas, concepts and beliefs

Besides emotions, abstract nouns are also used to refer to other concepts and ideas. These kinds of abstract nouns give names to complex topics and give us a glimpse into a big part of what makes us human—our big, wrinkly brains! While most abstract nouns are common nouns, meaning that they refer to general ideas, they can also be proper nouns, such as Christianity.

- Examples: government, dedication, cruelty, justice, Christianity, Islam, Cubism

List of abstract nouns

Abstract nouns can be pretty tough to understand, so let’s look at a bunch more:

- religion, science, experimentation, research, magnetism, creativity, invisibility, kindness, greed, laziness, effort, speed, concentration, confusion, dizziness, time, situation, existence, death, anarchy, law, democracy, relief, opportunity, technology, discovery, hopelessness, defeat, friendship, patience, decay, holiness, youth, childhood, Stoicism, Marxism

The difference between abstract & concrete nouns

Getting a grasp on what abstract nouns are, exactly, can be tough. While abstract nouns refer to intangible things without a physical form, all of the people, places, and things that do actually have a physical form are referred to by a type of noun: a concrete noun. Unlike abstract nouns, concrete nouns can be experienced with the five senses: they can take a material form rather than an image, say, in your mind’s eye of catness. You can see a tree . You can eat a pineapple. You can hear an engine. You can smell socks. You can touch a lamp.

So, your five senses can help you distinguish between abstract and concrete nouns. Remember, words for fictional people, places, and things are considered to be concrete nouns even if they don’t actually exist in our world. You may not be able to smell a zombie in everyday life, but you would be able to if it were real—just remember to run away if you ever saw one!

Let’s put your noun knowledge to the test with some example sentences. Read each sentence and see if you can figure out if each italicized noun is an abstract noun or a concrete noun.

- Billionaire Jeff Bezos is famous for his wealth.

- Next week, we are going on vacation to Belgium.

- When I grow up, I want to be a superhero.

- They said he was possessed by a ghost.

- The robot had many impressive abilities.

- Her blindness didn’t stop her from being successful.

- I was attacked by a swarm of bees.

- She sells seashells by the seashore.

- We heard shouting from next door.

- The girl just wants attention from her parents.

Good grammar: not an abstract concept

We’ve got a noun for you: genius! And that’s what you’ll be when you check your writing on Thesaurus.com’s Grammar Coach™ . This writing tool uses machine learning technology uniquely designed to catch grammar and spelling errors. Its Synonym Swap will find the best nouns, adjectives, and more to help say what you really mean, guiding you toward clearer, stronger, writing.

Whether you’re writing about a person, place, or thing, perfect grammar has never been easier!

Answers: 1. Abstract 2. Concrete 3. Concrete 4. Concrete 5. Abstract 6. Abstract 7. Concrete 8. Concrete 9. Concrete 10. Abstract

Make Your Writing Shine!

- By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

No judgment here if you don't know the difference between "judgment" and "judgement." Let's read here!

Ways To Say

Synonym of the day

What Is Abstract Noun? Definitions, Rules & Examples

Grammar is an essential aspect of language, and understanding its basic concepts is crucial to effective communication. Abstract nouns are one such concept that can be challenging to comprehend. These nouns represent ideas, feelings, and qualities, making them different from concrete nouns that are tangible objects.

In this article, we will provide a comprehensive guide to abstract nouns, including definitions, rules, and examples to help you grasp the concept.

Table of Contents

What is an Abstract Noun?

An abstract noun is a word that represents a quality, idea, or concept that cannot be physically touched or seen. Unlike concrete nouns that refer to tangible objects, abstract nouns refer to intangible concepts that exist only in the mind. Examples of abstract nouns include:

- Intelligence

Rules for Identifying Abstract Nouns

Here are some rules to help you identify abstract nouns:

- Abstract nouns are always singular.

- They cannot be perceived by the five senses.

- They are usually intangible.

- They can be formed from adjectives, verbs, and common nouns.

- They can be used as the subject of a sentence or the object of a verb.

Examples of Abstract Nouns

Let’s take a look at some examples of abstract nouns in sentences:

- Love is the most powerful emotion.

- Honesty is the best policy.

- Wisdom comes with age and experience.

- Courage is not the absence of fear but the triumph over it.

- Beauty lies in the eyes of the beholder.

- Justice must be served for the greater good.

- Loyalty is a rare and valuable trait.

- Freedom is a fundamental human right.

- Intelligence is the ability to learn and understand.

- Joy is a feeling of great happiness.

Types of Abstract Nouns

Abstract nouns can be divided into different types based on the category they belong to. Here are some of the most common types of abstract nouns:

- Emotions and Feelings : Love, joy, anger, fear, happiness, sadness, hope, etc.

- Concepts and Ideas : Freedom, democracy, justice, democracy, equality, morality, etc.

- Qualities and Characteristics : Honesty, kindness, bravery, intelligence, beauty, etc.

- States and Conditions : Peace, war, health, sickness, poverty, wealth, etc.

Commonly Confused Abstract Nouns

Some abstract nouns can be easily confused with other parts of speech, such as adjectives, verbs, or even concrete nouns. Here are some examples of commonly confused abstract nouns:

- Education vs. Educated: Education is an abstract noun that represents the process of learning, while educated is an adjective that describes someone who has acquired knowledge through education.

- Silence vs. Quiet: Silence is an abstract noun that represents the absence of sound, while quiet is an adjective that describes a low level of noise.

- Idea vs. Opinion: An idea is an abstract noun that represents a concept or thought, while an opinion is a noun that represents a personal belief or viewpoint.

How to Use Abstract Nouns in a Sentence

Using abstract nouns in a sentence can be tricky. Here are some tips to help you use them correctly:

- Use them as the subject of a sentence: Abstract nouns can be used as the subject of a sentence. For example, “Love is a beautiful thing,” where love is the abstract noun.

- Use them as the object of a verb: Abstract nouns can also be used as the object of a verb. For example, “He showed great courage in the face of danger,” where courage is the abstract noun.

- Use them in prepositional phrases: Abstract nouns can also be used in prepositional phrases. For example, “She has a great sense of humor,” where humor is the abstract noun.

- Use them in comparisons: Abstract nouns can be used in comparisons to describe the degree of an attribute. For example, “His intelligence is higher than hers,” where intelligence is the abstract noun.

Tips for Identifying Abstract Nouns

Identifying abstract nouns can be a bit challenging, but with these tips, you’ll be able to identify them with ease:

- Look for nouns that represent qualities, ideas, or concepts that cannot be touched or seen.

- Identify nouns that are intangible and cannot be perceived by the five senses.

- Pay attention to singular nouns, as abstract nouns are always singular.

- Identify nouns that can be formed from adjectives, verbs, or common nouns.

- Look for nouns that can be used as the subject of a sentence or the object of a verb.

- Q. What is the difference between abstract and concrete nouns? A. Concrete nouns refer to tangible objects, while abstract nouns refer to qualities, ideas, and concepts that are intangible.

- Q. Can abstract nouns be plural? A. No, abstract nouns are always singular.

- Q. What are some common examples of abstract nouns? A. Some common examples of abstract nouns include love, joy, courage, beauty, honesty, intelligence, freedom, justice, loyalty, and wisdom.

- Q. Can abstract nouns be used in plural form? A. No, abstract nouns cannot be used in plural form as they represent intangible concepts that cannot be quantified.

In conclusion, abstract nouns represent intangible concepts, ideas, and qualities that cannot be physically touched or seen. They are always singular and cannot be used in plural form. Abstract nouns can be formed from adjectives, verbs, or common nouns, and they can be used as the subject of a sentence or the object of a verb.

By understanding abstract nouns, you can improve your communication skills and use language more effectively. With the help of the tips, rules, and examples provided in this article, you’ll be able to identify and use abstract nouns with confidence.

Related Posts

List of Material Nouns: Essential Vocabulary for English Learners

100 Concrete Nouns List A-Z

List of Possessive Nouns in English

What are Proper Nouns? Definition, Examples

The Ultimate 1000 List of Abstract Nouns from A to Z

Plural Nouns List in English: A Comprehensive Guide

Add comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Abstract Nouns: List of 165 Important Abstract Nouns from A to Z

By: Author English Study Online

Posted on Last updated: November 3, 2023

Sharing is caring!

If you’re learning English, you’ve probably come across these tricky little words before. In this article, we’ll be exploring what abstract nouns are, how to use them, and why they’re important in the English language. We’ll be providing examples of abstract nouns and explaining how they differ from concrete nouns. We’ll also be discussing how to recognize abstract nouns in a sentence and how to use them correctly in your writing.

Table of Contents

Abstract Noun Definition

Abstract nouns are intangible concepts or ideas that cannot be experienced with the five senses. They represent things like emotions , ideas, qualities , and states of being . Unlike concrete nouns that refer to physical objects or things that can be perceived by the senses, abstract nouns cannot be seen, touched, heard, smelled, or tasted.

Examples of abstract nouns include love, peace, hope, freedom, happiness, courage, and honesty . These nouns represent concepts that cannot be measured or quantified, but they are essential to human experience and communication. For example, we use abstract nouns like love to express a deep emotional connection to someone or something.

One way to identify abstract nouns is to think about whether you can see, touch, hear, smell, or taste the thing being described. If you cannot, it is likely an abstract noun. For example, the word “ beauty” is an abstract noun because it is a concept that cannot be seen or touched.

It is important to note that abstract nouns can be difficult to define precisely because they represent intangible concepts. However, they are essential to effective communication and can add depth and nuance to our language. By understanding abstract nouns, we can better express ourselves and connect with others on a deeper level.

Abstract Nouns List

Types of Abstract Nouns

As we mentioned earlier, abstract nouns are intangible ideas that cannot be perceived with the five senses. In this section, we will explore some of the different types of abstract nouns.

Emotions are one of the most common types of abstract nouns. They refer to feelings that we experience, such as love, anger, sadness, and happiness . These emotions cannot be seen or touched, but they can be felt and expressed through language and behavior.

Ideas are another type of abstract noun. They refer to concepts and thoughts that exist in our minds, such as freedom, democracy, justice, and equality . These ideas are not physical objects, but they can have a powerful impact on our lives and society.

Qualities are abstract nouns that describe characteristics or attributes of people, things, or ideas. Examples of qualities include honesty, bravery, intelligence, and creativity. These qualities cannot be seen or touched, but they can be demonstrated through actions and behaviors.

Experiences

Experiences are abstract nouns that refer to events or situations that we encounter in our lives. Examples of experiences include success, failure, adventure, and tragedy . These experiences cannot be physically touched or seen, but they can have a profound impact on our lives and shape who we are as individuals.

Abstract Nouns vs. Concrete Nouns

In English, nouns can be divided into two main categories: abstract nouns and concrete nouns . Abstract nouns are used to describe ideas, concepts, and feelings that cannot be perceived through the senses. Concrete nouns, on the other hand, are used to describe physical objects that can be seen, touched, heard, smelled, or tasted.

- For example, the word “ love ” is an abstract noun because it describes a feeling or emotion that cannot be seen or touched.

- In contrast, the word “ table ” is a concrete noun because it describes a physical object that can be seen and touched.

It is important to understand the difference between abstract and concrete nouns because they are used differently in sentences. Concrete nouns are often used as the subject or object of a sentence, while abstract nouns are often used to describe a quality or attribute of a concrete noun.

- For example, in the sentence “ The dog chased the ball ,” “dog” and “ball” are both concrete nouns because they describe physical objects.

In the sentence “The dog showed loyalty to its owner,” “loyalty” is an abstract noun because it describes a quality of the dog’s behavior.

Here are some more examples of abstract and concrete nouns:

List of Common Abstract Nouns

Usage of abstract nouns.

Abstract nouns play a crucial role in both writing and speech. In this section, we will explore the different ways in which abstract nouns can be used effectively.

Abstract nouns are often used in writing to convey emotions and ideas that cannot be easily expressed through concrete nouns. Here are some ways in which abstract nouns can be used effectively in writing:

- Describing emotions: Abstract nouns such as “love,” “happiness,” and “sadness” can be used to describe emotions in a way that is more impactful than using concrete nouns. For example, instead of saying “She felt a warm feeling in her heart,” we can say “She felt a deep sense of love.”

- Explaining concepts: Abstract nouns can be used to explain complex concepts in a concise and clear manner. For example, instead of saying “The process of photosynthesis involves the conversion of light energy into chemical energy,” we can say “Photosynthesis is the process by which plants convert light energy into chemical energy.”