Children’s Mental Health

Sep 11, 2014

360 likes | 795 Views

Children’s Mental Health. Services Overview Fall Prevention Provider Meeting. What is Mental Health?. Mental health is an integral and essential component of health. The WHO constitution states:

Share Presentation

- mental health

- child adolescent

- mh services

- suicide prevention coordinator

- locating mental health services

Presentation Transcript

Children’s Mental Health Services Overview Fall Prevention Provider Meeting

What is Mental Health? Mental health is an integral and essential component of health. The WHO constitution states: • "Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity." An important consequence of this definition is that mental health is described as more than the absence of mental disorders or disabilities.

What is Mental Health? Mental health is a state of well-being in which an individual realizes: • his or her own abilities, • can cope with the normal stresses of life, • can work productively, and • is able to make a contribution to his or her community. In this positive sense, mental health is the foundation for individual well-being and the effective functioning of a community.

What types of MH problems can children and youth experience? Certain disorders are usually diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood, or Adolescence: • Intellectual Disabilities (formerly referred to as MR) • Learning Disorders • Motor Skills Disorders • Communication Disorders • Pervasive Developmental Disorders & Autism Spectrum Disorders • Attention Disorders • Feeding & Eating Disorders of Infancy or Early Childhood • Tic Disorders • Elimination Disorders • Relational Disorders (RAD, Separation Anxiety, Elective Mutism)

Can Children & Youth have the same disorders as Adults? YES! While certain diagnoses typically have an onset in adulthood, children can suffer from Serious Emotional Disturbance including: • Anxiety • Depression • Thought disorders (like schizophrenia) • Psychosis • Substance Use Disorders • Bipolar Disorders (although often over-diagnosed)

How are Children & Youth needing MH Services identified? Society Children are involved in multiple systems, similar to a set of concentric layers. Anyone within the child’s “layered” systems can identify a MH need and refer the family to MH services. School Family Community

What MH Services are available to children? School-Based MH service providers Traditional culture specific helpers/healers Child Public MH service providers Faith-Based MH service providers Family Private Non-Profit MH service providers Private Practice & “For Profit” MH service providers

How do Children access Public MH services? There are 37 Community MH Centers in Texas, called Local MH Authorities, and 1 Behavioral Health Organization (NorthStar) in the Dallas area. • The following link to the DSHS website provides information on locating mental health services in all Texas counties. http://www.dshs.state.tx.us/mhservices-search/

What Children are eligible for Community MH Center services? DSHS Children’s Mental Health serves: • Children ages 3 through 17, • Who have a diagnosis of mental illness (excluding a single diagnosis of substance abuse, intellectual disabilities, autism or pervasive development disorder), • Who exhibit serious emotional, behavioral or mental disorders and who: • Have a serious functional impairment; or • Are at risk of disruption of a preferred living or child care environment due to psychiatric symptoms; or • Are enrolled in a school system’s special education program because of serious emotional disturbance.

Nature of CMH Services • CMH Services are based on the philosophy and principles associated with Systems of Care • Services are child focused and family driven • Services are based on evidence-based practices • Treatment planning is a collaborative endeavor between the family and the CMH treatment staff • Mental Health services and Substance Abuse Prevention and Treatment services are integral parts of the Systems of Care model

Screening for MH Services Screening: A process where staff from the local mental health authority/community mental health center, talks to the parents (or LAR) and child to gather information to determine if there is a need for a detailed mental health assessment. This can be conducted either face-to-face or over the phone.

Assessment A licensed professional will meet with the parent and child face-to-face to ask questions about: • the child's mental health • emotional and behavioral issues • relationships at home and with friends • health history • development • schoolwork • and other information needed to complete the assessment.

CMH Service Array Outpatient Services include: • Counseling/psychotherapy • Case management • Skills development training • Medication training and support • Family Partner services • Access to a psychiatrist • Flexible funds for non-traditional supports

CMH Service Array Crisis Services include: • Crisis Hot Line • Mobile Crisis Outreach Team • Access to state psychiatric hospital if clinically indicated

Crisis Services A child/adolescent seeking crisis services must meet the definition of a crisis cited in the Community Standards Rule: Crisis: A situation in which because of a mental health condition: • the child/adolescent presents an immediate danger to self or others • the child/adolescent’s mental or physical health is at risk of serious deterioration, or • a child/adolescent believes he/she presents as an immediate danger to self or others

What do I do if I think a child is Suicidal? A.S.K about suicide to Save a Life • Ask the question: • “Are you thinking of killing yourself?” -OR- • “Are you so upset you are thinking of taking your own life?” • -OR- “Are you thinking of suicide?” • Safety & SeekHelp: • Keep the child SAFE do not leave them alone • Know When & How to Refer: • Know the Resources for your town & Refer to a Mental Health Professional

Resources & How to ASK • Moderate RISK: • Take all Signs Seriously • Access Mental Health Services • Call National Line for a referral • PEOPLE who can HELP • School Counselor • Mental Health Professional • Counselor • Social Worker • Faith based Leader • High RISK: • Take Immediate Action • 911, go to ER • Notify Parents/ guardians Resources: • Local Crisis Hotline • MCOT Team • Local Mental Health Authority for your Region • Call National Suicide Prevention Hotline 1-800-273 TALK

LMHASuicide Prevention Coordinator • Each LMHA designates a Suicide Prevention Coordinator to work collaboratively with local staff, LMHA suicide prevention staff statewide, and DSHS’s Suicide Prevention Office to reduce suicide deaths and attempts by: • Develop collaborative relationship local suicide prevention coalition (There are 28 statewide!) • Participating in conference calls with DSHS Suicide Prevention Coordinator • Participating in the development of the local Community Suicide Postvention Protocols (as described by the CDC Postvention Guideline) • Participating in local Community Suicide Postvention Protocols • Participating in local community suicide prevention efforts.

Contact Information • Jenna Heise, Suicide Prevention Officer [email protected] (512) 776-3407 • Michael Hastie, CMH Lead [email protected] (512) 776-3186

- More by User

GERIATRIC MENTAL HEALTH 101

GERIATRIC MENTAL HEALTH 101 A Presentation By Michael B. Friedman, LMSW Chairperson The Geriatric Mental Health Alliance of New York Why Geriatric Mental Health Is Important Mental Disorders Are a Major Impediment to Living Well in Old Age.

4.01k views • 44 slides

Mental Health 101 for Non-Mental Health Providers

Mental Health 101 for Non-Mental Health Providers. Developed by Faculty and Staff of the University of Maryland & Prince Georges County Public School System .

1.61k views • 87 slides

Mental Health and NCHS data: an under-explored resource

Mental Health and NCHS data: an under-explored resource. Laura A. Pratt, PhD National Center for Health Statistics Data Users’ Conference July 11, 2006. Importance of mental illness in health research. Mental illness causes suffering in patients and families.

1.05k views • 35 slides

Update on Evidence-Based Practices in Iowa’s Public Mental Health System

MHMRDDBI Commission Update May 17, 2007. Update on Evidence-Based Practices in Iowa’s Public Mental Health System . Michael Flaum, MD Iowa Consortium for Mental Health Department of Psychiatry University of Iowa, Carver College of Medicine. Overview. Why the push for EBP’s?

1.36k views • 85 slides

Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Children and Families in the Juvenile Court

Addressing the Mental Health Needs of Children and Families in the Juvenile Court. “Busting Myths, Breaking Barriers” January 9, 2008 Phoenix, Arizona Presented by: Tom C. Rawlings Director, Office of the Child Advocate State of Georgia [email protected] www.tomrawlings.com

1.25k views • 100 slides

Illinois Department of Human Services / Division of Mental Health and Illinois Mental Health Collaborative Present

Illinois Department of Human Services / Division of Mental Health and Illinois Mental Health Collaborative Present. March 2009. ICG Claims Submission Training. ICG Claims.

1.25k views • 96 slides

Mental Status Assessment

Mental Status Assessment. Physical Examination and Health Assessment. Learning Objectives for Mental Health Assessment. Define the behaviors that are considered in an assessment of a person’s mental status Describe relevant developmental considerations of the mental status exam.

1.8k views • 29 slides

Mental Health Response in Times of Disaster

Mental Health Response in Times of Disaster. Michelle Bowman, RN. MSN. Santa Barbara County ADMHS CARES/Mobile Crisis . OBJECTIVES. Define Disaster Identify phases of disaster Identify reactions in each of the phases Understand basic concepts of Disaster Mental Health

1.47k views • 75 slides

Understanding People with Developmental Disabilities, Mental Illness, and/or Special Health Care Needs

Understanding People with Developmental Disabilities, Mental Illness, and/or Special Health Care Needs. Tri City Partnership for Special Children & Families First Responder Smart Card Program TM. Performance Objectives.

1.41k views • 105 slides

A review of Mental Health Law in Pakistan

A review of Mental Health Law in Pakistan. Presentation by Rubeena Kidwai, Ph.D. Consultant Clinical Psychologist Hubert H. Humphrey Fellow 2010-2011. History of mental health law in Pakistan. 1912 - Mental health law introduced in Indo-Pak subcontinent (then India) – Lunacy Act 1912

1.49k views • 13 slides

Illinois Department of Human Services / Division of Mental Health and Illinois Mental Health Collaborative Present. December 2008. Introduction To IntelligenceConnect and Reporting. Agenda. Introductions Access IntelligenceConnect Claims Reports Review Available Reports/Data Set

1.02k views • 85 slides

MENTAL HEALTH FIRST AID

MENTAL HEALTH FIRST AID. A Collaborative Partnership of National Council for Community Behavioral Healthcare, Maryland State Department of Mental Hygiene and Missouri Department of Mental Health. Mental Health First Aid.

1.41k views • 16 slides

“ Mental Health Research: What are the risks of that happening ?

Professor Paul Rogers Professor of Forensic Nursing Faculty of Health, Sports and Science. “ Mental Health Research: What are the risks of that happening ?. Aim. Give a rough overview of my career.

1.09k views • 78 slides

The Impact of Mental Health Substance Abuse on Student Success

The Impact of Mental Health Substance Abuse on Student Success. Mental Health on Campus: We all Play a Part! Ohio Program for Campus Safety and Mental Health Conference May 20, 2014 Columbus State Community College Conference Center.

1.28k views • 97 slides

MENTAL HEALTH

MENTAL HEALTH. NORMALITY, MENTAL HEALTH AND MENTAL ILLNESS. Normality. Generally psychologists agree that normality refers to patterns of behaviour or personality traits that are typical.

2.48k views • 182 slides

MENTAL HEALTH Group D Trey Perez Heather Rawls DJ Reid

MENTAL HEALTH Group D Trey Perez Heather Rawls DJ Reid. Agenda. Mental health overview Previous Legislation Current Legislation Republican and Democratic views Policy and Fiscal Implications Proposed Legislation. What is Mental Health.

1.03k views • 83 slides

Global Mental Health: Focus on Latino Populations

Global Mental Health: Focus on Latino Populations. Javier I Escobar MD Associate Dean for Global Health and Professor of Psychiatry and Family Medicine, UMDN-Robert Wood Johnson Medical School September 2011. Local Health International Health. Global Health. GLOBAL HEALTH.

1.02k views • 79 slides

The Facts About CYMH

Child and Youth Mental Health: the Realities Dr. Simon Davidson Chair, Child & Youth Advisory Committee, Mental Health Commission of Canada; Chief Strategic Planning Executive, Centre of Excellence for Child & Youth Mental Health at CHEO Toronto, Ontario November 6, 2009. The Facts About CYMH.

1.77k views • 137 slides

Mental Health First Aid

Mental Health First Aid. What are Mental Health Problems?. There are a number of terms used to describe Mental Health problems: mental disorder mental ill-health mental illness nervous exhaustion mental breakdown nervous breakdown Burnout cracked up stressed out psycho.

1.72k views • 64 slides

National Mental Health Programme

National Mental Health Programme. National Mental Health Programme. Govt of India integrated mental health with other health services at rural level. It is being implemented since 1982 and Maharashtra was the first state to implement NMHP. Objectives.

12.04k views • 17 slides

Mental Illness in Children and Adolescents: Early Detection is the key

Mental Illness in Children and Adolescents: Early Detection is the key. Introduction – self and topic Alarming Statistics Define Mental Illness/Good mental health Why is this important Children at risk and triggers Types of Mental illness and Indicators What can be done An action Plan.

1.03k views • 72 slides

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Stakeholder Engagement

- Connect with NIMH

- Digital Shareables

- Science Education

- Upcoming Observances and Related Events

Resources for Students and Educators

The National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) offers a variety of learning resources for students and teachers about mental health and the brain. Whether you want to understand mental health challenges, promote emotional well-being in the classroom, or simply learn how to take care of your own mental health, our resources cover a wide range of topics to foster a supportive and informed learning environment. Explore videos, coloring books, and hands-on quizzes and activities to empower yourself and others on the journey to mental well-being.

You can also find additional educational resources about mental health and other topics on NIH’s STEM Teaching Resources website .

Childhood Irritability : Learn about symptoms of irritability, why it's important to study irritability, NIMH-supported research in this area, and new treatments for severe irritability in youth.

Get to Know Your Brain: Your brain is an incredible and complex organ! It helps you think, learn, create, and feel emotions, and it controls every blink, breath, and heartbeat. Learn more about the parts of the brain and what each area helps control.

NIMH Deputy Director Dr. Shelli Avenevoli Discusses the Youth Mental Health Crisis: Learn about youth suicide, the effects of technology and the pandemic on the developing brain, and tips for supporting the mental health of youth.

Getting to Know Your Brain: Dealing with Stress: Test your knowledge about stress and the brain. Also learn how to create and use a “ stress catcher ” to practice strategies to deal with stress.

Coloring and activity books

Print or order these coloring and activity books to help teach kids about mental health, stress, and the brain. These are available in English and Spanish.

Get Excited About Mental Health Research!

This free coloring and activity book introduces kids to the exciting world of mental health research.

Stand Up to Stress!

This free coloring and activity book teaches children about stress and anxiety and offers tips for coping in a healthy way.

Get Excited About the Brain!

This free coloring and activity book for children ages 8-12 features exciting facts about the human brain and mental health.

Quizzes and activities

Use these fun, hands-on activities in the classroom or at home to teach kids about mental health.

Teen Depression Kahoot! Quiz

Engage students in fun and interactive competition as they learn about depression, stress and anxiety, self-care, and how to get help for themselves or others.

Stress Catcher

Life can get challenging sometimes, and it’s important for kids (and adults!) to develop strategies for coping with stress or anxiety. This printable stress catcher “fortune teller” offers some strategies children can practice and use to help manage stress and other difficult emotions.

Brochures and fact sheets

Below is a selection of NIMH brochures and fact sheets to help teach kids and parents about mental health and the brain. Additional publications are available for download or ordering in English and Spanish.

Children and Mental Health: Is This Just a Stage?

This fact sheet presents information on children’s mental health including assessing your child’s behavior, when to seek help, first steps for parents, treatment options, and factors to consider when choosing a mental health professional.

The Teen Brain: 7 Things to Know

Learn about how the teen brain grows, matures, and adapts to the world.

How to Talk to Your Child About Their Mental Health

Know the warning signs.

Learn the common signs of mental illness in adults and adolescents.

Mental Health Coloring & Activity Book

Download NAMI’s “Meet Little Monster” children’s activity book.

Find Your Local NAMI

Call the NAMI Helpline at

800-950-6264

Or text "HelpLine" to 62640

Talking with your child about emotional topics, such as their mental health, can feel uncomfortable. This can be due to the stigma involved, lack of information or even fears of possible blame.

It may seem much easier to talk about other medical problems, such as food allergies, asthma or diabetes. There is typically more information available about those conditions, they are easy to diagnosis with medical tests and people seldom think they are anyone’s fault.

Too frequently, people blame mental health challenges on the person experiencing them by saying they aren’t trying hard enough, or they are doing something wrong. In result, we can feel like it’s our “fault,” or even our child’s “fault,” when they are facing mental health challenges.

However, openly talking to your children is a great way to help decrease this stigma. It can be tough to know how to start the conversation — let’s consider some helpful ways to talk with your children about their mental health.

“Meet Little Monster” Coloring & Activity Book

To help foster dialogue between children and the safe adults in their lives, as well as provide children a tool for helping express and explore their feelings in a fun, creative and empowering way, NAMI offers “Meet Little Monster,” a mental health coloring and activity book, available for download at no-cost.

Created by NAMI Washington, “Meet Little Monster” was developed in response to both the COVID-19 pandemic, when children were suddenly cut off from their friends, teachers, coaches, club leaders and school counselors, and the Black Lives Matter protests for racial justice after the murder of George Floyd. The book also includes a list of mental health resources.

Download “Meet Little Monster” Coloring & Activity Book

- Download in English

- Download in Spanish

- Download in Arabic

- Download in Korean

- Download in Mandarin

- Download in Vietnamese

Make an Analogy to a Medical Problem

Children often hear about their medical problems. They understand that if they have asthma, their lungs and airways tighten up in response to dust, pets, cold or exercise. They know that the wheezing makes them uncomfortable, so they need to take medications for relief and avoid situations that may trigger an attack.

Similarly, you can let your child know that mental health concerns, like anxiety, depression, ADHD and OCD, among others, are also physical conditions that start with their brain. The brain controls feelings, thoughts and behavior — like the “central headquarters” of the body. Sometimes, the brain gets “knocked off balance,” but, like other medical problems, they can learn to manage this with treatment, which can include medications and behavioral support (stress reduction, relaxation, psychotherapies, etc.).

Give Them Concrete Explanations

Children can understand mental health issues better if they have a concrete explanation. Here is an example of how you could explain panic attacks:

“If you walked across the street and a car was about to hit you, you would jump out of the way, feel scared, have a racing heart, feel dizzy or hyperventilate (breathe too fast). All of this is a normal fight-or-flight response to a real threat of danger. A panic attack can include all the same physical and emotional reactions, except there is no car about to hit you. And while this might seem scary, there are ways to deal with it.

Many times, panic attacks happen in ‘normal’ situations, such as going to school, riding in a car, going up in elevators, and in other settings that are not actually dangerous. If you had panic disorder, you would most likely associate those places with panic. In other words, your brain would react as if something bad is going to happen, maybe even just from thinking about those situations.”

Listen to Them and Validate Their Experiences

Because there is often stigma attached to mental health conditions, children can feel ashamed to talk about their worries, obsessions, compulsions, impulsivity and other behavioral problems. Talk with them about what they are experiencing. Listen with curiosity and empathize with them.

It may be helpful to tell your child about other people who experience similar problems. If you or someone else your child trusts have mental health conditions, explain that the same way you would tell them about diabetes. These things can run in families, and they are not the only people who feel this way. If you or a family member can have a conversation with your child about their own mental health and how they manage it, it can be very reassuring.

Be Sure They Know This Is Not Their Fault

Many children with mental health conditions can feel that their condition is their fault or that it is an unchangeable feature of their personality or their identity. Stigma and misinformation often reinforce these feelings. You can help them see that mental health conditions are common and that it is not a sign that something is wrong with them as a person. Emphasize their strengths so they don’t see their mental health condition as the most important part of who they are.

Have Frequent Conversations

Many mental health conditions are considered intermittent — the symptoms can come and go throughout life and may fluctuate in severity depending on age, level of stress or any number of factors. It helps to have conversations about emotions, thoughts and behaviors that are a part of your child’s condition from the time it begins.

As they grow up, become more mature and are better able to understand themselves and their condition, your child will see you as a trusted resource they can consult if they have a relapse or experience new symptoms. Although it may not always be easy, maintaining an open and understanding relationship can be critical. Touching base with your child about their experiences is the best way to identify any new or developing issues and ensure they have the right treatment and support.

Let Them Ask You Questions

Children will have all sorts of questions about their symptoms and treatment, so being open and giving them information about the ways therapy and/or medications can help will be reassuring. If you do not have all the best information, plan to meet with your child and their mental health clinician together to discuss the problem and their questions. If your child asks a question you don’t know the answer to, it’s ok to say you don’t know and then work together to find an answer.

Include the Family

Ideally, a mental health condition should not be a secret. Your child may feel more secure if their siblings/ grandparents/others in the family know about it, can talk with them about it and accept it — just as they would accept any other medical problem, like diabetes. This kind of transparency is incredibly helpful to prevent feelings of shame or isolation.

Discuss Self-Care and Prevention

Mental health conditions are a complex interaction between biology, psychology and environmental factors. Teaching your child to practice self-care, including maintaining a healthy diet, exercising regularly, meditating and getting sufficient sleep, are instrumental in preventing relapses and diminishing symptoms.

Don’t Be Afraid to Ask About Suicide

In recent years, rates of death by suicide and suicidal thinking have increased in young people. Many parents and caregivers are wary of asking a child if they have suicidal thoughts, intentions or plans. They may be afraid that starting the conversation may cause suicidal behavior, but this connection has proven to be false . Asking about suicide may be a relief for people of all ages. If your child has a mental health condition, it’s important to check-in with them about suicidal thoughts .

Talking with your child about their mental health condition is not easy. However, you are more than capable of opening a dialogue.

- Trying to Conceive

- Signs & Symptoms

- Pregnancy Tests

- Fertility Testing

- Fertility Treatment

- Weeks & Trimesters

- Staying Healthy

- Preparing for Baby

- Complications & Concerns

- Pregnancy Loss

- Breastfeeding

- School-Aged Kids

- Raising Kids

- Personal Stories

- Everyday Wellness

- Safety & First Aid

- Immunizations

- Food & Nutrition

- Active Play

- Pregnancy Products

- Nursery & Sleep Products

- Nursing & Feeding Products

- Clothing & Accessories

- Toys & Gifts

- Ovulation Calculator

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- How to Talk About Postpartum Depression

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

How to Support Your Child's Mental Health

paulaphoto / Getty Images

- Why Mental Health Is Important

- How to Support Mental Health

When to Get Outside Help

Most parents excel at keeping their kids physically healthy. They work to ensure they are eating well, getting their immunizations, and staying physically active. But a child's emotional and mental well-being is just as important to their quality of life as being physically healthy.

Supporting your child's mental health—just as you would their physical health—helps your child develop the resilience they need to deal with obstacles while growing into well-rounded and mentally healthy adults.

"Our mental health is connected to every aspect of our lives such as our physical, emotional, relational, and spiritual well-being," says Kerry Heath , LPC-S, NCC, CEDS-S, a licensed professional counselor with Choosing Therapy. "Each of these aspects of our lives are interrelated. If/when one or more areas are impacted, our mental health is likely to be adversely affected."

Why a Child's Mental Health Is Important

When a child has good mental health, they are able to think clearly, make friends , and learn new things. They also develop self-confidence, build self-esteem, practice perseverance, learn to set goals, practice making decisions, learn coping skills, manage difficult emotions, and develop a healthy emotional outlook on life.

Learning these skills is not always easy and takes practice, especially if your child has a mental health issue like depression or anxiety . In fact, experiencing mental health issues is not that uncommon.

According to the American Psychological Association, an estimated 15 million young people in the US are diagnosed with a mental health disorder and many more are at risk of developing a disorder.

Left untreated, these mental health issues can have a significant impact on a child's life. Elementary school children with mental health issues are more likely to miss school and they are three times more likely to be suspended or expelled than their peers. Plus, there are long-term consequences to consider as well, like other mental disorders or chronic medical conditions.

"Also, early life mental health issues can lead to mental health and/or substance abuse disorders in adulthood," explains Heath. "It is crucial that children are taught effective coping skills to avoid the use of ineffective behaviors later in life...to manage emotions."

Parents can counteract these statistics by not only supporting their child's mental health but also getting them the help they need when they are facing mental obstacles. Here is what you need to know about supporting your child's mental health.

If you or a loved one are struggling with mental health issue contact the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) National Helpline at 1-800-662-4357 for information on support and treatment facilities in your area.

For more mental health resources, see our National Helpline Database .

How Parents Can Support Mental Health

Being mentally healthy during childhood means reaching developmental and emotional milestones, learning healthy social skills, and knowing how to cope with problems. Mentally healthy children have a good quality of life and can function well at home, in school, and in their communities.

But being mentally healthy doesn't just happen organically. Parents and caregivers play a crucial role in fostering good mental health, seeking support when it's needed, and guiding their kids through life. Here are some ways to support your child's mental health.

Show Unconditional Love

One of the most important ways to support your child's mental health is to show unconditional love, says Jenni Torres, MEd, a former teacher and senior vice president of curriculum and instruction for nonprofit Waterford.org . Regularly let your kids know that no matter what they are facing or dealing with that you love them unconditionally and that you are there for them.

Kids need to understand that we all make mistakes but that we can learn from these mistakes, she says. Make sure you are framing your child's mistakes as a way of learning instead of communicating failure. Even if you are disappointed in a poor choice, your child should know that the disappointment you feel has no bearing on your love for them.

Praise Their Character

Encouragement, praise, and affirmations are all ways in which parents can not only build their child's self-confidence and self-esteem but more importantly, support their mental health. Research shows that low self-esteem is associated with anxiety, depression, and academic stress, which all significantly affect a child's quality of life. Low self-esteem can even lead to suicidal ideation.

Kerry Heath, LPC-S, NCC, CEDS-S

Praise children for character traits more often than physical traits or achievement-oriented things.

"Praise children for character traits more often than physical traits or achievement-oriented things," says Heath. "Children respond well to positive reinforcement, and we want to reinforce the things we want to be repeated, such as being kind, showing empathy, [and] helping others."

Spend Time Together

Spending time together as a family not only strengthens family bonds but also gives parents much-needed face-time with their kids to learn what they are struggling with, and what their dreams are. It sends the message that your kids are important and that you care what's happening in their lives. You also will be more likely to recognize issues in your child's life if you are regularly spending time together.

"Parents can make time for their children by doing things like having family meals, taking walks together, completing projects together, assisting with homework, or playing games with one another," says Heath.

Heath says you also should get to know your child's friends. "Show your children that you care about the people they care about as well," Heath says. Plus, you can provide input when they are in unhealthy relationships or friendships as well as guide them on how to be a healthy friend.

Communicate Regularly

Talking on a consistent basis means you can help your child problem-solve difficult situations. You also can serve as a sounding board for them to talk about the emotions they are dealing with. "Open communication allows kids to feel free to explore their feelings," Torres says. "Parents are more likely to notice when things are amiss if they are talking with their child consistently."

Heath suggests asking open-ended questions. One place to start is to get them to share about their day after school, a party, or a special event. Getting your child to share these things—both the good and the bad—will provide opportunities for you to help them troubleshoot.

Build Trust

"One of the foundational needs of children is to feel safe," adds Torres. "When kids feel safe, they develop appropriately and learn appropriately. There also is less likelihood of mental health challenges and when mental health challenges do occur, they are just biological consequences."

One way to foster those feelings of safety and trust is to create an environment in your home where it is safe for your kids to discuss their feelings and struggles, says Heath. You can do that, she says, by being a good role model .

"Children learn by example," Heath says. "If they see that it is acceptable to share struggles and challenges, they will be more likely to come to parents with their own."

Although making the decision to seek the help of a mental health professional is not always easy for parents, it is one that is wise.

"Often when we see something happening with our children, we can sometimes feel like we failed, which can stop us from seeking help," says Torres. "But if we do take that step, we find out we are not alone, that others are experiencing the same things, and that we were not a failure. Instead of letting shame stop them, parents should take that step to speak up."

Torres also believes that parents shouldn't wait until things get bad or unmanageable before reaching out for help. Instead, she encourages them to be proactive about getting their child support so that they can learn healthy coping strategies, build resilience, and learn to manage difficult situations and emotions.

Signs Your Child May Need Outside Help

While every child experiences emotional ups and downs, there are some red flags that indicate that they may need to see a healthcare provider or a mental health professional. Reach out to someone right away if your child displays any of these red flags:

- Displays excessive worry or anxiety

- Appears less confident or feels bad about themselves

- Withdraws from you, their friends, or activities they used to enjoy

- Displays significant changes in eating or sleeping habits

- Struggles academically or has issues with friends

- Expresses hopelessness, seems depressed, or talks about suicide

- Engages in negative behaviors more often

- Talks about or participates in self-harming behaviors

- Participates in self-destructive behaviors or has issues with impulse control

- Seems overly irritable, emotional, or easily upset

- Makes comments like "Nobody would notice if I ran away"

Overall, if you are concerned about your child—even if their actions or attitude are not on this list—talk to a healthcare provider. They can help you determine what is normal and what is not based on your child's age and development. And most importantly they can make sure your child gets the help they need.

A Word From Verywell

When it comes to your child's mental health, it is important to be a consistent part of your child's life, not only talking with them but spending time together as well. Your child's mental health will benefit significantly from your involvement in their lives as well as your guidance, unconditional love, and your support.

By building trust, demonstrating strong communication skills, and being a good role model, you will have established a strong foundation for your child's mental health. And remember, part of supporting your child's mental health means getting them help or support when they need it.

You are the expert on your child. If they are acting in a way that seems strange or worrisome to you, talk to a healthcare provider. It is the most supportive and courageous thing you can do to get your child help when they need it, so don't let fear or embarrassment keep you from reaching out. With proper treatment and intervention, they will learn to care for their mental well-being.

American Psychological Association. Children's mental health .

How Mental Health Disorders Affect Youth . Youth.Gov

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is children's mental health . Updated September 23, 2021.

Nguyen DT, Wright EP, Dedding C, Pham TT, Bunders J. Low self-esteem and its association with anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation in Vietnamese secondary school students: a cross-sectional study . Front Psychiatry . 2019;10:698. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00698

Cleveland Clinic. Signs that your child may need a therapist . Updated March 31, 2021.

By Sherri Gordon Sherri Gordon, CLC is a published author, certified professional life coach, and bullying prevention expert.

Mental health of children and parents —a strong connection

The mental health of children is connected to their parents’ mental health. A recent study found that 1 in 14 children has a caregiver with poor mental health. Fathers and mothers—and other caregivers who have the role of parent—need support, which, in turn, can help them support their children’s mental health. CDC works to make sure that parents get the support they need.

A child’s mental health is supported by their parents

Being mentally healthy during childhood includes reaching developmental and emotional milestones and learning healthy social skills and how to cope when there are problems. Mentally healthy children are more likely to have a positive quality of life and are more likely to function well at home, in school, and in their communities.

A child’s healthy development depends on their parents—and other caregivers who act in the role of parents—who serve as their first sources of support in becoming independent and leading healthy and successful lives.

The mental health of parents and children is connected in multiple ways. Parents who have their own mental health challenges, such as coping with symptoms of depression or anxiety (fear or worry), may have more difficulty providing care for their child compared to parents who describe their mental health as good. Caring for children can create challenges for parents, particularly if they lack resources and support, which can have a negative effect on a parent’s mental health. Parents and children may also experience shared risks, such as inherited vulnerabilities, living in unsafe environments, and facing discrimination or deprivation.

Poor mental health in parents is related to poor mental and physical health in children

A recent study asked parents (or caregivers who had the role of parent) to report on their child’s mental and physical health as well as their own mental health. One in 14 children aged 0–17 years had a parent who reported poor mental health, and those children were more likely to have poor general health, to have a mental, emotional, or developmental disability, to have adverse childhood experiences such as exposure to violence or family disruptions including divorce, and to be living in poverty.

Fathers are important for children’s mental health

Fathers are important for promoting children’s mental health, although they are not as often included in research studies as mothers. The recent study looked at fathers and other male caregivers and found similar connections between their mental health and their child’s general and mental health as for mothers and other female caregivers.

Supporting parents’ mental health

Supporting parents, and caregivers who act in the role of parent, is a critical public health priority. CDC provides parents with information about child health and development , including positive parenting tips , information and support when parents have concerns about their child’s development , or help with challenging behavior . CDC supports a variety of programs and services that address adverse childhood experiences that affect children’s and parents’ mental health, including programs to prevent child maltreatment and programs that support maternal mental health during and after pregnancy . CDC also examines issues related to health equity and social determinants of health , including racism, that affect the emotional health of parents and children. More work is needed to understand how to address risks to parents’ mental health.

To help parents and other adults with mental health concerns in times of distress, CDC funded the web campaign How Right Now as a way to find resources and support. CDC is also funding the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine to develop an online resource for parents to learn skills to cope with emotions and behavior using evidence-based approaches to improving mental health, which will be released this summer.

More Information

- CDC’s Children’s Mental Health

- CDC’s Child Development

- CDC’s Positive Parenting Tips

- CDC’s Information on Adolescent Mental Health

- CDC’s Information on Parenting Teens

- CDC’s Information on Depression During and After Pregnancy

- CDC’s Information on Managing Stress and Anxiety during a Pandemic

- HHS Information on Supporting Families

- HHS Information on Engaging Fathers

Wolicki SB, Bitsko RH, Cree RA, et al. Associations of mental health among parents and other primary caregivers with child health indicators: Analysis of caregivers, by sex—National Survey of Children’s Health, 2016–2018, Adversity and Resilience Science: Journal of Research and Practice. Published online April 19, 2021 [ read summary ]

To receive email updates about this topic, enter your email address:

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

Child and Adolescent Mental Health

Published by Jayson Hensley Modified over 5 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "Child and Adolescent Mental Health"— Presentation transcript:

‘Adjusting to Life Events and Their Impact on Mental Health.’

Impact of Family Violence on Adult Victims Death Physical injury (including gynaecological problems) Miscarriage Anxiety and depression Substance.

Child Development What is “Normal” Anyway?. Important Concepts in Child Development Wide range of development is “normal” Different temperament types.

Guided Reading Activity 31

Children & Mental Health Presented By: Marianne Bates.

Helping schools to support young people with mental health needs. 24 th October 2014 Oakwood House – John Wiggin Room.

DEPRESSION IN SCHOOL. 1.WHAT IS DEPRESSION? 2.WHO SUFFERS FROM DEPRESSION? 3.TYPES OF DEPRESSION. 4.CAUSES. 5.SYMPTOMS. 6.TREATMENT.

CHILD PSYCHIATRY Fatima Al-Haidar Professor, child & adolescent psychiatrist College of medicine - KSU.

BELL WORK Why do you think people who are abused are afraid to get help?

Separation Anxiety Disorder (SAD) By Samuel Mejia P.1.

Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. Externalizing Disorders Disorders with behaviors that are disruptive and often aggressive Attention-deficit.

Mental Health of Children & Adolescents: The work of the Child and Family Consultation Service Dr. Joshua Westbury Consultant Child and Adolescent Psychiatrist.

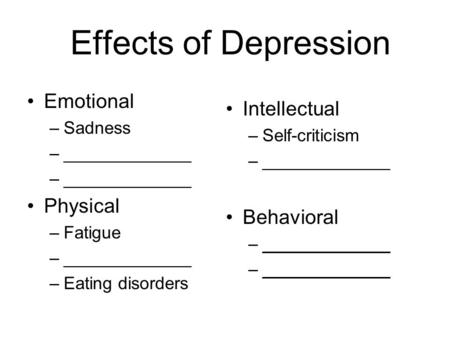

Effects of Depression Emotional –Sadness –_____________ Physical –Fatigue –_____________ –Eating disorders Intellectual –Self-criticism –_____________.

1 Typical or Troubled? TM Presentation for Teachers & Staff Typical or Troubled? TM Know the Difference, Make a Difference A Program of the American Psychiatric.

Youth and Co-Occurring Disorders. Disorders First Diagnosed in Infancy, Childhood or Adolescence Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity.

Sleep changes (insomnia to hypersomnia) Appetite changes (loss of to over eating) Arousal changes (lethargic to manic)

Expanding Awareness of Mental Health in Childhood and Adolescence Yasong Du Shanghai Mental Health Center Shanghai Jiaotong University.

Is a behavioural, emotional or cognitive pattern of functioning in an individual that is associated with distress, suffering, or impairment in one or.

Categories of Mental Disorders 1 Child and youth mental health problems can be classified into two broad categories: 1Internalizing problems withdrawal.

200 pt 300 pt 400 pt 500 pt 100 pt 200 pt 300 pt 400 pt 500 pt 100 pt 200 pt 300 pt 400 pt 500 pt 100 pt 200 pt 300 pt 400 pt 500 pt 100 pt 200 pt 300.

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

- Open access

- Published: 14 September 2023

Children and youth’s perceptions of mental health—a scoping review of qualitative studies

- Linda Beckman 1 , 2 ,

- Sven Hassler 1 &

- Lisa Hellström 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 23 , Article number: 669 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

4721 Accesses

Metrics details

Recent research indicates that understanding how children and youth perceive mental health, how it is manifests, and where the line between mental health issues and everyday challenges should be drawn, is complex and varied. Consequently, it is important to investigate how children and youth perceive and communicate about mental health. With this in mind, our goal is to synthesize the literature on how children and youth (ages 10—25) perceive and conceptualize mental health.

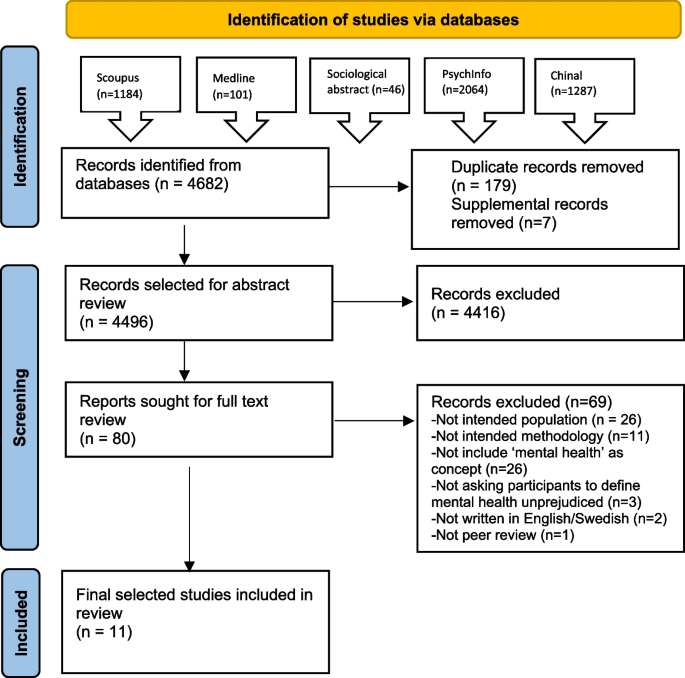

We conducted a preliminary search to identify the keywords, employing a search strategy across electronic databases including Medline, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Sociological abstracts and Google Scholar. The search encompassed the period from September 20, 2021, to September 30, 2021. This effort yielded 11 eligible studies. Our scoping review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA-ScR Checklist.

As various aspects of uncertainty in understanding of mental health have emerged, the results indicate the importance of establishing a shared language concerning mental health. This is essential for clarifying the distinctions between everyday challenges and issues that require treatment.

We require a language that can direct children, parents, school personnel and professionals toward appropriate support and aid in formulating health interventions. Additionally, it holds significance to promote an understanding of the positive aspects of mental health. This emphasis should extend to the competence development of school personnel, enabling them to integrate insights about mental well-being into routine interactions with young individuals. This approach could empower children and youth to acquire the understanding that mental health is not a static condition but rather something that can be enhanced or, at the very least, maintained.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In Western society, the prevalence of mental health issues, such as depression and anxiety [ 1 ], as well as recurring psychosomatic health complaints [ 2 ], has increased from the 1980s and 2000s. However, whether these changes in adolescent mental health are actual trends or influenced by alterations in how adolescents perceive, talk about, and report their mental well-being remains ambiguous [ 1 ]. Despite an increase in self-reported mental health problems, levels of mental well-being have remained stable, and severe psychiatric diagnoses have not significantly risen [ 3 , 4 ]. Recent research indicates that understanding how children and youth grasp mental health, its manifestations, and the demarcation between mental health issues and everyday challenges is intricate and diverse. Wickström and Kvist Lindholm [ 5 ] show that problems such as feeling low and nervous are considered deep-seated issues among some adolescents, while others refer to them as everyday challenges. Meanwhile, adolescents in Hellström and Beckman [ 6 ] describe mental health problems as something mainstream, experienced by everyone at some point. Furthermore, Hermann et al. [ 7 ] point out that adolescents can distinguish between positive health and mental health problems. This indicates their understanding of the complexity and holistic nature of mental health and mental health issues. It is plausible that misunderstandings and devaluations of mental health and illness concepts may increase self-reported mental health problems and provide contradictory results when the understanding of mental health is studied. In a previous review on how children and young people perceive the concept of “health,” four major themes have been suggested: health practices, not being sick, feeling good, and being able to do the desired and required activities [ 8 ]. In a study involving 8–11 year olds, children framed both biomedical and holistic perspectives of health [ 9 ]. Regarding the concept of “illness,” themes such as somatic feeling states, functional and affective states [ 10 , 11 ], as well as processes of contagion and contamination, have emerged [ 9 ]. Older age strongly predicts nuances in conceptualizations of health and illness [ 10 , 11 , 12 ].

As the current definitions of mental health and mental illness do not seem to have been successful in guiding how these concepts are perceived, literature has emphasized the importance of understanding individuals’ ideas of health and illness [ 9 , 13 ]. The World Health Organization (WHO) broadly defines mental health as a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and fruitfully and make a contribution to his or her community [ 14 ] capturing only positive aspects. According to The American Psychology Association [ 15 ], mental illness includes several conditions with varying severity and duration, from milder and transient disorders to long-term conditions affecting daily function. The term can thus cover everything from mild anxiety or depression to severe psychiatric conditions that should be treated by healthcare professionals. As a guide for individual experience, such a definition becomes insufficient in distinguishing mental illness from ordinary emotional expressions. According to the Swedish National Board of Health and Welfare et al. [ 16 ], mental health works as an umbrella term for both mental well-being and mental illness : Mental well-being is about being able to handle life's difficulties, feeling satisfied with life, having good social relationships, as well as being able to feel pleasure, desire, and happiness. Mental illness includes both mild to moderate mental health problems and psychiatric conditions . Mild to moderate mental health problems are common and are often reactions to events or situations in life, e.g., worry, feeling low, and sleep difficulties.

It has been argued that increased knowledge of the nature of mental illness can help individuals to cope with the situation and improve their well-being. Increased knowledge about mental illness, how to prevent mental illness and help-seeking behavior has been conceptualized as “mental health literacy” (MHL) [ 17 ], a construct that has emerged from “health literacy” [ 18 ]. Previous literature supports the idea that positive MHL is associated with mental well-being among adolescents [ 19 ]. Conversely, studies point out that low levels of MHL are associated with depression [ 20 ]. Some gender differences have been acknowledged in adolescents, with boys scoring lower than girls on MHL measures [ 20 ] and a social gradient including a positive relationship between MHL and perceived good financial position [ 19 ] or a higher socio-economic status [ 21 ].

While MHL stresses knowledge about signs and treatment of mental illness [ 22 ], the concern from a social constructivist approach would be the conceptualization of mental illness and how it is shaped by society and the thoughts, feelings, and actions of its members [ 23 ]. Studies on the social construction of anxiety and depression through media discourses have shown that language is at the heart of these processes, and that language both constructs the world as people perceive it but also forms the conditions under which an experience is likely to be construed [ 24 , 25 ]. Considering experience as linguistically inflected, the constructionist approach offers an analytical tool to understand the conceptualization of mental illness and to distinguish mental illness from everyday challenges. The essence of mental health is therefore suggested to be psychological constructions identified through how adolescents and society at large perceive, talk about, and report mental health and how that, in turn, feeds a continuous process of conceptual re-construction or adaptation [ 26 ]. Considering experience as linguistically inflected, the constructionist approach could then offer an analytical tool to understand the potential influence of everyday challenges in the conceptualization of mental health.

Research investigating how children and youth perceive and communicate mental health is essential to understand the current rise of reported mental health problems [ 5 ]. Health promotion initiatives are more likely to be successful if they take people’s understanding, beliefs, and concerns into account [ 27 , 28 ]. As far as we know, no review has mapped the literature to explore children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health and mental illness. Based on previous literature, age, gender, and socioeconomic status seem to influence children's and youths’ knowledge and experiences of mental health [ 10 , 11 , 12 ]; therefore, we aim to analyze these perspectives too. From a social constructivist perspective, experience is linguistically inflected [ 26 ]; hence illuminating the conditions under which a perception of health is formed is of interest.

Therefore, we aim to study the literature on how children and youth (ages 10—25) perceive and conceptualize mental health, and the specific research questions are:

What aspects are most salient in children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health?

What concepts do children and youth associate with mental health?

In what way are children's and youth’s perceptions of mental health dependent on gender, age, and socioeconomic factors?

Literature search

A scoping review is a review that aims to provide a snapshot of the research that is published within a specific subject area. The purpose is to offer an overview and, on a more comprehensive level, to distinguish central themes compared to a systematic review. We chose to conduct a scoping review since our aim was to clarify the key concepts of mental health in the literature and to identify specific characteristics and concepts surrounding mental health [ 29 , 30 ]. Our scoping review was conducted following the PRISMA-ScR Checklist [ 31 ]. Two authors (L.B and L.H) searched and screened the eligible articles. In the first step, titles and abstracts were screened. If the study included relevant data, the full article was read to determine if it met the eligibility criteria. Articles were excluded if they did not fulfill all the eligibility criteria. Any uncertainties were discussed among L.B. and L.H., and the third author, S.H., and were carefully assessed before making an inclusion or exclusion decision. The software Picoportal was employed for data management. Figure 1 illustrates a flowchart of data inclusion.

PRISMA flow diagram outlining the search process

Eligibility criteria

We incorporated studies involving children and youth aged 10 to 25 years. This age range was chosen to encompass early puberty through young adulthood, a significant developmental period for young individuals in terms of comprehending mental health. Participants were required not to have undergone interviews due to chronic illness, learning disabilities (e.g., mental health linked to a cancer diagnosis), or immigrant status.

Studies conducted in clinical settings were excluded. For the purpose of comparing results under similar conditions, we specifically opted for studies carried out in Western countries .

Given that this review adopts a moderately constructionist approach, intentionally allowing for the exploration of how both young participants and society in general perceive and discuss mental health and how this process contributes to ongoing conceptual re-construction, the emphasis was placed on identifying articles in which participants themselves defined or attributed meaning to mental health and related concepts like mental illness. The criterion of selecting studies adopting an inductive approach to capture the perspectives of the young participants resulted in the exclusion of numerous studies that more overtly applied established concepts to young respondents [ 32 ].

Information sources

We utilized electronic databases and reached out to study authors if the article was not accessible online. Peer-reviewed articles were exclusively included, thereby excluding conference abstracts due to their perceived lack of relevance in addressing the review questions. Only research in English was taken into account. Publication years across all periods were encompassed in the search.

Search strategy

Studies concerning children’s and youths’ perceptions of mental health were published across a range of scientific journals, such as those within psychiatry, psychology, social work, education, and mental health. Therefore, several databases were taken into account, including Medline, Scopus, CINAHL, PsychInfo, Sociological abstracts, and Google Scholar, spanning from inception on September 20, 2021 to September 30, 2021. We involved a university librarian from the start in the search process. The combinations of search terms are displayed in Table 1 .

Quality assessment

We employed the Quality methods for the development of National Institute for Health Care Excellence (NICE) public health guidance [ 33 ] to evaluate the quality of the studies included. The checklist is based on checklists from Spencer et al. [ 34 ], Public Health Resource Unit (PHRU) [ 26 , 35 ], and the North Thames Research Appraisal Group (NTRAG) [ 36 ] (Refer to S2 for checklist). Eight studies were assigned two plusses, and three studies received one plus. The studies with lower grades generally lacked sufficient descriptions of the researcher’s role, context reporting, and ethical reporting. No study was excluded in this stage.

Data extraction and analysis

We employed a data extraction form that encompassed several key characteristics, including author(s), year, journal, country, details about method/design, participants and socioeconomics, aim, and main results (Table 2 ). The collected data were analyzed and synthesized using the thematic synthesis approach of Thomas and Harden [ 37 ]. This approach encompassed all text categorized as 'results' or 'findings' in study reports – which sometimes included abstracts, although the presentation wasn’t always consistent throughout the text. The size of the study reports ranged from a few sentences to a single page. The synthesis occurred through three interrelated stages that partially overlapped: coding of the findings from primary studies on a line-by-line basis, organization of these 'free codes' into interconnected areas to construct 'descriptive' themes, and the formation of 'analytical' themes.

The objective of this scoping review has been to investigate the literature concerning how children and youth (ages 10—25) conceptualize and perceive mental health. Based on the established inclusion- and exclusion criteria, a total of 11 articles were included representing the United Kingdom ( n = 6), Australia ( n = 3), and Sweden ( n = 2) and were published between 2002 and 2020. Among these, two studies involved university students, while nine incorporated students from compulsory schools.

Salient aspects of children and youth’ perceptions of mental health

Based on the results of the included articles, salient aspects of children’s and youths’ understandings revealed uncertainties about mental health in various ways. This uncertainty emerged as conflicting perceptions, uncertainty about the concept of mental health, and uncertainty regarding where to distinguish between mild to moderate mental health problems and everyday stressors or challenges.

One uncertainty was associated with conflicting perceptions that mental health might be interpreted differently among children and youths, depending on whether it relates to their own mental health or someone else's mental health status. Chisholm et al. [ 42 ] presented this as distinctions being made between ‘them and us’ and between ‘being born with it’. Mental health and mental illness were perceived as a continuum that rather developed’, and distinctions were drawn between ‘crazy’ and ‘diagnosed.’ Participants established strong associations between the term mental illness and derogatory terms like ‘crazy,’ linking extreme symptoms of mental illness with others. However, their attitude was less stigmatizing when it came to individual diagnoses, reflecting a more insightful and empathetic understanding of the adverse impacts of stress based on their personal realities and experiences. Despite the initial reactions reflecting negative stereotypes, further discussion revealed that this did not accurately represent a deeper comprehension of mental health and mental illness.

There was also uncertainty about the concept of mental health , as it was not always clearly understood among the participating youth. Some participants were unable to define mental health, often confusing it with mental illness [ 28 ]. Others simply stated that they did not understand the term, as in O’Reilly [ 44 ]. Additionally, uncertainty was expressed regarding whether mental health was a positive or negative concept [ 27 , 28 , 40 , 44 ], and participants associated mental health with mental illness despite being asked about mental health [ 28 ]. One quote from a grade 9 student illustrates this: “ Interviewer: Can mental health be positive as well? Informant: No, it’s mental” [ 44 ]. In Laidlaw et al. [ 46 ], with participants ranging from 18—22 years of age, most considered mental health distinctly different from and more clinical than mental well-being. However, Roose et al. [ 38 ], for example, the authors discovered a more multifaceted understanding of mental health, encompassing emotions, thoughts, and behavior. In Molenaar et al.[ 45 ], mental health was highlighted as a crucial aspect of health overall. In Chisholm et al. [ 42 ], the older age groups discussed mental health in a more positive sense when they considered themselves or people they knew, relating mental health to emotional well-being. Connected to the uncertainty in defining the concept of mental health was the uncertainty in identifying those with good or poor mental health. Due to the lack of visible proof, children and youths might doubt their peers’ reports of mental illness, wondering if they were pretending or exaggerating their symptoms [ 27 ].

A final uncertainty that emerged was difficulties in drawing the line between psychiatric conditions and mild to moderate mental health problems and everyday stressors or challenges . Perre et al. [ 43 ] described how the participants in their study were uncertain about the meaning of mental illness and mental health issues. While some linked depression to psychosis, others related it to simply ‘feeling down.’ However, most participants indicated that, in contrast to transient feelings of sadness, depression is a recurring concern. Furthermore, the duration of feeling depressed and particularly a loss of interest in socializing was seen as appropriate criteria for distinguishing between ‘feeling down’ and ‘clinical depression.’ Since feelings of anxiety, nervousness, and apprehension are common experiences among children and youth, defining anxiety as an illness as opposed to an everyday stressor was more challenging [ 43 ].

Terms used to conceptualize mental health

When children and youth were asked about mental health, they sometimes used neutral terms such as thoughts and emotions or a general ‘vibe’ [ 27 ], and some described it as ‘peace of mind’ and being able to balance your emotions [ 38 ]. The notion of mental health was also found to be closely linked with rationality and the idea of normality, although, according to the young people, Armstrong et al. [ 28 ], there was no consensus about what ‘normal’ meant. Positive aspects of mental health were described by the participants as good self-esteem, confidence [ 40 ], happiness [ 39 , 43 ], optimism, resilience, extraversion and intelligence [ 27 ], energy [ 43 ], balance, harmony [ 39 , 43 ], good brain, emotional and physical functioning and development, and a clear idea of who they are [ 27 , 41 ]. It also included a feeling of being a good person, feeling liked and loved by your parents, social support, and having people to talk with [ 27 , 39 ], as well as being able to fit in with the world socially and positive peer relationships [ 41 ], according to the children and youths, mental health includes aspects related to individuals (individual factors) as well as to people in their surroundings (relationships). Regarding mental illness, participants defined it as stress and humiliation [ 40 ], psychological distress, traumatic experiences, mental disorders, pessimism, and learning disabilities [ 27 ]. Also, in contrast to the normality concept describing mental health, mental illness was described as somehow ‘not normal’ or ‘different’ in Chisholm et al. [ 42 ].

Depression and bipolar disorder were the most often mentioned mental illnesses [ 27 ]. The inability to balance emotions was seen as negative for mental health, for example, not being able to set aside unhappiness, lying to cover up sadness, and being unable to concentrate on schoolwork [ 38 ]. The understanding of mental illness also included feelings of fear and anxiety [ 42 ]. Other participants [ 46 ] indicated that mental health is distinctly different from, and more clinical than, mental well-being. In that sense, mental health was described using reinforcing terms such as ‘serious’ and ‘clinical,’ being more closely connected to mental illness, whereas mental well-being was described as the absence of illness, feeling happy, confident, being able to function and cope with life’s demands and feeling secure. Among younger participants, a more varied and vague understanding of mental health was shown, framing it as things happening in the brain or in terms of specific conditions like schizophrenia [ 44 ].

Gender, age, socioeconomic status

Only one study had a gender theoretical perspective [ 40 ], but the focus of this perspective concerned gender differences in what influences mental health more than the conceptualization of mental health. According to Johansson et al.[ 39 ], older girls expressed deeper negative emotions (e.g., described feelings of lack of meaning and hope in various ways) than older boys and younger children.

Several of the included studies noticed differences in age, where younger participants had difficulty understanding the concept of mental health [ 39 , 44 ], while older participants used more words to explain it [ 39 ]. Furthermore, older participants seemed to view mental health and mental illness as a continuum, with mental illness at one end of the continuum and mental well-being at the other end [ 42 , 46 ].

Socioeconomic status

The role of socioeconomic status was only discussed by Armstrong et al. [ 28 ], finding that young people from schools in the most deprived and rural areas experienced more difficulties defining the term mental health compared to those from a less deprived area.

This scoping review aimed to map children's and youth’s perceptions and conceptualizations of mental health. Our main findings indicate that the concept of mental health is surrounded by uncertainty. This raises the question of where this uncertainty stems from and what it symbolizes. From our perspective, this uncertainty can be understood from two angles. Firstly, the young participants in the different studies show no clear and common understanding of mental health; they express uncertainty about the meaning of the concept and where to draw the line between life experiences and psychiatric conditions. Secondly, uncertainty exists regarding how to apply these concepts in research, making it challenging to interpret and compare research results. The shift from a positivistic understanding of mental health as an objective condition to a more subjective inner experience has left the conceptualization open ranging from a pathological phenomenon to a normal and common human experience [ 47 ]. A dilemma that results in a lack of reliability that mirrors the elusive nature of the concept of mental health from both a respondent and a scientific perspective.

“Happy” was commonly used to describe mental health, whereas "unhappy" was used to describe mental illness. The meaning of happiness for mental health has been acknowledged in the literature, and according to Layard et al. [ 48 ], mental illness is one of the main causes of unhappiness, and happiness is the ultimate goal in human life. Layard et al. [ 48 ] suggest that schools and workplaces need to raise more awareness of mental health and strive to improve happiness to promote mental health and prevent mental illness. On the other hand, being able to experience and express different emotions could also be considered a part of mental health. The notion of normality also surfaced in some studies [ 38 ], understanding mental health as being emotionally balanced or normal or that mental illness was not normal [ 42 ]. To consider mental illness in terms of social norms and behavior followed with the sociological alternative to the medical model that was introduced in the sixties portraying mental illness more as socially unacceptable behavior that is successfully labeled by others as being deviant. Although our results did not indicate any perceptions of what ‘normal’ meant [ 28 ], one crucial starting point to the understanding of mental health among adolescents should be to delineate what constitutes normal functioning [ 23 ]. Children and youths’ understanding of mental illness seems to a large extent, to be on the same continuum as a normality rather than representing a medicalization of deviant behavior and a disjuncture with normality [ 49 ].

Concerning gender, it seemed that girls had an easier time conceptualizing mental health than boys. This could be due to the fact that girls mature verbally faster than boys [ 50 ], but also that girls, to a larger extent, share feelings and problems together compared to boys [ 51 ]. However, according to Johansson et al. [ 39 ], the differences in conceptualizations of mental health seem to be more age-related than gender-related. This could be due to the fact that older children have a more complex view of mental health compared to younger children.. Not surprisingly, the older the children and youth were, the more complex the ability to conceptualize mental health becomes. Only one study reported socioeconomic differences in conceptualizations of mental health [ 28 ]. This could be linked to mental health literacy (MHL) [ 18 ], i.e., knowledge about mental illness, how to prevent mental illness, and help-seeking behavior. Research has shown that disadvantaged social and socioeconomic conditions are associated with low MHL, that is, people with low SES tends to know less about symptoms and prevalence of different mental health problems [ 19 , 21 ]. The perception and conceptualizations of mental health are, as we consider, strongly related to knowledge and beliefs about mental health, and according to von dem Knesebeck et al. [ 52 ] linked primarily to SES through level of education.

Chisholm et al. [ 42 ] found that the initial reactions from participants related to negative stereotypes, but further discussion revealed that the participants had more refined knowledge than at first glance. This illuminates the importance of talking to children and helping them verbalize their feelings, in many respects complex and diversified understanding of mental health. It is plausible that misunderstandings and devaluations of mental health and mental illness may increase self-reported mental health problems [ 5 ], as well as decrease them, preventing children and youth from seeking help. Therefore, increased knowledge of the nature of mental health can help individual cope with the situations and improve their mental well-being. Finding ways to incorporate discussions about mental well-being, mental health, and mental illness in schools could be the first step to decreasing the existing uncertainties about mental health. Experiencing feelings of sadness, anger, or upset from time to time is a natural part of life, and these emotions are not harmful and do not necessarily indicate mental illness [ 5 , 6 ]. Adolescents may have an understanding of the complexity of mental health despite using simplified language but may need guidance on how to communicate their feelings and how to manage everyday challenges and normal strains in life [ 7 ].

With the aim of gaining a better understanding of how mental health is perceived among children and youth, this study has highlighted the concept’s uncertainty. Children and youth reveal a variety of understandings, from diagnoses of serious mental illnesses such as schizophrenia to moods and different types of behaviors. Is there only one way of understanding mental health, and is it reasonable to believe that we can reach a consensus? Judging by the questions asked, researchers also seem to have different ideas on what to incorporate into the concept of mental health — the researchers behind the present study included. The difficulties in differentiating challenges being part of everyday life with mental health issues need to be paid closer attention to and seems to be symptomatic with the lack of clarity of the concepts.

A constructivist approach would argue that the language of mental health has changed over time and thus influence how adolescents, as well as society at large, perceive, talk about, and report their mental health [ 26 ]. The re-construction or adaptation of concepts could explain why children and youth re struggling with the meaning of mental health and that mental health often is used interchangeably with mental illness. Mental health, rather than being an umbrella term, then represents a continuum with a positive and a negative end, at least among older adolescents. But as mental health according to this review also incorporates subjective expressions of moods and feelings, the reconstruction seems to have shaped it into a multidimensional concept, representing a horizontal continuum of positive and negative mental health and a vertical continuum of positive and negative well-being, similar to the health cross by Tudor [ 53 ] referred to in Laidlaw et al. [ 46 ] A multidimensional understanding of mental health constructs also incorporates evidence from interventions aimed at reducing mental health stigma among adolescents, where attitudes and beliefs as well as emotional responses towards mental health are targeted [ 54 ].