Using Concept Mapping Activities to Enhance Students’ Critical Thinking Skills at a High School in Taiwan

- Regular Article

- Published: 15 July 2019

- Volume 29 , pages 249–256, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Sheng-Shiang Tseng ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9635-0130 1

1455 Accesses

18 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Concept mapping activities have been used to enhance critical thinking skills as an essential competency for 21st century learners. However, little information has been provided about the relationship between different concept mapping activities and critical thinking skills. This study aimed to examine the effects of the fill-in-the-map activity and the construct-the-map activity on critical thinking skill development. 43 participants were recruited from the course, research seminar, in the department of English at a high school in Taiwan. There were two sections of the course in the same semester. Class A was randomly designated as the fill-in-the-map group and Class B as the construct-the-map group. The collected data included critical thinking survey scores, and interviews. The critical thinking survey scores collected from the two groups were analyzed using a multivariate analysis of variance to examine the difference in critical thinking skill development between the two groups. The multivariate results suggested that different concept mapping activities would produce different learning outcomes. The construct-the-map group significantly obtained higher scores than the fill-in-the-map concept mapping group in the critical thinking skills: inference, interpretation, analysis, evaluation, explanation. The interviews were analyzed to account for why the construct-the-map activity was more effective than the fill-in-the-map activity in developing students' inference, interpretation, analysis, evaluation, explanation skills. Suggestions and implications are proposed to develop critical thinking skills through concept mapping activities.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Select-and-Fill-In Concept Maps as an Evaluation Tool in Science Classrooms

Investigating Through Concept Mapping Pre-service Teachers’ Thinking Progression About “e-Learning” and Its Integration into Teaching

Enhancing the Quality of Concept Mapping Interventions in Undergraduate Science

Data availability.

The data of this data are not open to the public due to participant privacy reasons.

Afamasaga-Fuata'i, K. (2008). Students' conceptual understanding and critical thinking: A case for concept maps and vee-diagrams in mathematics problem solving. Australian Mathematics Teacher, 64 (2), 8–17.

Google Scholar

Anohina-Naumeca, A. (2014). Finding factors influencing students’ preferences to concept mapping tasks: Literature review. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 128 , 105–110.

Article Google Scholar

Ausubel, D. (1968). Educational psychology: A cognitive view . New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Baugh, N. G., & Mellott, K. G. (1998). Clinical concept mapping as preparation for student nurses' clinical experiences. Journal of Nursing Education, 37 (6), 253–256.

Bixler, G. M., Brown, A., Way, D., Ledford, C., & Mahan, J. D. (2015). Collaborative concept mapping and critical thinking in fourth-year medical students. Clinical Pediatrics, 54 (9), 833–839.

Bray, J. H., & Maxwell, S. E. (1985). Multivariate analysis of variance . Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Chang, K. E., Sung, Y. T., & Chen, S. F. (2001). Learning through computer-based concept mapping with scaffolding aid. Journal of Computer-Assisted Learning, 17 (1), 21–33.

Daley, B. J., Shaw, C. R., Balistrieri, T., Glasenapp, I., & Placentine, L. (1999). Concept maps: A strategy to teach and evaluate critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 38 , 42–47.

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction . Research findings and recommendations. ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED315423.f

Harris, C., & Zha, S. (2013). Concept mapping: A critical thinking technique. Education, 134 (2), 207–211.

Himangshu, S., & Cassata-Widera, A. (2010). Beyond individual classrooms: How valid are concept maps for large scale assessment? Concept maps: Making learning meaningful. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Concept Mapping , pp. 58–65.

Huang, Y. C., Chen, H. H., Yeh, M. L., & Chung, Y. C. (2012). Case studies combined with or without concept maps improve critical thinking in hospital-based nurses: A randomized-controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49 (6), 747–754.

Jie, Z., Yuhong, J., & Yuang, Y. (2015). The investigation on critical thinking ability in EFL reading class. English Language Teaching, 8 (1), 83–94.

Ko (2014). The effect of the integration of critical thinking into English teaching on senior high school. Unpublished master’s thesis, National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan, ROC

Lee, W., Chiang, C. H., Liao, I. C., Lee, M. L., Chen, S. L., & Liang, T. (2013). The longitudinal effect of concept map teaching on critical thinking of nursing students. Nurse education today , 33 (10), 1219–1223.

Lee, Y., & Nelson, D. W. (2005). Viewing or visualising—which concept map strategy works best on problem-solving performance? British Journal of Educational Technology , 36 (2), 193–203.

Maneval, R. E., Filburn, M. J., Deringer, S. O., & Lum, G. D. (2011). Concept mapping: Does it improve critical thinking ability in practical nursing students? Nursing Education Perspectives, 32 (4), 229–233.

McMullen, M. A., & MuMullen, W. F. (2009). Examining patterns of change in the critical thinking skills of graduate nursing students. Journal of Nursing Education, 48 (6), 310–318.

MOE. (2002). Principles of nine-year integrated curriculum designs . Taipei: Ministry of Education.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Paulus, T., Lester, J., & Dempster, P. (2014). Digital tools for qualitative research . London, UK: Sage Publications.

Rosen, Y., & Tager, M. (2014). Making student thinking visible through a concept map in computer-based assessment of critical thinking. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 50 (2), 249–270.

Rotherham, A. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2010). “21st-Century” Skills. American Educator , pp. 17–20.

Ruiz-Primo, M. A. (2004). Examining concept maps as an assessment tool. Concept Maps: Theory, Methodology, Technology. Paper presented at the Proceedings of the First International Conference on Concept Mapping, Pamplona, Spain.

Ruiz-Primo, M. A., & Shavelson, R. J. (1996). Problems and issues in the use of concept maps in science assessment. Journal of Research in Science Teaching , 33 (6), 569–600.

Wheeler, L. A., & Collins, S. K. (2003). The influence of concept mapping on critical thinking in baccalaureate nursing students. Journal of professional nursing , 19 (6), 339–346.

Yang, S. C., & Lin, W. C. (2004). The relationship among creative. critical thinking and thinking styles in Taiwan high school students. Journal of Instructional Psychology , 31 (1), 33–45.

Yang, Y. T. C., & Wu, W. C. I. (2012). Digital storytelling for enhancing student academic achievement, critical thinking, and learning motivation: A year-long experimental study. Computers & Education, 59 (2), 339–352.

Yeh, A. (2002). Analysis of high-order thinking abilities and instructional design. Journal of General Education, 1 , 75–101.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Graduate Institute of Curriculum and Instruction, Tamkang University, New Taipei City, Taiwan

Sheng-Shiang Tseng

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sheng-Shiang Tseng .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

There is no conflict of interest in the study undertaken and the reporting of its findings.

Ethical Approval

IRB approval was obtained by the University of Georgia and informed consent procedures were followed.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Tseng, SS. Using Concept Mapping Activities to Enhance Students’ Critical Thinking Skills at a High School in Taiwan. Asia-Pacific Edu Res 29 , 249–256 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00474-0

Download citation

Published : 15 July 2019

Issue Date : June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-019-00474-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Critical thinking

- Concept mapping

- High school students

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Primed To Learn

Embark on Your Learning Journey

Concept Mapping: 13 Benefits of a Visual Roadmap to Learning Success

Concept Mapping is a creative and effective tool that can transform the way we absorb and retain information. Born from the field of cognitive science, concept mapping serves as a visual representation of understanding and ideas. It has the potential to solidify learning by breaking complex topics into manageable, interconnected chunks. So whether you’re a student, an educator, or a lifelong learner, join us as we delve deeper into the world of Concept Mapping and explore its impact on learning and retention.

Effective learning strategies are crucial for enhancing comprehension, retention, and application of knowledge. They foster deep understanding, promote critical thinking, and facilitate the transfer of learning to new contexts. One powerful learning tool that exemplifies these benefits is concept mapping.

Benefits of Using Concept Maps in Learning

Concept maps are powerful tools that offer several benefits when used in the context of learning. Here are some of the key advantages:

1. Enhanced Understanding

Concept maps help learners organize and structure information in a visual format. This process aids in clarifying relationships between concepts and allows for a deeper understanding of complex topics.

2. Improved Memory Retention

By engaging both visual and textual aspects of learning, concept maps enhance memory retention. When learners create concept maps, they actively process information, making it more likely to be stored in long-term memory.

3. Effective Summarization

Concept maps can serve as concise summaries of large volumes of information. They allow learners to distill the most important concepts and connections, making it easier to review and recall key details.

4. Facilitates Critical Thinking

Creating concept maps encourages critical thinking as learners must analyze, synthesize, and evaluate the relationships between concepts. This promotes a deeper level of engagement with the material.

5. Enhances Problem Solving

Concept maps help learners see the bigger picture and identify potential solutions to problems. They promote a holistic understanding of topics, making it easier to apply knowledge to real-world scenarios.

6. Organized Study Tool

Concept maps act as organized study guides. They provide a structured overview of a subject, making it easier to plan study sessions and track progress.

7. Customized Learning

Concept maps are versatile and can be tailored to individual learning preferences. Learners can adapt the structure and content of their concept maps to suit their specific needs.

8. Effective Communication

Concept maps are not only a personal learning tool but also a means of effective communication. They can be used to convey complex ideas to others, making them valuable in group projects or presentations.

9. Cross-Disciplinary Learning

Concept maps can be applied to various subjects and disciplines. They promote interdisciplinary connections, helping learners relate ideas from different areas of knowledge.

10. Assessment Preparation

Concept maps can be used as a study aid when preparing for exams or assessments. They serve as a visual summary of the material, making it easier to review and test one’s knowledge.

11. Enhanced Creativity

Creating concept maps allows for a degree of creativity in representing ideas and connections. This can make the learning process more engaging and enjoyable.

12. Long-Term Learning

Because concept maps promote a deeper understanding of concepts, the knowledge acquired through this method is more likely to be retained over the long term, compared to rote memorization.

13. Increased Engagement

Concept mapping is an active learning technique that keeps learners engaged in the material. It encourages exploration and discovery, fostering a sense of curiosity and interest in the subject matter.

Concept maps are versatile learning tools that offer numerous benefits, including improved understanding, memory retention, critical thinking, and problem-solving skills. They can be customized to suit individual learning styles and are effective aids for both studying and communicating complex ideas. Incorporating concept mapping into your learning strategy can enhance your overall learning experience and academic performance.

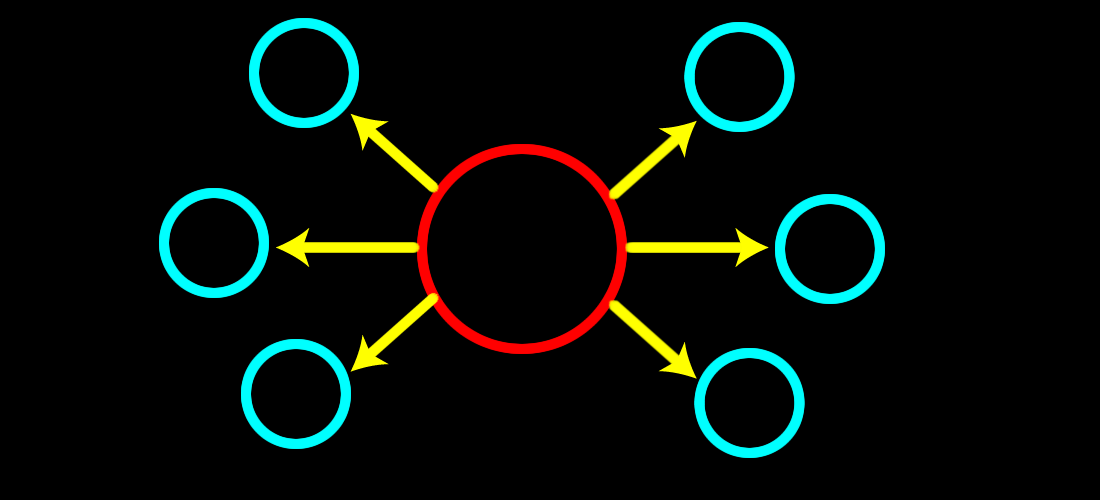

Understanding Concept Mapping

Concept mapping is a visual representation of information that helps learners understand and remember complex ideas. By displaying the relationships between concepts, it enables learners to structure their thoughts, identify connections, and grasp the big picture, thus promoting a more profound and lasting understanding.

Concept mapping, a visual tool for representing knowledge, has its roots in the cognitive theories of education proposed by American psychologist and educational researcher David Ausubel in the 1960s. Ausubel emphasized the importance of prior knowledge in learning new concepts. In the mid-1970s, his student Joseph D. Novak developed the concept mapping technique based on Ausubel’s learning theory.

Novak’s approach was designed to represent an individual’s cognitive structure, enabling learners to understand and integrate new information in relation to what they already know. Over the years, the use of concept maps has expanded beyond education, serving as a tool for knowledge representation and organization in a range of fields including business, healthcare, and software development.

How to Create a Concept Map

Creating a concept map is a systematic process that helps you visualize the relationships between concepts and ideas. Here’s a step-by-step guide to creating a concept map:

1: Identify Your Central Concept or Topic

Begin by determining the central concept or topic that you want to explore or understand. This concept will be placed at the center of your concept map.

2: List Key Concepts and Subconcepts

Identify the key concepts related to your central concept. These are the main ideas or categories that will branch out from the central concept.

Beneath each key concept, list sub-concepts or details that are related to each key concept. These sub-concepts should be connected to their respective key concepts.

3: Create Connections

Draw lines or arrows to connect the key concepts to the central concept. These lines represent the relationships or connections between the central concept and its key concepts.

Connect sub-concepts to their respective key concepts using lines or arrows as well.

4: Label Each Concept

Write labels or keywords for each concept and sub-concept. These labels should be concise and clear, helping you understand the content of each concept at a glance.

5: Use Visual Elements

Enhance your concept map with visual elements such as colors, shapes, and icons. These elements can help differentiate concepts, emphasize relationships, and make the map more visually appealing.

6: Organize and Arrange

Arrange the concepts and sub-concepts in a logical and organized manner. Typically, key concepts are placed closer to the central concept, and sub-concepts are positioned beneath their respective key concepts.

Use hierarchy and spatial organization to indicate the importance and relationships between concepts.

7: Review and Refine

Step back and review your concept map. Check for clarity, accuracy, and completeness. Ensure that the connections and relationships make sense.

Make any necessary revisions or refinements to improve the overall structure and readability of your concept map.

8: Add Details

If needed, you can add additional details, examples, or explanations to the concept map. These details can provide a deeper understanding of each concept.

9: Share or Use Your Concept Map

Your concept map can be used as a study tool, a teaching aid, or a visual representation of your knowledge. Share it with others to communicate complex ideas or use it to study and reinforce your understanding of the topic.

10: Update as Needed

Concept maps are dynamic tools. As your understanding of the topic evolves or as you gather more information, feel free to update and expand your concept map to reflect your growing knowledge.

Creating concept maps can be a valuable part of the learning process, helping you organize information, clarify relationships between concepts, and deepen your understanding of complex topics. Remember that there’s no single “right” way to create a concept map, and your map can be tailored to your specific needs and preferences.

Educational Technology: 12 Transformative Ways to Teach and Learn in the Digital Age

Tools and Software for Creating Concept Maps

There are several tools and software applications available for creating concept maps, ranging from simple and free options to more advanced and feature-rich ones. Here is a list of some popular tools and software for creating concept maps, along with a brief discussion of each:

Coggle is a web-based tool that offers a user-friendly interface for creating concept maps. It allows for collaboration in real-time, making it ideal for group projects and brainstorming sessions. Coggle offers both free and paid plans.

2. Lucidspark

Lucidspark, by Lucid, is a virtual whiteboard tool that can be used for creating concept maps, mind maps, and collaborative diagrams. It offers a range of interactive features and is suitable for remote or online collaboration.

3. MindMeister

MindMeister is an online mind mapping tool that enables users to create concept maps, share them with others, and collaborate in real-time. It offers various templates and integrations with other productivity tools.

XMind is a versatile and feature-rich mind mapping software available for Windows, macOS, and Linux. It provides a wide range of customization options, including various themes and layouts. XMind offers both free and paid versions.

5, ConceptDraw MINDMAP

ConceptDraw MINDMAP is a professional mind mapping and concept mapping software for Windows and macOS. It is known for its advanced diagramming capabilities and is suitable for complex projects and presentations.

6. Bubbl.us

Bubbl.us is a straightforward and web-based tool for creating simple concept maps and mind maps. It is intuitive and doesn’t require any software installation. Bubbl.us offers a free version as well.

Scapple, by the creators of Scrivener, is a minimalistic and cross-platform brainstorming tool. While not as feature-rich as some other options, it’s excellent for quickly jotting down ideas and concepts.

8. Edraw MindMaster

Edraw MindMaster is a professional mind mapping and concept mapping software that offers various templates, styles, and export options. It’s suitable for both educational and business use.

9. Microsoft Visio

Microsoft Visio is a diagramming and vector graphics application that can be used for creating concept maps, flowcharts, and other visual representations. It is part of the Microsoft Office suite.

10. Pen and Paper

Sometimes, the simplest tools are the most effective. Many people prefer to create concept maps using pen and paper, allowing for complete flexibility and creativity without the constraints of software.

When choosing a concept mapping tool or software, consider factors such as your specific needs, platform compatibility, collaboration requirements, and your budget. Many of these tools offer free trial versions, so you can experiment with a few options before settling on the one that best suits your purposes.

Ways to Integrate Concept Mapping into Your Learning Routine

Integrating concept mapping into your learning routine can be a highly effective way to enhance your understanding and retention of information. Here are several ways you can incorporate concept mapping into your learning process:

1. Note-Taking

Use concept maps as an alternative or complementary method to traditional linear note-taking. When listening to lectures or reading textbooks, create concept maps to visually represent key ideas and their relationships. This approach can make your notes more organized and easier to review later.

2. Study Guides

Before major exams or assignments, create concept maps that summarize the main topics and concepts you need to cover. This serves as a visual study guide that provides a structured overview of the material.

3. Brainstorming and Idea Generation

Use concept maps as a tool for brainstorming and generating ideas for essays, research papers, or creative projects. Start with a central concept and branch out with related ideas, arguments, or themes.

4. Project Planning

When working on projects or research, create concept maps to outline the project’s scope, objectives, and key milestones. This can help you stay organized and ensure that all components are properly considered.

5. Problem Solving

Concept maps can aid in problem-solving by helping you break down complex issues into smaller, more manageable components. Identify the main problem in the center and branch out with potential causes, solutions, and outcomes.

6. Group Work and Collaboration

Collaborative concept mapping is a valuable tool for group projects. Work with peers to create concept maps that synthesize collective knowledge and ideas. It can help ensure that everyone is on the same page and promote a deeper understanding of the project.

7. Visual Summaries

After completing a chapter or unit of study, create a concept map that serves as a visual summary. This will allow you to review the material in a more structured and efficient manner.

8. Review and Self-Assessment

Regularly revisit your concept maps as part of your study routine. Use them to test your knowledge by covering sections of the map and trying to recall the related concepts and connections. This active recall can enhance your long-term retention.

9. Problem-Based Learning

For subjects that involve problem-solving, create concept maps that represent different scenarios or case studies. Use these maps to analyze and evaluate possible solutions or outcomes.

10. Interdisciplinary Connections

Explore connections between concepts from different subjects or disciplines by creating cross-disciplinary concept maps. This can help you gain a broader perspective on complex topics.

11. Digital Tools and Software

Take advantage of digital concept mapping tools and software, which often offer collaboration features, templates, and the ability to easily edit and share your maps.

12. Experiment with Different Styles

Don’t be afraid to experiment with different concept mapping styles, such as hierarchical, radial, or flowchart-based maps. Choose the style that best fits the nature of the content and your personal preferences.

Concept mapping is a flexible technique that can be adapted to various learning situations. The key is to make it an integral part of your learning routine, allowing it to enhance your comprehension, organization, and retention of information across different subjects and contexts.

Real-Life Examples

Practical examples of concept maps for various subjects.

Concept maps can be applied to a wide range of subjects and topics to help organize and clarify complex information. Here are some practical examples of concept maps for various subjects:

Biology: The Nitrogen Cycle

- Central Concept : Nitrogen Cycle

- Key Concepts : Nitrogen fixation, Nitrification, Assimilation, Denitrification

- Sub-Concepts : Atmospheric nitrogen, Ammonia, Nitrites, Nitrates, Plants, Decomposers, Bacteria

- Relationships : Arrows indicating the flow of nitrogen through the cycle

History: Causes of World War I

- Central Concept : World War I

- Key Concepts : Militarism, Alliances, Imperialism, Nationalism

- Sub-Concepts : Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Triple Entente, Triple Alliance

- Relationships : Arrows connecting key concepts to the outbreak of the war

Literature: Themes in “To Kill a Mockingbird”

- Central Concept : “To Kill a Mockingbird” Themes

- Key Concepts : Racism, Moral Conscience, Innocence

- Sub-Concepts : Atticus Finch, Boo Radley, Tom Robinson, Scout Finch

- Relationships : Arrows indicating how characters and events in the book relate to the central themes

Physics: Laws of Thermodynamics

- Central Concept : Laws of Thermodynamics

- Key Concepts : First Law (Conservation of Energy), Second Law (Entropy), Third Law (Absolute Zero)

- Sub-Concepts : Heat, Work, Efficiency, Temperature Scales

- Relationships : Arrows showing how energy, heat, and work are related according to the laws

Psychology: Theories of Motivation

- Central Concept : Motivation

- Key Concepts : Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, Self-Determination Theory, Drive-Reduction Theory

- Sub-Concepts : Physiological needs, Psychological needs, Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic motivation

- Relationships : Arrows illustrating how each theory relates to different aspects of motivation

Geography: Factors Affecting Climate

- Central Concept : Climate

- Key Concepts : Latitude, Altitude, Ocean Currents, Wind Patterns

- Sub-Concepts : Tropical, Temperate, Polar Climate Zones

- Relationships : Arrows connecting factors like latitude and altitude to specific climate zones

Mathematics: Pythagorean Theorem

- Central Concept : Pythagorean Theorem

- Key Concepts : Right Triangle, Hypotenuse, Legs, Triangular Inequality

- Sub-Concepts : Formula, Proof, Applications

- Relationships : Diagram illustrating the theorem and its components

Economics: Circular Flow of Income

- Central Concept : Circular Flow of Income

- Key Concepts : Households, Firms, Government, Financial Markets

- Sub-Concepts : Income, Expenditure, Savings, Investment

- Relationships : Arrows depicting the flow of money and resources among the different sectors

Chemistry: Periodic Table

- Central Concept : Periodic Table

- Key Concepts : Elements, Atomic Number, Atomic Mass, Periods, Groups

- Sub-Concepts : Metals, Nonmetals, Noble Gases, Transition Metals

- Relationships : Arrangement of elements in the table based on atomic number and properties

Art: Elements of Design

- Central Concept : Elements of Design

- Key Concepts : Line, Shape, Color, Texture, Space

- Sub-Concepts : Primary Colors, Complementary Colors, Geometric Shapes, Organic Shapes

- Relationships : Arrows indicating how elements can be combined in artworks

These examples demonstrate how concept maps can be used to visually represent and organize information in various academic disciplines, helping learners to better understand and retain complex subject matter.

How Professionals Use Concept Mapping in Their Fields

Professionals across various fields utilize concept mapping as a valuable tool for organizing ideas, solving problems, and communicating complex information. Here are some ways professionals use concept mapping in their respective fields:

- Teachers : Educators use concept maps to design curriculum, plan lessons, and illustrate relationships between topics for students. They also use concept mapping as a teaching tool to help students visualize and understand complex subjects.

- Students : Students employ concept mapping to take structured notes, create study guides, and summarize course materials. Concept maps are particularly useful for preparing for exams and writing research papers.

Business and Management

- Project Managers : Concept maps aid in project planning by visualizing project scope, objectives, tasks, and dependencies. They help project managers allocate resources efficiently and track progress.

- Marketing Professionals : Marketers use concept mapping to develop marketing strategies, brainstorm campaign ideas, and identify target audiences. Concept maps can clarify the steps in a marketing plan.

- Business Analysts : Concept mapping helps business analysts understand complex business processes, map workflows, and identify areas for improvement. It is useful for requirements gathering and system design.

- Doctors and Clinicians : Healthcare professionals create concept maps to outline patient diagnoses, treatment plans, and medical histories. Concept mapping can aid in clinical decision-making and patient communication.

- Nurses : Nurses use concept maps for care planning, tracking patient progress, and organizing patient information. They help ensure coordinated and effective patient care.

Research and Academia

- Scientists : Researchers use concept maps to organize research hypotheses, experimental designs, and data analysis plans. They help scientists identify gaps in their research and plan future experiments.

- Academics : Academics employ concept mapping to visualize complex theories, outline research papers, and structure lectures. Concept maps enhance the clarity of academic presentations.

Information Technology (IT)

- Systems Analysts : IT professionals use concept maps to model system architectures, map data flows, and document software requirements. Concept mapping aids in understanding complex IT systems.

- Network Administrators : Network administrators create concept maps to visualize network topologies, troubleshoot issues, and plan network upgrades. They help maintain network efficiency and security.

Environmental Science

- Environmentalists : Concept maps assist environmental scientists in analyzing ecosystems, documenting species interactions, and planning conservation efforts. They help professionals identify environmental challenges and solutions.

Legal Profession

- Lawyers : Lawyers use concept maps to outline legal cases, strategies, and arguments. They help lawyers visualize the structure of their cases and ensure all legal elements are considered.

- Legal Researchers : Legal researchers employ concept maps to organize legal precedents, statutes, and case law. Concept mapping aids in legal analysis and the preparation of legal briefs.

Architecture and Engineering

- Architects : Architects use concept maps to conceptualize building designs, site plans, and interior layouts. Concept mapping helps translate ideas into tangible plans.

- Engineers : Engineers create concept maps to model complex systems, map out engineering processes, and troubleshoot issues. Concept maps aid in designing efficient engineering solutions.

Concept mapping is a versatile tool that professionals can adapt to their specific needs in various fields, enabling them to better organize, analyze, and communicate complex information and ideas.

Concept mapping stands as a powerful tool in the learning process, weaving a network of understanding that connects new knowledge with existing information. It fosters a deep and thorough comprehension of concepts and their interrelationships, enabling learners to navigate complex subjects with confidence. The visualization of knowledge structures through concept mapping not only enhances recall but also facilitates critical thinking and creativity. Whether you’re an educator aiming to illuminate a topic or a student endeavoring to grasp intricate material, concept mapping can prove to be an invaluable ally in your learning journey.

You might also like:

- Spaced Repetition Unleashed: 11 Benefits to Unlock Your Brain’s Potential

- Dual Coding: 8 Benefits of Visual and Verbal Learning

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res

- v.19(1); Jan-Feb 2014

Clinical concept mapping: Does it improve discipline-based critical thinking of nursing students?

Marzieh moattari.

1 School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran

Sara Soleimani

Neda jamali moghaddam, farkhondeh mehbodi, background:.

Enhancing nursing students’ critical thinking is a challenge faced by nurse educators. This study aimed at determining the effect of clinical concept mapping on discipline-based critical thinking of nursing students.

Materials and Methods:

In this quasi-experimental post-test only design, a convenient sample of 4 th year nursing students ( N = 32) participated. They were randomly divided into two groups. The experimental group participated in a 1-day workshop on clinical concept mapping. They were also assigned to use at least two clinical concepts mapping during their clinical practice. Post-test was done using a specially designed package consisting of vignettes for measurement of 17 dimensions of critical thinking in nursing under two categories of cognitive critical thinking skills and habits of mind. They were required to write about how they would use a designated critical thinking skills or habits of mind to accomplish the nursing actions. The students’ responses were evaluated based on identification of critical thinking, justification, and quality of the student's response. The mean score of both groups was compared by Mann-Whitney test using SPSS version 16.5.

The results of the study revealed a significant difference between the two groups’ critical thinking regarding identification, justification, and quality of responses, and overall critical thinking scores, cognitive thinking skills, and habits of mind. The two groups also differed significantly from each other in 11 out of 17 dimensions of critical thinking.

Conclusion:

Clinical concept mapping is a valuable strategy for improvement of critical thinking of nursing students. However, further studies are recommended to generalize this result to nursing students in their earlier stage of education.

I NTRODUCTION

Contemporary explosive nature of today's knowledge has created a situation in which our nursing students’ achievement in meeting their learning needs is quite difficult.[ 1 ] Therefore, the importance of critical thinking has been increasingly emphasized in the last decades and nursing educators are challenged to determine appropriate methods of teaching and evaluating critical thinking among nursing students.[ 2 ]

Critical thinking has been defined by many philosophers in different ways indicating the multifaceted nature of critical thinking as a process or outcome. However, consideration of the context has been highlighted in John Dewey's definition of critical thinking. According to Dewey, critical thinking is active, persistent, and careful consideration of a belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds which support it and the further conclusions to which it tends (Dewey, 1909, page 9).[ 3 ] Also, context is highlighted in a definition provided by Facion.[ 4 ] Therefore, it should be considered that definition of critical thinking in different academic disciplines may vary as each discipline has its own specific knowledge. In an attempt to describe critical thinking in nursing, many models have been developed.[ 5 , 6 ]

To define critical thinking in the context of nursing, Schefer and Rubenfeld (2000) conducted a five-round Delphi study in which 55 nurse educators were involved. Based on their study, a consensus was made on 17 dimensions of critical thinking under two categories of thinking (cognitive) skills and habits of mind[ 7 ] [Box 1].

Different strategies have been developed to teach critical thinking. Concept mapping is one example proposed for improvement of critical thinking. Using this strategy, the students draw the map of contents, and therefore use their cognitive skills of analysis, evaluation, and reasoning.[ 8 ] Also, they will be able to summarize the content while preserving the meaning. This strategy was developed by Novak during the years 1972-1992 based on Ausoble's learning theory.[ 2 ]

The effectiveness of using concept mapping in student's achievement and interest[ 9 ] and self-efficacy[ 10 ] has been shown previously. Its efficacy in learning and evaluation of critical thinking in music, mathematics, and engineering has led nurses to use this learning strategy.[ 2 ] Use of concept mapping in clinical learning activities improves critical thinking and encourages students to comprehensively observe the patients, and organize and process the complex information. Furthermore, it enables the students to evaluate what they have learned and what they need to learn.[ 1 , 8 ] In a recent research, concept mapping was used as a teaching strategy in the development of critical thinking skills of eight undergraduate nursing students. The researchers designed a concept mapping rubric using Tanner's Clinical Judgment Model to help students construct clinical cases for the development of appropriate clinical judgment skills. Qualitative evaluation of concept mapping activity and rubric revealed that the students positively approached this experience and evaluated it as a means for better clinical decision making and enhancement of clinical judgment.[ 11 ]

Despite the potential benefit of concept mapping in the clinical context, nursing students are encouraged to write nursing care plan for their patients while they see the nursing process as time-consuming paperwork not leading to critical thinking. The more use of nursing process might be due to the fact that clinical instructors, nursing students, and even nursing staff are more familiar with traditional nursing process comparing to concept mapping. However, the use of nursing process (care plan) as the instrument for problem-solving or enhancing the art and creativity of nursing, and also as a method of providing individualized care has been challenged.[ 12 ] Furthermore, it was recognized that the students prefer reflection compared to written nursing care planning.[ 13 ]

Admitting the distinction between nursing process and concept mapping, some researchers compared the effects of these two strategies on critical thinking skills of nursing students.[ 8 , 14 ] The findings of these researches provide no significant difference between these two methods of care planning in promoting critical thinking. It seems that concept mapping should not be seen as a separate strategy for care planning. To use concept mapping, students need to comprehensively understand nursing process. Therefore, concept mapping based on nursing process might possibly add some benefit to traditional nursing process.

Another point worth mentioning is the approach used in measurement of critical thinking. Critical thinking skills tests used in most studies are more appropriate for measurement of critical thinking in a general context, while measurement of discipline (nursing)-based critical thinking needs appropriate planning and careful implementation. Complexities of clinical teaching and the difficulties in measurement of domain-specific critical thinking might be the reason for the insufficient evidence in this regard. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the effects of concept mapping using nursing process on nursing-specific critical thinking, and its components of cognitive skills and habits of mind.

Box 1: Critical thinking skills and habits of the mind for nursing

Critical thinking skills.

- Analyzing: Separating or breaking a whole into parts to discover their nature, function, and relationships

- Applying standards: Judging according to established personal, professional, or social rules or criteria

- Discriminating: Recognizing differences and similarities among things or situations and distinguishing carefully as to category or rank

- Information seeking: Searching for evidence, facts, or knowledge by identifying relevant sources and gathering objectives, subjective, historical, and current data from those sources

- Logical reasoning: Drawing inferences or conclusions that are supported or justified by evidence

- Predicting: Envisioning a plan and its consequences

- Transforming knowledge: Changing or converting the condition, nature, form, or function of concepts among contexts.

Critical thinking habits of the mind

- Confidence: Assurance of one's reasoning abilities

- Contextual perspective: Consideration of the whole situation, including relationships, background, and environment, relevant to some happening

- Creativity: Intellectual inventiveness used to generate, discover, or restructure ideas; imaging alternatives

- Flexibility: Capacity to adapt, accommodate, modify, or change thoughts, ideas, and behavior

- Inquisitiveness: Eagerness to know by seeking knowledge and understanding through observation and thoughtful questioning in order to explore possibilities and alternatives

- Intellectual integrity: Seeking the truth through the sincere, honest processes, even if the results are contrary to one's assumptions and beliefs

- Intuition: Insightful sense of knowing without conscious use of reason

- Open-mindedness: A viewpoint characterized by being receptive to divergent views and sensitive to one's biases

- Perseverance: Pursuit of a course with determination to overcome obstacles

- Reflection: Contemplation upon a subject, especially one's assumptions, and thinking for the purposes of deeper understanding and self-evaluation.

Adapted from: Rubenfeld M, Scheffer B. Critical Thinking Tactics for Nurses. Canada: Jones and Bartlett publishers. 2006;p: 16-17[ 15 ]

M ATERIALS AND M ETHODS

In this quasi-experimental study (post-test only design), a convenient sample of 4 th year nursing students ( N = 32) who were involved in clinical learning experiences participated giving their consent. They were randomly divided into two experimental and control groups. The intervention of the study was conducted for the experimental group during their usual clinical learning experiences in medical surgical and pediatric wards. Both groups had a similar clinical rotation during the study.

The intervention of the study started with a 1-day workshop. In this workshop, the students in the experimental group were introduced with the use of concept maps based on the nursing process.[ 16 ] They used concept mapping for application of nursing process in a given scenario specifically designed for this intervention.

The students worked individually and then in groups to illustrate the relevant information from the presented case and provide the concept mapping. They were instructed to do the following:

Identify the patient and his/her medical diagnosis as the central concept in a box in the middle of the page.

Add the patient's medical diagnosis/chief complaints or reason for hospitalization.

From the patient's medical diagnosis/chief complaints or reason for hospitalization, add as many relevant nursing diagnoses as possible in the boxes related to the main box (categorize all the information presented in scenario).

For each nursing diagnosis, list the subjective and objective data, identified from the case study, that are associated with the diagnosis.

List the current information about medical diagnosis, patient's medical history, risk factors and etiologies, diagnostic tests, treatments, and medications under the relevant nursing diagnoses.

Draw lines between concepts to indicate the relationships. Link the relevant data using different types of lines (e.g. arrows, bolded lines, direct lines, or broken lines), based on the nature of the relationship. On each line, use words (such as related to, lead to, associated with) to explain the relationship between the related concepts.

Draw red lines to connect the related nursing diagnosis.

List the nursing interventions such as assessment, monitoring, procedures, therapeutic interventions (therapeutic communication and or teaching) for each diagnosis.

Add the expected outcomes associated with the nursing interventions for each nursing diagnosis.

Update the concept map based on the new information and patient's possible responses.

The students in the experimental group were required to apply concept mapping at least on two patients during their 10-week clinical practice. The first author provided a weekly 2-h counseling session for the students to present their concept mapping and receive feedback. For ethical considerations, they were told that their attendance in these activities dose not influence their clinical evaluation.

Demographic data including age and grade point average (GPA) were reported by the students on the first page of the instrument used in the study. The instrument for measuring critical thinking was developed based on the instruction provided in another study[ 17 ] in which 17 dimensions of critical thinking under two categories of cognitive skills and habits of mind were considered. Therefore, 14 scenarios were developed to measure analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting, transforming knowledge, contextual perspective, creativity, inquisitiveness, intuition, open-mindedness, perseverance, and self-reflection. The first draft of scenarios was developed by a group of medical surgical and pediatric nursing instructors based on their lived experiences in relation to each critical thinking dimension. The scenarios then were examined in a group of students to ensure that they are thought provoking. Ultimately a panel of experts consisting of experienced faculty members from different nursing specialties confirmed the appropriateness of scenarios for the measurement of the above-mentioned critical thinking dimensions. For the dimensions of confidence, flexibility, and intellectual integrity, the students were offered a free response opportunity to select their own appropriate clinical experiences to illustrate the use of critical thinking.

To develop the test format, each of the 17 critical thinking skills or habits of mind was defined in a square on top of the page specific to that critical thinking. Scenarios developed for 14 critical thinking dimensions were inserted in any of its associated definitions. For the three other mental habits or critical thinking skills, we provided only the definitions. The students were instructed to read the definitions carefully and then try to analyze their related scenarios and/or their own experience. They were asked to carefully explain how they used that critical thinking in a given scenario or their own selected experience. For this purpose, they should write their own analysis based on the two tips given below.

- Write in detail what you will do. Explain in detail so that someone reading your content would be able to realize that you have used that critical thinking

- Explain why you believe your actions illustrate the designated habits or skill.

As the methodology of the study was post-test only design, the tests were given to the students at the end of the 10 th week of their clinical course and they were required to return them in the next 2 weeks. The students were instructed not to share their responses with other students.

All the test packages received from the students were copied and evaluated anonymously by two different evaluators who were blind to the groups. They were instructed to evaluate the students’ responses based on the guideline for evaluation of critical thinking provided elsewhere.[ 17 ] Therefore, the students’ responses were assessed based on three criteria: Identification of critical thinking, justification, and quality of responses. Identification includes a 3-point scale (2, 1 and 0) for clear illustration of the skill or habit, partial identification/misidentification, and no evidence of understanding of the related critical thinking dimension, respectively. Justification was based on a 2-point scale (2, 1) for either adequate or inadequate/absence of reasoning for the actions each student described as an exemplar for the related critical thinking dimensions. Quality or level of the response was scored based on a 3-point scale: 3 for clear and appropriate, 2 for unclear or inadequate description, and 1 for below the student's academic level. Inter-rater agreement on scoring between the two evaluators was measured to maintain reliability. The result showed an agreement between the two evaluators in scoring of more than 80% of the responses. However, a consensus was made between the two evaluators on the scoring of the remained responses. The agreed upon scores in the three criteria for evaluation of critical thinking including identification, justification, and quality of responses were used in data analysis. Data were analyzed by Chi-square, t -test, and Mann-Whitney U test using SPSS, version 16.5.

No statistically significant demographic differences were found between the students of the two groups. Chi-square analysis revealed that the groups were similar in terms of age and overall cumulative GPA. Dimensions to which most of the students did not respond were confidence, flexibility, and intellectual integrity. These dimensions were free choice responses for which no vignettes were provided. Next, the scores from each of the 17 subscales for both groups were analyzed. Table 1 reveals the two groups’ scores related to evaluation criteria in all areas of critical thinking. The experimental group was significantly better in identification ( P = 0.002), justification ( P = 0.001), and quality of responses ( P = 0.003). Table 2 reports the scores related to each dimension of cognitive critical thinking skills. The experimental group performed significantly better in 5 out of 7 areas related to cognitive thinking skills, including analysis ( P = 0.008), logical reasoning ( P = 0.01), discriminating ( P = 0.03), applying standards ( P = 0.001), transforming of knowledge ( P = 0.001). As it is shown in Table 3 , 6 out of 10 areas of habits of mind including perseverance ( P = 0.02), contextual perspective ( P = 0.003), open-mindedness ( P = 0.008), confidence ( P = 0.01), intuition ( P = 0.008), and intellectual integrity ( P = 0.01) were improved.

Mean score of both groups post-test in evaluation criteria for measurement of critical thinking

Mean scores for dimensions of cognitive critical thinking skills in two experimental and control groups

Mean scores for dimensions of habits of mind in two experimental and control groups

D ISCUSSION

This study examined the impact of concept mapping in the clinical context on discipline-based critical thinking skills of nursing students. Based on the results of this study, application of concept mapping resulted in an increase in students’ ability to identify dimensions of critical thinking, justify their reasoning, and provide appropriate explanation. The results also support the effectiveness of concept mapping in the improvement of both cognitive critical thinking skills and habits of mind. Cognitive critical thinking skills improved in this study are analyzing, applying standards, discrimination, logical reasoning, and knowledge transformation, and the improved habits of mind are perseverance, contextual perspectives, open-mindedness, confidence, intuition, and intellectual integrity. This improvement can be attributed to the structure of concept mapping which was implemented based on the nursing process. Although nursing process as a systematic approach to care planning is widely accepted, its relation to critical thinking has been criticized. According to Jones and Brown, nursing process is a linear problem-solving approach which prevents the development of critical thinking in students.[ 18 ] In contrast, development of reasoning map leads to the improvement of interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, explanation, self-regulation, and self-evaluation.[ 19 ]

Habits of mind also have been improved as a result of the intervention of the study. According to Costa, a habit of mind is knowing how to behave intelligently when someone does not know the answer.[ 20 ] He developed 16 habits of mind useful for everyday life. However, in this study, we used habits of mind as defined in the context of nursing. These dispositions or attributes/attitudes or habits of mind could be considered as the elements of a process of reasoning in an individual's character that propels or stimulates an individual toward using critical thinking. The engagement of critical thinking will not occur without these dispositions.[ 21 ] In one study, concept or mind mapping is introduced as a nonlinear teaching strategy that helps students evaluate how they think.[ 22 ] The result of this study is not in agreement with that of the study conducted by Samawi et al . (2006). They concluded that concept mapping does not improve critical thinking skills and dispositions.[ 23 ] However, there are some evidences supporting the effect of concept mapping on critical thinking and critical thinking disposition. One example is the research conducted by Wheeler and Collins using a pre-test – post-test design with control group to figure out the effect of concept mapping on critical thinking skills of nursing students. Although they did not find any significant difference between experimental and control groups, their within-group results showed that concept mapping is effective in helping students develop critical thinking skills.[ 8 ] In another study performed by Atay and Karabacak (2012), the effects of care plans prepared using concept maps on the critical thinking dispositions of students were investigated in a pre-test – post-test control group design. The critical thinking dispositions of the groups were measured using the California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory. They found a significant difference in the total and sub-scale post-test scores between the experimental and control groups.[ 24 ]

There is one study conducted in Iran in which the effectiveness of concept mapping on critical thinking was confirmed.[ 25 ] Other studies mostly focused on determining the effects of concept mapping as compared to other strategies. In a study conducted in Iran, concept mapping was compared with integrated method of learning. Researchers concluded that concept mapping is a better strategy in developing meaningful (deep) learning.[ 26 ] In another study, concept mapping was compared with lecture to find out its effectiveness on learning, wherein no significant difference was found between the two groups of the study.[ 27 ] However, a different finding was revealed in another study in which concept mapping was found to be better than lecture in producing meaningful learning.[ 28 ]

The present study is different from the other studies mentioned. In the current study, concept mapping based on nursing process was used in the context of clinical experience, which is more appropriate to nursing as a practical field. Also, critical thinking was measured using scenarios or real clinical experience. Nonetheless, the students did not respond completely to all the critical thinking dimensions. In another study aiming at determining the reliability of vignettes for measurement of critical thinking also, the students did not respond to all dimensions.[ 17 ] But there is an important difference between these two studies. In the current study, the students’ response to the vignettes was more than that to their own clinical experiences, while the opposite was true about that study. This difference may be attributed to the different contexts of these two studies. It appears that in the context of the present study, the students prefer the structured situations for thinking and have low motivation to reflect on their own experiences. These findings could be considered as the hints to produce a more motivating environment in which the students have more contribution. Such a motivating and supportive atmosphere is more important when we consider that concept mapping as well as other strategies known to be effective in the improvement of critical thinking (e.g. reflection) are time consuming compared to conventional strategies.[ 16 , 29 ]

In most studies, critical thinking has been measured by context-free tests such as California Critical Thinking Skill Test (CCTST) and the Watson Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (WGCTA).[ 30 , 31 ] In a study, National League for Nursing (NLN) Critical Thinking in Clinical Nursing Practice/PN Examination (NLNCT exam) was used to measure the students’ critical thinking abilities of interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, and explanation. The researchers found that using concept mapping method is not better than or even equal to the traditional care planning in improvement of critical thinking.[ 32 ] Although measurement of discipline-based critical thinking is a challenging issue, the test developed in our study as a nursing-specific test of critical thinking showed acceptable inter-evaluator agreement as a sign of reliability.

The results of this study support the effectiveness of concept mapping on cognitive critical thinking skills and habits of mind. This post-test only design study was conducted on a small sample size. Therefore, further studies on larger sample size and with more rigorous design, such as randomized controlled trials, are needed to generalize the findings. Furthermore, it is suggested that clinical instructors be trained to apply this strategy on their students and its effectiveness on critical thinking be evaluated.

C ONCLUSION

Overall, it can be concluded that concept mapping based on nursing process is effective in the improvement of critical thinking skills and habits of mind. Nursing-specific measurement of critical thinking is feasible and application of concept mapping in clinical context is suggested. However further studies are needed to generalize the finding of this study.

A CKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the Vice-Chancellery of research in Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for the financial support provided for this study (3551). Authors are thankful to instructors and their students for their sincere contribution to this research. Also, the authors would like to thank Dr. Nasrin Shokrpour at Center for Development of Clinical Research of Nemazee Hospital for editorial assistance.

Source of Support: This manuscript is financially supported by Shiraz University of Medical Sciences

Conflict of Interest: Nil.

R EFERENCES

Concept maps: a strategy to teach and evaluate critical thinking

Affiliation.

- 1 University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 53201-0413, USA.

- PMID: 9921788

- DOI: 10.3928/0148-4834-19990101-12

The purpose of this article is to describe a study that implemented concept maps as a methodology to teach and evaluate critical thinking. Students in six senior clinical groups were taught to use concept maps. Students created three concept maps over the course of the semester. Data analysis demonstrated a group mean score of 40.38 on the first concept map and 135.55 on the final concept map, for a difference of 98.16. The paired t value comparing the first concept map to the final concept map was -5.69. The data indicated a statistically significant difference between the first and final maps. This difference is indicative of the students' increase in conceptual and critical thinking.

- Achievement

- Concept Formation*

- Education, Nursing, Baccalaureate

- Nursing Education Research*

- Problem-Based Learning*

- United States

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Findings show that concept maps promote development of critical thinking skills, facilitate integration between theory and practice, develop meaningful learning, promote technology inclusion, promote student collaboration, can lead to better academic scores, and can be used as a tool for the learning progress and assessment.

Fostering critical thinking (CT) is one of the most important missions in medical education. Concept mapping is a method used to plan and create medical care through a diagrammatic representation of patient problems and medical interventions. Concept mapping as a general method can be used to improve CT skills in medical students.

The 3CA (Concept Maps, Critical Thinking, Collaboration, and Assessment) model is a competency-centered approach to instruction in which students learn patterns of critical thinking. The model has four components: (a) concept maps are a visual method for displaying information as nodes with connecting links; the nodes are visual representation ...

Concept mapping activities have been used to enhance critical thinking skills as an essential competency for 21st century learners. However, little information has been provided about the relationship between different concept mapping activities and critical thinking skills. This study aimed to examine the effects of the fill-in-the-map activity and the construct-the-map activity on critical ...

reflective thinking and critical thinking as it relates to their course of study. There are two ways teachers and students can incorporate concept maps into a classroom setting. Teacher generated concept maps are produced based the course material for the on university. These maps are constructed to maximize communicative potential.

1. Introduction. The M3CA model is a skill based approach to mastery learning in college classrooms. The skills students learn are: creating concept maps, critical thinking (asking the questions what, when where, how, and why, ranking concepts in terms of importance, synthesizing, collaborating, and assessing.

Background . Concept maps (CMs) visually represent hierarchical connections among related ideas. They foster logical organization and clarify idea relationships, potentially aiding medical students in critical thinking (to think clearly and rationally about what to do or what to believe).

Concept maps are considered a powerful metacognitive tool that can facilitate the acquisition of knowledge through meaningful learning. Hence concept mapping can be used to promote and evaluate critical thinking. Based on the published nursing literature, the scope of concept mapping is discussed in this paper as a teaching and evaluation ...

Many college students are not progressing in the development of their critical thinking skills. Concept mapping is a technique for facilitating validation of one's critical thinking by graphically depicting the structure of complex concepts. Each of our three studies of concept mapping involved approximately 240 students enrolled in four sections of an introductory psychology course.

In our three studies of concept mapping, we initially established the efficacy of concept mapping for facilitating critical thinking (Harris & Zha, 2013). As an extension of the initial study, we next explored the relative effects of the timing of the construction of concept maps. Finally, the third study explored the relative effects of using ...

Concept Mapping: A Critical Thinking Technique. Charles M. Harris, Shenghua Zha. Published 22 December 2013. Education. Education 3-13. Introduction Criticisms of the quality and outcomes of higher education in the United States continue to generate calls for increased rigor in instruction and in learning. During the early 1980s, there was a ...

Concept maps: A strategy to teach and evaluate critical thinking. Journal of Nursing Education, 38, 42-47. > Link Google Scholar; Daly W.M. (2001). The development of an alternative method in the assessment of critical thinking as an outcome of nursing education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36, 120-130.

The article addresses the use of computer-based concept mapping as a learning strategy, an instructional strategy, and as a collaborative thinking tool, offering guidelines for educators on how to implement these uses in the classroom. Abstract Concept mapping is a mindtool (cognitive tool) that can enhance the interdependence of declarative and procedural knowledge to produce yet another form ...

Creating concept maps encourages critical thinking as learners must analyze, synthesize, and evaluate the relationships between concepts. This promotes a deeper level of engagement with the material. 5. Enhances Problem Solving. Concept maps help learners see the bigger picture and identify potential solutions to problems. They promote a ...

Brune (Brune, 2014) explored the impact of concept mapping on critical thinking ability. The result showed no significant increase in the intervention group for critical thinking skills. Another study (Chen et al., 2011) also showed no statistically significant difference between traditional lecture group and concept mapping group, but after ...

Concept mapping was introduced as a way to support the nursing student to improve upon critical thinking and clinical reasoning and to identify relationships among the patient's health care problems. The present manuscript features the development and evaluation of the Concepto-Plan (C-P), an innovative, holistic care plan that moves away from ...

However, there are some evidences supporting the effect of concept mapping on critical thinking and critical thinking disposition. One example is the research conducted by Wheeler and Collins using a pre-test - post-test design with control group to figure out the effect of concept mapping on critical thinking skills of nursing students. ...

Allocation type was a significant moderator, having a strong effect on concept mapping for critical thinking abilities in randomised studies (g = 0.739, 95% CI 0.356 to 1.122), but its effect is ...

a concept map would provide a tool to. guide their critical thinking until it becomes. inherent or second nature. The concept map, a graphic illustration of key points, guides. the focus of ...

Abstract. Concept mapping is a teaching-learning strategy that can be used to evaluate a nursing student's ability to critically think in the clinical setting. It has been used in disciplines other than nursing to allow the learner to visually reorganize and arrange information in a manner that promotes learning of concepts that interrelate.

Concept mapping activities have been used to enhance critical thinking skills as an essential competency for 21st century learners. However, little information has been provided about the relationship between different concept mapping activities and critical thinking skills. This study aimed to examine the effects of the fill-in-the-map activity and the construct-the-map activity on critical ...

Concept mapping, graphically depicting the structure of abstract concepts, is based on the observation that pictures and line drawings are often more easily comprehended than the words that represent an abstract concept. The efficacy of concept mapping for facilitating critical thinking was assessed in four sections of an introductory psychology course.

The purpose of this article is to describe a study that implemented concept maps as a methodology to teach and evaluate critical thinking. Students in six senior clinical groups were taught to use concept maps. Students created three concept maps over the course of the semester. Data analysis demonstrated a group mean score of 40.38 on the ...