- Case Examples

Based on a composite of a number of real sentinel event reports to The Joint Commission, Case Examples can be used for educational purposes to identify lapses in patient safety and missed opportunities for developing a safety culture. This learning resource highlights safety actions and strategies to have a better result. Stay current with what is happening at The Joint Commission by subscribing to our free publications.

- Joint Commission Online

- Quick Safety

- What is HSO?

In recognition of Canadian Patient Safety Week 2022, we are pleased to share these case studies featuring diverse examples of how our healthcare partners are applying the Canadian Quality and Patient Safety Framework in their settings. We hope you find them useful.

Access the Canadian Quality and Patient Safety Framework Evaluation here .

Early adoption of the Canadian Quality and Patient Safety Framework at Eating Disorders Nova Scotia : A useful tool for self‑assessment, education, and program development

Shaleen Jones is the Executive Director of Eating Disorders Nova Scotia . The community‑based organization has been around for nearly 25 years. Eating Disorders Nova Scotia operates on a core belief that no one should have to go through an eating disorder alone, and everyone should have access to the resources and supports needed for recovery. Along with peer‑support programs, the organization provides psychologists, dieticians, and other professional supports, based on clients’ preferences and needs. Operating out of Nova Scotia, the organization has extended its services from in‑person to virtual and now serves people across Canada through their Peer Support Programs. The pandemic helped spur the transition. “We wanted to reach more people with the resources available, and once we went virtual, it opened up a whole new world … we’ve had a 400% increase in service,” said Jones. Read More

Aligning quality and patient safety with policy and practice at Nova Scotia Health : Applying the Canadian Quality and Patient Safety Framework

“We have seen progress and benefits of our initiatives and the Canadian Quality and Patient Safety Framework . It really helps to focus and guide our work,” says Gail Blackmore, Senior Director of Quality Improvement and Safety at Nova Scotia Health . Blackmore is using the Framework to align policy and practice. The organization can embed Framework goals into daily practice by ensuring that reporting templates and other everyday practices align with the broader goals of patient safety and quality. “When there’s alignment, it’s more likely to be successful,” she says. Read More

Canadian Quality and Patient Safety Framework : A tool supporting organizational priorities, quality and safety process improvements

St. Joseph’s Health Care London is a leading teaching hospital in Ontario and part of London’s academic sciences community. As a Catholic health care organization, St. Joseph’s is a values‑driven organization with the aim of caring for the community, particularly, poor, marginalized, and underserved populations. Members of the St. Joseph’s Quality Council and representatives from the Quality Committee of the Board participated in a case study to learn about their experiences and views on the Canadian Quality and Patient Safety Framework. The Framework and its implementation resources aim to accelerate quality and patient safety across the Canadian health systems by focusing stakeholders on five goals for safe and quality care. These goals include people‑centred care, safe care, accessible care, appropriate care, and integrated care. Participants said the Framework validated their organizational quality and safety processes and has the potential to support improvements aligned with St. Joseph’s strategic goals. They recommended professional colleges and training organizations consider the Framework to strengthen quality and integration practices. Read More

Canadian Patient Safety Week Webinar: Safety Conversations Start with a Safe Workplace and Workforce

In partnership with Health Excellence Canada , we are hosting a joint webinar on Thursday, October 27, from 12 -1 pm ET. This interactive webinar will convene a panel of senior leaders to share their experience designing and implementing the new Health Standards Organization (HSO) Workforce Survey on Well-Being, Quality and Safety (WSWQS). Participants will hear about the survey methodology, validation process, and learnings from early adopter health care organizations.

Learn More and Register

Cookies on the NHS England website

We’ve put some small files called cookies on your device to make our site work.

We’d also like to use analytics cookies. These send information about how our site is used to a service called Google Analytics. We use this information to improve our site.

Let us know if this is OK. We’ll use a cookie to save your choice. You can read more about our cookies before you choose.

Change my preferences I'm OK with analytics cookies

Patient safety review and response case studies by clinical specialty

This page shows case studies, listed by clinical specialty, of where the National Patient Safety Team worked with partners to address issues identified through its review of recorded patient safety events.

Urgent/emergency care

General medicine, intensive care, obstetrics and gynaecology/midwifery, paediatrics and child health, primary care.

You can find out more about our processes for identifying new and under recognised patient safety issues on our using patient safety events data to keep patients safe and reviewing patient safety events and developing advice and guidance web pages.

- COVID-19 swab snapped in tracheostomy

- Risk of dose error when using intraosseous lidocaine in children

- ePrescribing systems and insulin combinations

- Risks of ingestion of alcohol-based hand sanitiser

- Risk of airway obstruction from green anaesthetic swabs

- Dual purpose naso-gastric tubes with ENFit® connectors and the risk of aspiration

- Diagnosis and management of supraglottitis

- Sucrose vial cap identified as potential choking hazard in babies

- The risk of aspiration from orally administered contrast media with spigotted nasogastric tubes

- Metacarpal wrong site surgery – inconsistent terminology used to describe anatomy

- Osmotic Demyelination Syndrome from rapid correction of severe hypo/hypernatraemia

- Ensuring timely updates to clinical risk assessment and management triage tools in emergency departments

- Ingested gel toilet discs

- Delayed oxygenation of neonate during resuscitation when oxygen not ‘flicked’ on

- Equipment falling onto critically ill patients during intrahospital transfers

- Misapplication of spinal collars resulting in harm from unsecured spinal injury

- Ensuring compatibility between defibrillators and associated defibrillator pads

- Ensuring pregnant women with COVID-19 symptoms access appropriate care

- Overdose of oral vitamin D related to frequency and duration of treatment

- Administration of chemotherapy and reactivation of Hepatitis B

- Delay in treatment with prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC)

- Harm from catheterisation in patients with implanted artificial urinary sphincters

- Confusion between different strength preparations of alfentanil

- Distinguishing between haemofilters and plasma filters to reduce mis-selection

- Variation in use of cardiac telemetry

- Ceftazidime as a 24-hour infusion

- Tacrolimus – risk of overdose when converting from oral to intravenous route

- Haloperidol prescribing for confused/agitated/delirious patients

- Ensuring oxygen delivery when using two step humification systems

- Pregnancy tests not performed before anaesthesia

- Ventilator left in standby mode

- Sudden patient deterioration due to secretions blocking heat and moisture exchanger filters

- Anaesthetic machines used as ventilators: issues with circuit set up

- Importance of ‘tug test’ for checking oxygen hose when transferring a patient to a portable ventilator

- Use of trimethoprim in women of child-bearing age

- Assessment of risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) when prescribing combined hormonal contraceptives

- Harm from prescribing and administering Syntometrine when contraindicated to woman with significantly raised BP

- Unnecessary caesarean section for breech presentation if not scanned on the day

- HIV prophylaxis in women and new-borns

- Ensuring the safe use of plastic cord clamps at caesarean section

- Warning on the use of ethyl chloride during fetal blood sampling

- Risk of babies becoming unwell following move to virtual home midwifery visits

- Testing ammonia levels in children

- Unintentional perforation of oesophagus in neonates from invasive procedures

- Chemical burn to a neonate from use of chlorhexidine

- Risk of harm from spinal administration of anaesthetic agent containing preservative

- Hip cement – different expiry dates for separate components in the same pack

- Bone cement implantation syndrome

- Surgical skin preparation solution entering the eye during surgery

- Retained surgical instrumentation and complex procedures involving multiple teams and equipment

- Unintentional retention of bone cement following hip surgery

- Monitoring patients taking nitrofurantoin for potential lung disease

- Unintended bolus of medication if infused at speed from residual space in giving set

- Infrared temperature screening to detect COVID-19

Patient Safety and Communication Case Studies

Hawai‘i Pacific Health was named a 2019 HIMSS Davies Enterprise Award recipient for leveraging the value of health information and technology to improve outcomes. The three case studies below cover patient safety workflow enhancements, virtual communication solutions and reducing length of stay.

Case Studies

1. i-pass nurse handoffs.

Hawai‘i Pacific Health recognized that communication amongst nurses at shift change in the neonatal intensive care unit was a patient safety improvement opportunity for the high volume, high acuity unit. In order to address this, they aimed to apply high reliability techniques and leverage EHR-based tools to bring the evidence-based I-PASS handoff structure to nursing handoffs. To learn more, listen to the use case video below or download the use case presentation.

2. Putting the IT in CapITation

Hawai‘i Pacific Health recognized there were a variety of opportunities to ensure its growing patient population received quality care in a timely fashion and was challenged by a limited supply of physicians and a changing health care environment to do so. To combat these challenges, cross-functional teams worked together to implement virtual e-visits and other patient communication tools.

3. Decreasing Case-Mix Adjusted Average Length of Stay

Hawai‘i Pacific Health recognized that safely decreasing length of stay was a means to increase service capacity while reducing internal costs. In order to address this, Hawai‘i Pacific Health set a system level goal to reduce case-mix adjusted average length of stay (CMI-adjusted ALOS) by a half-day over a period of five years.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Qual Health Care

- PMC10656601

Improving patient safety governance and systems through learning from successes and failures: qualitative surveys and interviews with international experts

Peter d hibbert.

Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences, Macquarie University, 75 Talavera Rd, Macquarie Park, NSW 2109, Australia

IIMPACT in Health, Allied Health and Human Performance, University of South Australia, GPO Box 2471, Adelaide SA 5001, Australia

Sasha Stewart

Louise k wiles, jeffrey braithwaite, william b runciman, matthew j w thomas.

Appleton Institute, School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, 114-190 Canning Street, Rockhampton, Queensland 4700, Australia

Associated Data

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study is not publicly available.

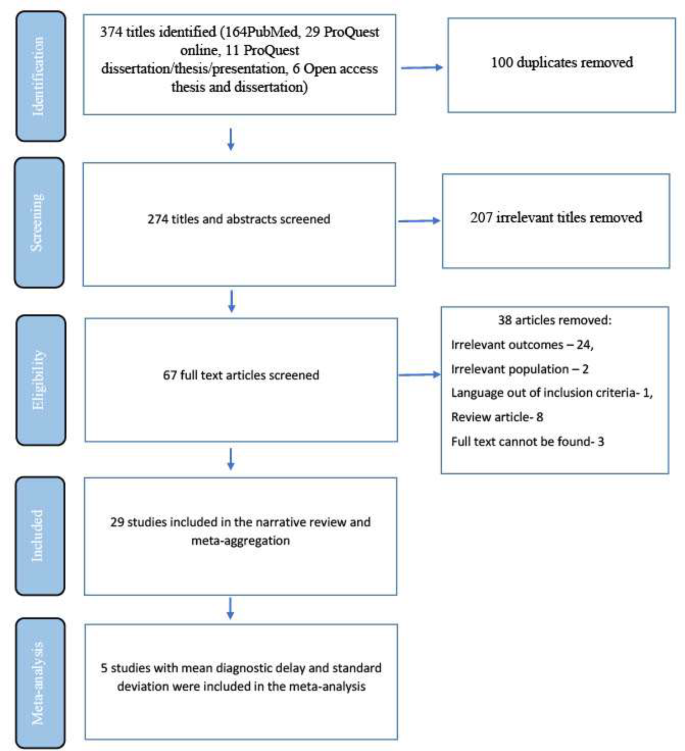

Patient harm is a leading cause of global disease burden with considerable morbidity, mortality, and economic impacts for individuals, families, and wider society. Large bodies of evidence exist for strategies to improve safety and reduce harm. However, it is not clear which patient safety issues are being addressed globally, and which factors are the most (or least) important contributors to patient safety improvements. We aimed to explore the perspectives of international patient safety experts to identify: (1) the nature and range of patient safety issues being addressed, and (2) aspects of patient safety governance and systems that are perceived to provide value (or not) in improving patient outcomes. English-speaking Fellows and Experts of the International Society for Quality in Healthcare participated in a web-based survey and in-depth semistructured interview, discussing their experience in implementing interventions to improve patient safety. Data collection focused on understanding the elements of patient safety governance that influence outcomes. Demographic survey data were analysed descriptively. Qualitative data were coded, analysed thematically (inductive approach), and mapped deductively to the System-Theoretic Accident Model and Processes framework. Findings are presented as themes and a patient safety governance model. The study was approved by the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Twenty-seven experts (59% female) participated. Most hailed from Africa (n = 6, 22%), Australasia, and the Middle East (n = 5, 19% each). The majority were employed in hospital settings (n = 23, 85%), and reported blended experience across healthcare improvement (89%), accreditation (76%), organizational operations (64%), and policy (60%). The number and range of patient safety issues within our sample varied widely with 14 topics being addressed. Thematically, 532 textual segments were grouped into 90 codes (n = 44 barriers, n = 46 facilitators) and used to identify and arrange key patient safety governance actors and factors as a ‘system’ within the System-Theoretic Accident Model and Processes framework. Four themes for improved patient safety governance were identified: (1) ‘safety culture’ in healthcare organizations, (2) ‘policies and procedures’ to investigate, implement, and demonstrate impact from patient safety initiatives, (3) ‘supporting staff’ to upskill and share learnings, and (4) ‘patient engagement, experiences, and expectations’. For sustainable patient safety governance, experts highlighted the importance of safety culture in healthcare organizations, national patient safety policies and regulatory standards, continuing education for staff, and meaningful patient engagement approaches. Our proposed ‘patient safety governance model’ provides policymakers and researchers with a framework to develop data-driven patient safety policy.

Introduction

Avoidable patient harm remains one of the leading causes of global disease burden, despite considerable progress being made, especially in developing nations [ 1 ]. In high-income countries, approximately one in ten patients experiences an adverse event [ 2 ]. In low- and middle-income countries, it is estimated that 134 million adverse events occur in hospitals per year contributing to 2.6 million deaths annually [ 2 ].

An increasing recognition of the importance of patient safety has catalyzed the formation of international and national quality and safety alliances to set priorities and shape policy, and there is now a large body of evidence relating to improvement strategies for reducing harm in health care [ 3–6 ]. Recent international efforts include the World Health Organization’s Global Patient Safety Action Plan [ 2 ] and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development’s safety measurement system [ 7 ].

Despite extensive resources and efforts to reduce harm, more evidence is needed in relation to which aspects of patient safety governance provide value in terms of improving outcomes for patients and health systems, versus those that are not effective and therefore waste resources. This study aimed to examine the perspectives of international patient safety experts to identify the [ 1 ]: nature and range of patient safety issues being addressed, and [ 2 ] aspects of patient safety governance and systems that are perceived to provide value (‘successes’) or are not effective (‘failures’) in improving outcomes for patients.

Study design, sample, and setting

A case study methodology [ 8 ] using surveys and interviews was employed and is described according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research Checklist ( Supplementary Appendix 1 ). Case study approaches are appropriate to generate an in-depth, multifaceted understanding of a complex issue such as patient safety interventions and governance in its real-life context [ 9 ]. We studied multiple cases simultaneously (a collective case study approach) to enable a broad understanding of the effectiveness of patient safety governance [ 9 , 10 ]. Experts, Fellows, and Academy members (International Academy of Quality and Safety, IAQS) from the International Society for Quality in Healthcare (ISQua) were made aware of this study via ISQua communication channels (including website notices, newsletters, and email circulations) which directed them to the study website. ISQua is a global professional organization that focuses on facilitating improvements in the quality and safety of health care [ 11 ]. At the time of the study, ISQua had 1555 Experts, Fellows, and Academy members, with representation across 83 countries and 6 continents [ 12 ]. All participants provided written informed consent prior to study enrolment. Participation was voluntary and no compensation was provided. Participants were assured that no identifiable information would be collected or reported. The study received ethics approval from the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (no. 203 467).

Data collection

Data collection occurred between May and September 2021, and comprised internet-based surveys (Microsoft Forms) ( Supplementary Appendix 2 and 3 ) and one-on-one in-depth semistructured interviews (telephone or web-based platform; Zoom) ( Supplementary Appendix 4 ). Two researchers (P.D.H. and S.S.) conducted all interviews; both have patient safety experience, with one (P.D.H.) being an ISQua Fellow. Surveys and interviews sought to explore and understand experts’ experiences about patient safety initiatives in which they were involved. Participants were invited to discuss (via case report or interview) an example of either a patient safety ‘success’, or a persistent problem (‘failure’), and to reflect on the lessons learnt and factors perceived as contributing to improvements or failure to achieve the desired outcomes. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. All data were anonymized for reporting.

Data analysis

Survey and interview data were analysed thematically using inductive and deductive approaches [ 13 ]. Participants’ perspectives on the key barriers and facilitators to effective patient safety efforts (taken from case study ‘successes’ and ‘failures’) were coded and deductively mapped to the System-Theoretic Accident Model and Processes (STAMP) framework [ 14 ]. STAMP is generally applied to accidents or hazard analysis; however, it has been used to analyse systems for governance, for example in road safety [ 15 ], electronic medical record safety [ 16 ], and risk management in hospitals [ 17 ]. It is underpinned by systems and control theory, and considers constraints and controls across system development and operations. STAMP recognizes that in today’s complex world, the causes of accidents are generally nonlinear, inter-related, and represented across multiple layers in the system. Patient safety governance can also be considered as a complex sociotechnical system with a series of hierarchical control structures that impose constraints from high levels to low levels [ 18 ]. The resistance and inertia in improving patient safety at scale may be related to its characteristic as a complex sociotechnical system.

The aspects of patient safety governance and systems perceived to provide value or not in improving outcomes for patients were analysed inductively (thematic analysis) [ 19 ].

Using the constant comparison method, participants’ perspectives were deductively mapped to the content of the STAMP framework [ 20–22 ], and then iteratively refined into a novel overarching systems model with key themes for patient safety governance and improvement. Example quotes from interviewed participants were selected for publication.

Rigor and trustworthiness

The interview schedule was pilot tested on three non-ISQua members with patient safety experience—their data were not included in the study. All interviews were coded by one researcher (S.S.), with a random subsample (n = 6, 22%) coded independently by a second researcher (L.K.W.). The two researchers met to ensure code consistency, before agreeing on the final coding frame and resultant themes and subthemes. Interview data analysis was undertaken by one researcher (L.K.W.) and verified by another (S.S.). Further discussions were held to confirm saturation across sampling, data collection, and analysis domains for each approach [ 23 ]. In the inductive analysis, the researchers ensured that no new codes or themes were being generated and no new theoretical insights gained from the data [ 23 ]. For the deductive component, the two researchers ensured that the STAMP framework hierarchical levels were adequately represented in the data (i.e. that all levels within the formulated overarching systems model were sufficiently replete with examples from the data). Interview transcripts and summaries of the analysis were sent to participants to ensure they were satisfied with interpretations of their data, with no suggested amendments received.

Study sample

Twenty-seven ISQua participants (n = 16, 59% female) completed the survey and then an interview, representing a response rate of 1.7%. Most hailed from Africa (n = 6, 22%), and Australasia or the Middle East (n = 5, 19% each) and were employed in hospital settings (n = 23, 85%). Participants reported a blend of experience across healthcare improvement (89%), accreditation (76%), organizational operations (64%), and policy (60%). According to participants and illustrated via case study descriptions, the nature and range of patient safety issues being addressed in our sample varied in topic (n = 14), with specific examples of adverse events and patient harm most commonly discussed (n = 5, 38%) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Participant profile.

Synthesis and interpretation

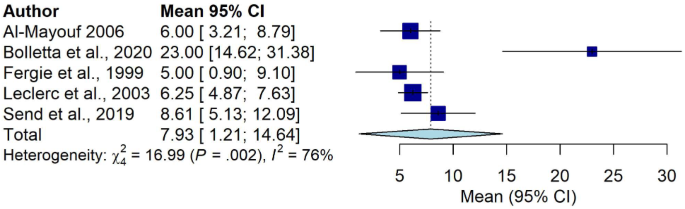

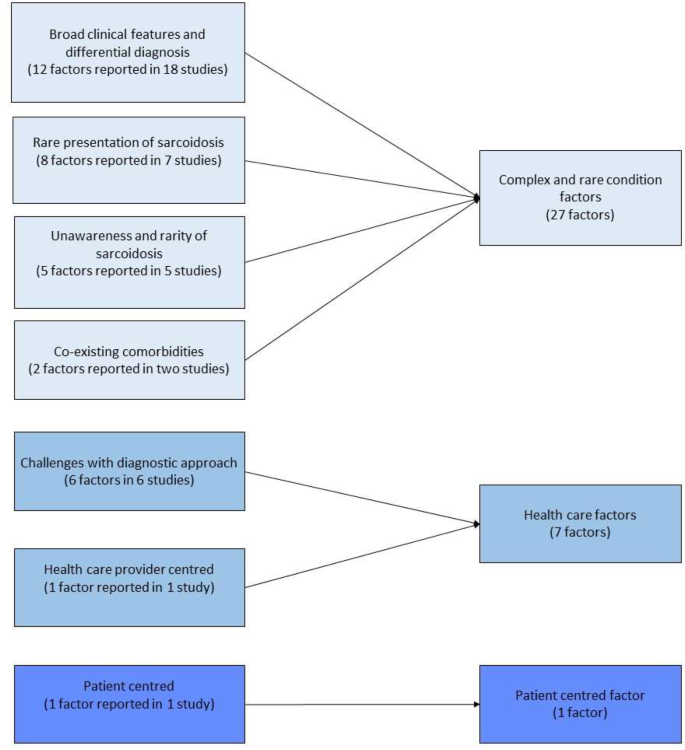

Thematically, a total of 532 textual segments (n = 247 barriers, n = 285 facilitators) were grouped into 90 factors (n = 44 barriers, n = 46 facilitators) and were used to identify key factors relating to patient safety governance which were aligned with prioritized STAMP framework hierarchical levels [ 14 ] ( Figure 1 ). Factors were also used to synthesize four distinct yet interrelated and overlapping themes (n = 12 subthemes) relating to aspects of patient safety governance and systems perceived as valuable or ineffective; these are discussed below and summarized, with illustrative quotes, in Tables 2–4 . A matrix of codes, STAMP framework hierarchical levels, and themes appears in Supplementary Appendix 5 .

Adapted STAMP systems model for patient safety governance [ 14 ]. Note: Control and Feedback mechanisms in italics. Key factors related to patient safety governance and systems are noted in boxes with borders; deeper coloured boxes with bolded text show factors with ten or more responses from participants. These are organised into different STAMP hierarchical levels in plain bold text and sub-levels in boxes with borders. Factors were aggregated including across barriers and facilitators and renamed into neutral factors (for example, lack of access to healthcare (a barrier) and access to healthcare (a facilitator) were aggregated and renamed access to healthcare. Factors mentioned by less than 3 participants were excluded. See Supplementary Appendix 5 for full dataset results.

Table 2.

Theme 1 (organizational culture, safety and quality mindset) summary, illustrated with participant quotations.

Theme 1: Organizational culture, safety, and quality mindset

The organizational culture, safety, and quality mindset was the most frequently mentioned barrier or facilitator by participants comprising 412 (or 77% of) textual segments ( Supplementary Appendix 5 ).

Organizational culture and leadership priorities

Participants were emphatic that a health service organization’s culture is ‘critical’ to setting its safety, quality mindset and efforts. The approaches and activities prioritized by leadership and management teams are indicative of culture and reflect their commitment to safety and quality. These filter through the organization in discussions and meetings with staff ( Table 2 ).

Participants reported that leaders’ priorities are largely shaped by their accountabilities and how success is measured within the organization (e.g. financial key performance indicators versus quality outcomes), and these priorities can either promote or downgrade the importance placed on safety and quality. Safety should be ensconced within the organizational development of health services through adequate clinical representation on Boards, and by employing models of safety improvement with proven track records. The efforts of individual safety managers who can leverage political networks and priorities make a real difference in producing positive outcomes for the community ( Table 2 ).

Staff engagement

Many participants suggested that safety culture and awareness could be deepened with meaningful staff engagement through partnership in nonhierarchical consultations rather than imposing preconceived solutions, thereby engendering ownership of issues and initiatives. Leaders also need to provide consistent clear messaging and follow-up with actions that align with stated patient safety priorities ( Table 2 ).

Endorsement of quality

Healthcare employees’ behaviour is guided by decisions from their management teams; therefore, quality improvement initiatives must be endorsed by organizational leaders. If the organization promotes reflective practice and staff-led safety and quality improvement initiatives, a sustainable culture of improvement can grow. On the other hand, factors identified as negatively influencing safety culture included ‘cover up’ activities borne out of concerns for reputational protection and a heavy focus on accreditation compliance as an endpoint rather than business-as-usual. There was a clear consensus that nonpunitive approaches that seek to unearth learnings for future improvement best support patients and staff ( Table 2 ).

Theme 2: Policies and processes to investigate, implement, and demonstrate impact

Factors related to policies and processes to investigate, implement, and demonstrate impact comprised 68% (361/532) of the textual segments mentioned by participants ( Supplementary Appendix 5 ).

National-level reporting and legislative mandates were considered an important drive for organizations to prioritize safety programs and promote transparency in incident reports and learnings ( Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Theme 2 (policies and processes to investigate, implement, and demonstrate impact) summary, illustrated with participant quotations.

Regulatory bodies

Regulation agencies and accreditation processes were considered key to ensuring accountability, particularly when underpinned by government support and industry-based partnerships. National-level standards were viewed favourably; however, potential negative consequences of ‘setting the accreditation bar too high’ included the closure rather than development and improvement of ‘problematic’ health services. Other potential limitations of accreditation included setting patient safety standards too low, inadequate assessment, and failure to partner with health services to undertake the necessary improvements ( Table 3 ).

Processes—data informing and informed by practice

Many participants described the value of high-quality data systems such as incident reporting and trigger tools that align with key safety priorities. It was noted, however, that incident reporting systems do not provide the complete picture. Nontraditional data sources should be used to validate and enhance information from reporting systems and identify issues that are not routinely reported (e.g. use of low value procedures, rates of and time to patient follow-up care). Data ‘drill-downs’ should be undertaken by dedicated quality and safety managers, in conjunction with staff discussions, to flesh out the underlying reasons for ‘why’ and ‘how’ things go wrong. Engagement by healthcare professionals is often low due to a failure of organizations to ‘close the loop’ in response to identified issues, coupled with the burden of completing often lengthy incident forms ( Table 3 ).

Implementation, interpretation, and demonstrating impact

Participants espoused the value of implementation approaches that ‘start somewhere’ and are ‘clinically relevant’, such as risk stratification and pain score assessments on hospital presentation. Contrarily, strategies undertaken at the level of paperwork (e.g. hospital procedural documents) are sometimes viewed as not resulting in meaningful improvements and done ‘for show’ ( Table 3 ).

Some examples of limitations to demonstrating impact from initiatives included inadequate assessment of safety issues, rolling out off-the-shelf solutions rather than tailored context-sensitive approaches, inappropriate selection of outcome measures (i.e. flawed unidimensional short-range metrics), and too much focus on either celebrating improvements or calling out residual deficiencies (e.g. acceptability thresholds for hand hygiene rates). Political imperatives can lead to patient safety issues ‘of the moment’ gaining attention at the expense of others, such as increased health service activity or ambulance queuing, or hospital readmission rates ( Table 3 ).

Theme 3: Staff support, upskilling, and shared learning

Factors related to staff support, upskilling, and shared learning comprised 68% (374/532) of the textual segments mentioned by participants ( Supplementary Appendix 5 ).

Staff support and capacity

A supportive organizational ethos that focuses on learning rather than blame will develop staff as agents of patient safety change. Staff can then feel comfortable to report issues, fostering positive reporting practices within the organization. Staff in safety and quality roles needs to be supported with sufficient resourcing to ensure a critical mass of field teams and managers, and allowed license to balance their safety responsibilities with other clinical pressures ( Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Theme 3 (staff support, upskilling, and shared learning) and Theme 4 (Patient engagement, experiences, and expectations) summary, illustrated with participant quotations.

Staff upskilling

Healthcare workers often lack safety-specific technical knowledge and skills to adequately understand and drive improvement agendas within their organizations. Thus, career-long safety education should be made available. Responsibility for continuous learning falls within the remit of both university and teaching hospital sectors and is reflective of an organization’s commitment to building capacity for safety. Practical and experiential learning opportunities are especially valuable in helping staff to appreciate the nature and range of patient safety problems ( Table 4 ).

Education on foundational topics is also essential and should encompass the influence of social determinants of health to enhance understanding of responsible management of health funding and use of cost-effectiveness measures. Human factors were also highlighted as a key educational target. Shaping helpful staff attitudes, behaviours, and communication skills is critical to these being perpetuated within healthcare organizations ( Table 4 ).

Shared learning

To achieve ongoing improvement in the patient safety space, there must be opportunities for all stakeholders to share information and learnings which tend to increase buy-in from all sides. Webinars and other virtual modalities were suggested as a means of communication across a country ( Table 4 ).

Theme 4: Patient engagement, experience, and expectations

Factors related to patient engagement, experience, and expectations comprised 22% (118/532) of the textual segments mentioned by participants ( Supplementary Appendix 5 ).

Patient engagement and experience

There was widespread recognition that patient engagement is pivotal to patient safety. However, in some regions, patient-centeredness is still a relatively new concept that is not embedded in organizational policies, education, and practice. Nevertheless, there was general agreement that hearing patients’ personal stories positively influences healthcare professionals’ attitudes towards patient safety, with some subsequently attracted to patient safety roles. Leadership training, in particular, could benefit from incorporating ‘patient experience’ first-hand from patient advocates ( Table 4 ).

Patient expectations

Patients’ health literacy influences their own expectations and attitudes towards safety. Where levels of health literacy are low, it was reported that some patients almost ‘expect and accept’ adverse events. Conversely, participants reflected that well-informed patients are active partners in their own care, and can advocate for their own safety especially when things go wrong. Public education, implemented early and with due sensitivity of cultural nuances, may enhance patients’ self-efficacy through a heightened understanding of basic healthcare principles. Collaborative person-centred approaches and general improvements in health literacy can help drive public pressure and expectations of the healthcare system, and organizations must keep pace with these developments.

Statement of principal findings

The nature and range of patient safety issues being addressed in our sample varied in topic (n = 14), with specific examples of adverse events and patient harm, relating to medical procedures (e.g. postpartum haemorrhage, transvalvular percutaneous aortic valve replacement, and central line infection) most commonly discussed (n = 5, 38%). Four themes for improving patient safety emerged from this study [ 1 ]: an organizational culture that prioritizes patient safety [ 2 ]; policies and processes to investigate patient safety issues, and implement and demonstrate impact from initiatives [ 3 ]; supporting staff to foster appetite, capacity, and participation in safety efforts, and offering upskilling and shared learning opportunities; and [ 4 ] engaging patients to explore and enhance their experiences and expectations of safe health care. Barriers and facilitators, and the strategies identified for addressing them, were related to the crafted themes and interconnected within a broader patient safety system.

While these four themes may appear particularly familiar in the context of the patient safety agenda over the past few decades, the results of this study underpin that these areas remain a priority. Further, given the relative lack of new emergent themes, the broader results of the study could be interpreted from the perspective that our recent efforts in these areas have not been sufficient, especially in the face of the many barriers identified by the experts in this study.

Strengths and limitations

Case design methodology is suitable to answer questions of ‘how’ and ‘why’ in a real-life context [ 8 ]. Our sample size of 27 experts was appropriate to explore study aims and achieve data saturation, within pragmatic considerations [ 24 ]. The response rate (1.7%) was low but consistent with expectations for a large-scale email circulation approach [ 25 ]. Our findings are a function of the convenience sampling approach used. A key study strength was the international perspectives captured through ISQua members, and the triangulation of contexts across countries, health services, and policy settings [ 26 ]. Data collection sought case study examples of aspects underpinning high-value and/or ineffective patient safety governance; however, participants’ responses varied in detail. To enhance credibility, we double-coded data from a 20% participant subsample and used a combined deductive-inductive analytical approach. Our findings are a reflection of the STAMP framework chosen for analysis; additional or alternative groupings of critical patient safety governance and system factors may have surfaced from deductive mapping to other frameworks, especially those that centre around or more broadly represent ‘culture’, which comprised 77% of mentioned factors by our participants. Data collection occurred in English; for some experts, this was not their first language which could introduce bias. To mitigate this, we cross-checked interview transcriptions against the audio files to correct for language mistakes. Study participants worked mostly in hospital settings and developing countries; therefore, it is unclear how experts from other settings experience patient safety and how this might affect future studies and recommendations.

Interpretation within the context of the wider literature

When examined as a whole, common to each of the themes is a focus on the primary actors in patient safety: the patient; the healthcare workforce; and the organization. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s framework for respectful management of serious clinical adverse events first emphasised these layers over a decade-ago [ 27 ], and the findings of our research emphasize that globally our work needs to continue to develop across each of these ‘layers’ a culture that underpins safety and quality.

Reflecting the outermost layer of the ‘organization’, the study’s most frequently mentioned barrier or facilitator, ‘organizational culture and safety and quality mindset’, features prominently in the well-documented ‘third age in safety’ [ 28 ]. Here, the focus is on trying to understand and strengthen everyday features of work within complex sociotechnological systems that promote safety [ 29 ]. The achievement of a ‘restorative just culture’ has become an important component of this. Its function is to fashion appropriate responses to evidence of errors and failures and to preserve the possibility of learning while holding people accountable for unacceptable behaviours [ 29 ]. Therefore, our study’s key contribution to the literature lies in the findings embodying restorative just culture principles [ 30 ], and operationalizing these within a patient safety governance system [ 31 ]. Restorative responses to patient safety incidents are ‘a voluntary, relational process where all those affected by an adverse event come together in a safe and supportive environment, with the help of skilled facilitators, to speak openly about what happened, to understand the human impacts, and to clarify responsibility for the actions required for healing and learning’ [ 32 ]. This definition speaks directly to the themes identified by study participants, with our findings further supported by a recent systematic review [ 33 ] which framed trust as a key tenet to just culture in hospital settings, and achievable through strategies that address organizational and team factors (e.g. management support and commitment, transparent incident reporting, close supervisory relationships, discussion of the nature of errors) and staff experience (e.g. clinical skill confidence, knowledge of reporting systems) [ 33 ]. Mirroring related literature, restorative approaches are scaffolded by adequate resourcing [ 31 ] and accreditation processes within a ‘quality-of-care (accreditation, inspection and public reporting)’ [ 34 ] paradigm. In this way, data-driven solutions can be formulated to ‘close the loop’ and facilitate sustained learning, implementation, and evaluation of patient safety initiatives [ 35 , 36 ].

With respect to the ‘layer’ reflecting the healthcare workforce, healthcare professionals are often the ‘second victims’ of patient safety incidents, with many personally traumatized and professionally (e.g. blamed) as a result [ 37 ]. Continuing the focus on the need for continued efforts to support a culture of safety, the theme of supporting staff in nonpunitive pro-learning environments has been reported in the literature and can assist their wellbeing and motivate reflective practice and behavioural change [ 37–39 ]. Support resources for those affected by patient safety incidents aim to provide psychological first aid, foster coping strategies, and promote individual resilience [ 40 ]. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s framework for respectful management of serious clinical adverse events [ 27 ] addresses the second victim phenomenon and has been adopted within national-level patient safety responses [ 41 ].

At the core of health care is the ‘layer’ that represents those that receive care and are consumers of our health services, and again, this was a clear theme within the findings of this study. There is increasing global momentum in promoting the patient voice in patient safety initiatives [ 42 ]. Recent systematic review evidence supports the benefits of patient engagement when developing health services and policy, resulting in positive health outcomes (e.g. reduced neonatal mortality) and the identification of broader healthcare priorities (e.g. environmental, educational, employment conditions) [ 43 ]. In support of our findings, barriers to patient safety engagement are currently based on an unwillingness to participate from patients (e.g. fear of reprisals, health literacy) and healthcare professionals (e.g. potential legal ramifications, attitude/knowledge limitations), coupled with organizational constraints (e.g. power-dynamic cultures, limited resourcing) [ 43 ]. Based on available evidence [ 44 ], future engagement approaches should be proactive and employ collaborative patient-professional partnerships, user-friendly patient safety feedback systems (e.g. succinct, plain language, integrated with documentation systems), and strategies to empower patients and improve confidence and seek organizational sponsorship (e.g. transparent value-based culture, staff consistency/training, whole of agency support).

Implications for policy, practice, and research

Policymakers can use our findings to identify and target current gaps in patient safety directives with national and international improvement initiatives that are tailored to a country’s own stage of evolution. These include accreditation processes, consistent and continuous undergraduate and postgraduate education, data reporting systems and infrastructure for benchmarking, and the establishment of clinical collaboratives for shared learnings and work towards national and international priorities. Study themes could inform further explorations of key factors for effective patient safety governance via implementation mechanistic and logic modelling [ 45 ], with findings used to design and pilot test interventional approaches across healthcare organizations and settings to explore outcomes and the relative cost-effectiveness in varying contexts.

Exploring the perspectives of international experts towards patient safety governance revealed aspects that provide value in improving patient outcomes. The quality and sustainability of patient safety governance relies on a strong safety culture in healthcare organizations, national policies and regulatory standards, continuing education for staff, and meaningful patient engagement approaches. The proposed ‘patient safety governance model’ provides policymakers and researchers with a framework to develop data-driven policy and initiatives.

Supplementary Material

Mzad088_supp, acknowledgements.

Funding for this research was provided by a grant from the Australian Patient Safety Foundation. The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of the International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) and the participants who contributed their valuable time and expertise.

Contributor Information

Peter D Hibbert, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences, Macquarie University, 75 Talavera Rd, Macquarie Park, NSW 2109, Australia. IIMPACT in Health, Allied Health and Human Performance, University of South Australia, GPO Box 2471, Adelaide SA 5001, Australia.

Sasha Stewart, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences, Macquarie University, 75 Talavera Rd, Macquarie Park, NSW 2109, Australia.

Louise K Wiles, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences, Macquarie University, 75 Talavera Rd, Macquarie Park, NSW 2109, Australia. IIMPACT in Health, Allied Health and Human Performance, University of South Australia, GPO Box 2471, Adelaide SA 5001, Australia.

Jeffrey Braithwaite, Australian Institute of Health Innovation, Faculty of Medicine, Health and Human Sciences, Macquarie University, 75 Talavera Rd, Macquarie Park, NSW 2109, Australia.

William B Runciman, IIMPACT in Health, Allied Health and Human Performance, University of South Australia, GPO Box 2471, Adelaide SA 5001, Australia.

Matthew J W Thomas, Appleton Institute, School of Health, Medical and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, 114-190 Canning Street, Rockhampton, Queensland 4700, Australia.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data is available at INTQHC online.

SS and LKW received University of South Australia funding with a grant from the Australian Patient Safety Foundation.

Data availability statement

Contributorship.

P.H., M.T., S.S., and W.B.R. designed the study. P.H. and S.S. conducted the interviews, S.S. and L.K.W. analysed the interview data, and P.H., M.T., and W.B.R. contributed to interpretation of interview data. All authors contributed to writing of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics and other permissions

All participants provided written informed consent prior to participating in the study. The study received Human Research Ethics Committee approval by the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee (203 467).

ASHRM President O’Sullivan’s March Message

We thrive together at ashrm.

Emerging Roles of Risk Managers in Senior Living and Skilled Nursing

Handling Disagreements Between Telehealth Critical Care and Bedside Providers

Strategies for Communication and Apology are Critical for Front-line Staff

Risk Professionals Ideal to Lead Health Care ESG Journey

- Uncategorized

Case Studies in Patient Safety

- Google Plus

Storytelling has been key to learning since the beginning of humankind. Case studies are a form of storytelling that often includes learning objectives, reflection and analysis. This book by Julie K. Johnson, Helen W. Haskell and Paul R. Barach uses storytelling to explore medical cases from the viewpoints of surviving family members. The amount of effort to collect such stories must have been astounding, but the reader benefits in incalculable ways.

The book’s stories illuminate how the industry might move from a clinician-centered system of care to a patient and family-centered system of care. The authors refer to Paul Batalden’s quote, “Every system is perfectly designed to get the results it gets.” For example, the results of the current medical educations system are knowledgeable diagnosticians who are focused on the individual physician-patient dyad. The authors examined 153 competencies across disciplines internationally that seem to correlate with good outcomes. The book’s stories are organized by these competencies:

- Medical knowledge, patient care

- Professionalism

- Interpersonal/communication skills

- Practice-based learning and improvement

- System-based practice

- Interprofessional collaboration

- Personal and professional development

One sees where professionalism and interpersonal/communication skills are greater important deficits for the families than knowledge or patient care aspects. This sets up the challenge for the reader, as the authors promote, to think differently about how to emotionally and intellectually engage patients and providers in healthcare transformation.

Discussed are 24 cases resulting from in- and out-patient settings in locations throughout the English-speaking world. One poignant case concerned a routine endoscopic procedure, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Post discharge, the patient began regurgitating, perspiring and was in pain. A telephone call to the office nurse resulted in a Tylenol suggestion. Then the physician called and suggested soup. A family member demanded a direct admission. The patient arrived at the emergency room with no forwarding message from the physician so she waited 12 hours for pain meds, but a full workup was achieved. The physician was not returning any emergency room calls as it was after 5 p.m. and the covering colleague said “not my patient.” As the patient deteriorated, a catheter was inserted. Then she was moved to the ICU and then to CCU. Diagnosis: sepsis. No record was ever found for the catheter order nor the ICU or CCU admissions. By now hospital specialists were attending to the patient with no sign of the original surgeon. The first code blue was noted.

With pneumonia and sepsis prevailing, staff placed a ventilator. Physicians mentioned pancreatitis after ERCP. They said it was not uncommon and the patient should recover. Eleven days later the patient had a cardiac arrest and coded. There were conflicting stories whether this occurred during a bath or during some suctioning. The code was unsuccessful. The family was not called by nursing per the protocol.

The CEO called the family back about a month after the death. New management had taken over the hospital. The CEO was trying to set a meeting with the family and physician, but the physician refused. After a year from the death, the physician accepted a meeting. Evidently, he felt comfortable because the family had not requested an autopsy so there was no way to prove whether the surgeon should have done the procedure in the first place or if he had done it wrong. The family regrets the omission of the autopsy because they saw there was no redress possible without it. After a complaint, the state medical board saw no wrong doing on the part of the surgeon. The state’s health services department did cite the emergency room for the lack of care of the patient.

The family felt abandoned by the surgeon, wrote a book about the event and discovered that adverse events were not nearly as common as they were led to believe. The book reviews further insight and notes ERCP is now widely overused.

In conclusion, this book presents poignant case studies that prompt one to think about various sides of stories and how systems, cultures and technical skills intertwine to affect life and death. One sees how the lack of communication can trump all of the aforementioned items to create a disaster. However, the reader is not left depressed, but instead inspired by the people sharing their stories and by the subsequent critical thinking that can occur after reading them.

Johnson, J., Haskell, H., & Barach, P. (2016) Case Studies in Patient Safety. Subury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning

You may also like

Building a High-Reliability Organization: A Toolkit for Success

ASHRM Whitepaper – Telemedicine: Risk Management Considerations

Stronger: Develop the Resilience You Need to Succeed

Sign up for ashrm forum updates.

Provide your information below to subscribe to ASHRM email communications

ASHRM Forum

- Submit an Article

Recent Articles

- ASHRM President O’Sullivan’s March Message March 20, 2024

- We thrive together at ASHRM January 10, 2024

- Emerging Roles of Risk Managers in Senior Living and Skilled Nursing October 16, 2023

- Handling Disagreements Between Telehealth Critical Care and Bedside Providers September 12, 2023

- Strategies for Communication and Apology are Critical for Front-line Staff September 7, 2023

- January 2024

- October 2023

- September 2023

- November 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- December 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- November 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- February 2017

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- ASHRM Academy

- ASHRM President Message

- ASHRM Updates

- Behavioral Health

- Book Review

- Emergency Preparedness

- Enterprise Risk Management (ERM

- Human Capital

- Legal & Regulatory

- Letter from the Chair

- Member Profile

- Operational

- Patient Safety/Clinical Care

- Sustainibility

- Angela Lucas, MSN, BSN, RN, CCRN-K

- Anne Huben-Kearney, RN, BSN, MPA, CPHRM, CPHQ, CPPS, DFASHRM

- Arlene Luu, RN, BSN, JD, CPHRM

- Barbara McCarthy RN, MPH, CIC, CPHQ, CPHRM, FASHRM

- Benedict Hane

- Chad Follmer, ARM, MBA

- Dan Corcoran

- Dan Groszkruger, JD, MPH, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Deborah Lessard CPHRM, FASHRM, MS and Leigh Ann Yates, AIC, MBA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Deborah Lessard, Esq., RN, JD, MA, BSN, CPHRM, FASHRM

- Denise Shope, RN, MHSA, ARM, CPHRM, DFASHRM and Nancy Connelly, RN, BA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Denise Winiarski JD, CPHRM Emily Klatt, JD Amir Kazerouninia, MD, PhD

- Ferdinando L. Mirarchi, DO, FAAEM, FACEP

- Forum Task Force Chair Leigh Ann Yates, AIC, MBA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Franchesca J. Charney, RN, MS, CPHRM, CPPS, CPSO, DFASHRM and Guy Whittall-Scherfee, MS

- Heidi Harrison, CPHRM

- Jessica J. Ayd, Esq.; Sherri Hobbs, MSM, MSN, RN, CPHQ; Heather Joyce-Byers, MSJ, BS, RN, CCRN-K, CPHRM; Shannon M. Madden, Esq.

- Joan Porcaro, RN, BSN, MM, CPHRM

- John C. West, JD, MHA, DFASHRM, CPHRM,

- John D. Banja, PhD

- Julie Radford, JD, CPHRM

- Karen Garvey, DFASHRM, CPHRM, and CPPS

- Karen Wright RN, BSN, ARM, CPHRM

- Kathleen Shostek, RN ARM FASHRM CPHRM CPPS

- Kenita Hill, MSA, CPHRM, LNHA, LPN

- Larry Veltman, MD, FACOG, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Leigh Ann Yates and Stephanie Nadasi

- Leigh Ann Yates, MBA, CPHRM, AIC, DFASHRM

- Mackenzie C. Monaco

- Maggie Neustadt, JD CPHRM, FASHRM

- Margaret Curtin, MPA, HCA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Mark Dame, MHA, CPHRM, FACHE

- Melanie Osley and Holly Taylor

- Melanie Osley, RN, MBA, CPHRM, CPHQ, CPPS, ARM, DFASHRM

- Melanie Taylor, Esq.

- Melinda Van Niel, BA, MBA and Doug Wojcieszak, MA, MS, BS

- Michael G. Lloyd, MBA, CPCU, ARM, CPHRM

- Monica Cooke BSN, MA, RNC, CPHQ, CPHRM, FASHRM

- Nancy Connelly, RN, BA, CPHRM, DFASHRM

- Nancy Connelly, RN, BA, CPHRM, DFASHRM and Kenita Hill, MSA, CPHRM, LNHA, LPN

- Paula Caballero

- Rhonda DeMeno, RN, MS,MPM, BSHRM, CBIC, CPHRM and Joan Porcaro, RN, BSN, MM, CPHRM

- Rita Barrett-Cosby, CPHRM

- Robin Diamond

- Ryan Solomon, JD

- Sarah B. Roberts, MPH, CHES, CPHQ, CPHRM, ARM, AIS, AINS

- Scripps La Jolla Memorial Quality Team Memorial Quality Team

- Steven D. Weiner and Mario Giannettino

- Sue Boisvert, BSN, MHSA, CPHRM, FASHRM

- Susan Lucot, MSN RN

- Suzanne Natbony

- Tatum O’Sullivan, RN, BSN, MHSA, CPHRM, DFASHRM, CPPS

- Tricia Brooks-Phillips, MSN, RN, CPHRM

- Vallerie H. Propper, JD, MPH

- Vicki J. Missar

- Log In / Register

- Education Platform

- Newsletter Sign Up

Case Studies

- How to Improve

- Improvement Stories

- Publications

- IHI White Papers

- Audio and Video

Case studies related to improving health care.

first < > last

- An Extended Stay A 64-year-old man with a number of health issues comes to the hospital because he is having trouble breathing. The care team helps resolve the issue, but forgets a standard treatment that causes unnecessary harm to the patient. A subsequent medication error makes the situation worse, leading a stay that is much longer than anticipated.

- Mutiny The behavior of a superior starts to put your patients at risk. What would you do? The University of Rochester’s Dr. Paul Griner presents the final installment in a series of case studies for the IHI Open School.

- On Being Transparent You are the CEO and a patient in your hospital dies from a medication error. What do you do next? The University of Rochester’s Dr. Paul Griner presents the fourth in a series of case studies.

- Locked In A cancer diagnosis leads to tears and heartache. But is it correct? Dr. Paul Griner, Professor Emeritus of Medicine at the University of Rochester, presents the third in a series of case studies for the IHI Open School.

- Confidentiality and Air Force One A difficult patient. A difficult decision. The University of Rochester’s Dr. Paul Griner presents the second in a series of case studies.

- The Protective Parent During a 50-year career in medicine, Dr. Paul Griner accumulated hundreds of patient stories. Most of his stories – including this case study "The Protective Parent" - are from the 1950s and 1960s, prior to what we now refer to as “modern medicine.”

- Advanced Case Study Between Sept. 30th and Oct. 14th, 2010, students and residents all over the world gathered in interprofessional teams and analyzed a complex incident that resulted in patient harm. Selected teams presented their work to IHI faculty during a series of live webinars in October.

- A Downward Spiral: A Case Study in Homelessness Thirty-six-year-old John may not fit the stereotype of a homeless person. Not long ago, he was living what many would consider a healthy life with his family. But when he lost his job, he found himself in a downward spiral, and his situation dramatically changed. John’s story is a fictional composite of real patients treated by Health Care for the Homeless. It illustrates the challenges homeless people face in accessing health care and the characteristics of high-quality care that can improve their lives.

- What Happened to Alex? Alex James was a runner, like his dad. One day, he collapsed during a run and was hospitalized for five days. He went through lots of tests, but was given a clean bill of health. Then, a month later, he collapsed again, fell into a deep coma, and died. His father wanted to know — what had gone wrong? Dr. John James, a retired toxicologist at NASA, tells the story of how he uncovered the cause of his son’s death and became a patient safety advocate.

- Improving Care in Rural Rwanda When Dr. Patrick Lee and his teammates began their quality improvement work in Kirehe, Rwanda, last year, the staff at the local hospital was taking vital signs properly less than half the time. Today, the staff does that task properly 95% of the time. Substantial resource and infrastructure inputs, combined with dedicated Rwandan partners and simple quality improvement tools, have dramatically improved staff morale and the quality of care in Kirehe.

An official website of the Department of Health and Human Services

Browse Topics

Priority populations.

- Children/Adolescents

- Racial/Ethnic Minorities

- Rural/Inner-City Residents

- Special Healthcare Needs

- Clinicians & Providers

- Data & Measures

- Digital Healthcare Research

- Education & Training

- Hospitals & Health Systems

- Prevention & Chronic Care

- Quality & Patient Safety

- Publications & Products

- AHRQ Publishing and Communications Guidelines

- Search Publications

Research Findings & Reports

- Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) Reports

- Fact Sheets

- Grantee Final Reports: Patient Safety

- Making Healthcare Safer Report

- National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Reports

- Technology Assessment Program

- AHRQ Research Studies

National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report

Latest available findings on quality of and access to health care

- Data Infographics

- Data Visualizations

- Data Innovations

- All-Payer Claims Database

- Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP)

- Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS)

- AHRQ Quality Indicator Tools for Data Analytics

- State Snapshots

- United States Health Information Knowledgebase (USHIK)

- Data Sources Available from AHRQ

Funding & Grants

Notice of funding opportunities, research policies.

- Notice of Funding Opportunity Guidance

- AHRQ Grants Policy Notices

- AHRQ Informed Consent & Authorization Toolkit for Minimal Risk Research

- HHS Grants Policy Statement

- Federal Regulations & Authorities

- Federal Register Notices

- AHRQ Public Access Policy

- Protection of Human Subjects

Funding Priorities

- Special Emphasis Notices

- Staff Contacts

Training & Education Funding

Grant application, review & award process.

- Grant Application Basics

- Application Forms

- Application Deadlines & Important Dates

- AHRQ Tips for Grant Applicants

- Grant Mechanisms & Descriptions

- Application Receipt & Review

- Study Sections for Scientific Peer Review

- Award Process

Post-Award Grant Management

- AHRQ Grantee Profiles

- Getting Recognition for Your AHRQ-Funded Study

- Grants by State

- No-Cost Extensions (NCEs)

AHRQ Grants by State

Searchable database of AHRQ Grants

AHRQ Projects funded by the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Trust Fund.

- Press Releases

- AHRQ Social Media

- Impact Case Studies

- AHRQ News Now

- AHRQ Research Summit on Diagnostic Safety

- AHRQ Research Summit on Learning Health Systems

- National Advisory Council Meetings

- AHRQ Research Conferences

- AHRQ's 35th Anniversary

- Mission and Budget

- AHRQ's Core Competencies

- National Advisory Council

- Careers at AHRQ

- Maps and Directions

- Other AHRQ Web Sites

- Other HHS Agencies

- Testimonials

Organization & Contacts

- Centers and Offices

- Organization Chart

- Key Contacts

- Evidence-based Practice Center Reports

- National Healthcare Quality & Disparities Reports

- Making Health Care Safer II

- Making Healthcare Safer III

Making Healthcare Safer IV

- Making Health Care Safer

- Making Healthcare Safer Comparison

A Continuous Updating of Patient Safety Harms and Practices

Making Healthcare Safer reports I, II, and III have shown a positive impact of patient safety practices on the reduction of medical errors. However, threats to patient safety are still emerging and evolving in a dynamic world.

Patient safety research is growing, spanning across more healthcare settings, and considers a wide array of contextual factors. The combination of emerging patient safety threats and the growing amount of published patient safety research, patient safety resources, and accrediting body standards makes it increasingly difficult to prioritize adoption and implementation of evidence-based practices. AHRQ’s fourth iteration of Making Healthcare Safer intends to address this issue by publishing evidence-based reviews of patient safety practices and topics as they are completed. This intentional release of updated reviews will aid healthcare organization leaders in prioritizing implementation of evidence-based practices in a timelier way. The report also will help researchers identify where more research is needed in a timelier way and assist policymakers in understanding which patient safety practices have the supporting evidence for promotion. Reviews will be posted below as they are completed.

Making Healthcare Safer IV was commissioned in 2022. To kick off the report, AHRQ explored the potential harms that may be associated with telehealth, which has grown exponentially during the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic to facilitate healthcare during a time when in-person clinical encounters between a patient and clinician was significantly reduced to help slow the spread of the virus. Because the benefits of telehealth became evident during the pandemic, the harms and patient safety practices to reduce the risk for medical errors, misdiagnosis, and privacy concerns are still being assessed. This review will serve as a baseline for the evidence of harms and patient safety practices to prevent or mitigate harms associated with the use of telehealth.

Making Healthcare Safer IV began with a horizon scan to identify emerging trends and needs in the patient safety field. A technical expert panel (TEP) was convened to prioritize which topics and patient safety practices, including updates to the ones covered in the previous Making Healthcare Safer reports, would be most beneficial to the field if addressed throughout the years of the fourth report. These discussions are summarized in the Prioritization Report .

AHRQ determined that the first rapid review would be on the potential harms that may be associated with telehealth, which has grown exponentially during the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic to facilitate healthcare during a time when in-person clinical encounters between a patient and clinician was significantly reduced to help slow the spread of the virus. Because the benefits of telehealth became evident during the pandemic, the harms and patient safety practices to reduce the risk for medical errors, misdiagnosis, and privacy concerns are still being assessed. This review will serve as a baseline for the evidence of harms and patient safety practices to prevent or mitigate harms associated with the use of telehealth. Since AHRQ asked for this topic to be explored first, it was not discussed during the TEP convening.

The first three Making Healthcare Safer reports, published in 2001 , 2013 , and 2020 , have each served as a consolidated source of information for healthcare providers, health system administrators, researchers, and government agencies. A set of tables compares the patient safety practices among the reports.

Prioritization of Patient Safety Practices for Making Healthcare Safer IV

Potential Harms Resulting From Video-Based Telehealth

Patient and Family Engagement

Surgical Report Cards and Outcome Measurements

Opioid Stewardship

Reducing Adverse Events Related to Anticoagulants

Implicit Bias Training

Deprescribing

Computerized Clinical Decision Support To Prevent Medication Errors and Adverse Drug Events

Failure To Rescue—Rapid Response Systems

Transmission-Based Precautions for Multidrug-Resistant Organisms

Sepsis Prediction, Recognition, and Intervention

Engaging Family Caregivers

Fatigue and Sleepiness of Clinicians Due to Hours of Service

Infection Surveillance for Clostridiodes difficile , Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales (CRE), and Candida auris

Internet Citation: Making Healthcare Safer IV. Content last reviewed April 2024. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/making-healthcare-safer/mhs4/index.html

Nursing Case Study Jessica’s Suicide

This essay about a nursing case study investigates the tragic suicide of Jessica, a young patient with a history of severe depression and anxiety. It critically examines the factors contributing to her death, emphasizing the need for vigilant mental health care and responsive adjustments in treatment based on a patient’s changing emotional state. The analysis points out failures in communication within the healthcare team and inadequate family involvement, suggesting that better informed support networks could prevent similar crises. The essay advocates for integrated care approaches, including psychological, psychiatric, and social support, to enhance patient-centered care and potentially save lives. This reflective analysis underscores the importance of training and awareness in healthcare settings to better manage and support patients experiencing mental health challenges.

How it works

Suicide is a critical public health issue that necessitates comprehensive understanding and sensitive intervention, particularly within the healthcare setting. This analysis delves into a poignant nursing case study centered around Jessica, a young patient who tragically ended her life. By examining Jessica’s case, we aim to shed light on the complex interplay of mental health challenges and the healthcare strategies that could potentially mitigate such devastating outcomes.

Jessica, a 24-year-old female, had been battling severe depression and anxiety for several years.

Her medical history reveals multiple previous attempts at suicide, each coinciding with periods of extreme emotional distress. Jessica’s situation underscores a critical aspect of mental health care: the necessity for vigilant, ongoing assessments and interventions tailored to individual patient histories and circumstances.

Upon her last admission to the hospital, Jessica appeared particularly withdrawn and despondent. Nursing notes indicated that she expressed feelings of hopelessness and a decreased interest in engaging with both staff and her own family members. Despite these clear warning signs, the response from the healthcare team was not sufficiently tailored to her acute need for intensive psychological support. This case points to the first significant lesson: the importance of responsive care adjustments based on a patient’s evolving emotional and psychological state.

One pivotal factor in Jessica’s care was the communication between her nurses and the broader psychiatric team. Effective communication in healthcare settings is crucial and can often be the deciding factor in preventing a crisis. For Jessica, the lapse in conveying critical information about her worsening depressive state and potential suicidal ideation might have contributed to the lack of timely interventions. Therefore, enhancing communication protocols within hospital settings could serve as a preventive measure, ensuring that all team members are aware of a patient’s current mental health status and are acting accordingly.

Additionally, Jessica’s case highlights the role of family involvement in managing mental health crises. It appears that her family was not fully aware of the gravity of her condition nor the potential for imminent risk. Increasing family engagement and education about mental health conditions could bridge this gap, providing a support system that is more attuned and responsive to the patient’s needs.

In addressing these issues, healthcare providers can learn from Jessica’s case to better manage similar situations. Implementing routine and more detailed psychological evaluations can help identify at-risk individuals before a crisis occurs. Training for nursing staff in recognizing the subtleties of mental health deterioration and the importance of assertive communication can also be crucial.

Furthermore, integrating multidisciplinary approaches that include psychological, psychiatric, and social support can create a more holistic care model. Such integration ensures that patients like Jessica receive not only medical treatment but also comprehensive psychosocial support, potentially alleviating the sense of isolation and despair that can lead to suicide.

Finally, healthcare institutions must foster an environment where mental health care is prioritized and where all staff members are equipped with the necessary tools and training to effectively intervene. This requires ongoing education and awareness programs that emphasize the complexities of mental health issues and the critical role of tailored, patient-centered care.

Jessica’s tragic outcome serves as a somber reminder of what might happen when systemic and individual care components fail to adequately align with the needs of those at risk. Through this case study, we learn the invaluable lessons of vigilance, communication, and an integrated approach to mental health within the nursing profession. It is only through such committed efforts that we can hope to prevent such losses in the future and better support our patients through their most challenging times.

Cite this page

Nursing Case Study Jessica's Suicide. (2024, Apr 14). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/nursing-case-study-jessicas-suicide/

"Nursing Case Study Jessica's Suicide." PapersOwl.com , 14 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/nursing-case-study-jessicas-suicide/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Nursing Case Study Jessica's Suicide . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/nursing-case-study-jessicas-suicide/ [Accessed: 14 Apr. 2024]

"Nursing Case Study Jessica's Suicide." PapersOwl.com, Apr 14, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/nursing-case-study-jessicas-suicide/

"Nursing Case Study Jessica's Suicide," PapersOwl.com , 14-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/nursing-case-study-jessicas-suicide/. [Accessed: 14-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Nursing Case Study Jessica's Suicide . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/nursing-case-study-jessicas-suicide/ [Accessed: 14-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

An official website of the Department of Health & Human Services

- Search All AHRQ Sites

- Email Updates

1. Use quotes to search for an exact match of a phrase.

2. Put a minus sign just before words you don't want.

3. Enter any important keywords in any order to find entries where all these terms appear.

- The PSNet Collection

- All Content

- Perspectives

- Current Weekly Issue

- Past Weekly Issues

- Curated Libraries

- Clinical Areas

- Patient Safety 101

- The Fundamentals

- Training and Education

- Continuing Education

- WebM&M: Case Studies

- Training Catalog

- Submit a Case

- Improvement Resources

- Innovations

- Submit an Innovation

- About PSNet

- Editorial Team

- Technical Expert Panel

Book/Report

Patient Safety: A Case-based Innovative Playbook for Safer Care. Second Edition.

Agrawal A, Bhatt J, eds. Cham, Switzerland, Springer Nature; 2023. ISBN: 9783031359330.

This publication describes and analyzes clinical cases to illustrate patient safety concepts and types of medical errors to engage clinicians in improvement work. The second edition includes chapters devoted to safety challenges that emerged in prominence due to the COVID-19 pandemic (health disparities, inequities and nursing home care failures), as well as core topics such as high reliability, human factors engineering and the opioid epidemic.

Advances in Human Factors and Ergonomics in Healthcare and Medical Devices. September 11, 2019

Error Reduction and Prevention in Surgical Pathology, Second Edition. August 28, 2019

Cognitive Errors and Diagnostic Mistakes: A Case-Based Guide to Critical Thinking in Medicine. July 10, 2019

Mistakes, Errors and Failures across Cultures. April 15, 2020

Diagnoses Without Names: Challenges for Medical Care, Research, and Policy. October 12, 2022

Textbook of Patient Safety and Clinical Risk Management. January 20, 2021

Clinical Uncertainty in Primary Care: The Challenge of Collaborative Engagement. March 5, 2014

Cognitive Informatics: Reengineering Clinical Workflow for Safer and More Efficient Care. August 21, 2019

Occupational Health and Organizational Culture within a Healthcare Setting: Challenges, Complexities, and Dynamics. January 17, 2024

Decision Making in Emergency Medicine: Biases, Errors and Solutions. June 30, 2021

Global Burden of Preventable Medication-related Harm in Health Care: A Systematic Review. March 20, 2024

New evidence on stemming low-value prescribing. May 1, 2019

Making Healthcare Safe: The Story of the Patient Safety Movement. June 9, 2021