Write a University Essay

What are the parts of an essay, how do i write an introduction, how do i write the body of my essay, how do i write the conclusion, how do i create a reference list, how do i improve my essay.

- Improving your writing

Ask Us: Chat, email, visit or call

More help: Writing

- Book Writing Appointments Get help on your writing assignments.

- Introduction

- Each is made up of one or several paragraphs.

- The purpose of this section is to introduce the topic and why it matters, identify the specific focus of the paper, and indicate how the paper will be organized.

- To keep from being too broad or vague, try to incorporate a keyword from your title in the first sentence.

- For example, you might tell readers that the issue is part of an important debate or provide a statistic explaining how many people are affected.

- Defining your terms is particularly important if there are several possible meanings or interpretations of the term.

- Try to frame this as a statement of your focus. This is also known as a purpose statement, thesis argument, or hypothesis.

- The purpose of this section is to provide information and arguments that follow logically from the main point you identified in your introduction.

- Identify the main ideas that support and develop your paper’s main point.

- For longer essays, you may be required to use subheadings to label your sections.

- Point: Provide a topic sentence that identifies the topic of the paragraph.

- Proof: Give evidence or examples that develop and explain the topic (e.g., these may come from your sources).

- Significance: Conclude the paragraph with sentence that tells the reader how your paragraph supports the main point of your essay.

- The purpose of this section is to summarize the main points of the essay and identify the broader significance of the topic or issue.

- Remind the reader of the main point of your essay (without restating it word-for-word).

- Summarize the key ideas that supported your main point. (Note: No new information or evidence should be introduced in the conclusion.)

- Suggest next steps, future research, or recommendations.

- Answer the question “Why should readers care?” (implications, significance).

- Find out what style guide you are required to follow (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago) and follow the guidelines to create a reference list (may be called a bibliography or works cited).

- Be sure to include citations in the text when you refer to sources within your essay.

- Cite Your Sources - University of Guelph

- Read assignment instructions carefully and refer to them throughout the writing process.

- e.g., describe, evaluate, analyze, explain, argue, trace, outline, synthesize, compare, contrast, critique.

- For longer essays, you may find it helpful to work on a section at a time, approaching each section as a “mini-essay.”

- Make sure every paragraph, example, and sentence directly supports your main point.

- Aim for 5-8 sentences or ¾ page.

- Visit your instructor or TA during office hours to talk about your approach to the assignment.

- Leave yourself time to revise your essay before submitting.

- << Previous: Start Here

- Next: Improving your writing >>

- Last Updated: Oct 27, 2022 10:28 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uoguelph.ca/UniversityEssays

Suggest an edit to this guide

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

How to Write an Essay/Parts

Parts of an Essay — Traditionally, it has been taught that a formal essay consists of three parts: the introductory paragraph or introduction, the body paragraphs, and the concluding paragraph. An essay does not need to be this simple, but it is a good starting point.

Introductory Paragraph [ edit | edit source ]

The introductory paragraph accomplishes three purposes: it captures the reader’s interest, it suggests the importance of the essay’s topic, and it ends with a thesis sentence. Often, the thesis sentence states a claim that consists of two or more related points. For example, a thesis might read:

You are telling the reader what you think are the most important points which need to be addressed in your essay. For this reason, you need to relate the introduction directly to the question or topic. A strong thesis is essential to a good essay, as each paragraph of your essay should be related back to your thesis or else deleted. Thus, the thesis establishes the key foundation for your essay. A strong thesis not only states an idea but also uses solid examples to back it up. A weak thesis might be:

As an alternative, a strong thesis for the same topic would be:

Then, you could separate your body paragraphs into three sections: one explaining the open-source nature of the project, one explaining the variety and depth of information, and a final one using studies to confirm that Wikipedia is indeed as accurate as other encyclopedias.

Tips [ edit | edit source ]

Often, writing an introductory paragraph is the most difficult part of writing an essay. Facing a blank page can be daunting. Here are some suggestions for getting started. First, determine the context in which you want to place your topic. In other words, identify an overarching category in which you would place your topic, and then introduce your topic as a case-in-point.

For example, if you are writing about dogs, you may begin by speaking about friends, dogs being an example of a very good friend. Alternatively, you can begin with a sentence on selective breeding, dogs being an example of extensive selective breeding. You can also begin with a sentence on means of protection, dogs being an example of a good way to stay safe. The context is the starting point for your introductory paragraph. The topic or thesis sentence is the ending point. Once the starting point and ending point are determined, it will be much easier to connect these points with the narrative of the opening paragraph.

A good thesis statement, for example, if you are writing about dogs being very good friends, you could put:

Here, X, Y, and Z would be the topics explained in your body paragraphs. In the format of one such instance, X would be the topic of the second paragraph, Y would be the topic of the third paragraph, and Z would be the topic of the fourth paragraph, followed by a conclusion, in which you would summarize the thesis statement.

Example [ edit | edit source ]

Identifying a context can help shape the topic or thesis. Here, the writer decided to write about dogs. Then, the writer selected friends as the context, dogs being good examples of friends. This shaped the topic and narrowed the focus to dogs as friends . This would make writing the remainder of the essay much easier because it allows the writer to focus on aspects of dogs that make them good friends.

Body Paragraphs [ edit | edit source ]

Each body paragraph begins with a topic sentence. If the thesis contains multiple points or assertions, each body paragraph should support or justify them, preferably in the order the assertions originally stated in the thesis. Thus, the topic sentence for the first body paragraph will refer to the first point in the thesis sentence and the topic sentence for the second body paragraph will refer to the second point in the thesis sentence. Generally, if the thesis sentence contains three related points, there should be three body paragraphs, though you should base the number of paragraphs on the number of supporting points needed.

If the core topic of the essay is the format of college essays, the thesis sentence might read:

The topic sentence for the first body paragraph might read:

Sequentially, the topic sentence for the second body paragraph might read:

And the topic sentence for the third body paragraph might read:

Every body paragraph uses specific details, such as anecdotes, comparisons and contrasts, definitions, examples, expert opinions, explanations, facts, and statistics to support and develop the claim that its topic sentence makes.

When writing an essay for a class assignment, make sure to follow your teacher or professor’s suggestions. Most teachers will reward creativity and thoughtful organization over dogmatic adherence to a prescribed structure. Many will not. If you are not sure how your teacher will respond to a specific structure, ask.

Organizing your essay around the thesis sentence should begin with arranging the supporting elements to justify the assertion put forth in the thesis sentence. Not all thesis sentences will, or should, lay out each of the points you will cover in your essay. In the example introductory paragraph on dogs, the thesis sentence reads, “There is no friend truer than a dog.” Here, it is the task of the body paragraphs to justify or prove the truth of this assertion, as the writer did not specify what points they would cover. The writer may next ask what characteristics dogs have that make them true friends. Each characteristic may be the topic of a body paragraph. Loyalty, companionship, protection, and assistance are all terms that the writer could apply to dogs as friends. Note that if the writer puts dogs in a different context, for example, working dogs, the thesis might be different, and they would be focusing on other aspects of dogs.

It is often effective to end a body paragraph with a sentence that rationalizes its presence in the essay. Ending a body paragraph without some sense of closure may cause the thought to sound incomplete.

Each body paragraph is something like a miniature essay in that they each need an introductory sentence that sounds important and interesting, and that they each need a good closing sentence in order to produce a smooth transition between one point and the next. Body paragraphs can be long or short. It depends on the idea you want to develop in your paragraph. Depending on the specific style of the essay, you may be able to use very short paragraphs to signal a change of subject or to explain how the rest of the essay is organized.

Do not spend too long on any one point. Providing extensive background may interest some readers, but others would find it tiresome. Keep in mind that the main importance of an essay is to provide a basic background on a subject and, hopefully, to spark enough interest to induce further reading.

The above example is a bit free-flowing and the writer intended it to be persuasive. The second paragraph combines various attributes of dogs including protection and companionship. Here is when doing a little research can also help. Imagine how much more effective the last statement would be if the writer cited some specific statistics and backed them up with a reliable reference.

Concluding Paragraph [ edit | edit source ]

The concluding paragraph usually restates the thesis and leaves the reader something about the topic to think about. If appropriate, it may also issue a call to act, inviting the reader to take a specific course of action with regard to the points that the essay presented.

Aristotle suggested that speakers and, by extension, writers should tell their audience what they are going to say, say it, and then tell them what they have said. The three-part essay model, consisting of an introductory paragraph, several body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph, follows this strategy.

As with all writing, it is important to know your audience. All writing is persuasive, and if you write with your audience in mind, it will make your argument much more persuasive to that particular audience. When writing for a class assignment, the audience is your teacher. Depending on the assignment, the point of the essay may have nothing to do with the assigned topic. In most class assignments, the purpose is to persuade your teacher that you have a good grasp of grammar and spelling, that you can organize your thoughts in a comprehensive manner, and, perhaps, that you are capable of following instructions and adhering to some dogmatic formula the teacher regards as an essay. It is much easier to persuade your teacher that you have these capabilities if you can make your essay interesting to read at the same time. Place yourself in your teacher’s position and try to imagine reading one formulaic essay after another. If you want yours to stand out, capture your teacher’s attention and make your essay interesting, funny, or compelling.

In the above example, the focus shifted slightly and talked about dogs as members of the family. Many would suggest it departs from the logical organization of the rest of the essay, and some teachers may consider it unrelated and take points away. However, contrary to the common wisdom of “tell them what you are going to say, say it, and then tell them what you have said,” you may find it more interesting and persuasive to shift away from it as the writer did here, and then, in the end, return to the core point of the essay. This gives an additional effect to what an audience would otherwise consider a very boring conclusion.

- Book:How to Write an Essay

Navigation menu

Pasco-Hernando State College

- Parts of an Academic Essay

- The Writing Process

- Rhetorical Modes as Types of Essays

- Stylistic Considerations

- Literary Analysis Essay - Close Reading

- Unity and Coherence in Essays

- Proving the Thesis/Critical Thinking

- Appropriate Language

Test Yourself

- Essay Organization Quiz

- Sample Essay - Fairies

- Sample Essay - Modern Technology

In a way, these academic essays are like a court trial. The attorney, whether prosecuting the case or defending it, begins with an opening statement explaining the background and telling the jury what he or she intends to prove (the thesis statement). Then, the attorney presents witnesses for proof (the body of the paragraphs). Lastly, the attorney presents the closing argument (concluding paragraph).

The Introduction and Thesis

There are a variety of approaches regarding the content of the introduction paragraph such as a brief outline of the proof, an anecdote, explaining key ideas, and asking a question. In addition, some textbooks say that an introduction can be more than one paragraph. The placement of the thesis statement is another variable depending on the instructor and/or text. The approach used in this lesson is that an introduction paragraph gives background information leading into the thesis which is the main idea of the paper, which is stated at the end.

The background in the introductory paragraph consists of information about the circumstances of the thesis. This background information often starts in the introductory paragraph with a general statement which is then refined to the most specific sentence of the essay, the thesis. Background sentences include information about the topic and the controversy. It is important to note that in this approach, the proof for the thesis is not found in the introduction except, possibly, as part of a thesis statement which includes the key elements of the proof. Proof is presented and expanded on in the body.

Some instructors may prefer other types of content in the introduction in addition to the thesis. It is best to check with an instructor as to whether he or she has a preference for content. Generally, the thesis must be stated in the introduction.

The thesis is the position statement. It must contain a subject and a verb and express a complete thought. It must also be defensible. This means it should be an arguable point with which people could reasonably disagree. The more focused and narrow the thesis statement, the better a paper will generally be.

If you are given a question in the instructions for your paper, the thesis statement is a one-sentence answer taking a position on the question.

If you are given a topic instead of a question, then in order to create a thesis statement, you must narrow your analysis of the topic to a specific controversial issue about the topic to take a stand. If it is not a research paper, some brainstorming (jotting down what comes to mind on the issue) should help determine a specific question.

If it is a research paper, the process begins with exploratory research which should show the various issues and controversies which should lead to the specific question. Then, the research becomes focused on the question which in turn should lead to taking a position on the question.

These methods of determining a thesis are still answering a question. It’s just that you pose a question to answer for the thesis. Here is an example.

Suppose, one of the topics you are given to write about is America’s National Parks. Books have been written about this subject. In fact, books have been written just about a single park. As you are thinking about it, you may realize how there is an issue about balancing between preserving the wilderness and allowing visitors. The question would then be Should visitors to America’s National Parks be regulated in order to preserve the wilderness?

One thesis might be There is no need for regulations for visiting America’s National Parks to preserve the wilderness.

Another might be There should be reasonable regulations for visiting America’s National Parks in order to preserve the wilderness.

Finally, avoid using expressions that announce, “Now I will prove…” or “This essay is about …” Instead of telling the reader what the paper is about, a good paper simply proves the thesis in the body. Generally, you shouldn’t refer to your paper in your paper.

Here is an example of a good introduction with the thesis in red:

Not too long ago, everyday life was filled with burdensome, time-consuming chores that left little time for much more than completing these tasks. People generally worked from their homes or within walking distance to their homes and rarely traveled far from them. People were limited to whatever their physical capacities were. All this changed dramatically as new technologies developed. Modern technology has most improved our lives through convenience, efficiency, and accessibility.

Note how the background is general and leads up to the thesis. No proof is given in the background sentences about how technology has improved lives.

Moreover, notice that the thesis in red is the last sentence of the introduction. It is a defensible statement.

A reasonable person could argue the opposite position: Although modern technology has provided easier ways of completing some tasks, it has diminished the quality of life since people have to work too many hours to acquire these gadgets, have developed health problems as a result of excess use, and have lost focus on what is really valuable in life.

Quick Tips:

The introduction opens the essay and gives background information about the thesis.

Do not introduce your supporting points (proof) in the introduction unless they are part of the thesis; save these for the body.

The thesis is placed at the end of the introductory paragraph.

Don’t use expressions like “this paper will be about” or “I intend to show…”

For more information on body paragraphs and supporting evidence, see Proving a Thesis – Evidence and Proving a Thesis – Logic, and Logical Fallacies and Appeals in Related Pages on the right sidebar.

Body paragraphs give proof for the thesis. They should have one proof point per paragraph expressed in a topic sentence. The topic sentence is usually found at the beginning of each body paragraph and, like a thesis, must be a complete sentence. Each topic sentence must be directly related to and support the argument made by the thesis.

After the topic sentence, the rest of the paragraph should go on to support this one proof with examples and explanation. It is the details that support the topic sentences in the body paragraphs that make the arguments strong.

If the thesis statement stated that technology improved the quality of life, each body paragraph should begin with a reason why it has improved the quality of life. This reason is called a topic sentence . Following are three examples of body paragraphs that provide support for the thesis that modern technology has improved our lives through convenience, efficiency, and accessibility:

Almost every aspect of our lives has been improved through convenience provided by modern technology. From the sound of music from an alarm clock in the morning to the end of the day being entertained in the convenience of our living room, our lives are improved. The automatic coffee maker has the coffee ready at a certain time. Cars or public transportation bring people to work where computers operate at the push of a button. At home, there’s the convenience of washing machines and dryers, dishwashers, air conditioners, and power lawn mowers. Modern technology has made life better with many conveniences.

Not only has technology improved our lives through convenience, it has improved our lives through efficiency. The time saved by machines doing most of the work leaves more time for people to develop their personal goals or to just relax. Years ago, when doing laundry could take all day, there wasn’t time left over to read or go to school or even just to take a leisurely walk. Nowadays, people have more time and energy than ever to simply enjoy their lives and pursue their goals thanks to the efficiency of modern technology.

Accessibility to a wide range of options has been expanded through modern technology. Never before could people cross a continent or an ocean in an afternoon. Travel is not the only way technology has created accessibility. Software which types from voice commands has made using computers more accessible for school or work. People with special needs have many new options thanks to modern technology such as special chairs or text readers. Actually, those people who need hearing aids as a result of normal aging have access to continued communication and enjoyment of entertainment they did not previously have. There are many ways technology has improved lives through increased accessibility.

Notice how these proof paragraphs stick to one proof point introduced in the topic sentences in red. These three paragraphs, not only support the original thesis, but go on to give details and explanations which explain the proof point in the topic sentence.

Quick Tips on Body Paragraphs

The body of your essay is where you give your main support for the thesis.

Each body paragraph should start with a Topic Sentence that is directly related to and supports the thesis statement.

Each body paragraph should also give details and explanations that further support the poof point for that paragraph.

Don’t use enumeration such as first, second, and third. The reader will know by the topic sentence that it is a new proof point.

See Proving the Thesis in Related Pages on the right sidebar for more information on proof.

The Conclusion

Instructors vary of what they expect in the conclusion; however, there is general agreement that conclusions should not introduce any new proof points, should include a restatement of the thesis, and should not contain any words such as “In conclusion.”

Some instructors want only a summary of the proof and a restatement of the thesis. Some instructors ask for a general prediction or implication of the information presented without a restatement of thesis. Still others may want to include a restatement along with a general prediction or implication of the information presents. Be sure to review assignment instructions or check with instructor. If your assignment instructions don’t specify, just sum up the proof and restate the thesis.

Example which sums up proof and restates thesis :

Modern technology has created many conveniences in everyday from waking up to music to having coffee ready to getting to work and doing a day’s work. The efficiency provided by technology gives people more time to enjoy life and pursue personal development, and the accessibility has broadened options for travel, school, and work. Modern technology has improved our lives through convenience, efficiency, and accessibility.

See how the thesis statement was restated in red. The two major arguments about the possible locations proven to be incorrect were also included to remind the reader of the major proof points made in the paper.

Example which makes a general prediction or implication of the information presented:

Modern technology has created many conveniences in everyday life from waking up to music to having coffee ready to getting to work and doing a day’s work. The efficiency provided by technology gives people more time to enjoy life and pursue personal development, and the accessibility has broadened options for travel, school, and work. Without it, everyday life would be filled with burdensome tasks and be limited to our neighborhood and our physical capacity. Here’s an example of a conclusion with a general prediction or implication statement with a restatement of thesis.

Modern technology has created many conveniences in everyday life from waking up to music to having coffee ready to getting to work and doing a day’s work. The efficiency provided by technology gives people more time to enjoy life and pursue personal development, and the accessibility has broadened options for travel, school, and work. Without it, everyday life would be filled with burdensome tasks and be limited to our neighborhood and our physical capacity. Modern technology has improved our lives through convenience, efficiency, and accessibility.

Quick Tips for Conclusions

- The conclusion brings the essay to an end and is typically the shortest paragraph.

- It is important to not introduce new ideas or information here.

- Unless otherwise specified in your assignment, just sum up the proof and restate the conclusion.

- Some instructors may want the concluding paragraph to contain a general prediction or observation implied from the information presented.

- Printer-friendly version

Parts of an Essay?

Components of an Essay

An essay is a piece of writing that is written to provide information about a certain topic or simply to convince the reader. In every effective essay writing , there are three major parts: introduction , body , and essay conclusion .

- The introduction. This is where the subject or topic is introduced. The big picture, points, and ideas are briefly written here.

- The body. All the main ideas, topics, and subject are discussed here in details. This also includes evidence or information that support the essay.

- The conclusion. The last part of an essay and usually summarizes the overall topic or ideas of an essay.

How to Write the Introduction Essay?

The introduction is the door to the whole essay outline . It must be convincing enough to get the attention of the readers. The following are the guidelines for writing the introduction of the essay.

- It must contain an attention-getter sentence or statement.

- The introduction must sound interesting to capture the attention of the reader.

- You can quote a statement about a topic or something related to the whole point of your essay.

- The intro must move from general to specific.

- At the end, there must be a thesis statement that gives an insight to the author’s evidence.

What Does the Body of an Essay Contain?

The body is the longest part of the essay and commonly highlights all the topics and ideas. The body must include the following:

- The evidence and supporting details of the expository essay in addition to the author’s ideas.

- A topic or sentences that link the discussion back to the thesis statement.

- The logical ordering of the ideas. The chronological of time, ideas, and evidence.

- A set of transition statements or sentences to create a good flow of the essay.

- Sufficient examples, evidence, data, and information that must be relevant to the particular topic of the essay.

The Conclusion of the Essay

The conclusion is the last part of the essay, and should:

- Emphasize on the major takeaways of the essay.

- Wrap up and summarize the essay, as well as the arguments, ideas, and points.

- Restate the main arguments in a simplified and clear manner that must be understood by the reader.

- Guarantee that the reader is left with something to think about, especially the main point of your essay.

The Elements of an Essay

- Thesis statement. It is the main proposition of an essay. The thesis statement must be arguable that differentiates it from a fact and must be in a persuasive writing style.

- Problem or question. The problem statements or the important issue of the essay that must be defined and described in the essay.

- Motive. The reason for writing the essay.

- Evidence. The facts and data or information that supports the whole essay and prove the main point of the essay.

- Analysis & reflection. In which the writer turns the evidence into an arguable statement that provides the reader how the evidence supports, develops, or explained the essay’s thesis statement.

- Structure. The work that the writer does to organize the idea, the series of sub-topics and sections through which it is explained and developed.

Parts of an Essay Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

Write about the structure and function of an introduction in Parts of an Essay.

Discuss the role of thesis statements in academic writing in Parts of an Essay.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Part One Academic Writing Essentials

Unit 3 Parts and Characteristics of a Good Paragraph

Learning Objectives

- To identify the parts of a paragraph: title, topic sentence, supporting sentences with details, concluding sentence, and transitions

- To understand how each part relates to one another within a paragraph through multiple examples

- To learn the key characteristics of a paragraph: format, unity, cohesion, and completion through multiple examples

- To practice writing each part of a paragraph with key characteristics through a variety of exercises

Read the paragraph “Missing My Childhood Days” below and do the activities that follow.

Missing My Childhood Days

Thanks to two people and one place, my childhood was filled with fun. The first special person was my cousin Hector. I was the only child to my mom, and he was the only child to his mom. We were not lonely because we played and enjoyed family trips together. I loved playing hide and seek with him the most. The running, anticipating [1] , shouting, and laughing will always be in my memories. Secondly, I really miss my best friend Lisandra from my elementary school. Our moms were best friends, so it was easier for us to do many things together. For example, we used to explore the resorts and hotels near our homes. We imagined how we could decorate our own houses as elegantly as the hotels. Additionally, Lisandra had a little sister called Lolanda, and we loved to play with her and care for her as if she were our own baby. We fed her and sang songs to her. Even though I lost contact with Lisandra after she switched to a different school, our time together was very precious to me. Lastly, I really miss my childhood home. It was a big house with a patio decorated with pots of beautiful flowers. The house was large enough for me to ride my bike inside. There was also a pool. We had many family parties there. Playing riddles [2] by the poolside was one of the most popular games among us. Nowadays I do not have Hector and Lisandra in my life, and my childhood house has long been sold. However, I am grateful for having them all in my past because they have left me with priceless [3] memories.

By K. P. Checo (student), ESL Writing III, Harper College. U sed with permission.

Discuss in groups:

- What are your most unforgettable childhood memories? Why are they unforgettable?

- What three areas of childhood does the author miss the most?

- What is the main idea of the above paragraph? Where do you find it in the paragraph?

- Where is the title?

- How does the author begin the paragraph?

- What is the spacing between one line to the next?

- Does each new sentence start a new line?

- What do you think a paragraph is?

- What do you like about this paragraph?

- How would you improve the paragraph?

- If you could ask the writer a question, what would you ask?

II. Definition of a Paragraph

A paragraph is a group of sentences about one main idea. The goal of a paragraph is to communicate to the readers what you think of a topic (your main idea) and why you believe this way (your supporting ideas). A paragraph also follows a certain format. Paragraph writing is the foundation [4] for all types of academic writing assignments such as essays and research papers.

III. Paragraph Format

You can see the format of a paragraph from “Missing My Childhood Days”:

- Center the title in the middle of the top line.

- Start the paragraph with indentation (a few open spaces in the beginning).

- Type or write double spaced.

- Each sentence follows the one before it without starting a new line.

- Use font size 12 if you type. (The font size may be hard for you to determine in this web-book.)

IV. Parts of a Paragraph

Understanding each part of a paragraph is an important step to good writing. One way to do this is to identify and color code each part.

Title – pink Topic sentence – red Supporting sentences – green

Supporting details – blue Concluding sentence – red Transitions – yellow

When you color code the parts, you know that

- you understand the paragraph organization.

- you are not missing any important compone n ts.

- all the parts are in the right order.

- the supporting details ( blue ) should be the longest and the most detailed.

Thanks to two people and one place, my childhood was filled with fun. The first special person was my cousin Hector. I was the only child to my mom, and he was the only child to his mom. We were not lonely because we played and enjoyed family trips together. I loved playing hide and seek with him the most. The running, anticipating, shouting, and laughing will always be in my memories. Secondly , I really miss my best friend Lisandra from the elementary school. Our moms were best friends, so it was easier for us to do many things together. For example, we used to explore the resorts and hotels near our homes. We imagined how we could decorate our own houses as elegantly as the hotels. Additionally, Lisandra had a little sister called Lolanda, and we loved to play with her and care for her as if she were our own baby. We fed her and sang songs to her. Even though I lost contact with Lisandra after she switched to a different school, our time together was very precious to me. Lastly , I really miss my childhood home. It was a big house with a patio decorated with pots of beautiful flowers. The house was large enough for me to ride my bike inside. There was also a pool. We had many family parties there. Playing riddles by the poolside was one of the most popular games among us. Nowadays I do not have Hector and Lisandra in my life, and my childhood house has long been sold. However, I am grateful for having them all in my past because they have left me with priceless memories.

By K. P. Checo (student), ESL Writing III, Harper College. U sed with permission.

Exercise 1. Use Paragraph “Missing My Childhood Days” as an example. Read Paragraph “Difficulties in English Writing” and identify the parts with the following colors:

Title – pink Topic sentence – red Supporting sentences – green

Supporting details – blue Concluding sentence – red Transitions – yellow

Difficulties in English Writing

For me, writing is one of the most difficult skills to learn in English. First, w ith writing comes spelling. Many words are pronounced the same but spelt completely differently, like flower and flour, blue and blew. I need extra effort s to learn and remember how to spell and write them correctly. Another c hallenge I face i n English is sentence structure . There are many types of sentences in English such as simple, compo und, and complex. Each type has its own punctuation rules. It takes a lot of hard work to understand how to build sentences effectively . Finally, grammar is challenging . My professors emphasize the importance of grammar because it plays a significant role in writing. Unfortunately, it is also one of the difficulties for me because it has many , many rules and exceptions. For example, in count and noncount nouns unit , there are many confusing words like police and family . At first, I thought the word “police” was singular, but in fact it is plural. In contrast, I thought the word “family” was plural, but it is singular in many situations ! Mistakes in singular and plural nouns lead to errors in verbs. Despite all these d ifficulties in spelling, sentence structure, and gramm a r , writing remains to be one of my favorite aspects of learning .

By A. Alsalman (student), ESL Writing III, Harper College. U sed with permission.

Read the above two paragraphs again, and you can see that a good paragraph consists of:

- A title – to show the topic and catch the readers’ interest pink

- A beginning called the topic sentence – to show the main idea red

- A middle called the supporting sentences and details – supporting sentences to explain the main idea green ; details to explain the supporting sentences blue

- Transitions or connecting words – to connect the ideas and guide the readers yellow

- An ending called the concluding sentence(s) – to finish the paragraph red

Paragraph Organization – the Hamburger Way

To make a tasty hamburger, you need to take time to get the ingredients ready and stack [5] them up carefully. Planning and organizing your ideas for a good paragraph can be very similar to making a hamburger.

- The sesame seeds on the top piece of bread is what you see as you unwrap a hamburger. It is like the title of a paragraph.

- The top piece of the bread is the first part of the hamburger. It is like the topic sentence .

- The middle part is what makes the hamburger delicious. The more ingredients you add, the tastier the hamburger is. This part is like the supporting sentences with details . More details for the paragraph will make it more interesting to read.

- You also add condiments like mustard, ketchup, and mayonnaise to not only make the hamburger juicier but also help the other ingredients like tomato slices and beef patties stick together. Those condiments are like transitions .

- The last piece of the bread makes the hamburger complete. The bread is made with the same ingredients as the top piece but with a different shape. This is like the concluding sentence. It restates the topic sentence but in a different way.

Below, you are going to learn how to write each part.

V. Title of a Paragraph

A title gives the readers information about what you write in the paragraph. It usually states or implies [6] the topic of your writing.

1. A good title is often very short. Sometimes it is only one word or one phrase. It is usually not a complete sentence.

The Best Invention

The Reasons for My Mediterranean Diet

The Characteristics of a Good Boss

2. A good title catches the readers’ interest. It tells the readers about the main topic, but it does not tell everything.

Why Not Studying Hard?

A Long-Kept Secret

To Mask or Not to Mask

3. A good title follows capitalization and punctuation rules.

- The first letter of the first word is always capitalized.

- Do not capitalize a short preposition, an article, or a coordinating conjunction unless it is the first word.

- Never capitalize the entire title.

- Do not put a period at the end.

- Do not put quotation marks around the title.

- Do not underline the title.

Discuss each pair of the titles below and notice how the errors are corrected.

the day I arrived in Chicago X

The Day I Arrived in Chicago √

THE MAKING OF A DOCTOR X

The Making of a Doctor √

A Very Frustrating Experience. X

A Very Frustrating Experience √

“Advice from My Mother” X

Advice from My Mother √

The Mysterious Noise X

The Mysterious Noise √

For more explanations and examples in capitalization, please refer to Appendix B Capitalization . ( Open Appendix B here.)

Exercise 2. Here are the titles of some paragraphs. Do they follow the rules? Write the correct title in the box. After you finish all the titles, you can check your answers by clicking the “Check” button. You may retry the exercise or see all the answers.

Example :

From my home to school

Correction: From My Home to School

VI. Topic Sentence

A topic sentence is a sentence that contains the main idea of a paragraph. It is usually put in the beginning of a paragraph. A good topic sentence has two essential parts and one optional part:

- the topic of your paragraph

- the controlling idea – your attitude/opinion about the topic

- (optional but preferred) predictors – the points you are going to explain in the body of the paragraph

In each pair of topic sentences below, one contains the topic and controlling idea. The other has the topic, controlling idea, and predictors. Identify each part and discuss which topic sentence you like better. Explain your reasons.

- My writing class is important in helping me prepare for college study.

- My writing class is important in helping me prepare for college study because I learn how to plan, write, and edit my own writing.

- I enjoy three aspects of my writing class.

- I enjoy three aspects of my writing class: my professor, my classmates, and the course materials.

- Many students feel stressed out in the writing class for three reasons.

- Because of long class periods, daily homework assignments, and lots of tests, many students feel stressed out in the writing class.,

- Writing in English is very different from writing in my native language.

- Writing in English differs from writing in my nature language in style, sentence structure, and punctuation.

Rules for a good topic sentence:

1. It must be a complete sentence that contains a subject and a verb.

- My interesting writing class (not a complete sentence) X

- How to improve writing skills (not a complete sentence) X

- My writing class is interesting for three reasons. (a complete sentence) √

- In my writing class, I am learning how to improve writing skills in three ways. (a complete sentence) √

2. It can be a positive or negative statement, not a question. If you ask a question in the beginning of the paragraph, you should answer it in the next sentence. That second sentence is the topic sentence.

- Why is learning English important? (a question) X

- What is the best way to improve writing skills? (a question) X

- Why is learning English important? It is so because good English skills benefit people in their study, work, and daily life. (The second part is the topic sentence.) √

- What is the best way to improve writing skills? I have three suggestions for ESL students to improve writing skills. (The second part is the topic sentence.) √

3. Narrow down your topic. General topics are difficult to focus on and write.

- Year 2020 was a difficult year for me. (too broad) X

- The COVID pandemic in Year 2020 made it difficult for me to study. (more specific) √

- The COVID pandemic in Year 2020 made it difficult for me to study for three reasons: my classes went totally online in March, I could no longer use the college library and the Language Lab, and the poor Internet connection at home often interrupted my study on the course Blackboard site. (more specific) √

4. Do not make an announcement.

- In this paragraph, I am going to talk about the disadvantages to online learning. (an announcement) X

- Let me explain the disadvantages to online learning. (an announcement) X

- This paragraph is about the disadvantages to online learning. (an announcement) X

- There are three disadvantages to online learning. (not an announcement) √

- There are three disadvantages to online learning: no immediate feedback from the professors, no interactions with the classmates, and unstable Internet connection at home. (not an announcement) √

5. Do not write a fact because your opinion (the controlling idea) is missing.

- Harper College is a community college. (a fact) X

- My classmates come from twelve different countries. (a fact) X

- Harper College offers the best ESL programs in Illinois in three aspects: experienced professors, free tutoring, and the Language Lab. (Controlling idea “best” is added.) √

- Representing twelve countries, my classmates are great resources for learning different cultures. (Controlling idea “great resources for learning different cultures” is added.) √

Exercise 3. Read the following topic sentences. Identify the topic, controlling idea, and predictors. Type your answers in the boxes. When you complete the entire exercise, you can click “Check” for feedback. You may retry or see all the answers.

I miss my high school life for three reasons: friends, sports, and time for myself.

topic: my high school life

controlling idea: miss for three reasons

predictors: friends, sports, time for myself

Exercise 4. Are the following good topic sentences? If not, why not? How do you improve them? Click “True” for good topic sentences and “False” for the wrong ones. You will receive instant feedback after each sentence. If a topic sentence is wrong, you will see the correction and explanation in blue .

Electric cars

This is not a good topic sentence because it is not a complete sentence and the controlling idea is missing.

Correction: I like electric cars more than gas-powered cars.

VII. Supporting Ideas and Paragraph Unity

Supporting means “holding up”, just as the bridge is “holding up” the man in the image on the left . Supporting sentences are crucial in “holding up” the main idea while making your paragraphs interesting and convincing [7] . They must support or explain the main idea in the topic sentence.

A good strategy for logical supporting sentences is to predict the question the readers may ask about your topic sentence. The result of this planning is actually the paragraph outline you learned in Unit 2 The Writing Process. (Open Unit 2 here.)

Paragraph Unity

Unity comes from the verb “unite” and means “hold tight, together”. In a paragraph, it means that all the supporting sentences work together to serve the same purpose: explaining the main idea.

Imagine two bouquets of flowers. Both look beautiful and in perfect harmony within themselves. However, if one sunflower is inserted in the middle of the roses, it will look out of place because it breaks the unity of the rose bouquet.

Then how do you tell if your paragraph has unity? There are two easy ways:

- Ask yourself, “Does each supporting sentence explain the controlling idea in the topic sentence?” If yes, your paragraph has unity. If not, you need to delete or change the supporting sentence. It is helpful to circle or underline your controlling idea in the topic sentence for easier checking.

- Always make an outline of the paragraph before you write. If you come up with a new idea while drafting the paragraph, put it in your outline first and ask yourself the first question.

Does the following paragraph outline show unity?

No, it does not show unity. It contains irrelevant [8] ideas because they do not support the main idea “help college students”. Here are ways to improve the outline:

- Cross out the irrelevant ideas.

- Add relevant information to support the main idea.

- In the second support, a personal example is also added to make the paragraph more interesting.

- In the third support, the new idea “manage time better” is a repetition of the second support “practice time management skills”. Therefore, it should be deleted. It is important not to repeat the same information that is already explained in other parts of the support.

Exercise 6. Use the topic sentences below to build relevant supporting ideas. Check to make sure that all the ideas support the main idea in the topic sentence. Share your outline with your partner and discuss each other’s ideas.

Example :

- Topic sentence: Men can often be better care givers than women.

- Topic sentence: People 18 years and older should serve two years in the military.

- Topic sentence: Chicago is the most romantic city in the U.S.

- Topic sentence: Chicago is the best place for children to visit on the weekend.

Exercise 7. The following paragraph about a special place does not have unity. There are four additional sentences to be deleted (not including the example). Type the numbers of the irrelevant sentences in the boxes below. When you complete the entire exercise, you can click “Check” for answers. You may also retry or see all the answers. Sentence #4 is an example.

Types of Supporting Sentences

Good supporting sentences not only explain the main idea but also include interesting details such as

facts – numbers, general truths, scientific truths…

reasons – logical explanations…

experts’ opinion s – research findings, quotes by experts in the field…

examples – stories of well-known people, personal experiences, personal quotes…

Read Paragraph “Good Roommates” below and discuss how the writer uses the types of details. Color supporting ideas in green and the details in blue .

Good Roommates

Having good roommates makes lives more enjoyable. First, good roommates understand each other’s need for peace and quiet after a day’s study. 1 They do not make unnecessary noises. For example, my roommate Abia and I have different class schedules. She spends the day at school, and I attend night classes. When I come back to the apartment very tired at 10 pm, she always turns down her music or speaks very softly on the phone with her friends. Moreover, good roommates share useful information. 2 Writer Barbara Dana once said, “A good roommate may be the single most important thing to have when one is away at school.” It is true because Abia’s and my families are far away. I have taken more courses at college, so I give Abia advice about classes, student clubs, and scholarships. She helps me in a different way. While I was looking for a part-time job last year, she told me about the job openings in her workplace. Finally, good roommates respect each other’s differences. 3 As the U.S. is a land of immigrants, it becomes the land of opportunities to learn different cultures and religions. I have learned about the significance of Ramadan for Abia, and she has understood the importance of Easter for me. Together, we have developed a good understanding of each other’s beliefs. In brief, good roommates help each other become more caring, supportive, and tolerant [9] . They make living easier in this complicated world.

In the first supporting details (first blue block marked with 1): personal examples of Abia and me

In the second supporting details (second blue block marked with 2): a quote by an expert, personal examples of Abia and me

In the third supporting details (third blue block marked with 3): general truth, logic, personal examples of Abia and me

Exercise 8. Use Paragraph “Good Roommates” as an example, read Paragraph “No Capital Punishment” and discuss what types of interesting details the writer uses. Color the supporting ideas in green and the details in blue .

No Capital Punishment [10]

Capital punishment should be banned [11] because the result cannot be changed, it is killing a life, and it does not stop the crime. First of all, the result of capital punishment is irreversible [12] ; therefore, it is important to be absolutely certain of a person’s guilt. Nevertheless, in some cases, this is simply impossible to prove a person’s guilt with 100% certainty. What if a person is wrongly charged? The death penalty will affect that person and his or her family forever. Next, capital punishment is killing. Killing people for any reason is wrong. Life is sacred, and humans do not have the right to decide the lives of others. Some people believe that capital punishment will stop criminals from committing crimes as they will be afraid to die. However, this is not the reality. Violent cases still occur daily. For instance, on the weekend of July 4 th , 2021, Chicago Sun Times reported that over 100 people were shot in Chicago and 19 of them died. That weekend was considered the deadliest and most violent in the city that year. This shows that putting criminals to death will not reduce the crime. For these reasons, death penalty should not be supported. The people and the government must find a better solution [13] to punishing the law breakers.

https://chicago.suntimes.com/crime/2021/7/3/22561910/chicago-weekend-shootings-july-2-5-homicide-gun-violence . Last accessed on July 10, 2021.

VIII. Transitions and Paragraph Cohesion

Cohesion focuses on the link between ideas so that they flow naturally from one to the next. When a paragraph has cohesion, ideas progress smoothly to create a connected whole.

Imagine cohesion as a waterfall cascading [14] smoothly and continuously.

There are different ways to achieve cohesion. One of them is by using transitions.

Transitions are also called connecting words . They help the writer organize thoughts and guide the readers in understanding the order of ideas clearly. Transitions are often needed not only between supporting sentences but also within them.

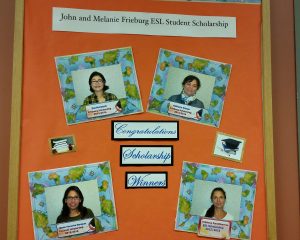

Compare the two paragraphs “Applying for the John & Melanie Frieburg ESL Student Scholarship” below. Which one is better? Why is it better? Underline the transitions in Paragraph 2 that you do not see in Paragraph 1.

Paragraph 1

Applying for the John & Melanie Frieburg ESL Student Scholarship

Applying for the John & Melanie Frieburg ESL Student Scholarship online is not hard if you follow these steps. Go to the scholarship page on the Harper College website and search for this specific scholarship. Read all the information related to it: the requirements, the deadline, and the amount of the award. Fill out the application form online completely and accurately. There are twelve supplemental [15] questions including your grades and financial situation. Do you have an average grade of C? A paragraph about your educational aspiration is required. Get two recommendation letters from two people who know you well. Be sure to ask them first and give them enough time to write the letters. Proofread your application and submit before the deadline. You can always ask help from the Scholarship Office, the ESL Department, or the One Stop Center. The process is easy to follow and well worth your efforts for this special honor.

Paragraph 2

Applying for the John & Melanie Frieburg ESL Student Scholarship online is not hard if you follow these steps. First , go to the scholarship page on the Harper College website and search for this specific scholarship. Read all the information related to it, such as the requirements, the deadline, and the amount of the award. When you are ready , fill out the application form online completely and accurately. There are twelve supplemental questions including your grades and financial situation. For example, do you have an average grade of C? A paragraph about your educational aspiration is also required. Another step is to get two recommendation letters from two people who know you well. Be sure to ask them and give them enough time to write the letters. Finally, proofread your application and submit before the deadline. At any stage of your application, you can always ask for help in the Scholarship Office, the ESL Department, or the One Stop Center. As you can see, the process is easy to follow and well worth your efforts for this special honor.

With connecting expressions like “First”, “such as”, “When you are ready”, and other underlined transitions, Paragraph 2 explains the steps much more clearly.

How are the transitions used?

- The transition for the first supporting idea is often optional.

- “Finally” is usually used to show the last supporting idea in the body of the paragraph. It is not used right before the conclusion.

- The transition before the concluding sentence is optional. It is actually more common without it.

- After most transitions, there is usually a comma, but this is not always true. There are different types of transitions with different punctuation rules. You will learn them step by step throughout the course.

- Do not overuse transitions; otherwise, the paragraph will read very unnatural. As you read and write more, you will gradually develop a sense of when a transition is or is not necessary.

Here are some common transitions:

Study Paragraph “Good Roommates” again. Notice how the three transitions ( first, moreover, finally ) connect the supporting ideas and the transition ( in brief ) is used before the concluding sentences.

Study Paragraph “No Capital Punishment” again. Notice how the transitions ( first of all, therefore, nevertheless, next, however, for instance ) are used to connect ideas between supporting ideas and within them. The transition ( for these reasons ) is placed before the concluding sentence.

Exercise 9. Choose the appropriate transitions below and type them in the boxes to finish the paragraph about a daughter. There may be more than one correct answer, but type just one. Not all listed transitions are needed. When you complete the entire exercise, you can click “Check” for feedback. You may retry or see all the answers. The first one is an example.

first, second, next, in addition, also, furthermore, moreover, last, finally, for example, to sum up

Exercise 10. Choose the appropriate transitions below and type them in the boxes to finish the paragraph about a life lesson. There may be more than one correct answer, but type just one. Not all listed transitions are needed. When you complete the entire exercise, you can click “Check” for feedback. You may retry or see all the answers. The first one is an example.

however, on the first Saturday, then, after crying for an hour, while I was eating breakfast, now, at night, finally, after that, after I arrived

IX. Concluding Sentence(s)

A concluding sentence signals the end of a paragraph.

You can also write two or three sentences in this part with one or

more of the following methods:

- Restates [16] the main idea but in different words or sentence structure.

- Summarize the main points in the body of the paragraph.

- Express an opinion, make a prediction, put forth a recommendation, or ask a question related to the topic.

A conclusion must not bring up a new topic.

× For those three reasons, I enjoy swimming the most. I will also start playing basketball next week.

Exercise 11. Compare the pairs of topic sentences and concluding sentences from the paragraphs you have studied in this unit. Then discuss in groups what method the concluding sentences use and how they relate to the topic sentences.

Paragraph “Missing My Childhood Days”

Topic sentence: Thanks to two people and one place, my childhood was filled with fun.

Concluding sentences : Nowadays I do not have Hector and Lisandra in my life, and my childhood house has long been sold. However, I am grateful for having them all in my past because they have left me with priceless memories.

The conclusion restates the main idea (they have left me with priceless memories), summarizes the three supporting points in the body (I do not have Hector and Lisandra in my life, and my childhood house has long been sold), and expresses an opinion (I am grateful for having them all in my past). The conclusion relates to the topic sentence and explains the controlling idea very well.

- Paragraph “Difficulties in English Writing”

- Paragraph “My Special Place”

- Paragraph “Good Roommates”

- Paragraph “No Capital Punishment”

- Paragraph “Applying for the John & Melanie Frieburg ESL Student Scholarship”

- Paragraph “My Daughter”

- Paragraph “My Valuable Life Lesson”

X. Paragraph Completion

Each paragraph explains a complete idea and needs to have a clear ending. There are several ways to check if the paragraph is complete:

- Does the paragraph have a title?

- Is the topic sentence there?

- If you have predictors in the topic sentence, are all of them explained in the body of the paragraph?

- Are there details to further explain the supporting ideas?

- Do you have a concluding sentence at the end?

- Are there proper transitions to connect ideas?

If any one part is missing, the paragraph is incomplete.

Read the following paragraph. Is it complete? If not, discuss what is missing and how you can improve the paragraph.

Jogging is beneficial physically, mentally, and socially. First, jogging makes people physically fit. It not only strengthens the muscles and immune system but also helps to reduce weight. Thirty minutes of jogging will burn about 250 calories. Extra weight causes all kinds of health problems, and a daily run will help shed [17] the extra pounds. Besides, jogging keeps people mentally healthy by reducing their stress. Modern life is full of anxieties. Workers have project deadlines, students take tests, parents deal with family financial challenges, and all people run into relationship issues from time to time. According to many doctors, jogging can act as a stress reliever [18] , boost [19] the feel-good hormone, and distract people from daily worries. Jogging is a simple act of activity that helps people become healthier in many ways.

What is missing?

- There is no title. Add a title, such as “The Best Exercise” or “The Benefits of Jogging”.

- The third support is missing. From the topic sentence, the readers expect to see support in three areas: physical, mental, and social. However, the writer did not discuss the “social” aspect of jogging. Therefore, the paragraph is incomplete. The writer should add some information about the social benefits of jogging. Ideas could include joining a jogging club and meeting new friends.

Exercise 12. Use the above paragraph as an example. Is the following new one complete? If not, discuss what is missing and how you can improve the paragraph.

Unleashed dogs are dangerous to the environment, other living beings, and even to themselves. First of all, dogs do not have minds like humans; therefore, they often do not know what proper behavior is in public. When they are not restricted by a leash, they can run and step on flowers and plants in the parks. They may also leave their waste there if their owners are unaware of it. What’s more, dogs can frighten the pedestrians on the street. Some of them are afraid of dogs and may experience intense fear when a dog jumps at them. Dogs may also scare drivers. What if they lose control of their vehicles? Other animals like ducks and geese will also find the running and barking “strangers” threatening. Lastly, unleashed dogs are a danger to themselves. There are many hidden holes on the roads and in the parks, and dogs can easily fall into them and hurt themselves. Because dogs can also cause traffic accidents, they may be injured as well. If there is construction nearby with heavy machinery and harmful chemicals, the consequences will be deadly to the dogs.

XI. Unit Review Practice

Exercise 13. Read the following paragraph about online learning. It is based on an outline example you studied earlier in this unit. As you read, do the following:

Color code the paragraph:

Title – pink Topic sentence – red Supporting sentences – green

Supporting details – blue transitions – yellow Concluding sentence(s) – red

Discuss:

- Have you taken an online class? If so, have you had similar experiences as described in this paragraph?

- What types of supporting ideas and details are used to explain the main idea?

- Does the paragraph have unity?

- What types of conclusion are used?

- Is the paragraph complete?

- Is the title centered on the top line? Is the first sentence indented?

- How do you improve the paragraph?

Three Benefits of Online Classes for College Students

Taking online classes helps college students in three significant ways. First of all, online classes provide many conveniences. Many college students have a job, and some also need to take care of their family. When the courses are online, the students often do not have a fixed class time. As a result, they can pick any shift available at work, and they can also schedule activities with their loved ones like going to the park or even going on a vacation. For those with small children, childcare is no longer a huge issue. In addition, some college students do not own a car, but their education will not be affected because they can take classes remotely. Secondly, college students improve their time management skills. I have learned to use my time more wisely. For example, during my first semester of online class, I spent a lot of time video chatting with my friends in the beginning. My professor set all the test deadlines by midnight each Sunday, so I postponed my study till Saturday. However, there was too much reading and practicing then, and I simply could not complete the required study to get a good grade. In the second half of the semester, I forced myself to make a schedule for daily study time and to be more disciplined [20] in following it. I was able to finish all the materials before the test, and my grade improved. The most important skill through online learning is independent learning. Even though professors are available through office hours, emails, and live sessions, students must learn to solve problems on their own most of the times. They can do so by reading, checking dictionaries, and finding additional online learning resources from YouTube videos or the Khan Academy website. The type of “self help” foster skills in independent learning, which is essential in college study and future profession. Taking online classes is challenging, but these benefits make their experiences worthwhile.

NSNT Practice

Go to The NSNT Free Writing Approach and Additional Weekly Prompts for Writing in Appendix A. ( Open Appendix A here. ) Choose two topics to practice the steps in the writing process, including writing a paragraph for each. You may start with the NSNT approach and then rewrite the paragraphs. Check to see that the paragraphs have all the necessary parts and that they follow the rules for format, unity, cohesion, and completion.

Vocabulary Review

The words here have appeared in this unit. The best way to learn them is to guess the meaning of each word from the context. Then hover your computer mouse over the number beside each word to check its meaning and part of speech. These words are also listed in the footnote area at the end of each unit.

Here, you can use the flashcards below to review these words.

- A paragraph is a group of sentences with one main idea.

- A paragraph must follow a proper format, with the title in the center of the top line and an indent in the beginning of the paragraph. All the sentences should be written/typed double spaced and follow one another without starting a new line.

- A paragraph consists of a title, a topic sentence, several supporting ideas with details, 1-2 concluding sentences, and transitions.

- Each paragraph should have all the above necessary components. If one of them is missing, the paragraph is not complete.

- A title explain the topic of the paragraph or gets the readers interested in the topic. It is centered on the first line and should follow the capitalization rules.

- A topic sentence contains the main idea of a paragraph and is usually put in the beginning. It must have a topic and a controlling idea. It must be a complete sentence and should not be a fact or an announcement.

- Supporting sentences should be detailed and should help explain the topic sentence. If anything is irrelevant to the main idea, the paragraph will not have unity.

- A concluding sentence restates the main idea and signals the end of the paragraph. It can include an opinion, a suggestion, a recommendation, or a question that is related to the topic.

- Transitions are important in guiding the readers in understanding the information in the paragraph and providing a smooth connection between ideas. Transitions help maintain the cohesion of a paragraph.

Media Attributions

- a group of children running and laughing outdoors © Photo by MI PHAM on Unsplash

- a hamburger © Photo by amirali mirhashemian on Unsplash

- parts of a hamburger © Photo by Pablo Merchán Montes on Unsplash

- lots of books showing titles on shelves © Photo by CHUTTERSNAP on Unsplash

- a light bulb surrounded by six circles © Pixabay

- a man sitting on a bridge over a river © Photo by Alex Azabache on Unsplash

- a rose bouquet © Photo by Enrique Avendaño on Unsplash

- a sunflower bouquet © Photo by Farrinni on Unsplash

- a balcony with a table, two chairs, and some plants © Photo by Nguyen Dang Hoang Nhu on Unsplash

- waterfall in Yellowstone National Park © Lin Cui is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- ESL Scholarship winners 2015/2016 © Lin Cui is licensed under a All Rights Reserved license

- words “THE END” on wooden pieces © Photo by Ann H from Pexels

- a checklist and a yellow pencil © Tumisu on Pixabay

- unleashed dogs on beach © Photo by Laura Stanley from Pexels

- a MacBook, a notebook, etc. on a desk © Photo by Nick Morrison on Unsplash

- a pen writing in a notebook © Photo by Aaron Burden on Unsplash

- a page in a dictionary © Pixabay

- anticipate: verb, wait for something to happen ↵

- riddle: noun, a game of guessing the answers ↵

- priceless: adjective, very valuable, cannot be measured by a price ↵

- foundation: noun, basis, groundwork of something more complicated ↵

- stack: verb, to pile or put one on top of another ↵

- imply: verb, say indirectly ↵

- convincing: adjective, make people believe ↵

- irrelevant: adjective, not related, having nothing to do with the main idea ↵

- tolerant: adjective, accepting differences ↵

- capital punishment, noun phrase, a type of punishment to kill a criminal ↵

- ban: verb, stop, not allowed to happen ↵

- irreversible: adjective, cannot go back to the original situation ↵

- solution: noun, the answer to a problem ↵

- cascade: verb, flow from high to low smoothly ↵

- supplemental: adjective, extra, additional ↵

- restate: verb, write again, repeat ↵

- shed: verb, get rid of ↵

- stress reliever: noun phrase, something to reduce or take away stress ↵

- boost: verb, raise, improve ↵

- disciplined: adjective, self-controlled, strict with oneself ↵

Building Academic Writing Skills Copyright © 2022 by Cui, Lin is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Heart-Healthy Living

- High Blood Pressure

- Sickle Cell Disease

- Sleep Apnea

- Information & Resources on COVID-19

- The Heart Truth®

- Learn More Breathe Better®

- Blood Diseases and Disorders Education Program

- Publications and Resources

- Blood Disorders and Blood Safety

- Sleep Science and Sleep Disorders

- Lung Diseases

- Health Disparities and Inequities

- Heart and Vascular Diseases

- Precision Medicine Activities

- Obesity, Nutrition, and Physical Activity

- Population and Epidemiology Studies

- Women’s Health

- Research Topics

- Clinical Trials

- All Science A-Z

- Grants and Training Home

- Policies and Guidelines

- Funding Opportunities and Contacts

- Training and Career Development

- Email Alerts

- NHLBI in the Press

- Research Features

- Past Events

- Upcoming Events

- Mission and Strategic Vision

- Divisions, Offices and Centers

- Advisory Committees

- Budget and Legislative Information

- Jobs and Working at the NHLBI

- Contact and FAQs

- NIH Sleep Research Plan

- Health Topics

- < Back To How the Heart Works

- How Blood Flows through the Heart

- What the Heart Looks Like

- How the Heart Beats

MORE INFORMATION

How the Heart Works How Blood Flows through the Heart

Language switcher.

Arteries and veins link your heart to the rest of the circulatory system. Veins bring blood to your heart. Arteries take blood away from your heart. Your heart valves help control the direction the blood flows.

Heart valves

Heart valves control the flow of blood so that it moves in the right direction. The valves prevent blood from flowing backward.

The heart has four valves.

- The tricuspid valve separates the right atrium and right ventricle.

- The mitral valve separates the left atrium and left ventricle.

- The pulmonary valve separates the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery.

- The aortic valve separates the left ventricle and aorta.

The valves open and shut in time with the pumping action of your heart's chambers. The opening and closing involve a set of flaps called cusps or leaflets. The cusps open to allow blood to flow out of a chamber and close to allow the chamber to refill with blood. Heart valve diseases can cause backflow or slow the flow of blood through the heart.

Learn about what the valves of the heart look like and do. Medical Animation Copyright © 2022 Nucleus Medical Media, All rights reserved .

Adding oxygen to blood

Oxygen-poor blood from the body enters your heart through two large veins called the superior and inferior vena cava. The blood enters the heart's right atrium and is pumped to your right ventricle, which in turn pumps the blood to your lungs.

The pulmonary artery then carries the oxygen-poor blood from your heart to the lungs. Your lungs add oxygen to your blood. The oxygen-rich blood returns to your heart through the pulmonary veins. Visit our How the Lungs Work page to learn more about what happens to the blood in the lungs.

The oxygen-rich blood from the lungs then enters the left atrium and is pumped to the left ventricle. The left ventricle generates the high pressure needed to pump the blood to your whole body through your blood vessels.

When blood leaves the heart to go to the rest of the body, it travels through a large artery called the aorta. A balloon-like bulge, called an aortic aneurysm , can sometimes occur in the aorta.

Learn about how your heart circulates blood to your lungs and throughout your body. Medical Animation Copyright © 2022 Nucleus Medical Media, All rights reserved .

Supplying oxygen to the heart’s muscle

Like other muscles in the body, your heart needs blood to get oxygen and nutrients. Your coronary arteries supply blood to your heart. These arteries branch off from the aorta so that oxygen-rich blood is delivered to your heart as well as the rest of your body.

- The left coronary artery delivers blood to the left side of your heart, including your left atrium and ventricle and the septum between the ventricles.

- The circumflex artery branches off from the left coronary artery to supply blood to part of the left ventricle.

- The left anterior descending artery also branches from the left coronary artery and provides blood to parts of both the right and left ventricles.

- The right coronary artery provides blood to the right atrium and parts of both ventricles.

- The marginal arteries branch from the right coronary artery and provide blood to the surface of the right atrium.

- The posterior descending artery also branches from the right coronary artery and provides blood to the bottom of both ventricles.

Your coronary arteries supply oxygen to your body. Medical Animation Copyright © 2022 Nucleus Medical Media, All rights reserved .

Some conditions can affect normal blood flow through these heart arteries. Examples include:

- Heart attack

- Coronary heart disease

The coronary veins return oxygen-low blood from the heart's muscles back to the right atrium so it can be pumped to the lungs. They include:

- The anterior cardiac veins

- The great cardiac vein

- The middle cardiac vein

- The small cardiac vein

Collaborative on Global Children's Issues

Collaborating for Ukrainian Children: Reflecting on the Second Anniversary of Russia's Invasion of Ukraine