- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

An Emergency Physician’s Path pp 557–563 Cite as

Scientific Manuscript Writing: Original Research, Case Reports, Review Articles

- Kimberly M. Rathbun 5

- First Online: 02 March 2024

Manuscripts are used to communicate the findings of your work with other researchers. Writing your first manuscript can be a challenge. Journals provide guidelines to authors which should be followed closely. The three major types of articles (original research, case reports, and review articles) all generally follow the IMRAD format with slight variations in content. With planning and thought, manuscript writing does not have to be a daunting task.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Suggested Readings

Alsaywid BS, Abdulhaq NM. Guideline on writing a case report. Urol Ann. 2019;11(2):126–31.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cohen H. How to write a patient case report. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006;63(19):1888–92.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cooper ID. How to write an original research paper (and get it published). J Med Lib Assoc. 2015;103:67–8.

Article Google Scholar

Gemayel R. How to write a scientific paper. FEBS J. 2016;283(21):3882–5.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gülpınar Ö, Güçlü AG. How to write a review article? Turk J Urol. 2013;39(Suppl 1):44–8.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Huth EJ. Structured abstracts for papers reporting clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:626–7.

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals. http://www.ICMJE.org . Accessed 23 Aug 2022.

Liumbruno GM, Velati C, Pasqualetti P, Franchini M. How to write a scientific manuscript for publication. Blood Transfus. 2013;11:217–26.

McCarthy LH, Reilly KE. How to write a case report. Fam Med. 2000;32(3):190–5.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, McKenzie JE. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160.

The Biosemantics Group. Journal/author name estimator. https://jane.biosemantics.org/ . Accessed 24 Aug 2022.

Weinstein R. How to write a manuscript for peer review. J Clin Apher. 2020;35(4):358–66.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Emergency Medicine, AU/UGA Medical Partnership, Athens, GA, USA

Kimberly M. Rathbun

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kimberly M. Rathbun .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Emergency Medicine, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, PA, USA

Robert P. Olympia

Elizabeth Barrall Werley

Jeffrey S. Lubin

MD Anderson Cancer Center at Cooper, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, Camden, NJ, USA

Kahyun Yoon-Flannery

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Rathbun, K.M. (2023). Scientific Manuscript Writing: Original Research, Case Reports, Review Articles. In: Olympia, R.P., Werley, E.B., Lubin, J.S., Yoon-Flannery, K. (eds) An Emergency Physician’s Path. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47873-4_80

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-47873-4_80

Published : 02 March 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-47872-7

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-47873-4

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

How to write a good scientific review article

Affiliation.

- 1 The FEBS Journal Editorial Office, Cambridge, UK.

- PMID: 35792782

- DOI: 10.1111/febs.16565

Literature reviews are valuable resources for the scientific community. With research accelerating at an unprecedented speed in recent years and more and more original papers being published, review articles have become increasingly important as a means to keep up to date with developments in a particular area of research. A good review article provides readers with an in-depth understanding of a field and highlights key gaps and challenges to address with future research. Writing a review article also helps to expand the writer's knowledge of their specialist area and to develop their analytical and communication skills, amongst other benefits. Thus, the importance of building review-writing into a scientific career cannot be overstated. In this instalment of The FEBS Journal's Words of Advice series, I provide detailed guidance on planning and writing an informative and engaging literature review.

© 2022 Federation of European Biochemical Societies.

Publication types

- Review Literature as Topic*

- Enroll & Pay

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Degree Programs

Original Research

An original research paper should present a unique argument of your own. In other words, the claim of the paper should be debatable and should be your (the researcher’s) own original idea. Typically an original research paper builds on the existing research on a topic, addresses a specific question, presents the findings according to a standard structure (described below), and suggests questions for further research and investigation. Though writers in any discipline may conduct original research, scientists and social scientists in particular are interested in controlled investigation and inquiry. Their research often consists of direct and indirect observation in the laboratory or in the field. Many scientists write papers to investigate a hypothesis (a statement to be tested).

Although the precise order of research elements may vary somewhat according to the specific task, most include the following elements:

- Table of contents

- List of illustrations

- Body of the report

- References cited

Check your assignment for guidance on which formatting style is required. The Complete Discipline Listing Guide (Purdue OWL) provides information on the most common style guide for each discipline, but be sure to check with your instructor.

The title of your work is important. It draws the reader to your text. A common practice for titles is to use a two-phrase title where the first phrase is a broad reference to the topic to catch the reader’s attention. This phrase is followed by a more direct and specific explanation of your project. For example:

“Lions, Tigers, and Bears, Oh My!: The Effects of Large Predators on Livestock Yields.”

The first phrase draws the reader in – it is creative and interesting. The second part of the title tells the reader the specific focus of the research.

In addition, data base retrieval systems often work with keywords extracted from the title or from a list the author supplies. When possible, incorporate them into the title. Select these words with consideration of how prospective readers might attempt to access your document. For more information on creating keywords, refer to this Springer research publication guide.

See the KU Writing Center Writing Guide on Abstracts for detailed information about creating an abstract.

Table of Contents

The table of contents provides the reader with the outline and location of specific aspects of your document. Listings in the table of contents typically match the headings in the paper. Normally, authors number any pages before the table of contents as well as the lists of illustrations/tables/figures using lower-case roman numerals. As such, the table of contents will use lower-case roman numbers to identify the elements of the paper prior to the body of the report, appendix, and reference page. Additionally, because authors will normally use Arabic numerals (e.g., 1, 2, 3) to number the pages of the body of the research paper (starting with the introduction), the table of contents will use Arabic numerals to identify the main sections of the body of the paper (the introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, conclusion, references, and appendices).

Here is an example of a table of contents:

ABSTRACT..................................................iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS...............................iv

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS...........................v

LIST OF TABLES.........................................vii

INTRODUCTION..........................................1

LITERATURE REVIEW.................................6

METHODS....................................................9

RESULTS....................................................10

DISCUSSION..............................................16

CONCLUSION............................................18

REFERENCES............................................20

APPENDIX................................................. 23

More information on creating a table of contents can be found in the Table of Contents Guide (SHSU) from the Newton Gresham Library at Sam Houston State University.

List of Illustrations

Authors typically include a list of the illustrations in the paper with longer documents. List the number (e.g., Illustration 4), title, and page number of each illustration under headings such as "List of Illustrations" or "List of Tables.”

Body of the Report

The tone of a report based on original research will be objective and formal, and the writing should be concise and direct. The structure will likely consist of these standard sections: introduction, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion . Typically, authors identify these sections with headings and may use subheadings to identify specific themes within these sections (such as themes within the literature under the literature review section).

Introduction

Given what the field says about this topic, here is my contribution to this line of inquiry.

The introduction often consists of the rational for the project. What is the phenomenon or event that inspired you to write about this topic? What is the relevance of the topic and why is it important to study it now? Your introduction should also give some general background on the topic – but this should not be a literature review. This is the place to give your readers and necessary background information on the history, current circumstances, or other qualities of your topic generally. In other words, what information will a layperson need to know in order to get a decent understanding of the purpose and results of your paper? Finally, offer a “road map” to your reader where you explain the general order of the remainder of your paper. In the road map, do not just list the sections of the paper that will follow. You should refer to the main points of each section, including the main arguments in the literature review, a few details about your methods, several main points from your results/analysis, the most important takeaways from your discussion section, and the most significant conclusion or topic for further research.

Literature Review

This is what other researchers have published about this topic.

In the literature review, you will define and clarify the state of the topic by citing key literature that has laid the groundwork for this investigation. This review of the literature will identify relations, contradictions, gaps, and inconsistencies between previous investigations and this one, and suggest the next step in the investigation chain, which will be your hypothesis. You should write the literature review in the present tense because it is ongoing information.

Methods (Procedures)

This is how I collected and analyzed the information.

This section recounts the procedures of the study. You will write this in past tense because you have already completed the study. It must include what is necessary to replicate and validate the hypothesis. What details must the reader know in order to replicate this study? What were your purposes in this study? The challenge in this section is to understand the possible readers well enough to include what is necessary without going into detail on “common-knowledge” procedures. Be sure that you are specific enough about your research procedure that someone in your field could easily replicate your study. Finally, make sure not to report any findings in this section.

This is what I found out from my research.

This section reports the findings from your research. Because this section is about research that is completed, you should write it primarily in the past tense . The form and level of detail of the results depends on the hypothesis and goals of this report, and the needs of your audience. Authors of research papers often use visuals in the results section, but the visuals should enhance, rather than serve as a substitute, for the narrative of your results. Develop a narrative based on the thesis of the paper and the themes in your results and use visuals to communicate key findings that address your hypothesis or help to answer your research question. Include any unusual findings that will clarify the data. It is a good idea to use subheadings to group the results section into themes to help the reader understand the main points or findings of the research.

This is what the findings mean in this situation and in terms of the literature more broadly.

This section is your opportunity to explain the importance and implications of your research. What is the significance of this research in terms of the hypothesis? In terms of other studies? What are possible implications for any academic theories you utilized in the study? Are there any policy implications or suggestions that result from the study? Incorporate key studies introduced in the review of literature into your discussion along with your own data from the results section. The discussion section should put your research in conversation with previous research – now you are showing directly how your data complements or contradicts other researchers’ data and what the wider implications of your findings are for academia and society in general. What questions for future research do these findings suggest? Because it is ongoing information, you should write the discussion in the present tense . Sometimes the results and discussion are combined; if so, be certain to give fair weight to both.

These are the key findings gained from this research.

Summarize the key findings of your research effort in this brief final section. This section should not introduce new information. You can also address any limitations from your research design and suggest further areas of research or possible projects you would complete with a new and improved research design.

References/Works Cited

See KU Writing Center writing guides to learn more about different citation styles like APA, MLA, and Chicago. Make an appointment at the KU Writing Center for more help. Be sure to format the paper and references based on the citation style that your professor requires or based on the requirements of the academic journal or conference where you hope to submit the paper.

The appendix includes attachments that are pertinent to the main document but are too detailed to be included in the main text. These materials should be titled and labeled (for example Appendix A: Questionnaire). You should refer to the appendix in the text with in-text references so the reader understands additional useful information is available elsewhere in the document. Examples of documents to include in the appendix include regression tables, tables of text analysis data, and interview questions.

Updated June 2022

- Main Library

- Digital Fabrication Lab

- Data Visualization Lab

- Business Learning Center

- Klai Juba Wald Architectural Studies Library

- NDSU Nursing at Sanford Health Library

- Research Assistance

- Special Collections

- Digital Collections

- Collection Development Policy

- Course Reserves

- Request Library Instruction

- Main Library Services

- Alumni & Community

- Academic Support Services in the Library

- Libraries Resources for Employees

- Book Equipment or Study Rooms

- Librarians by Academic Subject

- Germans from Russia Heritage Collection

- NDSU Archives

- Mission, Vision, and Strategic Plan 2022-2024

- Staff Directory

- Floor Plans

- The Libraries Magazine

- Accommodations for People with Disabilities

- Annual Report

- Donate to the Libraries

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

- Faculty Senate Library Committee

- Undergraduate Research Award

What is an original research article?

An original research article is a report of research activity that is written by the researchers who conducted the research or experiment. Original research articles may also be referred to as: “primary research articles” or “primary scientific literature.” In science courses, instructors may also refer to these as “peer-reviewed articles” or “refereed articles.”

Original research articles in the sciences have a specific purpose, follow a scientific article format, are peer reviewed, and published in academic journals.

Identifying Original Research: What to Look For

An "original research article" is an article that is reporting original research about new data or theories that have not been previously published. That might be the results of new experiments, or newly derived models or simulations. The article will include a detailed description of the methods used to produce them, so that other researchers can verify them. This description is often found in a section called "methods" or "materials and methods" or similar. Similarly, the results will generally be described in great detail, often in a section called "results."

Since the original research article is reporting the results of new research, the authors should be the scientists who conducted that research. They will have expertise in the field, and will usually be employed by a university or research lab.

In comparison, a newspaper or magazine article (such as in The New York Times or National Geographic ) will usually be written by a journalist reporting on the actions of someone else.

An original research article will be written by and for scientists who study related topics. As such, the article should use precise, technical language to ensure that other researchers have an exact understanding of what was done, how to do it, and why it matters. There will be plentiful citations to previous work, helping place the research article in a broader context. The article will be published in an academic journal, follow a scientific format, and undergo peer-review.

Original research articles in the sciences follow the scientific format. ( This tutorial from North Carolina State University illustrates some of the key features of this format.)

Look for signs of this format in the subject headings or subsections of the article. You should see the following:

Scientific research that is published in academic journals undergoes a process called "peer review."

The peer review process goes like this:

- A researcher writes a paper and sends it in to an academic journal, where it is read by an editor

- The editor then sends the article to other scientists who study similar topics, who can best evaluate the article

- The scientists/reviewers examine the article's research methodology, reasoning, originality, and sginificance

- The scientists/reviewers then make suggestions and comments to impove the paper

- The original author is then given these suggestions and comments, and makes changes as needed

- This process repeats until everyone is satisfied and the article can be published within the academic journal

For more details about this process see the Peer Reviewed Publications guide.

This journal article is an example. It was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science in 2015. Clicking on the button that says "Review History" will show the comments by the editors, reviewers and the author as it went through the peer review process. The "About Us" menu provides details about this journal; "About the journal" under that tab includes the statement that the journal is peer reviewed.

Review articles

There are a variety of article types published in academic, peer-reviewed journals, but the two most common are original research articles and review articles . They can look very similar, but have different purposes and structures.

Like original research articles, review articles are aimed at scientists and undergo peer-review. Review articles often even have “abstract,” “introduction,” and “reference” sections. However, they will not (generally) have a “methods” or “results” section because they are not reporting new data or theories. Instead, they review the current state of knowledge on a topic.

Press releases, newspaper or magazine articles

These won't be in a formal scientific format or be peer reviewed. The author will usually be a journalist, and the audience will be the general public. Since most readers are not interested in the precise details of the research, the language will usually be nontechnical and broad. Citations will be rare or nonexistent.

Tips for Finding Original research Articles

Search for articles in one of the library databases recommend for your subject area . If you are using Google, try searching in Google Scholar instead and you will get results that are more likely to be original research articles than what will come up in a regular Google search!

For tips on using library databases to find articles, see our Library DIY guides .

Tips for Finding the Source of a News Report about Science

If you've seen or heard a report about a new scientific finding or claim, these tips can help you find the original source:

- Often, the report will mention where the original research was published; look for sentences like "In an article published yesterday in the journal Nature ..." You can use this to find the issue of the journal where the research was published, and look at the table of contents to find the original article.

- The report will often name the researchers involved. You can search relevant databases for their name and the topic of the report to find the original research that way.

- Sometimes you may have to go through multiple articles to find the original source. For example, a video or blog post may be based on a newspaper article, which in turn is reporting on a scientific discovery published in another journal; be sure to find the original research article.

- Don't be afraid to ask a librarian for help!

Search The Site

Find Your Librarian

Phone: Circulation: (701) 231-8888 Reference: (701) 231-8888 Administration: (701) 231-8753

Email: Administration InterLibrary Loan (ILL)

- Online Services

- Phone/Email Directory

- Registration And Records

- Government Information

- Library DIY

- Subject and Course Guides

- Special Topics

- Collection Highlights

- Digital Horizons

- NDSU Repository (IR)

- Libraries Hours

- News & Events

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

7 Writing a Literature Review

Hundreds of original investigation research articles on health science topics are published each year. It is becoming harder and harder to keep on top of all new findings in a topic area and – more importantly – to work out how they all fit together to determine our current understanding of a topic. This is where literature reviews come in.

In this chapter, we explain what a literature review is and outline the stages involved in writing one. We also provide practical tips on how to communicate the results of a review of current literature on a topic in the format of a literature review.

7.1 What is a literature review?

Literature reviews provide a synthesis and evaluation of the existing literature on a particular topic with the aim of gaining a new, deeper understanding of the topic.

Published literature reviews are typically written by scientists who are experts in that particular area of science. Usually, they will be widely published as authors of their own original work, making them highly qualified to author a literature review.

However, literature reviews are still subject to peer review before being published. Literature reviews provide an important bridge between the expert scientific community and many other communities, such as science journalists, teachers, and medical and allied health professionals. When the most up-to-date knowledge reaches such audiences, it is more likely that this information will find its way to the general public. When this happens, – the ultimate good of science can be realised.

A literature review is structured differently from an original research article. It is developed based on themes, rather than stages of the scientific method.

In the article Ten simple rules for writing a literature review , Marco Pautasso explains the importance of literature reviews:

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications. For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively. Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests. Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read. For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way (Pautasso, 2013, para. 1).

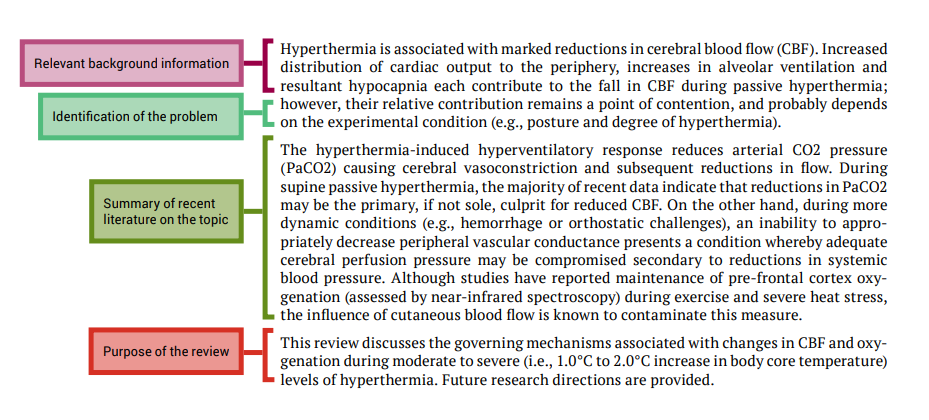

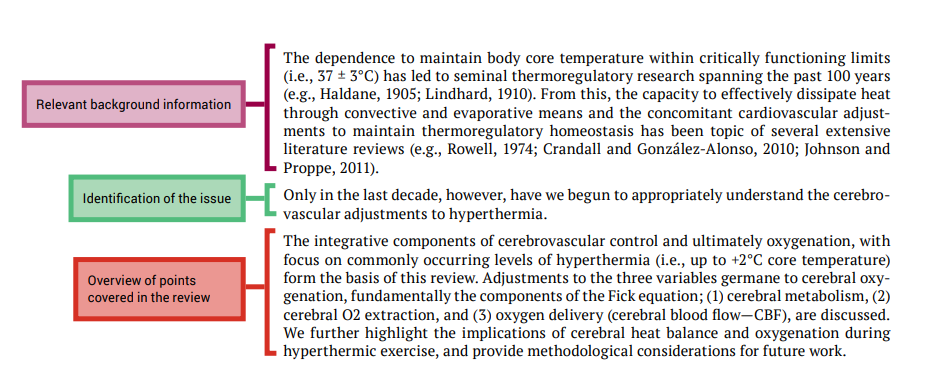

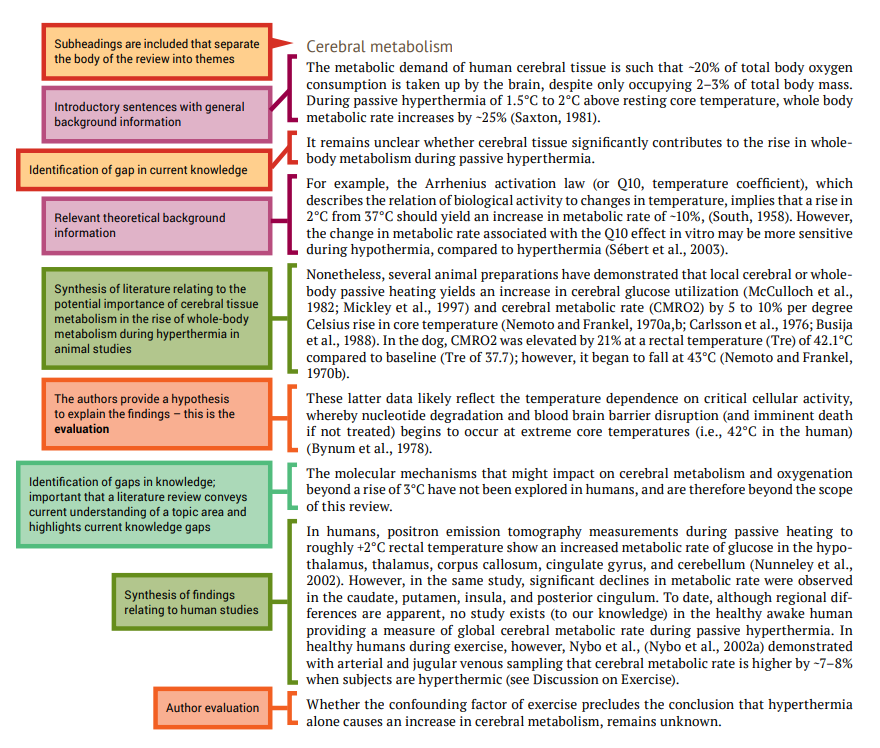

An example of a literature review is shown in Figure 7.1.

Video 7.1: What is a literature review? [2 mins, 11 secs]

Watch this video created by Steely Library at Northern Kentucky Library called ‘ What is a literature review? Note: Closed captions are available by clicking on the CC button below.

Examples of published literature reviews

- Strength training alone, exercise therapy alone, and exercise therapy with passive manual mobilisation each reduce pain and disability in people with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review

- Traveler’s diarrhea: a clinical review

- Cultural concepts of distress and psychiatric disorders: literature review and research recommendations for global mental health epidemiology

7.2 Steps of writing a literature review

Writing a literature review is a very challenging task. Figure 7.2 summarises the steps of writing a literature review. Depending on why you are writing your literature review, you may be given a topic area, or may choose a topic that particularly interests you or is related to a research project that you wish to undertake.

Chapter 6 provides instructions on finding scientific literature that would form the basis for your literature review.

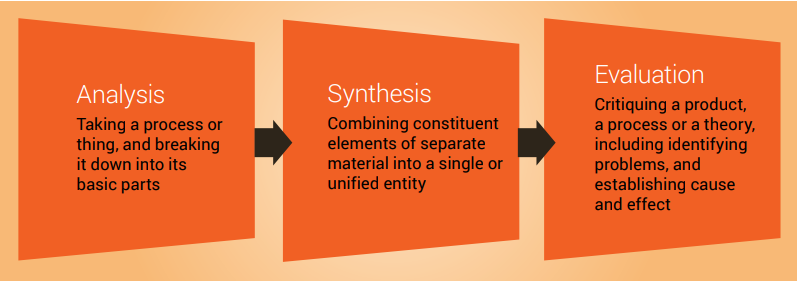

Once you have your topic and have accessed the literature, the next stages (analysis, synthesis and evaluation) are challenging. Next, we look at these important cognitive skills student scientists will need to develop and employ to successfully write a literature review, and provide some guidance for navigating these stages.

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation

Analysis, synthesis and evaluation are three essential skills required by scientists and you will need to develop these skills if you are to write a good literature review ( Figure 7.3 ). These important cognitive skills are discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

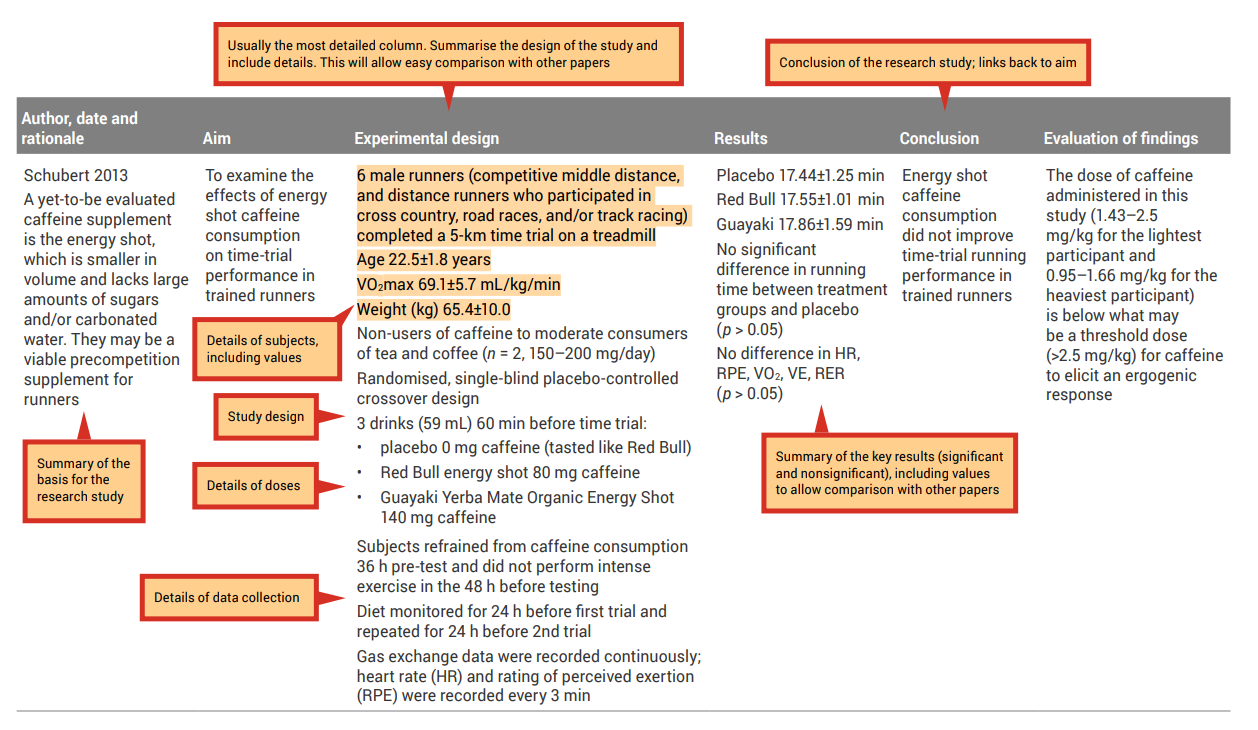

The first step in writing a literature review is to analyse the original investigation research papers that you have gathered related to your topic.

Analysis requires examining the papers methodically and in detail, so you can understand and interpret aspects of the study described in each research article.

An analysis grid is a simple tool you can use to help with the careful examination and breakdown of each paper. This tool will allow you to create a concise summary of each research paper; see Table 7.1 for an example of an analysis grid. When filling in the grid, the aim is to draw out key aspects of each research paper. Use a different row for each paper, and a different column for each aspect of the paper ( Tables 7.2 and 7.3 show how completed analysis grid may look).

Before completing your own grid, look at these examples and note the types of information that have been included, as well as the level of detail. Completing an analysis grid with a sufficient level of detail will help you to complete the synthesis and evaluation stages effectively. This grid will allow you to more easily observe similarities and differences across the findings of the research papers and to identify possible explanations (e.g., differences in methodologies employed) for observed differences between the findings of different research papers.

Table 7.1: Example of an analysis grid

Table 7.3: Sample filled-in analysis grid for research article by Ping and colleagues

Source: Ping, WC, Keong, CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41. Used under a CC-BY-NC-SA licence.

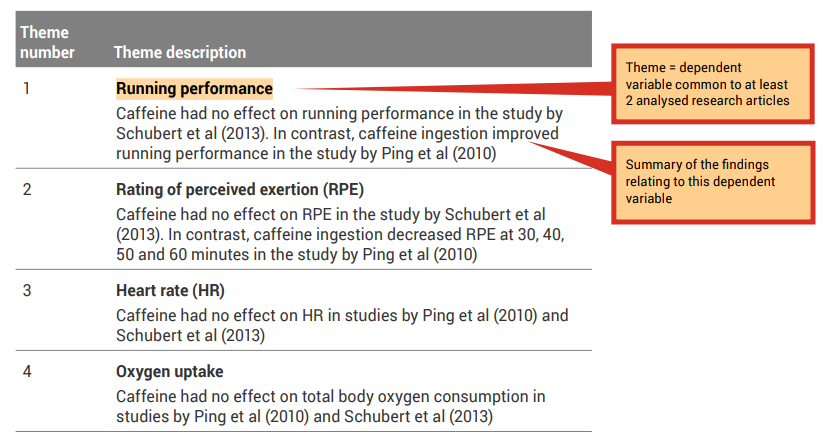

Step two of writing a literature review is synthesis.

Synthesis describes combining separate components or elements to form a connected whole.

You will use the results of your analysis to find themes to build your literature review around. Each of the themes identified will become a subheading within the body of your literature review.

A good place to start when identifying themes is with the dependent variables (results/findings) that were investigated in the research studies.

Because all of the research articles you are incorporating into your literature review are related to your topic, it is likely that they have similar study designs and have measured similar dependent variables. Review the ‘Results’ column of your analysis grid. You may like to collate the common themes in a synthesis grid (see, for example Table 7.4 ).

Step three of writing a literature review is evaluation, which can only be done after carefully analysing your research papers and synthesising the common themes (findings).

During the evaluation stage, you are making judgements on the themes presented in the research articles that you have read. This includes providing physiological explanations for the findings. It may be useful to refer to the discussion section of published original investigation research papers, or another literature review, where the authors may mention tested or hypothetical physiological mechanisms that may explain their findings.

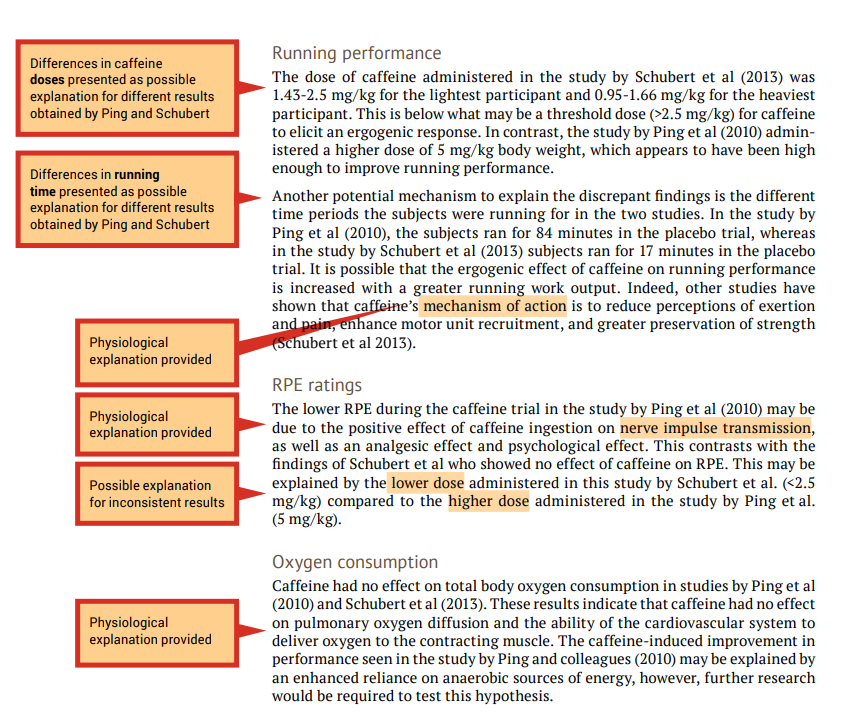

When the findings of the investigations related to a particular theme are inconsistent (e.g., one study shows that caffeine effects performance and another study shows that caffeine had no effect on performance) you should attempt to provide explanations of why the results differ, including physiological explanations. A good place to start is by comparing the methodologies to determine if there are any differences that may explain the differences in the findings (see the ‘Experimental design’ column of your analysis grid). An example of evaluation is shown in the examples that follow in this section, under ‘Running performance’ and ‘RPE ratings’.

When the findings of the papers related to a particular theme are consistent (e.g., caffeine had no effect on oxygen uptake in both studies) an evaluation should include an explanation of why the results are similar. Once again, include physiological explanations. It is still a good idea to compare methodologies as a background to the evaluation. An example of evaluation is shown in the following under ‘Oxygen consumption’.

7.3 Writing your literature review

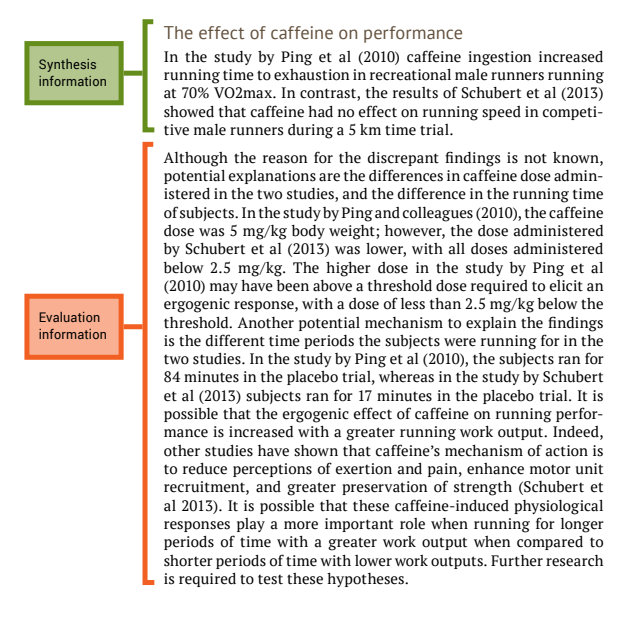

Once you have completed the analysis, and synthesis grids and written your evaluation of the research papers , you can combine synthesis and evaluation information to create a paragraph for a literature review ( Figure 7.4 ).

The following paragraphs are an example of combining the outcome of the synthesis and evaluation stages to produce a paragraph for a literature review.

Note that this is an example using only two papers – most literature reviews would be presenting information on many more papers than this ( (e.g., 106 papers in the review article by Bain and colleagues discussed later in this chapter). However, the same principle applies regardless of the number of papers reviewed.

The next part of this chapter looks at the each section of a literature review and explains how to write them by referring to a review article that was published in Frontiers in Physiology and shown in Figure 7.1. Each section from the published article is annotated to highlight important features of the format of the review article, and identifies the synthesis and evaluation information.

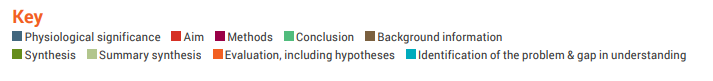

In the examination of each review article section we will point out examples of how the authors have presented certain information and where they display application of important cognitive processes; we will use the colour code shown below:

This should be one paragraph that accurately reflects the contents of the review article.

Introduction

The introduction should establish the context and importance of the review

Body of literature review

The reference section provides a list of the references that you cited in the body of your review article. The format will depend on the journal of publication as each journal has their own specific referencing format.

It is important to accurately cite references in research papers to acknowledge your sources and ensure credit is appropriately given to authors of work you have referred to. An accurate and comprehensive reference list also shows your readers that you are well-read in your topic area and are aware of the key papers that provide the context to your research.

It is important to keep track of your resources and to reference them consistently in the format required by the publication in which your work will appear. Most scientists will use reference management software to store details of all of the journal articles (and other sources) they use while writing their review article. This software also automates the process of adding in-text references and creating a reference list. In the review article by Bain et al. (2014) used as an example in this chapter, the reference list contains 106 items, so you can imagine how much help referencing software would be. Chapter 5 shows you how to use EndNote, one example of reference management software.

Click the drop down below to review the terms learned from this chapter.

Copyright note:

- The quotation from Pautasso, M 2013, ‘Ten simple rules for writing a literature review’, PLoS Computational Biology is use under a CC-BY licence.

- Content from the annotated article and tables are based on Schubert, MM, Astorino, TA & Azevedo, JJL 2013, ‘The effects of caffeinated ‘energy shots’ on time trial performance’, Nutrients, vol. 5, no. 6, pp. 2062–2075 (used under a CC-BY 3.0 licence ) and P ing, WC, Keong , CC & Bandyopadhyay, A 2010, ‘Effects of acute supplementation of caffeine on cardiorespiratory responses during endurance running in a hot and humid climate’, Indian Journal of Medical Research, vol. 132, pp. 36–41 (used under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 licence ).

Bain, A.R., Morrison, S.A., & Ainslie, P.N. (2014). Cerebral oxygenation and hyperthermia. Frontiers in Physiology, 5 , 92.

Pautasso, M. (2013). Ten simple rules for writing a literature review. PLoS Computational Biology, 9 (7), e1003149.

How To Do Science Copyright © 2022 by University of Southern Queensland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Original Research – Definition, Examples, Guide

Original Research – Definition, Examples, Guide

Table of Contents

Original Research

Definition:

Original research refers to a type of research that involves the collection and analysis of new and original data to answer a specific research question or to test a hypothesis. This type of research is conducted by researchers who aim to generate new knowledge or add to the existing body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline.

Types of Original Research

There are several types of original research that researchers can conduct depending on their research question and the nature of the data they are collecting. Some of the most common types of original research include:

Basic Research

This type of research is conducted to expand scientific knowledge and to create new theories, models, or frameworks. Basic research often involves testing hypotheses and conducting experiments or observational studies.

Applied Research

This type of research is conducted to solve practical problems or to develop new products or technologies. Applied research often involves the application of basic research findings to real-world problems.

Exploratory Research

This type of research is conducted to gather preliminary data or to identify research questions that need further investigation. Exploratory research often involves collecting qualitative data through interviews, focus groups, or observations.

Descriptive Research

This type of research is conducted to describe the characteristics or behaviors of a population or a phenomenon. Descriptive research often involves collecting quantitative data through surveys, questionnaires, or other standardized instruments.

Correlational Research

This type of research is conducted to determine the relationship between two or more variables. Correlational research often involves collecting quantitative data and using statistical analyses to identify correlations between variables.

Experimental Research

This type of research is conducted to test cause-and-effect relationships between variables. Experimental research often involves manipulating one or more variables and observing the effect on an outcome variable.

Longitudinal Research

This type of research is conducted over an extended period of time to study changes in behavior or outcomes over time. Longitudinal research often involves collecting data at multiple time points.

Original Research Methods

Original research can involve various methods depending on the research question, the nature of the data, and the discipline or field of study. However, some common methods used in original research include:

This involves the manipulation of one or more variables to test a hypothesis. Experimental research is commonly used in the natural sciences, such as physics, chemistry, and biology, but can also be used in social sciences, such as psychology.

Observational Research

This involves the collection of data by observing and recording behaviors or events without manipulation. Observational research can be conducted in the natural setting of the behavior or in a laboratory setting.

Survey Research

This involves the collection of data from a sample of participants using questionnaires or interviews. Survey research is commonly used in social sciences, such as sociology, political science, and economics.

Case Study Research

This involves the in-depth analysis of a single case, such as an individual, organization, or event. Case study research is commonly used in social sciences and business studies.

Qualitative research

This involves the collection and analysis of non-numerical data, such as interviews, focus groups, and observation notes. Qualitative research is commonly used in social sciences, such as anthropology, sociology, and psychology.

Quantitative research

This involves the collection and analysis of numerical data using statistical methods. Quantitative research is commonly used in natural sciences, such as physics, chemistry, and biology, as well as in social sciences, such as psychology and economics.

Researchers may also use a combination of these methods in their original research depending on their research question and the nature of their data.

Data Collection Methods

There are several data collection methods that researchers can use in original research, depending on the nature of the research question and the type of data that needs to be collected. Some of the most common data collection methods include:

- Surveys : Surveys involve asking participants to respond to a series of questions about their attitudes, behaviors, beliefs, or experiences. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through email, or online.

- Interviews : Interviews involve asking participants open-ended questions about their experiences, beliefs, or behaviors. Interviews can be conducted in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing.

- Observations : Observations involve observing and recording participants’ behaviors or interactions in a natural or laboratory setting. Observations can be conducted using structured or unstructured methods.

- Experiments : Experiments involve manipulating one or more variables and observing the effect on an outcome variable. Experiments can be conducted in a laboratory or in the natural environment.

- Case studies: Case studies involve conducting an in-depth analysis of a single case, such as an individual, organization, or event. Case studies can involve the collection of qualitative or quantitative data.

- Focus groups: Focus groups involve bringing together a small group of participants to discuss a specific topic or issue. Focus groups can be conducted in person or online.

- Document analysis: Document analysis involves collecting and analyzing written or visual materials, such as reports, memos, or videos, to answer research questions.

Data Analysis Methods

Once data has been collected in original research, it needs to be analyzed to answer research questions and draw conclusions. There are various data analysis methods that researchers can use, depending on the type of data collected and the research question. Some common data analysis methods used in original research include:

- Descriptive statistics: This involves using statistical measures such as mean, median, mode, and standard deviation to describe the characteristics of the data.

- Inferential statistics: This involves using statistical methods to infer conclusions about a population based on a sample of data.

- Regression analysis: This involves examining the relationship between two or more variables by using statistical models that predict the value of one variable based on the value of one or more other variables.

- Content analysis: This involves analyzing written or visual materials, such as documents, videos, or social media posts, to identify patterns, themes, or trends.

- Qualitative analysis: This involves analyzing non-numerical data, such as interview transcripts or observation notes, to identify themes, patterns, or categories.

- Grounded theory: This involves developing a theory or model based on the data collected in the study.

- Mixed methods analysis: This involves combining quantitative and qualitative data analysis methods to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research question.

How to Conduct Original Research

Conducting original research involves several steps that researchers need to follow to ensure that their research is valid, reliable, and produces meaningful results. Here are some general steps that researchers can follow to conduct original research:

- Identify the research question: The first step in conducting original research is to identify a research question that is relevant, significant, and feasible. The research question should be specific and focused to guide the research process.

- Conduct a literature review: Once the research question is identified, researchers should conduct a thorough literature review to identify existing research on the topic. This will help them identify gaps in the existing knowledge and develop a research plan that builds on previous research.

- Develop a research plan: Researchers should develop a research plan that outlines the methods they will use to collect and analyze data. The research plan should be detailed and include information on the population and sample, data collection methods, data analysis methods, and ethical considerations.

- Collect data: Once the research plan is developed, researchers can begin collecting data using the methods identified in the plan. It is important to ensure that the data collection process is consistent and accurate to ensure the validity and reliability of the data.

- Analyze data: Once the data is collected, researchers should analyze it using appropriate data analysis methods. This will help them answer the research question and draw conclusions from the data.

- Interpret results: After analyzing the data, researchers should interpret the results and draw conclusions based on the findings. This will help them answer the research question and make recommendations for future research or practical applications.

- Communicate findings: Finally, researchers should communicate their findings to the appropriate audience using a format that is appropriate for the research question and audience. This may include writing a research paper, presenting at a conference, or creating a report for a client or stakeholder.

Purpose of Original Research

The purpose of original research is to generate new knowledge and understanding in a particular field of study. Original research is conducted to address a research question, hypothesis, or problem and to produce empirical evidence that can be used to inform theory, policy, and practice. By conducting original research, researchers can:

- Expand the existing knowledge base: Original research helps to expand the existing knowledge base by providing new information and insights into a particular phenomenon. This information can be used to develop new theories, models, or frameworks that explain the phenomenon in greater depth.

- Test existing theories and hypotheses: Original research can be used to test existing theories and hypotheses by collecting empirical evidence and analyzing the data. This can help to refine or modify existing theories, or to develop new ones that better explain the phenomenon.

- Identify gaps in the existing knowledge: Original research can help to identify gaps in the existing knowledge base by highlighting areas where further research is needed. This can help to guide future research and identify new research questions that need to be addressed.

- Inform policy and practice: Original research can be used to inform policy and practice by providing empirical evidence that can be used to make decisions and develop interventions. This can help to improve the quality of life for individuals and communities, and to address social, economic, and environmental challenges.

How to publish Original Research

Publishing original research involves several steps that researchers need to follow to ensure that their research is accepted and published in reputable academic journals. Here are some general steps that researchers can follow to publish their original research:

- Select a suitable journal: Researchers should identify a suitable academic journal that publishes research in their field of study. The journal should have a good reputation and a high impact factor, and should be a good fit for the research topic and methods used.

- Review the submission guidelines: Once a suitable journal is identified, researchers should review the submission guidelines to ensure that their manuscript meets the journal’s requirements. The guidelines may include requirements for formatting, length, and content.

- Write the manuscript : Researchers should write the manuscript in accordance with the submission guidelines and academic standards. The manuscript should include a clear research question or hypothesis, a description of the research methods used, an analysis of the data collected, and a discussion of the results and their implications.

- Submit the manuscript: Once the manuscript is written, researchers should submit it to the selected journal. The submission process may require the submission of a cover letter, abstract, and other supporting documents.

- Respond to reviewer feedback: After the manuscript is submitted, it will be reviewed by experts in the field who will provide feedback on the quality and suitability of the research. Researchers should carefully review the feedback and revise the manuscript accordingly.

- Respond to editorial feedback: Once the manuscript is revised, it will be reviewed by the journal’s editorial team who will provide feedback on the formatting, style, and content of the manuscript. Researchers should respond to this feedback and make any necessary revisions.

- Acceptance and publication: If the manuscript is accepted, the journal will inform the researchers and the manuscript will be published in the journal. If the manuscript is not accepted, researchers can submit it to another journal or revise it further based on the feedback received.

How to Identify Original Research

To identify original research, there are several factors to consider:

- The research question: Original research typically starts with a novel research question or hypothesis that has not been previously explored or answered in the existing literature.

- The research design: Original research should have a clear and well-designed research methodology that follows appropriate scientific standards. The methodology should be described in detail in the research article.

- The data: Original research should include new data that has not been previously published or analyzed. The data should be collected using appropriate research methods and analyzed using valid statistical methods.

- The results: Original research should present new findings or insights that have not been previously reported in the existing literature. The results should be presented clearly and objectively, and should be supported by the data collected.

- The discussion and conclusions: Original research should provide a clear and objective interpretation of the results, and should discuss the implications of the research findings. The discussion and conclusions should be based on the data collected and the research question or hypothesis.

- The references: Original research should be supported by references to existing literature, which should be cited appropriately in the research article.

Advantages of Original Research

Original research has several advantages, including:

- Generates new knowledge: Original research is conducted to answer novel research questions or hypotheses, which can generate new knowledge and insights into various fields of study.

- Supports evidence-based decision making: Original research provides empirical evidence that can inform decision-making in various fields, such as medicine, public policy, and business.

- Enhances academic and professional reputation: Conducting original research and publishing in reputable academic journals can enhance a researcher’s academic and professional reputation.

- Provides opportunities for collaboration: Original research can provide opportunities for collaboration between researchers, institutions, and organizations, which can lead to new partnerships and research projects.

- Advances scientific and technological progress: Original research can contribute to scientific and technological progress by providing new knowledge and insights into various fields of study, which can inform further research and development.

- Can lead to practical applications: Original research can have practical applications in various fields, such as medicine, engineering, and social sciences, which can lead to new products, services, and policies that benefit society.

Limitations of Original Research

Original research also has some limitations, which include:

- Time and resource constraints: Original research can be time-consuming and expensive, requiring significant resources to design, execute, and analyze the research data.

- Ethical considerations: Conducting original research may raise ethical considerations, such as ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of research participants, obtaining informed consent, and avoiding conflicts of interest.

- Risk of bias: Original research may be subject to biases, such as selection bias, measurement bias, and publication bias, which can affect the validity and reliability of the research findings.

- Generalizability: Original research findings may not be generalizable to larger populations or different contexts, which can limit the applicability of the research findings.

- Replicability: Original research may be difficult to replicate, which can limit the ability of other researchers to verify the research findings.

- Limited scope: Original research may have a limited scope, focusing on a specific research question or hypothesis, which can limit the breadth of the research findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Documentary Research – Types, Methods and...

Scientific Research – Types, Purpose and Guide

Humanities Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Historical Research – Types, Methods and Examples

Artistic Research – Methods, Types and Examples

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Research and Review Papers: The Key Differences

Research and review papers are two of the most common types of scholarly works that contribute to a field’s progress. Despite their similarities, these two forms of writing have distinct differences in structure, content, purpose, and tone. This article will explore the distinctions between research papers and reviews by exploring each type separately before comparing them in terms of academic rigor, length, methodology used for data gathering or analysis (if applicable), formal language use in referencing sources as well as citing references throughout the paper itself. Finally we will discuss ways students can effectively differentiate between research papers versus review documents when engaging with either form while completing assignments or producing new work themselves.

1. Introduction: Investigating the Difference Between Research and Review Papers

2. types of scholarly papers commonly used in academia, 3. characteristics that distinguish a research paper from a review paper, 4. the role of original research within each type of paper, 5. structural elements unique to each kind of academic writing, 6. tips for differentiating between the two types when analyzing content, 7. conclusion: examining how understanding the differences can help students write better quality papers.

Exploring the Differences between Research and Review Papers The academic world is often abuzz with discourse on research and review papers. These two types of writing are distinct in their approach, structure, content and purpose. To begin, a research paper represents an original piece of work that involves comprehensive study into existing knowledge. It requires students to use scientific methodology to investigate topics by collecting data through experimentation or observation; it should then be analyzed thoroughly before any conclusions can be drawn. On the other hand, a review paper is more focused on existing literature: synthesizing different authors’ views together while pointing out various similarities/differences among them. The main goal is usually critiquing previous theories from an objective point-of-view rather than offering new ones for consideration.

In terms of composition style and formatting preferences – both types require rigorous proofreading but there are some nuances that distinguish one from another as well: research papers will typically feature introduction + body (with sections such as background info., materials & methods etc.)+ conclusion; reviews may also have this organization yet rely heavily on summarization techniques due to its nature of being secondary material based only off previously published works by others in the field at hand! Furthermore — references cited within research papers need to meet certain criteria whereas those included within review pieces can vary greatly depending upon particular topic under examination – so always remember these subtle distinctions when considering which type you’re trying write next time around!

When pursuing an academic career, it is important to be familiar with the different types of scholarly papers used in academia. Different areas of research often require different paper styles depending on the specifics and focus of the project. Here are two types that tend to be widely accepted.

Research papers and review papers are two distinct types of scholarly works, each with its own purpose. The primary difference between the two is that research papers aim to provide new insight into a given topic whereas review papers build upon existing knowledge by summarizing what has already been published on the subject.

- Purpose : Research paper typically focus on identifying or verifying an answer to a specific question or hypothesis through rigorous investigation of evidence from primary sources (e.g., empirical studies). Review articles, however, tend to evaluate and synthesize pre-existing information for readers’ benefit.

- Scope : While research articles often examine only one aspect of their chosen topic in great detail, reviews take a wider angle by combining multiple studies together under one umbrella theme. Reviews also incorporate other forms of data such as interviews, surveys and anecdotal accounts to offer more comprehensive insights.

Original research papers and review papers are two distinct types of academic writing, with each having its own set of specific requirements. Original research is the backbone behind any great paper as it allows for new facts to be discovered or revealed while providing an opportunity for interpretation and analysis. On the other hand, a review paper synthesizes previous work from multiple sources into one cohesive argument that can help provide greater insight into an issue.

- It provides a starting point by establishing evidence-based information on which to build further knowledge.

- It offers readers the chance to view your original insights in light of existing theories and literature.

- It establishes credibility when peers recognize contributions you have made based on careful investigation

Reviews allow researchers to combine ideas from several different studies into one more comprehensive overview . They enable readers—such as those studying at higher levels who lack time —to quickly familiarize themselves with current findings without needing additional primary data collection or synthesis .

Essay Writing

The hallmark of essay writing is the way it structures ideas into a coherent argument. Essays usually consist of an introduction, several body paragraphs and a conclusion. Each section can take up multiple pages as students may need to elaborate on key points or evidence from research studies to back up their point of view. It is essential that each paragraph logically transitions in order for readers to make sense out of them when they are read together.

Research Paper Writing A research paper requires much more extensive analysis than an essay does. In addition to discussing related literature, these papers often involve collecting data through surveys or experiments and providing detailed descriptions about study results and conclusions reached based on this information. Research papers may include charts, tables and diagrams in addition to written text which help illustrate any scientific processes or observations found during the course of investigations conducted by the student author.

- Compare & Contrast : A review paper will cover different aspects but unlike a research paper it won’t include gathering new data.

Distinguishing Content Analysis Types:

Analyzing content can be a daunting task without an understanding of the two types: research papers and review papers. Research papers are typically written to explain new results, while review papers offer insights on existing literature. Although both types focus on evidence-based arguments in their analysis, it is possible to differentiate between them through several tips.

Firstly, research paper should have a hypothesis that was tested with data or experiments. It is likely this work will include quantitative methods such as statistics or qualitative techniques like interviews; these elements make it easier to identify a paper’s type as one of empirical research rather than just opinion pieces. In contrast, review articles summarize what has already been published and assess current trends within the field instead of examining hypotheses.

- When researching scientific topics especially check if figures are included.

In general, primary sources from other researchers are necessary for creating original claims whereas reviews usually cite many secondary sources because they do not involve original findings.

- Consider which facts appear most frequently when analyzing whether something is a primary source.

Comprehending the Distinctions

Aspiring academic writers should be aware that research papers and review papers are fundamentally different. While each requires in-depth analysis, synthesis of existing literature, careful referencing and citation of sources, a research paper is intended to present original findings while a review paper provides an overview and synthesis of relevant sources. Therefore, an understanding of these distinctions can help students write better quality papers.

When writing either type of paper it’s important for students to understand their objectives. A successful research paper will require more time spent conducting independent investigation or experimentation than would a review paper which typically involves summarizing the conclusions drawn by other scholars on the topic being studied. Furthermore when formulating arguments in either type student must take into consideration how best to use evidence from reliable scholarly sources as support for their views.

- Research Papers: Involves gathering new data through primary investigation or experiments.

- Review Paper: Involves synthesising existing literature on particular subject.

In conclusion knowledge about both types can assist student authors craft higher caliber assignments as well as give them confidence that they have chosen appropriate approaches in tackling difficult topics within academia .

As a final thought, it is important to understand the differences between research and review papers in order to make sure that any work produced reflects an appropriate level of academic rigour. Research papers are typically more complex than reviews because they require original findings through empirical or theoretical study, whereas reviews rely on synthesizing existing literature from multiple sources. Knowing the key distinctions between these two types of writing can help ensure accuracy, clarity and ultimately success for both students and professionals alike when producing written works for submission or publication.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 15 April 2024

Revealed: the ten research papers that policy documents cite most

- Dalmeet Singh Chawla 0

Dalmeet Singh Chawla is a freelance science journalist based in London.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Policymakers often work behind closed doors — but the documents they produce offer clues about the research that influences them. Credit: Stefan Rousseau/Getty

When David Autor co-wrote a paper on how computerization affects job skill demands more than 20 years ago, a journal took 18 months to consider it — only to reject it after review. He went on to submit it to The Quarterly Journal of Economics , which eventually published the work 1 in November 2003.

Autor’s paper is now the third most cited in policy documents worldwide, according to an analysis of data provided exclusively to Nature . It has accumulated around 1,100 citations in policy documents, show figures from the London-based firm Overton (see ‘The most-cited papers in policy’), which maintains a database of more than 12 million policy documents, think-tank papers, white papers and guidelines.

“I thought it was destined to be quite an obscure paper,” recalls Autor, a public-policy scholar and economist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. “I’m excited that a lot of people are citing it.”

The most-cited papers in policy

Economics papers dominate the top ten papers that policy documents reference most.

Data from Sage Policy Profiles as of 15 April 2024

The top ten most cited papers in policy documents are dominated by economics research; the number one most referenced study has around 1,300 citations. When economics studies are excluded, a 1997 Nature paper 2 about Earth’s ecosystem services and natural capital is second on the list, with more than 900 policy citations. The paper has also garnered more than 32,000 references from other studies, according to Google Scholar. Other highly cited non-economics studies include works on planetary boundaries, sustainable foods and the future of employment (see ‘Most-cited papers — excluding economics research’).

These lists provide insight into the types of research that politicians pay attention to, but policy citations don’t necessarily imply impact or influence, and Overton’s database has a bias towards documents published in English.

Interdisciplinary impact

Overton usually charges a licence fee to access its citation data. But last year, the firm worked with the London-based publisher Sage to release a free web-based tool that allows any researcher to find out how many times policy documents have cited their papers or mention their names. Overton and Sage said they created the tool, called Sage Policy Profiles, to help researchers to demonstrate the impact or influence their work might be having on policy. This can be useful for researchers during promotion or tenure interviews and in grant applications.

Autor thinks his study stands out because his paper was different from what other economists were writing at the time. It suggested that ‘middle-skill’ work, typically done in offices or factories by people who haven’t attended university, was going to be largely automated, leaving workers with either highly skilled jobs or manual work. “It has stood the test of time,” he says, “and it got people to focus on what I think is the right problem.” That topic is just as relevant today, Autor says, especially with the rise of artificial intelligence.

Most-cited papers — excluding economics research

When economics studies are excluded, the research papers that policy documents most commonly reference cover topics including climate change and nutrition.

Walter Willett, an epidemiologist and food scientist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, thinks that interdisciplinary teams are most likely to gain a lot of policy citations. He co-authored a paper on the list of most cited non-economics studies: a 2019 work 3 that was part of a Lancet commission to investigate how to feed the global population a healthy and environmentally sustainable diet by 2050 and has accumulated more than 600 policy citations.

“I think it had an impact because it was clearly a multidisciplinary effort,” says Willett. The work was co-authored by 37 scientists from 17 countries. The team included researchers from disciplines including food science, health metrics, climate change, ecology and evolution and bioethics. “None of us could have done this on our own. It really did require working with people outside our fields.”

Sverker Sörlin, an environmental historian at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm, agrees that papers with a diverse set of authors often attract more policy citations. “It’s the combined effect that is often the key to getting more influence,” he says.

Has your research influenced policy? Use this free tool to check

Sörlin co-authored two papers in the list of top ten non-economics papers. One of those is a 2015 Science paper 4 on planetary boundaries — a concept defining the environmental limits in which humanity can develop and thrive — which has attracted more than 750 policy citations. Sörlin thinks one reason it has been popular is that it’s a sequel to a 2009 Nature paper 5 he co-authored on the same topic, which has been cited by policy documents 575 times.

Although policy citations don’t necessarily imply influence, Willett has seen evidence that his paper is prompting changes in policy. He points to Denmark as an example, noting that the nation is reformatting its dietary guidelines in line with the study’s recommendations. “I certainly can’t say that this document is the only thing that’s changing their guidelines,” he says. But “this gave it the support and credibility that allowed them to go forward”.

Broad brush

Peter Gluckman, who was the chief science adviser to the prime minister of New Zealand between 2009 and 2018, is not surprised by the lists. He expects policymakers to refer to broad-brush papers rather than those reporting on incremental advances in a field.

Gluckman, a paediatrician and biomedical scientist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand, notes that it’s important to consider the context in which papers are being cited, because studies reporting controversial findings sometimes attract many citations. He also warns that the list is probably not comprehensive: many policy papers are not easily accessible to tools such as Overton, which uses text mining to compile data, and so will not be included in the database.

The top 100 papers

“The thing that worries me most is the age of the papers that are involved,” Gluckman says. “Does that tell us something about just the way the analysis is done or that relatively few papers get heavily used in policymaking?”

Gluckman says it’s strange that some recent work on climate change, food security, social cohesion and similar areas hasn’t made it to the non-economics list. “Maybe it’s just because they’re not being referred to,” he says, or perhaps that work is cited, in turn, in the broad-scope papers that are most heavily referenced in policy documents.

As for Sage Policy Profiles, Gluckman says it’s always useful to get an idea of which studies are attracting attention from policymakers, but he notes that studies often take years to influence policy. “Yet the average academic is trying to make a claim here and now that their current work is having an impact,” he adds. “So there’s a disconnect there.”

Willett thinks policy citations are probably more important than scholarly citations in other papers. “In the end, we don’t want this to just sit on an academic shelf.”

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-024-00660-1

Autor, D. H., Levy, F. & Murnane, R. J. Q. J. Econ. 118 , 1279–1333 (2003).

Article Google Scholar

Costanza, R. et al. Nature 387 , 253–260 (1997).

Willett, W. et al. Lancet 393 , 447–492 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Steffen, W. et al. Science 347 , 1259855 (2015).

Rockström, J. et al. Nature 461 , 472–475 (2009).

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

We must protect the global plastics treaty from corporate interference

World View 17 APR 24

UN plastics treaty: don’t let lobbyists drown out researchers

Editorial 17 APR 24

Smoking bans are coming: what does the evidence say?

News 17 APR 24

CERN’s impact goes way beyond tiny particles

Spotlight 17 APR 24

The economic commitment of climate change

Article 17 APR 24

Last-mile delivery increases vaccine uptake in Sierra Leone

Article 13 MAR 24

Postdoctoral Position

We are seeking highly motivated and skilled candidates for postdoctoral fellow positions

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston Children's Hospital (BCH)

Qiushi Chair Professor

Distinguished scholars with notable achievements and extensive international influence.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Zhejiang University

ZJU 100 Young Professor

Promising young scholars who can independently establish and develop a research direction.

Head of the Thrust of Robotics and Autonomous Systems

Reporting to the Dean of Systems Hub, the Head of ROAS is an executive assuming overall responsibility for the academic, student, human resources...

Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Guangzhou)

Head of Biology, Bio-island

Head of Biology to lead the discovery biology group.

BeiGene Ltd.