- Material Detail: NIMHD Research Framework

Material Detail

NIMHD Research Framework

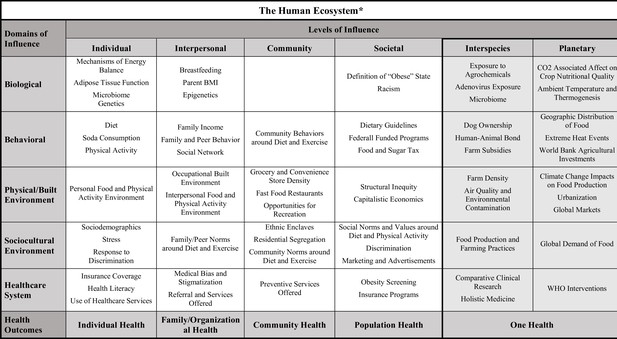

The NIMHD Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework reflects an evolving conceptualization of factors relevant to the understanding and promotion of minority health and to the understanding and reduction of health disparities.

- Health Sciences / Healthcare Administration

- User Rating

- Comments (2) Comments

- Learning Exercises

- Bookmark Collections

- Course ePortfolios

- Accessibility Info

- Report Broken Link

- Report as Inappropriate

More about this material

Disciplines with similar materials as NIMHD Research Framework

People who viewed this also viewed.

Other materials like NIMHD Research Framework

Nancyruth Leibold (Faculty)

Tokesha Warner (Faculty)

Edit comment.

Edit comment for material NIMHD Research Framework

Delete Comment

This will delete the comment from the database. This operation is not reversible. Are you sure you want to do it?

Report a Broken Link

Thank you for reporting a broken "Go to Material" link in MERLOT to help us maintain a collection of valuable learning materials.

Would you like to be notified when it's fixed?

Do you know the correct URL for the link?

Link Reported as Broken

Link report failed, report an inappropriate material.

If you feel this material is inappropriate for the MERLOT Collection, please click SEND REPORT, and the MERLOT Team will investigate. Thank you!

Material Reported as Inappropriate

Material report failed, comment reported as inappropriate, leaving merlot.

You are being taken to the material on another site. This will open a new window.

Do not show me this again

Rate this Material

Search by ISBN?

It looks like you have entered an ISBN number. Would you like to search using what you have entered as an ISBN number?

Searching for Members?

You entered an email address. Would you like to search for members? Click Yes to continue. If no, materials will be displayed first. You can refine your search with the options on the left of the results page.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 18 August 2022

A framework for digital health equity

- Safiya Richardson 1 ,

- Katharine Lawrence ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5640-2138 1 ,

- Antoinette M. Schoenthaler 1 &

- Devin Mann ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2099-0852 1

npj Digital Medicine volume 5 , Article number: 119 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

31k Accesses

104 Citations

144 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health policy

- Public health

We present a comprehensive Framework for Digital Health Equity, detailing key digital determinants of health (DDoH), to support the work of digital health tool creators in industry, health systems operations, and academia. The rapid digitization of healthcare may widen health disparities if solutions are not developed with these determinants in mind. Our framework builds on the leading health disparities framework, incorporating a digital environment domain. We examine DDoHs at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels, discuss the importance of a root cause, multi-level approach, and offer a pragmatic case study that applies our framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

Rigorous and rapid evidence assessment in digital health with the evidence DEFINED framework

Deploying digital health tools within large, complex health systems: key considerations for adoption and implementation

Sync fast and solve things—best practices for responsible digital health

Introduction.

Decades of research have identified health differences, based on one or more health outcomes, that adversely affect several defined populations, including rural populations, persons with low incomes, racial and ethnic, and sexual and gender minorities 1 . Early work in the field of health disparities focused on identifying and describing these differences and their potential causes. In the last two decades, there has been a growing understanding of the role of systemic oppression as a root cause of disparities, as well as a commitment to discovering effective interventions 2 , 3 . The field’s focus on health equity reflects this shift. Health equity refers to the absence of health inequities, differences in health that are unnecessary, avoidable, unfair, and unjust 4 .

As the field of health disparities has matured, we’ve simultaneously witnessed the digital transformation of healthcare. The Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health (HITECH) Act of 2009 sparked the long-awaited adoption of electronic health records (EHRs) by healthcare systems across the country and eventually the development of patient portals, allowing patients online access to key elements of their medical charts. Today, over 95% of hospitals use a government-certified EHR and allow their patients to view health information online 5 . HITECH additionally spurred private industry investment in digital health, including mobile health, wearable devices, remote patient monitoring (RPM), and telehealth, which now is noted in billions per year.

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic highlighted both the continued impact of long-standing systemic oppression on disparate health outcomes as well as the growing importance of digital healthcare. Several studies found significant differences in successful telehealth use in disparity populations 6 , 7 , 8 . Access to digital health is becoming an increasingly important determinant of health. There has been a growing recognition of access as just one of several determinants in the digital environment that impact outcomes 9 , 10 . These digital determinants of health (DDoH), including access to technological tools, digital literacy, and community infrastructure like broadband internet, likely function independently as barriers to and facilitators of health as well as interact with the social determinants of health (SDoH) to impact outcomes 11 , 12 .

As digital health becomes increasingly essential, a framework for digital health equity detailing key DDoHs, is needed to support the work of leaders and developers in the industry, health systems operations, and academia. Digital health solution developers include computer scientists, software architects, product managers, and user experience designers. The digital transformation of health requires leaders and developers to understand how digital determinants impact health equity. In this article, we present the Framework for Digital Health Equity, an expansion of the leading health disparities framework. We examine key DDoHs at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels, discuss the importance of a root cause, multi-level approach, and offer a pragmatic case study as an example application of our framework.

Definitions

Health disparity populations.

The framework applies to all health disparity populations. As defined by the US Office of Management and Budget, these include racial/ethnic minorities, socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, underserved rural populations, and sexual and gender minorities (which include lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and gender-nonbinary or gender-nonconforming individuals). We acknowledge and support the special emphasis placed by the NIMHD on the historical trauma experienced by American Indian groups that were displaced from their traditional lands and African-American populations that continue to endure the legacy of slavery. We additionally include a focus on individuals with disabilities, including those with limitations in their ability to see, see color, hear, etc., that might impact digital accessibility.

Digital environment

The digital environment is enabled by technology and digital devices, often transmitted over the internet, or other digital means, e.g., mobile phone networks. This includes digital communication, RPM, digital health sensors, telehealth, and the EHR. The digital environment includes elements of the physical/built environment, sociocultural practices, and understanding, as well as the habits and behaviors that dictate how we use these tools. The digital environment exists within and outside of the formal healthcare system.

Social determinants of health

SDoH are defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as “conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks” 13 . These social circumstances are responsible for health inequities as they are heavily shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources. The SDoH falls into five key categories: healthcare access and quality, education access and quality, social and community context, economic stability and the neighborhood, and the built environment. Determinants in the digital environment, including access, can significantly impact the SDoHs. For example, applications for employment, which influence an individual’s economic stability, are now almost exclusively accessible online.

Digital determinants of health

The DDoH are conditions in the digital environment that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality of life outcomes and risks. The DDoH includes access to technological tools, digital literacy, and community infrastructure like broadband internet and operates at the individual, interpersonal, community, and societal levels. They impact digital health equity, which is equitable access to digital healthcare, equitable outcomes from and experience with digital healthcare, and equity in the design of digital health solutions 10 , 12 .

Framework for digital health equity

National institute on minority health and health disparities (nimhd) research framework.

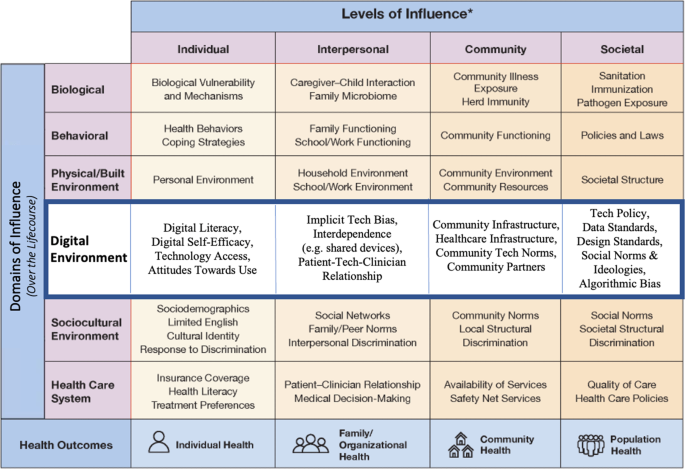

The framework for digital health equity is an expansion of the NIMHD Research Framework. This framework, published in 2019, is the culmination of decades of work in the field of health disparities 14 . The framework is organized into several domains, including biological, behavioral, physical/built environment, sociocultural environment, and the healthcare system. It categorizes domains of determinants according to levels of the socioecological model. The SDoH are included primarily in the physical/built environment, sociocultural environment, and the healthcare system domains. The NIMHD Research Framework was an adaptation of the National Institute on Aging (NIA) disparities model, where the healthcare system domain was added because of its particular importance to health. Similarly, because of its critical role in health and healthcare - we incorporate a digital environment domain.

The DDoH are incorporated into the NIMHD Research Framework within the digital environment domain (Fig. 1 ). Determinants are not intended to be exhaustive and often function in ways that are cumulative or interactive.

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities Research Framework Expanded for Digital Health Equity.

Individual-level determinants

Determinants at the individual level include digital literacy, digital self-efficacy, technology access, and attitudes towards use. Digital literacy refers to the skills and abilities necessary for digital access, including an understanding of the language, hardware, and software required to successfully navigate the technology 15 . Self-efficacy is the belief that one can surmount any problem through one’s own effort and is connected to a wide variety of desirable outcomes, including higher performance and achievement striving 16 , 17 . Digital self-efficacy is an individual’s self-efficacy with regard to the effective and effortless utilization of information technology and predicts proficiency 18 . Digital literacy contributes positively to but does not entirely account for an individual’s sense of digital self-efficacy 19 , 20 . Others have highlighted similar terms, such as digital confidence, as distinct from digital literacy and instrumental in establishing the digital agency, an individual’s ability to control and adapt to a digital world 20 .

Technology access describes the necessary technological equipment availability to an individual. Attitudes towards use include an individual’s desire and willingness to use, trust in, and beliefs about their ability to use digital tools. Attitudes towards use are adapted from theories of technology adoption such as the technology acceptance model (TAM) and include perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use which predict technology adoption 21 . Trust is also a key construct, as disparity populations can have unique concerns about privacy, security, and surveillance. These concerns can be exacerbated by factors that might be comforting to other groups, for example, affiliation with state or government institutions or the healthcare system. For example, African Americans are more likely than whites to distrust the medical system, report experiencing racism in it, and to express concern about threats to privacy from EHRs 22 , 23 , 24 .

Interpersonal level determinants

Determinants at the interpersonal level include implicit tech bias, interdependence, and the patient-tech-clinician relationship. These determinants describe relational factors that connect individuals to both digital health technologies and one another. Implicit bias is a term with growing use in the healthcare field, defined as associations outside conscious awareness that lead to a negative evaluation of a person. Implicit Tech Bias is used to describe the impact that unconscious perceptions of an individual’s digital literacy, technology access, and attitudes towards use have on clinician (and affiliated healthcare team members) willingness to enroll and engage individuals with digital healthcare tools. For example, disparity populations have been documented to be less likely to receive invitations to set up patient portal accounts by their clinicians 25 . These clinicians may have been attempting to select patients more likely to successfully use the portal, however implicit bias would have played a role in this assessment and may have contributed to unequal access. Interdependence is used to describe the dependence of two or more people (e.g., family members, caregivers, or friends) on each other for the digital skills, access, and equipment necessary to use digital health tools. For example, low-income households are more likely to share devices and to operate in connection with others 11 . Interdependence can be considered as a positive adaptive mechanism in many contexts, with these bonds serving as positive social capital and facilitating healthy behaviors for both individuals and larger group networks.

The Patient-Tech-Clinician relationship describes the complex interpersonal transformations encouraged by digital technologies, which impact power dynamics between individuals and can help address or exacerbate power imbalances in relationships. For example, the digitization of healthcare may democratize the relationship between the individual and clinician, transforming the paternalistic paradigm of medicine into an equal partnership through data access and transparency 26 . For disparity populations, this has the potential to impact well-documented dimensions of the patient-clinician relationship, including medical mistrust and poor quality communication.

Community level determinants

Determinants at the community level include community infrastructure, healthcare infrastructure, community tech norms, and community partners. Community infrastructure includes cellular wireless and broadband access, quality, and affordability. Broadband access is considered an important health determinant, access to which should be ensured by the Federal Communications Commission 9 . Digital redlining impacts access to patient portals, RPM, and telehealth 27 , 28 . Without broadband internet access, patients cannot fully use telehealth in all its forms: asynchronous messaging via patient portals, remote monitoring devices such as blood pressure monitors, or synchronous video connections to consult with a physician.

Healthcare infrastructure includes community access to health systems with advanced digital capabilities, including sophisticated EHR systems, patient portals, and telehealth tools like RPM and simultaneous audio-visual visits. Community tech norms include community preferences for particular tools (i.e., WeChat), high- vs. low-tech solutions, etc. These norms impact health outcomes based on how they compare or contrast with those of the dominant culture and are influenced by a variety of factors, including perceived utility and availability of certain features (e.g., language) which improve acceptability for specific communities. Community partners are an important contribution to the local digital equity ecosystem, the socio-technical systems that work to increase access, and include tech advocacy groups, community health workers, libraries, and digital literacy training programs.

Societal-level determinants

Determinants at the societal level include tech policy, data and design standards, social norms and ideologies, and algorithmic bias. Tech policy includes the federal, state, and local policies supporting healthcare technology adoption (i.e., HITECH), development and innovation (i.e., 21st Century Cures Act), and security (i.e., HIPAA, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act). Data standards are created and maintained by professional organizations, for example, Health Level Seven International produced Health Level Seven (HL7), Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), and others. The inclusion or exclusion of data relevant to certain populations in these standards impacts the ability of organizations to measure and monitor progress towards equity.

Design standards impact accessibility for those with disabilities and low digital health literacy. For example, Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) cover a wide range of recommendations for making Web content more accessible 29 . Recommendations include ensuring a high contrast ratio for colors, that text size can be increased by at least 200%, and not using color alone to convey information. Following these guidelines makes content accessible to a wider range of people with disabilities, including blindness and low vision, deafness and hearing loss, learning disabilities, cognitive limitations, limited movement, speech disabilities, photosensitivity, and combinations of these. Social norms and ideologies are the set of beliefs and philosophies that impact who develops digital tools, what is developed, how it is used, and who it is used by. For example, diffusion of innovation theory is widely adopted in the field and includes the assumption that technology should be developed for early adopters, typically those with excess time and resources, and these tools will eventually trickle down to the general population 30 , 31 . Other examples include the masculine coding of technology and our assumptions that these tools provide objectivity 32 .

Algorithmic bias includes bias in the use of machine learning and artificial intelligence as well as racial bias in health algorithms that do not use these advanced statistical and computational methodologies. The use of race correction in health algorithms has recently come under scrutiny for potentially contributing to health disparities 33 . For example, the Vaginal Birth After Cesarean Risk Calculator provides a lower estimate of the probability of vaginal birth after prior cesarean for individuals of African-American race or Hispanic ethnicity 34 . The health impact of this may be significant considering that women of color continue to have higher rates of cesarean section, the health benefits of vaginal deliveries are well known, including lower rates of surgical complications, and black women, in particular, have higher rates of maternal mortality 35 . The use of a calculator that lowers the estimate of the success of vaginal birth after cesarean for people of color could exacerbate these disparities.

An “upstream”, multi-level approach

We hope that the Framework for Digital Health Equity will encourage users and support them in developing an “upstream”, multi-level approach. Health disparities are the result of complex social, environmental, and structural forces. However, interventions in the field have suffered from the Fundamental Attribution Error—overweighting the impact of individual or personal factors and underweighting contextual or situational factors. Health disparities interventions almost always target individual determinants, less often targeting the interpersonal, community, or societal-level determinants 14 . Disparity populations are less likely to benefit from interventions focused on individual-level determinants, as barriers, including limited resources and competing priorities, are greater in these populations 36 , 37 . Interventions targeting “upstream” determinants at the community and societal levels (i.e., digital infrastructure) are more likely to be effective for these populations 38 , 39 .

In addition to targeting “upstream” DDoH, a multi-level approach that simultaneously targets the interdependence between the levels of influence can be effective as well. Disparity populations often face structural disadvantages at multiple mutually reinforcing levels 40 . For those studying the effects of such approaches, contemporary methods can provide information about causality at multiple levels as well as interaction effects. These contemporary methods include the sequential, multiple assignments, randomized trial (SMART), multi-level analysis, and the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) research framework. A multi-level approach allows us to discover the impact of targeting determinants that may be necessary to address to close disparities in outcomes but that are by themselves not sufficient for eliminating disparities.

Applying the framework for digital health equity: remote patient monitoring use case

The use of RPM, e.g., ambulatory, noninvasive digital technology to capture, and transmit patient data in real-time for care delivery and disease management, is an innovative digital health capability that is rapidly being embedded into our healthcare delivery system. It is increasingly being leveraged for the management of hypertension 41 , diabetes 42 , congestive heart failure 43 , chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 44 , and a range of other chronic conditions 45 . Established non-digital SDOH for RPM uptake include issues such as limited English proficiency (individual level, sociocultural environment domain), disparities in insurance coverage (individual level and healthcare system domain), preferences for social/community-oriented vs. individually driven care (interpersonal level and sociocultural environment domain), device safety and security issues (community level and behavioral domain) and staffing models of medical practices in underserved communities (societal level and healthcare system domain).

Digital health giants and startups now offer an expanding ecosystem of devices, platforms, and products supporting the scale-up of this new technology 46 . Following the usual diffusion of innovation paradigm, many of these offerings are targeting well-resourced settings and populations. However, the dissemination of RPM is early enough that there is an opportunity to use our emerging understanding of the DDoH to alter the usual diffusion curve and build RPM tools that can meaningfully engage health disparity populations. To facilitate this disruption, we highlight RPM digital health equity considerations for the digital health industry, clinical, community, and policy leaders to consider as they grow their RPM products and programs (Table 1 ).

We use RPM as a use case to demonstrate how this framework can be used to highlight opportunities to reshape how digital health is developed, deployed, and disseminated so that diverse communities have an equal opportunity to take advantage of the potential of new digital health technologies.

The rapid digital transformation of healthcare may contribute to increased inequality. Health interventions often lead to intervention-generated inequalities as they are typically adopted unevenly with disparity populations lagging behind 47 . Digital health is particularly vulnerable to this as interventions are likely to disproportionately benefit more advantaged people with greater access to money, power, and knowledge. Digital health leaders and developers in industry, academia, and healthcare operations must be aware of the DDoH and the roles they play to ensure that the use of technology does not widen disparities.

We expand the NIMHD Research Framework to incorporate a digital environment domain detailing key DDoH. Currently, there is no comprehensive framework for digital health equity that addresses determinants at all levels and provides context with the SDoHs. Without an understanding of the DDoHs in context, digital health solution development and research may result in tools and knowledge that are incomplete as they do not address the cumulative or interactive effects of multiple domains. Notably, the framework includes both risk and resilience factors which is key as we support a strengths-based approach to development.

Digital health stakeholders concerned with equity and impact should consider the DDoHs in product development and intervention design and dissemination, incorporating community and societal-level determinants as well as developing multi-level approaches. By expanding the leading health disparities research framework for digital health equity, we hope digital health leaders in the industry, academia, policy, and the community will benefit from decades of progress in the field of health disparities as well as see their work in the larger context of SDoHs so that we might work together towards meaningful progress in using digital means to achieve health equity for all.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Smedly, B.D. et al. Organizational context and provider perception as determinants of mental health service use. J. Behav. Health Serv. Res. 28 , 188–204 (2001).

Article Google Scholar

Jones, C. P. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am. J. Public Health 90 , 1212 (2000).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Krieger, N. Does racism harm health? Did child abuse exist before 1962? On explicit questions, critical science, and current controversies: an ecosocial perspective. Am. J. Public Health 93 , 194–199 (2016).

Braveman, P. & Gruskin, S. Defining equity in health. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 57 , 254–258 (2003).

Technology, TOotNCfHI. Health IT Dashboard.

Chunara, R. et al. Telemedicine and healthcare disparities: a cohort study in a large healthcare system in New York City during COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 28 , 33–41 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Litchfield, I., Shukla, D. & Greenfield, S. Impact of COVID-19 on the digital divide: a rapid review. BMJ Open 11 , e053440 (2021).

Dixit, N. et al. Disparities in telehealth use: How should the supportive care community respond? Support. Care Cancer 30 , 1007–1010 (2022).

Ramsetty, A. & Adams, C. Impact of the digital divide in the age of COVID-19. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 27 , 1147–1148 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lyles, C. R., Wachter, R. M. & Sarkar, U. Focusing on digital health equity. JAMA 326 , 1795–1796 (2021).

Sieck, C. J. et al. Digital inclusion as a social determinant of health. NPJ Digit. Med. 4 , 1–3 (2021).

Crawford, A. & Serhal, E. Digital health equity and COVID-19: the innovation curve cannot reinforce the social gradient of health. J. Med. Internet Res. 22 , e19361 (2020).

Prevention, C.F.D.C.A. Social determinants of health: know what affects health. https://www.cdc.gov/socialdeterminants/about.html (2022).

Alvidrez, J. et al. The national institute on minority health and health disparities research framework. Am. J. Public Health 109 , S16–S20 (2019).

Jaeger, P. T. et al. The intersection of public policy and public access: digital divides, digital literacy, digital inclusion, and public libraries. Public Libr. Q. 31 , 1–20 (2012).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 84 , 191 (1977).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. Am. Psychol. 37 , 122 (1982).

Agarwal, R., Sambamurthy, V. & Stair, R. M. The evolving relationship between general and specific computer self-efficacy—An empirical assessment. Inf. Syst. Res. 11 , 418–430 (2000).

Prior, D. D. et al. Attitude, digital literacy and self efficacy: Flow-on effects for online learning behavior. Internet High. Educ. 29 , 91–97 (2016).

Passey, D. et al. Digital agency: empowering equity in and through education. Technol. Knowl. Learn. 23 , 425–439 (2018).

Davis, F. Technology Acceptance Model For Empirically Testing New End-user Information Systems : Theory and Result . PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. (1986).

LaVeist, T. A., Nickerson, K. J. & Bowie, J. V. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med. Care Res. Rev. 57 , 146–161 (2000).

Women, N.P.f. and Families. Engaging Patients and Families: How Consumers Value and Use Health IT (National Partership for Women and Families, 2014).

Walters, N. Maintaining Privacy and Security While Connected to the Internet (Washington, DC: AARP Public Policy Institute, 2017).

Ancker, J. S. et al. Use of an electronic patient portal among disadvantaged populations. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 26 , 1117–1123 (2011).

Meskó, B. et al. Digital health is a cultural transformation of traditional healthcare. Mhealth . 3 , 38 (2017).

Merid, B., Robles, M. C. & Nallamothu, B. K. Digital redlining and cardiovascular innovation. Circulation 144 , 913–915 (2021).

Perzynski, A. T. et al. Patient portals and broadband internet inequality. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 24 , 927–932 (2017).

Caldwell, B. et al. Web content accessibility guidelines (WCAG) 2.0. WWW Consort. (W3C) 290 , 1–34 (2008).

Google Scholar

Dearing, J. W. & Cox, J. G. Diffusion of innovations theory, principles, and practice. Health Aff. 37 , 183–190 (2018).

Dolezel, D. & McLeod, A. Big data analytics in healthcare: investigating the diffusion of innovation. Perspect. Health Inf.Manag . 16 , 1a (2019).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Agre, P. E. Cyberspace as American culture. Sci. Cult. 11 , 171–189 (2002).

Vyas, D. A., Eisenstein, L. G. & Jones, D. S. Hidden in plain sight-reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N. Engl. J. Med . 383 , 874–882 (2020).

Grobman, W. A. et al. Development of a nomogram for prediction of vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 109 , 806–812 (2007).

Vyas, D. A. et al. Challenging the use of race in the vaginal birth after cesarean section calculator. Women’s Health Issues 29 , 201–204 (2019).

White, M., Adams, J. & Heywood, P. How and why do interventions that increase health overall widen inequalities within populations. Soc. Inequal. Public Health 65 , 82 (2009).

McLaren, L., McIntyre, L. & Kirkpatrick, S. Rose’s population strategy of prevention need not increase social inequalities in health. Int. J. Epidemiol. 39 , 372–377 (2010).

Lorenc, T. et al. What types of interventions generate inequalities? Evidence from systematic reviews. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 67 , 190–193 (2013).

Beauchamp, A. et al. The effect of obesity prevention interventions according to socioeconomic position: a systematic review. Obes. Rev. 15 , 541–554 (2014).

Subramanian, S. V., Acevedo-Garcia, D. & Osypuk, T. L. Racial residential segregation and geographic heterogeneity in black/white disparity in poor self-rated health in the US: a multilevel statistical analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 60 , 1667–1679 (2005).

Logan, A. G. et al. Mobile phone–based remote patient monitoring system for management of hypertension in diabetic patients. Am. J. Hypertension 20 , 942–948 (2007).

Lee, P. A., Greenfield, G. & Pappas, Y. The impact of telehealth remote patient monitoring on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18 , 1–10 (2018).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Sohn, A. et al. Assessment of heart failure patients’ interest in mobile health apps for self-care: survey study. JMIR Cardio 3 , e14332 (2019).

Walker, P. P. et al. Telemonitoring in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (CHROMED). A randomized clinical trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 198 , 620–628 (2018).

Walker, R. C. et al. Patient expectations and experiences of remote monitoring for chronic diseases: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Int. J. Med. Inform. 124 , 78–85 (2019).

Dinh-Le, C. et al. Wearable health technology and electronic health record integration: scoping review and future directions. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 7 , e12861 (2019).

Veinot, T. C., Mitchell, H. & Ancker, J. S. Good intentions are not enough: how informatics interventions can worsen inequality. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 25 , 1080–1088 (2018).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant K23HL145114 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York City, NY, USA

Safiya Richardson, Katharine Lawrence, Antoinette M. Schoenthaler & Devin Mann

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

S.R., K.L., A.S., and D.M. made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, the drafting and/or critical revision for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Safiya Richardson .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Richardson, S., Lawrence, K., Schoenthaler, A.M. et al. A framework for digital health equity. npj Digit. Med. 5 , 119 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-022-00663-0

Download citation

Received : 04 March 2022

Accepted : 25 July 2022

Published : 18 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-022-00663-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Navigating the doctor-patient-ai relationship - a mixed-methods study of physician attitudes toward artificial intelligence in primary care.

- Matthew R. Allen

- Sophie Webb

- Gene Kallenberg

BMC Primary Care (2024)

Navigating the digital world: development of an evidence-based digital literacy program and assessment tool for youth

- M. Claire Buchan

- Jasmin Bhawra

- Tarun Reddy Katapally

Smart Learning Environments (2024)

“Systems seem to get in the way”: a qualitative study exploring experiences of accessing and receiving support among informal caregivers of people living with chronic kidney disease

- Chelsea Coumoundouros

- Paul Farrand

- Joanne Woodford

BMC Nephrology (2024)

Interventions to enhance digital health equity in cardiovascular care

- Ariana Mihan

- Harriette G. C. Van Spall

Nature Medicine (2024)

The Role of Human-Centered Design in Healthcare Innovation: a Digital Health Equity Case Study

- Ximena A. Levander

- Hans VanDerSchaaf

- Anthony Cheng

Journal of General Internal Medicine (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Feature Article

- Epidemiology and Global Health

Science Forum: Adding a One Health approach to a research framework for minority health and health disparities

- Mariana C Stern

- Eliseo J Pérez-Stable

- Monica Webb Hooper

- Department of Public Health Sciences, University of California, Davis, United States ;

- Center for Animal Disease Modeling and Surveillance (CADMS), Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, United States ;

- Departments of Preventive Medicine and Urology, Keck School of Medicine of USC, United States ;

- Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of Southern California, United States ;

- Office of the Director, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health, United States ;

- Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of California, Davis, United States ;

- Open access

- Copyright information

- Comment Open annotations (there are currently 0 annotations on this page).

- 1,011 views

- 150 downloads

- 2 citations

Share this article

Cite this article.

- Brittany L Morgan

- Laura Fejerman

- Copy to clipboard

- Download BibTeX

- Download .RIS

- Figures and data

Introduction

Health disparities and one health, health disparities and covid-19, the expanded framework, conclusions, data availability, decision letter, author response, article and author information.

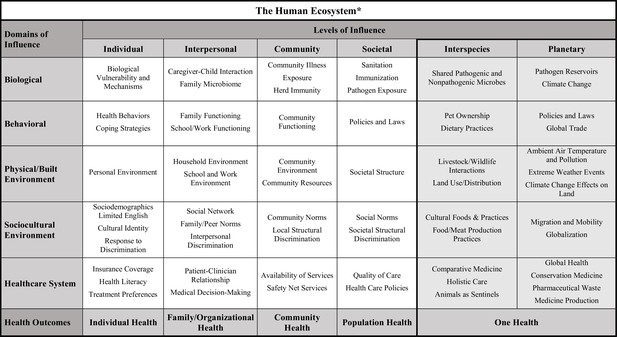

The National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) has developed a framework to guide and orient research into health disparities and minority health. The framework depicts different domains of influence (such as biological and behavioral) and different levels of influence (such as individual and interpersonal). Here, influenced by the “One Health” approach, we propose adding two new levels of influence – interspecies and planetary – to this framework to reflect the interconnected nature of human, animal, and environmental health. Extending the framework in this way will help researchers to create new avenues of inquiry and encourage multidisciplinary collaborations. We then use the One Health approach to discuss how the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated health disparities, and show how the expanded framework can be applied to research into health disparities related to antimicrobial resistance and obesity.

Research frameworks are useful because they allow important problems to be tackled from many different directions and perspectives ( Mills et al., 2010 ) For the individual researcher, a framework can help with the formulation of research questions and situate their research in a broader context. Research frameworks are also useful to funding agencies: for example, the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) in the United States employs a research framework to assess the state of current research and to identify gaps and opportunities for funding ( Alvidrez et al., 2019 ).

The NIMHD framework has two axes: the vertical axis lists five “domains” that influence minority health and health disparities (biological, behavioral, physical/built environment, sociocultural environment, and healthcare system), while the horizontal axis lists four “levels of influence” (individual, interpersonal, community, and societal). The model builds on a framework for research into health disparities that was developed by the National Institute on Aging, ( Hill et al., 2015 ) and also on the socioecological model ( Bronfenbrenner, 1977 ; Kilanowski, 2017 ).

The NIMHD encourages using the research framework to examine the interaction of factors from different domains and levels to understand health disparities. Investigators can use the framework while conducting their literature review to map and organize study findings and identify gaps in knowledge. Then, they can formulate research questions and define theories and models evaluating the influence of factors from several levels and domains. For example, the NIMHD has used the framework to evaluate disparities by racial/ethnic category in lung cancer mortality by identifying factors from three domains and levels of influence. Specifically, genetic risk is highlighted as a determinant in the biological domain and at the individual level, while access to quality treatment is an influence in the healthcare system domain and at the community level. Moreover, the framework facilitates considerations of the influence of structural racism on health disparities: differences in state laws, cigarette taxes, social norms, and smoking bans affect racial and ethnic category disparities through the behavioral domain and the societal level ( Alvidrez et al., 2019 ). The framework highlights the complex nature of minority health and health disparities, and the need to consider multiple domains and levels of influence when trying to understand these areas and change them for the better (see Box 1 for definitions of minority health and other terms used in this article).

Definitions.

Minority health: Aspects of health and disease among racial and ethnic category minority populations as defined by the US Census.

Health disparity: A preventable difference in health outcomes that adversely affects socially and/or economically disadvantaged populations. These populations include racial and ethnic category minority groups, persons of less privileged socioeconomic status, underserved rural residents, and sexual and gender minorities; all share a social disadvantage in part due to having been subject to discrimination or racism.

One Health: An approach recognizing the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment; the health of one affects the health of all. One Health is a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach to understanding and managing health in a wholistic way that prioritizes ecosystem balance.

Human ecosystem: Combines components of the ecosystem traditionally recognized by ecologists (plants, animals, microbes, physical environmental complex) with the built environment and social characteristics, structures, and interactions of interest.

Research framework: A structure supporting collective scientific endeavours by guiding the development and investigation of a research question and conceptualizing the relationship between relevant factors.

The importance of merging aspects of environmental health with health equity has long been highlighted by the World Health Organization. In 2008, for example, the Commission on Social Determinants of Health stressed the impact of climate change on the health of individuals and the planet ( Gama and Colombo, 2010 ). Increasingly, studies show that biological, cultural and environmental factors – and interactions between these factors – are all relevant to research into health disparities, ( van Daalen et al., 2020 ; Garnier et al., 2020 ; Mueller et al., 2018 ) and the COVID-19 pandemic has increased focus on the human-animal-environment interface ( de Garine-Wichatitsky et al., 2020 ). However, it is challenging to include the impact of environmental factors and human-animal linkages on health disparities in the NIMHD framework, so we are proposing to expand the framework by adding two new levels of influence – interspecies and planetary – and making use of the “One Health” approach to thinking about the emergence and prevention of disease. ( CDC, 2020a ) This expansion allows researchers to build on the biological and social determinants of health, and their root causes such as structural racism, already explored in the NIMHD framework. The two new levels of influence explicitly frame questions that link interspecies factors (i.e., the interactions between the human host and their microbiome or animal and human shared infections) and planetary factors (i.e., rising temperatures or global food production practices) with those stemming from biological, social, cultural, and structural and explore their combined impact on health and disease.

The One Health approach involves multiple health science professions collaborating to attain optimal health for people, other animals, and the environment ( Schneider et al., 2019 ). The One Health approach has primarily been adopted to investigate and prevent the spread of infectious and zoonotic diseases.( Kelly et al., 2020 ; Schmiege et al., 2020 ). For several endemic, zoonotic diseases, One Health approaches targeting animal or environmental reservoirs of infection have proven more equitable than interventions focusing on clinical management of disease, which can be inaccessible for disadvantaged and poor communities. In Latin America, for example, modest investments in mass dog vaccinations have effectively prevented rabies-related death in humans and resulted in near elimination of the virus from the community ( Vigilato et al., 2013 ). This approach has been more effective, and equitable, than increased expenditures in the administration of post-exposure prophylaxis, which has been emphasized in many Asian countries where there is still high incidence of human rabies cases ( Cleaveland et al., 2017 ).

Human health is linked to non-human animal health in many ways: some of these links are direct (e.g., food consumption) and some are indirect (e.g., via the environment), and many of these links are not fully understood ( Davis and Sharp, 2020 ; Wolf, 2015 ). Differences in the frequency of human-animal interactions among population groups, ( Rabinowitz and Conti, 2013 ) individual and cultural food practices, ( Wolfe et al., 2005 ; Kamau et al., 2021 ) livelihood systems, ( Woldehanna and Zimicki, 2015 ) and livestock production practices ( Edwards-Callaway, 2018 ; Ducrot et al., 2008 ) could lead to health disparities. These relationships are particularly relevant for populations such as farmworkers, ( Pol et al., 2021 ) people experiencing homelessness, ( Hanrahan, 2019 ) individuals living in agricultural communities, ( Wing and Wolf, 2000 ) and certain racial and ethnic category minorities. For example, individuals with high fish diets have the potential for increased exposure to harmful contaminants influenced by waterway pollutants, marine food webs, and climate change ( Gribble et al., 2016 ). The unequal distribution of pollutants is a matter of environmental racism, and this interacts with other social and structural factors disproportionately impacting impoverished communities and communities of color. This may be particularly relevant among Native American and Pacific Islander communities who consume fish at higher rates than other subpopulations ( Washington State Department of Ecology, 2013 ). There is limited research in the area, but evidence of elevated blood mercury among these groups ( Hightower et al., 2006 ) could lead to health disparities stemming from a complex association between environmental justice, climate change, systemic racism, and this interspecies relationship ( CDC, 2021b ). The NIMHD framework does not easily facilitate consideration of these determinants.

There is a bidirectional relationship between human and environmental health, and the NIMHD framework includes the physical/built environment as a domain of influence. However, the natural environment and climate change can also influence health disparities. For example, extreme weather events or changes to the natural environment can disproportionately impact segments of the population based on geography and access to resources. In the Western part of the United States, the increasing number, size, and intensity of wildfire events occurring due to extreme heat and drought may disproportionately impact nearby populations through displacement or prolonged exposure to smoke, worsening or creating new populations with health disparities ( US EPA, 2017a ). Further, climate change impacts on health, environmental pollutants, habitat loss, biological diversity, and the distribution of resources, disproportionately impact poor people and populations of color, and can drive or exacerbate health disparities ( van Daalen et al., 2020 ; Huong et al., 2020 ; Hinchliffe et al., 2021 ).

As an example of the interconnectedness of plant and human health, consider a mycotoxin called aflatoxin that is produced by common fungi and may play a causative role in hepatocellular carcinoma ( Ramirez et al., 2017 ). Hepatocellular carcinoma disproportionately affects Latinos, and aflatoxin commonly affects corn and maize crops, considered a Latin American dietary staple ( Overcash and Reicks, 2021 ). Climate change impacts on temperature and drought increase aflatoxin levels in crops and could exacerbate hepatocellular carcinoma disparities among populations relying on the health and safety of those crops ( Kebede et al., 2012 ).

The complexity of the linkages humans have with each other, with non-human species, and with the environment should be incorporated with the exploration of social systems and structural racism to understand or model health outcomes and subsequent health disparities ( Craddock and Hinchliffe, 2015 ). We believe adding elements of the One Health approach to the NIMHD framework will help expand health disparities research, open new avenues of inquiry for both One Health and health disparities researchers, and promote multidisciplinary collaborations, all of which should lead to broader and more sustainable solutions to health disparities. Using the COVID-19 pandemic as a motivating example, we will use the One Health approach to identify new determinants of health disparities not easily incorporated in the original NIMHD framework. We will then present an expanded research framework and show how this new framework can be used to think about health disparities in the fields of infectious diseases (using antimicrobial resistance as an example) and non-communicable diseases (using obesity as an example).

While the One Health approach and the NIMHD framework are already being used by researchers, the work is conducted in disciplinary silos. One Health researchers may not see how they can help inform and address health disparities or how they can begin incorporating social and structural systems in their work ( Craddock and Hinchliffe, 2015 ; Solis and Nunn, 2021 ). Health disparities researchers may not consider the influence of the broader human ecosystem and its interactions with social, cultural, and structural systems. We hope that the expanded research framework will highlight the overlap in their work and stimulate new areas of research and thinking. It is important to note the relationships presented throughout are theoretical and meant to be illustrative of the hypothesis generating potential of the expanded framework, not an assumption of causal relationships or a replacement for exploring the complex social and structural systems creating health disparities. Further, although the NIMHD research framework focuses on minority health and health disparities in the United States, we will discuss how it might also apply to other countries.

The disproportionate impact COVID-19 has had on some racial and ethnic category minority populations, and on people with low economic resources, has re-centered conversations concerning health disparities. Those with underlying medical conditions (such as diabetes, heart disease, and chronic lung disease) have also been strongly overrepresented in case severity and fatalities ( Burch and Searcey, 2020 ; Kim et al., 2020 ). Marginalized communities already impacted by health disparities are also disproportionately affected by these conditions, increasing the harm caused by COVID-19 ( Kim et al., 2020 ; Lopez et al., 2021 ). Several of the factors that contribute to COVID-19 health disparities are accounted for in the NIMHD framework (such as structural racism and its impact on neighborhood and built environment characteristics, healthcare access, occupation and workplace conditions, income, and education CDC, 2020b ). The One Health approach allows factors not easily accounted for in the NIMHD framework (such as disproportionate access to natural resources like clean air, drinking water, potable water for sanitation and hygiene, and nutritious foods) to be considered ( Garnier et al., 2020 ).

The WHO has classified COVID-19 as a zoonotic disease ( WHO, 2020 ). While an animal reservoir has not yet been identified, ( Haider et al., 2020 ) most zoonotic diseases are thought to enter human populations through a spill-over event originating from human-animal exposure. Unlike some zoonotic diseases, COVID-19 does not require a non-human animal host for pathogen persistence. The disease may have originated in animals and then independently persisted in human populations through respiratory transmission ( Singla et al., 2020 ; Jayaweera et al., 2020 ; Meyerowitz et al., 2021 ).

Epidemics of zoonotic origin can be triggered by changes in human and non-human animal reservoirs’ interaction dynamics. Environmental, climatic, socio-economic, and habitat or animal abundance changes can modify the probability of human and non-human animal interactions. And as the rate of such interactions increases, so does the rate at which respiratory viruses and other infectious agents evolve and adapt to their new hosts ( Duffy, 2018 ). Understanding the drivers of non-human animal and environmental exposures can build on social and systemic factors by incorporating human-animal linkages and planetary health to deepen our understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic and related health inequities. This improved understanding may strengthen our capacity to prevent and better predict the course of future pandemic threats.

Disease transmission between humans and non-human animals is a primary focus of the One Health approach. Previous coronavirus outbreaks exemplify the ways human interactions with non-human animals can increase viral exposure. Human invasion of the natural environment, contact with livestock, rodents, shrews, or bats, as well as the consumption of rare and wild non-human animals, contributes to infection with viruses we normally would not encounter ( Li et al., 2019 ). For COVID-19, exposure to bridge hosts (the species that transmit viruses to humans from their natural reservoirs) may be a predictor of viral exposure early in the outbreak ( Solis and Nunn, 2021 ). Hypothesized COVID-19 bridge hosts include animals in animal markets or domesticated animals and livestock ( El Zowalaty and Järhult, 2020 ). High rates of exposure to wildlife and livestock is an identified predictor of COVID-19 exposure in China, mainly between poultry and rodents/shrews in living dwellings ( Li et al., 2019 ). Viral reservoirs and bridge hosts exposures are associated with less economic resources, inadequate housing and impoverished neighborhoods (i.e., stagnant water, animals residing in dwellings, uncollected trash, and overgrown lots), adding potential mediating factors to determinants of health identified in the NIMHD framework ( Solis and Nunn, 2021 ). There are also many aspects of COVID-19 related to minority health and health disparity that we are unable to discuss in detail for reasons of space: these include the impact of the human-animal bond on COVID-19 mental health outcomes, ( Shim, 2020 ; Saltzman et al., 2021 ; Brooks et al., 2018 ; Ratschen et al., 2020 ) the influence of environmental factors (notably temperature, humidity, and atmospheric pollution) on morbidity, ( Ratschen et al., 2020 ; Chin et al., 2020 ; Ma et al., 2020 ; Conticini et al., 2020 ) and questions related to vaccine equity ( Katz et al., 2021 ).

Experts agree that COVID-19 will not be the last pandemic ( Gill, 2020 ). Learning from our successes and mistakes during this pandemic will be crucial to prepare appropriately. COVID-19 highlights the importance of considering how the relationships between humans, non-human animals, and the environment affect minority health and contribute to health disparities. Expanding the NIMHD framework to explicitly include determinants from these domains can help us foresee and better respond to future, global threats by expanding our view of health determinants and drivers of disparities. We believe this is best achieved by incorporating a One Health approach in the NIMHD framework. Recently, a One Health Disparities framework was introduced for zoonotic disease researchers to incorporate the ways the social environment relates to disparities in disease exposure, susceptibility, and expression ( Solis and Nunn, 2021 ). Alternatively, we are proposing an expanded NIMHD framework as a way for health disparities researchers to explicitly include determinants stemming from human-animal and human-environmental linkages in their work. The relevance of this expansion will become even more clear heading into the future. As globalization increases, climate change progresses, and population growth continues to strain the relationship between humans, non-human animals, and the environment, thinking about health and health disparities in this holistic way will be essential.

Our proposed expansion involves adding two new levels of influence from the One Health approach – the interspecies and planetary levels – to the NIMHD framework ( Figure 1 ). The interspecies level covers the interplay, interconnectedness, and interdependencies of humans and non-human species ( Davis and Sharp, 2020 ). The definition of interspecies is kept as broad as possible to allow room for new areas of inquiry and flexibility in adapting the framework. The planetary level includes the Earth’s natural systems, resources, and biodiversity ( Lerner and Berg, 2017 ). Adding these two new levels promotes the evaluation of health disparities mechanisms across disciplines by introducing aspects of the human ecosystem previously missing from the NIMHD framework.

Proposed expansion of the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD) research framework.

The NIMHD research framework includes five domains (rows) and four levels (columns) that influence minority health and health disparities. The proposed expansion of the framework introduces two new levels of influence – the interspecies level and the planetary level (both shaded in grey). The new framework reflects how human health is a product of the human ecosystem, which combines traditionally recognized ecosystem components (plants, animals, microbes, physical environmental complex) with the built environment and social characteristics, structures, and interactions between all these elements. The figure shows examples of some of the factors that are relevant at the intersection between each domain and each level. The origins of the two new levels lie in the “One Health” approach, which recognizes that the health of people is closely connected to the health of animals and our shared environment. The bottom row of the framework demonstrates that health outcomes can also span multiple levels – individual, family and organizational, community, population, and, in the expanded framework, One Health.

Just as the interpersonal level in the present framework explores human-human interactions, the new interspecies level explores relationships between humans and non-human species across all five domains of influence. Examples of such relationships include microbes shared between humans and non-human animals (i.e., the biological domain), ( Trinh et al., 2018 ) pet ownership (behavioral), ( Mueller et al., 2018 ) livestock and wildlife interactions (physical/built environment), ( Hemsworth, 2003 ) food production practices (sociocultural environment), ( Edwards-Callaway, 2018 ; Ducrot et al., 2008 ) and comparative medicine, a discipline that synergizes health research in human and non-human animal medicine (healthcare system) ( Center for Veterinary Medicine, 2021 ).

In the present framework, the societal level of influence includes the presence and actions of governmental and civil society organizations at different levels (such as state, country, or region), ( Alvidrez et al., 2019 ) and the new planetary level of influence adds considerations of globalization and impacts of the natural environment. Examples include the effects on minority health and health disparities of climate change (i.e., the biological domain), ( US EPA, 2017b ) global trade (behavioral), ( Friel et al., 2015 ) ambient air temperature and pollution (physical/built environment), ( Son et al., 2019 ; Yi et al., 2010 ; Schifano et al., 2013 ) migration and mobility (sociocultural environment), ( Castañeda et al., 2015 ) global health programs, and the global system for producing medicines and medical devices (healthcare system) ( Newman and Cragg, 2020 ). More examples are given in Figure 1 (but please note that these examples are not meant to be comprehensive or to imply causal inference).

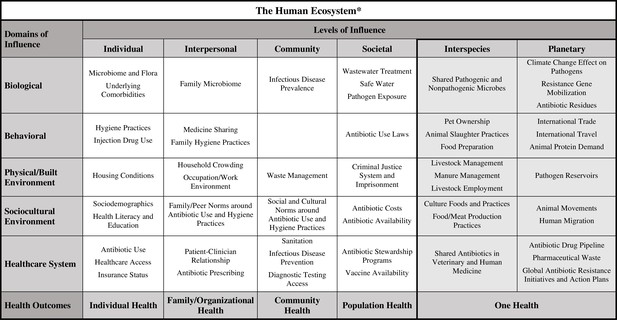

Example: Antimicrobial resistance

We will now show how the expanded framework can be applied to research into health disparities in two areas: antimicrobial resistance (AMR) ( Figure 2 ) and obesity. The problem of AMR is primarily driven by antibiotic overuse and misuse in humans, non-human animals, and the environment. Moreover, the interconnected nature of AMR means that it has already been studied by One Health researchers, ( McEwen and Collignon, 2018 ; Robinson et al., 2016 ) which makes it a promising candidate for the expanded NIMHD framework. There are documented disparities by racial and ethnic category in antibiotic use and AMR infections in the US ( Olesen and Grad, 2018 ; Hota et al., 2007 ; Iwamoto et al., 2013 ). There are also known occupational disparities in AMR pathogen exposure, with those in the agricultural and medical fields being at increased risk ( Fynbo and Jensen, 2018 ; Voss et al., 2005 ). Racial/ethnic category minority individuals, such as African American/Black and Hispanic/Latino, are more likely to work in these industries due to a combination of government policies and laws, and the unequal distribution of income and resources ( Division of Labor Force Statistics, 2020 ).

Expanded framework applied to health disparities research in antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

An example of how the expanded framework can be utilized by investigators as they develop their research questions and study designs for research into disparities related to AMR and AMR-related infections. The factors listed under the interspecies and planetary levels of influence are included in a more straightforward and systematic way than they would be in the original NIMHD framework.

Under the NIMHD framework, the domain/level of influence combinations relevant to AMR disparities could include housing conditions (individual/physical plus built environment), antibiotic sharing among family and peers and access to medications without prescriptions (interpersonal/behavioral), and antibiotic prescribing practices (interpersonal/healthcare system). However, there are other potential sources of health disparities related to AMR that are not accommodated by the NIMHD framework. By encouraging the consideration of interactions between humans and other species through the inclusion of an interspecies level, the expanded framework will enable the identification of some of these factors. One example might be antibiotic sharing between humans and non-human animals (i.e., the healthcare domain). Further, humans and non-human animals share and exchange pathogenic and non-pathogenic bacteria (i.e., the biological domain). A third example is that individuals living in rural and agricultural communities are disproportionately impacted by environmental exposures associated with nearby livestock and manure management practices (i.e., the physical/built environment domain). Additionally, while the evidence on whether livestock raised with antibiotics have higher levels of AMR than those raised without antibiotics is mixed, and we test animal products for antibiotic residues in the US, this is not necessarily true for the rest of the world ( Vikram et al., 2018 ; Van Boeckel et al., 2019 ).

Since antibiotic-free meat is often cost-prohibitive for those with low socioeconomic status, consumption of livestock raised with antibiotics in countries with fewer regulations may be important to consider when exploring AMR disparities by income, geography, or race/ethnicity category. The interspecies level of influence explicitly frames human exposure to non-human species in the home, workplace, or environment as relevant determinants of health disparities related to AMR.

Globalization and climate change are also highly relevant when considering AMR, and the planetary level of influence in the expanded framework allows these factors to be considered straightforwardly and clearly. International trade and travel (i.e., the behavioral domain) transfer bacteria and viruses across borders through the import and export of organic materials and human movement. These could be significant determinants to consider as certain immigrant populations in the US frequently travel to their native countries, many of which have a high prevalence of AMR infections ( Nadimpalli et al., 2021 ; Ruppé et al., 2018 ). The planetary level is also relevant to the challenge of dealing with pharmaceutical waste. How we manage such waste (i.e., the healthcare system domain), and how such waste is distributed, could be associated with socioeconomic status, putting those of lower status at increased risk for exposure to antibiotic residues (biological domain) and pathogen reservoirs (physical/built environment domain).

The risk factors for AMR are well documented, but our understanding of the combination of factors and interactions that contribute to disparities in AMR is limited ( Holmes et al., 2016 ). Including the planetary level of influence in the expanded framework highlights the need for multidisciplinary research that considers the interplay between humans, biodiversity, and the environment ( Venkatasubramanian et al., 2020 ). For example, environmental scientists could collaborate on studies evaluating geographic disparities in AMR that explore the possible impact of climate change on the abiotic environment in which people live (i.e., the planetary level/biological domain), and how the effect of this relationship disproportionately impacts segments of the population based on socioeconomic status. While there is no direct evidence of climate change impacts to the abiotic environment leading to disparities in AMR, the expanded framework allows such possibilities to be explored.

Example: Obesity

Obesity, defined by a body mass index above 30 kg/m 2 , is a major public health concern due to its contribution to several leading causes of disability and death, including diabetes, heart disease, stroke, osteoarthritis, and cancer ( CDC, 2021a ). Obesity affects people in every country worldwide and the prevalence is increasing, making it classifiable as a pandemic ( Swinburn et al., 2019 ). This pandemic results from a number of factors, including urbanization, global trade, and easy access to inexpensive caloric-dense food, ( Swinburn et al., 2019 ) and disparities in obesity are evident by geography, gender, age, and socioeconomic status, as well as race and ethnicity categories ( Hill et al., 2014 ; Wang and Beydoun, 2007 ). Solutions to the growing obesity pandemic will, therefore, require a multifaceted understanding of all these factors and the interactions between them.

The NIMHD framework facilitated our thinking about long-standing structural racism and how racial residential segregation, inequitable access to healthy and affordable food, and reduced opportunities for a healthy lifestyle lead to obesity-related health disparities ( Bleich and Ard, 2021 ). Behaviors contributing to these disparities may include physical activity and diet (i.e., the individual level/behavioral domain), cheap pricing of low nutritional value foods (the societal level/behavioral domain), targeted marketing or advertising (societal level/sociocultural environment domain) and the distribution of full-service grocery stores, convenience stores, and fast-food restaurants that results from societal level factors such as systemic racism affecting zoning laws and lending practices (community level/physical plus built environment domain) ( Petersen et al., 2019 ). We believe the expanded framework ( Figure 3 ) can build on these efforts, broaden the scope of health disparities research in obesity, and foster collaboration among researchers from different disciplines.

Expanded framework applied to health disparities research in obesity.

An example of how the expanded framework can be utilized by investigators as they develop their research questions and study designs for research into disparities related to obesity. The factors listed under the interspecies and planetary levels of influence are included in a more straightforward and systematic way than they would be in the original NIMHD framework.

For example, emerging data shows changes to our microbiome, a non-human species living within us, can affect our health, and obesity ( Feng et al., 2020 ). Social, economic, and environmental factors are likely to modify the microbiome over time, resulting in poor health outcomes ( Findley et al., 2016 ). Thus, changes to the microbiome may be an important mediator or modifier in studies evaluating the relationship between social factors and obesity among socially disadvantaged communities.

The expanded framework could also guide disparities research in new directions. For example, two zoonotic viruses – avian adenovirus (SMAM-1) and adenovirus 36 (Adv36) – are associated with obesity in both humans and non-human animals ( Ponterio and Gnessi, 2015 ). There is some evidence for racial/ethnic category and geographic differences in Adv36 seropositivity, but research in this area (at the intersection between the interspecies level and the biological domain) is limited ( Tosh et al., 2020 ; LaVoy et al., 2021 ). Finally, the expanded framework can also facilitate multidisciplinary collaboration. For example, there is a correlation between obesity in dogs and obesity in their owners: ( Bjørnvad et al., 2019 ) this suggests that public health professionals could work with veterinarians to disseminate health and educational information regarding pets and owners. This type of approach has the bonus of potentially reaching marginalized populations who may mistrust the medical system, lack health insurance, or participate in alternative medicine practices (and are therefore missed by the traditional routes for disseminating health information). Previous studies have successfully improved access to vital services among some of the highest-risk populations, such as those experiencing homelessness, by leveraging the human-animal bond and providing healthcare services through a One Health model ( Panning et al., 2016 ).

The Lancet Commission on Obesity deems climate change effects on health a pandemic, and emphasizes how interconnected it is with the obesity pandemic. Efforts to address disparities in obesity could be strengthened by considering the links between the two pandemics and exploring the influence of planetary factors on disparities. Questions for researchers to address would include: how do increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide affect crop nutritional quality, and how do rising temperatures disproportionately impact the geographic distribution of food crops, thermogenesis, and food insecurity? And what are the impacts of anthropogenic changes to the environment (such as urbanization or increased air pollution) and the increasing global demand for food? With regard to disparities, it will be important to explore how climate change disproportionately impacts individuals of low socioeconomic status through food insecurity, reduced opportunities for physical activity or metabolic processes. For example, rising atmosphere air temperature is associated with less adaptive thermogenesis, the complex metabolic process by which humans burn energy to generate heat. This association is likely to disproportionately harm disadvantaged populations who are more likely to work outdoors and live in hotter urban areas than their more privileged counterparts ( Koch et al., 2021 ).

The NIMHD has developed a flexible and adaptable framework to inform research into minority health and health disparities in the United States. In this article, influenced by the One Health approach, we added two new levels of influence – interspecies and planetary – to the NIHMD framework and demonstrated how the expanded framework could open new avenues of inquiry and encourage multidisciplinary collaborations. We then applied the framework to two examples: AMR and obesity.

While our proposal aims to stimulate novel thinking, we acknowledge the need for more evidence to show that adding a One Health approach can be beneficial to research addressing health disparities. Further, we do not expect the expanded framework to be relevant and applicable for all fields and topics. Moreover, we accept that many other factors – related to putting collaborations together, obtaining funding for projects, and collecting and analyzing data – must be addressed.

Human health is complex and is influenced by many different factors. By ensuring that our expanded framework includes factors related to interactions between humans and other species, and factors related to globalization and climate change, we believe that it will help ensure that no stone remains unturned in efforts to improve health for all and reduce health disparities.

There is no accompanying data for the paper.

- Laude-Sharp M

- Google Scholar

- Bjørnvad CR

- Johansen SS

- Bronfenbrenner U

- Castañeda H

- Madrigal DS

- Center for Veterinary Medicine

- Cleaveland S

- Abela-Ridder B

- Del Rio Vilas VJ

- de Glanville WA

- Lankester FJ

- Halliday JEB

- Conticini E

- Hinchliffe S

- de Garine-Wichatitsky M

- Division of Labor Force Statistics

- de Koeijer A

- Edwards-Callaway LN

- El Zowalaty ME

- Cavallero S

- Williams DR

- Hattersley L

- Feingold BJ

- Gladyshev MI

- Rothman-Ostrow P

- Macfarlane-Berry L

- Thomason MJ

- Yeboah-Manu D

- Hemsworth PH

- Hightower JM

- Hernandez GT

- Zoellner JM

- Pérez-Stable EJ

- Anderson NA

- Manderson L

- Sundsfjord A

- Steinbakk M

- Piddock LJV

- Ellenbogen C

- Aroutcheva A

- Weinstein RA

- Roberton SI

- Goldstein T

- Tremeau-Bravard A

- Ontiveros V

- Harrison LH

- Schaffner W

- Jayaweera M

- Gunawardana B

- Manatunge J

- Zimmerman D

- Weintraub R

- Bellaloui N

- Machalaba C

- Mangombo PM

- Kingebeni PM

- PREDICT Consortium

- Kilanowski JF

- Conigliaro J

- Arlinghaus KR

- Johnston CA

- Mendelsohn E

- Collignon PJ

- Meyerowitz EA

- Richterman A

- Nadimpalli ML

- Kling-Eveillard F

- Champigneulle F

- Courboulay V

- Rabinowitz P

- Michalek JE

- Phillips TD

- Shoesmith E

- Robinson TP

- Carrique-Mas J

- Jiwakanon J

- Laxminarayan R

- Magnusson U

- Van Boeckel TP

- Woolhouse MEJ

- Andremont A

- Armand-Lefèvre L

- Saltzman LY

- Bordnick PS

- Michelozzi P

- Perez Arredondo AM

- Minetto Gellert Paris J

- Falkenberg T

- Schneider MC

- Munoz-Zanzi C

- Aldighieri S

- Swinburn BA

- De Schutter O

- Devarajan R

- Kapetanaki AB

- Kuhnlein HV

- Kumanyika SK

- Matsudo VKR

- Patterson DW

- Vandevijvere S

- Waterlander WE

- Wolfenden L

- Wasserman MG

- McLeay II MT

- Zaneveld JR

- Rabinowitz PM

- Silvester R

- Criscuolo NG

- Bonhoeffer S

- van Daalen K

- Venkatasubramanian P

- Balasubramani SP

- Vigilato MAN

- Bosilevac JM

- Washington State Department of Ecology

- Woldehanna S

- Kilpatrick AM