Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 09 September 2021

The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers

- Longqi Yang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6615-8615 1 ,

- David Holtz ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0896-8628 2 , 3 ,

- Sonia Jaffe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8924-0294 1 ,

- Siddharth Suri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1318-8140 1 ,

- Shilpi Sinha 1 ,

- Jeffrey Weston 1 ,

- Connor Joyce 1 ,

- Neha Shah 1 ,

- Kevin Sherman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5793-3336 1 ,

- Brent Hecht ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7955-0202 1 &

- Jaime Teevan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2786-0209 1

Nature Human Behaviour volume 6 , pages 43–54 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

477k Accesses

244 Citations

3000 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

An Author Correction to this article was published on 05 October 2021

This article has been updated

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused a rapid shift to full-time remote work for many information workers. Viewing this shift as a natural experiment in which some workers were already working remotely before the pandemic enables us to separate the effects of firm-wide remote work from other pandemic-related confounding factors. Here, we use rich data on the emails, calendars, instant messages, video/audio calls and workweek hours of 61,182 US Microsoft employees over the first six months of 2020 to estimate the causal effects of firm-wide remote work on collaboration and communication. Our results show that firm-wide remote work caused the collaboration network of workers to become more static and siloed, with fewer bridges between disparate parts. Furthermore, there was a decrease in synchronous communication and an increase in asynchronous communication. Together, these effects may make it harder for employees to acquire and share new information across the network.

Similar content being viewed by others

The effect of co-location on human communication networks

The impact of COVID-19 on digital communication patterns

Accelerated demand for interpersonal skills in the Australian post-pandemic labour market

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, at most 5% of Americans worked from home for more than three days per week 1 , whereas it is estimated that, by April 2020, as many as 37% of Americans were working from home (WFH) full-time 2 , 3 . Thus, in a matter of weeks, the pandemic caused about one-third of US workers to shift to WFH and nearly every American that was able to work from home did so 4 . Many technology companies, such as Twitter, Facebook, Square, Box, Slack and Quora, have taken this shift one step further by announcing longer term and, in some cases permanent, remote work policies that will enable at least some employees to work remotely, even after the pandemic 5 , 6 . More generally, COVID-19 has accelerated the shift away from traditional office work, such that even firms that do not keep full-time remote work policies in place after the pandemic has ended are unlikely to fully return to their pre-COVID-19 work arrangements 7 . Instead, they are likely to switch to some type of hybrid work model, in which employees split their time between remote and office work, or a mixed-mode model, in which firms are comprised of a mixture of full-time remote employees and full-time office employees. For example, some scholars predict a long-run equilibrium in which information workers will work from home approximately 20% of the time 1 . For long-term policy decisions regarding remote, hybrid and mixed-mode work to be well informed, decision makers need to understand how remote work would impact information work in the absence of the effects of COVID-19. To answer this question, we treat Microsoft’s company-wide WFH policy during the pandemic as a natural experiment that, subject to the validity of our identifying assumptions, enables us to causally identify the impact of firm-wide remote work on employees’ collaboration networks and communication practices.

Previous research has shown that network topology, including the strength of ties, has an important role in the success of both individuals and organizations. For individuals, it is beneficial to have access to new, non-redundant information through connections to different parts of an organization’s formal organizational chart and through connections to different parts of an organization’s informal communication network 8 . Furthermore, being a conduit through which such information flows by bridging ‘structural holes’ 9 in the organization can have additional benefits for individuals 10 . For firms, certain network configurations are associated with the production of high-quality creative output 11 , and there is a competitive advantage to successfully engaging in the practice of ‘knowledge transfer,’ in which experiences from one set of people within an organization are transferred to and used by another set of people within that same organization 12 . Conditional on a given network position or configuration, the efficacy with which a given tie can transfer or provide access to novel information depends on its strength. Two people connected by a strong tie can often transfer information more easily (as they are more likely to share a common perspective), to trust one another, to cooperate with one another, and to expend effort to ensure that recently transferred knowledge is well understood and can be utilized 10 , 13 , 14 , 15 . By contrast, weak ties require less time and energy to maintain 8 , 16 and are more likely to provide access to new, non-redundant information 8 , 17 , 18 .

Our results show that the shift to firm-wide remote work caused business groups within Microsoft to become less interconnected. It also reduced the number of ties bridging structural holes in the company’s informal collaboration network, and caused individuals to spend less time collaborating with the bridging ties that remained. Furthermore, the shift to firm-wide remote work caused employees to spend a greater share of their collaboration time with their stronger ties, which are better suited to information transfer, and a smaller share of their time with weak ties, which are more likely to provide access to new information.

Previous research has also shown that the performance of workers is affected not only by the structure of the network and the strength of their ties, but also by the temporal dynamics of the network. Not only do the benefits of different types of ties vary with their age 19 , but people also benefit from changing their network position 20 , 21 , 22 , adding new ties 23 , 24 and reconnecting with dormant ties 25 . We find that the shift to firm-wide remote work may have reduced these benefits by making the collaboration network of workers more static—individuals added and deleted fewer ties from month-to-month and spent less time with newly added ties.

Existing theoretical perspectives and empirical results suggest that knowledge transfer and collaboration are also affected by the modes of communication that workers use to collaborate with one another. On the theoretical front, media richness theory 26 , 27 posits that richer communication channels, such as in-person interaction, are best suited to communicating complex information and ideas. Moreover, media synchronicity theory 28 proposes that asynchronous communication channels (such as email) are better suited for conveying information and synchronous channels (such as video calls) are better suited for converging on the meaning of information. There is also a rich body of empirical research that documents the myriad implications of communication media choice for organizations. For example, previous research has shown that establishing a rapport, which is an important precursor to knowledge transfer, is impeded by email use 29 , and that in-person and phone/video communication are more strongly associated with positive team performance than email and instant message (IM) communication 30 .

Remote work obviously eliminates in-person communication; however, we found that people did not simply replace in-person interactions with video and/or voice calls. In fact, we found that shifting to firm-wide remote work caused an overall decrease in observed synchronous communication such as scheduled meetings and audio/video calls. By contrast, we found that remote work caused employees to communicate more through media that are more asynchronous—sending more emails and many more IMs. Media richness theory, media synchronicity theory and previous empirical studies all suggest that these communication media choices may make it more difficult for workers to convey and/or converge on the meaning of complex information.

There is a large body of academic research across multiple disciplines that has studied remote work, virtual teams and telecommuting (see ref. 31 for a review of much of this work), including previous research studies that examined the network structure of virtual teams and how individual network position in virtual teams correlates with performance 32 , 33 , 34 . During the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been renewed public and academic interest in how virtual teams function. Recent analyses of telemetry and survey data show that the pandemic has affected both the who and the how of collaboration in information firms—while working remotely during the pandemic, workers are spending less time in meetings 35 , communicating more by email 35 , collaborating more with their strong ties as opposed to their weak ties 36 , and exhibiting patterns of communication that are more siloed and less stable 37 . However, these analyses, like much of the previous research on remote work, virtual teams and telecommuting, are non-causal 31 and are therefore unable to separate the effects of remote work from the effects of pandemic-related confounding factors, such as reduced focus due to COVID-19-related stress or increased caregiving responsibilities while sheltering in place. Although previous research on the causal effects of remote work does exist, this work has mainly studied employees who volunteer to work remotely, and has focused on settings such as call centres and patent offices 38 , 39 where, relative to the majority of information work, tasks are more easily codifiable and are less likely to depend on collaboration or the transfer of complex knowledge.

In this article, we contribute to the research literatures on remote work, virtual teams and telecommuting by analysing the large-scale natural experiment created by Microsoft’s firm-wide WFH policy during the COVID-19 pandemic. As remote work was mandatory during the pandemic, we are able to quantify the effects of firm-wide remote work, which are most relevant for firms considering a transition to an all-remote workforce. Furthermore, as our model specification decomposes the overall effects of firm-wide remote work into ego remote work and collaborator remote work effects, our results also provide some insight into the possible impacts of remote work policies such as mixed-mode work and hybrid work.

We analysed anonymized individual-level data describing the communication practices of 61,182 US Microsoft employees from December 2019 to June 2020—data from before and after Microsoft’s shift to firm-wide remote work (our data on workers’ choice of communication media goes back only to February 2020). Our sample contains all US Microsoft employees except for those who hold senior leadership positions and/or are members of teams that routinely handle particularly sensitive data. Given the scope of our dataset, the workers in our sample perform a wide variety of tasks, including software and hardware development, marketing and business operations. For each employee, we observe (1) their remote work status before the COVID-19 pandemic, and what share of their colleagues were remote workers before the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) their managerial status, the business group they belong to, their role and the length of their tenure at Microsoft as of February 2020; (3) a weekly summary of the amount of time spent in scheduled meetings, time spent in unscheduled video/audio calls, emails sent and IMs sent, and the length of their workweek; and (4) a monthly summary of their collaboration network. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, managers at Microsoft used their own discretion in deciding whether an employee could work from home, which was the exception rather than the norm.

The natural experiment that we analysed came from the company-wide WFH mandate Microsoft enacted in response to COVID-19. On 4 March 2020, Microsoft mandated that all non-essential employees in their Puget Sound and Bay Area campuses shift to full-time WFH. Other locations followed suit and, by 1 April 2020, all non-essential US Microsoft employees were WFH full-time. Before the onset of the pandemic, 18% of US Microsoft employees were working remote from their collaborators. For this subset of employees, the shift to firm-wide remote work did not cause a change in their own remote work status, but did induce variation in the share of their colleagues who were working remotely. For the remaining 82% of US Microsoft employees, the shift to firm-wide remote work induced variation in both their own remote work status and in the remote work status of their coworkers.

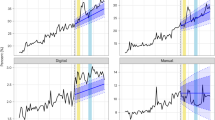

We analysed this natural experiment using a modified difference-in-differences (DiD) model. Standard DiD is an econometric approach that enables researchers to infer the causal effect of a treatment by comparing longitudinal data from at least two groups, some of which are ‘treated’ and some of which are not. Provided that the identifying assumptions of the DiD model are satisfied, the causal effect of the treatment is obtained by comparing the magnitude of the gap between the treated and untreated groups after the treatment is delivered with the magnitude of the gap between the groups before the treatment is delivered. Our modified DiD model extends the standard DiD model by estimating the causal effects of changes in two different treatment variables (one’s own remote work status and the remote work status of one’s colleagues) and by introducing additional identifying assumptions such that it is possible to draw causal inferences in the presence of an additional shock (in our case, the non-WFH-related aspects of COVID-19) that affects both treated and untreated units, and is concurrent with the exogenous shock(s) to our treatment variables. The time series trends shown in Fig. 1 suggest that the identifying assumptions of our modified DiD model are plausible; further details on the model are provided in the Methods .

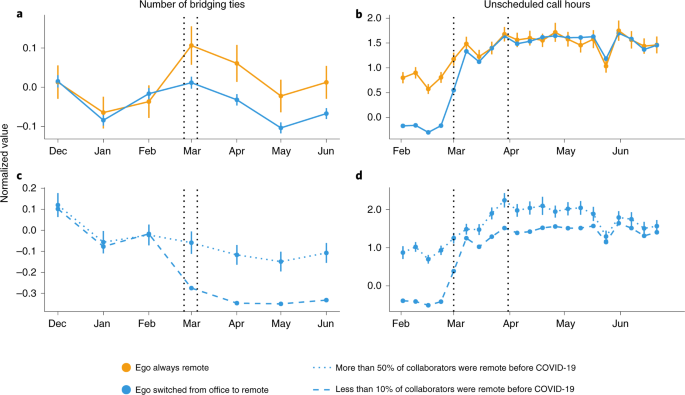

a – d , The average number of bridging ties per month ( a , c ) and the average unscheduled video/audio call hours per week ( b , d ) for different groups of employees, relative to the overall average in February. These plots establish the plausibility of the ‘parallel trends’ assumption that is required by our modified DiD model. The error bars show the 95% CIs and are in some places thinner than the symbols in the figure; s.e. values are clustered at the team level. a , b , The graphs show employees who, before COVID-19, worked from the office (blue; n = 50,268) and a matched sample of employees who worked remotely (orange; n = 10,914). c , d , The graphs show two subgroups of the blue lines in a and b —employees who, before COVID-19, had less than 10% of their collaborators working remotely (dashed; n = 36,008) and those who had more than 50% of their coworkers working remotely (dotted; n = 1,861). Both variables were normalized by subtracting and dividing by the average across the entire sample of that variable in February. Most employees transitioned to WFH during the week of 1 March 2020, although our analysis omits the month of March as a transition period.

In all of the analyses that follow, we cannot report the actual level of our outcome variables due to confidentiality concerns. Instead, throughout the paper we report outcomes and effects in terms of February value (FV)—the average level of that variable (for example, number of bridging ties) for all US employees in February.

Effects of remote work on collaboration networks

We start by presenting the non-causal time-series trends for different collaboration network outcomes across our entire sample. These trends provide insights into how work practices have changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and also represent the type of data that many executives may use when making decisions regarding their firm’s long-term remote work policy.

Descriptive statistics

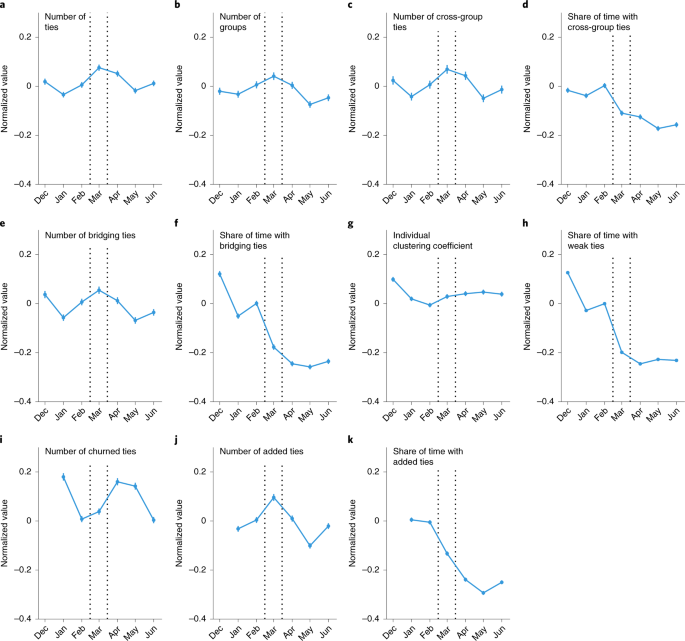

Figure 2 shows the average monthly time series for various aspects of workers’ collaboration egocentric (ego) networks from December 2019 to June 2020: the number of connections, the number of groups interacted with, the number of and share of time with cross-group connections, the number and share of time with bridging connections, the clustering coefficient, the share of time with weak connections, the number of churned and added connections, and the share of time with added connections. Mathematical definitions for these measures are provided in the Methods . Although we did not find evidence of a clear pattern of change around the shift to firm-wide remote work for many of these measures, we did observe large changes in the average shares of monthly collaboration hours spent with cross-group ties, bridging ties, weak ties and added ties, which all decreased precipitously between February and June.

a – k , The monthly averages for the collaboration network variables for all employees relative to the February average. Each variable was normalized by subtracting and dividing by the average FV for that variable. The vertical bars show the 95% CIs, but are in most places not much taller than the data points; s.e. values are clustered at the team level. The variables are employees’ average number of network ties ( a ), distinct business groups in which they have a collaborator ( b ), cross-group ties ( c ), ties that bridge structural holes in the network ( e ), individual clustering coefficient ( g ), collaborators from the previous month that they did not collaborate with that month ( i ) and added collaborators they did not collaborate with the previous month ( j ), as well as the share of time spent with cross-group ties ( d ), bridging ties ( f ), weak ties ( h ) and added ties ( k ). n = 61,279 for each panel.

Causal analysis

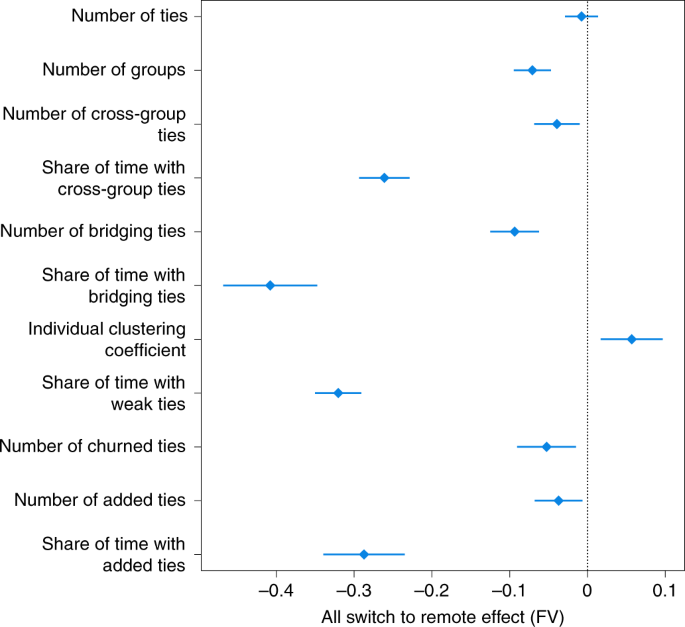

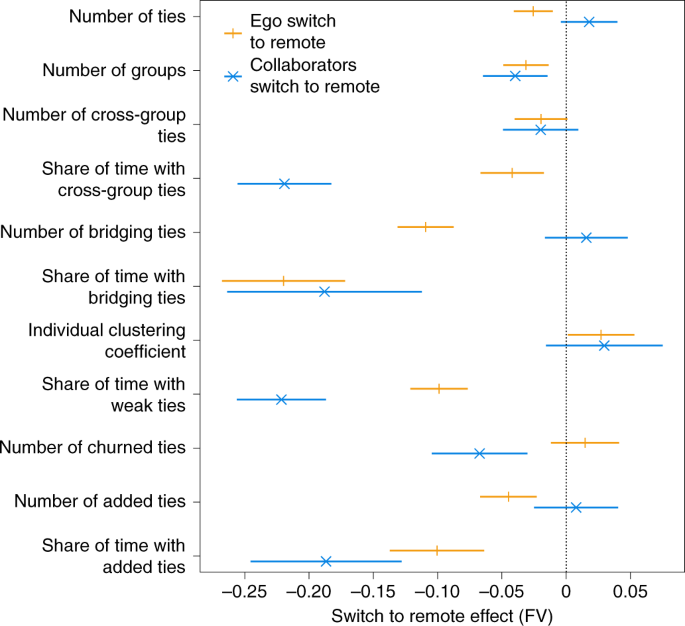

We next used our modified DiD model to isolate the effects of firm-wide remote work on the collaboration network, which are shown in Fig. 3 . Although we found no effect on the number of collaborators that employees had (the size of their collaboration ego network), we did find that firm-wide remote work decreased the number of distinct business groups that an employee was connected to by 0.07 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.05–0.10). Firm-wide remote work also decreased the cross-group connections of workers by 0.04 FV ( P = 0.008, 95% CI = 0.01–0.07) and the share of collaboration time workers spent with cross-group connections by 0.26 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.23–0.29). In other words, firm-wide remote work caused an overall decrease in the number of cross-group interactions and the fraction of attention paid to groups other than one’s own.

The estimated causal effects of both an employee and that employee’s colleagues switching to remote work on the number of collaborators an employee has, the number of distinct groups the employee collaborates with, the number of cross-group ties an employee has, the share of time an employee spends collaborating with cross-group ties, the number of bridging ties an employee has, the share of time an employee spends collaborating with bridging ties, the individual clustering coefficient of an employee’s ego network, the share of time an employee spent collaborating with weak ties, the number of churned collaborators, the number of added collaborators and the share of time spent with added collaborators. The reported effects are ( β + δ ) from equation ( 1 ), normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable in February. The symbols depict point estimates and the lines show the 95% CIs. n = 61,182 for all variables. The full results are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 .

Although formal organizational boundaries shape informal interactions 40 , the formal organization of firms and their informal social structure are two distinct, interrelated concepts 41 . Connections that provide access to diverse teams may not bridge structural holes in the network sense 9 , and connections that bridge structural holes in the network sense may not provide access to different parts of the formal organizational chart. We therefore also analysed how the shift to firm-wide remote work affected the structural diversity of employees’ ego networks with respect to the firm’s observed communication network, as opposed to the formal organizational chart. We label each tie as ‘bridging’ or ‘non-bridging’ on the basis of its local network constraint, which is a measure of the extent to which a given tie bridges structural holes in a network 9 , 42 . We then measured the effect of firm-wide remote work on the number of bridging ties that each worker had and the amount of time that each worker spent with their bridging ties. We found that, on average, firm-wide remote work decreased the number of bridging ties by 0.09 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.06–0.13) and the share of time with bridging ties by 0.41 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.35–0.47). The fact that firm-wide remote work caused workers to have fewer bridging ties, and to spend less time with their remaining bridging ties, suggests that firm-wide remote work may have reduced the ability of workers to access new information in other parts of the network. These results, in conjunction with our finding that firm-wide remote work reduced workers’ cross-group interactions, also suggest that firm-wide remote work caused the collaboration network to become more siloed, both in a formal sense and in an informal sense.

We also found that firm-wide remote work caused a 0.06 FV ( P = 0.005, 95% CI = 0.02–0.10) increase in the individual clustering coefficient, which provides a measure of what proportion of an individual’s network connections are also connected to each other (the higher a person’s individual clustering coefficient, the more dense their ego network). Given the fact that we did not observe a statistically significant effect of remote work on the number of colleagues with whom workers collaborate, this result suggests that, on average, firm-wide remote work caused workers to substitute ties that were not connected to one another for those that were. In other words, different portions of the network, which became less interconnected, also became more intraconnected.

The ability of a worker to effectively access knowledge from other parts of an organization is a function of not only the organizational and/or topological diversity of their connections, but also the strength of those connections. For each month, we classified ties as strong when they were in the top 50% of an employee’s ties in terms of hours spent communicating, and as weak otherwise. Although we have not seen strong and weak ties defined in this exact way elsewhere in the research literature on social networks, the research community has not, to our knowledge, converged on a standard way to measure tie strength. Our operationalization is similar to a common tie strength definition that simply counts the amount of contact between ties 43 , 44 , 45 and allows tie strength to vary over time on the basis of the relative amount of contact between two people 46 . Also, it is consistent with Granovetter’s original notion that tie strength is determined by a combination of “the amount of time, the emotional intensity, the intimacy (mutual confiding) and the reciprocal services which characterize the tie” 8 .

Although weak ties by definition will always get less of an employee’s time than strong ties in a given month, we found that the shift to remote work reduced the share of time that workers spent collaborating with weak ties by 0.32 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.29–0.35). As the median is just one possible cut-off to distinguish between strong and weak ties, we also analysed the entire distribution of collaboration time for each worker and confirmed that the average ego-level-normalized Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI) 47 of the collaboration time is increased by remote work, and that the average ego-level Shannon entropy 48 of collaboration time is decreased by remote work. The effects of firm-wide remote work on both of these outcomes are provided in Supplementary Table 2 . In total, these results indicate that, above and beyond the impact of firm-wide remote work on the organizational and structural diversity of workers’ ego networks, the shift to firm-wide remote work also made the allocation of workers’ time more heavily concentrated.

We also found that the shift to firm-wide remote work caused workers’ ego networks to become more static; firm-wide remote work reduced the number of existing connections that churned from month-to-month by 0.05 FV ( P = 0.006, 95% CI = 0.02–0.09), and decreased the number of connections workers added month-to-month by 0.04 FV ( P = 0.015, 95% CI = 0.01–0.07). Furthermore, the shift to firm-wide remote work decreased the share of time that workers spent collaborating with the connections they did add by 0.29 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.24–0.34). Of the added ties we observed in June 2020, 40% existed in at least one month between January 2020 and May 2020, whereas the remaining 60% did not. This suggests that the added ties that we observed are a mixture of dormant ties 25 and ties that are truly new. Overall, the changes that we observed in the temporal dynamics of ego networks may have made it more difficult for workers to capture the benefits associated with forming new connections 23 , 24 , reconnecting with dormant connections 25 and modulating their network position 20 , 21 , 22 . These results are robust to the use of alternative definitions of added and deleted ties (full details are provided in the Supplementary Information ).

In summary, our results suggest that firm-wide remote work ossified workers’ ego networks, made the network more fragmented and made each fragment more clustered. We tested for heterogeneity in the effects of the shift to firm-wide remote work on collaboration ego networks with respect to a worker’s managerial status (manager versus individual contributor), tenure at Microsoft (shorter tenure versus longer tenure) and role type (engineering versus non-engineering), and did not find meaningful heterogeneity across any of these dimensions (Supplementary Figs. 1 , 2 and 4 ).

The effects of remote work on the use of communication media

In addition to estimating the effects of firm-wide remote work on workers’ collaboration networks, we also estimated the impact of firm-wide remote work on workers’ choice of communication media.

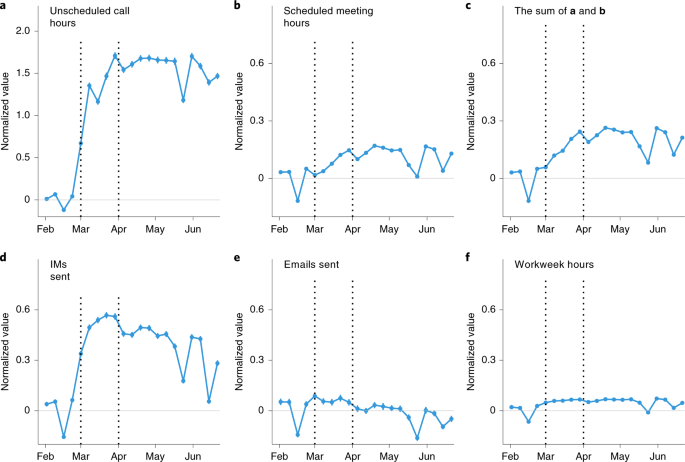

Figure 4 shows the non-causal time-series trends for workweek hours and different communication media outcomes across our entire sample. Detailed definitions for each of these outcomes are provided in the Methods . For unscheduled call hours, meeting hours, total video/audio hours and IMs sent, we observed considerable increases around the time of the switch to firm-wide remote work; these increases are sustained through our data timespan. The change in email volume is much smaller and shorter-lived. Figure 4f shows the change in workweek hours, a metric that measures the total amount of time between the first observed work activity and the last observed work activity on each work day in a given week. Although there was a sustained increase in workweek hours, it was too small to account for the large increases that we observed in the use of various communication media without a simultaneous shift in the way that employees were conducting work.

a – f , The weekly averages for each variable, relative to the February average. Each variable was normalized by subtracting and dividing by the average FV for that variable. The vertical bars show the 95% CIs, but are in most places not much taller than the data points; s.e. values are clustered at the team level. The variables are the employees’ average number of unscheduled audio/video call hours ( a ), scheduled meeting hours ( b ), total hours in scheduled meetings and unscheduled calls (the sum of a and b ) ( c ), IMs sent ( d ), emails sent ( e ), and hours between the first and last activity (sent email, scheduled meeting, or Microsoft Teams call or chat) in a day, summed across the workdays ( f ). The dips in all six metrics during the weeks of 16 February, 24 May and 14 June were due to four-day workweeks, in observance of Presidents’ Day, Juneteenth and Memorial Day, respectively. n = 61,279 for all variables.

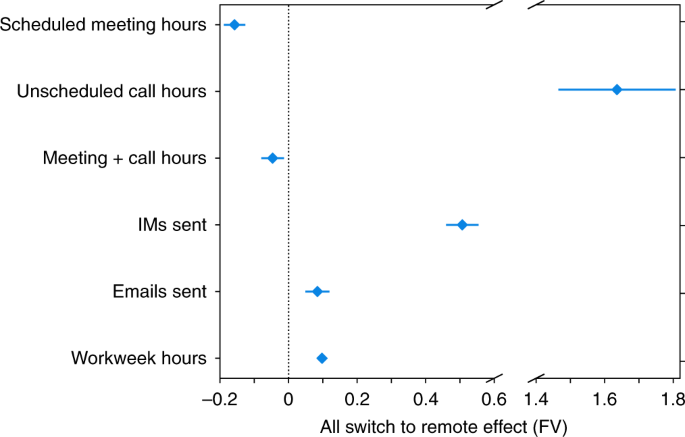

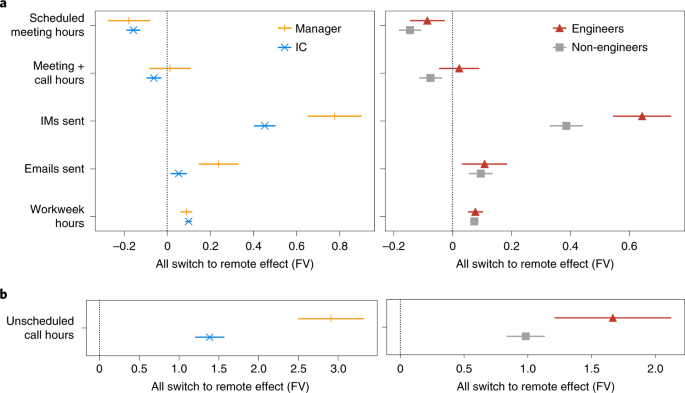

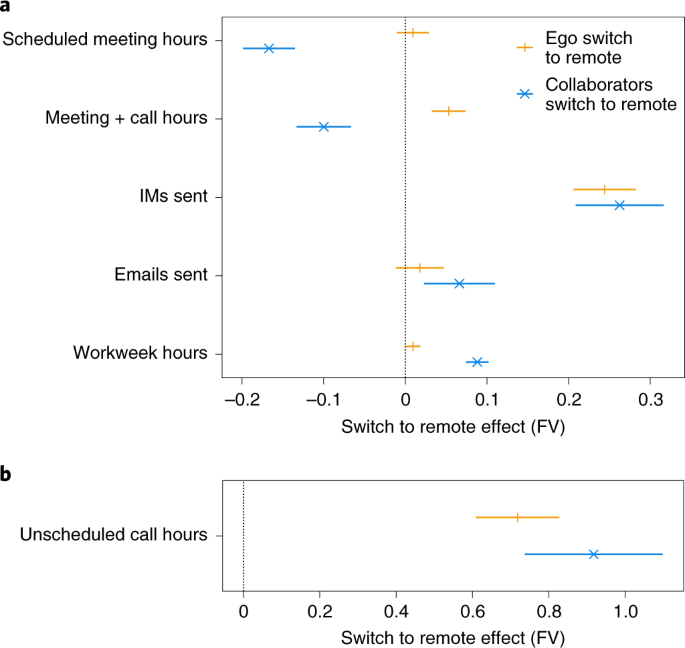

Figure 5 shows the estimated causal effects of firm-wide remote work on the amount of communication conducted through different media, as well as the length of workers’ workweeks. Relative to the baseline case of all coworkers working in an office together, we found that firm-wide remote work decreased scheduled meeting hours by 0.16 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.13–0.19) and increased unscheduled video/audio call hours by 1.6 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 1.5–1.8). The increase in unscheduled calls was more than offset by the decrease in scheduled meeting hours. To observe that, we defined the sum of unscheduled call hours and scheduled meetings hours as the synchronous video/audio communication hours. We estimate that firm-wide remote work caused a slight decrease of 0.05 FV ( P = 0.006, 95% CI = 0.01–0.08) in the total amount of synchronous video/audio communication. Given that, by definition, a shift to firm-wide remote work causes in-person interactions to drop to zero and synchronous video/audio communication decreased overall, our results also indicate that firm-wide remote work led to a decrease in the total amount of synchronous collaboration, both in-person and through Microsoft Teams.

The estimated causal effects of both an employee and their colleagues switching to remote work on the employee’s hours spent in scheduled meetings, hours spent in unscheduled calls, the sum of meetings and call hours, IMs sent, emails sent and estimated workweek hours. The reported effects are ( β + δ ) from equation ( 1 ), normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable in February. The symbols depict point estimates and lines depict 95% CIs. n = 61,182 for all variables. The full results are provided in Supplementary Table 3 .

Although firm-wide remote work caused a decrease in synchronous communication, it also caused an increase in the amount of asynchronous communication. Firm-wide remote work increased the number of emails sent by workers by 0.08 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.05–0.12) and the number of IMs sent by workers by 0.50 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.46–0.55). Firm-wide remote work also increased the average number of workweek hours by 0.10 FV ( P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.09–0.11); however, this effect is small relative to the effect on IM volume. This suggests that the increase in IMs reflects a change in workers’ collaboration patterns while working, as opposed to changes in how much workers were working. The fact that shifting to firm-wide remote work increased the number of workweek hours also makes the negative effect of firm-wide remote work on synchronous collaboration more notable. The increase in workweek hours could be an indication that employees were less productive and required more time to complete their work, or that they replaced some of their commuting time with work time; however, as we are able to measure only the time between the first and last work activity in a day, it could also be that the same amount of working time is spread across a greater share of the calendar day due to breaks or interruptions for non-work activities.

Heterogeneous effects of firm-wide remote work on communication media choice

Although the effects of firm-wide remote work on collaboration networks did not exhibit heterogeneity across the worker attributes that we observed, the effects of firm-wide remote work on communication media were in some cases larger for managers and engineers. We found that the switch to firm-wide remote work caused larger increases for managers than individual contributors in IMs sent, emails sent and unscheduled video/audio call hours (Fig. 6 , left). This is probably because, relative to individual contributors, a larger share of managers’ time is dedicated to communicating with others, that is, their direct reports (for example, to address issues blocking progress or conduct performance reviews), and representatives of other groups within the organization (for example, to coordinate activity and goals across different groups). We also find that the shift to firm-wide remote work caused larger increases for engineers than non-engineers in the number of IMs sent and the number of unscheduled call hours (Fig. 6 , right). This may be reflective of the fact that software development teams are particularly reliant on informal communication 49 , 50 , 51 , much of which may have taken place in-person before the shift to firm-wide remote work. We did not find meaningful heterogeneity with respect to employee tenure at Microsoft.

The causal effects, estimated separately for managers ( n = 9,715) and individual contributors (ICs) ( n = 51,467) (left) and engineers (n = 29, 510) and non-engineers ( n = 31,672) (right), of an employee and their colleagues switching to remote work on hours spent in scheduled meetings, the sum of scheduled meetings and unscheduled call hours, IMs sent, emails sent and estimated workweek hours ( a ), and hours spent in unscheduled calls ( b ). The reported effects are ( β + δ ) from equation ( 1 ), normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable for all employees in February. The symbols depict point estimates and the lines show the 95% CIs. The full results are provided in Supplementary Tables 8 , 9 , 22 and 23 .

Decomposing the effects of firm-wide remote work

One benefit of our empirical approach is that it enables us to decompose the causal effects of firm-wide remote work into two components: the direct effect of an employee working remotely on their own work practices (ego effects) and the indirect effect of all an employee’s colleagues working remotely on that employee’s work practices (collaborator effects). The model is linear, so the predicted effects from having half of one’s collaborators switch to remote work would be half as large.

Figure 7 shows the ego and collaborator effects of firm-wide remote work on people’s collaboration networks. Notably, the remote work status of an employee and that employee’s collaborators both contributed to the total effect of firm-wide for most network outcomes. An employee’s collaborators switching to remote work seems to have had a particularly large impact on the amount of time that workers spent with ties that are most likely to provide access to new information, that is, cross-group ties, bridging ties, weak ties and added ties. As seen in Fig. 8 , collaborator effects also dominate ego effects when we decomposed the effects of firm-wide remote work on communication media usage. More than half of the increase in IMs sent and emails sent was due to collaborators switching to remote work, and approximately 90% (+0.09 FV, P < 0.001, 95% CI = 0.07–0.10) of the increase in workweek hours was due to collaborators switching to remote work. Overall, we found that collaborators switching to remote work caused workers to spend less time attending to sources of new information, communicate more through asynchronous media and work longer hours. Looking to the future, these findings suggest that remote work policies such as mixed-mode and hybrid work may have substantial effects not only on those working remotely but also on those remaining in the office.

The estimated causal effects of either an employee ( δ from equation ( 1 )) or their colleagues ( β from equation ( 1 )) switching to remote work on the number of collaborators that an employee has, the number of distinct groups the employee collaborates with, the number of cross-group ties an employee has, the share of time an employee spends collaborating with cross-group ties, the number of bridging ties an employee has, the share of time an employee spends collaborating with bridging ties, the individual clustering coefficient of an employee’s ego network, the share of time an employee spent collaborating with weak ties, the number of churned collaborators, the number of added collaborators and the share of time spent with added collaborators. All effects were normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable in February. The symbols depict point estimates and the lines show the 95% CIs. n = 61,182 for all variables. The full results are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 .

The estimated causal effects of either an employee ( δ from equation ( 1 )) or their colleagues ( β from equation ( 1 )) switching to remote work on hours spent in scheduled meetings, the sum of scheduled meetings and unscheduled call hours, IMs sent, emails sent and estimated workweek hours ( a ), and hours spent in unscheduled calls ( b ). All effects were normalized by dividing by the average level of that variable in February. The symbols depict point estimates and the lines show the 95% CIs. n = 61,182 for all variables. The full results are provided in Supplementary Table 3 .

Our results suggest that shifting to firm-wide remote work caused the collaboration network to become more heavily siloed—with fewer ties that cut across formal business units or bridge structural holes in Microsoft’s informal collaboration network—and that those silos became more densely connected. Furthermore, the network became more static, with fewer ties added and deleted per month. Previous research suggests that these changes in collaboration patterns may impede the transfer of knowledge 10 , 12 , 13 and reduce the quality of workers’ output 11 , 23 . Our results also indicate that the shift to firm-wide remote work caused synchronous communication to decrease and asynchronous communication to increase. Not only were the communication media that workers used less synchronous, but they were also less ‘rich’ (for example, email and IM). These changes in communication media may have made it more difficult for workers to convey and process complex information 26 , 27 , 28 .

We expect that the effects we observe on workers’ collaboration and communication patterns will impact productivity and, in the long-term, innovation. Yet, across many sectors, firms are making decisions to adopt permanent remote work policies based only on short-term data 52 . Importantly, the causal estimates that we report are substantially different compared with the effects suggested by the observational trends shown in Figs. 2 and 4 . Thus, firms making decisions on the basis of non-causal analyses may set suboptimal policies. For example, some firms that choose a permanent remote work policy may put themselves at a disadvantage by making it more difficult for workers to collaborate and exchange information.

Beyond estimating the causal effects of firm-wide remote work, our results also provide preliminary insights into the effects of remote work policies such as mixed-mode and hybrid work. Specifically, the non-trivial collaborator effects that we estimate suggest that hybrid and mixed-mode work arrangements may not work as firms expect. The most effective implementations of hybrid and mixed-mode work might be those that deliberately attempt to minimize the impact of collaborator effects on those employees that are not working remotely; for example, firms might consider implementations of hybrid work in which certain teams come into the office on certain days, or in which most or all workers come into the office on some days and work remotely otherwise. Firms might also consider arrangements in which only certain types of workers (for example, individual contributors) are able to work remotely.

Although we believe these early insights are helpful, firms and academics will need to undertake a combination of quantitative and qualitative research once the COVID-19 pandemic has ended to better measure both the benefits and the downsides of different remote work policies. Large firms with the ability to collect rich telemetry data will be particularly well-positioned to build on the quantitative insights presented in this work by conducting large-scale internal field experiments. If published externally, these experiments could have the capacity to greatly further our collective understanding of the causal effects of both firm-wide remote work and other work arrangements such as hybrid work and mixed-mode work. Our results, which report both direct effects and indirect effects of remote work, suggest that such experimentation needs to be conducted carefully. Simply comparing the work practices and/or productivity levels of remote workers and office workers will likely yield biased estimates of the global treatment effects of different remote work policies, due to the causal effects of one’s colleagues working remotely. In conducting these experiments, it is crucial that firms use experiment designs that are optimized for capturing the overall effects of remote work policies, for example, graph cluster randomization 53 , 54 or switchback randomization 55 . Ideally, such field experiments would be complemented with high-quality qualitative research that can describe emergent processes and workers’ perceptions and, more generally, uncover insights beyond those that can be obtained through quantitative methods.

Our research is not without its limitations. First, our study characterizes the impacts of firm-wide remote work on the US employees of one major technology firm. Although we expect our results to generalize to other technology firms, this may not be the case. Caution should also be exercised in generalizing our results to other sectors and other countries. Second, the period of time over which we measured the causal effects of remote work are quite short (three months), and it is possible that the long-term effects of firm-wide remote work are different. For example, at the beginning of the pandemic, workers were able to leverage existing network connections, many of which were built in person. This may not be possible if firm-wide remote work were implemented long-term. Third, our analysis treats the effects of firm-wide remote work on peoples’ collaboration networks and communication media usage as separate, whereas these two types of effects may interact and exacerbate one another. Fourth, although we believe that changes to workers’ communication networks and media will affect productivity and innovation, we were unable to measure these outcomes directly. Even if we were able to measure productivity and innovation, the impacts of network structure and communication media choice on performance are likely contingent on a number of factors, including the type of task a given team/organization is trying to complete 56 , 57 , 58 , 59 . Finally, our ability to make causal claims is predicated on the validity of our modified DiD framework’s identifying assumptions: parallel trends, conditional exogeneity after matching and additively separable effects. Although we have taken steps to verify the plausibility of these assumptions and tested the robustness of our results to an alternative matching procedure 60 (details of which are provided in the Methods ), they are assumptions nonetheless.

There are multiple high-profile cases of firms such as IBM and Yahoo! enacting, but ultimately rescinding, flexible remote work policies before COVID-19, presumably due to the impacts of these policies on communication and collaboration 61 , 62 . On the basis of these examples, one might conclude that the current enthusiasm for remote work may not ultimately translate into a long-lasting shift to remote work for the majority of firms. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, workers and firms have invested in the physical and human capital required to support remote work 63 and innovation has shifted toward new technologies that support remote work 64 . Both of these factors make it more likely that for many firms, some version of remote work will persist beyond the pandemic. In light of this fact, the importance of deepening our understanding of remote work and its impacts has never been greater.

Ethical review

This research was reviewed and classified as exempt by the Massachusetts institute of Technology (MIT) Committee on the Use of Humans as Experimental Subjects (that is, MIT’s Institutional Review Board), because the research was secondary use research involving the use of de-identified data.

Our data were passively collected and anonymized by Microsoft’s Workplace Analytics product 65 , which logs activity that takes place in employees’ work email accounts and in Microsoft Teams using de-identified IDs. Microsoft Teams is collaboration software that enables employees to video/audio call, video/audio teleconference, IM and share files. The use of the data is compliant with US employee privacy laws. Employee privacy restrictions in many countries prevent us from reporting on workers outside the US. However, an employee’s communication and collaboration with international coworkers is still included in the data and those employees are still counted as part of each employee’s network. No information on international coworkers except for counting interactions with US employees was obtained for research purposes or analysed. Microsoft provides employees with appropriate notice of its use of Workplace Analytics, and sets strict controls over the collection and use of such data.

In our collaboration network, each worker is a node. For a tie to exist between two workers in a given month, those two workers must have had at least one meaningful interaction through two out of the following four communication media: email, IM, scheduled meeting and unscheduled video/audio call. A meaningful interaction is an email, IM, scheduled meeting or unscheduled video/audio call with a group of size no more than eight.

In our analysis, we classify a worker as working remotely if more than 80% of their collaboration hours in a given month are with colleagues remote to them. For employees WFH, all of their colleagues are considered to be remote from them, whereas, for those in an office, colleagues are remote to them if those colleagues are WFH or are located on a Microsoft campus in a different city. After March 2020, all US Microsoft employees are by definition working remotely, as they are WFH.

Modified DiD model

Our modified DiD model extends the standard DiD model in two ways. First, rather than measuring the effect of changes in one treatment variable, our model measures the effects of changes in two different treatment variables—(1) whether an employee is working remotely and (2) whether that employee’s colleagues are working remotely—and assumes that these two effects are additively separable. Second, our model allows the variation in our treatment variables to be induced by one exogenous shock that affects all workers in our sample, but affects some workers differently compared with others. More specifically, although all Microsoft employees were affected by COVID-19, only some employees experienced changes in their remote work status and/or the share of their collaborators that were working remotely due to Microsoft’s company-wide WFH mandate during the pandemic.

We estimate the average treatment effect for the treated (ATT) of ego remote work and collaborator remote work on all outcome measures using the following specification:

where Y i t denotes the work outcome, α i is an employee fixed-effect, τ t is a month fixed effect, D i t indicates whether employee i was a treated employee forced to work remotely in month t , s i t is the share of employee i ’s coworkers who were working remotely in month t and ϵ i t denotes the error term. Observations are weighted using coarsened exact matching (CEM) weights, and standard errors are clustered at the level of an employee’s manager. We estimate this model using data from February, April, May and June 2020. We omitted March because workers were transitioning from office work to WFH beginning in the first week of the month.

Our ability to causally identify both ATTs is predicated on a number of identifying assumptions, some of which are standard in DiD analyses and some of which are specific to our research setting. First, we assume that, for both of our ‘treatment’ variables, the time series for ‘treated’ and ‘untreated’ workers would have evolved in parallel absent the treatment. Time-series trends for different subsets of the matched sample are compared in Fig. 1 . These comparisons suggest that, for both of our treatment variables, the DiD model’s parallel trends assumption is plausible, both when measuring the effect of the treatment on network measures (Fig. 1a,c ) and when measuring the effect of the treatment on communication media measures (Figs. 1b,d ). Analogous figures for our full set of outcome variables are provided in Supplementary Figs. 5 – 19 . In all cases, the time series appear to move in parallel both before the transition to remote work, and once the transition to remote work concluded, suggesting that this identifying assumption is reasonable.

Second, we assume strict exogeneity, that is, that the timing of the switch to remote work must be independent of employees’ outcomes. As the ‘treatment group’ was all switched to WFH due to COVID-19, we are less concerned about endogeneity of treatment than we might be in other settings. However, we do need to assume that workers’ remote work status before the pandemic and the percentage of workers’ colleagues that work remotely before the pandemic are independent of how they are affected by the pandemic. This assumption would be violated if, for example, those who worked remotely before the pandemic were less likely to have unforeseen childcare responsibilities from school closures caused by the pandemic. To make this identifying assumption more plausible, we use the CEM procedure described below. If we wanted to interpret the ATTs that we estimate from those employees that started WFH due to the pandemic as average treatment effects, we would also need to assume that, conditional on the CEM procedure described below, employees’ pre-pandemic remote work status and the percentage of colleagues working remotely were independent of the effects of ego remote work and collaborator remote work on their work outcomes.

Finally, we assume that ego remote work effects, collaborator remote work effects and non-remote-work-related COVID-19 effects are additively separable. More precisely, we assume that Y i t can be written as

where RW i t is a binary variable that indicates whether employee i is working remotely at time t , s i t is the share of employee i ’s collaborators working remotely in month t , C i t is a binary variable indicating whether employee i was subject to the COVID-19 pandemic at time t and Y i t (0, 0, 0) is worker i ’s outcome at time t if all three variables were equal to 0. This assumption is an extension of the standard DiD assumption that treatment effects, cross-group differences and time-effects are additively separable and would be violated if, for example, the effects of ego remote work and/or collaborator remote work were amplified in a multiplicative manner due to other aspects of the COVID-19 pandemic (for example, childcare responsibilities or pandemic-induced changes to Microsoft’s product roadmaps). With our data, we are unable to validate the plausibility of this important identifying assumption; however, it is worth noting that causal estimates produced by standard DiD models also rely on the validity of parametric assumptions 66 .

The results from our modified DiD specification for the full set of outcomes are provided in Supplementary Tables 1 – 3 . Throughout the main text, we refer to results as insignificant when two-sided P >0.05.

We make our results more robust by estimating our DiD model using weights generated using CEM 67 . This reweighting means that we can relax the parallel trends and exogeneity assumptions described above to only be required conditional on employee characteristics. In other words, provided that any differences in how the two groups would have evolved in the absence of the pandemic or how they are affected by the pandemic are entirely explained by the employee characteristics we match on, then the CEM-based results are valid.

The CEM procedure works as follows. Each US Microsoft employee is assigned to a stratum on the basis of their role, managerial status, seniority level and tenure at Microsoft as of February 2020. For each employee i in a stratum s that contains a mixture of employees that were and were not remote before the COVID-19 pandemic, we construct a CEM weight according to the following formula:

where n O ( n R ) is the total number of non-remote (remote) employees before the COVID-19 pandemic, \({n}_{O}^{s}\) ( \({n}_{R}^{s}\) ) is the total number of non-remote (remote) employees before the COVID-19 pandemic in stratum s and O s ( R s ) is the set of non-remote (remote) employees before the COVID-19 pandemic in stratum s . The 97 (<0.2%) employees in strata without both non-remote and remote employees before the COVID-19 pandemic were discarded from our sample. The final remote:non-remote sample ratio is 1:4.6.

Treatment effect heterogeneity

We measured treatment effect heterogeneity with respect to tenure at Microsoft (shorter tenure versus longer tenure), managerial status (manager versus individual contributor) and role type (engineering versus non-engineering). To do so, we estimated the DiD model separately for each subgroup. Our treatment effect estimates for each combination of outcome and subgroup are provided in Supplementary Tables 4 – 23 .

Alternative matching procedure

To test the robustness of our analysis, we re-estimate our main DiD specification on an alternate matched sample of employees who worked remotely before the COVID-19 pandemic, which is constructed using a more extensive matching procedure introduced in ref. 60 . In this matching procedure, we augment the set of observables that we match on to include not only time-invariant employee attributes (that is, role, managerial status, seniority and new-hire status as of February), but also time-varying behavioural attributes (that is, number of scheduled meeting hours, unscheduled call hours, IMs sent, emails sent, workweek hours, network ties, business groups connected to, cross-group connections, bridging ties, churned ties and added ties, share of time with cross-group ties, bridging ties, weak ties and added ties, and the individual clustering coefficient) as measured in June 2020. As we are matching on many more variables, there are more employees who cannot be matched, and our matched sample includes only 43,576 employees.

The motivation for this matching procedure is as follows. In a standard matched DiD analysis, control and treatment units would be matched on the basis of pretreatment behaviour. This type of matching is not appropriate in our context, given that employees who did and did not work remotely before the COVID-19 pandemic are by definition in different potential outcome states in February. Assuming that there is a treatment effect to detect, matching on pretreatment behavioural outcomes would actually make our identifying assumptions less likely to hold. However, in June 2020, both employees who were and were not working remotely before the COVID-19 pandemic were in the same potential outcome state (firm-wide remote work), and therefore matching on time-varying behavioural outcomes improves the credibility of our identifying assumptions.

Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21 show the results of our DiD model as estimated on this alternative sample. The results are qualitatively similar to those we present in our main analysis.

Collaboration network outcome definitions

Number of connections: The number of people with whom one had a meaningful interaction through at least two out of four possible communication media (email, IM, scheduled meeting and unscheduled video/audio call) in a given month. A meaningful interaction is an email, meeting, video/audio call or IM with a group of size no more than eight.

Number of business groups and cross-group connections: A business group is a collection of typically fewer than ten employees who report to the same manager and share a common purpose. We look at the number of distinct business groups that one’s immediate collaborators belong to, and the number of one’s collaborators that belong to a different business group than one’s own.

Bridging connections: Bridging connections are connections with a low value of the local constraint 9 , 18 , 42 in that period. To calculate the local constraint, we first calculate the normalized mutual weight, NMW i j t , between each pair of people i and j in each period t . If there is no connection between i and j in period t , then NMW i j t = 0, otherwise \({\mathrm{NMW}}_{ijt}=\frac{2}{{n}_{it}+{n}_{jt}}\) , where n i t is the number of connections i has in period t . Then, for each i , j , t , we calculate the local constraint \({{\mathrm {{LC}}_{ijt}}} = {\mathrm {NMW}}_{ijt} + {\sum }_{k} {{{\mathrm {NMW}}}_{ikt}} \times {{\mathrm {NMW}}_{kjt}}\) . We define a global cut-off \(\widehat{\mathrm{LC}}\) on the basis of the median value of the constraint across all directed ties in February and categorize a connection as bridging if its local constraint is below that cut-off. We calculate the local constraint for each tie using the matricial formulae described in ref. 68 .

Individual clustering coefficient: The number of triads (group of three people who are all connected to each other) a person is a part of as a share of the number of triads they could possibly be part of given their degree. If a i j t is a dummy that equals 1 if and only if there is a connection between i and j in period t and n i t is the number of connections i has in period t , then individual i ’s clustering coefficient in period t is \({\mathrm{CC}}_{it}=\frac{2}{{n}_{it}({n}_{it}-1)}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{j,k}{a}_{ijt}\times {a}_{jkt}\times {a}_{kit}\) .

Number of churned connections: The number of people with whom a worker had a connection with in month t − 1, but does not have a connection in month t .

Number of added connections: The number of people with whom a worker has a connection in month t , but did not have a connection in month t − 1.

Distribution of collaboration time: In addition to unweighted network ties, we also measured the share of collaboration time that an individual spent with each of their collaborators. The number of collaboration hours is calculated by summing up the number of hours spent communicating by email or IM, in meetings and in video/audio calls. If h i j t is the number of hours that individual i spent with collaborator j in month t , then the share of collaboration time i spent with j is \({P}_{ijt}=\frac{{h}_{ijt}}{{\sum }_{k}{h}_{ikt}}\) , from which we can define the following metrics:

Share of time with own-group connections: The share of time spent with collaborators in the same business group (see the above definition), \({\mathrm{SG}}_{it}=\mathop{\sum}\limits_{j| {g}_{j}={g}_{i}}{P}_{ijt}\) , where g i is the business group that individual i belongs to.

Share of time with bridging connections: The share of collaboration time spent with collaborators with whom the local constraint (as defined under ‘bridging connections’) is below the February median \({\mathrm{BC}}_{it}=\mathop{\sum}\limits_{j| {\mathrm{LC}}_{ijt} < \widehat{\mathrm{LC}}}{P}_{ijt}\) .

Share of time with weak ties: The share of a person’s collaboration hours spent with the half of the people that they collaborate with the least during month t , \({\mathrm{ST}}_{it}=\mathop{\sum}\limits_{j| {P}_{ijt} < {P}_{it}^{m}}{P}_{ijt}\) , where \({P}_{it}^{m}\) is the time that i spends with their median connection in period t . We do not analyse the number of weak ties a person has in a given month as, by this definition, it is equal to half the number of ties they have in that month.

Share of time with added connections: The share of a person’s collaboration hours spent with people with whom they did not have a connection in the previous month, \({\mathrm{SA}}_{it}=\mathop{\sum}\limits_{j\notin {n}_{i,t-1}}{P}_{ijt}\) , where n i , t − 1 is the set of i ’s collaborators in period t − 1.

Entropy of an individual’s collaboration time (network entropy): The entropy 48 of the distribution of the hours spent with one’s collaborators, \({E}_{it}=-{\sum }_{j}{P}_{ijt}\times {{\mathrm{log}}}\,{P}_{ijt}\) .

Concentration of an individual’s collaboration time: A normalized version of the HHI 47 of the hours spent with one’s collaborators, \({\mathrm{HHI}}_{it}=\frac{1}{{n}_{it}-1}\left({n}_{it}\times {\sum }_{j}{P}_{ijt}^{2}-1\right)\) , where n i t is the number of i ’s collaborators in period t . The normalization ensures that HHI i t always falls between 0 and 1.

Communication media outcome definitions

Scheduled meeting hours: The number of hours that a person spent in meetings scheduled through Teams or Outlook calendar with at least one other person. Before firm-wide remote work, employees were able to participate in meetings both in-person and by video/audio call. After the shift to firm-wide remote work, all meetings take place entirely by video/audio call.

Unscheduled call hours: The number of hours a person spent in unscheduled video/audio calls through Microsoft Teams with at least one other person.

Emails sent: The number of emails a person sent through their work email account.

IMs sent: The number of IMs a person sent through Microsoft Teams.

Workweek hours: The sum across every day in the workweek of the time between a person’s first sent email or IM, scheduled meeting or Microsoft Teams video/audio call, and the last sent email or IM, scheduled meeting or Microsoft Teams video/audio call. A day is part of the workweek if it is a ‘working day’ for a given employee based on their work calendar.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

An anonymized version of the data supporting this study is retained indefinitely for scientific and academic purposes. The data are not publicly available due to employee privacy and other legal restrictions. The data are available from the authors on reasonable request and with permission from Microsoft Corporation.

Code availability

The code supporting this study is retained indefinitely for scientific and academic purposes. The code is not publicly available due to employee privacy and other legal restrictions. The code is available from the authors on reasonable request and with permission from Microsoft Corporation.

Change history

05 october 2021.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01228-z

Bloom, N. A. Working From Home and the Future of U.S. Economic Growth Under COVID (2020); https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jtdFIZx3hyk

Brynjolfsson, E. et al. COVID-19 and Remote Work: An Early Look at US Data. Technical Report (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. 60 million fewer commuting hours per day: how Americans use time saved by working from home. Working Paper (Univ. Chicago Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, 2020); https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/BFI_WP_2020132.pdf

Dingel, J. I. & Neiman, B. How many jobs can be done at home? J. Public Econ. 189 , 104235 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Benveniste, A. These companies’ workers may never go back to the office. CNN (18 October 2020); https://cnn.it/3jIobzJ

McLean, R. These companies plan to make working from home the new normal. As in forever. CNN (25 June 2020); https://cnn.it/3ebJU27

Lund, S., Cheng, W.-L., André Dua, A. D. S., Robinson, O. & Sanghvi, S. What 800 executives envision for the postpandemic workforce. McKinsey Global Institute (23 September 2020); https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/future-of-work/what-800-executives-envision-for-the-postpandemic-workforce

Granovetter, M. The strength of weak ties. Am. J. Sociol. 78 , 1360–1380 (1973).

Burt, R. S. Structural holes and good ideas. Am. J. Sociol. 110 , 349–399 (2004).

Reagans, R. & McEvily, B. Network structure and knowledge transfer: the effects of cohesion and range. Admin. Sci. Q. 48 , 240–267 (2003).

Uzzi, B. & Spiro, J. Collaboration and creativity: the small world problem. Am. J. Sociol. 111 , 447–504 (2005).

Argote, L. & Ingram, P. Knowledge transfer: a basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organ. Behav. Hum. Dec. Process. 82 , 150–169 (2000).

Hansen, M. T. The search-transfer problem: the role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organization subunits. Admin. Sci. Q. 44 , 82–111 (1999).

Krackhardt, D. The strength of strong ties. in Networks in the Knowledge Economy (Oxford Univ. Press, 2003).

Levin, D. Z. & Cross, R. The strength of weak ties you can trust: the mediating role of trust in effective knowledge transfer. Manage. Sci. 50 , 1477–1490 (2004).

McFadyen, M. A. & Cannella Jr, A. A. Social capital and knowledge creation: diminishing returns of the number and strength of exchange relationships. Acad. Manage. J. 47 , 735–746 (2004).

Google Scholar

Granovetter, M. The strength of weak ties: a network theory revisited. in Social Structure and Network Analysis 105–130 (Sage, 1982).

Burt, R. S. Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition (Harvard Univ. Press, 2009)

Baum, J. A., McEvily, B. & Rowley, T. J. Better with age? Tie longevity and the performance implications of bridging and closure. Organ. Sci. 23 , 529–546 (2012).

Kneeland, M. K. Network Churn: A Theoretical and Empirical Consideration of a Dynamic Process on Performance . PhD thesis, New York University (2019).

Kumar, P. & Zaheer, A. Ego-network stability and innovation in alliances. Acad. Manage. J. 62 , 691–716 (2019).

Burt, R. S. & Merluzzi, J. Network oscillation. Acad. Manage. Discov. 2 , 368–391 (2016).

Soda, G. B., Mannucci, P. V. & Burt, R. Networks, creativity, and time: staying creative through brokerage and network rejuvenation. Acad. Manage. J. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2019.1209 (2021).

Zeng, A., Fan, Y., Di, Z., Wang, Y. & Havlin, S. Fresh teams are associated with original and multidisciplinary research. Nat. Hum. Behav. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01084-x (2021).

Levin, D. Z., Walter, J. & Murnighan, J. K. Dormant ties: the value of reconnecting. Organ. Sci. 22 , 923–939 (2011).

Lengel, R. H. & Daft, R. L. An Exploratory Analysis of the Relationship Between Media Richness and Managerial Information Processing . Technical Report (Texas A&M Univ. Department of Management, 1984).

Daft, R. L. & Lengel, R. H. Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manage. Sci. 32 , 554–571 (1986).

Dennis, A. R., Fuller, R. M. & Valacich, J. S. Media, tasks, and communication processes: a theory of media synchronicity. MIS Q. 32 , 575–600 (2008).

Morris, M., Nadler, J., Kurtzberg, T. & Thompson, L. Schmooze or lose: social friction and lubrication in e-mail negotiations. Group Dyn. Theor. Res. Pract. 6 , 89–100 (2002).

Pentland, A. The new science of building great teams. Harvard Bus. Rev. 90 , 60–69 (2012).

Allen, T. D., Golden, T. D. & Shockley, K. M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol. Sci. Publ. Int. 16 , 40–68 (2015).

Ahuja, M. K. & Carley, K. M. Network structure in virtual organizations. Organ. Sci. 10 , 741–757 (1999).

Ahuja, M. K., Galletta, D. F. & Carley, K. M. Individual centrality and performance in virtual R&D groups: an empirical study. Manage. Sci. 49 , 21–38 (2003).

Suh, A., Shin, K.-s, Ahuja, M. & Kim, M. S. The influence of virtuality on social networks within and across work groups: a multilevel approach. J. Manage. Inform. Syst. 28 , 351–386 (2011).

DeFilippis, E., Impink, S., Singell, M., Polzer, J. T. & Sadun, R. Collaborating During Coronavirus: The Impact of COVID-19 on the Nature of Work. Working Paper 21-006 (Harvard Business School Organizational Behavior Unit, 2020).

Bernstein, E., Blunden, H., Brodsky, A., Sohn, W. & Waber, B. The implications of working without an office. Harvard Business Review (15 July 2020); https://hbr.org/2020/07/the-implications-of-working-without-an-office

Larson, J. et al. Dynamic silos: modularity in intra-organizational communication networks before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2104.00641 (2021).

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J. & Ying, Z. J. Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. Q. J. Econ. 130 , 165–218 (2015).

Choudhury, P., Foroughi, C. & Larson, B. Z. Work-from-anywhere: the productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Acad. Manage. Proc. 2020 , 21199 (2020).

Kleinbaum, A. M., Stuart, T. & Tushman, M. Communication (and Coordination?) in a Modern, Complex Organization (Harvard Business School, 2008).

McEvily, B., Soda, G. & Tortoriello, M. More formally: rediscovering the missing link between formal organization and informal social structure. Acad. Manage. Ann. 8 , 299–345 (2014).

Everett, M. G. & Borgatti, S. P. Unpacking Burt’s constraint measure. Social Netw. 62 , 50–57 (2020).

Onnela, J.-P. et al. Structure and tie strengths in mobile communication networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104 , 7332–7336 (2007).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Aral, S. & Van Alstyne, M. The diversity-bandwidth trade-off. Am. J. Sociol. 117 , 90–171 (2011).

Brashears, M. E. & Quintane, E. The weakness of tie strength. Social Netw. 55 , 104–115 (2018).

Burke, M. & Kraut, R. E. Growing closer on Facebook: changes in tie strength through social network site use. In Proc. SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 4187–4196 (ACM, 2014); https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/2556288.2557094

Herfindahl, O. C. Concentration in the Steel Industry . PhD thesis, Columbia University (1950).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27 , 379–423 (1948).

Herbsleb, J. D. & Mockus, A. An empirical study of speed and communication in globally distributed software development. IEEE Trans. Softw. Eng. 29 , 481–494 (2003).

Ehrlich, K. & Cataldo, M. All-for-one and one-for-all? A multi-level analysis of communication patterns and individual performance in geographically distributed software development. In Proc. ACM 2012 Conf. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 945–954 (ACM, 2012); https://doi.org/10.1145/2145204.2145345

Cataldo, M. & Herbsleb, J. D. Communication networks in geographically distributed software development. In Proc. 2008 ACM Conf. Computer Supported Cooperative Work 579–588 (ACM, 2008).

Kolko, J. Remote job postings double during coronavirus and keep rising. Indeed Hiring Lab (16 March 2021); https://www.hiringlab.org/2021/03/16/remote-job-postings-double/

Ugander, J., Karrer, B., Backstrom, L. & Kleinberg, J. Graph cluster randomization: network exposure to multiple universes. In Proc. 19th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 329–337 (2013); https://doi.org/10.1145/2487575.2487695

Eckles, D., Karrer, B. & Ugander, J. Design and analysis of experiments in networks: reducing bias from interference. J. Causal Inference https://doi.org/10.1515/jci-2015-0021 (2016).

Bojinov, I., Simchi-Levi, D. & Zhao, J. Design and analysis of switchback experiments. Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3684168 (2020).

Lechner, C., Frankenberger, K. & Floyd, S. W. Task contingencies in the curvilinear relationships between intergroup networks and initiative performance. Acad. Manage. J. 53 , 865–889 (2010).

Chung, Y. & Jackson, S. E. The internal and external networks of knowledge-intensive teams: the role of task routineness. J. Manage. 39 , 442–468 (2013).

Dennis, A. R., Wixom, B. H. & Vandenberg, R. J. Understanding fit and appropriation effects in group support systems via meta-analysis. MIS Q. 25 , 167–193 (2001).

Fuller, R. M. & Dennis, A. R. Does fit matter? The impact of task-technology fit and appropriation on team performance in repeated tasks. Inform. Syst. Res. 20 , 2–17 (2009).

Athey, S., Mobius, M. M. & Pál, J. The impact of aggregators on Internet news consumption. Preprint at SSRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2897960 (2017).

Swisher, K. Physically together: here’s the internal Yahoo no-work-from-home memo for remote workers and maybe more. All Things (22 February 2013).

Simons, J. IBM, a pioneer of remote work, calls workers back to the office. Wall Street Journal (18 May 2017).

Barrero, J. M., Bloom, N. & Davis, S. J. Why working from home will stick. Working Paper (Univ. Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, 2020).

Bloom, N., Davis, S. J. & Zhestkova, Y. COVID-19 shifted patent applications toward technologies that support working from home. Working Paper (Univ. Chicago, Becker Friedman Institute for Economics, 2020).

Workplace Analytics https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/workplace-analytics/use/metric-definitions (Microsoft, 2021).

Athey, S. & Imbens, G. W. Identification and inference in nonlinear difference-in-differences models. Econometrica 74 , 431–497 (2006).

Iacus, S. M., King, G. & Porro, G. Causal inference without balance checking: coarsened exact matching. Polit. Anal. 20 , 1–24 (2012).

Muscillo, A. A note on (matricial and fast) ways to compute Burt’s structural holes. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2102.05114 (2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was a part of Microsoft’s New Future of Work Initiative. We thank D. Eckles for assistance; N. Baym for illuminating discussions regarding social capital; and the attendees of the Berkeley Haas MORS Macro Research Lunch and the organizers and attendees of the NYU Stern Future of Work seminar for their comments and feedback. The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA

Longqi Yang, Sonia Jaffe, Siddharth Suri, Shilpi Sinha, Jeffrey Weston, Connor Joyce, Neha Shah, Kevin Sherman, Brent Hecht & Jaime Teevan

Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA

David Holtz

MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, Cambridge, MA, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.Y. analysed the data. L.Y., D.H., S.J. and S. Suri performed the research design, interpretation and writing. S. Sinha, J.W., C.J., N.S. and K.S. provided data access and expertise. B.H. and J.T. advised and sponsored the project.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Longqi Yang .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

L.Y., S.J., S. Suri, S. Sinha, J.W., C.J., N.S., K.S., B.H. and J.T. are employees of and have a financial interest in Microsoft. D.H. was previously a Microsoft intern. All of the authors are listed as inventors on a pending patent application by Microsoft Corporation (16/942,375) related to this work.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Human Behaviour thanks Nick Bloom, Yvette Blount and Sandy Staples for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Figs. 1–21 and Supplementary Tables 1–25.

Peer Review Information

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Yang, L., Holtz, D., Jaffe, S. et al. The effects of remote work on collaboration among information workers. Nat Hum Behav 6 , 43–54 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4

Download citation

Received : 02 November 2020

Accepted : 16 August 2021

Published : 09 September 2021

Issue Date : January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01196-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Virtual reality, face-to-face, and 2d video conferencing differently impact fatigue, creativity, flow, and decision-making in workplace dynamics.

- Gregorio Macchi

- Nicola De Pisapia

Scientific Reports (2024)

What science says about hybrid working — and how to make it a success

Nature (2024)

- David Evans

- Claire Mason

- Andrew Reeson

Nature Human Behaviour (2024)

Post-pandemic acceleration of demand for interpersonal skills

Securing the remote office: reducing cyber risks to remote working through regular security awareness education campaigns.

- Giddeon Njamngang Angafor

- Iryna Yevseyeva

- Leandros Maglaras

International Journal of Information Security (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters