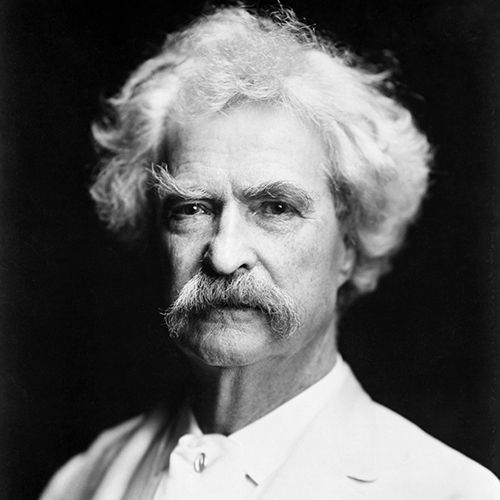

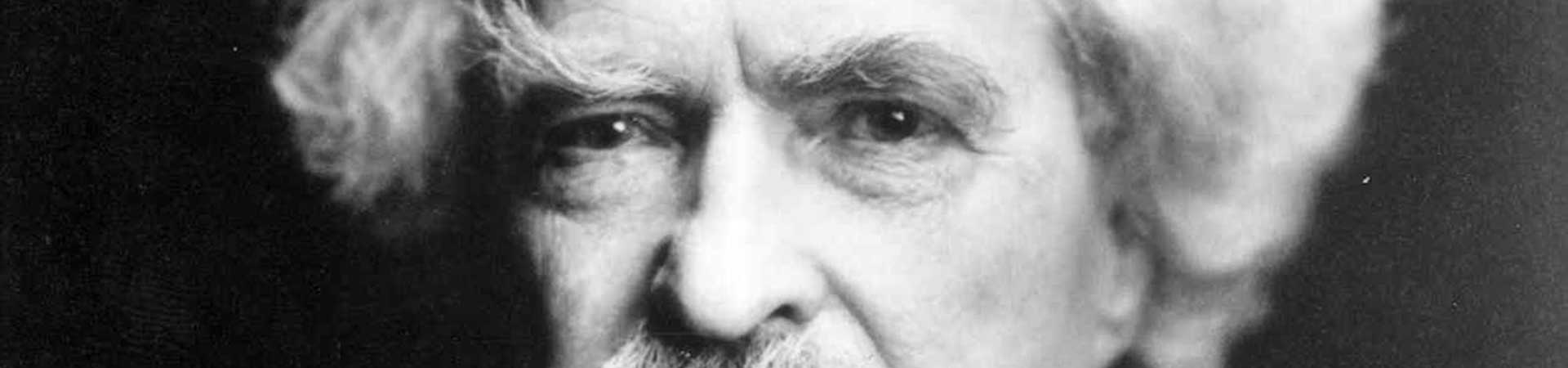

(1835-1910)

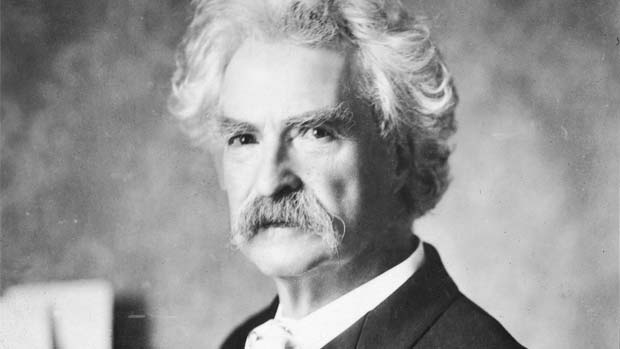

Who Was Mark Twain?

Mark Twain, whose real name was Samuel Clemens, was the celebrated author of several novels, including two major classics of American literature: The Adventures of Tom Sawyer and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn . He was also a riverboat pilot, journalist, lecturer, entrepreneur and inventor.

Twain was born Samuel Langhorne Clemens in the tiny village of Florida, Missouri, on November 30, 1835, the sixth child of John and Jane Clemens. When he was 4 years old, his family moved to nearby Hannibal, a bustling river town of 1,000 people.

John Clemens worked as a storekeeper, lawyer, judge and land speculator, dreaming of wealth but never achieving it, sometimes finding it hard to feed his family. He was an unsmiling fellow; according to one legend, young Sam never saw his father laugh.

His mother, by contrast, was a fun-loving, tenderhearted homemaker who whiled away many a winter's night for her family by telling stories. She became head of the household in 1847 when John died unexpectedly.

The Clemens family "now became almost destitute," wrote biographer Everett Emerson, and was forced into years of economic struggle — a fact that would shape the career of Twain.

Twain in Hannibal

Twain stayed in Hannibal until age 17. The town, situated on the Mississippi River, was in many ways a splendid place to grow up.

Steamboats arrived there three times a day, tooting their whistles; circuses, minstrel shows and revivalists paid visits; a decent library was available; and tradesmen such as blacksmiths and tanners practiced their entertaining crafts for all to see.

However, violence was commonplace, and young Twain witnessed much death: When he was nine years old, he saw a local man murder a cattle rancher, and at 10 he watched an enslaved person die after a white overseer struck him with a piece of iron.

Hannibal inspired several of Twain's fictional locales, including "St. Petersburg" in Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. These imaginary river towns are complex places: sunlit and exuberant on the one hand, but also vipers' nests of cruelty, poverty, drunkenness, loneliness and soul-crushing boredom — all parts of Twain's boyhood experience.

Sam kept up his schooling until he was about 12 years old, when — with his father dead and the family needing a source of income — he found employment as an apprentice printer at the Hannibal Courier , which paid him with a meager ration of food. In 1851, at 15, he got a job as a printer and occasional writer and editor at the Hannibal Western Union , a little newspaper owned by his brother, Orion.

Steamboat Pilot

Twain loved his career — it was exciting, well-paying and high-status, roughly akin to flying a jetliner today. However, his service was cut short in 1861 by the outbreak of the Civil War , which halted most civilian traffic on the river.

As the Civil War began, the people of Missouri angrily split between support for the Union and the Confederate States . Twain opted for the latter, joining the Confederate Army in June 1861 but serving for only a couple of weeks until his volunteer unit disbanded.

Where, he wondered then, would he find his future? What venue would bring him both excitement and cash? His answer: the great American West.

Heading Out West

In July 1861, Twain climbed on board a stagecoach and headed for Nevada and California, where he would live for the next five years.

At first, he prospected for silver and gold, convinced that he would become the savior of his struggling family and the sharpest-dressed man in Virginia City and San Francisco. But nothing panned out, and by the middle of 1862, he was flat broke and in need of a regular job.

Twain knew his way around a newspaper office, so that September, he went to work as a reporter for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise . He churned out news stories, editorials and sketches, and along the way adopted the pen name Mark Twain — steamboat slang for 12 feet of water.

Twain became one of the best-known storytellers in the West. He honed a distinctive narrative style — friendly, funny, irreverent, often satirical and always eager to deflate the pretentious.

He got a big break in 1865, when one of his tales about life in a mining camp, "Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog," was printed in newspapers and magazines around the country (the story later appeared under various titles).

'Innocents Abroad'

His next step up the ladder of success came in 1867, when he took a five-month sea cruise in the Mediterranean, writing humorously about the sights for American newspapers with an eye toward getting a book out of the trip.

In 1869, The Innocents Abroad was published, and it became a nationwide bestseller.

At 34, this handsome, red-haired, affable, canny, egocentric and ambitious journalist and traveler had become one of the most popular and famous writers in America.

Marriage to Olivia Langdon

However, Twain worried about being a Westerner. In those years, the country's cultural life was dictated by an Eastern establishment centered in New York City and Boston — a straight-laced, Victorian , moneyed group that cowed Twain.

"An indisputable and almost overwhelming sense of inferiority bounced around his psyche," wrote scholar Hamlin Hill, noting that these feelings were competing with his aggressiveness and vanity. Twain's fervent wish was to get rich, support his mother, rise socially and receive what he called "the respectful regard of a high Eastern civilization."

In February 1870, he improved his social status by marrying 24-year-old Olivia (Livy) Langdon, the daughter of a rich New York coal merchant. Writing to a friend shortly after his wedding, Twain could not believe his good luck: "I have ... the only sweetheart I have ever loved ... she is the best girl, and the sweetest, and gentlest, and the daintiest, and she is the most perfect gem of womankind."

Livy, like many people during that time, took pride in her pious, high-minded, genteel approach to life. Twain hoped that she would "reform" him, a mere humorist, from his rustic ways. The couple settled in Buffalo and later had four children.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S MARK TWAIN FACT CARD

Mark Twain's Books

Thankfully, Twain's glorious "low-minded" Western voice broke through on occasion.

'The Adventures of Tom Sawyer'

The Adventures of Tom Sawyer was published in 1876, and soon thereafter he began writing a sequel, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Writing this work, commented biographer Everett Emerson, freed Twain temporarily from the "inhibitions of the culture he had chosen to embrace."

'Adventures of Huckleberry Finn'

"All modern American literature comes from one book by Twain called Huckleberry Finn ," Ernest Hemingway wrote in 1935, giving short shrift to Herman Melville and others but making an interesting point.

Hemingway's comment refers specifically to the colloquial language of Twain's masterpiece, as for perhaps the first time in America, the vivid, raw, not-so-respectable voice of the common folk was used to create great literature.

Huck Finn required years to conceptualize and write, and Twain often put it aside. In the meantime, he pursued respectability with the 1881 publication of The Prince and the Pauper , a charming novel endorsed with enthusiasm by his genteel family and friends.

'Life on the Mississippi'

In 1883 he put out Life on the Mississippi , an interesting but safe travel book. When Huck Finn finally was published in 1884, Livy gave it a chilly reception.

After that, business and writing were of equal value to Twain as he set about his cardinal task of earning a lot of money. In 1885, he triumphed as a book publisher by issuing the bestselling memoirs of former President Ulysses S. Grant , who had just died.

He lavished many hours on this and other business ventures, and was certain that his efforts would be rewarded with enormous wealth, but he never achieved the success he expected. His publishing house eventually went bankrupt.

'A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court'

Twain's financial failings, reminiscent in some ways of his father's, had serious consequences for his state of mind. They contributed powerfully to a growing pessimism in him, a deep-down feeling that human existence is a cosmic joke perpetrated by a chuckling God.

Another cause of his angst, perhaps, was his unconscious anger at himself for not giving undivided attention to his deepest creative instincts, which centered on his Missouri boyhood.

In 1889, Twain published A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court , a science-fiction/historical novel about ancient England. His next major work, in 1894, was The Tragedy of Pudd'nhead Wilson , a somber novel that some observers described as "bitter."

He also wrote short stories, essays and several other books, including a study of Joan of Arc . Some of these later works have enduring merit, and his unfinished work The Chronicle of Young Satan has fervent admirers today.

Twain's last 15 years were filled with public honors, including degrees from Oxford and Yale . Probably the most famous American of the late 19th century, he was much photographed and applauded wherever he went.

Indeed, he was one of the most prominent celebrities in the world, traveling widely overseas, including a successful 'round-the-world lecture tour in 1895-96, undertaken to pay off his debts.

Family Struggles

But while those years were gilded with awards, they also brought him much anguish. Early in their marriage, he and Livy had lost their toddler son, Langdon, to diphtheria; in 1896, his favorite daughter, Susy, died at the age of 24 of spinal meningitis. The loss broke his heart, and adding to his grief, he was out of the country when it happened.

His youngest daughter, Jean, was diagnosed with severe epilepsy. In 1909, when she was 29 years old, Jean died of a heart attack. For many years, Twain's relationship with middle daughter Clara was distant and full of quarrels.

In June 1904, while Twain traveled, Livy died after a long illness. "The full nature of his feelings toward her is puzzling," wrote scholar R. Kent Rasmussen. "If he treasured Livy's comradeship as much as he often said, why did he spend so much time away from her?"

But absent or not, throughout 34 years of marriage, Twain had indeed loved his wife. "Wheresoever she was, there was Eden," he wrote in tribute to her.

Twain became somewhat bitter in his later years, even while projecting an amiable persona to his public. In private he demonstrated a stunning insensitivity to friends and loved ones.

"Much of the last decade of his life, he lived in hell," wrote Hamlin Hill. He wrote a fair amount but was unable to finish most of his projects. His memory faltered.

Twain suffered volcanic rages and nasty bouts of paranoia, and he experienced many periods of depressed indolence, which he tried to assuage by smoking cigars, reading in bed and playing endless hours of billiards and cards.

Twain died on April 21, 1910, at the age of 74. He was buried in Elmira, New York.

The Mark Twain House in Hartford, Connecticut, is now a popular attraction and is designated a National Historic Landmark.

Twain is remembered as a great chronicler of American life in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Writing grand tales about Sawyer, Finn and the mighty Mississippi River, Twain explored the American soul with wit, buoyancy and a sharp eye for truth.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Mark Twain

- Birth Year: 1835

- Birth date: November 30, 1835

- Birth State: Missouri

- Birth City: Florida

- Birth Country: United States

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Mark Twain, the writer, adventurer and wily social critic born Samuel Clemens, wrote the novels 'Adventures of Tom Sawyer' and 'Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.’

- Writing and Publishing

- Astrological Sign: Sagittarius

- Death Year: 1910

- Death date: April 21, 1910

- Death State: Connecticut

- Death City: Redding

- Death Country: United States

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: Mark Twain Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/mark-twain

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: March 31, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 3, 2014

- This is the day upon which we are reminded of what we are on the other 364.

- Civilization is a limitless multiplication of unnecessary necessaries.

- New Year's is a harmless annual institution, of no particular use to anybody save as a scapegoat for promiscuous drunks, and friendly calls, and humbug resolutions.

- The radical invents the views. When he has worn them out, the conservative adopts them.

- I'd rather have my ignorance than another man's knowledge, because I've got so much more of it.

- Everybody talks about the weather, but nobody does anything about it.

- Do not put off 'til tomorrow what can be put off 'til day-after-tomorrow just as well.

- In order to make a man or a boy covet a thing, it is only necessary to make the thing difficult to obtain.

- 'Classic'—a book which people praise and don't read.

- When angry, count four. When very angry, swear.

- Whenever you find yourself on the side of the majority, it is time to pause and reflect.

- We can't reach old age by another man's road. My habits protect my life, but would assassinate you.

- Be good and you will be lonesome.

Famous Authors & Writers

A Huge Shakespeare Mystery, Solved

9 Surprising Facts About Truman Capote

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Meet Stand-Up Comedy Pioneer Charles Farrar Browne

Francis Scott Key

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

10 Black Authors Who Shaped Literary History

A Life Lived in a Rapidly Changing World: Samuel L. Clemens‚ 1835-1910

As twain’s books provide insight into the past‚ the events of his personal life further demonstrate his role as an eyewitness to history..

During his lifetime‚ Sam Clemens watched a young United States evolve from a nation torn apart by internal conflicts to one of international power. He experienced America’s vast growth and change – from westward expansion to industrialization‚ the end of slavery‚ advancements in technology‚ big government and foreign wars. And along the way‚ he often had something to say about the changes happening in his country.

The Early Years

Samuel Clemens was born on November 30‚ 1835 in Florida‚ Missouri‚ the sixth of seven children. At age 4‚ Sam and his family moved to the small frontier town of Hannibal‚ Missouri‚ on the banks of the Mississippi River. Missouri‚ at the time‚ was a fairly new state (it had gained statehood in 1821) and made up part of the country’s western border. It was also a state that took part in slavery. Sam’s father owned one enslaved person, and his uncle owned several. In fact‚ it was on his uncle’s farm that Sam spent many boyhood summers playing in the enslaved people’s quarters‚ listening to tall tales and the spirituals that he would enjoy throughout his life.

In 1847‚ when Sam was 11‚ his father died. Shortly thereafter he left school to work as a printer’s apprentice for a local newspaper. His job was to arrange the type for each of the newspaper’s stories‚ allowing Sam to read the news of the world while completing his work.

Twain’s Young Adult Life

At 18‚ Sam headed east to New York City and Philadelphia‚ where he worked on several different newspapers and found some success at writing articles. By 1857‚ he had returned home to embark on a new career as a riverboat pilot on the Mississippi River. With the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861‚ however‚ all traffic along the river came to a halt‚ as did Sam’s pilot career. Inspired by the times‚ Sam joined up with a volunteer Confederate unit called the Marion Rangers‚ but he quit after just two weeks.

In search of a new career‚ Sam headed west in July 1861‚ at the invitation of his brother‚ Orion‚ who had just been appointed secretary of the Nevada Territory. Lured by the infectious hope of striking it rich in Nevada’s silver rush‚ Sam traveled across the open frontier from Missouri to Nevada by stagecoach. Along the journey Sam encountered Native American tribes for the first time, along with a variety of unique characters‚ mishaps, and disappointments. These events would find a way into his short stories and books‚ particularly Roughing It .

After failing as a silver prospector‚ Sam began writing for the Territorial Enterprise‚ a Virginia City‚ Nevada newspaper where he used‚ for the first time‚ his pen name‚ Mark Twain. Seeking change, by 1864 Sam headed for San Francisco where he continued to write for local papers.

In 1865 Sam’s first “big break” came with the publication of his short story “Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog ” in papers across the country. A year later Sam was hired by the Sacramento Union to visit and report on the Sandwich Islands (now Hawaii). His writings were so popular that‚ upon his return‚ he embarked upon his first lecture tour‚ which established him as a successful stage performer.

Hired by the Alta California to continue his travel writing from the east‚ Sam arrived in New York City in 1867. He quickly signed up for a steamship tour of Europe and the “Holy Land.” His travel letters‚ full of vivid descriptions and tongue-in-cheek observations‚ met with such audience approval that they were later reworked into his first book‚ The Innocents Abroad , published in 1869. It was also on this trip that Clemens met his future brother-in-law‚ Charles Langdon. Langdon reportedly showed Sam a picture of his sister‚ Olivia ‚ and Sam fell in love at first sight.

Twain Starts a Family and Moves to Hartford

After courting for two years‚ Sam Clemens and Olivia (Livy) Langdon were married in 1870. They settled in Buffalo‚ New York‚ where Sam had become a partner‚ editor, and writer for the daily newspaper the Buffalo Express . While they were living in Buffalo‚ their first child‚ Langdon Clemens‚ was born.

In 1871 Sam moved his family to Hartford‚ Connecticut‚ a city he had come to love while visiting his publisher there and where he had made friends. Livy also had family connections to the city. For the first few years the Clemenses rented a house in the heart of Nook Farm‚ a residential area that was home to numerous writers‚ publishers, and other prominent figures. In 1872 Sam’s recollections and tall tales from his frontier adventures were published in his book Roughing It . That same year the Clemenses’ first daughter Susy was born‚ but their son‚ Langdon‚ died at age two from diphtheria.

In 1873 Sam’s focus turned toward social criticism. He and Hartford Courant publisher Charles Dudley Warner co-wrote The Gilded Age ‚ a novel that attacked political corruption‚ big business, and the American obsession with getting rich that seemed to dominate the era. Ironically‚ a year after its publication‚ the Clemenses’ elaborate 25-room house on Farmington Avenue‚ which had cost the then-huge sum of $40‚000-$45‚000‚ was completed.

Twain Writes his Most Famous Books While Living in Hartford

For the next 17 years (1874-1891)‚ Sam‚ Livy, and their three daughters (Clara was born in 1874 and Jean in 1880) lived in the Hartford home. During those years Sam completed some of his most famous books‚ often finding a summer refuge for uninterrupted work at his sister-in-law’s farm in Elmira‚ New York. Novels such as The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Life on the Mississippi (1883) captured both his Missouri memories and depictions of the American scene. Yet his social commentary continued. The Prince and the Pauper (1881) explored class relations, as does A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889), which‚ going a step further‚ criticized oppression in general while examining the period’s explosion of new technologies. And‚ in perhaps his most famous work‚ Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884)‚ Clemens‚ by the way he attacked the institution of slavery‚ railed against the failures of Reconstruction and the continued poor treatment of African Americans in his own time.

Huckleberry Finn was also the first book published by Sam’s own publishing company‚ The Charles L. Webster Company. In an attempt to gain control over publication as well as to make substantial profits‚ Sam created the company in 1884. A year later he contracted with Ulysses S. Grant to publish Grant’s memoirs; the two-volume set provided large royalties for Grant’s widow and was a financial success for the publisher as well.

Twain’s Financial Ruin and Subsequent Travels

Although Sam enjoyed financial success during his Hartford years‚ he continually made bad investments in new inventions‚ which eventually brought him to bankruptcy. In an effort to economize and pay back his debts‚ Sam and Livy moved their family to Europe in 1891. When his publishing company failed in 1894‚ Sam was forced to set out on a worldwide lecture tour to earn money. In 1896 tragedy struck when Susy Clemens‚ at age 24‚ died from meningitis while on a visit to the Hartford home. Unable to bear being in the place of her death‚ the Clemenses never returned to Hartford to live.

From 1891 until 1900‚ Sam and his family traveled throughout the world. During those years Sam witnessed the increasing exploitation of weaker governments by European powers‚ which he described in his book Following the Equator (1897). The Boer War in South Africa and the Boxer Rebellion in China fueled his growing anger toward imperialistic countries and their actions. With the Spanish-American and Philippine wars in 1898‚ Sam’s wrath was redirected toward the American government. When he returned to the United States in 1900‚ his finances restored‚ Sam readily declared himself an anti-imperialist and‚ from 1901 until his death‚ served as the vice president of the Anti-Imperialist League.

Twain’s Darkest Times and Late Life

In these later years‚ Sam’s writings turned dark. They began to focus on human greed and cruelty and questioned the humanity of the human race. His public speeches followed suit and included a harshly sarcastic public introduction of Winston Churchill in 1900. Even though Sam’s lecture tour had managed to get him out of debt‚ his anti-government writings and speeches threatened his livelihood once again. As Sam was labeled by some as a traitor‚ several of his works were never published during his lifetime, either because magazines would not accept them or because of his own personal fear that his marketable reputation would be ruined.

In 1903‚ after living in New York City for three years‚ Livy became ill, and Sam and his wife returned to Italy, where she died a year later. After her death‚ Sam lived in New York until 1908, when he moved into his last house‚ “Stormfield,” in Redding‚ Connecticut. In 1909 his middle daughter Clara was married. In the same year Jean‚ the youngest daughter‚ died from an epileptic seizure. Four months later, on April 21‚ 1910‚ Sam Clemens died at age 74.

Like any good journalist‚ Sam Clemens‚ a.k.a. Mark Twain‚ spent his life observing and reporting on his surroundings. In his writings he provided images of the romantic‚ the real‚ the strengths and weaknesses of a rapidly changing world. By examining his life and his works‚ we can read into the past – piecing together various events of the era and the responses to them. We can delve into the American mindset of the late nineteenth century and make our own observations of history‚ discover new connections‚ create new inferences and gain better insights into the time period and the people who lived in it. As Sam once wrote‚ “Supposing is good‚ but finding out is better.”

Mark Twain: His Life and His Humor

- Authors & Texts

- Top Picks Lists

- Study Guides

- Best Sellers

- Plays & Drama

- Shakespeare

- Short Stories

- Children's Books

- MLA, Harvard Graduate School of Design

Mark Twain, born Samuel Langhorne Clemens Nov. 30, 1835 in the small town of Florida, MO, and raised in Hannibal, became one of the greatest American authors of all time. Known for his sharp wit and pithy commentary on society, politics, and the human condition, his many essays and novels, including the American classic, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn , are a testament to his intelligence and insight. Using humor and satire to soften the edges of his keen observations and critiques, he revealed in his writing some of the injustices and absurdities of society and human existence, his own included. He was a humorist, writer, publisher, entrepreneur, lecturer, iconic celebrity (who always wore white at his lectures), political satirist, and social progressive .

He died on April 21, 1910 when Halley’s Comet was again visible in the night sky, as lore would have it, just as it had been when he was born 75 years earlier. Wryly and presciently, Twain had said, “I came in with Halley's Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year (1910), and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don't go out with Halley's Comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: "Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.” Twain died of a heart attack one day after the Comet appeared its brightest in 1910.

A complex, idiosyncratic person, he never liked to be introduced by someone else when lecturing, preferring instead to introduce himself as he did when beginning the following lecture, “Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands” in 1866:

“Ladies and gentlemen: The next lecture in this course will be delivered this evening, by Samuel L. Clemens, a gentleman whose high character and unimpeachable integrity are only equalled by his comeliness of person and grace of manner. And I am the man! I was obliged to excuse the chairman from introducing me, because he never compliments anybody and I knew I could do it just as well.”

Twain was a complicated mixture of southern boy and western ruffian striving to fit into elite Yankee culture. He wrote in his speech, Plymouth Rock and the Pilgrims,1881 :

“I am a border-ruffian from the State of Missouri. I am a Connecticut Yankee by adoption. In me, you have Missouri morals, Connecticut culture; this, gentlemen, is the combination which makes the perfect man.”

Growing up in Hannibal, Missouri had a lasting influence on Twain, and working as a steamboat captain for several years before the Civil War was one of his greatest pleasures. While riding the steamboat he would observe the many passengers, learning much about their character and affect. His time working as a miner and a journalist in Nevada and California during the 1860s introduced him to the rough and tumble ways of the west, which is where, Feb. 3, 1863, he first used the pen name, Mark Twain, when writing one of his humorous essays for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise in Nevada.

Mark Twain was a riverboat term that means two fathoms, the point at which it is safe for the boat to navigate the waters. It seems that when Samuel Clemens adopted this pen name he also adopted another persona - a persona that represented the outspoken commoner, poking fun at the aristocrats in power, while Samuel Clemens, himself, strove to be one of them.

Twain got his first big break as a writer in 1865 with an article about life in a mining camp, called Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog , also called The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County . It was very favorably received and printed in newspapers and magazines all over the country. From there he received other jobs, sent to Hawaii, and then to Europe and the Holy Land as a travel writer. Out of these travels he wrote the book, The Innocents Abroad , in 1869, which became a bestseller. His books and essays were generally so well-regarded that he started lecturing and promoting them, becoming popular both as a writer and a speaker.

When he married Olivia Langdon in 1870, he married into a wealthy family from Elmira, New York and moved east to Buffalo, NY and then to Hartford, CT where he collaborated with the Hartford Courant Publisher to co-write The Gilded Age, a satirical novel about greed and corruption among the wealthy after the Civil War. Ironically, this was also the society to which he aspired and gained entry. But Twain had his share of losses, too - loss of fortune investing in failed inventions (and failing to invest in successful ones such as Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone ), and the deaths of people he loved, such as his younger brother in a riverboat accident, for which he felt responsible, and several of his children and his beloved wife.

Although Twain survived, thrived, and made a living out of humor, his humor was borne out of sorrow, a complicated view of life, an understanding of life’s contradictions, cruelties, and absurdities. As he once said, “ There is no laughter in heaven .”

Mark Twain’s style of humor was wry, pointed, memorable, and delivered in a slow drawl. Twain’s humor carried on the tradition of humor of the Southwest, consisting of tall tales, myths, and frontier sketches, informed by his experiences growing up in Hannibal, MO, as a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River, and as a gold miner and journalist in Nevada and California.

In 1863 Mark Twain attended in Nevada the lecture of Artemus Ward (pseudonym of Charles Farrar Browne,1834-1867), one of America’s best-known humorists of the 19th century. They became friends, and Twain learned much from him about how to make people laugh. Twain believed that how a story was told was what made it funny - repetition, pauses, and an air of naivety.

In his essay How to Tell a Story Twain says, “There are several kinds of stories, but only one difficult kind—the humorous. I will talk mainly about that one.” He describes what makes a story funny, and what distinguishes the American story from that of the English or French; namely that the American story is humorous, the English is comic, and the French is witty.

He explains how they differ:

“The humorous story depends for its effect upon the manner of the telling; the comic story and the witty story upon the matter. The humorous story may be spun out to great length, and may wander around as much as it pleases, and arrive nowhere in particular; but the comic and witty stories must be brief and end with a point. The humorous story bubbles gently along, the others burst. The humorous story is strictly a work of art, — high and delicate art, — and only an artist can tell it; but no art is necessary in telling the comic and the witty story; anybody can do it. The art of telling a humorous story —- understand, I mean by word of mouth, not print — was created in America, and has remained at home.”

Other important characteristics of a good humorous story, according to Twain, include the following:

- A humorous story is told gravely, as though there is nothing funny about it.

- The story is told wanderingly and the point is “slurred.”

- A “studied remark” is made as if without even knowing it, “as if one were thinking aloud.”

- The pause: “The pause is an exceedingly important feature in any kind of story, and a frequently recurring feature, too. It is a dainty thing, and delicate, and also uncertain and treacherous; for it must be exactly the right length--no more and no less—or it fails of its purpose and makes trouble. If the pause is too short the impressive point is passed, and the audience have had time to divine that a surprise is intended—and then you can't surprise them, of course.”

Twain believed in telling a story in an understated way, almost as if he was letting his audience in on a secret. He cites a story, The Wounded Soldier , as an example and to explain the difference in the different manners of storytelling, explaining that:

“The American would conceal the fact that he even dimly suspects that there is anything funny about it…. the American tells it in a ‘rambling and disjointed’ fashion and pretends that he does not know that it is funny at all,” whereas “The European ‘tells you beforehand that it is one of the funniest things he has ever heard, then tells it with eager delight, and is the first person to laugh when he gets through.” ….”All of which,” Mark Twain sadly comments, “is very depressing, and makes one want to renounce joking and lead a better life.”

Twain’s folksy, irreverent, understated style of humor, use of vernacular language, and seemingly forgetful rambling prose and strategic pauses drew his audience in, making them seem smarter than he. His intelligent satirical wit, impeccable timing, and ability to subtly poke fun at both himself and the elite made him accessible to a wide audience, and made him one of the most successful comedians of his time and one that has had a lasting influence on future comics and humorists.

Humor was absolutely essential to Mark Twain, helping him navigate life just as he learned to navigate the Mississippi when a young man, reading the depths and nuances of the human condition like he learned to see the subtleties and complexities of the river beneath its surface. He learned to create humor out of confusion and absurdity, bringing laughter into the lives of others as well. He once said, “Against the assault of laughter nothing can stand.”

MARK TWAIN PRIZE

Twain was much admired during his lifetime and recognized as an American icon. A prize created in his honor, The Mark Twain Prize for American Humor, the nation’s top comedy honor, has been given annually since 1998 to “people who have had an impact on American society in ways similar to the distinguished 19th century novelist and essayist best known as Mark Twain.” Previous recipients of the prize have included some of the most notable humorists of our time. The 2017 prizewinner is David Letterman, who according to Dave Itzkoff, New York Times writer , “Like Mark Twain …distinguished himself as a cockeyed, deadpan observer of American behavior and, later in life, for his prodigious and distinctive facial hair. Now the two satirists share a further connection.”

One can only wonder what remarks Mark Twain would make today about our government, ourselves, and the absurdities of our world. But undoubtedly they would be insightful and humorous to help us “stand against the assault” and perhaps even give us pause.

RESOURCES AND FURTHER READING

- Burns, Ken , Ken Burns Mark Twain Part I, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V-x_k7zrPUw

- Burns, Ken , Ken Burns Mark Twain Part II https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1arrRQJkA28

- Mark Twain , http://www.cmgww.com/historic/twain/index.php/about/biography/

- Mark Twain , history.com , http://www.history.com/topics/mark-twain

- Railton, Stephen and University of Virginia Library, Mark Twain In His Times , http://twain.lib.virginia.edu/about/mtabout.html

- Mark Twain’s Interactive Scrapbook, PBS, http://www.pbs.org/marktwain/index.html

- Mark Twain’s America , IMAX,, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b0WioOn8Tkw (Video)

- Middlekauff, Robert, Mark Twain’s Humor - With Examples , https://amphilsoc.org/sites/default/files/proceedings/150305.pdf

- Moss, Walter, Mark Twain’s Progressive and Prophetic Political Humor, http://hollywoodprogressive.com/mark-twain/

- The Mark Twain House and Museum , https://www.marktwainhouse.org/man/biography_main.php

For Teachers :

- Learn More About Mark Twain , PBS, http://www.pbs.org/marktwain/learnmore/index.html

- Lesson 1: Mark Twain and American Humor, National Endowment for the Humanities, https://edsitement.neh.gov/lesson-plan/mark-twain-and-american-humor#sect-introduction

- Lesson Plan | Mark Twain and the Mark Twain Prize for American Humor , WGBH, PBS, https://mass.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/773460a8-d817-4fbd-9c1e-15656712348e/lesson-plan-mark-twain-and-the-mark-twain-prize-for-american-humor/#.WT2Y_DMfn-Y

- Mark Twain's Feel for Language and Locale Brings His Stories to Life

- The Story of Samuel Clemens as "Mark Twain"

- A Closer Look at "A Ghost Story" by Mark Twain

- Mark Twain's Colloquial Prose Style

- Reading Quiz: 'Two Ways of Seeing a River' by Mark Twain

- Mark Twain's Views on Enslavement

- The Meaning of the Pseudonym Mark Twain

- Quotes from Mark Twain, Master of Sarcasm

- Definition and Examples of Humorous Essays

- What Were Mark Twain's Inventions?

- Two Ways of Seeing a River

- A Photo Tour of the Mark Twain House in Connecticut

- Mark Twain & Death

- A Fable by Mark Twain

- 'Life on the Mississippi' Quotes

- Who's the Real Huckleberry Finn?

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 21, 2018 | Original: April 5, 2010

The name Mark Twain is a pseudonym of Samuel Langhorne Clemens. Clemens was an American humorist, journalist, lecturer, and novelist who acquired international fame for his travel narratives, especially The Innocents Abroad (1869), Roughing It (1872), and Life on the Mississippi (1883), and for his adventure stories of boyhood, especially The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876) and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1885). A gifted raconteur, distinctive humorist, and irascible moralist, he transcended the apparent limitations of his origins to become a popular public figure and one of America’s best and most beloved writers.

Samuel Clemens, the sixth child of John Marshall and Jane Moffit Clemens, was born two months prematurely and was in relatively poor health for the first 10 years of his life. His mother tried various allopathic and hydropathic remedies on him during those early years, and his recollections of those instances (along with other memories of his growing up) would eventually find their way into Tom Sawyer and other writings. Because he was sickly, Clemens was often coddled, particularly by his mother, and he developed early the tendency to test her indulgence through mischief, offering only his good nature as bond for the domestic crimes he was apt to commit. When Jane Clemens was in her 80s, Clemens asked her about his poor health in those early years: “I suppose that during that whole time you were uneasy about me?” “Yes, the whole time,” she answered. “Afraid I wouldn’t live?” “No,” she said, “afraid you would.”

Insofar as Clemens could be said to have inherited his sense of humour, it would have come from his mother, not his father. John Clemens, by all reports, was a serious man who seldom demonstrated affection. No doubt his temperament was affected by his worries over his financial situation, made all the more distressing by a series of business failures. It was the diminishing fortunes of the Clemens family that led them in 1839 to move 30 miles (50 km) east from Florida , Mo., to the Mississippi River port town of Hannibal , where there were greater opportunities. John Clemens opened a store and eventually became a justice of the peace, which entitled him to be called “Judge” but not to a great deal more. In the meantime, the debts accumulated. Still, John Clemens believed the Tennessee land he had purchased in the late 1820s (some 70,000 acres [28,000 hectares]) might one day make them wealthy, and this prospect cultivated in the children a dreamy hope. Late in his life, Twain reflected on this promise that became a curse:

It put our energies to sleep and made visionaries of us—dreamers and indolent.…It is good to begin life poor; it is good to begin life rich—these are wholesome; but to begin it prospectively rich! The man who has not experienced it cannot imagine the curse of it.

Judging from his own speculative ventures in silver mining, business, and publishing, it was a curse that Sam Clemens never quite outgrew.

Perhaps it was the romantic visionary in him that caused Clemens to recall his youth in Hannibal with such fondness. As he remembered it in Old Times on the Mississippi (1875), the village was a “white town drowsing in the sunshine of a summer’s morning,” until the arrival of a riverboat suddenly made it a hive of activity. The gamblers, stevedores, and pilots, the boisterous raftsmen and elegant travelers, all bound for somewhere surely glamorous and exciting, would have impressed a young boy and stimulated his already active imagination. And the lives he might imagine for these living people could easily be embroidered by the romantic exploits he read in the works of James Fenimore Cooper, Sir Walter Scott, and others. Those same adventures could be reenacted with his companions as well, and Clemens and his friends did play at being pirates, Robin Hood, and other fabled adventurers. Among those companions was Tom Blankenship, an affable but impoverished boy whom Twain later identified as the model for the character Huckleberry Finn. There were local diversions as well—fishing, picnicking, and swimming. A boy might swim or canoe to and explore Glasscock’s Island, in the middle of the Mississippi River, or he might visit the labyrinthine McDowell’s Cave, about 2 miles (3 km) south of town. The first site evidently became Jackson’s Island in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn; the second became McDougal’s Cave in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. In the summers, Clemens visited his uncle John Quarles’s farm, near Florida, Mo., where he played with his cousins and listened to stories told by the slave Uncle Daniel, who served, in part, as a model for Jim in Huckleberry Finn.

It is not surprising that the pleasant events of youth, filtered through the softening lens of memory, might outweigh disturbing realities. However, in many ways the childhood of Samuel Clemens was a rough one. Death from disease during this time was common. His sister Margaret died of a fever when Clemens was not yet four years old; three years later his brother Benjamin died. When he was eight, a measles epidemic (potentially lethal in those days) was so frightening to him that he deliberately exposed himself to infection by climbing into bed with his friend Will Bowen in order to relieve the anxiety. A cholera epidemic a few years later killed at least 24 people, a substantial number for a small town. In 1847 Clemens’s father died of pneumonia. John Clemens’s death contributed further to the family’s financial instability. Even before that year, however, continuing debts had forced them to auction off property, to sell their only slave, Jennie, to take in boarders, even to sell their furniture.

Apart from family worries, the social environment was hardly idyllic. Missouri was a slave state, and, though the young Clemens had been reassured that chattel slavery was an institution approved by God, he nevertheless carried with him memories of cruelty and sadness that he would reflect upon in his maturity. Then there was the violence of Hannibal itself. One evening in 1844 Clemens discovered a corpse in his father’s office; it was the body of a California emigrant who had been stabbed in a quarrel and was placed there for the inquest. In January 1845 Clemens watched a man die in the street after he had been shot by a local merchant; this incident provided the basis for the Boggs shooting in Huckleberry Finn. Two years later he witnessed the drowning of one of his friends, and only a few days later, when he and some friends were fishing on Sny Island, on the Illinois side of the Mississippi, they discovered the drowned and mutilated body of a fugitive slave. As it turned out, Tom Blankenship’s older brother Bence had been secretly taking food to the runaway slave for some weeks before the slave was apparently discovered and killed. Bence’s act of courage and kindness served in some measure as a model for Huck’s decision to help the fugitive Jim in Huckleberry Finn.

After the death of his father, Sam Clemens worked at several odd jobs in town, and in 1848 he became a printer’s apprentice for Joseph P. Ament’s Missouri Courier. He lived sparingly in the Ament household but was allowed to continue his schooling and, from time to time, indulge in boyish amusements. Nevertheless, by the time Clemens was 13, his boyhood had effectively come to an end.

Apprenticeships

In 1850 the oldest Clemens boy, Orion, returned from St. Louis, Mo., and began to publish a weekly newspaper. A year later he bought the Hannibal Journal, and Sam and his younger brother Henry worked for him. Sam became more than competent as a typesetter, but he also occasionally contributed sketches and articles to his brother’s paper. Some of those early sketches, such as The Dandy Frightening the Squatter (1852), appeared in Eastern newspapers and periodicals. In 1852, acting as the substitute editor while Orion was out of town, Clemens signed a sketch “W. Epaminondas Adrastus Perkins.” This was his first known use of a pseudonym, and there would be several more ( Thomas Jefferson Snodgrass, Quintius Curtius Snodgrass, Josh, and others) before he adopted, permanently, the pen name Mark Twain.

Having acquired a trade by age 17, Clemens left Hannibal in 1853 with some degree of self-sufficiency. For almost two decades he would be an itinerant labourer, trying many occupations. It was not until he was 37, he once remarked, that he woke up to discover he had become a “literary person.” In the meantime, he was intent on seeing the world and exploring his own possibilities. He worked briefly as a typesetter in St. Louis in 1853 before traveling to New York City to work at a large printing shop. From there he went to Philadelphia and on to Washington , D.C.; then he returned to New York, only to find work hard to come by because of fires that destroyed two publishing houses. During his time in the East, which lasted until early 1854, he read widely and took in the sights of these cities. He was acquiring, if not a worldly air, at least a broader perspective than that offered by his rural background. And Clemens continued to write, though without firm literary ambitions, occasionally publishing letters in his brother’s new newspaper. Orion had moved briefly to Muscatine, Iowa , with their mother, where he had established the Muscatine Journal before relocating to Keokuk, Iowa, and opening a printing shop there. Sam Clemens joined his brother in Keokuk in 1855 and was a partner in the business for a little over a year, but he then moved to Cincinnati, Ohio , to work as a typesetter. Still restless and ambitious, he booked passage in 1857 on a steamboat bound for New Orleans , La., planning to find his fortune in South America. Instead, he saw a more immediate opportunity and persuaded the accomplished riverboat captain Horace Bixby to take him on as an apprentice.

Having agreed to pay a $500 apprentice fee, Clemens studied the Mississippi River and the operation of a riverboat under the masterful instruction of Bixby, with an eye toward obtaining a pilot’s license. (Clemens paid Bixby $100 down and promised to pay the remainder of the substantial fee in installments, something he evidently never managed to do.) Bixby did indeed “learn”—a word Twain insisted on—him the river, but the young man was an apt pupil as well. Because Bixby was an exceptional pilot and had a license to navigate the Missouri River and the upper as well as the lower Mississippi, lucrative opportunities several times took him upstream. On those occasions, Clemens was transferred to other veteran pilots and thereby learned the profession more quickly and thoroughly than he might have otherwise. The profession of riverboat pilot was, as he confessed many years later in Old Times on the Mississippi, the most congenial one he had ever followed. Not only did a pilot receive good wages and enjoy universal respect, but he was absolutely free and self-sufficient: “a pilot, in those days, was the only unfettered and entirely independent human being that lived in the earth,” he wrote. Clemens enjoyed the rank and dignity that came with the position; he belonged, both informally and officially, to a group of men whose acceptance he cherished; and—by virtue of his membership in the Western Boatman’s Benevolent Association, obtained soon after he earned his pilot’s license in 1859—he participated in a true “meritocracy” of the sort he admired and would dramatize many years later in A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889).

Clemens’s years on the river were eventful in other ways. He met and fell in love with Laura Wright, eight years his junior. The courtship dissolved in a misunderstanding, but she remained the remembered sweetheart of his youth. He also arranged a job for his younger brother Henry on the riverboat Pennsylvania . The boilers exploded, however, and Henry was fatally injured. Clemens was not on board when the accident occurred, but he blamed himself for the tragedy. His experience as a cub and then as a full-fledged pilot gave him a sense of discipline and direction he might never have acquired elsewhere. Before this period his had been a directionless knockabout life; afterward he had a sense of determined possibility. He continued to write occasional pieces throughout these years and, in one satirical sketch, River Intelligence (1859), lampooned the self-important senior pilot Isaiah Sellers, whose observations of the Mississippi were published in a New Orleans newspaper. Clemens and the other “starchy boys,” as he once described his fellow riverboat pilots in a letter to his wife, had no particular use for this nonunion man, but Clemens did envy what he later recalled to be Sellers’s delicious pen name, Mark Twain.

The Civil War severely curtailed river traffic, and, fearing that he might be impressed as a Union gunboat pilot, Clemens brought his years on the river to a halt a mere two years after he had acquired his license. He returned to Hannibal, where he joined the prosecessionist Marion Rangers, a ragtag lot of about a dozen men. After only two uneventful weeks, during which the soldiers mostly retreated from Union troops rumoured to be in the vicinity, the group disbanded. A few of the men joined other Confederate units, and the rest, along with Clemens, scattered. Twain would recall this experience, a bit fuzzily and with some fictional embellishments, in The Private History of the Campaign That Failed (1885). In that memoir he extenuated his history as a deserter on the grounds that he was not made for soldiering. Like the fictional Huckleberry Finn, whose narrative he was to publish in 1885, Clemens then lit out for the territory. Huck Finn intends to escape to the Indian country, probably Oklahoma ; Clemens accompanied his brother Orion to the Nevada Territory.

Clemens’s own political sympathies during the war are obscure. It is known at any rate that Orion Clemens was deeply involved in Republican Party politics and in Abraham Lincoln’s campaign for the U.S. presidency, and it was as a reward for those efforts that he was appointed territorial secretary of Nevada. Upon their arrival in Carson City, the territorial capital, Sam Clemens’s association with Orion did not provide him the sort of livelihood he might have supposed, and, once again, he had to shift for himself—mining and investing in timber and silver and gold stocks, oftentimes “prospectively rich,” but that was all. Clemens submitted several letters to the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, and these attracted the attention of the editor, Joseph Goodman, who offered him a salaried job as a reporter. He was again embarked on an apprenticeship, in the hearty company of a group of writers sometimes called the Sagebrush Bohemians, and again he succeeded.

The Nevada Territory was a rambunctious and violent place during the boom years of the Comstock Lode, from its discovery in 1859 to its peak production in the late 1870s. Nearby Virginia City was known for its gambling and dance halls, its breweries and whiskey mills, its murders, riots, and political corruption. Years later Twain recalled the town in a public lecture: “It was no place for a Presbyterian,” he said. Then, after a thoughtful pause, he added, “And I did not remain one very long.” Nevertheless, he seems to have retained something of his moral integrity. He was often indignant and prone to expose fraud and corruption when he found them. This was a dangerous indulgence, for violent retribution was not uncommon.

In February 1863 Clemens covered the legislative session in Carson City and wrote three letters for the Enterprise. He signed them “Mark Twain.” Apparently the mistranscription of a telegram misled Clemens to believe that the pilot Isaiah Sellers had died and that his cognomen was up for grabs. Clemens seized it. (See Researcher’s Note: Origins of the name Mark Twain.) It would be several years before this pen name would acquire the firmness of a full-fledged literary persona, however. In the meantime, he was discovering by degrees what it meant to be a “literary person.”

Already he was acquiring a reputation outside the territory. Some of his articles and sketches had appeared in New York papers, and he became the Nevada correspondent for the San Francisco Morning Call. In 1864, after challenging the editor of a rival newspaper to a duel and then fearing the legal consequences for this indiscretion, he left Virginia City for San Francisco and became a full-time reporter for the Call. Finding that work tiresome, he began contributing to the Golden Era and the new literary magazine the Californian, edited by Bret Harte. After he published an article expressing his fiery indignation at police corruption in San Francisco, and after a man with whom he associated was arrested in a brawl, Clemens decided it prudent to leave the city for a time. He went to the Tuolumne foothills to do some mining. It was there that he heard the story of a jumping frog. The story was widely known, but it was new to Clemens, and he took notes for a literary representation of the tale. When the humorist Artemus Ward invited him to contribute something for a book of humorous sketches, Clemens decided to write up the story. Jim Smiley and His Jumping Frog arrived too late to be included in the volume, but it was published in the New York Saturday Press in November 1865 and was subsequently reprinted throughout the country. “Mark Twain” had acquired sudden celebrity, and Sam Clemens was following in his wake.

Literary Maturity

The next few years were important for Clemens. After he had finished writing the jumping-frog story but before it was published, he declared in a letter to Orion that he had a “ ‘call’ to literature of a low order—i.e. humorous. It is nothing to be proud of,” he continued, “but it is my strongest suit.” However much he might deprecate his calling, it appears that he was committed to making a professional career for himself. He continued to write for newspapers, traveling to Hawaii for the Sacramento Union and also writing for New York newspapers, but he apparently wanted to become something more than a journalist. He went on his first lecture tour, speaking mostly on the Sandwich Islands (Hawaii) in 1866. It was a success, and for the rest of his life, though he found touring grueling, he knew he could take to the lecture platform when he needed money. Meanwhile, he tried, unsuccessfully, to publish a book made up of his letters from Hawaii. His first book was in fact The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County and Other Sketches (1867), but it did not sell well. That same year, he moved to New York City, serving as the traveling correspondent for the San Francisco Alta California and for New York newspapers. He had ambitions to enlarge his reputation and his audience, and the announcement of a transatlantic excursion to Europe and the Holy Land provided him with just such an opportunity. The Alta paid the substantial fare in exchange for some 50 letters he would write concerning the trip. Eventually his account of the voyage was published as The Innocents Abroad (1869). It was a great success.

The trip abroad was fortuitous in another way. He met on the boat a young man named Charlie Langdon, who invited Clemens to dine with his family in New York and introduced him to his sister Olivia; the writer fell in love with her. Clemens’s courtship of Olivia Langdon, the daughter of a prosperous businessman from Elmira, N.Y., was an ardent one, conducted mostly through correspondence. They were married in February 1870. With financial assistance from Olivia’s father, Clemens bought a one-third interest in the Express of Buffalo, N.Y., and began writing a column for a New York City magazine, the Galaxy. A son, Langdon, was born in November 1870, but the boy was frail and would die of diphtheria less than two years later. Clemens came to dislike Buffalo and hoped that he and his family might move to the Nook Farm area of Hartford, Conn. In the meantime, he worked hard on a book about his experiences in the West. Roughing It was published in February 1872 and sold well. The next month, Olivia Susan (Susy) Clemens was born in Elmira. Later that year, Clemens traveled to England. Upon his return, he began work with his friend Charles Dudley Warner on a satirical novel about political and financial corruption in the United States. The Gilded Age (1873) was remarkably well received, and a play based on the most amusing character from the novel, Colonel Sellers, also became quite popular.

The Gilded Age was Twain’s first attempt at a novel, and the experience was apparently congenial enough for him to begin writing Tom Sawyer, along with his reminiscences about his days as a riverboat pilot. He also published A True Story, a moving dialect sketch told by a former slave, in the prestigious Atlantic Monthly in 1874. A second daughter, Clara, was born in June, and the Clemenses moved into their still-unfinished house in Nook Farm later the same year, counting among their neighbours Warner and the writer Harriet Beecher Stowe . Old Times on the Mississippi appeared in the Atlantic in installments in 1875. The obscure journalist from the wilds of California and Nevada had arrived: he had settled down in a comfortable house with his family; he was known worldwide; his books sold well, and he was a popular favourite on the lecture tour; and his fortunes had steadily improved over the years. In the process, the journalistic and satirical temperament of the writer had, at times, become retrospective. Old Times, which would later become a portion of Life on the Mississippi, described comically, but a bit ruefully too, a way of life that would never return. The highly episodic narrative of Tom Sawyer, which recounts the mischievous adventures of a boy growing up along the Mississippi River, was coloured by a nostalgia for childhood and simplicity that would permit Twain to characterize the novel as a “hymn” to childhood. The continuing popularity of Tom Sawyer (it sold well from its first publication, in 1876, and has never gone out of print) indicates that Twain could write a novel that appealed to young and old readers alike. The antics and high adventure of Tom Sawyer and his comrades—including pranks in church and at school, the comic courtship of Becky Thatcher, a murder mystery, and a thrilling escape from a cave—continue to delight children, while the book’s comedy, narrated by someone who vividly recalls what it was to be a child, amuses adults with similar memories.

In the summer of 1876, while staying with his in-laws Susan and Theodore Crane on Quarry Farm overlooking Elmira, Clemens began writing what he called in a letter to his friend William Dean Howells “Huck Finn’s Autobiography.” Huck had appeared as a character in Tom Sawyer, and Clemens decided that the untutored boy had his own story to tell. He soon discovered that it had to be told in Huck’s own vernacular voice. Huckleberry Finn was written in fits and starts over an extended period and would not be published until 1885. During that interval, Twain often turned his attention to other projects, only to return again and again to the novel’s manuscript.

Twain believed he had humiliated himself before Boston’s literary worthies when he delivered one of many speeches at a dinner commemorating the 70th birthday of poet and abolitionist John Greenleaf Whittier. Twain’s contribution to the occasion fell flat (perhaps because of a failure of delivery or the contents of the speech itself), and some believed he had insulted three literary icons in particular: Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Oliver Wendell Holmes . The embarrassing experience may have in part prompted his removal to Europe for nearly two years. He published A Tramp Abroad (1880), about his travels with his friend Joseph Twichell in the Black Forest and the Swiss Alps, and The Prince and the Pauper (1881), a fanciful tale set in 16th-century England and written for “young people of all ages.” In 1882 he traveled up the Mississippi with Horace Bixby, taking notes for the book that became Life on the Mississippi (1883). All the while, he continued to make often ill-advised investments, the most disastrous of which was the continued financial support of an inventor, James W. Paige, who was perfecting an automatic typesetting machine. In 1884 Clemens founded his own publishing company, bearing the name of his nephew and business agent, Charles L. Webster, and embarked on a four-month lecture tour with fellow author George W. Cable, both to raise money for the company and to promote the sales of Huckleberry Finn. Not long after that, Clemens began the first of several Tom-and-Huck sequels. None of them would rival Huckleberry Finn. All the Tom-and-Huck narratives engage in broad comedy and pointed satire, and they show that Twain had not lost his ability to speak in Huck’s voice. What distinguishes Huckleberry Finn from the others is the moral dilemma Huck faces in aiding the runaway slave Jim while at the same time escaping from the unwanted influences of so-called civilization. Through Huck, the novel’s narrator, Twain was able to address the shameful legacy of chattel slavery prior to the Civil War and the persistent racial discrimination and violence after. That he did so in the voice and consciousness of a 14-year-old boy, a character who shows the signs of having been trained to accept the cruel and indifferent attitudes of a slaveholding culture, gives the novel its affecting power, which can elicit genuine sympathies in readers but can also generate controversy and debate and can affront those who find the book patronizing toward African Americans, if not perhaps much worse. If Huckleberry Finn is a great book of American literature, its greatness may lie in its continuing ability to touch a nerve in the American national consciousness that is still raw and troubling.

For a time, Clemens’s prospects seemed rosy. After working closely with Ulysses S. Grant , he watched as his company’s publication of the former U.S. president’s memoirs in 1885–86 became an overwhelming success. Clemens believed a forthcoming biography of Pope Leo XIII would do even better. The prototype for the Paige typesetter also seemed to be working splendidly. It was in a generally sanguine mood that he began to write A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, about the exploits of a practical and democratic factory superintendent who is magically transported to Camelot and attempts to transform the kingdom according to 19th-century republican values and modern technology. So confident was he about prospects for the typesetter that Clemens predicted this novel would be his “swan-song” to literature and that he would live comfortably off the profits of his investment.

Things did not go according to plan, however. His publishing company was floundering, and cash flow problems meant he was drawing on his royalties to provide capital for the business. Clemens was suffering from rheumatism in his right arm, but he continued to write for magazines out of necessity. Still, he was getting deeper and deeper in debt, and by 1891 he had ceased his monthly payments to support work on the Paige typesetter, effectively giving up on an investment that over the years had cost him some $200,000 or more. He closed his beloved house in Hartford, and the family moved to Europe, where they might live more cheaply and, perhaps, where his wife, who had always been frail, might improve her health. Debts continued to mount, and the financial panic of 1893 made it difficult to borrow money. Luckily, he was befriended by a Standard Oil executive, Henry Huttleston Rogers, who undertook to put Clemens’s financial house in order. Clemens assigned his property, including his copyrights, to Olivia, announced the failure of his publishing house, and declared personal bankruptcy. In 1894, approaching his 60th year, Samuel Clemens was forced to repair his fortunes and to remake his career.

Late in 1894 The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson and the Comedy of Those Extraordinary Twins was published. Set in the antebellum South, Pudd’nhead Wilson concerns the fates of transposed babies, one white and the other black, and is a fascinating, if ambiguous, exploration of the social and legal construction of race. It also reflects Twain’s thoughts on determinism, a subject that would increasingly occupy his thoughts for the remainder of his life. One of the maxims from that novel jocularly expresses his point of view: “Training is everything. The peach was once a bitter almond; cauliflower is nothing but cabbage with a college education.” Clearly, despite his reversal of fortunes, Twain had not lost his sense of humour. But he was frustrated too—frustrated by financial difficulties but also by the public’s perception of him as a funnyman and nothing more. The persona of Mark Twain had become something of a curse for Samuel Clemens.

Clemens published his next novel, Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (serialized 1895–96), anonymously in hopes that the public might take it more seriously than a book bearing the Mark Twain name. The strategy did not work, for it soon became generally known that he was the author; when the novel was first published in book form, in 1896, his name appeared on the volume’s spine but not on its title page. However, in later years he would publish some works anonymously, and still others he declared could not be published until long after his death, on the largely erroneous assumption that his true views would scandalize the public. Clemens’s sense of wounded pride was necessarily compromised by his indebtedness, and he embarked on a lecture tour in July 1895 that would take him across North America to Vancouver, B.C., Can., and from there around the world. He gave lectures in Australia, New Zealand, India, South Africa, and points in-between, arriving in England a little more than a year afterward. Clemens was in London when he was notified of the death of his daughter Susy, of spinal meningitis. A pall settled over the Clemens household; they would not celebrate birthdays or holidays for the next several years. As an antidote to his grief as much as anything else, Clemens threw himself into work. He wrote a great deal he did not intend to publish during those years, but he did publish Following the Equator (1897), a relatively serious account of his world lecture tour. By 1898 the revenue generated from the tour and the subsequent book, along with Henry Huttleston Rogers’s shrewd investments of his money, had allowed Clemens to pay his creditors in full. Rogers was shrewd as well in the way he publicized and redeemed the reputation of “Mark Twain” as a man of impeccable moral character. Palpable tokens of public approbation are the three honorary degrees conferred on Clemens in his last years—from Yale University in 1901, from the University of Missouri in 1902, and, the one he most coveted, from Oxford University in 1907. When he traveled to Missouri to receive his honorary Doctor of Laws, he visited old friends in Hannibal along the way. He knew that it would be his last visit to his hometown.

Clemens had acquired the esteem and moral authority he had yearned for only a few years before, and the writer made good use of his reinvigorated position. He began writing The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg (1899), a devastating satire of venality in small-town America, and the first of three manuscript versions of The Mysterious Stranger. (None of the manuscripts was ever completed, and they were posthumously combined and published in 1916.) He also started What Is Man? (published anonymously in 1906), a dialogue in which a wise “Old Man” converts a resistant “Young Man” to a brand of philosophical determinism. He began to dictate his autobiography, which he would continue to do until a few months before he died. Some of Twain’s best work during his late years was not fiction but polemical essays in which his earnestness was not in doubt: an essay against anti-Semitism, Concerning the Jews (1899); a denunciation of imperialism, To the Man Sitting in Darkness (1901); an essay on lynching, The United States of Lyncherdom (posthumously published in 1923); and a pamphlet on the brutal and exploitative Belgian rule in the Congo, King Leopold’s Soliloquy (1905).

Clemens’s last years have been described as his “bad mood” period. The description may or may not be apt. It is true that in his polemical essays and in much of his fiction during this time he was venting powerful moral feelings and commenting freely on the “damn’d human race.” But he had always been against sham and corruption, greed, cruelty, and violence. Even in his California days, he was principally known as the “Moralist of the Main” and only incidentally as the “Wild Humorist of the Pacific Slope.” It was not the indignation he was expressing during these last years that was new; what seemed to be new was the frequent absence of the palliative humour that had seasoned the earlier outbursts. At any rate, even though the worst of his financial worries were behind him, there was no particular reason for Clemens to be in a good mood.

The family, including Clemens himself, had suffered from one sort of ailment or another for a very long time. In 1896 his daughter Jean was diagnosed with epilepsy, and the search for a cure, or at least relief, had taken the family to different doctors throughout Europe. By 1901 his wife’s health was seriously deteriorating. She was violently ill in 1902, and for a time Clemens was allowed to see her for only five minutes a day. Removing to Italy seemed to improve her condition, but that was only temporary. She died on June 5, 1904. Something of his affection for her and his sense of personal loss after her death is conveyed in the moving piece Eve’s Diary (1906). The story chronicles in tenderly comic ways the loving relationship between Adam and Eve. After Eve dies, Adam comments at her grave site, “Wheresoever she was, there was Eden.” Clemens had written a commemorative poem on the anniversary of Susy’s death, and Eve’s Diary serves the equivalent function for the death of his wife. He would have yet another occasion to publish his grief. His daughter Jean died on Dec. 24, 1909. The Death of Jean (1911) was written beside her deathbed. He was writing, he said, “to keep my heart from breaking.”

It is true that Clemens was bitter and lonely during his last years. He took some solace in the grandfatherly friendships he established with young schoolgirls he called his “angelfish.” His “Angelfish Club” consisted of 10 to 12 girls who were admitted to membership on the basis of their intelligence, sincerity, and good will, and he corresponded with them frequently. In 1906–07 he published selected chapters from his ongoing autobiography in the North American Review. Judging from the tone of the work, writing his autobiography often supplied Clemens with at least a wistful pleasure. These writings and others reveal an imaginative energy and humorous exuberance that do not fit the picture of a wholly bitter and cynical man. He moved into his new house in Redding, Conn., in June 1908, and that too was a comfort. He had wanted to call it “Innocents at Home,” but his daughter Clara convinced him to name it “Stormfield,” after a story he had written about a sea captain who sailed for heaven but arrived at the wrong port. Extracts from Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven was published in installments in Harper’s Magazine in 1907–08. It is an uneven but delightfully humorous story, one that critic and journalist H.L. Mencken ranked on a level with Huckleberry Finn and Life on the Mississippi. Little Bessie and Letters from the Earth (both published posthumously) were also written during this period, and, while they are sardonic, they are antically comic as well. Clemens thought Letters from the Earth was so heretical that it could never be published. However, it was published in a book by that name, along with other previously unpublished writings, in 1962, and it reinvigorated public interest in Twain’s serious writings. The letters did present unorthodox views—that God was something of a bungling scientist and human beings his failed experiment, that Christ, not Satan, devised hell, and that God was ultimately to blame for human suffering, injustice, and hypocrisy. Twain was speaking candidly in his last years but still with a vitality and ironic detachment that kept his work from being merely the fulminations of an old and angry man.

Clara Clemens married in October 1909 and left for Europe by early December. Jean died later that month. Clemens was too grief-stricken to attend the burial services, and he stopped working on his autobiography. Perhaps as an escape from painful memories, he traveled to Bermuda in January 1910. By early April he was having severe chest pains. His biographer Albert Bigelow Paine joined him, and together they returned to Stormfield. Clemens died on April 21. The last piece of writing he did, evidently, was the short humorous sketch Etiquette for the Afterlife: Advice to Paine (first published in full in 1995). Clearly, Clemens’s mind was on final things; just as clearly, he had not altogether lost his sense of humour. Among the pieces of advice he offered Paine, for when his turn to enter heaven arrived, was this: “Leave your dog outside. Heaven goes by favor. If it went by merit, you would stay out and the dog would go in.” Clemens was buried in the family plot in Elmira, N.Y., alongside his wife, his son, and two of his daughters. Only Clara survived him.

Reputation and Assessment

Shortly after Clemens’s death, Howells published My Mark Twain (1910), in which he pronounced Samuel Clemens “sole, incomparable, the Lincoln of our literature.” Twenty-five years later Ernest Hemingway wrote in The Green Hills of Africa (1935), “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.” Both compliments are grandiose and a bit obscure. For Howells, Twain’s significance was apparently social—the humorist, Howells wrote, spoke to and for the common American man and woman; he emancipated and dignified the speech and manners of a class of people largely neglected by writers (except as objects of fun or disapproval) and largely ignored by genteel America. For Hemingway, Twain’s achievement was evidently an aesthetic one principally located in one novel. For later generations, however, the reputation of and controversy surrounding Huckleberry Finn largely eclipsed the vast body of Clemens’s substantial literary corpus: the novel has been dropped from some American schools’ curricula on the basis of its characterization of the slave Jim, which some regard as demeaning, and its repeated use of an offensive racial epithet.

As a humorist and as a moralist, Twain worked best in short pieces. Roughing It is a rollicking account of his adventures in the American West, but it is also seasoned with such exquisite yarns as Buck Fanshaw’s Funeral and The Story of the Old Ram; A Tramp Abroad is for many readers a disappointment, but it does contain the nearly perfect Jim Baker’s Blue-Jay Yarn. In A True Story, told in an African American dialect, Twain transformed the resources of the typically American humorous story into something serious and profoundly moving. The Man That Corrupted Hadleyburg is relentless social satire; it is also the most formally controlled piece Twain ever wrote. The originality of the longer works is often to be found more in their conception than in their sustained execution. The Innocents Abroad is perhaps the funniest of all of Twain’s books, but it also redefined the genre of the travel narrative by attempting to suggest to the reader, as Twain wrote, “how he would be likely to see Europe and the East if he looked at them with his own eyes.” Similarly, in Tom Sawyer, he treated childhood not as the achievement of obedience to adult authority but as a period of mischief-making fun and good-natured affection. Like Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote, which he much admired, Huckleberry Finn rang changes on the picaresque novel that are of permanent interest.