- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How and When to Use Images in an Essay

3-minute read

- 15th December 2018

Pages of text alone can look quite boring. And while you might think that ‘boring’ is normal for an essay, it doesn’t have to be. Using images and charts in an essay can make your document more visually interesting. It can even help you earn better grades if done right!

Here, then, is our guide on how to use images in an academic essay .

How to Use Images in an Essay

Usually, you will only need to add an image in academic writing if it serves a specific purpose (e.g. illustrating your argument). Even then, you need to make sure images are presently correctly. As such, try asking yourself the following questions whenever you add an image in an essay:

- Does it add anything useful? Any image or chart you include in your work should help you make your argument or explain a point more clearly. For instance, if you are analysing a film, you may need to include a still from a scene to illustrate a point you are making.

- Is the image clearly labelled? All images in your essay should come with clear captions (e.g. ‘Figure 1’ plus a title or description). Without these, your reader may not know how images relate to the surrounding text.

- Have you mentioned the image in the text? Make sure to directly reference the image in the text of your essay. If you have included an image to illustrate a point, for instance, you would include something along the lines of ‘An example of this can be seen in Figure 1’.

The key, then, is that images in an essay are not just decoration. Rather, they should fit with and add to the arguments you make in the text.

Citing Images and Illustrations

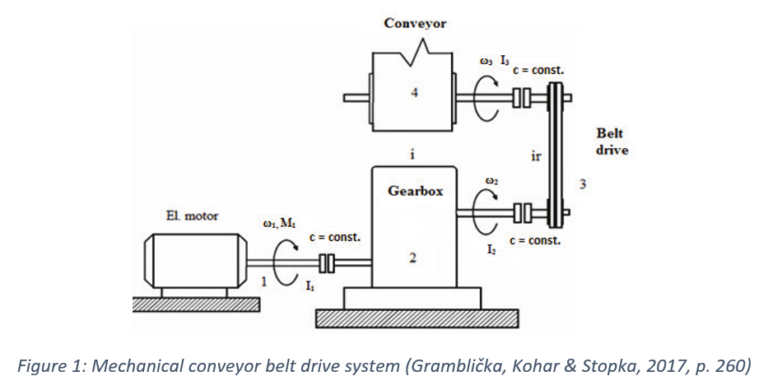

If you have created all the images and charts you want to use in your essay, then all you need to do is label them clearly (as described above). But if you want to use an image found somewhere else in your work, you will need to cite your source as well, just as you would when quoting someone.

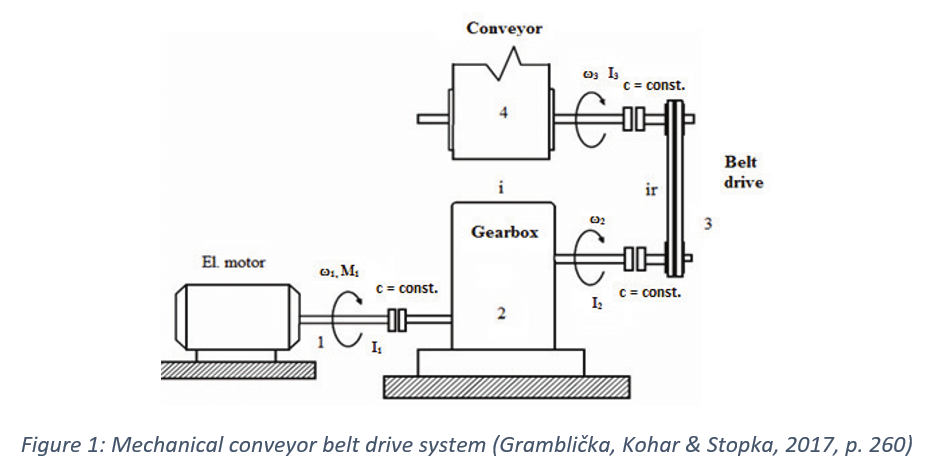

The exact format for this will depend on the referencing system you’re using. However, with author–date referencing, it usually involves giving the source author’s name and a year of publication:

In the caption above, for example, we have cited the paper containing the image and the page it is on. We would then need to add the paper to the reference list at the end of the document:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Gramblička, S., Kohar, R., & Stopka, M. (2017). Dynamic analysis of mechanical conveyor drive system. Procedia Engineering , 192, 259–264. DOI: 10.1016/j.proeng.2017.06.045

You can also cite an image directly if it not part of a larger publication or document. If we wanted to cite an image found online in APA referencing , for example, we would use the following format:

Surname, Initial(s). (Role). (Year). Title or description of image [Image format]. Retrieved from URL.

In practice, then, we could cite a photograph as follows:

Booth, S. (Photographer). (2014). Passengers [Digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/stevebooth/35470947736/in/pool-best100only/

Make sure to check your style guide for which referencing system to use.

Need to Write An Excellent Essay?

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Get help from a language expert. Try our proofreading services for free.

4-minute read

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

The 5 Best Ecommerce Website Design Tools

A visually appealing and user-friendly website is essential for success in today’s competitive ecommerce landscape....

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

When to Use an Image in an Essay: What You Need to Know

by Antony W

September 13, 2022

There’s a 98% chance that the essays you’ve written so far are pages of text alone. While plain text can make the work look dull, academic writing hardly ever requires you to use images, charts, and graphs in the essay.

While that doesn’t mean you can’t include visuals in your assignment, it’s important to learn when to use an image in an essay.

You can add an image in your essay only if it serves a specific purpose such as illustrating an argument for more clarity. If you’re going to include an image in your essay, make sure you present it correctly and at the same time follow the standard citation rules.

In this guide, we’ll talk more about images in an essay, including why they’re important, when exactly to add one in your work, and the right way cite them.

In the end, you should be able to make a solid judgment as far as the inclusion of images in your work is concerned.

Key Takeaways

- The types of images you can use in an essay are pictures, graphs, and charts.

- It’s acceptable to add an image in an essay to illustrate an argument for more clarity.

- Images can be useful when explaining a process, showing an example, or in the instance when you want to grab your reader’s attention.

- Be advised that you must follow the accepted citation rules when including an image in the essay.

What Type of Images Can You Include in An Essay?

Just because you can include an image in an essay doesn’t mean any image you include in the assignment will be a good fit.

Remember, the role of an image is to give your essay a better structure and make your writing readable and easy to understand.

Instructors don’t impose limits on the types of images a student can include in an essay.

For example, a student working on an IB Physics Internal Assessment can use charts, drawings, photos, and infographic to explain concepts that would be otherwise difficult to explain in words.

However, there are rule you must observe.

1. Pictures

Pictures introduce breaks between blocks of words in an essay while adding meaning to the overall context of the assignment.

By themselves, pictures are worth a thousand words, which is another way to state that they’re descriptive enough to communicate a solid message.

While you can use any picture in your essay, provided it’s relevant for your topic, the image you choose to include must have meet the following requirements:

- The image should be clear when viewed in web document and in print

- You must have the legal right to use the image in your essay – otherwise you’d have to create your own

- The image you choose should be relevant to the topic of your essay

The next thing you need to understand before including an image in an essay is placement .

In other words, where should you insert the picture?

- End of the essay: Include the image in the reference section of your essay and then include a reference to the image in the body text of your essay.

- In the body of the essay: Have the image inserted on a separate page within the body section of your essay. Don’t forget to mention the picture in the text so that your readers are aware that you’ve intentionally included it in your work.

- Within body text: You can use in-text citations to include an image in your essay, but it’s best to avoid this option because it tends to alter the formatting of the paper.

The picture you include in your essay must have a source name, unique description, and a number to make it easy for your reader to find and reference the image if they want to.

Also, you should attribute the photo if you don’t own it so that you don’t violate the copyright ownership of the material.

2. Graphs and Charts

Graphs and charts are the best type of media to include in an essay.

Unlike standard pictures, graphs and charts can easily explain complex concepts in visuals than lengthy words would do. These types of images are useful because they can help you to:

- Illustrate size, meaning, or a degree of influence

- Compare two or more objects

- Provide an illustration of some statistics that are relevant to your study

The best thing about using graphs and charts in an essay is that you can explain complex concepts and make them easily understood.

So whether you want to show a comparison or believe that graphs and charts can communicate ideas better than words, you can add some visualization to your work to make your essay appear more appealing and easier to read.

You can use ready-made graphs and charts in your work provided you cite them properly.

Or you can use a software solution such as Microsoft PowerPoint to create your own.

Whether you download your media from the web or create them on your own, it’s important that you add appropriate naming and comments to enhance information clarity.

Get Essay Writing Help

If you haven’t started your essay because you have many other assignments to complete, you can hire our essay writers to help you get the work done fast.

We help with topic selection, research, custom writing, editing and proofreading at an affordable price.

When to Use an Image in an Essay

The following are instance of when it would make sense to use an image in an essay:

1. When Explaining a Process

Some processes are difficult to explain because they are complex.

If you don't think words can adequately convey meaning or the message you wish to communicate, it would be best to use an image to simplify your explanations and bring out meaning.

2. If You Want to Show an Example

Any claim you make in your article or research paper must include proofs and specific examples.

To reinforce your argument, you might provide a graphic or chart as an easy-to-understand illustration.

Let’s say you want to talk about the effects of various medications on bacteria.

In such a case, it would make more sense to use a before-and-after photographs or graphs to illustrate your point.

3. Images Are Useful for Grabbing Reader’s Attention

You can use graphic pictures to draw the attention of your readers. When writing on works of art and cultures, it would make a lot of sense to include images in your piece of writing.

Final Thoughts

To be abundantly clear, images aren’t a requirement in essay writing.

So you should only include them if they serve unique and academically acceptable purpose.

You don’t want to add an aesthetic appeal to your essay when really there’s no need for you to do so in the first place.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

17.1 “Reading” Images

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Define the key concepts and elements of visual rhetoric.

- Interpret visual information using the language of visual rhetoric.

- Interpret images differently based on cultural considerations.

- Choose digital and visual media according to the rhetorical situation and cultural context when writing for different audiences.

- Make informed decisions about intellectual property issues regarding images.

To compose an effective essay or a strong visual, a creator works with a number of elements that are remarkably similar from one medium to the other. Both stories and pictures contain information presented by a creator who has a particular point of view and arranges the work in two-dimensional space. The information is likely to be open to multiple interpret , which may or may not be justified by the text. Although the sharing of personal opinions and beliefs has value, the focus here is on interpreting or analyzing texts in combination with your personal experiences.

Interpreting Visual Information

Both words and pictures convey information, but each does so in different ways that require interpretation. Interpretation is the sense a person makes of a piece of communication—textual, oral, or visual. It includes personal experience, the context in which the communication is made, and other rhetorical elements. (See Glance at Genre: Relationship Between Image and Rhetoric for a list of key terms related to visual elements and rhetoric.) By the time readers get to college, they have internalized strategies to help them critically understand a variety of written texts.

Images present a different set of challenges for critical readers. For example, in a photograph or drawing, information is presented simultaneously, so viewers can start or stop anywhere they like. Because visual information is presented in this way, its general meaning may be apparent at a glance, while more nuanced or complicated meanings may take longer to figure out and likely will vary from one viewer to another.

Some images, however, do not really lend themselves to interpretation. Before trying to engage in rhetorical discourse about an image, be sure it contributes something of value. For example, Figure 17.2 shows a punk rock concert featuring the band Naked Raygun with several concertgoers in the foreground. Such pictures are common forms of memorabilia that serve an archival function. The features common to visual rhetoric—point of view, arrangement, color, and symbol—do not inspire much in the way of discussion in this particular image. Parts are blurry, some of the figures are obscure, and the picture’s purpose is unclear. Therefore, any analysis of the image may be guided more by personal opinion than by critical thinking. Such images are not the focus of this chapter.

Figure 17.3 , in contrast, depicts not merely a moment in time for the sake of memory, although it certainly does that. It contains a central, dominant figure. The color red is bold and centers the figure, giving the image weight. It also conveys several political messages, both obvious and nuanced. The woman in the picture is wearing a mask, as people were either asked or mandated to do during the COVID-19 pandemic. The slogan on her mask reads “I can’t breathe,” words that were made infamous after Eric Garner (1970–2014) died as the result of an illegal chokehold inflicted by a New York City police officer during arrest. These words were repeated by George Floyd (1973–2020) in an 8-minute, 46-second video showing his murder by a Minnesota police officer who knelt on Floyd’s neck. The phrase became one of several slogans of the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, symbolizing the struggle that people of color endure when living in an implicitly and explicitly racist culture. Breathing—like blood—is fundamental, essential. Without breath, there is no life. Thus, this slogan draws attention to the fact that people of color may be brutalized for no reason other than their existence.

Placing the slogan on a mask is a design choice likely to provoke those who have argued against mandated mask wearing as an assault on personal liberty and who have proclaimed they could not breathe while wearing masks. Juxtaposition , or placing contrasting elements close together, is a technique that image creators often use for a variety of purposes: humor, irony, sarcasm, or—as in this case—disgust or outrage. The juxtaposition of the mask with a slogan referencing literal asphyxiation emphasizes the wearer’s view that state violence against people of color is a more serious threat to her existence than a mask. Thus, the image is open to multiple interpretations.

Thinking Critically

To think critically about visual information, first identify the objects, facts, processes, or symbols portrayed in the image. Taking all the information together, ask whether there is a main or unifying idea. Is the meaning open to multiple interpretations? Is it suggested but not stated? Is it clear and unambiguous? Are there multiple levels of meaning, both stated and unstated? When you view an image, pausing to answer such questions will sharpen your critical faculties, increase your understanding of the visual information you encounter, and help you use images more meaningfully in texts you create.

Visual Rhetoric

Written texts rely on strategies such as thesis statements, topic sentences, paragraphing, tone, and sentence structure to communicate their message to their audience. Images rely on different strategies, including point of view , arrangement , color , and symbol . When writing about images or including them in your writing, think critically about the visual strategies they use and the effect they will have on your audience.

Using these techniques may or may not make you a proficient artist or creator of images. However, familiarity with the technical language of the visual arts will certainly enable you to describe what you observe as you build the evidence that allows you to interpret an image, reflect on it, analyze it, and make persuasive arguments about it.

Point of View

In written texts, point of view refers to the “person” from whose vantage point the information is delivered, either a character in the story or a narrator outside the story. However, in photographs, drawings, and paintings, point of view refers to the place from which the image creator looks at the subject—where the photographer places their camera or the artist their easel.

Photographs that haven’t been manipulated in a darkroom or digitally by a computer only reproduce the subject in front of the camera, as it exists in the moment the shutter opens and closes. They do not show anything to the left or right, above or below, or what comes before or after. A camera aimed to the east omits information from the north, west, and south. In other words, any photograph is the result of placing a camera in a certain location, at a certain height and distance, at a specific time of day and using a particular lens, film, and perhaps a filter. All of these decisions about where, when, and how to place the camera create the visual point of view.

You can find good examples of these kinds of limited truths in real-estate advertisements featuring photographs of houses for sale. The photograph might not reveal a landfill next door or a factory across the street—though you might infer such limitations from a low selling price or confirm them by driving past the house.

The creator of Figure 17.4 chooses to highlight the digital waterfall with its seductive lighting and colors. Meanwhile, the people interacting with the computer are barely visible, standing off to the side, some nearly out of the frame. The silhouetted profiles and darkened faces lack identifying details. These features are emphasized by the blurred people in the background. These figures, too, are unidentifiable and are looking out of the frame, uninterested. The effect is to imply that the waterfall and its computer interface dominate human interaction and possibly even human existence.

To think critically about point of view, answer the following questions:

- From what place or stance does the image creator view the subject?

- What effect does this particular point of view have on the way viewers may think or feel about the subject?

- What would happen if the vantage point were elsewhere—above or below, left or right?

- What would change in the image if the point of view were changed?

Arrangement

In addition to point of view, artists use arrangement to signal an image’s significance to the reader. The term arrangement in visual texts might be compared to terms such as order , organization , and structure in verbal texts, though the differences are substantial. While writers arrange , or put together, a story, essay, or poem to take place over time—that is, the time readers need to follow the text, line by line, through a number of pages—image creators arrange pictures in the two-dimensional space of their viewfinder, paper, or canvas to invite viewers to read in space rather than time. This difference is also evident in sculpture and other three-dimensional works, which require viewers to move around them to read them spatially. In visual texts, then, arrangement refers to the ways in which the various parts of a picture come together to present a single coherent experience for the viewer.

In contrast to static images, which are read spatially, videos and some types of multimodal texts—those incorporating more than one genre, discipline, or literacy (for example, GIFs that incorporate pictures or videos with language)—combine elements of both time and space. That is, they invite viewers to examine an image in motion that changes over time. Video creators often mimic linear time by telling a story, or they repeat key images to be interpreted differently after being seen in various contexts within the video.

One element to examine is the use of pattern —predictable, repeated elements within the visual field that the eye notices and seems attracted to. Just as sonnets, sestinas, and haiku follow patterns of lines, so do visual compositions. But in these, patterns are created by light and color rather than words. Documentary and commercial photographers often use visual patterns to lead viewers to an intended meaning. Patterns are especially prominent in street art, where the elements of surrounding architecture and infrastructure interact with the work, as shown in Figure 17.5 .

Many patterns are suggested by mathematics. For example, the Möbius strip is both a mathematical construct and a visual enigma. It has one side and one boundary curve. It looks like a spiral, but it does not intersect itself. Thus, it gives the impression of being infinite. In Figure 17.5 , the artist capitalizes on these features of the Möbius strip, using it to depict the seemingly endless cycle of destruction (green tanks) and reconstruction (yellow steamrollers) in one of the world’s most contested pieces of real estate: the Gaza Strip.

Ownership and control of the Gaza Strip are disputed. Approximately two million people live there, many in refugee camps. Since the mid-20th century, the region has been fought over by Israel, Egypt, and Palestinian Arabs. As you contemplate the mural, think about the way its creator uses pattern and repetition to convey various ideas and emotions. The following questions may help:

- Which elements within the mural are repeated?

- Where is its center of gravity or weight?

- Where do patterns of light/dark, large/small, and color lead the eye?

- How do pattern and balance contribute to meaning in a two-dimensional image?

- What does the arrangement suggest about the meaning of the image?

Color and Symbol

Pattern and arrangement are controlled by the image creator and intended to guide the viewer. Color and symbol allow the viewer greater latitude in interpreting the image, in part because particular colors suggest specific moods. Think about your personal reactions to different colors. What color might you select to paint your bedroom? What is your favorite color for, say, clothing or cars? While these may differ according to personal preference, traditional symbolic values are attached to different colors in literature and art. Why, for instance, does red often symbolize anger or war on the one hand and romance or passion on the other? Why does black often suggest danger or death? And why does white often stand for innocence or purity? Are the reasons for these associations arbitrary, cultural, or logical?

Particular colors also suggest or reinforce social and political ideas. What, for example, is suggested by adding a red, white, and blue American flag to a magazine advertisement for an American automobile, political poster, or bumper sticker? What is the meaning of a yellow ribbon tied to a tree in front of a house or an image of a yellow ribbon sticker attached to the tailgate of a pickup truck? By themselves, colors do not specify political positions, arguments, or ideas, but used in conjunction with specific words or forms—a flag or ribbon, for example—the emotional power of color can be influential.

Color associations globally are complicated and highly nuanced. The following overview is brief and simplified, to be considered merely as an introduction or starting point for your research and investigations into individual artistic expressions. When you interpret an artist’s use of color, one place to start is with the hues found in the natural world. Because blood is red, the color is often associated with life, heat, and passion. Yellow and green appear with the new growth of spring, so these colors often symbolize new beginnings, freshness, and hope. Both the sea and the sky are blue. Although these elements can be turbulent, many people find peace and tranquility as they reflect on them, and thus they are often associated with these emotions.

Regardless of colors’ natural associations, people from around the world understand colors differently. In China, for example, red is a celebratory color associated with holidays, feasts, and the giving of gifts, whereas in some parts of Africa the color may symbolize the sacrifice necessitated by the fight for independence. In the Western world, white can represent purity or innocence and is often worn by young women at their weddings. However, in parts of Asia, white is a color of mourning.

The colors mentioned so far are mostly primary colors: red, yellow, and blue. The secondary colors—orange, green, and purple—carry more complex meanings. Both orange and the bright shade of green called neon or chartreuse are easy to see in all light conditions. Therefore, they are often used for safety purposes, on caution signs or uniforms of emergency workers. The color orange is associated with the robes of Buddhist monks, thus representing in Buddhist cultures that which is holy, whereas in the Netherlands, orange is the color of the royal family and used for patriotic purposes.

In addition to connotations of spring, the color green is also associated with Islam. In the Christian tradition, yellow and gold are colors associated with riches and abundance. Holiness is also associated with the color blue in Egyptian, Hindu, and Christian cultures (in which blue has other associations as well). Because purple has traditionally been a difficult color to manufacture, its rarity meant that only the very wealthy, often nobility or royalty, could afford to wear it—hence its association with royals and even gods. However, some cultures, such as Thai, Brazilian, and Italian cultures, associate purple with bad luck or death. Again, this overview of colors’ different interpretations and associations is not intended as a guide for interpreting color in a visual image. Instead, consider all of the different ways in which color can be understood, some ways that the artist might intend for color to be interpreted, and the associations that colors have for you when you view a visual or digital image.

In this chapter, you have begun learning about how to interpret visual information through the lens of rhetoric. Color and its related symbolism help viewers interpret images.

Like colors, symbols are interpreted differently by individuals on the basis of their personal and cultural experiences. Here is an example of two state flags with very different symbolism: Figure 17.6 depicts the state flag of Mississippi that was adopted in 1894; Figure 17.7 depicts the one adopted in 2021. In 2021, under pressure from numerous organizations and in the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, Mississippi replaced its state flag. The 1894 flag included the battle flag of the Confederacy , referencing Mississippi’s history of secession and violence during the Civil War (1861–1865); the single blue, white, and red bands were a reference to the stripes on the American flag. This historical allusion, coupled with the state’s history of enslavement and segregation, meant that the 1894 flag served as a stark reminder of efforts to silence Black Mississippians. In fact, Mississippi did not formally ratify the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution—proposed in 1865 to abolish slavery—until 2013, and the state remained segregated long after the Supreme Court outlawed the practice.

Mississippi continued to use the 1894 flag throughout the Reconstruction (1865–1877) and the Jim Crow laws (ca. 1877–c. 1950) and civil rights (1950s and 1960s) eras despite multiple and sustained efforts to remove any reference to the Confederate flag. In 2020, the increasing prominence of the Black Lives Matter movement created the context in which state lawmakers were forced to consider these problems as mainstream and urgent. Further, the state came under pressure from numerous organizations, including the Southeastern Conference athletics organization (SEC), which threatened to boycott the state by no longer holding major events there if the flag were not changed.

Submitted to the legislature by Starkville-based graphic designer Rocky Vaughan (b. ca. 1977) and collaborators Sue Anna Joe , Kara Giles , and Dominique Pugh , the new flag took effect in January 2021 after voters approved it and the governor ratified it. The current flag ( Figure 17.7 ) features a central vertical band of blue, flanked by two thin gold bands and encompassed by two broader red ones. The flag’s center is dominated by a single magnolia flower, crowned by a single gold star and encircled by 20 white ones. Beneath the flower are emblazoned the words “In God We Trust.”

The gold coloring is intended to celebrate Mississippi’s contributions to the world of art, music, and literature. The white stars symbolize Mississippi’s status as the 20th state of the Union; thus, the new flag symbolizes the state’s reintegration into the Union without reference to its seditious acts in the 19th century or lingering loyalty to the beliefs that motivated them. In addition, the single gold star honors the state’s indigenous people; no reference is made to the state’s history of enslavement and racism.

Thinking critically about color and symbol, ask yourself these questions:

- Does the color enhance or distort the reality of the image?

- Imagine the image in shades of black, white, and gray. What would be lost and what would be gained if color were subtracted?

- Does the color work with or against the other compositional elements?

- What symbols are incorporated into the image? How might those symbols be interpreted in various contexts?

- What, if any, is the significance of referencing Indigenous but not Black Americans on the current flag?

Selecting and Incorporating Digital and Visual Media

In addition to analyzing visual and digital media, you may be asked to find, create, or manipulate such materials for a variety of situations and audiences. Following are some considerations to keep in mind, including copyright issues, appropriate selections, and technical manipulations .

Intellectual property laws are complicated, change frequently, and vary by country. Sharing an image is similar to quoting a text, with one exception: you must not only cite the author in a reference list or bibliography but also secure permission to use the image. To be safe, unless an image explicitly states that you are free to share it (public domain), assume it is protected by copyright.

The texts you write will have varying degrees of formality and require different levels of diction (word choice), syntax (sentence structure), content, and tone. Similarly, the images you select should reflect the tone , or attitude, that you wish to convey in your text. Ask yourself these questions to decide whether an image is appropriate for your text:

What is the image’s purpose? Include images only if they add to or supplement the text. Do not add images simply as “filler” or for audience entertainment. Such materials are more likely to confuse or distract readers than they are to enlighten or inform them.

Is the image humorous or sarcastic? Humor has value as entertainment by keeping the audience interested and engaged in your text and making it more memorable. However, determining what makes something funny is deeply personal. An image you find funny could be read with confusion or even offense by someone else. In formal communications, humor and sarcasm are better avoided because of the risk of misunderstanding. In creative contexts, you have greater latitude.

Does the image include text? Because you are already creating a text, you may wish to question the value of inserting an image with text. Consider what information the image provides in addition to the text. For example, in Figure 17.3 , the text “I can’t breathe” is enhanced by its placement on a mask and, further, by the mask’s presence on a Black woman. These details make the image with its text a valuable addition to a discussion or analysis.

Consider also the language of the text. You may be fluent in multiple languages, so an image with text in Spanish, French, or Japanese could have meaning for you. Will it have meaning for your audience? The same applies to images that include slang, jargon, or slogans with a limited shelf life. If you have to explain the image’s meaning before your readers understand it, the image is probably not worth including.

What is the image’s context? Where and when the image is placed can affect the viewer’s understanding and interpretation. A picture of poverty in one country is likely to look very different from poverty in another country. Some images can be considered universal, meaning they depict situations that have significance for all people, regardless of culture, ethnicity, or historical context. For example, an image of a mother and an infant is easily recognized by anyone anywhere and is likely to evoke similar thoughts and emotions.

What digital or technical requirements or manipulations are needed? Finally, when you think about including an image, you’ll need to consider the digital and technical requirements and manipulations necessary to do so. Aspects to consider include compatibility requirements, visibility on different devices and platforms, sizing, and placement. The technical details associated with these considerations are changing rapidly, so this chapter makes no recommendations regarding software programs or specifications. However, if an image is blurred or distorted—or invisible—the result will be confusion and frustration on the part of your reader.

Selecting an Appropriate Image

To practice selecting appropriate images, imagine you are writing an informational webpage about the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and its responsibilities in relation to the Clean Water Act . To illustrate those responsibilities, which of the following images would you use? Why? (Suggested answers follow.)

Suggested Answers

- Sample image 1 seems like an obvious choice. It depicts the name and logo of the agency you are writing about, and nothing about it is likely to be considered controversial. However, by itself, it does not convey any useful information, so its purpose is unclear.

- Sample image 2 depicts safe, clean drinking water from the tap. The glass emphasizes the clarity of the water, and its proximity to the tap shows the intimate role that water plays in daily life. It features no characters or setting, so it is not restricted by any obvious contextual clues. It is perfect for this piece.

- Sample image 3 is emotionally powerful. It depicts a woman, older and likely with a low income, holding a jar of brownish liquid. The image appears to be old, based on the coloring of the photograph, the woman’s dress, and the home in the background. Its age could help make the rhetorical point that the EPA’s enforcement of the Clean Water Act, passed in 1972, has been effective. However, its context is unclear, raising questions about its composition. When and where was the photo taken? Is it set in the United States? And what is the liquid in the jar—water? Oil? Moonshine? The image raises too many questions to be useful in this context.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/17-1-reading-images

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Ask a Librarian

Locating and Using Images for Presentations and Coursework

- Free & Open Source Images

- How to Cite Images

- Alt Text Image Descriptions

Copyright Resources

- Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States from Cornell University Library

- Copyright Overview from Purdue University

- U.S. Copyright Office

- Fair Use Evaluator

- Visual Resources Association's Statement of Fair Use of Images for Teaching, Research, and Study

- Creative Commons Licenses

Attribution

Again, the majority of images you find are under copyright and cannot be used without permission from the creator. There are exceptions with Fair Use, but this Libguide is intended to help you locate images you can use with attribution (and in some case, the images are free to use without attribution when stated, such as with stock images from pixabay). ***Please read about public domain . These images aren't under copyright, but it's still good practice to include attribution if the information is available. Attribution : the act of attributing something, especially the ascribing of a work (as of literature or art) to a particular author or artist. When you have given proper attribution, it means you have given the information necessary for people to know who the creator of the work is.

Citation General Guidelines

Include as much of the information below when citing images in a paper and formal presentations. Apply the appropriate citation style (see below for APA, MLA examples).

- Image creator's name (artist, photographer, etc.)

- Title of the image

- Date the image (or work represented by the image) was created

- Date the image was posted online

- Date of access (the date you accessed the online image)

- Institution (gallery, museum) where the image is located/owned (if applicable)

- Website and/or Database name

Citing Images in MLA, APA, Chicago, and IEEE

- Directions for citing in MLA, APA, and Chicago MLA: Citing images in-text, incorporating images into the text of your paper, works cited APA 6th ed.: Citing images in-text and reference list Chicago 17th ed.: Citing images footnotes and endnotes and bibliography from Simon Fraser University

- How to Cite Images Using IEEE from the SAIT Reg Erhardt Library

- Image, Photograph, or Related Artwork (IEEE) from the Rochester Institute of Technology Library

Citing Images in Your PPT

Currently, citing images in PPT is a bit of the Wild West. If details aren't provided by an instructor, there are a number of ways to cite. What's most important is that if the image is not a free stock image, you give credit to the author for the work. Here are some options:

1. Some sites, such as Creative Commons and Wikimedia, include the citation information with the image. Use that citation when available. Copy the citation and add under the image. For example, an image of a lake from Creative Commons has this citation next to it: "lake" by barnyz is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 .

2. Include a marker, such as Image 1. or Figure 1., and in the reference section, include full citation information with the corresponding number

3. Include a complete citation (whatever the required format, such as APA) below the image

4. Below the image, include the link to the online image location

5. Hyperlink the title of the image with the online image location

- << Previous: Free & Open Source Images

- Next: Alt Text Image Descriptions >>

- Last Edited: Jun 8, 2023 3:28 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.purdue.edu/images

Finding and referencing images: Referencing images

- Referencing images

- Finding images and videos

Introduction

In this guide, ' IMAGE ' is used to refer to any visual resource such as a diagram, graph, illustration, design, photograph, or video. They may be found in books, journals, reports, web pages, online video, DVDs and other kinds of media. This guide also refers to ‘ CREATOR ’. This could be an illustrator, photographer, author or organisation.

The examples are presented in Harvard (Bath) style and offer general guidelines on good practice. For essays, project reports, dissertations and theses, ask your School or Department which style they want you to use. Different referencing styles require the use of similar information but will be formatted differently. For more information on other referencing styles, visit our referencing guide .

Using images to illustrate or make clear the description and discussion in your text is useful, but it is important that you give due recognition to the work of other people that you present with your own. This will help to show the value of their work to your assignment and how your ideas fit with a wider body of academic knowledge.

It is just as important to properly cite and reference images as it is the journal articles, books and other information sources that you draw upon. If you do not, you could find yourself accused of plagiarism and/or copyright infringement.

Using images and copyright

For educational assignments it is sufficient to cite and reference any image used. If you publish your work in any way , including posting online, then you will need to follow copyright rules. It is your responsibility to find out whether, and in what ways, you are permitted to use an image in your coursework or publications. Please refer to our copyright guidance and ask for further assistance if you are unsure.

Some images are given limited rights for reuse by their creators. This is likely to be accompanied with a requirement to give recognition to their work and may limit the extent to which it can be modified. The ‘Creative Commons’ copyright licensing scheme offers creators a set of tools for telling people how they wish their work to be used. You can find out more about the different kinds of licence, and what they mean, on the organisation’s web pages .

What is a caption?

Any image that you use should be given a figure number and a brief description of what it is. Permission for use of an image in a published work should be acknowledged in the figure caption. Some organisations will require the permission statement to be given exactly as they specify. If they are required, permissions need to be stated in addition to the citing and referencing guidance given below.

Referencing images in PowerPoint slides

For a presentation you should include a brief citation under the image. Keep a reference list to hand (e.g. hidden slide) for questions. Making a public presentation or posting it online is publishing your work. You must include your references and observe permission and copyright rules.

Example of a caption

Figure 1. Library book. Reproduced with permission from: Rogers, T., 2015, University of Bath Library

Citing and referencing images

Citing images from a book or journal article.

If you wish to refer to images used in a book or journal, they are cited in the same way as text information , for example:

The functions and flow of genetic information within a plant cell can be visualised as a complex system (Campbell et al., 2015, pp. 282-283).

Campbell et al. (2015, pp. 282-283) have clearly illustrated how a plant cell functions.

If you were to include this example in an essay the caption and citation below the image would look similar to this:

Figure 7. The functions and flow of genetic information within a plant cell (Campbell et al., 2015, pp. 282-283).

The reference at the end of the work would be as recommended for a book reference in our general referencing guide .

For a large piece of work such as a dissertation, thesis or report, a list of figures may be required at the front of the work after the contents page. Check with your department for information on specific requirements of your work.

Google images

When referencing an image found via Google you need to make sure that the information included in your reference relates to the original website that your search has found. Click on the image within the results to get to the original website and take your reference information from there. Take care to use credible sources with good quality information.

Citing and referencing images from a web page

If you use an image from a web page, blog or an online photograph gallery you should reference the individual image . Cite the image creator in the caption and year of publication. The creator may be different from the author of the web page or blog. They may be individual people or an organisation. Figure 2 below gives an example of an image with a corporate author:

List the image reference within your references list at the end of your work, using the format:

NASA, 2015. NASA astronaut Tim Kopra on Dec. 21 spacewalk [Online]. Washington: NASA. Available from: https://www.nasa.gov/image-feature/nasa-astronaut-tim-kopra-on-dec-21-spacewalk [Accessed 7 January 2015].

Wikipedia images

If you want to reference an image included in a Wikipedia article, double-click on the image to see all the information needed for your reference. This will open a new page containing information such as creator, image title, date and specific URL. The format should be:

Iliff, D., 2006. Royal Crescent in Bath, England - July 2006 [Online] . San Francisco: Wikimedia Foundation. Available from: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Royal_Crescent_in_Bath,_England_-_July_2006.jpg [Accessed 7 January 2016].

Images and designs from exhibitions, museums or archives

If you want to reference an image or design that you have found in an exhibition, museum or archive, then you also need to observe copyright rules and reference the image correctly. The format is:

For example, if you want to reference an old black and white photograph from 1965 that is held in an archive at the University of Bath:

Bristol Region Building Record, 1965. Green Park House (since demolished), viewed from southwest [Photograph]. BRBR, D/877/1. Archives & Research Collections, University of Bath Library.

NB if you were to reproduce this archive image in your work, or any part of it (rather than just cite it), you would also need to note ‘© University of Bath Library’. This copyright note should be added to the image caption along with the citation.

Referencing your own images

If you take a photograph, you do not have to reference it. For sake of clarity you may want to add “Image by author” to the caption. If you create an original illustration or a diagram that you have produced from your own idea then you do not have to cite or reference them. If you generate an image from a graphics package, for example a molecular structure from chemistry drawing software, you do not need to cite the source of the image.

Referencing images that you adapt from elsewhere

If you use someone else’s work for an image then you must give them due credit. If you reproduce it by hand or using graphics software it is the same as if you printed, scanned or photocopied it. You must cite and reference the work as described in this guide. If the image is something that you have created in an earlier assignment or publication you need to reference earlier piece of work to avoid self-plagiarism. If you want to annotate information to improve upon, extend or change an existing image you must cite the original work. However, you would use the phrase ‘adapted from’ in your citation and reference the original work in your reference list.

AI generated images

If you have used an AI tool to generate an image you must acknowledge that tool as a source (see point 7 of the academic integrity statement ).

This content is not recoverable; it cannot be linked or retrieved. There is no published source that you can reference directly. Instead you would give an in-text, ‘personal communications’ citation , as described in part 15 of our 'Write a citation' guidance (from the Harvard Bath guide). This type of citation includes the author details followed by (pers. comm.) and the date of the communication.

For example, an image of a shark in a library generated with Craiyon with a ‘personal communications’ citation included in the image caption:

Figure 3. Shark in a library image generated using an AI tool (Craiyon, AI Image Generator (pers. comm.) 14 July 2022).

Online images and resources for your work

The library has compiled a list of useful audio-visual resources, including images, that can be used for essays or assignments. Visit the ' finding images and videos ' tab of this guide to find out more.

- Next: Finding images and videos >>

- Last Updated: Nov 6, 2023 3:07 PM

- URL: https://library.bath.ac.uk/images

How to Write an Image Analysis Essay in 6 Easy Steps

Writing an analysis of a picture can be a little daunting, especially if analyzing and essay writing are not your strengths. Not to worry. In this tutorial, you’ll learn how to do it, even if you’re a beginner.

To write an effective visual analysis, all you need to do is break the image into parts and discuss the relationship between them. That’s it in a nutshell.

Writing an image analysis essay, whether you’re analyzing a photo, painting, or any other kind of an image, is a simple, 6-step process. Let me take you through it.

Together, we’ll analyze a simple image and write a short analysis essay based on it. You can analyze any image, such as a photo or a painting, by following these steps.

Here is a simple image we’ll analyze.

And we’re ready for the…

6 Steps to Writing a Visual Analysis Essay

Step 1: Identify the Elements

When you look at this image, what do you see?

Right now, you are not just a casual observer. You are like a detective who must inspect things thoroughly and be careful not to miss any details.

So, let’s put on our Sherlock Holmes hat, grab a magnifying glass, and make a list of all the major and some minor elements of this picture.

What do we observe?

- Children. How many? Four.

- Children’s hands. Four pairs.

Great. These are all human elements. In fact, it would be useful for us to have two categories of elements: human and non-human.

When we group elements into categories, it will help us later when we’ll be writing the essay. Categories make it easier to think about the elements.

What other elements do we see?

- The hands are holding soil.

- Each handful of soil also has a tiny plant in it.

- Finally, we see the green lawn or ground on which the children stand.

These are all of the obvious elements in the image. But can we dig deeper and observe more?

Again, wearing our Sherlock Holmes hat, our job is to gather information that may not be immediately obvious or noticeable.

Let’s take another look, using our detective tentacles:

- The children’s hands are arranged in a circle.

- The children’s skin color varies from lighter to darker.

- The children wear summer clothes.

You may have noticed these elements even when you first saw the image. In that case, great job!

It looks like we’ve covered all the elements. We’re ready to move on to the next step.

Step 2. Detect Symbols and Connections

What does Sherlock Holmes or any good detective do after basic observation? It is time to think and use our logic and imagination.

We will now look for symbols and any connections or relationships among the elements.

Identifying Symbols

- Children symbolize future and hope.

- Their hands form a circle, creating a unifying effect. The symbol is unity, and there is power in unity.

- Children’s hands hold soil, and soil symbolizes earth, perhaps planet Earth.

- The earth holds young plants which symbolize the environment and ecology.

- The young plants also symbolize youth and the future.

- The children wear summer clothes, and summer symbolizes happiness and freedom because this is when children are on vacation and enjoy life.

Great. Now, let’s see if we can make some connections and identify some relationships among the elements and symbols.

We will use our imagination to put together some kind of a meaning.

In analyzing an image, we want to understand what the creator or the artist is trying to convey.

Do artists and photographers always want to convey something or is it sometimes just a picture?

It doesn’t matter because we never know what the artist really thought when creating the work . We’re not mind readers.

But we can always gather meaning using our own logic and imagination. We can derive meaning from any image. And that’s all we need to do to write an analysis essay.

Finding Connections and Relationships

Let’s allow our imagination to roam free and write down a few thoughts. Some ideas will be more obvious than others.

- This entire image seems to be about the future of the environment.

- Why is this future important? It’s important because of the future generations, symbolized by the children.

- A strong sense of long-term future is conveyed because not only do the children hold plants, but these are baby plants. The message is “children hold future generations.”

- The variety of skin colors implies diversity. Also, the hands form a circle. Together, these two elements can mean: “global diversity.”

As you can see, we can derive really interesting meaning from even a simple image.

We did a great job here and now have plenty of material to work with and write about. It’s time for the next step.

Step 3. Formulate Your Thesis

In this step, your task is to put together an argument that you will support in your essay. What can this argument be?

The goal of writing a visual analysis is to arrive at the meaning of the image and to reveal it to the reader.

We just finished the analysis by breaking the image down into parts. As a result, we have a pretty good idea of the meaning of the image.

Now, we need to take these parts and put them together into a meaningful statement. This statement will be our thesis.

Let’s do it.

Writing the Thesis

This whole picture may mean something like the following:

This sounds good. Let’s write another version:

This sounds good, as well. What is the difference between the two statements?

The first one places the responsibility for the future of the planet on children.

The second one places this responsibility on the entire humanity.

Therefore, the second statement just makes more sense. Based on it, let’s write our thesis.

We now have our thesis, which means we know exactly what argument we will be supporting in the essay.

Step 4: Write the Complete Thesis Statement

While a thesis is our main point, a thesis statement is a complete paragraph that includes the supporting points.

To write it, we’ll use the Power of Three. This means that we are going to come up with three supporting points for our main point.

This is where our categories from Step 1 will come in handy. These categories are human and non-human elements. They will make up the first two supporting points for the thesis.

The third supporting point can be the relationships among the elements.

We can also pick a different set of supporting points. Our job here is to simply have three supporting ideas that make sense to us.

For example, we have our elements, symbols, and connections. And we can structure the complete argument this way:

All we really need is one way to organize our thoughts in the essay. Let’s go with the first version and formulate the supporting points.

Here’s our main point again:

Here are our supporting points:

- The photographer uses the image of children to symbolize the future.

- The non-human elements in the photo symbolize life and planet Earth.

- The author connects many ideas represented by images to get the message across.

Now we have everything we need to write the complete thesis statement. We’ll just put the main and the supporting statements into one paragraph.

Thesis Statement

Step 5: write the body of your essay.

At this point, we have everything we need to write the rest of the essay. We know that it will have three main sections because the thesis statement is also our outline.

We’re ready to write the body of the essay. Let’s do it.

Body of the Essay (3 paragraphs)

“The author of this photograph chose children and, more specifically, children’s hands in order to convey his point. In many, if not all human cultures, children evoke the feelings of hope, new beginnings, and the future. This is why people often say, ‘Children are our future.’ Furthermore, the children in the photo are of different ethnic backgrounds. This is evident from their skin colors, which vary from lighter to darker. This detail shows that the author probably meant children all over the world.

The non-human elements of the picture are the plants and the soil. The plants are very young – they are just sprouts, and that signifies the fragility of life. The soil in which they grow evokes the image of our planet Earth. Soil also symbolizes fertility. The clothes the children wear are summer clothes, and summer signifies freedom because this is the time of a long vacation for school children. Perhaps the author implies that the environment affects people’s freedom.

Finally, the relationships and connections among these elements help the photographer convey the message that humans should be mindful of their decisions today to ensure a bright future for the planet. This idea can be arrived at by careful examination. First, the children’s hands are arranged in a circle, which is a symbol of our planet and also signifies the power of unity. The future depends on people’s cooperation. Second, the children seem to be in the process of planting. The author emphasizes long-term future because the children hold baby plants. In other words, they ‘hold the future of other children’ in their hands. Third, the placement of the sprouts, which rest inside the soil in children’s hands, is a strong way to suggest that the future of the ecology is literally ‘in our hands.’”

Step 6. Add an Introduction and a Conclusion

Before we continue, I have an entire detailed article on how to write an essay step-by-step for beginners . In it, I walk you through writing every part of an essay, from the thesis to the conclusion.

Introduction

That said, your introduction should be just a sentence or two that go right before you state the thesis.

Let’s revisit our thesis statement, and then write the introduction.

And now let’s write an introductory sentence that would make the opening paragraph complete:

Now, if you read this intro sentence followed by the thesis statement, you’ll see that they work great together. And we’re done with the opening paragraph.

Your conclusion should be just a simple restatement. You can conclude your essay in many ways, but this is the basic and time-proven one.

Let’s do it:

We simply restated our thesis here. Your conclusion can be one or more sentences. In a short essay, a sentence will suffice.

Guess what – we just wrote a visual analysis essay together, and now you have a pretty good idea of how to write one.

Hope this was helpful!

How to Write a 300 Word Essay – Simple Tutorial

How to expand an essay – 4 tips to increase the word count, 10 solid essay writing tips to help you improve quickly, essay writing for beginners: 6-step guide with examples, 6 simple ways to improve sentence structure in your essays.

Tutor Phil is an e-learning professional who helps adult learners finish their degrees by teaching them academic writing skills.

You Might Like These Next...

How to Write a Summary of an Article in 5 Easy Steps

https://youtu.be/mXGNf8JMY4Y When you’re summarizing, you’re simply trying to express something in fewer words. I’m Tutor Phil, and in this tutorial, I’ll show you how to summarize an...

How to Write Strong Body Paragraphs in an Essay

https://youtu.be/OcI9NKg_cEk A body paragraph in an essay consists of three parts: topic sentence, explanation, and one or more examples. The topic sentence summarizes your paragraph completely...

Extended Essay Resources: Finding and Citing Images

- Research Video Tutorials

- Video Tutorials

- In-text Citations

- Finding and Citing Images

- Plagiarism VS. Documentation

- MiniLessons

- Human Rights News

- Peace & Conflict News

- Primary Sources

- Introductory Resources

- Narrowing Your Topic

- Subject Resources

Using Images in a Presentation

Is the image for decoration? If yes, follow below. No? Keep scrolling.

1. Royalty-free clipart does not require an attribution.

2. Public domain images don't require an attribution. However, it's considered good form to allow your audience to find your images. You should make an attribution in a caption beneath or adjacent to the image that states the title/name of the image, the author/creator (if you can find it), the source, and the license. Then h yperlink the title of the image and author to the source of the image. See the box below for more information on creating attributions. For example:

Lightbulb by ColiN00B is licensed under Creative Commons CC0

Photo by ColiN00B on Pixabay

Is the image for analysis or to support your argument? If yes, follow below.

1. In this case, you are using the image in an academic way so you should provide an MLA citation. Remember, a URL is not a citation. You must provide a citation for an image in the same way that you make a citation for a book or a website. Use NoodleTools to help. You can list citations like this:

Creator’s Last name, First name. “Title of the digital image.” Title of the website , First name Last name of any contributors, Version (if applicable), Number (if applicable), Publisher, Publication date, URL.

Vasquez, Gary A. Photograph of Coach K with Team USA. NBC Olympics , USA Today Sports, 5 Aug. 2016, www.nbcolympics.com/news/rio-olympics-coach-ks-toughest-test-or-lasting-legacy.

2. You can put the citation as a caption beneath the image. You can also list it with your other references in your "Works Cited" list.

Creative Commons and Royalty-Free Media

- 10 Websites with Free Stock Video Footage Free royalty free stock footage is hard to find but we have compiled a list of some of the better sites that are offering a selection of video clips available for download and use in personal and commercial projects.

- Compfight Locate the visual inspiration you need. Super fast!

- Creative Commons Search for images and videos with a Creative Commons re-use license on multiple websites.

- Flickr Commons Images with no known copyright restrictions from various cultural heritage institutions

- Getty Search Gateway The Getty Search Gateway allows users to search across several of the Getty repositories, including collections databases, library catalogs, collection inventories, and archival finding aids.

- Google Images Choose "Tools" > Choose "Usage Rights" > Choose "Labeled for reuse"

- Morguefile Morguefile is a free photo archive “for creatives, by creatives.”

- Open Clipart Free, public domain clip art.

- Pexels.com Pexels provides high quality and completely free stock photos licensed under the Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license.

- Photos for Class Search now to download properly attributed, Creative Commons photos for school!

- Pixabay Pixabay is a vibrant community of creatives, sharing copyright free images and videos. All contents are released under Creative Commons CC0, which makes them safe to use without asking for permission or giving credit to the artist - even for commercial purposes.

- Snappygoat.com Over 13,000,000 free public domain images.

- Tineye Have an image but not sure where it's from? Try this reverse image search.

- Unsplash Over 1,000,000 free (do-whatever-you-want) high-resolution photos brought to you by the world’s most generous community of photographers.

- Video Assets from Camtasia Royalty-free elements to enhance your videos in Camtasia

- Wikimedia Commons Over 40 million freely usable media files. Attributions provided. This is a great source for finding historical images, as well.

How to make attributions next to an image

- Creative Commons - Best practices for attribution You can use CC-licensed materials as long as you follow the license conditions. One condition of all CC licenses is attribution. Here are some good (and not so good) examples of attribution.

If you use images, such as photographs or clipart , in your presentation, you should also credit the source of the image. Do not reproduce images without permission. See the box "Finding Public Domain Images" in this guide to find sources for images that are "public use".

Use the acronym TASL to remember how to attribute images:

T - Title/Description

A - Author or creator

S - Source & date (Name of the website the image is from)

L - License or location (Creative Commons license or URL)

For example...

" Satellites See Unprecedented Greenland Ice Sheet Surface Melt " by NASA Goddard Space Flight Center is licensed under CC by 2.0

Title: Satellites See Unprecedented Greenland Ice Sheet Surface Melt Author: NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Source: Flickr (linked in title) License: CC by 2.0

Quick Guide

Citing images in mla.

- OWL Purdue - Images

- OWL Purdue - Tables and Figures The purpose of visual materials or other illustrations is to enhance the audience's understanding of information in the document and/or awareness of a topic. Writers can embed several types of visuals using most basic word processing software: diagrams, musical scores, photographs, or, for documents that will be read electronically, audio/video applications.

- OWL Purdue - Other types of sources Several sources have multiple means for citation, especially those that appear in varied formats: films, DVDs, T.V shows, music, published and unpublished interviews, interviews over e-mail; published and unpublished conference proceedings.

Public Domain Images

These images are in the public domain. They are free to use, but you must make an attribution or citation.

- << Previous: In-text Citations

- Next: Plagiarism VS. Documentation >>

- Last Updated: Aug 15, 2023 3:34 PM

- URL: https://libguides.aisr.org/extendedessay

The leading authority in photography and camera gear.

Become a better photographer.

12.9 Million

Annual Readers

Newsletter Subscribers

Featured Photographers

Photography Guides & Gear Reviews

How to Create an Engaging Photo Essay (with Examples)

Photo essays tell a story in pictures. They're a great way to improve at photography and story-telling skills at once. Learn how to do create a great one.

Learn | Photography Guides | By Ana Mireles

Photography is a medium used to tell stories – sometimes they are told in one picture, sometimes you need a whole series. Those series can be photo essays.

If you’ve never done a photo essay before, or you’re simply struggling to find your next project, this article will be of help. I’ll be showing you what a photo essay is and how to go about doing one.

You’ll also find plenty of photo essay ideas and some famous photo essay examples from recent times that will serve you as inspiration.

If you’re ready to get started, let’s jump right in!

Table of Contents

What is a Photo Essay?

A photo essay is a series of images that share an overarching theme as well as a visual and technical coherence to tell a story. Some people refer to a photo essay as a photo series or a photo story – this often happens in photography competitions.

Photographic history is full of famous photo essays. Think about The Great Depression by Dorothea Lange, Like Brother Like Sister by Wolfgang Tillmans, Gandhi’s funeral by Henri Cartier Bresson, amongst others.

What are the types of photo essay?

Despite popular belief, the type of photo essay doesn’t depend on the type of photography that you do – in other words, journalism, documentary, fine art, or any other photographic genre is not a type of photo essay.

Instead, there are two main types of photo essays: narrative and thematic .

As you have probably already guessed, the thematic one presents images pulled together by a topic – for example, global warming. The images can be about animals and nature as well as natural disasters devastating cities. They can happen all over the world or in the same location, and they can be captured in different moments in time – there’s a lot of flexibility.

A narrative photo essa y, on the other hand, tells the story of a character (human or not), portraying a place or an event. For example, a narrative photo essay on coffee would document the process from the planting and harvesting – to the roasting and grinding until it reaches your morning cup.

What are some of the key elements of a photo essay?

- Tell a unique story – A unique story doesn’t mean that you have to photograph something that nobody has done before – that would be almost impossible! It means that you should consider what you’re bringing to the table on a particular topic.

- Put yourself into the work – One of the best ways to make a compelling photo essay is by adding your point of view, which can only be done with your life experiences and the way you see the world.

- Add depth to the concept – The best photo essays are the ones that go past the obvious and dig deeper in the story, going behind the scenes, or examining a day in the life of the subject matter – that’s what pulls in the spectator.

- Nail the technique – Even if the concept and the story are the most important part of a photo essay, it won’t have the same success if it’s poorly executed.

- Build a structure – A photo essay is about telling a thought-provoking story – so, think about it in a narrative way. Which images are going to introduce the topic? Which ones represent a climax? How is it going to end – how do you want the viewer to feel after seeing your photo series?

- Make strong choices – If you really want to convey an emotion and a unique point of view, you’re going to need to make some hard decisions. Which light are you using? Which lens? How many images will there be in the series? etc., and most importantly for a great photo essay is the why behind those choices.

9 Tips for Creating a Photo Essay

Credit: Laura James

1. Choose something you know

To make a good photo essay, you don’t need to travel to an exotic location or document a civil war – I mean, it’s great if you can, but you can start close to home.

Depending on the type of photography you do and the topic you’re looking for in your photographic essay, you can photograph a local event or visit an abandoned building outside your town.

It will be much easier for you to find a unique perspective and tell a better story if you’re already familiar with the subject. Also, consider that you might have to return a few times to the same location to get all the photos you need.

2. Follow your passion

Most photo essays take dedication and passion. If you choose a subject that might be easy, but you’re not really into it – the results won’t be as exciting. Taking photos will always be easier and more fun if you’re covering something you’re passionate about.

3. Take your time

A great photo essay is not done in a few hours. You need to put in the time to research it, conceptualizing it, editing, etc. That’s why I previously recommended following your passion because it takes a lot of dedication, and if you’re not passionate about it – it’s difficult to push through.

4. Write a summary or statement

Photo essays are always accompanied by some text. You can do this in the form of an introduction, write captions for each photo or write it as a conclusion. That’s up to you and how you want to present the work.

5. Learn from the masters

How Much Do You REALLY Know About Photography?! 🤔

Test your photography knowledge with this quick quiz!

See how much you really know about photography...

Your answer:

Correct answer:

SHARE YOUR RESULTS

Your Answers

Making a photographic essay takes a lot of practice and knowledge. A great way to become a better photographer and improve your storytelling skills is by studying the work of others. You can go to art shows, review books and magazines and look at the winners in photo contests – most of the time, there’s a category for photo series.

6. Get a wide variety of photos

Think about a story – a literary one. It usually tells you where the story is happening, who is the main character, and it gives you a few details to make you engage with it, right?

The same thing happens with a visual story in a photo essay – you can do some wide-angle shots to establish the scenes and some close-ups to show the details. Make a shot list to ensure you cover all the different angles.

Some of your pictures should guide the viewer in, while others are more climatic and regard the experience they are taking out of your photos.

7. Follow a consistent look

Both in style and aesthetics, all the images in your series need to be coherent. You can achieve this in different ways, from the choice of lighting, the mood, the post-processing, etc.

8. Be self-critical

Once you have all the photos, make sure you edit them with a good dose of self-criticism. Not all the pictures that you took belong in the photo essay. Choose only the best ones and make sure they tell the full story.

9. Ask for constructive feedback

Often, when we’re working on a photo essay project for a long time, everything makes perfect sense in our heads. However, someone outside the project might not be getting the idea. It’s important that you get honest and constructive criticism to improve your photography.

How to Create a Photo Essay in 5 Steps

Credit: Quang Nguyen Vinh

1. Choose your topic

This is the first step that you need to take to decide if your photo essay is going to be narrative or thematic. Then, choose what is it going to be about?

Ideally, it should be something that you’re interested in, that you have something to say about it, and it can connect with other people.

2. Research your topic

To tell a good story about something, you need to be familiar with that something. This is especially true when you want to go deeper and make a compelling photo essay. Day in the life photo essays are a popular choice, since often, these can be performed with friends and family, whom you already should know well.

3. Plan your photoshoot

Depending on what you’re photographing, this step can be very different from one project to the next. For a fine art project, you might need to find a location, props, models, a shot list, etc., while a documentary photo essay is about planning the best time to do the photos, what gear to bring with you, finding a local guide, etc.

Every photo essay will need different planning, so before taking pictures, put in the required time to get things right.

4. Experiment

It’s one thing to plan your photo shoot and having a shot list that you have to get, or else the photo essay won’t be complete. It’s another thing to miss out on some amazing photo opportunities that you couldn’t foresee.

So, be prepared but also stay open-minded and experiment with different settings, different perspectives, etc.

5. Make a final selection