Public Opinion: Influence of the Media Essay

Thesis statement.

Media plays a central role in forming opinions of individuals, reinforcing their beliefs, and affecting perception. Despite its use of new technology, such as video cameras and bodycams, news present events in a biased manner, which falls in line with the political agendas of its creators. The influence of news coverage, presentation and narratives can be felt within the judicial system as well. The opinions and actions of active trial participants, such as judges, jury, defenders and prosecutors can all be shaped by current news cycles.

The main purpose of mass media is to provide people with information about recent events and other topics they may find relevant. With the development of technology, emergence of the television and the internet, it has become easier than ever to discover events all around the globe. Be it something that happens in one’s neighborhood, or on another continent, individuals are able to receive information about the daily happenings of the world. However, the actual accuracy of media reporting, news and other public outlets, as well as their role in shaping public opinion varies greatly.

Despite the common perception of news reporting as accurate or factual, media is able to shape existing events and facts into a specific narrative, one that which more closely aligns with said media outlet’s goals or political disposition. This is concerning when one takes the role of media in shaping public perception into account. For the purposes of limiting the scope of discussion to a reasonable standard, only American news media and events will be discussed within this work. First, the role of the media in shaping public opinion will be discussed, setting a suitable platform to consider the effect of specific tools, such as video footage, in understanding events. Afterwards, it will be necessary to consider the public view and portrayal of a number of recent events, all of which can be seen as controversial.

Role of the Media in the Public Opinion

As mentioned previously, the main role of media throughout the years is to inform the population and enhance the public understanding of events. This definition concerns primarily the stated role of media outlets, not their actual effect or the variety of other purposes they fulfill. In their essence, news media outlets work in providing people with a complete framework to understand the world. In order to navigate the complicated field of world events, inform their individual decisions and viewpoints, people need news. The media has a capability to condense events people may have not experienced for themselves in an easily digestible container, one which individuals are able to consume daily.

It is important to note, however, that each news media outlet is created by people, and is not exempt from bias. Each major news publication or broadcasting organization has its own political leaning, which often informs its reporting on certain issues. This is true of most TV media broadcasts, newspapers, and social media news groups. Therefore, a single event that is reported on by a number of different news outlets will receive proportionally wide coverage, ranging in opinion and focus. This can be seen even in the most recent case, the overturning of Roe v. Wade, a monumental legislative decision. Most of the democrat-leaning news media considered the decision to be a mistake, speculating on the impact it would have on abortion clinics around the country. At the same time, republican news sources largely celebrated the change, citing it as a “moment of liberation” and a necessity. The event that news outlets are covering is the same, while its portrayal remains drastically different.

This tendency has a complex effect on the public. Various media outlets work to confirm the pre-existing biases of individuals, present new information in a way that they will find acceptable, and provide certain perspectives on events around the nation. According to current research, people are more likely to believe stories from news outlets they already know and trust, meaning those that are closely aligned with their political position. The believability of a certain story depends primarily not on its contents, but on who reports on it. This trend shows that people go to news outlets not to change their perspective, but to affirm existing biases while also keeping up with recent events.

After confirming this observation, it can be further argued that specific media individuals consume affects the public opinion. Examining studies that evaluate public perception of certain topics and events gives more insight into the capacity of media to affect individuals. According to research into American’s sentiments regarding China, more than half of all opinions expressed fall in line with the portrayal of China by the New York Times. Similarly, people also take information and sentiments from the media regarding other topics, including political decisions, crimes, and legislative changes.

Effect of Video Footage on Public and the Prosecution

Body cameras, as well as video footage, is largely understood as a step toward better law enforcement accountability, an important tool in understanding the truth of many events. However, the use of video footage as primary evidence does not guarantee a more full or honest portrayal of events. On the contrary, the reliance on body cam footage, or video footage often goes against the need to critically examine important events, and the need to pursue different perspective. With the presence of available visual evidence, both the public and the justice system become liable to dismissing further examination of a case. As discussed in the article on the topic, body camera footage only provides a retelling of events from the point of view of the police officer, which is a problem. Due to the way human perception works, viewers generally find it easier to sympathize with the person who shares their point of view. Because police officer body cams always take footage from the view of an officer on duty, their presentation makes the police more sympathetic. Another issue that is not discussed in its full capacity is the ability of police officers to turn off their cameras. In many controversial cases, such as the recent Adam Toledo Shooting, the police have turned off their body cameras, per orders, allowing them to murder a young child without any visual evidence of the crime. In situations such as this, the presence of body cameras does not effectively enhance police accountability, or protect citizens from brutality.

In addition, the use of body cameras could not fulfill its primary purpose effectively. According to past trials of police officers on accounts of police brutality, even visual evidence of unwarranted gun use or unnecessary escalation on the part of the police did not lead to successful convictions. In many cases, existing footage is insufficient in leading to a guilty verdict. Alternatively, there are also cases where

Case Analysis

Ahmaud arbery.

The Ahmaud Arbery case was among the many controvertial racially-charged murder cases of the recent years. Surrounded by unwillingness of the legal system to question the actions of two white men, both the investigation and the court case have proceeded with great difficulty. On February 23, 2020 Ahmaud Arbery was shot after an encounter with Gregory and Travis McMichael. According to reports, the men took their guns and followed Arbery on the street while he was jogging. Arbery was unarmed, and the suspicion of the two man seemed to be largely based on his race. One of the men involved in the murder was a former police officer, causing the first prosecutor to rescue themselves from the case. The second prosecutor similarly left the case, further stretching out the process of bringing the men to accountability. Local newspapers used limited and incomplete information, primarily collected from an interview with Gregory McMichael, one of the perpetrators. The lack of perspective from other parties, presented the narrative of the event from the view of a single involved party, affecting how the public perceived the event. Following the local media report, prosecution continued to be unable to assemble a case. After the emergence of a video taken from a nearby car, however, the public sentiment grew louder, prompting the continuation of legal action. After a considerable time of changes and deliberation, both men, an additional participant and a previous persecutor were all criminally charged for their involvement with the case. During the trial, much contention could still be seen in the court, as the defense attorneys remained unsympathetic to Arbery’s fate, blaming the man for his death. The case displays an egregious case of legal misconduct, news media incompetence and inaction fueled by racism.

George Floyd

The recent murder of George Floyd can be mentioned as one of the most well-known and rousing stories of police misconduct of the recent years. Starting in Minneapolis, the event has sparked nation-wide civil uproar and a chain of protests, united by the desire to end police brutality. On May 25 th , police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd during detention for an alleged crime. Despite the existence of multiple eye-witnesses, the police force attempted to minimize their involvement and deny accountability, issuing a statement claiming Floyd’s death was caused by a medical emergency. After the emergence of bystander video evidence, a wave of public outrage and scrutiny came on the police force. As a result, the three policemen associated with the murder were fired. 4 days after the initial event, former policeman Chauvin is arrested and charged with murder. Amidst the growing protests, news media reports on cases of protest looting, fires and destruction. Legislative change is initiated in Minneapolis, banning chokeholds and increasing police transparency for the public. People all across the US continue to protest for police reform and structural change.

Kyle Rittenhouse

Rittenhouse’s case has emerged during one of the many police brutality protests across the US. Having arrived in Kenosha, Rittenhouse took it upon himself to aid local businesses and the police in managing the consequences of protests. Carrying a semiautomatic rifle, the man engaged in an altercation with 3 of the protesters, who reacted negatively to his presence. After being chased to a car and being attacked with a plastic bag, Rittenhouse proceeded to fatally shoot Joseph Rosenbaum and run away. Upon being confronted, he shot again, killing another individual, Anthony Huber, in the process. Rittenhouse attempted to willingly surrender to the police, who did not take him for the active shooter and left. The morning after the shooting, Rittenhouse was arrested. Faced with homicide, misdemeanor and felony charges, the man is sentenced with weapon possession as a minor and misdemeanor. Being presented with the charges, Rittenhouse pleads not guilty, beginning the trial process. After much deliberation as well as continued polarizing discussions within the media, Rittenhouse is acquitted of all charges. News media remains divided on the case, with conservative outlets standing in support with the teen, and democratic ones condemning him.

Robb Elementary

The Robb Elementary school shooting was among the many events that have called into question the efficiency of the American police force. Salvador Ramos, an Uvalde high school student, bought two AR-15 style rifles after turning 18, going on to commit a school shooting in a nearby elementary school. The man’s concerning behaviors and posts on social media have prompted no further investigation in the days prior to the shooting. Entering the building with two rifles and ammunition, Ramos killed as many as 21 people. The police response to the case has been widely criticised for its inefficiency and impracticality, which was recorded both by the news and passersby’s. Media has widely reported on the case, and questioned the decision-making skills of the police. Many officers were called onto the scene, yet failed to either locate or neutralize the perpetrator before the situation escalated. For a major part of the event, the police were struggling to coordinate their actions, bring out the necessary equipment, and open a door the shooter hid behind. After nearly 400 police officers were unable to properly fulfill their obligation, the police department has issued a public statement reflecting on their inaction.

Topps Grocery Store

The mass shooting in the Topps grocery store in Buffalo exists as one of the many examples of the danger white supremacy presents. Payton Gendron, an 18-year old at the time of the crime, shot and killed 10 black people in a predominantly black neighborhood. After being apprehended, the authorities examined the actions of the man who broadcasted the mass murder on a livestream. According to currently present information and media discussions, Gendron’s crime was racially motivated. The perpetrator plead not guilty to all charges. Much like other examples of mass shootings, the Topps shooting sparked new waves of gun control debates within the nation.

Bibliography

“Buffalo Mass Shooting Suspect Pleads Not Guilty to Federal Hate, Firearms Charges.” Reuters. Web.

“Police Responding to Uvalde School Massacre ‘failed to Prioritise Saving Innocent Lives’, Report Finds.” ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Web.

“Timeline of Events Since George Floyd’s Arrest and Murder.” AP NEWS. Web.

Bosman, Julie. “A Timeline of the Kyle Rittenhouse Shootings and His Trial.” The New York Times – Breaking News, US News, World News and Videos. Web.

Cahn, Albert F. “How Bodycams Distort Real Life.” The New York Times – Breaking News, US News, World News and Videos. Web.

Fausset, Richard, Michael Levenson, Sarah Mervosh, and Derrick B. Taylor. “Ahmaud Arbery Shooting: A Timeline of the Case.” The New York Times – Breaking News, US News, World News and Videos. Web.

Goggin, Kayla. “Defense attorneys blame Ahmaud Arbery for his own death during closing arguments.” Courthouse News Service. Web.

Huang, Junming, Gavin G. Cook, and Yu Xie. “Large-scale quantitative evidence of media impact on public opinion toward China.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8, no. 1 (2021).

Jacobo, Julia, and Nadine El-Bawab. “Timeline: How the Shooting at a Texas Elementary School Unfolded.” ABC News. Web.

Jones, Tom. “From Politico’s Scoop to America’s Reality: Media Reaction to Roe V. Wade’s Overturn.” Web.

Lopez, German. “The Failure of Police Body Cameras.” Vox. Web.

Rothwell, Jonathan. “Biased News Media or Biased Readers? An Experiment on Trust.” The New York Times. Web.

Rutz, David. “Roe V. Wade Overturned: Conservative Media Rejoices over Supreme Court Righting ‘grievous Wrong’.” Fox News. Web.

Sabella, Jen. “Why Were Police Told To Turn Off Body Cameras Minutes After Adam Toledo Shooting? It’s Standard Policy, Department Says.” Block Club Chicago. Web.

Sullivan, Becky. “Kyle Rittenhouse is Acquitted of All Charges in the Trial over Killing 2 in Kenosha.” NPR.org. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, July 18). Public Opinion: Influence of the Media. https://ivypanda.com/essays/public-opinion-influence-of-the-media/

"Public Opinion: Influence of the Media." IvyPanda , 18 July 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/public-opinion-influence-of-the-media/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Public Opinion: Influence of the Media'. 18 July.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Public Opinion: Influence of the Media." July 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/public-opinion-influence-of-the-media/.

1. IvyPanda . "Public Opinion: Influence of the Media." July 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/public-opinion-influence-of-the-media/.

IvyPanda . "Public Opinion: Influence of the Media." July 18, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/public-opinion-influence-of-the-media/.

- Ahmaud Arbery Case: Shooting Analysis

- Neutralization of Bundy, Manson and Arbery

- The Crime and Justice Impact on New Media

- Racial Reckoning and Impact of COVID-19 Pandemic

- George Zimmerman's Criminal Prosecution

- Education Establishments' Role Regarding Social Issues

- How Parents of Color Transcend Nightmare of Racism

- The Aspects of Discrimination

- Volcanic Eruption in the "Threatened" Footage

- History of Police Brutality: The Murder of George Floyd

- Impact of Social Media on Instructional Practices for Kindergarten Teachers

- Analysis of The Television Role in the 6th of January Capitol Insurrection

- The Role of Media: The Negative Side

- Internet Media Platforms and Their Role in Society

- Teen Pregnancy Due to the Impact of Entertainment Media

Home — Essay Samples — Business — Media — The Power of Media in Shaping Public Opinion

The Power of Media in Shaping Public Opinion

- Categories: Media

About this sample

Words: 1096 |

Published: Feb 7, 2024

Words: 1096 | Pages: 2 | 6 min read

Table of contents

Historical overview of media influence on public opinion, the role of media in influencing public opinion, case studies of media influence on public opinion, positive and negative effects of media influence on public opinion, enhancing media responsibility in influencing public opinion, a. agenda setting, d. persuasion, a. positive effects, b. negative effects, c. ethical considerations.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof. Kifaru

Verified writer

- Expert in: Business

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1651 words

6 pages / 2811 words

3 pages / 1552 words

1 pages / 558 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Media

Bulmer, J. G., McLeod, J. M., & Rice, R. E. (2009). Television and Political Life: Studies in Six European Countries. Springer Science & Business Media.Fulcher, J., & Scott, J. (2011). Sociology. Oxford University Press.Kitts, [...]

Cosmopolitan bias refers to the tendency to prioritize the experiences and perspectives of individuals from urban, metropolitan areas over those from rural or less densely populated areas. This bias can manifest in a variety of [...]

In Chapter 8 of Thirteen American Arguments, the author Howard Fineman delves into the pervasive influence of television in shaping public opinion and its impact on democracy. Through a blend of , cultural analysis, and critical [...]

The Mexican American identity is complex and multifaceted, shaped by a rich history, cultural heritage, and the impact of immigration. As a Mexican American, I have personally experienced the challenges and triumphs of [...]

Philippine news media is a powerful tool that is used by different organizations to connect, inform, and influence its subscribed audiences. Although this has plenty of potential for its users, it is often used to convey biased [...]

Firstly, there are many reasons why journalists have lost trust throughout the years and a lot of it I believe comes down to social media and 24/7 news. 24/7 news requires a high demand of content, this means that journalists [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Influence Insider

How media influences public opinion.

As we know, media is a powerful tool for influencing how individuals perceive life experiences and develop beliefs and behaviors. This influence can be positive or negative depending on what messages people are exposed to.

Many things about our society have contributed to the growing divide in our country. Political ideologies are one of the main drivers of this division. People who subscribe to an ideology that emphasizes individualism over socialization and equality over inequality are increasingly outnumbered by people with opposite views.

Another area where media has strong impacts is through its coverage of important issues. An example of this is the constant barrage of news stories telling us whether something or someone is good or bad for our health and wellbeing.

Given all these effects, it is no wonder that some feel overwhelmed by the amount of content media offers. There’s just too much information!

This article will focus on three major ways that media influences public opinion . These are: direct effect, indirect effect, and internal effect.

How the media affects public opinion

The way the media covers stories can have a significant impact on how people perceive events . Stories that are biased or overemphasized contribute to creating an emotional response in readers, viewers, and listeners.

This effect is very powerful because we trust sources more than we trust each other.

We look up to journalists as experts who tell us what’s going on through their lens of knowledge. Plus, they get paid for it!

So when they report about something, you should believe them. It's their job to know if what happened is important or not, so why shouldn't you?

But while there is some value in having reporters spread positive information , there is also value in being aware of all of the ways the media influences public opinion . This is your responsibility as an informed citizen.

It's your duty to do your part in protecting our democracy by using media literacy skills to evaluate reports, assess biases, and determine the true importance of a story.

Message boards

There are many ways that media influences public opinion , including through message board websites. Users of these sites become very invested in their beliefs or biases they already have before going into such forums.

Message board users typically look at pre-existing material to determine what stance an article or argument will get posted as a comment. Material that is controversial will always be left for someone to reply to, thus creating more discussion around the topic.

The way that people respond to comments also contributes to how much attention each side gets. If you read one bad thing about a product, then the opposite side’s comments will mostly focus on why the bad review is wrong and/or poor quality merchandise.

Regularly visiting such sites can lead to developing strong emotional ties to certain products. This influence is not only felt by those who own them, but also by those who simply like their style.

Social media

With the explosion of social media sites such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, it is increasingly difficult to limit young people’s access to information. As we know, exposure to different messages can have an effect on someone’s perception of the world.

Social media has become one of the most important ways that children get messages about how to live their lives. Messages spread quickly within online communities so it is very easy to see what other people are doing and thinking.

Parents must be aware of this and make sure that they control which sites their kids use by creating limited accounts for them. This will help prevent false beliefs from developing.

It was found that before social media, only 10% of teens owned a smartphone. Now almost everyone does because it offers instant access to lots of information. Teens spend up to eight hours a day on average using smartphones, making it hard to avoid encountering propaganda.

On top of this, nearly half (46%) of all teenagers own at least one item with internet access, like a phone or computer. The vast majority of these teens (95%) say they use the internet for something more than just looking at pictures and videos; 64% report using the web for activities that require software, such as working, shopping, banking, and emailing.

If you want to protect your child from misinformation, teach them how to evaluate sources thoroughly and don’t let them watch television alone.

Recent events have shown how much influence the media has on public opinion. With the constant stream of information that people are exposed to, it can be difficult to separate fact from fiction – or propaganda.

The media is a powerful tool in society. They promote an agenda, which is influenced by who is paying for advertising or what political party they belong to. Technology now makes it easy to compare different sources and get different perspectives ; you don’t need to trust just one source.

As we know, the media is not always truthful, honest, or pure. Due to this, the general public does not trust the media as much as before. People believe the media is trying to push its own agenda and product.

There was a time when only major newspapers had enough readers to make a difference with their editorial content. Now anyone with a smartphone has access to online journalism. This means that even if someone doesn’t like your candidate or team, they can find out more about him or her than originally planned!

Another problem is false balance. A company will pay for advertisement space or airtime in an effort to spread knowledge and inform the audience of both sides of an argument. But because of money involved, they may lean towards only promoting one side .

What people read

People are increasingly relying on media to inform their opinions. As technology advances, individuals have access to more sources of information than ever before.

This is good as it allows for greater knowledge diversity and options for information. It also gives you the opportunity to choose whether or not to trust what source of information you find credible and convincing.

However, this trend raises concerns about how much influence major media corporations will have over public opinion. More and more companies are offering services that allow for personalized content, which may be more influential than general, mass-appeal publications.

Major publishers make money off of advertising, so they want your attention longer term – not just for an hour while you browse through the website. This creates potential problems when their messages are not in agreement with yours.

What people watch

People spend lots of time watching media , so it has a substantial influence on how they perceive the world. If you want to change someone’s opinion about something, then you have to expose them to different perspectives.

People who are very invested in an ideology may not be open to other points of view. They may even begin to believe their own propaganda because that is all they hear.

On the contrary, individuals with diverse backgrounds can learn things from various sources.

These lessons can contradict their original beliefs, which helps them reevaluate what they thought was true before. This process is important for anyone looking to enhance their knowledge or achieve their personal goals.

The more aware you are of one area, the better you will be at your job. It is equally valuable whether you are trying to convince others of a particular argument or yourself of a certain theory.

Political campaigns

A lot of people use media to evaluate how politically active or informed you are. Whether it is looking at your YouTube subscriptions, what brands you purchase products from, how many times you visit popular political websites , or even going through your Instagram profile, there are always eyes watching!

Political advertisements can be expensive, which is another reason why politicians will spend money to make sure they have enough exposure for their campaign.

Businesses gain an understanding of what voters care about by observing what types of ads get attention and then creating ads with similar messages or concepts.

For example, most people know about the dangers of smoking due to extensive advertising, so cigarette companies invest in ads that appeal to emotions like fear or hope. They want to influence your opinion so that you either choose to smoke or not – very powerful.

Another way advertisers try to sway public opinions is by sponsoring events or sports teams. By investing in this, the advertiser supports the team or event, and people who see the advertisement may feel more inclined to show support as well.

Personal experiences

Recent studies show that it is not just what people are being told to believe by the media, but also how they perceive things due to their personal experiences.

This effect seems particularly strong when it comes to political issues.

It was mentioned earlier in this article how different media sources can offer contradictory information, making it difficult for individuals to form an opinion.

But beyond this, individual members of the public have differing perceptions based on their own life experiences.

These experiences influence whether someone is more likely to be influenced by positive or negative effects of a situation, or if they develop feelings towards certain people or groups.

For example, someone who has lived through similar situations as another person may make assumptions about them based on their personality.

Alternatively, someone might assess those people based on something they read about them in the news or heard from a friend.

Whether these assessments are accurate or not doesn’t matter much because people bring into play all sorts of other factors when trying to determine who they feel will help them achieve their goals.

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Using Media to Influence Public Opinion

After the tumultuous Watergate scandal, President Gerald R. Ford engaged the media to positively influence public opinion about the presidency.

Social Studies, U.S. History

Gerald R. Ford became the 38th President of the United States after Richard Nixon resigned due to his involvement in the Watergate scandal. Ford set out almost im mediately to rebuild the public ’s broken image of the presidency.

Gerald and Betty Ford reached the American people through media such as television, newspapers, and radio. President Ford granted the media access to his day-to-day activities. Betty Ford also stepped into the public arena, lending her voice to causes such as the Equal Rights Amendment.

Gerald and Betty Ford’s increased visibility, as they opened up their life through media, began to restore the public’s trust in the presidency.

- After assuming the presidency upon Richard Nixon’s resignation, Gerald R. Ford amassed a 71 percent approval rating.

- Betty Ford held press conferences and answered questions about women in politics, abortion rights, and the proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution.

- In September of 1974, Betty Ford was diagnosed with breast cancer and disclosed her medical condition to the world—an act that broke social conventions of the time.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Can ❤️s change minds? How social media influences public opinion and news circulation

Assistant Professor of Economics, Wilfrid Laurier University

Disclosure statement

Study 1 was approved by University College Dublin Office of Research Ethics (reference numbers: HS-E-20-110-Samahita and HS-E-20-134-Samahita) and funded by University College Dublin, Collegio Carlo Alberto, and the Einaudi Institute for Economics and Finance. Data for Study 2 was accessed through the Academic Research Twitter API. The author has no direct relevant material or financial interest that relate to the research described.

View all partners

Social media use has been shown to decrease mental health and well-being, and to increase levels of political polarization .

But social media also provides many benefits, including facilitating access to information, enabling connections with friends, serving as an outlet for expressing opinions and allowing news to be shared freely.

To maximize the benefits of social media while minimizing its harms, we need to better understand the different ways in which it affects us. Social science can contribute to this understanding. I recently conducted two studies with colleagues to investigate and disentangle some of the complex effects of social media.

Social media likes and public policy

In a recently published article , my co-researchers (Pierluigi Conzo, Laura K. Taylor, Margaret Samahita and Andrea Gallice) and I examined how social media endorsements, such as likes and retweets, can influence people’s opinions on policy issues.

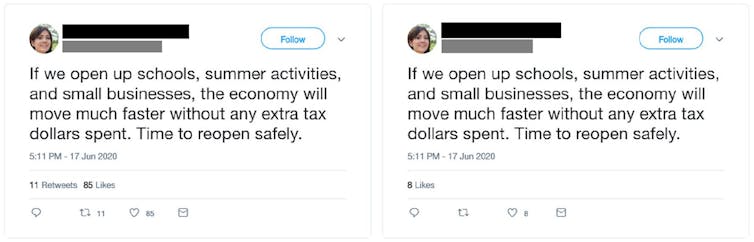

We conducted an experimental survey in 2020 with respondents from the United States, Italy and Ireland. In the study, we showed participants social media posts about COVID-19 and the tension between economic activity and public health. Pro-economy posts prioritized economic activities over the elimination of COVID-19. For instance, they advocated for reopening businesses despite potential health risks.

Pro-public health posts, on the other hand, prioritized the elimination of COVID-19 over economic activities. For example, they supported the extension of lockdown measures despite the associated economic costs.

We then manipulated the perceived level of support within these social media posts. One group of participants viewed pro-economy posts with a high number of likes and pro-public health posts with a low number of likes, while another group viewed the reverse.

After participants viewed the posts, we asked whether they agreed with various pandemic-related policies, such as restrictions on gatherings and border closures.

Overall, we found that the perceived level of support of the social media posts did not affect participants’ views — with one exception. Participants who reported using Facebook or Twitter for more than one hour a day did appear to be influenced. For these respondents, the perceived endorsements in the posts affected their policy preferences.

Participants that viewed pro-economy posts with high number of likes were less likely to favour pandemic-related restrictions, such as prohibiting gatherings. Those that viewed pro-public health posts with high number of likes were more likely to favour restrictions.

Social media metrics can be an important mechanism through which online influence occurs. Though not all users pay attention to these metrics, those that do can change their opinions as a result.

Active social media users in our survey were also more likely to report being politically engaged. They were more likely to have voted and discussed policy issues with friends and family (both online and offline) more frequently. These perceived metrics could, therefore, also have effects on politics and policy decisions.

Twitter’s retweet change and news sharing

In October 2020, a few weeks before the U.S. presidential election, Twitter changed the functionality of its retweet button . The modified button prompted users to share a quote tweet instead, encouraging them to add their own commentary.

Twitter hoped that this change would encourage users to reflect on the content they were sharing and to slow down the spread of misinformation and false news.

In a recent working paper , my co-researcher Daniel Ershov and I investigated how Twitter’s change to its user interface affected the spread of information on the platform.

We collected Twitter data for popular U.S. news outlets and examined what happened to their retweets after the change was implemented. Our study revealed that this change had significant effects on news diffusion: on average, retweets for news media outlets fell by over 15 per cent.

We then investigated whether the change affected all news media outlets to the same extent. We specifically examined whether media outlets where misinformation is more common were affected more by the change. We discovered this was not the case: the effect on these outlets was not greater than for outlets of higher journalistic quality (and if anything, the effects were slightly smaller).

A similar comparison revealed that left-wing news outlets were affected significantly more than right-wing outlets. The average drop in retweets for liberal outlets was more than 20 per cent, but the drop for conservative outlets was only five per cent. This occurred because conservative users changed their behaviour significantly less than liberal users.

Lastly, we also found that Twitter’s policy affected visits to the websites of the news outlets affected, suggesting that the new policy had broad effects on the diffusion of news.

Understanding social media

These two studies underscore that seemingly simple features can have complex effects on user attitudes and media diffusion. Disentangling the specific features that make up social media and estimating their individual effects is key to understanding how social media affects us.

Like Instagram, Meta’s new Threads platform allows users to hide the number of likes on posts. X, formerly Twitter, has just rolled out a similar feature by allowing paid users to hide their likes. These decisions can have important implications for political discourse within the new social network.

At the same time, subtle changes to platforms’ design can have unintended consequences which depend on how users respond to these policies. Social scientists can play an important role in furthering our understanding of these nuanced effects of social media.

- Social media

- Public perception

- social media politics

- Social media likes

- Social media apps

- Social media use

- Listen to this article

- X (formerly Twitter)

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

POLSC101: Introduction to Political Science

How mass media forms public opinion.

As described in the last section, the "media" is considered an important agent of political socialization, as it can teach people certain political beliefs or values. Besides the socializing role, the media also serves as a "watchdog", drawing attention to government corruption or mistakes, which promotes government transparency and accountability. The media can also serve an agenda-setting role. By covering some news stories and not others, the media has the power to shape what people will think or talk about. Similarly, by "framing" a story from a particular perspective, the media often influences both public opinion and influence government leaders.

Media can have an important effect on public opinion in several ways.

Learning Objectives

Explain the different ways that the mass media forms public opinion

- Mass media frame the details of the story.

- Mass media communicate the social desirability of certain ideas.

- Mass media sets the news agenda, which shapes the public's views on what is newsworthy and important.

- Increasing scandal coverage, as well as profit-motivated sensationalist media coverage, has resulted in young people holding more negative, distrustful views of government than previous generations.

- framing: the construction and presentation of a fact or issue "framed" from a particular perspective

- mass media: The mass media are media technologies like broadcast media and print media that are designed to reach a large audience by mass communication.

Mass media effects on public opinion

- Setting the news agenda, which shapes the public's views on what is newsworthy and important

- Framing the details of a story

- Communicating the social desirability of certain kinds of ideas

The formation of public opinion starts with agenda-setting by major media outlets throughout the world. This agenda-setting dictates what is newsworthy and how and when it will be reported. The media agenda is set by a variety of different environmental and network factors that determines which stories will be newsworthy.

Another key component in the formation of public opinion is framing. Framing is when a story or piece of news is portrayed in a particular way and is meant to sway the consumers' attitude one way or the other. Most political issues are heavily framed in order to persuade voters to vote for a particular candidate. For example, if Candidate X once voted on a bill that raised income taxes on the middle class, a framing headline would read "Candidate X Doesn't Care About the Middle Class". This puts Candidate X in a negative frame to the newsreader.

Social desirability is another key component of the formation of public opinion. Social desirability is the idea that people in general will form their opinions based on what they believe is the popular opinion. Based on media agenda setting and media framing, most often a particular opinion gets repeated throughout various news mediums and social networking sites until it creates a false vision where the perceived truth is actually very far away from the actual truth.

Public opinion can be influenced by public relations and political media. Additionally, mass media utilizes a wide variety of advertising techniques to get their message out and change the minds of people. Since the 1950s, television has been the main medium for molding public opinion, though the internet is becoming increasingly important in this realm.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 26 July 2021

Large-scale quantitative evidence of media impact on public opinion toward China

- Junming Huang ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2532-4090 1 ,

- Gavin G. Cook 1 &

- Yu Xie 1 , 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 181 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

18k Accesses

11 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

- Politics and international relations

Do mass media influence people’s opinions of other countries? Using BERT, a deep neural network-based natural language processing model, this study analyzes a large corpus of 267,907 China-related articles published by The New York Times since 1970. The output from The New York Times is then compared to a longitudinal data set constructed from 101 cross-sectional surveys of the American public’s views on China, revealing that the reporting of The New York Times on China in one year explains 54% of the variance in American public opinion on China in the next. This result confirms hypothesized links between media and public opinion and helps shed light on how mass media can influence the public opinion of foreign countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Song lyrics have become simpler and more repetitive over the last five decades

Emilia Parada-Cabaleiro, Maximilian Mayerl, … Eva Zangerle

Alignment of brain embeddings and artificial contextual embeddings in natural language points to common geometric patterns

Ariel Goldstein, Avigail Grinstein-Dabush, … Uri Hasson

Negativity drives online news consumption

Claire E. Robertson, Nicolas Pröllochs, … Stefan Feuerriegel

Introduction

America and China are the world’s two largest economies, and they are currently locked in a tense rivalry. In a democratic system, public opinion shapes and constrains political action. How the American public views China thus affects relations between the two countries. Because few Americans have personally visited China, most Americans form their opinions of China and other foreign lands from media depictions. Our paper aims to explain how Americans form their attitudes on China with a case study of how The New York Times may shape public opinion. Our analysis is not causal, but it is informed by a causal understanding of how public opinion may flow from the media to the citizenry.

Scholars have adopted a number of wide-ranging and even contradictory approaches to explain the relationships between media and the American mind. One school of thought stresses that media exposure shapes public opinion (Baum and Potter, 2008 ; Iyengar and Kinder, 2010 ). Another set of approaches focuses on how the public might lead the media by analyzing how consumer demand shapes reporting. Newspapers may attract readers by biasing coverage of polarizing issues towards the ideological proclivities of their readership (Mullainathan and Shleifer, 2005 ), and with the advent of social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, traditional media are now more responsive to audience demand than ever before (Jacobs and Shapiro, 2011 ). On the other side of this equation, news consumers generally tend to seek out news sources with which they agree (Iyengar et al., 2008 ), and politically active individuals do so more proactively than the average person (Zaller, 1992 ).

Two other approaches address factors outside the media–public binary. The first, stresses the role of elites in opinion formation. While some, famously including Noam Chomsky, argue that news media are unwitting at best and at worst complicit “shills” of the American political establishment, political elites may affect public opinion directly by communicating with the public (Baum and Potter, 2008 ). Foreign elites may also influence American opinion because American reporters sometimes circumvent domestic sources and ask trusted foreign experts and officials for opinions (Hayes and Guardino, 2011 ). The second stresses how the macro-level phenomenon of public sentiment is shaped by micro-level and meso-level processes. An adult’s opinions on various topics emerge from their personal values, many of which are set during and around adolescence from factors outside of the realm of individual control (Hatemi and McDermott, 2016 ). Social networks may also affect attitude formation (Kertzer and Zeitzoff, 2017 ).

In light of these contradictory interpretations, it is difficult to be sure whether the media shape the attitudes of consumers or, on the other hand, whether consumers shape media (Baum and Potter, 2008 ). Moreover, most of the theories summarized above are tested on relatively small slices of data. In order to offer an alternative, “big data”-based contribution to this ongoing debate, this study compares how the public views China and how the news media report on China with large-scale data. Our data set, which straddles 50 years of newspaper reporting and survey data, is uniquely large and includes more than a quarter-million articles from The New York Times.

Most extant survey data indicate that Americans do not seem to like China very much (Xie and Jin, 2021 ). Many Americans are reported to harbor doubts about China’s record on human rights (Aldrich et al., 2015 ; Cao and Xu, 2015 ) and are anxious about China’s burgeoning economic, military, and strategic power (Gries and Crowson, 2010 ; Yang and Liu, 2012 ). They also think that the Chinese political system fails to serve the needs of the Chinese people (Aldrich et al., 2015 ). Most Americans, however, recognize a difference between the Chinese state, the Chinese people, and Chinese culture, and they view the latter two more favorably (Gries and Crowson, 2010 ). In Fiske’s Stereotype Content Model (Fiske et al., 2002 ), which expresses common stereotypes as a combination of “competence” and “warmth”, Asians belong to a set of “high-status, competitive out-groups” and rank high in competence but low in warmth (Lin et al., 2005 ).

The New York Times, which calls itself the “Newspaper of Record”, is the most influential newspaper in the USA and possibly even in the Anglophonic world. It boasts 7.5 million subscribers (Business Wire, 2021 ), and while the paper’s reach may be impressive, it is yet more significant that the readership of The New York Times represents an elite subset of the American public. Print subscribers to The New York Times have a median household income of $191,000, three times the median income of US households writ large (Rothbaum and Edwards, 2019 ). Despite the paper’s haughty and sometimes condescending reporting, it “has had and still has immense social, political, and economic influence on American and the world” (Schwarz, 2012 , p. 81). The New York Times may be a paper for America’s elite, and it may be biased to reflect the tastes of its elite audience, but the paper’s ideological slant does not affect our analyses as long as the its relevant biases are consistent over the time period covered by our analyses. Our analyses support the intuition of qualitative work on The Times (Schwarz, 2012 ) and show that these biases remain more or less constant for the decades in our sample. These analyses also illuminate some of the paper’s more notable biases, including the paper’s particular predilection for globalization.

The impact of social media on traditional media is not straightforward. While new media have certainly changed old media, neither has replaced the other. It is more accurate to say that old media have been integrated into new media and, in some ways, become a form of new media themselves. Twitter has accelerated the 2000s-era trends of information access that made it possible for news readers to find their own news and also enabled readers to interact with journalists (Jacobs and Shapiro, 2011 ), and the The New York Times seems to have made a significant commitment to the Twitter ecosystem. A quick glance at the follower count of The Times’ official Twitter account shows that it is one of the most influential accounts on the site, with almost 50 million followers. For comparison, both current president Joe Biden and vice president Kamala Harris have around 10 million followers. Most New York Times reporters additionally have “verified” accounts on the platform, which means that individual reporters may be incentivized to maintain public-facing profiles more now than in the past.

The media consumption patterns that made new media possible have changed the way The New York Times interacts with its audience and how it extracts revenue. The New York Times boasts a grand total of 7.5 million subscribers, but only 800,000 of them subscribe to the print edition. The Times’ digital subscription base has boomed since the election of Donald J. Trump, growing almost sixfold from a paltry 1.3 million in 2015 to a staggering 6.7 million in 2020 (Business Wire, 2021 ). The Times increasingly relies more on digital subscriptions and less on print subscriptions and ad sales for revenue (Lee, 2020 ). Ad revenue for most papers has been in sharp decline since the early 2000s (Jacobs and Shapiro, 2011 ), and this trend has only continued into the present. The New York Times now operates almost like a direct-to-consumer, subscription tech startup. New media have not replaced but have certainly changed old media. The full impact of these changes is beyond the scope of this paper, and we suggest it as an area for further research.

A small body of prior work has studied the The New York Times and how The New York Times reports on China. Blood and Phillips use autoregression methods on time series data to predict public opinion (Blood and Phillips, 1995 ). Wu et al. use a similar autoregression technique and find that public sentiment regarding the economy predicts economic performance and that people pay more attention to economic news during recessions (Wu et al., 2002 ). Peng finds that coverage of China in the paper has been consistently negative but increasingly frequent as China became an economic powerhouse (Peng, 2004 ). There is very little other scholarship that applies language processing methods to large corpora of articles from The New York Times or other leading papers. Atalay et al. is an exception that uses statistical techniques for parsing natural languages to analyze a corpus of newspaper articles from The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, and other leading papers in order to investigate the increasing use of information technologies in newspaper classifieds (Atalay et al., 2018 ).

We explore the impact of The New York Times on its readers by examining the general relationship between The Times and public opinion. Though some might contend that only elites read NYT, we have adopted this research strategy for two reasons. If the views of NYT only impacted the nation’s elite, the paper’s views would still propagate to the general public through the elites themselves because elites can affect public opinion outside of media channels (Baum and Potter, 2008 ). Additionally, it is a widely held belief that NYT serves as a general barometer of an agenda-setting agent for American culture (Schwarz, 2012 ). Because of these two reasons, we interpolate the relationship between NYT and public opinion from the relationship between NYT and its readers, and we extrapolate that the views of NYT are broadly representative of American media.

Our paper aims to advance understanding of how Americans form their attitudes on China with a case study of how The New York Times may shape public opinion. We hypothesize that media coverage of foreign nations affects how Americans view the rest of the world. This reduced-form model deliberately simplifies the interactions between audience and media and sidesteps many active debates in political psychology and political communication. Analyzing a corpus of 267,907 articles on China from The New York Times, we quantify media sentiment with BERT, a state-of-the-art natural language processing model with deep neural networks, and segment sentiment into eight domain topics. We then use conventional statistical methods to link media sentiment to a longitudinal data set constructed from 101 cross-sectional surveys of the American public’s views on China. We find strong correlations between how The New York Times reports on China in one year and the views of the public on China in the next. The correlations agree with our hypothesis and imply a strong connection between media sentiment and public opinion.

We quantify media sentiment with a natural language model on a large-scale corpus of 267,907 articles on China from The New York Times published between 1970 and 2019. To explore sentiment from this corpus in greater detail, we map every article to a sentiment category (positive, negative, or neutral) in eight topics: ideology, government and administration, democracy, economic development, marketization, welfare and well-being, globalization, and culture.

We do this with a three-stage modeling procedure. First, two human coders annotate 873 randomly selected articles with a total of 18,598 paragraphs expressing either positive, negative, or neutral sentiment in each topic. We treat irrelevant articles as neutral sentiments. Secondly, we fine-tune a natural language processing model Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT) (Devlin et al., 2018 ) with the human-coded labels. The model uses a deep neural network with 12 layers. It accepts paragraphs (i.e., word sequences of no more than 128 words) as input and outputs a probability for each category. We end up with two binary classifiers for each topic for a grand total of 16 classifiers: an assignment classifier that determines whether a paragraph expresses sentiment in a given topic domain and a sentiment classifier that then distinguishes positive and negative sentiments in a paragraph classified as belonging to a given topic domain. Thirdly, we run the 16 trained classifiers on each paragraph in our corpus and assign category probabilities to every paragraph. We then use the probabilities of all the paragraphs in an article to determine the article’s overall sentiment category (i.e., positive, negative, or neutral) in every topic.

As demonstrated in Table 1 , the two classifiers are accurate at both the paragraph and article levels. The assignment classifier and the sentiment classifier reach classification accuracy of 89–96% and 73–90%, respectively, on paragraphs. The combined outcome of the classifiers, namely article sentiment, is accurate to 62–91% across the eight topics. For comparison, a random guess would reach an accuracy of 50% on each task (see Supplementary Information for details).

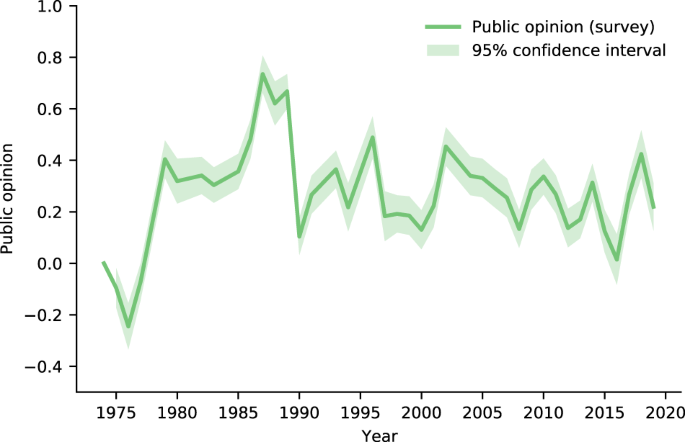

American public opinion towards China is a composite measure drawn from national surveys that ask respondents for their opinions on China. We collect 101 cross-sectional surveys from 1974 to 2019 that asked relevant questions about attitudes toward China and incorporate a probabilistic model to harmonize different survey series with different scales (e.g., 4 levels, 10 levels) into a single time series, capitalizing on “seaming” years in which different survey series overlapped (Wang et al., 2021 ). For every year, there is a single real value representing American sentiment on China relative to the level in 1974. Put another way, we use sentiment in 1974 as a baseline measure to normalize the rest of the time series. A positive value shows a more favorable attitude than that in 1974, and a negative value represents a less favorable attitude than that in 1974. Because of this, the trends in sentiment changes year-over-year are of interest, but the absolute values of sentiment in a given year are not. As shown in Fig. 1 , public opinion towards China has varied greatly from 1974 to 2019. It steadily climbed from a low of −24% in 1976 to a high of 73% in 1987, and has fluctuated between 10% and 48% in the intervening 30 years.

This time series is aggregated from 101 cross-sectional surveys from 1974 to 2019 that asked relevant questions about attitudes toward China with the year of 1974 as baseline. Years with attitudes above zero show a more favorable attitude than that in 1974, with a peak of 73% in 1987. Years with attitudes below zero show a less favorable attitude than that in 1974, with the lowest level of −24% in 1976. The time series is shown with a 95% confidence interval.

We begin with a demonstration of how the reporting of The New York Times on China changes over time, and we follow this with an analysis of how coverage of China might influence public opinion toward China.

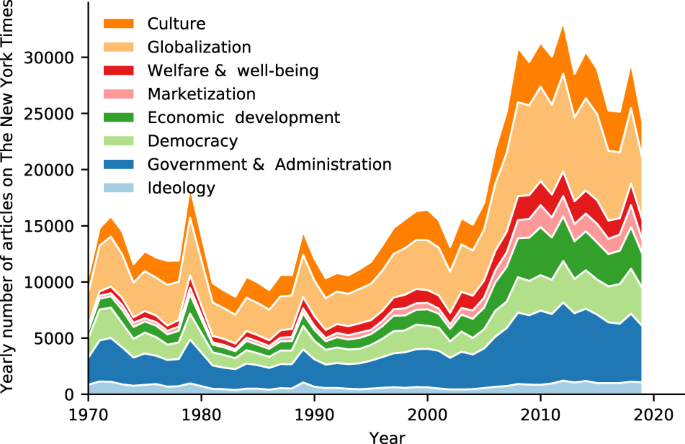

Trend of media sentiment

The New York Times has maintained a steady interest in China over the years and has published at least 3,000 articles on China in every year of our corpus. Figure 2 displays the yearly volume of China-related articles from The New York Times on each of the eight topics since 1970. Articles on China increased sharply after 2000 and eventually reached a peak around 2010, almost doubling their volume from the 1970s. As the number of articles on China increased, the amount of attention paid to each of the eight topics diverged. Articles on government, democracy, globalization, and culture were consistently common while articles on ideology were consistently rare. In contrast, articles on China’s economy, marketization, and welfare were rare before 1990 but became increasingly common after 2000. The timing of this uptick coincided neatly with worldwide recognition of China’s precipitous economic ascent and specifically the beginnings of China’s talks to join the World Trade Organization.

In each year we report in each topic the number of positive and negative articles while ignoring neutral/irrelevant articles. The media have consistently high attention on reporting China government & administration, democracy, globalization, and culture. There are emerging interests on China’s economics, marketization, and welfare and well-being since 1990s. Note that the sum of the stacks does not equal to the total volume of articles about China, because each article may express sentiment in none or multiple topics.

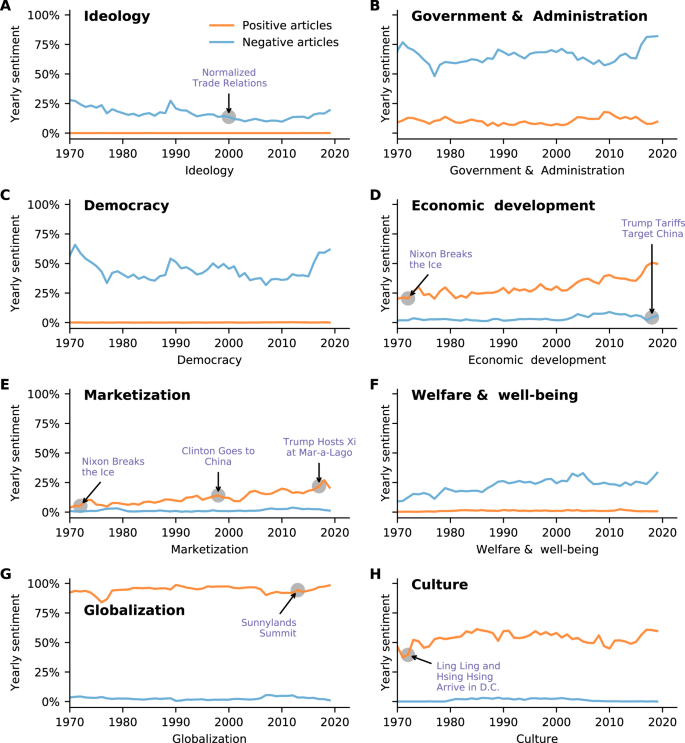

While the proportion of articles in each given topic change over time, the sentiment of articles in each topic is remarkably consistent. Ignoring neutral articles, Figure 3 illustrates the yearly fractions of positive and negative articles about each of the eight topics. We find four topics (economics, globalization, culture, and marketization) are almost always covered positively while reporting on the other four topics (ideology, government & administration, democracy, and welfare & well-being) is overwhelmingly negative.

The panel reports the trend of yearly media attitude toward China in ( A ) ideology, ( B ) government & administration, ( C ) democracy, ( D ) economic development, ( E ) marketization, ( F ) welfare & well-being, ( G ) globalization, and ( H ) culture. The media attitude is measured as the percentages of positive articles and negative articles, respectively. US–China relation milestones are marked as gray dots. The New York Times express diverging but consistent attitudes in the eight domains, with negative articles consistently common in ideology, government, democracy, and welfare, and positive sentiments common in economic, globalization, and culture. Standard errors are too small to be visible (below 1.55% in all topics all years).

The NYT views China’s globalization in a very positive light. Almost 100% of the articles mentioning this topic are positive for all of the years in our sample. This reveals that The New York Times welcomes China’s openness to the world and, more broadly, may be particularly partial to globalization in general.

Similarly, economics, marketization, and culture are covered most commonly in positive tones that have only grown more glowing over time. Positive articles on these topics began in the 1970s with China–US Ping–Pong diplomacy, and eventually comprise 1/4 to 1/2 of articles on these three topics, the remainder of which are mostly neutral articles. This agrees with the intuition that most Americans like Chinese culture. The New York Times has been deeply enamored with Chinese cultural products ranging from Chinese art to Chinese food since the very beginning of our sample. Following China’s economic reforms, the number of positive articles and the proportion of positive articles relative to negative articles increases for both economics and marketization.

In contrast, welfare and well-being are covered in an almost exclusively negative light. About 1/4 of the articles on this topic are negative, and almost no articles on this topic are positive. Topics regarding politics are covered very negatively. Negative articles on ideology, government and administration, and democracy outnumber positive articles on these topics for all of the years in our sample. Though small fluctuations that coincided with ebbs in US–China relations are observed for those three topics, coverage has only grown more negative over time. Government and administration is the only negatively covered topic that does feature some positive articles. This reflects the qualitative understanding that The New York Times thinks that the Chinese state is an unpleasant but capable actor.

Despite the remarkable diversity of sentiment toward China across the eight topics, sentiment within each of the topics is startlingly consistent over time. This consistency attests to the incredible stability of American stereotypes towards China. If there is any trend to be found here, it is that the main direction of sentiment in each topic, positive or negative, has grown more prevalent since the 1970s. This is to say that reporting on China has become more polarized, which is reflective of broader trends of media polarization (Jacobs and Shapiro, 2011 ; Mullainathan and Shleifer, 2005 ).

Media sentiment affects public opinion

To reveal the connection between media sentiment and public opinion, we run a linear regression model (Eq. ( 1 )) to fit public opinion with media sentiment from current and preceding years.

where μ t denotes public opinion in year t with possible values ranging from −1 to 1. F k j s is the fraction of positive ( s = positive) or negative ( s = negative) articles on topic k in year j . Coefficient β k j s quantifies the importance of F k j s in predicting μ t .

There is inertia to public opinion. A broadly held opinion is hard to change in the short term, and it may require a while for media sentiment to affect how the public views a given issue. For this reason, j is allowed to take [ t , t − 1, t − 2, ...] anywhere from zero to a couple of years ahead of t . In other words, we inspect lagged values of media sentiment as candidate predictors for public attitudes towards China.

We seek an optimal solution of media sentiment predictors to explain the largest fraction of variance ( r 2 ) of public opinion. To reduce the risk of overfitting, we first constrain the coefficients to be non-negative after reverse-coding negative sentiment variables, which means we assume that positive articles have either no impact or positive impact and that negative articles have either zero or negative impact on public opinion. Secondly, we require that the solution be sparse and contain no more than one non-zero coefficient in each topic:

where r 2 ( μ , β , F ) is the explained variance of μ fitted with ( β , F ). The l 0 -norm ∥ β k , ⋅ , ⋅ ∥ 0 gives the number of non-zero coefficients of topic k predictors.

The solution varies with the number of topics included in the fitting model. As shown in Table 2 , if we allow fitting with only one topic, we find that sentiment on Chinese culture has the most explanatory power, accounting for 31.2% of the variance in public opinion. We run a greedy strategy to add additional topics that yield the greatest increase in explanatory power, resulting in eight nested models (Table 2 ). The explanatory power of our models increases monotonically with the number of allowed topics but reaches a saturation point at which the marginal increase in variance explained per topics decreases after only two topics are introduced (see Table 2 ). To strike a balance between simplicity and explanatory power, we use the top two predictors, which are the positive sentiment of culture and the negative sentiment of democracy in the previous year, to build a linear predictor of public opinion that can be written as

where F culture, t −1,positive is the yearly fraction of positive articles on Chinese culture in year t − 1 and F democracy, t −1,negative is the yearly fraction of negative articles on Chinese democracy in year t − 1. This formula explains 53.9% of the variance of public opinion in the time series. For example, in 1993 53.9% of the articles on culture had a positive sentiment, and 46.9% of the articles on democracy had negative sentiment ( F c u l t u r e ,1993,positive = 0.539, F democracy,1993,negative = −0.469). Substituting those numbers into Eq. ( 2 ) predicts public opinion in the next year (1994) to be 0.208, very close to the actual level of public opinion (0.218) (Fig. 4 ).

The public opinion (solid), as a time series, is well fitted by the media sentiments on two selected topics, namely “Culture” and “Democracy”, in the previous year. The dashed line shows a linear prediction based on the fractions of positive articles on “Culture” and negative articles on “Democracy” in the previous year. The public opinion is shown with a 95% confidence interval, and the fitted line is shown with one standard error.

By analyzing a corpus of 267,907 articles from The New York Times with BERT, a state-of-the-art natural language processing model, we identify major shifts in media sentiment towards China across eight topic domains over 50 years and find that media sentiment leads public opinion. Our results show that the reporting of The New York Times on culture and democracy in one year explains 53.9% of the variation in public opinion on China in the next. The conclusion that we draw from our results is that media sentiment on China predicts public opinion on China. Our analysis is neither conclusive nor causal, but it is suggestive. Our results are best interpreted as a “reduced-form” description of the overall relationship between media sentiment and public opinion towards China.

While there are a number of potential factors that may complicate our conclusions, none would change the overall thrust of our results. We do not consider how the micro-level or meso-level intermediary processes through which opinion from elite media percolates to the masses below may affect our results. We also do not consider the potential ramifications of elites communing directly with the public, of major events in US–China relations causing short-term shifts in reporting, or of social media creating new channels for the diffusion of opinion. Finally, The New York Times might have a particular bias to how it covers China.

In addition to those specified above, a number of possible extensions of our work remain ripe targets for further research. Though a fully causal model of our text analysis pipeline may prove elusive (Egami et al., 2018 ), future work may use randomized vignettes to further our understanding of the causal effects of media exposure on attitudes towards China. Secondly, our modeling framework is deliberately simplified. The state affects news coverage before the news ever makes its way to the citizenry. It is plausible that multiple state-level actors may bypass the media and alter public opinion directly and to different ends. For example, the actions and opinions of individual high-profile US politicians may attenuate or exaggerate the impact of state-level tension on public sentiment toward China. There are presumably a whole host of intermediary processes through which opinion from elite media affects the sentiment of the masses. Thirdly, the relationship between the sentiment of The New York Times and public opinion may be very different for hot-button social issues of first-line importance in the American culture wars. In our corpus, The New York Times has covered globalization almost entirely positively, but the 2016 election of President Donald J. Trump suggests that many Americans do not share the zeal of The Times for international commerce. We also plan to extend our measure of media sentiment to include text from other newspapers. The Guardian, a similarly elite, Anglophonic, and left-leaning paper, will make for a useful comparison case. Finally, our analysis was launched in the midst of heightened tensions between the US and China and concluded right before the outbreak of a global pandemic. Many things have changed since COVID-19. Returning to our analysis with an additional year or two of data will almost certainly provide new results of additional interest.

Future work will address some of these additional paths, but none of these elements affects the basic conclusion of this work. We find that reporting on China in one year predicts public opinion in the next. This is true for more than fifty years in our sample, and while knowledge of, for example, the opinion diffusion process on social media may add detail to this relationship, the basic flow of opinion from media to the public will not change. Regarding the putative biases of The New York Times, its ideological slant does not affect our explanation of trends in public opinion of China as long as the paper’s relevant biases are relatively consistent over the time period covered by our analyses.

Data availability

All data analyzed during the current study are publicly available. The New York Times data were accessed using official online APIs ( https://developer.nytimes.com/ ). We used their query API to search for 267,907 articles that mention China, Chinese, Beijing, Peking, or Shanghai. We downloaded the full text and date of each article. The survey data were obtained from three large public archives/centers, namely Roper Center for Public Opinion Research (ROPER), NORC at the University of Chicago, and Pew Research Center (Pew Research Center, 2019 ; Smith et al., 2018 ). See Supplementary Information for a full list of surveys. The source codes and pretrained parameters of the natural language processing model BERT are publicly released by Google Inc. on its github repository ( https://github.com/google-research/bert ). The finetuned BERT models and the inferred sentiment of The New York Times articles in our corpus are publicly available at Princeton University DataSpace. Please check the project webpage ( http://www.attitudetowardchina.com/media-opinion ) or the DataSpace webpage ( https://doi.org/10.34770/x27d-0545 ) to download.

Aldrich J, Lu J, Kang L (2015) How do Americans view the rising China. J Contemp China 24(92):203–221

Article Google Scholar

Atalay E, Phongthiengtham P, Sotelo S, Tannenbaum D (2018) New technologies and the labor market. J Monet Econ 97:48–67

Baum MA, Potter PB (2008) The relationships between mass media, public opinion, and foreign policy: toward a theoretical synthesis. Annu Rev Polit Sci 11(1):39–65

Blood DJ, Phillips PC (1995) Recession headline news, consumer sentiment, the state of the economy and presidential popularity: a time series analysis 1989–1993. Int J Public Opinion Res 7(1):2–22

Business Wire (2021) The New York Times company reports 2020 fourth-quarter and full-year results and announces dividend increase. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20210204005599/en/

Cao Y, Xu J (2015) The Tibet problem in the milieu of a rising China: findings from a survey on Americans’ attitudes toward China. J Contemp China 24(92):240–259

Devlin J, Chang MW, Lee K, Toutanova K (2018) BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/181004805

Egami N, Fong CJ, Grimmer J, Roberts ME, Stewart BM (2018) How to make causal inferences using texts. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/180202163

Fiske ST, Cuddy AJ, Glick P, Xu J (2002) A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. J Personal Soc Psychol 82(6):878

Gries PH, Crowson HM (2010) Political orientation, party affiliation, and American attitudes towards China. J Chin Political Sci 15(3):219–244

Hatemi PK, McDermott R (2016) Give me attitudes. Annu Rev Political Sci 19:331–350

Hayes D, Guardino M (2011) The influence of foreign voices on US public opinion. Am J Political Sci 55(4):831–851

Iyengar S, Hahn KS, Krosnick JA, Walker J (2008) Selective exposure to campaign communication: the role of anticipated agreement and issue public membership. J Politics 70(1):186–200

Iyengar S, Kinder DR (2010) News that matters: television and American opinion, Chicago studies in American politics, updated edn. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Book Google Scholar

Jacobs L, Shapiro RY (eds) (2011) Informational interdependence: public opinion and the media in the new communications era. In: The Oxford handbook of American public opinion and the media. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kertzer JD, Zeitzoff T (2017) A bottom-up theory of public opinion about foreign policy. Am J Political Sci 61(3):543–558

Lee E (2020) New York Times hits 7 million subscribers as digital revenue rises. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/05/business/media/new-york-times-q3-2020-earnings-nyt.html

Lin MH, Kwan VS, Cheung A, Fiske ST (2005) Stereotype content model explains prejudice for an envied outgroup: scale of anti-Asian American stereotypes. Personal Soc Psychol Bull 31(1):34–47

Article CAS Google Scholar

Mullainathan S, Shleifer A (2005) The market for news. Am Econ Rev 95(4):1031–1053

Peng Z (2004) Representation of China: an across time analysis of coverage in the New York Times and Los Angeles Times . Asian J Commun 14(1):53–67

Article ADS Google Scholar

Pew Research Center (2019) Global attitudes & trends. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/