Essays About Empathy: Top 5 Examples Plus Prompts

If you’re writing essays about empathy, check out our essay examples and prompts to get started.

Empathy is the ability to understand and share other people’s emotions. It is the very notion which To Kill a Mockingbird character Atticus Finch was driving at when he advised his daughter Scout to “climb inside [other people’s] skin and walk around in it.”

Being able to feel the joy and sorrow of others and see the world from their perspective are extraordinary human capabilities that shape our social landscape. But beyond its effect on personal and professional relationships, empathy motivates kind actions that can trickle positive change across society.

If you are writing an article about empathy, here are five insightful essay examples to inspire you:

1. Do Art and Literature Cultivate Empathy? by Nick Haslam

2. empathy: overrated by spencer kornhaber, 3. in our pandemic era, why we must teach our children compassion by rebecca roland, 4. why empathy is a must-have business strategy by belinda parmar, 5. the evolution of empathy by frans de waal, 1. teaching empathy in the classroom., 2. how can companies nurture empathy in the workplace, 3. how can we develop empathy, 4. how do you know if someone is empathetic, 5. does empathy spark helpful behavior , 6. empathy vs. sympathy., 7. empathy as a winning strategy in sports. , 8. is there a decline in human empathy, 9. is digital media affecting human empathy, 10. your personal story of empathy..

“Exposure to literature and the sorts of movies that do not involve car chases might nurture our capacity to get inside the skins of other people. Alternatively, people who already have well-developed empathic abilities might simply find the arts more engaging…”

Haslam, a psychology professor, laid down several studies to present his thoughts and analysis on the connection between empathy and art. While one study has shown that literary fiction can help develop empathy, there’s still lacking evidence to show that more exposure to art and literature can help one be more empathetic. You can also check out these essays about character .

“Empathy doesn’t even necessarily make day-to-day life more pleasant, they contend, citing research that shows a person’s empathy level has little or no correlation with kindness or giving to charity.”

This article takes off from a talk of psychology experts on a crusade against empathy. The experts argue that empathy could be “innumerate, parochial, bigoted” as it zooms one to focus on an individual’s emotions and fail to see the larger picture. This problem with empathy can motivate aggression and wars and, as such, must be replaced with a much more innate trait among humans: compassion.

“Showing empathy can be especially hard for kids… Especially in times of stress and upset, they may retreat to focusing more on themselves — as do we adults.”

Roland encourages fellow parents to teach their kids empathy, especially amid the pandemic, where kindness is needed the most. She advises parents to seize everyday opportunities by ensuring “quality conversations” and reinforcing their kids to view situations through other people’s lenses.

“Mental health, stress and burnout are now perceived as responsibilities of the organization. The failure to deploy empathy means less innovation, lower engagement and reduced loyalty, as well as diluting your diversity agenda.”

The spike in anxiety disorders and mental health illnesses brought by the COVID-19 pandemic has given organizations a more considerable responsibility: to listen to employees’ needs sincerely. Parmar underscores how crucial it is for a leader to take empathy as a fundamental business strategy and provides tips on how businesses can adjust to the new norm.

“The evolution of empathy runs from shared emotions and intentions between individuals to a greater self/other distinction—that is, an “unblurring” of the lines between individuals.”

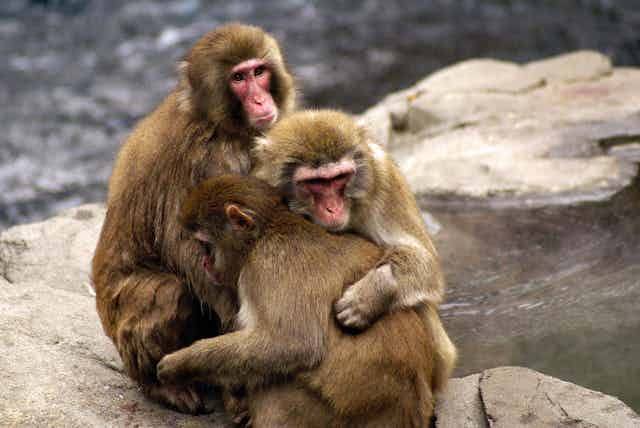

The author traces the evolutionary roots of empathy back to our primate heritage — ultimately stemming from the parental instinct common to mammals. Ultimately, the author encourages readers to conquer “tribal differences” and continue turning to their emotions and empathy when making moral decisions.

10 Interesting Writing prompts on Essays About Empathy

Check out below our list of exciting prompts to help you buckle down to your writing:

This essay discuss teaching empathy in the classroom. Is this an essential skill that we should learn in school? Research how schools cultivate children’s innate empathy and compassion. Then, based on these schools’ experiences, provide tips on how other schools can follow suit.

An empathetic leader is said to help boost positive communication with employees, retain indispensable talent and create positive long-term outcomes. This is an interesting topic to research, and there are plenty of studies on this topic online with data that you can use in your essay. So, pick these best practices to promote workplace empathy and discuss their effectiveness.

Write down a list of deeds and activities people can take as their first steps to developing empathy. These activities can range from volunteering in their communities to reaching out to a friend in need simply. Then, explain how each of these acts can foster empathy and kindness.

Based on studies, list the most common traits, preferences, and behaviour of an empathetic person. For example, one study has shown that empathetic people prefer non-violent movies. Expound on this list with the support of existing studies. You can support or challenge these findings in this essay for a compelling argumentative essay. Make sure to conduct your research and cite all the sources used.

Empathy is a buzzword closely associated with being kind and helpful. However, many experts in recent years have been opining that it takes more than empathy to propel an act of kindness and that misplaced empathy can even lead to apathy. Gather what psychologists and emotional experts have been saying on this debate and input your analysis.

Empathy and sympathy have been used synonymously, even as these words differ in meaning. Enlighten your readers on the differences and provide situations that clearly show the contrast between empathy and sympathy. You may also add your take on which trait is better to cultivate.

Empathy has been deemed vital in building cooperation. A member who empathizes with the team can be better in tune with the team’s goals, cooperate effectively and help drive success. You may research how athletic teams foster a culture of empathy beyond the sports fields. Write about how coaches are integrating empathy into their coaching strategy.

Several studies have warned that empathy has been on a downward trend over the years. Dive deep into studies that investigate this decline. Summarize each and find common points. Then, cite the significant causes and recommendations in this study. You can also provide insights on whether this should cause alarm and how societies should address the problem.

There is a broad sentiment that social media has been driving people to live in a bubble and be less empathetic — more narcissistic. However, some point out that intensifying competition and increasing economic pressures are more to blame for reducing our empathetic feelings. Research and write about what experts have to say and provide a personal touch by adding your experience.

Acts of kindness abound every day. But sometimes, we fail to capture or take them for granted. Write about your unforgettable encounters with empathetic people. Then, create a storytelling essay to convey your personal view on empathy. This activity can help you appreciate better the little good things in life.

Check out our general resource of essay writing topics and stimulate your creative mind!

See our round-up of the best essay checkers to ensure your writing is error-free.

Yna Lim is a communications specialist currently focused on policy advocacy. In her eight years of writing, she has been exposed to a variety of topics, including cryptocurrency, web hosting, agriculture, marketing, intellectual property, data privacy and international trade. A former journalist in one of the top business papers in the Philippines, Yna is currently pursuing her master's degree in economics and business.

View all posts

Home — Essay Samples — Life — Emotions & Feelings — Empathy

Empathy Essays

Hook examples for empathy essays, anecdotal hook.

"As I witnessed a stranger's act of kindness towards a struggling neighbor, I couldn't help but reflect on the profound impact of empathy—the ability to connect with others on a deeply human level."

Rhetorical Question Hook

"What does it mean to truly understand and share in the feelings of another person? The concept of empathy prompts us to explore the complexities of human connection."

Startling Statistic Hook

"Studies show that empathy plays a crucial role in building strong relationships, fostering teamwork, and reducing conflicts. How does empathy contribute to personal and societal well-being?"

"'Empathy is seeing with the eyes of another, listening with the ears of another, and feeling with the heart of another.' This profound quote encapsulates the essence of empathy and its significance in human interactions."

Historical Hook

"From ancient philosophies to modern psychology, empathy has been a recurring theme in human thought. Exploring the historical roots of empathy provides deeper insights into its importance."

Narrative Hook

"Join me on a journey through personal stories of empathy, where individuals bridge cultural, social, and emotional divides. This narrative captures the essence of empathy in action."

Psychological Impact Hook

"How does empathy impact mental health, emotional well-being, and interpersonal relationships? Analyzing the psychological aspects of empathy adds depth to our understanding."

Social Empathy Hook

"In a world marked by diversity and societal challenges, empathy plays a crucial role in promoting understanding and social cohesion. Delving into the role of empathy in society offers important insights."

Empathy in Literature and Arts Hook

"How has empathy been depicted in literature, art, and media throughout history? Exploring its representation in the creative arts reveals its enduring significance in culture."

Teaching Empathy Hook

"What are effective ways to teach empathy to individuals of all ages? Examining strategies for nurturing empathy offers valuable insights for education and personal growth."

"To Kill a Mockingbird": Empathy Quotes

Humility and values, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Characteristics of Being a Counselor

How empathy and understanding others is important for our society, the key components of empathy, importance of the empathy in my family, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Importance of Promoting Empathy in Children

Steps for developing empathy in social situations, the impacts of digital media on empathy, the contributions of technology to the decline of human empathy, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Role of Empathy in Justice System

Importance of empathy for blind people, the most effective method to tune in with empathy in the classroom, thr way acts of kindness can change our lives, the power of compassion and its main aspects, compassion and empathy in teaching, acts of kindness: importance of being kind, the concept of empathy in "do androids dream of electric sheep", the vital values that comprise the definition of hero, critical analysis of kwame anthony appiah’s theory of conversation, development of protagonist in philip k. novel "do androids dream of electric sheep", talking about compassion in 100 words, barbara lazear aschers on compassion, my purpose in life is to help others: helping behavior, adolescence stage experience: perspective taking and empathy, random act of kindness, helping others in need: importance of prioritizing yourself, toni cade bambara the lesson summary, making a positive impact on others: the power of influence, patch adams reflection paper.

Empathy is the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another's position.

Types of empathy include cognitive empathy, emotional (or affective) empathy, somatic empathy, and spiritual empathy.

Empathy-based socialization differs from inhibition of egoistic impulses through shaping, modeling, and internalized guilt. Empathetic feelings might enable individuals to develop more satisfactory interpersonal relations, especially in the long-term. Empathy-induced altruism can improve attitudes toward stigmatized groups, and to improve racial attitudes, and actions toward people with AIDS, the homeless, and convicts. It also increases cooperation in competitive situations.

Empathetic people are quick to help others. Painkillers reduce one’s capacity for empathy. Anxiety levels influence empathy. Meditation and reading may heighten empathy.

Relevant topics

- Forgiveness

- Responsibility

- Winter Break

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Understanding others’ feelings: what is empathy and why do we need it?

Senior Lecturer in Social Neuroscience, Monash University

Disclosure statement

Pascal Molenberghs receives funding from the Australian Research Council (ARC Discovery Early Career Research Award: DE130100120) and Heart Foundation (Heart Foundation Future Leader Fellowship: 1000458).

Monash University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

This is the introductory essay in our series on understanding others’ feelings. In it we will examine empathy, including what it is, whether our doctors need more of it, and when too much may not be a good thing.

Empathy is the ability to share and understand the emotions of others. It is a construct of multiple components, each of which is associated with its own brain network . There are three ways of looking at empathy.

First there is affective empathy. This is the ability to share the emotions of others. People who score high on affective empathy are those who, for example, show a strong visceral reaction when watching a scary movie.

They feel scared or feel others’ pain strongly within themselves when seeing others scared or in pain.

Cognitive empathy, on the other hand, is the ability to understand the emotions of others. A good example is the psychologist who understands the emotions of the client in a rational way, but does not necessarily share the emotions of the client in a visceral sense.

Finally, there’s emotional regulation. This refers to the ability to regulate one’s emotions. For example, surgeons need to control their emotions when operating on a patient.

Another way to understand empathy is to distinguish it from other related constructs. For example, empathy involves self-awareness , as well as distinction between the self and the other. In that sense it is different from mimicry, or imitation.

Many animals might show signs of mimicry or emotional contagion to another animal in pain. But without some level of self-awareness, and distinction between the self and the other, it is not empathy in a strict sense. Empathy is also different from sympathy, which involves feeling concern for the suffering of another person and a desire to help.

That said, empathy is not a unique human experience. It has been observed in many non-human primates and even rats .

People often say psychopaths lack empathy but this is not always the case. In fact, psychopathy is enabled by good cognitive empathic abilities - you need to understand what your victim is feeling when you are torturing them. What psychopaths typically lack is sympathy. They know the other person is suffering but they just don’t care.

Research has also shown those with psychopathic traits are often very good at regulating their emotions .

Why do we need it?

Empathy is important because it helps us understand how others are feeling so we can respond appropriately to the situation. It is typically associated with social behaviour and there is lots of research showing that greater empathy leads to more helping behaviour.

However, this is not always the case. Empathy can also inhibit social actions, or even lead to amoral behaviour . For example, someone who sees a car accident and is overwhelmed by emotions witnessing the victim in severe pain might be less likely to help that person.

Similarly, strong empathetic feelings for members of our own family or our own social or racial group might lead to hate or aggression towards those we perceive as a threat. Think about a mother or father protecting their baby or a nationalist protecting their country.

People who are good at reading others’ emotions, such as manipulators, fortune-tellers or psychics, might also use their excellent empathetic skills for their own benefit by deceiving others.

Interestingly, people with higher psychopathic traits typically show more utilitarian responses in moral dilemmas such as the footbridge problem. In this thought experiment, people have to decide whether to push a person off a bridge to stop a train about to kill five others laying on the track.

The psychopath would more often than not choose to push the person off the bridge. This is following the utilitarian philosophy that holds saving the life of five people by killing one person is a good thing. So one could argue those with psychopathic tendencies are more moral than normal people – who probably wouldn’t push the person off the bridge – as they are less influenced by emotions when making moral decisions.

How is empathy measured?

Empathy is often measured with self-report questionnaires such as the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI) or Questionnaire for Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE).

These typically ask people to indicate how much they agree with statements that measure different types of empathy.

The QCAE, for instance, has statements such as, “It affects me very much when one of my friends is upset”, which is a measure of affective empathy.

Cognitive empathy is determined by the QCAE by putting value on a statement such as, “I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision.”

Using the QCAE, we recently found people who score higher on affective empathy have more grey matter, which is a collection of different types of nerve cells, in an area of the brain called the anterior insula.

This area is often involved in regulating positive and negative emotions by integrating environmental stimulants – such as seeing a car accident - with visceral and automatic bodily sensations.

We also found people who score higher on cognitive empathy had more grey matter in the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex.

This area is typically activated during more cognitive processes, such as Theory of Mind, which is the ability to attribute mental beliefs to yourself and another person. It also involves understanding that others have beliefs, desires, intentions, and perspectives different from one’s own.

Can empathy be selective?

Research shows we typically feel more empathy for members of our own group , such as those from our ethnic group. For example, one study scanned the brains of Chinese and Caucasian participants while they watched videos of members of their own ethnic group in pain. They also observed people from a different ethnic group in pain.

The researchers found that a brain area called the anterior cingulate cortex, which is often active when we see others in pain, was less active when participants saw members of ethnic groups different from their own in pain.

Other studies have found brain areas involved in empathy are less active when watching people in pain who act unfairly . We even see activation in brain areas involved in subjective pleasure , such as the ventral striatum, when watching a rival sport team fail.

Yet, we do not always feel less empathy for those who aren’t members of our own group. In our recent study , students had to give monetary rewards or painful electrical shocks to students from the same or a different university. We scanned their brain responses when this happened.

Brain areas involved in rewarding others were more active when people rewarded members of their own group, but areas involved in harming others were equally active for both groups.

These results correspond to observations in daily life. We generally feel happier if our own group members win something, but we’re unlikely to harm others just because they belong to a different group, culture or race. In general, ingroup bias is more about ingroup love rather than outgroup hate.

Yet in some situations, it could be helpful to feel less empathy for a particular group of people. For example, in war it might be beneficial to feel less empathy for people you are trying to kill, especially if they are also trying to harm you.

To investigate, we conducted another brain imaging study . We asked people to watch videos from a violent video game in which a person was shooting innocent civilians (unjustified violence) or enemy soldiers (justified violence).

While watching the videos, people had to pretend they were killing real people. We found the lateral orbitofrontal cortex, typically active when people harm others, was active when people shot innocent civilians. The more guilt participants felt about shooting civilians, the greater the response in this region.

However, the same area was not activated when people shot the soldier that was trying to kill them.

The results provide insight into how people regulate their emotions. They also show the brain mechanisms typically implicated when harming others become less active when the violence against a particular group is seen as justified.

This might provide future insights into how people become desensitised to violence or why some people feel more or less guilty about harming others.

Our empathetic brain has evolved to be highly adaptive to different types of situations. Having empathy is very useful as it often helps to understand others so we can help or deceive them, but sometimes we need to be able to switch off our empathetic feelings to protect our own lives, and those of others.

Tomorrow’s article will look at whether art can cultivate empathy.

- Theory of mind

- Emotional contagion

- Understanding others' feelings

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Senior Education Technologist

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Reflections on Empathy

- by Mayte Picco-Kline

- on September 1, 2020

The word “empathy” came to me through diverse situations and sparked my enthusiasm to share a few thoughts on the topic in the context of a “Life Lived Forward.”

Empathy is a broad concept that refers to the cognitive and emotional reactions of an individual to the observed, wide range of experiences of another. Emotion researchers generally define empathy as the ability to sense other people’s emotions, coupled with the ability to imagine what someone else might be thinking or feeling. It is usually associated with being able to “put ourselves in another person’s shoes” – understanding the other person’s perspective and appreciation of reality so we can better respond to the situation and the potential to develop compassion and offer a helping hand.

Becoming empathetic requires thinking beyond ourselves and our personal concerns, in the understanding that others concerns and points of view are as valuable as our own. We enhance our ability to do so by opening to the varied ways in which others approach life. Empathy has abundant benefits. It is a key ingredient of successful relationships as it facilitates understanding the perspectives, needs, and intentions of others. It creates a sense of well-being. It reduces stress and fosters resilience. Empathy expands the potential for personal and social growth, and for creative thinking and action.

Communications are impacted by the degree of our empathy. When we understand the feelings of another person in a given situation and understand why their actions make sense to them, we are better equipped to communicate our own ideas in a way that may make sense to them. Enhancing communication requires intent listening without preconceived assumptions. Understanding the individual uniqueness of our personal experience facilitates this process.

Some ways to cultivate empathy involve challenging ourselves, exploring feelings in addition to thoughts, and finding ways to ask questions that are conducive to deeper communication and understanding.

Some affirmations I have found valuable in highlighting the potential for becoming more empathetic include:

- I constantly rejoice in the good that comes to others.

- My heart is receptive to new understanding from every source.

- Everyday I enter every experience with the whole of myself.

- My heart re-echoes peace from every heart.

- I acknowledge the infinity of resource.

By Mayte Picco-Kline

This Post Has 2 Comments

Hello! Do you use Twitter? Id like to follow you if that would be okay. Im undoubtedly enjoying your blog and look forward to new updates.

Several of the points associated with this weblog publish are usually advantageous nonetheless had me personally wanting to understand, did they critically imply that? One stage I have got to say is your writing experience are excellent and Ill be returning back again for any brand-new weblog post you come up with, you may probably have a brand-new supporter. I bookmarked your weblog for reference.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Subscribe via email.

- Enter your email address: *

Font Resizer

A Decrease font size. A Reset font size. A Increase font size.

Author Spotlight

Recent Posts

- The Best Way to Cook Greens

- Is It Time To Own Up To Your Hearing Loss?

- Testing Berries and Nuts, Two of the Best Brain Foods

- Over-the-Counter Hearing Aids: One Audiologist’s Perspective

- Which Diet Works Even Better the Longer You Do It?

Recent Comments

- rama on Four Tips to Practice Good Mental Hygiene During the Coronavirus Outbreak

- rama on The Effect of Avocados on Small, Dense, LDL Cholesterol

- rama on Takeaways from My Webinar on COVID-19

The word “empathy” came to me through diverse situations and sparked my enthusiasm to share a few thoughts on the

Follow Willow Valley Communities

Sponsored by: Willow Valley Communities

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Moral Importance of Reflective Empathy

Ingmar persson.

1 Department of Philosophy, Linguistics, and the Theory of Science, Göteborgs universitet, Gothenburg, Sweden

2 Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, University of Oxford, Suite 8, Littlegate House, 16/17 St Ebbe’s St, Oxford, OX1 1PT UK

Julian Savulescu

This is a reply to Jesse Prinz and Paul Bloom’s skepticism about the moral importance of empathy. It concedes that empathy is spontaneously biased to individuals who are spatio-temporally close, as well as discriminatory in other ways, and incapable of accommodating large numbers of individuals. But it is argued that we could partly correct these shortcomings of empathy by a guidance of reason because empathy for others consists in imagining what they feel, and, importantly, such acts of imagination can be voluntary – and, thus, under the influence of reflection – as well as automatic . Since empathizing with others motivates concern for their welfare, a reflectively justified empathy will lead to a likewise justified altruistic concern. In addition, we argue that such concern supports another central moral attitude, namely a sense of justice or fairness.

What Empathy Is and the Case Against its Moral Importance

It has generally been taken for granted that empathy is important for morality, so it was to be expected that this assumption would eventually be challenged. Paul Bloom’s Against Empathy [ 1 ] is a full-scale challenge; Jesse Prinz makes a similar, smaller scale challenge in Is Empathy Necessary for Morality [ 2 ] and Against Empathy [ 3 ]. We will argue that empathy can have an essential role to play in moral motivation, but then it needs to be harshly disciplined by other factors – in particular, reasoning – to play its role properly.

To begin with, what is empathy? Bloom understands it to be ‘the act of feeling what you believe other people feel – experiencing what they experience’ [ 1 , p.3]. Prinz’ conception is similar: ‘it’s feeling what one takes another person to be feeling’ [ 2 , p.212]. Bloom distinguishes empathy from cognitive empathy [ 1 , p.17], sympathy and pity [ 1 , p.40], and compassion and concern [ 1 , pp.40–1]. For instance, ‘if I understand that you are feeling pain without feeling it myself’ [ 1 , p.17], this is cognitive empathy. Cognitive empathy is ‘morally neutral’ [ 1 , p.38]: people who are morally good share it with ‘successful con men, seducers, and torturers’ [ 1 , p.37]. So, Bloom seems to think – correctly, to our minds – that cognitive empathy is not enough to motivate moral behaviour, whereas empathy in the proper sense – ‘emotional empathy’ – can be. Indeed, what he sees as defects of empathy implies that it is a motivator. He objects that:

it is a spotlight focusing on certain people in the here and now. This makes us care more about them, but it leaves us insensitive to the long-term consequences of our acts and blind as well to the suffering of those we do not or cannot empathize with. Empathy is biased, pushing us in the direction of parochialism and racism. It is shortsighted, motivating actions that might make things better in the short term but lead to tragic results in the future. It is innumerate, favoring the one over the many. It can spark violence; our empathy for those close to us is a powerful force for war and atrocity toward others. [ 1 , p.9].

These critical remarks imply that empathy motivates; Bloom’s point is that empathy often motivates us in ways that are morally objectionable. Thus, ‘empathy is not sufficient to guide moral action’ [ 1 , p.191], but it is not disputed that it is a motivating factor, that it could make us ‘care’ about others.

Empathy, then, is not a reliable guide to moral action because it is directed first and foremost at people (bracketing other sentient beings for present purposes) we know well or who are present before our eyes – those who are ‘spatially near’ – at the expense of those who are strangers to us, or beyond the reach of our senses. With respect to people who are spatially near – including ourselves – it is especially focussed on how they will fare in the more immediate future. That is, its focus is on what is temporally near as well as spatially near. Furthermore, even among people who are present to our senses, some may not easily be the target of our empathy because they are different from us in some conspicuous ways: their skin colour is different, they are deformed, dirty, etc. – that is, empathy is discriminatory. Finally, empathy is ‘innumerate’: we cannot empathize with groups of people in proportion to their number. The larger the group, the more of a drawback this limitation is.

Prinz voices similar objections to empathy: it ‘may lead to preferential treatment’, ‘may be subject to unfortunate biases, including the cuteness effects’, ‘is prone to in-group biases’,‘is subject to proximity effects’, and so on [ 2 , p.226]; cf. [ 3 , pp.227–30]. Yet he adds to the list of accusations that ‘empathy is not very motivating’ [ 2 , p.225]. But this is hard to square with what he says to support his other accusations. As regards preferential treatment, he reports that when subjects had been presented with a vignette about a woman awaiting medical treatment, ‘they overwhelmingly elected to move her up at the expense of those in greater need’ [ 2 , p.226]; cf. [ 3 , p.228] who were anonymous to them. And as regards in-group biases, he refers to some studies that have ‘found that empathy leads to helping only when the person in need is a member of the in-group’ [ 2 , p.226]. But then empathy does after all motivate us to favour or help some. Thus, the more plausible moral objection to empathy is not that it is not motivating, but that it often leads us morally astray because it is motivating.

Bloom does not have that much to say much about the attitudes of sympathy, pity, compassion and concern to which he is more favourably disposed than empathy (as Prinz is to concern, [ 3 , pp.230–1]). He writes that ‘ sympathy and pity are about your reaction to the feelings of others, not the mirroring of them… If you feel bad for someone in pain, that’s sympathy, but if you feel their pain, that’s empathy’ [ 1 , p.40]. We believe the same holds for compassion: it is the emotion of feeling sad or unhappy because you believe that someone else is suffering or is having a hard time. By contrast, we regard being concerned about others, or their welfare, as a desire that things go well for them for their own sake. To be concerned about someone in this sense is to adopt an attitude of benevolence or altruism towards them. If you have the power to see to it that things go well for those towards whom you have adopted this attitude, you need not be put in a position in which it is proper to feel sympathy, pity or compassion for them, that is, to feel bad or sad because things are not going well for them.

Bloom insists that concern and compassion do not require empathy [ 1 , p.41]. This allegedly makes them ‘more diffuse than empathy’; as a result, it is ‘weird to talk about having empathy for the millions of victims of malaria, say, but perfectly normal to say that you are concerned about them or feel compassion for them’ [ 1 , pp.40–1]. Thus, on his view, concern and compassion are not innumerate as is empathy, and exposed to criticism on this score. Due to the fact that compassion, like pity and sympathy, are in place only if the subjects they target are faring badly in some way, we will concentrate on the attitude of benevolent or altruistic concern and ask what motivational role empathy does or could play in relation to this attitude, that is, for a desire that others fare well for their own sake – though we may in fact empathize more frequently with others when in fact they do not fare well. 1

But more needs to be said about what empathy is – or rather what it will here be taken to be. It is not actually feeling what you believe others to be feeling, as Bloom and Prinz would have it. For instance, when you empathize with somebody whom you believe to be feeling physical pain, e.g. because they have hit their thumb with a hammer, you do not feel physical pain; instead, you more or less vividly imagine feeling a pain like the one you believe they are feeling. You imagine what it is like to be them, feeling what they do. Notice that it is not imagining that you yourself are feeling what you believe they are feeling (which is what e.g. Smith usually takes sympathy to involve); it is imagining being them , feeling as they are believed to be feeling. 2 However, it would be too strict to demand that empathizing with someone requires succeeding in imagining feeling something which is quite similar to what this individual is in fact feeling. You may be said to empathize with someone when you imagine feeling as you believe they do, though your belief is only very roughly right. Nonetheless, empathizing requires imagining having the right kind of feeling: for instance, you cannot be said to be empathizing with somebody if you imagine being glad when that individual is in fact sad.

According to this conception of empathy, it is a mistake to talk about feeling empathy, emotional empathy, or empathic feelings , as Bloom and Prinz do. This is a respect in which empathizing with someone’s feelings differs from what is often called emotional contagion : for example, if you are surrounded by sad people, this is likely to make you sad, while if you are met with smiles, this liable to put you in a good mood. In these cases, you are actually feeling the emotions that others are having, not imagining feeling them. Bloom notes that emotional contagion is ‘not quite the same as’ empathy [ 1 , p.40], but he fails to see this salient difference. Prinz’s claim is more explicitly inconsistent with the present understanding of ‘empathy: ‘empathy in its simplest form is just emotional contagion’ [ 2 , p.212].

Anyway, empathizing with somebody, as we conceive it, is imagining feeling how this individual is feeling, especially in ways that are good or bad for him or her. 3 Admittedly, the term ‘empathy’ is often used in other ways, and this accounts for the fact that it may seem odd to say, e.g. that Schadenfreude or malice involves empathy. But to our minds, there are other terms, like ‘sympathy’, which are better suited to designate what is at issue here (or a technical term like ‘emotional empathy’ may be introduced).

Some of Bloom’s arguments against empathy trade on the failure to separate it clearly from emotional contagion. He correctly points out that we might find ourselves sad without realizing that this is the result of the sadness of others having infected us. Then we will not be motivated to do anything to relieve their sadness: ‘Without an appreciation of the source of one’s suffering, the shared feeling is inert’ [ 1 , p.173]. But we cannot intelligibly empathize with someone’s sadness without realizing that the sadness we imagine feeling is the sort of sadness that we believe this individual to be feeling because it is imagining feeling a sort of sadness precisely for the reason that it is the sort we believe this individual to be feeling. Thus, empathy cannot be motivationally inert because it lacks a target in the sense described by Bloom.

At some points, Bloom’s misconception of empathy as comprising actual feelings appears to mislead him to overlook the involvement of empathy in concern. He writes: ‘you see the victim’s face contorted in anguish, but you don’t see anguish in the consolers, just concern’ [ 1 , p.175]. However, in so far as the consolers empathize they do not feel anguish, but imagine feeling it, and it should not be expected that imagined anguish needs to show up in the face in the same fashion as genuine anguish does. If this imagined feeling motivates concern, it is precisely concern that we should expect to see in the face of an empathizer, not anguish.

Spontaneous Empathy and Voluntary, Reflective Empathy

We have seen that cognitive empathy is not sufficient to make us concerned: if we acquire a belief that somebody is suffering on the basis of a verbal report, we might not be the least motivated to relieve the suffering. On the other hand, empathy with sufferers does motivate us to relieve the suffering. It has already been observed that if that were not so, Prinz and Bloom’s case against empathy to the effect that it is a poor guide to moral action, since it is biased and innumerate, would be undercut. So, let us proceed on the plausible assumption that it does motivate. 4

It is true that, as Bloom maintains, we ‘cannot empathize with more than one or two people at the same time’ [ 1 , p.33]; cf. [ 2 , p.229]. It also true that we find it harder to empathize with people who are different from us in conspicuous ways, such as having a different skin colour, or who repel us by being deformed, dirty, etc., and that this is likely to lead to discrimination, or exclusion of individuals from concern on morally unjustifiable grounds. Empathy is also biased towards the near future in the sense that we empathize more readily with the suffering that individuals – ourselves included – will feel in the near than in the more distant future. These are reasons why Bloom – rightly – thinks that ‘empathy is a terrible guide to moral judgment’ [ 1 , p.45].

On the other hand, he admits that ‘it can be strategically used to motivate people to do good things’ [ 1 , p.45]. (In this respect, he appears more conciliatory than Prinz, as will be seen below.) The question then arises whether it is not a better strategy to try to discipline empathy than try to do without it. The latter seems to be what Bloom recommends when he claims that ‘on balance, we are better off without it’ [ 1 , p.39]; similarly, Prinz hopes for ‘the extirpation of empathy’ [ 3 , p.228]. This is primarily where we part company. The risk is that without empathy we would not be concerned with anyone’s well-being, not even our own beyond the present moment. As has been seen, Bloom believes that such concern does not require empathy, but he concedes that cognitive empathy is not sufficient for concern when he writes that people who lack concern can have it, e.g. con men, torturers, and psychopaths. What, then, could fill the slack left by cognitive empathy? Bloom does not seem to answer this question.

His appeal to compassion and concern are unhelpful because they are biased and innumerate just like empathy: we feel more compassion and concern for suffering that is close in time, for people who we know well and who have been friendly towards us, and for single identifiable individuals than for masses of anonymous people. A readily available explanation of this fact is that empathy is the motivational source of these attitudes.

Empathy with someone is capable of motivating because it is imagining what it is like for this individual to have a (positive or negative) sensory or affective experience, and this consists in having an ‘image’ or, better, a sensuous representation of the experience which is similar or isomorphic to the experience and derived from having this kind of experience oneself. Thus, as Bloom notes [ 1 , pp.147–9], in order to be able to empathize adequately with somebody who is feeling pain, say, it is necessary to have felt a similar pain yourself – so, those rare individuals who are congenitally insensitive to pain cannot empathize with those who are exposed to pain. Since having pain motivates you to try to rid yourself of it, it would not be surprising if imagining somebody having the pain that you believe this individual to have could motivate you to try to rid them of it, given that the imagined pain is similar to an actually felt pain. The evolutionary explanation of why we so readily imagine feeling a pain we think we will ourselves suffer if we do not take action is surely that this will motivate us to take action to avoid the pain. Then, provided it could serve our reproductive fitness, we should expect that the same device is put to use in the case of others, so that imagining someone else having a pain could also motivate action to save them from the pain, as both commonsensical experience and experimental evidence indicate. But since the imagined pain is not as vivid or forceful as a felt pain (unless it is hallucinatory), it will not motivate to the same degree (cf. [ 4 , p.764]).

If you had been hooked up to someone else’s nervous system by something functioning like afferent pathways, so you actually felt the pain this individual feels in his or her body, you would be more strongly motivated to eliminate it, probably as strongly motivated as this individual. But then you could not empathize with the pain this individual is feeling for the same reason that you cannot empathize with the pain that you are now feeling in your own body. The reason is that you cannot imagine feeling a pain that you are actually feeling; the actual feeling so to speak overshadows any imagined feeling. It follows from this that Prinz is right when he points out [ 2 , p.214]; [ 3 , p.219] that empathy cannot be necessary for each and every moral attitude that we could adopt, e.g. the indignation that we may feel because of the pain we are now suffering unjustly.

When you attribute the pain you imagine to someone else, it is their pain you will seek to relieve in the first instance. At a pre-linguistic stage, the belief that another is in pain would have to be expressed in a medium of sensuous representation; so there would then be no distinction between so-called cognitive empathy and empathy in our terminology. You would be moved to some extent to relieve the pain you imagine the other to be having. But if you cannot relieve the pain of the other, you may resort to relieving only the pain you imagine and, thereby, the pity you feel. As Bloom mentions [ 1 , pp.74–5], if you empathize with the pain of somebody writhing in front of your eyes, and find that you can do nothing to remove the pain of this individual, you may resort to changing your location so that this individual is no longer within sight. For if you can no longer see this individual, your empathy is liable to subside and, thereby, your desire that the victim’s pain be relieved, alongside the pity and frustration that you will feel because this desire cannot be satisfied.

If the account of empathy given here is correct, is it possible to ‘exploit people’s empathy for good causes’ [ 1 , p.49], by trying to give it better direction? Such a strategy would seem preferable to the strategy of removing empathy that would risk leaving us motivationally dry and unconcerned about the weal and woe of our future selves and others. According to the account given here, we are capable of modifying the direction of empathy because it is not only true that we spontaneously or automatically imagine having sensory experiences we believe that others undergo or that we might undergo in the future; we can also do this voluntarily or at will . 5

To take a simple case involving only yourself: if you are told that you will probably feel acute pain later today, you will immediately be seriously concerned, think desperately about ways of escaping this pain, and feel fear it cannot be avoided. This is because you automatically empathize with yourself later today, i.e. you automatically imagine feeling the pain you believe that you might feel shortly. 6 By contrast, your automatically imagining the acute pain you hear that you might suffer next year will be much more fleeting and perfunctory, if it occurs at all. But your reason could inform you that your pain next year will one day be just as real and unbearable as your pain later today, and this may induce you to imagine voluntarily feeling next year’s pain if this could help motivate you to find ways of avoiding it. If this imagining is done with some persistence, it will most likely increase your concern about feeling this pain, though it is unlikely to become as great as your concern about the pain later today, since the outcome of your act of voluntary imagination will probably be less vivid or detailed. True, a voluntary act of imagination presupposes that you are motivated to perform it, but the deliverance of your reason along with your automatic empathy, though perfunctory, may be enough to supply this amount of motivation which could inflate itself by means of a voluntary act of imagination.

Thus, we can counteract our bias towards the near future in matters concerning ourselves, though we are unlikely to overcome it completely. More often than we would like, it will continue to make us act in ways that we recognize as weak-willed and irrational. But although it would now often be better for us to be able to rise above this bias, it has probably served us well in the past before the rational powers of our species developed to anything like the present extent because the situations that it is most pressing to deal with are as a rule those in the nearer future.

Similarly, from an evolutionary point of view it is not hard understand why our empathy with others is spontaneously selective. Spontaneously, we empathize with individuals who we know well and with whom we have cooperated advantageously, like our kin and people in our community, and not with strangers who might be treacherous or hostile for all we know. This makes evolutionary sense if benevolent or altruistic concern rides on the back of empathy because then we shall be concerned about people in our own tribe and unconcerned about outsiders, and this is likely to make our own tribe successful in the struggle for resources with these outsiders.

But although we do not spontaneously empathize with some individuals for such reasons and, therefore, have little or no concern for them, our intellect can tell us that some or all of the indicated exclusionary reasons are not sound reasons to think that the suffering of these individuals is morally less bad. Suppose that we are repelled by some people because they are deformed or dirty and therefore do not take time to empathize with their suffering. Then, on reflection, we could realize that these features are not anything for which they are responsible and which makes their suffering morally less important. This gives us reason to make a voluntary effort to imagine vividly the suffering of these individuals, despite their unappealing features. As a result, we will be more concerned about their suffering, though probably not as much concerned as we are about the suffering of those whom we find congenial, and with whom we automatically empathize.

Consequently, by means of our power of reasoning, we can expand the range of our empathy, and thereby our benevolent concern, to other individuals and further into the future, and make these attitudes less discriminatory. We can also extend our empathy to a greater number of people, by voluntarily imagining the suffering of a single, arbitrary individual from a large group and telling ourselves that the suffering of each individual of the group is as real and morally bad as is the suffering of this individual and, thus, that our concern for the sufferings of the entire group should be proportionally greater. This is likely to make our concern for the collective suffering significantly greater than our concern for a single individual’s suffering, though hardly as great as it ideally should be.

In sum, by means of our reason we can counteract the fact that our empathy is spatio-temporally biased, unjustifiably discriminatory, and innumerate, and develop a more reflective empathy, though we would be hard put to overcome completely these shortcomings of our spontaneous empathy. Such a reflective empathy would motivate a correspondingly more reflective and justifiable altruistic concern, as well as greater, more rational prudential concern for our future selves. In other words, we are capable of a sort of motivational bootstrapping: we find ourselves concerned about others because we automatically empathize with them to some degree, and this concern could motivate us to reflect on the unjustifiability of the grounds that tend to eclipse our automatic empathy for these individuals, and modify our concern for them in ways we see as rationally justified by voluntarily imagining more vividly what it is like to be them. By this procedure we could surmount obstacles that evolutionary programming has put in the path of our empathy and benevolent concern. This is clearly a superior strategy to trying to divest ourselves of empathy because it is misdirected or restrictive, and thereby risk divesting ourselves of concern for others.

As already indicated, the point can also be made in terms of prudential concern for our own more distant future. It would be a poor strategy to give up empathizing with our possible suffering in the distant future, say from lung cancer from smoking cigarettes. Rather, we should develop a more reflective empathy which extends further into our future, by heeding our reason’s advice to imagine more distant suffering as vividly as we spontaneously imagine suffering that is closer in time. This strategy is more likely to generate motivation to give up smoking now than refraining from such a voluntary direction of imagination.

Empathy, Justice and Anger

Some grounds for excluding individuals from, or pushing them to the periphery of, empathy and concern are however warranted. Bloom notes that ‘you feel more empathy for someone who treats you fairly than for someone who cheats you’ [ 1 , p.68]. We put this down to our being equipped with a sense of justice or fairness . This sense expresses itself not only in our making judgments about what is (un)just or (un)fair, but also in our being motivated to some extent to rectify what we judge to be unjust or unfair.

Like many other animals, we practice the tit-for-tat strategy which consists in responding in the same coin: being angry at and inclined to punish those who harm us, or those close to us, and being grateful and inclined to reward those who benefit us, or those close to us. From an evolutionary point of view, it is not hard to comprehend why we abide by this strategy. But in contrast to (most) other animals, we have the power to contemplate whether our spontaneous angry or grateful reactions are justifiable. The upshot of this contemplation may be that after all an angry and punitive response would not be just or justifiable because, say, the harm inflicted on us was accidental or unavoidable, or that it was inflicted in order to protect somebody else from much greater harm. So, reason may command us to hold back our spontaneous angry and punitive responses.

We may however fail to comply with this command if we empathize strongly with the victims of the harmful act but not at all with its perpetrator. Indeed, such biased empathy might even get in the way of our making reasonable judgments about what is justifiable. We might be so incensed by the fact that we have been harmed that we overlook that the infliction of the harm was unavoidable or justifiable, just as we might be unable to control our temper and retaliate, though we realize that it is unjustifiable. This is of course less likely to happen if we empathize not only with the victims of a harmful act but also with its agent.

Although Bloom concedes that ‘empathy can serve as the brakes’ on aggression and violence for such reasons, he argues that ‘it’s just as often the gas ’ [ 1 , p.188]: ‘the empathy one feels toward an individual can fuel anger toward those who are cruel to that individual’ [ 1 , p.208]. But it is not empathy with the cruelly treated victim that triggers the aggression toward the offender; it is our adherence to the tit-for-tat strategy that drives us to punish agents who are cruel to those we care about. Certainly, if we empathize with victims – but not with the aggressors – this will amplify our aggression, but it is not empathy, or its absence, that makes us angry at aggressors. If it is claimed that it is such an amplification of anger beyond reason that is what makes empathy undesirable in this connection, it should be retorted that it offers the compensating good of serving as a brake on our anger if we direct it at the aggressors. Surely, this is not what you expect of something that is properly characterized as ‘a powerful force for war and atrocity’ [ 1 , p.9].

In any case, it is doubtful that the removal of empathy is a recommendable remedy (were it feasible). Although our sense of justice by itself motivates us to do what we judge to be just, the risk is that this motivation will be so weak in many of us that we will do little to rectify instances of injustice. For when we attempt to punish offenders, or extract compensation from them, we usually have to stick our necks out, and we are disinclined to do so for people we do not care about. Likewise, we are also likely to incur costs should we reward those who have acted justly. Benefiting people who are unfairly worse off or in greater need than others when this is simply the result of bad luck and not the wrong-doing of any moral agents is of course also costly. A better strategy than removal of empathy would seem to be to involve empathizing with those at the receiving end of unfair acts and misfortunes, but balancing it with a reasonable amount of empathy for possible offenders.

The importance of empathy as a brake on unjustified aggression and violence may be even clearer in the case of psychopaths. Bloom’s conclusion about them is: ‘They do tend to be low in empathy. But there is no evidence that this lack of empathy is responsible for their bad behavior’ [ 1 , p.201]. Here it is important to bear in mind that empathy has a function to fill not only with respect to others, but with respect to our own future as well. Psychopaths are characteristically unconcerned not only about other individuals, but about their own long-term future (and past), too. Hence, their ‘lack of realistic long-term goals’, their ‘impulsivity’ and ‘irresponsibility’ [ 1 , p.198]; their being ‘relatively indifferent to punishment’ and ‘unmoved by love withdrawal’, as mentioned by Prinz [ 1 , p.218]; cf. [ 3 , p.222]. Now suppose – as seems true – that psychopaths are also prone to aggression and excessive vanity. It is obvious that such people could easily be driven to crime and other immoral behaviour to gain short-term profits because neither concern for others nor fear of punishment and social condemnation of themselves will hold them back.

Like the instinctive grounds for excluding people from empathy and altruistic concern, the instinctive grounds for how justice requires people to be treated are then subject to revision in light of reason. These grounds seem partly to overlap. For instance, earlier on in human history the fact that some people were deformed or disabled appears to have been regarded not only as a ground for excluding them from empathy and concern but, even more absurdly, as grounds making it just (deserving, fitting etc.) that they be worse off than others.

Prinz considers the possibility ‘to overcome the selective nature of empathy by devising a way to make us empathize with a broader range of people’ [ 2 , p.228], but rejects it because he thinks that empathy is ‘intrinsically biased’ [ 3 , p.229]. Instead, he favours a ‘less demanding’ alternative which dispenses with empathy. This alternative appeals, in the negative case, only to feelings of disapprobation like anger and guilt, and types of action that evoke them:

If we focus our moral judgments on types of actions (stealing, torture, rape, etc.) and make an effort not to reflect on the specific victims, we may be able to achieve a kind of impartiality… any focus on the victim of a transgression should be avoided, because of a potential bias. [ 2 , p.228]; [ 3 , p.220]

The emotions of disapprobation are more powerful motivators of moral action than empathy, according to him. And ‘anger can be conditioned through imitation. If we express our outrage at injustice, our children will feel outrage at injustice’ [ 2 , p.229]. Sure, but children can be taught to feel outrage at types of actions that many of us would not nowadays regard as morally wrong, such as working on Sundays or consensual homosexual acts between adults. To explain why such acts are not morally wrong while others are, it seems that we would have to refer to the fact that they do not harm or make anyone unjustly worse off, whereas morally wrongful acts do. But then it can be objected, again, that it seems that the realization that some individuals have been unjustly harmed will elicit little, if any, anger or indignation if we are unconcerned about those harmed and that we are likely to be unconcerned about them if we have never empathized with them. Prinz recognizes that we need ‘a keen sense that human suffering is outrageous’ [ 2 , p.229], but can we develop such a sense if we strive for an impartiality that ‘involves bracketing off thoughts about victims’ [ 2 , p.229]? And what about cases in which human suffering is due to bad luck which does not involve any moral wrongdoing, like instances of congenital disabilities and natural disasters? In such cases, emotions like anger, indignation and outrage are out of place or irrational.

Additionally, anger can be as at least biased and immoral as empathy, say, the anger you feel at your opponent because you have lost a game, though you realize that the game was perfectly fair, and you entered into it voluntarily. Prinz is on firmer ground when he speaks about outrage and indignation, since these emotions seem to be anger which you believe to be morally justified. But because of the excessiveness of your self-concern, these emotions can still be overblown when you yourself are the victim of immoral behaviour.

Whether Empathy Is Necessary for Moral Concern, or could Block it

So much about exploiting empathy for good purposes. It might be objected, however, that in order to act out of concern, we evidently do not need to empathize. For instance, we might grab a pedestrian to prevent him or her from stepping out in front of a bus, without having had time to do any empathizing. True, but this may be because we have acquired a habit of acting in such ways because we have often in the past empathized with people in similar circumstances and, thereby, acquired a standing motivation to help them out. Thus, empathy may be necessary to make us concerned about others to start with, without subsequently being necessary for action out of concern on each and every occasion. 7

In the case of the pedestrian, there are no competing interests. But when there is such competition, one party often claims our spontaneous concern at the expense of others. Then our voluntarily directed, reflective empathy should step in to rectify matters. Consequently, the fact that we have developed standing desires that enable us to do the right thing on many occasions does not mean that engaging in empathy has been rendered redundant. Sooner or later spontaneous, selective empathy will assert itself, and the combat against its distortions must be resumed.

Prinz relates studies that show that people who found a dime in a phone booth are much more likely to help a passerby who has dropped some papers than people who did not find a dime. He concludes that a ‘small dose of happiness seems to promote considerable altruism’ [ 2 , p.220]. Certainly, a standing disposition to be of assistance is more likely to manifest itself if we are happy. When we feel that things are going well for ourselves, we are more bent on making efforts to assist those who are less fortunate and imaginatively to put ourselves in their shoes. Prinz thinks that this imaginative act could reduce the inclination to help because the ‘vicarious distress’ he sees empathy as involving ‘presumably has a negative correlation with positive happiness’ [ 2 , p.220]. But here it should be remembered, first, that empathy with the distressed does not involve actually feeling distress, but imagining feeling the distress others are believed to be feeling, which is less of a negative experience. Secondly, if we can do something to help the distressed, we may end up actually feeling satisfied.

Prinz also affirms that guilt ‘is a great motivator’ on the ground that subjects were much more disposed ‘to make some fund-raising calls for a charity organization after they administered shocks to an innocent person’ [ 2 , p.221]. But the fact that we are inclined to make up for an immoral act we believe we have committed by doing good is an expression of our sense of justice, and has been seen this does not rule out being motivated by empathy as well.

There is however something backward about Prinz’ conception of guilt as a motivator. He claims: ‘If we anticipate that an action will make us feel guilty, we will thereby be inclined to avoid the action’ [ 2 , p.219]. However, if an act makes us feel guilty, we must take it to be wrong. Now he also maintains: ‘A person who judges that stealing is wrong, for example, will be motivated to resist the urge to steal’ [ 2 , p.219]. It follows that if we anticipate that an act will make us feel guilty once we have committed it, we already conceive of it as wrong – since our committing it does not make it wrong – and, hence, we will already ‘be motivated to resist the urge’ to commit it, independently of the guilt we would feel were we to commit it.

It should be stressed, however, that empathy is not an end in itself; it is emphatically not the case that the more we empathize, the better. Voluntarily empathizing is a means to boost motivation to assist those in need, to enhance concern for them. But, as Bloom points out [ 1 , pp.133–46], people can empathize too much, so much that it can be harmful both to themselves and to those in need of their help. It can ‘burn out’ empathizers, make them depressed and emotionally exhausted. This is not surprising: after all, imagining feeling suffering is an unpleasant experience in itself, though not as unpleasant as actually feeling the suffering imagined. And it is not hard to understand how, say, doctors who are absorbed by acts of imagining the suffering of their patients might be overwhelmed and paralyzed by what they imagine and unable to help their patients effectively.

But conceding that empathy can be excessive, that there can be too much of it, is not conceding that it is redundant, that there cannot be too little of it. In moderate measures it may be an efficient means of enhancing flagging concern. A Buddhist scholar quoted by Bloom states the appropriate recipe thus: ‘meditation-based training enables practitioners to move quickly from feeling the distress of others to acting with compassion to alleviate it’ ([ 1 , p.141], emphasis added). 8 Bloom himself says essentially the same: ‘we know that feeling empathy for another makes you more likely to help them’, though ‘too much empathy can be paralyzing’ [ 1 , pp.155–6]. However, even if we do not get caught up in excessive empathy, but use it wisely to quicken our benevolent concern, it should be observed that we run the risk of being burnt out: for those who are greatly concerned to relieve the suffering in a world so full of misery as this one, awareness of the fact that, even if they were to comply with a very demanding morality, they could at best only relieve a tiny fraction of it could well be crushing. But the fact that a state of mind is crushing does not count against it being the state of a morally enlightened person, at least not as long as this is not allowed to prevent complying with moral demands. In itself, the contentment of a moral agent is not an objective of morality.

It could be desirable to enhance our capacity for empathy and concern by drugs, like oxytocin etc. if the discomfort this would cause us would be outweighed by the greater amount of good we would thereby accomplish. It might be asked whether these drugs work by making us more disposed to empathize, or be more motivated by the outcome of our empathizing. But these aspects are not easily separable, since if we become more disposed to engage in acts of imagination, these acts will be more protracted, and their content more vivid or detailed and, thus, it will have greater motivational impact. However that may be, such enhancement cannot render a reflective direction of imagination superfluous.

Conclusion: Better to Reform Empathy than Remove it

All in all, the picture that emerges is this. We have beliefs about how other individuals feel and how we can help them to feel better. There is both a set of properties such that: (1) if we believe individuals have any of these properties, this facilitates spontaneous empathy with these individuals, i.e. disposes us to imagine spontaneously how they feel, and (2) a set of properties such that if we believe that individuals have any of them, this hinders spontaneous empathy with them. In the former case, we will be spontaneously concerned about the well-being of these individuals; in the latter case, it will take voluntary reflection to empathize and be concerned about the individuals in question. We are also in possession of a sense of justice or fairness which not only animates us to benefit those whom justice requires to be benefited, but also to harm those whom justice requires be harmed. If, however, we do not empathize with individuals who should be benefited, or have been harmed, we will often not be sufficiently motivated to rectify injustices inflicted on them. Similarly, the incentive to punish is reduced if we empathize with those who have unjustly harmed.

Because we are equipped with a power to scrutinize the rationality of our responses, we might realize that some of the properties that we unthinkingly use to exclude individuals from our spontaneous concern do not in fact justify such exclusion. This would provide us with reason voluntarily to imagine more vividly the feelings of these individuals who have previously received little empathy from us and, as a result, be more concerned about their welfare, though presumably not as much as we are concerned about those with whom we spontaneously emphasize. Still, we should be wary not to employ voluntary empathy excessively, so that it gets in the way of acting out of concern.

This is basically in agreement with a picture we have earlier put forward [ 5 ]. We then suggested that there are two ‘core moral dispositions’ [ 5 , p.108], altruism and a sense of justice. They seem to be biologically based in part and, therefore, in principle open to enhancement by biomedical means. But we pointed out that such enhancement is not sufficient because our spontaneous altruistic concern is subject to various distortions, like the bias towards the near future [ 5 , pp.27–8], innumerateness or insensitivity to numbers [ 5 , p.30]), and in-group bias [ 5 , pp.119–20]. None of these considerations stands up to rational scrutiny. This realization is liable to change the pattern of our spontaneous concern, but our sense of justice is in even greater need of reflective refinement. It comprises a disposition to do what we think is just or fair. But what is just or fair is a topic of heated philosophical controversy, whether it is a matter of getting what we deserve, or something more egalitarian, etc. 9

Bloom writes that he has ‘been arguing throughout this book that fair and moral and ultimately beneficial policies are best devised without empathy’ [ 1 , p.207]. It might indeed be true that such policies are best devised without empathy, but it is doubtful whether we can be best motivated to act in accordance with them without empathy. Consider again a simpler situation in the realm of prudence. If we have to devise a general policy for possible future circumstances in which we have to choose between a smaller, but still acute, pain the same day and a significantly bigger pain a week later, it is easy to tell what the best policy is: to opt for the smaller pain the same day. The hard bit is to stick to this policy when the smaller pain will occur later today. To avoid backsliding we then have to counteract our spontaneous empathy with ourselves in the imminent future by voluntarily imagining what it will be like for us to suffer the greater pain a week later. We shall most probably never succeed in voluntarily directing our empathy to the extent that we become temporally neutral and care as much about the more remote as the closer future. But it is still better to have such an imperfectly reformed empathy than being without all empathy, spontaneous as well as reflective.

Bloom seems to concede something like this when, in speculating about how he would genetically engineer a child, he writes that he would be wary of removing empathy, but ‘would ensure that it could be modified, shaped, directed, and overriden by rational deliberation’ [ 1 , p.212]. This would be what we have called reflective empathy. Since he thinks that this child should be equipped with empathy, he must think it can do some good. His case against empathy must then rest on it being impossible in fact to modify it to the extent that its existence is better than its non-existence. Granted, empathy cannot be modified to the extent that it perfectly concords with the deliverances of rational deliberation, but it can be sufficiently reshaped that we are better off with it than without it, since in the latter case it seems that we would risk being totally unmotivated by any mental states beyond those of ourselves in the present.

Bloom concludes about empathy: ‘its negatives outweigh its positives – and there are better alternatives [ 1 , p.241]. The present conclusion is to the contrary that it is the positives that outweigh the negatives, and that there is no better alternative to empathy. Bloom seems to have reason in mind, but reason is not an alternative to empathy: it needs empathy as a motivator, and empathy needs reason for its motivational force to be properly directed and encompassing. Compassion and concern on which he places higher value than empathy are no more reliable as moral compasses. They, too, are biased and parochial, underpinned as they are by empathy, and in need of supervision by reason. 10

1 Concurring with Adam Smith that, in contrast to ‘pity’ and ‘compassion’, ‘sympathy’ may ‘without much impropriety, be made use of to denote our fellow-feeling with any passion whatever’ p765 [ 4 ], we have earlier employed the term ‘sympathetic concern’ (e.g. p109 [ 5 ]).

2 Cf. Coplan’s distinction between self-oriented and other-oriented perspective-taking pp9–15 [ 6 ].

3 Thus, empathizing is not imagining having any experience, as Bloom’s claim that it is ‘experiencing what they experience’ p3 [ 1 ] could suggest. If, say, we imagine seeing what others are seeing from their points of view, this does not qualify as empathy because it is not any feeling that is imagined. Additionally, it is odd to talk about empathizing with somebody who is feeling warm or surprised when these feelings are neither positive nor negative.

4 Experimental evidence for this hypothesis is summarized e.g. in Batson [ 7 ].

5 This is a reason why it is important not to confuse empathy with emotional contagion: we cannot directly infect ourselves with emotions at will.

6 Prinz claims: ‘Imagination sounds like a kind of mental act that requires effort on the part of the imaginer’ p212 [ 2 ]. But, as for instance Hume stressed, if we have regularly experienced one type of event being succeeded by another type of event, experiencing the first is likely to make us automatically imagine experiencing the other, especially if it is pleasant or unpleasant.

7 Here surfaces a difference between concern, on the one hand, and sympathy, pity and compassion, on the other, for although we might say that your act expressed concern for the well-being of the pedestrian, we would scarcely say that you felt sympathy, pity or compassion for the pedestrian. These emotions do seem to involve empathy on each and every occasion.

8 For a survey of the ancient Buddhist tradition of cultivating empathy, see McRae [ 8 ]. In this tradition, ‘empathy as imaginative projection’ ‘is assumed to be highly trainable’, ‘vastly under-utilitized’ p124 [ 8 ], and also that it ‘will stimulate compassion’ p125 [ 8 ]. That is to say, virtually what we argue.

9 Followers of Hume and Smith, like e.g. Kaupinnen [ 9 ], who believe that empathy is involved in moral judgment also contend that it can be regulated, but their view is different, and more contentious, than ours in at least two respects. First, we explore the role of empathy in one species of moral motivation , not its role in the making of moral judgments , let alone all kinds of moral judgments. In addition, Kaupinnen thinks that for his purpose empathy as regards reactive attitudes like resentment and gratitude is more central than empathy as regards concern for the well-being of others. Secondly, these theorists propose regulation by reference to an ideal perspective , which goes beyond the regulation we have here considered.

10 Many thanks to the reviewers and editor for valuable comments on an earlier version of this paper.

Self-Empathy Is Required to Empathize With Others

Creating a receptive space to help you empathize without projecting..

Posted March 5, 2021 | Reviewed by Jessica Schrader

In our previous post, " The Light and Dark Side of Empathy, " we wrote about how your motivations and intentions determine whether you use empathy to help or to harm. Self-empathy, as a practice, guides you to tune in to your inner world and to understand, or even modify, motivations and intentions.

By choosing to practice self-empathy, as a deeply personal exploration, you observe and integrate your own experiences. You bring awareness to your inner experiential, emotional and mental state. A part of yourself observes the aspect of yourself that experiences in an empathic manner. You create a space within yourself by bringing your mind into the inner world of your own experiences of thought and feeling and by suspending judgments you may have about yourself (Jordan, 1994). This inner space is open, expansive, and receptive.

Your inner life may be noisy with random fragments of thought and feeling. The practice of self-empathy orders these fragments.