Top Nav Breadcrumb

- Ask a question

The importance of critical thinking in the 21st Century

The International Baccalaureate (IB) will be hosting its annual African Education Festival in Johannesburg, South Africa on 27 – 28 February 2020 under the theme of Leading and Learning in the 21st Century, with a special focus on ”Inspire, Innovate, Integrate” .

Integrating Critical Thinking Into The Exploration Of Culture

When one thinks about culture, what often comes to mind are the foods, languages, celebrations, music, and clothing of people from different areas of the world. While these things are certainly part of culture, there are a lot more cultural components that are not quite as easy to see. As Sonia Nieto and Patty Bode note , “Culture includes not only tangibles such as foods, holidays, dress, and artistic expression but also less tangible manifestations such as communication style, attitudes, values, and family relationships” (p. 17 1).

English teachers have a special responsibility to help students navigate the components of culture that may not be easily visible. Many students studying English may eventually wish to travel, attend school, or work in other countries. Others may choose to work in industries that require them to interact with English speakers from many different backgrounds. Therefore, it is important that students are able to think critically about their personal experiences and cultural values, those of other people, and the potential conflicts differences may cause. This critical thinking will help them to navigate and resolve potential cultural misunderstandings.

This month the Teacher’s Corne r will present four successive activities to help students examine and deepen their understanding of culture:

Week 1: Reflecting on Hidden Cultural Rules, Part One Week 2: Reflecting on Hidden Cultural Rules, Part Two Week 3: Thinking About Intercultural Interactions Week 4: Successfully Navigating Intercultural Interactions

Educators are positioned to provide students with a chance to take part in activities and discussions that promote self-examination, reflection, and critical thinking. In doing so, teachers can help students begin to understand the less obvious parts of their own culture as well as those of other cultures. Activities like these, and the kind of thinking they require of students, have a lasting effect on how learners approach interacting with people from different backgrounds.

Reference: Nieto, S. and P. Bode. (2012). Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education (6 th ed.). Pearson.

Table of Contents

This week’s Teacher’s Corner encourages students to think critically about the unspoken rules and expectations of different cultures. Because English is a lingua franca—a common language used by speakers with different native languages—the ability to successfully navigate different cultural expectations is becoming more and more valuable.

As noted by K. David Harrison in his book The Last Speakers , “languages abound in ‘cultural knowledge,’ which is neither genetic nor explicitly learned, but comes to us in an information package—rich and hierarchical in its structure” (p. 58). Every language has its own cultural “information package,” including English. However, because English is studied and spoken by so many different types of people from various backgrounds, there is not one set of unspoken rules or expectations for all English speakers. Rather, as teachers of English, we must prepare our students to be aware of differences and be ready to work through any potential miscommunications that may occur.

Activity: Generating a list of behaviors and planning a skit

Time: 60 minutes

- To help students reflect on what defines culture and to understand that different cultural groups have rules and expectations that may not always be communicated directly.

- To listen, speak, read, and write about culture in English.

Materials: Culture Group Descriptions (Appendix A), Example Scenario (Appendix B), poster/chart paper, different color markers, student notebooks, pencils

Preparation:

- Decide how you will divide your class into groups. There should ideally be a minimum of four groups with 3 to 6 students in each one. If you have a small or large class, adjust groups accordingly.

- Prepare copies of the Culture Group Descriptions and cut them into fourths for distribution. Note that each group of students will be assigned a single culture description (1, 2, 3, or 4). If your class is divided into more than four groups, you can assign the same description to multiple groups, but each group will need its own copy.

- Figure out how you will share the Example Scenario with students, such as by projecting it or making copies.

- Begin by asking students what they think culture means. They can discuss this in small groups or as a whole class.

- Create a Culture Thinking Map on chart/poster paper by writing culture in a circle in the middle. As students share their ideas with the class, draw lines coming out of the circle to record students’ responses.

- Explain to students, “Every cultural group has visible or spoken elements that are easy to see and understand. These are things like common celebrations, foods, clothing, and music. Additionally, we can also observe common ways of interacting such as greetings and goodbyes. However, every culture also has rules and expectations that are not discussed, directly taught, or easy for other people to see.”

- Tell students that they are going to participate in an activity to examine some of the parts of culture that are not as easy to see.

- Have students get into groups according to the plan you prepared before starting the activity.

- Continue by explaining that each group will be assigned one description of a fictional culture. Working together, the groups should discuss the description and write down a list of behaviors they believe that members of their assigned cultural group would show in a conversation or interaction.

- Model this portion of the activity by choosing one or two of the characteristics from a Culture Group Description. Talk to students about what behaviors a person might show during a conversation or interaction as a result of each characteristic. Record responses in a chart as shown below.

- Have students create the same chart in their notebooks. Working together, each group should discuss the characteristics from the assigned description. Students should write down a list of behaviors they believe that members of their assigned cultural group would show in a conversation or interaction.

- Once groups have had adequate time to prepare a list of behaviors, tell students that they will now be given an example scenario. Say, “Using this scenario and the list of behaviors you wrote, your group will create a skit. The skit must be about the example scenario and the actors must demonstrate as many of the behaviors as possible. You will perform this skit for the rest of the class. Based on your skit, your classmates will try to determine some of the characteristics of your culture, so keep this in mind as you are working.”

- Display or distribute the example scenario, review it with students, and answer any questions they may have.

- As groups work on writing their skits, move around the room to ensure students understand the assignment. Note that not every student from a group must act in the skit, but all group members should help to write it.

- Students should write down a script or at least an outline of their skit in their notebooks in order to continue during the next class.

- Provide time for students to practice their skits. If needed, review each group’s culture description, list of behaviors, and skit to offer suggestions.

- After the activity is complete, collect all materials for use during upcoming classes.

In the next activity in this month’s Teacher’s Corner, students will perform and observe skits and work with classmates to describe each culture group.

Harrison, K. D. (2010). The Last Speakers: The Quest to Save the World’s Most Endangered Languages . Washington, DC: National Geographic Society.

During last week’s Teacher’s Corner activity, students began to think critically about what defines culture. They also planned a skit based on the characteristics of an assigned culture group. This week, groups will perform their skits as others observe and try to identify characteristics of each culture group.

Activities: Skit Presentations and Brainstorming

Time: Varies depending on the size of your class, but all groups will need to present skits, reflect on those they watch, and brainstorm a list of descriptors. Estimated time is 45-60 minutes.

Materials: Culture Group Descriptions (Appendix A), Example Scenario (Appendix B), poster/chart paper, different color markers, student notebooks, pencils, student skits (written and brought in by students)

- Copy the Skit Observation Table (shown in Procedure Step 3) on the board for student groups to use to record observations as they watch skits and discuss what they see. Students should copy the table into their notebooks before groups share their skits.

- If you have a very large class, with multiple groups representing each culture, you may choose not to have every group perform their skit in front of the whole class. Instead, you can divide up the class (in half, or in multiple sections) and have each section watch the groups in their section. If you divide up the class, make sure that all of the culture groups (1-4) are represented in each section. Every student should make observations about all the culture groups.

Activity one: Skit Presentations and Observations

- Begin by reviewing the purpose of the skits with students and answering any questions. Remind learners that the goal of the skit is to demonstrate the list of behaviors they made with their group based on their assigned Culture Group Description.

- Tell students that they will have 10-15 minutes to practice their skits before performing them for others. If you are splitting your class in half or into sections as described under Preparation, share the plan with students.

- Once the time allotted for practice has passed, draw students’ attention to the Skit Observation Table. Explain that as students present their skit, they should share the number of the culture group they are representing. Members of the audience should record this number on the Skit Observation Table. As they watch the skit, students should also note what behaviors they observe, as shown below.

- Once students have had a chance to view all of the skits from each of the other culture groups, they should work together with their group members for about 15 minutes to compare notes, discuss observations, and brainstorm ideas about characteristics of each culture. Characteristics should be recorded in the Skit Observation Table.

- After groups have had sufficient time to discuss and record characteristics, bring the class back together. Tell students that they will now share ideas in order to attempt to create a description of each cultural group.

- Label four sections of the board or four pieces of chart/poster paper with culture group 1, culture group 2, etc. Tell students that you will record the characteristics they share about each culture group and that they should also copy the information into their notebooks.

- Remind students that this is just a learning experience and that no one assumes any student shares the behaviors or characteristics of the culture group they represented for the activity.

- Beginning with Culture Group 1 on the board or chart/poster paper, have students volunteer to share characteristics that were observed during the skit. Continue with each culture group until a list of characteristics has been recorded for each one.

Activity Two: Descriptive Brainstorming

- Explain to students that now that a profile of each culture group has been established, the next step is to list words or phrases that describe each culture group. At this point, you can share the culture group Descriptions (Appendix A) either by photocopying, projecting, or having students read them aloud, to provide students with as much information as possible.

- Divide the class into four large groups or, if you have a large class, create smaller sections and assign each one a culture group to focus on. Provide students with chart/poster paper and markers to record their list.

- Tell students that they should carefully read the description and profile of their newly assigned culture group and think about positive and negative descriptions that may be used to describe the group. Inform the class that they will have 10 minutes to record as many positive and negative words as they can to describe the culture group they have been assigned. Have each group elect a recorder to write down student responses.

- Provide ample time for groups to review the list of characteristics generated about their assigned cultural group during the first activity, as well as the original culture group Description.

- Then, set a timer for 10 minutes and allow students to begin recording their one-word descriptions.

- What are some positive aspects of this culture group? What do you think they would do well? What would people like about someone from this group?

- What are some negative aspects of this culture group? What do you think they would not be very good at? What would people dislike about someone from this group?

- Once time is up, have each group select one student to share what their group wrote down to describe the others. Give each group ample time to share their list.

- What descriptors would you characterize as positive? Which ones are negative? Create a list for each.

- Which of the positive descriptors do you agree with most? Which do you disagree with? Why?

- Which of the negative descriptors do you agree with most? Which do you disagree with? Why?

- Do you think this is a fair representation of the culture group you represented during the skit? Why or why not?

- Ask students to find a partner that was assigned to a different culture group during Activity 1. Have partners share the reflections they recorded in their notebooks.

- Once partners have had time to discuss reflections, ask students to volunteer to share their feelings about this experience and whether their culture group was described accurately or not. Encourage students to discuss the implications of this activity beyond the classroom.

Next week, students will continue to think critically about culture as they add to their initial ideas about what makes up culture on the Culture Thinking Map from Week 1. Students will also begin to discuss and reflect on how cultural differences can make intercultural communication challenging at times.

So far this month in the Teacher’s Corner, students have had a chance to adopt characteristics of a fictional culture group, plan and perform skits, and observe and describe culture groups other than those they were assigned. Through critical thinking, reflection, and discussion, these activities have helped students recognize that culture includes more than just food, clothing, and celebrations. This week, students will add ideas to the Culture Thinking Map and reflect on potential breakdowns in communication that could happen when people interact.

PREPARATION

Time: 30-45 minutes Goals:

To help students continue to reflect on what defines culture.

To think about and discuss potential miscommunications or misunderstandings that could happen

during intercultural interactions.

To listen, speak, read, and write about culture in English.

Materials: culture group Descriptions (Appendix A), Example Scenario (Appendix B), Culture Thinking Map with students’ ideas about culture from Week 1, different color markers, chart/poster paper, student notebooks, pencils

Ensure that the Culture Thinking Map (Week 1) and descriptive lists (Week 2, Activity 2) are displayed in the classroom.

Gather copies of Culture Group Descriptions (Appendix A) and Example Scenario (Appendix B) , or be sure you have a way to project them.

ACTIVITY ONE: ADDING TO THE CULTURE THINKING MAP

Display the Culture Thinking Map from Week 1. Start by asking students to review the ideas about culture they previously added to the map.

Next, have students get into groups of 3-4.

Remind students to consider how they thought critically about culture during the other activities. Ask them to discuss additional ideas they would now add to the map.

Allow groups to discuss for five minutes. Then, have students share their ideas. Using a different color of marker, add new ideas to the Culture Thinking Map.

ACTIVITY TWO: REFLECTING ON INTERCULTURAL INTERACTIONS

Ask students to recall the number of the culture group they were assigned when they created and performed the skit. Have students hold up fingers to indicate which group they were a part of.

Tell students that for the next activity, they will need to create a new group of four students. Their new group should be made up of one member from each of the culture groups. It is OK if some groups have more than four members as long as each culture group is represented. Provide time for students to get into new groups.

Tell students that for the next activity, each of them will represent their assigned culture group. Students should approach the activity from their culture group ’s point of view.

Project or pass out the Culture Group Descriptions and remind students about the descriptive lists they created in Activity 2 during Week 2. Provide students a few minutes to review these items.

Explain to students that they will revisit the Example Scenario they used to plan their skits during Week 1. This time, students will participate in a discussion with classmates from each of the different culture groups and answer questions.

Display the following instructions for students to read:

Choose two culture groups. For each one, think about the description, the skit you

observed, and the descriptive list. What do you think would happen if members of both of these culture groups were in this scenario? Would people from the different groups interact easily and get along well? Would the interaction be difficult, or would anyone get upset?

List areas where you think the interaction might go well and areas where you think communication could be difficult. In your answers, refer to your descriptions of the culture group ’s behaviors and characteristics.

Repeat Steps A and B for a different pair of culture groups.

After students read the instructions, answer any questions about the task.

Tell students to write down their responses in their notebooks. Provide student s with at least 20 minutes to work in groups. As they do so, move around the room and observe.

When time is up, g ather students’ attention again. Ask learners to reflect on what they discussed and wrote down in their notebooks, thinking specifically about the reasons that intercultural interactions can be successful or challenging. Provide some examples by saying “For instance, in some cultures, direct eye contact is a sign of respect. However, in others, it is a sign of respect to not make eye contact. Or some cultures prefer to speak directly about issues when someone is upset, while others prefer to minimize feelings and maintain relationships. These differences could cause a misunderstanding.”

Givestudents5minutesingroupstogenerateafewreasonsthatinterculturalinteractionsmight succeed or be a challenge. Let students know that they will share their ideas with the class to create a new thinking map.

Writethewords“Factorsthatcanaffectinterculturalinteractions”inacircl einthecenterofa piece of chart paper or on the board. Have each group share the reasons they came up with and add them to the chart paper to create a new thinking map.

Onceallgroupshavesharedtheirideasandallnewideashavebeenaddedtothemap,explainto students that they will use this Intercultural Interactions Thinking Map during the next activity.

In next week’s Teacher’s Corner, students will bring together all of their ideas and reflections in order to think critically about how to successfully approach intercultural interactions.

Each week of this month’s Teacher’s Corner has required students to reflect and think critically in order to deepen their understanding of culture and how it can affect interactions. This week, students will apply their experience and knowledge to figure out how to make intercultural interactions successful, even if they are challenging.

Preparation

- To help students continue to reflect on what defines culture.

- To think about ways to avoid or mediate miscommunications or misunderstandings during intercultural interactions.

Materials: Culture Thinking Map (Week 1) and Intercultural Interactions Thinking Map (Week 3), student notebooks, pencils

1. Ensure that all of the thinking maps and descriptive lists from previous activities are displayed in the classroom so that students can see them.

2. If desired, assign students to participate in completely new groups. Alternatively, students can continue to work in the same groups used during Activity 2 of Week 3.

3. If you have a large class, you can make a plan for how students will present their scenes at the end of Activity 2. Instead of having each group present to the whole class, you can pair groups to present to each other.

Activity one: writing scenarios

1. Have students get into groups (see Step 2 under Preparation).

2. Give groups a few minutes to review the information on the Intercultural Interactions Thinking Map and the information they recorded in their notebooks about how different groups would interact with each other (See Step 6 in Week 3, Activity 2).

3. Tell students that they will work together with their group to create a scenario where a misunderstanding or miscommunication due to cultural differences might occur. Provide students with the examples below so that they understand expectations for this part of the activity.

a. Example 1: There are eight people in a sales department at a company. The two leaders have received a cash bonus for the achievements of their department. One leader comes from a culture where resources are shared amongst community members and accomplishments are celebrated by everyone. The other leader comes from a culture where the needs of each individual are most important and every person works for and keeps what they earn or receive. The two leaders must come up with a plan for what to do with the bonus money.

b. Example 2: A teacher is giving a test to his or her class. The teacher notices that three of the students from the same culture group are whispering and helping each other on the test. After class, the teacher asks these three students to stay and explain why they were cheating on the test. One student explains that they were simply trying to help each other get good grades and make their parents proud because their parents want them to do well in school. The teacher must decide whether the students should get in trouble and have to retake the test.

4. Let students know that another group of their classmates will act out the scenario they write. Allow time for students to ask questions and clarify what they are expected to do. Tell students that they will have 20 minutes to write down a scenario with their group.

5. As students are working, move around the room and check in with each group to ensure that the scenarios make sense and will work for others to act out. Help any groups that need guidance or may be struggling with ideas.

6. When 20 minutes have passed, check to see that all groups have finished. If needed, give students more time to complete the task.

7. When students are done, collect all of the scenarios.

Activity TWo: Acting out and Reflecting on scenarios

- Read the scenario.

- Discuss the different elements of culture that may cause conflict or misunderstanding in the scenario. Write these cultural elements down on the same paper as the scenario.

- Think about possible ways to resolve the conflict or misunderstanding. Write these resolutions down on the same paper as the scenario.

- Make a plan for how to act out the scenario using one of the resolutions your group thought of.

- Answer any questions that students may have about the assignment.

- Tell students they will have 15 minutes to discuss the scenario, brainstorm possible resolutions, and practice performing the scene.

- When 15 minutes have passed, tell students that in a moment they will present their scene to their classmates. If you have paired groups together, as noted in Step 3 under Preparation, explain the plan to students.

- Explain to students that as they watch their classmates, they should reflect on a few things. Write the following questions on the board:

a. What were the different cultural elements that caused a problem in this situation?

b. How was the conflict avoided or resolved?

- After each group performs their scene, ask the rest of the class (or the other group if groups are paired) to discuss and share their answers to the reflection questions.

- After all groups have shared their scenes, ask students to reflect on the following questions in their notebooks in class or for homework:

a. What are some possible reasons that intercultural interactions can be successful or not?

b. What are some actions you, or any person, could take to prevent or resolve misunderstandings when interacting with people from different backgrounds?

The activities in this month’s Teacher’s Corner have aimed to help students increase their cultural awareness through reflection and critical thinking. Because speakers of English come from many different backgrounds, the ability to recognize and acknowledge the less obvious elements of culture is an important skill for students studying English. With this knowledge and a better understanding of how to apply it to intercultural interactions, teachers are setting students up for success as they communicate in English.

- Privacy Notice

- Copyright Info

- Accessibility Statement

- Get Adobe Reader

The value of intellectual virtues in critical thinking education

Author: beencke, andrew.

In the 21st century, educational institutions almost universally aim for students to be critical thinkers. At a time when the standards and demand for truth in public discourse seem at an all-time low, and misinformation is used aggressively to manipulate the beliefs and actions of people, this aim seems more important than ever. Yet, being a critical thinker involves more than developing a collection of skills. It also involves being inclined to use those skills when making decisions and forming beliefs. As such, critical thinkers possess character traits including intellectual curiosity, intellectual autonomy, and intellectual humility. This study explores the perspective that critical thinking dispositions are best understood as intellectual virtues. It applies the lens of responsibilist virtue epistemology, rooted in the works of Baehr (2011), Roberts and Wood (2007), and Zagzebski (1996) to form an analytic framework that operationalises the virtues as character traits, oriented toward the epistemic good, and, as per the Aristotelian view of moral virtue, are located at the mean point between vicious extremes. This exploratory case study investigates the questions: How might classroom culture impact the development of intellectual virtues in primary students? Additionally, how might teachers’ values and beliefs influence this development? Observations of the two classes, in Year 1 and 5 at the same state-run primary school in Australia, occurred weekly for ten weeks. Data collected included field notes, audio recordings, interviews, and questionnaires. To operationalise the intellectual virtues for analysis, an analytic framework was developed through a synthesis of philosophical, psychological, and educational literature on the virtues: the love of knowledge, intellectual curiosity, intellectual autonomy, and intellectual humility.Interpreting the impact of classroom culture through the intellectual virtue lens resulted in some potentially valuable insights. Patterns in the interaction, dialogue, learning activities and goals of the classrooms were interpreted as the practice and habituation of intellectually virtuous or vicious behaviours. These observations present some fruitful considerations for teachers as they look to integrate their pedagogical knowledge with their understanding of critical thinking (Ab Kadir, 2017). There was also an indication that the virtue support provided in the classroom cultures could be, at least partially, explained by the teachers' values and beliefs. Valuing student care, classroom function and the epistemic good emerged as significant values which might, at times, be in conflict. The discussion around these tensions, and the potential downward pressure of an education system with neoliberal values, highlight some deeper issues at the heart of critical thinking education.

Advertisement

Communication, Critical Thinking, Problem Solving: A Suggested Course for All High School Students in the 21st Century

- Published: 05 December 2013

- Volume 44 , pages 63–81, ( 2013 )

Cite this article

- Terresa Carlgren 1

3829 Accesses

23 Citations

Explore all metrics

The skills of communication, critical thinking, and problem solving are essential to thriving as a citizen in the 21st century. These skills are required in order to contribute as a member of society, operate effectively in post-secondary institutions, and be competitive in the global market. Unfortunately they are not always intuitive or simple in nature. Instead these skills require both effort and time be devoted to identifying, learning, exploring, synthesizing, and applying them to different contexts and problems. This article argues that current high school students are hindered in their learning of communication, critical thinking, and problem solving by three factors: the structure of the current western education system, the complexity of the skills themselves, and the competence of the teachers to teach these skills in conjunction with their course material. The article will further advocate that all current high school students need the opportunity to develop these skills. Finally, it will posit that a course be offered to explicitly teach students these skills within a slightly modified western model of education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Is Empathy the Key to Effective Teaching? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Teacher-Student Interactions and Student Outcomes

Teacher-Student Interactions: Theory, Measurement, and Evidence for Universal Properties That Support Students’ Learning Across Countries and Cultures

What are the key elements of a positive learning environment? Perspectives from students and faculty

A model of education as organized from western countries such as Canada, Great Britain, the United States, and some European nations by way of organizational structure (identified curricular outcomes, assessment strategies, hierarchical administrative levels).

Immersion in terms of critical thinking instruction refers to “deep, thoughtful, well understood subject-matter instruction in which the students are encouraged to think critically in the subject … but in which general critical thinking principles are not made explicit” (Ennis 1989 , p. 5).

Infusion as it refers to critical thinking involves the explicit instruction of critical thinking principles and strategies in conjunction with the subject material (Ennis 1989 , p. 5).

5 credit course as per government of Alberta standards (Alberta, Canada), http://education.alberta.ca/media/6719891/guidetoed2012.pdf , p. 42.

See basic structure of Alberta Education curriculum. Example from Science 10; http://education.alberta.ca/media/654833/science10.pdf .

Note: the curricular framework for this course is modelled after that of some curriculum in Alberta (Alberta Education 2005 ).

Alberta Education. (2005). Science 10 . Retrieved from http://education.alberta.ca/media/654833/science10.pdf .

Alberta Education. (2008). Mathematics grades 10–12 . Retrieved from http://education.alberta.ca/media/655889/math10to12.pdf .

Alberta Education. (2012). Guide to education: ECS to grade 12 . Retrieved from http://educaiton.alberta.ca/media/6719891/guidetoed2012.pdf .

Alliance for Excellent Education. (2011). A time for deeper learning: Preparing students for a changing world. Education Digest, 77 (4), 43–49. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=5&hid=12&sid=9695cbbb-ab96-496a-941e-35fa2bee2852%40sessionmgr4 .

Berger, E. B., & Starbird, M. (2012). The 5 elements of effective thinking . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Google Scholar

Brookfield, S. D. (1995). Becoming a critically reflective teacher . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Conley, D. T., & McGaughy, C. (2012). College and career readiness: Same or different? Educational Leadership, 69 (7), 28–34. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&hid=12&sid=9695cbbb-ab96-496a-941e-35fa2bee2852%40sessionmgr4 .

Covey, S. (2004). The 7 habits of highly effective people: Restoring the character ethic . New York: Simon & Schuster.

Crenshaw, P., Hale, E., & Harper, S. L. (2011). Producing intellectual labour in the classroom: The utilization of a critical thinking model to help students take command of their thinking. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 8 (7), 13–26. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=333f52c4-101e-4d9f-89e7-1088c51b14e7%40sessionmgr15&hid=19 .

Dobozy, E. (2012). Failed innovation implementation in teacher education: A case analysis. Problems of Education in the 21st Century, 40 , 35–44. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=333f52c4-101e-4d9f-89e7-1088c51b14e7%40sessionmgr15&hid=19 .

Ennis, R. H. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarification and needed research. Educational Researcher, 18 (3), 4–10. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/stable/pdfplus/1174885.pdf?acceptTC=true .

Ennis, R. H., & Millman, J. (1985). Cornell critical thinking test level x . Pacific Grove, CA: Midwest Publications.

Greenstein, L. (2012). Assessing 21st century skills: A guide to evaluating mastery and authentic learning . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Holloway-Libell, J., Amrein-Beardsley, A., & Collins, C. (2012). All hat & no cattle. Educational Leadership, 70 (3), 65–68. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?sid=ec665c98-aef1-44e8-8737-016b87157907%40sessionmgr13&vid=5&hid=1 .

Johanson, J. (2010). Cultivating critical thinking: An interview with Stephen Brookfield. Journal of Developmental Education, 33 (3), 26–30. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=14&sid=333f52c4-101e-4d9f-89e7-1088c51b14e7%40sessionmgr15&hid=19 .

Jonassen, D. H. (2011). Learning to solve problems: A handbook for designing problem-solving learning environments . New York: Routledge.

Jonassen, D. H. (2012). Designing for decision making. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60 (2), 341–359. doi: 10.1007/s11423-011-9230-5 .

Article Google Scholar

Kassim, H., & Fatimah, A. (2010). English communicative events and skills needed at the workplace: Feedback from the industry. English for Specific Purposes, 29 (3), 168–182. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/science/article/pii/S0889490609000635 .

Kirikkaya, E. B., & Bozurt, E. (2011). The effects of using newspapers in science and technology course activities on students’ critical thinking skills. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 44 , 149–166. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=2e1f2c2a-6199-4516-a3d0-5114f7c35314%40sessionmgr15&hid=19 .

Paige, M. (2012). Using VAM in high stakes employment decisions. Phi Delta Kappan, 94 (3), 29–32.

Passini, S. (2013). A binge-consuming culture: The effect of consumerism on social interaction in western societies. Culture & Psychology, 19 (3), 369–393. doi: 10.1177/1354067x13489317 .

Patterson, K., Grenny, J., & McMillan, R. (2011). Crucial conversations: Tools for talking when stakes are high (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2008). The miniature guide to critical thinking concepts and tools (5th ed.). Dillon Beach, CA: The Foundation for Critical Thinking.

Raybould, J., & Sheedy, V. (2005). Are graduates equipped with the right skills in the employability stakes? Industrial and Commercial Training, 37(4/5), 259–263. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/docview/214105484/fulltextPDF/13C3AF7848A26CBC442/26?accountid=9838 .

Richardson, J. (2011). Tune into what the new generation of teachers can do. Phi Delta Kappan, 92 (4), 14–19.

Robinson, K. (2011). Out of our minds . Chichester, West Sussex: Capstone Publishing Ltd.

Rosefsky, S., & Opfer, D. (2012). Learning 21st-century skills requires 21st-century teaching. Phi Delta Kappan, 94 (2), 8–13.

Sahlberg, P. (2006). Education reform for raising economic competitiveness. Journal of Educational Change, 7 , 259–287. doi: 10.1007/s10833-005-4884-6 .

Schleicher, A. (Ed.) (2012). Preparing teachers and developing school leaders for the 21st century: Lessons from around the world . Retrieved from http://site.ebrary.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/lib/ucalgary/docDetail.action?docID=10589565 .

Sherblom, P. (2010). Creating critically thinking educational leaders with courage, knowledge and skills to lead tomorrow’s schools today. Journal of Practical Leadership, 5 , 81–90. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=11&hid=12&sid=9695cbbb-ab96-496a-941e-35fa2bee2852%40sessionmgr4 .

Spencer, J. T. (2013). I’m a better teacher when students aren’t tested. Phi Delta Kappan, 94 (5), 72–73.

Tsang, K. L. (2012). Development of communication skills using an embedded approach for the evolving professional. The International Journal of Learning, 18 (3), 203–221. Retrieved from http://web.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.lib.ucalgary.ca/ehost/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=3&sid=924c3e4d-4fa2-4f95-a769-cbd05ada6724%40sessionmgr4&hid=28 .

Williamson, P. K. (2011). The creative problem solving skills of arts and science students—The two cultures debate revisited. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 6 , 31–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2010.08.001 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Terresa Carlgren

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Terresa Carlgren .

Course Syllabus and Outline

Title: Communication, Critical Thinking, and Problem Solving (an introduction)

Course Components

No exclusionary, discriminatory, or derogatory material will be taught in this course, nor will the content in this course be deemed controversial in any way.

Philosophy and Rationale

Much of our thinking, left to itself, is biased, distorted, partial, uniformed or down-right prejudiced. Yet the quality of our life and that of what we produce, make, or build depends precisely on the quality of our thought. Shoddy thinking is costly, both in money and in quality of life. Excellence in thought, however, must be systematically cultivated (Paul and Elder 2008 , p. 2).

The skills required of today’s youth are more pronounced than that of the past. Students are required to have basic knowledge of content in areas of Science, Math, and English; as well as technological skills, problem solving skills, critical thinking skills, and the ability to communicate (Sahlberg 2006 ). However, with the time constraints placed on teachers, knowledge outcomes taking priority on learning due to the high stakes standardized achievement tests, and an understanding that the particular skills of communication, critical thinking, and problem solving require explicit instruction (Rosefsky and Opfer 2012 ); students are not mastering these skills to an acceptable standard.

In order for students to acquire and master the skills necessary to compete and be successful in the work force, post secondary education, and life; students must have the opportunity to engage by learning these skills through practice, application, and devoted explicit attention. Furthermore, students must explore these skills without fear of failure but rather with hope that they can improve and move forward from the learning experience. In this way, learning these skills as a secondary item within the context of another content based course will not do the students justice.

Historically, the skills of sewing, cooking, woodworking, and mechanics where offered in high school as application based courses that required hands on and explorative learning with teacher guidance. More recently computer courses, and digital citizenship are taking hold in schools to teach students these skills. There is no reason why the skills of communication, critical thinking, and problem solving should be treated any differently.

Without the structure and organization of education making drastic changes to mandate these skills be made more of a priority in the classroom, it is feared that the teaching and learning of these skills will remain an oversight. It is unfortunate that the students; citizens, economic and market contributors of our future, will be underserved. It is with these reasons that this course offering takes place; such that an opportunity within the current educational structure can provide students the opportunity to guard themselves with new foundational skills for the future.

General Learner Expectations

By the end of this course, it is expected learners will have developed and ascertained explicit knowledge of communication, critical thinking and problem solving. More importantly, students will have acquired the skills of communication, critical thinking, and problem solving through application, exploration, and trial and error, such that they can utilize these skills in different contexts of their lives in preparation for the work force or post-secondary education.

Specific Learner Expectations

The following is a list of specific learner expectations for the course. Please note that the units identified for this course are titled ‘Skill-sets’ for a reason as they are not discrete topics to be taught in isolation, but rather guides toward the encompassing theme of acquiring these skills. This course is in no way designed as a check the outcome box course, nor is it organized in order by skill or outcome number. Rather, the outcomes and skill-sets must be taught in conjunction with each other through the duration of the course with trust being given to the fact that through student exploration and leadership; along side teacher guidance and facilitation, students will improve on their existing skill-set for these skills.

Skill Set A: Critical Thinking Skills Footnote 6

Knowledge Outcomes: (Students will be able to)

A.K.1 Define the difference between fact and inference.

A.K.2 Derive criteria for which to judge a problem or predicament.

A.K.3 List the elements of thought associated with critical thinking as per one critical thinking model (Paul and Elder, Rusten and Schuman).

A.K.4 Identify inherent and hidden bias in an argument.

A.K.5 Identify faults in thinking due to oversimplifying or over generalizing issues or problems.

A.K.6 Identify and state the purpose of thinking.

Skill Outcomes: (Students will be able to)

A.S.1 Utilize background knowledge to solve a problem or predicament.

A.S.2 Apply evidence to solve a problem or predicament.

A.S.3 Express an argument that is logical, clear, and concise.

A.S.4 Derive and model a process by which to critically analyze, think, and solve a problem or predicament that involves a reasonable, logical, and relevant thinking strategy.

A.S.5 Explore alternative options and methods before drawing a conclusion.

A.S.6 Illustrate and explore the consequences and implications following the solution of a problem or issue.

A.S.7 Model, display, or perform the ability to think critically through verbal, written, and physical means.

Attitudes Outcomes: (Students will)

A.A.1 Believe that it is possible for themselves to solve problems with a reasonable level of confidence.

A.A.2 Have confidence that they are able to ascertain information needed to help themselves think critically about a problem or issue.

A.A.3 Respect the diverse nature of thinking and problem solving that allows for others’ opinions and arguments to be taken into account without discrimination.

Skill Set B: Problem Solving Skills

B.K.1 Define convergent and divergent thinking.

B.K.2 State that for any given problem there is more than one problem solving strategy.

B.K.3 List possible problem solving strategies that exist.

B.K.4 State that problem solving strategies are used in context and explore the types of contexts that might exist.

B.K.5 Identify that for any problem solving strategy there must be an evaluative component and an ability to modify the strategy to fit a new context or problem.

B.S.1 Derive and model, illustrate, or describe a problem solving strategy that is context specific.

B.S.2 Derive and model a personal problem solving strategy to solve a personal problem.

B.S.3 Solve problems using mathematical reasoning.

B.S.4 Solve problems using technological means or supports.

B.S.5 Solve problems by modeling existing economic structures.

B.S.6 Solve problems by modeling existing political structures.

B.A.1 Have improved self-confidence in attempting to solve problems in a number of different contexts.

B.A.2 Be proud of the problem solving ability they have acquired.

B.A.3 Feel empowered to attempt new problem solving methods that are logical and relevant without fear of failure.

Skill Set C: Decision Making Skills

C.K.1 Identify that decision making is a process toward problem solving.

C.K.2 Identify personal bias in an argument.

C.K.3 State the difference between dialectic and rhetorical arguments.

C.K.4 Illustrate the types of decisions expected in personal, professional, and civic lives.

C.K.5 Describe the difference between rational and emotional expressions.

C.K.6 State and explain the difference between normative and naturalistic decision making.

C.K.7 Define the term dilemma.

C.K.8 State that the primary purpose of decision making is to decide on the best option, or provide maximum utility.

C.K.9 State that decision making can be made based on what is most consistent with personal beliefs or past experiences.

C.K.10 Identify that there is uncertainty and risk associated with every decision.

C.S.1 Construct a decision making process that includes identification, evidence, evaluation and modification of a problem.

C.S.2 Construct and apply a method of decision making to solve personal problems.

C.S.3 Construct and apply a method of decision making to solve professional problems.

C.S.4 Construct and apply a method of decision making to solve civic problems.

C.S.5 Examine positive and negative methods of modifying and changing decisions after they have been made.

C.S.6 Examine circumstances by which to modify, change, or renegotiate a decision.

Attitude Outcomes: (Students will)

C.A.1 Acknowledge that a commitment needs to be made upon making a decision.

C.A.2 Take ownership of decisions made using the decision making skills.

C.A.3 Understand that decisions require a course of action that is intended to yield results that are satisfying for special individuals.

C.A.4 Reflect on decisions made in their life and decide if they were appropriate or not.

Skill Set D: Communication Skills

Knowledge outcomes: (students will be able to).

D.K.1 Identify factors affecting communication.

D.K.2 State that communication involves more than one person.

D.K.3 Identify and explore the roles of speaker and listener in any conversation.

D.K.4 List and explore different environments involving communication (i.e.; formal language vs. slang, workplace vs. home life).

D.K.5 Describe the difference between teamwork and collaboration.

D.K.6 Describe what effective and ineffective communication looks, sounds, and feels like.

D.K.7 Explain the role of respect, honesty, fairness, and reason in any communication interaction.

D.S.1 Model and illustrate different conflict resolution strategies.

D.S.2 Identify and illustrate factors affecting teamwork.

D.S.3 Communicate effectively with peers while working collaboratively as a team.

D.S.4 Communicate effectively with teachers and parents regarding conflicts and successes.

D.S.5 Communicate clearly, logically, and precisely in verbal and written modes.

D.S.6 Ask and accept help in communicating when needed.

D.A.1 Feel empowered to communicate with peers.

D.A.2 Have confidence in the skill of communicating to discuss difficult issues with parents, teachers, and employers.

D.A.3 Feel empowered to ask and accept help by communicating in an appropriate fashion without fear of rejection or judgment.

Course Assessment

The assessment for this course is by way of individual student improvement in conjunction with final skill aptitude of the above stated skill sets by course end. This improvement and aptitude can be measured through a number of different means and will depend on the structure of the course as arranged and organized by the teacher. Outlined below are some classroom activities and possible assessments that might be of benefit to teachers planning this course.

Activities:

A pre and post written statement of the intention for being in the course and the problems and skills a student would like to solve and understand.

Assessed formatively (both pre and post) for critical thinking skills such as clarity of work, logic, reasoning, and evidence provided.

Pre and post formative assessments then evaluated for level of improvement.

Debate as a form of argument, decision making, communication and problem solving.

Following and respecting debate rules and roles of speaker/listener.

Utilizing rubrics for argument, decision making, communication and problem solving.

Market modeling—modeling the course as a competitive market with students given roles based on an application from them on their expertise and motivation toward the given problem. The roles would dictate a level of income for the student as well as a level of responsibility and leadership for them.

Assessed by way of improvement and movement ‘up the market ladder’—i.e.—what by way of promotion, what conflict resolution strategies or problems needed to be overcome, how long did it take to resolve or solve the problem?

Take into account rationale for why students have chosen their particular role (provided this rationale is given in a clear, appropriate, relevant, and significant manner)—i.e. standard of living, other priorities at the time etc.

Socratic Seminar on issue at hand to interpret and illustrate improvement in speaking and communicating an argument.

Assessed by way of quality and strength of participation and argument.

Resume of students skills ascertained and improved on through the course.

Cross curricular problems and projects modeling real life i.e. effects of globalization, and marketization on students by multinational companies. Projects to be displayed and presented to the class.

Assessed by way of rubrics (teacher and peer).

Likert scale survey for teacher and student on level of improvement of outcomes throughout the course.

Utilization of pre-existing rubrics i.e. Decision Making (Jonassen 2012 ).

Cornell CT Test level X for critical thinking as a pre and post test? (a quantitative assessment ordered from http://www.criticalthinking.com/getProductDetails.do?code=c&id=05501 ) (Ennis and Millman 1985 ).

Assessment strategies as well as possible outcomes for skill-sets can be found in Greenstein’s ( 2012 ), Assessing 21st Century Skills: A guide to evaluating mastery and authentic learning .

It is expected that all students will learn skill-set outcomes through the duration of the course. The question is how much will be learned? The answer depends on the individual student as well as their incoming skill level in each given area. In this case equal does not mean equitable and the goal of assessment for this course is to ascertain what improvement as well as final level of understanding an individual student has.

It should be stated that the nature of the course is student-centered and driven by the student. The teacher, however, is responsible for setting up the course and providing students an opportunity to explore this learning. Therefore, the teacher must come up with valid, rich, open activities for students to work within while at the same time ideally allowing the students to come up with the problems, scenarios, and arguments with which to discuss and solve. Explicit instruction may be necessary but should be severely limited allowing students ample opportunity for application and practice.

It is highly recommended that students work the duration of this course in groups (and differing groups) as it is here that communication, collaboration, and teamwork skills will be developed. It is further recommended that students be a part of the assessment process in deciding on the nature of the assessments, the criteria for the assessment, and in self and peer assessment. Allowing students to direct and lead requires trust and openness on the part of the teacher but is in fact part of the learning process.

Learning Resources

Since the premise of this course is for the teacher to be a ‘guide on the side’ and not a ‘sage on the stage’, there are no required learning resources for this course. However, it is recommended that teachers undertake professional development in the skill-set areas to ensure they have developed the necessary skills to pass on. Books such as: Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher by Brookfield, Learning to Solve Problems: A Handbook for Designing Problem - Solving Learning Environments by Jonassen, 7 Habits of Highly Effective People , Crucial Conversations, and The 5 Elements of Effective Thinking would be an introduction. Journal articles and professional publications regarding 21st century skills and the development of these would be helpful. Finally, professional development seminars or sessions by leading experts such as Richard Paul from The Foundation for Critical Thinking would be almost necessary.

From this learning, the teacher will need to develop a tool kit of resources at their disposal in which to best help their students. The nature of the course being student-centered will require a teacher to be flexible in the work that is undertaken. The teacher will also have to be reactive to issues, problems, and learning scenarios that take place in the classroom. However, as this is a course in allowing the students to ascertain skills in problem solving, critical thinking, and communication, it must be mentioned that it is the students who are doing the brunt of the work and actually doing the problem solving and critical thinking themselves. For instance, it would not be sufficient for a question to be: What book should we read to learn critical thinking? And have the answer to the problem be: go ask the teacher and he/she will tell us. Rather the answer should be: let us go to the library or use the internet and find out which book is the best book. What options are available? What type of critical thinking are we looking at? What is critical thinking? Who are the leading experts in the field? What bias do they have? Where can I actually find or order these books? What cost and what is my budget? In the end, a seemingly simple question—is wrought with learning experiences by the student provided the teacher take a backburner to the work and allow the student to take the reins.

Course Evaluation

The open nature of this course allows for a teacher at any time to make changes to the structure, organization, and assessment of the course due to evaluation and reflection. The evaluation and reflection of this course should therefore be ongoing by the student and teacher immersed in the learning environment. The teacher is responsible for periodically seeking feedback from students regarding the nature of the course, as well as professionally reflecting themselves on the presentation of the course to their students.

The teacher is also responsible for keeping records of the course, as well as feedback collected that identifies the (a) strengths and weaknesses of the course as it is being facilitated, (b) activities and assessments being implemented in the course, and (c) improvements to the course for a later date. The teacher should ideally create a long range plan (or running calendar) that becomes more descriptive as the course proceeds, about the level of difficulty, quality of problems, activities, resources, feedback, and assessments being utilized in the course to reference at a later date. Finally, the teacher should be able to provide evidence to the local school authority at any time in order for the authority to monitor, evaluate, and report progress should it be required.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Carlgren, T. Communication, Critical Thinking, Problem Solving: A Suggested Course for All High School Students in the 21st Century. Interchange 44 , 63–81 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-013-9197-8

Download citation

Received : 19 April 2013

Accepted : 21 November 2013

Published : 05 December 2013

Issue Date : December 2013

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-013-9197-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Communication

- Critical thinking

- Global market

- High school course

- Problem solving

- Western model of education

- 21st Century

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Reviewer: Trends, Networks and Critical Thinking in the 21st Century

Related Papers

Springer Series in Design and Innovation

Sandra Regina Rech

The potential of trends management is originated in the ability to understand the changes in human behavior and to translate this knowledge in guidelines that can bring innovation. The qualitative approach considers the society composed of individuals and groups, who share meanings according to collective expectations and perspectives. Based on these precepts, the researcher in the field of trends investigates processes, facts and situations in the social scene that, interconnected, may explain the analyzed phenomenon. Through literature review and theoretical problematization, the concepts and approaches referenced in qualitative research and trends management are discussed, evidencing the methodology and guiding assumptions of transformations in the patterns of human behavior.

Alton C. Thompson

The trend of our species has been downward, toward extinction; this essay tries to understand that trend.

Andrey Korotayev , Nicholas Mitiukov

The present yearbook (which is the fourth in the series) is subtitled Trends & Cycles. It is devoted to cyclical and trend dynamics in society and nature; special attention is paid to economic and demographic aspects, in particular to the mathematical modeling of the Malthusian and post-Malthusian traps' dynamics. An increasingly important role is played by new directions in historical research that study long-term dynamic processes and quantitative changes. This kind of history can hardly develop without the application of mathematical methods. There is a tendency to study history as a system of various processes, within which one can detect waves and cycles of different lengths – from a few years to several centuries, or even millennia. The contributions to this yearbook present a qualitative and quantitative analysis of global historical, political, economic and demographic processes, as well as their mathematical models. This issue of the yearbook consists of three main sections: (I) Long-Term Trends in Nature and Society; (II) Cyclical Processes in Pre-industrial Societies; (III) Contemporary History and Processes. We hope that this issue of the yearbook will be interesting and useful both for historians and mathematicians, as well as for all those dealing with various social and natural sciences.

The development of increased and accessible computing power has been a major agent in the current emphasis placed upon the presentation of data in graphical form as a means of informing or persuading. However research in Science and Mathematics Education has shown that skills in the interpretation and production of graphs are relatively difficult for Secondary school pupils. In this paper we explore the conjecture that the use of computers in education has the potential to revolutionise the ways in which children learn graphing skills. We describe research with 8 and 9 year olds using on a pedagogic strategy which we call Active Graphing, in which spreadsheets are use to collect and present data from practical experiments, and present results which indicate that children gain higher levels of interpretative skills, particuarly in terms of the use of trend, through this approach than would be expected in traditional classrooms.

Jorge Rodriguez

The purpose of articulating these two texts is to establish connections between the basic definitions of Trend Studies and Cultural Studies. Two fields of research with both humanistic and scientific foundations. This link should help build a new perspective for the study of trends provided they work on humanistic perspective that can be intertwined with a business side of culture. Martin Raymond (2010) is currently one of the key thinkers for Trend Studies and brings with this book a non-academic perspective in an effort to integrate knowledge into business. On the other side, Chris Barker (2008) sets a group of relevant definitions and considerations around Cultural Studies that help us create a framework for it. Both texts are somehow introductory and descriptive and open the opportunity to establish relations between concepts.

Modapalavra e-periódico

This text, an integral fragment of the ongoing master's research, has as main theme the theoretical-conceptual approach between trends and visual management, aiming to qualify the trend analysis method proposed by Dragt (2017) from principles and tools of visual management . In methodological terms, the article is designed in the moments of conceptualizing important terms through the Bibliographic Review, as well as the collection, reduction, categorization and interpretation of data via Qualitative Data Analysis. Furthermore, the text is classified as being of a basic, qualitative nature and with descriptive objectives. The results achieved demonstrate that the principles and tools of visual management add different advantages to the process, such as innovation, agility and encouraging the collaboration of the participants of those involved in the analysis of trends.

ModaPalavra

Ana Marta M. Flores

The present paper intends to discuss the development and consolidation process of Trend Studies, as a transversal area with transdisciplinary characteristics that was developed in connection with the concepts and practices of areas such as Cultural Studies. The numerous perspectives of Trend Studies and their different associations promoted a dispersed development that should be considered and deconstructed by means of finding common points and practices, or different perspectives, to generate a greater cohesion of concepts and methodologies. In this sense, it is important to present a model for the purpose of systematic identification and observation of trends. The result can generate a parallel process of cultural analysis capable of contributing to a basis for the generation of strategic solutions for institutional and social problems, in a new approach to culture management.

Ronny Berndtsson

The focus of this work, ongoing Postdoctoral research consequence, is to ascertain the importance of qualitative research in an institution focused on the study and on the trends application within the understanding context of why and how they manifest themselves. The Trends Studies should be seen, in this sense, as a process that tries to sustain a constant dialogue with the consumer, guiding the designers in the design of fashion products in line with the wishes and needs of the market. Therefore, it is defined as a cross-sectional analysis of society aiming at identifying opportunities for strategic development and connecting them with the future needs of the consumer, in order to achieve the innovation process of products and services. The qualitative approach considers society composed of individuals and groups who share meanings according to expectations and collective perspectives. From this methodological design, the researcher investigates processes, facts and situations in the social scene which, interconnected, can explain the phenomenon analyzed. In summary, it is believed that the qualitative research, aiming at prospecting trends, will contribute positively and provide a critical view of students and fashion professionals in relation to the phenomenon of trends and fashion system while linked to each other.

Modelling our Changing World

Jennifer Castle

The previous Chapter noted there are benefits of non-stationarity, so we now consider that aspect in detail. Non-stationarity can be caused by stochastic trends and shifts of data distributions. The simplest example of the first is a random walk of the kind created by Yule, where the current observation equals the previous one perturbed by a random shock. This form of integrated process occurs in economics, demography and climatology. Combinations of I(1) processes are also usually I(1), but in some situations stochastic trends can cancel to an I(0) outcome, called cointegration. Distributions can shift in many ways, but location shifts are the most pernicious forms for theory, empirical modelling, forecasting and policy. We discuss how they too can be handled, with the potential benefit of highlighting when variables are not related as assumed.

RELATED PAPERS

International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings

Carole Kelly

INOVTEK POLBENG

Sholihah Ayu Wulandari

The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation the Official Publication of the International Society For Heart Transplantation

Miralem Pasic

Technological and Economic Development of Economy

Denis Trček

Sumair Araujo

Value in Health

Ron Akehurst

Ciencia y enfermería

olivia sanhueza

Bangladesh Journal of Anatomy

Humaira Naushaba

Agung Agung

Jennifer Meza Infantes

Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies

Ibrahim Kizhisseri

Journal of Clinical Medicine

Alberto Berardi

European Journal of Cancer Prevention

Robert Tarone

Journal of Social and Economic Development

Kaliappa Kalirajan

LUIS REINALDO GAYTAN - MARTINEZ

Ashwil Klein

Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy

Catherine Fichten

Vladimir Vohralík

Australian Social Work

jaclyn thorburn

Interface - Comunicação, Saúde, Educação

Elaine Thumé

Environmental Entomology

Andrés Cortez

William Bourne

Lilia Hernández

Universal Journal of Educational Research

İhsan Katrancı

Michael Chrisofos

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- UK Universities

- Search by Curriculum

- Search by Location

Start typing and press Enter to search

Critical Thinking in the 21st Century

“To compete and win in the global economy, today’s students and tomorrow’s leaders need another set of knowledge and skills. These 21st Century skills include the ability to collaborate and communicate and analyze and address problems. And they need to rely on critical thinking and problem solving to create innovative solutions to the issues facing our world. Every child should have the opportunity to acquire and master these skills,” declared Michael Dell, the CEO of Dell Computers, Inc.

The 21st Century has brought with it a fast-paced, complex environment. In order to excel in this ever-changing world, young adults need to be capable of thinking critically to be creative, innovative and adaptable. Critical thinking – the ability to think clearly and rationally – allows one to properly understand and address issues effectively. This form of purposeful thinking is at the core of effective learning.

By thinking critically, one would be able to evaluate knowledge, clarify concepts, seek possibilities and alternatives, and solve problems using logic, resourcefulness and imagination. A critical thinker would be able to think broadly and set down the right path in facing today’s challenges at school and beyond.

However, this cognitive capability is not developed overnight. Thus, it is crucial that your child is given a proper environment in which they can flex their critical-thinking abilities, especially during their formative years. Shattuck-St. Mary’s School does just that right from the start. The school’s Early Childhood program uses a Reggio Emilia approach to learning. This is an innovative and inspiring approach that values the child as strong, capable and resilient, rich with wonder and knowledge. Students are enabled to think critically in order to understand their world and their place in it.

As they progress to higher levels of education, the students are given opportunities to become innovative, discerning and independent learners. By the time they reach high school, they will be immersed in the school’s unique ScholarShift® program that allows them to apply their learning in highly relevant, real-world contexts. With a strong framework in critical thinking, these students will be able to develop the necessary 21st Century skills that they will continue to use in college and life thereafter.

Shattuck-St. Mary’s School is a premier American boarding school with a 160-year legacy of educational excellence. The school is opening its first Southeast Asian campus in Forest City , Johor, in August. Registration for its upcoming Fall 2018 intake is now ongoing.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

You may also like

SJIIM’s Nicol Yong wins International Youth English Speaking Competition in China

Students from International School Fare Better in the Real World

NUMed Learning Under Lockdown

5 Qualities Universities Look for in Students

Students Take the Lead: Clinical Experience at NUMed

Providing an Exceptional Educational Experience

- No category

Trends-Networks-and-Critical-Thinking-in-the-21st-Century-Culture

Related documents

Add this document to collection(s)

You can add this document to your study collection(s)

Add this document to saved

You can add this document to your saved list

Suggest us how to improve StudyLib

(For complaints, use another form )

Input it if you want to receive answer

- Advanced search

- Course reserves

- Recent comments

- Most popular

Log in to your account

If you do not have a Google account, but do have a local account, you can still log in:

Trends, networks, and critical thinking in the 21st century culture / authors: Arleigh Ross D. Dela Cruz, PhD, Cecile C. FAdrigon, PhD cand., Napoleon M. Mabaquiao Jr., PhD ; project director: Ronaldo B. Mactal, PhD.

- Phoenix Publishing House [publisher. ]

- Fadrigon, Cecile C [author. ]

- Mabaquiao, Napoleon M., Jr [author. ]

- 9789710639434

- Social sciences

- 300 .P574 2018

- Holdings ( 1 )

- Title notes ( 6 )

- Comments ( 0 )

At head of title: K to 12 curriculum compliant --Cover

ICT enchanced --Cover

Includes references (pages 239-240)

"The chapters in the course book are divided into lessons which examine the nature of local, global, and planetary networks as emerging trends and analyzes the key issues within each level including the relationship that exists between and among the different entities involved in each network. The textbook also teaches students how to apply critical thinking and decision-making methods in understanding trends and networks. This textbook has three main objectives. First, it explains the connections that exist between networks and trends. Second, it discusses how critical thinking, strategic analysis, and intuitive thinking can help analyze emerging trends in the study of local., global, and planetary networks. And lastly, it teaches the students the necessary skills to propose possible interventions, alternative solutions, and new answers to the problems and concerns brought about by the emergence of trends. The book is divided into seven chapters." --From the Authors.

Text in English

There are no comments on this title.

- Add to your cart (remove)

- Save record BIBTEX Dublin Core MARCXML MARC (non-Unicode/MARC-8) MARC (Unicode/UTF-8) MARC (Unicode/UTF-8, Standard) MODS (XML) RIS

- More searches Search for this title in: Other Libraries (WorldCat) Other Databases (Google Scholar) Online Stores (Bookfinder.com) Open Library (openlibrary.org)

Exporting to Dublin Core...

Select the item(s) to search.

Hanapan ang Blog na Ito

A reflection on trends, networks and criticial thinking.

- Kunin ang link

- Iba Pang App

Mga Komento

Thank you it was so helpful ❤️

Mag-post ng isang Komento

Mga sikat na post sa blog na ito, pistang tomas: kultura't kabuhayan ng pamayanan, pagyamanin at pangalagaan.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

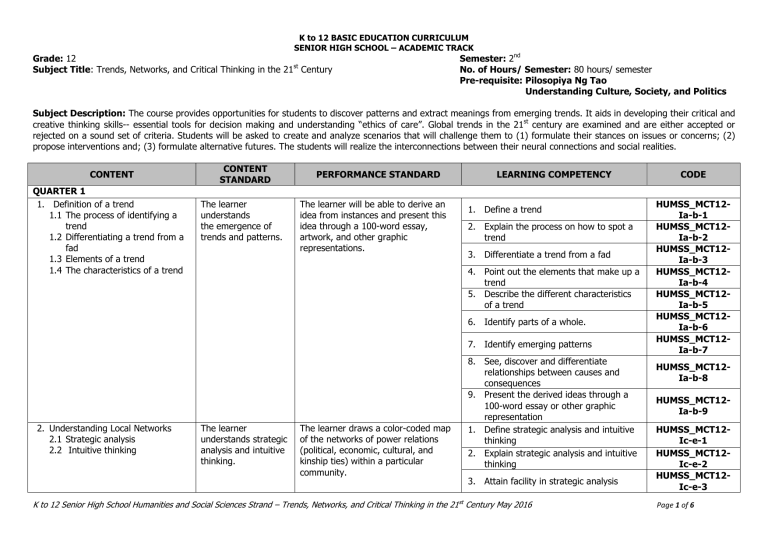

Subject Title: Trends, Networks, and Critical Thinking in the 21st Century No. of Hours/ Semester: 80 hours/ semester Pre-requisite: Pilosopiya Ng Tao Understanding Culture, Society, and Politics Subject Description: The course provides opportunities for students to discover patterns and extract meanings from emerging trends. It aids in ...

The aim of the present literature review is to provide a glimpse of how CT instruction has been conducted in 21 st-century research and practice and its potential pathways of development in the digital world.Critical thinking (CT) has become a crucial competence in 21 st-century society.Prior research and renowned experts have recommended explicit CT instruction to impact students' CT effectively.

The International Baccalaureate (IB) will be hosting its annual African Education Festival in Johannesburg, South Africa on 27 - 28 February 2020 under the theme of Leading and Learning in the 21st Century, with a special focus on "Inspire, Innovate, Integrate". Conrad Hughes will deliver a keynote on critical thinking in the 21st Century ...

Begin by asking students what they think culture means. They can discuss this in small groups or as a whole class. Create a Culture Thinking Map on chart/poster paper by writing culture in a circle in the middle. As students share their ideas with the class, draw lines coming out of the circle to record students' responses.

The author argues that, although both critical thinking and 21st-century skills are indeed necessary in a curriculum for a 21st-century education, they are not sufficient, even in combination. ... It can be understood as creative for the individual, if not original for the culture. For Dewey, effective learning through expressive or purposeful ...

How can we understand and respond to the complex and dynamic issues of the 21st century? This book explores the concepts and skills of trends, networks, and critical thinking in the context of culture, society, and technology. Learn how to analyze and evaluate information, communicate effectively, and apply ethical reasoning in various situations.