- Second Opinion

Cognitive Development in the Teen Years

What is cognitive development.

Cognitive development means the growth of a child’s ability to think and reason. This growth happens differently from ages 6 to 12, and from ages 12 to 18.

Children ages 6 to 12 years old develop the ability to think in concrete ways. These are called concrete operations. These things are called concrete because they’re done around objects and events. This includes knowing how to:

Combine (add)

Separate (subtract or divide)

Order (alphabetize and sort)

Transform objects and actions (change things, such as 5 pennies = 1 nickel)

Ages 12 to 18 is called adolescence. Kids and teens in this age group do more complex thinking. This type of thinking is also known as formal logical operations. This includes the ability to:

Do abstract thinking. This means thinking about possibilities.

Reason from known principles. This means forming own new ideas or questions.

Consider many points of view. This means to compare or debate ideas or opinions.

Think about the process of thinking. This means being aware of the act of thought processes.

How cognitive growth happens during the teen years

From ages 12 to 18, children grow in the way they think. They move from concrete thinking to formal logical operations. It’s important to note that:

Each child moves ahead at their own rate in their ability to think in more complex ways.

Each child develops their own view of the world.

Some children may be able to use logical operations in schoolwork long before they can use them for personal problems.

When emotional issues come up, they can cause problems with a child’s ability to think in complex ways.

The ability to consider possibilities and facts may affect decision-making. This can happen in either positive or negative ways.

Types of cognitive growth through the years

A child in early adolescence:

Uses more complex thinking focused on personal decision-making in school and at home

Begins to show use of formal logical operations in schoolwork

Begins to question authority and society's standards

Begins to form and speak his or her own thoughts and views on many topics. You may hear your child talk about which sports or groups he or she prefers, what kinds of personal appearance is attractive, and what parental rules should be changed.

A child in middle adolescence:

Has some experience in using more complex thinking processes

Expands thinking to include more philosophical and futuristic concerns

Often questions more extensively

Often analyzes more extensively

Thinks about and begins to form his or her own code of ethics (for example, What do I think is right?)

Thinks about different possibilities and begins to develop own identity (for example, Who am I? )

Thinks about and begins to systematically consider possible future goals (for example, What do I want? )

Thinks about and begins to make his or her own plans

Begins to think long-term

Uses systematic thinking and begins to influence relationships with others

A child in late adolescence:

Uses complex thinking to focus on less self-centered concepts and personal decision-making

Has increased thoughts about more global concepts, such as justice, history, politics, and patriotism

Often develops idealistic views on specific topics or concerns

May debate and develop intolerance of opposing views

Begins to focus thinking on making career decisions

Begins to focus thinking on their emerging role in adult society

How you can encourage healthy cognitive growth

To help encourage positive and healthy cognitive growth in your teen, you can:

Include him or her in discussions about a variety of topics, issues, and current events.

Encourage your child to share ideas and thoughts with you.

Encourage your teen to think independently and develop his or her own ideas.

Help your child in setting goals.

Challenge him or her to think about possibilities for the future.

Compliment and praise your teen for well-thought-out decisions.

Help him or her in re-evaluating poorly made decisions.

If you have concerns about your child's cognitive development, talk with your child's healthcare provider.

Related Links

- Brain and Behavior

- Child and Adolescent Mental Health

- Pediatric Cardiology

- Our Services

- Chiari Malformation Center at Stanford Medicine Children's Health

Related Topics

Adolescent Growth and Development

Cognitive Development in Adolescence

Growth and Development in Children with Congenital Heart Disease

Connect with us:

Download our App:

- Leadership Team

- Vision, Mission & Values

- The Stanford Advantage

- Government and Community Relations

- Get Involved

- Volunteer Services

- Auxiliaries & Affiliates

© 123 Stanford Medicine Children’s Health

Home — Essay Samples — Psychology — Cognitive Development — Cognitive Development in Adolescents and Young Adults

Cognitive Development in Adolescents and Young Adults

- Categories: Adolescence Cognitive Development

About this sample

Words: 652 |

Published: Aug 14, 2023

Words: 652 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Cognitive development in young adults .

- Are there any differences in the development of boys' and girls' brains? (n.d.). Retrieved from zerotothree.org: https://www.zerotothree.org/resources/1380-are-there-any-differences-in-the-development-of-boys-and-girls-brains

- Sanders, R. A. (2013, August). Adolescent Psychosocial, Social, and Cognitive Development. Retrieved from pedsinreview: https://pedsinreview.aappublications.org/content/34/8/354

- Why Are Teen Brains Designed for Risk-taking. (2015, June 09). Retrieved from psychologytoday.com: https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/the-wide-wide-world-psychology/201506/why-are-teen-brains-designed-risk-taking

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Psychology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 955 words

2 pages / 934 words

1 pages / 618 words

1 pages / 435 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Cognitive Development

Video games have long been a source of both enjoyment and controversy, particularly when it comes to their impact on children and young adults. While many adults argue that excessive gaming leads to increased violence and offers [...]

In conclusion, Piaget and Vygotsky offer contrasting perspectives on cognitive development. Piaget focused on the individual construction of knowledge, with cognitive development occurring in a series of universal stages. [...]

Bandura's social learning theory proposes that behavior change is achieved through observation, imitation, and modeling. The theory suggests that learning is influenced by role models, attitudes, and anticipated outcomes. It [...]

Early adulthood is a critical phase in the development of an individual's personality, with significant changes taking place during this period. Erikson's theory offers insights into this stage, particularly in terms of the [...]

Throughout this class I have learned how much of a role psychology actually play in our lives. We are taught that there can be many different ways that we interact with others as well as how others interact with myself. This [...]

Good Will Hunting is a film about the pronounced relationship between a therapist and janitor, Will Hunting. The film demonstrates egos and how ego can affect people in their daily lives. Will experienced a not ideal upbringing, [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

10.4 Cognition in Adolescence and Adulthood

Learning objectives.

- Describe adolescent egocentrism.

- Describe the limitations of adolescent thinking.

- Describe how differences between cross-sectional, longitudinal, and sequential research designed have contributed to our understanding of the development of intelligence in middle adulthood.

- Define crystallized and fluid intelligence.

- Explain how intelligence changes with age.

Cognition in Adolescence

Adolescence is a time of rapid cognitive development. Biological changes in brain structure and connectivity in the brain interact with increased experience, knowledge, and changing social demands to produce rapid cognitive growth. These changes generally begin at puberty or shortly thereafter, and some skills continue to develop as an adolescent ages. Development of executive functions, or cognitive skills that enable the control and coordination of thoughts and behavior, are generally associated with the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. The thoughts, ideas, and concepts developed at this period of life greatly influence one’s future life and play a major role in character and personality formation.

Improvements in basic thinking abilities generally occur in several areas during adolescence:

- Attention . Improvements are seen in selective attention (the process by which one focuses on one stimulus while tuning out another), as well as divided attention (the ability to pay attention to two or more stimuli at the same time).

- Memory . Improvements are seen in working memory and long-term memory.

- Processing speed. Adolescents think more quickly than children. Processing speed improves sharply between age five and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and then remains largely the same between late adolescence and adulthood.

Adolescent Egocentrism

Adolescents’ newfound meta-cognitive abilities also have an impact on their social cognition, as it results in increased introspection, self-consciousness, and intellectualization. Adolescents are much better able to understand that people do not have complete control over their mental activity. Being able to introspect may lead to forms of egocentrism, or self-focus, in adolescence. Adolescent egocentrism is a term that David Elkind used to describe the phenomenon of adolescents’ inability to distinguish between their perception of what others think about them and what people actually think in reality . Elkind’s theory on adolescent egocentrism is drawn from Piaget’s theory on cognitive developmental stages, which argues that formal operations enable adolescents to construct imaginary situations and abstract thinking.

Accordingly, adolescents are able to conceptualize their own thoughts and conceive of other people’s thoughts. However, Elkind pointed out that adolescents tend to focus mostly on their own perceptions, especially on their behaviors and appearance, because of the “physiological metamorphosis” they experience during this period. This leads to adolescents’ belief that other people are as attentive to their behaviors and appearance as they are themselves (Elkind, 1967; Schwartz et al.., 2008). According to Elkind, adolescent egocentrism results in two distinct problems in thinking: the imaginary audience and the personal fable. These likely peak at age fifteen, along with self-consciousness in general.

Imaginary audience is a term that Elkind used to describe the phenomenon that an adolescent anticipates the reactions of other people to him/herself in actual or impending social situations . Elkind argued that this kind of anticipation could be explained by the adolescent’s conviction that others are as admiring or as critical of them as they are of themselves. As a result, an audience is created, as the adolescent believes that he or she will be the focus of attention. However, more often than not the audience is imaginary because in actual social situations individuals are not usually the sole focus of public attention. Elkind believed that the construction of imaginary audiences would partially account for a wide variety of typical adolescent behaviors and experiences; and imaginary audiences played a role in the self-consciousness that emerges in early adolescence. However, since the audience is usually the adolescent’s own construction, it is privy to his or her own knowledge of him/herself. According to Elkind, the notion of imaginary audience helps to explain why adolescents usually seek privacy and feel reluctant to reveal themselves–it is a reaction to the feeling that one is always on stage and constantly under the critical scrutiny of others.

Elkind also suggested that adolescents have another complex set of beliefs: They are convinced that their own feelings are unique and they are special and immortal. Personal fable is the term Elkind used to describe this notion, which is the complement of the construction of an imaginary audience. Since an adolescent usually fails to differentiate their own perceptions and those of others, they tend to believe that they are of importance to so many people (the imaginary audiences) that they come to regard their feelings as something special and unique. They may feel that they are the only ones who have experienced strong and diverse emotions, and therefore others could never understand how they feel. This uniqueness in one’s emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent’s belief of invincibility, especially to death.

This adolescent belief in personal uniqueness and invincibility becomes an illusion that they can be above some of the rules, constraints, and laws that apply to other people; even consequences such as death (called the invincibility fable ). This belief that one is invincible removes any impulse to control one’s behavior (Lin, 2016). Therefore, some adolescents will engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences.

Intuitive and Analytic Thinking

Piaget emphasized the sequence of cognitive developments that unfold in four stages. Others suggest that thinking does not develop in sequence, but instead, that advanced logic in adolescence may be influenced by intuition. Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the dual-process model ; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Kuhn, 2013.)

Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional . In contrast , analytic thought is d eliberate, conscious, and rational (logical) . Although these systems interact, they are distinguishable (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier, quicker, and more commonly used in everyday life. The discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex, as discussed previously, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults.

As adolescents develop, they gain in logic/analytic thinking ability but may sometimes regress, with social context, education, and experiences becoming major influences. Simply put, being “smarter” as measured by an intelligence test does not advance or anchor cognition as much as having more experience, in school and in life (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014).

Risk-taking

Because most injuries sustained by adolescents are related to risky behavior (alcohol consumption and drug use, reckless or distracted driving, and unprotected sex), a great deal of research has been conducted to examine the cognitive and emotional processes underlying adolescent risk-taking. In addressing this issue, it is important to distinguish three facets of these questions: (1) whether adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behaviors (prevalence), (2) whether they make risk-related decisions similarly or differently than adults (cognitive processing perspective), or (3) whether they use the same processes but weigh facets differently and thus arrive at different conclusions. Behavioral decision-making theory proposes that adolescents and adults both weigh the potential rewards and consequences of an action. However, research has shown that adolescents seem to give more weight to rewards, particularly social rewards, than do adults. Adolescents value social warmth and friendship, and their hormones and brains are more attuned to those values than to a consideration of long-term consequences (Crone & Dahl, 2012).

Some have argued that there may be evolutionary benefits to an increased propensity for risk-taking in adolescence. For example, without a willingness to take risks, teenagers would not have the motivation or confidence necessary to leave their family of origin. In addition, from a population perspective, is an advantage to having a group of individuals willing to take more risks and try new methods, counterbalancing the more conservative elements typical of the received knowledge held by older adults.

Cognitive Development in Early Adulthood

Emerging adulthood brings with it the consolidation of formal operational thought, and the continued integration of the parts of the brain that serve emotion, social processes, and planning and problem solving. As a result, rash decisions and risky behavior decrease rapidly across early adulthood. Increases in epistemic cognition are also seen, as young adults’ meta-cognition, or thinking about thinking, continues to grow, especially young adults who continue with their schooling.

Perry’s Scheme

One of the first theories of cognitive development in early adulthood originated with William Perry (1970), who studied undergraduate students at Harvard University. Perry noted that over the course of students’ college years, cognition tended to shift from dualism (absolute, black and white, right and wrong type of thinking) to multiplicity (recognizing that some problems are solvable and some answers are not yet known) to relativism (understanding the importance of the specific context of knowledge—it’s all relative to other factors). Similar to Piaget’s formal operational thinking in adolescence, this change in thinking in early adulthood is affected by educational experiences.

Table 9.2 Stages of Perry’s Scheme

adapted from Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning

Some researchers argue that a qualitative shift in cognitive development takes place for some emerging adults during their mid to late twenties. As evidence, they point to studies documenting continued integration and focalization of brain functioning, and studies suggesting that this developmental period often represents a turning point, when young adults engaging in risky behaviors (e.g., gang involvement, substance abuse) or an unfocused lifestyle (e.g., drifting from job to job or relationship to relationship) seem to “wake up” and take ownership for their own development. It is a common point for young adults to make decisions about completing or returning to school, and making and following through on decisions about vocation, relationships, living arrangements, and lifestyle. Many young adults can actually remember these turning points as a moment when they could suddenly “see” where they were headed (i.e., the likely outcomes of their risky behaviors or apathy) and actively decided to take a more self-determined pathway.

Cognition in Middle Adulthood

The brain at midlife has been shown to not only maintain many of the abilities of young adults, but also gain new ones. Some individuals in middle age actually have improved cognitive functioning (Phillips, 2011). The brain continues to demonstrate plasticity and rewires itself in middle age based on experiences. Research has demonstrated that older adults use more of their brains than younger adults. In fact, older adults who perform the best on tasks are more likely to demonstrate bilateralization than those who perform worst. Additionally, the amount of white matter in the brain, which is responsible for forming connections among neurons, increases into the 50s before it declines.

Emotionally, the middle-aged brain is calmer, less neurotic, more capable of managing emotions, and better able to negotiate social situations (Phillips, 2011). Older adults tend to focus more on positive information and less on negative information than do younger adults. In fact, they also remember positive images better than those younger. Additionally, the older adult’s amygdala responds less to negative stimuli. Lastly, adults in middle adulthood make better financial decisions, a capacity which seems to peak at age 53, and show better economic understanding. Although greater cognitive variability occurs among middle aged adults when compared to those both younger and older, those in midlife who experience cognitive improvements tend to be more physically, cognitively, and socially active.

Crystalized versus Fluid Intelligence

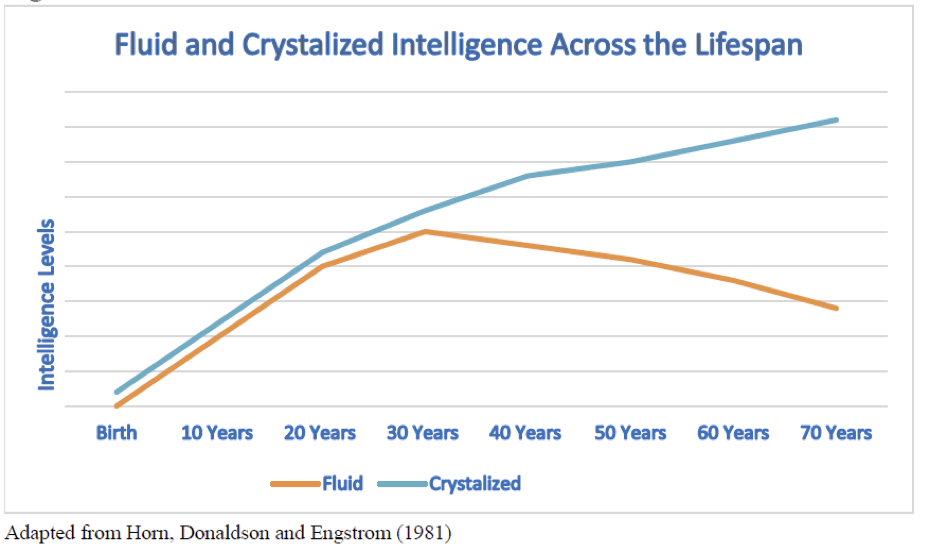

Intelligence is influenced by heredity, culture, social contexts, personal choices, and certainly age. One distinction in specific intelligences noted in adulthood, is between fluid intelligence , which refers to the capacity to learn new ways of solving problems and performing activities quickly and abstractly , and crystallized intelligence , which refers to the accumulated knowledge of the world we have acquired throughout our lives (Salthouse, 2004). These intelligences are distinct, and show different developmental pathways as pictured in Figure 10.22. Fluid intelligence tends to decrease with age (staring in the late 20s to early 30s), whereas crystallized intelligence generally increases all across adulthood (Horn et al., 1981; Salthouse, 2004).

Fluid intelligence, sometimes called the mechanics of intelligence, tends to rely on perceptual speed of processing, and perceptual speed is one of the primary capacities that shows age-graded declines starting in early adulthood, as seen not only in cognitive tasks but also in athletic performance and other tasks that require speed. In contrast, research demonstrates that crystallized intelligence, also called the pragmatics of intelligence, continues to grow all during adulthood, as older adults acquire additional semantic knowledge, vocabulary, and language. As a result, adults generally outperform younger people on tasks where this information is useful, such as measures of history, geography, and even on crossword puzzles (Salthouse, 2004). It is this superior knowledge, combined with a slower and more complete processing style, along with a more sophisticated understanding of the workings of the world around them, that gives older adults the advantage of “wisdom” over the advantages of fluid intelligence which favor the young (Baltes et al., 1999; Scheibe et al., 2009).

These differential changes in crystallized versus fluid intelligence help explain why older adults do not necessarily show poorer performance on tasks that also require experience (i.e., crystallized intelligence), although they show poorer memory overall. A young chess player may think more quickly, for instance, but a more experienced chess player has more knowledge to draw upon.

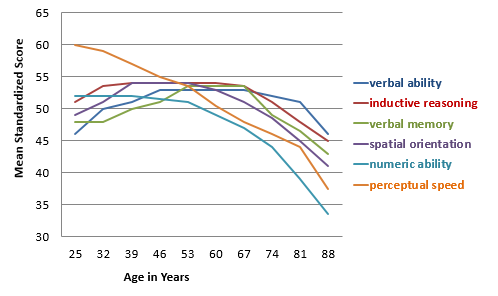

Seattle Longitudinal Study

The Seattle Longitudinal Study has tracked the cognitive abilities of adults since 1956. Every seven years the current participants are evaluated, and new individuals are also added. Approximately 6000 people have participated thus far, and 26 people from the original group are still in the study today. Current results demonstrate that middle-aged adults perform better on four out of six cognitive tasks than those same individuals did when they were young adults. Verbal memory, spatial skills, inductive reasoning (generalizing from particular examples), and vocabulary increase with age until one’s 70s (Schaie, 2005; Willis & Shaie, 1999). In contrast, perceptual speed declines starting in early adulthood, and numerical computation shows declines starting in middle and late adulthood (see Figure 10.23).

Cognitive skills in the aging brain have been studied extensively in pilots, and similar to the Seattle Longitudinal Study results, older pilots show declines in processing speed and memory capacity, but their overall performance seems to remain intact. According to Phillips (2011) researchers tested pilots age 40 to 69 as they performed on flight simulators. Older pilots took longer to learn to use the simulators but subsequently performed better than younger pilots at avoiding collisions.

Tacit knowledge is knowledge that is pragmatic or practical and learned through experience rather than explicitly taught, and it also increases with age (Hedlund et al., 2002). Tacit knowledge might be thought of as “know-how” or “professional instinct.” It is referred to as tacit because it cannot be codified or written down. It does not involve academic knowledge, rather it involves being able to use skills and to problem-solve in practical ways. Tacit knowledge can be seen clearly in the workplace and underlies the steady improvements in job performance documented across age and experience, as seen for example, in the performance of both white and blue collar workers, such as carpenters, chefs, and hair dressers.

Cognition in Late Adulthood

Changes in sensory functioning and speed of processing information in late adulthood often translate into changes in attention (Jefferies et al., 2015). Research has shown that older adults are less able to selectively focus on information while ignoring distractors (Jefferies et al., 2015; Wascher et al., 2012), although Jefferies and her colleagues found that when given double time, older adults could perform at the same level as young adults. Other studies have also found that older adults have greater difficulty shifting their attention between objects or locations (Tales et al., 2002).

Consider the implication of these attentional changes for older adults. How does maintenance or loss of cognitive ability affect older adults’ everyday lives? Researchers have studied cognition in the context of several different everyday activities. One example is driving. Although older adults often have more years of driving experience, cognitive declines related to reaction time or attentional processes may pose limitations under certain circumstances (Park & Gutchess, 2000). In contrast, research on interpersonal problem solving suggests that older adults use more effective strategies than younger adults to navigate through social and emotional problems (Blanchard-Fields, 2007). In the context of work, researchers rarely find that older individuals perform more poorly on the job (Park & Gutchess, 2000). Similar to everyday problem solving, older workers may develop more efficient strategies and rely on expertise to compensate for cognitive declines.

Problem Solving

Declines with age are found on problem-solving tasks that require processing non-meaningful information quickly– a kind of task that might be part of a laboratory experiment on mental processes. However, many real-life challenges facing older adults do not rely on speed of processing or making choices on one’s own. Older adults resolve everyday problems by relying on input from others, such as family and friends. They are also less likely than younger adults to delay making decisions on important matters, such as medical care (Strough et al., 2003; Meegan & Berg, 2002).

What might explain these deficits as we age?

The processing speed theory , proposed by Salthouse (1996, 2004), suggests that as the nervous system slows with advanced age our ability to process information declines . This slowing of processing speed may explain age differences on a variety of cognitive tasks. For instance, as we age, working memory becomes less efficient (Craik & Bialystok, 2006). Older adults also need longer time to complete mental tasks or make decisions. Yet, when given sufficient time (to compensate for declines in speed), older adults perform as competently as do young adults (Salthouse, 1996). Thus, when speed is not imperative to the task, healthy older adults generally do not show cognitive declines.

In contrast, inhibition theory argues that older adults have difficulty with tasks that require inhibitory functioning, or the ability to focus on certain information while suppressing attention to less pertinent information (Hasher & Zacks, 1988). Evidence comes from directed forgetting research. In directed forgetting people are asked to forget or ignore some information, but not other information. For example, you might be asked to memorize a list of words but are then told that the researcher made a mistake and gave you the wrong list and asks you to “forget” this list. You are then given a second list to memorize. While most people do well at forgetting the first list, older adults are more likely to recall more words from the “directed-to-forget” list than are younger adults (Andrés et al., 2004).

Aging stereotypes exaggerate cognitive losses

While there are information processing losses in late adulthood, many argue that research exaggerates normative losses in cognitive functioning during old age (Garrett, 2015). One explanation is that the type of tasks that people are tested on tend to be meaningless. For example, older individuals are not motivated to remember a random list of words in a study, but they are motivated for more meaningful material related to their life, and consequently perform better on those tests. Another reason is that researchers often estimate age declines from age differences found in cross-sectional studies. However, when age comparisons are conducted longitudinally (thus removing cohort differences from age comparisons), the extent of loss is much smaller (Schaie, 1994).

A third possibility is that losses may be due to the disuse of various skills. When older adults are given structured opportunities to practice skills, they perform as well as they had previously. Although diminished speed is especially noteworthy during late adulthood, Schaie (1994) found that when the effects of speed are statistically removed, fewer and smaller declines are found in other aspects of an individual’s cognitive performance. In fact, Salthouse and Babcock (1991) demonstrated that processing speed accounted for all but 1% of age-related differences in working memory when testing individuals from ages 18 to 82. Finally, it is well established that hearing and vision decline as we age. Longitudinal research has found that deficits in sensory functioning explain age differences in a variety of cognitive abilities (Baltes & Lindenberger, 1997). Not surprisingly, more years of education, higher income, and better health care (which go together) are associated with higher levels of cognitive performance and slower cognitive decline (Zahodne et al., 2015).

Watch this video from SciShow Psych to learn about ways to keep the mind young and active.

You can view the transcript for “The Best Ways to Keep Your Mind Young” here (opens in new window) .

Intelligence and Wisdom

When looking at scores on traditional intelligence tests, tasks measuring verbal skills show minimal or no age-related declines, while scores on performance tests, which measure solving problems quickly, decline with age (Botwinick, 1984). This profile mirrors crystalized and fluid intelligence. Baltes (1993) introduced two additional types of intelligence to reflect cognitive changes in aging. Pragmatics of intelligence are cultural exposure to facts and procedures that are maintained as one ages and are similar to crystalized intelligence. Mechanics of intelligence are dependent on brain functioning and decline with age, similar to fluid intelligence. Baltes indicated that pragmatics of intelligence show little decline and typically increase with age whereas mechanics decline steadily, staring at a relatively young age. Additionally, pragmatics of intelligence may compensate for the declines that occur with mechanics of intelligence. In summary, global cognitive declines are not typical as one ages, and individuals typically compensate for some cognitive declines, especially processing speed.

Wisdom has been defined as “ expert knowledge in the fundamental pragmatics of life that permits exceptional insight, judgment and advice about complex and uncertain matters” ( Baltes & Smith, 1990). A wise person is insightful and has knowledge that can be used to overcome obstacles in living. Does aging bring wisdom? While living longer brings experience, it does not always bring wisdom. Paul Baltes and his colleagues (Baltes & Kunzmann, 2004; Baltes & Staudinger, 2000) suggest that wisdom is rare. In addition, the emergence of wisdom can be seen in late adolescence and young adulthood, with there being few gains in wisdom over the course of adulthood (Staudinger & Gluck, 2011). This would suggest that factors other than age are stronger determinants of wisdom. Occupations and experiences that emphasize others rather than self, along with personality characteristics, such as openness to experience and generativity, are more likely to provide the building blocks of wisdom (Baltes & Kunzmann, 2004). Age combined with a certain types of experience and/or personality brings wisdom.

Andrés, P., Van der Linden, M., & Parmentier, F. B. R. (2004). Directed forgetting in working memory: Age-related differences. Memory, 12 , 248-256.

Baltes, P. B. & Lindenberger, U. (1997). Emergence of powerful connection between sensory and cognitive functions across the adult life span: A new window to the study of cognitive aging? Psychology and Aging, 12 , 12–21.

Baltes, P. B., Staudinger, U. M., & Lindenberger, U. (1999). Lifespan Psychology: Theory and Application to Intellectual Functioning. Annual Review of Psychology, 50 , 471-507.

Blanchard-Fields, F. (2007). Everyday problem solving and emotion: An adult development perspective. Current Directions in Psychoogical Science, 16 , 26–31

Craik, F. I., & Bialystok, E. (2006). Cognition through the lifespan: mechanisms of change. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 10 , 131–138.

Crone, E. A., & Dahl, R. E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social–affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature reviews neuroscience , 13 (9), 636-650.

Elkind, D. (1967). Egocentrism in adolescence. Child Development, 38, 1025-1034.

Garrett, B. (2015). Brain and behavior ( 4th ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hasher, L. & Zacks, R. T. (1988). Working memory, comprehension, and aging: A review and a new view. In G.H. Bower (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Motivation , (Vol. 22, pp. 193–225). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Hedlund, J., Antonakis, J., & Sternberg, R. J. (2002). Tacit knowledge and practical intelligence: Understanding the lessons of experience . Retrieved from http://www.au.af.mil/au/awc/awcgate/army/ari_tacit_knowledge.pdf

Horn, J. L., Donaldson, G., & Engstrom, R. (1981). Apprehension, memory, and fluid intelligence decline in adulthood. Research on Aging, 3(1), 33-84.

Jefferies, L. N., Roggeveen, A. B., Ennis, J. T., Bennett, P. J., Sekuler, A. B., & Dilollo, V. (2015). On the time course of attentional focusing in older adults. Psychological Research, 79 , 28-41.

Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In. P.D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology. (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York NY: Oxford University Press.

Klaczynski, P. A., & Felmban, W. S. (2014). Heuristics and biases during adolescence: developmental reversals and individual differences.

Lin, P. (2016). Risky behaviors: Integrating adolescent egocentrism with the theory of planned behavior. Review of General Psychology , 20 (4), 392-398.

Meegan, S. P., & Berg, C. A. (2002). Contexts, functions, forms, and processes of collaborative everyday problem solving in older adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development , 26 (1), 6-15. doi: 10.1080/01650250143000283

Park, D. C. & Gutchess, A. H. (2000). Cognitive aging and everyday life. In D.C. Park & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Cognitive Aging: A Primer (pp. 217–232). New York: Psychology Press.

Perry, W.G., Jr. (1970). Forms of ethical and intellectual development in the college years: A scheme. New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Phillips, M. L. (2011). The mind at midlife. American Psychological Association . Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/monitor/2011/04/mind-midlife.aspx

Salthouse, T. A. (1984). Effects of age and skill in typing. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113 , 345.

Salthouse, T. A. (1996). The processing-speed theory of adult age differences in cognition. Psychological Review, 103 , 403-428.

Salthouse, T. A. (2004). What and when of cognitive aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13 , 140–144.

Salthouse, T. A., & Babcock, R. L. (1991). Decomposing adult age differences in working memory. Developmental Psychology, 27 , 763-776.

Schaie, K. W. (1994). The course of adult intellectual development. American Psychologist, 49, 304-311.

Schaie, K. W. (2005). Developmental influences on adult intelligence the Seattle longitudinal study. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Scheibe, S., Kunzmann, U. & Baltes, P. B. (2009). New territories of Positive Lifespan Development: Wisdom and Life Longings. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford handbook of Positive Psychology (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Schwartz, P. D., Maynard, A. M., & Uzelac, S. M. (2008). Adolescent egocentrism: A contemporary view. Adolescence, 43, 441- 447.

Strough, J., Hicks, P. J., Swenson, L. M., Cheng, S., & Barnes, K. A. (2003). Collaborative everyday problem solving: Interpersonal relationships and problem dimensions. International Journal of Aging and Human Development , 56 , 43- 66.

Tales, A., Muir, J. L., Bayer, A., & Snowden, R. J. (2002). Spatial shifts in visual attention in normal aging and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neuropsychologia, 40, 2000-2012.

Wasscher, E., Schneider, D., Hoffman, S., Beste, C., & Sänger, J. (2012). When compensation fails: Attentional deficits in healthy ageing caused by visual distraction. Neuropsychologia, 50 , 3185-31-92.

Willis, S. L., & Schaie, K. W. (1999). Intellectual functioning in midlife. In S. L. Willis & J. D. Reid (Eds.), Life in the Middle: Psychological and Social Development in Middle Age (pp. 233-247). San Diego: Academic.

Zahodne, L. B., Stern, Y., & Manly, J. (2015). Differing effects of education on cognitive decline in diverse elders with low versus high educational attainment. Neuropsychology, 29 (4), 649-657.

CC Licensed Content

“Cognitive Development During Adolescence” by Lumen Learning is licensed under a CC BY: Attribution .

“Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective, Second Edition” by Martha Lally and Suzanne Valentine-French is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0 /modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

Lifespan Development by Lumen Learning is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License /modified and adapted by Ellen Skinner & Dan Grimes, Portland State University

“Puberty & Cognition” by Ellen Skinner, Dan Grimes & Brandy Brennan, Portland State University and are licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA-4.0

Media Attributions

- adolescent boys. Authored by : An Min. Provided by : Pxhere. Located at : https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1515959 . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Smartphone. Photo by Roman Pohorecki from Pexels: https://www.pexels.com/photo/person-sitting-inside-car-with-black-android-smartphone-turned-on-230554/

- The Best Ways to Keep Your Mind Young. Provided by : SciShow Psych. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5DH9lAqNTG0 . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- 512px-Happy_Old_Man © Marg is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

Lifespan Human Development: A Topical Approach Copyright © by Meredith Palm is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7.6: Introduction to Cognitive Development in Adolescence

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 60485

- Lumen Learning

What you’ll learn to do: describe changes in cognitive development and moral reasoning during adolescence

Here we learn about adolescent cognitive development. In adolescence, changes in the brain interact with experience, knowledge, and social demands and produce rapid cognitive growth. The changes in how adolescents think, reason, and understand can be even more dramatic than their obvious physical changes. This stage of cognitive development, termed by Piaget as the formal operational stage, marks a movement from the ability to think and reason logically only about concrete, visible events to an ability to also think logically about abstract concepts.

Adolescents are now able to analyze situations logically in terms of cause and effect and to entertain hypothetical situations and entertain what-if possibilities about the world. This higher-level thinking allows them to think about the future, evaluate alternatives, and set personal goals. Although there are marked individual differences in cognitive development among teens, these new capacities allow adolescents to engage in the kind of introspection and mature decision making that was previously beyond their cognitive capacity.

Contributors and Attributions

- Introduction to Cognitive Development in Adolescence. Authored by : Tera Jones for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- In Their Shoes. Authored by : Louis Briscese. Provided by : U.S. Department of Defense. Located at : https://dod.defense.gov/Photos/Photo-Gallery/igphoto/2001716400/ . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

Module 7: Adolescence

Cognitive development during adolescence, learning outcomes.

- Explain Piaget’s theory on formal operational thought

- Describe cognitive abilities and changes during adolescence

Figure 1. Adolescents practice their developing abstract and hypothetical thinking skills, coming up with alternative interpretations of information.

Adolescence is a time of rapid cognitive development. Biological changes in brain structure and connectivity in the brain interact with increased experience, knowledge, and changing social demands to produce rapid cognitive growth. These changes generally begin at puberty or shortly thereafter, and some skills continue to develop as an adolescent ages. Development of executive functions, or cognitive skills that enable the control and coordination of thoughts and behavior, are generally associated with the prefrontal cortex area of the brain. The thoughts, ideas, and concepts developed at this period of life greatly influence one’s future life and play a major role in character and personality formation.

Perspectives and Advancements in Adolescent Thinking

There are two perspectives on adolescent thinking: constructivist and information-processing. The constructivist perspective , based on the work of Piaget, takes a quantitative, stage-theory approach. This view hypothesizes that adolescents’ cognitive improvement is relatively sudden and drastic. The information-processing perspective derives from the study of artificial intelligence and explains cognitive development in terms of the growth of specific components of the overall process of thinking.

Improvements in basic thinking abilities generally occur in five areas during adolescence:

- Attention . Improvements are seen in selective attention (the process by which one focuses on one stimulus while tuning out another), as well as divided attention (the ability to pay attention to two or more stimuli at the same time).

- Memory . Improvements are seen in working memory and long-term memory.

- Processing Speed. Adolescents think more quickly than children. Processing speed improves sharply between age five and middle adolescence, levels off around age 15, and does not appear to change between late adolescence and adulthood.

- Organization . Adolescents are more aware of their own thought processes and can use mnemonic devices and other strategies to think and remember information more efficiently.

- Metacognition . Adolescents can think about thinking itself. This often involves monitoring one’s own cognitive activity during the thinking process. Metacognition provides the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action, and provide alternative explanations of events.

Formal Operational Thought

In the last of the Piagetian stages, a child becomes able to reason not only about tangible objects and events, but also about hypothetical or abstract ones. Hence it has the name formal operational stage—the period when the individual can “operate” on “forms” or representations. This allows an individual to think and reason with a wider perspective. This stage of cognitive development, termed by Piaget as formal operational thought , marks a movement from an ability to think and reason from concrete visible events to an ability to think hypothetically and entertain what-if possibilities about the world. An individual can solve problems through abstract concepts and utilize hypothetical and deductive reasoning. Adolescents use trial and error to solve problems, and the ability to systematically solve a problem in a logical and methodical way emerges.

This video explains some of the cognitive development consistent with formal operational thought.

You can view the transcript for “Formal operational stage – Intro to Psychology” here (opens in new window) .

Formal Operational Thinking in the Classroom

School is a main contributor in guiding students towards formal operational thought. With students at this level, the teacher can pose hypothetical (or contrary-to-fact) problems: “What if the world had never discovered oil?” or “What if the first European explorers had settled first in California instead of on the East Coast of the United States?” To answer such questions, students must use hypothetical reasoning , meaning that they must manipulate ideas that vary in several ways at once, and do so entirely in their minds.

The hypothetical reasoning that concerned Piaget primarily involved scientific problems. His studies of formal operational thinking therefore often look like problems that middle or high school teachers pose in science classes. In one problem, for example, a young person is presented with a simple pendulum, to which different amounts of weight can be hung (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958). The experimenter asks: “What determines how fast the pendulum swings: the length of the string holding it, the weight attached to it, or the distance that it is pulled to the side?” The young person is not allowed to solve this problem by trial-and-error with the materials themselves, but must reason a way to the solution mentally. To do so systematically, they must imagine varying each factor separately, while also imagining the other factors that are held constant. This kind of thinking requires facility at manipulating mental representations of the relevant objects and actions—precisely the skill that defines formal operations.

As you might suspect, students with an ability to think hypothetically have an advantage in many kinds of school work: by definition, they require relatively few “props” to solve problems. In this sense they can in principle be more self-directed than students who rely only on concrete operations—certainly a desirable quality in the opinion of most teachers. Note, though, that formal operational thinking is desirable but not sufficient for school success, and that it is far from being the only way that students achieve educational success. Formal thinking skills do not insure that a student is motivated or well-behaved, for example, nor does it guarantee other desirable skills. The fourth stage in Piaget’s theory is really about a particular kind of formal thinking, the kind needed to solve scientific problems and devise scientific experiments. Since many people do not normally deal with such problems in the normal course of their lives, it should be no surprise that research finds that many people never achieve or use formal thinking fully or consistently, or that they use it only in selected areas with which they are very familiar (Case & Okomato, 1996). For teachers, the limitations of Piaget’s ideas suggest a need for additional theories about development—ones that focus more directly on the social and interpersonal issues of childhood and adolescence.

Hypothetical and abstract thinking

One of the major premises of formal operational thought is the capacity to think of possibility, not just reality. Adolescents’ thinking is less bound to concrete events than that of children; they can contemplate possibilities outside the realm of what currently exists. One manifestation of the adolescent’s increased facility with thinking about possibilities is the improvement of skill in deductive reasoning (also called top-down reasoning), which leads to the development of hypothetical thinking . This provides the ability to plan ahead, see the future consequences of an action and to provide alternative explanations of events. It also makes adolescents more skilled debaters, as they can reason against a friend’s or parent’s assumptions. Adolescents also develop a more sophisticated understanding of probability.

This appearance of more systematic, abstract thinking allows adolescents to comprehend the sorts of higher-order abstract logic inherent in puns, proverbs, metaphors, and analogies. Their increased facility permits them to appreciate the ways in which language can be used to convey multiple messages, such as satire, metaphor, and sarcasm. (Children younger than age nine often cannot comprehend sarcasm at all). This also permits the application of advanced reasoning and logical processes to social and ideological matters such as interpersonal relationships, politics, philosophy, religion, morality, friendship, faith, fairness, and honesty.

Metacognition

Metacognition refers to “thinking about thinking.” It is relevant in social cognition as it results in increased introspection, self-consciousness, and intellectualization. Adolescents are much better able to understand that people do not have complete control over their mental activity. Being able to introspect may lead to forms of egocentrism, or self-focus, in adolescence. Adolescent egocentrism is a term that David Elkind used to describe the phenomenon of adolescents’ inability to distinguish between their perception of what others think about them and what people actually think in reality. Elkind’s theory on adolescent egocentrism is drawn from Piaget’s theory on cognitive developmental stages, which argues that formal operations enable adolescents to construct imaginary situations and abstract thinking.

Accordingly, adolescents are able to conceptualize their own thoughts and conceive of other people’s thoughts. However, Elkind pointed out that adolescents tend to focus mostly on their own perceptions, especially on their behaviors and appearance, because of the “physiological metamorphosis” they experience during this period. This leads to adolescents’ belief that other people are as attentive to their behaviors and appearance as they are of themselves. According to Elkind, adolescent egocentrism results in two distinct problems in thinking: the imaginary audience and the personal fable . These likely peak at age fifteen, along with self-consciousness in general.

Imaginary audience is a term that Elkind used to describe the phenomenon that an adolescent anticipates the reactions of other people to them in actual or impending social situations. Elkind argued that this kind of anticipation could be explained by the adolescent’s preoccupation that others are as admiring or as critical of them as they are of themselves. As a result, an audience is created, as the adolescent believes that they will be the focus of attention.

However, more often than not the audience is imaginary because in actual social situations individuals are not usually the sole focus of public attention. Elkind believed that the construction of imaginary audiences would partially account for a wide variety of typical adolescent behaviors and experiences; and imaginary audiences played a role in the self-consciousness that emerges in early adolescence. However, since the audience is usually the adolescent’s own construction, it is privy to their own knowledge of themselves. According to Elkind, the notion of imaginary audience helps to explain why adolescents usually seek privacy and feel reluctant to reveal themselves–it is a reaction to the feeling that one is always on stage and constantly under the critical scrutiny of others.

Elkind also addressed that adolescents have a complex set of beliefs that their own feelings are unique and they are special and immortal. Personal fable is the term Elkind created to describe this notion, which is the complement of the construction of imaginary audience. Since an adolescent usually fails to differentiate their own perceptions and those of others, they tend to believe that they are of importance to so many people (the imaginary audiences) that they come to regard their feelings as something special and unique. They may feel that only they have experienced strong and diverse emotions, and therefore others could never understand how they feel. This uniqueness in one’s emotional experiences reinforces the adolescent’s belief of invincibility, especially to death.

This adolescent belief in personal uniqueness and invincibility becomes an illusion that they can be above some of the rules, disciplines and laws that apply to other people; even consequences such as death (called the invincibility fable ) . This belief that one is invincible removes any impulse to control one’s behavior (Lin, 2016). [1] Therefore, adolescents will engage in risky behaviors, such as drinking and driving or unprotected sex, and feel they will not suffer any negative consequences.

Intuitive and Analytic Thinking

Piaget emphasized the sequence of thought throughout four stages. Others suggest that thinking does not develop in sequence, but instead, that advanced logic in adolescence may be influenced by intuition. Cognitive psychologists often refer to intuitive and analytic thought as the dual-process model ; the notion that humans have two distinct networks for processing information (Kuhn, 2013.) [2] Intuitive thought is automatic, unconscious, and fast, and it is more experiential and emotional.

In contrast, a nalytic thought is deliberate, conscious, and rational (logical). While these systems interact, they are distinct (Kuhn, 2013). Intuitive thought is easier, quicker, and more commonly used in everyday life. As discussed in the adolescent brain development section earlier in this module, the discrepancy between the maturation of the limbic system and the prefrontal cortex, may make teens more prone to emotional intuitive thinking than adults. As adolescents develop, they gain in logic/analytic thinking ability and sometimes regress, with social context, education, and experiences becoming major influences. Simply put, being “smarter” as measured by an intelligence test does not advance cognition as much as having more experience, in school and in life (Klaczynski & Felmban, 2014). [3]

Risk-taking

Because most injuries sustained by adolescents are related to risky behavior (alcohol consumption and drug use, reckless or distracted driving, and unprotected sex), a great deal of research has been done on the cognitive and emotional processes underlying adolescent risk-taking. In addressing this question, it is important to distinguish whether adolescents are more likely to engage in risky behaviors (prevalence), whether they make risk-related decisions similarly or differently than adults (cognitive processing perspective), or whether they use the same processes but value different things and thus arrive at different conclusions. The behavioral decision-making theory proposes that adolescents and adults both weigh the potential rewards and consequences of an action. However, research has shown that adolescents seem to give more weight to rewards, particularly social rewards, than do adults. Adolescents value social warmth and friendship, and their hormones and brains are more attuned to those values than to long-term consequences (Crone & Dahl, 2012). [4]

Figure 2 . Teenage thinking is characterized by the ability to reason logically and solve hypothetical problems such as how to design, plan, and build a structure. (credit: U.S. Army RDECOM)

Some have argued that there may be evolutionary benefits to an increased propensity for risk-taking in adolescence. For example, without a willingness to take risks, teenagers would not have the motivation or confidence necessary to leave their family of origin. In addition, from a population perspective, there is an advantage to having a group of individuals willing to take more risks and try new methods, counterbalancing the more conservative elements more typical of the received knowledge held by older adults.

Relativistic Thinking

Adolescents are more likely to engage in relativistic thinking —in other words, they are more likely to question others’ assertions and less likely to accept information as absolute truth. Through experience outside the family circle, they learn that rules they were taught as absolute are actually relativistic. They begin to differentiate between rules crafted from common sense (don’t touch a hot stove) and those that are based on culturally relative standards (codes of etiquette). This can lead to a period of questioning authority in all domains.

As we continue through this module, we will discuss how this influences moral reasoning, as well as psychosocial and emotional development. These more abstract developmental dimensions (cognitive, moral, emotional, and social dimensions) are not only more subtle and difficult to measure, but these developmental areas are also difficult to tease apart from one another due to the inter-relationships among them. For instance, our cognitive maturity will influence the way we understand a particular event or circumstance, which will in turn influence our moral judgments about it, and our emotional responses to it. Similarly, our moral code and emotional maturity influence the quality of our social relationships with others.

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Linn, P. (2016). Risky behaviors: Integrating adolescent egocentrism with the theory of planned behavior. Review of General Psychology, 20 (4), 392-398. ↵

- Kuhn, D. (2013). Reasoning. In Philip D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 744-764). New York: NY: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Klaczynski, P.A. & Felmban, W.S. (2014). Heuristics and biases during adolescence: Developmental reversals and individual differences. In Henry Markovitz (Ed.), The developmental psychology of reasoning and decision making (pp. 84-111). New York, NY: Psychology Press. ↵

- Crone, E.A., & Dahl, R.E. (2012). Understanding adolescence as a period of social-affective engagement and goal flexibility. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 13 (9), 636-650. ↵

- Adolescent development; cognitive development. Authored by : Jennifer Lansford. Provided by : Duke University. Located at : http://nobaproject.com/modules/adolescent-development?r=LDE2MjU3 . Project : The Noba Project. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Stages of Development. Authored by : OpenStax College. Located at : http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:1/Psychology . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/content/col11629/latest/.

- Adolescence. Provided by : Boundless. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/boundless-psychology/chapter/adolescence/ . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Adolescent egocentrism. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolescent_egocentrism#cite_note-Elkindeia-1 . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- adolescent boys. Authored by : An Min. Provided by : Pxhere. Located at : https://pxhere.com/en/photo/1515959 . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- Adolescence. Provided by : Wikipedia. Located at : https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adolescence . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Educational Psychology. Authored by : Kelvin Seifert. Provided by : OpenStax. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:9u2dcFad@2/Cognitive-development-the-theory-of-Jean-Piaget . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected].

- Formal operational stage - Intro to Psychology. Provided by : Udacity. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hvq7tq2fx1Y . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Adolescent Brain Development: Implications for Understanding Risk and Resilience Processes through Neuroimaging Research

Amanda sheffield morris.

1 Oklahoma State University and Laureate Institute for Brain Research

Lindsay M. Squeglia

2 Medical University of South Carolina

Joanna Jacobus

3 University of California, San Diego

Jennifer S. Silk

4 University of Pittsburgh

This special section focuses on research that utilizes neuroimaging methods to examine the impact of social relationships and socioemotional development on adolescent brain function. Studies include novel neuroimaging methods that further our understanding of adolescent brain development. This special section has a particular focus on how study findings add to our understanding of risk and resilience. In this introduction to the special section, we discuss the role of neuroimaging in developmental science and provide a brief review of neuroimaging methods. We present key themes that are covered in the special section papers including: 1) emerging methods in developmental neuroscience; 2) emotion-cognition interaction; and 3) the role of social relationships in brain function. We conclude our introduction with future directions for integrating developmental neuroscience into the study of adolescence, and highlight key points from the special section’s commentaries which include information on the landmark Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study.

Our understanding of adolescent brain development has dramatically increased in recent years due to advances in neuroimaging techniques. Studies examining social and emotional risk and protective factors, in conjunction with markers of neural integrity, have great potential to improve our knowledge of the developmental trajectories of mental health outcomes and psychopathology ( Steinberg, 2008 ). Nevertheless, developmental science has yet to fully integrate neuroscience findings into developmental research and theory on adolescence. In response, this special section focuses on research that utilizes neuroimaging methods to examine the impact of social relationships (parents and peers) and socioemotional development on adolescent brain function. In addition, studies include novel neuroimaging methods and genetic analyses that further our understanding of adolescent brain development. This special section has a particular focus on how study findings add to our understanding of risk and resilience trajectories of psychopathology and positive youth development. The special section ends with commentary discussing critical next steps for integrating developmental neuroscience into the study of adolescence, and information on the landmark Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study and the potential for this open science investigation to impact the field of adolescent development.

The Role of Neuroimaging in Developmental Science

The brain is rapidly changing during adolescence, spanning microstructural to macrostructural changes. This is a dynamic, complex, and adaptive process. Neuroimaging advances have allowed developmental scientists to make great advances, as in vivo imaging has provided us with a tool to visualize and make inferences about organizational changes in the brain that likely underlie socioemotional and neurocognitive development ( Bandettinni, 2012 ). Structural and functioning neuroimaging in particular have provided a better understanding of developmental and age-related changes ( Giedd, 2008 ). Estimates of anatomical associations with genetic and environmental influences can also be explored and discussed in the context of typical and atypical behavioral outcomes that evolve during adolescence. Using neuroimaging in developmental research can help elucidate the complex relationships between underlying neural substrates, the environment, and functional outcomes. Neuroimaging can include topics covered in this special section such as decision-making, risky behaviors, resilience, and emotional control. Despite exciting advances in technology that have changed the way we study adolescent brain development, there are methodological considerations in different neuroimaging modalities that are important to recognize in order to make informed interpretations.

Neuroimaging and Methodological Considerations

The first use of neuroimaging in humans was in 1991, which was followed by an explosion of imaging research in the early 2000s. There are several different noninvasive approaches for measuring structural brain changes and brain activity in children and adolescents. The appropriate imaging modality depends on the scientific question and falls into the two broad categories of functional and structural imaging. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is one of the most central and well-known imaging modalities because it is relatively safe (e.g., no radiation) and can be done repeatedly, does not require intravenous injection like its predecessor positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, can spatially localize brain activity (compared to electroencephalography or EEG), and detects subtle differences in brain activity. fMRI includes task-based paradigms, where participants are actively engaged in a cognitive task while in the scanner, as well as resting-state paradigms that seek to understand how the brain functions “at rest” (i.e., when not performing a task). fMRI signals are interpreted from a regionally correlated blood-oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal. BOLD signal has been found to correspond with other measures of neural activity, however an ongoing critique of BOLD is its susceptibility to physiological factors that could influence relationships between blood flow and neural activity (Bandetinni, 2012; Glover et al., 2011 ). Further, there are logistical and computational challenges such as head motion, task compliance and performance accuracy, image registration and multiple comparisons corrections, and a lack of normative data, which could introduce bias into statistical estimates and therefore result in spurious conclusions. Advanced methodological and computational approaches have improved the reliability of task-based fMRI developmental studies ( Herting et al., 2017 ), and have improved data quality ( Grayson & Fair, 2017 ).

Structural imaging provides high-resolution information about the details of macrostructural and microstructural anatomical changes that occur throughout development. While structural imaging does not provide information on functional brain activity, this mode of imaging helps make inferences about overall volume changes in gray matter (neuronal cell bodies, dendrites, and synapses) and white matter (axons connecting gray matter, white because of the fatty myelin sheath surrounding the axon), as well as more subtle changes that occur in neural tissue. For example, subtle changes in brain structure during adolescence include cortical thinning and increased myelination. Structural neuroimaging faces many of the same logistical and computational challenges as functioning imaging.

MRI modalities are appealing to use for child and adolescent research as they are noninvasive and safe to use as long as the child does not have metal in or on their body. The noninvasive quality of MRI, compared to other imaging modalities that involve radiation (e.g. computed tomography), allows for repeated scans, a critical component to modeling growth trajectories over time in relation to behavioral outcomes.

Key Themes Explored in this Special Section

Three primary themes are included in this special section: 1) emerging methods, 2) emotion-cognition interaction, and 3) social relationships and brain function. As mentioned previously, a risk and resilience focus is evident within each theme and across all papers, with an emphasis on psychopathology and positive adjustment. Current models of resilience across childhood focus on multidisciplinary approaches to examine protective mechanisms within multiple levels of ecosystems, from the molecular level to broader social systems and families ( Masten, 2007 ; Henry, Morris, Harrist, 2015 ), as illustrated by the studies in this special section.

Emerging methods.

Several papers in the special section focused on emerging methods, examining individual differences by analyzing person-specific networks and genetic and neural markers. Specifically, Beltz (2018) utilizes a new approach to fMRI analysis: extended unified structural equation models (euSEMs) implemented in group iterative multiple model estimation (GIMME). This person-specific, data-driven approach allows us to better understand individual differences in brain development in researching heterogeneous samples. Such an approach is useful in understanding differences in brain connectivity and has potential for answering questions about adolescent risk and resilience. Trucco et al. (2018) examined important neurobiological and genetic mechanisms that affect problematic behaviors in adolescents. Youth with a genetic risk marker in GABRA2 had different neurological responses to emotional words, and these variations predicted negative emotionality and externalizing problems. Studies such as these highlight our advancing knowledge of the nuanced relationship between neural endophenotypes and behavioral outcomes, which may aid in development of targeted prevention and intervention programs. Imaging genomics will continue to enrich our understanding of the complex issue of adolescent brain development, including the identification of important risk and resilience factors.

Emotion-cognition interaction.

Neuroimaging research conducted with adolescents in the past decade has demonstrated that the neural substrates of emotional reactivity and cognitive control contribute to adaptive functioning and risk for psychopathology during this transition period. However, there is a need to better understand how systems that contribute to emotional reactions and cognitive control of emotions interact with each other when adolescents are faced with emotional decisions and experiences. Brieant et al. (2018) and Hansen et al. (2018) address this need by examining the influence of emotion-cognition interactions on adolescent adaptive functioning. In a longitudinal study, Brieant et al. show that high levels of positive emotion can attenuate risk for externalizing behavior problems among adolescents with lower prefrontal cognitive control on a laboratory cognitive interference task. Hansen et al. examine risky sexual decision-making, a behavior that lies at the interface of emotion and cognition. They find that although behavioral performance on a response inhibition task did not predict sexual risk, adolescents who needed to recruit more middle frontal gyrus activation on the task made riskier sexual decisions, such as reduced use of condoms. Another study in this special section, Rodrigo et al., focuses on emotional responding during risky decision-making. This study demonstrates the importance of taking a more nuanced view of emotion by focusing on neural circuits involved in the experience of counterfactual emotions, such as regret and disappointment, during a social decision-making task. These studies exemplify the ways in which neuroimaging investigations of more complex emotions and emotion-cognition interactions may help to move the field toward a better understanding of adolescents’ adaptive and maladaptive functioning during real-world emotional situations.

Social relationships and brain function.

During adolescence, the brain is primed to experience social relationships and social influences ( Cron & Dahl, 2012 ). Two of the manuscripts in the special section focus on peers and social status. Lee and colleagues (2018) examined neural responses to social status words (e.g., loser, popular) and depressive symptoms. They found that reduced activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC, a brain region involved in emotion regulation) in response to negative social status words explained the association between self-reported social risk (peer victimization and fear of negative evaluation) and depressive symptoms, suggesting altered DLPFC activity in response to social information may be a neural correlate of depression during adolescence. Schriber et al. (2018) examined social influences of both parents and peers in their longitudinal study. They examined neural responses to social exclusion in hostile school environments and whether family connectedness buffered the effects of social exclusion on later deviance. The link between hostile school environments and social deviance was mediated by greater reactivity to social deviance in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex, a region implicated in social pain and social susceptibility. Importantly, among youth who had a strong connection to family, this connection was not found, suggesting that family connectedness is a protective factor against this neural susceptibility. Lee, Qu, and Telzer also found protective effects of family connectedness. In their study, mother-teen dyads who reported high family connectedness showed similar neural profiles during stressful tasks. Notably, neural synchrony among mothers and adolescents was associated with less stress in youth. Saxbe et al. (2018) examined family aggression and adversity. Using longitudinal data, they found that family aggression and externalizing behavior were predicted by differences in amygdala volumes and amygdala connectedness. Taken together, findings across these studies provide support for the premise that adolescents are “wired to connect” and when that connection is positive, it results in better outcomes for youth both concurrently and over time. In contrast, when there is family dysfunction or peer victimization, adolescents are more likely to develop neurological circuitry that puts them at risk for psychopathology.

Future Directions: Opportunities and Challenges

Incorporating neuroscience into the study of adolescence is both a challenge and an opportunity ( Dahl, 2004 ). Nevertheless, doing so will help move the field forward by expanding our understanding of the complexity of development and the role of context and social experiences in brain function. Indeed, integration and organization of the brain connectome (i.e., circuitry) change as the adolescent brain matures ( Stevens, 2016 ), and there is a shift from local to distributed profiles and changes in strength of neural connections as the brain increases in efficiency. Moreover, different neural networks have been found to have different developmental trajectories ( Stevens et al., 2016 ), making adolescence an opportune developmental period to examine neurological correlates of risk and resilience.