Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Types of Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

This section lists the types of sources most frequently used in academic research and describes the sort of information that each commonly offers.

Print Sources

Books and Textbooks: Odds are that at least one book has been written about virtually any research topic you can imagine (and if not, your research could represent the first steps toward a best-selling publication that addresses the gap!). Because of the time it takes to publish a book, books usually contain more dated information than will be found in journals and newspapers. However, because they are usually much longer, they can often cover topics in greater depth than more up-to-date sources.

Newspapers: Newspapers contain very up-to-date information by covering the latest events and trends. Newspapers publish both factual information and opinion-based articles. However, due to journalistic standards of objectivity, news reporting will not always take a “big picture” approach or contain information about larger trends, instead opting to focus mainly on the facts relevant to the specifics of the story. This is exacerbated by the rapid publication cycles most newspapers undergo: new editions must come out frequently, so long, in-depth investigations tend to be rarer than simple fact-reporting pieces.

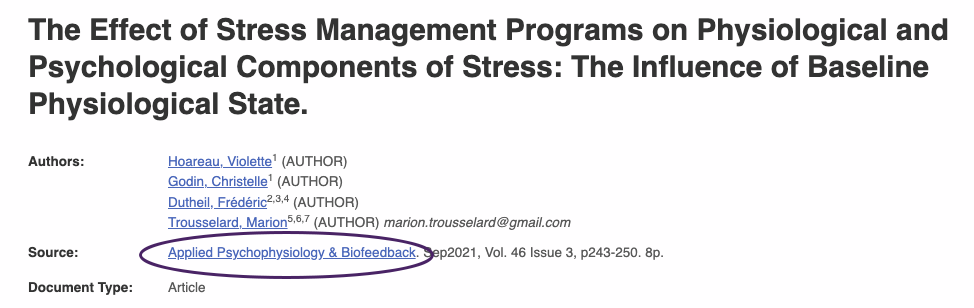

Academic and Trade Journals: Academic and trade journals contain the most up-to-date information and research in industry, business, and academia. Journal articles come in several forms, including literature reviews that overview current and past research, articles on theories and history, and articles on specific processes or research. While a well-regarded journal represents the cutting-edge knowledge of experts in a particular field, journal articles can often be difficult for non-experts to read, as they tend to incorporate lots of technical jargon and are not written to be engaging or entertaining.

Government Reports and Legal Documents: The government regularly releases information intended for internal and/or public use. These types of documents can be excellent sources of information due to their regularity, dependability, and thoroughness. An example of a government report would be any of the reports the U.S. Census Bureau publishes from census data. Note that most government reports and legal documents can now be accessed online.

Press Releases and Advertising: Companies and special interest groups produce texts to help persuade readers to act in some way or inform the public about some new development. While the information they provide can be accurate, approach them with caution, as these texts' publishers may have vested interests in highlighting particular facts or viewpoints.

Flyers, Pamphlets, Leaflets: While some flyers or pamphlets are created by reputable sources, because of the ease with which they can be created, many less-than-reputable sources also produce these. Pamphlets and leaflets can be useful for quick reference or very general information, but beware of pamphlets that spread propaganda or misleading information.

Digital and Electronic Sources

Multimedia: Printed material is certainly not the only option for finding research. You might also consider using sources such as radio and television broadcasts, interactive talks, and recorded public meetings. Though we often go online to find this sort of information today, libraries and archives offer a wealth of nondigitized media or media that is not available online.

Websites: Most of the information on the Internet is distributed via websites. Websites vary widely in terms of the quality of information they offer. For more information, visit the OWL's page on evaluating digital sources.

Blogs and personal websites: Blogs and personal sites vary widely in their validity as sources for serious research. For example, many prestigious journalists and public figures may have blogs, which may be more credible than most amateur or personal blogs. Note, however, that there are very few standards for impartiality or accuracy when it comes to what can be published on personal sites.

Social media pages and message boards: These types of sources exist for all kinds of disciplines, both in and outside of the university. Some may be useful, depending on the topic you are studying, but, just like personal websites, the information found on social media or message boards is not always credible.

Understand and Evaluate Sources

Types of sources.

- Evaluate Sources

- Check the Facts

types of sources you are likely to encounter during your academic research.

Scholarly or Peer-reviewed Journals

A scholarly or peer-reviewed journal contains articles written by experts in a particular field.

journals, in most cases:

- use scholarly or technical language.

- include a full bibliography of sources cited in the article.

- are often peer-reviewed (sometimes called "referred").

View the anatomy of an article to see the typical components.

- Academic Search Elite (EBSCO) This link opens in a new window Find articles in any subject or academic discipline.

- GALE ACADEMIC ONEFILE This link opens in a new window Find scholarly/peer-reviewed and popular journal publications.

News and Magazines (Popular Sources)

News and magazine articles can help introduce you to a topic and see how the topic is being discussed in society.

Articles in popular sources:

- rarely have a references section.

- often contain images and advertisements.

- may contain an argument, opinion, or analysis of an issue.

Professional or Trade Journals

Trade publications communicate news and trends in a particular field.

Articles in trade journals:

- use the language (and jargon) of the field.

Books and eBooks

Academic books and eBooks:

- summarize research or issues related to its topic.

- eBook Academic Collection (EBSCOhost) This link opens in a new window Find thousands of academic ebooks in all subjects.

Conference Proceedings

Conference proceedings are compilations of papers, research, and information presented at professional conferences.

peer -reviewed and are often the first publication of research that later will appear in a scholarly or peer-reviewed article.

Government Documents

scientific and technical information , statistics, transcripts of hearings, white papers, consumer information, maps and more.

- HathiTrust Digital Library This link opens in a new window As a digital repository for the nation's great research libraries, HathiTrust brings together the immense collections of partner institutions. HathiTrust was conceived as a collaboration of the thirteen universities of the Committee on Institutional Cooperation and the University of California system to establish a repository for these universities to archive and share their digitized collections.

Theses and Dissertations

review of an academic committee but are not considered "peer-reviewed."

- Dissertations and Theses @ UNI This link opens in a new window This collection contains many dissertations and theses written by graduate students at the University of Northern Iowa. Many of them can be accessed by anyone worldwide.

- Open Access Theses and Dissertations This link opens in a new window Openly available theses and dissertations from over 1000 colleges, universities, and research institutions.

- Last Updated: Apr 4, 2022 10:28 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uni.edu/understand_and_evaluate_sources

Understanding & Evaluating Sources

- Get Started

- Evaluating Sources

- Different Types of Sources

- Fact-checking

- Recognizing Bias

Types of Sources - Some Useful Tools

- Anatomy of a Scholarly Article Check out the typical components of a scholarly journal article (from North Carolina State University Libraries).

- Types of sources - Quick Reference Chart There are key differences between scholarly, popular and professional publications. For a side-by-side comparison check out our Quick Reference chart (from University of British Colombia Libraries).

Types of Sources - Videos

- Different Types of Sources From Cal State University Northridge Library

Types of Sources

These are sources that you are likely to encounter when doing academic research.

Questions? Ask us !

Scholarly publications (Journals)

A scholarly publication contains articles written by experts in a particular field. The primary audience of these articles is other experts. These articles generally report on original research or case studies. Many of these publications are "peer reviewed" or "refereed". This means that scholars in the same field review the research and findings before the article is published. Articles in scholarly publications, in most cases:

are written by and for faculty, researchers, or other experts in a field

use scholarly or technical language

include a full bibliography of sources cited in the article

are often peer reviewed (refereed)

To see the typical components of a scholarly journal article check out the Anatomy of a Scholarly Article page from North Carolina State University Libraries.

Popular sources (News and Magazines)

There are many occasions on which reading articles from popular sources can help to introduce you to a topic and introduce you to how that topic is being discussed in society. Articles in popular sources, in most cases:

are written by journalists or professional writers for a general audience

written in a language that is easy to understand by the general public

rarely have a bibliography - rather, they are fact-checked through the editorial process of the publication they appear in

don't assume prior knowledge of a subject area - for this reason, they are often very helpful to read if you don't know a lot about your subject area yet

may contain an argument, opinion, or analysis of an issue

Professional / Trade sources

Trade publications are generally for practitioners. They are focused on a specific field but are not intended to be "scholarly". Rather, they communicated the news and trends in that field. Articles in trade publications, in most cases:

are written by practitioners in a field (nurses, teachers, social workers, etc)

use the language (and jargon) of the field

Books / Book Chapters

Many academic books will be edited by an expert or group of experts. Often, books are a good source for a thorough investigation of a topic. Unlike a scholarly article, which will usually focus on the results of one research project, a book is likely to include an overview of research or issues related to its topic.

Conference proceedings

Conference proceedings are compilations of papers, research, and information presented at conferences. Proceedings are sometimes peer-reviewed and are often the first publication of research that later appears in a scholarly publication (see above!). Proceedings are more commonly encountered (via databases and other searching) in science and engineering fields that in the arts and humanities.

Government Documents

The Government Printing Office (GPO) disseminates information issued by all three branches of the government to federal depository libraries (including NMSU). Additionally, the many departments of the government publish reports, data, statistics, white papers, consumer information, transcripts of hearings, and more. Some of the information published by government offices is technical and scientific. Other information is meant for the general public.

Theses & Dissertations

Theses and dissertations are the result of an individual student's research while in a graduate program. They are written under the guidance and review of an academic committee but are not considered "peer-reviewed" or "refereed" publications.

- << Previous: Evaluating Sources

- Next: Fact-checking >>

- Last Updated: Mar 22, 2024 12:20 PM

- URL: https://nmsu.libguides.com/sources

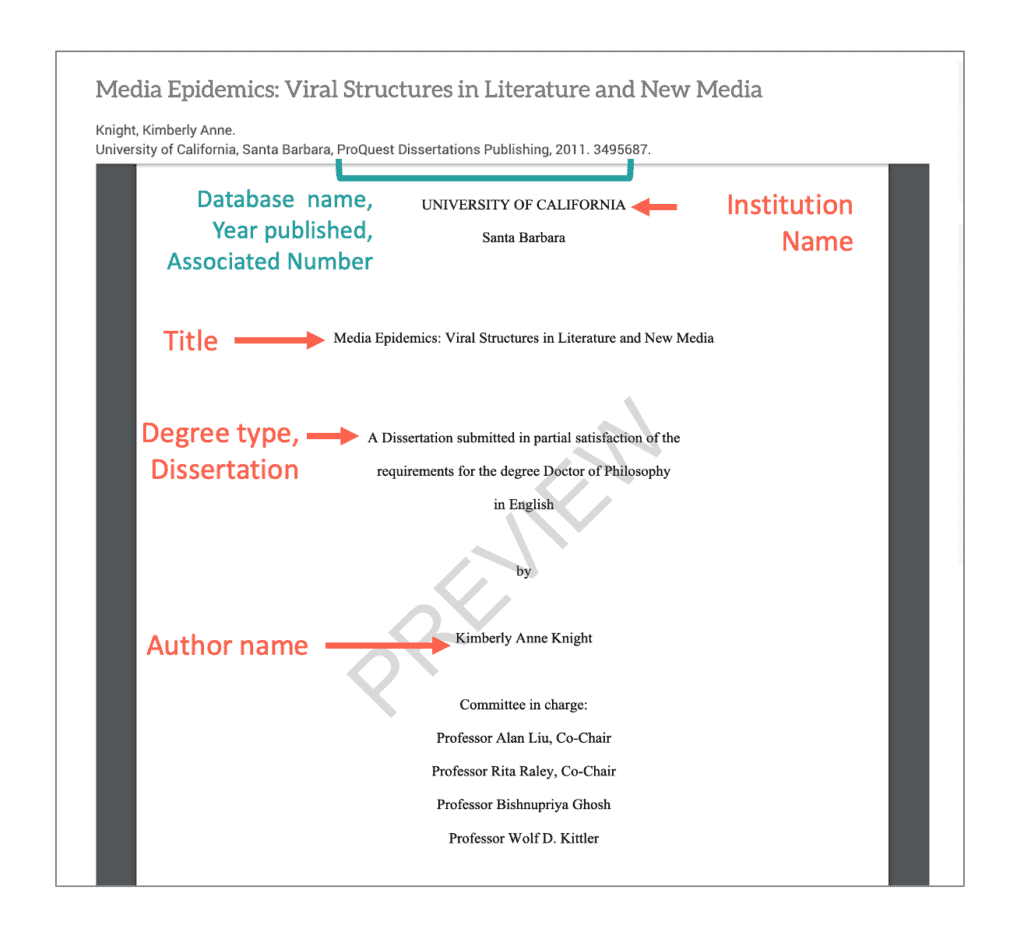

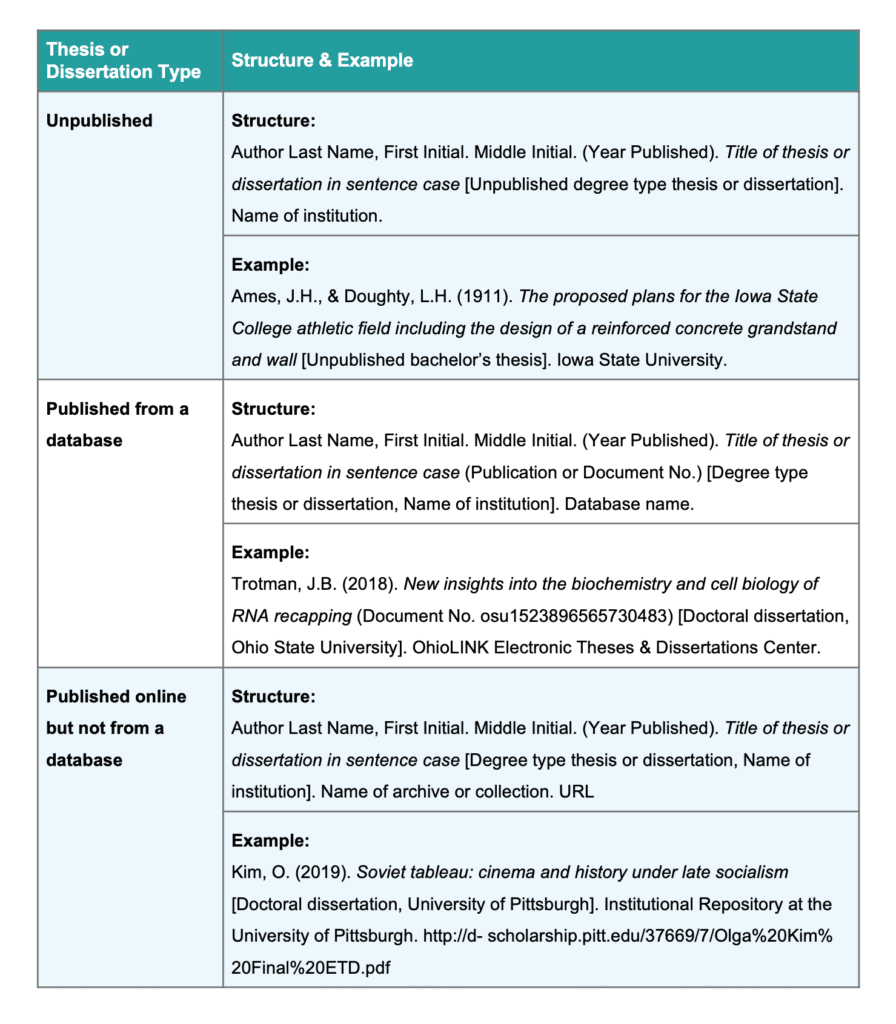

Home / Guides / Citation Guides / APA Format / How to Cite a Thesis or Dissertation in APA

How to Cite a Thesis or Dissertation in APA

In this citation guide, you will learn how to reference and cite an undergraduate thesis, master’s thesis, or doctoral dissertation. This guide will also review the differences between a thesis or dissertation that is published and one that has remained unpublished. The guidelines below come from the 7th edition of the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association (2020a), pages 333 and 334. Please note that the association is not affiliated with this guide.

Alternatively, you can visit EasyBib.com for helpful citation tools to cite your thesis or dissertation .

Guide Overview

Citing an unpublished thesis or dissertation, citing a published dissertation or thesis from a database, citing a thesis or dissertation published online but not from a database, citing a thesis or dissertation: reference overview, what you need.

Since unpublished theses can usually only be sourced in print form from a university library, the correct citation structure includes the university name where the publisher element usually goes.

Author’s last name, F. M. (Year published). Title in sentence case [Unpublished degree type thesis or dissertation]. Name of institution.

Ames, J. H., & Doughty, L. H. (1911). The proposed plans for the Iowa State College athletic field including the design of a reinforced concrete grandstand and wall [Unpublished bachelor’s thesis]. Iowa State University.

In-text citation example:

- Parenthetical : (Ames & Doughty, 1911)

- Narrative : Ames & Doughty (1911)

If a thesis or dissertation has been published and is found on a database, then follow the structure below. It’s similar to the format for an unpublished dissertation/thesis, but with a few differences:

- The institution is presented in brackets after the title

- The archive or database name is included

Author’s last name, F. M. (Year published). Title in sentence case (Publication or Document No.) [Degree type thesis or dissertation, Name of institution]. Database name.

Examples 1:

Knight, K. A. (2011). Media epidemics: Viral structures in literature and new media (Accession No. 2013420395) [Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Trotman, J.B. (2018). New insights into the biochemistry and cell biology of RNA recapping (Document No. osu1523896565730483) [Doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University]. OhioLINK Electronic Theses & Dissertations Center.

In the example given above, the dissertation is presented with a Document Number (Document No.). Sometimes called a database number or publication number, this is the identifier that is used by the database’s indexing system. If the database you are using provides you with such a number, then include it directly after the work’s title in parentheses.

If you are interested in learning more about how to handle works that were accessed via academic research databases, see Section 9.3 of the Publication Manual.

In-text citation examples :

- Parenthetical citation : (Trotman, 2018)

- Narrative citation : Trotman (2018)

Author’s last name, F. M. (Year Published). Title in sentence case [Degree type thesis or dissertation, Name of institution]. Name of archive or collection. URL

Kim, O. (2019). Soviet tableau: cinema and history under late socialism [Doctoral dissertation, University of Pittsburgh]. Institutional Repository at the University of Pittsburgh. https://d-scholarship.pitt.edu/37669/7/Olga%20Kim%20Final%20ETD.pdf

Stiles, T. W. (2001). Doing science: Teachers’ authentic experiences at the Lone Star Dinosaur Field Institute [Master’s thesis, Texas A&M University]. OAKTrust. https://hdl.handle.net/1969.1/ETD-TAMU-2001-THESIS-S745

It is important to note that not every thesis or dissertation published online will be associated with a specific archive or collection. If the work is published on a private website, provide only the URL as the source element.

In-text citation examples:

- Parenthetical citation : (Kim, 2019)

- Narrative citation : Kim (2019)

- Parenthetical citation : (Stiles, 2001)

- Narrative citation : Stiles (2001)

We hope that the information provided here will serve as an effective guide for your research. If you’re looking for even more citation info, visit EasyBib.com for a comprehensive collection of educational materials covering multiple source types.

If you’re citing a variety of different sources, consider taking the EasyBib citation generator for a spin. It can help you cite easily and offers citation forms for several different kinds of sources.

To start things off, let’s take a look at the different types of literature that are classified under Chapter 10.6 of the Publication Manual :

- Undergraduate thesis

- Master’s thesis

- Doctoral dissertation

You will need to know which type you are citing. You’ll also need to know if it is published or unpublished .

When you decide to cite a dissertation or thesis, you’ll need to look for the following information to use in your citation:

- Author’s last name, and first and middle initials

- Year published

- Title of thesis or dissertation

- If it is unpublished

- Publication or document number (if applicable; for published work)

- Degree type (bachelor’s, master’s, doctoral)

- Thesis or dissertation

- Name of institution awarding degree

- DOI (https://doi.org/xxxxx) or URL (if applicable)

Since theses and dissertations are directly linked to educational degrees, it is necessary to list the name of the associated institution; i.e., the college, university, or school that is awarding the associated degree.

To get an idea of the proper form, take a look at the examples below. There are three outlined scenarios:

- Unpublished thesis or dissertation

- Published thesis or dissertation from a database

- Thesis or dissertation published online but not from a database

American Psychological Association. (2020a). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

American Psychological Association. (2020b). Style-Grammar-Guidelines. https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/citations/basic-principles/parenthetical-versus-narrative

Published August 10, 2012. Updated March 24, 2020.

Written and edited by Michele Kirschenbaum and Elise Barbeau. Michele Kirschenbaum is a school library media specialist and the in-house librarian at EasyBib.com. Elise Barbeau is the Citation Specialist at Chegg. She has worked in digital marketing, libraries, and publishing.

APA Formatting Guide

APA Formatting

- Annotated Bibliography

- Block Quotes

- et al Usage

- In-text Citations

- Multiple Authors

- Paraphrasing

- Page Numbers

- Parenthetical Citations

- Reference Page

- Sample Paper

- APA 7 Updates

- View APA Guide

Citation Examples

- Book Chapter

- Journal Article

- Magazine Article

- Newspaper Article

- Website (no author)

- View all APA Examples

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

To cite a published thesis in APA style, it is important that you know some basic information such as the author, publication year, title of the thesis, institute name, archive name, and URL (uniform resource locator). The templates for an in-text citation and reference list entry of a thesis, along with examples, are given below:

In-text citation template and example:

Use the author surname and the publication year in the in-text citation.

Author Surname (Publication Year)

Cartmel (2007)

Parenthetical:

(Author Surname, Publication Year)

(Cartmel, 2007)

Reference list entry template and example:

The title of the thesis is set in sentence case and italicized. Enclose the thesis and the institute awarding the degree inside brackets following the publication year. Then add the name of the database followed by the URL.

Author Surname, F. M. (Publication Year). Title of the thesis [Master’s thesis, Institute Name]. Name of the Database. URL

Cartmel, J. (2007). Outside school hours care and schools [Master’s thesis, Queensland University of Technology]. EPrints. http://eprints.qut.edu.au/17810/1/Jennifer_Cartmel_Thesis.pdf

To cite an unpublished dissertation in APA style, it is important that you know some basic information such as the author, year, title of the dissertation, and institute name. The templates for in-text citation and reference list entry of an online thesis, along with examples, are given below:

Author Surname (Year)

Averill (2009)

(Author Surname, Year)

(Averill, 2009)

The title of the dissertation is set in sentence case and italicized. Enclose “Unpublished doctoral dissertation” inside brackets following the year. Then add the name of the institution awarding the degree.

Author Surname, F. M. (Publication Year). Title of the dissertation [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Name of the Institute.

Averill, R. (2009). Teacher–student relationships in diverse New Zealand year 10 mathematics classrooms: Teacher care [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Victoria University of Wellington.

APA Citation Examples

Writing Tools

Citation Generators

Other Citation Styles

Plagiarism Checker

Upload a paper to check for plagiarism against billions of sources and get advanced writing suggestions for clarity and style.

Get Started

TAFT COLLEGE

Types of Sources: Types of Sources

- Types of Sources

- Identifying Primary Sources

- Identifying Scholarly Sources

- Finding Sources

- Selecting Sources

- Introduction

- Material Formats and Types

- Delivery Method

Sources can be defined at least two different ways. When people use the phrase "types of sources" they may be referring to the:

- Level or distance from the original source of information (primary, secondary, tertiary)

- Format of the information source (book, article, movie, blog, etc.)

This guide will clarify both types of definitions. Which source is the best? It depends! Each source has unique characteristics which need to be considered when making the decision to use a source for research. Most college instructors and many high school teachers will insist on academic or scholarly sources, but it depends on the assignment.

Accessible web version of Distance Away from the Original Source Infographic

Information sources are usually organized by type. Books, journal articles, blogs, photographs, data sets, patents, are all types of sources commonly used for research. See the Identifying Primary Sources page in this guide for more information about various types of sources.

Image courtesy of https://weloty.com/3-tips-for-recording-research-interviews/

A source may be in print or other types of physical format. Additionally, sources are also available electronically such as an e-Book.

In other words, to say you have an article, song or movie does not imply you have an article in print, a CD of a song or a DVD of a movie. All these formats are available in print and digital versions, and you, the researcher, must decide which method of delivery you prefer or which is most readily available at time of need.

The Taft College Library has both CDs and DVDs available for checkout. Below are examples from our catalog.

Some content has been adapted from the Wichita State University Types of Sources LibGuide.

Last updated August 6, 2018

- Next: Identifying Primary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 31, 2023 3:19 PM

- URL: https://lib.taftcollege.edu/typesofsources

University of Denver

University libraries, research guides.

- Library Guides

University College Research Guide

- Cite my sources

- Using Compass

- Get full text of a specific article

- Request sources from other libraries

- What is "Peer Review"?

How do I cite a source?

Why do i need to cite my sources, when should i cite a source, more resources.

- Library 101 Workshop

To cite a source properly, you need to follow the rules of a particular citation style.

University College utilizes the Turabian Author-Date citation style to document sources utilized in all written assignments.

- Turabian Style Quick Guide Offers some samples of Turabian Author/Date style. While it is not comprehensive, it is a good overview.

Citing your sources is:

- the smart thing to do: readers will consider your work more credible if they know where your information comes from.

- the honest thing to do: it prevents plagiarism by giving credit to the original author of an idea.

Imagine research as a conversation -- scholars are trading ideas back and forth and building on the findings of earlier work. Citing your sources is an important part of contributing to this conversation -- it allows readers to understand how your work fits into the overall conversation.

Citing your sources in a standard style also helps readers tell at a glance what type of source you used (book vs. journal article, etc), and it helps readers find and reference the sources you used.

What is Plagiarism?

The DU Honor Code defines plagiarism as "including any representation of another's work or ideas as one's own in academic and educational submissions."

At DU, plagiarism is seen as a form of academic misconduct and can result in severe consequences. These explanations of the most common types of plagiarism from Bowdoin College can help you learn to detect plagiarism in your own and other's work.

To avoid plagiarism, cite sources when:

- You directly quote a source

- You paraphrase a source

- You summarize someone else's ideas in your own words

- You draw on facts, information, or data from someone else

- You want to add supplemental information not included in your paper, such as footnotes or endnotes

Note: You do not need to cite generally accepted knowledge. For more information, see Not-So-Common Knowledge .

A general rule of thumb is: "When in doubt, cite it."

What is Plagiarism Detection Software?

DU uses a plagiarism detection software called TurnItIn. When a student turns in a paper through Canvas, TurnItIn checks the internet and many databases to see if anything has been copied from another person’s work.

- Zotero Free, web-based, citation management tool.

Reference Librarian

- << Previous: What is "Peer Review"?

- Next: Library 101 Workshop >>

- Last Updated: Mar 21, 2024 9:42 AM

- URL: https://libguides.du.edu/ucolresearch

Doing Research: Source Types

- Getting Started

- Source Types

- Search Tips

- Evaluating Sources

- Research As Conversation

- Tracking Down Materials

- Citing Sources

A Way to Think About Sources

"Sources are people talking to other people." Doug Downs

Sources Overview

As you work with particular sources, be sure you are analyzing the source itself to understand why it was written or created, who wrote it, what their expertise is, and who the intended audience is. These kinds of questions help you figure out if you're using the appropriate sources for any given information task. Use the information below to reflect further on your sources:

Sources have different functions (BEAM)

- B ackground sources – Wikipedia, textbooks, specialized encyclopedias, review articles

- E xhibits –poll data, transcribed interviews, text of public laws or court opinions, historical documents

- A rguments – works that propose a thesis and develop it with evidence

- M ethods – works that propose how to think about something; theory or methodology is the focus

There are different authors of information

- Journalists and other professional writers who report the news or write books and articles about topics from a non-specialist perspective; these types of sources are usually non-scholarly (sometimes we call them "popular")

- Subject experts who write for other experts; these types of sources are almost always scholarly. Experts sometimes write non-scholarly pieces for newspapers, magazines or blogs about their topic for a general audience.

- Artists who create tangible expressions of their ideas

- Members of the public who interpret and express ideas publicly

There are different audiences for publications

- General readers who want to know factual information about a topic

- General readers who are interested in opinions and commentary

- Members of a particular profession such as teachers, lawyers, or engineers who share common interests

- Scholars and scientists who want to know the latest research findings (and reviews of research)

Scholarly Sources

Quite often you will be expected to use "scholarly" or "peer reviewed" or "academic" sources. How can you tell whether a source is scholarly? Look for these indicators.

- The author is a scientist or scholar, not a journalist. Usually you can find some note about where the author works, and more often than not it's at a college or university. The author usually has the highest degree in their field (like Ph.D.).

- The audience is other researchers, scientists, or scholars, (as well as students in a given field), so the language is fairly complex and assumes a level of sophistication.

- It includes references to the work of other researchers. Look for bibliographic notes and/or a works cited page.

- Scholarly sources are usually published by academic publishers (like Oxford University Press); articles appear in scholarly journals, often with titles like Journal of ....

Though many databases let you limit a search to scholarly or peer reviewed articles, those limiters aren't foolproof. As an example, they will include book reviews, which are not reporting original research. Take a look at " Anatomy of a Scholarly Article " from North Carolina State University Library.

Peer review means the source has been reviewed prior to publication (usually without the reviewers knowing who wrote the source and vice versa); reviewers will then recommend if the work should be published. Many - but not all - scholarly sources have been peer reviewed. To check if your scholarly article has been peer reviewed, you can visit the journal's website.

Primary? Secondary?

The term "primary source" is defined differently by various disciplines. In the humanities, a primary source is a historical document, such as a diary, memoir, a work of art, a news account published when an event was fresh - something from the historical period under examination. In the sciences, a primary source is a scientist's write-up of their research that includes their methods and results, as opposed to science journalism or a summary of research (a "review article") that has been conducted to provide an overview of research on a given topic.

A secondary source is one that has already been analyzed by someone else. Moving even further from the unfiltered event is a tertiary source such as a textbook or encyclopedia, that summarizes knowledge in general terms.

Using primary sources, whether in science or the humanities, helps a researcher get as close as possible to the subject under examination. Using primary sources can be a good way to point your reader to the raw materials of your ideas and provide an opportunity for you to do your own, original analysis.

For more about primary sources, check out our guide to primary sources available in our library.

Types of Sources

People communicate in all kinds of different information packages. Here are some of the most common ones you will encounter, along with ideas on whether or not they are scholarly:

There are many, many other kinds of information packages, too, including the ones listed below.

- Audio & visual files

- Conference papers (sometimes published as books, published online, or unpublished)

- Laws (statutes, court opinions, regulations) and other government documents (hearings, bills, reports)

- Press releases, reports, studies, FAQs, etc., produced by nonprofits and corporations

- Unpublished records, like journals, personal papers, items you would find in the college's archives, stuff in your desk drawer, a box of records taken from an office by investigators

Locating Various Types of Sources

Now that you're more familiar with the types of sources you may encounter, you may be wondering how to go about finding them. Here are tips on how to located various types of sources for your project - although the biggest tip is that if you hit any roadblocks, please ask a librarian for help.

- Try some of the recommended databases on the Articles tab on this guide.

- You can also search Google Scholar for academic articles, too. Use the Tracking Down Materials tab for help on accessing articles that aren't full text on Google Scholar.

- Search the library catalog to find books; we have print books and ebooks. The Books tab also explains how to search for and order books at other libraries. You can look at excerpts for many books - and in some cases, entire books - through Google Books . You'll also find some scholarly articles in the catalog, too.

- You can certainly Google to find newspapers but most papers have a strict paywall, meaning you'll need to pay to subscribe before you can access the papers. Instead, search the recommended databases to find the same content for free!

- To find magazine articles , start with Academic Search Premier (listed under the Articles tab). As with newspapers, you can use Google but you will also probably hit a paywall for most titles.

- The best place to start is Google. As you sort through results, pay attention to who wrote and published the source, the intended audience, the type of source, any claims it makes, etc. Be sure you are thinking critically about the source itself and how it may or may not inform your own understanding of the topic.

- Contact a librarian for more ideas on how to access particular types of sources.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Books >>

- Last Updated: Feb 28, 2024 2:41 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gustavus.edu/research

Types of Sources

- Identifying Primary Sources

- Identifying Scholarly Sources

- Finding Sources

- Selecting Sources

- Online Primary Sources at WSU This link opens in a new window

Further Reading

- Primary Sources for Humanities and Social Sciences by UW-Madison

- Research Help: Types of Sources by McQuade Library at Merrimack

- Types of Sources by OWL

- Understand Types of Material by CliffsNotes

- Introduction

- Defining Sources

- Material Types (Format)

- Delivery Method

Sources can be defined at least two different ways. When people use the phrase "types of sources" they may be referring to the:

- Level or distance from the original source of information ( primary, secondary or tertiary )

- Format of the information source (book, article, movie, blog, etc.)

This guide will clarify both types of definitions. Which source is the best? It depends! Each source has unique characteristics which need to be considered when making the decision. Most college instructors and many high school teachers will insist on academic or scholarly sources, but it depends on the assignment.

Note: words in red or hot linked are included in the glossary . See a similar graphic .

Your topic and research question or thesis statement will determine which resources are best. If you are struggling to find information in scholarly sources, but can find information on the open web, that is a sign you need to re-evaluate your topic or research question. See the page Selecting Sources in this guide or the handout "What Sources Should I Use" below for more help with this issue.

You may find these handouts helpful:

- Evaluating Information Sources- The CAARP Test

- Finding Authoritative Information

- How to Distinguish between types of Periodicals

- Information Timeline

- Types of Periodicals

- What Sources Should I Use?

A primary source is the original source of information on a topic. The source is usually created at the time of study. What defines a primary resource varies slightly with each discipline. Typically, artifacts , diaries and manuscripts , autobiographies or memoirs, photographs, audio files of interviews before editing, blogs and vlogs published and produced by the creator at the time of an event are considered to be primary information sources. See the page about primary sources in this guide for more information about primary sources.

Some information sources may be available in audio or video. Most books and articles are available either in print or online. Books may be available in paperback, hardback, large print or other types of editions or formats . The format and edition of an information source may affect whether the item is considered to be a primary source (the original source of information or an exact replica) or not. However it is usually difficult to tell when something is an exact replica of the original.

Sources can be defined as primary , secondary and tertiary levels away from an event or original idea. Researchers may want to start with tertiary or secondary sources for background information. Learning more about a topic will help most researchers make better use of primary sources.

Information sources are usually organized by type. Books, journal articles, blogs, photographs, data sets, patents, are all types of sources commonly used for research. See the Identifying Primary Sources page in this guide for more information about various types of sources.

In any case, a source may be in print or some type of physical format, or it may be electronic. Some types of formats are always electronic, but formats that are physically available, such as books, are almost always also electronically available.

In other words, to say you have an article, song or movie does not imply you have an article in print, a CD of a song or a DVD of a movie. All these formats are available in print and digital versions, and you, the researcher, must decide which method of delivery you prefer or which is most readily available at time of need.

Attend one of our free workshops!

- Savvy Researcher Workshop Series These research workshops are developed for undergraduate students, graduate students, teaching assistants and instructors. This guide is designed to accompany the workshop schedule for this series. The schedule is included on this guide and is also on the Library Event Calendar.

Ask A Librarian

- Contact a Subject Librarian

Come talk to a librarian in person at the Reference Desk on the first floor of Ablah Library.

If a librarian is not available, you may also seek assistance from other library staff during library hours who will refer you to the appropriate librarian or department as necessary.

See the full schedule of library hours including Reference Desk, presession, intersession, and holiday hours for the main library (Ablah) and for the Chemistry and Music branch libraries. Ablah Library hours are also available on an automated phone line: 316-978-3581.

Chat with us or request a Zoom session via the adjacent chat box. Our chat service is staffed during Reference Desk hours . If chat is not available, send us a question via e-mail .

Circulation Desk (Ablah Library) 316-978-3582

Music Library 316-978-3029

Interlibrary Loan 316-978-3167

Email a librarian with your question or fill out this form .

Subject Librarians are available to help students, faculty, and staff with their research and library instruction needs. Use the left-hand navigation tabs to find the librarian assigned to a particular subject or college . Contact your subject librarian for assistance or to schedule an appointment for a research consultation.

- Next: Identifying Primary Sources >>

- Last Updated: Feb 5, 2024 10:48 AM

- URL: https://libraries.wichita.edu/sources

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

11.4: Types of Sources

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 59938

Learning Objective

- Differentiate types of sources

It is probably an oversimplification to boil research sources down to three categories. But, for the work you’re doing now, this taxonomy for identifying sources makes sense. As you move through the content and practice activities on this page, think about how this method of differentiating sources aligns to your own experience with research.

Is a “print” source always on paper when you receive it? Well, not really. Digital databases and the internet have made the line between “print” and “online” sources more gray than you might expect. A good rule to follow when thinking about whether a source is “print” or “online” is to look at the original intended method of delivery. The New York Times is a print newspaper, even if many of its readers receive its content online. In addition to the fact that an interested reader can actually purchase a physical copy of any given day’s New York Times , its organizational structure is that of a print newspaper.

The same thing is true for academic journals and articles. For the most part, you will access academic journal articles from online databases through your university library or with tools like Google Scholar. Most of these journal articles are delivered to you in PDF format: PDF is a filename extension for Portable Document Format. It’s one of the closest digital file formats to “print.” Thus, academic journal articles are almost always considered “print” sources. In many style guides, you would cite an academic journal that you viewed from a PDF the same as you would if you were citing the same article from a bound journal in your hands.

Unfortunately, identifying what is and isn’t a print source is not always so easy. Take, for instance, The Huffington Post. In many ways, its website is similar to that of the New York Times . However, The Huffington Post has always been completely online. A print copy of the Post has never existed. Beyond that, though, if you take time to examine its organizational structure, the way it publishes and vets content, and the overall scope of Huffington Post , it’s clear that it is much more like Buzzfeed than The New York Times . That doesn’t mean it’s a bad source, by the way. Buzzfeed has won Pulitzer Prizes for some of its journalism. But you can’t call it a print source, and you probably can’t call The Huffington Post a print source either.

On the other side of the campus fence are online-only academic journals. These journals, like Kairos , are peer-reviewed, respected academic journals: Publishing an article in Kairos would be just as credible and noteworthy as publishing an article in Computers and Writing , a traditional print journal. So is Kairos a print source? Probably not. But it is a scholarly source. Remember that it’s always a good idea to look at a source through both lenses: scholarly vs. non-scholarly and print vs. online vs. multimedia.

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- White Papers

- Traditional Encyclopedias (like Encyclopedia Britannica )

Are all online sources bad? Is Wikipedia destroying legitimate research? Should you monkishly eschew all rooms with available WiFi when doing your research? Of course not, on all three accounts. Online sources have their place, and there are good online sources and bad online sources.

What are some online sources that might be useful in your research process? Here are a few examples:

- Government information or statistics

- Company financial reporting data

- Blogs by public figures

- Websites of businesses or organizations

- Online magazines or newspapers

- Discussion boards or forums

- Wiki-style encyclopedias (like Wookiepedia )

- Online academic journals

- Online academic monographs (books)

The quality of these sources can vary widely. You should carefully evaluate all online sources for credibility and relevance. You’ll learn the methods of evaluating an online source later in the module.

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...sessments/5177

What do we mean by “multimedia” sources? Well, basically anything that doesn’t fit neatly into the category of “print” or “online” lands here. Depending upon the nature of your project, you may need to use videos, photographs, podcasts, or even songs as sources. As the researcher, you have the responsibility of vetting these sources, just as you would a website or a book. Sometimes multimedia sources can lead to vibrant and engaging research, so you should not discount their usefulness.

What are some typical multimedia sources that you might look for? Here are a few examples:

- Documentaries on Netflix

- Interviews of public officials on YouTube

- Podcasts about current events

- Photo essays on the New York Times website

- Raw video of events broadcasted to Facebook Live

- Types of Sources. Provided by : University of Mississippi. Project : PLATO Project. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Have a thesis expert improve your writing

Check your thesis for plagiarism in 10 minutes, generate your apa citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- Types of Sources Explained | Examples & Tips

Types of Sources Explained | Examples & Tips

Published on 3 September 2022 by Eoghan Ryan .

Throughout the research process , you’ll likely use various types of sources. The source types commonly used in academic writing include:

Academic journals

Encyclopaedias, instantly correct all language mistakes in your text.

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, frequently asked questions types of sources.

Academic journals are the most up-to-date sources in academia. They’re typically published multiple times a year and contain cutting-edge research. Consult academic journals to find the most current debates and research topics in your field.

There are many kinds of journal articles, including:

- Original research articles: These publish original data.

- Theoretical articles: These contribute to the theoretical foundations of a field.

- Review articles: These summarize the current state of the field.

Credible journals use peer review . This means that experts in the field assess the quality and credibility of an article before it is published. Journal articles include a full bibliography and use scholarly or technical language.

Academic journals are usually published online, and sometimes also in print. Consult your institution’s library to find out what academic journals they provide access to.

Learn how to cite a journal article

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Academic books are great sources to use when you need in-depth information on your research topic.

They’re typically written by experts and provide an extensive overview and analysis of a specific topic. They can be written by a single author or by multiple authors contributing individual chapters (often overseen by a general editor).

Books published by respected academic publishing houses and university presses are typically considered trustworthy sources. Academic books usually include a full bibliography and use scholarly or technical language. Books written for more general audiences are less relevant in an academic context.

Books can be accessed online or in print. Your institution’s library will likely contain access to a wide selection of each.

Learn how to cite a book

Websites are great sources for preliminary research and can help you to learn more about a topic you’re new to.

However, they are not always credible sources . Many websites don’t provide the author’s name, so it can be hard to tell if they’re an expert. Websites often don’t cite their sources, and they typically don’t subject their content to peer review.

For these reasons, you should carefully consider whether any web sources you use are appropriate to cite or not. Some websites are more credible than others. Look for trusted domain extensions:

- URLs that end with .edu are specifically educational resources.

- URLs that end with .gov are government-related.

Both of these are typically considered trustworthy.

Learn how to cite a website

Newspapers can be valuable sources, providing insights on current or past events and trends.

However, news articles are not always reliable and may be written from a biased perspective or with the intention of promoting a political agenda. News articles usually do not cite their sources and are written for a popular, rather than academic, audience.

Nevertheless, newspapers can help when you need information on recent topics or events that have not been the subject of in-depth academic study. Archives of older newspapers can also be useful sources for historical research.

Newspapers are published in both digital and print form. Consult your institution’s library to find out what newspaper archives they provide access to.

Learn how to cite a newspaper article

Encyclopaedias are reference works that contain summaries or overviews of topics rather than original insights. These overviews are presented in alphabetical order.

Although they’re often written by experts, encyclopaedia entries are not typically attributed to a single author and don’t provide the specialised knowledge expected of scholarly sources. As a result, they’re best used as sources of background information at the beginning of your research. You can then expand your knowledge by consulting more academic sources.

Encyclopaedias can be general or subject-specific:

- General encyclopaedias contain entries on diverse topics.

- Subject encyclopaedias focus on a particular field and contain entries specific to that field (e.g., Western philosophy or molecular biology).

They can be found online (including crowdsourced encyclopaedias like Wikipedia) or in print form.

Learn how to cite Wikipedia

Every source you use will be either:

- Primary: The source provides direct evidence about your topic (e.g., a news article).

- Secondary: The source provides an interpretation or commentary on primary sources (e.g., a journal article).

- Tertiary: The source summarizes or consolidates primary and secondary sources but does not provide additional analysis or insights (e.g., an encyclopaedia).

Tertiary sources are often used for broad overviews at the beginning of a research project. Further along, you might look for primary and secondary sources that you can use to help formulate your position.

How each source is categorised depends on the topic of research and how you use the source.

There are many types of sources commonly used in research. These include:

- Journal articles

- Encyclopedias

You’ll likely use a variety of these sources throughout the research process , and the kinds of sources you use will depend on your research topic and goals.

Scholarly sources are written by experts in their field and are typically subjected to peer review . They are intended for a scholarly audience, include a full bibliography, and use scholarly or technical language. For these reasons, they are typically considered credible sources .

Popular sources like magazines and news articles are typically written by journalists. These types of sources usually don’t include a bibliography and are written for a popular, rather than academic, audience. They are not always reliable and may be written from a biased or uninformed perspective, but they can still be cited in some contexts.

In academic writing, the sources you cite should be credible and scholarly. Some of the main types of sources used are:

- Academic journals: These are the most up-to-date sources in academia. They are published more frequently than books and provide cutting-edge research.

- Books: These are great sources to use, as they are typically written by experts and provide an extensive overview and analysis of a specific topic.

It is important to find credible sources and use those that you can be sure are sufficiently scholarly .

- Consult your institute’s library to find out what books, journals, research databases, and other types of sources they provide access to.

- Look for books published by respected academic publishing houses and university presses, as these are typically considered trustworthy sources.

- Look for journals that use a peer review process. This means that experts in the field assess the quality and credibility of an article before it is published.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Ryan, E. (2022, September 03). Types of Sources Explained | Examples & Tips. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/working-sources/source-types/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, tertiary sources explained | quick guide & examples, how to find sources | scholarly articles, books, etc..

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

How to Find Sources | Scholarly Articles, Books, Etc.

Published on June 13, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

It’s important to know how to find relevant sources when writing a research paper , literature review , or systematic review .

The types of sources you need will depend on the stage you are at in the research process , but all sources that you use should be credible , up to date, and relevant to your research topic.

There are three main places to look for sources to use in your research:

Research databases

- Your institution’s library

- Other online resources

Table of contents

Library resources, other online sources, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about finding sources.

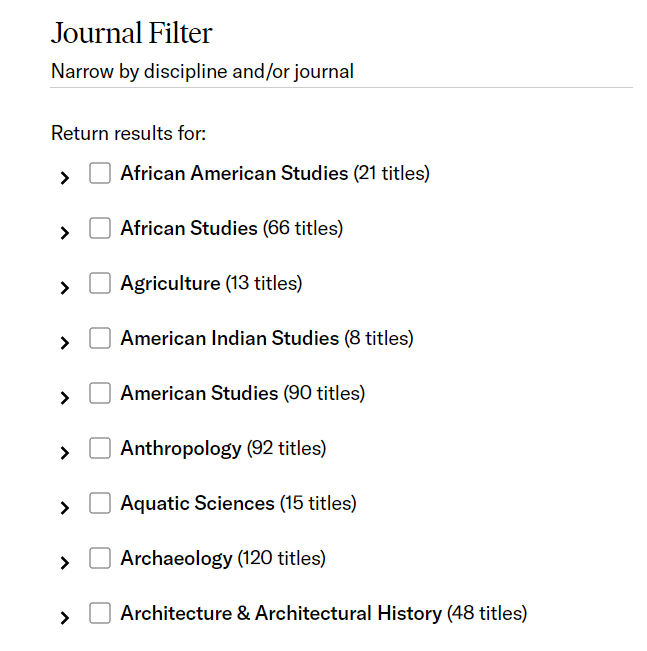

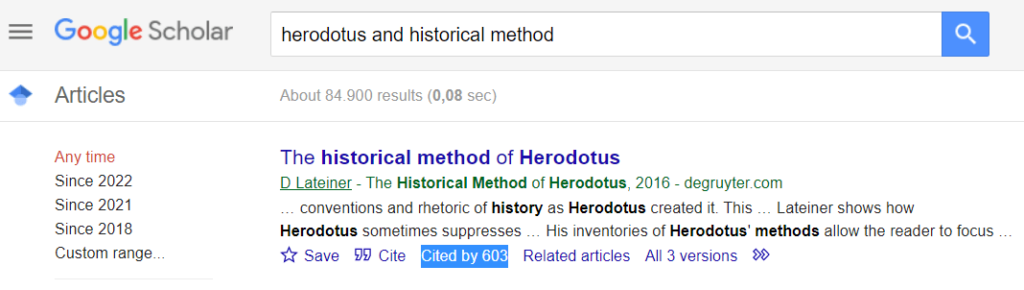

You can search for scholarly sources online using databases and search engines like Google Scholar . These provide a range of search functions that can help you to find the most relevant sources.

If you are searching for a specific article or book, include the title or the author’s name. Alternatively, if you’re just looking for sources related to your research problem , you can search using keywords. In this case, it’s important to have a clear understanding of the scope of your project and of the most relevant keywords.

Databases can be general (interdisciplinary) or subject-specific.

- You can use subject-specific databases to ensure that the results are relevant to your field.

- When using a general database or search engine, you can still filter results by selecting specific subjects or disciplines.

Example: JSTOR discipline search filter

Check the table below to find a database that’s relevant to your research.

Google Scholar

To get started, you might also try Google Scholar , an academic search engine that can help you find relevant books and articles. Its “Cited by” function lets you see the number of times a source has been cited. This can tell you something about a source’s credibility and importance to the field.

Example: Google Scholar “Cited by” function

Boolean operators

Boolean operators can also help to narrow or expand your search.

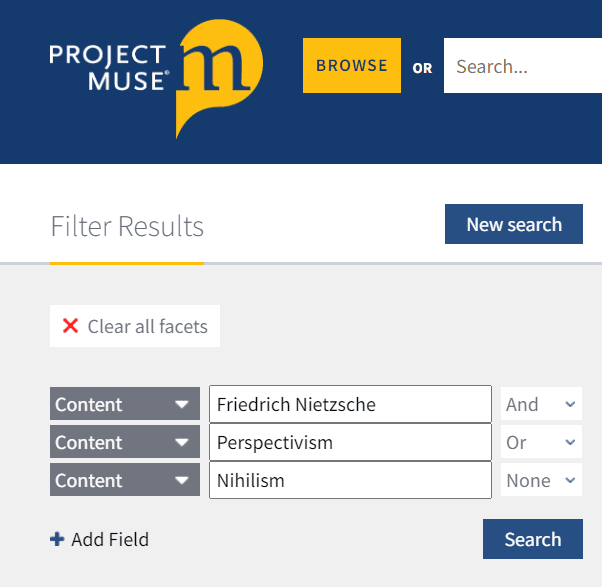

Boolean operators are words and symbols like AND , OR , and NOT that you can use to include or exclude keywords to refine your results. For example, a search for “Nietzsche NOT nihilism” will provide results that include the word “Nietzsche” but exclude results that contain the word “nihilism.”

Many databases and search engines have an advanced search function that allows you to refine results in a similar way without typing the Boolean operators manually.

Example: Project Muse advanced search

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

You can find helpful print sources in your institution’s library. These include:

- Journal articles

- Encyclopedias

- Newspapers and magazines

Make sure that the sources you consult are appropriate to your research.

You can find these sources using your institution’s library database. This will allow you to explore the library’s catalog and to search relevant keywords. You can refine your results using Boolean operators .

Once you have found a relevant print source in the library:

- Consider what books are beside it. This can be a great way to find related sources, especially when you’ve found a secondary or tertiary source instead of a primary source .

- Consult the index and bibliography to find the bibliographic information of other relevant sources.

You can consult popular online sources to learn more about your topic. These include:

- Crowdsourced encyclopedias like Wikipedia

You can find these sources using search engines. To refine your search, use Boolean operators in combination with relevant keywords.

However, exercise caution when using online sources. Consider what kinds of sources are appropriate for your research and make sure the sites are credible .

Look for sites with trusted domain extensions:

- URLs that end with .edu are educational resources.

- URLs that end with .gov are government-related resources.

- DOIs often indicate that an article is published in a peer-reviewed , scientific article.

Other sites can still be used, but you should evaluate them carefully and consider alternatives.

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

You can find sources online using databases and search engines like Google Scholar . Use Boolean operators or advanced search functions to narrow or expand your search.

For print sources, you can use your institution’s library database. This will allow you to explore the library’s catalog and to search relevant keywords.

It is important to find credible sources and use those that you can be sure are sufficiently scholarly .

- Consult your institute’s library to find out what books, journals, research databases, and other types of sources they provide access to.

- Look for books published by respected academic publishing houses and university presses, as these are typically considered trustworthy sources.

- Look for journals that use a peer review process. This means that experts in the field assess the quality and credibility of an article before it is published.

When searching for sources in databases, think of specific keywords that are relevant to your topic , and consider variations on them or synonyms that might be relevant.

Once you have a clear idea of your research parameters and key terms, choose a database that is relevant to your research (e.g., Medline, JSTOR, Project MUSE).

Find out if the database has a “subject search” option. This can help to refine your search. Use Boolean operators to combine your keywords, exclude specific search terms, and search exact phrases to find the most relevant sources.

There are many types of sources commonly used in research. These include:

You’ll likely use a variety of these sources throughout the research process , and the kinds of sources you use will depend on your research topic and goals.

Scholarly sources are written by experts in their field and are typically subjected to peer review . They are intended for a scholarly audience, include a full bibliography, and use scholarly or technical language. For these reasons, they are typically considered credible sources .

Popular sources like magazines and news articles are typically written by journalists. These types of sources usually don’t include a bibliography and are written for a popular, rather than academic, audience. They are not always reliable and may be written from a biased or uninformed perspective, but they can still be cited in some contexts.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). How to Find Sources | Scholarly Articles, Books, Etc.. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/finding-sources/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, types of sources explained | examples & tips, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, boolean operators | quick guide, examples & tips, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

EN 101: The Process of Writing

Types of sources, reference sources, popular sources, scholarly sources.

- Evaluating Sources

- Misinformation & Disinformation

- Searching Library Databases

This page is adapted from the Introduction to Research Guide by Victoria Swanson.

Different types of sources serve different purposes in your research. You might start with a brief encyclopedia article (a reference source), then move onto a news article (a popular source), and then look for an in-depth research article (a scholarly source). This page gives definitions and examples of each source type.

A reference source gives brief information about a topic. This information might be a definition, like in a dictionary, or an overview of a subject or term, like in an encyclopedia. A reference source is useful to learn background information, understand basic ideas about a topic, or to get information like names and dates.

The library has many subject-specific reference books, both in print and online. Here are a few examples of online reference entries about college entrance exams (which is the example topic throughout this guide):

Popular sources are written for the general public, and include news media and magazines. These sources take many forms online.

The library provides full-text access to articles from many popular sources. Here are a few examples of articles from major newspapers about college entrance exams:

- Mathews, Jay. "Cure for loss of SAT/ACT tests: Stop banning high school kids from college courses." Washington Post , 12 Sept. 2021, p. NA. Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints , link.gale.com/apps/doc/A675134286/OVIC?u=caldwell&sid=bookmark-OVIC&xid=ee28802e .

- Saul, Stephanie. "Put Down Your No. 2 Pencil: SAT Will Go Digital by 2024." New York Times , 26 Jan. 2022, p. A15(L). Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints , link.gale.com/apps/doc/A690448370/OVIC?u=caldwell&sid=bookmark-OVIC&xid=6e230b54 .

Scholarly sources are also called "peer-reviewed" or "academic" sources. Academic libraries provide access to scholarly sources for students and faculty.

Here are examples of academic articles about college entrance exams:

- Fina, Anthony D., et al. “Establishing Empirical Links between High School Assessments and College Outcomes: An Essential Requirement for College Readiness Interpretations.” Educational Assessment , vol. 23, no. 3, July 2018, pp. 157–72. EBSCOhost , https://caldwell.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=131170345&site=ehost-live .

- Rodriguez, Awilda. “Inequity by Design? Aligning High School Math Offerings and Public Flagship College Entrance Requirements.” Journal of Higher Education , vol. 89, no. 2, Feb. 2018, pp. 153–83. EBSCOhost , https://caldwell.idm.oclc.org/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=127841710&site=ehost-live .

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Evaluating Sources >>

- Last Updated: Feb 12, 2024 2:38 PM

- URL: https://libguides.caldwell.edu/EN101

Types of Sources: Scholarly Journals

- Types of Sources Overview

- Books and eBooks

- Encyclopedias

- Trade Journals

- Scholarly Journals

- Conference Proceedings

- Technical Reports

- Government Data and Reports

About Scholarly Journals

Journal articles are written by scholars in an academic or professional field. An editorial board reviews articles to decide whether they should be published. Journal articles may cover very specific topics or narrow fields of research.

Use a journal:

- when doing scholarly research

- to find out what has been studied on your topic

- to find bibliographies that point to other relevant research

Characteristics of Scholarly Journals

Authors are:

scholars in the field, academics or researchers.

Sources are:

always cited with many references and/or footnotes.

Articles are:

long with sections such as abstract, literature review, methodology, results and conclusion.

Examples of Scholarly Journals

- Journal of Communication

- Journal of Business Research

- Journal of Cleaner Production

Find Scholarly Journals

- Use the Browzine to find scholarly journals by title.

- Within WPI Library Search, limit to Peer-reviewed Journals.

A powerful search tool to streamline your library research. Entering terms into a single search box yields results that include: books and e-books, research and news articles, project reports, electronic theses and dissertations, archival materials, patents, open access collections and more.

Full text: Yes

Peer Reviewed or Refeered

How to Cite

Example electronic journal with DOI reference citation in American Psychological Association (APA) style:

Wang, Z., Zhang, B., Yin, J. and Zhang, X. (2011). Willingness and behavior towards e-waste recycling for residents in Beijing City, China. Journal of Cleaner Production, 19 (9-10) , 977-984. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.09.016

For information on additional citation styles, please see the Citing Sources guide.

- << Previous: Magazines

- Next: Conference Proceedings >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 11:17 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wpi.edu/sourcetypes

How can we help?

- [email protected]

- Consultation

- 508-831-5410

Module: Evaluating Sources

Types of sources, learning objective.

- Differentiate types of sources

It is probably an oversimplification to boil research sources down to three categories. But, for the work you’re doing now, this taxonomy for identifying sources makes sense. As you move through the content and practice activities on this page, think about how this method of differentiating sources aligns to your own experience with research.

Is a “print” source always on paper when you receive it? Well, not really. Digital databases and the internet have made the line between “print” and “online” sources more gray than you might expect. A good rule to follow when thinking about whether a source is “print” or “online” is to look at the original intended method of delivery. The New York Times is a print newspaper, even if many of its readers receive its content online. In addition to the fact that an interested reader can actually purchase a physical copy of any given day’s New York Times , its organizational structure is that of a print newspaper.

The same thing is true for academic journals and articles. For the most part, you will access academic journal articles from online databases through your university library or with tools like Google Scholar. Most of these journal articles are delivered to you in PDF format: PDF is a filename extension for Portable Document Format. It’s one of the closest digital file formats to “print.” Thus, academic journal articles are almost always considered “print” sources. In many style guides, you would cite an academic journal that you viewed from a PDF the same as you would if you were citing the same article from a bound journal in your hands.

Unfortunately, identifying what is and isn’t a print source is not always so easy. Take, for instance, The Huffington Post. In many ways, its website is similar to that of the New York Times . However, The Huffington Post has always been completely online. A print copy of the Post has never existed. Beyond that, though, if you take time to examine its organizational structure, the way it publishes and vets content, and the overall scope of Huffington Post , it’s clear that it is much more like Buzzfeed than The New York Times . That doesn’t mean it’s a bad source, by the way. Buzzfeed has won Pulitzer Prizes for some of its journalism. But you can’t call it a print source, and you probably can’t call The Huffington Post a print source either.

On the other side of the campus fence are online-only academic journals. These journals, like Kairos , are peer-reviewed, respected academic journals: Publishing an article in Kairos would be just as credible and noteworthy as publishing an article in Computers and Writing , a traditional print journal. So is Kairos a print source? Probably not. But it is a scholarly source. Remember that it’s always a good idea to look at a source through both lenses: scholarly vs. non-scholarly and print vs. online vs. multimedia.

- Journal Articles

- Magazine Articles

- White Papers

- Traditional Encyclopedias (like Encyclopedia Britannica )

Are all online sources bad? Is Wikipedia destroying legitimate research? Should you monkishly eschew all rooms with available WiFi when doing your research? Of course not, on all three accounts. Online sources have their place, and there are good online sources and bad online sources.

What are some online sources that might be useful in your research process? Here are a few examples:

- Government information or statistics

- Company financial reporting data

- Blogs by public figures

- Websites of businesses or organizations

- Online magazines or newspapers

- Discussion boards or forums

- Wiki-style encyclopedias (like Wookiepedia )

- Online academic journals

- Online academic monographs (books)

The quality of these sources can vary widely. You should carefully evaluate all online sources for credibility and relevance. You’ll learn the methods of evaluating an online source later in the module.

What do we mean by “multimedia” sources? Well, basically anything that doesn’t fit neatly into the category of “print” or “online” lands here. Depending upon the nature of your project, you may need to use videos, photographs, podcasts, or even songs as sources. As the researcher, you have the responsibility of vetting these sources, just as you would a website or a book. Sometimes multimedia sources can lead to vibrant and engaging research, so you should not discount their usefulness.

What are some typical multimedia sources that you might look for? Here are a few examples:

- Documentaries on Netflix

- Interviews of public officials on YouTube

- Podcasts about current events

- Photo essays on the New York Times website

- Raw video of events broadcasted to Facebook Live

Contribute!

Improve this page Learn More

- Types of Sources. Provided by : University of Mississippi. Project : PLATO Project. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- How-To Guides

Types of Sources

Related guides.

- Scholarly vs. Popular

- Peer Review

- Choosing Keywords

- What to Put in a Search Box

- Thesis Statements

Other Specialized Sources

- Biographies

- Government Information

- Images & Videos

- Primary vs Secondary

- Archives & Special Collections

Information can come from virtually anywhere — media, blogs, personal experiences, books, journal and magazine articles, expert opinions, encyclopedias, web pages, and more — and the type of source(s) you need for your assignments will change depending on the question you are trying to answer.

The Consortium Library provides free access to these types of sources for the UAA and APU communities and to in-person library visitors:

Scholarly Journals

Trade publications.

- Dissertations

QuickSearch

Library catalog, encyclopedias.

- Websites & Search Engines

For other specialized sources, follow links to related guides on the left.

Scholarly (or academic) journals contain articles written by researchers who are experts in their field. Authors are usually employed by colleges, universities, or other institutions of education or research. Articles are submitted to the editors of the journals who decide whether or not to publish. The most prestigious journals use the peer review process. In this process, an article is reviewed by experts in the field (peers) who suggest changes and recommend whether the article should be published.

For help identifying different kinds of magazines and journals, see the Scholarly vs Popular guide.

- for scholarly research.

- to explore research that has been done on your topic.

- to find citations and references that point to other relevant articles.

- Contemporary Accounting Research

- Journal of Morphology

- Psychological Review

Magazines contain articles written by people who are usually employed by the publication for which they write. They cover news and current events, profiles of people or places, and/or political opinions.

- to find information or opinions about popular culture.

- to find up-to-date information about current events.

- to find general articles intended for people who are not experts on a topic.

- National Geographic

- Psychology Today

- Rolling Stone

Trade and professional publications contain articles written by people working in a specific discipline, industry, or field of work. Articles focus on news in the field, brief reports on research, and opinions about trends and events.

- to learn more about your topic as it relates to a discipline, industry, or field of work.

- for explanation and interpretation of relevant research.

- to find out what's happening in a discipline, industry, or field of work.

- to identify relevant professional associations.

- Advertising Age

- Professional Pilot

- Public Manager

Dissertations & Theses

Dissertations and theses are lengthy works completed in pursuit of a university degree or professional qualification that present an author’s original research or creative work. A dissertation is typically part of doctoral or PhD studies, while a thesis is generally part of a master's degree.

Dissertations and theses are scholarly sources because they are supervised by a committee of scholars or a faculty supervisor. However, they are not peer reviewed in the same way as a peer-reviewed journal. If you are required to use peer-reviewed sources, ask your instructor if you can use a dissertation or thesis.

- to read a comprehensive literature review on a topic.

- to explore research on a topic, sometimes the only thing written about a narrow topic.