Building Resilient Education Systems: Evidence from Large-Scale Randomized Trials in Five Countries

Education systems need to withstand frequent shocks, including conflict, disease, natural disasters, and climate events, all of which routinely close schools. During these emergencies, alternative models are needed to deliver education. However, rigorous evaluation of effective educational approaches in these settings is challenging and rare, especially across multiple countries. We present results from large-scale randomized trials evaluating the provision of education in emergency settings across five countries: India, Kenya, Nepal, Philippines, and Uganda. We test multiple scalable models of remote instruction for primary school children during COVID-19, which disrupted education for over 1 billion schoolchildren worldwide. Despite heterogeneous contexts, results show that the effectiveness of phone call tutorials can scale across contexts. We find consistently large and robust effect sizes on learning, with average effects of 0.30-0.35 standard deviations. These effects are highly cost-effective, delivering up to four years of high-quality instruction per $100 spent, ranking in the top percentile of education programs and policies. In a subset of trials, we randomized whether the intervention was provided by NGO instructors or government teachers. Results show similar effects, indicating scalability within government systems. These results reveal it is possible to strengthen the resilience of education systems, enabling education provision amidst disruptions, and to deliver cost-effective learning gains across contexts and with governments.

We are grateful to an incredible coalition of partners who enabled this multi-country response. Implementing and research partners include: Youth Impact, J-PAL, Learning Collider (supported by Schmidt Futures and Citadel), Oxford University, World Bank, Ministry of Education, Science and Technology of Nepal, Teach for Nepal, Street Child, Department of Education in the Philippines, IPA, Building Tomorrow, NewGlobe, Alokit, and Global School Leaders. Funding partners include UBS Optimus Foundation, Mulago Foundation, Douglas B. Marshall Foundation, Echidna Giving, Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Jacobs Foundation, JPAL Innovation in Government Initiative, Northwestern’s ‘Economics of Nonprofits’ class, the Peter Cundill Foundation, and the World Bank. Cullen received funding from the UKRI GCRF & Oxford’s OPEN Fellowship. We thank Natasha Ahuja, Amy Jung, and Rachel Zhou who provided excellent research assistance. Special thank you to implementation and research teams including Nassreena Baddiri, Mariel Bayangos, Kshitiz Basnet, John Lawrence Carandang, Clotilde de Maricourt, Pratik Ghimire, Faith Karanja, Manoj Karki, Karisha Cruz, Usha Limbu, Roger Masapol, Edward Munyaneza, Sunil Poudel, Karthika Radhakrishnan-Nair, Pratigya Regmi, Uttam Sharma, Swastika Shrestha, and Kishor Subedi. Thank you for thoughtful comments from participants of various seminars and conferences: ASSA, BREAD, CSAE, NEUDC, PacDev. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

- Our Mission

The 10 Most Significant Education Studies of 2021

From reframing our notion of “good” schools to mining the magic of expert teachers, here’s a curated list of must-read research from 2021.

It was a year of unprecedented hardship for teachers and school leaders. We pored through hundreds of studies to see if we could follow the trail of exactly what happened: The research revealed a complex portrait of a grueling year during which persistent issues of burnout and mental and physical health impacted millions of educators. Meanwhile, many of the old debates continued: Does paper beat digital? Is project-based learning as effective as direct instruction? How do you define what a “good” school is?

Other studies grabbed our attention, and in a few cases, made headlines. Researchers from the University of Chicago and Columbia University turned artificial intelligence loose on some 1,130 award-winning children’s books in search of invisible patterns of bias. (Spoiler alert: They found some.) Another study revealed why many parents are reluctant to support social and emotional learning in schools—and provided hints about how educators can flip the script.

1. What Parents Fear About SEL (and How to Change Their Minds)

When researchers at the Fordham Institute asked parents to rank phrases associated with social and emotional learning , nothing seemed to add up. The term “social-emotional learning” was very unpopular; parents wanted to steer their kids clear of it. But when the researchers added a simple clause, forming a new phrase—”social-emotional & academic learning”—the program shot all the way up to No. 2 in the rankings.

What gives?

Parents were picking up subtle cues in the list of SEL-related terms that irked or worried them, the researchers suggest. Phrases like “soft skills” and “growth mindset” felt “nebulous” and devoid of academic content. For some, the language felt suspiciously like “code for liberal indoctrination.”

But the study suggests that parents might need the simplest of reassurances to break through the political noise. Removing the jargon, focusing on productive phrases like “life skills,” and relentlessly connecting SEL to academic progress puts parents at ease—and seems to save social and emotional learning in the process.

2. The Secret Management Techniques of Expert Teachers

In the hands of experienced teachers, classroom management can seem almost invisible: Subtle techniques are quietly at work behind the scenes, with students falling into orderly routines and engaging in rigorous academic tasks almost as if by magic.

That’s no accident, according to new research . While outbursts are inevitable in school settings, expert teachers seed their classrooms with proactive, relationship-building strategies that often prevent misbehavior before it erupts. They also approach discipline more holistically than their less-experienced counterparts, consistently reframing misbehavior in the broader context of how lessons can be more engaging, or how clearly they communicate expectations.

Focusing on the underlying dynamics of classroom behavior—and not on surface-level disruptions—means that expert teachers often look the other way at all the right times, too. Rather than rise to the bait of a minor breach in etiquette, a common mistake of new teachers, they tend to play the long game, asking questions about the origins of misbehavior, deftly navigating the terrain between discipline and student autonomy, and opting to confront misconduct privately when possible.

3. The Surprising Power of Pretesting

Asking students to take a practice test before they’ve even encountered the material may seem like a waste of time—after all, they’d just be guessing.

But new research concludes that the approach, called pretesting, is actually more effective than other typical study strategies. Surprisingly, pretesting even beat out taking practice tests after learning the material, a proven strategy endorsed by cognitive scientists and educators alike. In the study, students who took a practice test before learning the material outperformed their peers who studied more traditionally by 49 percent on a follow-up test, while outperforming students who took practice tests after studying the material by 27 percent.

The researchers hypothesize that the “generation of errors” was a key to the strategy’s success, spurring student curiosity and priming them to “search for the correct answers” when they finally explored the new material—and adding grist to a 2018 study that found that making educated guesses helped students connect background knowledge to new material.

Learning is more durable when students do the hard work of correcting misconceptions, the research suggests, reminding us yet again that being wrong is an important milestone on the road to being right.

4. Confronting an Old Myth About Immigrant Students

Immigrant students are sometimes portrayed as a costly expense to the education system, but new research is systematically dismantling that myth.

In a 2021 study , researchers analyzed over 1.3 million academic and birth records for students in Florida communities, and concluded that the presence of immigrant students actually has “a positive effect on the academic achievement of U.S.-born students,” raising test scores as the size of the immigrant school population increases. The benefits were especially powerful for low-income students.

While immigrants initially “face challenges in assimilation that may require additional school resources,” the researchers concluded, hard work and resilience may allow them to excel and thus “positively affect exposed U.S.-born students’ attitudes and behavior.” But according to teacher Larry Ferlazzo, the improvements might stem from the fact that having English language learners in classes improves pedagogy , pushing teachers to consider “issues like prior knowledge, scaffolding, and maximizing accessibility.”

5. A Fuller Picture of What a ‘Good’ School Is

It’s time to rethink our definition of what a “good school” is, researchers assert in a study published in late 2020. That’s because typical measures of school quality like test scores often provide an incomplete and misleading picture, the researchers found.

The study looked at over 150,000 ninth-grade students who attended Chicago public schools and concluded that emphasizing the social and emotional dimensions of learning—relationship-building, a sense of belonging, and resilience, for example—improves high school graduation and college matriculation rates for both high- and low-income students, beating out schools that focus primarily on improving test scores.

“Schools that promote socio-emotional development actually have a really big positive impact on kids,” said lead researcher C. Kirabo Jackson in an interview with Edutopia . “And these impacts are particularly large for vulnerable student populations who don’t tend to do very well in the education system.”

The findings reinforce the importance of a holistic approach to measuring student progress, and are a reminder that schools—and teachers—can influence students in ways that are difficult to measure, and may only materialize well into the future.

6. Teaching Is Learning

One of the best ways to learn a concept is to teach it to someone else. But do you actually have to step into the shoes of a teacher, or does the mere expectation of teaching do the trick?

In a 2021 study , researchers split students into two groups and gave them each a science passage about the Doppler effect—a phenomenon associated with sound and light waves that explains the gradual change in tone and pitch as a car races off into the distance, for example. One group studied the text as preparation for a test; the other was told that they’d be teaching the material to another student.

The researchers never carried out the second half of the activity—students read the passages but never taught the lesson. All of the participants were then tested on their factual recall of the Doppler effect, and their ability to draw deeper conclusions from the reading.

The upshot? Students who prepared to teach outperformed their counterparts in both duration and depth of learning, scoring 9 percent higher on factual recall a week after the lessons concluded, and 24 percent higher on their ability to make inferences. The research suggests that asking students to prepare to teach something—or encouraging them to think “could I teach this to someone else?”—can significantly alter their learning trajectories.

7. A Disturbing Strain of Bias in Kids’ Books

Some of the most popular and well-regarded children’s books—Caldecott and Newbery honorees among them—persistently depict Black, Asian, and Hispanic characters with lighter skin, according to new research .

Using artificial intelligence, researchers combed through 1,130 children’s books written in the last century, comparing two sets of diverse children’s books—one a collection of popular books that garnered major literary awards, the other favored by identity-based awards. The software analyzed data on skin tone, race, age, and gender.

Among the findings: While more characters with darker skin color begin to appear over time, the most popular books—those most frequently checked out of libraries and lining classroom bookshelves—continue to depict people of color in lighter skin tones. More insidiously, when adult characters are “moral or upstanding,” their skin color tends to appear lighter, the study’s lead author, Anjali Aduki, told The 74 , with some books converting “Martin Luther King Jr.’s chocolate complexion to a light brown or beige.” Female characters, meanwhile, are often seen but not heard.

Cultural representations are a reflection of our values, the researchers conclude: “Inequality in representation, therefore, constitutes an explicit statement of inequality of value.”

8. The Never-Ending ‘Paper Versus Digital’ War

The argument goes like this: Digital screens turn reading into a cold and impersonal task; they’re good for information foraging, and not much more. “Real” books, meanwhile, have a heft and “tactility” that make them intimate, enchanting—and irreplaceable.

But researchers have often found weak or equivocal evidence for the superiority of reading on paper. While a recent study concluded that paper books yielded better comprehension than e-books when many of the digital tools had been removed, the effect sizes were small. A 2021 meta-analysis further muddies the water: When digital and paper books are “mostly similar,” kids comprehend the print version more readily—but when enhancements like motion and sound “target the story content,” e-books generally have the edge.

Nostalgia is a force that every new technology must eventually confront. There’s plenty of evidence that writing with pen and paper encodes learning more deeply than typing. But new digital book formats come preloaded with powerful tools that allow readers to annotate, look up words, answer embedded questions, and share their thinking with other readers.

We may not be ready to admit it, but these are precisely the kinds of activities that drive deeper engagement, enhance comprehension, and leave us with a lasting memory of what we’ve read. The future of e-reading, despite the naysayers, remains promising.

9. New Research Makes a Powerful Case for PBL

Many classrooms today still look like they did 100 years ago, when students were preparing for factory jobs. But the world’s moved on: Modern careers demand a more sophisticated set of skills—collaboration, advanced problem-solving, and creativity, for example—and those can be difficult to teach in classrooms that rarely give students the time and space to develop those competencies.

Project-based learning (PBL) would seem like an ideal solution. But critics say PBL places too much responsibility on novice learners, ignoring the evidence about the effectiveness of direct instruction and ultimately undermining subject fluency. Advocates counter that student-centered learning and direct instruction can and should coexist in classrooms.

Now two new large-scale studies —encompassing over 6,000 students in 114 diverse schools across the nation—provide evidence that a well-structured, project-based approach boosts learning for a wide range of students.

In the studies, which were funded by Lucas Education Research, a sister division of Edutopia , elementary and high school students engaged in challenging projects that had them designing water systems for local farms, or creating toys using simple household objects to learn about gravity, friction, and force. Subsequent testing revealed notable learning gains—well above those experienced by students in traditional classrooms—and those gains seemed to raise all boats, persisting across socioeconomic class, race, and reading levels.

10. Tracking a Tumultuous Year for Teachers

The Covid-19 pandemic cast a long shadow over the lives of educators in 2021, according to a year’s worth of research.

The average teacher’s workload suddenly “spiked last spring,” wrote the Center for Reinventing Public Education in its January 2021 report, and then—in defiance of the laws of motion—simply never let up. By the fall, a RAND study recorded an astonishing shift in work habits: 24 percent of teachers reported that they were working 56 hours or more per week, compared to 5 percent pre-pandemic.

The vaccine was the promised land, but when it arrived nothing seemed to change. In an April 2021 survey conducted four months after the first vaccine was administered in New York City, 92 percent of teachers said their jobs were more stressful than prior to the pandemic, up from 81 percent in an earlier survey.

It wasn’t just the length of the work days; a close look at the research reveals that the school system’s failure to adjust expectations was ruinous. It seemed to start with the obligations of hybrid teaching, which surfaced in Edutopia ’s coverage of overseas school reopenings. In June 2020, well before many U.S. schools reopened, we reported that hybrid teaching was an emerging problem internationally, and warned that if the “model is to work well for any period of time,” schools must “recognize and seek to reduce the workload for teachers.” Almost eight months later, a 2021 RAND study identified hybrid teaching as a primary source of teacher stress in the U.S., easily outpacing factors like the health of a high-risk loved one.

New and ever-increasing demands for tech solutions put teachers on a knife’s edge. In several important 2021 studies, researchers concluded that teachers were being pushed to adopt new technology without the “resources and equipment necessary for its correct didactic use.” Consequently, they were spending more than 20 hours a week adapting lessons for online use, and experiencing an unprecedented erosion of the boundaries between their work and home lives, leading to an unsustainable “always on” mentality. When it seemed like nothing more could be piled on—when all of the lights were blinking red—the federal government restarted standardized testing .

Change will be hard; many of the pathologies that exist in the system now predate the pandemic. But creating strict school policies that separate work from rest, eliminating the adoption of new tech tools without proper supports, distributing surveys regularly to gauge teacher well-being, and above all listening to educators to identify and confront emerging problems might be a good place to start, if the research can be believed.

Generative Artificial Intelligence in education: Think piece by Stefania Giannini

Artificial Intelligence tools open new horizons for education, but we urgently need to take action to ensure we integrate them into learning systems on our terms. That is the core message of UNESCO’s new paper on generative AI and the future of education . In her think piece, UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Education, Stefania Giannini expresses her concerns that the checks and balances applied to teaching materials are not being used to the implementation of generative AI. While highlighting that AI tools create new prospects for learning, she underscores that regulations can only be built once the proper research has been conducted.

Readiness of schools to regulate the use of AI tools in education

In May, a UNESCO global survey of over 450 schools and universities found that fewer than 10% have developed institutional policies and/or formal guidance concerning the use of generative AI applications. The paper observes that in most countries, the time, steps and authorizations needed to validate a new textbook far surpass those required to move generative AI utilities into schools and classrooms. Textbooks are usually evaluated for accuracy of content, age-appropriateness, relevance of teaching and accuracy of content, cultural and social suitability which encompasses checks to protect against bias, before being used in the classroom.

Education systems must set own rules

The education sector cannot rely on the corporate creators of AI to regulate its own work. To vet and validate new and complex AI applications for formal use in school, UNESCO recommends that ministries of education build their capacities in coordination with other regulatory branches of government, in particular those regulating technologies.

Potential to undermine the status of teachers and the necessity of schools

The paper underscores that education should remain a deeply human act rooted in social interaction. It recalls that during the COVID-19 pandemic, when digital technology became the primary medium for education, students suffered both academically and socially. The paper warns us that generative AI in particular has the potential to both undermine the authority and status of teachers, and to strengthen calls for further automation of education: Teacher-less schools, and school-less education. It emphasizes that well-run schools, coupled with sufficient teacher numbers, training and salaries must be prioritized.

Education spending must focus on fundamental learning objectives

The paper argues that investment in schools and teachers, is the only way to solve the problem that today, at the dawn of the AI Era, 244 million children and youth are out of school and more than 770 million people are non-literate. Evidence shows that good schools and teachers can resolve this persistent educational challenge – yet the world continues to underfund them.

UNESCO’s response to generative AI in education

UNESCO is steering the global dialogue with policy-makers, EdTech partners, academia and civil society. The first global meeting of Ministers of Education took place in May 2023 and the Organization is developing policy guidelines on the use of generative AI in education and research, as well as frameworks of AI competencies for students and teachers for school education. These will be launched during the Digital Learning Week , which will take place at UNESCO Headquarters in Paris on 4-7 September 2023. The UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report 2023 to be published on 26 July 2023 will focus on the use of technology in education.

UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence

UNESCO produced the first-ever global standard on AI ethics – the ‘Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence’ in November 2021. This framework was adopted by all 193 Member States. The Recommendation stresses that governments must ensure that AI always adheres to the principles of safety, inclusion, diversity, transparency and quality.

Related items

- Artificial intelligence

- Future of education

- Educational technology

- Digital learning week

- Educational trends

- Topics: Display

- See more add

Other recent idea

Read our research on: Abortion | International Conflict | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

6. teachers’ views on the state of public k-12 education.

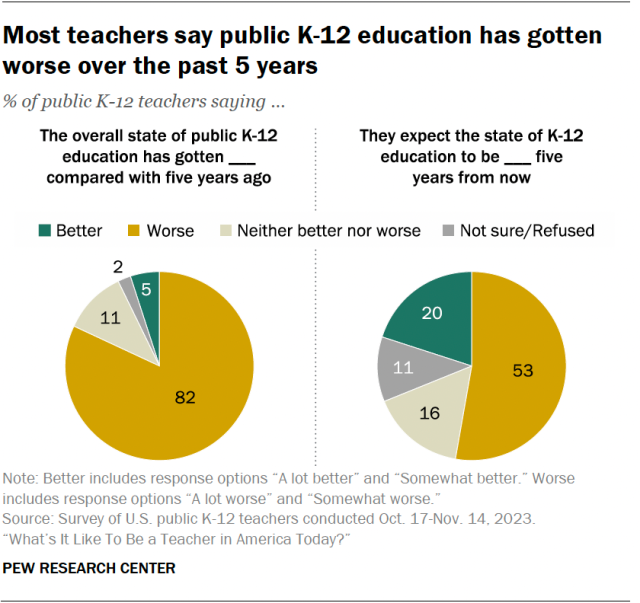

Overall, teachers have a negative view of the U.S. K-12 education system – both the path it’s been on in recent years and what its future might hold.

The vast majority of teachers (82%) say that the overall state of public K-12 education has gotten worse in the last five years. Only 5% say it’s gotten better, and 11% say it has gotten neither better nor worse.

Looking to the future, 53% of teachers expect the state of public K-12 education to be worse five years from now. One-in-five say it will get better, and 16% expect it to be neither better nor worse.

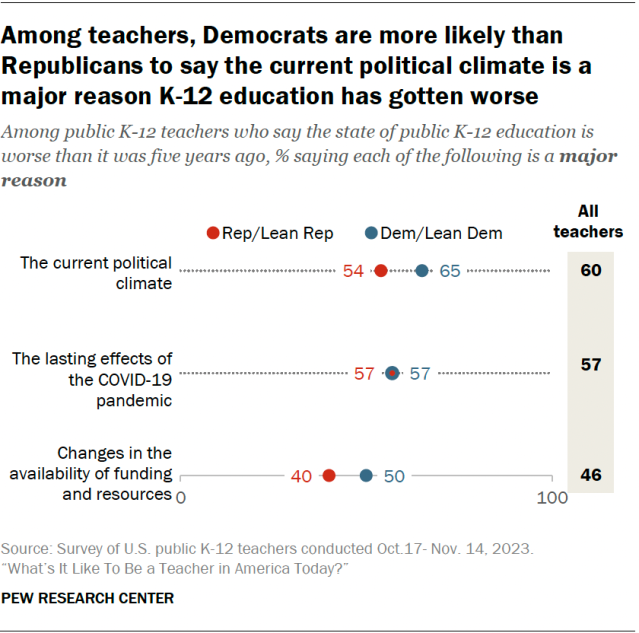

We asked teachers who say the state of public K-12 education is worse now than it was five years ago how much each of the following has contributed:

- The current political climate (60% of teachers say this is a major reason that the state of K-12 education has gotten worse)

- The lasting effects of the COVID-19 pandemic (57%)

- Changes in the availability of funding and resources (46%)

Elementary school teachers are especially likely to point to resource issues – 54% say changes in the availability of funding and resources is a major reason the K-12 education system is worse now. By comparison, 41% of middle school and 39% of high school teachers say the same.

Differences by party

Overall, teachers who are Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are as likely as Republican and Republican-leaning teachers to say that the state of public K-12 education is worse than it was five years ago.

But Democratic teachers are more likely than Republican teachers to point to the current political climate (65% vs. 54%) and changes in the availability of funding and resources (50% vs. 40%) as major reasons.

Democratic and Republican teachers are equally likely to say that lasting effects of the pandemic are a major reason that the public K-12 education is worse than it was five years ago (57% each).

K-12 education and political parties

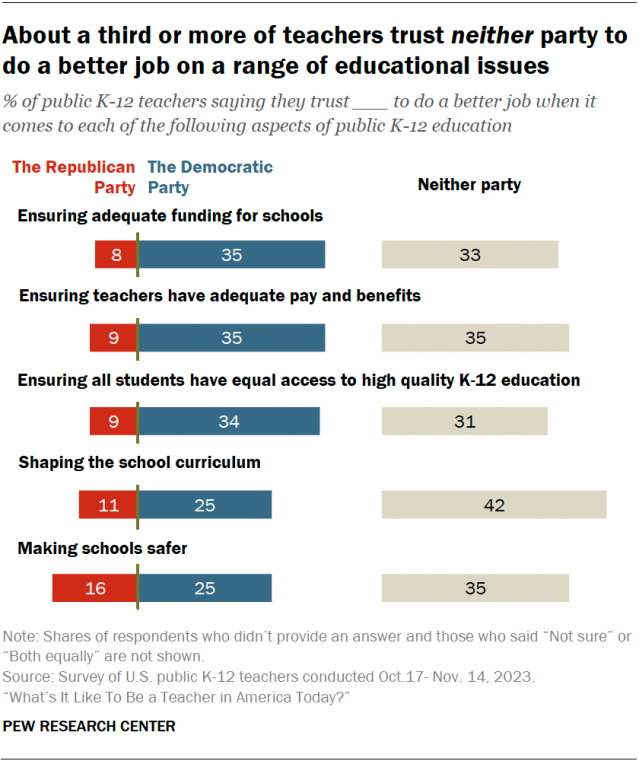

We asked teachers which political party they trust to do a better job on various aspects of public K-12 education.

Across each of the issues we asked about, roughly a third or more of teachers say they don’t trust either party to do a better job. In particular, a sizable share (42%) trust neither party when it comes to shaping the school curriculum.

On balance, more teachers say they trust the Democratic Party to do a better job handling the things we asked about than say they trust the Republican Party.

About a third of teachers say they trust the Democratic Party to do a better job in ensuring adequate funding for schools, adequate pay and benefits for teachers, and equal access to high quality K-12 education for students. Only about one-in-ten teachers say they trust the Republican Party to do a better job in these areas.

A quarter of teachers say they trust the Democratic Party to do a better job in shaping the school curriculum and making schools safer; 11% and 16% of teachers, respectively, say they trust the Republican Party in these areas.

Across all the items we asked about, shares ranging from 15% to 17% say they are not sure which party they trust more, and shares ranging from 4% to 7% say they trust both parties equally.

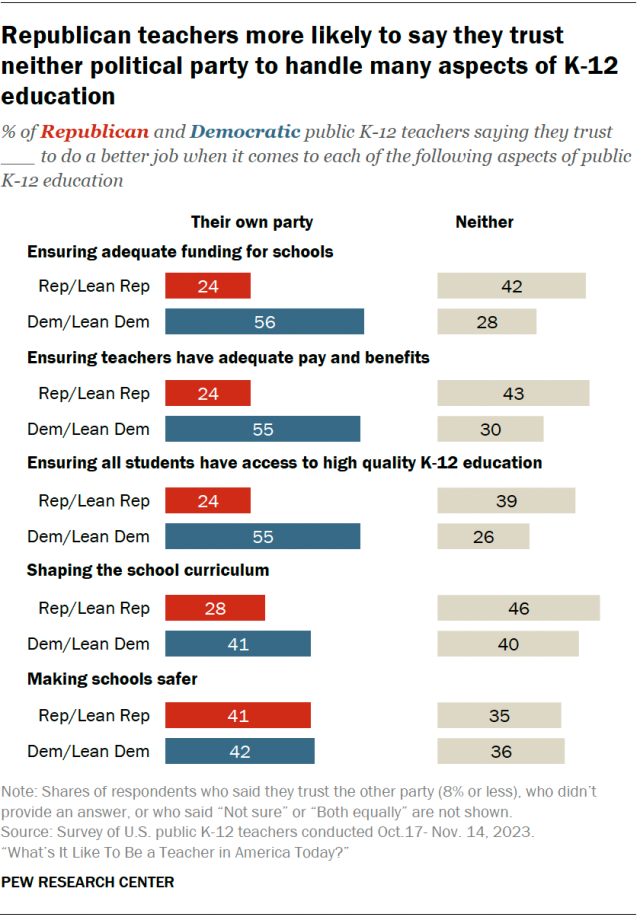

A majority of public K-12 teachers (58%) identify with or lean toward the Democratic Party. About a third (35%) identify with or lean toward the GOP.

For each aspect of the education system we asked about, both Democratic and Republican teachers are more likely to say they trust their own party to do a better job than to say they trust the other party.

However, across most of these areas, Republican teachers are more likely to say they trust neither party than to say they trust their own party.

For example, about four-in-ten Republican teachers say they trust neither party when it comes to ensuring adequate funding for schools and equal access to high quality K-12 education for students. Only about a quarter of Republican teachers say they trust their own party on these issues.

The noteworthy exception is making schools safer, where similar shares of Republican teachers trust their own party (41%) and neither party (35%) to do a better job.

Social Trends Monthly Newsletter

Sign up to to receive a monthly digest of the Center's latest research on the attitudes and behaviors of Americans in key realms of daily life

Report Materials

Table of contents, ‘back to school’ means anytime from late july to after labor day, depending on where in the u.s. you live, among many u.s. children, reading for fun has become less common, federal data shows, most european students learn english in school, for u.s. teens today, summer means more schooling and less leisure time than in the past, about one-in-six u.s. teachers work second jobs – and not just in the summer, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Implementing school-based assessment reforms to enhance student learning: a systematic review

- Published: 18 October 2023

- Volume 36 , pages 7–30, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Cherry Zin Oo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3227-8010 1 ,

- Dennis Alonzo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8900-497X 2 ,

- Ria Asih ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9144-3357 3 ,

- Giovanni Pelobillo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8725-258X 4 ,

- Rex Lim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2980-5342 5 ,

- Nang Mo Hline San ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1396-9147 6 &

- Sue O’Neill ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2616-4404 2

335 Accesses

Explore all metrics

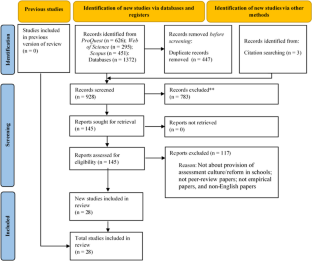

Viewpoints on different assessment systems used in many educational bureaucracies are diverse and continually evolving. Schools are tasked with translating those reforms’ philosophies and principles into school-based assessment practices. However, it is unclear from research evidence what approach and factors best support the implementation of assessment reforms. To guide school leaders to design and implement school-based assessment reforms, there is a need to develop coherent knowledge of how school-based assessment reforms are implemented. We reviewed the literature on school-based assessment reforms using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. From a synthesis of the 28 articles included, we reported what approaches are used to implement assessment reforms and what factors influenced their implementation. Furthermore, we have proposed a framework that defines the political, cultural, structural, chronological, paradigmatic, and technological perspectives that need careful attention when implementing assessment reforms in schools.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Formative Assessment Policy and Its Enactment in the Philippines

Chinese EFL Students’ Response to an Assessment Policy Change

Curriculum and Policy Reform Impacts on Teachers’ Assessment Learning: A South African Perspective

Data availability.

The manuscript has no associated data as this is a review paper.

Adie, L., Addison, B., & Lingard, B. (2021). Assessment and learning: An in-depth analysis of change in one school’s assessment culture. Oxford Review of Education, 47 (3), 404–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1850436

Article Google Scholar

Alonzo, D., Labad, V., Bejano, J., & Guerra, F. (2021a). The policy-driven dimensions of teacher beliefs about assessment. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46 (3), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2021v46n3.3

Alonzo, D., Leverett, J., & Obsioma, E. (2021b). Leading an assessment reform: Ensuring a whole-school approach for decision-making. Frontiers in Education , 6 . https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.631857

Arrafii, M. A. (2021). Assessment reform in Indonesia: Contextual barriers and opportunities for implementation. Asia Pacific Journal of Education , 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2021.1898931

Assessment Reform Group. (2002). Assessment for learning: 10 principles . Nuffield Foundation. http://www.assessment-reform-group.org.uk . Accessed 5 Aug 2016

Bansilal, S. (2011). Assessment reform in South Africa: Opening up or closing spaces for teachers. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 78 (1), 91–107.

Birenbaum, M., DeLuca, C., Earl, L., Heritage, M., Klenowski, V., Looney, A., Smith, K., Timperley, H., Volante, L., & Wyatt-Smith, C. (2015). International trends in the implementation of assessment for learning: Implications for policy and practice. Policy Futures in Education, 13 (1), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210314566733

Birenbaum, M. (2016). Assessment culture versus testing culture: The impact on assessment for learning. In D. Laveault & L. Allal (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 275–292). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39211-0_16

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80 (2), 139–148.

Google Scholar

Carless, D. (2005). Prospects for the implementation of assessment for learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 12 (1), 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594042000333904

Chetcuti, D., & Cutajar, C. (2014). Implementing peer assessment in a post-secondary (16–18) physics classroom. International Journal of Science Education, 36 (18), 3101–3124. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2014.953621

Article ADS Google Scholar

Chirwa, G. W., & Naidoo, D. (2015). Continuous assessment in expressive arts in Malawian primary schools. The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning, 10 (1), 127–140.

Choi, J. (2017). Understanding elementary teachers’ different responses to reform: The case of implementation of an assessment reform in South Korea. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 9 (3), 581–598.

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Cimer, S. O. (2017). What makes a change unsuccessful through the eyes of teachers. International Education Studies, 11 (1), 81. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v11n1p81

Clement, J. (2014). Managing mandated educational change. School Leadership & Management, 34 (1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2013.813460

Crooks, T. J. (1988). The impact of classroom evaluation practices on students. Review of Educational Research, 58 , 438–481.

Duncan, C. R., & Noonan, B. (2007). Factors affecting teachers’ grading and assessment practices. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 53 (1), 1–21.

East, M. (2015). Coming to terms with innovative high-stakes assessment practice: Teachers’ viewpoints on assessment reform. Language Testing, 32 (1), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532214544393

Article MathSciNet Google Scholar

Ennis, D. (2010). Contra assessment culture. Assessment Update, 22 (2), 1–15.

Farkas, M. G. (2013). Building and sustaining a culture of assessment: Best practices for change leadership. Reference Services Review, 41 (1), 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1108/00907321311300857

Fullan, M. (2002). Principals as leaders in a culture of change, educational leadership. http://www.michaelfullan.ca/Articles_02/03_02.htm

Gipps, C. (1994). Developments in educational assessment: What makes a good test? Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 1 (3), 283–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594940010304

Hamp-Lyons, L. (1999). Implications of the “examination culture” for (English language) education in Hong Kong. In V. Crew, B. Vivien, & H. Joseph (Eds.), Exploring diversity in the lanuage curriculum (pp. 133–140). Hong Kong Institute of Education.

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school . Columbia University.

Hargreaves, A., Earl, L., & Schmidt, M. (2002). Perspectives on alternative assessment reform. American Educational Research Journal, 39 (1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312039001069

Harrison, C. J., Könings, K. D., Schuwirth, L. W. T., Wass, V., & Van der Vleuten, C. P. M. (2017). Changing the culture of assessment: The dominance of the summative assessment paradigm. BMC Medical Education, 17 (1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-017-0912-5

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analysis relating to achievement . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Heitink, M. C., Van der Kleij, F. M., Veldkamp, B. P., Schildkamp, K., & Kippers, W. B. (2016). A systematic review of prerequisites for implementing assessment for learning in classroom practice. Educational Research Review, 17 , 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.12.002

Herman, J., Osmundson, E., Dai, Y., Ringstaff, C., & Timms, M. (2015). Investigating the dynamics of formative assessment: Relationships between teacher knowledge, assessment practice and learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 22 (3), 344–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2015.1006521

Hopfenbeck, T. N., Flórez Petour, M. T., & Tolo, A. (2015). Balancing tensions in educational policy reforms: Large-scale implementation of assessment for learning in Norway. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 22 (1), 44–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.996524

Iipinge, S. M., & Kasanda, C. D. (2013). Challenges associated with curriculum alignment, change and assessment reforms in Namibia. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 20 (4), 424–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2013.839544

Jones, A., & Moreland, J. (2005). The importance of pedagogical content knowledge in assessment for learning practices: A case-study of a whole-school approach. Curriculum Journal, 16 (2), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170500136044

Jónsson, Í. R., & Geirsdóttir, G. (2020). “This school really teaches you to talk to your teachers”: Students’ experience of different assessment cultures in three Icelandic upper secondary schools. Assessment Matters , 14 , 63–88. http://repositorio.unan.edu.ni/2986/1/5624.pdf . Accessed 10 Oct 2021

Kleinsasser, A. M. (1995). Assessment culture and national testing. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 68 (4), 205–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.1995.9957233

Klenowski, V. (2009). Assessment for learning revisited: An Asia-Pacific perspective. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 16 (3), 263–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940903319646

Laveault, D., & Allal, L. (2016). Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation . Springer. http://www.springer.com/series/13204 . Accessed 6 Feb 2019

Leung, C. Y., & Andrews, S. (2012). The mediating role of textbooks in high-stakes assessment reform. ELT Journal, 66 (3), 356–365. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccs018

Miller, M. D., Linn, L. R., & Gronlund, N. (2013). Measurement and assessment in teaching (11th ed.). Pearson Edition.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., & Altman, D. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRIMSA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine , 151 (4). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

Olsen, B., & Buchanan, R. (2019). An investigation of teachers encouraged to reform grading practices in secondary schools. American Educational Research Journal, 56 (5), 2004–2039. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831219841349

Oo, C. Z. (2020). Assessment for learning literacy and pre-service teacher education: Perspectives from Myanmar [PhD thesis, The University of New South Wales (UNSW)]. http://handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/65021 . Accessed 28 Apr 2021

Petour, M. T. F. (2015). Systems, ideologies and history: A three-dimensional absence in the study of assessment reform processes. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 22 (1), 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2014.943153

Popham, W. J. (2017). Classroom assessment: What teachers need to know (8th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

Prytula, M., Noonan, B., & Hellsten, L. (2013). Toward instructional leadership: Principals’ perceptions of largescale assessment in schools. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 140 , 1–30.

Sandvik, L. V. (2019). Mapping assessment for learning (AfL) communities in schools. Assessment Matters , 13 , 6–43. https://doi.org/10.18296/am.0037

Schildkamp, K., van der Kleij, F. M., Heitink, M. C., Kippers, W. B., & Veldkamp, B. P. (2020). Formative assessment: A systematic review of critical teacher prerequisites for classroom practice. International Journal of Educational Research, 103 (April), 101602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101602

Suurtamm, C., & Koch, M. J. (2014). Navigating dilemmas in transforming assessment practices: Experiences of mathematics teachers in Ontario, Canada. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 26 (3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-014-9195-0

Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology , 45 . https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

Tong, C. S., Lee, C., & Luo, G. (2020). Assessment reform in Hong Kong: Developing the HKDSE to align with the new academic structure. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 27 (2), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2020.1732866

Torrance, H. (2007). Assessment as learning? How the use of explicit learning objectives, assessment criteria and feedback in post-secondary education and training can come to dominate learning. Assessment in Education, 14 (3), 283–294.

Towndrow, P. A. (2008). Critical reflective practice as a pivot in transforming science education: A report of teacher-researcher collaborative interactions in response to assessment reforms. International Journal of Science Education, 30 (7), 903–922. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500690701279014

Van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M., Sangari, A. A., & Veldhuis, M. (2021). Teachers’ use of descriptive assessment in primary school mathematics education in Iran. Education Sciences, 11 (3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11030100

Van der Kleij, F. M., Vermeulen, J. A., Schildkamp, K., & Eggen, T. J. H. M. (2015). Integrating data-based decision making, assessment for learning, and diagnostic testing in formative assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 37–41.

Verhoeven, J. C., & Devos, G. (2005). School assessment policy and practice in Belgian secondary education with specific reference to vocational education and training. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 12 (3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940500337231

Walland, E., & Darlington, E. (2021). How do teachers respond to assessment reform? Exploring decision-making processes. Educational Research, 63 (1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2020.1857653

Whitehead, D. (2007). Literacy assessment practices: Moving from standardised to ecologically valid assessments in secondary schools. Language and Education, 21 (5), 434–452. https://doi.org/10.2167/le801.0

Willis, J., McGraw, K., & Graham, L. (2019). Conditions that mediate teacher agency during assessment reform. English Teaching, 18 (2), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-11-2018-0108

Yan, Z., Li, Z., Panadero, E., Yang, M., Yang, L., & Lao, H. (2021). A systematic review on factors influencing teachers’ intentions and implementations regarding formative assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy and Practice, 00 (00), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2021.1884042

Yan, Z., & Brown, G. T. L. (2021). Assessment for learning in the Hong Kong assessment reform: A case of policy borrowing. Studies in Educational Evaluation , 68 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.100985

Yu, W.-M. (2015). Teacher leaders’ perceptions and practice of student assessment reform in Hong Kong: A case study. Planning and Changing, 46 (1/2), 175–192.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Educational Psychology, Yangon University of Education, Yangon, Myanmar

Cherry Zin Oo

School of Education, University of New South Wales, Kensington, Australia

Dennis Alonzo & Sue O’Neill

Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang, Malang, Indonesia

University of Mindanao, Davao City, Philippines

Giovanni Pelobillo

Department of Education, Davao Division, Davao City, Philippines

Graduate School of Education and Human Development, Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan

Nang Mo Hline San

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: CZO, DA. Literature search: DA. Data analysis: CZO, RA, GP, RL, NMHS. Writing—original draft preparation: CZO, DA. Writing—review and editing: CZO, DA, SO.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cherry Zin Oo .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Oo, C.Z., Alonzo, D., Asih, R. et al. Implementing school-based assessment reforms to enhance student learning: a systematic review. Educ Asse Eval Acc 36 , 7–30 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-023-09420-7

Download citation

Received : 08 February 2023

Accepted : 03 October 2023

Published : 18 October 2023

Issue Date : February 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-023-09420-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- School-based assessment reforms

- Factors influencing assessment reforms

- School assessment

- Teacher assessment

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This exploratory paper seeks to shed light on the methodological challenges of education systems research. There is growing consensus that interventions to improve learning outcomes must be designed and studied as part of a broader system of education, and that learning outcomes are affected by a complex web of dynamics involving different inputs, actors, processes and socio-political contexts.

A structured discussion of the fairness of GCSE and A level grades in England in summer 2020 and 2021. et al. Article | Published online: 18 Feb 2024. Explore the current issue of Research Papers in Education, Volume 39, Issue 2, 2024.

Understanding what contributes to improving a system will help us tackle the problems in education systems that usually fail disproportionately in providing quality education for all, especially for the most disadvantage sectors of the population. This paper presents the results of a qualitative systematic literature review aimed at providing a comprehensive overview of what education research ...

Research in Education provides a space for fully peer-reviewed, critical, trans-disciplinary, debates on theory, policy and practice in relation to Education. International in scope, we publish challenging, well-written and theoretically innovative contributions that question and explore the concept, practice and institution of Education as an object of study.

In this study, the concept of Education 4.0 is examined and possible changes in known education systems are highlighted. The aim of this paper is to determine current research topics, explore knowledge gaps, and propose future directions in this field by reviewing the published literature on Education 4.0.

(2) Education should be viewed as a complex system. According to Jacobson et al. (2019), the application of complex systems as a theoretical perspective to research in education is at a nascent stage, as doing research on the education system is complex and challenging (Lemke and Sabelli, 2008).

Journal overview. Research Papers in Education has developed an international reputation for publishing significant research findings across the discipline of education. The distinguishing feature of the journal is that we publish longer articles than most other journals, to a limit of 12,000 words. We particularly focus on full accounts of ...

Artificial Intelligence in Education (AIEd) is an emerging interdisciplinary field that applies artificial intelligence technologies to transform instructional design and student learning. However, most research has investigated AIEd from the technological perspective, which cannot achieve a deep understand of the complex roles of AI in instructional and learning processes and its relationship ...

These technologies have shown a powerful impact on the education system. The recent COVID-19 Pandemic has further institutionalised the applications of digital technologies in education. These digital technologies have made a paradigm shift in the entire education system. ... The primary research objectives of this paper are as under: RO1: ...

The non-systematic literature review presented herein covers the main theories and research published over the past 17 years on the topic. It is based on meta-analyses and review papers found in scholarly, peer-reviewed content databases and other key studies and reports related to the concepts studied (e.g., digitalization, digital capacity) from professional and international bodies (e.g ...

Education systems provide the foundations for the futur e wellbeing of every. society, yet existing systems are a point of global concern. Education System Design is a. response to debates in dev ...

Results show similar effects, indicating scalability within government systems. These results reveal it is possible to strengthen the resilience of education systems, enabling education provision amidst disruptions, and to deliver cost-effective learning gains across contexts and with governments.

With the rapid increase in the number of scholarly publications on STEM education in recent years, reviews of the status and trends in STEM education research internationally support the development of the field. For this review, we conducted a systematic analysis of 798 articles in STEM education published between 2000 and the end of 2018 in 36 journals to get an overview about developments ...

ERIC is an online library of education research and information, sponsored by the Institute of Education Sciences (IES) of the U.S. Department of Education.

3. The Surprising Power of Pretesting. Asking students to take a practice test before they've even encountered the material may seem like a waste of time—after all, they'd just be guessing. But new research concludes that the approach, called pretesting, is actually more effective than other typical study strategies.

The education system in India: promises to keep. Kiran Bhatty Centre for Policy Research, New Delhi, India Correspondence [email protected]. ... perspectives, see Alan Blinder (Citation 1987), The Rules versus Discretion Debate in the Light of Recent Experience', Paper presented at the Kiel Conference of June 1987, 'Macro and Micro ...

How can education system transformation advance in your country or jurisdiction? We argue that three steps are crucial: Purpose (developing a broadly shared vision and purpose), Pedagogy ...

The twentieth century was the first century in which education systems were widely diffused and, at least in principle, accessible to all social groups. The century witnessed substantial expansion at the college level: The college enrollment rate for 20- to 21-y-olds increased from around 15 % for the mid-1920s birth cohorts to almost 60 % for ...

Abstract. The Philippines is concerned about the number of students attending schools, the quality of education. they receive, and the state of the learning environment. Solvi ng the education ...

Content may be subject to copyright. A Review on Indian Education System with Issues and Challenges. Ms. Falguni A. Suthar1. Ph.D. Research Scholar. Acharya Motibhai Patel Institute of Computer ...

These three institutional levels, in turn, give their outputs to their respective classrooms as inputs. Research has shown that an education system that works together with the other levels of the education system may offer high-quality learning opportunities (Garira et al., 2019; Lewis & Pettersson, 2009).

Think piece by UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Education, Stefania Giannini. Artificial Intelligence tools open new horizons for education, but we urgently need to take action to ensure we integrate them into learning systems on our terms. That is the core message of UNESCO's new paper on generative AI and the future of education.

Published research on AI in the consumer market, engineering, health care systems and other non-educational settings was thus excluded; 2. Research must be data-supported empirical studies. Articles that were solely based on personal opinions or anecdotal experiences were excluded; 3. Research must have investigated educational effects of AI by ...

Overall, teachers have a negative view of the U.S. K-12 education system - both the path it's been on in recent years and what its future might hold. The vast majority of teachers (82%) say that the overall state of public K-12 education has gotten worse in the last five years. Only 5% say it's gotten better, and 11% say it has gotten ...

View a PDF of the paper titled GenAI Detection Tools, Adversarial Techniques and Implications for Inclusivity in Higher Education, by Mike Perkins (1) and 7 other authors View PDF Abstract: This study investigates the efficacy of six major Generative AI (GenAI) text detectors when confronted with machine-generated content that has been modified ...

Developing and Validating the Qualitative Characteristics of Children's Play Assessment System Supported by Caplan Foundation Project led by: PI: Michael Haslip, PhD This one-year project in the McNichol ECE lab is validating an assessment created to measure young children's play skill development, called the Qualitative Characteristics of Children's Play or QCCP, and building a new ...

Viewpoints on different assessment systems used in many educational bureaucracies are diverse and continually evolving. Schools are tasked with translating those reforms' philosophies and principles into school-based assessment practices. However, it is unclear from research evidence what approach and factors best support the implementation of assessment reforms. To guide school leaders to ...

system such as a smartphone that has relatively limited computing power, due to the low-power nature of the system and latency constraints, us-ing a single, large, end-to-end model is infeasible: using a single LLM for this task would usually re-quire the use of a large model with long prompts for true end-to-end experiences (Wei et al.,2022).

In this paper we explore the power of a systems perspective to develop a wider, more holistic, and more equitable set of expectations for arts education's potential benefits. We conclude by offering recommendations for how researchers, practitioners, and policymakers can leverage the cultural traditions of REM children, families, and ...