Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 December 2023

Key factors behind various specific phobia subtypes

- Andras N. Zsido 1 , 2 ,

- Botond L. Kiss 1 ,

- Julia Basler 1 ,

- Bela Birkas 3 &

- Carlos M. Coelho 4

Scientific Reports volume 13 , Article number: 22281 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1216 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Risk factors

While it has been suggested that more than a quarter of the whole population is at risk of developing some form of specific phobia (SP) during their lives, we still know little about the various risk and protective factors and underlying mechanisms. Moreover, although SPs are distinct mental disorder categories, most studies do not distinguish between them, or stress their differences. Thus, our study was manifold. We examined the psychometric properties of the Specific Phobia Questionnaire (SPQ) and assessed whether it can be used for screening in the general population in a large sample (N = 685). Then, using general linear modeling on a second sample (N = 432), we tested how potential socio-demographic, cognitive emotion regulatory, and personality variables were associated with the five SP subtypes. Our results show that the SPQ is a reliable screening tool. More importantly, we identified transdiagnostic (e.g., younger age, female gender, rumination, catastrophizing, positive refocusing) as well as phobia-specific factors that may contribute to the development and maintenance of SPs. Our results support previous claims that phobias are more different than previously thought, and, consequently, should be separately studied, instead of collapsing into one category. Our findings could be pertinent for both prevention and intervention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Phobia-specific patterns of cognitive emotion regulation strategies

Andras N. Zsido, Andras Lang, … Anita Deak

Psychometric properties of the emotional processing scale in individuals with psychiatric symptoms and the development of a brief 15-item version

Daniel Maroti, Erland Axelsson, … Robert Johansson

The role of resilience in daily experiences of posttraumatic growth, affect, and HIV/AIDS stigma among people living with HIV

Małgorzata Pięta & Marcin Rzeszutek

Introduction

Evidence shows that specific phobias (SPs) are the most common anxiety- and mental disorders with a lifetime prevalence between 7.4 and 14% among adults with a cumulative incidence of 27% that is increasing 1 , 2 , 3 . That is, over a quarter of the whole population is at risk of developing some form of SP throughout their lives. Fear and its automatic activation by the detection of an object that might signal danger 4 is an adaptive response to imminent threats insofar as it helps prepare the organism for action and reduce the risk of being harmed. However, excessive levels of fear can interfere with one’s cognitive processes and movement preparation, and, as a consequence may result in disrupted behavior 5 ; for example, a diver might ascend too fast, a pedestrian might freeze, or a policeman might freeze or shoot too early 6 . Such core negative experiences—accompanied by a panic-like fear response and a loss of control over one’s emotions and behaviors—can result in the development of SPs 7 . Even in the absence of a proportional danger, phobias then manifest as extreme fear, and can be triggered even by the thought of the feared object 8 , 9 . The possibility and likelihood of direct engagement with potential treats (e.g., spiders, snakes, storms, etc.) may affect the prevalence of 10 , 11 Thus, environmental conditions have an influence on the development of SPs. The 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) distinguishes five SP subtypes: animals (e.g., snake, spider), environmental (e.g., storm, heights), situational (e.g., enclosed spaces), blood-injection-injury (BII; e.g., medical examinations), and other (e.g., choking). This categorization can also be useful in understanding fears that are not yet excessive but may foreshadow the possibility of developing a phobia (i.e., subclinical SP).

Determining the percentage of the general population that may be affected by subclinical levels of fear is vital, as SPs are often unrecognized and, consequently, often go untreated for a long time 12 . A lack of screening, diagnosis, and treatment has negative consequences both at an individual (e.g., reduced quality of life) and at a societal level (e.g., economic costs) 13 , 14 , 15 . A recent study offers a quick screening tool to assess the five subtypes of SP, the Specific Phobia Questionnaire (SPQ) 16 . The SPQ measures both fear and the extent to which fear interferes with daily life and has been proven reliable in clinical and subclinical samples as well. Assessing both fear and daily life interference is a novelty of the questionnaire and is in line with DSM-5 requirements for phobia diagnosis 8 , 17 , 18 . The tool is capable of identifying those at risk of either SP subtypes. Since SPQ has only been published in recent years, further evidence is needed about its psychometric soundness. While previous studies warn that a considerable percentage of the whole population might be affected by SPs at some point in their lives 3 , we still do not know the exact number and how it varies across countries 2 . The use of SPQ also opens the possibility of closely monitoring the percentage of the population at risk of various SPs.

While a large proportion of the population is at risk of developing SP, to date, still little is known about the particular risk factors associated with the development. The risk factors previous studies have shown can be categorized into three large groups: socio-demographic, personality, and cognitive emotion regulation (ER) strategies. A large-scale investigation in a representative sample of community-dwelling adults 19 has shown that the most prominent risk factors were female sex, a comorbid diagnosis of lifetime major depressive disorder, having experienced traumatic experiences involving significant others, the number of chronic diseases, and a comorbid diagnosis of substance use. Other studies also point to these factors, as well as higher levels of depressive mood and fewer years of education as potential risks of developing a SP 1 , 20 , 21 . Similarly, powerlessness, loss of control, and the lack of perceived control (strongly linked to one’s desire for control) and, consequently, the excessiveness of worry have long been associated with SPs 22 , 23 , 24 . It has also been shown 25 , 26 , 27 that SPs are associated with emotion dysregulation problems (e.g., using putatively maladaptive emotion regulation strategies, such as rumination). Yet, past studies have not sought to answer the question of whether these risk factors are transdiagnostic for all SPs or whether there is a specific pattern unique to each subtype.

The factors that increase the likelihood of reaching an excessive level of fear, and potentially the development of phobia, might vary across SP subtypes. There is great variability in the prevalence of SP subtypes which might indicate that besides the universal risk factors, there are subtype-specific ones as well. The key stimulus element that triggers the fear response greatly varies across SPs 28 . Consequently, there are overlaps but also unique characteristics of each SP in terms of the connected risk factors 28 . In fact, as part of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study, it has been shown 17 that the likelihood of impairment, comorbidity, and personality problems also greatly vary across SP subtypes. Similarly, there is evidence that a phobia-specific pattern exists in the putatively adaptive and maladaptive cognitive ER strategies 25 . Further, neurological evidence shows that viewing various phobia-relevant objects results in a different activation pattern 23 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , which also points to the direction that SP subtypes might be more different than previously thought. These results together underscore that there might be differences in the socio-demographic, cognitive emotion regulatory, and personality factors behind various SPs. Mapping the underlying transdiagnostic and unique factors for each SP can be crucial for an effective intervention therapy and may also increase the efficiency of prevention to deal with SPs.

The overarching goal of this study was twofold. First, we sought to test the SPQ in a large sample of community-dwelling adults, describe the prevalence of SP subtypes, and help establish standard scores. Second, we wanted to explore the unique and transdiagnostic risk and protective factors across SP subtypes associated with the level of fear and the interference this fear causes. We hypothesized that some factors, such as younger age, female gender, more previous traumatic life events, depressive mood, emotion dysregulation, and worry will be associated with higher rates of fear and interference. However, we also predicted that each SP subtype will have a unique pattern of associated risk factors concerning the cognitive ER strategies involved and other, perceived control-related components. To our knowledge, to this date, this is the only study to separately investigate risk and protective factors in various SP subtypes. Our results may assist counselors, social workers, and other health professionals in identifying individuals who might be at risk of developing an SP. Applications of these findings are pertinent for both prevention and intervention strategies.

Participants

We used two separate samples in this study. The first sample was used to test the psychometric properties of the SPQ and for descriptive analysis to estimate the prevalence of the five SP subtypes. For the first sample, we recruited 685 Caucasian participants (447 females), aged 18–85 years (M = 29.1, SD = 12.8). Here, we wanted to reach a large number of respondents to have a large enough sample for the descriptive analysis. For statistical purposes, we intended to increase the number of respondents by limiting the test battery to questions regarding age, gender, and the SPQ.

Then, we sought to test which sociodemographic, life history, cognitive emotion regulation, and personality-related factors play a key role in the development and maintenance of fears related to different SP subtypes. The second sample comprised 432 Caucasian participants (347 females), aged 18–67 years (M = 26.5, SD = 9.46). Here, the required sample size was determined by computing estimated statistical power with a conservative approach (f 2 = 0.10, β > 0.95, alpha = 0.05) using G*Power 3 software 34 . The analysis indicated a required minimum sample size of 373; thus, our study was adequately powered. Table 1 shows the central tendencies of the questionnaires and more details about the sample.

All participants were recruited through the Internet by posting invitations on various forums and mailing lists to obtain a non-clinical heterogeneous sample. Our goal was to obtain a heterogeneous sample representing people from a variety of demographic, socio-economic, and educational backgrounds. Table 1 shows the central tendencies of the questionnaires and more details about the samples. None of the respondents reported having been diagnosed with a specific phobia by a clinician or psychiatrist. Subjects participated voluntarily. The research was approved by the Hungarian United Ethical Review Committee for Research in Psychology and was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). Informed and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Questionnaires

Socio-demographic questions.

Socio-demographic questions were based on the results of a previous large-scale representative study on specific phobias 19 and included age, gender, marital status, the highest level of education, the number of personally experienced traumatic and violent life experiences, witnessed traumatic life experiences, the number of chronic diseases, smoker status, alcohol, marijuana, and other substance consumption habits, diagnosis of substance abuse disorder and major depressive disorder. These questions were selected because they emerged as significant predictors of phobias.

Specific phobia questionnaire (SPQ)

The SPQ measures the five subtypes of specific phobias with 43 items 16 . Each item is evaluated on two 5-point Likert-type scales (0—None to 4—Extreme) Fear and Interference. The Fear scales measure how fearful the respondent is of each situation, while the Interference scales measure how much the respondent’s fear interferes with their lives. The McDonald’s omegas for the Fear and Interference scales (respectively) were 0.78 and 0.84 (animals), 0.77 and 0.82 (natural environment), 0.77 and 0.78 (situational), 0.92 and 0.93 (blood-injection-injury). The Spearman–Brown coefficients for the other subscale were 0.50 and 0.65. The reason behind the lower reliability value of the other subscale is presumably due to the fact that it only consists of two items (Pearson r = 0.33 and 0.49).

All of the participants filled out the Hungarian language versions of the scales. The process of translation and adaptation of the instruments followed the recommendations of the American Psychiatric Association 8 . First, the original version of the questionnaire was given to two psychologists, both of whom were fluent in English, to translate the SPQ into Hungarian. Then, a third person, an expert in test development, was asked to compare the two versions and merge them into one to avoid any discrepancies and mistranslations. Subsequently, a person with a Master’s degree in psychology who is fluent in English translated this version back into English. Thereafter, an expert panel consisting of researchers in psychology as well as a native English speaker reviewed the back-translated version. They revised and corrected the Hungarian version to make it as close as possible in meaning to the original SPQ. We did not change any aspect of the original scale.

Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire (CERQ)

The 18-item version of the CERQ 35 , 36 measures cognitive strategies that characterize the individual’s style of responding to stressful events. The questionnaire has 9 subscales in total, four subscales measure putatively maladaptive strategies (Self-blame, Rumination, Catastrophizing, and Other blame), and five measure putatively adaptive strategies (Acceptance, Positive refocusing, Refocus on planning, Positive reappraisal, and Putting into perspective). Items are measured on 5-point Likert scales (1—almost never to 5—almost always). Higher scores indicate that a person uses the given strategy more often. The McDonald’s omegas were 0.77 (self-blame), 0.86 (rumination), 0.81 (catastrophizing), 0.63 (other blame), 0.84 (acceptance), 0.85 (positive refocusing), 0.63 (refocus on planning), 0.74 (positive reappraisal), and 0.79 (putting into perspective).

Desirability of control

To measure the level of motivation to control the events in one's life we used the Desirability of Control questionnaire (DSC) 37 . The questionnaire is a one-scale tool comprising 20 items. Items are rated on 7-point Likert-type scales (1—doesn’t apply to me to 7—always applies to me). Higher scores indicate a stronger desirability of control. The McDonald’s omega was 0.83.

Perceived emotional control

The short, 15-item version of the Anxiety Control Questionnaire (ACQ) was used to assess three facets of perceived control: Emotion Control, Threat Control, and Stress Control 38 . Items are rated on 6-point Likert-type scales (0—strongly disagree to 5—strongly agree). Higher scores indicate a higher level of perceived control. The McDonald’s omegas were 0.79 (emotion control), 0.76 (threat control), and 0.72 (stress control).

The 6-item short version of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was used to measure depressive mood 39 . Items were presented on 4-point scales, similarly to the original 21-item version. Higher scores suggest increased depressive symptomatology. The McDonald’s omega was 0.77.

The brief, 5-item version of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PWSQ) was used to measure the tendency, intensity, and uncontrollability of worry 40 . Items are rated on 5-point Likert-type scales (1—not at all typical of me to 5—very typical of me). Higher scores indicate a higher propensity to worry. The McDonald’s omega was 0.84.

Statistical analyses

There were no missing data because the answer was made mandatory for each question in the online surveys. We did not find any indicators of bot responses, and we did not expect to see any because participants completed all surveys voluntarily and in no instance were given any compensation. We sought for outliers who were ± 3 SDs away from the mean but we found none (which is justified by the large sample size). We also sought duplicate responses and identified four in the first sample; these were removed before the data analysis. We used Jamovi statistical software version 2.3 41 for the data analysis.

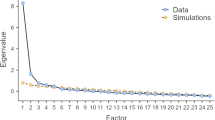

Before addressing the first objective of the study, we wanted to demonstrate that the factor structure of the SPQ suggested by the original authors is valid on an independent sample. Thus, we started by testing the five-factor model (separately for fear and interference) suggested by previous studies with confirmatory factor analysis on the first sample. We used the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator. To assess model fit, we used the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), the Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardized root mean squared residual index (SRMR). The cutoffs for good model fit were CFI and TLI values of 0.95 or greater 42 , PNFI value of 0.8 or greater 43 , RMSEA and SRMR values of 0.08 or lower 44 . McDonald’s omega values were also calculated to assess the reliability of the scales.

Then moving on to the first objective of the study, using the first sample, we then examined our sample with respect to the cut-off scores suggested by the developers of SPQ 16 to report the prevalence of each SP subtype. After this, gender differences were examined using a pairwise comparison with Student’s t-test, and the possible effects of age were investigated using Pearson correlation analysis. Where normality was violated (i.e., he absolute values of Skewness and Kurtosis were greater than 2), robust alternatives (i.e., Mann–Whitney test and Spearman correlation) were used. Regarding the comparison of effect sizes between parametric and nonparametric tests the guidelines by Cohen may serve as a good basis 45 . Pearson and Spearman correlations may be interpreted along the same guidelines, i.e., an r value between 0.2 and 0.5 refers to medium effect size. For Cohen’s d (Student t test) the range of medium effect is 0.5–0.8., while for the rank biserial correlation (Mann–Whitney test) the medium effect size is 0.4–0.8. Values below can be considered small effect sizes and values above can be considered large effect sizes.

Then to address our second objective, on the second sample, we used General Linear Modelling (GLM) to explore the socio-demographic factors, cognitive emotion regulation strategies, and personality-related questionnaires that are significant predictors of SPQ subscale scores. We used the five Fear and five Interference SPQ scores as the dependent variables in separate models. For each dependent variable, we tested three models. In Model 1 we tested the effects of socio-demographic variables, therefore the independent predictors were age, gender, marital status, and the level of education, the predictors were the number of personally experienced traumatic and violent life experiences, witnessed traumatic life experiences, the number of chronic diseases, smoker status, alcohol, marijuana, and other substance consumption habits, diagnosis of substance abuse disorder and major depressive disorder. In Model 2 we tested the effects of cognitive ER strategies, thus the predictors were the nine CERQ subscales. Finally, in Model 3 we tested personality-related factors, so the predictors were the DSC, three ACQ subscales, BDI, and PWSQ scores. The assumption of normality was not violated. The absolute values of Skewness and Kurtosis were less than 2 for all SPQ Fear subscales. We used Box-Cox transformation (lambda = 0.5) on the Interference subscales to achieve normal distribution. Statistical results will be presented in tables instead of in the text to make the description of the results easier to follow and more understandable.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Hungarian United Ethical Review Committee for Research in Psychology.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Factor structure and descriptive analysis

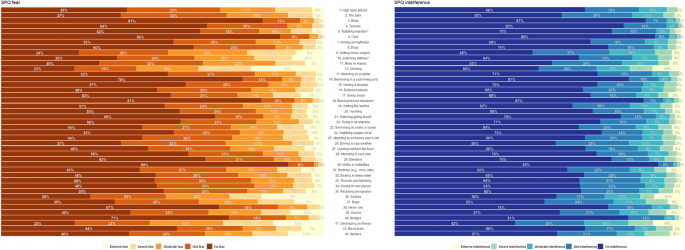

The two, five-factor structure of the SPQ showed acceptable fit for the Fear (X 2 (830) = 4366.216, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.991 TLI = 0.991, PNFI = 0.935, RMSEA = 0.062 [90% CI: 0.060–0.064], SRMR = 0.052) and the Interference subscales (X 2 (850) = 6566.073, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.994 TLI = 0.994, PNFI = 0.909, RMSEA = 0.078 [90% CI: 0.076–0.080], SRMR = 0.048). Factor loadings for the Fear scale ranged between 0.623 and 0.835 and between 0.734 and 0.906 for the Interference scale. Figure 1 shows the distribution of answers on the sample.

Percentage distribution of responses (no, mild, moderate, severe, extreme fear/interference) on the two subscales (Fear and Interference) of the Specific Phobia Questionnaire (SPQ). The left panel with the brown-yellow scale indicates the distribution of responses to the Fear subscale, where brown is no fear and yellow is extreme fear. The right panel with the blue-yellow scale indicates the distribution of responses to the Interference subscale, where blue is no fear and yellow is extreme fear. Corresponding items of the questionnaire are displayed in the middle.

The score corresponding to the 95th percentile on a given questionnaire is often considered a clinically significant limit 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 . Table 2 shows the 95th percentile scores separately for subscales and total score on the Fear and Interference scales as well as the number and percentage of participants who reached this score separately for males and females.

Further, based on the cut-off point suggested by the authors of the original questionnaire a large portion of the respondents could be considered at risk of having an SP. The prevalence values range from 12 to 60%. The exact cut-off values for the Fear and Interference subscales and the number and percentage of participants at risk of SP are shown in Table 2 .

Further analysis revealed systematic gender differences: females scored higher than males on all subscales both on the Fear scale and the Interference scale. Detailed statistical results are displayed in Table 3 . Regarding the relationship between SPQ and age, the Spearman correlation (controlled for gender differences) revealed significant but weak positive correlations for all the Interference scores (range 0.09–0.15), while we found no significant results for the Fear scale. The exact correlational values are displayed in Table 3 .

General linear models

We began by examining which socio-demographic factors, ER strategies, and personality-related questionnaires predict the five SPQ subscale scores regarding fear levels. The negative predictors may be considered protective factors because they are associated with lower levels of fear, in contrast, positive predictors can be considered risk factors as these variables are associated with higher levels of fear. Detailed statistical results, including model fit, and individual variable effects are presented in Supplementary material S1 regarding the five Fear subscales of SPQ.

For the Animals subtype , we found that age and perceived higher threat control were negative predictors, while female gender, depression diagnosis, a higher number of chronic diseases, using rumination, positive refocusing, and blaming others as ER strategies more often, and higher levels of worrying were all positive predictors.

Regarding the Environmental subtype, the significant negative predictors were more frequent alcohol consumption, using refocus on planning to regulate emotions, and perceived higher threat control; positive predictors were using rumination, positive refocusing, catastrophizing as ER strategies, higher BDI score, and worrying.

For the Situational subtype, we found that fear was negatively predicted by age and more frequent alcohol consumption, while it was positively predicted by female gender, more traumatic experiences, ruminating and using positive refocusing more often, and worrying.

For the BII subtype, the significant negative predictors were age and more frequent marijuana consumption, while positive predictors were female gender, ruminating and catastrophizing more often, and using positive refocusing to regulate emotions.

Finally, regarding the other subtype, scores were negatively associated with age, higher levels of education, more frequent alcohol and marijuana consumption, and higher levels of perceived stress control. Scores were positively associated with the female gender, ruminating and catastrophizing more often, and worrying.

In sum, it appears that some factors, such as age, gender, alcohol or marijuana consumption, a tendency to ruminate, use positive refocusing, and worry emerge as transdiagnostic factors appearing as significant predictors in nearly all subtypes. However, each subtype has a unique pattern that includes other significant predictors as well, namely depression diagnosis, chronic diseases and blaming others in animal phobias, refocus on planning and depressive mood in environmental phobias, traumatic experience in situational phobias, level of education and stress control in the other subtype.

Interference

We, then also investigated the effects of perceived interference of fears with the socio-demographic factors, ER strategies, and personality-related questionnaires as predictor variables. Again, negative predictors can be considered protective factors because they are associated with lower levels of interference; while positive predictors may be considered risk factors as they are associated with higher levels of interference. Supplementary material S2 shows the detailed statistical results, including model fit, and individual variable effects regarding the five Interference subscales of SPQ.

Regarding the Animal subtype, we found that education and using refocus on planning to regulate emotions emerged as significant negative predictors, while the female gender, using rumination, positive refocusing, and catastrophizing as ER strategies were positive predictors.

Regarding the Environmental subtype, significant negative predictors were education, more frequent alcohol consumption, using refocus on planning to regulate emotions, and higher perceived threat control. Positive predictors were using self-blame, positive refocusing, catastrophizing ER strategies, and depressive mood.

For the Situational subtype, we found that the interference was negatively predicted by education, more frequent alcohol consumption, and using acceptance to regulate emotions; while it was positively predicted by the female gender, higher number of chronic diseases, ruminating and catastrophizing more often and using putting into perspective to regulate emotions, depressive mood, and worrying.

For the BII subtype, the significant negative predictors were more frequent marijuana consumption, the use of acceptance, and refocus on planning ER strategies; while positive predictors were ruminating and catastrophizing and using refocus on planning and putting into perspective to regulate emotions.

Finally, regarding the other subtype, education, the use of acceptance to regulate emotions, and higher perceived stress control were identified as significant negative predictors, while the number of chronic diseases, catastrophizing, and worrying were positive predictors.

To sum up, we, again found some factors that emerged as transdiagnostic factors across all SP subtypes (e.g., education, a tendency to catastrophize the event); but also found several factors that seem to be subtype-specific. For instance, female gender in animal and situational phobia, self-blame and threat control in environmental phobia, marijuana consumption in BII phobia, and stress control in the other subtype.

Although SP is the most common mental disorder with a 7.4–14% lifetime prevalence and a cumulative incidence of 27% 1 , 2 , 3 , it often goes undiagnosed and untreated for a long time, possibly due to the lack of an appropriate screening tool 12 . The SPQ 16 offers a quick and reliable way to screen fears and associated interference on the five subtypes of SP; and is capable of identifying those at risk of either SP subtype. Therefore, the first goal of the present study was to examine the reliability of the SPQ in a large sample of community-dwelling adults and describe the prevalence of SP subtypes. Our results have shown that the questionnaire has sound psychometric properties and can be used in a different culture than it was developed. The results and prevalence values are similar to those of the original study. Compared to past studies 1 , 2 that used diagnostic interviews and trained personnel for data collection, the number of phobic individuals in our sample differs significantly when the cut-off points suggested by the authors are applied. In our sample, the 5 subtypes (based on fear score) varied between 12.3 and 60.3%. Here, animal phobia had a prevalence of 48.9%, compared to 3.8% in the study by Wardenaar et al. (2017). There was also a large difference regarding Situational (60.3% vs. 6.3%), BII (24.2% vs. 3.0%), and Environmental (15.3% vs. 2.3%) phobias between our and Wardenaar et al.’s study. The large differences may be partially due to the fact that the SPQ questionnaire, based on the cut-off points suggested, is not a diagnostic tool but rather a screening tool for the early identification of those at risk of SP. A higher score in this case indicates more susceptibility to these types of fears. In this way, the questionnaire can help to identify the groups most at risk of such fears, who can then be interviewed by a clinician and given appropriate help. A possible solution could be using the 95th percentile scores demonstrated in the present study as cut-offs in future research. In sum, our results provide further evidence that screening for SPs is important as it may help identify people at an early, subclinical stage where prevention can be more successful and easier than after the development of a disorder. Moreover, we have provided further evidence that SPQ is a reliable screening tool.

We sought to explore the transdiagnostic risk and protective factors across SP subtypes associated with the level of fear and the interference this fear causes as still little is known about the socio-demographic, cognitive emotion regulatory, and personality risk factors related to the development of these disorders. As expected, the factors associated with higher fear were younger age, female gender, rumination, positive refocusing, and worrying; while female gender, fewer years of education, and catastrophizing were associated with interference. Regarding gender and age, we found that females scored higher than males across all SP subtypes and had a weak negative correlation with age. These results are in line with previous studies showing a similar gender and age effect 2 , 50 , 51 , 52 as well as the fact that females compared to males are more likely to be diagnosed with SP 53 , 54 . This is also in line with the results of past studies 1 , 16 , 20 , 21 , 23 , 25 , 55 and suggests the notion that there are shared factors across SP subtypes. The fact that the prevalence and intensity of most phobias tend to decrease with age 56 and that females are at higher risk of developing an SP is well-established 57 . Similarly, emotion dysregulation is strongly associated with SPs and anxiety disorders as they can augment fears 58 , 59 , 60 . Focusing on negative emotions and failing to appropriately regulate emotions can increase worrying 61 , 62 , enhancing symptoms of anxiety 63 , therefore, augmenting everyday life interference. Our result suggests that positive refocusing, a putatively adaptive ER strategy also augments fears. Although an ER strategy may not inherently be either adaptive or maladaptive, this association may still seem contradictory. However, recent evidence 64 , 65 showed that adaptive ER strategies, if not used properly, may be associated with lower well-being and life satisfaction. Using positive refocusing means that the person thinks about positive, happy, and pleasant experiences instead of about current negative events 66 . A possible explanation behind our result is that positive refocusing might appear as an avoidance strategy in the case of phobias. Avoidance, in any form, is not an adaptive behavior insofar as it enhances fear 67 and was associated with psychopathology 65 .

We also wanted to investigate the unique pattern of risk factors associated with SPs, as there is great variability in prevalence 2 , stimulus element triggering fear 28 , the likelihood of impairment, comorbidity, and personality problems 17 , cognitive ER strategies 25 and brain activation pattern 23 , 29 , 30 of SP subtypes. As expected, our results clearly show that each SP subtype has a different pattern of associated factors; further, some factors only appear for one subtype and not for the others. Regarding animal fears, depression diagnosis, chronic diseases, blaming others, and threat control, while for the interference animal fears female gender seem to be critical phobia-specific factors. Although threat control appears for the Environmental subtype (fear) and female gender for the Situational subtype (interference). This is in line with previous studies showing gender differences in Animal phobia 47 , 51 , 52 . Further, a more restricted lifestyle and potential lack of social connections may also be associated with higher levels of fear and perceived interference 19 , 68 , which might also be the reason behind the slight overlap between Animal and environmental subtypes 69 . For the Environmental subtype, besides threat control, refocus on planning and depressive mood (fear), and self-blame were the unique factors. Environmental phobias comprise events and situations that can be foreseen and predicted and would not be possible to meet without the person approaching them. This might explain why one might blame oneself for the occurrence of an unfortunate event during a particular natural environment (e.g., water, heights) and highlights why planning and preparation can be a good coping mechanism. However, future studies are necessary to uncover the background mechanisms as Environmental phobias are understudied. We found that for Situational phobia fear was associated with traumatic experiences, while interference was associated with chronic diseases and worrying. This is in line with previous studies showing that excessive fear especially in this subtype is often evoked by one traumatic event in the past 70 , 71 . Then, the anticipation of an inevitable encounter with the object of the fear will trigger worrying, which in turn will impact the maintenance of the fear response, and increase the interference of the fear 72 . The unique predictor we found for BII phobia was marijuana consumption, and it was a protective factor. Similar to alcohol consumption we expected this to be a risk factor 19 , yet it seems that a recreational or at least subclinical form of alcohol and marijuana use may reduce fears. On the one hand, this might be a side effect, i.e., the consumption of these substances may reduce the reactivity of the individuals as shown in PTSD 73 , resulting in lesser fear and, thus, interference. On the other hand, people with these fears may be more likely to turn to these substances as self-imposed treatment, which temporarily could lower the level of fear and interference 74 . Finally, regarding the Other subtype, we found that stress control and worrying were the unique factors supporting previous studies on vomiting and choking-related fears 75 , 76 .

Limitations of the study include that we used a cross-sectional design, instead of gathering longitudinal data. Future studies are needed to test if the risk and protective factors suggested here would be predictive of the development of a SP. Further, the majority of our sample consisted mostly of females who are, according to our results and previous studies more prone to develop an SP. While this means the results are true for an endangered group of people, our results might not be universally true for other genders. Finally, although we included a large number of variables in the study, there could be more factors that can help predict the development of an SP or distinguish between subtypes. For instance, we targeted cognitive, but not behavioral or interpersonal ER strategies; we included measures of depression and anxiety but not tolerance of uncertainty or PTSD. Consequently, future studies are needed to explore all probable predictive variables.

In sum, these limitations notwithstanding, our study is among the first ones to explore phobia-specific patterns in the risk and protective factors that contribute to the development and maintenance of SPs. Our results may assist counselors, social workers, and other health professionals to identify individuals who might be at risk of developing an SP, and developing personalized treatment regimens. Younger females seem and people with a tendency to worry seem to be the most affected by such fears. Applications of our findings are also pertinent for both prevention and intervention strategies. Cognitive-behavioral-based interventions could be used to discourage the use of ER strategies—such as rumination, catastrophizing, and positive refocusing—that heighten fear levels, and instead focus on increasing the level of perceived control, and teach ER strategies—refocus on planning, in particular—that could lessen fears and its interference. These can be complemented by the inclusion of various phobia-specific factors. To further understand the socio-demographic, emotional, and personality-based mechanisms underlying the different phobia subtypes, future research should use longitudinal methods as well as experimental paradigms along with physiological measures.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Kessler, R. C. et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 , 593–602 (2005).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wardenaar, K. J. et al. The cross-national epidemiology of specific phobia in the world mental health surveys. Psychol. Med. 47 , 1744–1760 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Salehi, M. et al. The lifetime prevalence, risk factors, and co-morbidities of specific phobia among pediatric population: A cross-sectional national survey. Clin. Med. Insights Psychiatry 13 , 117955732110705 (2022).

Article Google Scholar

LeDoux, J. E. & Pine, D. S. Using neuroscience to help understand fear and anxiety: A two-system framework. Am. J. Psychiatry 173 , 1083–1093 (2016).

Zsido, A. N., Csokasi, K., Vincze, O. & Coelho, C. M. The emergency reaction questionnaire—First steps towards a new method. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 49 , 101684 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Klinger, D. Into the Kill Zone: A cop’s eye view of deadly force. J. POLICE Cris. Negot. 5 , 121–124 (2005).

Google Scholar

Vögele, C. et al. Cognitive mediation of clinical improvement after intensive exposure therapy of agoraphobia and social phobia. Depress. Anxiety 27 , 294–301 (2010).

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders 5th edn. (Author, 2013).

Book Google Scholar

Coelho, C. M. & Purkis, H. The origins of specific phobias: Influential theories and current perspectives. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 13 , 335–348 (2009).

Field, A. P. & Purkis, H. M. The role of learning in the etiology of child and adolescent fear and anxiety. in Anxiety Disorders in Children and Adolescents, Second edition 227–256 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511994920.012 .

Coelho, C. M., Polák, J., Suttiwan, P. & Zsido, A. N. Fear inoculation among snake experts. BMC Psychiatry 21 , 1–8 (2021).

Kasper, S. Anxiety disorders: Under-diagnosed and insufficiently treated. Int. J. Psychiatr. Clin. Pract. 10 , 3–9 (2006).

Konnopka, A. & König, H. Economic burden of anxiety disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PharmacoEconomics 38 , 25–37 (2020).

Kessler, R. C. & Greenberg, P. The economic burden of anxiety and stress disorders. in Neuropsychopharmacology: The Fifth Generation of Progress (eds. Davis, K. L., Charney, D., Nemeroff, J. T. & Coyle, C.) 981–992 (Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia US, 2002).

Alonso, J. et al. Disability and quality of life impact of mental disorders in Europe: Results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. Suppl. 109 , 38–46 (2004).

Ovanessian, M. M. et al. Psychometric properties and clinical utility of the specific phobia questionnaire in an anxiety disorders sample. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 41 , 36–52 (2019).

Depla, M. F. I. A., ten Have, M. L., van Balkom, A. J. L. M. & de Graaf, R. Specific fears and phobias in the general population: Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 43 , 200–208 (2008).

Oosterink, F. M. D., de Jongh, A. & Hoogstraten, J. Prevalence of dental fear and phobia relative to other fear and phobia subtypes. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 117 , 135–143 (2009).

Coelho, C. M., Gonçalves-Bradley, D. & Zsido, A. N. Who worries about specific phobias? A population-based study of risk factors. J. Psychiatr. Res. 126 , 67–72 (2020).

Blanco, C. et al. Risk factors for anxiety disorders: Common and specific effects in a national sample. Depress. Anxiety 31 , 756–764 (2014).

Maideen, S. F. K., Sidik, S. M., Rampal, L. & Mukhtar, F. Prevalence, associated factors and predictors of anxiety: A community survey in Selangor, Malaysia. BMC Psychiatry 15 , (2015).

Armfield, J. M. & Heaton, L. J. Management of fear and anxiety in the dental clinic: A review. Aust. Dental. J. 58 , 390–407 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Abado, E., Aue, T. & Okon-Singer, H. Cognitive biases in blood-injection-injury phobia: A review. Front. Psychiatry 12 , 1158 (2021).

Gallagher, M. W., Bentley, K. H. & Barlow, D. H. Perceived control and vulnerability to anxiety disorders: A meta-analytic review. Cognit. Ther. Res. 38 , 571–584 (2014).

Zsido, A. N., Lang, A., Labadi, B. & Deak, A. Phobia-specific patterns of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. Sci. Rep. (2023).

Hermann, A. et al. Emotion regulation in spider phobia: Role of the medial prefrontal cortex. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 4 , 257–267 (2009).

Cisler, J. M., Olatunji, B. O. & Lohr, J. M. Disgust sensitivity and emotion regulation potentiate the effect of disgust propensity on spider fear, blood-injection-injury fear, and contamination fear. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry 40 , 219–229 (2009).

Coelho, C. M., Araújo, A. S., Suttiwan, P. & Andras N. Zsido. An ethologically based view into human fear. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 154 , 105017 (2022).

Lueken, U. et al. How specific is specific phobia? Different neural response patterns in two subtypes of specific phobia. Neuroimage 56 , 363–372 (2011).

Hilbert, K., Evens, R., Isabel Maslowski, N., Wittchen, H. U. & Lueken, U. Neurostructural correlates of two subtypes of specific phobia: A voxel-based morphometry study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 231 , 168–175 (2015).

Del Casale, A. et al. Functional neuroimaging in specific phobia. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 202 , 181–197 (2012).

Caseras, X. et al. The functional neuroanatomy of blood-injection-injury phobia: A comparison with spider phobics and healthy controls. Psychol. Med. 40 , 125–134 (2010).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Caseras, X. et al. Dynamics of brain responses to phobic-related stimulation in specific phobia subtypes. Eur. J. Neurosci. 32 , 1414–1422 (2010).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39 , 175–191 (2007).

Garnefski, N. & Kraaij, V. Cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire—development of a short 18-item version (CERQ-short). Pers. Individ. Dif. 41 , 1045–1053 (2006).

Miklósi, M., Martos, T., Kocsis-Bogár, K. & Perczel-Forintos, D. A Kognitív Érzelem-Reguláció Kérdőív magyar változatának pszichometriai jellemzői. Psychiatr. Hungarica 26 , 102–111 (2011).

Burger, J. M. & Cooper, H. M. The desirability of control. Motiv. Emot. 3 , 381–393 (1979).

Brown, T. A., White, K. S., Forsyth, J. P. & Barlow, D. H. The structure of perceived emotional control: Psychometric properties of a revised anxiety control questionnaire. Behav. Ther. 35 , 75–99 (2004).

Blom, E. H., Bech, P., Högberg, G., Larsson, J. O. & Serlachius, E. Screening for depressed mood in an adolescent psychiatric context by brief self-assessment scales—testing psychometric validity of WHO-5 and BDI-6 indices by latent trait analyses. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 10 , 1–6 (2012).

Topper, M., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., Watkins, E. & Ehring, T. Development and assessment of brief versions of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire and the Ruminative Response Scale. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 53 , 402–421 (2014).

Jamovi Project. Jamovi. (2022).

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 3 , 424–453 (1998).

Byrne, B. M. Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus . Structural Equation Modeling with Mplus (Routledge, 2013). https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203807644 .

Browne, M. W. & Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Methods Res. 21 , 230–258 (1992).

Cohen, J. A power primer. Psychol. Bull. 112 , 155–159 (1992).

Crawford, J. R. & Garthwaite, P. H. Percentiles please: The case for expressing neuropsychological test scores and accompanying confidence limits as percentile ranks. Clin. Neuropsychol. 23 , 193–204 (2009).

Polák, J., Sedláčková, K., Nácar, D., Landová, E. & Frynta, D. Fear the serpent: A psychometric study of snake phobia. Psychiatry Res. 242 , 163–168 (2016).

Mollema, E. D., Snoek, F. J., Pouwer, F., Heine, R. J. & Van Der Ploeg, H. M. Diabetes fear of injecting and self-testing questionnaire: A pschometric evaluation. Diabetes Care 23 , 765–769 (2000).

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. C28-a3c. Defining, establishing and verifying reference intervals in the clinical laboratory; approved guideline, third edition . (2008).

Zsido, A. N. The spider and the snake—A psychometric study of two phobias and insights from the Hungarian validation. Psychiatry Res. 257 , 61–66 (2017).

Zsido, A. N., Arato, N., Inhof, O., Janszky, J. & Darnai, G. Short versions of two specific phobia measures: The snake and the spider questionnaires. J. Anxiety Disord. 54 , (2018).

Fredrikson, M., Annas, P., Fischer, H. & Wik, G. Gender and age differences in the prevalence of specific fears and phobias. Behav. Res. Ther. 34 , 33–39 (1996).

LeBeau, R. T. et al. Specific phobia: A review of DSM-IV specific phobia and preliminary recommendations for DSM-V. Depress. Anxiety 27 , 148–167 (2010).

Wittchen, H. U., Stein, M. B. & Kessler, R. C. Social fears and social phobia in a community sample of adolescents and young adults: Prevalence, risk factors and co-morbidity. Psychol. Med. 29 , 309–323 (1999).

Zsido, A. N., Coelho, C. M. & Polák, J. Nature relatedness: A protective factor for snake and spider fears and phobias. People Nat. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10303 (2022).

Coelho, C. M. et al. Specific phobias in older adults: Characteristics and differential diagnosis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 22 , 702–711 (2010).

Eaton, W. W., Bienvenu, O. J. & Miloyan, B. Specific phobias. The Lancet Psychiatry 5 , 678–686 (2018).

Mennin, D. S., McLaughlin, K. A. & Flanagan, T. J. Emotion regulation deficits in generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, and their co-occurrence. J. Anxiety Disord. 23 , 866–871 (2009).

Dryman, M. T. & Heimberg, R. G. Emotion regulation in social anxiety and depression: A systematic review of expressive suppression and cognitive reappraisal. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 65 , 17–42 (2018).

Cisler, J. M., Olatunji, B. O., Feldner, M. T. & Forsyth, J. P. Emotion regulation and the anxiety disorders: An integrative review. J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 32 , 68–82 (2010).

Evans, S., Alkan, E., Bhangoo, J. K., Tenenbaum, H. & Ng-Knight, T. Effects of the COVID-19 lockdown on mental health, wellbeing, sleep, and alcohol use in a UK student sample. Psychiatry Res. 298 , 113819 (2021).

Ouellet, C., Langlois, F., Provencher, M. D. & Gosselin, P. Intolerance of uncertainty and difficulties in emotion regulation: Proposal for an integrative model of generalized anxiety disorder. Rev. Eur. Psychol. Appl. 69 , 9–18 (2019).

Jaso, B. A., Hudiburgh, S. E., Heller, A. S. & Timpano, K. R. The relationship between affect intolerance, maladaptive emotion regulation, and psychological symptoms. Int. J. Cogn. Ther. 13 , 67–82 (2020).

Elkjær, E., Mikkelsen, M. B. & O’Toole, M. S. Emotion regulation patterns: Capturing variability and flexibility in emotion regulation in an experience sampling study. Scand. J. Psychol. 63 , 297–307 (2022).

Kalokerinos, E. K., Erbas, Y., Ceulemans, E. & Kuppens, P. Differentiate to regulate: Low negative emotion differentiation is associated with ineffective use but not selection of emotion-regulation strategies. Psychol. Sci. 30 , 863–879 (2019).

Kraaij, V. & Garnefski, N. The Behavioral Emotion Regulation Questionnaire: Development, psychometric properties and relationships with emotional problems and the cognitive emotion regulation questionnaire. Pers. Individ. Dif. 137 , 56–61 (2019).

Schlund, M. W. et al. Renewal of fear and avoidance in humans to escalating threat: Implications for translational research on anxiety disorders. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 113 , 153–171 (2020).

Patuano, A. Biophobia and urban restorativeness. Sustainability (Switzerland) 12 , 4312 (2020).

Choi, Y. H., Jang, D. P., Ku, J. H., Shin, M. B. & Kim, S. I. Short-term treatment of acrophobia with virtual reality therapy (VRT): A case report. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 4 , 349–354 (2001).

Wilhelm, F. H. & Roth, W. T. Clinical characteristics of flight phobia. J. Anxiety Disord. 11 , 241–261 (1997).

Taylor, J., Deane, F. & Podd, J. Driving-related fear: A review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 22 , 631–645 (2002).

Clark, G. I. & Rock, A. J. Processes contributing to the maintenance of flying phobia: A narrative review. Front. Psychol. 7 , 754 (2016).

Tull, M. T., McDermott, M. J. & Gratz, K. L. Marijuana dependence moderates the effect of posttraumatic stress disorder on trauma cue reactivity in substance dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 159 , 219–226 (2016).

Flory, K., Lynam, D., Milich, R., Leukefeld, C. & Clayton, R. The relations among personality, symptoms of alcohol and marijuana abuse, and symptoms of comorbid psychopathology: Results from a community sample. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 10 , 425–434 (2002).

Simons, M. & Vloet, T. D. Emetophobia - A metacognitive therapeutic approach for an overlooked disorder. Zeitschrift fur Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrie und Psychotherapie 46 , 57–66 (2018).

van Overveld, M., de Jong, P. J., Peters, M. L., van Hout, W. J. P. J. & Bouman, T. K. An internet-based study on the relation between disgust sensitivity and emetophobia. J. Anxiety Disord. 22 , 524–531 (2008).

Download references

ANZS was supported by the ÚNKP-23-5, BLK and JB by the ÚNKP-23-3 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Innovation and Technology from the source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund. ANZS was also supported by OTKA PD 137588 research grant. BLK, JB, and BB also received support from OTKA K 143254 research grant. ANZS and BB was also supported by the János Bolyai Research Scholarship provided by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. CMC was supported by the Center for Psychology at the University of Porto, Foundation for Science and Technology Portugal (FCT UIDB/00050/2020).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Psychology, University of Pécs, 6 Ifjusag Street, Pécs, Baranya, 7624, Hungary

Andras N. Zsido, Botond L. Kiss & Julia Basler

Szentágothai Research Centre, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary

Andras N. Zsido

Medical School, University of Pécs, Pécs, Hungary

Bela Birkas

Department of Psychology, University of the Azores, Ponta Delgada, Portugal

Carlos M. Coelho

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.N.Z.S., C.M.C.; methodology: A.N.Z.S., C.M.C.; formal analysis: A.N.Z.S., B.L.K., J.B.; data preparation: B.L.K., J.B.; writing—original draft: A.N.Z.S., B.L.K., J.B.; visualization: B.L.K., J.B.; supervision: A.N.Z.S., B.B., C.M.C.; project administration: A.N.Z.S., B.B.; funding acquisition: A.N.Z.S., B.L.K., J.B., B.B., C.M.C.; writing—review and editing: A.N.Z.S., B.L.K., J.B., B.B., C.M.C.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Andras N. Zsido .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary table 1., supplementary table 2., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zsido, A.N., Kiss, B.L., Basler, J. et al. Key factors behind various specific phobia subtypes. Sci Rep 13 , 22281 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49691-0

Download citation

Received : 26 June 2023

Accepted : 11 December 2023

Published : 14 December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-49691-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Research Findings on the Genetics of Phobias

Daniel B. Block, MD, is an award-winning, board-certified psychiatrist who operates a private practice in Pennsylvania.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/block-8924ca72ff94426d940e8f7e639e3942.jpg)

Phobias are extreme fears that make it impossible to function normally. Phobias may grow out of really negative experiences, but because they are overwhelming and often irrational, they become disabling. There are many different types of phobias; some of the most common include:

- Fear of specific animals (dogs, spiders, etc.)

- Fear of open spaces, enclosed space, or high places

- Fear of natural events, such as thunderstorms

While fears are an unavoidable part of being human, most fears can be controlled and managed. Phobias, however, cause psychological and physical reactions that are difficult if not impossible to manage. As a result, people with phobias will go to great lengths to avoid the object of their fears.

What Causes Phobias?

Why does someone react to a normal, everyday event — the bark of a dog, for example — with extreme fear and anxiety? Why do other people react to the same experience with mild anxiety or calm?

The causes of phobias are not yet widely understood. Increasingly, however, research shows that genetics may play at least some role.

Studies show that twins who are raised separately have a higher than average rate of developing similar phobias. Other studies show that some phobias run in families, with first-degree relatives of phobia sufferers more likely to develop a phobia.

In “Untangling genetic networks of panic, phobia, fear, and anxiety,” Villafuerte and Burmeister reviewed several earlier studies in an attempt to determine what, if any, genetic causes can be identified for anxiety disorders.

Family Studies Suggest a Genetic Link

If a family member has a phobia, you are at an increased risk for a phobia as well.

In general, relatives of someone with a specific anxiety disorder are most likely to develop the same disorder. In the case of agoraphobia (fear of open spaces), however, first-degree relatives are also at increased risk for panic disorder, indicating a possible genetic link between agoraphobia and panic disorder .

Researchers have found that first-degree relatives of someone suffering from a phobia are approximately three times more likely to develop a phobia.

According to the findings, twin studies showed that when one twin has agoraphobia, the second twin has a 39% chance of developing the same phobia. When one twin has a specific phobia, the second twin has a 30% chance of also developing a specific phobia. This is much higher than the 10% chance of developing an anxiety disorder found in the general population.

Gene Isolation Suggests a Link Between Phobias and Panic Disorder

Although they were unable to specifically isolate the genetic causes of phobias, Villafuerte and Burmeister reviewed several studies that appear to demonstrate genetic anomalies in both mice and humans with anxiety disorders. The early research appears to show that agoraphobia is more closely linked to panic disorder than to the other phobias, but is far from conclusive.

More research will need to be performed in order to isolate the complex genetics involved in the development of phobias and other anxiety disorders. However, this study does support the theory that genetics play a major role.

- Villafuerte, Sandra and Burmeister, Margit. Untangling genetic networks of panic, phobia, fear and anxiety . Genome Biology . July 28, 2003. 4(8):224.

By Lisa Fritscher Lisa Fritscher is a freelance writer and editor with a deep interest in phobias and other mental health topics.

January 1, 2014

Why Do We Develop Certain Irrational Phobias?

By Andrew Watts

Katherina K. Hauner , a postdoctoral fellow at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, answers:

Under normal circumstances, fear triggers a natural fight-or-flight response that allows animals to react quickly to threats in their environment. Irrational and excessive fear, however, is typically a maladaptive response. In humans, an unwarranted, persistent fear of a certain situation or object, known as specific phobia, can cause overwhelming distress and interfere with daily life. Specific phobia is among the more prevalent anxiety disorders, affecting an estimated 9 percent of Americans within their lifetime. Common subtypes include fear of small animals, insects, flying, enclosed spaces, blood and needles.

For fear to escalate to irrational levels, a combination of genetic and environmental factors is very likely at play. Estimates of genetic contributions to specific phobia range from roughly 25 to 65 percent, although we do not know which genes have a leading part. No specific phobia gene has been identified, and it is highly unlikely that a single gene is responsible. Rather variants in several genes may predispose an individual to developing a number of psychological symptoms and disorders, including specific phobia.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

As for the environmental component, a person may develop a phobia after a particularly frightening event, especially if he or she feels out of control. Even witnessing or hearing about a traumatic occurrence can contribute to its development. For instance, watching a devastating airplane crash on the news may trigger a fear of flying. That said, discerning the origin of the disorder can be difficult because people tend to do a poor job of identifying the source of their fears.

Our understanding of how and why phobias crop up remains limited, but we have made great strides in abating them. Exposure therapy, a form of cognitive-behavior therapy, is widely accepted as the most effective treatment for anxieties and phobias, and the vast majority of patients complete treatment within 10 sessions. During exposure therapy, a person engages with the particular fear to help diminish and ultimately overcome it over time. An individual might, for example, look at a photograph of the dreaded object or become immersed in the situation he or she loathes. Fortunately for those plagued by irrational fears, we can treat a phobia rapidly and successfully without necessarily knowing its origin.

Articles on Phobias

Displaying 1 - 20 of 26 articles.

Biophobia: search trends reveal a growing fear of nature

Ricardo Correia , University of Helsinki and Stefano Mammola , University of Helsinki

Innies, outies and omphalophobia: 7 navel-gazing questions about belly buttons answered

Sarah Leupen , University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Why are we so scared of clowns? Here’s what we’ve discovered

Sophie Scorey , University of South Wales ; James Greville , University of South Wales ; Philip Tyson , University of South Wales , and Shakiela Davies , University of South Wales

Scared of needles? Claustrophobic? One longer session of exposure therapy could help as much as several short ones

Bronwyn Graham , UNSW Sydney and Sophie H Li , UNSW Sydney

CBT? DBT? Psychodynamic? What type of therapy is right for me?

Sourav Sengupta , University at Buffalo

Pictures of COVID injections can scare the pants off people with needle phobias. Use these instead

Holly Seale , UNSW Sydney and Jessica Kaufman , Murdoch Children's Research Institute

Tokophobia is an extreme fear of childbirth. Here’s how to recognise and treat it

Julie Jomeen , Southern Cross University ; Catriona Jones , University of Hull ; Claire Marshall , University of Hull , and Colin Martin , Southern Cross University

Spider home invasion season: why the media may be to blame for your arachnophobia

Mike Jeffries , Northumbria University, Newcastle

Fear can spread from person to person faster than the coronavirus – but there are ways to slow it down

Jacek Debiec , University of Michigan

Anxiety in autistic children – why rates are so high

Keren MacLennan , University of Reading

Curious Kids: where do phobias come from?

Lara Farrell , Griffith University

Fear of the dentist: what is dental phobia and dental anxiety?

Ellie Heidari , King's College London

Get ‘inspidered’ – from fear of spiders to fascination

Gerhard J. Gries , Simon Fraser University and Andreas Fischer , Simon Fraser University

You can’t ‘erase’ bad memories, but you can learn ways to cope with them

Carol Newall , Macquarie University and Rick Richardson , UNSW Sydney

Tokophobia: what it’s like to have a phobia of pregnancy and childbirth

Catriona Jones , University of Hull ; Franziska Wadephul , University of Hull , and Julie Jomeen , University of Hull

Health Check: why are some people afraid of heights?

Bek Boynton , James Cook University and Anne Swinbourne , James Cook University

How virtual reality spiders are helping people face their arachnophobia

Why are some people afraid of cats?

Sally Shuttleworth , University of Oxford

From creepy clowns to the dancing plague – when phobias are contagious

Clare Glennan , Cardiff Metropolitan University

Fear of death underlies most of our phobias

Lisa Iverach , University of Sydney ; Rachel E. Menzies , University of Sydney , and Ross Menzies , University of Sydney

Related Topics

- Arachnophobia

- Exposure therapy

- Mental health

- Neuroscience

Top contributors

Professor of Midwifery and Dean in the Faculty of Health Sciences, Southern Cross University

Senior Research Fellow in Maternal and Reproductive Health, University of Hull

Senior Lecturer, Psychology, James Cook University

Principal Program Officer (Respectful Workplaces), James Cook University

Honorary Associate at Department of Psychology, Macquarie University and Research Fellow, University of Sydney

Associate Professor, McGill University

Associate professor, UNSW Sydney

PhD Candidate, University of Essex

Senior Lecturer in Psychology and Behavioural Medicine, St George's, University of London

Associate Professor, University of Sydney

Professor of Psychology, University of Essex

Postdoctoral research fellow, School of Psychology, University of Sydney

Lecturer of Psychology, Cardiff Metropolitan University

Associate Professor, Ecology, Northumbria University, Newcastle

Professor of Neuropsychology (Hons), Cardiff University

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Latest news

- UCL in the media

- Services for media

- Student news

- Tell us your story

The new evidence that explains what anxiety really is

5 April 2024

Read: The New Scientist

The One Big Thing You Can Do for Your Kids

The research shows that you probably have less effect on your kids than you think—with one big exception: Your love will make them happy.

Want to stay current with Arthur’s writing? Sign up to get an email every time a new column comes out.

W hen one of my now-adult kids was in middle school, I had a small epiphany about parenting. I had been haranguing him constantly about his homework and grades, which were indeed a problem. One night, after an especially bad day, I was taking stock of the situation, and came to a realization: I didn’t actually care very much about his grades. What I wanted was for him to grow up to become a responsible, ethical, faithful, well-adjusted man. From that day forward, I stopped talking about his grades and started talking about values. It was a relief for both of us.

But then I got to wondering: If bugging him about grades didn’t change anything, why would talking about values make a difference? Did it really matter what I said about anything ?

If you have children—or plan to have them—you probably share my concerns. According to a survey last year by the Pew Research Center , the No. 1 desire of parents for their children (which 94 percent of those surveyed say is extremely or very important) is that their kids turn out to be honest and ethical. Meanwhile, the No. 1 worry (which 76 percent of parents said was extremely-to-somewhat worrisome) is that their kids might struggle with depression or anxiety. In short, we want them above all to be good and happy people.

But just wanting these things isn’t enough. How do we achieve these goals? This question is at least as ancient as human civilization. Should we talk about these things with our children a lot, or not? Be strict with them, or lax? Or perhaps everything is genetics anyway, so maybe we should just hope and pray for the best. Fortunately, recent research has offered ways to help answer some of these difficult questions—and make us better parents.

Arthur C. Brooks: The happy art of grandparenting

A foundational question about raising children revolves around nature versus nurture: how much of a child’s development is due to their genes rather than their upbringing. When I was a child, nurture theories had the upper hand. The common belief was that kids are a blank slate, or are nearly so, and that parenting is what really matters to mold who they will become as adults. Latterly, however, this view has been turned upside down, after study upon study has shown that a huge amount of personality is biological and inherited. For example, one 1996 study involving 123 pairs of identical twins (who share 100 percent of their genes) and 127 pairs of fraternal twins (who, like any other pair of siblings, share about 50 percent) estimated that 41 percent of neuroticism may be inherited, as well as 53 percent of extroversion, 61 percent of openness to experience, 41 percent of agreeableness, and 44 percent of conscientiousness.

You might be thinking that parenting may make up the other half or so, but that’s not seemingly the case. Researchers in 2021 examined over time the correlation between the personality traits of progeny and parenting measures, and found that, in most aspects, parenting mattered about as much as birth order—which is to say, its effect was little to none.

The exceptions were in two dimensions of personality: conscientiousness and agreeableness. Children were more conscientious when parents were more involved in their lives and worked to provide cultural stimulation (such as taking them to museums); and children were more agreeable when their parents raised them with more structure and goals.

Genetics also matter a great deal for children’s happiness. One study of fraternal and identical twins found that the genetic component discernible from analyzing the subjects’ various self-reported ratings of personality traits and life satisfaction was about 31 percent . In contrast with the possibly limited influence of parenting style on most personality traits, however, parental behavior does appear to significantly affect the roughly half of children’s happiness that may not be genetically determined. Specifically, one factor—parental warmth and affection, with slightly more weight to that of fathers—has been shown to make up about a third of “psychological adjustment” differences in their children, a holistic measure that includes markers of happiness.

Parenting involves both words and actions. Even if parents like to say to their children, usually with little effect, “Do what I say,” most parents come to notice that kids pay attention to everything their parents do , rather than what they say . And research backs up the idea that actions speak louder than words. For example, a 2001 study of parental religiosity among Catholics found that the behavior of a father (even more than the mother) who acts upon faith and is practicing will most affect the likelihood of his children growing up to be religious as well. Similarly, an investigation of substance use among adolescents discovered that among those who had tried alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs, 80 percent said their parents would say they disapproved of their teenager’s behavior, but 100 percent did not say explicitly that their parents abstained from substances—suggesting that these children likely had at least one parent who used them to a lesser or greater extent.

Listen: The right choices in parenting

T his tour through the research provides a set of parenting rules to act upon—one that I could very much have used when my kids were little. Better late than never, and I can still try to follow these rules now that I am a grandfather . Try them out and see if they make parenting easier and better for you. If your goal is virtue and happiness for your kids, keep these three things in mind.

1. Even a hot mess can be a good parent. It is easy to despair at being a parent—or to give yourself a pass—if you struggle with your own happiness or with a troublesome personality. I have heard many young adults say they’re afraid to have kids because they don’t want to pass on their own problems. True, much of your personality is transmitted to your offspring without your volition. As noted above, you may not be able to do much about their degree of extroversion, which seems largely a genetic given. But when it comes to conscientiousness and agreeableness (which, again, are what we really want for our children), parenting choices to be involved in their lives, and provide structure and goals, make a significant difference. And parenting does have a huge impact on their happiness.

2. When you don’t know what to do, be warm and loving. For happiness, the parenting technique that truly matters is warmth and affection. As my wife used to say when we were at wit’s end with our son, “I guess we should just love him.” This might sound like a hippie recipe for disaster, but it isn’t. Your kids don’t need a drill sergeant, Santa Claus, or a helicopter mom; they need someone who loves them unconditionally, and shows it even when the brats deserve it the least. Especially when they’re at their most brattish. Remember: That is what they will remember and give to your grandchildren (who will never be brats) when they themselves become parents.

3. Be the person you want your kids to become. The data don’t lie, but as parents we do . Kids—who are walking BS-detectors—always notice when we say one thing and do another. Of course, deciding how to act to create the right example for them to follow isn’t always easy. A good rule of thumb is to ask yourself how you’d like your son or daughter to behave as an adult in a given situation—and then do that yourself. When you’re driving and get cut off in traffic, you would like it not to bother them—so don’t let them see it bothering you. You would prefer they don’t get drunk, so don’t drink too much yourself. You’d like them to be generous to others, so be generous too.

Arthur C. Brooks: Don’t teach your kids to fear the world

F or young and future parents reading this, one last note: You will make a lot of mistakes, but mostly they won’t matter. I can think of my selfishness and blunders as a father, and on some sleepless nights the instances roll around in my head and fill me with regret. But then I look at my son. So how did all my hectoring about grades and values work out?

He skipped college and joined the U.S. Marine Corps, in which he spent four years as a mortarman and sniper. Now 23, he is happily married and works in a job he loves as a manager at a construction company. He won’t see this column because, well, he doesn’t have time to read my stuff. But he loves me and I love him; we talk every single day; and despite all of my missteps, he turned out just fine. And most likely, so will your child.

Small protein plays big role in chronic HIV infection

UC Riverside-led study on innate immune system may lead to new treatments for patients with neuroHIV

NeuroHIV refers to the effects of HIV infection on the brain or central nervous system and, to some extent, the spinal cord and peripheral nervous system. A collection of diseases, including neuropathy and dementia, neuroHIV can cause problems with memory and thinking and compromise our ability to live a normal life.

Using a mouse model of neuroHIV, a research team led by biomedical scientists at the University of California, Riverside, studied the effects of interferon-β (IFNβ), a small protein involved in cell signaling and integral to the body’s natural defense mechanism against viral infections. The researchers found that higher or lower than normal levels of IFNβ affect the brain in a sex-dependent fashion: some changes only occur in females, others only in males.