Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The reformation.

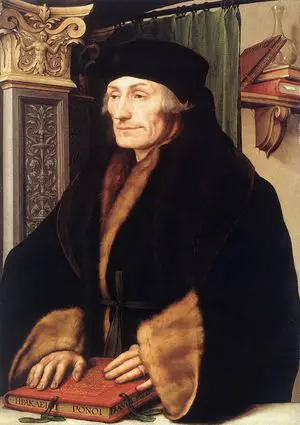

Erasmus of Rotterdam

Hans Holbein the Younger (and Workshop(?))

Martin Luther (1483–1546)

Workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder

- The Last Supper

Designed by Bernard van Orley

The Fifteen Mysteries and the Virgin of the Rosary

Netherlandish (Brussels) Painter

Albrecht Dürer

Four Scenes from the Passion

Follower of Bernard van Orley

Friedrich III (1463–1525), the Wise, Elector of Saxony

Lucas Cranach the Elder and Workshop

Martin Luther as an Augustinian Monk

Lucas Cranach the Elder

Johann I (1468–1532), the Constant, Elector of Saxony

The Last Judgment

Joos van Cleve

Chancellor Leonhard von Eck (1480–1550)

Barthel Beham

Anne de Pisseleu (1508–1576), Duchesse d'Étampes

Attributed to Corneille de Lyon

Virgin and Child with Saint Anne

Christ and the Adulteress

Lucas Cranach the Younger and Workshop

The Calling of Saint Matthew

Copy after Jan Sanders van Hemessen

Christ Blessing the Children

Satire on the Papacy

Melchior Lorck

Christ Blessing, Surrounded by a Donor Family

German Painter

Jacob Wisse Stern College for Women, Yeshiva University

October 2002

Unleashed in the early sixteenth century, the Reformation put an abrupt end to the relative unity that had existed for the previous thousand years in Western Christendom under the Roman Catholic Church . The Reformation, which began in Germany but spread quickly throughout Europe, was initiated in response to the growing sense of corruption and administrative abuse in the church. It expressed an alternate vision of Christian practice, and led to the creation and rise of Protestantism, with all its individual branches. Images, especially, became effective tools for disseminating negative portrayals of the church ( 53.677.5 ), and for popularizing Reformation ideas; art, in turn, was revolutionized by the movement.

Though rooted in a broad dissatisfaction with the church, the birth of the Reformation can be traced to the protests of one man, the German Augustinian monk Martin Luther (1483–1546) ( 20.64.21 ; 55.220.2 ). In 1517, he nailed to a church door in Wittenberg, Saxony, a manifesto listing ninety-five arguments, or Theses, against the use and abuse of indulgences, which were official pardons for sins granted after guilt had been forgiven through penance. Particularly objectionable to the reformers was the selling of indulgences, which essentially allowed sinners to buy their way into heaven, and which, from the beginning of the sixteenth century, had become common practice. But, more fundamentally, Luther questioned basic tenets of the Roman Church, including the clergy’s exclusive right to grant salvation. He believed human salvation depended on individual faith, not on clerical mediation, and conceived of the Bible as the ultimate and sole source of Christian truth. He also advocated the abolition of monasteries and criticized the church’s materialistic use of art. Luther was excommunicated in 1520, but was granted protection by the elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise (r. 1483–1525) ( 46.179.1 ), and given safe conduct to the Imperial Diet in Worms and then asylum in Wartburg.

The movement Luther initiated spread and grew in popularity—especially in Northern Europe, though reaction to the protests against the church varied from country to country. In 1529, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V tried, for the most part unsuccessfully, to stamp out dissension among German Catholics. Elector John the Constant (r. 1525–32) ( 46.179.2 ), Frederick’s brother and successor, was actively hostile to the emperor and one of the fiercest defenders of Protestantism. By the middle of the century, most of north and west Germany had become Protestant. King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509–47), who had been a steadfast Catholic, broke with the church over the pope’s refusal to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the first of Henry’s six wives. With the Act of Supremacy in 1534, Henry was made head of the Church of England, a title that would be shared by all future kings. John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion (1536) codified the doctrines of the new faith, becoming the basis for Presbyterianism. In the moderate camp, Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam (ca. 1466–1536), though an opponent of the Reformation, remained committed to the reconciliation of Catholics and Protestants—an ideal that would be at least partially realized in 1555 with the Religious Peace of Augsburg, a ruling by the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire granting freedom of worship to Protestants.

With recognition of the reformers’ criticism and acceptance of their ideology, Protestants were able to put their beliefs on display in art ( 17.190.13–15 ). Artists sympathetic to the movement developed a new repertoire of subjects, or adapted traditional ones, to reflect and emphasize Protestant ideals and teaching ( 1982.60.35 ; 1982.60.36 ; 71.155 ; 1975.1.1915 ). More broadly, the balance of power gradually shifted from religious to secular authorities in western Europe, initiating a decline of Christian imagery in the Protestant Church. Meanwhile, the Roman Church mounted the Counter-Reformation, through which it denounced Lutheranism and reaffirmed Catholic doctrine. In Italy and Spain, the Counter-Reformation had an immense impact on the visual arts; while in the North , the sound made by the nails driven through Luther’s manifesto continued to reverberate.

Wisse, Jacob. “The Reformation.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/refo/hd_refo.htm (October 2002)

Further Reading

Coulton, G. G. Art and the Reformation . 2d ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1953.

Koerner, Joseph Leo. The Reformation of the Image . Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004.

Additional Essays by Jacob Wisse

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Northern Mannerism in the Early Sixteenth Century .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Prague during the Rule of Rudolf II (1583–1612) .” (November 2013)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Burgundian Netherlands: Court Life and Patronage .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Burgundian Netherlands: Private Life .” (October 2002)

- Wisse, Jacob. “ Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569) .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528)

- Baroque Rome

- Elizabethan England

- The Papacy and the Vatican Palace

- The Papacy during the Renaissance

- Abraham and David Roentgen

- Ceramics in the French Renaissance

- The Crucifixion and Passion of Christ in Italian Painting

- European Tapestry Production and Patronage, 1400–1600

- Genre Painting in Northern Europe

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- How Medieval and Renaissance Tapestries Were Made

- Late Medieval German Sculpture: Images for the Cult and for Private Devotion

- Monasticism in Western Medieval Europe

- Music in the Renaissance

- Northern Mannerism in the Early Sixteenth Century

- Painting the Life of Christ in Medieval and Renaissance Italy

- Pastoral Charms in the French Renaissance

- Patronage at the Later Valois Courts (1461–1589)

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569)

- Portrait Painting in England, 1600–1800

- Portraiture in Renaissance and Baroque Europe

- Profane Love and Erotic Art in the Italian Renaissance

- Sixteenth-Century Painting in Lombardy

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1400–1600 A.D.

- Central Europe (including Germany), 1600–1800 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1400–1600 A.D.

- France, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Great Britain and Ireland, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Iberian Peninsula, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Low Countries, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Rome and Southern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- Venice and Northern Italy, 1400–1600 A.D.

- 16th Century A.D.

- 17th Century A.D.

- The Annunciation

- Baroque Art

- Central Europe

- Central Italy

- Christianity

- The Crucifixion

- Gilt Silver

- Great Britain and Ireland

- High Renaissance

- Holy Roman Empire

- Literature / Poetry

- Madonna and Child

- Monasticism

- The Nativity

- The Netherlands

- Northern Italy

- Printmaking

- Religious Art

- Renaissance Art

- Southern Italy

- Virgin Mary

Artist or Maker

- Beham, Barthel

- Cranach, Lucas, the Elder

- Cranach, Lucas, the Younger

- Daucher, Hans

- De Lyon, Corneille

- De Pannemaker, Pieter

- Dürer, Albrecht

- Holbein, Hans, the Younger

- Tom Ring, Ludger, the Younger

- Van Cleve, Joos

- Van Der Weyden, Goswijn

- Van Hemessen, Jan Sanders

- Van Orley, Bernard

- Recent changes

- Random page

- View source

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Create account

How did the Renaissance influence the Reformation

Did the Renaissance lead the Protestant Reformation? Without the Renaissance, it is difficult to imagine that the Protestant Reformation could have succeeded in Europe. The Renaissance placed human beings at the center of life and had shown that this world was not just a ‘vale of tears’ but could be meaningful, and it was possible for people to live without reference to the divine. [1] The Renaissance or ‘rebirth’ was influenced by the ideas of the ancient past and it drew from Roman and Greek civilization to provide a solution to current problems.

The Renaissance was a Pan-European phenomenon and changed the elites' mental worldview in Europe and the emerging middle class across the continent. The cultural movement was to have a profound impression on people’s worldview. The Renaissance produced the Humanists, who were educationalists and scholars; they sought truth and knowledge by re-examining classical texts and the bible. The Humanists' ideas, the growth in textual analysis, and the Northern Renaissance changed the intellectual landscape. They encouraged many Church reformers, such as Martin Luther, and they later broke with Rome and divided Europe into two confessional camps, Protestantism and Catholicism.

What was the Reformation

The Reformation is the schism that divided the Roman Catholic Church and ended the old unity of Christendom. The origins of the Reformation were in an attempt to reform the Church, there had been many attempts in the past to reform the Church, but they had all failed. By the early sixteenth century, there was a growing crescendo of calls for the Church's reform and an end to the clergy's immorality and corruption. [2]

The Reformation was not an attempt to divide the Roman Catholic Church, but it was an effort to reform it. The Catholic Church's failure to reform and its attempts to suppress the Reformers meant that it drove many to establish their own churches. The Reformation was an attempt to return to the original teachings and values of the early or ‘Apostolic’ Church. [3]

The Reformers claimed that only the Bible could teach and instruct men about the Word of God and had little regard for the received wisdom and authority. Essentially, the only text that mattered was the Bible, and anything that was not in the Bible should be rejected. The Reformation placed more emphasis on the individual, and in words, people could not be saved by good works or sacrament but by ‘faith alone.’ [4]

Ultimately, this interpretation meant that the reformers rejected much of the Church's traditional teachings and resulted in at first a theological dispute between the reformers and the Church, especially in Germany. This dispute led to a full-blown schism in the Catholic Church and the formation of separate Protestant Churches. The causes of the Reformation were manifold, but the Renaissance and the Humanist movement were crucial and indeed decisive. [5]

The Renaissance and Religion

The Renaissance is often seen as a secular and even pagan movement that was anti-Christian in many ways. This view was certainly true in Italy, the birthplace of the Renaissance. The humanists were particularly worldly and had little interest in the Church. [6] Several early Italian humanists, such as Petrarch, sought to reform the Church, but his successors were largely secular in outlook and concerns. Many humanists were interested in reforming the Church, but in the main, the Church and religion was not a major preoccupation of the Italian humanists. However, there were many Renaissances, and the movement took different forms in other countries. [7] .

The ideas of the Italian Renaissance found their way to the North of Europe at a time when there was a receptive audience for them. The Renaissance ideas and the works of classical writers were transmitted throughout northern Europe by the new printing press and led to the Northern Renaissance. The Northern Renaissance is the term given to the cultural flowering north of the Alps, German-speaking countries, France, England, and elsewhere.

Although influenced by the Italian Renaissance, the Northern Renaissance was a unique event and was different in some crucial regards. [8] It was also interesting in the ancient past. It believed that it offered an alternative view of what life could be and could even provide practical guidance on how people should live and organize their societies. However, Northern Europe was much more religious in its concerns that the Italian Renaissance. [9]

The Northern Humanists made the reform of the Church their chief preoccupation. Many German, English, and other Northern Humanists saw no contradictions between Christianity and the study of ancient cultures and believed that they could be reconciled. [10] The religious character of the Renaissance north of the Alp was due in part to the continuing influence of the Church, unlike in Italy, where its, was in decline.

Despite the often deplorable state of the Church, the general population and even the elite remained very religious. The demand for the reform of the Church was prevalent and was a particular preoccupation of the elite. The desire for Church reform can be seen in the works of major Northern Renaissance figures such as Thomas More or Rabelais, who satirized the abuses in the monasteries, in particular. [11]

The Northern Humanists inspired many people to become more strident in their demands for reforms and the end of abuses such as simony and clerical immorality. The works of Erasmus were particularly crucial in this regard. In his much admired and widely read book ‘In Praise of Folly,’ he lampooned and ridiculed corrupt clerics and immoral monks. [12]

The Northern humanists' attacks on the Church did much to encourage others to see it in the new light. They became less deferential to the clergy, which led many of them to support the Reformers when they attempted to end the Church's corruption. [13] Previously, many people believed that the Church was not capable of reforming itself and accepted it. The humanists believed in reasons and the possibility of progress in all aspects of human life. They argued that what was happening at present was not fated to be and could be improved and changed, contrary to the medieval view of an unchanging and fixed order. This belief in the possibility of change inspired many people to seek real and meaningful changes in the church, and when they failed to secure these, they sought to create alternative churches. [14]

Humanism and the Church

The humanists were intellectuals who were mostly interested in scholarly pursuits. They sought to understand the ancient world, find answers and knowledge, and study ancient texts to achieve this. They wanted to go back to the original texts to understand the past and wanted to remove medieval corruptions and additions to texts. Their cry was ‘Ad Fontas’ in Latin, which is in English ‘to the sources.’ [15] They studied the ancient texts and developed textual strategies to understand the classical past's great works.

The Humanists were better able to understand the works of the past after developing ways to analyze texts. The development of textual criticism was not only of academic interest but was to change how people came to see the Church and were ultimate to undermine the authority of the Pope. The Church's power rested on the authority of the Pope and the prelates, which was ultimately based on tradition. [16]

The humanists employed their textual analysis and techniques to the bible and other works, and they made some astonishing discoveries. They provided evidence that undermined the claims of the Catholic Church. Ironically, a humanist employed by the Pope was one of the first to discredit the traditional authority of the Papacy in the Renaissance. The Pope was not just a spiritual leader, but he claimed to have real political power. The Pontiffs were masters of the Papal States in central Italy, and many even believed that Europe's monarchs were subject to their judgment. This was based on the Donation of Constantine, a document from the first Christian Emperor, which purported to show that he had bequeathed his authority to the Popes. [17]

This document was used to justify the Pope’s temporal power. An Italian humanist named Lorenzo Valla began to study this document historically. He found that it was written in a Latin style from the 8th century and long after Constantine's death. Valla showed that the document was a forgery. This information and other revelations helped to weaken the Pope's authority and emboldened reformers to challenge the Church. Erasmus did much to discredit the Church's traditional theology when he discovered that the words in the Catholic Bible about the Trinity (that God has three persons) were not in the earliest versions. [18]

Erasmus argued that the Catholic Church had added the words to support some statements agreed at a Church Council in the Roman era. Once again, by returning to the sources, medieval corruption was discovered, and old assumptions proved to be false, which weakened the Catholic Church's position. [19]

Papal Infallibility

The Humanists were not revolutionaries. They were often social conservatives and usually devout Catholics. This can be seen in the great Erasmus and his friend, the English statesman and writer Thomas More. However, in their interrogation and examination of texts and their desire to purge them of any medieval corruptions or additions, they changed how people viewed the Church. The work of Erasmus and other scholars did much to weaken the Papacy. [20] Their examination of key texts revealed that much of the authority of the Church was built on flimsy foundations. This led many to challenge the power of the Pope. As the Church leader, he was infallible, and his words on secular and religious issues were to be obeyed without question.

After the humanists’ revelations, many of the faithful began to wonder if the Pope. ‘as the heir of St Peter’ was infallible and should he be rendered unquestioned obedience. [21] The reformers under the influence of the Humanists began to examine the Bible, which they saw as the unquestioned Word of God, to find answers. They became less inclined to take the words of the Pope as law and argued that only the Bible was the source of authority. Like the Humanists, they decided to go back to the ‘sources,’ in this case, the Bible. They eventually came to see the Bible as the only source of authority. They increasingly began to view the Pope and the Catholic Church as having distorted the Gospels' message. [22] This belief soon gained widespread currency among many Reformers and those sympathetic to them in Germany and elsewhere.

The Renaissance was a cultural flourishing that promoted secular values over religious values. However, in Northern Europe, the ideas of the Renaissance were to take on a religious character. The ideas of the Italian humanists, such as textual analysis, the use of critical thinking, and rejecting authority that was not sourced on reliable evidence were taken up by Northern Humanists who applied them to the Church. [23]

The Northern Humanists sought to reform the Church and were generally pious men. However, the humanists perhaps unintentionally weakened the Papacy and its theoretical underpinnings. In their examination of key texts and especially the Bible, they exposed many key assumptions as false. This was to lead to a widespread challenge to the idea of Papal Infallibility and the Church's power structure. [24] The Renaissance also encouraged people to question received wisdom and offered the possibility of change, which was unthinkable in the middle ages. This encouraged the reformers to tackle abuses in the Church, which ultimately led to the schism and the end of Christendom's old idea.

Related DailyHistory.org Articles

- How did the Bubonic Plague make the Italian Renaissance possible?

- Top 10 Books on the origins of the Italian Renaissance

- Why did the Reformation fail in Renaissance Italy?

- What were the causes of the Northern Renaissance?

- Why did the Italian Renaissance End?

- ↑ Giustiniani, Vito. "Ho, mo, Humanus, and the Meanings of Humanism," Journal of the History of Ideas 46 (vol. 2, April – June 1985), p 178

- ↑ Payton Jr. James R. Getting the Reformation Wrong: Correcting Some Misunderstandings (IVP Academic, 2010), p. 78

- ↑ Payton, p. 113

- ↑ Payton, p. 118

- ↑ Patrick, James. Renaissance and Reformation (New York: Marshall Cavendish, 2007), p. 113

- ↑ Patrick, p 115

- ↑ Payton, p. 45

- ↑ Patrick, p. 123

- ↑ Chipps Smith, Jeffrey. The Northern Renaissance . (Phaidon Press, 2004), p. 167

- ↑ Chipps, p 119

- ↑ Patrick, p. 145

- ↑ O'Neill, J, ed. The Renaissance in the North . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1987), p. 5

- ↑ Collinson, Patrick. The Reformation: A History (Longman, London, 2006), p.87

- ↑ Collinson, p. 56

- ↑ Payton, p. 57

- ↑ Patrick, p. 121

- ↑ Davies, Tony. Humanism (The New Critical Idiom) . (University of Stirling, UK. Routledge, 1997), p 34

- ↑ Davies, p 67

- ↑ Davies, p. 134

- ↑ Payton. P. 34

- ↑ Patrick, p 117

- ↑ Collinson, p. 115

- ↑ Chipps, p. 67

- ↑ Chipps, p. 17

Updated, January 28, 2019.

Admin , Ewhelan and EricLambrecht

- Italian History

- Renaissance History

- European History

- Religious History

- This page was last edited on 15 September 2021, at 05:21.

- Privacy policy

- About DailyHistory.org

- Disclaimers

- Mobile view

Legacies of the Renaissance and Reformation Essay

Introduction, evolution of reformation movement in england, historiography of the renaissance and reformation.

Bibliography

The Renaissance and Reformation were some of the most significant events of human history that shaped the future of the world. Many contemporary and modern researchers contributed to reviewing and analyzing the impacts of the changes that happened in the period from 1527 to 1625 in England. The exceptional volume of the innovations introduced to the life of people and the developmental power it had on the country appears to trace the connections of those changes in the 21st century. In this essay, the evolution of the English reformation movement and Renaissance will be discussed in relation to the consequences these events had on the 21st century with evidence drawn from contemporary and modern sources.

Reformation in England concerns the period from 1527 to 1625 when the principles of the Catholic faith were challenged across many European states. As claimed by many historians, one of the first events that triggered the change was the request of Henry VIII to annul his marriage which is considered a politicized matter rather than a theological one. Later, however, it evolved into religious disputes and reassessment of Catholic religious doctrine in many aspects. The main underpinnings of the Reformation still happened in the political arena.

The Catholic doctrine at the time mostly presupposed the union of the church and monarch into a single political power, with the key sources of the political power being the pope and the king. The latter, on the other hand, desired broader freedom of decision-making and resorted to a doctrine that supported such nationalistic and absolutist aspirations. 1 The Supremacy Act of 1534 de-facto declared the submission of the church to the rule of the King of England not in all aspects but in a substantial portion of questions. 2

The harsh response from the pope triggered civil unrest in Ireland, Armada, and other lands under the British crown. Approximately at the same time, the church of England was established, yet its political and doctrinal status was disputed throughout the seventeenth century, which eventually was one of the precursors to the English Civil Wars. 3 As a result, the monarchy and the positions of the church were mostly restored. However, the reformation brought democratic liberties to the public, including the parliament that gained more power.

These events unfolded within the framework of the period in human history that was called the “renaissance” only in the 19th century by Jacob Burckhardt. According to Bireley, the Renaissance constituted five major areas of life that ensured the transition of Europe and England from a medieval state to early-modernity. 4 Among them were the political changes in the governance of the state, demographic, social, and economic alterations. The fifth change was predominantly concerning the reformation of faith institutions and the review of their position in the life of different layers of society. Printing aided the dissemination of information and increased the speed at which ideas traversed the world. Continuous conflicts between European monarchs and the Papacy eventually consolidated the authority of Kings over their countries on the grounds of their new source of religious power.

The demographic and economic growth within urban areas predicted the emergence of the new social class, the bourgeoisie, from traders and artisans. The Renaissance was also imbued with literature, where drama and poetry witnessed a rise in the richness of themes and depth. Some of the finest works in the sphere of visual arts, music, and architecture, were produced in this period which marked the spiritual and educational growth of society. Given the number of above-mentioned innovations and events in the life of late-medieval England, the Reformation and Renaissance appear to have produced a significant impact on the country and the world.

In the 21st century, people enjoy many rights and freedoms guaranteed by the constitutions, including the freedom of religion, expression, dignity, and so on. 5 The roots of those rights were, arguably, born in the Reformation and Renaissance periods. Thus, the religious clashes between the Catholic and Protestant churches led to the acceptance of both within the borders of one state. The Protestant faith, due to the status it received after emerging victorious as the dominant doctrine in a number of European states, was exported to other nations and now represents one of the pillars of the Christian world. 6

The expression and dissemination of revolutionary ideas aided by print evolved eventually into the freedom of speech, and the continual practice was forged into the law. Thus, the echo of reformation and renaissance helped shape many pillars of 21st-century society.

The views of contemporaries on the events of the reformation were different from the ones expressed by modern intellectuals and academics in several aspects. Modern historians are privileged with the benefits of retrospection and the ability to create a more or less full picture of the political, economic, and social situation on a large scale. The contemporary thinkers were often immersed in a much smaller information field.

Thus, Mandelbrote argues about the practice of religious toleration being the weapon turned against the Catholics by many theologians and social activists. 7 He draws evidence from a variety of sources and quotes many contemporaries such as John Strype and a vast body of 20th-and 21st-century research. Richard Baxter, a Puritan poet and a theologian, in his writings, draw conclusions about the causes of English Civil Wars mostly on observations and anecdotal evidence. 8

Baxter explains the reasons or “fundamental” of the Civil War. He claims that it was lawful because of the rebellion instigated by Charles I and Irish Catholics. Also, given the pro-Catholic teachings of Laud and others, a retaliation of Puritans that followed was justified. Puritans, as he highlights, were not the originators of this war and were mostly “unrevolutionary” in their beliefs. 9

Here the business of his views can be attributed to his adherence to the Puritan teachings. Modern historians are not exempt from bias, yet in questions of religion, they tend to consider more than one side of the issue and base their assumptions on a variety of sources. In addition, the tensions between Catholic and protestant churches, if not entirely gone, have subsided sufficiently through the ages. Orr, a modern historian, tends to offer a more analytical approach and strives to be impartial. He claims the reasons for war to be purely religious, yet he also argues that it was a struggle for power. 10

Among other things, he establishes that the views of personal rule and the role of the parliament were what drew the line between Charles I and puritans. 11 Von Ranke, who contributed substantially to the development of modern history, also tended to use multiple sources. 12 Thus there is a significant difference between the historiography of modern and contemporary academics.

The roots of the privileges and freedoms granted to people today can be found in the reformation and renaissance period. The fundamental changes that took place at that time significantly influenced the political and social ordinance of the word. Yet, there is a difference in the way contemporaries viewed the historical events. While modern intellectuals use the power of a wide variety of sources and try to stay objective, contemporary academics express their own views and employ anecdotal evidence.

Bireley, Robert. “Early-Modern Catholicism as a Response to the Changing World of the Long Sixteenth Century.” The Catholic Historical Review 95, no. 2 (2009): 219-239.

Bold, Andreas. “ Perception, Depiction and Description of European History: Leopold von Ranke and his Development and Understanding of Modern Historical Writing. ” National University of Ireland , n.d.. Web.

Karant-Nunn, Susan, and Lotz-Heumann, Ute. “Confessional Conflict. After 500 Years: Print and Propaganda in the Protestant Reformation.” University of Arizona Libraries , 2017. Web.

Lamont, William. “Richard Baxter, ‘Popery’ and the Origins of the English Civil War.” History 87, no. 287 (2002): 336-352.

Mandelbrote, Scott. “Religious Belief and the Politics of Toleration in the Late Seventeenth Century.” Dutch Review of Church History 81, no. 2 (2001): 93-114.

Orr, Alan. “Sovereignty, Supremacy and the Origins of the English Civil War.” History 87, no. 288 (2002): 474-490.

Weber, Wolfgang. ““What a Good Ruler Should Not Do”: Theoretical Limits of Royal Power in European Theories of Absolutism, 1500-1700.” Sixteenth Century Journal 26, no. 4 (1995): 897-915.

- Wolfgang Weber, ““What a Good Ruler Should Not Do”: Theoretical Limits of Royal Power in European Theories of Absolutism, 1500-1700,” Sixteenth Century Journal 26, no. 4 (1995): 897.

- Alan Orr, “Sovereignty, Supremacy and the Origins of the English Civil War,” History 87, no. 288 (2002): 477.

- Weber, “What a Good Ruler Should Not Do,” p. 899.

- Robert Bireley, “Early-Modern Catholicism as a Response to the Changing World of the Long Sixteenth Century,” The Catholic Historical Review 95, no. 2 (2009): 221.

- Susan Karant-Nunn and Ute Lotz-Heumann, “Confessional Conflict. After 500 Years: Print and Propaganda in the Protestant Reformation,” University of Arizona Libraries , 2017. Web.

- Karen-Nunn and Lotz-Heumann, Confessional Conflict .

- Scott Mandelbrote, “Religious Belief and the Politics of Toleration in the Late Seventeenth Century,” Dutch Review of Church History 81, no. 2 (2001): 93.

- William Lamont, “Richard Baxter, ‘Popery’ and the Origins of the English Civil War,” History 87, no. 287 (2002): 336.

- Lamont, “Richard Baxter, ‘Popery’ and the Origins of the English Civil War,” 339.

- Orr, “Sovereignty, Supremacy and the Origins,” 490.

- Andreas Bold, “Perception, Depiction and Description of European History: Leopold von Ranke and his Development and Understanding of Modern Historical Writing,” National University of Ireland , n.d. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, July 16). Legacies of the Renaissance and Reformation. https://ivypanda.com/essays/legacies-of-the-renaissance-and-reformation/

"Legacies of the Renaissance and Reformation." IvyPanda , 16 July 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/legacies-of-the-renaissance-and-reformation/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Legacies of the Renaissance and Reformation'. 16 July.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Legacies of the Renaissance and Reformation." July 16, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/legacies-of-the-renaissance-and-reformation/.

1. IvyPanda . "Legacies of the Renaissance and Reformation." July 16, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/legacies-of-the-renaissance-and-reformation/.

IvyPanda . "Legacies of the Renaissance and Reformation." July 16, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/legacies-of-the-renaissance-and-reformation/.

- Herodotus and Thucydides' Contributions to Greek Historiography

- Early Greek, Roman, and Christian Historiography

- Japan's, China's, South Korea's Historical Legacies

- Historiography of East, West Frameworks on Eastern European Women During Communist Era

- An Analysis of Pop Art: Origins, Styles and Legacies

- Family Legacies

- Historiography of Science and the Scientific Revolution

- Jarzombek’s Analysis of Architectural History and Historiography

- Evolutionary Theory and Linguistics in Africa's Historiography

- Historiography: Definition and Mission

- The Presence of the British Empire on Tibet

- Summarized Outlook of the Victorian Age

- Social and Cultural Life in England Throughout History

- The Portuguese Empire of 16th Century Under Prince Henry

- Industrial Revolution: Technological Advancements and Society

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Renaissance

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 11, 2023 | Original: April 4, 2018

The Renaissance was a fervent period of European cultural, artistic, political and economic “rebirth” following the Middle Ages. Generally described as taking place from the 14th century to the 17th century, the Renaissance promoted the rediscovery of classical philosophy, literature and art.

Some of the greatest thinkers, authors, statesmen, scientists and artists in human history thrived during this era, while global exploration opened up new lands and cultures to European commerce. The Renaissance is credited with bridging the gap between the Middle Ages and modern-day civilization.

From Darkness to Light: The Renaissance Begins

During the Middle Ages , a period that took place between the fall of ancient Rome in 476 A.D. and the beginning of the 14th century, Europeans made few advances in science and art.

Also known as the “Dark Ages,” the era is often branded as a time of war, ignorance, famine and pandemics such as the Black Death .

Some historians, however, believe that such grim depictions of the Middle Ages were greatly exaggerated, though many agree that there was relatively little regard for ancient Greek and Roman philosophies and learning at the time.

During the 14th century, a cultural movement called humanism began to gain momentum in Italy. Among its many principles, humanism promoted the idea that man was the center of his own universe, and people should embrace human achievements in education, classical arts, literature and science.

In 1450, the invention of the Gutenberg printing press allowed for improved communication throughout Europe and for ideas to spread more quickly.

As a result of this advance in communication, little-known texts from early humanist authors such as those by Francesco Petrarch and Giovanni Boccaccio, which promoted the renewal of traditional Greek and Roman culture and values, were printed and distributed to the masses.

Additionally, many scholars believe advances in international finance and trade impacted culture in Europe and set the stage for the Renaissance.

Medici Family

The Renaissance started in Florence, Italy, a place with a rich cultural history where wealthy citizens could afford to support budding artists.

Members of the powerful Medici family , which ruled Florence for more than 60 years, were famous backers of the movement.

Great Italian writers, artists, politicians and others declared that they were participating in an intellectual and artistic revolution that would be much different from what they experienced during the Dark Ages.

The movement first expanded to other Italian city-states, such as Venice, Milan, Bologna, Ferrara and Rome. Then, during the 15th century, Renaissance ideas spread from Italy to France and then throughout western and northern Europe.

Although other European countries experienced their Renaissance later than Italy, the impacts were still revolutionary.

Renaissance Geniuses

Some of the most famous and groundbreaking Renaissance intellectuals, artists, scientists and writers include the likes of:

- Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519): Italian painter, architect, inventor and “Renaissance man” responsible for painting “The Mona Lisa” and “The Last Supper.

- Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536): Scholar from Holland who defined the humanist movement in Northern Europe. Translator of the New Testament into Greek.

- Rene Descartes (1596–1650): French philosopher and mathematician regarded as the father of modern philosophy. Famous for stating, “I think; therefore I am.”

- Galileo (1564-1642): Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer whose pioneering work with telescopes enabled him to describes the moons of Jupiter and rings of Saturn. Placed under house arrest for his views of a heliocentric universe.

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543): Mathematician and astronomer who made first modern scientific argument for the concept of a heliocentric solar system.

- Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679): English philosopher and author of “Leviathan.”

- Geoffrey Chaucer (1343–1400): English poet and author of “The Canterbury Tales.”

- Giotto (1266-1337): Italian painter and architect whose more realistic depictions of human emotions influenced generations of artists. Best known for his frescoes in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua.

- Dante (1265–1321): Italian philosopher, poet, writer and political thinker who authored “The Divine Comedy.”

- Niccolo Machiavelli (1469–1527): Italian diplomat and philosopher famous for writing “The Prince” and “The Discourses on Livy.”

- Titian (1488–1576): Italian painter celebrated for his portraits of Pope Paul III and Charles I and his later religious and mythical paintings like “Venus and Adonis” and "Metamorphoses."

- William Tyndale (1494–1536): English biblical translator, humanist and scholar burned at the stake for translating the Bible into English.

- William Byrd (1539/40–1623): English composer known for his development of the English madrigal and his religious organ music.

- John Milton (1608–1674): English poet and historian who wrote the epic poem “Paradise Lost.”

- William Shakespeare (1564–1616): England’s “national poet” and the most famous playwright of all time, celebrated for his sonnets and plays like “Romeo and Juliet."

- Donatello (1386–1466): Italian sculptor celebrated for lifelike sculptures like “David,” commissioned by the Medici family.

- Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510): Italian painter of “Birth of Venus.”

- Raphael (1483–1520): Italian painter who learned from da Vinci and Michelangelo. Best known for his paintings of the Madonna and “The School of Athens.”

- Michelangelo (1475–1564): Italian sculptor, painter and architect who carved “David” and painted The Sistine Chapel in Rome.

Renaissance Impact on Art, Architecture and Science

Art, architecture and science were closely linked during the Renaissance. In fact, it was a unique time when these fields of study fused together seamlessly.

For instance, artists like da Vinci incorporated scientific principles, such as anatomy into their work, so they could recreate the human body with extraordinary precision.

Architects such as Filippo Brunelleschi studied mathematics to accurately engineer and design immense buildings with expansive domes.

Scientific discoveries led to major shifts in thinking: Galileo and Descartes presented a new view of astronomy and mathematics, while Copernicus proposed that the Sun, not the Earth, was the center of the solar system.

Renaissance art was characterized by realism and naturalism. Artists strived to depict people and objects in a true-to-life way.

They used techniques, such as perspective, shadows and light to add depth to their work. Emotion was another quality that artists tried to infuse into their pieces.

Some of the most famous artistic works that were produced during the Renaissance include:

- The Mona Lisa (Da Vinci)

- The Last Supper (Da Vinci)

- Statue of David (Michelangelo)

- The Birth of Venus (Botticelli)

- The Creation of Adam (Michelangelo)

Renaissance Exploration

While many artists and thinkers used their talents to express new ideas, some Europeans took to the seas to learn more about the world around them. In a period known as the Age of Discovery, several important explorations were made.

Voyagers launched expeditions to travel the entire globe. They discovered new shipping routes to the Americas, India and the Far East and explorers trekked across areas that weren’t fully mapped.

Famous journeys were taken by Ferdinand Magellan , Christopher Columbus , Amerigo Vespucci (after whom America is named), Marco Polo , Ponce de Leon , Vasco Núñez de Balboa , Hernando De Soto and other explorers.

Renaissance Religion

Humanism encouraged Europeans to question the role of the Roman Catholic church during the Renaissance.

As more people learned how to read, write and interpret ideas, they began to closely examine and critique religion as they knew it. Also, the printing press allowed for texts, including the Bible, to be easily reproduced and widely read by the people, themselves, for the first time.

In the 16th century, Martin Luther , a German monk, led the Protestant Reformation – a revolutionary movement that caused a split in the Catholic church. Luther questioned many of the practices of the church and whether they aligned with the teachings of the Bible.

As a result, a new form of Christianity , known as Protestantism, was created.

End of the Renaissance

Scholars believe the demise of the Renaissance was the result of several compounding factors.

By the end of the 15th century, numerous wars had plagued the Italian peninsula. Spanish, French and German invaders battling for Italian territories caused disruption and instability in the region.

Also, changing trade routes led to a period of economic decline and limited the amount of money that wealthy contributors could spend on the arts.

Later, in a movement known as the Counter-Reformation, the Catholic church censored artists and writers in response to the Protestant Reformation. Many Renaissance thinkers feared being too bold, which stifled creativity.

Furthermore, in 1545, the Council of Trent established the Roman Inquisition , which made humanism and any views that challenged the Catholic church an act of heresy punishable by death.

By the early 17th century, the Renaissance movement had died out, giving way to the Age of Enlightenment .

Debate Over the Renaissance

While many scholars view the Renaissance as a unique and exciting time in European history, others argue that the period wasn’t much different from the Middle Ages and that both eras overlapped more than traditional accounts suggest.

Also, some modern historians believe that the Middle Ages had a cultural identity that’s been downplayed throughout history and overshadowed by the Renaissance era.

While the exact timing and overall impact of the Renaissance is sometimes debated, there’s little dispute that the events of the period ultimately led to advances that changed the way people understood and interpreted the world around them.

HISTORY Vault: World History

Stream scores of videos about world history, from the Crusades to the Third Reich.

The Renaissance, History World International . The Renaissance – Why it Changed the World, The Telegraph . Facts About the Renaissance, Biography Online . Facts About the Renaissance Period, Interestingfacts.org . What is Humanism? International Humanist and Ethical Union . Why Did the Italian Renaissance End? Dailyhistory.org . The Myth of the Renaissance in Europe, BBC .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

What was the Reformation? What relations can you identify and trace between the Renaissance and the Reformation.

What was the Reformation? What relations can you identify and trace between the Renaissance and the Reformation, The Renaissance and the Reformation, two monumental epochs in the annals of human history, have profoundly shaped the course of literature, thought, and society.

Table of Contents

The Renaissance, characterized by a resurgence of interest in classical learning and the arts, unfolded its vibrant petals in the 14th to 17th centuries. Simultaneously, the Reformation, led by prominent figures such as Martin Luther and John Calvin, sought to reform the Roman Catholic Church, culminating in the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. While seemingly distinct, these movements shared intricate relationships, interweaving ideas, and a profound influence on the literary landscape of their times. This essay explores the interplay between the Renaissance and the Reformation, delving into their shared themes, their impact on literature, and the ways in which they shaped the intellectual milieu of their eras.

What was the Reformation

The Reformation was a significant religious and historical movement that took place in Europe during the 16th century. It was a period of religious upheaval, reform, and transformation, primarily within the Christian Church, which had far-reaching consequences for both religious and political structures across the continent. The Reformation is often associated with key figures like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli, who played pivotal roles in challenging the authority and practices of the Roman Catholic Church and promoting the emergence of Protestant Christianity.

The Renaissance and its Literary Resurgence

The Renaissance, a rebirth of humanism, witnessed a fervent revival of classical Greek and Roman literature, philosophy, and art. This cultural awakening spurred a newfound appreciation for the human experience, individualism, and the power of reason. Renaissance thinkers, often referred to as “Renaissance men,” exemplified this blend of humanism and intellectual exploration. Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks, containing meticulous anatomical drawings and scientific observations, exemplify the fusion of art and science during this period. What was the Reformation? What relations can you identify and trace between the Renaissance and the Reformation.

Literature during the Renaissance reflected this renewed interest in the human condition and the world. William Shakespeare, the iconic playwright of the era, produced masterpieces like “Hamlet” and “Macbeth,” which delved into the complexities of human nature and morality. The sonnets of Petrarch, an Italian poet, embodied the Renaissance’s fascination with love and beauty. These literary works showcased a profound shift towards secularism and the exploration of human emotions and desires.

The Reformation and Its Theological Schism

Concurrently, the Reformation was brewing in Europe, spearheaded by reformers like Martin Luther, John Calvin, and Huldrych Zwingli. At its core, the Reformation was a theological movement that challenged the authority and practices of the Roman Catholic Church. Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses, famously nailed to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg in 1517, catalyzed the schism. The Protestant Reformation questioned the sale of indulgences, emphasized salvation through faith alone, and advocated for the translation of the Bible into vernacular languages.

Literature played a pivotal role in disseminating Reformation ideas. Luther’s translation of the Bible into German made scripture accessible to the masses, fostering greater religious literacy. His pamphlets, such as “Address to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation,” ignited discussions about reforming the church’s corruption. John Calvin’s “Institutes of the Christian Religion” provided a systematic theological framework for Protestantism, influencing the theological discourse.

Convergence: Shared Themes and Motifs

The Renaissance and the Reformation, seemingly distinct movements, shared themes and motifs that converged in literature. One prominent theme was the quest for knowledge and truth. Renaissance humanists, inspired by the revival of classical learning, sought knowledge through reason and empirical observation. In contrast, Reformation thinkers sought religious truth through the study of scripture and direct communication with God. The pursuit of truth, whether in the natural world or in theology, was central to both movements.

For instance, Sir Thomas More’s “Utopia” (1516) is a literary work that reflects the intellectual climate of the Renaissance. More, a humanist, presented a utopian society that emphasized reason, education, and the pursuit of knowledge. This vision echoed the Renaissance’s belief in the potential for human progress through intellectual endeavors.

Similarly, John Milton’s epic poem “Paradise Lost” (1667) emerged from the confluence of Renaissance and Reformation ideas. While Milton was deeply influenced by Renaissance humanism and its literary traditions, he also grappled with theological themes, particularly the fall of humanity and the concept of free will. “Paradise Lost” explores these themes through the retelling of the biblical story of Adam and Eve.

The Impact on Literature

The interplay between the Renaissance and the Reformation had a profound impact on literature, shaping its form and content. The Renaissance’s celebration of humanism and individualism paved the way for a diverse range of literary genres and styles. This period saw the emergence of the essay as a literary form, with Michel de Montaigne’s “Essays” (1580) being a prime example. Montaigne’s essays delved into various topics, offering a personal and reflective perspective, a hallmark of Renaissance literature.

The Reformation, on the other hand, had a significant impact on religious literature. Hymns and devotional writings became prominent forms of expression for Protestant beliefs. Notable examples include Martin Luther’s hymn “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God” and John Bunyan’s allegorical work “The Pilgrim’s Progress” (1678), which vividly portrays the spiritual journey of a Christian believer.

Moreover, the Reformation’s emphasis on the vernacular languages paved the way for the development of national literatures. Luther’s translation of the Bible into German contributed to the standardization and enrichment of the German language, laying the foundation for modern German literature. Similarly, the English King James Version of the Bible (1611) played a pivotal role in shaping the English language and influencing subsequent literary works.

Intellectual Milieu and Legacy

The Renaissance and the Reformation not only influenced contemporary literature but also laid the groundwork for the Enlightenment, an intellectual movement of the 18th century characterized by reason, secularism, and a focus on individual rights and freedoms. Enlightenment thinkers, such as Voltaire, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau, built upon the foundations established during the Renaissance and Reformation periods.

The Reformation’s emphasis on individual interpretation of scripture contributed to the Enlightenment’s promotion of religious tolerance and the separation of church and state. The Renaissance’s celebration of human reason and inquiry influenced Enlightenment philosophy, with René Descartes’ famous statement “Cogito, ergo sum” (“I think, therefore I am”) epitomizing the era’s rationalism.

In the intricate tapestry of human history and literature, the Renaissance and the Reformation stand as two vibrant threads that, though distinct in their origins, intertwined to form a rich and complex pattern. The Renaissance celebrated humanism, reason, and the pursuit of knowledge, fostering a literary landscape of diverse genres and styles. Simultaneously, the Reformation, driven by theological fervor, used literature to disseminate reformist ideas and promote religious literacy.

These movements converged on shared themes such as the quest for truth and left an indelible mark on literature, influencing genres and shaping national languages. Their legacy extended beyond their respective eras, serving as a fertile intellectual ground for the Enlightenment.

Ultimately, the interplay between the Renaissance and the Reformation reminds us of the enduring power of ideas to shape societies and inspire the literary imagination. Their profound impact on literature continues to resonate with readers and scholars, inviting us to explore the complex relationship between faith, reason, and human creativity. What was the Reformation? What relations can you identify and trace between the Renaissance and the Reformation.

Related Posts

The 48 Laws of Power Summary Chapterwise by Robert Greene

What is precisionism in literature, what is the samuel johnson prize.

Attempt a critical appreciation of The Triumph of Life by P.B. Shelley.

Consider The Garden by Andrew Marvell as a didactic poem.

Why does Plato want the artists to be kept away from the ideal state

MEG 05 LITERARY CRITICISM & THEORY Solved Assignment 2023-24

William Shakespeare Biography and Works

Discuss the theme of freedom in Frederick Douglass’ Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass

How does William Shakespeare use the concept of power in Richard III

Analyze the use of imagery in William Shakespeare’s sonnets

In which novel does the character “babaray” appear, who wrote “the magic pudding”, the significance of the title “jasper jones”, which australian author wrote “the slap”.

- Advertisement

- Privacy & Policy

- Other Links

© 2023 Literopedia

Welcome Back!

Login to your account below

Remember Me

Retrieve your password

Please enter your username or email address to reset your password.

Are you sure want to unlock this post?

Are you sure want to cancel subscription.

The Reformation in European Civilization

How it works

The Renaissance and The Protestant Reformation, and the age of discovery, exploration, and exploitation transformed European Civilization into a more sophisticated and cosmopolitan civilization. The Renaissance is known for being the rebirth of learning and culture. It spread across Europe and helped to get a jumpstart in exploration, trade, and even war. The Black Death had killed off most of the people in Europe leaving those that survived to receive greater wealth and start over. This was due to inheritance or because of the need for supply and demand with having less workers had lead to increased wages.

Renaissance art began to form and was not only used to simply look pretty in households, but was also created to capture the beauty of the real world creating different perspectives. Along with art, advances in learning had began as well. New discoveries in chemistry started to increase the use of gun powder and new math techniques made it easier to find your way around the world. Because new Navigation was created, Christopher Columbus discovered America and the more research that was done, the more was found out about the world. New continents were found and new cultures were discovered. All of these scientific discoveries lead to what is known as the printing press which that alone, changed the world. The printing press allowed for books to be mass-produced for the very first time. This changed literature and history forever and allowed religion to be spread across the globe. The reformation started in 1517 when Luther made a list of his 95 theses and nailed it to the church door. People began to read these theses and spread the word which made the church angry. Luther claimed that what the church had been teaching was not in the Bible and that the pope’s right to be in charge should be taken away. This caused him to be separated from the church and since he did not retract his statements, he was excommunicated.

Because of Luther, the reformation changed European civilization through religion because people had different opinions on the Bible and started to do things that were not apart of their religion. For example, preachers would sell indulgences to people and make them believe that if they bought something from them, they automatically went to heaven when confessing what they did wrong. It provided the middle class a new religious legitimacy for their role in society and began female education and literacy. Violence, war, and religious coexistence also started from the protestant reformation. The age of discovery and exploration was when European sailors and ships left the Old World and set off to find something new. Originally what they found was called the other world but later began calling it the New World. Along with finding new continents, Europeans found natives and at first wanted to befriend them. Once gold and silver was discovered among the natives that was when European exploitation began. During the second voyage Christopher Columbus took, one of his captains took over a thousand Indians and held them captive. Five-hundred were taken on board of Spanish ships and 200 had died at sea while the others were treated cruelly. Europeans had also discovered spices in foreign countries and searched for an immediate trade route to India and the Far East to receive spices such as pepper, cinnamon, and cloves. Jared Diamond wrote the book, Guns, Germs, and Steel which talks about the Europeans and how they discovered and conquered the world.

This book mainly focuses on how European language and culture dominate the world today. Diamond argues that there is nothing special about European people or their culture except that they were in the right place at the right time. He claims that they took advantage of the opportunities that were given to them through climate, geography and the Middle East. Jared Diamond also states that race is not a factor because people are pretty much the same as one another and that if it had been anyone else that had settled in the middle east they would have reacted the same way. He supports his statement by including the common patterns of different conquests. The main reasoning Diamond uses, is that the best domesticated crops and animals are all native but can easily adapt to the climate of Europe. Wheat, barely, and other native crops are what was spread widely to Europe. The spread of agriculture was an example of how technology and culture tends to spread. The distance of these crops were a huge deal because during this time if someone wanted to go somewhere, their only form of transportation was by walking.

The next major step in change was the domestication of horses. This lead to more domesticated animals being brought over and used for their wool, milk, and food. Fourteen domesticated animals made their way to Europe and out of those, thirteen of them were native. Jared Diamond talks about how Europe did not have a lot of resources to begin with but was able to do significantly well once they found a way to get them. The crops and animals that were brought back to Europe were able to live a sustainable life because of the climate and soil in Europe. Jared Diamond believes that geography gave the Europeans luck which provided them with surpluses. Surpluses allowed them to make tools and to be able to make them more productively. However, the people overused the land of what is known as the Fertile Crescent and now because of that, the Middle East is doing poorly. The Europeans used their geographic advantages to an advantage and that is how they were able to conquer so much.

Cite this page

The Reformation in European Civilization. (2021, Apr 27). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reformation-in-european-civilization/

"The Reformation in European Civilization." PapersOwl.com , 27 Apr 2021, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reformation-in-european-civilization/

PapersOwl.com. (2021). The Reformation in European Civilization . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reformation-in-european-civilization/ [Accessed: 30 Apr. 2024]

"The Reformation in European Civilization." PapersOwl.com, Apr 27, 2021. Accessed April 30, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reformation-in-european-civilization/

"The Reformation in European Civilization," PapersOwl.com , 27-Apr-2021. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reformation-in-european-civilization/. [Accessed: 30-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2021). The Reformation in European Civilization . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-reformation-in-european-civilization/ [Accessed: 30-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section England, 1485-1642

Introduction.

- Reference Works

- Bibliographies

- Primary Source Collections

- Society and Culture

- Politics and Political Culture

- Crown and Nobility

- Wars of the Roses

- The Tudor Monarchy

- Tudor Political Culture

- Tudor Governance

- Court and Parliaments, 1500–1600

- Local and Urban Government

- Tudor Rebellions and Riots

- Foreign Policy

- Exploration and “Empire”

- Political Ideas

- James VI and I: Kingship and Political Culture

- The Early Stuart Church and the Episcopate

- Politics and Parliament, 1603–1640

- Charles I and the Personal Rule

- Crime and Punishment, Order and Disorder

- The Nobility

- The Gentry and the Middling Classes

- The Poor and Poverty

- Courtship, Gender, and Family

- Women in Tudor and Stuart England

- The Witch Hunt and Its Decline

- Science and Philosophy

- Print Culture and Literacy

- Popular Culture

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Anne Boleyn

- Edward IV, King of England

- Elizabeth Cary

- Elizabeth I, the Great, Queen of England

- English Overseas Empire

- English Puritans, Quakers, Dissenters, and Recusants

- English Reformation

- Female Monarchy in Renaissance and Reformation Europe

- France in the 16th Century

- Francis Bacon

- George Herbert

- Henry VIII, King of England

- Katherine Parr

- Margaret Beaufort

- Margery Kempe

- Mary Tudor, Queen of England

- Oliver Cromwell

- Polydore Vergil

- Revolutionary England, 1642-1702

- Richard III

- Royal Regencies in Renaissance and Reformation Europe, 1400–1700

- Sir Robert Cecil

- The Hundred Years War

- The Reformation

- The Thirty Years War

- Walter Ralegh

- Warfare and Military Organizations

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Mining and Metallurgy

- Pilgrimage in Early Modern Catholicism

- Racialization in the Early Modern Period

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

England, 1485-1642 by Sarah Covington LAST REVIEWED: 10 May 2010 LAST MODIFIED: 10 May 2010 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780195399301-0019

The scholarship on Tudor and Stuart England constitutes a parallel universe in its own right, with its sometimes acrimonious debates threatening to paralyze the student (and even specialist) from coming to any clarity or conclusions at all (unless, perhaps, he or she simply submits to the latest historiographical orthodoxy). Aside from the English Civil War, which has been called the “Mount Everest” of English scholarship, debates have centered upon whether the Reformation was “top down” or “bottom up”: religion as a whole was Protestant, Catholic, or something in between; the nobility and the gentry in crisis or ascendant; the Restoration representative of continuity or change; and the events of 1688 momentous, or not. Terms such as “revisionism,” “postrevisionism,” or “neo-Whiggism” convey such confusion, but they are unavoidable when it comes to entering, on a deeper level, the notoriously vexed scholarship of the period. Such debates also testify to the extremely rich nature of the Tudor and Stuart period in England, which continues to yield new insights, interpretations, and conclusions regarding political culture, social relations, the nature of religious belief and allegiance, or causality when it comes to an event as momentous as the civil war. The following entry is limited to the most important or representative works, including studies whose claims have been long discredited or put aside but nevertheless remain important in conveying the full scope of the research and conclusions yielded by the subject at hand. Many more sources (and subjects) could have been added, just as databases such as the Royal Historical Society’s annual bibliography continue to list hundreds of new books and articles each year.

A number of excellent textbooks exist on Tudor and Stuart England, though with the exception of Bucholz and Key 2009 and Smith 1997 , they tend to divide the Tudor and Stuart periods. Guy 1988 provides one of the best overviews of the Tudor age, with an emphasis on politics, while the 17th century is best represented by Kishlansky 1997 , which also focuses on politics, and Coward 2003 , which incorporates more extensive economic and social history. More recent studies such as Brigden 2000 and Nicholls 1999 have also taken care to incorporate Ireland (in Brigden’s case especially) and the British Isles into the history, and to provide some overview of the historiographical debates.

Brigden, Susan. New Worlds, Lost Worlds: The Rule of the Tudors, 1485–1603 . New York: Viking, 2000.

A well-presented narrative of the Tudor century, incorporating new approaches and particularly strong in its presentation of Ireland and the Atlantic world.

Bucholz, Robert, and Newton Key. Early Modern England, 1485–1714: A Narrative History . 2nd ed. London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

An excellent narrative and analytical approach that incorporates social, economic, religious, and cultural as well as political history.

Coward, Barry. The Stuart Age: England, 1603–1714 . 3d ed. London: Longman, 2003.

The best recent textbook on the Stuart age, utilizing the latest scholarship and focusing on the economy, society, and politics as well as the civil war and its aftermath. Very useful bibliographic essay at the end and relatively good coverage of Scotland and Ireland.

Guy, John. Tudor England . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Perhaps the best analytical narrative and overview of Tudor England, incorporating original research and conclusions. Above all a political history, the work concludes that the Tudor reigns, including Elizabeth’s, were in large part a success and certainly transformative of the English polity by the end of the century.

Kishlansky, Mark. A Monarchy Transformed: Britain, 1603–1714 . London: Penguin, 1997.

A clear and well-written political narrative designed for the student and nonspecialist, extending from the reign of James I through Anne and tracing developments in the institution of the monarchy and also including the parallel histories of Scotland and Ireland.

Nicholls, Mark. A History of the Modern British Isles, 1529–1603: The Two Kingdoms . Oxford: Blackwell, 1999.

An ambitious study that encompasses Wales, Scotland, and Ireland as well as England, including distinctly non-Anglocentric perspectives. Nicholls explicitly rejects the notion that any common or unifying “themes” underlay or brought together these kingdoms, nor that there was any idea or policy of “Britishness” other than the imposition of England’s will on others.

Smith, A. G. R. The Emergence of a Nation State: The Commonwealth of England, 1529–1660 . 2d ed. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education Ltd., 1997.

One of the best surveys of England, beginning with the Reformation and continuing through the English civil war, with useful introductions to the historiographical debates, and excellent maps, glossaries, and bibliography.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Renaissance and Reformation »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Aemilia Lanyer

- Agrippa d’Aubigné

- Alberti, Leon Battista

- Alexander VI, Pope

- Andrea del Verrocchio

- Andrea Mantegna

- Andreas Bodenstein von Karlstadt

- Anne Bradstreet

- Aretino, Pietro

- Ariosto, Ludovico

- Art and Science

- Art, German

- Art in Renaissance England

- Art in Renaissance Florence

- Art in Renaissance Siena

- Art in Renaissance Venice

- Art Literature and Theory of Art

- Art of Poetry

- Art, Spanish

- Art, 16th- and 17th-Century Flemish

- Art, 17th-Century Dutch

- Artemisia Gentileschi

- Ascham, Roger

- Askew, Anne

- Astell, Mary

- Astrology, Alchemy, Magic

- Augustinianism in Renaissance Thought

- Autobiography and Life Writing

- Avignon Papacy

- Bacon, Francis

- Banking and Money

- Barbaro, Ermolao, the Younger

- Barbaro, Francesco

- Baron, Hans

- Baroque Art and Architecture in Italy

- Barzizza, Gasparino

- Bathsua Makin

- Beaufort, Margaret

- Bellarmine, Cardinal

- Bembo, Pietro

- Benito Arias Montano

- Bernardino of Siena, San

- Beroaldo, Filippo, the Elder

- Bessarion, Cardinal

- Biondo, Flavio

- Bishops, 1550–1700

- Bishops, 1400-1550

- Black Death and Plague: The Disease and Medical Thought

- Boccaccio, Giovanni

- Bohemia and Bohemian Crown Lands

- Borgia, Cesare

- Borgia, Lucrezia

- Borromeo, Cardinal Carlo

- Bosch, Hieronymous

- Bracciolini, Poggio

- Brahe, Tycho

- Bruegel, Pieter the Elder

- Bruni, Leonardo

- Bruno, Giordano

- Bucer, Martin

- Budé, Guillaume

- Buonarroti, Michelangelo

- Burgundy and the Netherlands

- Calvin, John

- Camões, Luís de

- Cardano, Girolamo

- Cardinal Richelieu

- Carvajal y Mendoza, Luisa De

- Cary, Elizabeth

- Casas, Bartolome de las

- Castiglione, Baldassarre

- Catherine of Siena

- Catholic/Counter-Reformation

- Catholicism, Early Modern

- Cecilia del Nacimiento

- Cellini, Benvenuto

- Cervantes, Miguel de

- Charles V, Emperor

- China and Europe, 1550-1800

- Christian-Muslim Exchange

- Christine de Pizan

- Church Fathers in Renaissance and Reformation Thought, The

- Ciceronianism

- Cities and Urban Patriciates

- Civic Humanism

- Civic Ritual

- Classical Tradition, The

- Clifford, Anne

- Colet, John

- Colonna, Vittoria

- Columbus, Christopher

- Comenius, Jan Amos

- Commedia dell'arte

- Concepts of the Renaissance, c. 1780–c. 1920

- Confraternities

- Constantinople, Fall of

- Contarini, Gasparo, Cardinal

- Convent Culture

- Conversos and Crypto-Judaism

- Copernicus, Nicolaus

- Cornaro, Caterina

- Cosimo I de’ Medici

- Cosimo il Vecchio de' Medici

- Council of Trent

- Crime and Punishment

- Cromwell, Oliver

- Cruz, Juana de la, Mother

- Cruz, Juana Inés de la, Sor

- d'Aragona, Tullia

- Datini, Margherita

- Davies, Eleanor

- de Commynes, Philippe

- de Sales, Saint Francis

- de Valdés, Juan

- Death and Dying

- Decembrio, Pier Candido

- Dentière, Marie

- Des Roches, Madeleine and Catherine

- d’Este, Isabella

- di Toledo, Eleonora

- Dolce, Ludovico

- Donne, John

- Drama, English Renaissance

- Dürer, Albrecht

- du Bellay, Joachim

- Du Guillet, Pernette

- Dutch Overseas Empire

- Ebreo, Leone

- Edmund Campion

- Emperor, Maximilian I

- England, 1485-1642

- Environment and the Natural World

- Epic and Romance

- Europe and the Globe, 1350–1700

- European Tapestries

- Family and Childhood

- Fedele, Cassandra

- Federico Barocci

- Female Lay Piety

- Ferrara and the Este

- Ficino, Marsilio

- Filelfo, Francesco

- Fonte, Moderata

- Foscari, Francesco

- France in the 17th Century

- Francis Xavier, St

- Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros

- French Law and Justice

- French Renaissance Drama

- Fugger Family

- Galilei, Galileo

- Gallicanism

- Gambara, Veronica

- Garin, Eugenio

- General Church Councils, Pre-Trent

- Geneva (1400-1600)

- Genoa 1450–1700

- George Buchanan

- George of Trebizond

- Georges de La Tour

- Giambologna

- Ginés de Sepúlveda, Juan

- Giustiniani, Bernardo

- Góngora, Luis de

- Gournay, Marie de

- Greek Visitors

- Guarino da Verona

- Guicciardini, Francesco

- Guilds and Manufacturing

- Hamburg, 1350–1815

- Hanseatic League

- Herbert, George

- Hispanic Mysticism

- Historiography

- Hobbes, Thomas

- Holy Roman Empire 1300–1650

- Homes, Foundling

- Humanism, The Origins of

- Hundred Years War, The

- Hungary, The Kingdom of

- Hutchinson, Lucy

- Iconology and Iconography

- Ignatius of Loyola, Saint

- Inquisition, Roman

- Isaac Casaubon

- Isabel I, Queen of Castile

- Italian Wars, 1494–1559

- Ivan IV the Terrible, Tsar of Russia

- Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples

- Japan and Europe: the Christian Century, 1549-1650

- Jeanne d’Albret, queen of Navarre

- Jewish Women in Renaissance and Reformation Europe