- Find My Rep

You are here

Qualitative Methods for Health Research

- Judith Green - Exeter University, UK

- Nicki Thorogood - Independent Academic

- Description

- Author(s) / Editor(s)

Packed with practical advice and research quick tips, this book is the perfect companion to your health research project. It not only explains the theory of qualitative health research so you can interpret the studies of others, but also showcases how to approach, start, maintain, and disseminate your own research.

It will help you:

- Understand the role of the researcher

- Develop an effective research proposal

- Seek ethical approval

- Conduct interviews, observational studies, mixed methods, and web-based designs

- Use secondary and digital sources

- Code, manage, and analyse data

- Write up your results

Whether you are studying public health, sports medicine, occupational therapy, nursing, midwifery, or another health discipline, the authors will be your surrogate supervisors and guide you through evaluating or undertaking any type of health research.

Supplements

This book is the clear and extensive introduction to qualitative health research. It is useful for all under and post graduate students, and even for PhDs with quantitative background.

A thoughtful, thorough and readable account of the history and current practice of qualitative research in health.

An enormously helpful resource for anyone interested in interpreting and conducting qualitative health research. In addition to describing complex social theory in an easily digestible style, it also provides a practical ‘how to’ guide for all the stages of qualitative data collection, analysis and dissemination. Filled with useful examples, it brings qualitative health research to life in a way that is both engaging and highly accessible. It is a must read for students and experienced scholars alike!

This new edition of Green and Thorogood’s excellent textbook should be required reading for health professionals considering undertaking qualitative research. Along with a practical introduction to the theory and methods of qualitative research, this revised edition expands on the importance of theory for qualitative research, the use of secondary sources and digital methods in data collection and the integration of methods, disciplines and designs within research. It continues to be a core text for any qualitative methods training for students in health and related disciplines.

Very good basic introduction, focus on ethnography and observation as essential qual. research designs/methods. Great book also for nursing science students.

This is an great resource for students undertaking qualitative methods for the first time. Additionally, it provides a great go-to for those further along in their use of these methods.

An informative introduction to qualitative research with practical advice and real-world examples.

An excellent resource for graduate and post graduate students in health research.

Added to my reading list for three modules-like the clear writing style, and 'how to' guides-useful for both undergraduate and post graduate students

I enjoyed reading this. Its an excellent practical book that helped organise and conduct qualitative research, safe in the knowledge that the project would be robust and credible. It also serves a s a useful reference for supervision.

Preview this book

Judith green.

Judith Green has degrees in anthropology and sociology, and a PhD in the sociology of heath. She has taught research methods to a wide range of students over the last 30 years, including undergraduate, postgraduate and doctoral students and health professionals from nursing, medicine, public health and sociology. She is currently Professor of Sociology of Health at King’s College London, and has held posts at the London School of Hygiene and Medicine and London South Bank University. Judith has broad substantive interests in the sociology of health and health services, and has researched and published on primary... More About Author

Nicki Thorogood

Nicki Thorogood’s first degree was in sociology and social anthropology, and she has a PhD in the sociology of health from the University of London. She has over 30 years experience of teaching undergraduate and postgraduate students. Before coming to LSHTM (London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine) in 1999 she held posts at Middlesex University and at Guy’s King’s and Thomas’s School of Medicine and Dentistry (GKT). Her research interests are primarily in qualitative research into aspects of ‘identity’, e.g. ethnicity, gender, disability and sexuality and in the sociology of the body. She is also interested in the intersection of... More About Author

Purchasing options

Please select a format:

Order from:

- Buy from SAGE

Related Products

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

The SAGE handbook of qualitative methods in health research [electronic resource]

Available online.

- Sage Research Methods

More options

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary.

- Introduction PART ONE: CONTRIBUTIONS OF QUALITATIVE RESEARCH There's More to Dying Than Death: Qualitative Research on the End-of-Life - Stefan Timmermans Healer-Patient Interaction: New Mediations in Clinical Relationships - Arthur W. Frank, Michael K. Corman, Jessica A. Gish and Paul Lawton Qualitative Contributions to the Study of Health Professions and Their Work - Johanne Collin Why Use Qualitative Methods to Study Health-Care Organizations? Insights from Multilevel Case Studies - Carol A. Caronna How Country Matters: Studying Health Policy in a Comparative Perspective - Sirpa Wrede Exploring Social Inequalities in Health: The Importance of Thinking Qualitatively - Gareth Williams and Eva Elliott PART TWO: THEORY Theory Matters in Qualitative Health Research - Mita Giacomini Ethnographic Approaches to Health and Development Research: The Contributions of Anthropology - Rebecca Prentice What Is Grounded Theory and Where Does It Come from? - Dorothy Pawluch and Elena Neiterman Qualitative Methods from Psychology - Helen Malson Conversation Analysis and Ethnomethodology: The Centrality of Interaction - Timothy Halkowski and Virginia Teas Gill Phenomenology - Carol L. McWilliam Studying Organizations: The Revival of Institutionalism - Karen Staniland History and Social Change in Health and Medicine - Claire Hooker PART THREE: COLLECTING AND ANALYZING DATA Qualitative Research Review and Synthesis - Jennie Popay and Sara Mallinson Qualitative Interviewing Techniques and Styles - Susan E. Kelly Focus Groups - Rosaline S. Barbour Fieldwork and Participant Observation - Davina Allen Video-Based Conversation Analysis - Ruth Parry Practising Discourse Analysis in Healthcare Settings - Srikant Sarangi Documents in Health Research - Lindsay Prior Participatory Action Research: Theoretical Perspectives on the Challenges of Researching Action - Louise Potvin, Sherri L. Bisset and Leah Walz Qualitative Research in Programme Evaluation - Isobel MacPherson and Linda McKie Auto-Ethnography: Making Sense of Personal Illness Journeys - Elizabeth Ettore Institutional Ethnography - Marie L. Campbell Visual Methods for Collecting and Analysing Data - Susan E. Bell Keyword Analysis: A New Tool for Qualitative Research - Clive Seale and Jonathan Charteris-Black PART FOUR: ISSUES IN QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH Recognizing Quality in Qualitative Research - Kath M. Melia Mixed Methods Involving Qualitative Research - Alicia O'Cathain A Practical Guide to Research Ethics - Laura Stark and Adam Hedgecoe Using Qualitative Research Methods to Inform Health Policy: The Case of Public Deliberation - Julia Abelson Cross National Qualitative Health Research - Carine Vassy and Richard Keller PART FIVE: APPLYING QUALITATIVE METHODS Researching Reproduction Qualitatively: Intersections of Personal and Political - Kereen Reiger and Pranee Liamputtong Understanding the Shaping, Incorporation and Co-Ordination of Health Technologies through Qualitative Research - Tiago Moreira and Tim Rapley Transgressive Pleasures: Undertaking Qualitative Research in the Radsex Domain - Dave Holmes, Patrick O'Byrne and Denise Gastaldo The Challenges and Opportunities of Qualitative Health Research with Children - Ilina Singh and Sinead Keenan The Dilemmas of Advocacy: The Paradox of Giving in Disability Research - Ruth Pinder Qualitative Approaches for Studying Environmental Health - Phil Brown.

- (source: Nielsen Book Data)

Bibliographic information

Browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals

- Janice M. Morse - University of Utah, USA

- Peggy Anne Field - University of Alberta - Edmonton, Canada

- Description

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Select a Purchasing Option

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Qualitative methods for health research

Choice Reviews Online

Related Papers

Catherine Pope

Online Journal of …

Kalaiselvan Ganapathy

Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice

Mary Boulton

It is increasingly argued that qualitative approaches have an important role in health care research. A wide range of methods are used to collect qualitative data, including in-depth interviews, focus groups and observational methods such as participant observation. The reliability and validity of qualitative studies can be addressed by a variety of techniques. Although there is less consensus about appropriate methods of analysing qualitative data, such analyses tend to be grounded in the data, and involve iterative procedures and the development and refinement of typologies, analogies and other forms of concept to make sense of data.

Douglas Ezzy

Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health

Objective: To provide an overview of qualitative methodologies for health researchers in order to inform better research practices.Approach: Different possible goals in health research are outlined: quantifying relationships between variables, identifying associations, exploring experience, understanding process, distinguishing representations, comprehending social practices and achieving change. Three important issues in understanding qualitative approaches to research are discussed: the partiality of our view of the world, deductive and inductive approaches to research, and the role of the researcher in the research process. The methodologies of phenomenology, grounded theory, discourse analysis, ethnography, ethnomethodology and action research are illustrated.Conclusion: In order to undertake high-quality qualitative research, it is important for researchers to consider their analytic focus and methodological position.

A hand search of the original papers in seven medical journals over 5 years was conducted in order to identify those reporting qualitative research. A total of 210 papers were initially identified, of which 70 used qualitative methods of both data collection and analysis. These papers were evaluated by the researchers using a checklist which specified the criteria of good practice. Overall, 2% of the original papers published in the journals reported qualitative studies. Papers were more frequently positively assessed in terms of having clear aims, reporting research for which a qualitative approach was appropriate and describing their methods of data collection. Papers were less frequently positively assessed in relation to issued of data analysis such as validity, reliability and providing representative supporting evidence. It is concluded that the full potential of qualitative research has yet to be realized in the field of health care.

Kieron Ivan Gutierrez

This paper focuses on the question of sampling (or selection of cases) in qualitative research. Although the literature includes some very useful discussions of qualitative sampling strategies, the question of sampling often seems to receive less attention in methodological discussion than questions of how data is collected or is analysed. Decisions about sampling are likely to be important in many qualitative studies (although it may not be an issue in some research). There are varying accounts of the principles applicable to sampling or case selection. Those who espouse 'theoretical sampling', based on a 'grounded theory' approach, are in some ways opposed to those who promote forms of 'purposive sampling' suitable for research informed by an existing body of social theory. Diversity also results from the many different methods for drawing purposive samples which are applicable to qualitative research. We explore the value of a framework suggested by Miles and Huberman [Miles, M., Huberman,, A., 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis, Sage, London.], to evaluate the sampling strategies employed in three examples of research by the authors. Our examples comprise three studies which respectively involve selection of: 'healing places'; rural places which incorporated national anti-malarial policies; young male interviewees, identified as either chronically ill or disabled. The examples are used to show how in these three studies the (sometimes conflicting) requirements of the different criteria were resolved, as well as the potential and constraints placed on the research by the selection decisions which were made. We also consider how far the criteria Miles and Huberman suggest seem helpful for planning 'sample' selection in qualitative research. Abstract PURPOSE We wanted to review and synthesize published criteria for good qualitative research and develop a cogent set of evaluative criteria. METHODS We identified published journal articles discussing criteria for rigorous research using standard search strategies then examined reference sections of relevant journal articles to identify books and book chapters on this topic. A cross-publication content analysis allowed us to identify criteria and understand the beliefs that shape them. RESULTS Seven criteria for good qualitative research emerged: (1) carrying out ethical research; (2) importance of the research; (3) clarity and coherence of the research report; (4) use of appropriate and rigorous methods; (5) importance of reflexivity or attending to researcher bias; (6) importance of establishing validity or credibility; and (7) importance of verification or reliability. General agreement was observed across publications on the first 4 quality dimensions. On the last 3, important divergent perspectives were observed in how these criteria should be applied to qualitative research, with differences based on the paradigm embraced by the authors. CONCLUSION Qualitative research is not a unified field. Most manuscript and grant reviewers are not qualitative experts and are likely to embrace a generic set of criteria rather than those relevant to the particular qualitative approach proposed or reported. Reviewers and researchers need to be aware of this tendency and educate health care researchers about the criteria appropriate for evaluating qualitative research from within the theoretical and methodological framework from which it emerges.

Journal of General Internal Medicine

Sayeeda Rahman

Ciência & Saúde Coletiva

Vera L P Alves

Qualitative Health research procedures that are not always applied, mainly in the analysis phase. Our objective is to present a systematized technique of step-by-step procedures for qualitative content analysis in the health field: Clinical-Qualitative Content Analysis. Our proposal consider that the qualitative research applied to the field of health, can acquire a perspective analogous to clinical practice and aims to interpret meanings expressed in reports through individual interviews or statements. This analysis takes part of the Clinical-Qualitative Method. The literature review was realized through: a book chapter, eight original articles and three methodological articles. The Clinical-qualitative Content Analysis technique comprises seven steps: 1) Editing material for analysis; 2) Floating reading; 3) Construction of the units of analysis; 4) Construction of codes of meaning; 5) General refining of the codes and the Construction of categories; 6) Discussion; 7) Validity. Th...

RELATED PAPERS

Annals of Romanian Society of Cell Biology

YASIR H A I D E R AL-MAWLAH

Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys.

ABDESSELAM BELAARAJ

Schweizerische Ärztezeitung

Michel Romanens

Acta Neurologica Belgica

Kenou van Rijckevorsel

International Journal of Business and Development Studies

International Journal of Workplace Health Management

Johnny Dyreborg

Fisioterapia e Pesquisa

Guilherme Rodrigues

Universitas Humanística

Amurabi Oliveira

Jurnal Analis Medika Biosains (JAMBS)

erlin tatontos

Procedia Materials Science

KOLLI RAMUJEE

Nonlinearity

Changjiang Zhu

Iranian Journal of Chemistry & Chemical Engineering-international English Edition

Mohammad Reza Yaftian

Horacio Chiavazza

The journal of bone and joint surgery

Engineering Geology

Javier Martinez

Physica D: Nonlinear Phenomena

Thanos Manos

Journal of Fungi

Ayesha S Nair

Siti Munawaroh

hjhjgf frgtg

hjhfggf hjgfdf

Devoir surveillé N°2, Sciences mathématiques, Semestre 2, 2BAC PC, SVT, SM A et B, M. Karam Ouharou

Karam Ouharou

Maria Tsampra

Nucleation and Atmospheric Aerosols

Oria Farisi

Metafory polityki vol. 4

Michał Szczegielniak

SSRN Electronic Journal

Martin Cave

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Find My Rep

You are here

Sage online ordering services will be unavailable due to system maintenance on April 13th between 2:00 am and 8:00 am UK time If you need assistance, please contact Sage at [email protected] . Thank you for your patience and we apologise for the inconvenience.

Qualitative Health Research

Preview this book.

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting / Indexing

- Submission Guidelines

Qualitative Health Research provides an international, interdisciplinary forum to enhance health and health care and further the development and understanding of qualitative health research. The journal is an invaluable resource for researchers and academics, administrators and others in the health and social service professions, and graduates, who seek examples of studies in which the authors used qualitative methodologies. Each issue of Qualitative Health Research provides readers with a wealth of information on conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and ethical issues pertaining to qualitative inquiry. A Variety of Perspectives We encourage submissions across all health-related areas and disciplines. Qualitative Health Research understands health in its broadest sense and values contributions from various traditions of qualitative inquiry. As a journal of SAGE Publishing, Qualitative Health Research aspires to disseminate high-quality research and engaged scholarship globally, and we are committed to diversity and inclusion in publishing. We encourage submissions from a diverse range of authors from across all countries and backgrounds. There are no fees payable to submit or publish in Qualitative Health Research .

Original, Timely, and Insightful Scholarship Qualitative Health Research aspires to publish articles addressing significant and contemporary health-related issues. Only manuscripts of sufficient originality and quality that align with the aims and scope of Qualitative Health Research will be reviewed. As part of the submission process authors are required to warrant that they are submitting original work, that they have the rights in the work, that they have obtained, and that can supply all necessary permissions for the reproduction of any copyright works not owned by them, and that they are submitting the work for first publication in the Journal and that it is not being considered for publication elsewhere and has not already been published elsewhere. Please note that Qualitative Health Research does not accept submissions of papers that have been published elsewhere. Sage requires authors to identify preprints upon submission (see https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/preprintsfaq ). This Journal is a member of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) .

This Journal recommends that authors follow the Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals formulated by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE).

Qualitative Health Research is an international, interdisciplinary, refereed journal for the enhancement of health care and to further the development and understanding of qualitative research methods in health care settings. We welcome manuscripts in the following areas: the description and analysis of the illness experience, health and health-seeking behaviors, the experiences of caregivers, the sociocultural organization of health care, health care policy, and related topics. We also seek critical reviews and commentaries addressing conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and ethical issues pertaining to qualitative enquiry.

- Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts (ASSIA)

- CAB Abstracts (Index Veterinarius, Veterinary Bulletin)

- CABI: Abstracts on Hygiene and Communicable Diseases

- CABI: CAB Abstracts

- CABI: Global Health

- CABI: Nutrition Abstracts and Reviews Series A

- CABI: Tropical Diseases Bulletin

- Clarivate Analytics: Current Contents - Physical, Chemical & Earth Sciences

- Combined Health Information Database (CHID)

- Corporate ResourceNET - Ebsco

- Current Citations Express

- EBSCO: Vocational & Career Collection

- EMBASE/Excerpta Medica

- Family & Society Studies Worldwide (NISC)

- Health Business FullTEXT

- Health Service Abstracts

- Health Source Plus

- MasterFILE - Ebsco

- ProQuest: Applied Social Science Index & Abstracts (ASSIA)

- ProQuest: CSA Sociological Abstracts

- Psychological Abstracts

- Rural Development Abstracts

- SRM Database of Social Research Methodology

- Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science)

- Social Services Abstracts

- Standard Periodical Directory (SPD)

- TOPICsearch - Ebsco

Manuscript submission guidelines:

Qualitative Health Research (QHR) has specific guidelines! While Sage Publishing has general guidelines , all manuscripts submitted to QHR must follow our specific guidelines (found below). Once you have reviewed these guidelines, please visit QHR ’s submission site to upload your manuscript. Please note that manuscripts not conforming to these guidelines will be returned and/or encounter delays in peer review. Remember you can log in to the submission site at any time to check on the progress of your manuscript throughout the peer review process.

1. Deciding whether to submit a manuscript to QHR

1.1 Aims & scope

1.2 Article types

2. Review criteria

2.1 Original research studies

2.2 Pearls, Piths, and Provocations

2.3 Common reasons for rejection

3. Preparing your manuscript

3.1 Title page

3.2 Abstract

3.3 Manuscript

3.4 Tables, Figures, Artwork, and other graphics

3.5 Supplemental material

4. Submitting your manuscript

5. Editorial Policies

5.1 Peer review policy

5.2 Authorship

5.3 Acknowledgments

5.4 Funding

5.5 Declaration of conflicting interests

5.6 Research ethics and participant consent

6. Publishing Policies

6.1 Publication ethics

6.2 Contribtor's publishing agreement

6.3 Open access and author archiving

1. Deciding whether to submit a manuscript to QHR

QHR provides an international, interdisciplinary forum to enhance health and health care and further the development and understanding of qualitative health research. The journal is an invaluable resource for researchers and academics, administrators and others in the health and social service professions, and graduates, who seek examples of studies in which the authors used qualitative methodologies. Each issue of QHR provides readers with a wealth of information on conceptual, theoretical, methodological, and ethical issues pertaining to qualitative inquiry.

Rather than send query letters to the Editor regarding article fit, QHR asks authors to make their own decision regarding the suitability of their manuscript for QHR by asking: Does your proposed submission make a meaningful and strong contribution to qualitative health research literature? Is it useful to readers and/or practitioners?

The following manuscript types are considered for publication.

- Original Research Studies : These are fully developed qualitative research studies. This may include mixed method studies in which the major focus/portion of the study is qualitative research. Please read Maintaining the Integrity of Qualitatively Driven Mixed Methods: Avoiding the “ This Work is Part of a Larger Study” Syndrome .

- Pearls, Piths, and Provocations : These manuscripts should foster discussion and debate about significant issues, enhance communication of methodological advances, promote and discuss issues related to the teaching of qualitative approaches in health contexts, and/or encourage the discussion of new and/or provocative ideas. They should also make clear what the manuscript adds to the existing body of knowledge in the area.

- Editorials : These are generally invited articles written by editors/editorial board members associated with QHR.

Please note, QHR does NOT publish pilot studies. We do not normally publish literature reviews unless they focus on qualitative research studies elaborating methodological issues and developments. Review articles should be submitted to the Pearls, Piths, and Provocations section. They are reviewed according to criteria in 2.2.

Back to top

2. Review criteria

2.1 Original research

Reviewers are asked to consider the following areas and questions when making recommendations about research manuscripts:

- Importance of submission : Does the manuscript make a significant contribution to qualitative health research literature? Is it original? Relevant? In depth? Insightful? Is it useful to the reader and/or practitioner?

- Methodological considerations : Is the overall study design clearly explained including why this design was an appropriate one? Are the methodology/methods/approaches used in keeping with that design? Are they appropriate given the research question and/or aims? Are they logically articulated? Clarity in design and presentation? Data adequacy and appropriateness? Evidence of rigor?

- Ethical Concerns : Are relevant ethical concerns discussed and acknowledged? Is enough detail given to enable the reader to understand how ethical issues were navigated? Has formal IRB approval (when needed) and consent from participants been obtained?

- Data analysis, findings, discussion : Does the analysis of data reflect depth and coherence? In-depth descriptive but also interpretive dimensions? Creative and insightful analysis? Are results linked to existing literature and theory, as appropriate? Is the contribution of the research clear including its relevance to health disciplines and their practice?

- Manuscript style and format : Is the manuscript organized in a clear and concise manner? Has sufficient attention been paid to word choice, spelling, grammar, and so forth? Did the author adhere to APA guidelines? Do diagrams/illustrations comply with guidelines? Is the overall manuscript aligned with QHR guidelines in relation to formatting?

- Scope: Does the article fit with QHR ’s publication mandate? Has the author cited the major work in the area, including those published in QHR ?

The purpose of papers in this section is to raise and discuss issues pertinent to the development and advancement of qualitative research in health-related arenas. As the name Pearls, Piths, and Provocations suggests, we are looking for manuscripts that make a significant contribution to areas of dialogue, development, experience sharing and debate relevant to the scope of QHR in this section of the journal. Reviewers are asked to consider the following questions when making recommendations about articles in the Pearls, Piths, and Provocations section.

- Significance : Does the paper highlight issues that have the potential to advance, develop, and/or challenge thinking in qualitative health related research?

- Clarity : Are the arguments clearly presented and well supported?

- Rigor : Is there the explicit use of/interaction with methodology and/or theory and/or empirical studies (depending on the focus of the paper) that grounds the work and is coherently carried throughout the arguments and/or analysis in the manuscript? Put another way, is there evidence of a rigorously constructed argument?

- Engagement : Does the paper have the potential to engage the reader to ‘think differently’ by raising questions, suggesting innovative directions for qualitative health research, and/or stimulating critical reflection? Are the implications of the paper for the practice of either qualitative research and/or health clear?

- Quality of the writing : Is the main argument of the paper clearly articulated and presented with few grammatical or typographical issues? Are terms and concepts key to the scholarship communicated clearly and in sufficient detail?

QHR most commonly turns away manuscripts that fall outside the journal’s scope, do not make a novel contribution to the literature, lack substantive and/or interpretative depth, require extensive revisions, and/or do not adequately address ethical issues that are fundamental to qualitative inquiry. Submissions of the supplementary component of mixed methods studies often are rejected as the findings are difficult to interpret without the findings of the primary study. For additional information on this policy, please read Maintaining the Integrity of Qualitatively Driven Mixed Methods: Avoiding the “ This Work is Part of a Larger Study” Syndrome .

3. Preparing your manuscript for submission

We strongly encourage all authors to review previously published articles in QHR for style prior to submission.

QHR journal practices include double anonymization. All identifying information MUST be removed completely from the Abstract, Manuscript, Acknowledgements, Tables, and Figure files prior to submission. ONLY the Title Page and Cover Letter may contain identifying information. See Sage’s general submission guidelines for additional guidance on making an anonymous submission.

Preferred formats for the text and tables of your manuscript are Word DOC or PDF. The text must be double-spaced throughout with standard 1-inch margins (APA formatting). Text should be standard font (i.e., Times New Roman) 12-point.

3.1 Title page

- The title page should be uploaded as a separate document containing the following information: Author names; Affiliations; Author contact information; Contribution list; Acknowledgements; Ethical statement; Funding Statement; Conflict of Interest Statements; and, Grant Number. Please know that the Title Page is NOT included in the materials sent out for Peer Review.

- Ethical statement: An ethical statement must include the following: the full name of the ethical board that approved your study; the approval number given by the ethical board; and, confirmation that all your participants gave informed consent. Authors are also required to state in the methods section whether participants provided informed consent, whether the consent was written or verbal, and how it was obtained and by whom. For example: “Our study was approved by The Mercy Health Research Ethics Committee (approval no. XYZ123). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study.” If your study did not need ethical approval (often manuscripts in the Pearls, Piths, and Provocations may not), we still need a statement that states that your study did not need approval and an explanation as to why. For example: “Ethical Statement: Our study did not require an ethical board approval because it did not directly involve humans or animals.”

3.2 Abstract and Keywords

- The Abstract should be unstructured, written in narrative form. Maximum of 250 words. This should be on its own page, appearing as the first page of the Main Manuscript file.

- The keywords should be included beneath the abstract on the Main Manuscript file.

- Length: 8,000 words or less excluding the abstract, list of references, and acknowledgements. Please note that text from Tables and Figures is included in the word count limits. On-line supplementary materials are not included in the word limit.

- Structure: While many authors will choose to use headings of Background, Methods, Results, and Discussion to organize their manuscript, it is up to authors to choose the most appropriate terms and structure for their submission. It is the expectation that manuscripts contain detailed reflections on methodological considerations.

- Ethics: In studies where data collection or other methods present ethical challenges, the authors should explicate how such issues were navigated including how consent was gained and by whom. An anonymized version of the ethical statement should be included in the manuscript (in addition to appearing on the title page).

- Participant identification: Generally, demographics should be described in narrative form or otherwise reported as a group. Quotations may be linked to particular participants and/or demographic features provided measures are taken to ensure anonymity of participants (e.g., use of pseudonyms).

- Use of checklists: Authors should not include qualitative research checklists, such as COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research). Generally, authors should use a narrative approach to describe the processes used to enhance the rigor of their study. For additional information on this policy, please read Why the Qualitative Health Research (QHR) Review Process Does Not Use Checklists

- References: APA format. While there is no limit to the number of references, authors are recommended to use pertinent references only, including literature previously published in QHR . References should be on a separate page. QHR adheres to the APA 7 reference style. View the APA guidelines to ensure your manuscript conforms to this reference style. Please ensure you check carefully that both your in-text references and list of references are in the correct format.

- Authors are required to disclose the use of generative Artificial Intelligence (such as ChatGPT) and other technologies (such as NVivo, ATLAS. Ti, Quirkos, etc.), whether used to conceive ideas, develop study design, generate data, assist in analysis, present study findings, or other activities formative of qualitative research. We suggest authors provide both a description of the technology, when it was accessed, and how it was used (see https://uk.sagepub.com/en-gb/eur/chatgpt-and-generative-ai ).

- Manuscripts that receive favorable reviews will not be accepted until any formatting and copy-editing required has been done.

- Tables, Figures, Artwork, and other graphics should be submitted as separate files rather than incorporated into the main manuscript file. Within the manuscript, indicate where these items should appear (i.e. INSERT TABLE 1 HERE).

- TIFF, JPED, or common picture formats accepted. The preferred format for graphs and line art is EPS.

- Resolution: Rasterized based files (i.e. with .tiff or .jpeg extension) require a resolution of at least 300 dpi (dots per inch). Line art should be supplied with a minimum resolution of 800 dpi.

- Dimension: Check that the artworks supplied match or exceed the dimensions of the journal. Images cannot be scaled up after origination.

- Figures supplied in color will appear in color online regardless of whether or not these illustrations are reproduced in color in the printed version. For specifically requested color reproduction in print, you will receive information regarding the costs from Sage after receipt of your accepted article.

- Core elements of the manuscript should not be included as supplementary material.

- QHR is able to host additional materials online (e.g., datasets, podcasts, videos, images etc.) alongside the full-text of the article. For more information please refer to Sage’s general guidelines on submitting supplemental files .

4. Submitting your manuscript

QHR is hosted on Sage Track, a web based online submission and peer review system powered by ScholarOne™ Manuscripts. Visit https://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/QHR to login and submit your article online.

IMPORTANT: Please check whether you already have an account in the system before trying to create a new one. If you have reviewed or authored for the Journal in the past year it is likely that you will have had an account created. For further guidance on submitting your manuscript online please visit ScholarOne Online Help .

5. Editorial policies

QHR adheres to a rigorous double-anonymized reviewing policy in which the identities of both the reviewer and author are always concealed from both parties.

Sage does not permit the use of author-suggested (recommended) reviewers at any stage of the submission process, be that through the web-based submission system or other communication. Reviewers should be experts in their fields and should be able to provide an objective assessment of the manuscript. Our policy is that reviewers should not be assigned to a manuscript if:

• The reviewer is based at the same institution as any of the co-authors

• The reviewer is based at the funding body of the manuscript

• The author has recommended the reviewer

• The reviewer has provided a personal (e.g. Gmail/Yahoo/Hotmail) email account and an institutional email account cannot be found after performing a basic Google search (name, department and institution).

Qualitative Health Research is committed to delivering high quality, fast peer-review for your manuscript, and as such has partnered with Web of Science. Web of Science is a third-party service that seeks to track, verify and give credit for peer review. Reviewers for Qualitative Health Research can opt in to Web of Science in order to claim their reviews or have them automatically verified and added to their reviewer profile. Reviewers claiming credit for their review will be associated with the relevant journal, but the article name, reviewer’s decision, and the content of their review is not published on the site. For more information visit the Web of Science website.

The Editor or members of the Editorial Team or Board may occasionally submit their own manuscripts for possible publication in the Journal. In these cases, the peer review process will be managed by alternative members of the Editorial Team or Board and the submitting Editor Team/Board member will have no involvement in the decision-making process.

Manuscripts should only be submitted for consideration once consent is given by all contributing authors. Those submitting manuscripts should carefully check that all those whose work contributed to the manuscript are acknowledged as contributing authors. The list of authors should include all those who can legitimately claim authorship. This is all those who meet all of the following criteria:

(i) Made a substantial contribution to the design of the work or acquisition, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of data, (ii) Drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content, (iii) Approved the version to be published, (iv) Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content.

Acquisition of funding, collection of data, or general supervision of the research group alone does not constitute authorship, although all contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship should be listed in the Acknowledgments section. Please refer to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) authorship guidelines for more information on authorship.

Authors are required to disclose the use of generative Artificial Intelligence (such as ChatGPT) and other technologies (such as NVivo, ATLAS. Ti, Quirkos, etc.), whether used to conceive ideas, develop study design, generate data, assist in analysis, present study findings, or other activities formative of qualitative research. We suggest authors provide both a description of the technology, when it was accessed, and how it was used. This needs to be clearly identified within the text and acknowledged within your Acknowledgements section. Please note that AI bots such as ChatGPT should not be listed as an author. For more details on this policy, please visit ChatGPT and Generative AI .

5.3 Acknowledgements

All contributors who do not meet the criteria for authorship should be listed in an Acknowledgements section. Examples of those who might be acknowledged include a person who provided purely technical help, or a department chair who provided only general support.

Please supply any personal acknowledgements separately to the main text to facilitate anonymous peer review.

Per ICMJE recommendations , it is best practice to obtain consent from non-author contributors who you are acknowledging in your manuscript.

1.3.1 Writing assistance

Individuals who provided writing assistance, e.g., from a specialist communications company, do not qualify as authors and so should be included in the Acknowledgements section. Authors must disclose any writing assistance – including the individual’s name, company and level of input – and identify the entity that paid for this assistance. It is not necessary to disclose use of language polishing services.

Qualitative Health Research requires all authors to acknowledge their funding in a consistent fashion under a separate heading. Please visit the Funding Acknowledgements page on the Sage Journal Author Gateway to confirm the format of the acknowledgment text in the event of funding, or state that: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

It is the policy of Qualitative Health Research to require a declaration of conflicting interests from all authors enabling a statement to be carried within the paginated pages of all published articles.

Please ensure that a ‘Declaration of Conflicting Interests’ statement is included at the end of your manuscript, after any acknowledgements and prior to the references. If no conflict exists, please state that ‘The Author(s) declare(s) that there is no conflict of interest’. For guidance on conflict of interest statements, please see the ICMJE recommendations here .

Research involving participants must be conducted according to the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki

Submitted manuscripts should conform to the ICMJE Recommendations for the Conduct, Reporting, Editing, and Publication of Scholarly Work in Medical Journals :

All manuscripts must state that the relevant Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board provided (or waived) approval. Please ensure that you blind the name and institution of the review committee until such time as your article has been accepted. The Editor will request authors to replace the name and add the approval number once the article review has been completed. Please note that in itself, simply stating that Ethics Committee or Institutional Review was obtained is not sufficient. Authors are also required to state in the methods section whether participants provided informed consent, whether the consent was written or verbal, and how it was obtained and by whom.

Please do not submit the participant’s informed consent documents with your article, as this in itself breaches the participant’s confidentiality. The Journal requests that you confirm to us, in writing, that you have obtained informed consent recognizing the documentation of consent itself should be held by the authors/investigators themselves (for example, in a participant’s hospital record or an author’s institution’s archives).

Please also refer to the ICMJE Recommendations for the Protection of Research Participants .

6. Publishing Policies

Sage is committed to upholding the integrity of the academic record. We encourage authors to refer to the Committee on Publication Ethics’ International Standards for Authors and view the Publication Ethics page on the Sage Author Gateway .

6.1.1 Plagiarism

Qualitative Health Research and Sage take issues of copyright infringement, plagiarism or other breaches of best practice in publication very seriously. The Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) defines plagiarism as: “When somebody presents the work of others (data, words or theories) as if they were his/her own and without proper acknowledgment.” We seek to protect the rights of our authors and we always investigate claims of plagiarism or misuse of published articles. Equally, we seek to protect the reputation of the journal against malpractice. Submitted articles may be checked with duplication-checking software. Where an article, for example, is found to have plagiarised other work or included third-party copyright material without permission or with insufficient acknowledgement, or where the authorship of the article is contested, we reserve the right to take action including, but not limited to: publishing an erratum or corrigendum (correction); retracting the article; taking up the matter with the head of department or dean of the author's institution and/or relevant academic bodies or societies; or taking appropriate legal action.

6.1.2 Prior publication

If material has been previously published it is not generally acceptable for publication in a Sage journal. However, there are certain circumstances where previously published material can be considered for publication. Please refer to the guidance on the Sage Author Gateway or if in doubt, contact the Editor at the address given below.

6.2 Contributor's publishing agreement

Before publication, Sage requires the author as the rights holder to sign a Journal Contributor’s Publishing Agreement. Sage’s Journal Contributor’s Publishing Agreement is an exclusive licence agreement which means that the author retains copyright of the work but grants Sage the sole and exclusive right and licence to publish for the full legal term of copyright. Exceptions may exist where an assignment of copyright is required or preferred by a proprietor other than Sage. In this case copyright in the work will be assigned from the author to the society. For more information please visit the Sage Author Gateway .

Qualitative Health Research offers optional open access publishing via the Sage Choice programme and Open Access agreements, where authors can publish open access either discounted or free of charge depending on the agreement with Sage. Find out if your institution is participating by visiting Open Access Agreements at Sage . For more information on Open Access publishing options at Sage please visit Sage Open Access . For information on funding body compliance, and depositing your article in repositories, please visit Sage’s Author Archiving and Re-Use Guidelines and Publishing Policies .

- Read Online

- Sample Issues

- Current Issue

- Email Alert

- Permissions

- Foreign rights

- Reprints and sponsorship

- Advertising

Individual Subscription, E-access

Individual Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Backfile Purchase, E-access (Content through 1998)

Institutional Subscription, E-access

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, E-access Plus Backfile (All Online Content)

Institutional Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, Combined (Print & E-access)

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, Combined Plus Backfile (Current Volume Print & All Online Content)

Individual, Single Print Issue

Institutional, Single Print Issue

Subscription Information

To purchase a non-standard subscription or a back issue, please contact SAGE Customer Services for availability.

[email protected] +44 (0) 20 7324 8701

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Patient Cent Res Rev

- v.11(1); Spring 2024

- PMC11000705

Research Frameworks: Critical Components for Reporting Qualitative Health Care Research

Qualitative health care research can provide insights into health care practices that quantitative studies cannot. However, the potential of qualitative research to improve health care is undermined by reporting that does not explain or justify the research questions and design. The vital role of research frameworks for designing and conducting quality research is widely accepted, but despite many articles and books on the topic, confusion persists about what constitutes an adequate underpinning framework, what to call it, and how to use one. This editorial clarifies some of the terminology and reinforces why research frameworks are essential for good-quality reporting of all research, especially qualitative research.

Qualitative research provides valuable insights into health care interactions and decision-making processes – for example, why and how a clinician may ignore prevailing evidence and continue making clinical decisions the way they always have. 1 The perception of qualitative health care research has improved since a 2016 article by Greenhalgh et al. highlighted the higher contributions and citation rates of qualitative research than those of contemporaneous quantitative research. 2 The Greenhalgh et al. article was subsequently supported by an open letter from 76 senior academics spanning 11 countries to the editors of the British Medical Journal . 3 Despite greater recognition and acceptance, qualitative research continues to have an “uneasy relationship with theory,” 4 which contributes to poor reporting.

As an editor for the Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews , as well as Human Resources for Health , I have seen several exemplary qualitative articles with clear and coherent reporting. On the other hand, I have often been concerned by a lack of rigorous reporting, which may reflect and reinforce the outdated perception of qualitative research as the “soft option.” 5 Qualitative research is more than conducting a few semi-structured interviews, transcribing the audio recordings verbatim, coding the transcripts, and developing and reporting themes, including a few quotes. Qualitative research that benefits health care is time-consuming and labor-intensive, requires robust design, and is rooted in theory, along with comprehensive reporting. 6

What Is “Theory”?

So fundamental is theory to qualitative research that I initially toyed with titling this editorial, “ Theory: the missing link in qualitative health care research articles ,” before deeming that focus too broad. As far back as 1967, Merton 6 warned that “the word theory threatens to become meaningless.” While it cannot be overstated that “atheoretical” studies lack the underlying logic that justifies researchers’ design choices, the word theory is so overused that it is difficult to understand what constitutes an adequate theoretical foundation and what to call it.

Theory, as used in the term theoretical foundation , refers to the existing body of knowledge. 7 , 8 The existing body of knowledge consists of more than formal theories , with their explanatory and predictive characteristics, so theory implies more than just theories . Box 1 9 – 12 defines the “building blocks of formal theories.” 9 Theorizing or theory-building starts with concepts at the most concrete, experiential level, becoming progressively more abstract until a higher-level theory is developed that explains the relationships between the building blocks. 9 Grand theories are broad, representing the most abstract level of theorizing. Middle-range and explanatory theories are progressively less abstract, more specific to particular phenomena or cases (middle-range) or variables (explanatory), and testable.

The Building Blocks of Formal Theories 9

The importance of research frameworks.

Researchers may draw on several elements to frame their research. Generally, a framework is regarded as “a set of ideas that you use when you are forming your decisions and judgements” 13 or “a system of rules, ideas, or beliefs that is used to plan or decide something.” 14 Research frameworks may consist of a single formal theory or part thereof, any combination of several theories or relevant constructs from different theories, models (as simplified representations of formal theories), concepts from the literature and researchers’ experiences.

Although Merriam 15 was of the view that every study has a framework, whether explicit or not, there are advantages to using an explicit framework. Research frameworks map “the territory being investigated,” 8 thus helping researchers to be explicit about what informed their research design, from developing research questions and choosing appropriate methods to data analysis and interpretation. Using a framework makes research findings more meaningful 12 and promotes generalizability by situating the study and interpreting data in more general terms than the study itself. 16

Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks

The variation in how the terms theoretical and conceptual frameworks are used may be confusing. Some researchers refer to only theoretical frameworks 17 , 18 or conceptual frameworks, 19 – 21 while others use the terms interchangeably. 7 Other researchers distinguish between the two. For example, Miles, Huberman & Saldana 8 see theoretical frameworks as based on formal theories and conceptual frameworks derived inductively from locally relevant concepts and variables, although they may include theoretical aspects. Conversely, some researchers believe that theoretical frameworks include formal theories and concepts. 18 Others argue that any differences between the two types of frameworks are semantic and, instead, emphasize using a research framework to provide coherence across the research questions, methods and interpretation of the results, irrespective of what that framework is called.

Like Ravitch and Riggan, 22 I regard conceptual frameworks (CFs) as the broader term. Including researchers’ perspectives and experiences in CFs provides valuable sources of originality. Novel perspectives guard against research repeating what has already been stated. 23 The term theoretical framework (TF) may be appropriate where formal published and identifiable theories or parts of such theories are used. 24 However, existing formal theories alone may not provide the current state of relevant concepts essential to understanding the motivation for and logic underlying a study. Some researchers may argue that relevant concepts may be covered in the literature review, but what is the point of literature reviews and prior findings unless authors connect them to the research questions and design? Indeed, Sutton & Straw 25 exclude literature reviews and lists of prior findings as an adequate foundation for a study, along with individual lists of variables or constructs (even when the constructs are defined), predictions or hypotheses, and diagrams that do not propose relationships. One or more of these aspects could be used in a research framework (eg, in a TF), and the literature review could (and should) focus on the theories or parts of theories (constructs), offer some critique of the theory and point out how they intend to use the theory. This would be more meaningful than merely describing the theory as the “background” to the study, without explicitly stating why and how it is being used. Similarly, a CF may include a discussion of the theories being used (basically, a TF) and a literature review of the current understanding of any relevant concepts that are not regarded as formal theory.

It may be helpful for authors to specify whether they are using a theoretical or a conceptual framework, but more importantly, authors should make explicit how they constructed and used their research framework. Some studies start with research frameworks of one type and end up with another type, 8 , 22 underscoring the need for authors to clarify the type of framework used and how it informed their research. Accepting the sheer complexity surrounding research frameworks and lamenting the difficulty of reducing the confusion around these terms, Box 2 26 – 31 and Box 3 offer examples highlighting the fundamental elements of theoretical and conceptual frameworks while acknowledging that they share a common purpose.

Examples of How Theoretical Frameworks May Be Used

Examples of how conceptual frameworks may be used, misconceptions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research’s “uneasy relationship with theory” 4 may be due to several misconceptions. One possible misconception is that qualitative research aims to build theory and thus does not need theoretical grounding. The reality is that all qualitative research methods, not just Grounded Theory studies focused on theory building, may lead to theory construction. 16 Similarly, all types of qualitative research, including Grounded Theory studies, should be guided by research frameworks. 16

Not using a research framework may also be due to misconceptions that qualitative research aims to understand people’s perspectives and experiences without examining them from a particular theoretical perspective or that theoretical foundations may influence researchers’ interpretations of participants’ meanings. In fact, in the same way that participants’ meanings vary, qualitative researchers’ interpretations (as opposed to descriptions) of participants’ meaning-making will differ. 32 , 33 Research frameworks thus provide a frame of reference for “making sense of the data.” 34

Studies informed by well-defined research frameworks can make a world of difference in alleviating misconceptions. Good qualitative reporting requires research frameworks that make explicit the combination of relevant theories, theoretical constructs and concepts that will permeate every aspect of the research. Irrespective of the term used, research frameworks are critical components of reporting not only qualitative but also all types of research.

Building public engagement and access to palliative care and advance care planning: a qualitative study

- Rachel Black ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8952-0501 1 ,

- Felicity Hasson ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8200-9732 2 ,

- Paul Slater ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2318-0705 3 ,

- Esther Beck ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8783-7625 4 &

- Sonja McIlfatrick ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1010-4300 5

BMC Palliative Care volume 23 , Article number: 98 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

33 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Research evidence suggests that a lack of engagement with palliative care and advance care planning could be attributed to a lack of knowledge, presence of misconceptions and stigma within the general public. However, the importance of how death, dying and bereavement are viewed and experienced has been highlighted as an important aspect in enabling public health approaches to palliative care. Therefore, research which explores the public views on strategies to facilitate engagement with palliative care and advance care planning is required.

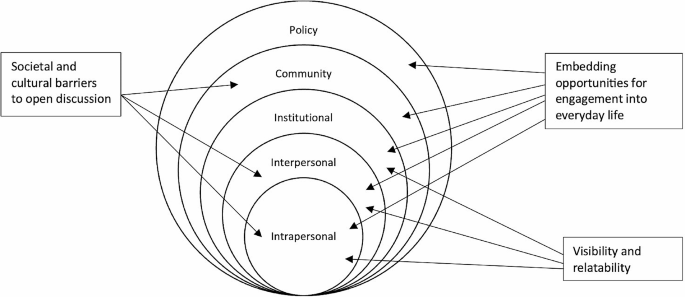

Exploratory, qualitative design, utilising purposive random sampling from a database of participants involved in a larger mixed methods study. Online semi-structured interviews were conducted ( n = 28) and analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Thematic findings were mapped to the social-ecological model framework to provide a holistic understanding of public behaviours in relation to palliative care and advance care planning engagement.

Three themes were generated from the data: “Visibility and relatability”; “Embedding opportunities for engagement into everyday life”; “Societal and cultural barriers to open discussion”. Evidence of interaction across all five social ecological model levels was identified across the themes, suggesting a multi-level public health approach incorporating individual, social, structural and cultural aspects is required for effective public engagement.

Conclusions

Public views around potential strategies for effective engagement in palliative care and advance care planning services were found to be multifaceted. Participants suggested an increase in visibility within the public domain to be a significant area of consideration. Additionally, enhancing opportunities for the public to engage in palliative care and advance care planning within everyday life, such as education within schools, is suggested to improve death literacy and reduce stigma. For effective communication, socio-cultural aspects need to be explored when developing strategies for engagement with all members of society.

Peer Review reports

It is estimated that globally only 14% of patients who require palliative support receive it [ 1 ]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) advocates for palliative care (PC) to be considered a public health issue and suggests earlier integration of PC services within the wider healthcare system is required [ 2 ]. However, research has shown that a lack of public knowledge and misconceptions about PC may deter people from accessing integrative PC services early in a disease trajectory [ 3 ]. Integral to good PC is the facilitation of choice and decision-making, which can be facilitated via advance care planning (ACP). Evidence suggests that ACP can positively impact the quality of end of life care and increase the uptake of palliative care services [ 4 ]. While ACP is commonly associated with end of life (EOL) care, it provides the opportunity for adults of any age to consider their wishes for future care and other financial and personal planning. However, there is evidence of a lack of active engagement in advance care planning (ACP) [ 5 ]. Recent research exploring knowledge and public attitudes towards ACP found just 28.5% of participants had heard the term and only 7% had engaged in ACP [ 6 ]. Barriers to engagement in ACP discussions have been found to include topics such as death and dying are considered a social taboo, posing an increased risk of distress for loved ones; and [ 6 ] a misconception that ACP is only for those at the end of life rather than future planning [ 7 ]. Therefore, there is a need for a public health approach to ACP, to enable and support individuals to engage in conversations about their wishes and make decisions surrounding their future care.

The need for a public health approach to PC, to tackle the challenges of equity and access for diverse populations, was noted in a recent Lancet paper [ 8 ]. This is further supported in a recent review, exploring inequalities in hospice care in the UK, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada which reported that disadvantaged groups such as those with non-cancer illnesses, people living in rural locations and homeless individuals had unequal access to palliative care [ 9 ]. They postulated that differing levels of public awareness in what hospice care provides, and to whom, was an influencing factor with variations in health literacy and knowledge of health services being present in both minority and socioeconomic groups [ 9 ].

Changes in how we experience death and dying have resulted in a shift away from family and community settings into healthcare settings. The Lancet commission exploring the ‘Value of Death’, suggests it has created an imbalance where the value of death is no longer recognised [ 10 ]. The commission’s report posits the need to rebalance death, dying and grieving, where changes across all death systems are required. This needs to consider how the social, cultural, economic, religious, and political factors that determine how death, dying, and bereavement are understood, experienced, and managed [ 10 ].

New public health approaches that aim to strengthen community action and improve death literacy, through increased community responsibility are reflected in initiatives, such as ‘Compassionate Communities’ and ‘Last Aid’ [ 11 , 12 ]. However, a suggested challenge is the management of potential tensions that are present when attempting to conceptualise death in a way that mobilises a whole community [ 13 ]. Whilst palliative care education (PCE) can be effective in improving knowledge and reducing misconceptions, many PCE intervention studies, have focused on carers and healthcare professionals [ 14 ]. Initiatives such as ‘Last Aid’ attempt to bridge this gap by focusing on delivering PCE to the public, however, they are not embedded into the wider social networks of communities. It can be argued that public health campaigns, such as these are falling short by neglecting to use the full range of mass media to suit different ages, cultures, genders and religious beliefs [ 15 ]. Consequently, to understand what is required to engage the public successfully, the voice of the public must lead this conversation. Therefore, this study sought to explore public views on strategies and approaches to enable engagement with palliative care and advance care planning to help share future debate and decision making.

Within the last decades the delivery of PC and ACP have been increasingly medicalised and viewed as a specialist territory, however in reality, the care of those with life-limiting conditions occurs not only within clinical settings but within a social structure that affects the family and an entire community [ 16 ]. Therefore, death, dying and bereavement involve a combination of social, physical, psychological and spiritual events, therefore, to frame PC and ACP within a public health approach the response requires a shift from the individual to understanding the systems and culture within which we live. The Social Ecological Model (SEM) recognises the complex interplay between individual behaviours, and organisational, community, and societal factors that shape our acceptance and engagement. SEM provides a framework to understand the influences affecting engagement with PC and ACP and has been utilised as a lens through which the data in this study is explored.

Qualitative research, using semi-structured interviews were adopted as this enabled an in-depth understanding of public views on strategies to enable engagement with PC. This research was part of a larger mixed-methods study [ 17 ]. Comprehensive Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative research (COREQ) were used [ 18 ](See Supplementary file 1 ).

A purposive random sampling method, using a random number generator, was adopted to recruit participants who consented to be contacted during data collection of a larger mixed methods study. Selected individuals were contacted by telephone and email to invite them to participate. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are outlined in Table 1 . Interested individuals were provided with a participant information sheet detailing the aims of the study and asked to complete a consent form and demographic questionnaire.

A total of 159 participants were contacted, 105 did not respond, 21 declined and three were ineligible to participate. A total of thirty participants consented, however, two subsequently opted to withdraw prior to the interview.

Data collection

Data was collected from December 2022 to March 2023 by RB. The qualitative interview schedule comprised four broad topic areas: (1) participants’ knowledge of PC and ACP; (2) sources of information on PC and ACP and current awareness of local initiatives for public awareness; (3) knowledge of accessibility to PC and ACP and (4) future strategies for promoting public awareness of PC and ACP, with a consideration of supporting and inhibiting factors. The interview schedule was adapted from a previous study on palliative care to incorporate the topic of ACP [ 3 ] (See Supplementary file 2 ). This paper reports on future strategies.

Participants were asked to complete a short demographic questionnaire prior to the interview to enable the research team to describe the characteristics of those who participated. These questions included variables such as age, gender, religion, marital status, behaviour relating to ACP and experience of PC.

Data was collected via online interviews conducted using the videoconferencing platform Microsoft Teams. Interviews lasted between 20 and 60 min and were recorded with participant consent. Data were stored on a secure server and managed through NVivo 12 Software.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were transcribed verbatim automatically by Microsoft Teams and the transcripts were reviewed and mistakes corrected by the interviewer. All identifying information was removed. Transcripts were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis which involved a six-step process: familiarisation, coding, generating initial themes, developing and reviewing themes, refining, defining and naming themes, and writing up [ 19 ]. Themes were derived by exploring patterns, similarities and differences within and across the data in relation to participant’s views on the promotion of PC and ACP and the best ways to engage the public in open discussions.

The study explored the data through a SEM lens to provide a holistic framework for understanding the influences surrounding health behaviour change in relation to palliative care and advance care planning by mapping the findings to each of the SEM constructs.

The SEM for public health was conceptualised by McLeroy et al. [ 20 ]., and was based on previous work by Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory [ 21 ]. The SEM looks to identify social-level determinants of health behaviours [ 22 ]. Five factor levels have been identified within the SEM; (1) Intrapersonal factors (2) Interpersonal processes (3) Institutional factors (4) Community factors and (5) Public policy [ 20 ]. In short, the SEM suggests that the social factors that influence health behaviours on an individual level are nestled within a wider complex system of higher levels. Current research literature has explored SEM as a model for understanding barriers and facilitators to the delivery of PC, adults’ preferences for EOL care and older adults’ knowledge and attitudes of ACP within differing socioeconomic backgrounds [ 23 , 24 , 25 ]. It has demonstrated the importance of a multilevel approach within these populations. However, there is a scarcity of research exploring strategies for public engagement with PC and/or ACP which are underpinned by SEM theory.

To ensure rigour in the analysis four members of the research team (RB, SM, FH, EB) independently reviewed the transcripts and were involved in the analysis and development of themes as a method of confirmability [ 26 ].

Ethical approval was gained from the University Research Ethics Filter Committee prior to commencing data collection. Participants provided written informed consent prior to the commencement of the interviews. They were advised of their right to withdraw, and the confidentiality and anonymity of all data were confirmed. All data was kept in accordance with the Data Protection Act (2018) [ 27 ].

All participants were white; 70% were female (n-19) and 70% were either married or cohabiting (n-19). The largest proportion of the sample 44% was aged under 50 years (n-12), with 22% aged between 50 and 59 (n-6) and 33% (n-9) aged between 60 and 84. Over half of the sample was employed (n-15), 15% were self-employed [ 4 ] whilst 26% were retired (n-7). Demographic data were missing for one of the included participants (see Table 2 ).

Responses to questions relating to ACP knowledge and behaviours found just 12 participants had heard of the term ACP prior to completing the Northern Ireland Life and Times Survey. Furthermore, none of the participants had been offered the opportunity to discuss ACP and none had prepared a plan of their wishes and preferences.

Main findings

Three overarching themes were generated from the data: ‘Visibility and relatability’; ‘Embedding opportunities for engagement into everyday life’; ‘Societal and cultural barriers. These findings were then mapped to the five social ecological model (SEM) levels ( individual; interpersonal; institutional; community; and policy ) to demonstrate the importance of a multilevel approach when seeking to engage the public around PC and ACP. See Fig. 1 for SEM construct mapping.

Theme 1: visibility and relatability

This theme relates to the suggestion that social taboo was a barrier to awareness and the mechanism to ameliorate this was visibility – in turn promoting reduction of stereotypes and promoting understanding and engagement. This posits the idea that the lack of understanding of PC is the root cause of much of the stigma surrounding it. The SEM construct mapping suggests a multilevel approach is required with intrapersonal (increased individual understanding), interpersonal (openness in discussion with friends and family through media normalisation) and institutional (health service policies for promotion and support) levels being identified.

Participants discussed how there is a lack of knowledge on what PC is, with many assuming that it was for people in the latter stages of life or facing end of life care. This highlighted the lack of individual education with participants suggesting that there should be more visibility and promotion on PC and ACP so that individuals are better informed.

“So, it’s really um there needs to be more education, maybe, I think around it. So that people can view it maybe differently or you know talk about it a bit more. Yeah, probably demystifying what it is. This is this is what it is. This isn’t what it is. You know, this isn’t about um, ending your life for you, you know. And this is about giving you choices and ensuring that you know, you know people are here looking after you”(P37538F45) .

However, there was a recognition that individual differences play a part in whether people engage in discussions. A number of participants explored the idea that some people just don’t want to talk about death and that for some it was not a subject that they want to approach. Despite this, there was a sense that increasing visibility was considered important as there will still be many people who are willing to increase their knowledge and understanding of PC and ACP.

“I can talk about it, for example, with one of my sisters, but not with my mom and not with my other sister or my brothers. They just refuse point blank to talk about it…. some of them have done and the others have started crying and just shut me. Shut me off. And just. No, we don’t want to talk about that. So, it just depends on the personality, I suppose” (P14876F59) .

The lack of knowledge and awareness of PC and ACP was suggested to be the attributed to the scarcity of information being made available at a more institutional level. For some participant’s, this was felt to be the responsibility of the health service to ensure the knowledge is out there and being promoted.

“I think people are naive and they know they’re not at that stage and they don’t know what palliative care is, you know. It’s all like it’s ignorance. But our health service is not promoting this. Well in my eyes, they’re not promoting it whatsoever. And they should, they should, because it would help a hell of a lot of people ” (P37172M61). “I and I think it needs to be promoted by the point of contact, whether it’s a GP, National Health, whatever it might be, I think when they’re there, there needs to be a bit more encouragement to have that conversation” (P26495M43) .

The lack of visibility within the general practice was discussed by several participants who said that leaflets and posters would be helpful in increasing visibility. One participant went as far as to say that a member of staff within a GP surgery would be beneficial.