Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on December 17, 2021 by Tegan George . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about peer reviews.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymized) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymized comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymized) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymized) review —where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymized—does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimizes potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymize everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimize back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarize the argument in your own words

Summarizing the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organized. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

Tip: Try not to focus too much on the minor issues. If the manuscript has a lot of typos, consider making a note that the author should address spelling and grammar issues, rather than going through and fixing each one.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticized, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the “compliment sandwich,” where you “sandwich” your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarized or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published. There is also high risk of publication bias , where journals are more likely to publish studies with positive findings than studies with negative findings.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Chi square tests

- Confidence interval

- Quartiles & Quantiles

- Cluster sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Thematic analysis

- Discourse analysis

- Cohort study

- Ethnography

Research bias

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Conformity bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Availability heuristic

- Attrition bias

- Social desirability bias

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilizing rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication. For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project– provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well-regarded.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field. It acts as a first defense, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

George, T. (2023, June 22). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/peer-review/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, what is your plagiarism score.

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

How to Write a Peer Review

When you write a peer review for a manuscript, what should you include in your comments? What should you leave out? And how should the review be formatted?

This guide provides quick tips for writing and organizing your reviewer report.

Review Outline

Use an outline for your reviewer report so it’s easy for the editors and author to follow. This will also help you keep your comments organized.

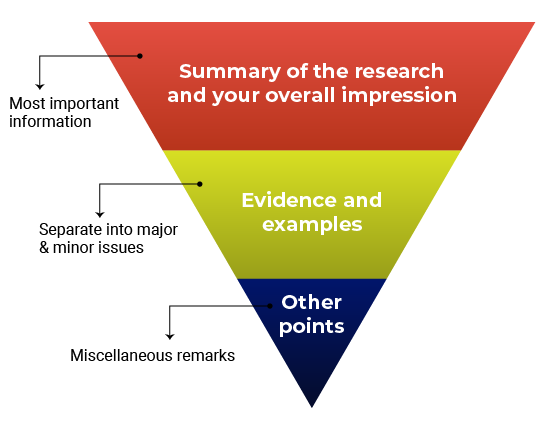

Think about structuring your review like an inverted pyramid. Put the most important information at the top, followed by details and examples in the center, and any additional points at the very bottom.

Here’s how your outline might look:

1. Summary of the research and your overall impression

In your own words, summarize what the manuscript claims to report. This shows the editor how you interpreted the manuscript and will highlight any major differences in perspective between you and the other reviewers. Give an overview of the manuscript’s strengths and weaknesses. Think about this as your “take-home” message for the editors. End this section with your recommended course of action.

2. Discussion of specific areas for improvement

It’s helpful to divide this section into two parts: one for major issues and one for minor issues. Within each section, you can talk about the biggest issues first or go systematically figure-by-figure or claim-by-claim. Number each item so that your points are easy to follow (this will also make it easier for the authors to respond to each point). Refer to specific lines, pages, sections, or figure and table numbers so the authors (and editors) know exactly what you’re talking about.

Major vs. minor issues

What’s the difference between a major and minor issue? Major issues should consist of the essential points the authors need to address before the manuscript can proceed. Make sure you focus on what is fundamental for the current study . In other words, it’s not helpful to recommend additional work that would be considered the “next step” in the study. Minor issues are still important but typically will not affect the overall conclusions of the manuscript. Here are some examples of what would might go in the “minor” category:

- Missing references (but depending on what is missing, this could also be a major issue)

- Technical clarifications (e.g., the authors should clarify how a reagent works)

- Data presentation (e.g., the authors should present p-values differently)

- Typos, spelling, grammar, and phrasing issues

3. Any other points

Confidential comments for the editors.

Some journals have a space for reviewers to enter confidential comments about the manuscript. Use this space to mention concerns about the submission that you’d want the editors to consider before sharing your feedback with the authors, such as concerns about ethical guidelines or language quality. Any serious issues should be raised directly and immediately with the journal as well.

This section is also where you will disclose any potentially competing interests, and mention whether you’re willing to look at a revised version of the manuscript.

Do not use this space to critique the manuscript, since comments entered here will not be passed along to the authors. If you’re not sure what should go in the confidential comments, read the reviewer instructions or check with the journal first before submitting your review. If you are reviewing for a journal that does not offer a space for confidential comments, consider writing to the editorial office directly with your concerns.

Get this outline in a template

Giving Feedback

Giving feedback is hard. Giving effective feedback can be even more challenging. Remember that your ultimate goal is to discuss what the authors would need to do in order to qualify for publication. The point is not to nitpick every piece of the manuscript. Your focus should be on providing constructive and critical feedback that the authors can use to improve their study.

If you’ve ever had your own work reviewed, you already know that it’s not always easy to receive feedback. Follow the golden rule: Write the type of review you’d want to receive if you were the author. Even if you decide not to identify yourself in the review, you should write comments that you would be comfortable signing your name to.

In your comments, use phrases like “ the authors’ discussion of X” instead of “ your discussion of X .” This will depersonalize the feedback and keep the focus on the manuscript instead of the authors.

General guidelines for effective feedback

- Justify your recommendation with concrete evidence and specific examples.

- Be specific so the authors know what they need to do to improve.

- Be thorough. This might be the only time you read the manuscript.

- Be professional and respectful. The authors will be reading these comments too.

- Remember to say what you liked about the manuscript!

Don’t

- Recommend additional experiments or unnecessary elements that are out of scope for the study or for the journal criteria.

- Tell the authors exactly how to revise their manuscript—you don’t need to do their work for them.

- Use the review to promote your own research or hypotheses.

- Focus on typos and grammar. If the manuscript needs significant editing for language and writing quality, just mention this in your comments.

- Submit your review without proofreading it and checking everything one more time.

Before and After: Sample Reviewer Comments

Keeping in mind the guidelines above, how do you put your thoughts into words? Here are some sample “before” and “after” reviewer comments

✗ Before

“The authors appear to have no idea what they are talking about. I don’t think they have read any of the literature on this topic.”

✓ After

“The study fails to address how the findings relate to previous research in this area. The authors should rewrite their Introduction and Discussion to reference the related literature, especially recently published work such as Darwin et al.”

“The writing is so bad, it is practically unreadable. I could barely bring myself to finish it.”

“While the study appears to be sound, the language is unclear, making it difficult to follow. I advise the authors work with a writing coach or copyeditor to improve the flow and readability of the text.”

“It’s obvious that this type of experiment should have been included. I have no idea why the authors didn’t use it. This is a big mistake.”

“The authors are off to a good start, however, this study requires additional experiments, particularly [type of experiment]. Alternatively, the authors should include more information that clarifies and justifies their choice of methods.”

Suggested Language for Tricky Situations

You might find yourself in a situation where you’re not sure how to explain the problem or provide feedback in a constructive and respectful way. Here is some suggested language for common issues you might experience.

What you think : The manuscript is fatally flawed. What you could say: “The study does not appear to be sound” or “the authors have missed something crucial”.

What you think : You don’t completely understand the manuscript. What you could say : “The authors should clarify the following sections to avoid confusion…”

What you think : The technical details don’t make sense. What you could say : “The technical details should be expanded and clarified to ensure that readers understand exactly what the researchers studied.”

What you think: The writing is terrible. What you could say : “The authors should revise the language to improve readability.”

What you think : The authors have over-interpreted the findings. What you could say : “The authors aim to demonstrate [XYZ], however, the data does not fully support this conclusion. Specifically…”

What does a good review look like?

Check out the peer review examples at F1000 Research to see how other reviewers write up their reports and give constructive feedback to authors.

Time to Submit the Review!

Be sure you turn in your report on time. Need an extension? Tell the journal so that they know what to expect. If you need a lot of extra time, the journal might need to contact other reviewers or notify the author about the delay.

Tip: Building a relationship with an editor

You’ll be more likely to be asked to review again if you provide high-quality feedback and if you turn in the review on time. Especially if it’s your first review for a journal, it’s important to show that you are reliable. Prove yourself once and you’ll get asked to review again!

- Getting started as a reviewer

- Responding to an invitation

- Reading a manuscript

- Writing a peer review

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples

Published on 6 May 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on 2 September 2022.

Peer review, sometimes referred to as refereeing , is the process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Using strict criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decides whether to accept each submission for publication.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to the stringent process they go through before publication.

There are various types of peer review. The main difference between them is to what extent the authors, reviewers, and editors know each other’s identities. The most common types are:

- Single-blind review

- Double-blind review

- Triple-blind review

Collaborative review

Open review.

Relatedly, peer assessment is a process where your peers provide you with feedback on something you’ve written, based on a set of criteria or benchmarks from an instructor. They then give constructive feedback, compliments, or guidance to help you improve your draft.

Table of contents

What is the purpose of peer review, types of peer review, the peer review process, providing feedback to your peers, peer review example, advantages of peer review, criticisms of peer review, frequently asked questions about peer review.

Many academic fields use peer review, largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the manuscript. For this reason, academic journals are among the most credible sources you can refer to.

However, peer review is also common in non-academic settings. The United Nations, the European Union, and many individual nations use peer review to evaluate grant applications. It is also widely used in medical and health-related fields as a teaching or quality-of-care measure.

Peer assessment is often used in the classroom as a pedagogical tool. Both receiving feedback and providing it are thought to enhance the learning process, helping students think critically and collaboratively.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Depending on the journal, there are several types of peer review.

Single-blind peer review

The most common type of peer review is single-blind (or single anonymised) review . Here, the names of the reviewers are not known by the author.

While this gives the reviewers the ability to give feedback without the possibility of interference from the author, there has been substantial criticism of this method in the last few years. Many argue that single-blind reviewing can lead to poaching or intellectual theft or that anonymised comments cause reviewers to be too harsh.

Double-blind peer review

In double-blind (or double anonymised) review , both the author and the reviewers are anonymous.

Arguments for double-blind review highlight that this mitigates any risk of prejudice on the side of the reviewer, while protecting the nature of the process. In theory, it also leads to manuscripts being published on merit rather than on the reputation of the author.

Triple-blind peer review

While triple-blind (or triple anonymised) review – where the identities of the author, reviewers, and editors are all anonymised – does exist, it is difficult to carry out in practice.

Proponents of adopting triple-blind review for journal submissions argue that it minimises potential conflicts of interest and biases. However, ensuring anonymity is logistically challenging, and current editing software is not always able to fully anonymise everyone involved in the process.

In collaborative review , authors and reviewers interact with each other directly throughout the process. However, the identity of the reviewer is not known to the author. This gives all parties the opportunity to resolve any inconsistencies or contradictions in real time, and provides them a rich forum for discussion. It can mitigate the need for multiple rounds of editing and minimise back-and-forth.

Collaborative review can be time- and resource-intensive for the journal, however. For these collaborations to occur, there has to be a set system in place, often a technological platform, with staff monitoring and fixing any bugs or glitches.

Lastly, in open review , all parties know each other’s identities throughout the process. Often, open review can also include feedback from a larger audience, such as an online forum, or reviewer feedback included as part of the final published product.

While many argue that greater transparency prevents plagiarism or unnecessary harshness, there is also concern about the quality of future scholarship if reviewers feel they have to censor their comments.

In general, the peer review process includes the following steps:

- First, the author submits the manuscript to the editor.

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to the author, or

- Send it onward to the selected peer reviewer(s)

- Next, the peer review process occurs. The reviewer provides feedback, addressing any major or minor issues with the manuscript, and gives their advice regarding what edits should be made.

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

In an effort to be transparent, many journals are now disclosing who reviewed each article in the published product. There are also increasing opportunities for collaboration and feedback, with some journals allowing open communication between reviewers and authors.

It can seem daunting at first to conduct a peer review or peer assessment. If you’re not sure where to start, there are several best practices you can use.

Summarise the argument in your own words

Summarising the main argument helps the author see how their argument is interpreted by readers, and gives you a jumping-off point for providing feedback. If you’re having trouble doing this, it’s a sign that the argument needs to be clearer, more concise, or worded differently.

If the author sees that you’ve interpreted their argument differently than they intended, they have an opportunity to address any misunderstandings when they get the manuscript back.

Separate your feedback into major and minor issues

It can be challenging to keep feedback organised. One strategy is to start out with any major issues and then flow into the more minor points. It’s often helpful to keep your feedback in a numbered list, so the author has concrete points to refer back to.

Major issues typically consist of any problems with the style, flow, or key points of the manuscript. Minor issues include spelling errors, citation errors, or other smaller, easy-to-apply feedback.

The best feedback you can provide is anything that helps them strengthen their argument or resolve major stylistic issues.

Give the type of feedback that you would like to receive

No one likes being criticised, and it can be difficult to give honest feedback without sounding overly harsh or critical. One strategy you can use here is the ‘compliment sandwich’, where you ‘sandwich’ your constructive criticism between two compliments.

Be sure you are giving concrete, actionable feedback that will help the author submit a successful final draft. While you shouldn’t tell them exactly what they should do, your feedback should help them resolve any issues they may have overlooked.

As a rule of thumb, your feedback should be:

- Easy to understand

- Constructive

Below is a brief annotated research example. You can view examples of peer feedback by hovering over the highlighted sections.

Influence of phone use on sleep

Studies show that teens from the US are getting less sleep than they were a decade ago (Johnson, 2019) . On average, teens only slept for 6 hours a night in 2021, compared to 8 hours a night in 2011. Johnson mentions several potential causes, such as increased anxiety, changed diets, and increased phone use.

The current study focuses on the effect phone use before bedtime has on the number of hours of sleep teens are getting.

For this study, a sample of 300 teens was recruited using social media, such as Facebook, Instagram, and Snapchat. The first week, all teens were allowed to use their phone the way they normally would, in order to obtain a baseline.

The sample was then divided into 3 groups:

- Group 1 was not allowed to use their phone before bedtime.

- Group 2 used their phone for 1 hour before bedtime.

- Group 3 used their phone for 3 hours before bedtime.

All participants were asked to go to sleep around 10 p.m. to control for variation in bedtime . In the morning, their Fitbit showed the number of hours they’d slept. They kept track of these numbers themselves for 1 week.

Two independent t tests were used in order to compare Group 1 and Group 2, and Group 1 and Group 3. The first t test showed no significant difference ( p > .05) between the number of hours for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 2 ( M = 7.0, SD = 0.8). The second t test showed a significant difference ( p < .01) between the average difference for Group 1 ( M = 7.8, SD = 0.6) and Group 3 ( M = 6.1, SD = 1.5).

This shows that teens sleep fewer hours a night if they use their phone for over an hour before bedtime, compared to teens who use their phone for 0 to 1 hours.

Peer review is an established and hallowed process in academia, dating back hundreds of years. It provides various fields of study with metrics, expectations, and guidance to ensure published work is consistent with predetermined standards.

- Protects the quality of published research

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. Any content that raises red flags for reviewers can be closely examined in the review stage, preventing plagiarised or duplicated research from being published.

- Gives you access to feedback from experts in your field

Peer review represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field and to improve your writing through their feedback and guidance. Experts with knowledge about your subject matter can give you feedback on both style and content, and they may also suggest avenues for further research that you hadn’t yet considered.

- Helps you identify any weaknesses in your argument

Peer review acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process. This way, you’ll end up with a more robust, more cohesive article.

While peer review is a widely accepted metric for credibility, it’s not without its drawbacks.

- Reviewer bias

The more transparent double-blind system is not yet very common, which can lead to bias in reviewing. A common criticism is that an excellent paper by a new researcher may be declined, while an objectively lower-quality submission by an established researcher would be accepted.

- Delays in publication

The thoroughness of the peer review process can lead to significant delays in publishing time. Research that was current at the time of submission may not be as current by the time it’s published.

- Risk of human error

By its very nature, peer review carries a risk of human error. In particular, falsification often cannot be detected, given that reviewers would have to replicate entire experiments to ensure the validity of results.

Peer review is a process of evaluating submissions to an academic journal. Utilising rigorous criteria, a panel of reviewers in the same subject area decide whether to accept each submission for publication.

For this reason, academic journals are often considered among the most credible sources you can use in a research project – provided that the journal itself is trustworthy and well regarded.

Peer review can stop obviously problematic, falsified, or otherwise untrustworthy research from being published. It also represents an excellent opportunity to get feedback from renowned experts in your field.

It acts as a first defence, helping you ensure your argument is clear and that there are no gaps, vague terms, or unanswered questions for readers who weren’t involved in the research process.

Peer-reviewed articles are considered a highly credible source due to this stringent process they go through before publication.

In general, the peer review process follows the following steps:

- Reject the manuscript and send it back to author, or

- Lastly, the edited manuscript is sent back to the author. They input the edits, and resubmit it to the editor for publication.

Many academic fields use peer review , largely to determine whether a manuscript is suitable for publication. Peer review enhances the credibility of the published manuscript.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, September 02). What Is Peer Review? | Types & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 15 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/peer-reviews/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a double-blind study | introduction & examples, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, data cleaning | a guide with examples & steps.

Peer Review in Academia

- Open Access

- First Online: 03 January 2022

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Eva Forsberg 5 ,

- Lars Geschwind 6 ,

- Sara Levander 5 &

- Wieland Wermke 7

4237 Accesses

4 Citations

In this chapter, we outline the notion of peer review and its relation to the autonomy of the academic profession and the contract between science and society. This is followed by an introduction of some key themes regarding the practices of peer review. Next, we specify some reasons to further explore different practices of peer review. Briefly, the state of the art is presented. Finally, the structure of this volume and its individual contributions are presented.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Reviewing Peer Review: A Flawed System: With Immense Potential

Mark Lauria

Guidelines for Peer Review. A Survey of International Practices

How to Do a Peer Review?

- Peer review

- Scientific communication

Introduction

Over the past few decades, peer review has become an object of great professional and managerial interest (Oancea, 2019 ) and, increasingly, academic scrutiny (Bornmann, 2011 ; Grimaldo et al., 2018 ). Nevertheless, calls for further research are numerous (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020 ). This volume is in answer to such interest and appeals. We aim to present a variety of peer-review practices in contemporary academic life as well as the principled foundation of peer review in scientific communication and authorship. This volume is unique in that it covers many different practices of peer review and their theoretical foundations, providing both an introduction into the very complex field and new empirical and conceptual accounts of peer review for the interested reader. The contributions are produced by internationally recognized scholars, almost all of whom participated in the conference ‘Scientific Communication and Gatekeeping in Academia in the 21st Century’, held in 2018 at Uppsala University, Sweden. Footnote 1 The overall objective of this volume is explorative; framings relevant to the specific contexts, practices and discourses examined are set by the authors of each chapter. However, some common conceptual points of departure may be laid down at the outset.

Peer review is a context-dependent, relational concept that is increasingly used to denote a vast number of evaluative activities engaged in by a wide variety of actors both inside and outside of academia. By peer review, we refer to peers’ assessments and valuations of the merits and performances of academics, higher education institutions, research organizations and higher education systems. Mostly, these activities are part of more encompassing social evaluation practices, such as reviews of manuscripts, grant proposals, tenure and promotion and quality evaluations of institutions and their research and educational programmes. Thus, scholarly peer review comprises evaluation practices within both the wider international scientific community and higher education systems. Depending on differences related to scientific communities and national cultures, these evaluations may include additional gatekeepers, internal as well as external to academia, and thus the role of the peer may vary.

The roots of peer review can be found in the assessment practices of reviewers and editors of scholarly journals in deciding on the acceptance of papers submitted for publishing. Traditionally, only peers (also known as referees) with recognized scholarly standing in a relevant field of research were acknowledged as experts (Merton, 1942/ 1973 ). Due to the differentiation and increased use of peer review, the notion of a peer employed in various evaluation practices may be extended. Who qualifies as an expert in different peer-review practices and with what implications are empirical issues.

Even though peer review is a familiar phenomenon in most scholarly evaluations, there is a paucity of studies on peer review within the research field of evaluation. Peer review has, however, been described as the most familiar collegial evaluation model, with academic research and higher education as its paradigm area of application and with an ability to capture and judge qualities as its main advantage (Vedung, 2002 ). Following Scriven ( 2003 ), we define evaluation as a practice ‘determining the merit, worth or significance of things’ (p. 15). Scriven ( 1980 ) identifies four steps involved in evaluation practices, which are also frequently used in peer review, either implicitly enacted and negotiated or explicitly stated (Ozeki, 2016 ). These steps concern (1) the criteria of merit, that is, the dimensions of an object being evaluated; (2) the standards of merit, that is, the level of performance in a given dimension; (3) the measuring of performance relative to standards; and (4) a value judgement of the overall worth.

Consequently, the notion of peer review refers to evaluative activities in academia conducted by equals that distribute merit, value and worth. In these processes of selection and legitimation, issues referring to criteria, standards, rating and ranking are significant. Often, peer reviews are embedded in wider evaluation practices of research, education and public outreach. To capture contemporary evaluations of academic work, we will include a number of different review practices, including some in which the term peer is employed in a more extended sense.

The Many Face(t)s of Peer-Review Practices

Depending on the site in which peer review is used, the actors involved differ, as do their roles. The same applies to potential guidelines, purposes, discourses, use of professional judgement and metrics, processes and outcome of the specific peer-review practice. These are all relative to the site in which the review is used and will briefly be commented upon below.

The Interplay of Primary and Secondary Peer Review

It is possible to make a distinction between primary and secondary peer reviews (British Academy, 2007 ). As stated, the primary role of peer review is to assess manuscripts for publishing, followed by the examination and judgement of grant applications. Typically, many other peer-review practices, so-called secondary peer review, involve summaries of outcomes of primary reviews. Thus, we might view primary and secondary reviews as folded into each other, where, for example, reviews of journal articles are prerequisite to later evaluation of the research quality of an institution, in recruitment and promotion, and so forth (Helgesson, 2016 ). Hence, the consequences of primary reviews can hardly be overstated.

Traditionally, both forms of primary peer review (assessment of manuscripts and grant applications) are ex ante evaluations; that is, they are conducted prior to the activity (e.g. publishing and research). With open science, open access journals and changes in the transparency of peer review, open and public peer reviews have partly opened the black box of reviews and the secrecy of the process and its actors (Sabaj Meruane et al., 2016 ). Accordingly, publishing may include both ex ante and ex post evaluations. These forms of evaluation can also be found among secondary reviews, with degree-awarding accreditation an example of the former and reviews of disciplines an example of the latter.

Sites and Reviewer Tasks and Roles

Without being exhaustive, we can list a number of sites where peer review is conducted as part of more comprehensive evaluations: international, regional and national higher education agencies conduct accreditation, quality audits and evaluations of higher education institutions; funding agencies distribute grants for projects and fellowships; higher education institutions evaluate their research, education and public outreach at different levels and assess applications for recruitment, tenure and promotion; the scientific community assesses manuscripts for publication, evaluates doctoral theses and conference papers and allocates awards. The evaluation roles are concerned with the provision of human and financial resources, the evaluation of research products and the assessment of future strategies as a basis for policy and priorities. All of these activities are regularly performed by researchers and interlinked in an evaluation spiral in which the same research may be reviewed more than once (Langfeldt & Kyvik, 2015 ). If we consider valuation and assessment more generally, the list can be extended almost infinitely, with supervision and seminar discussions being typical activities in which valuation plays a central part. Hence, scholars are accustomed to being assessed and to evaluating others.

The role and the task of the reviewer differ also in relation to whether the act of reviewing is performed individually, in teams or in a blending of the two forms. In the evaluation of research grants, the latter is often the case, with reviewers first individually rating or ranking the applications, followed by panel discussions and joint rankings as bases for the final decision made by a committee. In peer review for publishing, there might be a desk rejection by the editor, but if not, two or more external reviewers assess a manuscript and recommend that the editor accept, revise or reject it. It is then up to the editor to decide what to do next and to make the final decision. The process and the expected roles of the involved editor, reviewer and authors may vary depending on whether it is a private publisher or a journal linked to a scientific association, for example. Whether the reviewer should be considered an advisor, an independent assessor, a juror or a judge depends on the context and the task set for the reviewer within the specific site and its policies and practices as well as on various praxes developed over time (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020 ).

Power-making in the Selection of Expertise

The selection process is at the heart of peer review. Through valuations and judgements, peers are participants in decisions on inclusion and exclusion: What project has the right qualities to be allocated funding? Which paper is good enough to be published? And who has the right track record to be promoted or offered a fellowship? When higher education institutions and scholars increasingly depend on external funding, peer review becomes key in who gets an opportunity to conduct research and enter or continue a career trajectory as a researcher and, in many systems, a higher education teacher. In other words, peer review is a cornerstone of the academic career system (Merton, 1968 ; Boyer, 1990 ) and heavily influences what kinds of scientific knowledge will be furthered (Lamont, 2009 ; Aagaard et al., 2015 ).

The interaction involved in peer review may be remote, online or local, including face-to-face collaboration, and it may involve actors with different interests. Moreover, interaction may be extended to the whole evaluation enterprise. For example, evaluations of higher education institutions and their research and education often include members of national agencies, scholarly experts and external stakeholders. Scholarly experts may be internal or external to the higher education institutions and of lower, comparable or higher rank than the subjects of evaluation, and reviewers may be blind or known to those being evaluated and vice versa. Scholarly expertise may also refer to a variety of specialists, for example, to scholars with expertise in a specific research topic, in evaluation technology, in pedagogy or public outreach. A more elaborated list of features to be considered in the allocation of experts to various review practices can be found in a peer-review guide by the European Science Foundation ( 2011 ). At times the notion of peer is extended beyond the classical idea to one with demonstrated competence to make judgements within a particular research field. Who qualifies as a reviewer is contingent on who has the authority to regulate the activity in which the evaluation takes place and who is in the position to suggest and, not least, to select reviewers. This is a delicate issue, imbued with power, and one that we need to further explore, preferably through comparative studies involving different peer-review practices in varying contexts.

Acting as a peer reviewer has become a valuable asset in the scholarly track record. This makes participating as a reviewer important for junior researchers. Therefore, such participation not only is a question of being selected but also increasingly involves self-election. More opportunities are provided by ever more review activities and the prevalence of evaluation fatigue among senior researchers. The limited credit, recognition and rewards for reviewers may also contribute to limited enthusiasm amongst seniors (Research Information Network CIC, 2015 ). Moreover, several tensions embedded in review practices can add to the complexity of the process and influence the readiness to review. The tensions involve potential conflicts between the role of the reviewer or evaluator and the researcher’s role: time conflict (research or evaluate), peer expertise versus impartiality (especially qualified colleagues are often excluded under conflict-of-interest rules), neutral judge versus promoter of research interests (double expectation, deviant assessments versus unanimous conclusions, peer review versus quantitative indicators, and scientific autonomy versus social responsibility) (Langfeldt & Kyvik, 2015 ). Despite noted challenges, classical peer review is still the key mechanism by which professional autonomy and the guarding of research quality are achieved. Thus, it is argued that it is an academic duty and an obligation, in particular for senior scholars, to accept tasks as reviewers (Caputo, 2019 ). Nevertheless, the scholarly exchange value should be addressed in future discussions of gatekeeping in academia.

The Academic Genres of Peer Review

Peer reviews are rooted in more encompassing discourses, such as those concerning norms of science, involving notions of quality and excellence founded in different sites endogenous or exogenous to science. Texts subject to or employed or produced in peer-review practices represent a variety of academic genres, including review reports, editors’ letters, applicants’ proposals, submitted manuscripts, guidelines, applicant dossiers and curriculum vitae (CVs), testimonials, portfolios and so on. Different genres are interlinked in chains, creating systems of genres. A significant aspect of systems is intertextuality, or the fact that texts within a specific system refer to, anticipate and shape each other. The interdependence of texts is about how they relate to situational and formal expectations—in this case, of the specific peer-review practice. It is also about how one text makes references to another text; for example, review reports often refer to guidelines, calls, announcements or texts in application dossiers. The interdependence can also be seen in how the texts interact in academic communities (Chen & Hyon, 2005 ): who the intended readers of a given text are, what the purpose of the text is, how the text is used in the review and decision process, and so on. Conclusively, the genre systems of peer review vary depending on epistemic traditions, national culture and regulations of higher education systems and institutions.

Given this diversity, we are dealing with a great number of genre systems involving different kinds of texts and interrelations embedded in power and hierarchies. A significant feature of peer-review texts as a category is the occluded genres, that is, genres that are more or less closed to the public (Swales, 1996 ). Depending on the context, the list of occluded genres varies. For example, the submission letters, submitted manuscripts, review reports and editor–author correspondence involved in the eventual publication of articles in academic journals are not made publicly available, while in the context of recruitment and promotion, occluded genres include application letters, testimonials and evaluation letters to committees. And for research grants, the research proposals, individual review reports and panel reports tend to remain entirely internal to the grant-making process. However, in some countries (e.g. in Sweden, due to the principle of openness, or offentlighetsprincipen ), several of these types of texts may be publicly available.

The request for open science has also initiated changes to the occluded genres of peer review. After a systematic examination, Ross-Hellauer ( 2017 ) proposed ‘open peer review’ as an umbrella term for a variety of review models in line with open science, ‘including making reviewer and author identities open, publishing review reports and enabling greater participation in the peer review process’ (p. 1). From 2005 onwards, there has been a big upswing of these definitions. This correlates with the rise of the openness agenda, most visible in the review of journal articles and within STEM and interdisciplinary research.

Time and space are central categories in most peer-review genres and the systems to which they belong. While review practices often look to the past, imagined futures also form the background for valuation. The future orientation is definitely present in audits, in assessments of grant proposals and in reviews of candidates’ track records. The CV, a key text in many review practices, may be interpreted in terms of an applicant’s career trajectory, thus emphasizing how temporality and spatiality interact within a narrative infrastructure, for example how scholars move between different academic institutions over time (Hammarfelt et al., 2020 ). Texts may also feed both backwards and forwards in the peer-review process. For example, guidelines and policy on grant evaluations and distribution may be negotiated and acted upon by both applicants and reviewers. Candidates may also address reviewers as significant others in anticipating the forthcoming reviewer report (Serrano Velarde, 2018 ). These expectations on the part of the applicant can include prior experiences and perceptions of specific review practices, processes and outcomes in specific circumstances.

Turning to the reviewer report, it is worth noting that they are often written in English, especially ones assessing manuscripts and frequently those on research proposals and recruitment applications as well. Commonly seen within the academic genre of peer review is the use of indirect speech, which can be linked to the review report’s significance as related to the identity of the person being evaluated (Paltridge, 2017 ). Two key notions, politeness and face, have been used to describe the evaluative language of review reports and how reviewers interact with evaluees. There are differences related to content and to whether a report is positive or negative overall in its evaluation. For example, reviewers of manuscripts invoke certain structures of knowledge, using different structures when suggesting to reject, revise or accept and when asking for changes. To maintain social relationships, reviewers draw on different politeness strategies to save an author’s face. Strategies employed may include ‘apologizing (‘I am sorry to have to’) and impersonalizing an issue (‘It is generally not acceptable to’)’ (Paltridge, 2017 , p. 91). Largely, requests for changes are made as directions, suggestions, clarifications and recommendations. Thus, for both evaluees and researchers of peer reviews, particular genre competences are required to decode and act upon the reports. For beginning scholars unfamiliar with the world of peer review or for scholars from a different language or cultural background than the reviewer, it might be challenging to interpret, negotiate and act upon reviewer reports.

Criteria and the Professional Judgement of Quality

According to the classical idea of peer review, only a peer can properly recognize quality within a given field. Although, in both research and scholarly debate, shortcomings have been emphasized regarding the trustworthiness, efficacy, expense, burden and delay of peer review (Bornmann, 2013 ; Research Information Network CIC, 2015 ), many critics still find peer review as the least-worst system, in the absence of viable alternatives. Overall, scholars stand behind the idea of peer review even though they often have concerns regarding the different practices of peer review (Publons, 2018 ).

Calls for accountability and social relevance have been made, and there have been requests for formalization, standardization, transparency and openness (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020 ). While the idea of formalization of peer review refers to rules, including the development of policy and guidelines for different forms of peer review, standardization rather emphasizes the setting of standards through the employment of specific tools for evaluation (i.e. criteria and indicators used for assessment, rating or ranking and decision-making). An interesting question is whether standardization will impact the extent and the way peers are used in different sites of evaluation (Westerheijden et al., 2007 ). We may add, who will be considered a peer and what will the matching between the evaluator and the evaluation object or evaluee look like?

It is widely acknowledged that criteria is an essential element of any procedure for judging merit (Scriven, 1980 ; Hug & Aeschbach, 2020 ). This is the case regardless of whether criteria are determined in advance or if they are explicitly expressed or implicitly manifested in the process of assessment. The notion of peer review has been supplemented in various ways, implicating changes to the practice and records of peer review. Increasingly, review reports combine classical peer review with metrics of different kinds. Accordingly, quantitative measures, taken as proxies for quality, have entered practices of peer review. Today, blended forms are rather common, especially in evaluations of higher education institutions, where narrative and metric summaries often supplement each other and inform a judgement.

In general, quantitative indicators (e.g. number of publications, journal impact factors, citations) are increasingly applied, even though their capacity to capture quality is questioned, especially within the social sciences, humanities and the arts. Among the main reasons given for the rapid growth of demands for metrics, one of the arguments we find is that classic peer review alone cannot meet the quest for accountability and transparency, and bibliometric evaluations may appear cheaper, more objective and legitimated. Moreover, metrics may give an impression of accessibility for policy and management (Gläser & Laudel, 2007 ; Söderlind & Geschwind, 2019 ). However, tensions between classical peer review and quantitative indicators have been identified and are hotly debated (Langfeldt & Kyvik, 2011 ). The dramatic expansion of the use of metrics has brought with it gaming and manipulation practices to enhance reputation and status, ‘including coercive citation, forced joint authorship, ghostwriting, h-index manipulation, and many others’ (Oravec, 2019 , p. 859). Warnings are also issued against the use of bibliometric indicators at the individual level. A combination of peer narratives and metrics is, however, considered a possibility to improve an overall evaluation, given due awareness of the limitations of quantitative data as proxies for quality.

The literature on peer review has focused more on the weighting of criteria than on the meaning referees assign to the criteria they use (Lamont, 2009 ). Even though some criteria, such as originality, trustworthiness and relevance, are frequently used in the assessment of academic work and proposals, our knowledge of how reviewers ascribe value to, assess and negotiate them remains limited (Hug & Aeschbach, 2020 ). However, Joshua Guetzkow, Michèle Lamont and Grégoire Mallard ( 2004 ) show that panellists in the humanities, history and the social sciences define originality much more broadly than what is usually the case in the natural sciences.

Criteria, indicators and comparisons are unstable: they are situational and dependent on context and a referee’s personal experience of scientific work (Kaltenbrunner & de Rijcke, 2020 ). We are dealing here with assessments in situations of uncertainty and of entities not easily judged or compared. The concept of judgement devices has been used to capture how reviewers delegate the judgement of quality to proxies, reducing the complexity of comparison. For example, the employment of central categories in a CV, which references both temporal and spatial aspects of scholars’ trajectories, makes comparison possible (Hammarfelt, 2017 ). In a similar way, the theory of anchoring effects has been used to explore reviewers’ abilities to discern, assess, compare and communicate what scientific quality is or may be (Roumbanis, 2017 ). Anchoring effects have their roots in heuristic principles used as shortcuts in everyday problem solving, especially when a judgement involves intuition. Reduction of complexity is visible also in how reviewers first collect criteria that consist of information that has an eliminatory function. Next, they search for positive signs of evidence in order to make a final judgement (Musselin, 2002 ). Dependent on context and situations, reviewers tend to select different criteria from a repertoire of criteria (Hug & Aeschbach, 2020 ).

On the one hand, the complexity of academic evaluations requires professional judgement: scholars sufficiently grounded in a field of research and higher education are entrusted with interpreting and negotiating criteria, indicators and merits. Still, the practice of peer review has to be safeguarded against the risk of conservatism as well as epistemic and social biases (Kaltenbrunner & de Rijcke, 2020 ). On the other hand, changes in the governance of higher education institutions and research, as well as marketization, managerialism, digitalization and calls for accountability, have increased the diversity of peer review and introduced new ways to capture and employ criteria and indicators. The long-term consequences of these changes need to be monitored, not least because of how they challenge the self-regulation and autonomy of the academic profession (Oancea, 2019 ).

How to understand, assess, measure and value quality in research, the career of a scholar or the performances of a higher education institution are complex issues. Turning to the notion of quality in a general sense will not solve the problem, since it has so many facets and has been perceived in so many different ways, including as fitness for purpose, as eligible, as excellent and as value for money (Westerheijden et al., 2007 ), all notions in need of contextualization and further elaboration to achieve some sense (see also Elken & Wollscheid, 2016 ).

When presenting a framework to study research quality, Langfeldt et al. ( 2020 ) identify three key dimensions: (1) quality notions originating in research fields and in research policy spaces; (2) three attributes important for good research and drawn on existing studies, namely, originality/novelty, plausibility/reliability and value or usefulness; and (3) five sites where notions of research quality emerge, are contested and are institutionalized, comprising researchers, knowledge communities, research organizations, funding agencies and national policy arenas. This multidimensional framework and its components highlight issues that are especially relevant to studies of peer review. The sites identify arenas where peer review functions as a mechanism through which notions of research quality are negotiated and established. The consideration of notions of quality endogenous and exogenous to scientific communities and the various attributes of good research can also be directly linked to referees’ distribution of merit, value and worth in peer-review practices under changing circumstances.

The Autonomy of a Profession and a Challenged Contract

Historical analyses link peer review to the distribution of authority and the negotiations and reformulations of the public status of science (Csiszar, 2016 ). At stake in renegotiations of the contract between science and society are the professional autonomy of scholars and their work. Peer review is contingent on the prevailing contract and is critical in maintaining the credibility and legitimacy of research and higher education (Bornmann, 2011 ). The professional autonomy of scholars raises the issue of self-regulation. Its legitimacy ultimately comes down to who decides what, particularly concerning issues of research quality and scientific communication (Clark, 1989 ).

Over the past 40 years, major changes have taken place in many OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries in the governance of public science and higher education, changes which have altered the relative authority of different groups and organizations (Whitley, 2011 ). The former ability of scientific elites to exercise endogenous control over science has, particularly since the 1960s, become more contested and subject to public policy priorities. A more heterogeneous and complex higher education system has been followed by the exogeneity of governance mechanisms, formal rules and procedures, and the institutionalization of quality assurance procedures and performance monitoring. Expectations of excellence, competition for resources and reputation, and the coordination of research priorities and intellectual judgement have changed across disciplinary and national boundaries to varying degrees (Whitley, 2011 ). These developments can be seen as expressions of the evaluative state (Neave, 1998 ), the audit society (Power, 1997 ) and as part of an institutionalized evaluation machinery (Dahler Larsen, 2012 ).

Changes in the principles of governance are underpinned by persistent tensions around accountability, evaluation, measurement, demarcation, legitimation, agency and identity in research (Oancea, 2019 ). Besides the primary form of recognition through peer review, the weakened autonomy of academic fields has added new evaluative procedures and institutions. Academic evaluations, such as accreditations, audits and quality assurances, and evaluations of research performance and social impact now exist alongside more traditional forms (Hansen et al., 2019 ).

Higher education institutions worldwide have experienced the emergence and manifestations of the quality movement, which is part of interrelated processes such as massification, marketization and managerialism. Through organizations at international, national and institutional levels, a variety of technologies have been introduced to identify, measure and compare the performance of higher education institutions (Westerheijden et al., 2007 ). These developments have emphasized external standards and the use of bibliometrics and citation indexes, which have been criticized for rendering the evaluations more mechanical (Hamann & Beljean, 2017 ). Mostly, peer review, often in combination with self-evaluation, is also employed in the more recently introduced forms of evaluation (Musselin, 2013 ). Accordingly, peer review, in one form or another, is still a key mechanism monitoring the flow of scientific knowledge, ideas and people through the gates of the scientific community and higher education institutions (Lamont, 2009 ).

Autonomy may be defined as ‘the quality or state of being self-governing’ (Ballou, 1998 , p. 105). Autonomy is thus the capacity of an agent to determine their own actions through independent choice, in this case within a system of principles and laws to which the agent is dedicated. The academic profession governs itself by controlling its members. Academics control academics, peers control peers, in order to maintain the status and indeed the autonomy of the profession. Fundamentally, professionals are licensed to act within a valuable knowledge domain. By training, examination and acknowledgement, professionals are legitimated (at least politically) experts of their domain. The rationale of licence and the esotericism of professional knowledge raise the question of how professionals and their work can be evaluated and by which standards. There are rules of conduct and ethical norms, but these are ultimately owned and controlled by the academic profession. From this perspective, we can understand peer review as the structural element that holds academia together.

The increase of peer-review practices in academia can be compared with other professions that also must work harder than before to maintain their status and autonomy. In many cases, their competence and quality must be displayed much more visibly today. Pluralism and individualism in society have also resulted in a plurality of expertise and a decrease of mono-vocational functional systems. A mystique of academic knowledge (as in ‘the research says’) is not as acceptable in public opinion today as it once was. The term ‘postmodern professionals’ is suggested to describe experts who expend more effort in the dramaturgy of their competences than people in their positions might have in the past in order to generate trust in clients and in society (Pfadenhauer, 2003 ). Media makes professional competences, performances and failures much more visible and contributes to trust or mistrust in professions. In a pluralist society, extensive use of peer review may indeed function as a strategy to make apparent quality visible and secure the autonomy of the academic profession, which owns the practice of peer review and knows how to adjust it to its needs.

While most academic evaluations exist across scientific communities and disciplines, the criteria of evaluation can differ substantially between and within communities (Hamann & Beljean, 2017 ). Thus, research on peer review needs to take disciplinary and interdisciplinary similarities and differences seriously. Obviously, the impact of the intellectual and social organization of the sciences (Whitley, 1984 ), the mode of research (Nowotny et al., 2001 ), the tribes and territories (Becher, 1989 ; Becher & Trowler, 2001 ; Trowler et al., 2014 ) and the epistemic cultures (Knorr Cetina, 1999 ) need to be better represented in future research. Then, examinations of peer review may contribute also to a fuller understanding of the contract between science and society and the challenges directed towards the professional autonomy of academics.

Why Study Peer Review?

As an ideal, peer review has been described as ‘the linchpin of science’ (Ziman, 1968 , p. 148) and a key mechanism in the distribution of status and recognition (Merton, 1968 ) as well as part and parcel of collegiality and meritocracy (Cole & Cole, 1973 ). Above all, peer review is considered a gatekeeper regarding the quality of science both in various specialized knowledge communities and in research policy spaces (Langfeldt et al., 2020 ). Peer review is often taken as a hallmark of quality, expected to both guard and enhance quality. Early on, peer review, or refereeing, was linked to moral institutionalized imperatives. Perhaps most known are those formulated in the Ethos of Science by Merton (1942/ 1973 ): communism, universalism, disinterestedness and organized scepticism, or CUDOS. These norms and their counter-norms (individualism, particularism, interestedness and dogmatism) have frequently been the focus of peer-review studies. Norms on how scientific work is or should be carried out and how researchers should behave reflect the purpose of science, and ideas of how science should be governed, and are thus directly linked to the autonomy of the academic profession (Panofski, 2010 ). In short, research into peer review goes to the very heart of academia and its relation to society. This calls for scrutiny.

With changing circumstances, peer review is more often employed, and its purposes, forms and functions are increasingly diversified. Today, academic evaluations permeate every corner of the scientific enterprise, and the traditional form of peer review, rooted in scientific communication, has migrated. Thus, we have seen peer review evolve to be undertaken in all key aspects of academic life: research, teaching, service and collaboration with society (Tennant & Ross-Hellauer, 2020 ). Increasingly, peer review is regarded as the standard, not only for published scholarship but also for academic evaluations in general. Ideally, peer review is considered to guarantee quality in research and education while upholding the norms of science and preserving the contract between science and society. The diversity and the migration of review practices and its consequences should be followed closely.

In the course of a career, scholars are recurrently involved as both reviewers and reviewees, and this is becoming more and more frequent. As stated in a report on peer review by the British Academy ( 2007 ), the principle of judge not, that ye be not judged is impossible to follow in academic life. On the contrary, the selection of work for publishing, the allocation of grants and fellowships, decisions on tenure and promotion, and quality evaluations all depend upon the exercise of judgement. ‘The distinctive feature of this academic judgement is that it is reciprocal. Its guiding motto is: judge only if you in turn are prepared to be judged’ (British Academy, 2007 , p. vii).

Indeed, we lack comprehensive statistics on peer review and the involvement of scholars in its diverse practices. However, investigations like the Wiley study (Warne, 2016 ) and Publons’ ( 2018 ) Global State of Peer Review (2018), both focused on reviews of manuscripts, implicate the widespread and increasing use of peer review. In 2016, roughly 2.9 million peer-reviewed articles were indexed in Web of Science, and a total of 2.5 million manuscripts were rejected. Estimated reviews each year amount to 13.7 million. Together, the continuous rise of submissions and the increase in evaluations using peer reviews expose the system and its actors to ever more pressure.