The Mexican-American War Essay

The US-Mexican War started on 25 April 1846 and lasted for 2 years until 1848 (Bauer, 1992). The war broke out mainly because both the US and Mexico were interested in Texas, which had gained independence from Mexico in 1836. People have divided opinion on whether the US should have been involved in this war. On one side, some people argue that the US should not have been involved in the war because it had refused to incorporate Texas into the Union in 1836 after gaining independence. On the other side, some individuals hold that the US should have been involved in the war as retaliation after Mexico attacked American soldiers on the disputed land. However, this paper holds that the US should not have engaged in the 1846 Mexican-American War.

The Mexican president at the time, Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna, had warned the US that any efforts to annex Texas would break the already fragile relationship between Mexico and the US (Frazier, 1998). However, the US president at the time ignored such warnings. Mexico and the US were equal partners in the region, and President James Polk should have respected the calls to leave Texas alone. The Mexican president was only concerned about the peace of the region. President de Santa Anna even went to the extent of begging the US to stay out of Texas, but President Polk was determined to annex Texas to the Union. Therefore, for the interest of peace in the region, the US should not have engaged Mexico in this bloody war.

To show its commitment to resolve the Texan conflict amicably, the Mexican government decided to negotiate with a low-level US government official. Having a low-level government official would keep politics out of the already volatile issue. However, the US government would not divorce the politics of supremacy from the confrontation, and thus it sent a minister to negotiate with Mexico. At this point, it is clear that the US was set for a military confrontation by defying all the demands from the Mexican government. If the US sent a low-profile government official as required, perhaps the war would have been averted.

However, the proponents of the war argue that Mexico had to be held responsible for attacking American troops and killing two officers (Henderson, 2008). Apparently, Mexico had no right to dictate whether Texas wanted to join the Union or remain an independent country. Texas needed help from its allies after being ravaged by the struggle for independence from Mexico. Therefore, the US was simply helping its ally at the time of need through annexation. Additionally, Mexico refused to honor its promise of receiving the US emissary with honor befitting an American government official in foreign land. Therefore, Mexico pushed the US into the war.

In conclusion, there are compelling reasons explaining why the US should or should not have engaged in the Mexican-American War. However, the US should not have engaged in the war. Mexico had categorically stated that the annexation of Texas to the United States would cause conflicts in the region, and President Polk should have respected this stand. Besides, Mexico indicated its willingness to negotiate with a low-profile US government official. However, the US sent a high-ranking minister in the government.

The proponents of the war hold that Mexico had no right to determine if Texas would join the US. However, this argument is weak because Mexico wanted peace in the region and the US should have respected that view. Therefore, the arguments on why the US should not have engaged in the war are highly compelling because peace should surpass supremacy battles.

Bauer, J. (1992). The Mexican War: 1846–1848 . Winnipeg, MB: Bison Books.

Frazier, D. (1998). The U.S. and Mexico at war . Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan.

Henderson, T. (2008). A glorious defeat: Mexico and its war with the United States. New York, NY: Hill and Wang.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, August 25). The Mexican-American War. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-mexican-american-war/

"The Mexican-American War." IvyPanda , 25 Aug. 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/the-mexican-american-war/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'The Mexican-American War'. 25 August.

IvyPanda . 2020. "The Mexican-American War." August 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-mexican-american-war/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Mexican-American War." August 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-mexican-american-war/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Mexican-American War." August 25, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-mexican-american-war/.

- James K. Polk: One of the Strongest of All Presidents

- Mexican-American-War and the Role of Texas Rangers

- The Mexican War 1846-1848

- The US Militia Role in the Mexican-American War

- American Efforts in Mexican-American War

- Mexican-American Cuisine Artifact

- Civil War in Mississippi. “Free State of Jones” Film

- The US History and War on Mexico

- The History of the Mexican–American War

- Civil War and Supreme Court: The Enforcement of the Slave-Trade Laws

- Peace Importance and War Effects on Countries

- "The Accidental Guerrilla" by David Kilcullen

- Optional Self-Defence War Against Lesser Aggressor

- Vietnamese in Greene's The Quiet American and Terry's Bloods

- The American Combat Soldier in Vietnam by Grunts

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Mexican-American War

By: History.com Editors

Updated: August 10, 2022 | Original: November 9, 2009

The Mexican-American War of 1846 to 1848 marked the first U.S. armed conflict chiefly fought on foreign soil. It pitted a politically divided and militarily unprepared Mexico against the expansionist-minded administration of U.S. President James K. Polk, who believed the United States had a “Manifest Destiny” to spread across the continent to the Pacific Ocean. A border skirmish along the Rio Grande that started off the fighting was followed by a series of U.S. victories. When the dust cleared, Mexico had lost about one-third of its territory, including nearly all of present-day California, Utah, Nevada, Arizona and New Mexico.

Causes of the Mexican-American War

Texas gained its independence from Mexico in 1836. Initially, the United States declined to incorporate it into the union, largely because northern political interests were against the addition of a new state that supported slavery . The Mexican government was also encouraging border raids and warning that any attempt at annexation would lead to war.

Did you know? Gold was discovered in California just days before Mexico ceded the land to the United States in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

Nonetheless, annexation procedures were quickly initiated after the 1844 election of Polk, a firm believer in the doctrine of Manifest Destiny , who campaigned that Texas should be “re-annexed” and that the Oregon Territory should be “re-occupied.” Polk also had his eyes on California , New Mexico and the rest of what is today the American Southwest.

When his offer to purchase those lands was rejected, he instigated a fight by moving troops into a disputed zone between the Rio Grande and Nueces River that both countries had previously recognized as part of the Mexican state of Coahuila .

The Mexican-American War Begins

On April 25, 1846, Mexican cavalry attacked a group of U.S. soldiers in the disputed zone under the command of General Zachary Taylor , killing about a dozen. They then laid siege to Fort Texas along the Rio Grande. Taylor called in reinforcements, and—with the help of superior rifles and artillery—was able to defeat the Mexicans at the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Resaca de la Palma .

Following those battles, Polk told the U.S. Congress that the “cup of forbearance has been exhausted, even before Mexico passed the boundary of the United States, invaded our territory, and shed American blood upon American soil.” Two days later, on May 13, Congress declared war, despite opposition from some northern lawmakers. No official declaration of war ever came from Mexico.

U.S. Army Advances Into Mexico

At that time, only about 75,000 Mexican citizens lived north of the Rio Grande. As a result, U.S. forces led by Col. Stephen Watts Kearny and Commodore Robert Field Stockton were able to conquer those lands with minimal resistance. Taylor likewise had little trouble advancing, and he captured the city of Monterrey in September.

With the losses adding up, Mexico turned to old standby General Antonio López de Santa Anna , the charismatic strongman who had been living in exile in Cuba. Santa Anna convinced Polk that, if allowed to return to Mexico, he would end the war on terms favorable to the United States.

But when Santa Anna arrived, he immediately double-crossed Polk by taking control of the Mexican army and leading it into battle. At the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, Santa Anna suffered heavy casualties and was forced to withdraw. Despite the loss, he assumed the Mexican presidency the following month.

Meanwhile, U.S. troops led by Gen. Winfield Scott landed in Veracruz and took over the city. They then began marching toward Mexico City, essentially following the same route that Hernán Cortés followed when he invaded the Aztec empire .

The Mexicans resisted at the Battle of Cerro Gordo and elsewhere, but were bested each time. In September 1847, Scott successfully laid siege to Mexico City’s Chapultepec Castle . During that clash, a group of military school cadets–the so-called ni ños héroes –purportedly committed suicide rather than surrender.

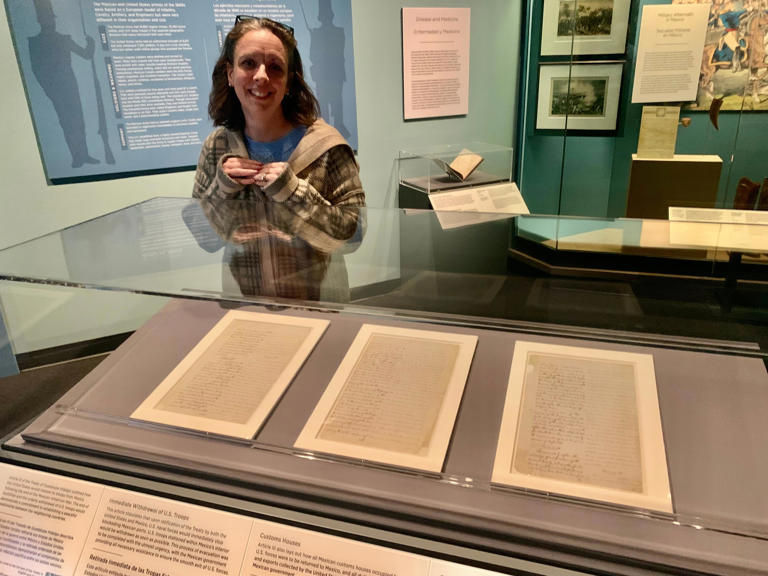

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo

Guerrilla attacks against U.S. supply lines continued, but for all intents and purposes the war had ended. Santa Anna resigned, and the United States waited for a new government capable of negotiations to form.

Finally, on Feb. 2, 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, establishing the Rio Grande (and not the Nueces River) as the U.S.-Mexican border. Under the treaty, Mexico also recognized the U.S. annexation of Texas, and agreed to sell California and the rest of its territory north of the Rio Grande for $15 million plus the assumption of certain damage claims.

The net gain in U.S. territory after the Mexican-American War was roughly 525,000 square miles, an enormous tract of land—nearly as much as the Louisiana Purchase’s 827,000 square miles—that would forever change the geography, culture and economy of the United States.

Though the war with Mexico was over, the battle over the newly acquired territories—and whether or not slavery would be allowed in those territories—was just beginning. Many of the U.S. officers and soldiers in the Mexican-American War would in just a few years find themselves once again taking up arms, but this time against their own countrymen in the Civil War .

HISTORY Vault

Stream thousands of hours of acclaimed series, probing documentaries and captivating specials commercial-free in HISTORY Vault

The Mexican American War. PBS: American Experience . The Mexican-American war in a nutshell. Constitution Daily . The Mexican-American War. Northern Illinois University Digital Library ..

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- Search Menu

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Why Publish with JAH?

- About Journal of American History

- About the Organization of American Historians

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

The Dead March: A History of the Mexican-American War

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Samuel J. Watson, The Dead March: A History of the Mexican-American War, Journal of American History , Volume 105, Issue 3, December 2018, Pages 667–668, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jay319

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This superb work demonstrates both the strengths and limitations of the social and cultural turns in military history. A synthesis of much of the last generation of specialized scholarship, including Peter Guardino's significant contributions regarding Mexican society and politics, it is above all a “social and cultural history,” and by far the best such available, especially for the Mexican experience of the Mexican-American War. But the role of the state, whether in encouraging economic growth or fashioning military power, remains less developed.

Guardino's thesis is that Mexico was defeated by American economic power and Mexican poverty, rather than Mexican disunity, which many historians have emphasized. Yet he takes American wealth as a given, without citations to Paul A. C. Koistinen, Max Edling, or James Cummings. More important, how can we distinguish between poverty and disunity? To what extent did disunity—lack of national cohesion or of agreement about national purpose—limit growth? Acknowledging that Mexicans felt a strong national consciousness does not mean that their efforts were united. In contrast, the United States possessed both an ideology of racialized expansion that ultimately provided sufficient unity to conduct the war, and an economy that gave it substantial margin for error.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Process - a blog for american history

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1945-2314

- Print ISSN 0021-8723

- Copyright © 2024 Organization of American Historians

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

11.4 The Mexican-American War, 1846–1848

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify the causes of the Mexican-American War

- Describe the outcomes of the war in 1848, especially the Mexican Cession

- Describe the effect of the California Gold Rush on westward expansion

Tensions between the United States and Mexico rapidly deteriorated in the 1840s as American expansionists eagerly eyed Mexican land to the west, including the lush northern Mexican province of California. Indeed, in 1842, a U.S. naval fleet, incorrectly believing war had broken out, seized Monterey, California, a part of Mexico. Monterey was returned the next day, but the episode only added to the uneasiness with which Mexico viewed its northern neighbor. The forces of expansion, however, could not be contained, and American voters elected James Polk in 1844 because he promised to deliver more lands. President Polk fulfilled his promise by gaining Oregon and, most spectacularly, provoking a war with Mexico that ultimately fulfilled the wildest fantasies of expansionists. By 1848, the United States encompassed much of North America, a republic that stretched from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

JAMES K. POLK AND THE TRIUMPH OF EXPANSION

A fervent belief in expansion gripped the United States in the 1840s. In 1845, a New York newspaper editor, John O’Sullivan, introduced the concept of “manifest destiny” to describe the very popular idea of the special role of the United States in overspreading the continent—the divine right and duty of White Americans to seize and settle the American West, thus spreading Protestant, democratic values. In this climate of opinion, voters in 1844 elected James K. Polk, a slaveholder from Tennessee, because he vowed to annex Texas as a new slave state and take Oregon.

Annexing Oregon was an important objective for U.S. foreign policy because it appeared to be an area rich in commercial possibilities. Northerners favored U.S. control of Oregon because ports in the Pacific Northwest would be gateways for trade with Asia. Southerners hoped that, in exchange for their support of expansion into the northwest, northerners would not oppose plans for expansion into the southwest.

President Polk—whose campaign slogan in 1844 had been “Fifty-four forty or fight!”—asserted the United States’ right to gain full control of what was known as Oregon Country, from its southern border at 42° latitude (the current boundary with California) to its northern border at 54° 40' latitude. According to an 1818 agreement, Great Britain and the United States held joint ownership of this territory, but the 1827 Treaty of Joint Occupation opened the land to settlement by both countries. Realizing that the British were not willing to cede all claims to the territory, Polk proposed the land be divided at 49° latitude (the current border between Washington and Canada). The British, however, denied U.S. claims to land north of the Columbia River (Oregon’s current northern border) ( Figure 11.13 ). Indeed, the British foreign secretary refused even to relay Polk’s proposal to London. However, reports of the difficulty Great Britain would face defending Oregon in the event of a U.S. attack, combined with concerns over affairs at home and elsewhere in its empire, quickly changed the minds of the British, and in June 1846, Queen Victoria’s government agreed to a division at the forty-ninth parallel.

In contrast to the diplomatic solution with Great Britain over Oregon, when it came to Mexico, Polk and the American people proved willing to use force to wrest more land for the United States. In keeping with voters’ expectations, President Polk set his sights on the Mexican state of California. After the mistaken capture of Monterey, negotiations about purchasing the port of San Francisco from Mexico broke off until September 1845. Then, following a revolt in California that left it divided in two, Polk attempted to purchase Upper California and New Mexico as well. These efforts went nowhere. The Mexican government, angered by U.S. actions, refused to recognize the independence of Texas.

Finally, after nearly a decade of public clamoring for the annexation of Texas, in December 1845 Polk officially agreed to the annexation of the former Mexican state, making the Lone Star Republic an additional slave state. Incensed that the United States had annexed Texas, however, the Mexican government refused to discuss the matter of selling land to the United States. Indeed, Mexico refused even to acknowledge Polk’s emissary, John Slidell, who had been sent to Mexico City to negotiate. Not to be deterred, Polk encouraged Thomas O. Larkin, the U.S. consul in Monterey, to assist any American settlers and any Californios , the Mexican residents of the state, who wished to proclaim their independence from Mexico. By the end of 1845, having broken diplomatic ties with the United States over Texas and having grown alarmed by American actions in California, the Mexican government warily anticipated the next move. It did not have long to wait.

WAR WITH MEXICO, 1846–1848

Expansionistic fervor propelled the United States to war against Mexico in 1846. The United States had long argued that the Rio Grande was the border between Mexico and the United States, and at the end of the Texas war for independence Santa Anna had been pressured to agree. Mexico, however, refused to be bound by Santa Anna’s promises and insisted the border lay farther north, at the Nueces River ( Figure 11.14 ). To set it at the Rio Grande would, in effect, allow the United States to control land it had never occupied. In Mexico’s eyes, therefore, President Polk violated its sovereign territory when he ordered U.S. troops into the disputed lands in 1846. From the Mexican perspective, it appeared the United States had invaded their nation.

In January 1846, the U.S. force that was ordered to the banks of the Rio Grande to build a fort on the “American” side encountered a Mexican cavalry unit on patrol. Shots rang out, and sixteen U.S. soldiers were killed or wounded. Angrily declaring that Mexico “has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil,” President Polk demanded the United States declare war on Mexico. On May 12, Congress obliged.

The small but vocal antislavery faction decried the decision to go to war, arguing that Polk had deliberately provoked hostilities so the United States could annex more slave territory. Illinois representative Abraham Lincoln and other members of Congress issued the “Spot Resolutions” in which they demanded to know the precise spot on U.S. soil where American blood had been spilled. Many Whigs also denounced the war. Democrats, however, supported Polk’s decision, and volunteers for the army came forward in droves from every part of the country except New England, the seat of abolitionist activity. Enthusiasm for the war was aided by the widely held belief that Mexico was a weak, impoverished country and that the Mexican people, perceived as ignorant, lazy, and controlled by a corrupt Roman Catholic clergy, would be easy to defeat. ( Figure 11.15 ).

U.S. military strategy had three main objectives: 1) Take control of northern Mexico, including New Mexico; 2) seize California; and 3) capture Mexico City. General Zachary Taylor and his Army of the Center were assigned to accomplish the first goal, and with superior weapons they soon captured the Mexican city of Monterrey. Taylor quickly became a hero in the eyes of the American people, and Polk appointed him commander of all U.S. forces.

General Stephen Watts Kearny, commander of the Army of the West, accepted the surrender of Santa Fe, New Mexico, and moved on to take control of California, leaving Colonel Sterling Price in command. Despite Kearny’s assurances that New Mexicans need not fear for their lives or their property, the region’s residents rose in revolt in January 1847 in an effort to drive the Americans away. Although Price managed to put an end to the rebellion, tensions remained high.

Kearny, meanwhile, arrived in California to find it already in American hands through the joint efforts of California settlers, U.S. naval commander John D. Sloat, and John C. Fremont, a former army captain and son-in-law of Missouri senator Thomas Benton. Sloat, at anchor off the coast of Mazatlan, learned that war had begun and quickly set sail for California. He seized the town of Monterey in July 1846, less than a month after a group of American settlers led by William B. Ide had taken control of Sonoma and declared California a republic. A week after the fall of Monterey, the navy took San Francisco with no resistance. Although some Californios staged a short-lived rebellion in September 1846, many others submitted to the U.S. takeover. Thus Kearny had little to do other than take command of California as its governor.

Leading the Army of the South was General Winfield Scott. Both Taylor and Scott were potential competitors for the presidency, and believing—correctly—that whoever seized Mexico City would become a hero, Polk assigned Scott the campaign to avoid elevating the more popular Taylor, who was affectionately known as “Old Rough and Ready.”

Scott captured Veracruz in March 1847, and moving in a northwesterly direction from there (much as Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés had done in 1519), he slowly closed in on the capital. Every step of the way was a hard-fought victory, however, and Mexican soldiers and civilians both fought bravely to save their land from the American invaders. Mexico City’s defenders, including young military cadets, fought to the end. According to legend, cadet Juan Escutia’s last act was to save the Mexican flag, and he leapt from the city’s walls with it wrapped around his body. On September 14, 1847, Scott entered Mexico City’s central plaza; the city had fallen ( Figure 11.16 ). While Polk and other expansionists called for “all Mexico,” the Mexican government and the United States negotiated for peace in 1848, resulting in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed in February 1848, was a triumph for American expansion under which Mexico ceded nearly half its land to the United States. The Mexican Cession , as the conquest of land west of the Rio Grande was called, included the current states of California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, and portions of Colorado and Wyoming. Mexico also recognized the Rio Grande as the border with the United States. The United States promised to grant Mexican citizens in the ceded territory U.S. citizenship in the future when the territories they were living in became states, and promised to recognize the Spanish land grants to the Pueblos in New Mexico. In exchange, the United States agreed to assume $3.35 million worth of Mexican debts owed to U.S. citizens, paid Mexico $15 million for the loss of its land, and promised to guard the residents of the Mexican Cession from Native American raids.

As extensive as the Mexican Cession was, some argued the United States should not be satisfied until it had taken all of Mexico. Many who were opposed to this idea were southerners who, while desiring the annexation of more slave territory, did not want to make Mexico’s large mestizo (people of mixed Native American and European ancestry) population part of the United States. Others did not want to absorb a large group of Roman Catholics. These expansionists could not accept the idea of new U.S. territory filled with mixed-race, Catholic populations.

Click and Explore

Explore the U.S.-Mexican War at PBS to read about life in the Mexican and U.S. armies during the war and to learn more about the various battles.

CALIFORNIA AND THE GOLD RUSH

The United States had no way of knowing that part of the land about to be ceded by Mexico had just become far more valuable than anyone could have imagined. On January 24, 1848, James Marshall discovered gold in the millrace of the sawmill he had built with his partner John Sutter on the south fork of California’s American River . Word quickly spread, and within a few weeks all of Sutter’s employees had left to search for gold. When the news reached San Francisco, most of its inhabitants abandoned the town and headed for the American River. By the end of the year, thousands of California’s residents had gone north to the gold fields with visions of wealth dancing in their heads, and in 1849 thousands of people from around the world followed them ( Figure 11.17 ). The Gold Rush had begun.

The fantasy of instant wealth induced a mass exodus to California. Settlers in Oregon and Utah rushed to the American River. Easterners sailed around the southern tip of South America or to Panama’s Atlantic coast, where they crossed the Isthmus of Panama to the Pacific and booked ship’s passage for San Francisco. As California-bound vessels stopped in South American ports to take on food and fresh water, hundreds of Peruvians and Chileans streamed aboard. Easterners who could not afford to sail to California crossed the continent on foot, on horseback, or in wagons. Others journeyed from as far away as Hawaii and Europe. Chinese people came as well, adding to the polyglot population in the California boomtowns ( Figure 11.18 ).

Once in California, gathered in camps with names like Drunkard’s Bar, Angel’s Camp, Gouge Eye, and Whiskeytown, the “ forty-niners ” did not find wealth so easy to come by as they had first imagined. Although some were able to find gold by panning for it or shoveling soil from river bottoms into sieve-like contraptions called rockers, most did not. The placer gold, the gold that had been washed down the mountains into streams and rivers, was quickly exhausted, and what remained was deep below ground. Independent miners were supplanted by companies that could afford not only to purchase hydraulic mining technology but also to hire laborers to work the hills. The frustration of many a miner was expressed in the words of Sullivan Osborne. In 1857, Osborne wrote that he had arrived in California “full of high hopes and bright anticipations of the future” only to find his dreams “have long since perished.” Although $550 million worth of gold was found in California between 1849 and 1850, very little of it went to individuals.

Observers in the gold fields also reported abuse of Native Americans by miners. Some miners forced Native Americans to work their claims for them; others drove them off their lands, stole from them, and even murdered them as part of a systemic campaign of extermination. Some scholars view the resulting loss of Native American life as a clear example of genocide in the United States. Foreigners were generally disliked, especially those from South America. The most despised, however, were the thousands of Chinese migrants. Eager to earn money to send to their families in Hong Kong and southern China, they quickly earned a reputation as frugal men and hard workers who routinely took over diggings others had abandoned as worthless and worked them until every scrap of gold had been found. Many American miners, often spendthrifts, resented their presence and discriminated against them, believing the Chinese, who represented about 8 percent of the nearly 300,000 who arrived, were depriving them of the opportunity to make a living.

Visit The Chinese in California to learn more about the experience of Chinese migrants who came to California in the Gold Rush era.

In 1850, California imposed a tax on foreign miners, and in 1858 it prohibited all immigration from China. Those Chinese who remained in the face of the growing hostility were often beaten and killed, and some Westerners made a sport of cutting off Chinese men’s queues, the long braids of hair worn down their backs ( Figure 11.19 ). In 1882, Congress took up the power to restrict immigration by banning the further immigration of Chinese.

As people flocked to California in 1849, the population of the new territory swelled from a few thousand to about 100,000. The new arrivals quickly organized themselves into communities, and the trappings of “civilized” life—stores, saloons, libraries, stage lines, and fraternal lodges—began to appear. Newspapers were established, and musicians, singers, and acting companies arrived to entertain the gold seekers. The epitome of these Gold Rush boomtowns was San Francisco, which counted only a few hundred residents in 1846 but by 1850 had reached a population of thirty-four thousand ( Figure 11.20 ). So quickly did the territory grow that by 1850 California was ready to enter the Union as a state. When it sought admission, however, the issue of slavery expansion and sectional tensions emerged once again.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: P. Scott Corbett, Volker Janssen, John M. Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Sylvie Waskiewicz, Paul Vickery

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: U.S. History

- Publication date: Dec 30, 2014

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/11-4-the-mexican-american-war-1846-1848

© Jan 11, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

AP® US History

The ultimate guide to the 2015 ap® us history leq.

- The Albert Team

- Last Updated On: March 1, 2022

Only at the very end of the AP® U.S. History exam do you reach the Long Essay Question (LEQ). As a result, the LEQ is a challenge for even the most prepared test-taker. By this point in the exam, you are mentally exhausted, your hand is tired from writing all the other free response questions, and you just want to go home. That is what makes it so important that you practice for the exam so that even when you’re worn out, you’ll still be able to get the full six points on the AP® U.S. History LEQ.

In this post, we will help you prepare for this part of the test by walking through how the LEQ is scored, with specific examples from the 2015 U.S. History LEQ. By the end of the post, we hope you will be more confident in your ability to succeed on this year’s LEQ. So, let’s get started! Before we get into the specifics of the 2015 questions, though, let us review the overall format of the LEQ in the AP® U.S. History exam.

Format of the AP® US History LEQ

For the 2016 test, the CollegeBoard implemented a new format and rubric for grading the Free Response section of the AP® U.S. History Exam (see here ). Here we will focus on the revised format and rubric, addressing how the 2015 LEQ questions would have been scored under the new system and how you can succeed on this year’s LEQ. Be careful, though, when using resources from before 2016 that focus on the old AP® U.S. History exam format.

The LEQ occurs in the last half of the second section of the exam. It is the final part the exam and lasts for a total of 35 minutes. You will be asked to pick one of two questions to answer, and your response will count for a total of 15% of the overall exam score (see here ). Ideally, you should probably spend about five minutes outlining and the remaining thirty minutes writing the actual response.

The CollegeBoard grades you based on four general categories (with points indicated in parentheses), for a total of six points overall:

- Argument Development Using Targeted Historical Thinking Skill (2)

- Argument Development Using Evidence (2)

- Synthesis (1)

Note that you earn each point in the rubric independently and you will need to show unique evidence for each point (see here ). Thus, you can’t get both a Thesis and Argument Development point from the same sentence.

For the remainder of the piece, let us dive deeper into what each one of these point categories mean and how you can be sure to get all of the points for each one. We will use the 2015 questions and student responses as our examples. Let’s briefly look at the questions and then we will address what students did well and what they did poorly in answering the questions in 2015.

The 2015 LEQ Questions

For the 2015 AP® U.S. History exam, the CollegeBoard asked students to respond to either of the following two LEQs (see here ):

“Evaluate the extent to which the Seven Years’ War (French and Indian War, 1754-1763) marked a turning point in American relations with Great Britain.

In the development of your argument, analyze what changed and what stayed the same from the period before the war to the period after it. (Historical thinking skill: Periodization)”

“Evaluate the extent to which the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) marked a turning point in the debate over slavery in the United States.

The 4 Keys to LEQ Success

The key to LEQ success is to follow the rubric closely. The CollegeBoard looks for concrete evidence that you have completed each element of the rubric. If you have them, you’ll earn points. If you don’t, you will not. There is no partial credit on the AP® exam. Let’s take a look at the general rubric categories you need to touch upon to earn credit on the AP® U.S. History LEQ.

1. Write a Strong Thesis

For the first point in the rubric, the CollegeBoard demands a strong thesis: a historically defensible claim or argument that addresses all parts of the question (see here ). Your thesis should be a relatively easy point for you to achieve because your entire essay depends on having an argument you wish to make—a stand you take on the question. It is simply a matter of stating that overarching argument clearly, either in the introduction or the conclusion. Let us take a look at what made a successful LEQ thesis statement for students taking the 2015 AP® U.S. History exam.

For the first LEQ question about the French and Indian War, you must address the entire question: evaluating the extent to which the Seven Years’ War marked a turning point in American relations with Great Britain. Thus, if you choose to answer this one, you must make a historically defensible claim about the period. For instance, one student argues (see here ):

“The French and Indian War marked a major turning point in American relations with Great Britain, with changes such as increased British control and anti-British sentiment in the colonies, but also continuities such as loyalty to Britain that remained largely untouched by the war”.

Note that the student provides specific historical examples of things that changed with the French and Indian War (that they will follow up on in their essay with evidence) and clearly states their argument that the war marked a major turning point in American relations with Great Britain. A good example of a thesis from the second 2015 LEQ option might be as follows (see here ):

“The Mexican-American War marked a huge turning point in the debate over slavery because it brought to light the controversy of territorial self- determination and asked the question that would define America on a fundamental level: is this country one of slavery or one of freedom?”

This student argues that the Mexican-American war was a turning point and also specifically discusses its relationship to slavery, which they will address for the remainder of the essay. Note, however, that one answer is not necessarily the only answer. For instance, this student earned a thesis point for arguing that the war was not a turning point in the debate over slavery (see here ):

“The Mexican-American War was not a significant turning point in the debate over slavery because sectional divisions over the Mexican Cession did not increase until after the Compromise of 1850, a much more significant turning point.”

You will want to make sure that you can support your thesis statement to get the remaining points for the LEQ, but there is a bit of flexibility in how you can get the “Thesis” point of the rubric.

One way not to get “Thesis” credit on the U.S. History LEQ is to provide only a vague restatement of the question. For instance, this student’s thesis for the Seven Years’ War prompt fails to fully address the question (see here ):

“The Seven Years’ War was a major event in the world’s history, and it played an important role in shaping many nations.”

While the student does make an assertion, they do not evaluate the extent to which the war was a turning point in American relations with Great Britain, nor do they link the war to changes in relations with Great Britain. By not addressing the entirety of the question, the student did not receive credit for the “Thesis” portion of the grading rubric. Similarly, this student address only part of the second LEQ prompt about the Mexican-American War (see here ):

“The Mexican-American War marked a turning point in the debate over slavery in the U.S.”

To receive credit for this thesis, the student should have responded to the entire question, specifically evaluating the extent to which the war was a turning point. If your reader couldn’t read anything from your essay but your thesis, they should still be able to capture your entire argument from the thesis statement alone. When you practice writing theses, be sure to look at them and ask yourself whether or not you can do this: does your thesis completely address the question? If so, you’re ready to further develop your thesis argument with your historical thinking skills and specific historical evidence.

2. Apply Historical Thinking Skills

You will notice at the bottom of each LEQ option, the CollegeBoard prints a “Targeted Historical Thinking Skill”. For the 2015 exam, both of these historical thinking skills were “Periodization,” meaning the graders want you to describe and explain the extent to which the historical development specified in the prompt was different from and similar to developments that preceded and followed it (see here ). Specifically, you will receive one point for successfully describing this period change and a separate point for explaining the extent to which the historical development was similar to or different from developments that preceded and followed it.

Other examples of Historical Thinking Skills you might see on this year’s exam include Causation, Comparison, and Change and Continuity over Time (see here ). For each one of these, you will also be asked to describe the elements involved the causation, comparison, or change/continuity for one point and then explain how they played a role in causation, comparison, or change/continuity.

In the 2015 exam, both questions were “Periodization” questions, however, so let us get to the bottom of how “Periodization” questions are scored:

Your first point for using the Targeted Historical Thinking skill demands that you describe the ways in which the historical development in the prompt differed from or was similar to developments that preceded and followed it. One student writing on the French and Indian War, for instance, focused on similarities between the periods before and after the war as a means of developing their overall thesis that the war was not a turning point in American relations with Great Britain (see here ):

“Both before and after the war, officials attempted to place taxes on colonial goods to finance the empire.”

For this statement, the student earned a point for describing a similarity that carried on before and after the war in support of their thesis. Another student working on the second prompt about the Mexican-American War successfully emphasized the differences between pre- and post-war periods (see here ):

“The Mexican War did exacerbate sectionalism significantly. Before the war, the debate over the expansion of slavery and the balance of free and slave states had been somewhat settled by the Missouri Compromise. However, in the Treaty of Guadalupe – Hidalgo, the U.S. was granted vast new lands, including California and New Mexico. Debate immediately ensued over the state of slavery in the new lands.”

Once you have earned a point for either describing differences and similarities between periods before and after the time frame described in the prompt, you must explain the extent of these differences and similarities for the second point. For instance, differences or similarities that are limited to a particular city or medium have a very different pragmatic impact than do those that occur across the country in a variety of mediums. For instance, one student explains the extent of discontent before and after the French and Indian war, as follows (see here ):

“Discontent became a major change in Anglo-American relations with one another as protest grew to British involvement in American affairs and duties. Before the war, Americans were okay with some taxes and controlled trade restrictions, but the sudden and seemingly illegal tax actions forced protests and traitorous talks, none of which had been prominent before the war.”

The student goes beyond simply describing differences between periods (as required for the first point) and addresses the extent to which they occur (via protests and traitorous talks, for instance). Another student (who had already addressed the level of debate before the war), explains the differences after the Mexican-American War in the second prompt as (see here ):

“After the Mexican- American War, the debate became over what to do with the newly acquired territory and ultimately led to the creation of new parties. … Though the United States was unwilling to admit it, the political aspect of the country was turning into one all about slavery. The demographic of political parties changed and foreshadowed the civil war.”

This student addresses the extent of differences in the demographic composition of the political parties themselves. The key is to tie in an explanation of this extent to a description of the differences and similarities between previous and later periods. If you provide both a description and an explanation of the extent to which these differences and similarities were true, you will receive two points for this section of the rubric.

If on the other hand, you are unable to describe and explain the differences between events before and after the prompt’s period of interest, you will not receive the two points for this section of the rubric. For instance, this student confused the period under question (see here ):

“The U.S. and Great Britain had been on bad terms ever since the American Revolution.”

Since the American Revolution occurred after the French and Indian War, this cannot be an adequate description of the period before the war. Thus, they would not receive a point for their description. Even if you have a factually correct description, however, you may not receive a point if that description is off-topic. For instance, this student’s response to the Mexican-American War prompt does not tie directly into the slavery debate—an essential part of the question (see here ):

“After the Mexican-American War, U.S. gained land in the southwest. Because this would upset the balance of slave and free states too much, the government decided to implement popular sovereignty.”

While the student mentions slavery, they do not complete their thought on why (or if) this relates to the slavery debate itself. As such, they did not earn a point for their description.

Similarly, you will not receive the second point for your explanation of the extent of differences and similarities if you provide only a vague statement or do not clearly tie your writing in to answer the question provided in the prompt. For instance, this student does not move beyond the description of differences phase, providing only a vague statement about the extent (see here ):

“When the war began, colonists did take up arms to assist the British and protect their land, but it wasn’t until the war ended that relations began to change between the colonies and the motherland.”

Likewise, this student writing the from the Mexican-American war prompt provides only a vague description of the differences between periods, without clearly addressing the extent to which the difference was true (see here ):

“When the war ended, the acquisition of new land led to debates over the status of slavery in those territories.”

The key for this point is to be clear. For a periodization question like the ones in 2015, you want to make sure your graders know that you can effectively describe the periods before and after the period in question. Once you have described the periods, then you want to be able to explain the extent to which your description holds. If you do both of these things, you will receive two points for the section.

3. Support Your Argument with Specific Evidence

Up to this point, we have covered three out of five points you can earn through the LEQ rubric. You earn an additional two points by developing your argument by “Using Evidence”. On the exam, you should be able to provide specific, relevant historical examples that address the topic of the question (for one point) and (for a second point) support or substantiate your thesis (see here ).

Some acceptable evidential references that relate to the Seven Years’ War topic might be, for instance (see here ):

- British debt from the Seven Years’ War

- Colonial attitudes toward autonomy before the war

- Similar intellectual and religious attitudes between the colonies and Britain before the war

- Imperial policies in the wake of the Seven Years’ War

- Colonial resentments over treatment of colonial forces by British regulars

- British efforts to pacify and negotiate with American Indians

- Albany Plan of Union

Likewise, if you chose the Mexican-American War LEQ, you might choose to use some of the following acceptable evidence (see the complete list of acceptable evidence here ):

- Manifest Destiny

- Missouri Compromise (1820)

- Increasing fear of slave power

- William Lloyd Garrison, The Liberator (1830)

- Frederick Douglass

- Annexation of Texas (1845)

- Opposition to Mexican–American War among northern Whigs

- Abraham Lincoln’s Spot Resolutions (1846)

- Wilmot Proviso

The key is that you provide some evidence that is relevant to the topic at hand. As long as you do, you will earn a point for this first part of the “Using Evidence” portion of the rubric. This point should be a relatively easy one for you to get if you review your course notes before the exam. To earn this first evidence point, you do not even need to have a stated thesis or a relevant argument—only reference to a relevant piece of historical information (see here ). So, even if you know nothing about the question but a single relevant fact, you will be able to get at least one point for it.

To receive the second point in the “Using Evidence” section of the rubric, however, you need to provide evidence that substantiates your thesis or a related argument. For instance, the CollegeBoards states that acceptable evidence for arguing that the Seven Years’ War was less important as a turning point in different areas might include (see here ):

- The attitudes of everyday colonists

- Trans-Atlantic exchanges throughout the period

- Longstanding trans-Atlantic belief systems including republicanism, natural rights, the Enlightenment, and the Great Awakening

- Unchanged labor systems, including slavery

- The Zenger trial or other events illustrating a growth of distinct colonial identity well before the war

- Previous British policies of mercantilism.

On the other hand, for the same question, evidence that could be used to argue the Seven Years’ War was a major turning point in different areas might include (see here ):

- Taxation and efforts of Britain to assert greater control over colonial affairs

- The fact that British troops remained in the American colonies, there was a standing army, and the Quartering Act of 1765

- The passage of the Proclamation of 1763 to prevent movement of settlers across the Appalachians

- The passage of the Sugar Act (Revenue Act)

For each of these pieces of evidence, you need to make specific reference back to your thesis or relevant argument, demonstrating how this piece of evidence develops the overall argument of your essay to answer the exam prompt.

In the same way, examples of acceptable evidence that could be used to argue the Mexican–American War was not a turning point might include (see here ):

- Ongoing debates over slavery that continued before and after the war with William Lloyd Garrison, as well as The Liberator (1830), and the passage of the Gag Rule before the war

- Prior expansion of slavery into the Texas territories and debates over this expansion, including debates over Texas annexation

- Possibly more significant turning points, such as The Compromise of 1850 or the Kansas–Nebraska Act.

In contrast, evidence that could be used to argue the Mexican–American War was, in fact, a turning point might include (see here ):

- The increased debate over “free soil” and expansion of slavery

- The debates surrounding the Wilmot Proviso

- The need for addressing the influx of new territories and the effect that had on increasing sectional debates over slavery

- The changes to the political party system, including the death of the Whigs and the rise of the Republican Party, much of it centered on issues of expansion of slavery into the territories acquired by through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

If you successfully use a piece of evidence like those listed to substantiate your thesis, you will receive a point for the “Using Evidence” section of the LEQ. The key point here is to make sure you support your arguments with evidence. The CollegeBoard does not want you to be tossing around statements without providing clear evidence to support them.

The first point in the “Using Evidence” section gives you a lot of leeway regarding how you earn it. You simply need to mention a relevant piece of evidence to the prompt and you can earn points for your response. However, even if you provide a piece of evidence, you will not necessarily get points for it if it is not relevant to the question or true. For instance, this student confuses the chronology of events when trying to answer the Seven Years’ War LEQ (see here ):

“Some examples of the harsher rules and taxes that were enacted after the war were the Navigation Acts …”

The Navigation Acts were first enacted long before the start of the Seven Years’ War. As a result, even though they the acts did exist, the student did not receive a point because they incorrectly identified how the facts relate to the prompt.

Besides providing chronologically incorrect evidence, however, you can also lose the first point in the “Using Evidence” section by failing to connect it to all aspects of the question. For instance, a student writing about the Mexican-American War failed to clearly connect their evidence to the debate over slavery (see here ):

“The Missouri Compromise was an act that banned slavery in states above a certain parallel. The Kansas-Nebraska Act allowed for popular sovereignty in those new states west of the Mississippi.”

You earn a second point in the “Using Evidence” section of the rubric by substantiating your thesis or relevant argument with evidence. However, if you do not fully explain how the evidence supports your thesis, you will not receive credit for your answer. For instance, this student provides evidence, but does not explain how their evidence supports the argument that the Seven Years’ War was a turning point in American relations with Great Britain (see here ):

“The Seven Years’ War marks a turning point because the colonists refused to agree to British demands.”

The student needs to address more fully how and why colonists’ refusal marks a change from previous periods for this evidence to constitute any substantiation. For this point, the CollegeBoard wants you to engage with the evidence and not just list it out in a rote, memorized fashion. An additional example of unacceptable evidence to substantiate a thesis or relevant argument from a student who chose to answer the Mexican-American War LEQ is as follows (see here ):

“The Compromise of 1850 was drafted that made more of the newly acquired states free, and to appease the South it created the fugitive slave law, which returned ‘escaped’ slave to their owners, but this was abused since many slaves captured and returned were free.”

While this example features a more detailed example than the last one, the student still does not explain how their evidence supports the argument that the war was or was not a turning point in the slavery debate. To earn the second point in the “Using Evidence” portion of the grading rubric, you must use the evidence in service of your argument. In other words, you need to clearly explain how it fits into the larger argument of your thesis.

4. Synthesize Your Argument with Another Historical Development or Course Theme

In the previous sections, we have covered five of the six total points you can earn on the U.S. History LEQ . The final point you can earn is the “Synthesis” point. To earn this final point, the CollegeBoard wants you to extend your argument by explaining a connection between the argument and a development in a different historical period, geographic area, or historical theme (see here ). To get the point, you need to not just mention, but to explain why there is a connection between your argument and an outside theme or development. If you do so, you will earn the final point for the LEQ.

One student, for instance, tied together the results of the French and Indian War with those of the later French Revolution (see here ):

“The French and Indian War’s results were similar to what took place in the French Revolution later on, in that debt from the war helped cause colonial independence from Great Britain, while the debt from involvement in the American Revolution helped inspire the French Revolution.”

They used a completely different period and context to build on their existing argument for why the French and Indian War was a turning point for Americans. As a result, this excerpt earned a point for “Synthesis.”

Similarly, another student compared changing attitudes towards slavery during the Mexican-American War to President Johnson’s later War on Poverty and its effects on the Civil Rights Movement (see here ):

“The increased tensions over the debate over slavery that resulted from the Mexican-American War continued to show themselves in racial tensions in the Civil War and beyond. These tensions boiled up again in the 1960’s as Southerners fought the expansion of rights to African Americans. While the Mexican-American War amounted to a great turning point in the debate over slavery, Johnson’s War on Poverty amounted to a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement.”

Note, however, that you do not need to compare your argument to another historical development to earn the “Synthesis” point. You can also receive the point by addressing how your question might be interpreted from an alternative historical theme. For instance, one student spent their entire essay analyzing the Seven Years’ War from the perspective of political policy and attitude, but compared how an economic perspective might shed light on the question (see here ):

“While the Seven Years’ War changed political policies and attitudes, it also affected economic and commercial ties, as British taxation began to enforce mercantilist policies.”

Likewise, in a political essay about the Mexican-American War, another student discusses other social factors that also played a role in the differences the war created (see here ):

In an otherwise political essay: “The Mexican War created political imbalance because the balance between slave and free states from the Missouri Compromise ended. This loss of power in Congress resulted in an increase in the slave owners’ oppression of their slaves. They were afraid of also losing control of the social class structure seen in the South and the risk of losing their social and economic status. So the political crisis caused by the Mexican War also had a social element as well.”

The key is that all of these successful “Synthesis” points draw upon something external to their central argument or period of inquiry to extend their argument and demonstrate how it fits into the bigger scheme of history.

On the other hand, if you do not explain the connection between two contexts as they relate to the question, you will not receive a point. For instance, this student makes comparisons to the Seven Years’ War but does not explain how each of these conflicts served to foster revolutions in the external contexts (see here ):

“The anger caused by Britain’s strong handed actions left the land of the colonies fertile for the seeds of Revolution to grow in the same way they were in France, Haiti, and other soon to revolt countries of the time.”

To earn the “Synthesis” point, the student would need to expand more on how these other conflicts unfolded and how those processes correspond with the process of history in prompt’s period of interest more generally.

Similarly, another student compares the Mexican-American War to the Spanish-American War regarding land acquisition and imperialism, but does not address the central issue of the exam prompt—slavery (see here ):

“This era is very similar to that of the very late 1800’s in which the U.S. instigated a war with Spain to attain land, as done in Mexico during this period.”

It is not enough to simply state a similarity between the periods. The comparison must be relevant to the overall thesis of your essay and the LEQ itself.

Regarding thematic comparisons, the CollegeBoard emphasizes that students might similarly fail to adequately connect the alternate theme to the primary one used in their argument (see here ). However, one of the main problems for students attempting thematic comparisons is that they fail to address the thesis from an alternative theme at all. For instance, this student spent the majority of the essay discussing political reasons that the French and Indian War was a turning point and said (see here ):

“The war caused changes to political beliefs for both colonists and British officials.”

While this statement may be true, it does not represent an alternative theme from the dominant theme they used throughout their essay. Therefore, the student could not receive points for bringing up the “political” historical theme. They would need to bring up related Economic or Social thematic issues for instance.

Moving Forward

Now that you have seen examples of 2015 students who have succeeded on the AP® U.S. History LEQ and those who have not, it’s time for you try your hand at practice LEQs.

Try and write an answer to both of the questions described in this post with a 35-minute timer. Then, check and see how well you did at earning each one of the six points described in this post.

If you practice enough, writing LEQs will become automatic, and however tired you are by the time you reach the LEQ section of the exam, you will at least have confidence that you can succeed.

Looking for AP® US History practice?

Kickstart your AP® US History prep with Albert. Start your AP® exam prep today .

Interested in a school license?

Popular posts.

AP® Score Calculators

Simulate how different MCQ and FRQ scores translate into AP® scores

AP® Review Guides

The ultimate review guides for AP® subjects to help you plan and structure your prep.

Core Subject Review Guides

Review the most important topics in Physics and Algebra 1 .

SAT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall SAT® score

ACT® Score Calculator

See how scores on each section impacts your overall ACT® score

Grammar Review Hub

Comprehensive review of grammar skills

AP® Posters

Download updated posters summarizing the main topics and structure for each AP® exam.

Interested in a school license?

Bring Albert to your school and empower all teachers with the world's best question bank for: ➜ SAT® & ACT® ➜ AP® ➜ ELA, Math, Science, & Social Studies aligned to state standards ➜ State assessments Options for teachers, schools, and districts.

UTC Scholar

- UTC Scholar Home

- UTC Library

Preserving and Sharing UTC's Knowledge

- < Previous

Home > Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications > Honors Theses > 443

Honors Theses

On the causation of the mexican-american war.

Emery Benson , University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Follow

Project Director

Johnson, Mark

Department Examiner

Thompson, Michael

Dept. of History

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Place of Publication

Chattanooga (Tenn.)

In 1844, Whig, former President, and then-Representative John Quincy Adams reflected on President John Tyler’s bill to annex Texas, writing about his anxiety over “the degeneracy of my country… under the transcendent power of slavery and the slave-representation.” Adams celebrated the treaty’s failure later that year, praising the nation’s escape from “slave-tainted monarchy, and of extinguished freedom.” In 1847, in the midst of the Mexican-American War, Reverend John Dudley of Vermont gave a fiery sermon in which he excoriated “the two leading sins of this nation, SLAVERY AND WAR.” Reverend Dudley continued, claiming “that the present war has its origin and justification in the slave-holding interest in these United States.” In early 1848, right before the war’s conclusion, former enslaved man and intellectual Frederick Douglass gave a speech calling the war nothing less than a “slaveholding crusade.” All three of these men, and many more people across the United States, were united in their denunciation of the Mexican-American War as one instigated by the slaveholding interests of the country in order to expand slavery westward and ensure that the institution continued to enjoy economic and political benefit. This accusation, however, lacks consensus, as others such as President James K. Polk, Ulysses S. Grant, and Mississippi Senator Robert J. Walker argued that the war’s causation lay in such varied reasons as Mexican debt owed to the United States and its citizens, a simple desire for more land to settle, or a belief that if the United States did not seize valuable land from the weak Mexican state, the British would. Therein lies the question this thesis will answer: Did slaveholders and slavery’s advocates instigate the Mexican-American War to benefit themselves, or is the role of slavery in uniting pro-war feelings overstated? If slavery’s role is overstated, what lies behind the United States’s decisions to annex Texas, inherit a border dispute, and provoke the Mexicans into war? To uncover whether slaveholding interests instigated the Mexican-American War, I will examine the leadup to the war, most notably the circumstances that led the United States to annex Texas, and how different people and groups perceived the choices being made in Washington and Mexico City. Then, the war itself and how a calcifying political establishment led to such incidents as the Wilmot Proviso, which thrust the debate over slavery’s connection to the war to the forefront. Finally, an examination of the war’s end and how victory was interpreted on both sides of the new border. I will describe the perspectives of the major political parties, Whigs and Democrats, from North and South, the servicemen who fought the war, and the civilians who saw, wrote, and argued about the war. Though I primarily explore American perspectives, some translated Mexican documents offer a broader understanding of the war that extends interpretations to the invaded as well as the invader.

B. A.; An honors thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts.

Mexican War, 1846-1848--Causes

Mexican-American; American war; Mexico; United States; Slavery; Foreign relations

United States History

Document Type

http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/

Recommended Citation

Benson, Emery, "On the causation of the Mexican-American War" (2023). Honors Theses. https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses/443

Since January 02, 2024

Included in

United States History Commons

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

- Submission Guidelines

- Submit Research

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

U.S. Women and the War

Biographies | Correspondence | Music & Poetry | Newspapers | Images | Maps

For American women as much as for American men, news of the outbreak of war with Mexico was greeted with a burst of patriotic enthusiasm. In many states, women formed committees that organized banquets, dances, and parades for newly created volunteer regiments. Many sewed flags and banners, quilts, and blankets for the men of their community who had enlisted and would soon be departing for Mexico.

Not all women, however, supported the war. In New England, the center for organized opposition to the conflict, female members of abolitionist societies that condemned the acquisition of any territory that would be used to expand the slave empire were particularly outspoken critics of the invasion of Mexico. Margaret Fuller, then living in Europe as a correspondent and editorialist for Horace Greeley's New York Tribune, became a scathing critic of President Polk , whom she held responsible for waging what she believed to be an unjust war to extend slavery.

A few women played active roles in support of the war. Jane McManus Storms Cazneau , a journalist for the New York Sun and the Democratic Review, became a strong proponent of Manifest Destiny, even advocated the acquisition of all of Mexico. She witnessed Winfield Scott 's capture of Vera Cruz in March 1847, becoming the first female war correspondent in U.S. history. Ann Chase , the Irish-born wife of the U.S. consul in Tampico, passed along critical secrets and information about Mexican troop movements. Perhaps the most famous woman to emerge during the war was Sarah Borginnis , who had accompanied her husband to Mexico as a laundress with the Missouri Seventh Infantry. When the war began she was working as a cook at Fort Texas, later renamed Fort Brown. During the bombardment of the fort her courage came to the attention of the press, who nicknamed her the "Heroine of Fort Brown." Later known as "the Great Western" she traveled with Taylor 's army as a nurse and cook, and participated in the Battle of Buena Vista.

The "Heroine of Fort Brown."

The Parlour Duets For Two Performers on One Piano : Arranged with fingering by J. C. Viereck in 6 Numbers : No. 1 Monterey, A Military Rondino

The warlike dead in mexico : poetry by mrs. balmanno music composed and dedicated (by special permission) to the hon. henry clay by miss augusta browne, notes of a military reconnoissance from fort leavenworth: a new mexican woman, incidents and sufferings in the mexican war : the heroine of fort brown, castle de perote, mexico, susan shelby magoffin, the field of monterey ballad affectionately dedicated to mrs. virginia q.s. (of virginia) by m. dix sullivan, no. 1. monterey, a military rondino [cover], the warlike dead in mexico / poetry by mrs. balmanno ; music composed and dedicated by special permission to the hon. henry clay by miss augusta browne., the soldier's return : a song for the people..

Speech on the Mexican-American War

- Commercial Republic

- Defense and War

- Federal Government

- Race and Equality

- Rights and Liberties

No study questions

The day is dark and gloomy, unsettled and uncertain, like the condition of our country, in regard to the unnatural war with Mexico. The public mind is agitated and anxious, and is filled with serious apprehensions as to its indefinite continuance, and especially as to the consequences which its termination may bring forth, menacing the harmony, if not the existence, of our Union.

It is under these circumstances, I present myself before you. No ordinary occasion would have drawn me from the retirement in which I live; but, whilst a single pulsation of the human heart remains, it should, if necessary, be dedicated to the service of one’s country. And I have hope that, although I am a private and humble citizen, an expression of the views and opinions I entertain, might form some little addition to the general stock of information, and afford a small assistance in delivering our country from the perils and dangers which surround it.

I have come here with no purpose to attempt to make a fine speech, or any ambitious oratorical display. I have brought with me no rhetorical bouquets to throw into this assemblage. In the circle of the year, autumn has come, and the season of flowers has passed away. In the progress of years, my spring time has gone by, and I too am in the autumn of life, and feel the frost of age. My desire and aim are to address you, earnestly, calmly, seriously and plainly, upon the grave and momentous subjects which have brought us together. And I am most solicitous that not a solitary word may fall from me, offensive to any party or person in the whole extent of the union.

War, pestilence, and famine, by the common consent of mankind, are the three greatest calamities which can befal our species; and war, as the most direful, justly stands foremost and in front. Pestilence and famine, no doubt for wise although inscrutable purposes, are inflictions of Providence, to which it is our duty, therefore, to bow with obedience, humble submission and resignation. Their duration is not long, and their ravages are limited. They bring, indeed, great affliction whilst they last, but society soon recovers from their effects. War is the voluntary work of our own hands, and whatever reproaches it may deserve should be directed to ourselves. When it breaks out, its duration is indefinite and unknown—its vicissitudes are hidden from our view. In the sacrifice of human life, and in the waste of human treasure, in its losses and in its burthens, it affects both belligerent nations; and its sad effects of mangled bodies, of death, and of desolation, endure long after its thunders are hushed in peace. War unhinges society, disturbs its peaceful and regular industry, and scatters poisonous seeds of disease and immorality, which continue to germinate and diffuse theirbaneful influence long after it has ceased. Dazzling by its glitter, pomp and pageantry, it begets a spirit of wild adventure and romantic enterprise, and often disqualifies those who embark in it, after their return fromthe bloody fields of battle, from engaging in the industrious and peaceful vocations of life.

We are informed by a statement which is apparently correct, that the number of our countrymen slain in this lamentable Mexican war, although it has yet been of only 18 months existence, is equal to one half of the whole of the American loss during the seven years war of the Revolution! And I venture to assert that the expenditure of treasure which it has occasioned, when it shall come to be fairly ascertained and footed up, will be found to be more than half of the pecuniary cost of the war of our independence. And this is the condition of the party whose arms have been every where and constantly victorious!

How did we unhappily get involved in this war? It was predicted as the consequence of the annexation of Texas to the United States. If we had not Texas, we should have no war. The people were told that if that event happened, war would ensue. They were told that the war between Texas and Mexico had not been terminated by a treaty of peace; that Mexico still claimed Texas as a revolted province: and that, if we received Texas in our Union, we took along with her, the war existing between her and Mexico. And the Minister of Mexico [Juan N. Almonte] formally announced to the Government at Washington, that his nation would consider the annexation of Texas to the United States as producing a state of war. But all this was denied by the partisans of annexation. They insisted we should have no war, and even imputed to those who foretold it, sinister motives for their groundless prediction.

But, notwithstanding a state of virtual war necessarily resulted from the fact of annexation of one of the belligerents to the United States, actual hostilities might have been probably averted by prudence, moderation and wise statesmanship. If General Taylor had been permitted to remain, where his own good sense prompted him to believe he ought to remain, at the point of Corpus Christi; and, if a negotiation had been opened with Mexico, in a true spirit of amity and conciliation, war possibly might have been prevented. But, instead of this pacific and moderate course, whilst Mr. Slidell was bending his way to Mexico with his diplomatic credentials, General Taylor was ordered to transport his cannon, and to plant them, in a warlike attitude, opposite to Matamoras, on the east bank of the Rio Bravo; within the very disputed territory, the adjustment of which was to be the object of Mr. Slidell’s mission. What else could have transpired but a conflict of arms?

Thus the war commenced, and the President after having produced it, appealed to Congress. A bill was proposed to raise 50,000 volunteers, and in order to commit all who should vote for it, a preamble was inserted falsely attributing the commencement of the war to the act of Mexico. I have no doubt of the patriotic motives of those who, after struggling to divest the bill of that flagrant error, found themselves constrained to vote for it. But I must say that no earthly consideration would have ever tempted or provoked me to vote for a bill, with a palpable falsehood stamped on its face. Almost idolizing truth, as I do, I never, never, could have voted for that bill.