80 Maus Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best maus topic ideas & essay examples, ⭐ interesting topics to write about maus, ✅ simple & easy maus essay titles, ❓ maus essay questions.

- Guilt in “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” by Art Spiegelman Maus, through the comic, explains the Holocaust through his father’s experience, and we see that it was not an easy place to come out because of the horrors and mistreatment in the concentration camps.

- Emotional and Ethical Appeal in Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” He writes Maus, a nonfictional book, to describe the horror that the Jews were subjected to during the Holocaust through the narration of his father. We will write a custom essay specifically for you by our professional experts 808 writers online Learn More

- Rhetorical Awareness in the First Chapters of “Maus” by Spiegelman Once again, adding this scene demonstrates Spiegelman’s awareness that most of his audience would not have a direct and personal connection to the Holocaust.

- A Survivor’s Tale: “Maus” by Spiegelman This desire to recall the good old days proves that the victims of the war prefer to remember the pleasant times.

- Maus: A Survivor’s Tale My Father Bleeds History Art Spiegelman magnificently links the past and the present graphically to narrate his father’s surviving the Holocaust and his relations with the father.

- Visual Narrative of Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” Secondly, as mentioned above, there are two timelines in the novel, the first of which takes place in the present relative to the author of the time, and the second is the memories of one […]

- Art Spiegelman’s Graphic Novel “Maus I: A Survivor’s Tale”: Author’s Understanding of the Holocaust Spiegelman uses mice to represent Jews because of the oppression they experienced while in Hitler’s concentration camps. The mistreatment the Jews experienced is similar to what mice experience in the presence of cats.

- “Maus” and “Maus II” Stories by Art Spiegelman The short stories Maus and Maus II by Art Spiegelman are the examples of the innovative, not traditional approach to the topic of the Holocaust.

- Armenian Genocide and Spiegelman’s “Maus” Novel Tracing the similarities between the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide is important to the discussion of Maus as a literary piece.

- “Maus: A Survivor’s Tale” a Novel by Art Spiegelman Intertwined throughout the story is the turbulent and pragmatic relationship between Art and his elderly father. This was the root of the overwrought relationship that existed between Vladek and his son because he held his […]

- Holocaust in “Maus” Graphic Novel by Art Spiegelman It is quite peculiar that Spiegelman uses only the black-and-white color perhaps, this is another means to emphasize the gloomy atmosphere of the Nazi invasion and the reign of the anti-Semite ideas.

- “The Dew Breaker” and “Maus” Stories Comparison Despite the seeming difference in the details of each of the seven stores, there is the invisible and almost intangible connection between the seven parts of the book.

- Nazi Regime in «Maus» by Art Spiegelman The author describes the life of his father Vladek Spiegelman before the Nazi occupation of Poland, during the Second World War, and the later influence of the Holocaust experiences on his personality.

- Jewish Experience in «Maus» by Art Spiegelman Published in 1991 and written by Art Spiegelman, the MAUS is a book that provides the account of the author’s effort of knowing his Jewish parents’ experience, following the Holocaust as well as their survival […]

- The Long Term Effects of Trauma and the Strange Behaviors of Vladek in “Maus” by Art Spiegelman

- Merging Past and Present in Art Spiegelman’s Complete “Maus” Tales

- Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” and the Afterimages of History

- Traumatic Experiences Change Lifestyles: “Maus” by Art Spiegelman

- “Maus” and the Commandant of Lubizec

- The Holocaust Survivor Testimonies in “Maus” by Art Spiegelman

- “Maus” and the Psychological Effects of the Holocaust

- The Life and Survival Story of Vladek Spiegelman in “Maus I” and “Maus II” by Art Spiegelman

- “Maus” and the Worlds of Reality and Fiction

- Art Spiegelman’s “Maus”: Graphic Art and the Holocaust

- Art Spiegelman’s “Maus”: Prisoner on the Hell

- Art Spiegelman’s Graphic Novel “Maus”: Holocaust and Its Impact on the Survivors and Their Children

- “Maus” and Traplines: Father-Son Relationships Testimonies

- “Maus” and the National Holocaust Museum: Comparing

- Comparison of the Graphic Novels “Maus,” “Persepolis,” “Fun Home,” and “Barefoot Gen”

- “Maus” and the Narrative of the Graphic Novel

- Understanding the Holocaust Through Art Spiegelman’s “Maus”

- Literary and Cinematic Works: “Maus” by Art Spiegelman

- “Maus”: Memory and What It Means

- Art Spiegelman’s “Maus”: Working Through the Trauma of the Holocaust

- Comparing the Similarities and Differences Between the Holocaust Survival Stories in “Maus” and “Night”

- “Maus” and Eden Robinson’s “Monkey Beach” Post Memory

- “Maus” Analysis: Losing Through Surviving

- The Concept of Guilt in the Novel “Maus”

- The Visual Writing Style Features in the Novel “Maus”

- Art Spiegelman’s “Maus”: Depictions of the Holocaust in Popular Art

- Nazi Propaganda and “Maus” by Art Spiegelman

- Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” and the Literary Canon

- The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Spiegelman’s “Maus”: Comparison

- Ethnic Notions, Bamboozled and “Maus”

- Character Analysis for “Maus” by Art Spiegelman

- Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” and Traditionally Comic Books

- The Metaphor and Symbolism in “Maus”

- Anthropomorphic Animals in Art Spiegelman’s Graphic Novel “Maus”

- The Conflict Between Father and Son in “Maus”

- “Maus” Through the Prism of Postmodernism

- Art Spiegelman: Biography, Artist and “Maus”

- “Maus”: Categories, Reproductions, and Interpretations

- Personal, Social, and Cultural Contexts Established by the Frame Story in “Maus”

- Post-modern Techniques in “Maus” by Art Spiegelman

- What Does Anja Spiegelman Feel About the Smuggling Idea in “Maus”?

- Does Artie Feel Guilty in “Maus”?

- What Did You Learn About Humanity From Reading “Maus” and Why?

- What Are the Long-Term Effects of Trauma and the Strange Behaviors of Vladek in “Maus”?

- Why Is “Maus” Black and White?

- Why Did Art Spiegelman Use Animals Instead of Humans in “Maus”?

- Why Is Anja Sent to a Sanitarium in “Maus”?

- What Is the Meaning of the Beard and Skullcap That Vladek’s Father Is Shown Earing in “Maus”?

- Why Would Anja Be Helping a Communist in “Maus”?

- How Is Perseverance Shown in “Maus”?

- Why Does the Tin Shop Foreman Yidl Dislike Vladek in “Maus”?

- What Is the Symbolism in “Maus”?

- Why Do the Germans Hang Nahum Cohn and His Son in “Maus”?

- What Do the Moths Represent in “Maus”?

- How Is Merging Past and Present in Art Spiegelman’s Complete “Maus” Tales?

- What Are the Major Themes in “Maus”?

- What Did the Pigs Represent in “Maus”?

- How Does Vladek’s Father Try to Keep Him Out of the Army in “Maus”?

- Why Is “Maus” Called Maus?

- What Age Is “Maus” Appropriate For?

- How Does Present-Day Vladek’s Personality Compare to His Past Self in “Maus”?

- How Did Vladek Change in “Maus”?

- How Is the Conflict Between Father and Son Showed In “Maus”?

- Why Does Vladek Choose Anja Over Lucia in “Maus”?

- How Is Survival a Theme in “Maus”?

- What Are the Psychological Effects of the Holocaust Described in “Maus”?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 22). 80 Maus Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/maus-essay-topics/

"80 Maus Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 22 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/maus-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '80 Maus Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 22 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "80 Maus Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." December 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/maus-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "80 Maus Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." December 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/maus-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "80 Maus Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." December 22, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/maus-essay-topics/.

- Allegory of the Cave Topics

- Night by Elie Wiesel Essay Topics

- Antisemitism Essay Titles

- Fascism Questions

- Holocaust Titles

- Judaism Ideas

- Nazism Topics

- Oppression Research Topics

- World History Topics

- Zionism Research Topics

- Auschwitz Research Topics

- Eugenics Questions

- Genocide Essay Titles

- Torture Essay Ideas

- Symbolism Titles

Summary of ‘ Maus by Art Spiegelman

This essay about Art Spiegelman’s “Maus” offers a nuanced exploration of its portrayal of the Holocaust, emphasizing themes of resilience, trauma, and intergenerational relationships. Through Spiegelman’s use of anthropomorphic imagery, the novel humanizes the experiences of its characters while shedding light on the predatory nature of oppression. Central to the narrative is the complex relationship between Art and his father, Vladek, whose experiences as a survivor shape their familial dynamic. The essay also delves into the broader implications of memory and storytelling, challenging readers to confront the subjective nature of historical representation. Ultimately, “Maus” serves as a powerful testament to the enduring legacy of trauma and the resilience of the human spirit.

How it works

Within the pages of Art Spiegelman’s graphic novel “Maus” lies a tapestry of narratives that unravel the complexities of human experience amidst the backdrop of one of history’s darkest chapters – the Holocaust. Through the lens of anthropomorphism, where Jews are depicted as mice and Nazis as cats, Spiegelman crafts a multi-dimensional narrative that transcends mere retelling, delving into the depths of trauma, resilience, and the enduring impact of historical memory.

The unique visual storytelling employed by Spiegelman serves as a conduit for readers to engage with the Holocaust in a manner that transcends traditional narrative forms.

By personifying characters as animals, the author not only humanizes their experiences but also underscores the predatory nature of oppression and persecution. Through this lens, readers are confronted with the stark realities of survival and the indomitable spirit that persisted in the face of unspeakable horror.

Central to the narrative of “Maus” is the intricate relationship between Art and his father, Vladek, whose experiences as a Holocaust survivor shape the contours of their familial dynamic. Through their interactions, Spiegelman navigates the complexities of intergenerational trauma, illuminating the tensions between remembrance and forgetting, silence and expression. The portrayal of Vladek as both hero and flawed individual serves as a testament to the complexities of survivorship, where resilience is often intertwined with profound emotional scars.

In addition to its exploration of personal histories, “Maus” invites readers to reflect on the broader implications of memory and representation in shaping our understanding of the past. Through Art’s struggle to reconcile his father’s fragmented recollections with the historical record, Spiegelman prompts us to confront the subjective nature of storytelling and the inherent challenges of bearing witness to history. In doing so, the novel compels us to interrogate our own roles as stewards of memory and the ethical responsibilities that accompany the act of remembrance.

In conclusion, “Maus” by Art Spiegelman stands as a testament to the enduring power of storytelling in illuminating the human condition. Through its innovative narrative structure and poignant characterizations, the novel transcends its historical context to offer profound insights into the universal themes of survival, resilience, and the enduring legacy of trauma. As we journey through the pages of “Maus,” we are reminded of the indomitable spirit that perseveres in the face of adversity and the imperative to bear witness to the stories of those who came before us.

Cite this page

Summary Of ' Maus By Art Spiegelman. (2024, Apr 14). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/summary-of-maus-by-art-spiegelman/

"Summary Of ' Maus By Art Spiegelman." PapersOwl.com , 14 Apr 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/summary-of-maus-by-art-spiegelman/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Summary Of ' Maus By Art Spiegelman . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/summary-of-maus-by-art-spiegelman/ [Accessed: 14 Apr. 2024]

"Summary Of ' Maus By Art Spiegelman." PapersOwl.com, Apr 14, 2024. Accessed April 14, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/summary-of-maus-by-art-spiegelman/

"Summary Of ' Maus By Art Spiegelman," PapersOwl.com , 14-Apr-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/summary-of-maus-by-art-spiegelman/. [Accessed: 14-Apr-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Summary Of ' Maus By Art Spiegelman . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/summary-of-maus-by-art-spiegelman/ [Accessed: 14-Apr-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

English Works

Maus: A student’s essay, written with my assistance

The Complete Maus shows that the Holocaust experience affects the next generation as much as it affects the people who lived through it. Do you agree?

In his comic story, Maus, Pulitzer prize winner Art Spiegelman writes about his parents’ experiences in Nazi Germany. Spiegelman uses various interview and graphic-style techniques to capture the horror of the Nazi “experiment” whereby up to 6 million Jews were killed in gas chambers in concentration camps. Whilst Vladek and Anja both survived, they were psychologically scarred. Throughout the interviews with his father, Vladek, and his father’s narrative recounts, Spiegelman reveals the extent of their trauma which inhibits family life and relationships. The emotional and psychological divide between Art and Vladek is further tarnished by the deaths of Richieu and Anja. The father’s development of a variety of obsessive neuroses also become another burden in the father-son relationship.

Throughout the graphic novel, Spiegelman depicts a variety of emotional and communication barriers, which he suggests may have originated from Vladek’s Holocaust experiences. Vladek constantly offers parental advice to Art that is often based on his experiences as a symbolic mouse in pinstriped pyjamas and yet this advice leads to, rather than, solves many of their interpersonal problems. Such emotional barriers, which appear to affect each of the men differently, are foregrounded in the ‘Prologue’. After Art was deserted and humiliated by his friends whilst rollerskating on the street, his father tells him unsympathetically and dismissively, “Friends? Your friends? If you lock them together in a room with no food for a week … then you could see what it is, friends!” Vladek continues to saw the piece of wood, suggesting that he is always fixing something, as he did during his war-time experiences. He doesn’t appear to be paying much attention to Art which reinforces his emotional indifference. This is a typical moment when Vladek views friendship through the lens of life-and-death actions, and he dismisses Art’s eight-year-old problems. In turn, he makes Art’s problems seem insignificant compared to his own. From Vladek’s perspective, his emotional detachment from his son, which could be a coping mechanism developed from his war experiences, alienates him from his son. From Spiegelman’s perspective, he does not find the psychological solace that he is searching.

Whilst Vladek appears indifferent and detached, Art appears to suffer from Vladek’s constant comparison between his father’s monumental, and his own insignificant, life experiences. This comparison reinforces the barriers between each and exacerbates the emotional distance. It is evident that Art agonises over these moments during his childhood, because later in Spiegelman’s typical question and answer style interview, he admits to his psychologist, Pavel, who is also a Czech Jew and a survivor of Auschwitz, that “mainly I remember arguing with him and being told that I couldn’t do anything as well as he could… No matter what I accomplished it doesn’t seem like much compared to surviving Auschwitz.” Owing to Vladek’s tendency to belittle Art’s experiences, Art constantly feels as though he will never impress his father and develops feelings of inferiority. IN his own way, Vladek appears to inflate the significance of his own experiences in a bid to overcompensate for the fact that for most of his life he was degraded by the Nazis. As Pavel says, “Maybe your father needed to show that he was always right — that he could always survive — because he felt guilty about surviving”. The symbolic depiction of the demoralised Jews as vulnerable and powerless mice that are tortured by the vicious cat captures Vladek’s sense of impotence and despair. From Vladek’s perspective, this sense of impotence is, inadvertently, displaced onto his son. From Art’s perspective, he ironically, feels belittled, much as the father was and neither can overcome their distance.

It is evident in Maus that Vladek is constantly haunted by a sense of survivor guilt. It is also apparent that the father transfers this guilt onto Art, which surfaces in both direct and indirect ways. As a consequence, this guilt exacerbates the psychological barriers between then and leads to displaced and thwarted emotions. As Pavel tells his patient, if Vladek survives, 6 million Jews were killed, and this has resulted in constant anxiety. In one comic caption, Pavel states, “Because he felt guilty about surviving … he took his guilt out on you, where it was safe…on the real survivor.” (p 204). Graphically, Art depicts Vladek’s guilt by using a palimpsest technique, which is a literal graphical bleeding from past to present, This technique reveals Vladek’s displaced anxiety. For example, in a panel, where the family is driving back from the supermarket after attempting to return the unfinished box of special K, Vladek recalls the deaths of the four girls who were scapegoated for their subversion. This frame shows the literal blend of time zones. In the frame, Art and Francoise are in the car listening to Vladek’s recount. In the same frame, there is an image of four sets of legs hanging from a tree which presumably belong to Anja’s four friends who “blew up a crematorium”. Spiegelman graphically suggests that Vladek is scarred by the horror of his past and it is this horror that leads to numerous psychological problems.

(In another depiction, four pairs of legs are also dangling from a rope. In this case, Nahum Cohn and his son, who traded goods without a coupon, hang from the scaffold. Vladek suggests that such assistance was critical to his survival and yet it led to the deaths of others. Spiegelman uses an eight-frame page consisting of a five-frame present-time overlay. In the above frame, the four mice, dressed in suits, “hanged there for one full week”. Vladek’s prominent caption refers to the tactics of intimidation used by the “cats” to scare the “mice” into submission. In the bottom frame, Spiegelman uses the image of legs hanging in mid air to give an impression that anyone who subverted the system would suffer a similar fate. In doing so, Spiegelman enhances the image of the dead Jews and the brutality of the cats that continues to haunt both father and son.)

Furthermore, Vladek’s guilt often surfaces in a variety of neurotic compulsive behaviours and these interfere with his ability to be a good father. Because of these behaviours, he cannot connect on an emotional level with his son. Vladek is neurotic about food, disease, death and profligacy. He compulsively organises his pills, seeks to save every penny, and fixes everything through his own abilities. Vladek refuses to hire anyone to fix household problems. Spiegelman suggests that his entrepreneurial skills were the reason he stayed alive in the labour camps. Vladek also believes that he survived because ‘I saved “Ever since Hitler I don’t like to throw out even a crumb”. In a humorous way, this reinforces the stereotype of the stingy Jew. Mala says,” it causes his physical pain to part with money”. In a revealing retort, Vladek adamantly states: “I cannot forget it” which sums up his attitude to most daily life occurrences. He simply cannot forget the stress of experiences such as staying in Mrs Motonowa’s cellar, sleeping with rats and living off candy for three days. They learned to be “happy even to have these conditions.” Whilst Spiegelman sets up the stereotypical miserly Jew for ridicule, there is a sense that readers can truly understand the basis of Vladek’s neuroses which are constantly displaced. Art believes that he must bear the brunt of these disorders which make it almost impossible for Art to have a normal and calm relationship with his father.

Spiegelman depicts many second generation holocaust survivors struggling with the agony of loss experienced by their traumatised parents. Many parents are paralysed by grief, and their suffering and agony interfere with their parenting abilities. In Art’s case, he is swamped by Anja’s and Vladek’s grief for their lost son, Richieu. Spiegelman depicts Art’s jealousy and insecurity that are a consequence of a perverse type of sibling rivalry with his deceased “ghost” brother. Richieu died at age “five or six” during the holocaust by swallowing a poisonous pill given to him by a desperate carer, Tosha, who feared death in the gas chambers. Spiegelman refers to a large, “blurry” photograph that hangs above Art’s parents’ bed. The caption states, “It’s spooky having sibling rivalry with a snapshot!” During a rare conversation with Francoise in the car, Art divulges his vulnerability and his position of disadvantage: “The photo never threw tantrums or got into any kind of trouble…it was an ideal kid and I was a pain in the ass. I couldn’t compete.”

Not only does Art feel inferior to his sibling; Spiegelman also suggests that Art, much like Vladek, is suffering from his own perverse form of survivor guilt. In a forlorn and an indignant tone he also anticipates his parents’ disappointment, “He’d have become a doctor, and married a wealthy Jewish girl..the creep”. Vladek inadvertently refers to Art as Richieu in the final frame of the graphic novel. “I’m tired from talking, Richieu, and it’s enough stories for now.” This reveals the extent of Vladek’s continued sadness. The unbordered gravestone of Anja and Vladek at the end also serves as a memorial to the Jewish victims, Art suggests that Richieu’s death also contributes to Anja’s suicide and the complicated and suffocating emotions between mother and son.

The experiences of the holocaust also traumatised Art’s mother Anja which creates emotional problems between mother and son. These emotions surface in different ways for each of them. Feeble and distraught at the loss of Richieu, Anja emotionally strangles Art as she fears losing another son. As a consequence, Art stifles his own emotional response towards his mother, which leads to guilt. The darkness and horror of “Prisoner on the hell planet” reveals that Art feels as though he should have done more to keep his mother alive.. The word ‘Hell’ in the title instils a feeling of dread. The ghost-like thriller of the large black monster and the abstract drawings of the skull and the bony hands depict Art as the hideous victim of a grisly perfect crime story. In a clever role reversal, Spiegelman depicts Vladek as a heartbroken victim, weeping on the floor, which shows his ghostly horror at the fact that he has failed to fulfil his promise to Anja that “you’ll see that together we’ll survive”. This is also despite the parallel narrative of the love story. Vladek’s eyes are black and large and there are no pupils. Art wears the pin-striped Jewish prisoner uniform which features prominently in the graphics related to the concentration camp. It also shows the beginning of Art’s and Vladek’s psychological distance towards each other, compounded by the guilt of the mother’s suicide. As an incensed Art says, “I was expected to comfort HIM” Art becomes paranoid that every guest and friend thought it was his fault. Art was always resentful of how Anja ‘tightens the umbilical cord’. It is apparent that Anja does this because she does not wish to lose another son. However, Art constantly resists her love. He says, ” Well mom, if you’re listening … congratulations! … you’ve committed the perfect crime.” Graphically, Art’s hand grasps the door of an enormous cage as he accuses the mother of placing him in an impossible emotional situation: “You put me here…shorted all my circuits…cut my nerve endings…and crossed my wires!…you murdered me mommy and you left me here to take the rap!!!” Anja’s death, then, also exacerbates the emotional distance between Vladek and Art which is based on guilt.

In Maus, Spiegelman leaves readers in no doubt that the children of the holocaust survivors continue to suffer from the displaced trauma of their parents. Many children experience and encounter similar struggles. Throughout his discussions with his father, Art seeks to uncover the burden and the pain that Art continues to carry, and which is passed onto his son. This trauma affects Vladek’s ability to be a loving and supportive father and he fails to provide the emotional support for which Art yearns. Finally, The Complete Maus highlights the way second generation holocaust survivors struggle with trauma, the agony of loss and the depression and displaced anxiety which haunts their parents.

Return to Maus: Notes by Dr Jennifer Minter, English Works

For Sponsorship and Other Enquiries

Keep in touch.

83 pages • 2 hours read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more. For select classroom titles, we also provide Teaching Guides with discussion and quiz questions to prompt student engagement.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Part 1, Chapters 1-2

Part 1, Chapters 3-4

Part 1, Chapters 5-6

Part 2, Chapters 1-2

Part 2, Chapters 3-5

Key Figures

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Why does Spiegelman use animals to represent the people of Maus ? Explain why he chooses certain animals to represent different nationalities and ethnic groups. What are the advantages and disadvantages of this choice?

Spiegelman begins Maus with the story of his parents’ courtship against Vladek’s wishes. What are Art’s and Vladek’s perspectives on this issue? Why is it important to detail their life before the war?

How do the present-day interactions between Art and Vladek influence the narrative? How does growing up with Holocaust survivors affect Art, and what story elements does he struggle with depicting?

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Related Titles

By Art Spiegelman

Art Spiegelman

Featured Collections

Common Reads: Freshman Year Reading

View Collection

European History

Graphic Novels & Books

International Holocaust Remembrance Day

Jewish American Literature

Pulitzer Prize Fiction Awardees &...

World War II

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Maus Now: Selected Writing, edited by Hillary Chute review – the Maus that made history

While Philip Pullman and Adam Gopnik illuminate Art Spiegelman’s towering graphic novel, few others in this collection succeed in capturing its spark and sophistication

T his job has taught me to be wary of meeting my heroes, but when I interviewed Art Spiegelman in New York in 2011, it really was one of the great days. In his SoHo studio, the air thick with cigarette smoke and whatever strange substance old paper quietly emits (the place groaned with books), he and I talked long and hard about Maus , then shortly to celebrate its 25th birthday, and every moment was – for me, at least – completely thrilling. I’d long wondered about Spiegelman’s daring in the matter of his famous comic. How on earth had he done it, committing to paper what felt at the time like a kind of blasphemy? But sitting opposite him, I think I understood. In conversation, certainty had only to appear on the horizon for ambivalence to wrestle it to the ground – and vice versa. He simply had to work stuff out. I doubt he could have resisted making Maus even if he’d tried.

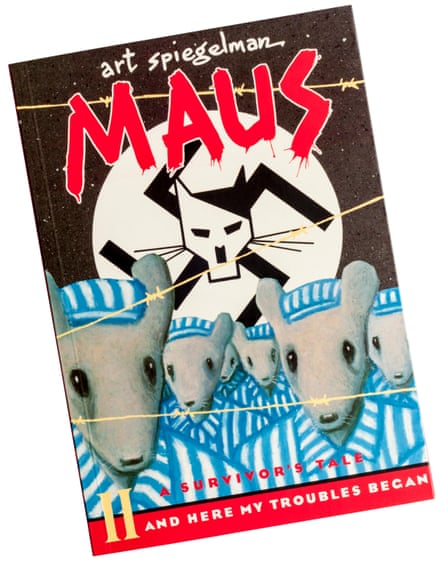

I guess there must still be some people out there who don’t know about Spiegelman’s masterwork. So perhaps I’d better explain. The only comic ever to win a Pulitzer prize, Maus is a two-volume graphic novel about the Holocaust. Based on interviews with his father, Vladek, a survivor of Auschwitz, it depicts Jews as mice, Nazis as cats and Poles as pigs, though the source of the shock it caused when it came out ( Maus I in 1986, and Maus II in 1991) lay more in its refusal to sanctify the survivor than in its anthropomorphism. The Vladek we see living in Queens with his second wife, Mala – the book has two time frames, past and present – is a parsimonious bully and a racist, a man his adult son can tolerate only when they’re discussing the camps. As Spiegelman put it when he spoke to me: “This is the oddness of it. Auschwitz became for us a safe place: a place where he would talk and I would listen.” (Vladek died in 1982; Spiegelman’s mother, Anja, another survivor, had killed herself in 1968.)

Naturally, Maus has been much written about down the decades, not least in recent months (in 2021, a school board in Tennessee decided to ban it from an English curriculum; the outcry that followed led to it selling out on Amazon ). Spiegelman’s paradigm-shifting book appeals to so-called serious types in a way most other graphic novels simply do not. But, alas, it has to be said that this isn’t always a good thing. Wading through Maus Now , a new collection of Maus -inspired pieces edited by Hillary Chute, an academic who writes about comics for the New York Times , is a pretty dispiriting experience. So many words expended to so little effect. So much earnestness and showing off! What on earth, I wonder, does Spiegelman make of it? Again, I picture a struggle: a battle between easy flattery and frankly appalled disdain.

Spiegelman, as it happens, appears in the most interesting piece in the book: a Q&A with the writer David Samuels from 2013. If Samuels, who prefers to make mini-speeches than to ask to-the-point questions, comes off like a bit of jerk, Spiegelman is ever zippy and contrarian, carefully explaining that, for him, being Jewish means carrying on the traditions of the Marx Brothers and the cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman (in a poll, most Jewish Americans had said it meant remembering the Holocaust). He’s fascinating about the creation of the state of Israel – and seemingly uninterruptible on the subject, even by Samuels. But elsewhere, our celebrated author hardly exists; his narrative has taken on a life of its own. Turning the collection’s pages, I was brought back to my student days, when the dead hand of critical theory threw a black polo neck over even the most enjoyable of texts, shrouding them in darkness. Maus tells the worst story of all; at moments, it’s almost unbearable. Yet its very existence is a kind of light, extraordinary and transfiguring. This may be something the contributors to Maus Now are apt to forget.

On the plus side, the book includes decent essays by Philip Pullman, the New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik, and the critic Ruth Franklin (best known as the biographer of Shirley Jackson), and I like its roughly chronological order, a strategy that reveals the way attitudes towards Maus have shifted and settled across the years: Gopnik’s piece dates from 1987, and in it, he’s still agog, wrestling to say intellectually what he knows in his heart to be true. There are also some interesting illustrations, not only by Spiegelman, but by those who worked in the tradition of “physiognomic comparison” (making men look like animals, and animals like men) before him, among them the 17th-century Frenchman Charles le Brun and the artists who made The Birds’ Head Haggadah , a 13th century Ashkenazi illuminated manuscript that is a masterpiece of Jewish religious art. But one must cherrypick; American criticism, which comprises the majority of this book, can be so desperately toneless.

It may be the case that Maus Now , medicinal as it often tastes, will send some readers back to the book that inspired it with new and livelier thoughts in their minds – in which case, hooray. But I also think that one aspect of the genius of Spiegelman’s cartoon is that it speaks so loudly for itself. If it is intricate and masterful, it is also severely and audaciously unpatterned. However many times I read Maus , I always close it with the feeling that no more needs to be said.

Maus Now , edited by Hillary Chute, is published by Viking (£20). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com . Delivery charges may apply

- Book of the day

- Comics and graphic novels

- Literary criticism

- Art Spiegelman

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Art Spiegelman

Ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on Art Spiegelman's Maus . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

Maus: Introduction

Maus: plot summary, maus: detailed summary & analysis, maus: themes, maus: quotes, maus: characters, maus: symbols, maus: theme wheel, brief biography of art spiegelman.

Historical Context of Maus

Other books related to maus.

- Full Title: Maus: A Survivor’s Tale

- When Written: 1978-1991

- When Published: The first volume of Maus (“My Father Bleeds History”) was serialized in Raw magazine, beginning in 1980 and ending in 1991, when the magazine ceased publication. The first volume was published in book form in 1986. The second volume (“And Here My Troubles Began”) was published in 1991.

- Literary Period: Postmodernism

- Genre: Graphic Novel, Memoir

- Setting: Poland and Germany (1930s and 40s); Rego Park, Queens (1970s and 80s); Catskill Mountains (1979); New York City (1987).

- Climax: After years of moving between ghettos and hiding places, Vladek and Anja are sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

- Antagonist: German soldiers and hostile Polish civilians are obvious antagonists for the Jews who are struggling to survive amidst persecution. However, the story also explores the many ways in which Jewish people — and others were who suffered alongside them in concentration camps and in war-torn Poland — harm and undermine one another in moments of desperation. Though Vladek and Anja are beneficiaries of amazing acts of kindness and humanity, and often do their best to help others in return, Maus shows clearly how danger and privation breed selfishness and callousness.

- Point of View: First Person (Vladek and Artie); Third Person (Limited to Artie)

Extra Credit for Maus

Shoah. Some scholars and religious leaders have taken issue with the term “holocaust.” Though the word has been used for decades to refer to the genocide of European Jews, and has been used to describe other mass killings in history, it originates from a Greek word that means “a completely burnt offering to God.” Some argue that to refer to the genocide as a “holocaust” is to compare those murders to religious sacrifices — and that this comparison dignifies the violence and disrespects the victims. Many who disagree with the use of the term “holocaust” substitute “shoah,” a Hebrew term that translates as “catastrophe.”

A Controversial Metaphor. Spiegelman faced criticism, after Maus ’s publication, for his use of animal heads in place of human faces. Because different animals correspond to different ethnicities, he was accused of perpetuating Nazi-like divisions between people of different races, and further dehumanizing the same people Nazis had tried to dehumanize through their violence. The book found a particularly harsh audience in Poland, where many were insulted by the depiction of Polish people as pigs.

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Literature

Essay Samples on Maus

Helping other people in maus.

After reading Maus, a comic book written by Art Spiegelman, I have been asked to present one theme. Therefore, I decided to focus my reflection on all kinds of guilt present in the book as well as in the movie The Schindler List. We may...

- Helping Others

Maus As One Of The Most Prominent Graphic Novels

Maus is the biography of Vladek Spiegelman, who is a Polish surviving Jew from the fields of extermination of the Nazi regime, the story is told through his son Art, a draftsman of comics that wants to leave a memory of the frightening pursuit that...

- Graphic Novel

Post Memory Representation In Maus Novel

Maus, A Survivors Tale, is a graphic novel by Art Spiegelman. He is the second child of two Nazi Holocaust survivors; Vladek and Anja Spiegelman whose story is told through their son in Maus. The text content of the artwork is based on the interview...

Maus: An Extraordinarily Ordinary Man’s Tale Of Survival

Art Spiegelman wrote and illustrated the graphic novel, Maus, in 1980 about his father, Vladek Spiegelman’s, experiences as a Holocaust survivor. The novel depicts the gruesome reality of the terrifying genocide of millions of Jews carried out by the Nazi government during World War II....

The Depiction Of Holocaust In Maus

Maus is a story about the Holocaust written uniquely. Art Spiegelman wrote in a comic book format to tell the story of his father, Vladik’s experience of the Holocaust, and what it was like for Art growing up as the son of a Holocaust survivor....

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

Best topics on Maus

1. Helping Other People In Maus

2. Maus As One Of The Most Prominent Graphic Novels

3. Post Memory Representation In Maus Novel

4. Maus: An Extraordinarily Ordinary Man’s Tale Of Survival

5. The Depiction Of Holocaust In Maus

- Sonny's Blues

- Hidden Intellectualism

- William Shakespeare

- A Raisin in The Sun

- Frankenstein

- A Christmas Carol

- A Rose For Emily

- A Farewell to Arms

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

by Art Spiegelman

- MAUS Summary

Note: Maus jumps back and forth often between the past and the present. To facilitate these transitions in this summary, the Holocaust narrative is written in normal font, while all other narratives are written in italics.

Book I: My Father Bleeds History

As the book opens, it is 1978, and Art Spiegelman arrives in Rego Park, NY, to dine with his father, Vladek, a Holocaust survivor. It is immediately apparent that the two men are not particularly close. Art's mother, Anja, killed herself in 1968, and Vladek is now remarried to a woman named Mala, herself a survivor. The couple does not get along, and there does not appear to be much love in their relationship. Vladek, constantly fearful that Mala will steal his money, is intensely stingy and treats his wife like little more than a maid. After dinner, Art tells his father that he wants to draw a book about his experiences in the Holocaust, and Vladek starts to tell his son the story of how he met Anja.

It is 1936. Vladek is living in Czestochowa, Poland, and has been dating a girl named Lucia Greenberg for several years. One day he travels to Sosnowiec and is introduced to Anja, the intelligent daughter of a wealthy manufacturer. They are married in 1937, and Anja's father gives Vladek part-ownership in his profitable business. Anja gives birth to the couple's first child, Richieu, soon after the marriage. After the birth, Anja becomes consumed with depression, and Vladek takes her to a sanitarium for the next three months. When they return, Vladek is drafted into the Polish army and sent west to guard the border in anticipation of a German attack.

As the Germans advance, Vladek manages to kill one soldier before he is captured and taken to a prisoner of war camp. One night, Vladek dreams of his grandfather, who tells him that he will be released during the Jewish week of Parshas Truma. Three months later, it is Parshas Truma, and Vladek is indeed released. When he returns to Sosnowiec, there are twelve people living in Anja's father's house. The family's business has been taken over by the Germans, and they are living off of their savings. Vladek meets an old customer, Mr. Ilzecki , and the two begin a dangerous business of black market dealings.

In 1942, the Jews are forced to move to a separate part of town. Soon after, Anja's grandparents are told to report for transport to a new community for the elderly. The family hides them, but soon they are taken away to Auschwitz. Not long after, all remaining Jews are told to report to a nearby stadium for "registration." Here, the elderly, families with many children, and people without work cards are sent to the left, while everyone else is taken to the right. Those on the left are sent to their deaths at Auschwitz. Vladek's father is sent to the right, but when he sees his daughter alone with her four children on the left, he crosses over to be with her. None survive the war.

Art speaks briefly with Mala about her own Holocaust experiences before going to the living room to look for his mother's diaries, in which Vladek said she had recorded all her experiences during the war. He cannot find them.

A few days later, Mala calls Art early in the morning in hysterics. Vladek, it seems, climbed on top of the roof in an attempt to fix a leaky drain and then climbed back down because he felt dizzy. Art does not want to help, and Vladek finally arranges for his neighbor to help him. A week later, Art visits his father, clearly feeling guilty. Vladek is upset, having found a comic Art had drawn years ago about the death of Anja, titled "Prisoner on the Hell Planet: A Case Study ." In the comic, Vladek arrives home in 1968 to see his wife dead in the bathtub. Art has just arrived home from a stretch in a state mental institution, and he feels responsible for his mother's suicide due to neglect and a lack of affection.

In 1943, all Jews are forced into a ghetto in the nearby town of Srodula. Uncle Persis, chief of the Jewish council in the nearby ghetto of Zawiercie, tells Vladek that he can keep Richieu in safety until things calm down. Vladek and Anja agree, and Richieu is sent there with Anja's sister, Tosha . Soon afterwards the Zawiercie ghetto is liquidated by the Nazis. Rather than be sent to the Auschwitz, Tosha poisons herself, her daughter, and Richieu.

In Srodula, Vladek constructs a series of bunkers in which the family can hide during the Nazi raids, but they are eventually captured and sent to a compound to await transport to Auschwitz. By bribing his cousin, Haskel, chief of the Jewish Police, Vladek is able to arrange for the release of himself and his wife, but Anja's parents are sent to Auschwitz. Miloch and Pesach, Haskel's brothers, build a bunker behind a pile of shoes in the factory where Vladek and Anja hide for many days without food, until the ghetto is finally evacuated. Unsure of where to go, Anja and Vladek walk back to Sosnowiec.

On his next visit, Art, finds Mala crying at the kitchen table. She is miserable in her marriage and thinks Vladek is both cheap and insensitive. Vladek walks into the room, and the two begin to argue over money. Mala leaves in a huff.

Anja and Vladek return to Sosnowiec. They knock on the door of her father's old janitor, who hides them in his shed. They soon move to a safer place - a farm outside the city owned by a Mrs. Kawka . But it is getting cold, and they need a warmer place to live. Vladek befriends a kindly black market grocer named Mrs. Motonowa , who offers her home to the Spiegelmans. The arrangement is comfortable, but one day Mrs. Motonowa is searched by the Gestapo at the market and returns home in a panic, kicking them out of the house. They live on the streets for the night and eventually return to Mrs. Kawka's, who tells them of smugglers who will take them to safety in Hungary.

A few days later, Mrs. Motonowa apologizes and they hide with her again. But Vladek does not feel safe, and he arranges to meet with the smugglers. An old acquaintance, Mandelbaum , is also at the meeting with his nephew, Abraham . Abraham agrees to travel first and write to them if he arrives safely in Hungary. A few days later, they receive a letter from Abraham and board a train with the smugglers, but they are arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the concentration camps.

Back in Rego Park, Vladek tells Art that he burned his wife's diaries shortly after her death in an attempt to ease his own pain. Art is furious and calls his father a murderer.

Book II: And Here My Troubles Began

Vladek leaves a message saying he has just had a heart attack. When Art calls the number his father left, he learns that Vladek is healthy and staying in a bungalow in the Catskills. He left the message, it appears, to ensure that his son would call him back. Mala has left him, and Art and Francoise immediately depart for the Catskills. On the drive, Art tells Francoise about his complex feelings about the Holocaust, including the guilt he feels for having had an easier life than his parents.

Vladek arrives at Auschwitz with Mandelbaum. All around, there is a terrible smell of burning rubber and fat. They see Abraham, who tells them that he, too, was betrayed and forced at gunpoint to write the letter that sent Vladek and Anja to the camps. Vladek begins teaching English to his guard, who protects him and provides him with extra food and a new uniform. Mandelbaum is soon taken off to work and never heard from again. After a few months, the guard can no longer keep Vladek safe as a tutor, and he arranges for him to take a job as a tinsmith.

It is 1987, a year after the publication of the first book of Maus and five years after Vladek's death. Art is depressed and overwhelmed, and visits his psychiatrist, Pavel , also a Holocaust survivor. The two speak about Art's relationship with his father and with the Holocaust. They focus particularly on issues of guilt. Art leaves the session feeling much better and returns home to listen to tapes of his father's Holocaust story.

During this time, Anja is being held at Birkenau, a larger camp to the south. Unlike Auschwitz, which is a work camp, Birkenau is a waiting room for the gas chambers. Anja is despondent and frail, and her supervisor beats her constantly. Vladek makes contact with her through a kind Jewish supervisor named Mancie , through whom he is able to send additional food to his wife. Vladek also arranges to be sent to work in Birkenau, where he is able to speak briefly with Anja.

Vladek arranges to switch jobs from tinsmith to shoemaker, and by fixing the shoes of Anja's guard at Birkenau, he markedly improves her treatment. He learns that some prisoners at Birkenau will begin working at a munitions factory in Auschwitz and saves tremendous amounts of food and cigarettes for a bribe to ensure that Anja is among them. Soon, though, Vladek loses his job as a shoemaker, and he is forced into manual labor. He begins to get dangerously frail, and he must hide during daily "selections" so that he will not be sent to the gas chamber. As the Russians advance towards the camp, he works again as a tinsmith and is made to deconstruct the gas chambers.

The Russian army is now within earshot of Auschwitz, and the prisoners are evacuated under German guard. They march for miles in the freezing snow and are packed like rats into crowded boxcars, where they stay for days with no food or water. Eventually they arrive at Dachau, another concentration camp. Only one in ten prisoners survive this trip.

Vladek, Francoise, and Art drive to a grocery store, where Vladek attempts to return opened and partially-eaten food items. Art and Francoise wait in the car in embarrassment, but to their surprise, Vladek is successful.

At Dachau, Vladek meets a Frenchman who is able to receive packages through the Red Cross due to his non-Jew status. He shares this extra food, likely saving Vladek's life. Vladek eventually contracts typhus and lies close to death for days, until his fever begins to subside. Just as it does, the sick that are able to walk are boarded onto a train bound for Switzerland to be exchanged as prisoners of war. Vladek is among them.

On the way home from the grocery store, Francoise stops to pick up an African-American hitchhiker. Vladek is profoundly distrustful of blacks, and he is furious.

Vladek is made to leave the train and move on foot towards the Swiss border. The war ends before they reach it, and their guards march them back onto a train that they say will take them to the Americans. But when the train arrives at its destination, there are no Americans, and the prisoners walk off in all directions. Vladek is stopped by a German patrol and made to wait by a lake, where he meets his old friend Shivek . The Jews think that they will be killed, but when morning comes the guards are gone. Vladek and Shivek begin to walk again, but they encounter yet another German patrol, which forces them into a barn with fifty other Jews. Again, they fear for their lives, but when they awaken the next morning, the guards are gone. Vladek and Shivek eventually find an abandoned house, where they stay until the Americans arrive and take the house for military use.

Vladek shows his son a box of old photographs of his family, mostly from before the war. Of his parents and six siblings, only one brother, Pinek, survived.

Art is in his apartment when he receives an urgent and unexpected call from Mala. She is in Florida and back together with Vladek, though she does not seem happy about it. Vladek had just been admitted to the hospital for the third time in a month, and now he has left against the advice of his doctors. He wants to see his doctor in New York. Art flies down to help him get home. Back in New York, Vladek sees his doctor and is cleared to go home. A month goes by before Art visits his father again. When he arrives, Mala tells him that Vladek has been getting confused. Art sits down on the end of his father's bed and asks him about the end of the war.

Vladek and Shivek leave the German farm for a displaced persons camp, where they receive identification papers. Life at the camp is easy, but Vladek soon leaves with Shivek for Hannover, where Shivek has a brother. While in Hannover, Vladek hears word that Anja is still alive, and he departs for Sosnowiec. The trains are largely incapacitated, and the journey takes him over three weeks, but he eventually arrives for a tearful reunion with his wife.

And here Vladek ends his story: "I'm tired of talking, Richieu," he tells Art, calling him by the name of his dead brother, "and it's enough stories for now."

MAUS Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for MAUS is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Page 32, “Right away, we went.” Where are Vladek and Anja going and why?

Right away, we went. The sanitarium was inside Czechoslovakia, one of the most expensive and beautiful in the world.

Anja, Vladek's wife and Spiegelman's mother, went to a sanatorium in Czechoslovakia in 1938.

Vladek wants to go to Hungary in order to escape the danger and uncertainty of his life, as well as Anja's. Hungary represents hope and safety.

The visual device used to show the difference betweem Vladek and Anja is that Anja has a tail protruding from under her coat, a detail that emphasizes her Jewish identity.

Study Guide for MAUS

MAUS study guide contains a biography of Art Spiegelman, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- Character List

Essays for MAUS

MAUS essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of MAUS by Art Spiegelman.

- Stylistic Detail of MAUS and Its Effect on Reader Attachment

- Using Animals to Divide: Illustrated Allegory in Maus and Terrible Things

- Father-Son Conflict in MAUS

- Anthropomorphism and Race in Maus

- A Postmodernist Reading of Spiegelman's Maus

Lesson Plan for MAUS

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to MAUS

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- MAUS Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for MAUS

- Introduction

- Primary characters

- Publication history

Advertisement

Supported by

Art Spiegelman on Life With a ‘500-Pound Mouse Chasing Me’

Known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning comic book, “Maus,” the author has had a busy year, after the book was banned and jump-started a fresh debate about the sanitization of history. Frankly, he’s ready to get back to work.

- Share full article

By Alexandra Alter

On a recent afternoon, Art Spiegelman was sitting in the living room of his SoHo apartment, puffing on an e-cigarette that he wears around his neck, clipped to a pen holder so that he doesn’t misplace it. “I’m always losing things,” he explained.

He was feeling more disoriented than usual, having just returned home after several weeks on the road — a two-week road trip across the South with his son, Dash; a research excursion to a comics museum in Columbus, Ohio, for a new project; and a stop in Cincinnati to attend a memorial service for the cartoonist Justin Green, a close friend and mentor of his.

The whirlwind trip capped a momentous and chaotic year for Spiegelman, the iconic cartoonist, who was thrust into a national debate about censorship and rising antisemitism after a Tennessee school district banned his Pulitzer Prize-winning graphic novel, “Maus,” from classrooms in January.

Since then, Spiegelman has been called upon again and again to champion and defend his work. He’s given countless interviews, speeches and webinars, including a Zoom meeting with residents of the Tennessee county where “Maus” was removed after parents objected to scattered instances of profanity and nudity in the text. He has argued repeatedly that the ban is about much more than “Maus,” which details his parents’ experience during the Holocaust, depicting Jews as mice and Nazis as cats. To Spiegelman, the decision to remove “Maus” from schools reflects a more insidious campaign to sanitize disturbing chapters of history, under the guise of “protecting” children.

“They want a kinder, gentler, fuzzier Holocaust,” he said.

Ironically, the ban has brought droves of new readers to his work and underscored its ongoing relevance, at a moment of heightened fear over a resurgence of antisemitism, fascism and white nationalist movements. “Maus” shot to the top of the best-seller list and sold 665,000 copies this year, more than triple its 2021 sales.

But the renewed attention has also been exhausting, and left him with little time or energy for his art, said Spiegelman, who never wanted to be a spokesman for Holocaust remembrance, and would rather be sketching in his notebook.

“It’s been a wild year,” he said, adding, “I’m done.”

Of course, Spiegelman is not unaccustomed to the spotlight. Fame has followed him ever since “Maus” won the Pulitzer Prize in 1992, becoming the first comic book to win the award, and transformed the medium, proving that comics can be a form of high art and literature. It sold six million copies in the United States, becoming a staple of school curriculums and a classic of Holocaust literature.

Still, this past year, Spiegelman has been in especially high demand. In November, the National Book Foundation awarded Spiegelman a medal for distinguished contribution to American letters. This fall, a new collection of essays and criticism about “Maus” and its enduring resonance, called “Maus Now,” was released by Pantheon. And to Spiegelman’s great delight, Pantheon just reissued a new edition of “Breakdowns,” an anthology of his early work, which was first published in 1978, and never received much attention outside of academic and hard-core cartoonist circles.

“There’s a small coterie of people who really read comics that know what I do,” Spiegelman said. “But for the most part, ‘Maus’ is like this giant skyscraper.”

The collected images, which feature his comics from the 1970s and later work from the 2000s, offer a glimpse of Spiegelman’s range as an illustrator and the breadth of his influences. The drawings include gag comics, a detective serial with a Cubist bent and some images that veer into hard-core pornography. The anthology also features intimate, emotional drawings that capture his devastation after his mother’s suicide, and reveal how he internalized his parents’ lingering trauma.

“This is where I found my own voice,” Spiegelman said of the work in “Breakdowns.” “I discovered territory that was genuinely mine.”

Close students and fans of Spiegelman’s work view “Breakdowns” as a sort of Rosetta Stone that offers a master key to his intricate and varied visual idiom, revealing his enormous and often overlooked range as an artist.

“On one level, it’s a deeply formalist book, showing how anti-narrative comics can be, with this avant-garde experimental language that Art is exploring,” said Hillary Chute, a professor of English, art and design at Northeastern University who edited “Maus Now” and has studied Spiegelman’s work for years. “It’s also incredibly personal.”

The reissue was already in the works well before the “Maus” ban, but the timing has proved fortuitous, said Lisa Lucas, Pantheon’s publisher.

“The reissue of ‘Breakdowns’ has coincided with a moment when the import of Art Spiegelman’s extraordinary career has become so deeply apparent to the culture,” Lucas wrote in an email. “Given the increased attention to his work and career, it’s exciting that so many new readers will learn about Art’s contributions to comix writ large.”

Spiegelman, 74, speaks softly and with precision, and has a reserved, professorial demeanor that can seem at odds with some of his transgressive early comics, which can be hypersexual or grotesquely morbid.

He reflected on his work and its legacy for nearly two hours on a recent frigid December afternoon, alternately sitting and pacing in the art- and book-filled apartment where he and his wife and creative collaborator, the New Yorker art editor Françoise Mouly, have lived since the mid 1970s. Back then, they had a printing press in their living room, where they put together editions of Raw, an eclectic, alternative comics magazine that published luminaries like Robert Crumb, Richard McGuire, Chris Ware and Justin Green , who was one of Spiegelman’s idols.

It was Green who showed him that “that confessional, autobiographical, intimate, unsayable material is perfectly fine content for comics,” Spiegelman said.

“It’s not just, ‘Make a joke,’ or, ‘Make a fantasy story,’” he continued. “This was like, ‘What’s going on in one’s brain, and how can you express it?’”

As a boy growing up in Queens, Spiegelman was haunted by the feeling that he shouldn’t exist, given his parents’ narrow escapes from the death camps, and found refuge in the subversive humor and wild art of Mad magazine and other comics. He began drawing early, prompted by doodling games he played with his mother, a playful side of her that he captures in “Breakdowns.” When he was just 13, he published a comic in a weekly Queens newspaper, which later hired him as a freelancer.

In 1966, he got a job at Topps Chewing Gum, designing stickers and novelty cards. The company subsidized his career for 20 years, giving him a steady income while he experimented with edgier and less commercial comics.

Spiegelman was shaped by the underground comic scene of the 1960s, and became a fixture in some of the era’s magazines, which peddled cartoons about drugs, sex and twisted genre stories. He arrived at a turning point in his career and life in the late ’60s, when he was hospitalized after a mental breakdown, got kicked out of college and was shattered by his mother’s suicide.

He became interested in mixing high and low art, and in pushing the boundaries of narrative in comics, exploring how time and space could be compressed or stretched in a series of images, and how interior experiences and memory could be illustrated on the page.

“For me to be able to bring the vocabulary of everything from Gertrude Stein and James Joyce to Picasso and other more formal aspects of picture-making, opened up very new territory,” Spiegelman said. “In order to do ‘Maus,’ everything I learned here became new vocabulary for me.”

In 1972, Spiegelman drew a three-page comic that later evolved into “Maus.” It opens with Spiegelman, as a young mouse, in bed as his father tucks him in and tells him the story of how he was captured in Poland by Nazis and sent to Auschwitz. Using animal faces in place of people gave him enough distance to tell the story. “For me, it was powerful just because it allowed me to deal with the material by putting a mask on people,” he said. “By reliving it microscopically, as best I could, moment by moment — it allowed me to at least come to grips with something that otherwise was only a dark shadow.”

Spiegelman worked on “Maus” for 13 years. It swelled to over 300 pages, and recounts the story of how his father and mother, Vladek and Anja, survived unimaginable horrors in a Nazi concentration camp, intertwined with the narrative of his own experience as a cartoonist, recording conversations with his father and aiming to capture the unspeakable in images. The first chapter was printed in 1980 in Raw, where it was serialized over the next decade.

When Spiegelman tried to find a publisher for a book version, the manuscript was widely rejected until Pantheon took it on. Spiegelman never imagined that it would become such a cultural and historical behemoth, or that decades later, it would become “cannon fodder in the culture wars,” as he put it.

“The only person I wanted to teach anything to was myself. I wanted to find out how I got born, when both my parents were supposed to be murdered before I could be conceived,” he said. “And so that was a complex project, to reconstruct for myself what that history was for them.”

“Maus” has long been a magnet for controversy. Critics took offense at the use of animal imagery to explore such a grave subject, and some said it was doubly offensive that Spiegelman drew Jews as mice, given that Nazi propaganda compared Jews to vermin — which was precisely Spiegelman’s point. It was banned in Russia because of the swastika image on the cover. When it was published in Poland in 2001, protesters, who were outraged that Spiegelman depicted Polish gentiles as pigs, burned copies of the book. In Germany, Spiegelman was asked by a reporter if a cartoon about Auschwitz was in bad taste. “No, I thought Auschwitz was in bad taste,” Spiegelman replied .

In the years since its release, Spiegelman has often felt oppressed by the scale of the book’s success, which has overshadowed all his other work. “Ever since ‘Maus ,’ I’ve been having to deal with a 500-pound mouse chasing me,” he said.

Spiegelman hopes that the revival of “Breakdowns” could introduce readers who only know “Maus” to a greater range of his work.

Looking back on the artist he was when he drew the works in “Breakdowns,” Spiegelman feels a mixture of affection and pride, for what he overcame and what he was able to create.

“I admire that guy,” he said with a smile. “Yeah. I was on fire.”

Alexandra Alter writes about publishing and the literary world. Before joining The Times in 2014, she covered books and culture for The Wall Street Journal. Prior to that, she reported on religion, and the occasional hurricane, for The Miami Herald. More about Alexandra Alter

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

What can fiction tell us about the apocalypse? The writer Ayana Mathis finds unexpected hope in novels of crisis by Ling Ma, Jenny Offill and Jesmyn Ward .

At 28, the poet Tayi Tibble has been hailed as the funny, fresh and immensely skilled voice of a generation in Māori writing .

Amid a surge in book bans, the most challenged books in the United States in 2023 continued to focus on the experiences of L.G.B.T.Q. people or explore themes of race.

Stephen King, who has dominated horror fiction for decades , published his first novel, “Carrie,” in 1974. Margaret Atwood explains the book’s enduring appeal .

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

- Environment

- Information Science

- Social Issues

- Argumentative

- Cause and Effect

- Classification

- Compare and Contrast

- Descriptive

- Exemplification

- Informative

- Controversial

- Exploratory

- What Is an Essay

- Length of an Essay

- Generate Ideas

- Types of Essays

- Structuring an Essay

- Outline For Essay

- Essay Introduction

- Thesis Statement

- Body of an Essay

- Writing a Conclusion

- Essay Writing Tips

- Drafting an Essay

- Revision Process

- Fix a Broken Essay

- Format of an Essay

- Essay Examples

- Essay Checklist

- Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Research Paper

- Write My Research Paper

- Write My Essay

- Custom Essay Writing Service

- Admission Essay Writing Service

- Pay for Essay

- Academic Ghostwriting

- Write My Book Report

- Case Study Writing Service

- Dissertation Writing Service

- Coursework Writing Service

- Lab Report Writing Service

- Do My Assignment

- Buy College Papers

- Capstone Project Writing Service

- Buy Research Paper

- Custom Essays for Sale

Can’t find a perfect paper?

- Free Essay Samples

- Entertainment

Essays on Maus

Maus is the story of Art Spiegelman’s interviews with his father Vladek about his Holocaust experiences. The book was serialized from 1980 to 1991, and the first volume won a Pulitzer Prize in 1992. It is a fable, and it can also be seen as an allegory. It reflects several...

Found a perfect essay sample but want a unique one?

Request writing help from expert writer in you feed!

Related topic to Maus

Making It Visual for ELL Students: Teaching History Using Maus

- Resources & Preparation

- Instructional Plan

- Related Resources

This unit for secondary English-language learners (easily adaptable for reluctant readers) is designed to develop students' confidence and sense of autonomy in reading through the intellectually substantive graphic novel Maus . Maus deals with the traumatic history and enduring legacy of the Holocaust through multiple narratives of a father, mother, and son.

Ongoing lesson activities involving vocabulary study and reading strategies support students' comprehension of the novel. Since Maus is the story of a son telling his father's story, students make personal connections to the text as they interview a family member and retell a story about that person's past. Students use websites listed in the lesson resources for research into World War II, the Holocaust, and human rights. Structured discussion encourages students to relate human rights concepts to events in the novel, historical events, and events in their own experience.

Featured Resources

- Maus (Vols. I & II) by Art Spiegelman (Pantheon Books, 1986; 1991)

From Theory to Practice

- Teaching graphic novels can be an alternative to traditional literacy pedagogy, which ignores the dynamic relationships of visual images to the written word.

- The multimodalities of graphic novels such as Maus and Persepolis , along with their engaging content reflecting the diverse identities present in many classrooms, work in tandem to help deepen students' reading engagement and develop their critical literacies.

- Making connections between these stories and students' own experiences, and drawing on their outside multiliteracies practices aid literacy development.

- Students' engaged reading is "often socially interactive" (p. 4). These interactions are clearly evident in the reading club, chat room, blog, and posting activities that have flourished in the wake of recent phenomenally popular books among adolescent and adult readers.

- Students' increased engagement with particular genres (in this case, graphic novels) can facilitate their entry and apprenticeship into important social networks that amplify opportunities for academic success in mainstream classes.

Situated practice, which draws in part from students' own life experiences Overt instruction that introduces meta-languages to deconstruct the myriad and multimodal ways in which meaning is constructed Critical framing of the cultural and social context in which meaning is disseminated and understood Transformed practice that aims to re-situate all of these meaning-making practices to work in other cultural sites or contexts

- One approach that fosters reading engagement involves a pedagogy of multiliteracies with its four dimensional instructional framework:

Common Core Standards

This resource has been aligned to the Common Core State Standards for states in which they have been adopted. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, CCSS alignments are forthcoming.

State Standards

This lesson has been aligned to standards in the following states. If a state does not appear in the drop-down, standard alignments are not currently available for that state.

NCTE/IRA National Standards for the English Language Arts

- 1. Students read a wide range of print and nonprint texts to build an understanding of texts, of themselves, and of the cultures of the United States and the world; to acquire new information; to respond to the needs and demands of society and the workplace; and for personal fulfillment. Among these texts are fiction and nonfiction, classic and contemporary works.

- 2. Students read a wide range of literature from many periods in many genres to build an understanding of the many dimensions (e.g., philosophical, ethical, aesthetic) of human experience.

- 3. Students apply a wide range of strategies to comprehend, interpret, evaluate, and appreciate texts. They draw on their prior experience, their interactions with other readers and writers, their knowledge of word meaning and of other texts, their word identification strategies, and their understanding of textual features (e.g., sound-letter correspondence, sentence structure, context, graphics).

- 6. Students apply knowledge of language structure, language conventions (e.g., spelling and punctuation), media techniques, figurative language, and genre to create, critique, and discuss print and nonprint texts.

- 8. Students use a variety of technological and information resources (e.g., libraries, databases, computer networks, video) to gather and synthesize information and to create and communicate knowledge.

- 10. Students whose first language is not English make use of their first language to develop competency in the English language arts and to develop understanding of content across the curriculum.

Materials and Technology

- Large map of Europe

- Overhead projector with projection screen and transparencies

- Computers with Internet access

- DVD of The Pianist directed by Roman Polanski (Universal, 2003)

- DVD player and monitor (or computer with DVD drive and projection capability)

- Story Map for Essays

- Character Perspective Chart

- Story Organizer

Student Objectives

Students will

- Learn about the Holocaust, its historical lessons, and important relevance for today

- Develop critical reading and thinking skills through engagement with the graphic novel in a multiliteracies instructional framework

- Develop and utilize visual literacy skills to aid and support reading comprehension and deepen understanding of history texts

- Gain the knowledge to compare how specific content is presented across modal genres (films, websites, books, articles)

- Present personal interpretations and understanding of history in oral and written forms

- Draw on personal experiences and literacy practices to construct knowledge

Session 1: World War II—KWL chart and presentations

Given that many ELLs know little or nothing about the Holocaust, a few introductory activities are required to provide background information.

Note: Based on the Want to know questions formulated by the class, prior to Session 2 you can develop a list of guiding questions for Internet research, to help direct students to key points. Also identify specific sections, paragraphs, or graphics within the recommended Websites in the Resources section to facilitate fact finding. Post or bookmark the websites you wish students to visit. Most students lack the ability to select sites that are appropriate to their reading level, and are not skilled at filtering out commercial or inappropriate sites.

Session 2: World War II Research

This research may require more than one session.

Session 3: Human Rights—KWL

Session 4: film.

Show students the first half of the film The Pianist , up to the point where Szpilman's family is sent away to Auschwitz on the train. This excerpt shows the systemic way in which the Jews' rights were taken away, and gives students a strong feeling of time and place. It also offers a point for comparisons once they have gotten into reading Maus .

Sessions 5–6: Introduction to Narrative and Point of View

Maus is the story of a son telling his father's story. For teenagers, telling stories of one's parents may not be an activity they readily connect with. An in-class writing assignment helps to set the stage for Art Spiegelman's project about his own father. A few days prior to Session 5, give students a homework assignment to interview a family member. Explain that they are gathering information for a story (which they will write in class) about that person's past, so they should take notes on all important details, such as names and dates. Session 5

Sessions 7–11: Vocabulary and Reading Strategies

In order to maximize students' comprehension, preteaching vocabulary in each session is highly recommended. Choose 5-10 words that you know students will be encountering in upcoming pages. For example, in Chapter 1 of Maus , the following words may not be familiar to students: dowry , bachelor , well off , hosiery , druggist , reputation , and character . Choose words that are general enough that they would be found in other contexts. (Words specific to the story, such as Auschwitz , should be talked about separately.) Session 7

Sessions 8-11 Continue to spend the beginning of each session (about half of the session) on vocabulary instruction, targeting words that will appear in the reading. Spend the rest of the session on reading strategies.

Sessions 12–14: Critical Connections

One of the stated goals of this lesson is to develop students' awareness of human rights by helping them to make the connection between the violations of human rights during the Holocaust and the continuing need for vigilance about rights, including situations in their own counties and lives. It is therefore useful to familiarize students with The Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the General Assembly of the United Nations in 1948. Session 12

Session 14 Divide students into groups and assign each group a number of the rights listed in The Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Ask them to prepare an oral presentation. Topics for discussion may include

- Which rights from their section they understand best

- Which are most important

- Examples of how these rights are protected or violated in their own world

Persuasive Essay: Have students write a persuasive essay using the thesis "human rights are important and must be protected." Ideally this would not be students' first attempt at writing a multi-paragraph essay.