Ontario.ca needs JavaScript to function properly and provide you with a fast, stable experience.

To have a better experience, you need to:

- Go to your browser's settings

- Enable JavaScript

Indigenous education in Ontario

Learn about the support for First Nation, Métis and Inuit students.

On this page Skip this page navigation

We are committed to working with Indigenous partners and the education sector to improve access to education for Indigenous students in Ontario and support First Nation, Métis and Inuit student achievement and well-being. This includes:

- closing the achievement gap between Indigenous students and all students

- increasing every student’s knowledge and awareness of Indigenous histories, cultures, perspectives and contributions

Supporting Indigenous education in schools and school boards

Indigenous education leads.

Every school board must have a full-time position dedicated to supporting Indigenous education in school boards. Leads work closely with senior board administration, including the superintendent responsible for Indigenous education, school board staff and Indigenous Education Councils. The leads support:

- improved Indigenous student achievement and well-being

- enhanced knowledge and awareness about First Nation, Métis and Inuit cultures, histories and perspectives for all students

Indigenous Education Councils ( IECs )

The IECs guide school boards and schools in building stronger relationships with communities, sharing information, identifying promising practices and enhancing collaborative work to support First Nation, Métis and Inuit student achievement and well-being. All school boards must have formal structures such as IECs to support Indigenous education in school boards.

Contact your school board to learn about your local Indigenous Education Council.

Support for students

Indigenous graduation coach program.

Some school boards have Indigenous graduation coaches to help Indigenous students obtain an Ontario Secondary School Diploma and successfully transition into postsecondary education, training or labour market opportunities.

This program is a flexible, culturally sound program that allows boards to build a supportive process for Indigenous students to succeed in school.

Contact your school to see if an Indigenous graduation coach is available through your school board.

Alternative Secondary School Program within Indigenous Friendship Centres

In partnership with the Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres, local Friendship Centres and school boards, the Alternative Secondary School Program offers culturally-relevant education programming and learning supports for Indigenous students working toward graduation. The program focuses on:

- Indigenous approaches and ways of knowing

- land-based learning

- connection to community

- access to Indigenous knowledge keepers and elders

The program follows a trauma-informed education model that puts well-being and holistic approaches to education at the centre of learning.

Contact your school board or local Indigenous Friendship Centre to see if the program is available in your area.

Voluntary and confidential self-identification

You have the right to voluntarily and confidentially self-identify as First Nation, Métis and/or Inuit at your school or your student’s school if you are:

- a parent and/or guardian of an Indigenous student

- and Indigenous student and you are 18 years or older

Schools, school boards and the Ministry of Education use this information to better understand how to target funding and programs to support Indigenous student well-being and success.

Contact your school if you would like to learn more about voluntary, confidential Indigenous student self-identification.

Guide to develop a policy for Indigenous student self-identification

For information on how school boards can develop a voluntary, confidential Indigenous student self-identification policy, visit the guide to developing policies for Indigenous student self-identification page.

First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework

The First Nation, Métis and Inuit Education Policy Framework was released in 2007 and outlined our approach to supporting First Nation, Métis and Inuit learners in Ontario. The framework identified two primary challenges to be addressed by 2016:

- to improve achievement among First Nation, Métis , and Inuit students

- to close the achievement gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students

Read the framework .

Progress reports

There are three progress reports based on ten performance measures. Starting in 2007, we published a progress report every three years until 2018.

Partnerships

Master education agreement.

In August 2017, the Minister of Education joined participating First Nations in signing the Master Education Agreement. The historic agreement describes the relationship between the Anishinabek Education System and Ontario’s provincially funded education system and sets out commitments between the parties to support:

- the transition of students between Anishinabek First Nations’ schools and schools in the provincially-funded education system

- advancement of Anishinabek language and culture and the knowledge of Anishinabek First Nations’ histories, perspectives and contributions within Anishinabek First Nations’ schools and provincially funded schools

- engagement and participation of students, parents, families and communities to realize the goal of improved student achievement and well-being

Métis Nation of Ontario ( MNO )

In 2009, Ontario and the Métis Nation of Ontario ( MNO ) entered into a Memorandum of Understanding ( MOU ), which made a commitment to ongoing collaboration aimed at improving educational outcomes for Métis students in the province. The memorandum supports collaborative relationships between Métis communities, school boards and education partners. This includes recognizing and preserving the distinct history, identity and culture of the Métis people and their contributions to Ontario. On December 15, 2015, the MNO signed a new MOU with the Ministry of Education.

Read the memorandum of understanding. ( PDF , 486 Kb )

Nishnawbe Aski Nation ( NAN )

On April 9, 2013, Nishnawbe Aski Nation ( NAN ), Canada and Ontario signed a historic MOU ( PDF , 158 Kb ) on First Nation education that made a commitment to working together to improve educational outcomes for First Nation students in First Nation-operated and provincially funded schools. This was the first tripartite education agreement to be signed in Ontario. Key priority areas of the memorandum of understanding include:

- student support services

- curriculum enhancements

- governance and administration

- human resources

- parental participation

Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians

On February 27, 2017, Canada, Ontario and the Association of Iroquois and Allied Indians signed an MOU on First Nation Education – the second tripartite education agreement signed in Ontario – through the Education Partnership Program. Key priority areas of the memorandum of understanding include:

- language and culture

- relationship building

- Student transitions

Grand Council Treaty #3 ( GCT#3 )

On May 14, 2021, Grand Council Treaty #3 ( GCT#3 ), Canada and Ontario signed an MOU on First Nation education through the Education Partnerships Program. The MOU focuses on priority areas identified with Grand Council Treaty #3 and with the Federal Government to improve educational outcomes for Grand Council Treaty #3 learners, such as:

- Early learning

- Culturally appropriate teaching and learning resources

- Professional development

- Relationship-building

- Transitions

- Supporting partnerships and relationship-building though the Reciprocal Education Approach and other processes

Tungasuvvingat Inuit ( TI )

On November 27, 2017, the Ministry of Education formalized its working relationship with Tungasuvvingat Inuit ( TI ) through a memorandum of understanding – the first of its kind between the province and the Inuit community. The memorandum supports:

- collaborative relationships between Inuit communities, school boards and education partners to promote student success

- the inclusion of Inuit culture, values and traditions in the development of provincial education initiatives

Read the memorandum of understanding ( PDF , 1.04 Mb ).

Inuit capacity building in school boards

The ministry provides Inuit capacity building funding to TI to supports the success and well-being of Inuit learners through increasing access to language classes and resources that support cultural safety and integrate Inuit culture into daily classroom activities. This program aims to increase equity when students enter the school system, and support improved retention, credit accumulation and graduation rates.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

On May 30, 2016, Ontario released The Journey Together – Ontario's Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples . As part of Ontario’s response to the Truth and Reconciliation Report, we made the following new commitments.

Support for Indigenous languages

Language is the foundation of culture. Indigenous peoples have a strong tradition of oral histories that must be supported by a new respect for, and understanding of, Indigenous languages. Part of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission Reports calls for protecting the right to Indigenous languages, including the teaching of Indigenous languages as credit courses. The Ministry of Education is committed to developing and implementing programs and services that are supportive and reflective of First Nation, Métis , and Inuit cultures and languages.

“ Anishinaabemodaa ” – “Let’s speak Ojibwe” Initiative

Since the 2016-17 fiscal year, the ministry has provided funding to support the community-led “ Anishinaabemodaa ” – “Let’s speak Ojibwe” Initiative (formerly the Ojibwe Language Revitalization Strategy), in partnership with the Rainy River District School Board ( RRDSB ), the Seven Generations Education Institute and SayITFirst. The aim of the Initiative is to develop pathways for Ojibwe speakers to become Early Childhood Education workers and certified classroom teachers. To date, the initiative has helped to sustain and expand language learning in ten First Nation communities. The initiative has also supported the significant expansion of Ojibwe language learners and developed pathways for RRDSB students to pursue language learning in postsecondary and receive preferred entrance to the Lakehead Faculty of Education.

We work with Indigenous partners to enhance the Ontario curriculum and support mandatory learning about:

- residential schools

- the legacy of colonialism

- the rights and responsibilities we all have to each other as treaty people

Changes to curriula

In response to Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s Call to Action 62 and 63, we implemented the revised Social Studies, Grades 1 to 6; History and Geography, Grades 7 and 8 curriculum and the Canadian and World Studies Grades 9 and 10 curriculum.

These curricula revisions made learning about First Nation, Métis , and Inuit perspectives, cultures, contributions and histories a mandatory component of every student’s education in Grades 4 to 8 and Grade 10.

The revised curriculum is the result of collaboration with Indigenous teachers, Elders, Knowledge Keepers, Métis Senators, First Nations, Métis , and Inuit community representatives, residential school survivors, Indigenous partners, Minister’s Student Advisory Council and other education stakeholders.

In May 2019, we issued the revised Grades 9 to 12 First Nations, Métis , and Inuit Studies curriculum that students started learning in September 2019. This curriculum increases students’ learning about First Nation, Métis , and Inuit perspectives, cultures, contributions, and histories in areas such as art, literature, law, humanities, politics and history.

We have also designated the first week of November as Treaties Recognition Week to promote public education and awareness about treaties and treaty relationships.

Read the curriculum

- First Nations, Métis and Inuit Studies, Grades 9-12, curriculum

- Native Languages Grades 1-8 and Grades 9-12 curriculum

- Social Studies, Grades 1-6; History and Geography, Grades 7-8 curriculum

- Canadian Word Studies, Grades 9-10, curriculum

Curriculum resources about treaties

- The First Nations and treaties map of Ontario – educators guide ( PDF , 448 Kb )

- Scope and sequence related to treaties and land claims (elementary) ( PDF , 868 Kb )

- Instructional activities for Treaties Recognition Week: educator's guide for history, Grades 7 and 8 ( PDF , 1.23 Mb )

- Accommodations for delivery in the virtual classroom ( PDF , 96 Kb )

- Scope and sequence related to treaties and land claims (secondary) ( PDF , 867 Kb )

- Instructional activities for Treaties Recognition Week: educator's guide for history and civics and citizenship, Grade 10 ( PDF , 1.26 Mb )

Reciprocal Education Approach

Through the Reciprocal Education Approach ( REA ), when requirements are met, school boards are required to:

- Admit First Nation students who live on-reserve to a school of the school board

- Provide funding support for students who would ordinarily be eligible to be pupils of the board to attend a First Nation school

For school board obligations to be initiated, certain eligibility criteria must be met and First Nations and students must submit written notice to the school of the school board the student intends to register at or is currently registered at.

Parents, guardians, students and/or Another Authorized Persons are advised to work with their Band, Tribal Council, Education Authority or the federal government, to complete the written notice form.

Using the reciprocal education approach, First Nations and school boards do not need to negotiate and enter into an agreement for the base tuition fee.

Learn more about the Reciprocal Education Approach , including the eligibility requirements for First Nations and students, and a fact sheet about how students can participate.

The Reciprocal Education Approach ( REA ) was designed in collaboration with First Nation partners and education stakeholders to improve access to education, strengthen parent and guardian choice and improve First Nation student transitions between provincially funded and First Nation-operated or federally-operated schools in Ontario.

Recognition of First Nation schools

We are committed to supporting First Nation students and recognizing the unique nature of First Nation and federally operated schools to create opportunities for First Nation students to access programs and services to support their success and well-being.

We will build on collaboration between the provincially funded education system and First Nation-operated and Federally funded schools to further strengthen these relationships, build greater capacity and provide supports, for example, to increase access to professional development, COVID-19 supports and learning resources.

IIC Acknowledges Ontario’s Recognition of Indigenous Institutes and Investment in Indigenous Post-Secondary Education in the 2022 Provincial Budget

Posted on April 28, 2022

April 28, 2022

The Indigenous Institutes Consortium, which represents seven First Nations-led post-secondary institutions in Ontario, is proud to continue to build on its partnership with the Provincial Government to deliver high quality Indigenous post-secondary education across Ontario.

Ontario’s Indigenous Institutes play an essential role in the preservation and knowledge-sharing of Indigenous languages, traditions and culture, while meeting the needs of lifelong learners in Indigenous communities across the province.

The IIC and its Members are ready to implement the 2022 Ontario Budget which invests $9 million dollars over three years to the Indigenous Institutes operating grant to expand post-secondary program offerings including new, independently-delivered programs to train more Indigenous learners; and equitable access to capital grants for facility and infrastructure renewal.

This crucial funding comes at a time when the Indigenous Institutes are operationally ready and able to help lead the recovery of Ontario’s economy and social infrastructure in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition to providing culturally rich teaching built on the foundation of Indigenous languages, culture, and ways of knowing, IIC Member institutes offer specialized accredited programs in nursing, personal support worker, skilled trades and so much more.

“The announcement today is a step on our journey towards a relationship that lives up to the 2017 Indigenous Institutes Act and the ideals of the Treaties and breathes life into the promise of reconciliation in education,” said Rebecca Jamieson, President and CEO of Six Nations Polytechnic and Board Chair of the IIC. “Our people cannot wait any longer. We have mature governance structures and oversight. Our members need core, predictable funding to deliver programs for our learners, respond to labour market needs in our communities and help Indigenous students succeed and reach their full potential.”

“Our Member Indigenous Institute programs are unlocking access to First Nations languages and culture that was stolen from us through the Residential Schools system. The power of Indigenous post-secondary education is the impact that comes in part from taking that power back through Indigenous control of Indigenous education for the greater good in our communities and in Ontario,” said Wendelyn Johnson, Executive Director of the IIC . “As Justice Murray Sinclair famously said, ‘Education got us into this mess… and education will get us out’.”

“Indigenous post-secondary institutions that make up the IIC’s membership are ready to build on our record of success in delivering culturally relevant, Indigenous-led post-secondary education. We know that both the need and capacity for growth are there, and we are pleased to see Ontario coming to the table with the resources support that capacity to meet our communities’ vast potential,” Norma Sunday, Director of Iohahi:io Akwesasne Education and Training Institute and Vice-Chair of the Board of the IIC.

“Oshki-Wenjack applauds the provincial government for the full recognition of Indigenous Institutes in Ontario with the financial commitments announced today. Indigenous learners deserve quality, stable and culturally relevant post-secondary education that is responsive to their unique needs. Equitable resources on par with other colleges and universities is achievable,” said Lorrie Deschamps, President of Oshki-Pimache-O-Win: The Wenjack Education Institute

If this budget is not passed by the current Ontario legislature, IIC calls on all parties to make well-funded Indigenous-controlled post-secondary education a central part of their plans for Ontario.

Indigenous post-secondary institutions are mandated by their nations and are recognized through the Indigenous Institutes Act as the third pillar of the PSE education system in Ontario (along with colleges and universities). The Indigenous Institutes Consortium (IIC) represents seven post-secondary institutions in Ontario.

Since 2017, Indigenous post-secondary institutions in Ontario have received core operating funds from the provincial government delivered in a manner that respects Indigenous control over education.

For interview opportunities regarding this announcement’s implications for Indigenous education, please contact IIC Executive Director, Wendelyn Johnson at [email protected]

Follow us on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn for the latest news about the IIC and Ontario’s Indigenous Institutes. For more information and news on IIC, please visit our website .

- Français

- Contact Media

- News and Press Releases

- Counselling Centre

- Reservations

- Our Activities

- Building your BA

- Algonquin College

- Algonquin college (accelerated program)

- Augustine College

- Canadore College

- Cégep de l'Outaouais

- Cégep de Victoriaville

- Cégep du Vieux Montréal

- Collège Boréal

- Collège communautaire du Nouveau-Brunswick

- Collège Universel – Campus Gatineau

- Fleming College

- Heritage College

- Institution Kiuna

- La Cité (programme accéléré)

- Loyalist College

- Sault College

- St. Lawrence College

- Online Courses

- Micro programs

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Alumni perks and benefits

- Official Documents request

- Personnal Update form

- Alumni Association of Saint Paul University (AASPU)

- Inspiring Alumni Stories

- Get involved

- Your Giving Options

- Planned Giving

- Gifts of Securities

- Giving FAQ’s

- Guiding Transformation Together Campaign

- Campaign Cabinet

- Learning and Teaching Environments

- Indigenous Education

- Chairs and Research Centres

- Scholarships and Bursaries

- Admission Requirements

- Tuition Fees and Scholarships

- Required Documents

- Applications

- Study Permits

- Preparing for Your Stay

- What to Do When You Get Here

- Student Services

- Working in Canada

- Eligibility requirements

- Where to study

- Application form

- Required documents

- Prepare for your departure

- Return to SPU

- Visit your international office

- Prepare for your exchange

- Orientation Guide

- International Candidate Brochure

- Book a virtual meeting

- Virtual Campus Tour

- COVID-19 Updates

- Programs of Study

- Faculty - Emeritus - Adjunct

- Administrative Staff

- Professors' Expertise

- Information for Students

- Scholarly Journals, Theses and Other Publications

- Centre for Canonical Services (CCS)

- Partnership with The Broken Bay Institute (BBI), Australia

- Webinars 2023-2024

- Legal Education 2024

- Come and Meet Us

- Part Time Professors

- Seminars and Activities

- Ph.D Students in Conflict Studies

- Ph.D Students in Counselling and Spirituality

- Ph.D Students in Social Innovation

- Part-Time Professors

- Handbooks for students

- Ph.D Students

- Ph.D. in Interdisciplinary Research

- Research and Community Engagement

- Resources and Publications

- Thomas G. Feeney Q.C. Award for Aging and Community

- Importance for students

- Documentation

- About the Centre

- Publications

- Video Recordings of Previous Events

- Services for individuals

- Services for couples and families

- Other resources

- Help Request Form

- Emergency Preparedness

- University Fees and Regulations

- Tuition Fees

- Financial Information

- University Calendar

- Accident, Dental and Medical Insurance

- Writing Centre

- Documenting Your Work

- Managing Your Files

- Storage and Security

- Preserving Your Data

- Sharing and Reusing Your Data

- Research Data Management Policies

- Meeting and Event Rooms

- Catering Services

- Logistical Services

- Booking Policies

- Indigenous Initiatives Service

- A Look Inside the Centre

- IEHPs Online Program

- Webinar Series

- SPU Internships

- Preparing for an Internship

- Eligibility

- Host an Intern

- Post an Internship

- Office of Admission, Registrar and Student Services

- Office of Research and Ethics

- Our Services

- Our Chaplain

- Recruitment Office

- Upcoming activities

- Campus Tour

- Guidance Counsellors

- Become a Student Ambassador

- Research Projects

- Center's Facebook Page

- Distance Educaton

- Open Learning

- Tools and Tutorials for Students

- Tools and Tutorials for Professors

- Computer Help Request Form

- Computer Access on University Campus

- Computer Services

- Wireless Network

- Human Resources Services

- Research at SPU

- SPU Programs

- SSHRC and CIHR Annual Funding Opportunities

- Funding Agencies : other

- External Funding Agencies

- Helpful tips for external scholarships

- Search Engines

- Links to other External agencies

- Research Ethics at SPU

- Policy on Postdoctoral Appointments

- Visiting Student Researcher (VSR) Program

- Four Principles Governing the Appropriate Use of Grant Funds

- Saint Paul University Policies and Tri-Agency Guidelines

- Examples of Relevant and Non-Relevant Research Expenses

- Research Assistant

- SPU Hourly Rates

- Soft-Funded Research Bursary

- General Research Fund (GRF)

- General Graduate Studies Fund (GGSF)

- Testimonials

- Equity Diversity and Inclusion(EDI)

- Canada Research Continuity Emergency Fund (CRCEF)

- Research Policies

- Strategic Plan 2020-2025

- Partnerships

- Federal Public Service

- Coordinates

- Legislative Governance Framework of Saint Paul University

- Board of Governors

- Board Agendas and Minutes

- Vice-Rectors

- University Regulations

- Organizational Chart

- Website privacy statement

- Financial Statements

- Inclusive Pedagogies

- Annual Report

- Council of Administration

- Report on the Strategic Plan 2014–2019

- Official Documents

- LMS (BrightSpace)

- Workforce Now

- Outlook WebMail

- Job Openings

- All programs

New Pathways to Success for Indigenous Students in Post-Secondary Education

OTTAWA (Ontario), Tuesday, March 15, 2022 – Saint Paul University (SPU) is proud to collaborate with three Northern Ontario institutions on an innovative new partnership that aims to build capacity for wellness and mental health services in Indigenous communities.

SPU has worked with Oshki-Pimache-O-Win: The Wenjack Education Institute (OSHKI), Canadore College and Sault College to establish a credit transfer agreement that will allow college graduates to complete a Bachelor of Arts in Human Relations in just two years.

Students who participate in this educational pathway will be perfectly equipped to enter SPU’s Master’s in Counselling and Spirituality to become certified psychotherapists to support Indigenous communities.

As part of this partnership, students enrolled at SPU will also be able to take courses and gain hands-on community experience from the partner colleges. Through this exchange, SPU students will gain specialized education about Indigenous culture and worldviews in order to better serve Indigenous communities.

This educational pathway is an innovative approach to increase capacity for sustainable and culturally appropriate mental health and wellness services in Indigenous communities, including the 49 First Nation communities of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN).

“We recognized the increased need for specially trained mental health and wellness professionals serving Indigenous communities in the north and we are happy to fill this need with this unique program pathway. The hands-on experiences gained by students is valuable to improve positive health outcomes for the communities we serve across Nishnawbe Aski Nation.” - Lorrie Deschamps, President of Oshki-Pimache-O-Win: The Wenjack Education Institute

“Canadore College is pleased to be a part of this initiative. We have a proud commitment to Indigenous education, offering culturally sensitive and appropriate programs and services. This new pathway will improve access to additional educational opportunities for Indigenous learners, and allow them to eventually provide much-needed mental health services in their communities.” - George Burton, President and CEO, Canadore College

“This new transfer agreement is another significant milestone for Sault College and our learners. Through this collaboration, learners will have expanded options for furthering their education and the opportunity to build upon the foundational knowledge and skills gained through Sault College’s two year Social Service Worker – Indigenous Specialization program. This partnership combines the strengths of both institutions and offers learners a holistic educational experience that will greatly benefit them in their future career paths. Sault College is honoured to work with Saint Paul University and we look forward to realizing the benefits of this exciting collaboration.” - Dr. Ron Common, President, Sault College

“We are very proud to be part of this exciting new educational pathway! The exchange of knowledge and experiences between our institutions will make for a richer education experience that will help our students to support sustainable, culturally-appropriate wellness services for Indigenous communities.” - Dr. Chantal Beauvais, Rector, Saint Paul University

About Canadore College

Canadore College trains people through applied learning, leadership and innovation. It provides access to over 80 full-time quality programs, outstanding faculty, and success services to students from nearly 400 Canadian communities and 25 international countries. Approximately 1,000 students graduate from Canadore each year, and they join 48,000 alumni working across the globe.

About Oshki-Pimache-O-Win: The Wenjack Education Institute

Founded in 1996 by the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN), Oshki-Wenjack is an Indigenous post-secondary Institute committed to increasing access to accredited post-secondary education in our 49 First Nation communities, as well as Indigenous learners from across Ontario. Oshki-Wenjack’s focus is on creating a learning environment that is designed for Indigenous learners, and feels welcoming at every step along the learning journey.

About Sault College

Sault College strives to make society a better place by providing a transformative life experience through empowering those who study with us to think and learn in progressive, innovative ways, including those we have not yet imagined. With enthusiastic staff, small class sizes and a student-to-faculty ratio lower than the provincial average, Sault College students learn in a supportive environment.

About Saint Paul University

Founded in 1848, Saint Paul University is an institution steeped in tradition with values focused on creating a more just and humane future. With programs specialized in human and social sciences, Saint Paul University seeks to drive positive social change and empower communities through research and innovation. For more information, please visit ustpaul.ca.

For more information, please contact: Julie Bourassa Communications Officer, Saint Paul University 613-236-1393, ext. 2310 [email protected]

Other Links

- Professor Publications Celebrated During Collective Book Launch

- Message from the Rector to the Saint Paul University Community

- Saint Paul University and Administrative Staff Sign New Collective Agreement, Ratify the Variable Work Week

- SPU Goes Blue : A Pledge for Water Sustainability and Access

- Demographics Survey

- Donate Online

- Employee directory

- Working at SPU

BECOME A STUDENT

- Undergraduate admissions

- Graduate admissions

- Distance Learning

- Financial Aid and Bursaries

- International

UNDERGRADUATE

- Anglican Studies

- Conflict Studies

- Eastern Christian Studies

- Human Relations and Spirituality

- Philosophy of Religion

- Ethics and Contemporary Social Issues

- Social Communication

- Social Innovation

- Counselling and Spirituality

- Leadership, Ecology and Equity

- Campus Tours

- Information Request

- Student for a day

Website by Distantia

- Annual Ontario School Survey

- Right To Education

- Continuum of Learning

- Pan-Canadian Youth Network

- 2022 Summit

- PFE Articles

- Media Releases

- Policy scans & trackers

- Book a Speaker

- Public education in Ontario

- Parent tip sheets

- Strategic Plan

A progress report on Indigenous education in Ontario's publicly funded schools

New report by People for Education shows that publicly funded schools in Ontario have made significant progress towards Indigenous education over the last decade but we still have a long way to go to fulfill the education-related Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Introduction

1. truth and reconciliation commission calls to action for education and youth, 2. ontario’s response to the calls to action related to education, 3. professional development on indigenous education an increasingly common starting point, 4. increase in secondary schools offering and mandating indigenous studies courses, 5. more ontario schools working with indigenous guest speakers, elders, and knowledge keepers, 6. community consultations and partnerships are integral to advancing indigenous education, 7. incorporating indigenous cultures, ways of knowing, teachings, and language, 8. access to indigenous education differs by region and level of schooling, conclusion and recommendations, appendix: methodology, bibliography.

Findings from People for Education’s 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS) indicate that Ontario’s publicly funded schools are showing signs of progress in response to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Calls to Action for education.

It has been eight years since the TRC issued its Calls to Action to support reconciliation in Canada, with Calls to Action 6-12 and 62-66 specifically addressing children, youth, and education. While some progress has been made, a recent report from the Yellowhead Institute found that only 13 of the 94 Calls to Action have been fully implemented, and none of these completed calls are those focused on education. 1

Using data from People for Education’s annual survey, based on responses from 1,044 schools across all the province’s 72 publicly funded school boards, this report provides an overview of how Ontario is doing in response to the TRC’s Calls to Action for education, and the progress Ontario schools have made on implementing Indigenous education strategies and programs over the last decade.

These findings focus only on provincially funded schools in Ontario school boards, and do not include First Nations schools located on reserves. According to the Ministry of Education, more than 80% of Indigenous students attend provincially funded schools. 2 So, while this report does not provide information about First Nations education on reserves, it does offer insight about the progress of Indigenous education programs in provincially funded schools which are attended by the vast majority of Indigenous and non-Indigenous students in the province.

According to The Honourable Murray Sinclair, Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, education has a key role to play in long-term reconciliation, and changes in our education systems must include improvements in the education of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous students.

“Education is what got us into this mess — the use of education in terms of residential schools — but education is the key to reconciliation. We need to look at the way we are educating children. That’s why we say that this is not an Aboriginal problem. It’s a Canadian problem.” 3 Justice Murray Sinclair, Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

It is important to recognize that there is much diversity within First Nation, Métis, and Inuit communities in Ontario. Please note that the use of the term “Indigenous” in this report refers to all the distinct cultures, nations, and individuals within First Nation, Métis, and Inuit populations living in the province.

Quick Facts

Figure 1. Truth and Reconciliation Commission Calls to Action pertaining to education and young people

Over the last 16 years, Indigenous education policy in Ontario has been punctuated by a number of reports, frameworks, goals, and changes to funding.

In 2007, Ontario launched its First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework. The Framework outlined two targets to be achieved by 2016: improving achievement among First Nation, Métis, and Inuit students and closing gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous students in literacy and numeracy scores, graduation rates, and advancement to post-secondary education. At the same time, the province acknowledged the importance of having accurate data to track whether these goals were being achieved. To that end, the Ministry of Education released guidelines to support school boards in developing a voluntary, confidential self-identification process for Indigenous students. 4

Nearly a decade after the release of the 2007 Policy Framework, the Ontario government released The Journey Together: Ontario’s Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples. The 2016 strategy emphasized a commitment to “address the legacy of residential schools, close gaps and remove barriers, support Indigenous culture, and reconcile relationships with Indigenous peoples.” 5

In 2017, in a further step toward reconciliation, and in response to Calls to Action 62 and 63 from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the province made a commitment to revise the Ontario curriculum by fall 2018 so that it would include mandatory Indigenous-focused content for grades 4, 5, and 6 Social Studies and grades 7, 8, and 10 History. 6

Four years later, a new Ontario government reiterated previous governments’ commitments to work with Indigenous partners to support First Nation, Métis, and Inuit student achievement and wellbeing by closing the achievement gap and increasing every student’s knowledge of Indigenous perspectives, histories, and cultures. 7 The 2021 announcement included a plan to work with Indigenous partners to add mandatory Indigenous-focused curriculum to Social Studies for grades 1-3 by September 2023. The content was to focus on the role of family and resilience in First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities, Indigenous historical and contemporary realities, Indigenous peoples’ connection with the land, the residential school system, and the reclamation of identity, language, culture, and community connections. 8 As of April 2023, the revamped curriculum had not yet been released.

Science curriculum unilaterally changed

In the spring of 2022, the province released new Science and Technology Curriculum for grades 1-8. However, despite having worked with Indigenous partners on the curriculum, the government made a unilateral decision to remove or substantially modify sixteen Indigenous-related expectations in the curriculum just three weeks before its release. 9 For example, the original curriculum explicitly named that students would “explore real-world issues by connecting Indigenous sciences and technologies and Western science and technology, using ways of knowing such as the Two-Eyed Seeing approach…”. This approach allows an understanding of science that includes both Western and Indigenous perspectives. Instead, the final version generally states that students will “analyze science and technology contributions from various communities.” 10

Slow progress on data collection

Data collection forms a key component of both the Calls to Action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and the recommendations from the UN on Canada’s lack of progress in implementing the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. 11 Without data, and in particular, race-based data, it is impossible to know if numerous policy goals are being met. 12 While school boards in Ontario are now required to collect race-based data (as of 2023), it is not yet clear whether this work has been completed. Likewise, through school boards have been encouraged to implement voluntary, confidential Indigenous self-identification initiatives since 2007, it remains difficult to find out what progress has been made.

In the 2022-23 school year, Ontario’s Ministry of Education allocated $120.5 million in the Indigenous Education Grant, intended to fund “programs and initiatives to support the academic success and well-being of Indigenous students, as well as build the knowledge of all students and educators on Indigenous histories, cultures, perspectives and contributions.” 13 The funding is allocated to school boards based on their total enrolment, the number of students in Indigenous studies and language programs, and the number of students who have self-identified as Indigenous. However, since Ontario appears to be behind in its collection and reporting of race-based and Indigenous student data, it is not clear if funding is being allocated where it is most needed.

“We want to do more but need help and direction with what to do and how to do it.” Elementary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

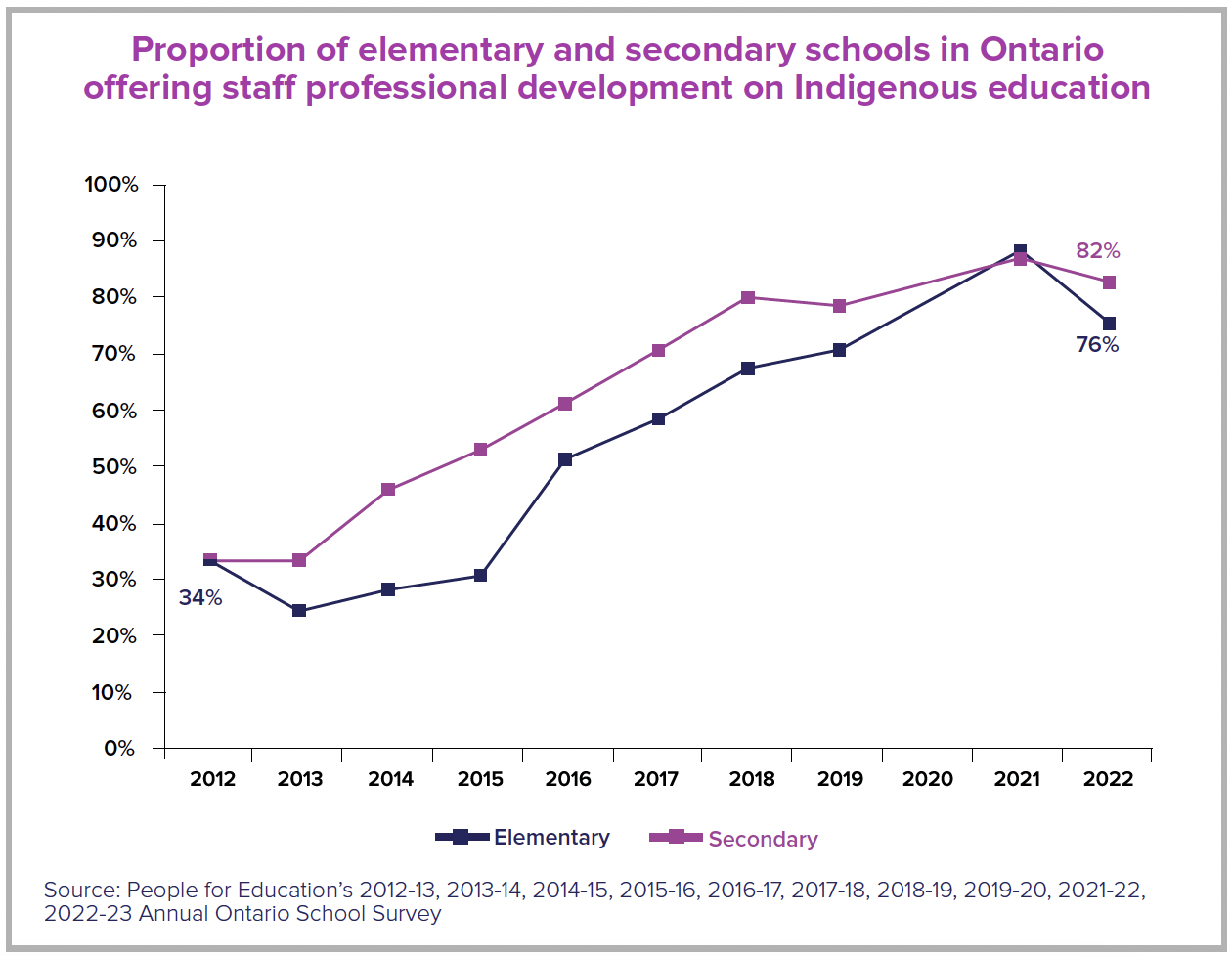

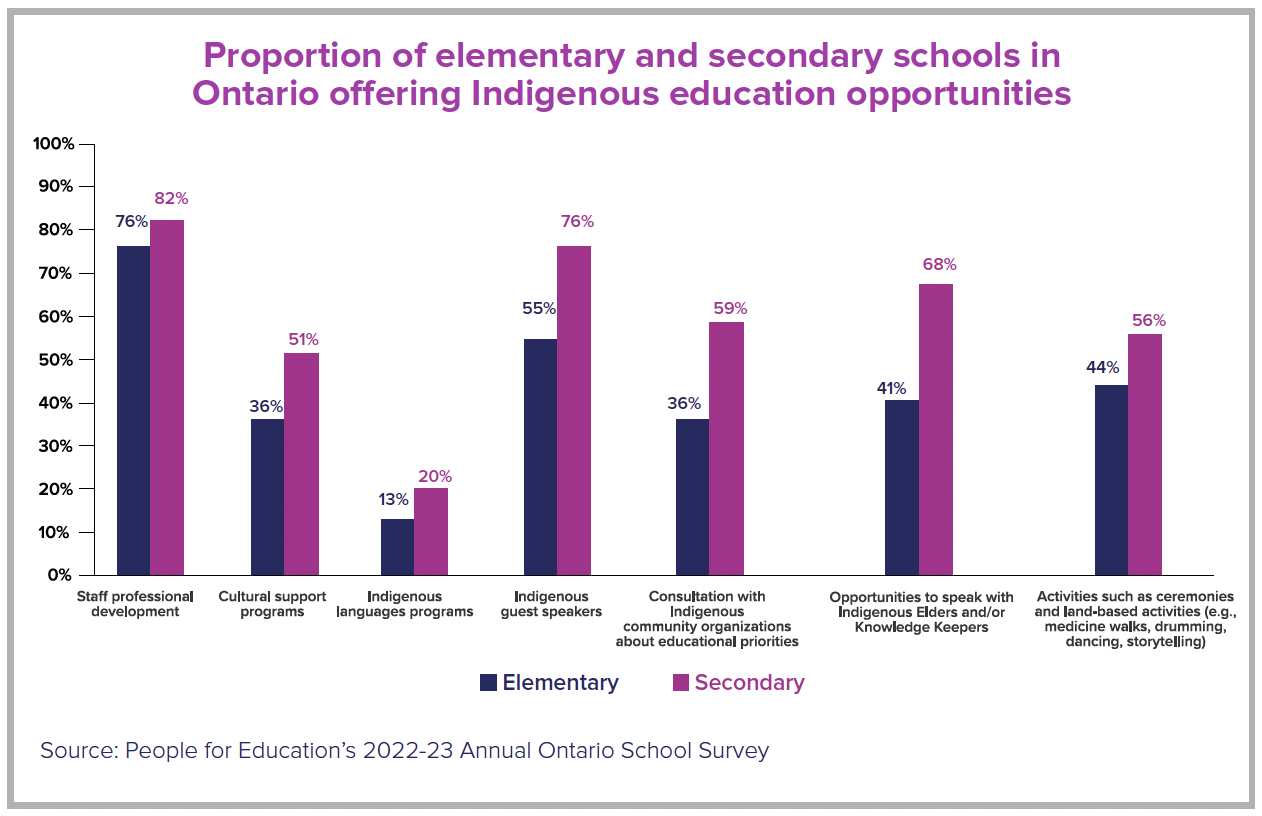

Staff professional development is essential to effectively incorporating Indigenous histories and curriculum in classrooms (i.e., Calls to Action 62 and 63). Professional development was the most reported Indigenous education opportunity offered across the province’s publicly funded elementary (76%) and secondary (82%) schools. The proportion of schools reporting professional development for school staff has more than doubled for elementary (34% in 2012 to 76% in 2022) and secondary schools (34% in 2012 and 82% in 2022) over the last decade.

Figure 2. Proportion of elementary and secondary schools in Ontario offering staff professional development on Indigenous education, 2012-2013 to 2022-2023

In their responses to the AOSS 2022-23, principals often cited the value of professional development on Indigenous education. Principals noted that a supportive school board that prioritizes Indigenous education, along with having a dedicated staff member in school leading the work, were valuable when offering staff professional development opportunities.

“Having a System Principal of Indigenous Rights and Education has really helped to ensure that we have open communication between our Treaty Partner and the board, and this is translating into better services and understanding at the school level.” Elementary school principal, GTA

Some barriers mentioned by principals included finding the time for professional development, competing priorities with other equity focuses, and staff or board hesitancy or discomfort with Indigenous-focused content.

“Time and priority. With so little staff meeting time and the focus for those being on math and literacy instruction, there is no time to run staff PD for Indigenous studies. We cannot have PLC [professional learning community] time as we are unable to get supply coverage.” Elementary school principal, Eastern Ontario “People are interested in doing the work but are fearful at times about offending members of the Indigenous community. We need to continue to build partnerships and have representation in the work that we do.” Secondary school principal, GTA

In February 2023, the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) joined a growing list of school boards in the province who are making the shift to replace the compulsory grade 11 English course (i.e., ENG3U/C/E) with an Indigenous-focused course centered on First Nations, Métis, and Inuit voices (i.e., NBE3U). 14 The course, titled Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Voices, is currently offered as an alternative English course, along with other optional Indigenous-focused courses for secondary school students, in the revised 2019 Ontario Curriculum grades 9 to 12 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies. 15 For French-language schools, this change would mean replacing the grade 11 French course (i.e., FRA3U/C/E) with the course titled, Découvrir les vois contemporaines des Premières Nations, des Métis et des Inuits (i.e., NBF3U).

Figure 3. Ontario school boards who have mandated the grade 11 English course, NBE3U: Understanding Contemporary First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Voices (February 2023)

Figure 3 lists the 32 school boards in Ontario who have mandated NBE3U as of February 2023. A handful of other boards are also in the process of following suit. For example, Halton District School Board (HDSB) and Waterloo Region District School Board (WRDSB) have plans in place to mandate NBE3U by the beginning of the upcoming 2023-2024 school year. 16

Some schools who participated in AOSS 2022-23 have chosen to offer the Indigenous studies course NBE3U as the only option for students’ grade 11 compulsory English credit despite it not being mandated by their board. Many of these principals noted that the Indigenous studies courses offered were popular with students and generally supported by the school community, although some said that they experienced resistance to the course. A secondary school principal in Central Ontario reported that, “It is sometimes challenging to get all students/families to recognize the importance of this learning. For instance, we are offering only the NBE courses for Gr. 11 English and we have experienced some resistance from the school community.”

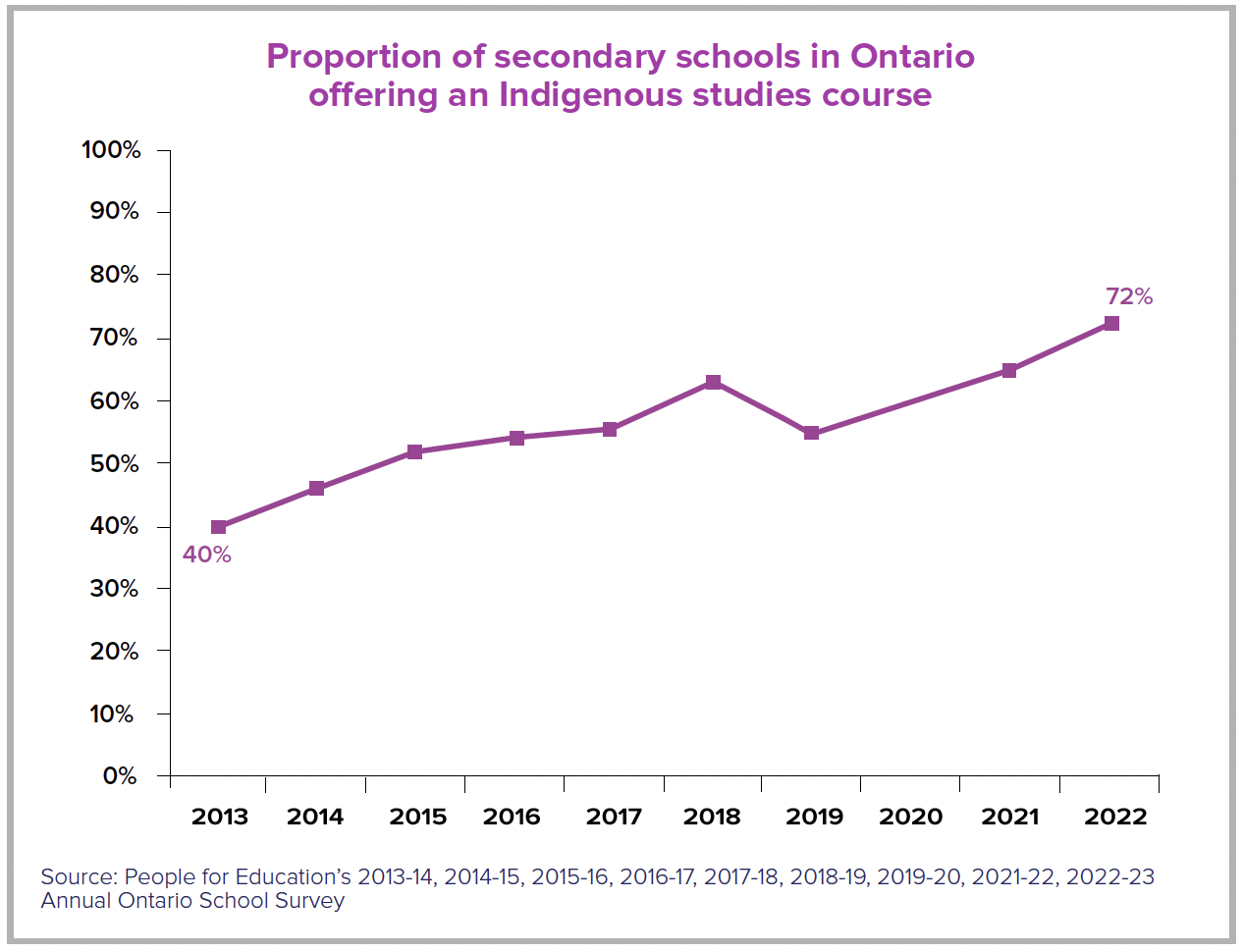

Longitudinal AOSS data shows that the proportion of secondary schools offering any Indigenous studies course rose from 40% in 2013 to 72% in 2022, indicating Ontario secondary schools have made significant progress on incorporating Indigenous-focused courses over the past decade, and as more school boards make plans to mandate NBE/NBF3U, that growth will likely continue.

Figure 4. Proportion of secondary schools in Ontario offering an Indigenous studies course (e.g., NBE/ NBF3U), 2013-2014 to 2022-2023

“Our district has great partnerships with local Indigenous knowledge keepers and our students and staff have lots of opportunities to learn from them.” Elementary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

In the TRC’s Calls to Action, Call 63 includes a focus on building student capacity for intercultural understanding, empathy, and mutual respect. 17 Prioritizing opportunities for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis guest speakers, Elders, and Knowledge Keepers to visit and develop relationships with Ontario schools is vital to build this capacity in students as it provides students with access to Indigenous perspectives and cultures. In 2022-23, 41% of elementary schools and 68% of secondary schools reported offering opportunities to talk with Indigenous Elders and/or Knowledge Keepers. Moreover, the proportion of schools reporting that they had Indigenous guest speakers rose significantly over the last decade, increasing from 23% in 2012 to 55% in 2022 for elementary schools and from 41% in 2012 to 76% in 2022 for secondary schools.

Figure 5. Proportion of elementary and secondary schools in Ontario offering Indigenous guest speakers, 2012-13 to 2022-23

Beyond having Indigenous guest speakers, principals talked about the importance of creating extended opportunities for Indigenous Elders, speakers, and Knowledge Keepers to build relationships with their students and school communities through a range of activities. They said that staff and students greatly benefited from learning with them. A secondary school principal from Eastern Ontario reported, “We have a resident Knowledge Keeper who builds canoes and wigwams. Our students are learning through building, creating and storytelling.”

On the other hand, not all principals said that they had access to these individuals, with some saying that they did not have enough board support, funds, or community partnerships to facilitate these relationships. One elementary school principal from Southwestern Ontario wrote that, “Some people are able to access money for guest speakers and other opportunities, but it is not universal.”

There have been steady increases over the last decade in the proportion of schools offering the Indigenous education opportunities that People for Education asks about on the AOSS. However, in the AOSS 2022-23, principals called attention to some areas where more work needs to be prioritized: community consultations and partnerships, offering cultural support programs, and support for resources and teacher training.

“We work hard at our relationships with our Indigenous partners and families and look for opportunities to learn together.” Elementary school principal, Northern Ontario

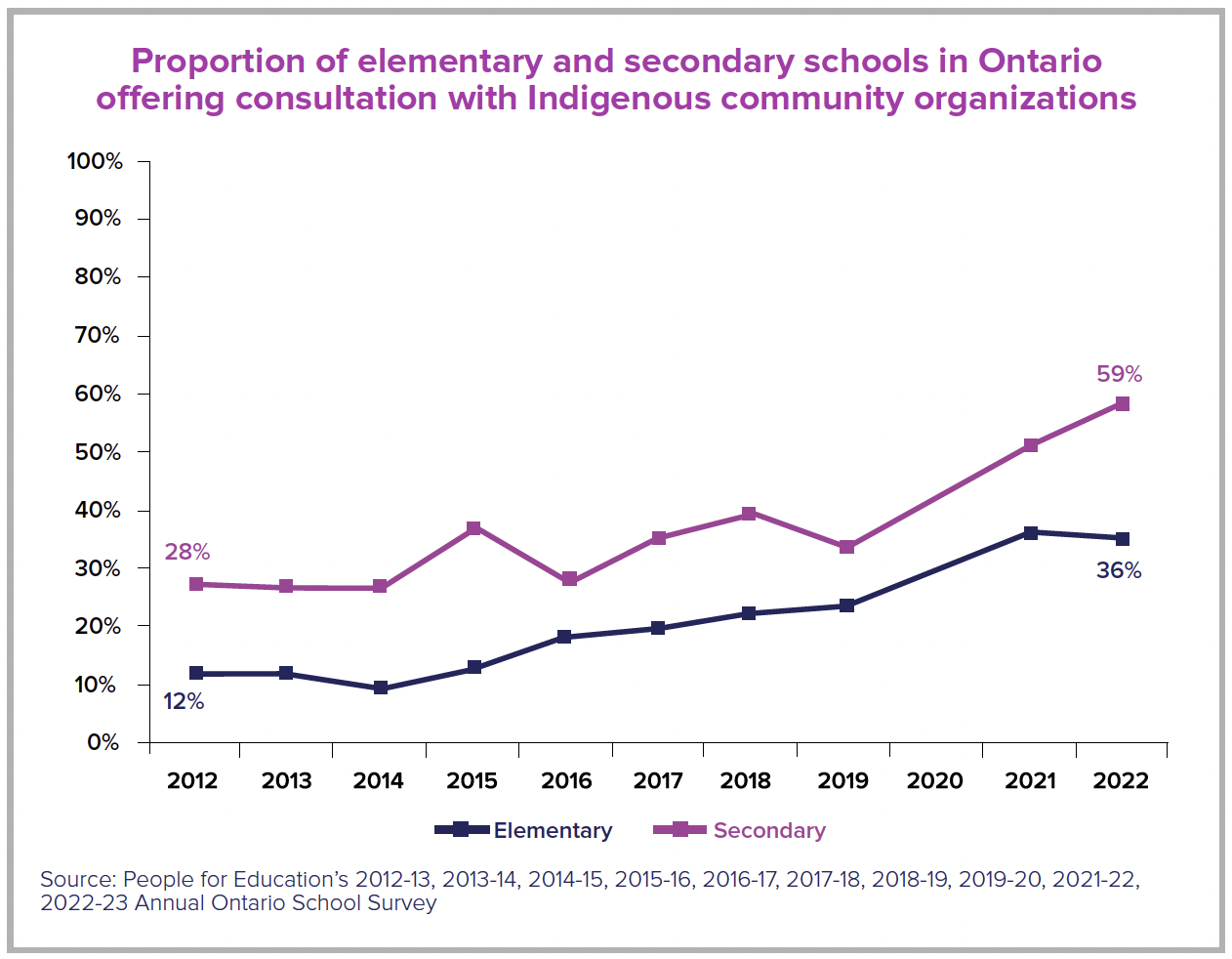

Strong relationship building between First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities and non-Indigenous communities, consultation with Indigenous communities about educational priorities, and partnerships with Indigenous community organizations are all key to responding to the TRC’s Calls to Action for education. The proportion of elementary schools that offer consultation with Indigenous community organizations about education priorities rose from 12% in 2012 to 36% in 2022, while secondary schools saw an increase from 28% in 2012 to 59% in 2022.

Figure 6. Proportion of elementary and secondary schools in Ontario offering consultation with Indigenous community organizations about educational priorities, 2012-13 to 2022-23

“We have connected with some families who are sharing their expertise, for example, developing a display of Indigenous resources in the library, smudging ceremony, outdoor learning, grandfather teachings.” Elementary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

While some principals reported that their schools had strong partnerships with local Indigenous communities, others said they were still working on building community relationships or noted that they needed support from their school board as well as the Ministry of Education to do this work. Principals also told us that relationships with Indigenous students’ families were sources of connection to and learning about Indigenous perspectives, teachings, and cultures.

“We have a partnership with [name of Indigenous community]. Their program lives in our school, with an Indigenous Youth Outreach Worker providing mentorship opportunities, in-school math and literacy supports, in-school and after school cultural programming and nutritional supports. We collaborate to celebrate an annual powwow, a true highlight at our school. Our Ojibwe Language program continues to grow with an increasing number of students opting to take Ojibwe instead of French as a Second Language each year. Educational staff are open to learning and to providing land-based learning opportunities for students.” Elementary school principal, Northern Ontario

The TRC’s Calls to Action for education are not only important to support the Indigenous youth in our schools, but also to educate non-Indigenous students about residential schools and Indigenous culture, history, and ways of knowing. It is important that Indigenous students see themselves reflected in their education, and that they feel that their communities and cultures are valued and connected to school. 18

Offering cultural support programs in schools not only provides a valuable resource to Indigenous students, but they also help to integrate Indigenous perspectives more holistically in the school community. Cultural support programs include things like creating an Indigenous-focused student success team or dedicating an Indigenous space like a smudge room or garden on school property.

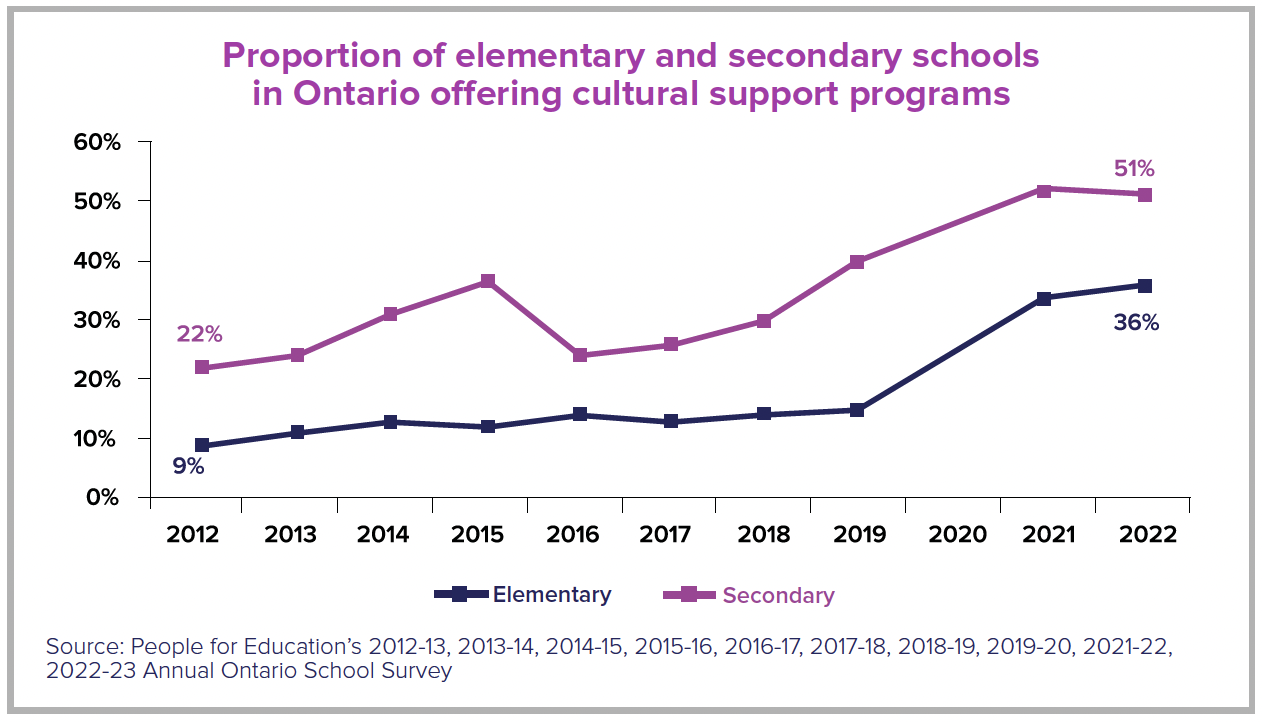

The proportion of elementary schools reporting that they offer cultural support programs rose from 9% in 2012 to 36% in 2022; for secondary schools, the proportion of schools offering cultural support programs increased from 22% in 2012 to 51% in 2022. These are significant increases over the past decade, but cultural support programs were still one of the least reported Indigenous education opportunities compared to all other opportunities.

Figure 7. Proportion of elementary and secondary schools in Ontario offering cultural support programs, 2012-13 to 2022-23

Another way Ontario schools are working to support Indigenous students is through offering activities such as ceremonies and land-based activities like drumming, dancing, medicine walks, and storytelling. These activities support Indigenous students by connecting the school community to Indigenous students’ families and communities outside the school and help to incorporate Indigenous cultures and ways of knowing more holistically in the school community through experiential learning for all students, Indigenous and non-Indigenous.

“We have an Outdoor Education program for all primary students that focuses on looking at the land we live on through an Indigenous lens. One of the parents on our grounds & greening committee (which manages a teaching garden & works with the outdoor ed teacher) is Indigenous and helps us to reflect & question.” Elementary school principal, GTA

In 2022-23, 44% of elementary schools and 56% of secondary schools reported that they offer activities such as ceremonies and land-based activities (e.g., medicine walks, drumming, dancing, storytelling).

Principals also listed various ways in which their schools were working to support Indigenous students and incorporate Indigenous cultures and teachings holistically. One school installed a courtyard healing circle. A few principals mentioned that their school had a smudge room or smudging retreats. Others said that students had opportunities to participate in experiential learning, Indigenous cooking, gardening, land-based activities, storytelling, art, and the Seven Grandfather Teachings.

“We have been able to collaborate in an amazing whole-school living reconciliation on important lands and learning to integrate circles, treaties, and relationships with each other and the land by learning from Indigenous educators and Elders.” Elementary school principal, Southwestern Ontario

Indigenous Languages Programs

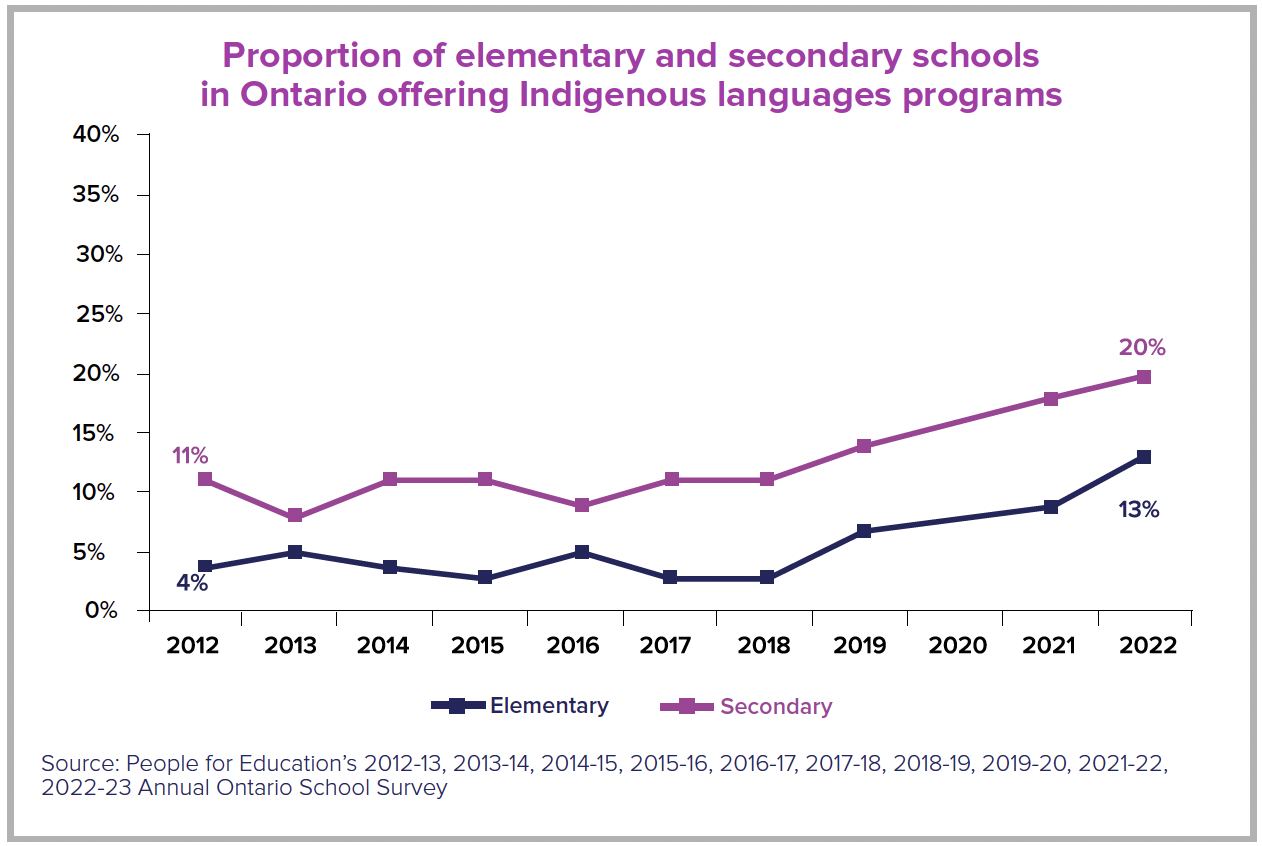

Offering an Indigenous languages program in school is another way Ontario elementary and secondary schools can support Indigenous students. The TRC’s Call to Action 10 calls for protecting the right to Aboriginal languages, which includes the teaching of Aboriginal languages as credit courses in school, along with a commitment to sufficient funding in this area. 19

In 2022-23, the least reported Indigenous education opportunity was Indigenous languages programs for both elementary (13%) and secondary schools (20%). Although they were the least reported education opportunity, the proportion of schools reporting it still increased from 2012 to 2022 (from 4% to 13% for elementary schools and from 11% to 20% for secondary schools).

In the 2022-23 AOSS, principals said that they wanted to offer Indigenous languages courses, with some mentioning that it was challenging to find a qualified Indigenous languages teacher. Funding was mentioned by principals as another major barrier to offering Indigenous languages programming in school.

Figure 8. Proportion of elementary and secondary schools in Ontario offering Indigenous languages programs, 2012-2013 to 2022-2023

“We have a large percentage of Indigenous students. I would like to offer NSL [Native as a Second Language], but we cannot secure a native speaker to teach this course.” Elementary school principal, Northern Ontario “Finding a language speaker to take on our Anishnaabemowin class on a consistent basis has been a significant barrier.” Elementary school teacher, Southwestern Ontario

In 2022-23, secondary schools were more likely than elementary schools to offer Indigenous education opportunities. The biggest differences between elementary and secondary schools were in the proportions of schools that reported offering opportunities to speak with Indigenous Elders and/or Knowledge Keepers (41% of elementary schools compared to 68% of secondary schools), consultation with Indigenous community organizations about educational priorities (36% of elementary schools compared to 59% of secondary schools), and Indigenous guest speakers (55% of elementary schools compared to 76% of secondary schools).

Figure 9. Proportion of elementary and secondary schools in Ontario offering Indigenous education opportunities, 2022-2023

Moreover, there are regional differences in Indigenous education opportunities across the province. Generally, schools in Northern Ontario were more likely to offer Indigenous education opportunities, while schools in the GTA were least likely to offer these opportunities. While some responses from schools in Northern Ontario highlighted serving larger populations of Indigenous students, recent data from Statistics Canada show that the Indigenous population living in large urban population centres has grown by 12.5% from 2016 to 2021. 20

Figure 10. Proportion of Ontario schools offering Indigenous education opportunities, by region, 2022-2023

The largest differences regionally were in the proportion of schools that offered cultural support programs (55% of Northern Ontario schools compared to 25% of GTA schools), Indigenous languages programs (37% of Northern Ontario schools compared to 5% of GTA schools), and activities such as ceremonies and land-based activities (72% of Northern Ontario schools compared to 30% of GTA schools). On the other hand, secondary schools in Northern Ontario (61%) were least likely to offer an Indigenous studies course compared to secondary schools in Central Ontario (82%), Southwestern Ontario (81%), the GTA (73%), and Eastern Ontario (71%).

There is more work to be done for Truth and Reconciliation in education

People for Education’s latest findings illustrate that progress has been made in the past decade to advance Indigenous education across publicly funded schools in Ontario, but overall, Canada still has a long way to go in completely fulfilling the TRC’s eleven Calls to Action regarding education. These Calls to Action emphasize the importance of informed consent, full participation, consultation, and collaboration with Indigenous peoples; all components that require building partnerships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples. So, while commitments to work together in the form of public statements and policy documents such as school curriculum are a critical first step, they alone are not enough for truth and reconciliation.

To move forward in supporting the TRC’s Calls to Action regarding education and young people, People for Education has three recommendations for the Ontario Ministry of Education:

Mandate the NBE/NBF3U Indigenous studies course in place of grade 11 English/French at the provincial level, and increase the number of elementary and secondary schools offering Indigenous languages and programs by providing funding and resources for:

The recruitment, hiring, and retention of Indigenous education workers and teachers, in collaboration with school boards and post-secondary faculties of education.

Frequent, timely, and meaningful professional development opportunities to support educators in implementing Indigenous education.

Improved data collection and reporting on the status, experience, and outcomes of Indigenous students.

Provide dedicated funding for positions in schools, boards, and government that are focused on promoting and supporting effective programs on Indigenous languages and ways of knowing more holistically from kindergarten to grade 12.

Convene a taskforce of diverse and regionally reflective Indigenous educators and Elders to support the Ministry of Education and the 72 publicly funded school boards across Ontario in responding to the Calls to Action regarding education and young people. Activities would include the co-development of curriculum and updating the Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework that was originally published in 2007. 21

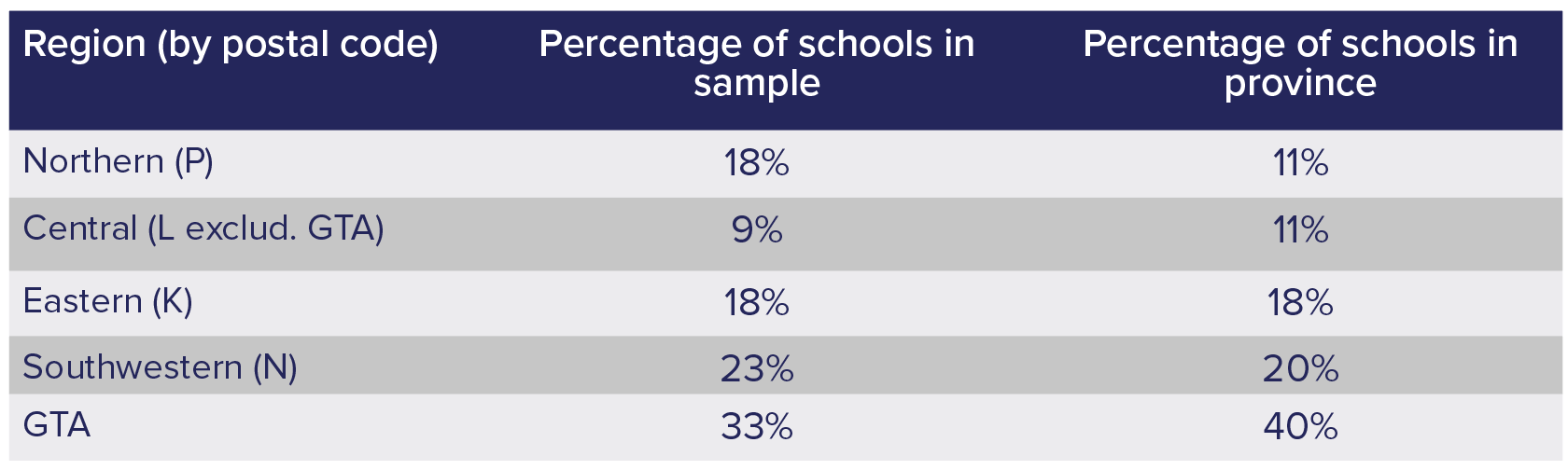

This report is based on data from 1,044 schools from all 72 publicly funded Ontario school boards that participated in the 2022-23 Annual Ontario School Survey (AOSS). Longitudinal data comparisons are based on the data collected from the elementary and secondary schools that participated in People for Education’s 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15, 2015-16, 2016-17, 2017-18, 2018-19, 2019-20, and 2021-22 AOSS. Unless cited from other sources, the statistics and quoted material in this report originate from People for Education’s 2022-23 AOSS, the 26th annual survey of elementary schools, and the 23rd annual survey of secondary schools in Ontario. Surveys from the 2022-23 AOSS were completed online via SurveyMonkey in both English and French in the fall of 2022. Survey responses were disaggregated to examine survey representation across provincial regions (see table below). Schools were sorted into geographical regions based on the first letter of their postal code. The GTA region includes schools with M postal codes as well as those with L postal codes located in GTA municipalities. 22

Figure 11. Survey response representation by region, all schools, 2022-2023

Qualitative data analysis was conducted using inductive analysis. Researchers read responses and coded emergent themes in each set of data (i.e., the responses to each of the survey’s open-ended questions). The quantitative analyses in this report are based on descriptive statistics. The primary objective of the descriptive analyses is to present numerical information in a format that is accessible to a broad public readership. All data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. All calculations have been rounded to the nearest whole number and may not total 100% in displays of disaggregated categories. All survey responses and data are kept confidential and stored in conjunction with TriCouncil recommendations for the safeguarding of data.

People for Education acknowledges the absence of Indigenous research methodologies in this report, specifically the missing perspectives and lived experiences of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities. Building partnerships and working in collaboration with Indigenous communities is an area of improvement where our organization is committed to growing in the future.

For questions about the methodology used in this report, please contact the research team at People for Education: [email protected] .

1 Yellowhead Institute. 2022. “Calls to Action Accountability: A 2022 Status Update on Reconciliation.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/TRC-Report-12.15.2022-Yellowhead-Institute-min.pdf .

2 Ontario Ministry of Education. 2018. “Strengthening Our Learning Journey Third Progress Report on the Implementation of the Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework.” Accessed March 3, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-ieo-third-progress-report-en-2021-10-28.pdf , p. 19, citing preliminary OnSIS enrollment data for October 2015.

3 Watters, Haydn. 2015. “Truth and Reconciliation chair urges Canada to adopt UN declaration on Indigenous Peoples.” CBC News, June 1, 2015. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/truth-and-reconciliation-chair-urges-canada-to-adopt-un-declaration-on-indigenous-peoples-1.309622.

4 Ontario Ministry of Education. 2007. “Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework.” Accessed March 17, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-ontario-first-nation-metis-inuit-education-policy-framework-2007-en-2021-10-29.pdf ; Ontario Ministry of Education. 2007. “Building Bridges to Success for First Nation, Métis and Inuit Students.” Accessed April 4, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-building-bridges-to-success-first-nation-metis-inuit-students-en-2021-10-21.pdf .

5 Government of Ontario. 2016. “The Journey Together: Ontario’s Commitment to Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.” Accessed February 23, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/trc_report_web_mar17_en_1.pdf .

6 Johnson, Rhiannon. Nov 8, 2017. “Indigenous history, culture now mandatory part of Ontario curriculum”. CBC News. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenous-history-culture-mandatory-ontario-curriculum-1.4393527 .

7 Government of Ontario. 2021. “Indigenous education in Ontario.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://www.ontario.ca/page/indigenous-education-ontario .

8 Government of Ontario. 2021. “Ontario to Strengthen Mandatory Indigenous Learning in School Curriculum.” September 29, 2021. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1000904/ontario-to-strengthen-mandatory-indigenous-learning-in-school-curriculum.

9 McInnes, Angela. 2022. “Ontario science and tech curriculum shifts focus from Indigenous framework to economy, educators say.” CBC News, July 23, 2022. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/ontario-science-and-tech-curriculum-shifts-focus-from-indigenous-framework-to-economy-educators-say-1.6527820 .

10 Alphonso, Caroline. 2022. “Indigenous science framework removed from Ontario elementary school curriculum.” The Globe and Mail, July 2, 2022. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/article-indigenous-science-framework-removed-from-ontario-elementary-school/ .

11 People for Education. 2022. “30 years with insufficient progress on child well-being.” Accessed April 4, 2023. https://peopleforeducation.ca/our-work/30-years-with-insufficient-progress-on-child-well-being/ .

12 Ontario Ministry of the Solicitor General. 2020. “Annual progress report 2020: Ontario’s Anti-Racism Strategic Plan.” Accessed April 4, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/solgen-annual-progress-report-2020-anti-racism-strategic-plan-en-2020-09-20-v2.pdf.

13 Ontario Ministry of Education. 2022. “Education Funding: Technical Paper 2022–23.” Accessed April 4, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-2022-23-technical-paper-en-2022-03-15.pdf .

14 Toronto District School Board. 2023. “TDSB Approves Mandatory Indigenous Education in Grade 11.” February 1, 2023. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Home/ctl/Details/mid/42863/itemId/66

15 Ontario Ministry of Education. 2019. “The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9 to 12 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies.” Accessed February 23, 2023. https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com/fbd574c4-da36-0066-a0c5-849ffb2de96e/e5733b4c-80ae-4988-8ab4-d29ae1cbaae2/First-nations-metis-inuit-studies-grades-9-12.pdf .

16 Halton District School Board. 2021. “Student Voices Student Experiences of Racism & HDSB’s Strengthened Commitments to Anti-Racism.” Accessed March 1, 2023. https://www.hdsb.ca/our-board/Documents/Student-Voices-HDSB-Response-to-Racism.pdf#search=NBE ; Waterloo Region District School Board. 2022. “Director’s Response Strategic Plan.” Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.wrdsb.ca/learning/strategic-plan/directors-response/.

17 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf .

18 Ontario Ministry of Education. 2017. “Ontario’s Education Equity Action Plan.” Accessed March 3, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-1_0/edu-Ontario-Education-Equity-Action-Plan-en-2021-08-04.pdf.

19 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf .

20 Statistics Canada. 2022. “Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed.” September 21, 2022. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921a-eng.htm .

21 Ontario Ministry of Education. 2007. “Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework.” Accessed March 17, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-ontario-first-nation-metis-inuit-education-policy-framework-2007-en-2021-10-29.pdf.

22 City of Toronto. n.d. “City Halls – GTA Municipalities and Municipalities Outside of the GTA.” Accessed February 28, 2022. https://www.toronto.ca/home/311-toronto-at-your-service/find-service-information/article/?kb=kA06g000001cvbdCAA.

Government of Ontario. 2021. “Ontario to Strengthen Mandatory Indigenous Learning in School Curriculum.” September 29, 2021. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://news.ontario.ca/en/release/1000904/ontario-to-strengthen-mandatory-indigenous-learning-in-school-curriculum

Halton District School Board. 2021. “Student Voices Student Experiences of Racism & HDSB’s Strengthened Commitments to Anti-Racism.” Accessed March 1, 2023. https://www.hdsb.ca/our-board/Documents/Student-Voices-HDSB-Response-to-Racism.pdf#search=NBE.

Johnson, Rhiannon. 2017. “Indigenous history, culture now mandatory part of Ontario curriculum”. CBC News, Nov 8, 2017. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/indigenous-history-culture-mandatory-ontario-curriculum-1.4393527

McInnes, Angela. 2022. “Ontario science and tech curriculum shifts focus from Indigenous framework to economy, educators say.” CBC News, July 23, 2022. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/london/ontario-science-and-tech-curriculum-shifts-focus-from-indigenous-framework-to-economy-educators-say-1.6527820

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2007. “Building Bridges to Success for First Nation, Métis and Inuit Students.” Accessed April 4, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-building-bridges-to-success-first-nation-metis-inuit-students-en-2021-10-21.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2007. “Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework.” Accessed March 17, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-ontario-first-nation-metis-inuit-education-policy-framework-2007-en-2021-10-29.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2017. “Ontario’s Education Equity Action Plan.” Accessed March 3, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-1_0/edu-Ontario-Education-Equity-Action-Plan-en-2021-08-04.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2018. “Strengthening Our Learning Journey Third Progress Report on the Implementation of the Ontario First Nation, Métis, and Inuit Education Policy Framework.” Accessed March 3, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-ieo-third-progress-report-en-2021-10-28.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2019. “The Ontario Curriculum Grades 9 to 12 First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies.” Accessed February 23, 2023. https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com/fbd574c4-da36-0066-a0c5-849ffb2de96e/e5733b4c-80ae-4988-8ab4-d29ae1cbaae2/First-nations-metis-inuit-studies-grades-9-12.pdf

Ontario Ministry of Education. 2022. “Education Funding: Technical Paper 2022–23.” Accessed April 4, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/edu-2022-23-technical-paper-en-2022-03-15.pdf

Ontario Ministry of the Solicitor General. 2020. “Annual progress report 2020: Ontario’s Anti-Racism Strategic Plan.” Accessed April 4, 2023. https://files.ontario.ca/solgen-annual-progress-report-2020-anti-racism-strategic-plan-en-2020-09-20-v2.pdf

People for Education. 2022. “30 years with insufficient progress on child well-being.” Accessed April 4, 2023. https://peopleforeducation.ca/our-work/30-years-with-insufficient-progress-on-child-well-being/

Statistics Canada. 2022. “Indigenous population continues to grow and is much younger than the non-Indigenous population, although the pace of growth has slowed.” September 21, 2022. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/220921/dq220921a-eng.htm

Toronto District School Board. 2023. “TDSB Approves Mandatory Indigenous Education in Grade 11.” February 1, 2023. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.tdsb.on.ca/Home/ctl/Details/mid/42863/itemId/66

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. 2015. “Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Waterloo Region District School Board. 2022. “Director’s Response Strategic Plan.” Accessed March 8, 2023. https://www.wrdsb.ca/learning/strategic-plan/directors-response/

Watters, Haydn. 2015. “Truth and Reconciliation chair urges Canada to adopt UN declaration on Indigenous Peoples.” CBC News, June 1, 2015. Accessed March 31, 2023. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/truth-and-reconciliation-chair-urges-canada-to-adopt-un-declaration-on-indigenous-peoples-1.3096225

Yellowhead Institute. 2022. “Calls to Action Accountability: A 2022 Status Update on Reconciliation.” Accessed February 22, 2023. https://yellowheadinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/TRC-Report-12.15.2022-Yellowhead-Institute-min.pdf

Since you're here... Did you know that People for Education conducts our own research and provides regular updates on education issues? Sign up for our newsletter and be the first to get our news and reports.

- Student Circle

- Applications

- Careers/Contact

Official logo

Rocks are our Grandfathers, they have held our teachings since time immemorial.

Rocks represent the integrity of Indigenous languages, cultures and knowledge. Rocks are resilient, forged by the elements and shaped by the environment over generations.

For these reasons, the Indigenous Advanced Education and Skills Council has chosen the Rock as the primary element in its official logo. The colours – reds and browns – reflect the earth and minerals that develop the rock’s character, strength and diversity.

The Rock also represents the strength of the communities and partners forming the foundation and future of Indigenous post-secondary education and training. The quality assurance standards established by the Council, signified by the rock’s layers, support students at Indigenous Institutes in their communities. Asymmetrical and varied layers are also similar to the many different approaches to education and multiple relationships that bond to support the journey of life-long learning.

Inside The Council

The indigenous advanced education and skills council, is a quality assurance organization.

The Indigenous Advanced Education and Skills Council (IAESC) is an Indigenous-controlled and governed Council, recognized under the Indigenous Institutes Act, 2017 and tasked with establishing quality assurance standards and benchmarks for programs delivered by the Indigenous Institutes pillar.

The Council uses a quality assurance process steered by its Indigenous Institutes Quality Assessment Board (IIQAB). Through a Memorandum of Understanding signed in August 2018, the World Indigenous Nations Higher Education Consortium (WINHEC) is providing IAESC reference to its foundational accreditation process and access to its expertise.

The founding members of the Council include the late Delbert Horton, Pamela Toulouse, PhD, Bob Watts and Chair and Executive Director, Laurie Robinson. The current Board of Directors are Bob Watts, Annie Ashdown, Lora Tisi, and Laurie Robinson.

The Indigenous Institute Quality Assessment Board (IIQAB) founding members include Kali Storm, Laura Horton and Dan Roronhiakewen Longboat, PhD. IIQAB members currently include Laura Horton, T’hohahoken Michael Doxtater, PhD, and Kathy Absolon, PhD.

IAESC is a Not-for-profit corporation, pursuant to the Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act, 2009 .

Indigenous Institutes Act, 2017

The Indigenous Institutes Act, 2017 received royal assent on December 14, 2017.

This legislation recognizes Indigenous Institutes as a unique and complementary pillar of Ontario’s post-secondary education and training system; and an Indigenous controlled and governed Council.

On April 13, 2018, Ontario Regulation 239/18 recognized the Indigenous Advanced Education and Skills Council as the Council and nine Indigenous Institutes for the purposes of the Act.

As the Council recognized in regulation, IAESC may:

- Approve Indigenous Institutes to grant diplomas, certificates and degrees;

- Establish a quality assessment board and quality assurance standards;

- Make recommendations to the Ontario government regarding which Indigenous Institutes should be included to receive operating funding; and,

- Approve Indigenous Institutes to use the term “university.”

Consultative Process

The following elements make up our consultative process:

- The development of evidence-based research

- Including the development of outcome documents

- Engagement with experts in Indigenous education, knowledge and language

The Indigenous Advanced Education and Skills Council (IAESC) solicits direction including information and knowledge from Indigenous Institutes, and the Nations and communities they serve, through dialogue.

A dialogue is…

an open and ongoing conversation between representatives from IAESC and representatives from Indigenous Institutes (often includes students, teaching and learning staff, community members, and knowledge keepers).

Why is dialogue important?

Dialogue helps ensure that the development, implementation, and integrity of quality assurance for the Indigenous Institutes pillar is guided by a consultative process that works to build consensus before decisions affecting Indigenous Institutes are made. As a non-political, arm’s-length, Indigenous-governed and controlled organization, dialogue sessions help IAESC develop an Indigenous quality assurance process reflective of Indigenous intellect and worldview. The process helps protect the interests of learners and aligns with the principles of consensus building articulated in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, 2007 .

What is the process?

Indigenous Institutes are invited to a session with IAESC and they bring their representatives of their institutions and communities.