Home — Essay Samples — Religion — Judaism — Summary of Judaism: Origin, History, and Major Beliefs

Summary of Judaism: Origin, History, and Major Beliefs

- Categories: Judaism

About this sample

Words: 685 |

Published: Jan 31, 2024

Words: 685 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, origins of judaism, history of judaism, major beliefs and practices in judaism.

- "Judaism 101." JewFAQ.org, www.jewfaq.org/index.shtml. Accessed 22 Sept. 2021.

- "A Brief History of Judaism." Jewish Virtual Library, www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/a-brief-history-of-judaism. Accessed 22 Sept. 2021.

- "Judaism." BBC Religion & Ethics, 27 Jul. 2011, www.bbc.co.uk/religion/religions/judaism/. Accessed 22 Sept. 2021.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Religion

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1865 words

2 pages / 890 words

4 pages / 1630 words

2 pages / 684 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Judaism

Judaism and Zoroastrianism are two ancient religions that have influenced the development of several other religious and philosophical systems. Despite emerging from different regions and cultural contexts, these two religions [...]

The Old Testament serves as a cornerstone for both Judaism and Christianity, laying the foundation for their respective faiths. Although these two religions have distinct theological beliefs and practices, it is fascinating to [...]

Despite the difference in doctrines, the Jews, Christians, and Muslims have, in one way or another, related in accordance to their faith and beliefs. The three monotheistic religions are known for their high regard for their [...]

Christianity and Judaism are two of the world's oldest monotheistic religions, with shared origins in the ancient land of Canaan. Despite their common ancestry, these two faiths have developed distinct beliefs and practices over [...]

Though Judaism, Hinduism and Buddhism have similar philosophies but different religious practices, they all provide their own answers to the origin and end of suffering. These world religions are concerned with how to cope with [...]

Christianity, Islam, and Judaism are three of the most influential world religions in history. While Judaism isn’t as large as Christianity and Islam, its impact on the world has still been as profound. Judaism, Islam, and [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Travel/Study

BIBLE HISTORY DAILY

The origins of judaism.

When did the laws of the Torah become the norm?

Public ritual bath from the Herodian fortress at Masada, and the origins of Judaism. The massive emergence of similar pools across Judea, in accordance with the purity laws of the Torah, corresponds with the origins of Judaism in the mid-second century BCE. Photo by Talmoryair, CC BY 3.0 .

Where can we situate the origins of Judaism? If we were able to travel back in time, would we find ancient Israelites and Judeans following the laws of the Torah during the First Temple period? Almost certainly not, claims Yonatan Adler in his recent scholarly book and a popular article that was just published in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review . So, what about during the Babylonian Exile (sixth century BCE), which is when many biblical scholars date the completion of the Torah? In his article “ The Genesis of Judaism ,” Adler asserts that even at this later date, most ordinary Judeans were not yet following the laws of the Torah. What does this mean for the origins of Judaism?

Become a Member of Biblical Archaeology Society Now and Get More Than Half Off the Regular Price of the All-Access Pass!

Explore the world’s most intriguing biblical scholarship.

Dig into more than 9,000 articles in the Biblical Archaeology Society’s vast library plus much more with an All-Access pass.

The Genesis of Judaism

For millennia, Jewish identity has been closely associated with observance of the laws of the Torah . The biblical books of Deuteronomy and Leviticus give numerous prohibitions and commandments that regulate different aspects of Jewish life—from prayers and religious rituals to agriculture to dietary prescriptions and ritual bathing. It stands to reason that the moment when people in ancient Judea recognized these laws as authoritative would mark the origins of Judaism.

As Adler discusses, however, even the Bible itself presents a somewhat different picture:

Ancient Israelite society is never portrayed as keeping the laws of the Torah. The Israelites during the time of the First Temple are never said to refrain from eating pork or shrimp, from doing this or that on the Sabbath, or from wearing mixtures of linen and wool. … Nor is anybody ever said to wear fringes on their clothing, to don tefillin on their arm and head, or to have an inscribed mezuzah on the doorposts of their homes. Whatever it is that the biblical Israelites are doing, they do not seem to be practicing Judaism!

So, when can we date the actual origins of Judaism? Or, as Yonatan Adler puts it: “When did ancient Judeans, as a society, first begin to observe the laws of the Torah in their daily lives?” To answer this question, Adler looks at the archaeological evidence for widespread observance of the laws of the Torah. He suggests that our inquiry begin in the first century CE, where we have plenty of evidence. He then goes backward in time, until he reaches a point when we can no longer see material traces of typical Jewish religious and ritual practices.

The Judean community on Elephantine, in southern Egypt, produced a wealth of documents in Aramaic, including this adoption contract from October 22, 416 BCE. They provide clues also about observance (or not observance) of the laws of the Torah. Photo courtesy of Brooklyn Museum, Bequest of Theodora Wilbour, from the collection of her father, Charles Edwin Wilbour.

In particular, Adler traces archaeological imprints of the biblical laws addressing dietary prohibitions, ritual purity, graven images, tefillin and mezuzot , and Sabbath observance. In every instance, the trail of archaeological evidence ends in the mid-second century BCE—moving the origins of Judaism several centuries later than even the most critical scholars previously thought.

Surprisingly, textual sources from Babylon and Egypt, including this letter from the island of Elephantine, reveal that fifth-century BCE Judeans did not celebrate Passover at a set date, were not aware of a seven-day week or the Sabbath prohibitions, and that they sometimes prayed to deities other than Yahweh.

Widespread observance of the ritual purity laws , as attested through ritual baths (later known as mikva’ot ) and the use chalk vessels, is strong in the first century BCE but gradually disappears as we look further back in time past the late second century BCE.

When it comes to the biblical command against graven images (Deuteronomy 5:8), we can see that during the Persian period even the high priests were issuing coins with depictions of human and animal figures. The pictured silver coin from around 350 BCE bears, on its obverse, a crude depiction of a human head. The reverse features a standing owl with the feathers of the head forming a beaded circle. The Hebrew inscription reads “Hezekiah the governor,” referring to the governor of the Persian province of Yehud (Judea).

Persian-period Yehud coin, from c. 350 BCE. The presence of graven images contradicts the laws of the Torah. Photo by Classical Numismatic Group, CC BY-SA 3.0 , via Wikimedia Commons.

Only a century later, in the Hasmonean and Herodian periods, Judean leaders consciously refrained from using figurative imagery, which they replaced with decorative elements and more extensive texts—apparently adhering to the pentateuchal prohibition against graven images. Instead, the pictured bronze prutah of John Hyrcanus I from the late second century BCE features, on the reverse side, two cornucopias adorned with ribbons, and a pomegranate between them. Its obverse bears a lengthy Old Hebrew inscription inside a wreath that reads, “Yehohanan the High Priest and the Council of the Judeans.”

Hasmonean coin of John Hyrcanus I, from the late second century BCE. The absence of any human or animal figures seems to signal widespread acceptance of the laws of the Torah and to herald the origins of Judaism. Photo in public domain.

In sum, the archaeological evidence for observance of the laws of the Torah in the daily lives of ordinary Judeans seems to situate the origins of Judaism around the middle of the second century BCE.

To delve into the intricacies of the textual and archaeological evidence for widespread observance of the laws of the Torah and the origins of Judaism, read Yonatan Adler’s article “ The Genesis of Judaism ,” published in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review .

—————— Subscribers: Read the full article “ The Genesis of Judaism ” by Yonatan Adler in the Winter 2022 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review .

Read more in Bible History Daily:

Original Maimonides Manuscript Goes Digital

All-Access Subscribers, read more in the BAS Library:

Biblical Law

Related Posts

The Masoretic Text and the Dead Sea Scrolls

By: BAS Staff

On What Day Did Jesus Rise?

By: Biblical Archaeology Society Staff

The Last Days of Jesus: A Final “Messianic” Meal

By: James Tabor

The Exodus: Fact or Fiction?

10 responses.

David Holland said >>Wondering if the rise of the Pharisaic movement was related to the forces driving the revolt<<

I wasn't alive in those days (contrary to what my kids say), and can only say they were the people's choice and party of the common people at least as early as Alexander Yannai ("Jannæus"). But I do know one thing:

The Pharisees were not happy that after the battles were history, the Khasmonayeem ("Hasmoneans") had both the kingship and the priesthood. Previously there was a balance of power: Kings were of the Davidic line, and priests were descendants of Aharon" {Aaron").

Now the priests, labeled "Sadducees" (derived from the ancient high priest Tzadok) controlled both powerful positions. Clashes were inevitable.

The monotheism of Judaism developed the same way as that of Islam by evolving from a polytheistic belief in many gods. Originally both Yahweh & Allah were only one of many different gods in Canaan & Arabia but eventually Yahweh was selected as the sole god to be worshiped just as Mohammed selected Allah to be the sole god when he formed Islam (using tenets and history from Judaism as a guide). This evolutionary path is glimpsed in the Bible when it had been reduced to one male god and one female goddess, Yahweh and Asherah, before Asherah was eliminated by, IIRC, King Josiah.

Baseless unadulterated nonsense! Allah (Satan) was invented around 600 AD and based on an apparent demonic encounter by Muhammad. The worship of Yahweh (God) dates back to the beginning of creation (albeit under some different name probably), certainly long before the entry of the Israelites into Canaan. As a consequence of Joshua’s conquest not eradicating all the Canaanites along with their idolatry, Asherah along with other Satanic idols were eventually incorporated into the Israelites’ worship, which was naturally followed by God’s judgment, resulting in said idols being eliminated, rightfully leaving only Yahweh left to be worshipped. The Bible blatantly contradicts your evidently false narrative!

Can’t help but think about the Maccabean Revolt when presented that suggested dating. Wondering if the rise of the Pharisaic movement was related to the forces driving the revolt, or perhaps a separate but related response to Hellenistic pressures.

As a believer (of which BAR has no understanding), I will state the obvious as found in the Bible. God does not change, therefore the laws of God were extant even before man was created. Avraham knew and understood the entirety of the statutes, commandments, and law (Gen. 26:5 …and Avraham kept my keeping, my commandments my stautes and my laws.) From that time on the law was observed. Since the commandments, statutes, and law were considered holy, you would not find extra biblical sources relating to it.

Jump to the time of Yeshua and it is clear the rabbinics had removed God from the law. The law was now on equal footing as the rabbinics and was being manipulated by the rabbinics, hence Yeshua’s issue with the Pharisees and the Sadducees. This why you will find extra biblical documents regarding the law just pior to and from this time forth. I think that maybe BAR scholars (as they call themselves) need to wake up a bit.

And that’s why he fornicated with Hagar.

He and Sarai were apparently following a known Babylonian law that called on the sterile wife to provide her husband with a servant to produce a child. The consequences of the situation make it clear it was a terrible idea. But one of the fascinating things about the Bible is that the heroes of the People of God actually make all kinds of mistakes and commit all kinds of infidelities, while God keeps trying to teach them and set them right, and is always faithful.

Interesting article but the Bible is clear that many did not follow the practices laid down by God to the people of Israel. Even kings are recorded as violating Gods laws. While finding graven images is evidence of those who did not follow Judaism, it is not proof that others were not following Judaism or not making graven images for religious reasons. And a lack of written material during this time stating their beliefs is understandably absent since any kind of writing except on clay or stone carvings is almost non-existent. Therefore, finding evidence that these laws were violated is not necessarily evidence that the laws did not exist during that time.

It’s funny that even scholars conveniently ignore the next words of the 10 Commandments. The prohibition against graven images is immediately followed by its rationale: “You shall not bow down to them nor serve them.” Ergo, it does not follow that Jews were prohibited to make coins that had a face carved into them, just as long as they didn’t worship them.

Well said. The Mt Ebal Curse Tablet appears to reinforce the Biblical events referred to in Deuteronomy and Joshua regarding the Israelites worshipping at Ebal, uttering the curses in the Law of Moses. It seems to date from the 1400s BCE (nice knowing ya, Ramesside Exodus theory), mentions Yahweh by name 4 times, written in Proto-Sinaitic script. Michael Shelomo Bar-Ron’s recent translations of the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions also support the historicity of Exodus-related events.

Write a Reply or Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Recent Blog Posts

The Ancient Altar from Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre

Biblical “Chamber” Identified in Jerusalem?

Akhenaten and Moses

Must-read free ebooks.

50 Real People In the Bible Chart

The Dead Sea Scrolls: Past, Present, and Future

Biblical Peoples—The World of Ancient Israel

Who Was Jesus? Exploring the History of Jesus’ Life

Want more bible history.

Sign up to receive our email newsletter and never miss an update.

By submitting above, you agree to our privacy policy .

All-Access Pass

Dig into the world of Bible history with a BAS All-Access membership. Biblical Archaeology Review in print. AND online access to the treasure trove of articles, books, and videos of the BAS Library. AND free Scholar Series lectures online. AND member discounts for BAS travel and live online events.

Signup for Bible History Daily to get updates!

Judaism Essay: Summary of Judaism, Its Origin and History

Introduction, summary of judaism history, works cited.

Judaism is the religious practices and beliefs and the way of life of the Jews. It began as a religious conviction of the diminutive nation of the Hebrews. The followers of the religion have through the thousands of years since its inception been persecuted, dispersed and faced intense suffering physically and psychologically (Lynch1).

Occasionally, the religion has experienced victory. It continues to have intense influence on culture and religion. In the world today, the religion has a following of more than 14 million people (Judaism1). They identify themselves as Jewish. Contemporary Judaism is a complex occurrence that involves both religion and a nation.

The history is written in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament). The first five books of the Bible describe the emergence of Jews. There is the description of the choice of God on Jews to be the living example for other humans to emulate.

The Hebrew Bible explains how the relationship between Jews and God worked. God chose Abraham be the father figure of a populace that would be unique to God. They would be a mark and symbol of holiness and good behavior to the entire world (BBC1). History asserts that the Jewish people were guided by God through many challenges and troubles.

During the time of Moses, God gave the Jewish people life guidelines that they should live with. These included the Ten Commandments. This was the period which the Judaism emerged as a structure religion. Under the guidance of God, the Jews turned into powerful communities with renowned kings such as Solomon, David and Saul (BBC 1).

The construction of the first great temple by Solomon made the Jews to focus the worship of God in the temple. The temple housed the Ark of the Covenant. It was the only place where rituals would be carried out. In 920 BCE, the Jewish kingdom disintegrated and the people tore into small groups. Many Jews were exiled into Babylon.

This was the beginning of the Jewish culture in the Diaspora. Majority of the Jews in exile opted not to return to Israel. The next 300 years that followed were marked by gradual and steady growth in Jewish strength and number. Their land was in the mean time being governed by foreign authorities. The teachers and scribes who emerged during this period helped the population to interpret and explain the Bible.

The Jews from then were able to freely practice their faith. In 175 BCE, there was a Jewish revolt against the Syrian King who implemented a number of rules that sought to completely wipe out Judaism. He dishonored the temple and wanted the population to worship Zeus. The temple was eventually restored after the revolt which is celebrated by Jews in the Hanukah festival.

The Romans took advantage of the weakening of the Jewish kingdom due to internal splitting up and established their rule. This was followed by years of oppression and taxation by Roman rules who despised Judaism. The Sadducees became allies of the Roman rulers subsequently loosing the support and faith of the Jews. The people opted to have Pharisees as their teachers (BBC1).

The Catholic encyclopedia suggests that Judaism was the original of a variety of religions including Islam and Christianity (Judaism 1). The Jewish people established settlements in Arabia before the birth of Mohammed. They commanded considerable influence on the Arabian citizenry. At one point in South Arabia, the Jews had an Arab-Jewish empire which was eventually terminated by a king of Abyssinia in 530.

The Jews lost the royal estate but remained considerably powerful in the northern Yemen. In Mecca, there was a small Jewish population. Mohammed interacted with the Jews and became acquitted with the religion. When he fled to Medina, the acquaintance became and more established as the location was populated by Arabian Jews.

Abraham was the first Jew according to religious Jews. He was the first to preach monotheism and despised idolatry. As a reward, he was promised to have many children by God. This promise fulfillment came in the form of Isaac. Isaac carried on Abraham’s work and inherited Canaan. Isaac’s son, Jacob, was sent to Egypt by God together with his children. They were eventually enslaved by Egyptians. Moses was subsequently sent to Egypt to redeem the Jews from slavery.

This period was tempting to Moses who eventually gave the Torah to the Jews. He managed to take the people to Israel after many years in the jungle. Torah is the Hebrew translation of instruction or teaching particularly law. It refers to the first five books of the Old Testament. On a larger scale, Torah is used by Jews to refer the broad range of commanding Jewish religious wisdom in history (Space and motion 1).

In view of the first five books of the Bible, many ideas and concepts are expressed in form of stories as opposed to being listed as laws. The book of Deuteronomy is reiteration of the previously mentioned laws in the first four books. Most of the laws that govern Judaism are got from textual clues because they are not mentioned straightforwardly in the Torah. The Torah is the fundamental document of the Jewish religion. In a principled framework, it is the basis of all the biblical commandments.

The period covering 1000 CE saw Jews establish themselves in Spain. They co-existed happily with the Islamic rulers. They developed a thriving study of Hebrew literature, science and the Talmud. There was severally the attempt to convert all the Judaism followers to Islam.

When all this failed, the millennium that followed saw the increased operations of military by Christian states to recapture the holy land. In German, the Christian armies attacked Jewish communities. They succeeded in capturing Jerusalem where thousands were slaughtered and many other enslaved. The victims included Muslims and Jews. Jews were banned from entering the city just like Romans had previously done. In the meantime, the Jewish population was increasing in Britain. They enjoyed the protection by Henry I.

The Babylonian exile presented new ideas to Jews. It is during this period that the notions of particular angels arose. Evil was personified as Satan. The idea of resurrection from the dead emerged (Neusner2). Alexander the Great played a significant role in entrenching the idea of immortality of the soul.

The level of Hellenization brought about conflict within the Jewish community. The Maccabees revolted against the Syrian Seleucid rulers. There was extensive martyrdom that increased the momentum to the notion of collective resurrection of the deceased. The soul was perceived to be immortal. They formulated the belief that while the physical body awaited resurrection, the soul existed in another realm (Seltzer6).

Life conditions deteriorated and apocalyptic beliefs increased. Messianic kingdom and national catastrophe were considered imminent. As time passed, Rabbanic Jews completed the process of replacing the Temple with the Synagogue. The Rabbanical Judaism arose from the Pharasiac movement as a response to the destruction of the Second Temple (Smith 1).

This was in a move to codify and redact oral law. The Rabbis wanted to interpret the practices and concepts of Judaism in the absence of the Temple and the people being in exile. It dominated the Jewish religion close to 18 centuries. In the process, it developed the Midrash, the Talmud and the great icons of the medieval philosophies.

In 1492, Jews were expelled from Spain which led to Sephardic influence of South France, North Italy and the Levant. There was the Berber invasion and anti-Jewish incidents became common in Europe (BBC1). Jews had been forced to take up Christianity. However, they continued to secretly practice their religion. Eventually, majority emigrated and returned to the Jewish fold. The 18 th century remained largely turbulent with hardening of the Jews as a reaction to philosophical liberalism and Sabbatianism.

The first five books of the Bible describe the emergence of Jews. Under the guidance of God, the Jews turned into powerful communities with renowned kings such as Solomon, David and Saul. The emergence of Judaism in the Diaspora was as result of being exiled. Alexander the Great played a significant role in entrenching the idea of immortality of the soul.

There was extensive martyrdom that increased the momentum to the notion of collective resurrection of the deceased.Contemporary Judaism was split by the law (halakal) in the 19 th century. Orthodox Jews maintain the traditional practice while Reform Jews only uphold rituals that they believe will God-oriented, Jewish life.

The attempt to define the essence of Judaism is a process that has existed for ages. At anyone point, there is intense emphasis on one aspect of the three major concepts of the Jewish religion (God, Israel, Torah).

BBC. “ Judaism at a glance ”. Web.

Lynch, Damon. “ Judaism. There we sat down ”. 1972. Web.

Smith, Huston. “ Judaism: Religion facts ”. Web.

Seltzer, Robert. Jewish people, Jewish thought: the Jewish experience in history. London, UK: Macmillan, 1980.

Spaceandmotion. “ Theology: Judaism.History and Main Beliefs of Jewish Religion / the Jews ”. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, October 28). Judaism Essay: Summary of Judaism, Its Origin and History. https://ivypanda.com/essays/brief-summary-about-judaism/

"Judaism Essay: Summary of Judaism, Its Origin and History." IvyPanda , 28 Oct. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/brief-summary-about-judaism/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Judaism Essay: Summary of Judaism, Its Origin and History'. 28 October.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Judaism Essay: Summary of Judaism, Its Origin and History." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/brief-summary-about-judaism/.

1. IvyPanda . "Judaism Essay: Summary of Judaism, Its Origin and History." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/brief-summary-about-judaism/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Judaism Essay: Summary of Judaism, Its Origin and History." October 28, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/brief-summary-about-judaism/.

- Judaism' Religion: History and Concept

- Judaism: What Makes Someone Jewish?

- Judaism: Historical Context and Ffundamental Principles

- Judaism in Canaan History

- Torah and Qur'an: The Laws and Ethical Norms

- History of Judaism Religion

- Judaism: Religious Beliefs Evolution

- Hebrew Monotheism: Origins and Evolution

- Judaism as the Oldest Monotheistic Religion

- Second Temple Judaism: Scriptures and Stories

- Brief Summary of the History of Christianity

- The Five Pillars of Islam

- List and explain the eight seasonal celebrations of Wicca

- Zen Buddhism and Oneida Community

- Judaism, Islam and Christianity: Differences and Similarities

Search the Holocaust Encyclopedia

- Animated Map

- Discussion Question

- Media Essay

- Oral History

- Timeline Event

- Clear Selections

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Português do Brasil

Featured Content

Find topics of interest and explore encyclopedia content related to those topics

Find articles, photos, maps, films, and more listed alphabetically

For Teachers

Recommended resources and topics if you have limited time to teach about the Holocaust

Explore the ID Cards to learn more about personal experiences during the Holocaust

Timeline of Events

Explore a timeline of events that occurred before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Introduction to the Holocaust

- Liberation of Nazi Camps

- Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

- Boycott of Jewish Businesses

- Axis Invasion of Yugoslavia

- Antisemitism

- How Many People did the Nazis Murder?

- The Rwanda Genocide

Introduction to Judaism

Judaism is a monotheistic religion, believing in one god. It is not a racial group. Individuals may also associate or identify with Judaism primarily through ethnic or cultural characteristics. Jewish communities may differ in belief, practice, politics, geography, language, and autonomy. Learn more about the practices and beliefs of Judaism.

Jews have lived in many different countries around the world through the centuries.

Major events in the history of Judaism include the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, the Holocaust, and the founding of the State of Israel in 1948.

Judaism in the 21st century is very diverse, ranging from very Orthodox to more modern denominations.

- Jewish communities before the war

Jewish Life and Religious Practices

There is a wide variety of acceptance and observance of the following practices by denominations and individual Jews.

Jewish life is guided by its annual and life cycle calendars. The annual calendar is a lunar calendar with approximately 354 days in one year on a 12-month cycle, with an extra month (Adar II) added occasionally to compensate for the difference between the lunar and solar calendars.

The Torah is read ritually in synagogue three times a week, on Mondays, Thursdays and Saturdays, following a yearly cycle through the entirety (or a third, depending on community) of the Five Books of Moses. Additionally, on holidays, special sections are read in synagogue that tie to the themes or origin story of the holiday being observed.

Jewish prayer services are conducted in the Hebrew language in the more traditional denominations of Judaism, and include varied levels of English (or the native language of the community’s Jews) in denominations such as Reform, Reconstructionist and Renewal. A rabbi can lead services but is not required. On weekdays, daily prayers are recited three times—morning, afternoon, and evening—with a fourth prayer service added on the Sabbath and holidays. While many prayers can be recited individually, certain prayers and activities, such as the reading of the Torah, the mourner’s prayer (the kaddish ), require a minyan or quorum of ten Jewish adults. As with the distinctions regarding English in the prayer service, some traditional denominations only count male adults in a minyan , while others count all adults.

Other central aspects of Jewish ritual observance include the dietary laws (laws of kashrut ) which forbid consumption of certain foods (like pork or shellfish), prohibit the mixing of milk and meat, and prescribe special rules for the slaughter of meat and poultry. Denominations and individual Jews may or may not follow these dietary laws strictly.

Major life-cycle events in Jewish tradition include the brit milah (ritual circumcision on the eighth day of a Jewish boy’s life), Bnai Mitzvah (a ceremony marking the passage from childhood to adulthood, at 12 years for a girl and 13 for a boy), marriage, and death.

Following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE, the synagogue (derived from a Greek word meaning “assembly”), or Jewish prayer and study house, became the focal point of Jewish life. The role of the priesthood, so central to the Temple service, diminished, and the rabbi (literally, “my master”), or scholar versed in Jewish law, rose to a position of prominence in the community.

After the Holocaust

Before the Nazi takeover of power in 1933, Europe had a vibrant and mature Jewish culture.

By 1945, after the Holocaust , most European Jews—two out of every three—had been killed. Most of the surviving remnant of European Jewry decided to leave Europe. Hundreds of thousands established new lives in Israel , the United States , Canada, Australia, Great Britain, South America, and South Africa.

As of 2016, there were approximately 15 million Jews around the world. About 85% of world Jewry lives in Israel or the United States.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Investigate the wide range of observances and traditions in the Jewish communities before, during, and after the Holocaust.

- Learn about the history of the Jewish community in your country.

Thank you for supporting our work

We would like to thank Crown Family Philanthropies and the Abe and Ida Cooper Foundation for supporting the ongoing work to create content and resources for the Holocaust Encyclopedia. View the list of all donors .

Trending Topics:

- Say Kaddish Daily

- Passover 2024

Judaism & Science in History

Jewish tradition and scientific reasoning provide two different and sometimes contradictory sources of truth, and Jewish thinkers throughout the ages have struggled to address these contradictions.

By My Jewish Learning

Some argue that the two are incompatible; we must reject either the Jewish tradition or science. Others strive to integrate the two by reading scientific theory into the Jewish tradition or understanding science in light of the Jewish tradition. Still others argue that the Jewish tradition and science cannot contradict each other because they serve two different purposes. While science explains how the world works, the Jewish tradition explores why the world works. Science describes the world, and the Jewish tradition prescribes how we should act in it.

The Bible and the Talmud did not see science as an opposing system of truth; rather, science and the Jewish tradition were understood to be two different manifestations of the same divine truth. The Bible embraced knowledge of the natural world as a means of knowing God. The Psalmist described the amazing natural phenomena that God created, and concluded, “How great are Your works, God. You made them all with wisdom” (Psalm 104).

The Rabbis of the Talmud saw science not only as a means of knowing God, but also as a necessary tool in halakhic (legal) decision making. The Talmud, for example, used detailed astronomical calculations in determining the Jewish calendar, but also asserted that these calculations provided insight into the divine mind. “He who knows how to calculate the cycles and planetary courses but does not, of him the Scripture says: ‘But they regard not the work of the Lord, neither have they considered His actions'” (Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 75a).

The Talmud contains many references to scientific theories of its day, including many theories which have since been disproved. The Rabbis, for example, argued that one cannot break the Sabbath to help a woman in her eighth month give birth, because such a baby cannot be viable. Similarly, the Rabbis ruled that one can kill lice on the Sabbath because lice do not reproduce sexually.

Medieval Jewish thinkers, many of whom were themselves great scientists, struggled with the apparent contradictions between Judaism and science.

Maimonides saw both science and the Jewish tradition as expressions of divine wisdom and strove to integrate the two. He argued that if science disproved creation ex nihilo without a doubt, he would reinterpret biblical passages to conform to science (though he was not convinced by the Aristotelian proofs for the eternity of the world).

Medieval Jewish thinkers struggled to reconcile not only the Bible, but also the Talmud, with contemporary science. They understood that some Talmudic laws were based on incorrect science, and they disagreed about whether one should change these laws to accord with the science of their day, or maintain the laws out of respect for Talmudic authority.

The rise of modern science created new challenges for the Jewish tradition. Unlike some segments of Christianity, Jewish thinkers have rarely perceived the scientific method to be problematic in and of itself, but the results of this method often pose a problem. Evolution contradicts the biblical account of creation; psychology challenges the Jewish belief in free will; and historical scholarship and biblical criticism call into question the traditional understanding of the Bible.

For liberal denominations that have a more open approach to divine revelation and the development of Jewish law, these issues pose fewer problems. Orthodox Jews, however, who have a more conservative approach to the authority of the Bible and Talmud, have struggled to respond to scientific claims without undermining that authority. Traditional Jewish thinkers today face similar options to those faced throughout Jewish history: rejecting science, reconciling science and Jewish tradition, or arguing that the two have different purposes. Today, the dialogue between Judaism and science continues as both science and Judaism develop in new directions.

Pronounced: TALL-mud, Origin: Hebrew, the set of teachings and commentaries on the Torah that form the basis for Jewish law. Comprised of the Mishnah and the Gemara, it contains the opinions of thousands of rabbis from different periods in Jewish history.

Join Our Newsletter

Empower your Jewish discovery, daily

Discover More

Jewish Culture

Eight Famous Jewish Nobel Laureates

From Albert Einstein to Bob Dylan, there are many Jewish Nobel laureates who have become household names.

Modern Israel

Modern Israel at a Glance

An overview of the Jewish state and its many accomplishments and challenges.

American Jews

Black-Jewish Relations in America

Relations between African Americans and Jews have evolved through periods of indifference, partnership and estrangement.

Select Page

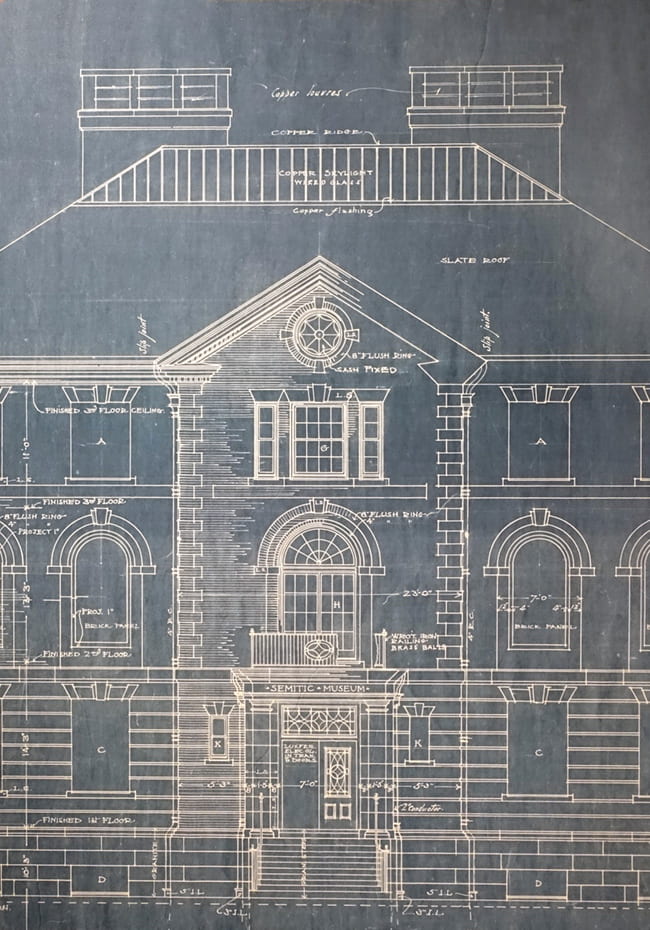

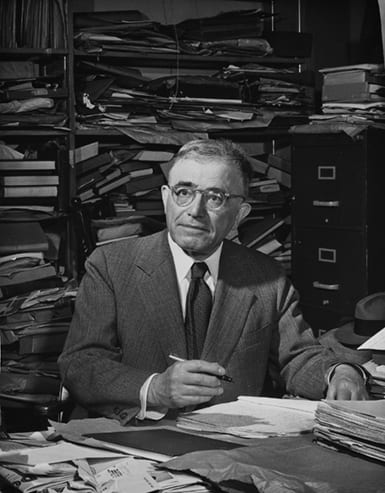

George Foot Moore (1851–1931) by Ignaz Marcel Gaugengigl. Harvard University Portrait Collection, gift of friends and colleagues of Dr. Moore to the Divinity School, 1926, h348, photo by Imaging Department © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Leaving aside more recent figures, the most impressive scholar of Hebraica in the history of Harvard is surely George Foot Moore (1851–1931), who served as Professor of the History of Religion from 1902 to 1928. And a remarkably capacious concept of religion he had: the first book of his two-volume History of Religions (1920) treated China, Japan, Egypt, Babylonia, Assyria, India, Persia, Greece, and Rome, and the second focused on Judaism, Christianity, and Mohammedanism ( sic ). Even granting the obvious fact that far less was known about most of those traditions then than now and that the methodological and theoretical frameworks were more limited, one cannot come away from Moore’s study unimpressed with the command of historical and textual detail it exhibits and the author’s eagerness to be fair to the religions on which he wrote. In a memoir of Moore published soon after his death, his colleague (and sometime dean) William Wallace Fenn observed that “it was often said that he could have taught any course in the curriculum of the Theology School, except those listed under Practical Theology and Social Ethics, quite as satisfactorily as the professor who actually offered it.” 14 Personally, I am confident in the judgment that Fenn intended his comment to reflect on Moore rather than on his colleagues.

Moore came to his phenomenal Hebraic competence naturally. Fenn reports of his grandfather, the Reverend George Foot, that “largely by independent study, he mastered Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and French” and that, having taught his daughter (Moore’s mother) Hebrew, the two of them had read the Hebrew Bible through in the original seven times before she was married. 15 Moore’s own formal education was strikingly short. Largely self-taught like his grandfather, he went into the pastorate after graduating Yale in two years and Union Theological Seminary in New York in one.

Into the pastorate but not out of scholarship. Serving a church in Zanesville, Ohio (1878–1883), he took up the study of rabbinic Hebrew with a local rabbi. His comments about the experience tell us much about both Moore himself and the type of study the two undertook:

It was an old-fashioned training. Its methods were doubtless of a kind which our pedagogical experts would regard as altogether obsolete; but it accomplished its end, which is, after all, the final test of the efficiency of a method. In one respect it differed widely from that of our schools; unsophisticated by educational psychology, the yeshiva-trained teacher, like his predecessors in the great age of classical learning in Western Europe, naively assumed that the object of studying a subject was to know it, not to acquire a certificate of having been through it. In that antiquated education the memory was systematically trained, not methodologically ruined. 16

Moore pursued Modern Hebrew at the same time, 17 something that to this day cannot be said of most scholars of the Hebrew Bible.

George Foot Moore became a leading figure in the scholarship of the Hebrew Bible, playing a major role in the importation of innovative German scholarship into the United States; his commentary on Judges (1895) is still considered a classic. 18

But it is primarily in the realm of rabbinic Judaism that he left his mark. His three-volume study, Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of the Tannaim (1927–1930), is an extraordinary accomplishment, though dated in important ways now. For our purposes, I would like instead to concentrate on “Christian Writers on Judaism,” a long essay that he published in Harvard Theological Review (of which he was a founding editor) in 1921. 19 For reasons we shall see, it remains highly instructive.

The opening sentence tells it all: “Christian interest in Jewish literature has always been apologetic or polemic rather than historical.” 20 Whereas in “early Christian apologetic . . . the controversial points were the interpretation and application of passages in the Old Testament” to Jesus, “the discussion in the Middle Ages . . . assumed a more learned character in the endeavor to demonstrate that Christian doctrines were supported by the authentic Jewish tradition . . . or by the mostly highly reputed Jewish interpreters.” 21 (About this, Moore, perhaps with an eye to scholarship in his own day, dryly remarks, “Whatever its value otherwise, it had at least one good result—it led to a much more zealous and assiduous study of Judaism than any purely scientific interest would have inspired.” 22 ) Later, in the age of the Reformation, Protestants endeavored to show “that on the issues in debate between Protestants and Catholics the Jews were on the Protestant side.” In the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, however, “a broader interest in learning for its own sake as well as its uses prevailed . . . and led . . . to the creation of a great body of learned literature in every branch of Hebrew antiquities.” 23

In the case of the revival of Christian study of Judaism in the nineteenth century, Moore writes, “the actuating motive was to find in it the milieu of early Christianity” and, more ominously, “to exhibit the system of Palestinian Jewish theology in the first three or four centuries of our era as the antithesis of Christian theology and religion as they were taught in certain contemporary German schools.” 24 There thus emerged the notion that the Talmudic rabbis subscribed to an “abstract monotheism” by which they “exalted [God] out of this world, which, like an absentee proprietor, he administered henceforth by agents.” And thus there emerged as well the charge of “legalism,” which according to Moore, (writing, remember, in 1921) “for the last fifty years has become the very definition and the all-sufficient condemnation of Judaism.” Whereas before this, “Concretely Jewish observances are censured or ridiculed . . . ‘legalism’ as a system of religion, not to say as the essence of Judaism, no one seems to have discovered.” 25

Whatever it was that first impelled the young Moore to study with that rabbi in Zanesville, by the time he had become a mature scholar his research compelled him to recognize that the reflexive anti-Judaism of the Christian community was in urgent need of correction.

Moore’s own motivation was different. As one scholar puts it, “Moore did not attempt to establish connections between Judaism and Christianity, but”—and this was really quite revolutionary for a Christian scholar—“to present a composite and constructive view of Judaism in its own terms.” 26 Whatever it was that first impelled the young Moore to study with that rabbi in Zanesville, by the time he had become a mature scholar his research compelled him to recognize that the reflexive anti-Judaism of the Christian community was in urgent need of correction. As Fenn observes in his memoir, “Professor Moore . . . had come to believe that that popular conception of the Pharisees, although possibly true of some members of the sect, misrepresented them as a whole. He sometimes said to his friends: ‘If you and I had been living in Palestine in the first century of our era, we should have been Pharisees, I hope.’ ” 27

Although Judaism in the First Centuries of the Christian Era: The Age of the Tannaim remains an important compendium of rabbinic discussions, its assumptions are now, as mentioned, woefully out of date. For one thing, Moore failed to involve himself in sufficient depth in halakhah, or normative Jewish practice, the major focus of the Talmud and of much midrashic literature as well. 28 For another, he attributed a historically problematic normativity to rabbinic Judaism and failed to reckon with the vitality of its antecedents and competitors (although, in fairness, before the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, this was a more understandable move). He also accepted attributions of statements to various figures uncritically, thus limiting the utility of his massive study to historians. 29 Jacob Neusner was thus right when he wrote of Moore’s great study in 1980,“What is constructed is a static exercise in dogmatic theology.” 30 But Neusner erred when he observed in the same piece, “Moore closed many doors; he opened none.” 31 In fact, he opened the door to a fresh view of ancient Judaism for scores of Christian scholars—a “view of Judaism in its own terms.”

Not that every Christian scholar was willing to walk through it, as we shall see.

Harry Austryn Wolfson (1887–1974). Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University

The attentive reader will have noticed one element that has so far been missing in these reflections on Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School: Jews. Around 1912 this was to change, when Lyon and Moore spotted a brilliant young undergraduate who had immigrated with his family from Lithuania (then under czarist Russia), eventually creating a position for him and helping, along with Harvard Law professor (and later Supreme Court justice) Felix Frankfurter, to raise the money to fund it. 32 That young man, Harry Wolfson, was to serve on the Harvard faculty from 1915 to 1958. Although he remained grateful to the Divinity School—he had once lived in Divinity Hall—to the end of his career, and spoke warmly of the institution and of Moore in particular, 33 with his appointment the center of Jewish Studies at Harvard shifted to the Semitic Department, forerunner of today’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations (NELC).

The shift was, in a sense, inevitable. As Isadore Twersky, Wolfson’s disciple and successor as Nathan Littauer Professor of Hebrew Literature and Philosophy and the founding director of the Center for Jewish Studies, wrote in an appreciation of his teacher in 1976:

In the past—and that means up to very recent times—the study of Judaica was ancillary, secondary, fragmentary, or derivative. Jewish studies were sometimes referred to as service departments whose task was to help illumine an obscurity in Tacitus or Posidonius, a midrash in Jerome, a Hebrew allusion in Dante. . . . The establishment of the Littauer chair at Harvard for Harry Wolfson gave Judaica its own station on the frontiers of knowledge and pursuit of truth, and began to redress the lopsidedness or imbalance of quasi-Jewish studies. 34

My sense, however, is that the importance of Jewish Studies’ having “its own station” was not well grasped in the Divinity School even as late as the time I arrived here (1988), and for quite an innocent reason: the major focus of faculty and students alike was on Christianity, and that meant that the farther the Jewish material was from intersecting with the church (especially with its two-testament Bible), the less relevance it seemed to have. Sometimes, it even appeared that the very existence of Jews and Judaism beyond antiquity was not altogether appreciated. I still remember that the catalogue cross-listed a NELC course called “Sources of Jewish History: 500–1750” in Area I, “Scripture and Interpretation”—this despite the fact that its earliest material dated to 650 years or so after the latest source in the Hebrew Bible!

Already in his essay of 1921, Moore had lamented the prominence of specialists in the New Testament among those with a penchant for commenting negatively about Judaism without, in the main, finding “it necessary to know anything about the rabbinical sources.” In a mode somewhat reminiscent of Twersky’s two generations later, he found intensely problematic the work of those whose “interest in Judaism also was not for its own sake, but for the light it might throw on the beginnings of Christianity.” 35 It is hard to gainsay this judgment, or to pronounce it obsolete. But there is another side to the issue. Absent the focus on Christianity in general and the New Testament in particular, it is hard to see how most of those laboring under anti-Jewish stereotypes originating in Christianity (whether the individuals profess Christianity or not) will ever have occasion to confront their bias and to approach Jewish sources on their own terms. In that sense, paradoxically, a more religiously diverse and pluralistic academy can prove not less but more subject to the old misconceptions, since the latter have a life and a momentum of their own, quite independent of the ancient theological claims in which they took shape.

Fully 56 years after Moore published “Christian Writers on Judaism,” a New Testament scholar, only this time another American eager to correct the record, opened his own study by terming Moore’s essay “an article which should be required reading for any Christian scholar who writes about Judaism.” 36 As E. P. Sanders went on to show in his now classic study, Paul and Palestinian Judaism: A Comparison of Patterns of Religion , in the intervening decades many eminent New Testament scholars had failed to understand the import of Moore’s work and continued to trade in the old prejudicial stereotypes, sometimes even citing Moore against what he was, in fact, saying. 37 Decades after Moore, even after the Holocaust, the old biases were alive and well.

To me, the pressing question is why. Why has the negative presentation of Judaism proven so powerful, so protean, and so tenacious?

One reason, I think, is that it intersects with social prejudice—theological anti-Judaism drawing energy from, and imparting energy to, social anti-Semitism. But another reason is that the old pattern presents a simple but enormously powerful psychological drama—the innocent and peace-loving Jesus murdered by his godless, hypocritical, and legalistic kinsmen. As for the perfidious malefactors themselves, they are rightfully scattered all over the world with no state of their own, surviving as involuntary witnesses to the truth of the gospel, as they “groan in grief over their lost kingdom and quake in fear under the sway of innumerable Christian peoples,” as Augustine had put it. 38

The drama is so powerful, in fact, that, as Jonathan Sacks, now retired as Chief Rabbi of the United Kingdom and the British Commonwealth, put it, “it is a virus—and like a virus it mutates.” In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, “religious anti-Judaism,” the variety that we have been considering, “mutated into racial anti-Semitism,” best known for its role in Nazism and the Holocaust. But now what Sacks calls “the second great mutation of anti-Semitism in modern times” is underway, a mutation “from racial anti-Semitism to religious anti-Zionism.” The new strain, he writes, “uses all the mediaeval myths—the Blood Libel, poisoning of wells, killers of the Lord’s anointed, incarnation of evil—transposed into a new key and context,” with the state of Israel as the great malefactor. 39 With the Jewish people no longer stateless, groaning in grief over their lost kingdom and quaking in fear under the sway of innumerable Christian peoples, the old evil is again loose in the world.

It is essential to understand that Sacks is not speaking of those who are critical of this or that Israeli policy, even sharply so. If he were, he would be accusing large segments of the Israeli populace and world Jewry alike. Helpful criteria for distinguishing criticism of Israel from anti-Semitism are given by Alan Dershowitz, now retired as Felix Frankfurter Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. “So long as criticism is comparative, contextual, and fair,” Dershowitz writes, “it should be encouraged, not disparaged. But when the Jewish nation is the only one criticized for faults that are far worse among other nations, such criticism crosses the line from fair to foul, from acceptable to anti-Semitic.” 40 Unfortunately, the long history of Christian anti-Semitism provides a rich and remarkably resilient resource for that singling out of the Jewish state for consistently and univocally negative judgments unreflective of the complexity of the historical facts. 41

This latest mutation of anti-Semitism has indeed produced a virulent strain; only time will tell how hearty it is. Remarkably, another central figure in the history of Jewish Studies at Harvard Divinity School spotted the danger early on. Krister Stendahl, (1921–2008), an influential New Testament scholar who became dean of Harvard Divinity School (1968–1979) and, later, a Lutheran bishop, wrote in these pages in the wake of the Six-Day War (1967):

In the months and years to come, difficult political problems in the Middle East call for solutions. Christians both in the West and in the East will weigh the proposals differently. But all of us should watch out for the ways in which the ancient venom of Christian anti-semitism might enter in. A militarily victorious and politically strong Israel cannot count on half as much good will as a threatened Jewish people in danger of its second holocaust. The situation bears watching. . . . The present political situation may well unleash a type of Christian attitude which identifies Judaism and Israel with materialism and lack of compassion, devoid of the Christian spirit of love. 42

But if the goal is to think comparatively and contextually and with fairness to the full range of facts, as Dershowitz recommends, then some small solace can be found in the history of scholarship on ancient Judaism and early Christianity since Moore, in which precisely that type of analysis has grown in strength (Stendahl’s own work is an example), 43 and dramatically so in the decades since Sanders voiced his lament. As always, it will take far more than scholarship to counter large cultural and social forces, but, in the face of the new challenge, scholars should underestimate neither their own responsibilities nor the lessons embedded in the history of their own disciplines and the general enrichment that can come when Judaism has its own station and the study of it is pursued for its own sake.

A postscript: Although I have not intended these reflections as comprehensive and have necessarily omitted reference to several notable figures, I cannot close without mentioning one more. My own teacher, Frank Moore Cross (1921–2012), taught at Harvard Divinity School from 1957 until his retirement in 1992, holding the Hancock Professorship, by then in NELC, from 1958. Trained, like his father, as a Presbyterian minister, Cross presided over a genuinely nonconfessional program, which produced a large number of the most prominent Jewish figures in what is now the senior generation of Hebrew Bible scholars. Like Stendahl a great admirer and supporter of Jewish scholarship, he invited a number of prominent scholars from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to be visiting professors, including such influential figures as Moshe Goshen-Gottstein and Shemaryahu Talmon.

- This is also a tradition of immense historical importance to the emergence of ideas of religious tolerance in political thought, as brilliantly analyzed by Eric Nelson of Harvard’s Department of Government in The Hebrew Republic: Jewish Sources and the Transformation of European Political Thought (Harvard University Press, 2010).

- Samuel Eliot Morison, The Founding of Harvard College (Harvard University Press, 1935), 220–21. Morison thanks Harry A. Wolfson for tracking down the reference ( Mishneh Torah, Tefillah 11:14).

- Robert H. Pfeiffer, “The Teaching of Hebrew in Colonial America,” Jewish Quarterly Review 45 (1955): 363–73, at 369.

- Lee M. Friedman, “Judah Monis: First Instructor in Hebrew at Harvard University,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 22 (1914): 1–24, at 2–3.

- See Shalom Goldman, God’s Sacred Tongue: Hebrew and the American Imagination (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 41–45.

- “Rules and Statutes of the Professorships in the University at Cambridge” (Metcalf and Company, 1846), 7–8.

- William T. Baxter, The House of Hancock: Business in Boston, 1724–1775 (Harvard University Press, 1945), esp. 55–56, 69–74, and 114–18 .

- Baruch de Spinoza, A Theological-Political Tractate and Political Treatise (Dover Publications, 1951), 106 and 103. The Tractatus Theologico-Politicus was first published in 1670.

- www.harvardsquarelibrary.org/biographies/george-rapall-noyes . James de Normandie, “Memoir of Rev. Edward James Young, D.D.” in Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 44 (October 1910–June 1911): 529–42, at 531–32.

- D. G. Lyon, “Crawford Howell Toy,” Harvard Theological Review 13 (1920): 1–21.

- The name was changed in 1961 to Department of Near Eastern Languages and Literatures and then to its current name at some point in the early 1970s, when your humble—nay, overrated—scribe was a graduate student there.

- See David G. Lyon, “Semitic,” in The Development of Harvard University since the Inauguration of President Eliot, 1869–1929 , ed. Samuel Eliot Morison (Harvard University Press, 1930), 231–40.

- Ibid., 235.

- Willam Wallace Fenn, “George Foot Moore: A Memoir,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 64 (February 1932): 3–11, at 3.

- Quoted in Leo W. Schwarz, Wolfson of Harvard: Portrait of a Scholar (Jewish Publication Society of America, 5738/1978), 38–39, with no indication of the source of Moore’s quote.

- Samuel A. Meier, “Moore, George Foot (15 October 1851–16 May 1931),” American National Biography (online version, 2000), www.anb.org .

- George Foot Moore, “Christian Writers on Judaism,” Harvard Theological Review 14 (1921): 197–254.

- Ibid., 197.

- Ibid., 250.

- Ibid., 202.

- Ibid., 251. On this last point, see Nelson, The Hebrew Republic .

- Moore, “Christian Writers on Judaism,” 251–52. On the latter point, Moore refers specifically to Ferdinand Weber but certainly sees the pattern as much more general.

- Ibid., 252.

- E. P. Sanders, Paul and Palestinian Judaism: A Comparison of Patterns of Religion (Fortress Press, 1977), 56.

- Fenn, “George Foot Moore,” 8.

- For a fine introduction to this important subject, see now Chaim Saiman, Halakhah: The Rabbinic Idea of Law (Library of Jewish Studies; Princeton University Press, 2018).

- A very useful new introduction to the Talmud and contemporary scholarly approaches to it is Barry Scott Wimpfheimer, The Talmud: A Biography (Lives of Great Religious Books; Princeton University Press, 2018).

- Jacob Neusner, “ ‘Judaism’ after Moore: A Programmatic Statement,” Journal of Jewish Studies 31 (1980): 141–56, at 147. The whole article is a good discussion of what Neusner found inadequate in Moore’s procedures.

- Ibid., 142.

- Schwartz, Wolfson , 38–39, 49.

- Ibid., 171.

- Isadore Twersky, “Harry Austryn Wolfson, in Appreciation,” American Jewish Year Book 76 (1976): 99–111, at 107.

- Moore, “Christian Writers,” 241, n. 47. The second comment (on 241 itself) was made about Emil Schürer and Wilhelm Bousset.

- Sanders, Paul , 33.

- E.g., ibid., 55–56.

- Augustine, Contra Faustum 12:12.

- Jonathan Sacks, “A New Anti-Semitism,” Chesterton Review 30 (2004): 199–207, at 202–03. For more detail, in this case involving the revival of the adversus iudaeos tradition among liberal theologians in particular, see Adam Gregerman, “Old Wine in New Bottles: Liberation Theology and the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict,” Journal of Ecumenical Studies 41 (2004): 313–40, esp. 333–39; idem, “Israel as the ‘Hermeneutical Jew’ in Protestant Statements on the Land and State of Israel: Four Presbyterian examples,” Israel Affairs 23 (2017): 773–93 (Gregerman is an alumnus of Harvard Divinity School); and Jonathan Rynhold, The Arab-Israeli Conflict in American Political Culture (Cambridge University Press, 2015), esp. 130–31. Of course, the religious and racial versions of anti-Semitism are hardly incompatible and can readily energize each other. On this, see Susannah Heschel, The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany (Princeton University Press, 2008). The same can be said as well for the relationship of anti-Semitism and anti-Israelism.

- Alan Dershowitz, The Case for Israel (John Wiley & Sons, 2003), 1.

- For examples, see Gregerman, “Israel as the ‘Hermeneutical Jew.’ ” It is important to recognize that (1) a great many Christians have successfully rid themselves of the penchant to vilify or even demonize the Jews, and (2) one can be subject to that penchant without being a believing Christian.

- Krister Stendahl, “Judaism and Christianity II—After a Colloquium and a War,” Harvard Divinity Bulletin 1 (1967): 2–9, at 7. On the larger question of the range of Christian theological responses to the resumption of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel, see, for example, Adam Gregerman, “Comparative Christian Hermeneutical Approaches to the Land Promises to Abraham,” CrossCurrents 64 (2014): 410–25.

- See especially Stendahl’s influential essay, “The Apostle Paul and the Introspective Conscience of the West,” Harvard Theological Review 56 (1963): 199–215, reprinted in Paul among Jews and Gentiles (Fortress Press, 1976), 78–96.

Jon D. Levenson is the Albert A. List Professor of Jewish Studies at HDS. His many books include Resurrection and the Restoration of Israel: The Ultimate Victory of the God of Life (Yale University Press, 2006), which won a National Jewish Book Award, and The Love of God: Divine Gift, Human Gratitude, and Mutual Faithfulness in Judaism (Princeton University Press, 2015).

Please follow our Commentary Guidelines when engaging in discussion on this site.

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

About | Commentary Guidelines | Harvard University Privacy | Accessibility | Digital Accessibility | Trademark Notice | Reporting Copyright Infringements Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved.

A Guide to Jewish Studies: Literature

- Geographical Identities

- Denominations

- Gender and Judaism

- Commandments ( Mitzvot )

- Prayers & Liturgy

- Life-Cycle Events

- Jewish Calendar & Holidays

- Judaism in Antiquity

- Classical Rabbinical Period

- Medieval Period

- Early Modern Period

- Enlightenment and Industrial Age

- The Holocaust

- Judaism since 1945

- Rabbinic Literature

Visual Glossary

General resources, general resources - jewish literature, table of contents - jewish literature.

- General Resources - Literature

Holocaust Literature

Jewish American Literature

Literature by Women

Jewish Identities

- << Previous: Judaism since 1945

- Next: Rabbinic Literature >>

- Last Updated: Jun 9, 2023 6:02 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gustavus.edu/jewishstudies

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

What Makes Jewish Literature “Jewish”?

Ilan stavans on belonging, bookishness, and memory.

Is there a fundamental difference between Jewish literature and other literary traditions? Is it religion? A national quest? Antisemitism? A shared sense of history? What brings together books as disparate as Luis de Carvajal’s Autobiography , Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye’s Daughters , Isaac Babel’s Odessa Tales , Arthur’s Miller’s Death of a Salesman , Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem , Clarice Lispector’s Hour of the Star , Art Spiegelman’s Maus , and David Grossman’s To the End of the Land ? One explanation is that they come to us in translation. Another one is that what unites the authors is a shares sense of being outsiders—even when they are on the inside. The following excerpt, which comes from Jewish Literature: A Very Short Introduction , published this week by Oxford University Press, offers some context.

In a lecture titled “The Argentine Writer and Tradition,” delivered in Buenos Aires in 1951, Jorge Luis Borges, the author of a number of stories on Jewish themes, including “Death and the Compass,” “Emma Zunz,” and “The Secret Miracle,” argues, insightfully, that Argentine writers do not need to restrict themselves to local themes: tango, gauchos, maté , and so on. Instead, he states, “I believe our tradition is the entire Western culture, and I also believe we have a right to that tradition, equal to that of any other citizen in any Western nation.”

In other words, nationalism is a narrow proposition; its counterpart, cosmopolitanism, is a far better option. Borges then adds, “I remember here an essay by Thorstein Veblen, a United States sociologist, about the preeminence of the Jews in Western culture. He asks if this preeminence is due to an innate superiority of the Jews and he answers no; he says they distinguish themselves in Western culture because they act in that culture and at the same time do not feel tied to it by any particular devotion; that’s why, he says, ‘a Jew vis-à-vis a non-Jew will always find it easier to innovate in Western culture.’”

The claim Borges takes from Veblen to emphasize is a feature of Jewish literature: its aterritoriality. Literary critic George Steiner, an assiduous Borges reader, preferred the term extraterritorial . The difference is nuanced: aterritorial means outside a territory; extraterritorial means beyond it. Either way, the terms points to the outsiderness of Jews during their diasporic journey. Unlike, say, Argentine, French, Egyptian, or any other national literature, the one produced by Jews has no fixed address. That is because it does not have a specific geographic center; it might pop up anywhere in the globe, as long as suitable circumstances make it possible for it to thrive. This is not to say that Jews are not grounded in history. Quite the contrary: Jewish life, like anyone else’s, inevitably responds at the local level to concrete elements. Yet Jews tend to have a view of history that supersedes whatever homegrown defines them, seeing themselves as travelers across time and space.

My focus is modern Jewish literature in the broadest sense. I am interested in the ways it mutates while remaining the same, how it depends in translation in order to create a global sense of diasporic community. Jewish literature is Jewish because it distills a sensibility—bookish, impatient—that transcends geography. It also offers a feeling of belonging around certain puzzling existential questions. Made of bursts of consent and dissent, this literature is not concerned with divine revelation, like the Torah and Talmud, but with the rowdy display of human frailties. It springs from feeling ambivalent in terms of belonging. It is also marked by ceaseless migration. All this could spell disaster.

Yet Jews have turned these elements into a recipe for success. They have produced a stunning number of masterpieces, constantly redefining what we mean by literature. Indeed, one barometer to measure not only its health but also its diversity is the sheer number of recipients of the Nobel Prize for Literature since the award was established in Stockholm in 1895: more than a dozen, including Shmuel Yosef Agnon writing in Hebrew (1966), Saul Bellow in English (1976), Isaac Bashevis Singer in Yiddish (1978), Elias Canetti in German (1981), Joseph Brodsky in Russian (1987), Imre Kertész in Hungarian (2002), Patrick Modiano in French (2014), and Bob Dylan (2017) and Louise Glück (2020) in English.

With these many habitats, it is not surprising that Jewish literature might seem rowdy, amorphous, even unstable. It is thus important to ask, at the outset, two notoriously difficult questions: first, what is literature, and second, what makes this particular one Jewish? The answer to the first is nebulous. Jewish writers write stories, essays, novels, poems, memoirs, plays, letters, children’s books, and other similar artifacts. That is, they might be so-called professional writers. But they might also have other profiles. For instance, in awarding the Nobel Prize to Dylan, the Stockholm Committee celebrated his talent as a folk singer, that is, a musician and balladist. Equally, standup comedians such as Jackie Mason and Jerry Seinfeld are storytellers whose diatribes are infused with Jewish humor.

Graphic novelists like Art Spiegelman explore topics like the Holocaust in visual form, just like filmmakers such as Woody Allen deliver cinematic narratives bathed in Jewish pathos. Translation and the work of literary critics also fall inside the purview of Jewish literature. It could be said that such amorphous interpretation of literature undermines the entire transition; if the written word is what writers are about, evaluating everything else under the same criteria diminishes its value. Yet it must be recognized that, more than half a millennium after the invention of print, our definition of the word book as an object made of printed pages is obsolete. In the early 21st century, books appear in multiple forms.

I now turn to the second question: What makes a Jewish book Jewish? The answer depends on three elements: content, authorship, and readership. While none of these automatically makes a book Jewish, a combination of them surely does. Take, for example, Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice (1605). Shylock, its protagonist, might be said to be a sheer stereotype of a money lender, even though, in truth, he is an extraordinarily complex character who, in my view, ought to be seen as the playwright’s alter ego. Clearly, the play does not belong to the shelf of Jewish literature per se, despite its ingredients.

Now think of Kafka’s The Metamorphosis (1915), in which the protagonist, a middle-class man called Gregor Samsa, wakes up one morning, after uneasy dreams, to discover himself transformed into a giant Nowhere in the novella does the word Jew appear. Yet it is arguable, without struggle, that a Jewish sensibility permeates Samsa’s entire odyssey, from his feeling of psychological ostracism, within his family and in the larger society, to the perception that he inhabits a deformed, even monstrous body.

To unlock the Jewish content of a book, the reader, first, must be willing to do so. But readers are never neutral; they have a background and an agenda. It is surely possible to ignore Kafka’s Jewish sensibility, yet the moment one acknowledges it, his oeuvre magically opens up an array of unforeseen interpretations connecting it to Jewish tradition. Paul Celan, the German poet of “Todesfuge,” in an interview in the house of Yehuda Amichai, once said that “themes alone do not suffice to define what’s Jewish. Jewishness is, so to speak, a spiritual concern as well.” Hence, one approach might be what Austrian American novelist Walter Abish is looking for when asking “ Wie Deutsch ist es ?”: How German is this Prague-based writer?

Another approach is to move in the reverse direction, questioning how Jewish it is, without an address. Simple and straightforward, the plot line might be summarized in a couple of lines: the path of Jews as they embrace modernity, seen from their multifarious literature, is full of twists and turns, marked by episodes of intense euphoria and unspeakable grief; at times that path becomes a dead end, while at others it finds a resourcefulness capable of reinventing just about everything.

To the two questions just asked, a third needs to be added: What makes modern Jewish literature modern? The entrance of Jews into modernity signified a break with religion. According to some, this started to happen in 1517, when Martin Luther posted his Ninety-Five Theses and initiated the Protestant Revolution, which eliminated priests as the necessary intermediaries to God. Or perhaps it happened when, in the Renaissance, at roughly 1650—the date is a marker more than anything else—Europe as a civilization broke away from the long-held view that the ecclesiastical hierarchy justified everything.

In my view, the date ought to be 1492. That is when Christopher Columbus sailed across the Atlantic Ocean and the same year Jews were expelled from Spain. Large numbers of them and their descendants, persecuted as they were by the Spanish Inquisition, sought refuge in other lands, including the Americas, fostering a new age of discovery and free enterprise.

In any case, by 1789 the ideas of the French Revolution— liberté , egalité , fraternité —were seen as an invitation to all members of civil society, including Jews, to join ideals of tolerance in which an emerging bourgeoisie, the driving force against feudalism, promoted capitalism. New technologies brought innovation, including the movable letter type pioneered by Johannes Gutenberg, which made knowledge easier to disseminate. The outcome was a process of civic emancipation and the slow entrance of Jews to secular European culture—indeed, Jews were granted full civil rights within a few years of the French Revolution.

A well-known example of this journey, from the strictly defined religious milieu to the main stage of national culture, is Moses Mendelssohn, the 18th-century German philosopher, who, along with his numerous descendants, underwent a series of important transformations quantifiable as concrete wins and losses. A Haskalah champion, Mendelssohn, in his book Jerusalem (1783), argued for tolerance and against state interference in the affairs of its citizens, thus opening a debate in Europe about the parameters of tolerance. He translated the Bible into German: his version was called Bi’ur (Commentary) (1783).

Mendelssohn’s invitation for Jews to abandon a restricted life and become full-fledged members of European culture was a decisive event. It triumphantly opened the gates, so to speak, to an age of mutually respectful dialogue between a nation’s vast majority and its vulnerable minorities, the Jews among them. A couple of generations later, one of Mendelssohn’s grandchildren, German composer Felix Mendelssohn, known for an array of masterpieces like the opera Die Hochzeit des Camacho (1827), was at first raised outside the confines of the Jewish religion but eventually baptized as a Christian at the age of seven.

Such a transgenerational odyssey is emblematic of other European Jews: from devout belief to a secular, emancipated existence, from belonging to a small minority to active civil life as a minority within a majority. It is therefore crucial not to conflate modernity with Enlightenment: whereas the former is a historical development that fostered the quest for new markets through imperial endeavors that established, depending on the source, a satellite of colonies, the latter was the ideology behind it.