What does the scholarly research say about the effect of gender transition on transgender well-being?

We conducted a systematic literature review of all peer-reviewed articles published in English between 1991 and June 2017 that assess the effect of gender transition on transgender well-being. We identified 55 studies that consist of primary research on this topic, of which 51 (93%) found that gender transition improves the overall well-being of transgender people, while 4 (7%) report mixed or null findings. We found no studies concluding that gender transition causes overall harm. As an added resource, we separately include 17 additional studies that consist of literature reviews and practitioner guidelines.

Bottom Line

This search found a robust international consensus in the peer-reviewed literature that gender transition, including medical treatments such as hormone therapy and surgeries, improves the overall well-being of transgender individuals. The literature also indicates that greater availability of medical and social support for gender transition contributes to better quality of life for those who identify as transgender.

Below are the 8 findings of our review, and links to the 72 studies on which they are based. Click here to view our methodology . Click here for a printer-friendly one-pager of this research analysis .

Suggested Citation : What We Know Project, Cornell University, “What Does the Scholarly Research Say about the Effect of Gender Transition on Transgender Well-Being?” (online literature review), 2018.

Research Findings

1. The scholarly literature makes clear that gender transition is effective in treating gender dysphoria and can significantly improve the well-being of transgender individuals.

2. Among the positive outcomes of gender transition and related medical treatments for transgender individuals are improved quality of life, greater relationship satisfaction, higher self-esteem and confidence, and reductions in anxiety, depression, suicidality, and substance use.

3. The positive impact of gender transition on transgender well-being has grown considerably in recent years, as both surgical techniques and social support have improved.

4. Regrets following gender transition are extremely rare and have become even rarer as both surgical techniques and social support have improved. Pooling data from numerous studies demonstrates a regret rate ranging from .3 percent to 3.8 percent. Regrets are most likely to result from a lack of social support after transition or poor surgical outcomes using older techniques.

5. Factors that are predictive of success in the treatment of gender dysphoria include adequate preparation and mental health support prior to treatment, proper follow-up care from knowledgeable providers, consistent family and social support, and high-quality surgical outcomes (when surgery is involved).

6. Transgender individuals, particularly those who cannot access treatment for gender dysphoria or who encounter unsupportive social environments, are more likely than the general population to experience health challenges such as depression, anxiety, suicidality and minority stress. While gender transition can mitigate these challenges, the health and well-being of transgender people can be harmed by stigmatizing and discriminatory treatment.

7. An inherent limitation in the field of transgender health research is that it is difficult to conduct prospective studies or randomized control trials of treatments for gender dysphoria because of the individualized nature of treatment, the varying and unequal circumstances of population members, the small size of the known transgender population, and the ethical issues involved in withholding an effective treatment from those who need it.

8. Transgender outcomes research is still evolving and has been limited by the historical stigma against conducting research in this field. More research is needed to adequately characterize and address the needs of the transgender population.

Below are 51 studies that found that gender transition improves the well-being of transgender people. Click here to jump to 4 studies that contain mixed or null findings on the effect of gender transition on transgender well-being. Click here to jump to 17 studies that consist of literature reviews or guidelines that help advance knowledge about the effect of gender transition on transgender well-being.

Ainsworth and spiegel, 2010.

Ainsworth, T., & Spiegel, J. (2010). Quality of life of individuals with and without facial feminization surgery or gender reassignment surgery. Quality of Life Research , 19 (7), 1019-1024.

Objectives: To determine the self-reported quality of life of male-to-female (MTF) transgendered individuals and how this quality of life is influenced by facial feminization and gender reassignment surgery. Methods: Facial Feminization Surgery outcomes evaluation survey and the SF-36v2 quality of life survey were administered to male-to-female transgender individuals via the Internet and on paper. A total of 247 MTF participants were enrolled in the study. Results: Mental health-related quality of life was statistically diminished (P < 0.05) in transgendered women without surgical intervention compared to the general female population and transwomen who had gender reassignment surgery (GRS), facial feminization surgery (FFS), or both. There was no statistically significant difference in the mental health-related quality of life among transgendered women who had GRS, FFS, or both. Participants who had FFS scored statistically higher (P < 0.01) than those who did not in the FFS outcomes evaluation. Conclusions: Transwomen have diminished mental health-related quality of life compared with the general female population. However, surgical treatments (e.g. FFS, GRS, or both) are associated with improved mental health-related quality of life.

Bailey, Ellis, & McNeil, 2014

Bailey, L., Ellis, S. J., & McNeil, J. (2014). Suicide risk in the UK trans population and the role of gender transition in decreasing suicidal ideation and suicide attempt. The Mental Health Review , 19 (4), 209-220.

Purpose: The purpose of this paper is to present findings from the Trans Mental Health Study (McNeil et al., 2012) – the largest survey of the UK trans population to date and the first to explore trans mental health and well-being within a UK context. Findings around suicidal ideation and suicide attempt are presented and the impact of gender dysphoria, minority stress and medical delay, in particular, are highlighted. Design/methodology/approach: This represents a narrative analysis of qualitative sections of a survey that utilised both open and closed questions. The study drew on a non-random sample (n 1⁄4 889), obtained via a range of UK-based support organisations and services. Findings: The study revealed high rates of suicidal ideation (84 per cent lifetime prevalence) and attempted suicide (48 per cent lifetime prevalence) within this sample. A supportive environment for social transition and timely access to gender reassignment, for those who required it, emerged as key protective factors. Subsequently, gender dysphoria, confusion/denial about gender, fears around transitioning, gender reassignment treatment delays and refusals, and social stigma increased suicide risk within this sample. Research limitations/implications: Due to the limitations of undertaking research with this population, the research is not demographically representative. Practical implications: The study found that trans people are most at risk prior to social and/or medical transition and that, in many cases, trans people who require access to hormones and surgery can be left unsupported for dangerously long periods of time. The paper highlights the devastating impact that delaying or denying gender reassignment treatment can have and urges commissioners and practitioners to prioritise timely intervention and support. Originality/value: The first exploration of suicidal ideation and suicide attempt within the UK trans population revealing key findings pertaining to social and medical transition, crucial for policy makers, commissioners and practitioners working across gender identity services, mental health services and suicide prevention.

Bar et al., 2016

Bar, M. A., Jarus, T., Wada, M., Rechtman, L., & Noy, E. (2016). Male-to-female transitions: Implications for occupational performance, health, and life satisfaction. The Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy , 83 (2), 72-82.

Background. People who undergo a gender transition process experience changes in different everyday occupations. These changes may impact their health and life satisfaction. Purpose. This study examined the difference in the occupational performance history scales (occupational identity, competence, and settings) between male-to-female transgender women and cisgender women and the relation of these scales to health and life satisfaction. Method. Twenty-two transgender women and 22 matched cisgender women completed a demographic questionnaire and three reliable measures in this cross-sectional study. Data were analyzed using a two-way analysis of variance and multiple linear regressions. Findings. The results indicate lower performance scores for the transgender women. In addition, occupational settings and group membership (transgender and cisgender groups) were found to be predictors of life satisfaction. Implications. The present study supports the role of occupational therapy in promoting occupational identity and competence of transgender women and giving special attention to their social and physical environment.

Bodlund and Kullgren, 1996

Bodlund, O., & Kullgren, G. (1996). Transsexualism–general outcome and prognostic factors: A five-year follow-up study of nineteen transsexuals in the process of changing sex. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 25 (3), 303-316.

Nineteen transsexuals, approved for sex reassignement, were followed-up after 5 years. Outcome was evaluated as changes in seven areas of social, psychological, and psychiatric functioning. At baseline the patients were evaluated according to axis I, II, V (DSM-III-R), SCID screen, SASB (Structural Analysis of Social Behavior), and DMT (Defense Mechanism Test). At follow-up all but 1 were treated with contrary sex hormones, 12 had completed sex reassignment surgery, and 3 females were waiting for phalloplasty. One male transsexual regretted the decision to change sex and had quit the process. Two transsexuals had still not had any surgery due to older age or ambivalence. Overall, 68% (n = 13) had improved in at least two areas of functioning. In 3 cases (16%) outcome were judged as unsatisfactory and one of those regarded sex change as a failure. Another 3 patients were mainly unchanged after 5 years. Female transsexuals had a slightly better outcome, especially concerning establishing and maintaining partnerships and improvement in socio-economic status compared to male transsexuals. Baseline factors associated with negative outcome (unchanged or worsened) were presence of a personality disorder and high number of fulfilled axis II criteria. SCID screen assessments had high prognostic power. Negative self-image, according to SASB, predicted a negative outcome, whereas DMT variables were not correlated to outcome.

Bouman et al., 2016

Bouman, W. P., Claes, L., Marshall, E., Pinner, G. T., Longworth, J., et al. (2016). Sociodemographic variables, clinical features, and the role of preassessment cross-sex hormones in older trans people. The Journal of Sexual Medicine , 13 (4), 711-719.

Introduction: As referrals to gender identity clinics have increased dramatically over the last few years, no studies focusing on older trans people seeking treatment are available. Aims: The aim of this study was to investigate the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of older trans people attending a national service and to investigate the influence of cross-sex hormones (CHT) on psychopathology. Methods: Individuals over the age of 50 years old referred to a national gender identity clinic during a 30-month period were invited to complete a battery of questionnaires to measure psychopathology and clinical characteristics. Individuals on cross-sex hormones prior to the assessment were compared with those not on treatment for different variables measuring psychopathology. Main Outcome Measures: Sociodemographic and clinical variables and measures of depression and anxiety (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale), self-esteem (Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale), victimization (Experiences of Transphobia Scale), social support (Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support), interpersonal functioning (Inventory of Interpersonal Problems), and nonsuicidal self-injury (Self-Injury Questionnaire). Results: The sex ratio of trans females aged 50 years and older compared to trans males was 23.7:1. Trans males were removed for the analysis due to their small number (n = 3). Participants included 71 trans females over the age of 50, of whom the vast majority were white, employed or retired, and divorced and had children. Trans females on CHT who came out as trans and transitioned at an earlier age were significantly less anxious, reported higher levels of self-esteem, and presented with fewer socialization problems. When controlling for socialization problems, differences in levels of anxiety but not self-esteem remained. Conclusion: The use of cross-sex hormones prior to seeking treatment is widespread among older trans females and appears to be associated with psychological benefits. Existing barriers to access CHT for older trans people may need to be re-examined.

Boza and Nicholson, 2014

Boza, C., & Nicholson Perry, K. (2014). Gender-related victimization, perceived social support, and predictors of depression among transgender Australians. International Journal Of Transgenderism , 15 (1), 35-52.

This study examined mental health outcomes, gender-related victimization, perceived social support, and predictors of depression among 243 transgender Australians (n= 83 assigned female at birth, n= 160 assigned male at birth). Overall, 69% reported at least 1 instance of victimization, 59% endorsed depressive symptoms, and 44% reported a previous suicide attempt. Social support emerged as the most significant predictor of depressive symptoms (p>.05), whereby persons endorsing higher levels of overall perceived social support tended to endorse lower levels of depressive symptoms. Second to social support, persons who endorsed having had some form of gender affirmative surgery were significantly more likely to present with lower symptoms of depression. Contrary to expectations, victimization did not reach significance as an independent risk factor of depression (p=.053). The pervasiveness of victimization, depression, and attempted suicide represents a major health concern and highlights the need to facilitate culturally sensitive health care provision.

Budge et al., 2013

Budge, S. L., Katz-Wise, S. L., Tebbe, E. N., Howard, K. A. S., Schneider, C. L., et al. (2013). Transgender emotional and coping processes: Facilitative and avoidant coping throughout gender transitioning. The Counseling Psychologist , 41 (4), 601-647.

Eighteen transgender-identified individuals participated in semi-structured interviews regarding emotional and coping processes throughout their gender transition. The authors used grounded theory to conceptualize and analyze the data. There were three distinct phases through which the participants described emotional and coping experiences: (a) pretransition, (b) during the transition, and (c) posttransition. Five separate themes emerged, including descriptions of coping mechanisms, emotional hardship, lack of support, positive social support, and affirmative emotional experiences. The authors developed a model to describe the role of coping mechanisms and support experienced throughout the transition process. As participants continued through their transitions, emotional hardships lessened and they used facilitative coping mechanisms that in turn led to affirmative emotional experiences. The results of this study are indicative of the importance of guiding transgender individuals through facilitative coping experiences and providing social support throughout the transition process. Implications for counselors and for future research are discussed.

Cardoso da Silva et al., 2016

Cardoso da Silva, D., Schwarz, K., Fontanari, A.M.V., Costa, A.B., Massuda, R., et al. (2016). WHOQOL-100 Before and after sex reassignment surgery in Brazilian male-to-female transsexual individuals. Journal of Sexual Medicine , 13 (6), 988-993.

Introduction: The 100-item World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL-100) evaluates quality of life as a subjective and multidimensional construct. Currently, particularly in Brazil, there are controversies concerning quality of life after sex reassignment surgery (SRS). Aim: To assess the impact of surgical interventions on quality of life of 47 Brazilian male-to-female transsexual individuals using the WHOQOL-100. Methods: This was a prospective cohort study using the WHOQOL-100 and sociodemographic questions for individuals diagnosed with gender identity disorder according to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. The protocol was used when a transsexual person entered the ambulatory clinic and at least 12 months after SRS. Main Outcome Measures: Initially, improvement or worsening of quality of life was assessed using 6 domains and 24 facets. Subsequently, quality of life was assessed for individuals who underwent new surgical interventions and those who did not undergo these procedures 1 year after SRS. Results: The participants showed significant improvement after SRS in domains II (psychological) and IV (social relationships) of the WHOQOL-100. In contrast, domains I (physical health) and III (level of independence) were significantly worse after SRS. Individuals who underwent additional surgery had a decrease in quality of life reflected in domains II and IV. During statistical analysis, all results were controlled for variations in demographic characteristics, without significant results. Conclusion: The WHOQOL-100 is an important instrument to evaluate the quality of life of male-to-female transsexuals during different stages of treatment. SRS promotes the improvement of psychological aspects and social relationships. However, even 1 year after SRS, male-to-female transsexuals continue to report problems in physical health and difficulty in recovering their independence.

(Due to a citation error, this study was initially listed twice.)

Castellano et al., 2015

Castellano, E., Crespi, C., Dell’Aquila, R., Rosato, C., Catalano, V., et al. (2015). Quality of life and hormones after sex reassignment surgery. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation , 38 (12), 1373-1381.

Background: Transpeople often look for sex reassignment surgery (SRS) to improve their quality of life (QoL). The hormonal therapy has many positive effects before and after SRS. There are no studies about correlation between hormonal status and QoL after SRS. Aim: To gather information on QoL, quality of sexual life and body image in transpeople at least 2 years after SRS, to compare these results with a control group and to evaluate the relations between the chosen items and hormonal status. Subjects and methods: Data from 60 transsexuals and from 60 healthy matched controls were collected. Testosterone, estradiol, LH and World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-100) self-reported questionnaire were evaluated. Student’s t test was applied to compare transsexuals and controls. Multiple regression model was applied to evaluate WHOQOL’s chosen items and LH. Results: The QoL and the quality of body image scores in transpeople were not statistically different from the matched control groups’ ones. In the sexual life subscale, transwomen’s scores were similar to biological women’s ones, whereas transmen’s scores were statistically lower than biological men’s ones (P = 0.003). The quality of sexual life scored statistically lower in transmen than in transwomen (P = 0.048). A significant inverse relationship between LH and body image and between LH and quality of sexual life was found. Conclusions: This study highlights general satisfaction after SRS. In particular, transpeople’s QoL turns out to be similar to Italian matched controls. LH resulted inversely correlated to body image and sexual life scores.

Colizzi, Costa, & Todarello, 2014

Colizzi, M., Costa, R. & Todarello, O. (2014). Transsexual patients’ psychiatric comorbidity and positive effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on mental health: Results from a longitudinal study. Psychoneuroendocrinology , 39 , 65-73.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the presence of psychiatric diseases/symptoms in transsexual patients and to compare psychiatric distress related to the hormonal intervention in a one year follow-up assessment. We investigated 118 patients before starting the hormonal therapy and after about 12 months. We used the SCID-I to determine major mental disorders and functional impairment. We used the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and the Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) for evaluating self-reported anxiety and depression. We used the Symptom Checklist 90-R (SCL-90-R) for assessing self-reported global psychological symptoms. Seventeen patients (14%) had a DSM-IV-TR axis I psychiatric comorbidity. At enrollment the mean SAS score was above the normal range. The mean SDS and SCL-90-R scores were on the normal range except for SCL-90-R anxiety subscale. When treated, patients reported lower SAS, SDS and SCL-90-R scores, with statistically significant differences. Psychiatric distress and functional impairment were present in a significantly higher percentage of patients before starting the hormonal treatment than after 12 months (50% vs. 17% for anxiety; 42% vs. 23% for depression; 24% vs. 11% for psychological symptoms; 23% vs. 10% for functional impairment). The results revealed that the majority of transsexual patients have no psychiatric comorbidity, suggesting that transsexualism is not necessarily associated with severe comorbid psychiatric findings. The condition, however, seemed to be associated with subthreshold anxiety/depression, psychological symptoms and functional impairment. Moreover, treated patients reported less psychiatric distress. Therefore, hormonal treatment seemed to have a positive effect on transsexual patients’ mental health.

Colizzi et al., 2013

Colizzi. M., Costa, R., Pace, V., & Todarello, O. (2013). Hormonal treatment reduces psychobiological distress in gender identity disorder, independently of the attachment style. The Journal of Sexual Medicine , 10 (12), 3049–3058.

Introduction: Gender identity disorder may be a stressful situation. Hormonal treatment seemed to improve the general health as it reduces psychological and social distress. The attachment style seemed to regulate distress in insecure individuals as they are more exposed to hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal system dysregulation and subjective stress. Aim: The objectives of the study were to evaluate the presence of psychobiological distress and insecure attachment in transsexuals and to study their stress levels with reference to the hormonal treatment and the attachment pattern. Methods: We investigated 70 transsexual patients. We measured the cortisol levels and the perceived stress before starting the hormonal therapy and after about 12 months. We studied the representation of attachment in transsexuals by a backward investigation in the relations between them and their caregivers. Main Outcome Measures: We used blood samples for assessing cortisol awakening response (CAR); we used the Perceived Stress Scale for evaluating self‐reported perceived stress and the Adult Attachment Interview to determine attachment styles. Results: At enrollment, transsexuals reported elevated CAR; their values were out of normal. They expressed higher perceived stress and more attachment insecurity, with respect to normative sample data. When treated with hormone therapy, transsexuals reported significantly lower CAR (P < 0.001), falling within the normal range for cortisol levels. Treated transsexuals showed also lower perceived stress (P < 0.001), with levels similar to normative samples. The insecure attachment styles were associated with higher CAR and perceived stress in untreated transsexuals (P < 0.01). Treated transsexuals did not expressed significant differences in CAR and perceived stress by attachment. Conclusion: Our results suggested that untreated patients suffer from a higher degree of stress and that attachment insecurity negatively impacts the stress management. Initiating the hormonal treatment seemed to have a positive effect in reducing stress levels, whatever the attachment style may be.

Colton-Meier et al., 2011

Colton-Meier, S. L., Fitzgerald, K. M., Pardo, S. T., & Babcock, J. (2011). The effects of hormonal gender affirmation treatment on mental health in female-to-male transsexuals. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health , 15 (3), 281-299.

Hormonal interventions are an often-sought option for transgender individuals seeking to medically transition to an authentic gender. Current literature stresses that the effects and associated risks of hormone regimens should be monitored and well understood by health care providers (Feldman & Bockting, 2003). However, the positive psychological effects following hormone replacement therapy as a gender affirming treatment have not been adequately researched. This study examined the relationship of hormone replacement therapy, specifically testosterone, with various mental health outcomes in an Internet sample of more than 400 self-identified female-to-male transsexuals. Results of the study indicate that female-to-male transsexuals who receive testosterone have lower levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, and higher levels of social support and health related quality of life. Testosterone use was not related to problems with drugs, alcohol, or suicidality. Overall findings provide clear evidence that HRT is associated with improved mental health outcomes in female-to-male transsexuals.

Costantino et al., 2013

Costantino, A., Cerpolini, S., Alvisi, S., Morselli, P. G., Venturoli, S., & Meriggiola, M. C. (2013). A prospective study on sexual function and mood in female-to-male transsexuals during testosterone administration and after sex reassignment surgery. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy , 39 (4), 321-335.

Testosterone administration in female-to-male transsexual subjects aims to develop and maintain the characteristics of the desired sex. Very little data exists on its effects on sexuality of female-to-male transsexuals. The aim of this study was to evaluate sexual function and mood of female-to-male transsexuals from their first visit, throughout testosterone administration and after sex reassignment surgery. Participants were 50 female-to-male transsexual subjects who completed questionnaires assessing sexual parameters and mood. The authors measured reproductive hormones and hematological parameters. The results suggest a positive effect of testosterone treatment on sexual function and mood in female-to-male transsexual subjects.

Davis and Meier, 2014

Davis, S. A. & Meier, S. C. (2014). Effects of testosterone treatment and chest reconstruction surgery on mental health and sexuality in female-to-male transgender people. International Journal of Sexual Health , 26 (2), 113-128.

Objectives: This study examined the effects of testosterone treatment with or without chest reconstruction surgery (CRS) on mental health in female-to-male transgender people (FTMs). Methods: More than 200 FTMs completed a written survey including quantitative scales to measure symptoms of anxiety and depression, feelings of anger, and body dissatisfaction, as well as qualitative questions assessing shifts in sexuality after the initiation of testosterone. Fifty-seven percent of participants were taking testosterone and 40% had undergone CRS. Results: Cross-sectional analysis using a between-subjects multivariate analysis of variance showed that participants who were receiving testosterone endorsed fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression as well as less anger than the untreated group. Participants who had CRS in addition to testosterone reported less body dissatisfaction than both the testosterone-only or the untreated groups. Furthermore, participants who were injecting testosterone on a weekly basis showed significantly less anger compared with those injecting every other week. In qualitative reports, more than 50% of participants described increased sexual attraction to nontransgender men after taking testosterone. Conclusions: Results indicate that testosterone treatment in FTMs is associated with a positive effect on mental health on measures of depression, anxiety, and anger, while CRS appears to be more important for the alleviation of body dissatisfaction. The findings have particular relevance for counselors and health care providers serving FTM and gender-variant people considering medical gender transition.

De Cuypere et al., 2006

De Cuypere, G., Elaut, E., Heylens, G., Maele, G. V., Selvaggi, G., et al. (2006). Long-term follow-up: Psychosocial outcome of Belgian transsexuals after sex reassignment surgery. Sexologies , 15 (2), 126-133.

Background: To establish the benefit of sex reassignment surgery (SRS) for persons with a gender identity disorder, follow-up studies comprising large numbers of operated transsexuals are still needed. Aims: The authors wanted to assess how the transsexuals who had been treated by the Ghent multidisciplinary gender team since 1985, were functioning psychologically, socially and professionally after a longer period. They also explored some prognostic factors with a view to refining the procedure. Method: From 107 Dutch-speaking transsexuals who had undergone SRS between 1986 and 2001, 62 (35 male-to-females and 27 female-to-males) completed various questionnaires and were personally interviewed by researchers, who had not been involved in the subjects’ initial assessment or treatment. Results: On the GAF (DSM-IV) scale the female-to-male transsexuals scored significantly higher than the male-to-females (85.2 versus 76.2). While no difference in psychological functioning (SCL-90) was observed between the study group and a normal population, subjects with a pre-existing psychopathology were found to have retained more psychological symptoms. The subjects proclaimed an overall positive change in their family and social life. None of them showed any regrets about the SRS. A homosexual orientation, a younger age when applying for SRS, and an attractive physical appearance were positive prognostic factors. Conclusion: While sex reassignment treatment is an effective therapy for transsexuals, also in the long term, the postoperative transsexual remains a fragile person in some respects.

Dhejne et al., 2014

Dhejne, C., Öberg, K., Arver, S., & Landén, M. (2014). An analysis of all applications for sex reassignment surgery in sweden, 1960-2010: Prevalence, incidence, and regrets. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 43 (8), 1535-1545.

Incidence and prevalence of applications in Sweden for legal and surgical sex reassignment were examined over a 50-year period (1960-2010), including the legal and surgical reversal applications. A total of 767 people (289 natal females and 478 natal males) applied for legal and surgical sex reassignment. Out of these, 89 % (252 female-to-males [FM] and 429 male-to-females [MF]) received a new legal gender and underwent sex reassignment surgery (SRS). A total of 25 individuals (7 natal females and 18 natal males), equaling 3.3 %, were denied a new legal gender and SRS. The remaining withdrew their application, were on a waiting list for surgery, or were granted partial treatment. The incidence of applications was calculated and stratified over four periods between 1972 and 2010. The incidence increased significantly from 0.16 to 0.42/100,000/year (FM) and from 0.23 to 0.73/100,000/year (MF). The most pronounced increase occurred after 2000. The proportion of FM individuals 30 years or older at the time of application remained stable around 30 %. In contrast, the proportion of MF individuals 30 years or older increased from 37 % in the first decade to 60 % in the latter three decades. The point prevalence at December 2010 for individuals who applied for a new legal gender was for FM 1:13,120 and for MF 1:7,750. The FM:MF sex ratio fluctuated but was 1:1.66 for the whole study period. There were 15 (5 MF and 10 MF) regret applications corresponding to a 2.2 % regret rate for both sexes. There was a significant decline of regrets over the time period.

Eldh, Berg, & Gustafsson, 1997

Eldh, J., Berg, A., Gustafsson, M. (1997). Long-term follow up after sex reassignment surgery. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery , 27 (1), 39-45.

A long-term follow up of 136 patients operated on for sex reassignment was done to evaluate the surgical outcome. Social and psychological adjustments were also investigated by a questionnaire in 90 of these 136 patients. Optimal results of the operation are essential for a successful outcome. Personal and social instability before operation, unsuitable body build, and age over 30 years at operation correlated with unsatisfactory results. Adequate family and social support is important for postoperative functioning. Sex reassignment had no influence on the person’s ability to work.

Fisher et al., 2014

Fisher, A. D., Castellini, G., Bandini, E., Casale, H., Fanni, E., et al. (2014). Cross‐sex hormonal treatment and body uneasiness in individuals with gender dysphoria. The Journal of Sexual Medicine , 11 (3), 709–719.

Introduction: Cross‐sex hormonal treatment (CHT) used for gender dysphoria (GD) could by itself affect well‐being without the use of genital surgery; however, to date, there is a paucity of studies investigating the effects of CHT alone. Aims: This study aimed to assess differences in body uneasiness and psychiatric symptoms between GD clients taking CHT and those not taking hormones (no CHT). A second aim was to assess whether length of CHT treatment and daily dose provided an explanation for levels of body uneasiness and psychiatric symptoms. Methods: A consecutive series of 125 subjects meeting the criteria for GD who not had genital reassignment surgery were considered. Main Outcome Measures: Subjects were asked to complete the Body Uneasiness Test (BUT) to explore different areas of body‐related psychopathology and the Symptom Checklist‐90 Revised (SCL‐90‐R) to measure psychological state. In addition, data on daily hormone dose and length of hormonal treatment (androgens, estrogens, and/or antiandrogens) were collected through an analysis of medical records. Results: Among the male‐to‐female (MtF) individuals, those using CHT reported less body uneasiness compared with individuals in the no‐CHT group. No significant differences were observed between CHT and no‐CHT groups in the female‐to‐male (FtM) sample. Also, no significant differences in SCL score were observed with regard to gender (MtF vs. FtM), hormone treatment (CHT vs. no‐CHT), or the interaction of these two variables. Moreover, a two‐step hierarchical regression showed that cumulative dose of estradiol (daily dose of estradiol times days of treatment) and cumulative dose of androgen blockers (daily dose of androgen blockers times days of treatment) predicted BUT score even after controlling for age, gender role, cosmetic surgery, and BMI. Conclusions: The differences observed between MtF and FtM individuals suggest that body‐related uneasiness associated with GD may be effectively diminished with the administration of CHT even without the use of genital surgery for MtF clients. A discussion is provided on the importance of controlling both length and daily dose of treatment for the most effective impact on body uneasiness.

Glynn et al., 2016

Glynn, T. R., Gamarel, K. E., Kahler, C. W., Iwamoto, M., Operario, D., & Nemoto, T. (2016). The role of gender affirmation in psychological well-being among transgender women. Psychology Of Sexual Orientation And Gender Diversity , 3 (3), 336-344.

High prevalence of psychological distress, including greater depression, lower self-esteem, and suicidal ideation, has been documented across numerous samples of transgender women and has been attributed to high rates of discrimination and violence. According to the gender affirmation framework (Sevelius, 2013), access to sources of gender-affirmative support can offset such negative psychological effects of social oppression. However, critical questions remain unanswered in regards to how and which aspects of gender affirmation are related to psychological well-being. The aims of this study were to investigate the associations among 3 discrete areas of gender affirmation (psychological, medical, and social) and participants’ reports of psychological well-being. A community sample of 573 transgender women with a history of sex work completed a 1-time self-report survey that assessed demographic characteristics, gender affirmation, and mental health outcomes. In multivariate models, we found that social, psychological, and medical gender affirmation were significant predictors of lower depression and higher self-esteem whereas no domains of affirmation were significantly associated with suicidal ideation. Findings support the need for accessible and affordable transitioning resources for transgender women to promote better quality of life among an already vulnerable population. However, transgender individuals should not be portrayed simplistically as objects of vulnerability, and research identifying mechanisms to promote wellness and thriving is necessary for future intervention development. As the gender affirmation framework posits, the personal experience of feeling affirmed as a transgender person results from individuals’ subjective perceptions of need along multiple dimensions of gender affirmation. Thus, personalized assessment of gender affirmation may be a useful component of counseling and service provision for transgender women.

Gomez-Gil et al., 2012

Gomez-Gil, E., Zubiaurre-Elorz, L., Esteva, I., Guillamon, A., Godas, T., Cruz Almaraz, M., Halperin, I., Salamero, M. (2012). Hormone-treated transsexuals report less social distress, anxiety and depression. Psychoneuroendocrinology , 37 (5), 662-670.

Introduction: The aim of the present study was to evaluate the presence of symptoms of current social distress, anxiety and depression in transsexuals. Methods: We investigated a group of 187 transsexual patients attending a gender identity unit; 120 had undergone hormonal sex-reassignment (SR) treatment and 67 had not. We used the Social Anxiety and Distress Scale (SADS) for assessing social anxiety and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) for evaluating current depression and anxiety. Results: The mean SADS and HADS scores were in the normal range except for the HAD-Anxiety subscale (HAD-A) on the non-treated transsexual group. SADS, HAD-A, and HAD-Depression (HAD-D) mean scores were significantly higher among patients who had not begun cross-sex hormonal treatment compared with patients in hormonal treatment (F = 4.362, p = .038; F = 14.589, p = .001; F = 9.523, p = .002 respectively). Similarly, current symptoms of anxiety and depression were present in a significantly higher percentage of untreated patients than in treated patients (61% vs. 33% and 31% vs. 8% respectively). Conclusions: The results suggest that most transsexual patients attending a gender identity unit reported subclinical levels of social distress, anxiety, and depression. Moreover, patients under cross-sex hormonal treatment displayed a lower prevalence of these symptoms than patients who had not initiated hormonal therapy. Although the findings do not conclusively demonstrate a direct positive effect of hormone treatment in transsexuals, initiating this treatment may be associated with better mental health of these patients.

Gomez-Gil et al., 2014

Gómez-Gil, E., Zubiaurre-Elorza, L., de Antonio, E. D., Guillamon, A., & Salamero, M. (2014). Determinants of quality of life in Spanish transsexuals attending a gender unit before genital sex reassignment surgery. Quality of Life Research , 23 (2), 669-676.

Purpose: To evaluate the self-reported perceived quality of life (QoL) in transsexuals attending a Spanish gender identity unit before genital sex reassignment surgery, and to identify possible determinants that likely contribute to their QoL. Methods: A sample of 119 male-to-female (MF) and 74 female-to-male (FM) transsexuals were included in the study. The WHOQOL-BREF scale was used to evaluate self-reported QoL. Possible determinants included age, sex, education, employment, partnership status, undergoing cross-sex hormonal therapy, receiving at least one non-genital sex reassignment surgery, and family support (assessed with the family APGAR questionnaire). Results: Mean scores of all QoL domains ranged from 55.44 to 63.51. Linear regression analyses revealed that undergoing cross-sex hormonal treatment, having family support, and having an occupation were associated with a better QoL for all transsexuals. FM transsexuals have higher social domain QoL scores than MF transsexuals. The model accounts for 20.6 % of the variance in the physical, 32.5 % in the psychological, 21.9 % in the social, and 20.1 % in the environment domains, and 22.9 % in the global QoL factor. Conclusions: Cross-sex hormonal treatment, family support, and working or studying are linked to a better self-reported QoL in transsexuals. Healthcare providers should consider these factors when planning interventions to promote the health-related QoL of transsexuals.

Gorin-Lazard et al., 2012

Gorin‐Lazard, A., Baumstarck, K., Boyer, L., Maquigneau, A., Gebleux, S., Penochet, J., Pringuey, D., Albarel, F., Morange, I., Loundou, A., Berbis, J., Auquier, P., Lançon, C. and Bonierbale, M. (2012). Is hormonal therapy associated with better quality of life in transsexuals? A cross‐sectional study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine , 9 (2), 531–541.

Introduction: Although the impact of sex reassignment surgery on the self‐reported outcomes of transsexuals has been largely described, the data available regarding the impact of hormone therapy on the daily lives of these individuals are scarce. Aims: The objectives of this study were to assess the relationship between hormonal therapy and the self‐reported quality of life (QoL) in transsexuals while taking into account the key confounding factors and to compare the QoL levels between transsexuals who have, vs. those who have not, undergone cross‐sex hormone therapy as well as between transsexuals and the general population (French age‐ and sex‐matched controls). Methods: This study incorporated a cross‐sectional design that was conducted in three psychiatric departments of public university teaching hospitals in France. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 18 years or older, diagnosis of gender identity disorder (302.85) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fourth edition text revision (DSM‐IV TR), inclusion in a standardized sex reassignment procedure following the agreement of a multidisciplinary team, and pre‐sex reassignment surgery. Main Outcome Measure. QoL was assessed using the Short Form 36 (SF‐36). Results: The mean age of the total sample was 34.7 years, and the sex ratio was 1:1. Forty‐four (72.1%) of the participants received hormonal therapy. Hormonal therapy and depression were independent predictive factors of the SF‐36 mental composite score. Hormonal therapy was significantly associated with a higher QoL, while depression was significantly associated with a lower QoL. Transsexuals’ QoL, independently of hormonal status, did not differ from the French age‐ and sex‐matched controls except for two subscales of the SF‐36 questionnaire: role physical (lower scores in transsexuals) and general health (lower scores in controls). Conclusion: The present study suggests a positive effect of hormone therapy on transsexuals’ QoL after accounting for confounding factors. These results will be useful for healthcare providers of transgender persons but should be confirmed with larger samples using a prospective study design.

Gorin-Lazard et al., 2013

Gorin-Lazard, A., Baumstarck, K., Boyer, L., Maquigneau, A., Penochet, J. C., et al. (2013). Hormonal therapy is associated with better self-esteem, mood, and quality of life in transsexuals. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease , 201 (11), 996–1000.

Few studies have assessed the role of cross-sex hormones on psychological outcomes during the period of hormonal therapy preceding sex reassignment surgery in transsexuals. The objective of this study was to assess the relationship between hormonal therapy, self-esteem, depression, quality of life (QoL), and global functioning. This study incorporated a cross-sectional design. The inclusion criteria were diagnosis of gender identity disorder (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision) and inclusion in a standardized sex reassignment procedure. The outcome measures were self-esteem (Social Self-Esteem Inventory), mood (Beck Depression Inventory), QoL (Subjective Quality of Life Analysis), and global functioning (Global Assessment of Functioning). Sixty-seven consecutive individuals agreed to participate. Seventy-three percent received hormonal therapy. Hormonal therapy was an independent factor in greater self-esteem, less severe depression symptoms, and greater “psychological-like” dimensions of QoL. These findings should provide pertinent information for health care providers who consider this period as a crucial part of the global sex reassignment procedure.

Hess et al., 2014

Hess, J., Neto, R. R., Panic, L., Rübben, H., & Senf, W. (2014). Satisfaction with male-to-female gender reassignment surgery: Results of a retrospective analysis. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International , 111 (47), 795–801.

Background: The frequency of gender identity disorder is hard to determine; the number of gender reassignment operations and of court proceedings in accordance with the German Law on Transsexuality almost certainly do not fully reflect the underlying reality. There have been only a few studies on patient satisfaction with male-to-female gender reassignment surgery. Methods: 254 consecutive patients who had undergone male-to-female gender reassignment surgery at Essen University Hospital’s Department of Urology retrospectively filled out a questionnaire about their subjective postoperative satisfaction. Results: 119 (46.9%) of the patients filled out and returned the questionnaires, at a mean of 5.05 years after surgery (standard deviation 1.61 years, range 1–7 years). 90.2% said their expectations for life as a woman were fulfilled postoperatively. 85.4% saw themselves as women. 61.2% were satisfied, and 26.2% very satisfied, with their outward appearance as a woman; 37.6% were satisfied, and 34.4% very satisfied, with the functional outcome. 65.7% said they were satisfied with their life as it is now. Conclusion: The very high rates of subjective satisfaction and the surgical outcomes indicate that gender reassignment surgery is beneficial. These findings must be interpreted with caution, however, because fewer than half of the questionnaires were returned.

Heylens et al., 2014

Heylens, G., Verroken, C., De Cock, S., T’Sjoen, G., & De Cuypere, G. (2014). Effects of different steps in gender reassignment therapy on psychopathology: a prospective study of persons with a gender identity disorder. The Journal of Sexual Medicine , 11 (1), 119–126.

Introduction: At the start of gender reassignment therapy, persons with a gender identity disorder (GID) may deal with various forms of psychopathology. Until now, a limited number of publications focus on the effect of the different phases of treatment on this comorbidity and other psychosocial factors. Aims: The aim of this study was to investigate how gender reassignment therapy affects psychopathology and other psychosocial factors. Methods: This is a prospective study that assessed 57 individuals with GID by using the Symptom Checklist‐90 (SCL‐90) at three different points of time: at presentation, after the start of hormonal treatment, and after sex reassignment surgery (SRS). Questionnaires on psychosocial variables were used to evaluate the evolution between the presentation and the postoperative period. The data were statistically analyzed by using SPSS 19.0, with significance levels set at P < 0.05. Main Outcome Measures: The psychopathological parameters include overall psychoneurotic distress, anxiety, agoraphobia, depression, somatization, paranoid ideation/psychoticism, interpersonal sensitivity, hostility, and sleeping problems. The psychosocial parameters consist of relationship, living situation, employment, sexual contacts, social contacts, substance abuse, and suicide attempt. Results: A difference in SCL‐90 overall psychoneurotic distress was observed at the different points of assessments (P = 0.003), with the most prominent decrease occurring after the initiation of hormone therapy (P < 0.001). Significant decreases were found in the subscales such as anxiety, depression, interpersonal sensitivity, and hostility. Furthermore, the SCL‐90 scores resembled those of a general population after hormone therapy was initiated. Analysis of the psychosocial variables showed no significant differences between pre‐ and postoperative assessments. Conclusions: A marked reduction in psychopathology occurs during the process of sex reassignment therapy, especially after the initiation of hormone therapy.

Imbimbo et al., 2009

Imbimbo, C., Verze, P., Palmieri, A., Longo, N., Fusco, F., Arcaniolo, D., & Mirone, V. (2009). A report from a single institute’s 14-year experience in treatment of male-to-female transsexuals. The Journal of Sexual Medicine , 6 (10), 2736–2745.

Introduction: Gender identity disorder or transsexualism is a complex clinical condition, and prevailing social context strongly impacts the form of its manifestations. Sex reassignment surgery (SRS) is the crucial step of a long and complex therapeutic process starting with preliminary psychiatric evaluation and culminating in definitive gender identity conversion. Aim: The aim of our study is to arrive at a clinical and psychosocial profile of male-to-female transsexuals in Italy through analysis of their personal and clinical experience and evaluation of their postsurgical satisfaction levels SRS. Methods: From January 1992 to September 2006, 163 male patients who had undergone gender-transforming surgery at our institution were requested to complete a patient satisfaction questionnaire. Main Outcome Measures: The questionnaire consisted of 38 questions covering nine main topics: general data, employment status, family status, personal relationships, social and cultural aspects, presurgical preparation, surgical procedure, and postsurgical sex life and overall satisfaction. Results: Average age was 31 years old. Seventy-two percent had a high educational level, and 63% were steadily employed. Half of the patients had contemplated suicide at some time in their lives before surgery and 4% had actually attempted suicide. Family and colleague emotional support levels were satisfactory. All patients had been adequately informed of surgical procedure beforehand. Eighty-nine percent engaged in postsurgical sexual activities. Seventy-five percent had a more satisfactory sex life after SRS, with main complications being pain during intercourse and lack of lubrication. Seventy-eight percent were satisfied with their neovagina’s esthetic appearance, whereas only 56% were satisfied with depth. Almost all of the patients were satisfied with their new sexual status and expressed no regrets. Conclusions: Our patients’ high level of satisfaction was due to a combination of a well-conducted preoperative preparation program, competent surgical skills, and consistent postoperative follow-up.

Johansson et al., 2010

Johansson, A., Sundbom, E., Höjerback, T., & Bodlund, O. (2010). A five-year follow-up study of Swedish adults with gender identity disorder. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 39 (6), 1429-1437.

This follow-up study evaluated the outcome of sex reassignment as viewed by both clinicians and patients, with an additional focus on the outcome based on sex and subgroups. Of a total of 60 patients approved for sex reassignment, 42 (25 male-to-female [MF] and 17 female-to-male [FM]) transsexuals completed a follow-up assessment after 5 or more years in the process or 2 or more years after completed sex reassignment surgery. Twenty-six (62%) patients had an early onset and 16 (38%) patients had a late onset; 29 (69%) patients had a homosexual sexual orientation and 13 (31%) patients had a non-homosexual sexual orientation (relative to biological sex). At index and follow-up, a semi-structured interview was conducted. At follow-up, 32 patients had completed sex reassignment surgery, five were still in process, and five—following their own decision—had abstained from genital surgery. No one regretted their reassignment. The clinicians rated the global outcome as favorable in 62% of the cases, compared to 95% according to the patients themselves, with no differences between the subgroups. Based on the follow-up interview, more than 90% were stable or improved as regards work situation, partner relations, and sex life, but 5–15% were dissatisfied with the hormonal treatment, results of surgery, total sex reassignment procedure, or their present general health. Most outcome measures were rated positive and substantially equal for MF and FM. Late-onset transsexuals differed from those with early onset in some respects: these were mainly MF (88 vs. 42%), older when applying for sex reassignment (42 vs. 28 years), and non-homosexually oriented (56 vs. 15%). In conclusion, almost all patients were satisfied with the sex reassignment; 86% were assessed by clinicians at follow-up as stable or improved in global functioning.

Keo-Meier et al., 2015

Keo-Meier, C. L., Herman, L. I., Reisner, S. L., Pardo, S. T., Sharp, C., & Babcock, J. C. (2015). Testosterone treatment and MMPI-2 improvement in transgender men: A prospective controlled study. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83 , 143-156.

Objective: Most transgender men desire to receive testosterone treatment in order to masculinize their bodies. In this study, we aimed to investigate the short-term effects of testosterone treatment on psychological functioning in transgender men. This is the 1st controlled prospective follow-up study to examine such effects. Method: We examined a sample of transgender men (n = 48) and nontransgender male (n = 53) and female (n = 62) matched controls (mean age = 26.6 years; 74% White). We asked participants to complete the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (2nd ed., or MMPI–2; Butcher, Graham, Tellegen, Dahlstrom, & Kaemmer, 2001) to assess psychological functioning at baseline and at the acute posttreatment follow-up (3 months after testosterone initiation). Regression models tested (a) Gender × Time interaction effects comparing divergent mean response profiles across measurements by gender identity; (b) changes in psychological functioning scores for acute postintervention measurements, adjusting for baseline measures, comparing transgender men with their matched nontransgender male and female controls and adjusting for baseline scores; and (c) changes in meeting clinical psychopathological thresholds. Results: Statistically significant changes in MMPI–2 scale scores were found at 3-month follow-up after initiating testosterone treatment relative to baseline for transgender men compared with female controls (female template): reductions in Hypochondria (p < .05), Depression (p < .05), Hysteria (p < .05), and Paranoia (p < .01); and increases in Masculinity–Femininity scores (p < .01). Gender × Time interaction effects were found for Hysteria (p < .05) and Paranoia (p < .01) relative to female controls (female template) and for Hypochondria (p < .05), Depression (p < .01), Hysteria (p < .01), Psychopathic Deviate (p < .05), Paranoia (p < .01), Psychasthenia (p < .01), and Schizophrenia (p < .01) compared with male controls (male template). In addition, the proportion of transgender men presenting with co-occurring psychopathology significantly decreased from baseline compared with 3-month follow-up relative to controls (p < .05). Conclusions: Findings suggest that testosterone treatment resulted in increased levels of psychological functioning on multiple domains in transgender men relative to nontransgender controls. These findings differed in comparisons of transgender men with female controls using the female template and with male controls using the male template. No iatrogenic effects of testosterone were found. These findings suggest a direct positive effect of 3 months of testosterone treatment on psychological functioning in transgender men.

Kraemer et al., 2008

Kraemer, B., Delsignore, A., Schnyder, U., & Hepp, U. (2008). Body image and transsexualism. Psychopathology , 41 (2), 96-100.

Background: To achieve a detailed view of the body image of transsexual patients, an assessment of perception, attitudes and experiences about one’s own body is necessary. To date, research on the body image of transsexual patients has mostly covered body dissatisfaction with respect to body perception. Sampling and Methods: We investigated 23 preoperative (16 male-to-female and 7 female-to-male transsexual patients) and 22 postoperative (14 male-to-female and 8 female-to-male) transsexual patients using a validated psychological measure for body image variables. Results: We found that preoperative transsexual patients were insecure and felt unattractive because of concerns about their body image. However, postoperative transsexual patients scored high on attractiveness and self-confidence. Furthermore, postoperative transsexual patients showed low scores for insecurity and concerns about their body. Conclusions: Our results indicate an improvement of body image concerns for transsexual patients following standards of care for gender identity disorder. Follow-up studies are recommended to confirm the assumed positive outcome of standards of care on body image.

Landen et al., 1998

Landén, M., Wålinder, J., Hambert, G., & Lundström, B. (1998). Factors predictive of regret in sex reassignment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica , 97 (4), 284-289.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the features and calculate the frequency of sex-reassigned subjects who had applied for reversal to their biological sex, and to compare these with non-regretful subjects. An inception cohort was retrospectively identified consisting of all subjects with gender identity disorder who were approved for sex reassignment in Sweden during the period 1972-1992. The period of time that elapsed between the application and this evaluation ranged from 4 to 24 years. The total cohort consisted of 218 subjects. The results showed that 3.8% of the patients who were sex reassigned during 1972-1992 regretted the measures taken. The cohort was subdivided according to the presence or absence of regret of sex reassignment, and the two groups were compared. The results of logistic regression analysis indicated that two factors predicted regret of sex reassignment, namely lack of support from the patient’s family, and the patient belonging to the non-core group of transsexuals. In conclusion, the results show that the outcome of sex reassignment has improved over the years. However, the identified risk factors indicate the need for substantial efforts to support the families and close friends of candidates for sex reassignment.

Lawrence, 2003

Lawrence, A. A. (2003). Factors associated with satisfaction or regret following male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 32 (4), 299-315.

This study examined factors associated with satisfaction or regret following sex reassignment surgery (SRS) in 232 male-to-female transsexuals operated on between 1994 and 2000 by one surgeon using a consistent technique. Participants, all of whom were at least 1-year postoperative, completed a written questionnaire concerning their experiences and attitudes. Participants reported overwhelmingly that they were happy with their SRS results and that SRS had greatly improved the quality of their lives. None reported outright regret and only a few expressed even occasional regret. Dissatisfaction was most strongly associated with unsatisfactory physical and functional results of surgery. Most indicators of transsexual typology, such as age at surgery, previous marriage or parenthood, and sexual orientation, were not significantly associated with subjective outcomes. Compliance with minimum eligibility requirements for SRS specified by the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association was not associated with more favorable subjective outcomes. The physical results of SRS may be more important than preoperative factors such as transsexual typology or compliance with established treatment regimens in predicting postoperative satisfaction or regret.

Lawrence, 2006

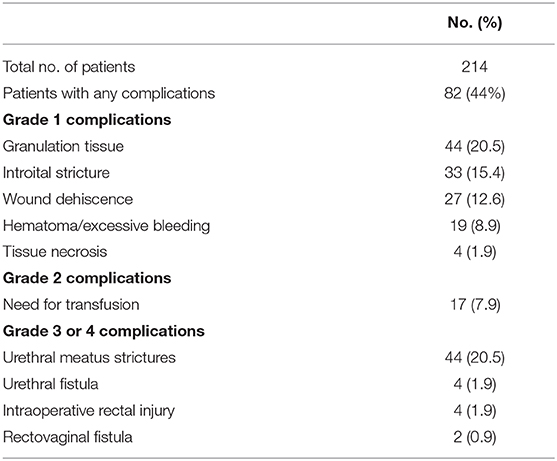

Lawrence, A. A. (2006). Patient-reported complications and functional outcomes of male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 35 (6), 717-727.

This study examined preoperative preparations, complications, and physical and functional outcomes of male-to-female sex reassignment surgery (SRS), based on reports by 232 patients, all of whom underwent penile-inversion vaginoplasty and sensate clitoroplasty, performed by one surgeon using a consistent technique. Nearly all patients discontinued hormone therapy before SRS and most reported that doing so created no difficulties. Preoperative electrolysis to remove genital hair, undergone by most patients, was not associated with less serious vaginal hair problems. No patients reported rectal-vaginal fistula or deep-vein thrombosis and reports of other significant surgical complications were uncommon. One third of patients, however, reported urinary stream problems. No single complication was significantly associated with regretting SRS. Satisfaction with most physical and functional outcomes of SRS was high; participants were least satisfied with vaginal lubrication, vaginal touch sensation, and vaginal erotic sensation. Frequency of achieving orgasm after SRS was not significantly associated with most general measures of satisfaction. Later years of surgery, reflecting greater surgeon experience, were not associated with lower prevalence rates for most complications or with better ratings for most physical and functional outcomes of SRS.

Lobato et al., 2006

Lobato M. I., Koff, W. J., Manenti, C., da Fonseca Seger, D., Salvador, J., et al. (2006). Follow-up of sex reassignment surgery in transsexuals: a Brazilian cohort. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35(6) , 711–715.

This study examined the impact of sex reassignment surgery on the satisfaction with sexual experience, partnerships, and relationship with family members in a cohort of Brazilian transsexual patients. A group of 19 patients who received sex reassignment between 2000 and 2004 (18 male- to-female, 1 female-to-male) after a two-year evaluation by a multidisciplinary team, and who agreed to participate in the study, completed a written questionnaire. Mean age at entry into the program was 31.21 ± 8.57 years and mean schooling was 9.2 ± 1.4 years. None of the patients reported regret for having undergone the surgery. Sexual experience was considered to have improved by 83.3% of the patients, and became more frequent for 64.7% of the patients. For 83.3% of the patients, sex was considered to be pleasurable with the neovagina/neopenis. In addition, 64.7% reported that initiating and maintaining a relationship had become easier. The number of patients with a partner increased from 52.6% to 73.7%. Family relationships improved in 26.3% of the cases, whereas 73.7% of the patients did not report a difference. None of the patients reported worse relationships

Manieri et al., 2014

Manieri, C., Castellano, E., Crespi, C., Di Bisceglie, C., Dell’Aquila, C., et al. (2014). Medical treatment of subjects with gender identity disorder: The experience in an Italian public health center. International Journal Of Transgenderism , 15 (2), 53-65.

Hormonal treatment is the main element during the transition program for transpeople. The aim of this paper is to describe the care and treatment of subjects, highlighting both the endocrine-metabolic effects of the hormonal therapy and the quality of life during the first year of cross-sex therapy in an Italian gender team. We studied 83 subjects (56 male-to-female [MtF], 27 female-to-male [FtM]) with hematological and hormonal evaluations every 3 months during the first year of hormonal therapy. MtF persons were treated with 17βestradiol and antiandrogens (cyproterone acetate, spironolactone, dutasteride); FtM persons were treated with transdermal or intramuscular testosterone. The WHO Quality of Life questionnaire was administered at the beginning and 1 year later. Hormonal changes paralleled phenotype modifications with wide variability. Most of both MtF and FtM subjects reported a statistically significant improvement in body image (p < 0.05). In particular, MtF subjects reported a statistically significant improvement in the quality of their sexual life and in the general quality of life (p < 0.05) 1 year after treatment initiation. Cross-sex therapy seems to be free of major risks in healthy subjects under clinical supervision during the first year. Selected subjects show an optimal adaptation to hormone-induced neuropsychological modifications and satisfaction regarding general and sexual life.

Megeri and Khoosal, 2007

Megeri, D., & Khoosal, D. (2007). Anxiety and depression in males experiencing gender dysphoria. Sexual & Relationship Therapy , 22 (1), 77-81.

Objective: The aim of the study was to compare anxiety and depression scores for the first 40 male to female people experiencing gender dysphoria attending the Leicester Gender Identity Clinic using the same sample as control pre and post gender realignment surgery. Hypothesis: There is an improvement in the scores of anxiety and depression following gender realignment surgery among people with gender dysphoria (male to female – transwomen). Results: There was no significant change in anxiety and depression scores in people with gender dysphoria (male to female) pre- and post-operatively.

Nelson, Whallett, & Mcgregor, 2009

Nelson, L., Whallett, E., & McGregor, J. (2009). Transgender patient satisfaction following reduction mammaplasty. Journal of Plastic, Reconstructive & Aesthetic Surgery , 62 (3), 331-334.

Aim: To evaluate the outcome of reduction mammaplasty in female-to-male transgender patients. Method: A 5-year retrospective review was conducted on all female-to-male transgender patients who underwent reduction mammaplasty. A postal questionnaire was devised to assess patient satisfaction, surgical outcome and psychological morbidity. Results: Seventeen patients were identified. The senior author performed bilateral reduction mammaplasties and free nipple grafts in 16 patients and one patient had a Benelli technique reduction. Complications included two haematomas, one wound infection, one wound dehiscence and three patients had hypertrophic scars. Secondary surgery was performed in seven patients and included scar revision, nipple reduction/realignment, dog-ear correction and nipple tattooing. The mean follow-up period after surgery was 10 months (range 2–23 months). Twelve postal questionnaires were completed (response rate 70%). All respondents expressed satisfaction with their result and no regret. Seven patients had nipple sensation and nine patients were satisfied with nipple position. All patients thought their scars were reasonable and felt that surgery had improved their self-confidence and social interactions. Conclusion: Reduction mammaplasty for female-to-male gender reassignment is associated with high patient satisfaction and a positive impact on the lives of these patients.

Newfield et al., 2006

Newfield, E., Hart, S., Dibble, S., & Kohler, L. (2006). Female-to-male transgender quality of life. Quality of Life Research , 15 (9), 1447-1457.

Objectives: We evaluated health-related quality of life in female-to-male (FTM) transgender individuals, using the Short-Form 36-Question Health Survey version 2 (SF-36v2). Methods: Using email, Internet bulletin boards, and postcards, we recruited individuals to an Internet site ( http://www.transurvey.org ), which contained a demographic survey and the SF36v2. We enrolled 446 FTM transgender and FTM transsexual participants, of which 384 were from the US. Results: Analysis of quality of life health concepts demonstrated statistically significant (p<0.0\) diminished quality of life among the FTM transgender participants as compared to the US male and female population, particularly in regard to mental health. FTM transgender participants who received testosterone (67%) reported statistically significant higher quality of life scores (/?<0.01) than those who had not received hormone therapy. Conclusions: FTM transgender participants reported significantly reduced mental health-related quality of life and

Padula, Heru, & Campbell, 2016

Padula, W. V., Heru, S. & Campbell, J. D. (2016). Societal implications of health insurance coverage for medically necessary services in the U.S. transgender population: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine , 31 ( 4), 394-401.

Background: Recently, the Massachusetts Group Insurance Commission (GIC) prioritized research on the implications of a clause expressly prohibiting the denial of health insurance coverage for transgender-related services. These medically necessary services include primary and preventive care as well as transitional therapy. Objective: To analyze the cost-effectiveness of insurance coverage for medically necessary transgender-related services. Design: Markov model with 5- and 10-year time horizons from a U.S. societal perspective, discounted at 3 % (USD 2013). Data on outcomes were abstracted from the 2011 National Transgender Discrimination Survey (NTDS). Patients: U.S. transgender population starting before transitional therapy. Interventions: No health benefits compared to health insurance coverage for medically necessary services. This coverage can lead to hormone replacement therapy, sex reassignment surgery, or both. Main Measures: Cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) for successful transition or negative outcomes (e.g. HIV, depression, suicidality, drug abuse, mortality) dependent on insurance coverage or no health benefit at a willingness-to-pay threshold of $100,000/QALY. Budget impact interpreted as the U.S. per-member-per-month cost. Key Results: Compared to no health benefits for transgender patients ($23,619; 6.49 QALYs), insurance coverage for medically necessary services came at a greater cost and effectiveness ($31,816; 7.37 QALYs), with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of $9314/QALY. The budget impact of this coverage is approximately $0.016 per member per month. Although the cost for transitions is $10,000–22,000 and the cost of provider coverage is $2175/year, these additional expenses hold good value for reducing the risk of negative endpoints —HIV, depression, suicidality, and drug abuse. Results were robust to uncertainty. The probabilistic sensitivity analysis showed that provider coverage was cost-effective in 85 % of simulations. Conclusions: Health insurance coverage for the U.S. transgender population is affordable and cost-effective, and has a low budget impact on U.S. society. Organizations such as the GIC should consider these results when examining policies regarding coverage exclusions.

Parola et al., 2010

Parola, N., Bonierbale, M., Lemaire, A., Aghababian, V., Michel, A., & Lançon, C. (2010). Study of quality of life for transsexuals after hormonal and surgical reassignment. Sexologies , 19 (1), 24-28.

Aim: The main objective of this work is to provide a more detailed assessment of the impact of surgical reassignment on the most important aspects of daily life for these patients. Our secondary objective was to establish the influence of various factors likely to have an impact on the quality of life (QoL), such as biological gender and the subject’s personality. Methods: A personality study was conducted using Eysenck Personality Inventory (EPI) so as to analyze two aspects of the personality (extraversion and neuroticism). Thirty-eight subjects who had undergone hormonal surgical reassignment were included in the study. Results: The results show that gender reassignment surgery improves the QoL for transsexuals in several different important areas: most are satisfied of their sexual reassignment (28/30), their social (21/30) and sexual QoL (25/30) are improved. However, there are differences between male-to-female (MtF) and female-to-male (FtM) transsexuals in terms of QoL: FtM have a better social, professional, friendly lifestyles than MtF. Finally, the results of this study did not evidence any influence by certain aspects of the personality, such as extraversion and neuroticism, on the QoL for reassigned subjects.

Pfäfflin, 1993

Pfäfflin, F. (1993). Regrets after sex reassignment surgery. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality , 5 (4), 69-85.

Using data draw from the follow-up literature covering the last 30 years, and the author’s clinical data on 295 men and women after SRS, an estimation of the number of patients who regretted the operations is made. Among female-to-male transsexuals after SRS, i.e., in men, no regrets were reported in the author’s sample, and in the literature they amount to less than 1%. Among male-to- female transsexuals after SRS, i.e., in women, regrets are reported in 1-1.5%. Poor differential diagnosis, failure to carry out the real-life- test, and poor surgical results seem to be the main reasons behind the regrets reported in the literature. According to three cases observed by the author in addition to personality traits the lack of proper care in treating the patients played a major role.

Pimenoff and Pfäfflin, 2011

Pimenoff, V., & Pfäfflin, F. (2011). Transsexualism: Treatment outcome of compliant and noncompliant patients. International Journal Of Transgenderism , 13 (1), 37-44.

The objective of the study was a follow-up of the treatment outcome of Finnish transsexuals who sought sex reassignment during the period 1970–2002 and a comparison of the results and duration of treatment of compliant and noncompliant patients. Fifteen male-to-female transsexuals and 17 female-to-male transsexuals who had undergone hormone and surgical treatment and legal sex reassignment in Finland completed a questionnaire on psychosocial data and on their experience with the different phases of clinical assessment and treatment. The changes in their vocational functioning and social and psychic adjustment were used as outcome indicators. The results and duration of the treatment of compliant and noncompliant patients were compared. The patients benefited significantly from treatment. The noncompliant patients achieved equally good results as the compliant ones, and did so in a shorter time. A good treatment outcome could be achieved even when the patient had told the assessing psychiatrist a falsified story of his life and sought hormone therapy, genital surgery, or legal sex reassignment on his own initiative without a recommendation from the psychiatrist. Based on these findings, it is recommended that the doctor-patient relationship be reconsidered and founded on frank cooperation.

Rakic et al., 1996

Rakic, Z., Starcevic, V., Maric, J., & Kelin, K. (1996). The outcome of sex reassignment surgery in Belgrade: 32 patients of both sexes. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 25 (5), 515-525.

Several aspects of the quality of life after sex reassignment surgery in 32 transsexuals of both sexes (22 men, 10 women) were examined. The Belgrade Team for Gender Identity Disorders designed a standardized questionnaire for this purpose. The follow-up period after operation was from 6 months to 4 years, and four aspects of the quality of life were examined: attitude towards the patients’ own body, relationships with other people, sexual activity, and occupational functioning. In most transsexuals, the quality of life was improved after surgery inasmuch as these four aspects are concerned. Only a few transsexuals were not satisfied with their life after surgery.

Rehman et al., 1999

Rehman, J., Lazer, S., Benet, A. E., Schaefer, L. C., & Melman, A. (1999). The reported sex and surgery satisfactions of 28 postoperative male-to-female transsexual patients. Archives of Sexual Behavior , 28 (1), 71-89.