The Philippines: Historical Overview

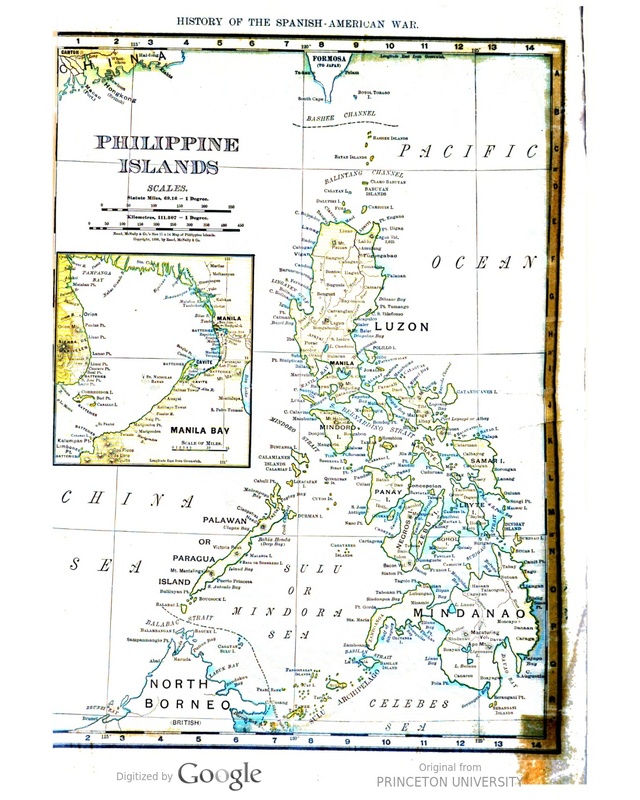

Map of the Philippines from 1898.

Source: History of the Spanish-American War , (New York: the Company, 1898), 2.

The Philippines is an archipelago made up of over 7,000 islands located in Southeast Asia. There are more than 175 ethnolinguistic groups, and over 100 dialects and languages spoken. One of the difficulties of writing a history of the Philippines is that prior to the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, the people that inhabited the archipelago did not see themselves as a unified political or cultural group. In fact, it was not until the late nineteenth century that a sense of a Philippine nation began to develop.

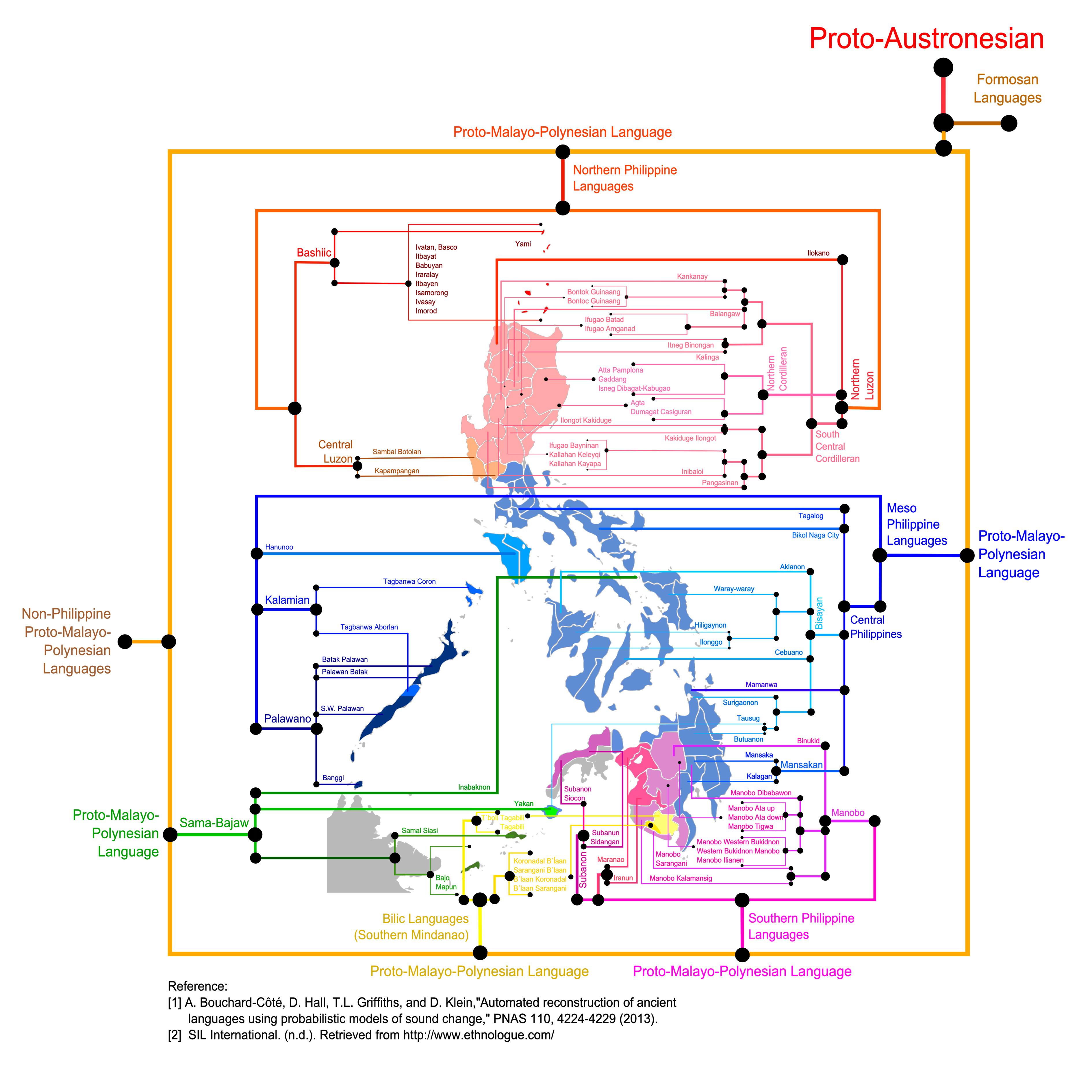

The first peoples to inhabit the Philippines migrated more than 4,000 years ago from what is today southern China. These peoples did not just populate the Philippines but dispersed throughout Southeast Asia. Historians and anthropologists have been able to trace their early migrations by examining linguistic patterns and have noted the Austronesian origin of most of the languages spoken in the precolonial Philippines and Southeast Asia. Indigenous languages spoken in Indonesia and Malaysia, for example, also share Austronesian roots.[1]

Early settlements of the Philippine archipelago occurred along rivers which kept populations somewhat isolated from one another. Rivers provided natural resources (water and protein via seafood) to sustain small communities. While these settlements were scattered along rivers, they did not develop a political center. Instead, early settlers saw themselves in relation to smaller communities and developed local alliances and allegiances. People were linked to one another through kinship, both biological and fictive, and followed a leader whom they called a datu. Datus emerged as protectors of the group. They used their skills in negotiation and warfare to demand tribute from merchants and maintain their clans. Eventually, these small communities ranging from 30 to 100 households became known as barangays, meaning “boat” in Tagalog, a Philippine language that originates in central Luzon.[2]

When Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the archipelago, specifically to the Visayas region in 1521, he encountered a large network of barangays connected to a broader maritime world in Southeast Asia. Precolonial communities were in contact with other ethnolinguistic groups across the archipelago and beyond through trade and religious exchange. Goods such as rice, spices, aromatics, and other forest products attracted foreign merchants as far as India and China and richly rewarded the datus.[3] In terms of religion, historical evidence shows that precolonial Philippine peoples practiced “animism,” or beliefs and practices that held spirits as immanent to the surrounding world. These religious practices developed through trade networks, which also paved the way for the spread of Islam. Well before the arrival of Christianity, Islam reached the archipelago in the fourteenth century.[4]

It was the Spanish expedition led by Magellan in 1521 that laid the foundations for imagining a Spanish colony in the Philippines. Over the next 50 years, the Spanish crown sent more expeditions to the islands in search of spices and other goods. They named the islands after King Felipe II and aimed to have every datu follow him.[5] In 1565, Miguel Lopez de Legaspi arrived and brought the datu of Cebu in the Visayas to swear allegiance to the Spanish crown. His power over the region was insecure, however. Legaspi then gathered his followers and an army to travel to Maynilad (today known as Manila) to capture the port town from the son of a Luzon datu.[6]

Securing power over local settlements was a long and difficult process occurring over the next century that required both coaxing and coercion. By 1576, the Spanish created many settlements and the population of Spanish men in the region reached over 250.[7] One of their main challenges entailed bringing the indigenous people, who were still living in scattered settlements, under a centralized authority.

Bringing the indigenous population under Spanish rule took many decades of cajoling and relied on different tactics including developing alliances and enticing people through gifts and promises of salvation. Central to this process were the missionary friars who were a part of four main Catholic orders: Augustinians, Franciscans, Jesuits, and Dominicans. These missionary friars were sent to convert the native peoples to Christianity with the promise of Spain’s claim to the archipelago. According to historian John Phelan, “Christianization acted as a powerful instrument of societal control over the conquered people.”[8] Religious conversion through what was called conquista espiritual (“spiritual conquest”) became an important means to subjugate indigenous populations and also persuade them to relocate to political centers in order to facilitate a centralized Spanish rule.

The Spanish friars referred to the relocation process as reducción. As much as reducción was a process of religious conversion, it was also a militarized endeavor that involved violence when the so-called “indios” resisted.[9] A century after the Spanish Reconquista, wherein the Spanish reconquered the Iberian peninsula from Muslim rule, Spanish friars in the Philippines viewed their missionary duty as a continuation of an earlier struggle. The growing presence of Islam in the southern islands of the archipelago proved that the Spanish were destined to provide the natives salvation. They called converts to Islam “Moros” after the Moors they fought in Spain, which discursively connected their religious mission to their previous war of conquest.

Once areas were under Spanish control, the colonial government established an encomienda system that required the local population to pay tribute and perform labor for the colony.[10] A Spanish governor, who was also a military captain, effectively had the power to make decisions for the colony. This was due to the fact that the Philippine islands were so far away from the metropole. Yet, the governor’s power was still limited. The fact that he was also a military captain signals how, even after 300 years of rule, the Spanish never fully had control over the local population and therefore depended on military leadership [11]. Under the governor, provinces were established with a gobernadorcillo ruling each town. The gobernadorcillo enforced the law established by the colonial governor. Under the gobernadorcillo was the cabeza de barangay or the head of barangay who collected taxes locally. At times, the gobernadorcillo and the cabeza de barangay used force to obtain the funds they required from the local people. The Spanish colonial government depended on the collection of tribute to maintain their operations and control the Philippine population.

By the 1850s, the economic prosperity of the native-born population, especially of Chinese mestizos, began to develop into an elite class that rivaled the peninsulares, or the “pure blooded” Spanish in the archipelago (also sometimes known as criollos). By the 1870s, this new elite sent their sons to Manila and Europe for a liberal education and they became known as ilustrados, or “enlightened ones.”[12] Ilustrados began to question the authority of the Spanish friars and publicly critique the poor administration of the Philippine colony. It was this group of elite men that established the Propaganda Movement, based in Manila and Spain, calling for reforms centered on equality between Filipinos, mestizos, and the Spanish.[13] The writings of propagandists, especially that of Jose Rizal, the most famous of the group, inspired the Filipino masses. The views of the majority, however, diverged from those of the elites who advocated mainly for modest reform and representation. The politics of the elite was ultimately considered too moderate from the perspective of a majority who became inspired to revolt against Spain and fight for independence. In 1896, the Philippine revolution began as a radical fight for emancipation from Spanish colonialism and the right to Filipino self-governance.[14]

In 1898, a major event on the other side of the globe stymied the efforts of the Filipino revolutionaries. In April of 1898, the US sent the battleship USS Maine to Havana Harbor, Cuba, in support of Cuban revolutionaries. When the ship exploded killing over 200 Americans, the US government assumed the Spanish were responsible and used the event as a pretext for war. US president William McKinley declared war with Spain in August of 1898, and US troops were shipped to the remaining Spanish possessions, including the Philippines, just two days later.[15] The Filipino revolutionaries could not have predicted such a turn of events that would ultimately affect the outcome of their fight for an independent Philippines.

By the time the American military arrived in April of 1898, the Filipino revolutionaries had successfully gained control over all major cities in the archipelago except for the capital city of Manila. There, the Spanish were protected by a fortress constructed for military protection against outside invaders called Intramuros. Knowing that they were losing the war against the Filipinos, Spanish and US military officers pre-arranged a battle in Manila which excluded Filipino soldiers in order to stage the Spanish defeat. The Spanish orchestrated a mock battle in order to save face and lose the war to the Americans rather than to the Filipinos, whom they believed to be an inferior race.[16] The 1898 Treaty of Paris ended the Spanish-American War and officially transferred ownership of Spain’s remaining colonies to the US.[17]

Filipino revolutionaries continued their fight for independence against the US in the Philippine-American war. Over the next several decades of US rule, the US military and colonial officials attempted to establish control, pacify the local populations, and justify US imperialism in the Philippines. This is where our exhibit begins.

[1] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2005), 20.

[2] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 27.

[3] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 23.

[4] James Francis Warren, The Sulu Zone, 1768-1898: The Dynamics of External Trade, Slavery, and Ethnicity in the Transformation of a Southeast Asian Maritime State, (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1981).

[5] José S. Arcilla, An Introduction to Philippine History, (Manila: Ateneo Publications, 1971), 11.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 53.

[8] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines: Spanish Aims and Filipino Responses, 1565-1700, (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1959), 93.

[9] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines, 44-45.

[10] John Leddy Phelan, The Hispanization of the Philippines, 95.

[11] José S. Arcilla, An Introduction to Philippine History, 28.

[12] Edgar Wickberg, The Chinese in Philippine Life, 1850-1898, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1965).

[13] John N. Schumacher, The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creators of a Filipino Consciousness, the Makers of Revolution, (Manila: Solidaridad Pub. House, 1973).

[14] Patricio N. Abinales and Donna J. Amoroso, State and Society in the Philippines, 104.

[15] Paul Kramer, The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States, and the Philippines, (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 78.

[16] Paul Kramer, The Blood of Government, 90.

- AsianStudies.org

- Annual Conference

- EAA Articles

- 2025 Annual Conference March 13-16, 2025

- AAS Community Forum Log In and Participate

Education About Asia: Online Archives

A brief essay on my key issues book: the philippines: from earliest times to the present.

My AAS Key Issues in Asian Studies book— The Philippines: From Earliest Times to the Present —is intended to introduce readers to a nation originally named after a European prince. The people of the archipelago that now constitutes the Philippines had a long history before any European contact occurred. Since the latter part of the nineteenth century, Filipinos have experienced a wide range of encounters with the US. The Philippines was Asia’s first republic and then became a US colony after an American war of conquest and pacification, which some argue resulted in the deaths of 10 percent of the population. Almost a million Filipino soldiers and civilians, and approximately 23,000 American military, died in the war against Imperial Japanese forces.

There are at least two ideas that drive this book. The first is that the Philippines was not some isolated archipelago that was accidentally “discovered” by Ferdinand Magellan in 1521. Some residents of the Philippines had contact with “the outside world” long before European contact through trade with other Southeast Asian polities and Imperial China.

The second and more important theme is that vibrant cultures existed before outsiders arrived, and they have continued throughout the history of the Philippines, though perhaps not seen or simply ignored by historians and other scholars. The intrusion by the Spaniards might be seen to have changed almost everything, as did the American incursion, and to a lesser extent the Japanese occupation. This is not the case. But if one does not know what was there before, the focus may be upon the intruders—their religion, culture, economies, and the impact they had on the local population—rather than on Filipinos, the local inhabitants. While acknowledging the impact and influence of foreign occupations, I sought in the book to focus on Filipinos and to see them as not merely, or even primarily, reactive.

Beginning with the pre-Hispanic period, The Philippines: From Earliest Times to the Present seeks to present, briefly, the reality of an advanced indigenous culture certainly influenced but not erased by more than three centuries of Spanish occupation. The second half of the nineteenth century saw the emergence on two levels—peasants and elite—of organized resistance to that presence, culminating in what some call a revolution and finally a republic. But this development was cut short by the Americans. When a commonwealth was put in place during the fourth decade of American rule, this was interrupted by World War II and the Japanese occupation. After World War II, the Philippines once again became an independent republic with the growing pains of a newly evolving democracy and its share of ups and down, including the Marcos dictatorship.

The Philippines has emerged in the twenty-first century with a robust and expanding economy, and as an important member of ASEAN. And it has its issues. On November 7, 2013, the most powerful Philippine typhoon on record hit the central part of the archipelago, resulting in more than 6,000 deaths. President Rodrigo Duterte, elected in 2016, has caught the eye of human rights advocates as he has dealt harshly with a drug problem that is far more significant than most realized. Then there is the ongoing conflict with China over islands in the South China Sea. The Philippines has been and will continue to be in the news.

The Philippines: From Earliest Times to the Present depicts Filipinos as not passive or merely the recipients of foreign influences. Contrary to the title of Stanley Karnow’s 1989 book, In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines, the Philippines is not made in anyone’s, including America’s, image. Teachers and students should find this book helpful, not only in dealing with the history of the Philippines but also in recognizing that often the histories of developing countries fail to seriously take into account the local population—their culture, their actions, their vision of the world. The Philippines is perhaps best known today in the West as a place with beautiful beaches and as a wonderful place to vacation. This book will show it to be much more than that.

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Latest News

- Join or Renew

- Education About Asia

- Education About Asia Articles

- Asia Shorts Book Series

- Asia Past & Present

- Key Issues in Asian Studies

- Journal of Asian Studies

- The Bibliography of Asian Studies

- AAS-Gale Fellowship

- Council Grants

- Book Prizes

- Graduate Student Paper Prizes

- Distinguished Contributions to Asian Studies Award

- First Book Subvention Program

- External Grants & Fellowships

- AAS Career Center

- Asian Studies Programs & Centers

- Study Abroad Programs

- Language Database

- Conferences & Events

- #AsiaNow Blog

Local Histories

Tim's History of British Towns, Cities and So Much More

A Brief History of The Philippines

By Tim Lambert

The Early Philippines

The Philippines is named after King Philip II of Spain (1556-1598) and it was a Spanish colony for over 300 years. Today the Philippines is an archipelago of 7,000 islands. However, it is believed that during the last ice age they were joined to mainland Asia by a land bridge, enabling human beings to walk from there.

The first people in the Philippines were hunter-gatherers. However, between 3,000 BC and 2,000 BC, people learned to farm. They grew rice and domesticated animals. From the 10th AD century Filipinos traded with China and by the 12th Century AD Arab merchants reached the Philippines and they introduced Islam.

Then in 1521, Ferdinand Magellan sailed across the Pacific. He landed in the Philippines and claimed them for Spain. Magellan baptized a chief called Humabon and hoped to make him a puppet ruler on behalf of the Spanish crown. Magellan demanded that other chiefs submit to Humabon but one chief named Lapu Lapu refused. Magellan led a force to crush him. However, the Spanish soldiers were scattered and Magellan was killed.

The Spaniards did not gain a foothold in the Philippines until 1565 when Miguel Lopez de Legazpi led an expedition, which built a fort in Cebu. Later, in 1571 the Spaniards landed in Luzon. Here they built the city of Intramuros (later called Manila), which became the capital of the Philippines. Spanish conquistadors marched inland and conquered Luzon. They created a feudal system. Spaniards owned vast estates worked by Filipinos.

Along with conquistadors went friars who converted the Filipinos to Catholicism. The friars also built schools and universities.

The Spanish colony in the Philippines brought prosperity – for the upper class anyway! Each year the Chinese exported goods such as silk, porcelain, and lacquer to the Philippines. From there they were re-exported to Mexico.

The years passed uneventfully in the Philippines until in 1762 the British captured Manila. They held it for two years but they handed it back in 1764 under the terms of the Treaty of Paris, signed in 1763.

The Philippines in the 19th Century

In 1872 there was a rebellion in Cavite but it was quickly crushed. However nationalist feelings continued to grow helped by a writer named Jose Rizal (1861-1896). He wrote two novels Noli Me Tangere (Touch Me Not) and El Filibusterismo (The Filibusterer) which stoked the fires of nationalism.

In 1892 Jose Rizal founded a movement called Liga Filipina, which called for reform rather than revolution. As a result, Rizal was arrested and exiled to Dapitan on Mindanao.

Meanwhile, Andres Bonifacio formed a more extreme organization called the Katipunan. In August 1896 they began a revolution. Jose Rizal was accused of supporting the revolution, although he did not and he was executed on 30 December 1896. Yet his execution merely inflamed Filipino opinion and the revolution grew.

Then in 1898 came the war between the USA and Spain. On 30 April 1898, the Americans defeated the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. Meanwhile, Filipino revolutionaries surrounded Manila. Their leader, Emilio Aguinaldo declared the Philippines independent on 12 June. However, as part of the peace treaty, Spain ceded the Philippines to the USA. The Americans planned to take over.

The war between American forces in Manila and the Filipinos began on 4 February 1899. The Filipino-American War lasted until 1902 when Aguinaldo was captured.

The Philippines in the 20th Century

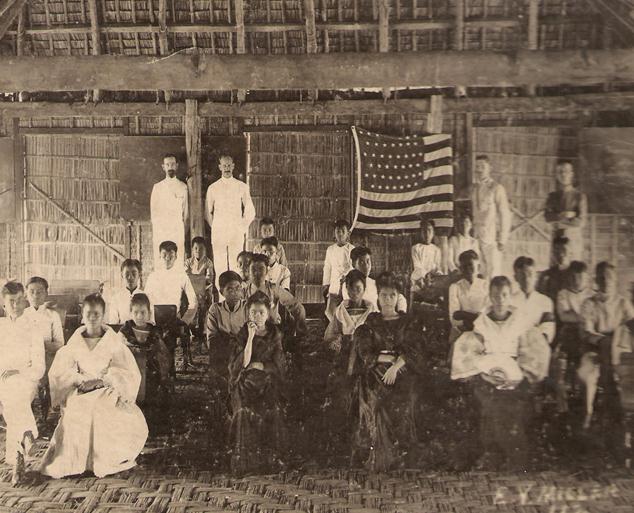

American rule in the Philippines was paternalistic. They called their policy ‘Benevolent Assimilation. They wanted to ‘Americanize’ the Filipinos but they never quite succeeded. However, they did do some good. Many American teachers were sent to the Philippines in a ship called the Thomas and they did increase literacy.

In 1935 the Philippines were made a commonwealth and were semi-independent. Manuel Quezon became president. The USA promised that the Philippines would become completely independent in 1945.

However, in December 1941, Japan attacked the US fleet at Pearl Harbor. On 10 December 1941 Japanese troops invaded the Philippines. They captured Manila on 2 January 1941. By 6 May 1942, all of the Philippines were in Japanese hands.

However American troops returned to the Philippines in October 1944. They recaptured Manila in February 1945.

The Philippines became independent on 4 July 1946. Manuel Roxas was the first president of the newly independent nation. n Ferdinand Marcos (1917-1989) was elected president in 1965. He was re-elected in 1969. However, the Philippines was dogged by poverty and inequality. In the 1960s a land reform program began. However many peasants were frustrated by its slow progress and a Communist insurgency began in the countryside.

On 21 September 1972 Marcos declared martial law. He imposed a curfew, suspended Congress, and arrested opposition leaders.

The Marcos dictatorship was exceedingly corrupt and Marcos and his cronies enriched themselves.

Then, in 1980 opposition leader Benigno Aquino went into exile in the USA. When he returned on 21 August 1983 he was shot. Aquino became a martyr and Filipinos were enraged by his murder.

In February 1986 Marcos called an election. The opposition united behind Cory Aquino the widow of Benigno. Marcos claimed victory (a clear case of electoral fraud). Cory Aquino also claimed victory and ordinary people took to the streets to show their support for her. The followers of Marcos deserted him and he bowed to the inevitable and went into exile.

Things did not go smoothly for Corazon Aquino. (She survived 7 coup attempts). Furthermore, the American bases in the Philippines (Subic Bay Naval Base and Clark Air Base) were unpopular with many Filipinos who felt they should go. In 1992 Mount Pinatubo erupted and covered Clark in volcanic ash forcing the Americans to leave. They left Subic Bay in 1993.

In 1992 Fidel Ramos became president. He improved the infrastructure in the Philippines including the electricity supply. Industry was privatized and the economy began to grow more rapidly.

However, at the end of the 1990s, the Philippine economy entered a crisis. Meanwhile, in 1998 Joseph Estrada, known as Erap became president. Estrada was accused of corruption and he was impeached in November 2000. Estrada was not convicted. Nevertheless, people demonstrated against him and the military withdrew its support. Estrada was forced to leave office and Vice-president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo replaced him. She was re-elected in 2004.

The Philippines in the 21st Century

Today the Philippines is still poor but things are changing rapidly. After 2010 the Philippine economy grew at about 6% a year. It is rapidly industrializing and growing more propserous. Meanwhile, In 2016 the Philippines launched its first satellite. It was called Diwata-1. In 2024 the population of the Philippines was 114 million.

Last Revised 2024

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

Essay on Philippines Culture

Students are often asked to write an essay on Philippines Culture in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Philippines Culture

The land and people.

The Philippines is a Southeast Asian country made up of over 7,000 islands. It’s home to more than 100 million people. Filipinos are known for their friendly nature and warm hospitality. They have a mix of different ethnic groups, each with their own unique customs and traditions.

Language and Communication

Filipinos speak Filipino and English as their official languages. Filipino is mainly based on Tagalog, a local language. They also use many other regional languages. Filipinos are known for their ‘bayanihan’ spirit, which means helping each other in times of need.

Food and Cuisine

Filipino food is a blend of Spanish, Chinese, and native influences. Rice is a staple food. Their famous dish is ‘Adobo’, a meal made with meat, vinegar, and soy sauce. ‘Lechon’, a whole roasted pig, is a special festive dish.

Arts and Music

The Philippines has a rich history of arts and music. Traditional dances like ‘Tinikling’ and ‘Singkil’ tell stories of everyday life and folklore. Filipinos love to sing and are known for their karaoke sessions.

Festivals and Celebrations

Festivals, known as ‘fiestas’, are important in Filipino culture. These include the ‘Ati-Atihan’, ‘Sinulog’, and ‘Pahiyas’. These festivals are filled with colorful parades, dances, and feasts. They show the Filipinos’ love for fun and celebration.

Religion and Beliefs

Most Filipinos are Christians, with a majority being Catholic. They celebrate religious holidays like Christmas and Easter with great enthusiasm. Filipinos also believe in spirits and mythical creatures, which are part of their folk tales.

250 Words Essay on Philippines Culture

Introduction to philippines culture.

The Philippines is a country in Southeast Asia known for its rich and diverse culture. This culture is a mix of native and foreign influences from its history, including Spanish, American, and Asian cultures.

Language and Literature

Filipino and English are the official languages of the Philippines. Filipino, based on Tagalog, is the national language. The Philippines is also home to over 170 other languages. Literature is a vital part of their culture, with famous works like the epic “Florante at Laura” by Francisco Balagtas.

Filipinos are known for their love of arts and music. Traditional arts include weaving, pottery, and carving. Music is often used in festivals and celebrations. The “Kundiman” is a popular type of love song.

Festivals, or “fiestas,” are important in Filipino culture. These events celebrate history, religion, and local customs. The “Sinulog Festival” in Cebu and the “Ati-Atihan Festival” in Aklan are famous examples.

Filipino food is a blend of different culinary styles. It includes dishes like “Adobo,” a marinated meat dish, and “Sinigang,” a sour soup. Rice is a staple food and is served with almost every meal.

In conclusion, the culture of the Philippines is a colorful mix of various influences. It reflects the country’s history, diversity, and the warm spirit of its people. It is a culture that values community, creativity, and a love for life.

500 Words Essay on Philippines Culture

The Philippines is a Southeast Asian country known for its rich culture and traditions. Its culture is a blend of indigenous customs and foreign influences from Spain, China, America, and other Asian countries. This makes it a unique and vibrant place.

Filipinos love to celebrate. Festivals, known as ‘fiestas’, are a big part of their culture. These events are colorful, lively, and filled with music, dance, and food. Each region has its own special fiesta. For example, the ‘Sinulog’ festival in Cebu celebrates the Filipino’s conversion to Christianity.

Food in the Philippines

Filipino food is a mix of flavors from different cultures. It includes rice, noodles, meat, and plenty of fruits and vegetables. One popular dish is ‘Adobo’, made from vinegar, soy sauce, garlic, and meat. ‘Lechon’, a whole roasted pig, is often served at big celebrations. Filipinos also love sweet treats like ‘Halo-Halo’, a dessert made with crushed ice, sweet fruits, and beans.

Arts and Crafts

Filipinos are known for their creativity. They make beautiful handicrafts like woven baskets, mats, and furniture from bamboo and rattan. Filipinos also have a rich tradition of dance and music. Folk dances like ‘Tinikling’ and ‘Singkil’ tell stories about daily life and history.

The Philippines has more than 170 languages, but Filipino and English are the official languages. Filipinos are known for being friendly and hospitable. They use a lot of body language and smiles when they communicate. ‘Po’ and ‘Opo’ are respectful words often used when speaking to elders.

Family and Social Structure

Family is very important in Filipino culture. Families often live together in large groups, including grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. Respect for elders is a key value. Filipinos also have a strong sense of community. They often help each other in times of need, a practice known as ‘Bayanihan’.

Most Filipinos are Christian, with a large number being Catholic. They have a deep faith and often attend church. Many celebrations and festivals are based on religious events. Filipinos also believe in spirits and supernatural beings, which are part of folk beliefs.

The culture of the Philippines is a beautiful mix of traditions, beliefs, and influences from around the world. It is a culture that values family, community, faith, and celebration. Whether it’s their tasty food, vibrant festivals, or warm hospitality, the Filipino culture is truly unique and captivating.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Philippines Crimes

- Essay on Philippines A Century Hence

- Essay on Philippines

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

History of the Philippines

- Most Cited Papers

- Most Downloaded Papers

- Newest Papers

- Save to Library

- Last »

- Post-Althusserian Theory Follow Following

- Classical Tibetan Language Follow Following

- Eastern Philosophy and Religion Follow Following

- Asian Art Follow Following

- Medical Malpractice Law Follow Following

- Privacy and data protection Follow Following

- Criminal Psychology Follow Following

- Criminal profiling Follow Following

- Tibetan Studies Follow Following

- Rehabilitating Offenders Follow Following

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- Academia.edu Publishing

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Renee Karunungan

A History of the Philippines’ official languages

This was part of my essay for a class on Language Policy and Planning. The essay was marked with a distinction. I’m publishing a part of the essay for Buwan ng Wika.

The Department of Education now has 17 designated languages that qualify for mother-language based education. The current Philippine constitution (1987) states that the national language is Filipino and as it evolves, “shall be further developed and enriched on the basis of existing Philippine and other languages.” Further, the Philippine constitution (1987) has mandated the Government to “take steps to initiate and sustain the use of Filipino as a medium of official communication and as language of instruction in the educational system.”

However, this current policy on language has changed over the century, largely due to the Spanish, American, and Japanese colonisation, the liberation, and changes in the constitution post-dictatorship. There also remains to be contentions on whether Filipino, based on the Tagalog language, should be the national language of the Philippines. These contentions come from the non-Tagalog speaking region that have called the current language policy as “Tagalog imperialism.”

Given the rich history of the country and controversies regarding its language planning and policy throughout the century, this essay aims to explore the history of language policy and planning in the Philippines and the impacts it has had on its people, especially the non-Tagalog/Filipino speaking population. Secondary research and analysis will be used as a method of research.

History of LPP in the Philippines

The Philippines’ national language is Filipino. As mentioned earlier, de jure, it is a language that will be enriched from other languages in the Philippines. De facto , it is structurally based on Tagalog, the language of Manila and the CALABARZON (Cavite, Laguna, Batangas, Quezon) region (Gonzalez, 2006).

SPANISH COLONISATION

What was the language policy and planning like during the Spanish colonisation? According to Rodriguez (2013), the Spanish Crown issued several contradictory laws on language: missionaries were asked to learn the vernacular but were then required to teach Spanish. The friars continued to learn the local languages for evangelisation which turned out to be a success (Gonzalez, 2006). Thus, teaching Spanish teaching remained limited for the elites and wealthy Filipinos ready to conform to Spanish colonial agendas (Martin, 1999).

This was a way for the Spanish to control the country, and as Mahboob and Cruz (2013) suggest, a means to divide the rich and the poor. Arguably, this can also be the reason why the ilustrados (Filipinos educated in Spain) supported Philippine independence. Gonzalez (2006) writes,

In spite of repeated language instructions From the Crown on teaching the natives the Spanish language, there was only a little compliance. Instead the friars using common sense, kept employing the local languages, so much that in the period of intense nationalism in the nineteenth century, the failure of the Spanish friars to teach Spanish was used by some of the ilustrados (Filipinos educated in Spain) as a reason to accuse the friars of deliberately keeping Spanish away from the natives so as to prevent them from advancing themselves. Gonzales, 2006

AMERICAN COLONISATION

Shortly after the independence from Spain, the Philippines came under the American rule from 1898-1946. In the beginning Filipinos saw Americans as allies against Spain. The Americans saw the perfect opportunity for colonisation that Spain did not: education. While the Spanish eventually established schools through the Royal Decree of 1863, these were literacy schools teaching reading and writing in Spanish, religious studies, and numeracy not leading to any degrees (Gonzalez, 2006). Martin (1999) notes that the Americans, on the other hand, saw education as a powerful weapon and in the Philippines they found subjects receptive to the opportunities given by the English language. Gonzalez (1980, p.27-28) writes, “the positive attitude of Filipinos towards Americans; and the incentives given to Filipinos to learn English in terms of career opportunities, government service, and politics.”

American policy allowed for compulsory education for all Filipinos in English but was hostile to local languages. Although President McKinley ordered the use of English as well as mother tongue languages in education, the Americans found Philippine languages too many and too difficult to learn thus creating a monolingual system in English (Gonzalez, 2006). Manhit (1980) notes that during this time, students who used their mother tongue while in school premises were imposed with penalties. Media of instruction were in English, teachers were trained to teach English, and instructional materials were all in English. Local languages were used as “auxiliary languages to teach character education, good manners, and right conduct” (Martin, 1999, p.133). Ricento (2000 p. 198) argues that LPP during American colonisation led to a “stable digglosia” where English became the language of higher education, socioeconomic, and political opportunities still visible today.

Constantino (2002, p. 181) writes about how the acceptance of the English language eventually allowed Filipinos to embrace colonialism:

The first and perhaps the masterstroke in the plan to use education as an instrument of colonial policy was the decision to use English as the medium of instruction. English became the wedge that separate Filipinos from their past and later was to separate educated Filipinos from the masses of their countrymen… With American textbooks, Filipinos started learning not only a new language but also a new way of life, alien to their traditions and yet a caricature of their model. This was the beginning of their education. At the same time, it was the beginning of their miseducation, for they learned no longer as Filipinos but as colonials. Constantino, 2002

INDEPENDENCE

With the Commonwealth constitution being drafted, then Camarines Norte representative Wenceslao Vinzons proposed to include an article on the adoption of a national language. Article XIII section 3 of the 1935 Commonwealth Constitution directed the National Assembly to “take steps toward the development and adoption of a common national language based on one of the existing native languages.” In 1936, the Institute of National Language (INL) was founded to study existing languages and select one of them as the basis of the national language. In 1937, the INL recommended Tagalog as the basis of the national language because it was found to be widely spoken and was accepted by Filipinos and it had a large literary tradition. By 1939, it was officially proclaimed and ordered to be disseminated in schools and by 1940 was taught as a subject in high schools across the country.

There was resistance to Tagalog , especially among speakers of Cebuano (Baumgartner, 1989). Baumgartner (1989, p.169) summarises the sentiments of other ethnic groups and asks, “With what right could the language of one ethnic group, even if that ethnic group lived in the national capital, be imposed on others?” Hau and Tinio (2003), however, point out that this opposition to Tagalog was not a manifestation of an ethnic conflict but rather reflects battles over resource allocations parceled out by regions. This has led for anti- Tagalog forces to ally themselves with the pro-English lobby (Lorente, 2013).

60’s and 70’s

The 60’s and the 70’s saw nationalist movements critical of the English language (Mahboob and Cruz, 2013). However, English remained a dominant language even at the peak of linguistic nationalism and height of student activism in the 70’s (Hau and Tinio, 2003). In 1974, a Bilingual Education Policy (BEP) was formally introduced, using English for Science and Mathematics and Filipino for all other subjects taught in school (Lorente, 2013). Gonzalez (1998) notes that this was a compromise to the demands of both nationalism and internationalism: English would ensure that Filipinos stay connected to the world while Filipino would help in the strengthening of the Filipino identity. This had little success, with English still dominant and Filipinos feared an “English deprived future.”

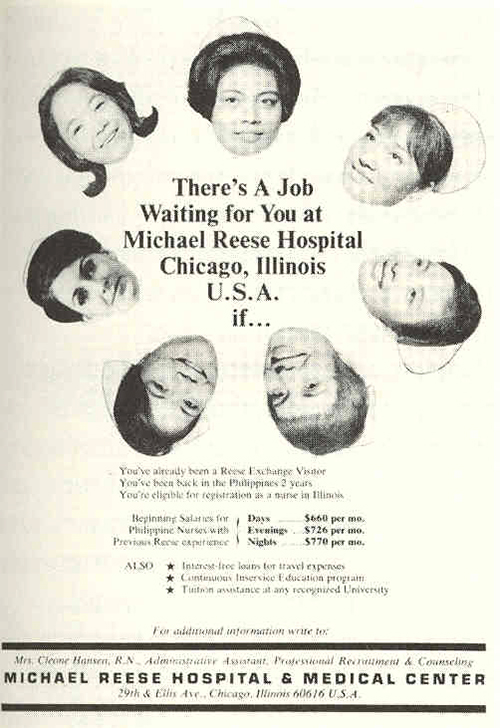

The year 1974 saw the start of the Philippines adhering to neoliberal policies, where the government started to promote cheap labour to other countries, advertising Filipinos’ ability to speak English. This was the year the first batch of Overseas Filipino Workers (OFW) was deployed to the Middle Least. An advertisement in The New York Times said: “We like multinationals … Local staff? Clerks with a college education start at $35 … accountants come for $67, executive secretaries for $148 … Our labor force speaks your language” (Lorente, 2013).

The 70’s, which was also the time of the dictatorship in the Philippines, saw changes in the education system, restructured to answer to export-oriented industrialisation (Lorente, 2013). With cheap export labour in mind, then President Ferdinand Marcos had a strong support for English and shifted English education to vocational and technical English training (Tollefson, 1991).

POST-DICTATORSHIP

After the dictatorship, the 1987 Constitution was written. Tagalog was changed to Pilipino and then Filipino for it to be less regionalistic, or less connected to the Tagalog region. According to this Constitution, Filipino was to be developed from all local languages of the Philippines.

According to this new BEP, Filipino and English shall be used as the medium of instruction while regional languages shall be used as auxiliary media of instruction and as initial language for literacy. Filipino was mandated to be the language of literacy and scholarly discourse while English, the “international language” of science and technology. However, nothing changed and implementation of the policy failed at most levels of education (Bernardo, 2004).

In 1991, the Komisyon ng Wikang Filipino (Commission on the Filipino Language) was established. They have led the celebration of Buwan ng Wika (National Language Month) every August. It is a regulating body whose job includes developing, preserving, and promoting the various local Philippine languages. The commission has published dictionaries, manuals, guides, and collection of literature in Filipino and other Philippine languages.

Both English and Filipino have dominated the education system in the Philippines. English is seen as the language of opportunities, and have been used by Filipinos to work abroad and find opportunities in the age of globalisation. Filipino , on the other hand, is seen as the language that can give identity to Filipinos, although not everyone agrees.

Will English and Filipino continue to dominate the country? With the current ideologies and policies put in place, it will. However, as other language speakers continue to fight for their identity and the right to be taught in their mother tongue, we might be able to see some changes, allowing for recognition of other languages in the country, and maybe even be given the same status as English and Filipino.

2 Replies to “A History of the Philippines’ official languages”

- Pingback: Is Filipino a growing language? - Inform Content Club

- Pingback: HISTORY OF THE ENGLISH LANGUAGE IN THE PHILIPPINES – MY TEACHING KIT

Comments are closed.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Solar Eclipse 2024

What the World Has Learned From Past Eclipses

C louds scudded over the small volcanic island of Principe, off the western coast of Africa, on the afternoon of May 29, 1919. Arthur Eddington, director of the Cambridge Observatory in the U.K., waited for the Sun to emerge. The remains of a morning thunderstorm could ruin everything.

The island was about to experience the rare and overwhelming sight of a total solar eclipse. For six minutes, the longest eclipse since 1416, the Moon would completely block the face of the Sun, pulling a curtain of darkness over a thin stripe of Earth. Eddington traveled into the eclipse path to try and prove one of the most consequential ideas of his age: Albert Einstein’s new theory of general relativity.

Eddington, a physicist, was one of the few people at the time who understood the theory, which Einstein proposed in 1915. But many other scientists were stymied by the bizarre idea that gravity is not a mutual attraction, but a warping of spacetime. Light itself would be subject to this warping, too. So an eclipse would be the best way to prove whether the theory was true, because with the Sun’s light blocked by the Moon, astronomers would be able to see whether the Sun’s gravity bent the light of distant stars behind it.

Two teams of astronomers boarded ships steaming from Liverpool, England, in March 1919 to watch the eclipse and take the measure of the stars. Eddington and his team went to Principe, and another team led by Frank Dyson of the Greenwich Observatory went to Sobral, Brazil.

Totality, the complete obscuration of the Sun, would be at 2:13 local time in Principe. Moments before the Moon slid in front of the Sun, the clouds finally began breaking up. For a moment, it was totally clear. Eddington and his group hastily captured images of a star cluster found near the Sun that day, called the Hyades, found in the constellation of Taurus. The astronomers were using the best astronomical technology of the time, photographic plates, which are large exposures taken on glass instead of film. Stars appeared on seven of the plates, and solar “prominences,” filaments of gas streaming from the Sun, appeared on others.

Eddington wanted to stay in Principe to measure the Hyades when there was no eclipse, but a ship workers’ strike made him leave early. Later, Eddington and Dyson both compared the glass plates taken during the eclipse to other glass plates captured of the Hyades in a different part of the sky, when there was no eclipse. On the images from Eddington’s and Dyson’s expeditions, the stars were not aligned. The 40-year-old Einstein was right.

“Lights All Askew In the Heavens,” the New York Times proclaimed when the scientific papers were published. The eclipse was the key to the discovery—as so many solar eclipses before and since have illuminated new findings about our universe.

To understand why Eddington and Dyson traveled such distances to watch the eclipse, we need to talk about gravity.

Since at least the days of Isaac Newton, who wrote in 1687, scientists thought gravity was a simple force of mutual attraction. Newton proposed that every object in the universe attracts every other object in the universe, and that the strength of this attraction is related to the size of the objects and the distances among them. This is mostly true, actually, but it’s a little more nuanced than that.

On much larger scales, like among black holes or galaxy clusters, Newtonian gravity falls short. It also can’t accurately account for the movement of large objects that are close together, such as how the orbit of Mercury is affected by its proximity the Sun.

Albert Einstein’s most consequential breakthrough solved these problems. General relativity holds that gravity is not really an invisible force of mutual attraction, but a distortion. Rather than some kind of mutual tug-of-war, large objects like the Sun and other stars respond relative to each other because the space they are in has been altered. Their mass is so great that they bend the fabric of space and time around themselves.

Read More: 10 Surprising Facts About the 2024 Solar Eclipse

This was a weird concept, and many scientists thought Einstein’s ideas and equations were ridiculous. But others thought it sounded reasonable. Einstein and others knew that if the theory was correct, and the fabric of reality is bending around large objects, then light itself would have to follow that bend. The light of a star in the great distance, for instance, would seem to curve around a large object in front of it, nearer to us—like our Sun. But normally, it’s impossible to study stars behind the Sun to measure this effect. Enter an eclipse.

Einstein’s theory gives an equation for how much the Sun’s gravity would displace the images of background stars. Newton’s theory predicts only half that amount of displacement.

Eddington and Dyson measured the Hyades cluster because it contains many stars; the more stars to distort, the better the comparison. Both teams of scientists encountered strange political and natural obstacles in making the discovery, which are chronicled beautifully in the book No Shadow of a Doubt: The 1919 Eclipse That Confirmed Einstein's Theory of Relativity , by the physicist Daniel Kennefick. But the confirmation of Einstein’s ideas was worth it. Eddington said as much in a letter to his mother: “The one good plate that I measured gave a result agreeing with Einstein,” he wrote , “and I think I have got a little confirmation from a second plate.”

The Eddington-Dyson experiments were hardly the first time scientists used eclipses to make profound new discoveries. The idea dates to the beginnings of human civilization.

Careful records of lunar and solar eclipses are one of the greatest legacies of ancient Babylon. Astronomers—or astrologers, really, but the goal was the same—were able to predict both lunar and solar eclipses with impressive accuracy. They worked out what we now call the Saros Cycle, a repeating period of 18 years, 11 days, and 8 hours in which eclipses appear to repeat. One Saros cycle is equal to 223 synodic months, which is the time it takes the Moon to return to the same phase as seen from Earth. They also figured out, though may not have understood it completely, the geometry that enables eclipses to happen.

The path we trace around the Sun is called the ecliptic. Our planet’s axis is tilted with respect to the ecliptic plane, which is why we have seasons, and why the other celestial bodies seem to cross the same general path in our sky.

As the Moon goes around Earth, it, too, crosses the plane of the ecliptic twice in a year. The ascending node is where the Moon moves into the northern ecliptic. The descending node is where the Moon enters the southern ecliptic. When the Moon crosses a node, a total solar eclipse can happen. Ancient astronomers were aware of these points in the sky, and by the apex of Babylonian civilization, they were very good at predicting when eclipses would occur.

Two and a half millennia later, in 2016, astronomers used these same ancient records to measure the change in the rate at which Earth’s rotation is slowing—which is to say, the amount by which are days are lengthening, over thousands of years.

By the middle of the 19 th century, scientific discoveries came at a frenetic pace, and eclipses powered many of them. In October 1868, two astronomers, Pierre Jules César Janssen and Joseph Norman Lockyer, separately measured the colors of sunlight during a total eclipse. Each found evidence of an unknown element, indicating a new discovery: Helium, named for the Greek god of the Sun. In another eclipse in 1869, astronomers found convincing evidence of another new element, which they nicknamed coronium—before learning a few decades later that it was not a new element, but highly ionized iron, indicating that the Sun’s atmosphere is exceptionally, bizarrely hot. This oddity led to the prediction, in the 1950s, of a continual outflow that we now call the solar wind.

And during solar eclipses between 1878 and 1908, astronomers searched in vain for a proposed extra planet within the orbit of Mercury. Provisionally named Vulcan, this planet was thought to exist because Newtonian gravity could not fully describe Mercury’s strange orbit. The matter of the innermost planet’s path was settled, finally, in 1915, when Einstein used general relativity equations to explain it.

Many eclipse expeditions were intended to learn something new, or to prove an idea right—or wrong. But many of these discoveries have major practical effects on us. Understanding the Sun, and why its atmosphere gets so hot, can help us predict solar outbursts that could disrupt the power grid and communications satellites. Understanding gravity, at all scales, allows us to know and to navigate the cosmos.

GPS satellites, for instance, provide accurate measurements down to inches on Earth. Relativity equations account for the effects of the Earth’s gravity and the distances between the satellites and their receivers on the ground. Special relativity holds that the clocks on satellites, which experience weaker gravity, seem to run slower than clocks under the stronger force of gravity on Earth. From the point of view of the satellite, Earth clocks seem to run faster. We can use different satellites in different positions, and different ground stations, to accurately triangulate our positions on Earth down to inches. Without those calculations, GPS satellites would be far less precise.

This year, scientists fanned out across North America and in the skies above it will continue the legacy of eclipse science. Scientists from NASA and several universities and other research institutions will study Earth’s atmosphere; the Sun’s atmosphere; the Sun’s magnetic fields; and the Sun’s atmospheric outbursts, called coronal mass ejections.

When you look up at the Sun and Moon on the eclipse , the Moon’s day — or just observe its shadow darkening the ground beneath the clouds, which seems more likely — think about all the discoveries still yet waiting to happen, just behind the shadow of the Moon.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Dua Lipa Manifested All of This

- Exclusive: Google Workers Revolt Over $1.2 Billion Contract With Israel

- Stop Looking for Your Forever Home

- The Sympathizer Counters 50 Years of Hollywood Vietnam War Narratives

- The Bliss of Seeing the Eclipse From Cleveland

- Hormonal Birth Control Doesn’t Deserve Its Bad Reputation

- The Best TV Shows to Watch on Peacock

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Advertisement

What Solar Eclipse-Gazing Has Looked Like for the Past 2 Centuries

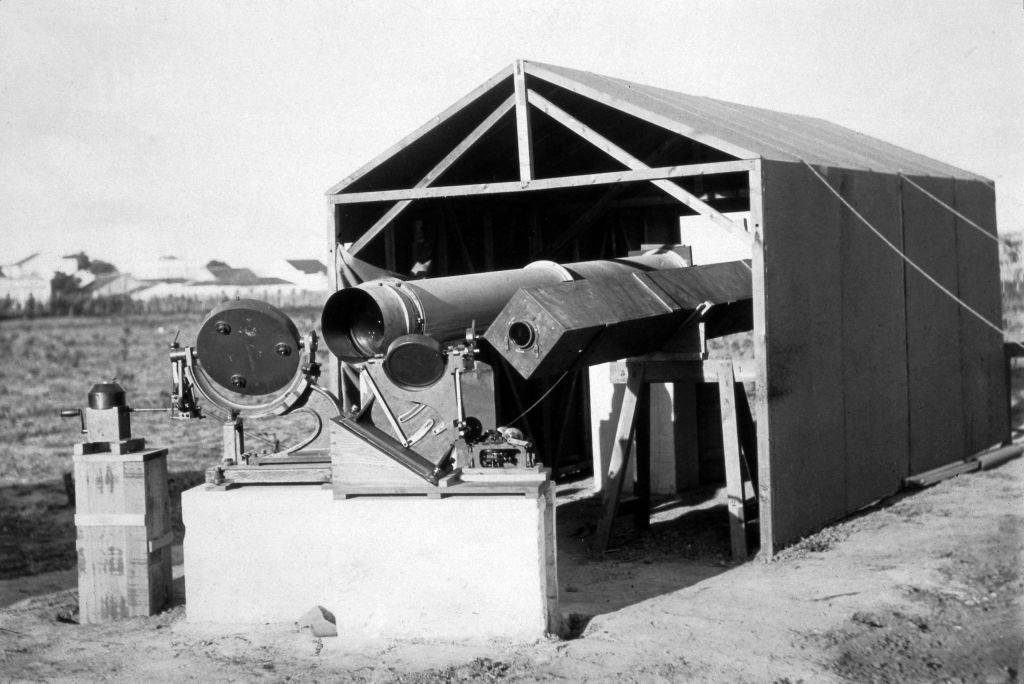

Millions of people on Monday will continue the tradition of experiencing and capturing solar eclipses, a pursuit that has spawned a lot of unusual gear.

- Share full article

By Sarah Eckinger

- April 8, 2024

For centuries, people have been clamoring to glimpse solar eclipses. From astronomers with custom-built photographic equipment to groups huddled together with special glasses, this spectacle has captivated the human imagination.

Creating a Permanent Record

In 1860, Warren de la Rue captured what many sources describe as the first photograph of a total solar eclipse . He took it in Rivabellosa, Spain, with an instrument known as the Kew Photoheliograph . This combination of a telescope and camera was specifically built to photograph the sun.

Forty years later, Nevil Maskelyne, a magician and an astronomy enthusiast, filmed a total solar eclipse in North Carolina. The footage was lost, however, and only released in 2019 after it was rediscovered in the Royal Astronomical Society’s archives.

Telescopic Vision

For scientists and astronomers, eclipses provide an opportunity not only to view the moon’s umbra and gaze at the sun’s corona, but also to make observations that further their studies. Many observatories, or friendly neighbors with a telescope, also make their instruments available to the public during eclipses.

Fredrik Hjalmar Johansen, Fridtjof Nansen and Sigurd Scott Hansen observing a solar eclipse while on a polar expedition in 1894 .

Women from Wellesley College in Massachusetts and their professor tested out equipment ahead of their eclipse trip (to “catch old Sol in the act,” as the original New York Times article phrased it) to New London, Conn., in 1922.

A group from Swarthmore College in Pennsylvania traveled to Yerbaniz, Mexico, in 1923, with telescopes and a 65-foot camera to observe the sun’s corona .

Dr. J.J. Nassau, director of the Warner and Swasey Observatory at Case School of Applied Science in Cleveland, prepared to head to Douglas Hill, Maine, to study an eclipse in 1932. An entire freight car was required to transport the institution’s equipment.

Visitors viewed a solar eclipse at an observatory in Berlin in the mid-1930s.

A family set up two telescopes in Bar Harbor, Maine, in 1963. The two children placed stones on the base to help steady them.

An astronomer examined equipment for an eclipse in a desert in Mauritania in June 1973. We credit the hot climate for his choice in outfit.

Indirect Light

If you see people on Monday sprinting to your local park clutching pieces of paper, or with a cardboard box of their head, they are probably planning to reflect or project images of the solar eclipse onto a surface.

Cynthia Goulakos demonstrated a safe way to view a solar eclipse , with two pieces of cardboard to create a reflection of the shadowed sun, in Lowell, Mass., in 1970.

Another popular option is to create a pinhole camera. This woman did so in Central Park in 1963 by using a paper cup with a small hole in the bottom and a twin-lens reflex camera.

Amateur astronomers viewed a partial eclipse, projected from a telescope onto a screen, from atop the Empire State Building in 1967 .

Back in Central Park, in 1970, Irving Schwartz and his wife reflected an eclipse onto a piece of paper by holding binoculars on the edge of a garbage basket.

Children in Denver in 1979 used cardboard viewing boxes and pieces of paper with small pinholes to view projections of a partial eclipse.

A crowd gathered around a basin of water dyed with dark ink, waiting for the reflection of a solar eclipse to appear, in Hanoi, Vietnam, in 1995.

Staring at the Sun (or, How Not to Burn Your Retinas)

Eclipse-gazers have used different methods to protect their eyes throughout the years, some safer than others .

In 1927, women gathered at a window in a building in London to watch a total eclipse through smoked glass. This was popularized in France in the 1700s , but fell out of favor when physicians began writing papers on children whose vision was damaged.

Another trend was to use a strip of exposed photographic film, as seen below in Sydney, Australia, in 1948 and in Turkana, Kenya, in 1963. This method, which was even suggested by The Times in 1979 , has since been declared unsafe.

Solar eclipse glasses are a popular and safe way to view the event ( if you use models compliant with international safety standards ). Over the years there have been various styles, including these large hand-held options found in West Palm Beach, Fla., in 1979.

Parents and children watched a partial eclipse through their eclipse glasses in Tokyo in 1981.

Slimmer, more colorful options were used in Nabusimake, Colombia, in 1998.

In France in 1999.

And in Iran and England in 1999.

And the best way to see the eclipse? With family and friends at a watch party, like this one in Isalo National Park in Madagascar in 2001.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

history of the Philippines, a survey of notable events and people in the history of the Philippines.The Philippines takes its name from Philip II, who was king of Spain during the Spanish colonization of the islands in the 16th century. Because it was under Spanish rule for 333 years and under U.S. tutelage for a further 48 years, the Philippines has many cultural affinities with the West.

The history of the Philippines dates from the earliest hominin activity in the archipelago at least by 709,000 years ago. Homo luzonensis, a species of archaic humans, was present on the island of Luzon at least by 134,000 years ago. The earliest known anatomically modern human was from Tabon Caves in Palawan dating about 47,000 years.

500 Words Essay on Philippines History Early History. The Philippines is a Southeast Asian country with a rich and complex history. The early history of the Philippines dates back to around 50,000 years ago when the first humans arrived from Borneo and Sumatra via boats. These early people were known as Negritos, who were followed by the ...

Philippines Geography and Population. Area: 120,000 square miles; slightly larger than Arizona Population: 107 million Government. Freedom House rating from "Freedom in the World 2015" (ranking of political rights and civil liberties in 195 countries): Partly Free. Type: Republic Chief of State and Head of Government: President Benigno Aquino (since June 30, 2010)

The Philippines is an archipelago made up of over 7,000 islands located in Southeast Asia. There are more than 175 ethnolinguistic groups, and over 100 dialects and languages spoken. One of the difficulties of writing a history of the Philippines is that prior to the arrival of the Spanish in the sixteenth century, the people that inhabited the ...

The Philippines takes its name from Philip II, who was king of Spain during the Spanish colonization of the islands in the 16th century. Because it was under Spanish rule for 333 years and under U.S. tutelage for a further 48 years, the Philippines has many cultural affinities with the West. It is, for example, the second most-populous Asian country (following India) with English as an ...

My AAS Key Issues in Asian Studies book—The Philippines: From Earliest Times to the Present—is intended to introduce readers to a nation originally named after a European prince. The people of the archipelago that now constitutes the Philippines had a long history before any European contact occurred. Since the latter part of the nineteenth century, […]

The islands were liberated by U.S. forces in 1944-45, and the Republic of the Philippines was proclaimed in 1946, with a government patterned on that of the U.S. In 1965 Ferdinand Marcos was elected president. He declared martial law in 1972, which lasted until 1981. After 20 years of dictatorial rule, Marcos was driven from power in 1986.

500 Words Essay on History Of The Philippines Early Inhabitants and Trading. Long before the Philippines became the country we know today, it was home to small groups of people who lived off the land. These early Filipinos were hunters, gatherers, and later on, farmers. They lived in small communities and were skilled in using what nature provided.

A Critique Paper by Paula I. Clavecillas [BSCOE 2-1] Readings in Philippine History The Philippines: A Past Revisited is one of the many written works of late Filipino historian Renato Constantino. From a young age, Constantino has been a prolific writer and journalist. ... 1 Critical Essay: "The Philippines: A Past Revisited" by Renato ...

The Philippines: A Part Revisited is one of many works of Renato Constantino. He was a Filipino historian. with a number of books and articles. Renato Consta ntino had a significant impact on the ...

The first people in the Philippines were hunter-gatherers. However, between 3,000 BC and 2,000 BC, people learned to farm. They grew rice and domesticated animals. From the 10th AD century Filipinos traded with China and by the 12th Century AD Arab merchants reached the Philippines and they introduced Islam.

This essay is as an advertisement for a subject that has been either neglected or treated in an episodic, fragmented manner by historians of imperialism and empire. ... The Philippines in Imperial History Reynaldo Clemeña Ileto, Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840-1910. Manila: Ateneo de Manila University Press ...

essay about why we need to study philippine history. Studying history allows us to gain precious perspectives on the cases of our ultramodern society. Numerous cases, features, and characteristics of ultramodern Philippine society can be traced ago to literal questions on our social history, as well as our-colonial cultivation.

The recorded history of the Philippines between 900 and 1565 begins with the creation of the Laguna Copperplate Inscription in 900 and ends with the beginning of Spanish colonization in 1565. The inscription records its date of creation in 822 Saka (900 CE). The discovery of this document marks the end of the prehistory of the Philippines at 900 AD. During this historical time period, the ...

250 Words Essay on Philippines Culture Introduction to Philippines Culture. The Philippines is a country in Southeast Asia known for its rich and diverse culture. This culture is a mix of native and foreign influences from its history, including Spanish, American, and Asian cultures.

This is just a short essay about the importance of reading and learning history specifically, the Philippine history. essay when you hear the word come in to. Skip to document. ... This paper will discuss the importance of learning history, especially the history of the Philippines. The importance include, knowing the identification or the ...

The Road to 1898: On American Empire and the Philippine Revolution. '1898' marks the birth of both the American empire and the Filipino nation when the U.S. Navy joined forces with Filipino revolutionists in ending Spain's rule. The alliance ended when the Americans refused to recognise the Filipino... more. Download.

Given the rich history of the country and controversies regarding its language planning and policy throughout the century, this essay aims to explore the history of language policy and planning in the Philippines and the impacts it has had on its people, especially the non-Tagalog/Filipino speaking population.

Essay, Pages 4 (822 words) Views. 2. The Philippines archipelago is comprises of about 7,641 islands which only about 2,000 are inhabited. The three major island of the Philippines namely Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao has its different and own history of how people defended and fight for their land, people's way of living before colonization ...

The history of the Philippines is believed to have begun with the arrival of the first humans using rafts or primitive boats, at least 67,000 years ago as the 2007 discovery of Callao Man showed. [1] The first recorded visit from the West is the arrival of Ferdinand Magellan, who sighted the island of Samar Island on March 16, 1521 and landed ...

History of the Philippines. The history of the Philippines is believed to have begun with the arrival of the first humans using rafts or primitive boats, at least 67,000 years ago as the 2007 discovery of Callao Man showed. Spanish colonization and settlement began with the arrival of Miguel Lopez de Legazpi's expedition on February 13, 1565 ...

the history of the Philippines essay - Free download as Open Office file (.odt), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. its made by chatgpt

"Lights All Askew In the Heavens," the New York Times proclaimed when the scientific papers were published. The eclipse was the key to the discovery—as so many solar eclipses before and ...

This was popularized in France in the 1700s, but fell out of favor when physicians began writing papers on children whose vision was damaged. Image.

Wednesday's earthquake shook more parts of Taiwan with greater intensity than any other quake since 1999, when a 7.7 magnitude tremor hit the middle of the island, killing 2,400 people and ...